Abstract

TIS11d is a member of the CCCH-type family of tandem zinc finger (TZF) proteins; the TZF domain of TIS11d (residues 151–220) is sufficient to bind and destabilize its target mRNAs with high specificity. In this study, the TZF domain of TIS11d is simulated in an aqueous environment in both the free and RNA-bound states. Multiple nanosecond timescale molecular dynamics trajectories of TIS11d wild-type and E157R/E195K mutant with different RNA sequences were performed to investigate the molecular basis for RNA binding specificities of this TZF domain. A variety of measures of the protein structure, fluctuations, and dynamics were used to analyze the trajectories. The results of this study support the following conclusions: (1) the structure of the two fingers is maintained in the free state but a global reorientation occurs to yield a more compact structure; (2) mutation of the glutamate residues at positions 157 and 195 to arginine and lysine, respectively, affects the RNA recognition by this TIS11d mutant in agreement with the findings of Pagano et al. (J Biol Chem 2007; 282:8883–8894); and (3) we predict that the E157R/E195K mutant will present a more relaxed RNA binding specificity relative to wild-type TIS11d based on the more favorable nonsequence-specific Coulomb interaction of the two positively charged residues at positions 157 and 195 with the RNA backbone, which compensates for a partial loss of the stacking interaction of aromatic side chains with the RNA bases.

Keywords: protein dynamics, post-transcriptional regulation, computer simulation, RNA-binding protein

Background

Regulation of gene replication, transcription, and translation is critical in the cell and is accurately controlled in all stages of an organism's life through interactions between proteins and nucleic acids. Gene expression can be controlled at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. Post-transcriptional control is achieved by regulating the stability or translational efficiency of mRNA.

Tristetraprolin (TTP) is an RNA-binding protein that binds AU-rich elements (ARE) located in the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the mRNAs that encode for important proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α, granulocyte/macrophage colony stimulating factor, and interleukin-2.1–3 TTP binds with high specificity and promotes the deadenylation and consequent degradation of these transcripts.2,4–7 TTP is the prototype of the CCCH-type family of tandem zinc finger (TZF) proteins. There are two additional mammalian members in this protein family which have TTP-like activity in normal physiology: TIS11b (also known as ERF-1) and TIS11d (also known as ERF-2).8 TTP, TIS11b, and TIS11d have a high degree of sequence identity: TIS11b/d are 71% identical to TTP, and 91% identical to each other, as shown in Figure 1(B). The integrity of both fingers is necessary for binding RNA, as any mutation of the CCCH residues abolishes binding.10 In all vertebrate proteins of this class, the zinc finger motifs are characterized by the sequence CX8CX5CX3H and the zinc finger domains are separated by an 18 residue long linker [Fig. 1(A)].

Figure 1.

A: Schematic representation of the TZF domain of TIS11d; ZF1, ZF2, and the linking region are indicated with boxes and residue numbers. B: Sequence alignment of CCCH-type tandem zinc finger proteins. Alignment of human (h) TTP with hTIS11d/b and C. elegans (c) MEX-5, MEX-6, MEX-1, POS-1, and PIE-1. Conserved motifs (R(K)YTEL) are represented in blue. The three cysteines and the histidine involved in zinc binding are highlighted in red. Residues directly involved in RNA binding in the NMR structure of TIS11d are indicated with an asterisk: a black asterisk is used for residues which form a hydrogen bond with a base of the RNA sequence and a green asterisk identifies aromatic residues involved in base-stacking interactions with the RNA. C: NMR solution structure of the TIS11d-ARE complex (PDB accession code 1RGO).9 Pink: TIS11d with zinc-coordinating residues shown, gray spheres: zinc ions, purple: RNA.

The solution structure of the TZF domain of TIS11d (residues 151–220) bound to the RNA oligonucleotide 5′-UUAUUUAUU-3′ has been solved using NMR spectroscopy.9 The structure of the TZF domain of TIS11d in complex with its cognate RNA is the only known structure for this family of CCCH-type zinc finger proteins. This structure is a novel fold characterized by few secondary structural elements; the two zinc finger domains have an α-helix and a turn of a 310-helix in nearly the same conformation [Fig. 1(C)]. The CCCH motifs are located from residues 159–178 and 197–216 (finger 1 (ZF1) and finger 2 (ZF2), respectively). The zinc ions are coordinated to the sulfur atoms of Cys159 (Cys197), Cys168 (Cys206), and Cys174 (Cys212) and the Nɛ of His 178 (His216) in ZF1 (ZF2). The single secondary structural element in the linking residues is a 310-helix located near ZF1. Hydrogen bonds and stacking interactions between the side chains of highly conserved aromatic residues, highlighted in Figure 1(B), and all of the RNA bases have an essential role in stabilizing the protein–RNA interaction. Surprisingly, the sequence specificity is achieved primarily through hydrogen bonds between the protein backbone and the RNA bases.

CCCH-type TZF domains are found in many proteins that specifically regulate the essential processes of post-transcriptional gene expression and splicing. In particular, the TZF domain of the Caenorhabditis elegans protein MEX-5 plays a crucial role in the early stages of embryogenesis. Unlike TIS11d, MEX-5 binds RNA with high affinity and low specificity; the minimal binding site is between 9 and 13 nucleotides in length and contains six or more uridines.11 Each finger of TIS11d is preceded by the conserved six-residue motif R(K)YKTEL8,12; these and other residues directly involved in RNA binding are not as well conserved in C. elegans TZF proteins as they are in mammalian TZF proteins [Fig. 1(B)]. These differences likely contribute to the different binding specificities observed in TIS11d and MEX-5. Recent studies of MEX-5 have identified the fifth residue of the conserved motif R(K)YTR(K)L preceding each finger as a discriminator for RNA binding specificity.11 Substitution of the fifth residue with a glutamate in each motif (as in TIS11d) increases the binding affinity of the MEX-5 double mutant R274E/K318E for UAUU repeat RNA over polyuridine, giving TIS11d-like specificity to the otherwise promiscuous MEX-5. To rationalize this result, the unknown structure of MEX-5 was modeled using the structure of TIS11d. R274 and K318 were seen to rotate away from the adenine and form backbone contacts with neighboring nucleotides. The hypothesis presented is that the loss of base-specific hydrogen bonds and the additional backbone contacts formed contribute to relaxed specificity in MEX-5. However, no clear explanation can be given solely by comparing structural differences, as only E157 forms a hydrogen bond with adenine in the TIS11d-RNA NMR structure. In this computational study we investigate the hypothesis that distinct RNA-binding specificities, and consequent regulatory mechanisms of this family of CCCH-type TZF proteins, derive from the structures and dynamics of the protein–RNA complexes.

TIS11d is a good model to investigate the determinants of RNA binding specificity not only because it binds RNA with high affinity and specificity but also because of the existence of homologous proteins with high RNA binding affinity but low specificity. In this study, we develop a model of the TZF domain of TIS11d in solution, based on the known NMR solution structure of the protein–RNA complex.9 We used this model to explore the protein structure and dynamics in the free and RNA-bound states to characterize fundamental aspects of molecular recognition and binding specificity between this protein and RNA. Multiple molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were collected starting from different independent initial conformations, from the NMR-derived ensemble of structures, of the TZF domain of wild-type TIS11d free and bound to two different RNA sequences. To verify if the fifth position of the conserved six-residue motif (R(K)YKTEL) of TIS11d also acts as a discriminator for RNA binding specificity, as found in MEX-5, we collected multiple MD trajectories of the double mutant E157R/E195K of TIS11d in complex with two different RNA sequences. These trajectories were analyzed to determine the structure, intra- and intermolecular fluctuations and overall protein and RNA dynamics. The results of this study support the following main conclusions. (1) On removal of the RNA, the flexible linker of TIS11d rapidly undergoes a structural transition that leads to a more collapsed state where hydrophobic residues, including RNA-binding residues, are sequestered from the solvent. This result is not only important for understanding TIS11d RNA-binding affinity and specificity, but to understand TIS11d interactions with other binding partners that are critical for its biological function. (2) Although the structures of the wild-type and E157R/E195K mutant proteins are highly similar, the mutant protein is less able to maintain the stacking interactions between the side chains of the highly conserved aromatic residues, highlighted in Figure 1(B), and all of the RNA bases. In addition, because the protein–RNA interaction energy is dominated by the nonsequence-specific Coulomb attraction, we predict that the E157R/E195K mutant protein will lose its ability to discriminate between the two different RNA sequences. This result is consistent with recent experimental studies of MEX-5 RNA binding specificity.11

Results

TIS11d solution structure and fluctuations

MD simulations of the TZF domain of TIS11d (residues 151–220) free and bound to RNA have been performed to identify the key interactions that stabilize TIS11d in the bound and free states, and their role in RNA binding activity.

The structure of TIS11d is more open and less flexible when bound to RNA

The equilibrated free structure of TIS11d is different from the RNA-bound structure (TIS11d-ARE). After removal of RNA, the residues of the linker undergo a major structural transition that changes the distance and the global orientation of the two fingers very early in the equilibration. The structural transition observed in the linker region on compaction of TIS11d in the absence of RNA occurs through transitions in backbone dihedral angles of the residues located in the linker region [Fig. 1(A)]. The result of this transition is a global compaction of the protein rather than a loss of local structure. To quantify the degree of this compaction, we measured the radius of gyration and the linker end-to-end distance, as reported in Table I. In each case, we observe a consistent reduction in the mean values in the trajectories of TIS11d relative to trajectories of TIS11d-ARE. The structure of the fingers is predominantly conserved, as shown in Figure 2(B,C).

Table I.

Mean and Error of the Radius of Gyration, Linker End-to-End Distance, Distance Between Zn2+ Ions and Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA), Calculated from the Original 20 NMR Structures and the MD Trajectories of TIS11d-ARE and TIS11d

| Radius of gyration (Å) | Linker end-to-end distance (Å) | Zn2+–Zn2+ distance (Å) | SASA (Å2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR | 15.2 ± 0.2 | 32.1 ± 0.6 | 25.7 ± 0.5 | 6511 ± 146 |

| TIS11d- ARE | 15.1 ± 0.1 | 30.8 ± 0.1 | 24.8 ± 0.1 | 6753 ± 138 |

| TIS11d | 14.4 ± 0.3 | 25.6 ± 1.1 | 24.0 ± 1.7 | 6261 ± 65 |

Figure 2.

Compaction of TIS11d structure. A: Snapshots colored by time. Left: TIS11d-ARE between 10 and 14 ns aligned on the protein backbone—red (10 ns), orange (10.4 ns), yellow (10.8 ns), green (11.6 ns), cyan (12 ns), blue (12.8 ns), indigo (13.6 ns), purple (14 ns), right: TIS11d between 24 and 28 ns aligned on the protein backbone—red (24 ns), orange (24.4 ns), yellow (24.8 ns), green (25.6 ns), cyan (26 ns), blue (26.8 ns), indigo (27.6 ns), purple (28 ns). B, C: Red: NMR structure of the TIS11d-ARE complex depicted without showing the RNA (PDB accession code 1RGO),9 blue: structures from MD trajectories aligned on NMR structure (see below), gray spheres: zinc ions. B: Snapshot of the TIS11d-ARE complex at 14 ns. C: Snapshot of TIS11d at 28 ns. From left to right: full TZF domain, ZF1, and ZF2. Full TZF domain is aligned on all backbone atoms (B) or the backbone atoms of ZF1 (C), ZF1 and ZF2 are aligned on their respective backbone atoms. D: Normalized histograms of the total protein solvent accessible surface area (SASA). SASA of the TIS11d-ARE complex is represented in black, when the RNA treated as solvent, and red when the RNA shielding is included. SASA calculated for two MD trajectories of TIS11d are represented in blue and green.

The compacted structures are very dynamic. The Lipari–Szabo order parameters13 were calculated for the amide N—H bond vectors to quantify the relative flexibility of the free and RNA-bound form of TIS11d [Fig. 3(A)]. As indicated by the large error bars, the independent trajectories have not converged for residues 186–189 of the linker.

Figure 3.

Difference of the mean order parameter by residue. Error bars are calculated from the standard deviation among trajectories. The boxes in (A) highlight the two zinc finger domains. A:  −

−  ; B:

; B:  −

−  .

.

The difference of the order parameters observed between the free and RNA-bound state of TIS11d shows increased flexibility in the backbone of free TIS11d, with few exceptions. The decreased backbone flexibility observed in the free state relative to the bound state for Gly179 and for the C-terminus is the result of the formation of new hydrogen bonds that stabilize the structure of TIS11d in the free state. In particular, after undergoing dihedral angle fluctuations in the initial structural compaction, Gly179 becomes more rigid due to the formation of a new hydrogen bond between His178 and Glu182. The formation of a hydrogen bond between the backbone carbonyl oxygen atom of Glu220 and Arg188 (shown in Fig. 4) results in the decreased flexibility observed for the C-terminus of TIS11d in the free state.

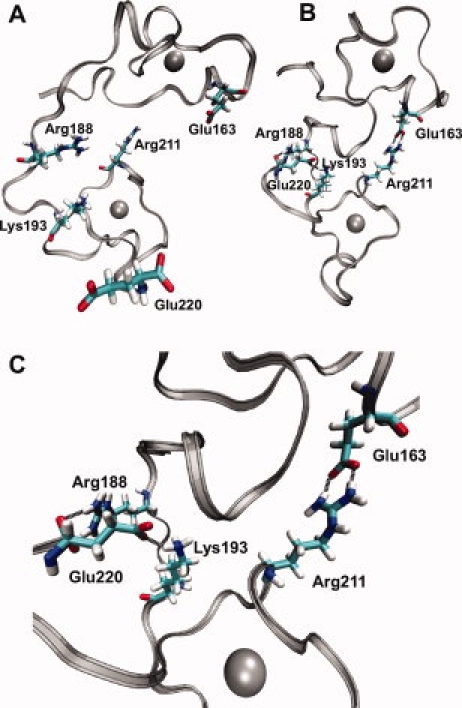

Figure 4.

Hydrogen bonds (black dashed lines) between different finger domains of TIS11d. Silver ribbon: protein backbone, gray spheres: zinc ions, residues as labeled. A: The structure of TIS11d-ARE (RNA not shown) at 14 ns. B: Structure of TIS11d at 28 ns. C: Structure of TIS11d at 28 ns enlarged to show detail.

Compaction of the structure can be seen through solvent accessible surface area (SASA). The SASA14,15 of the TIS11d-ARE trajectories can be calculated either with or without the contribution of RNA to the solvent shielding. The difference in the SASA can be seen in Figure 2(D), where the SASA of the protein without the RNA contribution is shown in black and the SASA including the contribution from the RNA is shown in red. The trajectories of TIS11d (blue, green) show a SASA that is closer to that of the TIS11d-ARE trajectories when the shielding from RNA is included. One of the two collected trajectories of TIS11d in the free state shows a bimodal distribution of the SASA, shown in green in Figure 2(D). This feature is the result of the initial compaction of the structure, observed for the first 4 ns of the production run, followed by a phase in which the distance between the two fingers gradually increases (24–26 ns) and then decreases again (26–28 ns), as illustrated in Figure 2(A).

The hydrophobic residues and the RNA-binding residues mirror the trend in the total SASA. These observations indicate that in the absence of RNA, the protein compacts itself to approach the same amount of SASA as it has in the protein–RNA complex. An additional 10 independent trajectories of TIS11d that used a different energy function to model Zn2+ (see “Methods” section) were run to see if the same structural transition occurred in the absence of RNA. These trajectories also show a clear trend in the decrease of solvent accessible surface area and present the same protein contact map patterns.

The presence of RNA assists in maintaining the hydrogen bonds formed within the structure of TIS11d

All of the intramolecular hydrogen bonds present in the NMR structure of the TIS11d-ARE complex are maintained in the two MD trajectories of TIS11d-ARE. The orientation of the two fingers is important in RNA binding. In particular, Thr156, Glu157, and Gln175 form very strong hydrogen bonds with U6 in ZF1. Similarly, Thr194, Glu195, and His213 form strong bonds with U2 in ZF2. The existence of these three bonds with the same nucleotide, but involving residues that are separated by 17 residues in the sequence of the protein, shows the role of RNA in preserving the tertiary alignment of the zinc fingers. The release of the protein from the RNA complex decreases the hydrogen bond probability in the existing hydrogen bonds of Gly171 to Cys168, Gly209 to Cys206, and Phe172 to Cys159 and allows for the formation of new interactions. These hydrogen bonds in the fingers involve zinc-coordinating cysteine sulfur atoms. Hydrogen bonds involving sulfur are known to be often less stable than their analogues involving oxygen.16 The presence of RNA helps stabilize these interactions, which are otherwise less stable.

In the absence of RNA, new interactions can be seen through new contacts within the protein. Hydrogen bonds are formed between distant residues which stabilize the compact structure (Fig. 4). We observe different contacts in the different trajectories. In the trajectory not shown in Figure 4, Arg211 forms a hydrogen bond with Glu157 instead of Glu163 and the hydrogen bonds formed between Glu220 and Arg198 or Lys193 are less likely to be present, but an additional hydrogen bond is formed between Arg160 and Glu220. The sum of the probabilities of these hydrogen bonds is similar in the two trajectories (Ptot = 2.75 and 2.98), indicating that in total, the amount of stabilization from new hydrogen bonds is consistent in the two trajectories.

Sequence-dependent effect on binding specificity

In the TTP family of proteins, the six-residue motif R(K)YTEL preceding both fingers is highly conserved. In the C. elegans protein MEX-5, this motif is maintained except for the glutamate, in MEX-5 it is R(K)YTR(K)L, as shown in Figure 1(B). MEX-5 is a promiscuous protein that recognizes uridine-rich RNA sequences and has been shown to gain TIS11d-like specificity after mutation of the fifth residue in this six-residue motif.11 After mutation of these arginine and lysine residues in MEX-5 to glutamate (as in TIS11d), it binds with higher affinity to an ARE than to a sequence of polyuridine. To explore the role of the primary sequence on binding specificity of TIS11d, we mutated the glutamates of the R(K)YTEL motif in TIS11d to Arg/Lys in ZF1/ZF2, respectively. The adenine binding pocket, defined as the last three residues of the six-residue motif, is shown in Figure 5. To determine whether these mutations would make TIS11d incapable of binding specifically to ARE over polyuridine sequences, as in MEX-5, three independent MD trajectories for each of the following systems were run: wild-type TIS11d bound to the RNA polyuridine nonamer U9 (TIS11d-U9), the E157R/E195K double mutant of TIS11d bound to the cognate RNA nonamer UUAUUUAUU (E157R/E195K-ARE) and the E157R/E195K double mutant of TIS11d bound to U9 (E157R/E195K-U9).

Figure 5.

Adenine recognition pocket of ZF2. Red: protein side chains for residues 195–198, blue: protein backbone, gray: RNA phosphate group and sugar of nucleotide 3, green: RNA base ring of nucleotide 3. Hydrogen bonds are depicted with a black dashed line. (A) TIS11d-ARE, (B) TIS11d-U9, (C) E157R/E195K-ARE, and (D) E157R/E195K-U9.

Mutations have little effect on bound protein structure

The conformation of the protein is minimally affected by the mutations. Protein–protein contact maps show only minor differences. Mean backbone dihedral angles are similar, except in part of the disordered linker region and one section of ZF2. Figure 6 shows representative structures from the TIS11d-U9, E157R/E195K-ARE, and E157R/E195K-U9 simulations. As in the free case, the structure of the fingers is very similar. Little rotation of the fingers with respect to each other occurs in these structures since they remain bound to RNA throughout the entire trajectory.

Figure 6.

Structures of E157R/E195K mutants and different RNA sequences (RNA not shown). The zinc ion of each finger is represented in gray. Proteins are shown with ZF2 on the left and ZF1 on the right. From left to right: full TZF domain, ZF1, and ZF2, respectively aligned on NMR of the TIS11d-ARE complex9 structure (in red) using the backbone atoms of ZF1, ZF1, and ZF2. Blue (A) TIS11d-U9, (B) E157R/E195K-U9, and (C) E157R/E195K-ARE.

Hydrogen bond network with RNA is perturbed in E157R/E195K mutant

Several hydrogen bonds between the protein backbone atoms and the RNA bases are important in the mechanism of ARE recognition. Residues of the conserved R(K)YKTEL motifs are directly involved in hydrogen bonds with the RNA bases. Mutation of the glutamate residues at position five of the motif affects the stability of other hydrogen bonds, particularly in ZF2 (Fig. 7). Interestingly, the hydrogen bond between A3 and Leu198 is conserved in E157R/E195K-ARE, but the hydrogen bond between A3 and Arg196 is weaker in E157R/E195K-ARE (hydrogen bond probability of P = 0.70) than in TIS11d-ARE (P = 1.0). TIS11d-U9 and E157R/E195K-U9 form no bonds with U3 to replace those lost with A3. Leu196 and Arg198 instead form hydrogen bonds with U1 in TIS11d-U9 and E157R/E195K-U9 (Fig. 7). Figure 5(B,D) illustrates the lack of interactions of ZF2 with the nucleotide at position 3 in TIS11d-U9 and E157R/E195K-U9.

Figure 7.

Protein–RNA hydrogen bond probabilities. The mean and standard deviation of the sum of all protein–RNA hydrogen bond probabilities is represented for each RNA nucleotide. Red: TIS11d-ARE, blue: TIS11d-U9, green: E157R/E195K-U9, and purple: E157R/E195K-ARE.

The hydrogen bond between U5 and Pro207 is stronger in the TIS11d-ARE and TIS11d-U9 trajectories. This bond is strongest in TIS11d-ARE (P = 0.87), less in TIS11d-U9 (P = 0.59), and weakest in E157R/E195K-ARE and E157R/E195K-U9 (P = 0.20 and 0.27, respectively). This pattern is also seen in two additional bonds of U5 with the side chains of Arg211 and Tyr208. The analogous interaction in ZF1 between U9 and Lys169 is nonexistent in all trajectories except E157R/E195K-ARE (P = 0.48). A compensatory bond is formed between U9 and Tyr170 in all trajectories but TIS11d-ARE, with P = 0.97, 0.66, and 0.98 for TIS11d-U9, E157R/E195K-U9 and E157R/E195K-ARE, respectively. E157R/E195K-U9 also has weaker bonds between His213 and U4 (P = 0.85), Cys174 and U8 (P = 0.67), and Gln175 and U8 (P = 0.68).

Another significant difference observed in the adenosine recognition region of ZF1 when the protein is bound to U9 is that the amide proton of residue Leu160 forms an interaction with U7 O4 (formerly A7). The uridine nucleotide at position 3 is unable to reach the backbone atoms of ZF2 to form stabilizing hydrogen bonds because of the steric hindrance of the intercalating base stacks. Adenosine, in contrast, is a larger nucleotide and does form hydrogen bonds. ZF1 is able to form replacement hydrogen bonds with U7, but the Leu160 bond is not as strong as the bond with A7 (P = 0.69 and P = 0.64 for TIS11d-U9 and E157R/E195K-U9, respectively, vs. P = 1.00 for both TIS11d-ARE and E157R/E195K-ARE).

E157R and E195K mutations increase dynamics of the intercalated base stacks

The interface between the protein and the RNA is dominated by the stacking interactions between the aromatic side chains of Tyr170, Phe176, Tyr208, and Phe214 and the RNA bases, as shown in Figure 8(A). Increased motion of the intercalating aromatic side chains in E157R/E195K-ARE and E157R/E195K-U9 results in the partial loss of the intercalation with the RNA bases, particularly in ZF2, as shown by a snapshot from the trajectories of E157R/E195K-U9 in Figure 8(B). E157R/E195K-U9 has reduced intercalation in ZF1 as well. In addition, the dynamics of the aromatic side chains directly affect hydrogen-bonding interactions of TIS11d residues with the RNA, causing the loss of hydrogen bonds in the adjacent residues Pro207, His213, and Gln175, as discussed above.

Figure 8.

RNA intercalation. Red: protein side chains of residues 170,176, 208, and 214, blue: protein backbone, silver spheres: zinc ions, gray: RNA backbone and sugars, and green: RNA base rings. ZF2 is enlarged on the right to show detail. (A) NMR structure of TIS11d-ARE9 and (B) E157R/E195K-U9. (C) Mean and standard deviation of the distance between the geometric centers of the intercalating aromatic rings within each intercalating base stack. Red: TIS11d-ARE, blue: TIS11d-U9, green: E157R/E195K-U9, and purple: E157R/E195K-ARE.

To determine if the loss of intercalation results from side chain reorientations or movement of the RNA and protein with respect to one another, for each aromatic stack we monitored the distance between the geometric centers of the base rings for each pair within the base stacks [Fig. 8(C)] as well as the angles between the planes of the intercalating RNA bases and protein side chain aromatic rings and the distance between the Cα of the aromatic residue and the phosphorus atom of the nucleotide (data not shown).

ZF1: The base stack U6-Phe176-A(U)7 remains generally intercalated in all simulations, although fluctuations are increased with U7 [Fig. 8(C)]. In TIS11d-U9 and E157R/E195K-U9, however, large variances in the distances from U6 and Phe176 to U7 indicate that motions of the U7 base ring are weakening the intercalation. Side chain motions are responsible for the decreased intercalation of the U8-Tyr170-U9 base stack, except in E157R/E195K-ARE where the hydrogen bond between Lys169 and U9 is conserved.

ZF2: For the U4-Tyr208-U5 stack, in all simulations of E157R/E195K-ARE and E157R/E195K-U9 the aromatic side chain of Tyr208 is not intercalated with the RNA bases as in the simulation of TIS11d-ARE [Fig. 8(C)]. Figure 8(B) shows that the U5 base ring can flip out, which in turn allows Tyr208 more mobility, consistent with the decreased hydrogen bond probabilities discussed above. U2-Phe214-A3 has decreased intercalation in TIS11d-U9 and E157R/E195K-U9. The distance between the rings of Phe214 and U3 increases by over 5 Å in both the E157R/E195K-U9 and TIS11d-U9 trajectories and an increase is also seen in the distance between U2 and U3.

Dynamics and flexibility are increased for TIS11d bound to U9

In addition to the variations in base intercalation described above, the mean order parameters calculated for the backbone NH amide bonds show that TIS11d-U9 has altered flexibility when compared with TIS11d-ARE; the differences are often small, but the errors are as well and the differences are significant. Differences in the order parameter (ΔS2) observed between the free and ARE-bound state have a similar pattern to those observed between TIS11d in complex with U9 and with ARE [Fig. 3(A,B)], indicating that TIS11d is most flexible in the free state, less flexible when bound to U9, and most rigid when bound to ARE  .

.

Protein–RNA interactions differ between E157R/E195K mutant and wild-type TIS11d

The mutation of a negatively charged residue (Glu) to a positively charged residue (Arg/Lys) has a significant effect on the Coulomb interaction between the protein and RNA. Figure 9(A,B) shows a large change in interaction energy in the linking residues and N-terminal tail regions, where the mutated residues are located, for both E157R/E195K-ARE and E157R/E195K-U9. This change is overwhelming compared with the contributions of the two fingers and is the reason the TIS11d mutant protein shows a more favorable total interaction energy with RNA.

Figure 9.

Normalized histograms of protein–RNA Coulomb interaction energy for the N-terminal tail (residues 151–158) and linking residues (residues 179–196) combined. (A) Gray: TIS11d-ARE, black: TIS11d-U9, (B) gray: E157R/E195K-ARE, and black: E157R/E195K-U9.

Both E157R/E195K-ARE and E157R/E195K-U9 have decreased intercalation of the side chain of Tyr208 with U4 and U5. In E157R/E195K-ARE, the hydrogen bond interactions with A3 are reduced relative to that of TIS11d-ARE while the interaction with U3 is absent in both E157R/E195K-U9 and TIS11d-U9. There are fewer differences in the hydrogen bonding interactions and base intercalation of ZF2 observed between E157R/E195K-ARE and E157R/E195K-U9 than between TIS11d-ARE and TIS11d-U9. These results suggest that the E157R/E195K double mutant of TIS11d becomes more promiscuous than the wild-type protein in its RNA binding selectivity by decreasing base-specific interactions while increasing nonspecific Coulomb favorable interactions with the phosphate backbone of the RNA.

Summary and Conclusions

MD simulations of the TZF domain of TIS11d free and bound to two different RNA sequences were performed to identify the key interactions that stabilize TIS11d in the bound and free states, and their role in RNA binding activity. Additional MD simulations of the double mutant E157R/E195K of TIS11d were performed to investigate the effect of primary sequence on RNA binding specificity. The analysis of the trajectories focused on computing quantities to characterize the structure and dynamics of the TZF domain of TIS11d in solution. The results led to the following conclusions.

The TZF domain of TIS11d must undergo a structural rearrangement to bind RNA. The major structural differences between the bound and free states are located in the linker region, while the secondary structure elements are preserved, suggesting that this rearrangement is likely reversible. The compaction of the structure observed in the absence of RNA leads the protein to approach the same amount of SASA as in the protein–RNA complex.

Strong hydrogen bonds in ZF1 between Thr156, Glu(Arg)157, Gln175, and U6 and similarly in ZF2, between Thr194, Glu(Lys)195, His213, and U2 are observed in all simulations with RNA. The existence of these three bonds with the same nucleotide, but involving residues that are separated by 17 residues in the sequence of the protein highlights the critical role played by RNA in preserving the tertiary alignment of the zinc fingers in the bound state of TIS11d. Binding of residues preceding each finger domain as well as a residue near the end of each finger domain to the same nucleotide prevents the rotation of the finger domains that is otherwise observed in the absence of RNA.

Comparison of the structures of wild-type TIS11d in complex with two different RNA sequences, UUAUUUAUU and U9, indicates that when bound to U9, the uridine nucleotide at position 3 is unable to reach the backbone atoms of ZF2 to form stabilizing hydrogen bonds because of the steric hindrance of the intercalating base stacks. Adenosine, in contrast, is a larger nucleotide and does form hydrogen bonds. ZF1 is able to form replacement hydrogen bonds with U7, but they are not as strong as the bonds with A7.

The stacking interactions between the aromatic side chains of residues Tyr170, Phe176, Tyr208, and Phe214 and the RNA bases is a dominant feature of the protein–RNA complex. Any substitution of these residues with nonaromatic amino acids abolishes RNA binding.10 The ability to maintain these interactions seems to play an essential role in determining the RNA sequence specificity of TIS11d. Intercalation is reduced in TIS11d-U9 in the stacking interactions which involve U3 and U7 (formerly A3 and A7). This allows for increased mobility of the intercalated aromatic residues Tyr208 and Phe176, and results in the weakening of the hydrogen bond between Pro207 and RNA.

Wild-type TIS11d is sensitive to the difference in the RNA sequence. This result is in agreement with the experimentally observed binding specificity of TIS11d for the ARE RNA sequence.7 The discriminatory ability appears more pronounced in ZF2, which experiences a complete lack of hydrogen bonding with U3 and decreased intercalation of the U2-Phe214-U3 base stack, while ZF1 has only partial loss of hydrogen bonding with U7 and the intercalation is better maintained in the U6-Phe176-U7 base stack.

Comparison of the structures and hydrogen bonding of the E157R/E195K mutant of TIS11d in complex with two different RNA sequences, UUAUUUAUU and U9, indicates that the adenine recognition pocket is less competent in binding adenine than wild-type TIS11d, and similarly incapable of binding uridine at positions 3 and 7 as wild-type TIS11d.

The stacking interactions between the aromatic side chain of Tyr208 and the RNA bases are not as well ordered in either E157R/E195K-RNA complex and the hydrogen bonds with U5 are also reduced in both complexes.

We suggest that the E157R/E195K double mutant of TIS11d becomes more promiscuous in binding RNA because of the very favorable non-nucleotide-specific Coulomb interaction between the RNA backbone and the mutated residues, which makes any effect of the RNA sequence small compared with the total interaction energy. This result agrees with previous experimental evidence that TIS11d-like specificity can be promoted in MEX-5 by the reverse mutation,11 suggesting that these residues act as discriminators in the interactions with RNA.

These simulation results suggest a fundamental mechanism for adaptation of TIS11d in the apo state in which structural and dynamical changes in the linker region allow burial of hydrophobic surface area of RNA-interacting side chains that would otherwise (in the absence of RNA) have an energetically unfavorable exposure to the solvent. In addition to importance for understanding TIS11d affinity and specificity, these results may point to a more general mechanism for multidomain proteins ubiquitous in regulatory networks, where structural compaction may regulate the affinity for different binding partners.

The strongest hydrogen bonds with adenine bases observed in our computational studies are formed by residues immediately following the adenine recognition binding pockets (Arg160 and Arg198). In addition, Glu157 and Glu195 are shown to form strong bonds with U6 and U2, along with the preceding residues Thr156 and Thr194. The mutations E157R and E195K do not alter these binding interactions. These results highlight the importance of other residues, in addition to those of the adenine recognition pocket, in stabilizing the interaction of TIS11d with RNA.

Structural and dynamical changes were observed between the wild-type TIS11d and the double mutant E157R/E195K in complex with two different RNA sequences. These results indicate that structure and dynamics together determine the ability the TZF domain of TIS11d to discriminate between different RNA sequences. The widespread differences in the interactions of E157R/E195K with RNA exemplify that dynamics can propagate small changes, such as a single residue mutation, much more globally than might be expected; as such, dynamics are a fundamental aspect in understanding binding interactions.

Our studies suggest that the specificity of the wild-type protein can be tied to a less favorable interaction of the protein with the RNA backbone phosphate groups, which makes small changes in interactions such as hydrogen bonds and base intercalation, due to sequence differences, more influential in determining the overall strength of the interaction. Promiscuity, on the other hand, is enhanced by a non-nucleotide-specific favorable electrostatic interaction. The more favorable protein–RNA interaction energy might allow the mutant protein to bind to a wider range of sequences with similar affinity. Thus, high affinity due to favorable Coulomb interactions with the RNA backbone is less effective in promoting RNA binding specificity—it renders the finer details of the interaction negligible.

Elucidation of the critical RNA regulatory function of this protein requires a detailed understanding of the molecular basis for RNA binding specificity. This goal is best achieved using a combination of experimental and computational techniques. While this report details the results of our computational studies of TIS11d, experimental work is underway to test these theoretical results in solution using NMR spectroscopy.

Methods

Simulation protocol

We modeled the unknown structure of ligand-free TIS11d, starting from two representative models of the NMR solution structure of TIS11d bound to ARE (UUAUUUAUU),9 by removal of the RNA sequence followed by energy minimization and equilibration. Mutations of the RNA sequence (A3U, A7U) were implemented by direct modification of the bases and mutations of the protein (E157R, E195K) were made with PyMOL17 using the lowest energy NMR structure. All structures were solvated and neutralized in a TIP3P water box using VMD.18 Structural optimization and MD simulations were subsequently carried out using the NAMD2.6 molecular modeling package19 and the CHARMM27 force field.20 Both a nonbonded representation to model the zinc interactions21 and a nonbonded model that included charge transfer and local polarization effects22 were used. Simulations that used a fixed charge nonbonded representation of the zinc ions21 were not able to maintain the tetrahedral coordination geometry for the zinc ions, which became trigonal bipyramidal in the presence of RNA, and octahedral in the absence of RNA. For simulations that used a polarizable model for Zn2+, van der Waals parameters were taken from set A (Table II) of Sakharov and Lim.22 In these simulations, the tetrahedral coordination geometry of the zinc ions, observed in all crystal structures of zinc finger proteins and those of most enzymes, was maintained. Only the structures obtained from these simulations of the TIS11d-ARE complex accurately reproduce the zinc-ligand distances and angles measured in the NMR structure.9 For this reason, only these trajectories were used in the data analysis presented in this article. Although the tetrahedral coordination geometry for the zinc ions was not maintained in the simulations lacking charge transfer and polarization effects of Zn2+, the overall protein and RNA structures, dynamics and energetics observed in these fixed charge simulations are consistent with those obtained from the polarizable model for Zn2+.

After energy minimization, particle velocities were randomly assigned from the Maxwell distribution and the system was simulated in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble. A constant temperature of 298 K and pressure of 1 atm were maintained using Langevin dynamics and the Nosé–Hoover Langevin piston method. The SHAKE constraint algorithm23 was used, thereby allowing the equations of motion to be integrated using a 2 fs time step. Nonbonded interactions were calculated every time step with a cut-off distance of 12 Å and a switching distance of 10 Å. The particle mesh Ewald method was used to treat electrostatic interactions using periodic boundary conditions. After equilibration in the isothermal-isobaric ensemble, an additional stage of equilibration was performed in the microcanonical ensemble, with velocity reassignment to ensure that the temperature stabilized to the desired value. While the thermodynamic values are equilibrated at this point, structural equilibration is not complete, particularly in the case of the free structures. The simulations were run in the microcanonical ensemble until the conformations were judged equilibrated as quantified primarily by RMSD from the original structure and radius of gyration. On average it took about 20 ns to achieve structural equilibration for free TIS11d, at this point we collected two independent, 8 ns trajectories that were used for data collection and analysis. An additional 10 trajectories of 20–30 ns for free TIS11d were generated using a nonbonded representation to model the zinc interactions21 to see if the patterns observed in these trajectories persisted. These trajectories show evidence of effects similar to those seen with a nonbonded model for zinc that included charge transfer and local polarization effects.22 None of the trajectories using the fixed charge nonbonded model for zinc were used for data analysis. Structures bound to RNA equilibrated much more rapidly and all bound trajectories were considered equilibrated at 6 ns. Two trajectories of TIS11d-ARE and three trajectories each of TIS11d-U9, E157R/E195K-ARE, and E157R/E195K-U9 were collected. The trajectories were run for a total of 14 ns, with the last 8 ns used for data collection and analysis.

Measures of protein structure and dynamics

Structural characterization

The quantities used to characterize the structural changes and dynamics were calculated using VMD18 to process the trajectories and generate the values used to calculate the reported statistics. Visualization of structures was also done in VMD, using the STRIDE method.24

Root mean square displacement (RMSD) is calculated using the original NMR structure as the point of reference, after applying a RMS fit to minimize the contribution from global rotations. The distance between the Cα of residues 179 and 196 defines the end-to-end distance. Radius of gyration, as implemented in VMD, follows the standard form.25

Characterization of the solvent accessible surface area

Calculations of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) use the method provided by VMD, originally implemented by Varshney, Brooks and Wright,26 with a probe radius of 1.4 Å. This method allows the user to define what should not be considered as solvent (i.e., which atoms may contribute to the shielding). The SASA when calculated in simulations with RNA can have two definitions. The definition of what is not considered solvent is first the protein only (equivalent to deleting the RNA from the trajectories before calculating the SASA). Then, both the RNA and the protein are considered as not solvent. In Figure 2(D), black corresponds to the SASA calculated using the first definition (protein only) and red using the second (protein and RNA).

Characterization of internal motions: Lipari–Szabo order parameters

The generalized order parameters, S2, were calculated to characterize the internal motions of the protein.13,27 S2 was calculated separately for each trajectory; the mean and standard deviation of the order parameters among the trajectories are reported in Figure 3. The orientation of a peptide backbone amide bond vector can be described by a time correlation function, C(t). Assuming that the internal motions are uncorrelated with the overall molecular tumbling, C(t) can be separated into two contributions: one for the internal motions, Cint(t), and the other for the overall molecular rotation, Ctumb(t),

| (1) |

Cint(t) is given by

|

(2) |

where Y2m(θ, φ) are the second order spherical harmonics and θ and φ are the spherical polar angles that specify the orientation of the internuclear NH amide bond vector in the molecule-fixed coordinate frame. The internal motion of the internuclear NH amide bond vector can be characterized by the two parameters S2, a generalized order parameter, and τint, an effective correlation time, defined as

| (3) |

and

|

(4) |

where T is the time after which Cint(t) = S2, and Cint(0) is the value of the internal correlation function at time zero. S2 is a measure of the degree of freedom of the motion of the intermolecular amide bond vector; S2 is equal to 1 if the motion is completely restricted and is equal to 0 for isotropic motion. To separate the overall molecular rotation from the internal motion, a RMS fit was minimized with respect to a reference configuration (t = 0).

Definition of hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonds are defined by the distance between the donor and the acceptor being less than a cut-off of 4.0 Å and the angle between the donor and acceptor groups must be within 113–180°.28 This was the most stringent cut-off possible such that the mean distance between the hydrogen and the acceptor of the bonds reported by Wright et al.9 were within the cut-off for the 20 original NMR structures, excluding hydrogen bonds involving sulfur.

Measures of aromatic side chain-RNA base ring interactions

The centers of the intercalating rings are defined as the center of mass of atoms Cγ, Cδ1, Cδ2, Cɛ1, Cɛ2, and Cζ for aromatic residues and atoms C4, N3, C2, N1, C6 and C5 for nucleotides. The distance between two rings is defined as the magnitude of the vector connecting their centers. For example, base stack U4-Tyr208-U5 would have the two vectors

| (5) |

Quantification of protein–RNA interaction energetics

Energy calculations were performed on the last 2 ns of the trajectories using the pairInteraction option in NAMD.19 The Coulombic term of the interaction energy is shown in Figure 9. The normalized histograms were generated using the combined data of the four sets of simulations with RNA.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank William E. Royer and Troy W. Whitfield for critical comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- ARE

AU-rich element

- COM

center of mass

- MD

molecular dynamics

- NAMD

nanoscale molecular dynamics

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- U9

polyuridine nonamer

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- SASA

solvent accessible surface area

- TTP

tristetraprolin

- TZF

tandem zinc finger

- UTR

untranslated region

- VMD

visual molecular dynamics

- ZF1

zinc finger 1

- ZF2

zinc finger 2

References

- 1.Ogilvie RL, Abelson M, Hau HH, Vlasova I, Blackshear PJ, Bohjanen PR. Tristetraprolin down-regulates IL-2 gene expression through AU-rich element-mediated mRNA decay. J Immunol. 2005;174:953–961. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrick DM, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. The tandem CCCH zinc finger protein tristetraprolin and its relevance to cytokine mRNA turnover and arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:248–264. doi: 10.1186/ar1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CY, Gherzi R, Ong SE, Chan EL, Raijmakers R, Pruijn GJ, Stoecklin G, Moroni C, Mann M, Karin M. AU binding proteins recruit the exosome to degrade ARE-containing mRNAs. Cell. 2001;107:451–464. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai WS, Carballo E, Strum JR, Kennington EA, Phillips RS, Blackshear PJ. Evidence that tristetraprolin binds to AU-rich elements and promotes the deadenylation and destabilization of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4311–4323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:945–952. doi: 10.1042/bst0300945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewer BY, Malicka J, Blackshear PJ, Wilson GM. RNA sequence elements required for high affinity binding by the zinc finger domain of tristetraprolconformational changes coupled to the bipartite nature of AU-rich MRNA-destabilizing motifs. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27870–27877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402551200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai WS, Carballo E, Thorn JM, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA. Binding of tristetraprolin-related zinc finger proteins to AU-rich elements and destabilization of mRNA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17827–17837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson BP, Martinez-Yamout MA, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Recognition of the mRNA AU-rich element by the zinc finger domain of TIS11d. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:257–264. doi: 10.1038/nsmb738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai WS, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA: non-binding tristetraprolin mutants exert an inhibitory effect on degradation of AU-rich element-containing mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9606–9613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagano JM, Farley BM, McCoig LM, Ryder SP. Molecular basis of RNA recognition by the embryonic polarity determinant MEX-5. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8883–8894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700079200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoecklin G, Tenenbaum SA, Mayo T, Chittur SV, George AD, Baroni TE, Blackshear PJ, Anderson P. Genome-wide analysis identifies interleukin-10 mRNA as target of tristetraprolin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11689–11699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. I. Theory and range of validity. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4546–4559. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wesson L, Eisenberg D. Atomic solvation parameters applied to molecular dynamics of proteins in solution. Protein Sci. 1992;1:227–235. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee B, Richards FM. Interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J Mol Biol. 1971;55:379–400. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90324-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregoret LM, Rader SD, Fletterick RS, Cohen FE. Hydrogen bonds involving sulfur atoms in proteins. Proteins. 1991;9:99–107. doi: 10.1002/prot.340090204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD—Visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacKerell AD, Bashford D, Bellott M, Dunbrack RL, Evanseck JD, Field MJ, Fischer S, Gao J, Guo H, Ha S, Joseph-McCarthy D, Kuchnir L, Kuczera K, Lau FTK, Mattos C, Michnick S, Ngo T, Nguyen DT, Prodhom B, Reiher WE, Roux B, Schlenkrich M, Smith JC, Stote R, Straub J, Watanabe M, Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera J, Yin D, Karplus M. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J Phys Chem B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stote RH, Karplus M. Zinc binding in proteins and solution: a simple but accurate nonbonded representation. Proteins. 1995;23:12–31. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakharov DV, Lim C. Zn protein simulations including charge transfer and local polarization effects. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4921–4929. doi: 10.1021/ja0429115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J Comput Phys. 1997;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frishman D, Argos P. Knowledge-based secondary structure assignment. Proteins. 1995;23:566–579. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berne BJ, Pecora R. Dynamic light scattering. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varshney A, Brooks FP, Wright WV. Linearly scalable computation of smooth molecular surfaces. IEEE Comp Graphics Appl. 1994;14:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-Free approach to the interpretation of nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation in macromolecules. I. Analysis of experimental results. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4559–4570. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simmerling C, Elber R, Zhang J. A program for visualization of structure and dynamics of biomolecules and STO-a program for computing stochastic paths. Netherlands: Kluwer; 1995. [Google Scholar]