Abstract

Prestin is a member of the SLC26 family of anion transporters and is responsible for electromotility in outer hair cells, the basis of cochlear amplification in mammals. It is an anion transporting transmembrane protein, possessing nine cysteine residues, which generates voltage-dependent charge movement. We determine the role these cysteine residues play in the voltage sensing capabilities of prestin. Mutations of any single cysteine residue had little or no effect on charge movement. However, using combinatorial substitution mutants, we identified a cysteine residue pair (C415 and either C192 or C196) whose mutation reduced or eliminated charge movement. Furthermore, we show biochemically that surface expression of mutants with markedly reduced functionality can be near normal; however, we identify two monomers of the protein on the surface of the cell, the larger of which correlates with surface charge movement. Because we showed previously by Förster resonance energy transfer that monomer interactions are required for charge movement, we tested whether disulfide interactions were required for dimerization. Using Western blots to detect oligomerization of the protein in which variable numbers of cysteines up to and including all nine cysteine residues were mutated, we show that disulfide bond formation is not essential for dimer formation. Taken together, we believe these data indicate that intramembranous cysteines are constrained, possibly via disulfide bond formation, to ensure structural features of prestin required for normal voltage sensing and mechanical activity.

Introduction

Prestin (SLC26A5) is a member of the SLC26 family of anion transporters (1). It is now well established that this protein is responsible for electromotility in mammalian outer hair cells (OHC), which are believed to be responsible for cochlear amplification (2–5). Prestin is a membrane protein of 744 amino acids (1). A large central core of the protein is predicted to traverse the membrane multiple times based on hydrophobicity analysis (1,6). The number of predicted transmembrane regions varies (10 or 12), and is dependent on the different prediction paradigms (1,6–8). It also has a small N-terminus and a larger C-terminus that are thought to be intracellular (6,9). Prestin has piezoelectric properties; membrane voltage controls its conformation (10–13). Its voltage sensitivity arises from voltage sensor charge movement within the membrane that can be measured as a nonlinear capacitance (NLC) (14–16).

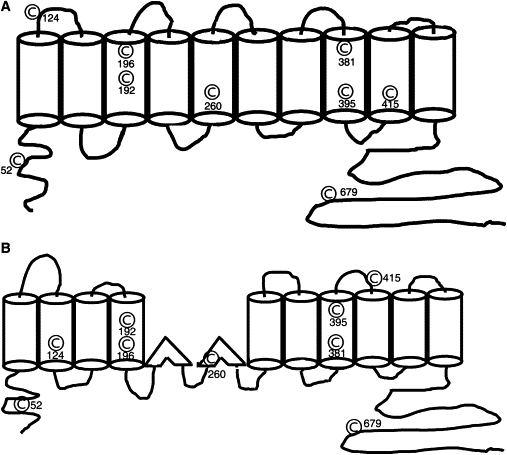

Prestin contains nine cysteine residues (1). Of these nine residues, six (C192, C196, C260, C381, C395, and C415) lie in areas that are potential transmembrane regions (1,6,7). Of the remaining three, two (C52 and C679) are located in the intracellular N- and C-termini, respectively, whereas the remaining cysteine (C124) residue lies in a loop connecting two potential transmembrane regions (Fig. 1). Cysteine residues, because of their ability to form disulfide bonds, can play a number of roles in a protein's function (17,18). Disulfide bond formation is a covalent posttranslational modification that occurs concurrent with translation. Disulfide bonds can be structural, catalytic, or allosteric (17–19). Structural bonds stabilize the structure of the protein by decreasing the entropy of the unfolded (denatured) protein (18). Catalytic disulfide bonds help in catalyzing enzyme reactions. The best known of these is found in oxidoreductases where a catalytic disulfide bond is found in its thioredoxin-like fold. Allosteric disulfide bonds, in contrast, modulate a protein's function (19). Cleavage of allosteric disulfide bonds results in a change in the protein's tertiary or quaternary structure and its function (19).

Figure 1.

Nine cysteine residues are distributed throughout the protein. A cartoon of the two different transmembrane models are shown along with the position of individual cysteine resides in these two models. (A) Ten transmembrane model. (B) Twelve transmembrane model. Six of these residues (C192, C196, C260, C381, C395, C415) lie within hydrophobic transmembrane regions of the protein. Two residues (C52 and C679) lie in the predicted intracellular amino and carboxy termini of the protein, respectively, and the last residue (C124) lies in a loop connecting two transmembrane regions in the 10 transmembrane model.

Tests for disulfide bond formation often involve functional assays of proteins, for example, membrane transport (20). In native OHCs, measures of NLC or mechanical activity have been used (21,22). Preliminary exploration of disulfide bonds in the structure and function of prestin has provided a number of insights. It has been reported that mutation of individual cysteine residues did not adversely affect its charge movement (23,24). Other work has implicated disulfide bonds formed by one or more cysteine residues in the transmembrane regions of prestin as important for dimerization of the protein (25). Here, we systematically mutated cysteine residues individually and in combination, and then determined how mutations affect characteristics of NLC (see Materials and Methods). These characteristics include the density of voltage sensor charge (Qsp), the voltage at peak capacitance (Vh), and unitary charge valence (z). Qsp is an estimate of functional motors within a unit membrane surface area, Vh is a metric of the steady-state energy profile, and z is an estimate of charge moved within an individual motor. We also explored the role of these cysteine residues in the formation of prestin multimers. Our data show that mutation of individual cysteine residues has little or no effect on the function of prestin. However, our combinatorial data show profound changes in the function of prestin, providing evidence that cysteine residues (namely, C415 and either C192 or C196) in prestin potentially form disulfide bonds. Finally, we show that disulfide bond formation is not necessary for the formation of prestin multimers.

Materials and Methods

cDNA constructs and generation of mutants

Single or multiple amino acid substitutions were generated using QuickChange II or QuickChange II Multi site-directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with a gerbil prestin-YFP in pEYFPN1 vector (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) as a template. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing, including the entire coding region.

Transient transfections in Chinese hamster ovary cells

For electrophysiological recordings 100,000 Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transfected in 24-well plates with the cysteine mutants using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as described previously (7).

Electrophysiological recording

Cells were recorded by whole-cell patch clamp configuration at room temperature using an Axon 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA), as described previously (7). Cells were recorded 24–48 h after transfection to allow for stable measurement of NLC. Ionic blocking solutions were used to isolate capacitive currents. The bath solution contained (in mM): TEA 20, CsCl 20, CoCl2 2, MgCl2 1.47, Hepes 10, NaCl 99.2, CaCl2·2H2O 2, pH 7.2, and the pipette solution contained (in mM): CsCl 140, EGTA 10, MgCl2 2, Hepes 10, pH 7.2. Osmolarity was adjusted to 300 ± 2 mOsm with dextrose. Command delivery and data collections were carried out with a Windows-based whole-cell voltage clamp program, jClamp (Scisoft, Ridgefield, CT), using a Digidata 1322A interface (Axon Instruments).

Capacitance was evaluated using a continuous high-resolution 2-sine wave technique, fully described elsewhere (26,27). Capacitance data were fitted to the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function (16):

where

Qmax is the maximum nonlinear charge transfer, Vh the voltage at peak capacitance or half-maximal nonlinear charge transfer, Vm the membrane potential, Clin linear capacitance, z the valence (a metric of voltage sensitivity), e the electron charge, k the Boltzmann constant, and T the absolute temperature. Qmax is reported as Qsp the specific charge density, i.e., total charge moved normalized to linear capacitance. Where necessary we increased the range of voltage commands to test mutants in which Vh was extreme. A Student's t-test was used to evaluate the effects of mutants on the different parameters of NLC. In mutants where Qsp was immeasurable, namely zero, we state, for presentation purposes, that the significance of differences with prestin that had NLC was <0.01, although the probability of a difference between these data would be infinitely small.

It should be noted that measures of Qsp, Vh, and z in CHO cells are in line with our previous work. Measures of Qsp in CHO cells are in the lower range of that recorded in HEK cells. However, Vh in CHO cells (−120 to −100 mV) is significantly negative compared to prestin expressed in HEK cells (−50 to −70 mV).

Western blots

Crude lysates were generated from transiently transfected CHO cells after 24–48 h. Lysates were separated on a precast 4–15% Tris-HCl SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) or a 5–8% urea-SDS PAGE containing 6 M urea. Samples were incubated with and without reducing agents where indicated. Two reducing agents, β-mercaptoethanol and ethanedithiol (EDT), were added to the samples at final concentrations of 200 mM and 600 mM, respectively. Proteins were transferred by wet transfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Western blots were probed with anti-prestin-N20 (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) at a 1:500 dilution and then with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated bovine anti-goat secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) at 1:5000 dilution with TBST washing (×5) in between. The presence of HRP conjugated antibody was detected using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermoscientific/Pierce, Rockford, IL). Where indicated, the blots were stripped using Restore plus Western stripping buffer and reprobed with prestin C-16 antibody (Santa Cruz) at a 1:500 dilution and HRP conjugated bovine anti-goat secondary antibody at a 1:5000 dilution.

Prestin surface expression

Surface expression of prestin was determined using a surface biotinylation assay (Thermoscientific/Pierce). Transiently transfected CHO cells were analyzed 24 h after transfection. These cells were washed with PBS, and incubated in the presence of sulfo-NHS-biotin for 30 min at 4°C. Free sulfo-NHS-biotin was quenched by washing cells in 140 mM Tris-Cl, and the cells lysed in lysis buffer containing (mM): Tris 20, pH 8.0, NaCl 137, NaEDTA 5, NaEGTA 5, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, PMSF 0.2, NaF 50, benzamidine 20. The lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and its protein concentration assayed (Bio-Rad) and equalized. Streptavidin agarose was added in the mixtures, incubated 1 h at room temperature with constant agitation. After centrifugation at 1000 × g the beads were washed with washing buffer. The bound surface proteins were released by addition of 50 mM dithiothreitol and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting as described above. In several experiments we also sorted cells by fluorescent activated cell sorting and determined that there was no consistent difference in transfection efficiency between different mutants. Similarly, there was no difference in the ratio between the upper to lower monomer within a given mutant irrespective of whether or not cells were sorted before labeling of cell surface proteins.

Results

Substitution of single cysteine residues did not abolish NLC

To ascertain which cysteine residues are important for the structure and function of prestin, we substituted each of the nine individual cysteine residues with a serine residue. We reasoned that substituting cysteine with a serine residue, which has the identical side chain length (thereby minimizing confounding effects from side chain interactions), was a good method to determine the role of disulfide bonds in the function of the protein. NLC characteristics of three single point cysteine mutations differed significantly from wild-type prestin (Table 1). These were C415S which had a significant change in Qsp (2.45 ± 0.81 fC/pF vs. 7.88 ± 1.26 fC/pF), and C196S and C395S that had changes in Vh (−130.14 ± 3.22 mV and −58.51 ± 4.68 mV, respectively, versus −111.30 ± 2.94 mV in control).

Table 1.

Mean NLC parameters of single cysteine to serine mutations and number of cells recorded for each mutant

| Single mutants | NLC parameter |

n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qsp | Vh | z | ||

| Wild-type prestin | 7.88 ± 1.26 | −111.30 ± 2.94 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 25 |

| C52S | 6.49 ± 0.92 | −111.03 ± 4.31 | 0.70 ± 0.05 | 5 |

| C124S | 10.18 ± 4.03 | −111.05 ± 4.30 | 0.68 ± 0.03 | 6 |

| C192S | 5.87 ± 0.74 | −109.72 ± 6.41 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 6 |

| C196S | 6.50 ± 1.00 | −130.14 ± 3.22∗ | 0.68 ± 0.01 | 8 |

| C260S | 4.16 ± 0.49 | −110.11 ± 5.43 | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 4 |

| C381S | 8.72 ± 1.06 | −97.07 ± 7.39 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 5 |

| C395S | 5.37 ± 0.82 | −58.51 ± 4.68∗ | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 7 |

| C415S | 2.45 ± 0.81∗ | −117.11 ± 9.47 | 0.71 ± 0.06 | 7 |

| C679S | 7.64 ± 1.54 | −107.78 ± 9.57 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 5 |

Values that show statistically significant differences from wild-type prestin are indicated.

p < 0.05.

Substitution of two or more cysteine residues does not alter prestin surface expression, but rather folding of monomers with adverse affects on Qsp

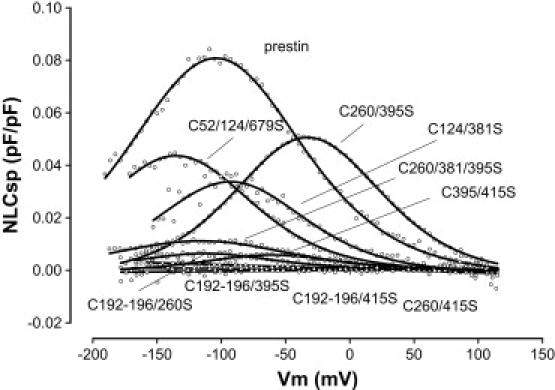

Our data that mutations of individual cysteine residues do not eliminate NLC suggest several possibilities. First, there may be no disulfide bonds. Second, disulfide bonds are not crucial for the generation of NLC. Third, one disulfide bond is able to compensate for the loss of another disulfide bond. Our experiments thus far are unable to rule out the first two possibilities. Attempts in our lab to purify adequate amounts of prestin expressed in mammalian expression systems for analysis by mass spectrometry have not been successful. To test the third possibility, we mutated cysteine residues in varying combinations and determined their effects on NLC (Fig. 2 and Table 2). These data show that mutation of more than one cysteine residue in the nontransmembrane regions had no effect on NLC. Thus, the combination of mutations C52S, C124S, and C679S has preserved NLC (namely, no significant changes in Qsp, and z, although there were some significant effects on Vh). In contrast, several combinations of two or more transmembrane cysteine mutations could abolish NLC.

Figure 2.

Representative NLC traces of wild-type prestin and several combinatorial cysteine mutants. These individual combinations are representative of the variable effects on different aspects of NLC produced by these mutants. Only select combinations were able to markedly reduce NLC (see text and Table 2 for details).

Table 2.

Mean NLC parameters of the different combinatorial cysteine mutants and number of cells recorded for each mutant

| Mutants | NLC parameter |

n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qsp | Vh | z | ||

| Wild-type prestin | 7.88 ± 1.26 | −111.30 ± 2.94 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 25 |

| C192/196/395S | 0 | 20 | ||

| C192/196/415S | 0 | 11 | ||

| C260/415S | 0 | 18 | ||

| C381/415S | 0 | 15 | ||

| C192/196S | 1.97 ± 0.22∗ | −127.58 ± 3.49∗ | 0.60 ± 0.03∗ | 6 |

| C192/196/381S | 0.89 ± 0.09∗ | −123.36 ± 12.48 | 0.69 ± 0.08 | 4 (18) |

| C192/381S | 5.11 ± 1.16 | −118.12 ± 7.34 | 0.65 ± 0.04 | 6 |

| C196/381S | 3.49 ± 0.66 | −119.37 ± 7.27 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 7 |

| C192/395S | 1.98 ± 0.58∗ | −77.94 ± 9.63† | 0.68 ± 0.04 | 7 |

| C196/395S | 3.35 ± 0.73 | −90.29 ± 6.01∗ | 0.67 ± 0.04 | 7 |

| C192/196/260S | 1.55 ± 0.32∗ | −119.20 ± 2.91 | 0.62 ± 0.04∗ | 6 (16) |

| C192/260S | 3.78 ± 0.58 | −107.03 ± 4.15 | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 7 |

| C196/260S | 4.14 ± 0.75 | −119.35 ± 3.26 | 0.67 ± 0.02 | 7 |

| C192/415S | 1.00 ± 0.26∗ | −141.90 ± 5.72† | 0.63 ± 0.05∗ | 5 (16) |

| C196/415S | 1.24 ± 0.47∗ | −125.59 ± 8.08 | 0.63 ± 0.02† | 6 (21) |

| C192/196/124S | 1.20 ± 0.24∗ | −124.29 ± 1.62∗ | 0.66 ± 0.04 | 6 |

| C381S/C415A | 5.78 ± 1.56 | −90.24 ± 6.87† | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 6 |

| C395/415S | 0.86 ± 0.16∗ | −56.46 ± 3.36† | 0.70 ± 0.02 | 5 (20) |

| C395S/C415A | 3.67 ± 0.66 | −31.99 ± 8.03† | 0.62 ± 0.02† | 8 |

| C192S/C196S/C415A | 1.83 ± 0.46∗ | −100.06 ± 4.1 | 0.69 ± 0.04 | 5 |

| C52/124/679S | 5.21 ± 1.38 | −136.00 ± 7.28∗ | 0.65 ± 0.02 | 5 |

| C260/381/395S | 1.62 ± 0.20∗ | −102.85 ± 9.52 | 0.50 ± 0.02† | 7 |

| C260/381S | 3.36 ± 0.44 | −115.18 ± 7.44 | 0.64 ± 0.03 | 6 |

| C260/395S | 5.44 ± 1.25 | −53.04 ± 4.38† | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 12 |

| C260S/C415A | 4.22 ± 0.80 | −86.47 ± 5.18† | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 6 |

| C124/260S | 6.99 ± 1.20 | −110.82 ± 6.12 | 0.72 ± 0.03 | 6 |

| C124/381S | 3.21 ± 0.75 | −115.88 ± 9.27 | 0.67 ± 0.06 | 7 |

| C124/395S | 6.33 ± 1.54 | −66.10 ± 4.59† | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 5 |

In mutants where the percentage of transfected cells that showed NLC was <90%, the fraction of cells with demonstrable NLC is shown. Values that show statistically significant differences from wild-type prestin are indicated. Because z the estimated charge carried by a single motor is not significantly changed, the reduction in Qsp (representing the total charge carried by all the motors per unit area of membrane) suggests that the total number of functional motors on the surface is reduced.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01).

Two opposing transmembrane models for prestin exist for which structural data are of insufficient resolution to choose between (6–8,28). Interestingly, our observations on transmembrane cysteine mutations might help to choose between models, because the 10- and 12-transmembrane models predict potential physical approximations of different cysteine residues, with the implication that they could more likely form disulfide bonds (Fig. 1). An attempt to rationalize our data given the constraints of either model was not definitive, however, and we expect that higher resolution structural studies will be needed to answer this question.

We also used our mutational data to model the formation of disulfide bonds removed from the spatial constraints of the two transmembrane models. Thus, the combinations C260S/C415S and C192S–C196S/C395S that both lost NLC raised the possibility that residue C260 could form a disulfide bond with C192–C196 or C395, and C415 form a second disulfide bond with the remaining cysteine residue (either C192–C196 or C395). To test this hypothesis we made the following combination of mutants: C260S/C395S, C395S/C415S, C192S–C196S/C260S and C192S–196S/C415S. Of these combinations, only the latter abolished NLC. This result is consistent with the possible formation of disulfide bonds between C415 and C395, and separately C192–C196 and C260. However, the preserved NLC in C260S/C395S (and reduced NLC in C192S–C196S/260S, and separately, C395S/C415S) rules out this possibility.

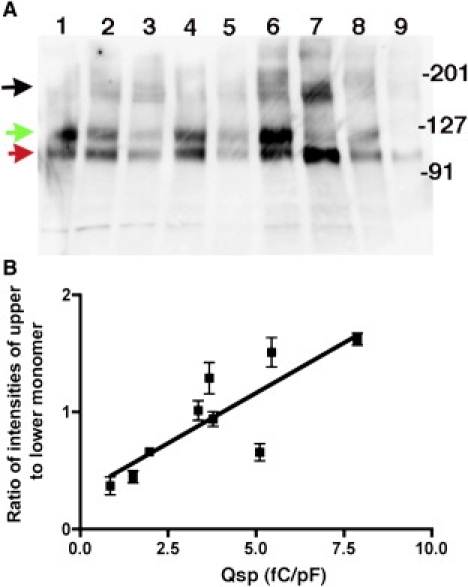

We reasoned that the loss of NLC in prestin mutants could result from inadequate surface expression of the mutated protein, subtle alterations in structure in a protein adequately expressed on the surface of the cell, or a combination thereof. We used a surface biotinylation assay to determine surface expression of prestin in wt prestin and several mutants that showed variation in Qsp. In this procedure, prestin or individual mutants of prestin were expressed transiently in CHO cells, and surface proteins labeled using Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin, a cell impermeable cleavable biotinylation reagent. Surface labeled proteins were isolated from the lysed cells and the presence of prestin detected by Western blot (Fig. 3). Wild-type prestin contained dimeric protein and two forms of monomeric protein with the larger form of the monomer dominating. In contrast, all the mutants that had reduced Qsp showed both monomers with the smaller form dominating in those mutants where Qsp was most decreased. Indeed, in mutants that lacked NLC there was a profound decrease in the larger monomeric form. Moreover, there was a linear relationship between Qsp of individual mutants and their respective ratios of the upper monomeric form to the lower monomeric form (Fig. 3). Both monomers were detected with antibodies to the N-terminus of prestin and after stripping and reprobing with antibodies to the C-terminus of prestin (data not shown), suggesting that the smaller form of the protein was misfolded, not truncated. Importantly, when we used fluorescence activated cell sorting to isolate transfected cells we noted no difference in prestin expression determined by YFP fluorescence between mutants with reduced or absent NLC and wt-prestin (data not shown). Moreover, there were similar levels of prestin expression on the membrane of mutants with reduced NLC (Fig. 3). The remarkable difference in these mutants, as noted above, was that they predominantly expressed the smaller monomer. Together these data suggest a subtle misfolding of the protein, but not inadequate surface expression, as a cause for reduced Qsp in these mutants.

Figure 3.

Prestin and nonfunctional cysteine mutants of prestin are expressed on the surface of the cell. (A) To ascertain if mutations in cysteine residues allowed surface expression, we assayed prestin expressed on the surface of the cell using a surface biotinylation assay. CHO cells were transiently transfected with prestin-YFP constructs. Plasma membrane proteins in these cells were labeled using the cell impermeable amino reactive agent, Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin. Surface proteins were isolated using avidin Sepharose beads and the avidin bound protein released by cleavage with dithiothreitol. The released surface proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and the presence of prestin detected by Western blots using an antibody to an epitope in prestin's N-terminus (and separately to its C-terminus; data not shown). The total protein loaded on each column was the same. The lanes from left to right along with their respective Qsp values and ratios of upper to lower monomer intensities ± SE (n = 3) are: 1), wt-prestin (7.88 fC/pF; 1.62 ± 0.09); 2), C192S/C381S (5.11 fC/pF; 0.67 ± 0.12); 3), C192S/C196S (1.97 fC/pF, 0.66 ± 0.04); 4), C260S/C381S (3.36 fC/pF, 1.01 ± 0.14); 5), C192S/ C260S (3.78 fC/pF, 0.94 ± 0.1); 6), C260S/C395S (5.44 fC/pF, 1.51 ± 0.22); 7), C395S/C415S (0.86 fC/pF, 0.37 ± 0.13); 8), C395S/C415A (3.67 fC/pF, 1.28 ± 0.23), and 9), C192S/C196S/C260S (1.5 fC/pF, 0.447 ± 0.09). The positions of the molecular weight markers are indicated on the right. As is evident, there are two monomeric forms of prestin-YFP at ∼120 kD in wild-type prestin and the multiple cysteine mutants, although the relative proportions between the two monomeric forms varied in the different cysteine mutants. The upper functional monomer is indicated by a green arrow, whereas the lower nonfunctional monomer is indicated by the red arrow. Prestin dimers shown in black (at ∼250 kD) were present in all the mutants. Furthermore, the total amount of prestin monomers and dimers on the surface of the cell were similar, suggesting that there were no deficiencies in trafficking to the surface. (B) Plot of the relationship between Qsp of individual mutants and the ratio between the upper and lower monomers. The intensities of the different bands were quantified using a BioRad ChemiDoc XRS imaging system. The ratios represent the average of three experiments.

Line scan maps suggest the presence of three dimers (potentially from upper monomer–upper monomer, upper monomer–lower monomer, and lower monomer–lower monomer). However, although there was an impression that the ratio of the three different dimers in the different mutants related to that of the two monomers, the gels had insufficient resolution to consistently separate the different bands with three distinct peaks. We are therefore unable to quantify the expression of different prestin dimers and their relationship to Qsp. This is unfortunate because other work indicates that dimers form the functional motor subunit of the protein (7,29).

Cysteine 192 substitutes for cysteine 196, suggesting the formation of disulfide bonds

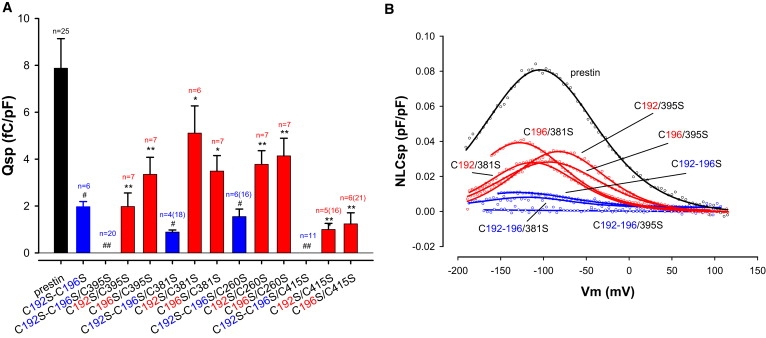

The two residues C192 and C196 lie in an α helix and would therefore be predicted to lie in close proximity to one another in 3D space. We therefore hypothesized that C192 could substitute for C196 (and vice-versa) in forming disulfide bonds. NLC in C192S/C395S and C196S/C395S mutants (as pointed out above C192S–C196S/C395S lacked NLC) was assayed. As shown in Fig. 4, mutation of C395S with either C192S or C196S resulted in a recovery in NLC. Similarly, there was recovery of NLC when C381S was mutated with either C192S or C196S; in contrast, C381S/C192S–C196S had severely decreased NLC (Table 2). In keeping with this pattern, two other combinations of mutants (C192S–C196S/C260S and C192S–C196S/C415S) that had reduced or absent NLC, showed recovery in Qsp when mutated with either C192 or C196, alone. Thus C192S/C260S, C196S/C260S, C192S/C415S, C196S/C415S all restored Qsp (Fig. 4). We interpret these data to signify the formation of disulfide bonds by either C192 or C196. C192S–C196S was the only mutant that showed significant alteration in Qsp, Vh, and z. Moreover, any combinatorial mutation that included C192S–C196S showed absent or significantly reduced Qsp. These data reinforce our conclusion that either residue C192 or C196 forms a disulfide bond.

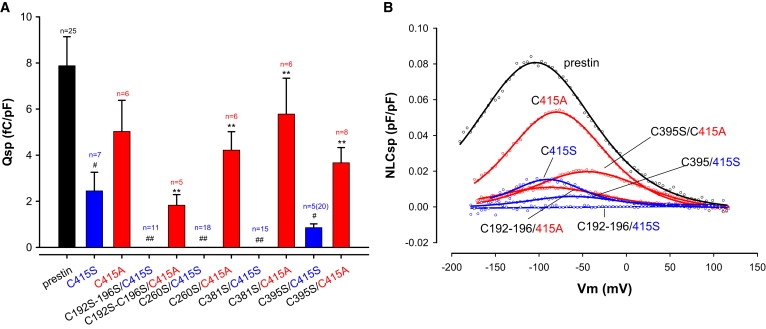

Figure 4.

C192 and/or C196 play a key role in generating NLC. (A) Qsp values of C192S–C196S related mutants are shown. Mutating C192S–C196S together markedly decreases Qsp compared to control. Moreover, mutating them in combination with other transmembrane cysteine to serine residues reduces Qsp even further (blue). Separate back mutation, either S192C or S196C (red), recovers Qsp, suggesting that C192 and C196 are able to compensate for each other. For instance, C192S–C196S/C395S and C192S–C196S/C415S (blue) fully abolish NLC. Nevertheless, C395S (or C415S) in combination with either C192S or C196S alone (red) partially recovers Qsp. Similar patterns were found in C260S combined with C192S and/or C196S, and C381S combined with C192S and/or C196S, although C192S–C196S/C260S and C192S–C196S/C381S decrease (but do not abolish) Qsp. Reduction of Qsp in these C192S–C196S mutants were statistically significantly different from wild-type prestin (#p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01). Similarly, recovery of Qsp with back mutation of either S192C or S196C alone was also statistically significant (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01). n is number of cells that evidenced NLC and were used for statistics; parentheses enclose the total number of cells recorded. (B) Representative NLC traces from wild-type prestin and mutants.

Cysteine 415 likely forms a disulfide bond

The only single cysteine mutation that resulted in a significant reduction in Qsp was C415S. In this regard, C415S was similar to the single mutation equivalent of C192S–C196S, and suggested that C415 should be as influential as the C192–C196 pair. As suspected, mutation of C415S in combination with another cysteine residue posited to lie within the transmembrane segments also resulted in a loss or near loss of NLC. These include C192S–C196S/C415S, C260S/C415S, C381S/C415S (abolished NLC), and C395S/C415S (greatly reduced NLC). One possibility was that C415 formed a disulfide bond that was critical in maintaining tertiary structure of the protein important for generating NLC. Alternatively, because disulfide bonded cysteine residues are sterically constrained by the bond, in contrast to the side chain of an unbonded serine residue, we hypothesized that changes in NLC were because the more freely mobile serine residue interfered with prestin function. To test this possibility we mutated C415 to alanine, which has a shorter side chain and would be predicted to minimally disrupt secondary structure, and tested NLC of this mutant. Additionally, C415A was mutated in combination with each of the following substitutions: C192S–C196S, C260S, C381S, and C395S. The C415A mutant alone or in combination with the other cysteine mutations resulted in significant NLC (Fig. 5). Taken together these data argue that C415 forms a disulfide bond.

Figure 5.

C415S plays a key role in generating NLC. (A) Qsp values of C415S related mutants are shown. C415S (blue) alone markedly decreases Qsp. In addition, C415S in combination with other transmembrane cysteine mutants reduces Qsp even further. In contrast, the back mutation C415A alone or in combination with other cysteine mutants evidenced recovery of Qsp (red). Thus, C192S–C196S/C415S, C260S/C415S, and C381S/C415S completely eliminate NLC, and C395S/C415S markedly reduced NLC. In contrast, C192S–C196S/C415A, C260S/C415A, C381S/C415A, and C395S/C415A all showed significantly improved or recovered Qsp. Residue side chain length and spatial constraint may underlie these differences (see text for details). Qsp in C415S mutants was statistically significantly different from wild-type prestin (#p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01). Similarly, recovery of Qsp with back mutation of S415A was statistically significant (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01). n is number of cells that evidenced NLC and were used for statistics; parentheses enclose the total number of cells recorded. (B) Representative NLC traces from wild-type prestin and mutants.

Substitution of all nine cysteine residues did not hinder dimerization of the protein

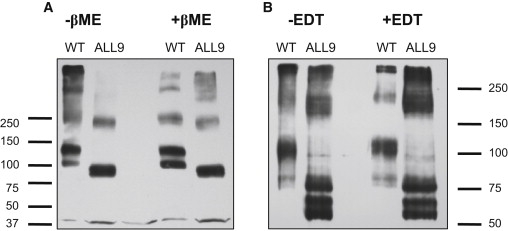

Our data suggest that cysteine residues are important for the generation of NLC. In addition, there is compelling indirect evidence that cysteine residues in prestin form disulfide bonds. Given the importance of multimerization in prestin function (7), we then sought to determine if any of these cysteine residues were important in multimerization of the protein. Work by Zheng et al. (25) showed that the addition of the hydrophobic reducing agent EDT resulted in a reduction in the amount of dimeric prestin relative to its monomeric form. Data hitherto mutating several cysteine residues in combination had no effect on dimerization (Fig. 3). We also assayed dimerization in prestin-YFP in which all nine cysteine residues were mutated to serine (ALL9). Cell lysates from this mutant and from wt-prestin-YFP were separated by SDS-PAGE. Prestin was detected by Western blotting using an antibody to its N terminus (Fig. 6). Two features of the mutant were evident. First, dimers of prestin were evident in both wt-prestin as well as prestin in which all nine cysteine residues were mutated. Second, removal of all nine cysteine residues resulted in a notable apparent reduction in molecular weight of prestin monomers (and dimers). Because disulfide bonds were not necessary for prestin dimerization we then separated the protein using Urea-SDS gels, attempting to disrupt potential hydrophobic interactions between monomers of the protein. As is evident in Fig. 6 this approach also failed to disrupt dimer formation. Unexpectedly, monomers of prestin were seen to separate into several closely interspersed discrete bands. These bands were detected on Western blots using antibodies to the N-terminus of prestin, and after stripping and reprobing with antibodies to YFP (because YFP was fused to the C-terminus of prestin), suggesting that the smaller forms of prestin were not due to significant proteolytic cleavage (data not shown). Finally, we note that higher multimers of prestin are likely not detected because we did not boil our preparations before running gels.

Figure 6.

Prestin dimerization does not require cysteine residues. Cell lysates of CHO cells transiently transfected with prestin-YFP or prestin-YFP where all nine cysteine residues were mutated to serine (ALL9) were separated by SDS-PAGE and prestin was detected by Western blotting using an antibody to its N-terminus. The position of molecular weight markers is shown. (A) The absence of all nine cysteine residues does not influence the formation of prestin dimers (∼250 kD) in lysates separated by standard SDS-PAGE in the presence or absence of 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Prestin monomers and dimers were apparently smaller in the ALL9 cysteine mutants. (B) Separation on SDS-PAGE gels containing 6 M urea before Western blotting did not alter the identification of dimers. Prestin dimers in both wild-type prestin and ALL9 mutants were still detectable in the presence of 6 M urea (and 600 mM EDT), signifying that the formation of dimers did not require disulfide bonds and resulted from strong hydrophobic bonds. Moreover, the smaller prestin monomers and dimers in the ALL9 mutant were resolved into several discrete bands. These bands were also detected after stripping and reprobing the blots with antibodies to tagged YFP (data not shown) indicating that altered folding rather than proteolytic cleavage was responsible for the observed difference in molecular weight between prestin and the ALL9 mutant.

Discussion

Prestin is a protein that underlies cochlea amplification, in turn responsible for the high sensitivity of mammalian hearing (2,4). It is an anion transporter (SLC26a5) that is voltage-dependent, as well (14). Intrinsic charged residues are displaced during membrane voltage perturbations to effect conformational changes that drive a robust somatic motility that provides a boost in signal to the sensory inner hair cells within the cochlea (16,31). We showed previously that monomer interactions determined by FRET were required for normal voltage sensing, because very short truncations of the N-terminus, but not the C-terminus, abolished FRET and NLC, the electrical signature of OHC electromotility (7). Additionally, sulfhydryl reagents have been shown to significantly alter NLC and mechanical activity in native OHCs (21,22). These data raised the possibility that voltage sensing and multimerization in prestin require disulfide bond formation.

Combinatorial cysteine substitutions reveal critical residues for voltage sensing and are likely involved in disulfide bond formation

We have attempted to discern the role of cysteine residues in prestin by mutating these residues both individually and in combination, and then determining their effects on NLC. Earlier work had shown that individual mutations only slightly affected measures of NLC, in line with our results. However, Zheng et al. (25) raised the possibility that disulfide bonds between cysteine residues in the transmembrane domains were important for oligomer formation. Disulfide bond prediction programs, which use a host of algorithms, largely predict an absence of cysteine bonding (A. Surguchev and D. S. Navaratnam, unpublished observation). However, two caveats apply to these programs; they are based largely on soluble proteins, and a number of them rely on empirically established cysteine residue interactions in homologous proteins (17). Thus, the use of these algorithms for prestin analysis is limited, because six of the nine cysteine residues reside in predicted hydrophobic transmembrane regions. Moreover, there is scarce literature on cysteine residue interactions in prestin homologs.

Our data provide indirect evidence that residues C415 and either C192 or C196 are involved in disulfide bond formation. Our reasoning for imputing the formation of disulfide bonds for each differs. In the case of C192–C196, the formation of disulfide bonds by one of these residues is indicated by the two residues being able to substitute for one another. In the case of C415, bond formation is indicated based on the ability of alanine substitution to rescue effects produced by C415S. We hypothesize that that the unconstrained side chain of the serine residue interferes with prestin function. In contrast, the naturally occurring cysteine residue, with an identical side chain length, is disulfide bonded and therefore sterically constrained. We reason that this sterically constrained side chain is unable to interfere with NLC. Similarly, we reason that the shortened side chain in C415A is incapable of interfering with prestin function.

It might be argued that differences in hydrophobicity of alanine, cysteine, and serine, rather than disulfide bond formation promote NLC generation. However, it is not clear that hydrophobicity differences between cysteine and the two substitutes are significant. In fact, the differences between the hydrophobicity of serine, cysteine, and alanine are small (32). Of the >30 tabulations of hydrophobicity the placement of these residues by relative hydrophobicity are interchangeable. In part, this is because cysteine residues form disulfide bonds and are prone to lie on the internal surface of the protein. Some tabulations use position of the residue on 3D structure as a measure of hydrophobicity. However, others that use only the physical/chemical properties of the amino acid find it to be less hydrophobic. Furthermore, the relevance of an amino acid's hydrophobicity to structure is questionable (33). To reiterate, we suggest that disulfide bond formation constrains C415 and allows for NLC generation.

An obvious pairing would be for C415 to form a disulfide bond with C192 or C196. However, individual mutations of these residues do not produce mirror effects on measures of NLC (Vh, Qsp, and z), as might be expected. The reason for this could be due to C192 substituting for C196, with mutation of both residues (C192 and C196) producing additional effects on measures of NLC. Should there be formation of disulfide bonds between C415 and C192 or C196, we would anticipate a physical approximation of the two residues, a feature not especially obvious in the current transmembrane models of the protein. Other data indicate that a disulfide bond between C415 and C192 (or C196) is unlikely. For instance, Qsp was significantly decreased when C415S (or C192S–C196S) was combined with other transmembrane cysteine residues, but not when combined with nontransmembrane cysteine residues (C52S, C124S, and C679S). Thus, given that intra membranous disulfide bonds are formed in these cases, the occurrence of a bond between C415 and C192 or C196 is unfeasible.

Evolutionarily new cysteine residues are among those residues critical for NLC generation

Of the nine cysteine residues four, C52, C381, C395, and C679, are conserved between nonmammalian vertebrates and eutherian mammals (34). In contrast, cysteines in positions 124, 192, 196, 260, and 415 are not conserved. Cysteine residues could be important for determining electromotility, a feature of mammalian prestin but not its nonmammalian counterparts (35,36). It could be reasoned that these nonconserved, and evolutionarily newly acquired, cysteine residues would be more important than cysteine residues that are conserved between prestin from mammals and nonmammalian vertebrates. It is interesting that both C415 and C192–C196 are not found in prestin from nonmammalian vertebrates, reinforcing the view that these newly acquired cysteine residues are important for the structural features in prestin responsible for generating characteristics of gating charge movement that underlie electromotility. The data suggesting that these residues are involved in disulfide bond formation lead us to predict that these disulfide bonds are structural (instead of allosteric or catalytic disulfide bonds). The increased amounts of misfolded protein on the surface of the cell where these cysteines have been modified corroborate this prediction. It should be noted that the removal of cysteines does not predicate misfolding of the protein but rather increases the probability of misfolding suggested by a fraction of wt-prestin that is also misfolded (albeit to a smaller degree).

Alterations in Qsp produced by different cysteine mutants is due to subtle alteration in folding and not due to reduced surface expression

The effects of cysteine mutations on prestin could be due to inadequate surface expression, changes in tertiary/quaternary structure or a combination of the two. There was no relationship between transfection and expression efficiencies of the different mutants and its effects on Qsp. Both the expression of YFP tagged protein in the cell determined by fluorescent activated cell sorting and the total expression of prestin on the surface of the cell determined by surface biotinylation had no relationship to Qsp, the electrophysiological measure of functional prestin on the surface of the cell. Rather, a linear correlation between the ratio of the upper monomer to lower monomer and Qsp suggests that the cell expresses a functional monomer and that Qsp is a measure of this functional monomer. Why does the ratio of upper to lower monomer band correlate with Qsp? We reason that the misfolded lower band interferes with prestin function, in a dominant negative manner, possibly during dimerization of the two forms. In this way, the absolute amount of upper band monomer may not necessarily correlate with prestin function.

Although it is known that SLC26A3 can be cleaved at its N-terminus to produce two bands detectable with C-terminal antibodies on Western blotting (17), we conclude that the observed differences in prestin monomers are due to changes in folding because the two monomers are detected with antibodies to both the N- and C-terminus of prestin. An alternate possibility that the lower molecular form represents a nonglycosylated protein is unlikely. For one, both forms of the protein would have been exposed to the glycosylation machinery before insertion into the plasma membrane. For another, prior experiments have shown absent glycosylation of prestin in CHO cells (7). Moreover, removal of glycosylation results in a functional protein. Importantly, these data question the use of prestin surface expression determined by fluorescence as a measure of adequate surface delivery, as has been done by many groups including ours. Our data suggest an alternative and more accurate test—adequate surface delivery of properly folded protein. Conversely, we believe the data in this study substantiate the idea that Qsp, in the absence of significant changes in z, to be a good measure of functional protein on the surface of the cell.

Dimer formation is a result of strong van der Waals forces and does not require disulfide bonds

Previous experiments by Zheng et al. (25) suggested that disulfide bonds were important in the formation of prestin dimers. However, the formation of prestin dimers in the absence of all nine cysteine residues leads us to conclude that disulfide bonds are not essential for the formation of prestin dimers, in line with another recent study (29). The presence of prestin dimers in multiple cysteine mutations involving different cysteine residues further validates our reasoning. We think it unlikely the alternative explanation that mutation of all nine cysteines resulted in a misfolding of the protein that then led to dimerization of this misfolded protein through interactions of novel exposed hydrophobic surfaces. On the other hand, although not essential for dimer formation, we are unable to confirm if disulfide bonds contribute to prestin dimer maintenance. For instance, disulfide bonds stabilize dimers in the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, but are not required for their formation (37). In any case, the presence of dimers in 6 M urea in mutants lacking all nine cysteine residues implies very strong hydrophobic interactions between prestin monomers. In the absence of evidence showing intermolecular disulfide bond formation in prestin, we posit that cysteine residues are constrained by intramolecular disulfide bonds that are important for normal voltage sensing and mechanical activity in prestin.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (DC007894 to D.S.N., DC00273 to J.S.S., and DC0008130 to D.S.N. and J.S.S.).

References

- 1.Zheng J., Madison L.D., Dallos P. Prestin, the motor protein of outer hair cells. Audiol. Neurootol. 2002;7:9–12. doi: 10.1159/000046855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dallos P., Wu X., Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liberman M.C., Gao J., Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos-Sacchi J., Song L., Nuttall A.L. Control of mammalian cochlear amplification by chloride anions. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3992–3998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4548-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brownell W.E., Bader C.R., de Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng J., Long K.B., Dallos P. Prestin topology: localization of protein epitopes in relation to the plasma membrane. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1929–1935. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107030-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navaratnam D., Bai J.P., Santos-Sacchi J. N-terminal-mediated homomultimerization of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Biophys. J. 2005;89:3345–3352. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deak L., Zheng J., Dallos P. Effects of cyclic nucleotides on the function of prestin. J. Physiol. 2005;563:483–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig J., Oliver D., Fakler B. Reciprocal electromechanical properties of rat prestin: The motor molecule from rat outer hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:4178–4183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071613498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gale J.E., Ashmore J.F. Charge displacement induced by rapid stretch in the basolateral membrane of the guinea-pig outer hair cell. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1994;255:243–249. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakehata S., Santos-Sacchi J. Membrane tension directly shifts voltage dependence of outer hair cell motility and associated gating charge. Biophys. J. 1995;68:2190–2197. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80401-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwasa K.H. A two-state piezoelectric model for outer hair cell motility. Biophys. J. 2001;81:2495–2506. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75895-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasa K.H. Effect of stress on the membrane capacitance of the auditory outer hair cell. Biophys. J. 1993;65:492–498. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81053-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai J.P., Surguchev A., Navaratnam D. Prestin's anion transport and voltage-sensing capabilities are independent. Biophys. J. 2009;96:3179–3186. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashmore J.F. Transducer motor coupling in cochlear outer hair cells. In: Kemp D., Wilson J.P., editors. Mechanics of Hearing. Plenum Press; New York: 1989. pp. 107–113. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santos-Sacchi J. Reversible inhibition of voltage-dependent outer hair cell motility and capacitance. J. Neurosci. 1991;11:3096–3110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-10-03096.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh R. A review of algorithmic techniques for disulfide-bond determination. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic. 2008;7:157–172. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/eln008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wedemeyer W.J., Welker E., Scheraga H.A. Disulfide bonds and protein folding. Biochemistry. 2000;39:4207–4216. doi: 10.1021/bi992922o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogg P.J. Disulfide bonds as switches for protein function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:210–214. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorn M., Weiwad M., Bosse-Doenecke E. Identification of a disulfide bridge essential for transport function of the human proton-coupled amino acid transporter hPAT1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:22123–22132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos-Sacchi J., Wu M. Protein- and lipid-reactive agents alter outer hair cell lateral membrane motor charge movement. J. Membr. Biol. 2004;200:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s00232-004-0699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalinec F., Kachar B. Inhibition of outer hair cell electromotility by sulfhydryl specific reagents. Neurosci. Lett. 1993;157:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McGuire, R., F. Pereira, and R. M. Raphael. 2008. Effects of cysteine mutations on prestin function and oligomerization. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. Abs. 675.

- 24.McGuire, R., F. Pereira, and R. M. Raphael. 2007. Modulation of prestin function due to cysteine point mutations. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. Abs. 1039.

- 25.Zheng J., Du G.G., Cheatham M. Analysis of the oligomeric structure of the motor protein prestin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:19916–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santos-Sacchi J. Determination of cell capacitance using the exact empirical solution of dY/dCm and its phase angle. Biophys. J. 2004;87:714–727. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.033993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Santos-Sacchi J., Kakehata S., Takahashi S. Effects of membrane potential on the voltage dependence of motility-related charge in outer hair cells of the guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 1998;510:225–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.225bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mio K., Kubo Y., Sato C. The motor protein prestin is a bullet-shaped molecule with inner cavities. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:1137–1145. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702681200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Detro-Dassen S., Schanzler M., Fahlke C. Conserved dimeric subunit stoichiometry of SLC26 multifunctional anion exchangers. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:4177–4188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reference deleted in proof.

- 31.Ashmore J.F. Forward and reverse transduction in the mammalian cochlea. Neurosci. Res. Suppl. 1990;12:S39–S50. doi: 10.1016/0921-8696(90)90007-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfenden R., Andersson L., Southgate C.C. Affinities of amino acid side chains for solvent water. Biochemistry. 1981;20:849–855. doi: 10.1021/bi00507a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charton M., Charton B.I. The structural dependence of amino acid hydrophobicity parameters. J. Theor. Biol. 1982;99:629–644. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okoruwa O.E., Weston M.D., Beisel K.W. Evolutionary insights into the unique electromotility motor of mammalian outer hair cells. Evol. Dev. 2008;10:300–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00239.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He D.Z., Beisel K.W., Salvi R. Chick hair cells do not exhibit voltage-dependent somatic motility. J. Physiol. 2003;546:511–520. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albert J.T., Winter H., Oliver D. Voltage-sensitive prestin orthologue expressed in zebrafish hair cells. J. Physiol. 2007;580:451–461. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.127993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bon S., Coussen F., Massoulie J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:3016–3021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]