Abstract

Background

The Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC) is an NIH funded prospective cohort study of natural history and treatment efficacy in individuals with recently acquired hepatitis C. Enrolment is open to both HIV positive and HIV negative individuals. The aim of this paper was to evaluate characteristics and virological outcomes within HIV positive individuals enrolled in ATAHC

Methods

Eligibility criteria include first anti-HCV antibody positive within 6 months and either clinical hepatitis C within the past 12 months or documented anti-HCV seroconversion within the past 24 months.

Results

Of the initial 103 subjects enrolled 27 (26%) were HIV positive. HIV positive subjects were more likely to be older, have genotype 1 infection and high HCV RNA at baseline than HCV monoinfected subjects. Sexual acquisition accounted for the majority (56%) of HCV infections in HIV positive subjects compared to only 8% of HCV monoinfected subjects. Median duration from estimated HCV infection to treatment was 30 weeks. Treatment with 24 weeks of Pegylated interferon and ribavirin resulted in rates of HCV RNA undetectability of 95%, 90% and 80% at weeks 12, 24 and 48 respectively. Week 4 undetectability was achieved in 44% of subjects and gave positive and negative predictive values for SVR of 100% and 33% respectively.

Conclusions

Significant differences are demonstrated between HIV positive and HIV negative individuals enrolled into ATAHC. Treatment responses in HIV positive individuals with both acute and early chronic infection are encouraging and support regular HCV screening of high risk individuals and early treatment for recently acquired HCV infection.

Introduction

Acute hepatitis C (AHC) occurring in HIV positive men who have sex with men (MSM) has been recognised as an important issue in recent years. Reports of rising numbers of new AHC diagnoses in HIV positive populations were described simultaneously in the early 2000s from major European cities including London, Paris and Amsterdam [1-4] [5]. Notably, these outbreaks of hepatitis C were predominantly associated with sexual or ‘permucosal’ transmission, as opposed to traditional routes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) exposure through injecting drug use (IDU) [6].

Rising rates of acquisition of HCV amongst HIV positive MSM is of particular concern given the accelerated course of HCV-related liver disease in this population [7], and the poor response rates to therapy with Pegylated interferon (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin in chronically infected HIV/HCV subjects [8, 9] Outcomes following treatment of AHC in HIV infected individuals have been described by a number of groups, often retrospectively, and are summarised in Table 1. The largest prospective treatment report involving 36 individuals used a variety of treatment regimens and found an overall SVR of 61% [10]. The SVR rate in these studies is generally lower than that observed in HCV monoinfected individuals with AHC [11-14].

Table 1.

Studies of AHC treatment outcomes in HIV positive individuals

| Author/year | Location | Study type | Number treated (total cases) | Regimen | BL CD4 (cells/mm3) | Median Duration to diagnosis | Duration to treatment from diagnosis | GT | SVR* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serpaggi 2006 [5] | France | R | 10 (12) | 7 IFN 2 IFN/RBV 1 PEG |

625 | 4 months (1.5-7m) | 49 days from illness | 4 (83%) 1 (8%) |

0/10 (0%) |

| Luetkemeyer 2006 [26] | USA | R | 4 (9) | PEG/RBV 48 w (24w in 1) |

402 | 8 w | 6 w | 1 (75%) | 2/3 (66%) |

| Vogel 2006 [10] | Germany | P | 36 (47) | PEG in GT 2/3 (15) PEG/RBV in GT 1 (21) (24w in 12, 48w in 9) |

587 | 55% < 4w Max 16weeks |

7 w | 1 (64%) 4 (27%) |

61% |

| Vogel 2005 [15] | Germany | R | 11 (13) | 2 IFN 4 PEG 5 PEG/RBV |

507 | 14.4w | 2.6 w | 1 (73%) 4 (18%) |

10/11 (91%) # |

| Dominguez 2006 [27] | France | P | 14 (25) | PEG/RBV 24w | 345 | n/a | 14 w | 1 (29%) 4 (33%) 3 (36%) |

71% |

| Gilleece 2005 [26, 28] | UK | R/P | 27 (50) | PEG/RBV 24w | N/a | n/a | n/a | 1 (86%) | 59% |

R: retrospective; P: prospective; BL: baseline; IFN: Intereferon; PEG: Pegylated interferon; RBV: ribavirin

RVR not reported in any study

9/11 patients were symptomatic and no wait period was observed therefore rate of spontaneous clearance may have been higher

Many studies of AHC treatment have focused on cases identified through either acute hepatitis clinical presentation or recently reported exposure episodes [11, 12, 15]. However, a large number of recently acquired HCV cases are identified through anti-HCV antibody seroconversion among individuals with regular testing, particularly in the setting of predominantly IDU acquired infections [16]; such cases maybe more correctly defined as having early chronic HCV when the estimated duration of infection extends beyond 24 weeks. The efficacy of HCV treatment in early chronic HCV has not been evaluated, either in HCV monoinfection or HIV/HCV coinfection.

The Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC) study is an NIH funded prospective cohort study established to examine the natural history and treatment safety and efficacy in individuals with recently acquired HCV infection, predominantly acquired through IDU. In this paper we report on the HIV/HCV subjects enrolled into the study and examine the HCV virological outcomes among the initial HIV/HCV coinfected subjects commenced on therapy.

Subjects and Methods

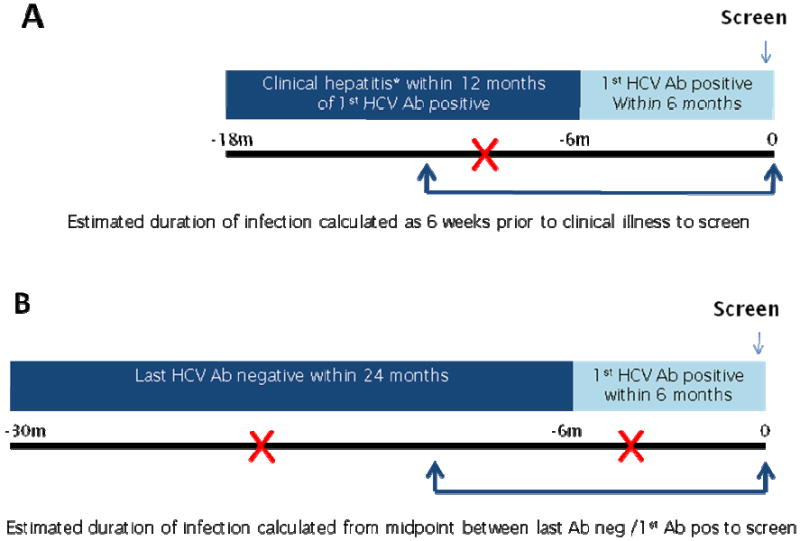

ATAHC is a multicenter, prospective study longitudinal cohort study of subjects with recently acquired HCV. Study subjects were recruited through a variety of mechanisms including direct recruitment from primary and tertiary care sites. Subjects were also recruited through new HCV case notifications via enhanced surveillance systems operating in the major Australian states. Recently acquired HCV infections are defined in these systems as the detection of HCV antibody from a person who has had a negative HCV antibody test recorded within the past 24 months, or the first detection of anti-hepatitis C antibody, and clinical hepatitis within the past 12 months. Eligibility criteria for ATAHC were devised to be consistent with these definitions and therefore the study could include subjects with both acute HCV infection (estimated duration of infection less than 6 months) and early chronic HCV infection (estimated duration of infection between 6 and 18 months) (Figure 1). Study recruitment commenced in June 2004 and enrolment was open to both HIV negative and HIV positive individuals. Inclusion criteria for the study were recently acquired HCV infection as defined by a first positive anti-HCV antibody within 6 months of enrollment and either i) acute clinical HCV (jaundice or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level more than 10 times the upper limit of normal) with exclusion of other causes of acute hepatitis within 12 months prior to the initial positive anti-HCV antibody or ii) a negative anti-HCV antibody in the 24 months prior to the initial positive anti-HCV antibody. Subjects were required to be HCV antibody positive at screen, and all subjects with detectable HCV RNA were assessed for HCV treatment eligibility. Exclusion criteria for the treatment arm included investigational drugs within previous 6 weeks, positive serology for anti-HAV IgM, HBsAg, or anti-HBc IgM, other causes of liver disease, and other standard laboratory-based exclusion criteria for interferon therapy. Heavy alcohol intake or active illicit drug use were not exclusion criterion, however, drug and alcohol assessment was performed to assess treatment suitability. Clinicians were advised to defer treatment for at least 12 weeks from acute HCV diagnosis to allow for potential spontaneous HCV clearance.

Figure 1. Potential mechanisms for entry into study through (A) clinical hepatitis definition or (B) antibody seroconversion definition.

*Acute clinical hepatitis defined as jaundice or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level more than 10 times the upper limit of normal with exclusion of other causes of acute hepatitis Where  represents examples of clinical hepatitis in scenario A and antibody negative/antibody positive in scenario B

represents examples of clinical hepatitis in scenario A and antibody negative/antibody positive in scenario B

Study treatment and virological assessment

Treated HCV monoinfected subjects received pegylated interferon-α2a (PEG-IFN) 180 micrograms weekly for 24 weeks. In view of concerns regarding the efficacy of monotherapy in HIV positive individuals, and after the first two HIV/HCV coinfected subjects treated with PEG-IFN monotherapy failed to respond, the study protocol was amended to mandate PEG-IFN and ribavirin combination therapy for 24 weeks for all HIV/HCV coinfected subjects. HCV RNA assessment was performed at all scheduled study visits (screening, baseline, week 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 12 weekly through week 144); initially with a qualitative HCV-RNA assay (TMA assay, Versant, Bayer, Australia, lower limit of detection 50 copies/ml [approximately 10 IU/ml]) and if positive repeated on a quantitative HCV RNA assay (Versant HCV RNA 3.0 Bayer, Australia lower limit of detection 3200 copies/ml). HCV genotype (Versant LiPa2, Bayer, Australia) was performed on all subjects at screening. Risk behavior, including injecting behaviour was assessed at screening, and every 12 weeks through follow-up. Additionally at screening the investigator was specifically requested to identify the most likely mode of HCV acquisition based on the subjects’ clinical history and risk exposure.

Statistical methods and study definitions

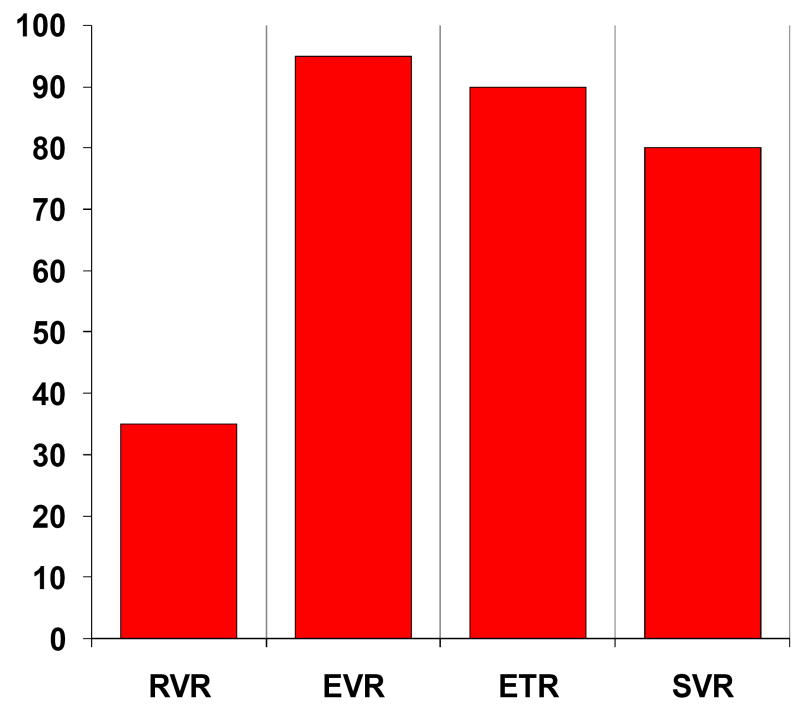

Evaluation of HCV treatment response was based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses among all HIV/HCV coinfected subjects enrolled between June 2004 and June 2006 and commenced on combination therapy with PEG-IFN/RBV. The primary endpoint was HCV RNA clearance as defined by a negative qualitative HCV RNA assessment at least 24 weeks post-treatment (sustained virological response, SVR).Other HCV treatment outcomes included undetectable HCV RNA rates at week 4 (rapid virological response, RVR), week 12 (early virological response, EVR), and week 24 (end-of-treatment response, ETR). Secondary study endpoints included alanine aminotransferase (ALT) change from baseline to week 24 and 48, and changes in haemoglobin, neutrophil, platelet count, CD4 count and HIV RNA from baseline to week 24.

The following definitions were set prior to study commencement. Duration of HCV infection was defined as the time from estimated date of HCV infection to screening. Estimated time of HCV infection was calculated for acute clinical HCV cases as 6 weeks prior to onset of symptoms or peak ALT > 400 IU/l (whichever occurred first). In asymptomatic HCV cases estimated time of HCV infection was calculated as the mid-point between last negative anti-HCV antibody and first positive anti-HCV antibody (Figure 1). Individuals with an estimated duration of infection of less than 6 months were characterised as having ‘acute’ HCV whereas individuals with an estimated duration of infection between 6 and 18 months were characterised as having ‘early chronic’ infection.

All study subjects provided written informed consent prior to any study procedures. The study protocol was approved by St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney Ethics Committee (primary study committee) as well as through local ethics committees at all study sites, and was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and ICH/GCP guidelines.

Results

Baseline characteristics

One hundred and three subjects were enrolled into the study overall between June 2004 and June 2006 and of these 27 (26%) were HIV infected. Baseline characteristics of the HIV negative and HIV positive subjects are given in Table 2. Notable differences existed between the HIV positive and HIV negative groups. All HIV positive subjects were male as compared to 62% of HIV negative subjects. HIV positive subjects were more likely to be older (40 vs 30 years), have genotype 1 (60% vs 42%) and higher HCV viral load at baseline (median 65,187 IU/ml vs 30,769 IU/ml). Clinical presentation of acute HCV was remarkably similar between HIV positive and HIV negative subjects with around half (46- 48%) experiencing an acute HCV illness and a similar maximum mean ALT level (981 vs 937 IU/ml). 25 HIV positive subjects had documented HCV antibody seroconversion. The mean duration of infection prior to screening was shorter in the HIV positive group (22 weeks vs 39 weeks). In the HIV positive subjects mean baseline CD4 was 614 cells/mm3 and 59% were on HAART.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of HIV positive and HIV negative subjects enrolled into ATAHC between June 2004 and June 2006

| HIV positive ( n=27) | HIV negative (n=76) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demorgraphics | ||

| Age- mean (years) | 40 | 30 |

| Gender - male | 100% | 62% |

| Ethnicity - Caucasian | 96% | 89% |

| Genotype | ||

| 1 | 60% | 42% |

| 2/3 | 33% | 41% |

| missing | 7% | 17% |

| Transmission riska | ||

| IDU | 44% | 81% |

| Same Sex partner- known HCV status | 19% | 0% |

| Same sex partner- unknown HCV status | 30% | 1% |

| Opposite sex partner- known HCV status | 0% | 7% |

| Other/unknown | 7% | 11% |

| IDU everb | 67% | 80% |

| Injecting behaviour | ||

| Age at first injecting (yrs) | 31 | 22 |

| Drug most frequently injected | Methamphetamine (58%) | Heroin (55%) |

| HCV related parameters | ||

| Acute clinical illness | 48% | 46% |

| Maximum ALT (mean, IU/ml) | 981 | 937 |

| Baseline ALT (mean, IU/ml) | 194 | 160 |

| Estimated duration infectionc (mean, weeks) | 22 weeks | 39 weeks |

| Baseline HCV RNA (median, IU/ml) | 65,187 | 30,769 |

| HIV related parameters | ||

| Baseline CD4 (mean, cells/mm3) | 614 | N/A |

| Nadir CD4 (mean, cells/mm3) | 323 | N/A |

| CDC class 1 | 93% | N/A |

| % on HAART | 59% | N/A |

| % uptake HCV treatment | 81% | 66% |

Transmission risk: Most likely mode of HCV acquisition as identified by investigator after review of subjects risk behaviour and clinical history

By self report in drug and alcohol questionnaire as having ever injected.

at screening

There were significant differences in the risk factors for HCV transmission between HIV negative and HIV positive groups. IDU was identified as the most likely source of infection in 81% of HCV monoinfected subjects compared to 44% of HIV positive subjects. In contrast, sexual transmission was the most likely source of infection in 56% of the HIV group (of whom 38% were with a known HCV positive sex partner and 62% with partner(s) of unknown status) and only 8% of the HCV monoinfected group. Even in the HIV positive group with IDU as a risk factor for HCV transmission, patterns of drug use were different from those within the HIV negative group. The average age at first injection was older (31 years vs 22 years) and the most frequent drug injected was methamphetamine (58%) or amphetamine (42%) as opposed to heroin (55% of HCV monoinfected cases)

Treatment uptake

Of 27 HIV positive subjects enrolled, 22 (81%) commenced HCV treatment. Of the 5 untreated subjects, one had a diagnosis of malignant melanoma and died from this disease 6 months following enrolment and the remaining 4 had low screening HCV RNA (10-615 IU/ml in 2 cases, <3,000 IU/ml in 2 cases). Two of these cases subsequently cleared, one progressed to chronic HCV infection and the fourth was lost to follow-up at week 12 with detectable HCV RNA at that time point.

Treatment response

The first two subjects were treated with Pegylated interferon monotherapy within the same protocol as HCV monoinfected subjects. Both of these subjects had genotype 1a infection and high HCV RNA at baseline. Neither achieved > 1 log reduction in HCV RNA at week 4 and both remained HCV RNA positive at week 12. Treatment was ceased and in one subject recommenced some months later with combination therapy, again unsuccessfully. Subsequent to these results the treatment protocol for HIV positive individuals was amended to 24 weeks PEG-IFN/ribavirin (PEG/RBV) combination for all subjects as initial therapy. Twenty HIV coinfected subjects have been treated with PEG/RBV therapy and reached the 48 week SVR timepoint.

Treatment responses are given in Figure 2 with 95%, 90% and 80% of subjects HCV RNA undetectable (<10 IU/ml) by ITT analysis at EVR, ETR and SVR, respectively. One subject was lost to further follow-up at week 36 having achieved RVR with HCV RNA <10 IU/ml at all timepoints prior to week 36. It is highly likely therefore that this subject would have achieved SVR giving an overall SVR of 85%. Of the three subjects treated with PEG/RBV with virological non-response (HCV RNA detectable at week 48) one failed to achieve EVR and withdrew from treatment at 12 weeks. Heavy alcohol intake was a significant factor in this case. The second subject achieved an initial reduction in HCV RNA to < 615 IU/ml at week 4 but remained positive on qualitative testing. HCV RNA rose thereafter to 3589 IU/ml by week 24. The third subject relapsed after treatment completion with an HCV RNA of 61,581 IU/ml at week 48 having been HCV RNA negative at end of therapy. Viral sequencing supported viral breakthrough and viral relapse in the second and third subjects, respectively, rather than reinfection. By ITT, SVR was achieved in 100% (9/9) of non-1 genotypes and in 64% (7/11) of genotype 1 subjects. All three non-SVR cases had genotype 1a infection.

Figure 2. Treatment response rates in HIV positive subjects treated with PEG/RBV within ATAHC by ITT analysis.

RVR: Rapid virological response

EVR: Early virological response

ETR: Early treatment response

SVR: Sustained virological response

Additionally, SVR did not appear to be reduced in those with a longer period of estimated infection and was observed in 77% of those with an estimated duration less than 24 weeks and 86% of those with an estimated duration of infection greater than 24 weeks.

Rapid and early virological response rates

Week 4 HCV RNA qualitative data was available for 16 (80%) subjects. In this group the rapid virological response rate (RVR) was 44% (35% by ITT if non-available results are included). Although the numbers are small, genotype appeared to have little impact on RVR, with 50% RVR in genotype 1 subjects and 30% RVR in genotype non-1 subjects. All 7 subjects with RVR subsequently achieved SVR, giving a positive predictive value for RVR in this analysis of 100%. SVR was achieved in 6 of 9 subjects without an RVR (negative predictive value 33%).

Safety and tolerability

Therapy was generally well tolerated with a median drop of 2.1 g/dl in Hb by week 24. Four subjects experienced serious adverse events - in one subject severe depression developed requiring hospitalisation. Only 1 subject required a dose modification for neutropaenia and 80% of subjects received more than 80% of injections. Median CD4 count declined by 237 cells/mm3 at week 24 to 393 cells/mm3 (range 189 - 689 cells/mm3), but by week 48 had rebounded to a median 515 cells/mm3. HIV RNA remained suppressed in all patients on HAART and declined by a median of 0.7 log10 copies/ml in those not on HAART. All three HCV virological failures were observed in subjects on HAART with HIV RNA < 50 copies/ml.

Discussion

This analysis of HCV treatment outcomes within HIV HCV coinfected subjects within this study highlights and expands on several important areas of research in this field. Firstly, baseline characterisation of these individuals demonstrates that, compared to HCV monoinfected subjects recruited to the study contemporaneously, HIV positive subjects with recently acquired HCV infection represent a significantly different group of individuals. HIV-HCV coinfected subjects were older, more often infected with HCV genotype 1, and considerably more often infected through sexual transmission. Differences were also seen in patterns of drug use in those that did inject. Despite these differences, AHC presents with a similar clinical picture in HIV negative and positive subjects. The shorter duration between estimated time of infection and screening seen in the HIV positive group may reflect heightened awareness of the current acute HCV epidemic specifically within the HIV treatment community.

The recognition of sexual exposure as an important possible route of HCV transmission within the HIV population has been widely reported in recent years, accompanied by a rapid increase in the number of AHC cases diagnosed in HIV positive individuals from across Europe [1, 3, 4, 10]. Our study is the first to simultaneously enrol HCV monoinfected individuals, using the same sites and protocol, to demonstrate that not only is the occurrence of sexually transmitted AHC also occurring within the HIV population in Australia, but that this group of subjects has distinctly different characteristics from HCV monoinfected individuals acquiring AHC within the same time frame. A case control study from the UK involving 111 HIV positive MSM with AHC identified a number of high-risk sexual behaviours potentially associated with acquisition of infection [17], but further exploration of the mechanisms of permucosal transmission is still required. Phylogenetic analysis of subjects within the UK case study identified at least seven HCV transmission clusters supporting the role of permucosal transmission within HIV positive networks. Phylogenetic analysis from subjects recruited within ATAHC, both from within injecting and sexual networks, will help examine the extent of clustering and importantly any interaction between HIV positive and HIV negative populations.

Secondly, our study finds an extremely high rate of treatment success in this HIV positive population following a 24 week course of PEG/RBV in acute and early chronic HCV infection. An SVR rate of 80% by ITT is in a similar range to that seen with treatment of AHC in HCV monoinfection [18-21] and one of the most successful SVR rates reported in HIV positive subjects to date (Table 1). Although based on a relatively small sample size, our study is still one of the largest reported in this setting. The excellent treatment response seen in our HIV positive group rate is especially encouraging given the high proportion of subjects with negative HCV-related prognostic markers at baseline (genotype 1, high baseline HCV RNA). Of particular note in our study is the inclusion of subjects with both acute HCV (as defined by an estimated duration of infection < 6 months) and early chronic HCV (estimated duration of HCV infection between 6 and 18 months). In fact the median estimated duration of infection prior to actual start of treatment was 30 weeks and was greater than 24 weeks in 80% of subjects. Although the numbers involved are small, there was no suggestion that SVR was reduced in those with early chronic infection (SVR 86%) versus those with acute HCV (SVR 77%).There is very little data on treatment outcomes in early chronic HCV infection, either in HCV monoinfected or HIV coinfected subjects, and thus our data is not only novel but also encouraging that 24 weeks PEG/RBV appears to be adequate for the majority of subjects in this group, including those with genotype 1 infection.

Monitoring early virological responses to predict HCV treatment outcome is increasingly common. RVR has been shown in chronic HCV infection to be a useful predictor of treatment outcome, both in HIV negative [22, 23] and HIV positive subjects [24, 25]. In acute HCV studies the utility of RVR has been less well-studied. Kamal et al reported an overall RVR rate of 86% [20] with a positive predictive value of 88% and a negative predictive value of 98%. In our study, although limited by the small sample size, RVR was shown to be an excellent predictor of SVR with 100% positive predictive value. These data suggest that RVR is an important predictor of SVR in AHC as well as CHC.

In summary, this report of the HIV positive subjects treated within our study establishes sexual or ‘permucosal’ transmission of AHC within HIV positive populations to be a global phenomenon. It also suggests that HCV in HIV positive individuals can be successfully treated with 24 weeks combination PEG/RBV not only in acute, but also in early chronic HCV infection. These findings support the importance of regular HCV testing in HIV positive MSM with consideration given to commencing early treatment for recently acquired HCV infection.

Acknowledgments

This study is funded by the National Institutes of Health (N.I.H.), U.S.A. Grant number: RO1 15999-01

The National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research is funded by the Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing and is affiliated with the Faculty of Medicine, The University of New South Wales.

Roche Pharmaceuticals supplied funding support for Peylated interferon –alfa-2a/ribavirin.

ATAHC Study Group

Protocol Steering Committee members

John Kaldor (NCHECR), Gregory Dore (NCHECR), Gail Matthews (NCHECR), Pip Marks (NCHECR), Andrew Lloyd (UNSW), Margaret Hellard (Burnet Institute, VIC), Paul Haber (University of Sydney), Rose Ffrench (Burnet Institute, VIC), Peter White (UNSW), William Rawlinson (UNSW), Carolyn Day (University of Sydney), Ingrid van Beek (Kirketon Road Centre), Geoff McCaughan (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital), Annie Madden (Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League, ACT), Kate Dolan (UNSW), Geoff Farrell (Canberra Hospital, ACT), Nick Crofts (Burnet Institute, VIC), William Sievert (Monash Medical Centre, VIC), David Baker (407 Doctors).

NCHECR ATAHC Research Staff

John Kaldor, Gregory Dore, Gail Matthews, Pip Marks, Barbara Yeung, Brian Acraman, Kathy Petoumenos, Janaki Amin, Carolyn Day, Anna Doab, Therese Carroll.

Burnet Institute Research Staff

Margaret Hellard, Oanh Nguyen.

Immunovirology Laboratory Research Staff

UNSW Pathology - Andrew Lloyd, Suzy Teutsch, Hui Li, Alieen Oon, Barbara Cameron.

SEALS – William Rawlinson, Brendan Jacka, Yong Pan.

Burnet Institute Laboratory, VIC – Rose Ffrench, Jacqueline Flynn, Kylie Goy.

Clinical Site Principal Investigators

Gregory Dore, St Vincent’s Hospital, NSW; Margaret Hellard, The Alfred Hospital, Infectious Disease Unit, VIC; David Shaw, Royal Adelaide Hospital, SA; Paul Haber, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital; Joe Sasadeusz, Royal Melbourne Hospital, VIC; Darrell Crawford, Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD; Ingrid van Beek, Kirketon Road Centre; Nghi Phung, Nepean Hospital; Jacob George, Westmead Hospital; Mark Bloch, Holdsworth House GP Practice; David Baker, 407 Doctors; Brian Hughes, John Hunter Hospital; Lindsay Mollison, Fremantle Hospital; Stuart Roberts, The Alfred Hospital, Gastroenterology Unit, VIC; William Sievert, Monash Medical Centre, VIC; Paul Desmond, St Vincent’s Hospital, VIC.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest : GM: travel scholarship/ speakers bureau Roche; MH: None; PH: None; BY: None; PM: None; DB: lecture and travel scholarship Roche; GMc: advisory board/research grant Roche; JS: Consulting/research grants Roche; PW: None; WR: None; AL: None; JK: None; GD: speakers bureau/ advisory board/travel scholarship/research grants Roche

References

- 1.Browne R, Asboe D, Gilleece Y, Atkins M, Mandalia S, Gazzard B, Nelson M. Increased numbers of acute hepatitis C infections in HIV positive homosexual men; is sexual transmission feeding the increase? Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:326–327. doi: 10.1136/sti.2003.008532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambotti L, Batisse D, Colin-de-Verdiere N, Delaroque-Astagneau E, Desenclos JC, Dominguez S, et al. Acute hepatitis C infection in HIV positive men who have sex with men in Paris, France, 2001-2004. Euro Surveill. 2005;10:115–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosn J, Pierre-Francois S, Thibault V, Duvivier C, Tubiana R, Simon A, et al. Acute hepatitis C in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. HIV Med. 2004;5:303–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotz HM, van Doornum G, Niesters HG, den Hollander JG, Thio HB, de Zwart O. A cluster of acute hepatitis C virus infection among men who have sex with men--results from contact tracing and public health implications. Aids. 2005;19:969–974. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000171412.61360.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serpaggi J, Chaix ML, Batisse D, Dupont C, Vallet-Pichard A, Fontaine H, et al. Sexually transmitted acute infection with a clustered genotype 4 hepatitis C virus in HIV-1-infected men and inefficacy of early antiviral therapy. Aids. 2006;20:233–240. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000200541.40633.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danta M, Brown D, Bhagani S, Pybus OG, Sabin CA, Nelson M, et al. Recent epidemic of acute hepatitis C virus in HIV-positive men who have sex with men linked to high-risk sexual behaviours. Aids. 2007;21:983–991. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281053a0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham CS, Baden LR, Yu E, Mrus JM, Carnie J, Heeren T, Koziel MJ. Influence of human immunodeficiency virus infection on the course of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:562–569. doi: 10.1086/321909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung RT, Andersen J, Volberding P, Robbins GK, Liu T, Sherman KE, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:451–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torriani FJ, Rodriguez-Torres M, Rockstroh JK, Lissen E, Gonzalez-Garcia J, Lazzarin A, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:438–450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogel M, Nattermann J, Baumgarten A, Klausen G, Bieniek B, Schewe K, et al. Pegylated interferon-alpha for the treatment of sexually transmitted acute hepatitis C in HIV-infected individuals. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:1097–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaeckel E, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Santantonio T, Mayer J, Zankel M, et al. Treatment of acute hepatitis C with interferon alfa-2b. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1452–1457. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlach JT, Diepolder HM, Zachoval R, Gruener NH, Jung MC, Ulsenheimer A, et al. Acute hepatitis C: high rate of both spontaneous and treatment-induced viral clearance. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:80–88. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00668-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santantonio T, Fasano M, Sinisi E, Guastadisegni A, Casalino C, Mazzola M, et al. Efficacy of a 24-week course of PEG-interferon alpha-2b monotherapy in patients with acute hepatitis C after failure of spontaneous clearance. J Hepatol. 2005;42:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiegand J, Buggisch P, Boecher W, Zeuzem S, Gelbmann CM, Berg T, et al. Early monotherapy with pegylated interferon alpha-2b for acute hepatitis C infection: the HEP-NET acute-HCV-II study. Hepatology. 2006;43:250–256. doi: 10.1002/hep.21043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel M, Bieniek B, Jessen H, Schewe CK, Hoffmann C, Baumgarten A, et al. Treatment of acute hepatitis C infection in HIV-infected patients: a retrospective analysis of eleven cases. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:207–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robotin MC, Copland J, Tallis G, Coleman D, Giele C, Carter L, et al. Surveillance for newly acquired hepatitis C in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2003.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danta M, Brown D, Bhagani S, Pybus OG, Sabin CA, Nelson M, et al. Recent epidemic of acute hepatitis C virus in HIV-positive men who have sex with men linked to high-risk sexual behaviours. Aids. 2007;21:983–991. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281053a0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calleri G, Cariti G, Gaiottino F, De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, et al. A short course of pegylated interferon-alpha in acute HCV hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:116–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2006.00802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamal SM, Fouly AE, Kamel RR, Hockenjos B, Al Tawil A, Khalifa KE, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b therapy in acute hepatitis C: impact of onset of therapy on sustained virologic response. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:632–638. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamal SM, Moustafa KN, Chen J, Fehr J, Abdel Moneim A, Khalifa KE, et al. Duration of peginterferon therapy in acute hepatitis C: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2006;43:923–931. doi: 10.1002/hep.21197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Rosa FG, Bargiacchi O, Audagnotto S, Garazzino S, Cariti G, Calleri G, et al. Twelve-week treatment of acute hepatitis C virus with pegylated interferon- alpha -2b in injection drug users. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:583–588. doi: 10.1086/520660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis GL, Wong JB, McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Harvey J, Albrecht J. Early virologic response to treatment with peginterferon alfa-2b plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2003;38:645–652. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferenci P. Predicting the therapeutic response in patients with chronic hepatitis C: the role of viral kinetic studies. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:15–18. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunez M, Marino A, Miralles C, Berdun MA, Sola J, Hernandez-Burruezo JJ, et al. Baseline serum hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA level and response at week 4 are the best predictors of relapse after treatment with pegylated interferon plus ribavirin in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:439–444. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318061b5d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crespo M, Esteban JI, Ribera E, Falco V, Sauleda S, Buti M, et al. Utility of week-4 viral response to tailor treatment duration in hepatitis C virus genotype 3/HIV co-infected patients. Aids. 2007;21:477–481. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328012b5ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luetkemeyer A, Hare CB, Stansell J, Tien PC, Charlesbois E, Lum P, et al. Clinical presentation and course of acute hepatitis C infection in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:31–36. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191281.77954.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dominguez S, Ghosn J, Valantin MA, Schruniger A, Simon A, Bonnard P, et al. Efficacy of early treatment of acute hepatitis C infection with pegylated interferon and ribavirin in HIV-infected patients. Aids. 2006;20:1157–1161. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226956.02719.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilleece YC, Browne RE, Asboe D, Atkins M, Mandalia S, Bower M, et al. Transmission of hepatitis C virus among HIV-positive homosexual men and response to a 24-week course of pegylated interferon and ribavirin. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:41–46. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000174930.64145.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]