Abstract

This is Part II of a two-part article on treatment of acute coronary syndrome in the older population. Part I (published in the October issue of Clinical Geriatrics) analyzed the differential utilization of invasive therapies with respect to age and heart disease. Part II summarizes information from the literature on acute coronary syndrome outcomes from invasive treatments (percutaneous coronary interventions or coronary artery bypass grafting) among older persons.

Introduction

The elderly are at high risk of acute coronary syndromes (ACS), but receive less cardiac medication and invasive care than other age groups.1 Two factors may explain this practice: (1) limited data from randomized clinical trials and (2) uncertainty about benefit and risk with advanced age.2

A basic understanding of how competing treatment strategies for ACS influence outcomes in older persons remains elusive. Part I of this review3 analyzed the differential utilization of therapies, challenges in diagnosing ACS in the context of comorbid conditions, and the lethality of ACS in older adults. The goal of Part II is to summarize published ACS outcomes results from invasive treatment strategies (percutaneous coronary interventions [PCIs] or coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]) in older persons. Through this analysis, we hope to provide an improved understanding of efficacy and appropriateness of ACS treatment (both medical and interventional) in the elderly.

Outcomes of Invasive Treatment of ACS in Older Persons

An ongoing controversy over treatment for older adults presenting with ACS is defined by the therapeutic choice of an ischemia-guided strategy versus an early invasive strategy. An ischemia-guided strategy refers to an initial plan for medical therapy with catheterization for recurrent symptoms (or stress-induced ischemia), whereas an early invasive strategy dictates cardiac catheterization within 48 hours of ACS presentation. Although therapy should be tailored to the level of risk, several studies have established superiority of an early invasive strategy in a broad population of patients, including the elderly, with unstable angina and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI).4–8

Invasive versus Conservative Treatment of NSTEMI in Older Persons

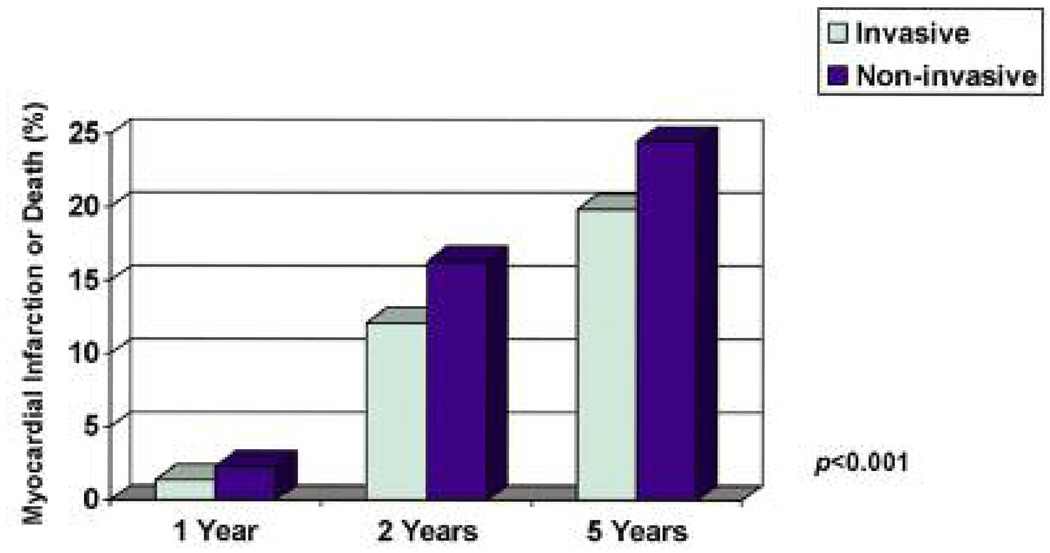

FRagmin and Fast Revascularization during InStability in Coronary artery disease (FRISC II) was the first randomized comparison of a conservative versus invasive strategy to demonstrate a significant event rate reduction in favor of an invasive strategy in the overall population.9 The protocol incorporated a 4-day stabilization period before intervention; thus, it was a “delayed invasive” strategy. The 6-month rate of death or myocardial infarction (MI) was lower with the invasive arm versus the conservative arm (8.3% vs 10.3%; P = 0.03), and at 1 year the death rate was significantly reduced (2.2% vs 3.9%; P = 0.016).9 Although this study excluded patients 75 years of age and older, the subgroup 65 years of age and older had a greater absolute (5.3% vs 0%) and relative (33.5% vs 0%) reduction in death or MI at 6 months as compared with the younger subgroup. This benefit increased (Figure) at 2 years and again at 5 years.10 The positive influence of an invasive strategy in FRISC II may be explained by the high rate of revascularization (78% in the invasive arm) and concurrent medical therapy, optimizing the benefit of revascularization.

Figure.

In FRISC II, patients 65 and older had increased occurrence of subsequent myocardial infarction or death with a noninvasive treatment strategy for ACS (vs invasive).10

Using the Treat angina with Aggrastat and determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy–Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction (TACTICS-TIMI 18) trial,8 Bach et al analyzed clinical outcome by age in older patients presenting with ACS who were randomly assigned to an early invasive or conservative management strategy. This multicenter trial involved 2220 patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI. At 6 months, the primary composite endpoint of death, MI, or rehospitalization was lower in the invasive arm than in the conservative arm (15.9% vs 19.4%; P = 0.026). An elderly age subgroup analysis from this trial11 found a substantial treatment effect in favor of an invasive strategy for the reduction of death or MI with advancing age. When the elderly were compared with younger patients, the early invasive strategy yielded a greater absolute (4.1% vs 1%) and relative (42% vs 20.4%) risk reduction in death or MI at 30 days in the subgroup 65 years of age and older. Similarly, among patients 75 years of age and older, the absolute (10.8%) and relative (56%) reduction in death or MI with the early invasive strategy was even greater (event rates: 10.8% vs 21.6%; P = 0.02). A significant age–treatment interaction was present in favor of better outcome with invasive care in those 75 years of age and older (P = 0.044). This benefit persisted despite a threefold higher risk of major bleeding with the early invasive strategy in patients 75 years of age and older (16.6% vs 6.5%; P = 0.009). From a clinical perspective, the number needed to treat with invasive care to prevent one death or MI was 250 among those age 65 years and younger, 21 among those age 66–74, and just nine for those 75 years of age and older ((Table). Consistent with the findings from FRISC II, younger patients (< 65 yr) had good outcomes regardless of the treatment strategy.

TABLE 1.

With Respect to Age, the Number of Patients Required to Treat with Invasive Therapy to Prevent One Myocardial Infarction or Death

| Age | Treatment Ratio |

|---|---|

| ≤ 65 yr | 1 in 250 |

| 66–74 yr | 1 in 21 |

| ≥ 75 yr | 1 in 9 |

The analysis of the effect of age on outcomes in the TACTICS-TIMI 18 trial led to several conclusions challenging assumptions and current practice patterns in older persons. First, as compared with younger patients, older patients with unstable angina and NSTEMI have a markedly increased rate of adverse ischemic outcomes. Second, routine early invasive strategy reduces death or nonfatal MI among elderly patients. Third, this aggressive strategy has greater absolute benefit for reduction of death or nonfatal MI in older patients than in younger patients. Fourth, the early invasive strategy may be more cost-effective in the elderly, largely because it prevents death or MI in this group. Fifth, a routine early invasive strategy does not increase the incidence of stroke, even among older persons.

But the news isn’t all good for an early invasive strategy. A recent trial comparing selective invasive versus routine invasive care (Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable Coronary Syndromes [ICTUS]) in patients with positive troponins and NSTEMI demonstrated no overall differences with regard to the combined endpoint (death, MI, or rehospitalization for angina) at 1 year, with a trend to less angina and fewer fatal MIs among invasively managed patients.12 The average age was 62 years. However, in an elderly subgroup (≥ 65 yr) analysis, a nonsignificant trend favored early invasive care.12 Another study, an observational analysis in a community population, failed to demonstrate an early benefit from an invasive strategy with inhospital survival in the elderly subgroup (≥ 75 yr).13 These inconsistent observations highlight the need for continued caution in the uniform application of trial results in the elderly13 and underscore the need for further randomized controlled trials of older persons with regard to treatment strategies for ACS.

PCI (vs Fibrinolysis) Outcomes in Older Persons with STEMI

In the subgroup of patients with ACS identified as having ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the current rationale is to reperfuse ischemic myocardium emergently. The benefits are thought to outweigh the risk in the vast majority of patients in this higher-risk group. Reperfusion therapy is approached by two mechanisms emergently: (1) fibrinolysis or (2) coronary angiography with PCI.

Three small trials were performed to specifically address the question of fibrinolytic therapy or PCI in elderly STEMI patients. The first trial randomized patients over 75 years of age (n = 87) to PCI versus fibrinolytic therapy (streptokinase). Patients treated with PCI demonstrated lower rates of death, MI, or stroke at 30 days (9% vs 29%; P = 0.01).14 Another trial randomized patients 70 years of age and older (n = 130) to PCI (with stenting) versus fibrinolytic therapy (tPA). At 6 months, no difference in mortality rate was observed, but significantly fewer subsequent revascularization procedures in the PCI group (9% vs 61%; P = 0.001) occurred and the PCI group had a lower composite of death, MI, or revascularization (29% vs 93%; P = 0.001).15 A prospective randomized trial, Senior Primary Angioplasty in Myocardial Infarction (Senior PAMI), randomized patients 70 years of age and older (n = 481) presenting less than 12 hours from symptom onset to PCI versus fibrinolytic therapy.16 In this study, a nonsignificant 36% reduction in death or nonfatal stroke (11.3% PCI vs 13% thrombolytic therapy; P = 0.57) resulted. If recurrence of ischemia was added to the composite endpoint a significant 55% reduction in death, stroke, or reinfarction (11.6% PCI vs 18% thrombolytic therapy; P = 0.05) favored PCI. No difference between reperfusion strategies was seen in the small subgroup 80 years of age and older (n = 131).16

Although these trials represent small numbers, the advantages of PCI over fibrinolysis appear to be amplified when analyzing pooled trials to increase the number of older patients. The investigators expanded the analysis to include 22 randomized trials of PCI versus fibrinolytic therapy. There was a benefit with PCI, particularly if the patient arrived 2 hours after symptom onset or if the patient was 65 years of age or older.17 A subgroup analysis found that the absolute mortality advantage of PCI increased with age from 1% at 65 years to 6.9% at 85 years of age and older.18

Quality of Life After Intervention in Older Persons

The Angioplasty Compared to MEdical therapy (ACME) trial was the first randomized trial to examine the effect of different therapies on quality-of-life measures,19 showing a greater improvement in physical and psychological measures in patients assigned angioplasty. The larger second Randomized Intervention Treatment of Angina (RITA-2) trial20 confirmed these findings up to 1 year, particularly for physical functioning, vitality, and general health. An attenuation of this improvement over 3 years was partly attributed to 27% of medically-treated patients receiving revascularization during follow-up.19 In the present study, similar tools for quality-of-life assessment were applied to an elderly population and confirmed an overall improvement in general health and pain status with both medical and revascularization therapies.19 This effect was somewhat greater after revascularization in both patient groups, minimizing the difference between treatments in overall results. The improvements in symptomatic status and general well-being are particularly important in view of the fact that quality of life is of primary importance for 80-year-old patients—more important than prolongation of life.

Outcomes of CABG in Older Persons

The characteristics of patients undergoing heart surgery have changed over time. The patients undergoing operations for coronary artery disease (CAD) are now older with more comorbid conditions. Warner et al21 prospectively studied and compared 23,512 patients undergoing CABG during three time periods from 1981 to 1995. The mean age and the percentage of patients age 65 years or older were significantly higher in the later time periods. In a multivariate analysis for predictors of mortality, these researchers found that patients age 65 and older in the more recent cohort of patients had an odds ratio of 2.7 for mortality.21 Patients age 80 and over were found to have a significantly higher risk of any complication with surgery, including neurologic events, pneumonia, arrhythmias, or wound infection. Despite higher complication and mortality rates in older persons, the question that remains is whether the potential benefit of CABG (or PCI) outweighs the risk of the procedure.

Given similar health status benefits, the principal barrier in recommending CABG (instead of PCI) to older patients appears to be greater perceived risk. Yet, several studies have shown that age alone is insufficient to prohibit CABG surgery.22–25 Keon26 demonstrated a steady reduction in mortality from isolated CABG in the elderly over the past three decades. While he attributed these results to improved surgical techniques, better postoperative care, and careful selection of surgical candidates, his finding of a marginal increase in mortality among older patients (3.7% vs 1.6%) argues that age alone is a misleading criteria for avoidance of cardiac surgery.26 Using a prospective design, a consecutive series of 690 patients undergoing CABG had serial assessments of procedural impact on measures of functional status, symptom burden, and quality of life.27 Older patients demonstrated absolute improvements in physical function, angina frequency, and quality of life, and without statistically significant differences between older and younger subjects. In fact, the trends favored a greater reduction in angina frequency and an enhanced overall quality of life 1 year after surgery in the elderly as compared with younger subjects. Graham and colleagues28 found revascularization to be superior to optimal medical treatment: patients age 80 years and older undergoing CABG had a 4-year survival rate of 77.4% as compared with 60.3% in patients treated medically. In particular, these researchers noted improved 1-year survival in the subset of patients with left main CAD undergoing revascularization.

These findings, along with previous studies, indicate that older subjects confront increased risk of complications from heart disease than younger cohorts,29 suggesting that elderly patients may benefit more from interventions than younger counterparts.

Outcomes of CABG (vs PCI) in Older Persons

The prevailing invasive treatment strategy for ACS in the elderly is PCI. This dominant strategy suggests that a “less-invasive” myocardial revascularization procedure (such as PCI) affords attenuated morbidity and mortality in older persons as compared to CABG.

In an early attempt to understand the influence of age on outcomes in patients with CAD, the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) trial prospectively enrolled 1829 patients with symptomatic multivessel CAD requiring revascularization who were randomly assigned to undergo either CABG or PCI.30 Of the patients, 709 (39%) were age 65 to 80 years at baseline; the other 1120 were younger than 65 years. The inhospital 30-day mortality rate for PCI and CABG in the younger patients was 0.7% and 1.1%, respectively, and the rate for patients age 65 years or older was 1.7% and 1.7%, respectively. In both age groups, CABG resulted in greater relief of angina and fewer repeat procedures. The 5-year survival rate in patients younger than age 65 years was 91.5% for CABG and 89.5% for PCI. In patients age 65 years or older, the 5-year survival rate was 85.7% for CABG and 81.4% for PCI. It appears within the context of the BARI trial that older patients assigned to CABG (instead of PCI) had less recurrent angina, were less likely to undergo repeat procedures, and were less likely to die.

In a European randomized controlled trial, 255 patients age 75 years or older were randomized to optimal medical treatment or revascularization (PCI or CABG).31 Patients in both groups were clinically improved with enhanced general well-being during follow-up, but this improvement was greater after surgical revascularization. A full third of patients in the optimum medical group crossed over to revascularization during follow-up for refractory symptoms. Overall, the invasive approach was followed by a significantly lower rate of major adverse cardiac events, particularly nonfatal ischemic events, and carried only a marginal intervention.

Upon review of the New York Cardiac Registry, Hannan et al32 compared outcomes of PCI (with drugeluting stents) versus CABG. The major findings of the study were that among patients with three-vessel disease or two-vessel disease, those treated with CABG had significantly lower adjusted rates of death and of death or MI than those treated with drug-eluting stents; and patients who were at least 80 years old who underwent CABG had significantly lower rates of death or MI.

Open-heart surgery in octogenarians has risen steadily since the 1980s. A number of factors justify this increase. Cane and colleagues33 demonstrated actuarial survival for octogenarians undergoing CABG that is comparable to that of the age-matched population. They concluded that octogenarians should be offered the opportunity for CABG “with the expectation of reasonable results and late survival that parallels their demographic group.” In a retrospective study of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons National Database, Bridges et al34 found that operative mortality and complication rates from CABG are highest for those in their 90s and over age 100. But with careful patient selection, the study found, most of the patients had a lower risk of CABG-related mortality.34 Other investigators have noted that octogenarians enjoy a higher quality of life after undergoing CABG or valve surgery. For example, in their review of 68 octogenarians undergoing CABG or valve surgery, Kumar and colleagues35 found that approximately 85% of patients reported that, in retrospect, they definitely would have made the decision to undergo open-heart surgery.

Conclusion

The coalescence of a rapidly expanding cohort of older persons and the dominance of heart disease as the major cause of mortality in the United States challenges healthcare providers to analyze therapeutic strategies for ACS in older patients. Age influences the presentation of disease and is entwined with comorbid conditions; therefore, age may bias treatment strategy selection toward less-invasive interventions such as PCI and away from more invasive strategies such as CABG.

Selection of older patients for an early invasive strategy is complex, given the need to consider risk from disease and risk from intervention, but given the benefits observed in recent trials, age alone should not preclude its consideration, but rather should intensify it.

We must explicitly ask which strategies are beneficial. This review suggests that “interventional” strategies provide an opportunity for improved outcomes in older persons with ACS. The choice of which intervention is better to use (PCI or CABG) remains undefined, but future studies must include older patients and define age-sensitive outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by NIH Grant 1R01AG025801-01A1.

SPONSOR

This activity is sponsored by NACCME.

DISCLOSURES

All those in a position to control content of continuing education programs sponsored by NACCME, LLC are required to disclose any relevant financial relationships with relevant commercial companies related to this activity. All relevant relationships that are identified are reviewed for potential conflicts of interest. If a conflict is identified, it is the responsibility of NACCME to initiate a mechanism to resolve the conflict(s). The existence of these interests or relationships is not viewed as implying bias or decreasing the value of the presentation. All educational materials are reviewed for fair balance, scientific objectivity of studies reported, and levels of evidence.

Planning Committee: T. Levy, NACCME, and C. Ciraulo and S. Gephart, HMP Communications, have disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any commercial interest.

Editor: M. Edwards has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any commercial interest.

Faculty:

Dr. Sheridan has disclosed that he is a consultant for Pfizer.

Dr. Stearns, Dr. Massing, Dr. Stouffer, Ms. D’Arcy, and Dr. Carey have disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any commercial interest.

Clinical Reviewer: Dr. Christmas has disclosed no relevant financial relationship with any commercial interest.

Footnotes

TARGET AUDIENCE

Internists, family practitioners, geriatricians, cardiologists, and others who care for older patients.

METHOD OF PARTICIPATION/SUCCESSFUL COMPLETION

To be eligible for documentation of credit, participants must read all article content, log on to www.naccme.com to complete the online post-test with a score of 70% or better, and complete the online evaluation form. Participants who successfully complete the post-test and evaluation form online may immediately print their documentation of credit. Please e-mail info@naccme.com or call (609) 371-1137 if you have questions or need additional information.

ACCREDITATION

MD/DO:

This activity is sponsored by the North American Center for Continuing Medical Education (NACCME). NACCME is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. NACCME designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity. This activity has been planned and produced in accordance with the ACCME Essential Areas and Policies.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

- Understand advantages of early interventional management of acute coronary syndrome in older persons.

- Discuss the benefits of percutaneous coronary intervention over fibrinolysis in the treatment of acute coronary syndrome in the elderly.

- Describe the advantages of coronary artery bypass grafting over percutaneous coronary intervention in older patients with coronary artery disease in more than one vessel.

- Understand the increased risk with increasing age for coronary artery bypass grafting.

References

- 1.Avezum A, Makdisse M, Spencer F, et al. GRACE Investigators. Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: Observations from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am Heart J. 2005;149:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee PY, Alexander KP, Hammill BG, et al. Representation of elderly persons and women in published randomized trials of acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2001;286:708–713. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.6.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheridan BC, Stearns SC, Massing MW, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting: Intervention in older persons with acute coronary syndrome—Part I. Clinical Geriatrics. 2008;16(10):39–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, et al. TACTICS (Treat Angina with Aggrastat and Determine Cost of Therapy with an Invasive or Conservative Strategy)-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 18 Investigators. Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1879–1887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106213442501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallentin L, Lagerqvist B, Husted S, et al. Outcome at 1 year after an invasive compared with a non-invasive strategy in unstable coronary-artery disease: The FRISC II invasive randomised trial. FRISC II Investigators. Fast Revascularisation during Instability in Coronary artery disease. Lancet. 2000;356:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02427-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spacek R, Widimsky P, Straka Z, et al. Value of first day angiography/angioplasty in evolving Non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction: An open multicenter randomized trial. The VINO Study. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:230–238. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalis LK, Stroumbis CS, Pappas K, et al. Treatment of refractory unstable angina in geographically isolated areas without cardiac surgery. Invasive versus conservative strategy (TRUCS study) Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1954–1959. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bach RG, Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, et al. The effect of routine, early invasive management on outcome for elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:186–195. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long-term low-molecular-mass heparin in unstable coronary-artery disease: FRISC II prospective randomised multicentre study. FRagmin and Fast Revascularisation during InStability in Coronary artery disease. Lancet. 1999;354(9180):701–707. (FRISC II) Investigators [published correction appears in Lancet 1999;354(9188):1478] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lagerqvist B, Husted S, Kontny F, et al. Fast Revascularization during InStability in coronary artery disease-II Investigators. A long-term perspective on the protective effects of an early invasive strategy in unstable coronary artery disease: Two-year follow-up of the FRISC-II invasive study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1902–1914. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etzioni RD, Riley GF, Ramsey SD, Brown M. Measuring costs: Administrative claims data, clinical trials and beyond. Medical Care. 2002;40(6 Suppl):III63–III72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, et al. Invasive versus Conservative Treatment in Unstable Coronary Syndromes (ICTUS) Investigators. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1095–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt DL, Roe MT, Peterson ED, et al. CRUSADE Investigators. Utilization of early invasive management strategies for high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: Results from the CRUSADE Quality Improvement Initiative. JAMA. 2004;292:2096–2104. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.17.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boer MJ, Ottervanger JP, van’t Hof AW, et al. Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Reperfusion therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: A randomized comparison of primary angioplasty and thrombolytic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1723–1728. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldenberg I, Matetzky S, Halkin A, et al. Primary angioplasty with routine stenting compared with thrombolytic therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2003;145:862–867. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(02)94709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grines CL. Presented at: Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics Meeting. Washington, D.C: 2005. Oct, Senior PAMI: A prospective randomized trial of primary angioplasty and thrombolytic therapy in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boersma E. The Primary Coronary Angioplasty vs Thrombolysis Group. Does time matter? A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:779–788. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi810. Published Online: March 2, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, et al. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: In collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2570–2589. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss WE, Fortin T, Hartigan P, et al. A comparison of quality of life scores in patients with angina pectoris after angioplasty compared with after medical therapy. Outcomes of a randomized clinical trial. Veterans Affairs Study of Angioplasty Compared to Medical Therapy Investigators. Circulation. 1995;92:1710–1719. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocock SJ, Henderson RA, Clayton T, et al. Quality of life after coronary angioplasty or continued medical treatment for angina: Three-year follow-up in the RITA-2 trial. Randomized Intervention Treatment of Angina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00637-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner CD, Weintraub WS, Craver JM, et al. Effect of cardiac surgery patient characteristics on patient outcomes from 1981 through 1995. Circulation. 1997;96:1575–1579. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaidi AM, Fitzpatrick AP, Keenan DJ, et al. Good outcomes from cardiac surgery in the over 70s. Heart. 1999;82:134–137. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirose H, Amano A, Yoshida S, et al. Coronary artery bypass grafting in the elderly. Chest. 2000;117:1262–1270. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fruitman DS, MacDougall CE, Ross DB. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: Can elderly patients benefit? Quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;68:2129–2135. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00818-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalrymple-Hay MJ, Alzetani A, Aboel-Nazar S, et al. Cardiac surgery in the elderly. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:61–66. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keon WJ. Isolated CABG in the elderly: Operative results and risk factors over the past three decades. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 1996;5:26–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conaway DG, House J, Bandt K, et al. The elderly: Health status benefits and recovery of function one year after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1421–1426. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graham MM, Ghali WA, Faris PD, et al. Alberta Provincial Project for Outcomes Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease (APPROACH) Investigators. Survival after coronary revascularization in the elderly. Circulation. 2002;105:2378–2384. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016640.99114.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen Maycock CA, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, et al. Intermountain Heart Collaborative Study. Statin therapy is associated with reduced mortality across all age groups of individuals with significant coronary disease, including very elderly patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1777–1785. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02477-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mullany CJ, Mock MB, Brooks MM, et al. Effect of age in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation (BARI) randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:396–403. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)01191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The TIME Investigators. Trial of invasive versus medical therapy in elderly patients with chronic symptomatic coronary-artery disease (TIME): A randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:951–957. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hannan EL, Wu C, Walford G, et al. Drug-eluting stents vs. coronary-artery bypass grafting in multivessel coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:331–341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cane ME, Chen C, Bailey BM, et al. CABG in octogenarians: Early and late events and actuarial survival in comparison with a matched population. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:1033–1037. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00429-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bridges CR, Edwards FH, Peterson ED, et al. Cardiac surgery in nonagenarians and centenarians. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:347–357. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar P, Zehr KJ, Chang A, et al. Quality of life in octogenarians after open heart surgery. Chest. 1995;108:919–926. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]