Abstract

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by dyslipidemia and accumulation of lipids in the arterial intima, with activation of both innate and adaptive immunity. Reciprocally, dyslipidemia associated with atherosclerosis can perturb normal immune function. Natural killer T (NKT) cells are a specialized group of immune cells that share characteristics with both conventional T cells and natural killer cells. However, unlike these cells, NKT cells recognize glycolipid antigens and produce both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines upon activation. Because of these unique characteristics, NKT cells have recently been ascribed a role in the regulation of immunity and inflammation, including cardiovascular disease. In addition, NKT cells represent a bridge between dyslipidemia and immune regulation. This review summarizes the current knowledge of NKT cells and discusses the interplay between dyslipidemia and the normal functions of NKT cells and how this might modulate inflammation and atherosclerosis.

Key Words: Adaptive immunity, Atherosclerosis, Chronic inflammation, Dyslipidemia, Immune regulation, Innate immunity, Natural killer T cells

Introduction

Over the past 2 decades, atherosclerosis has gained recognition as an immune-mediated process. Many investigators have elegantly demonstrated that not only does cholesterol homeostasis play a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, but that innate and adaptive immunity are important in this disease. Atherosclerosis is modulated by infection [1], immunodeficiency [2] and autoimmunity [3]. Perhaps one of the most interesting recent discoveries is that circulating lipids and immunity are closely linked and have a great deal of influence on each other. For example, it has been demonstrated that apolipoproteins, such as apoliprotein (apo)E and apo-AI, i.e. molecules that have extensively been studied for their role in lipoprotein metabolism and clearance, also have important roles in the development of normal immune responses and inhibiting inflammation [4,5]. Conversely, it has been shown that modified lipoproteins, such as oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL), can have detrimental effects on inflammation by promoting chemotaxis and cytokine secretion by macrophages [6]. In fact, oxLDL is one of the most prevalent antigens associated with atherosclerosis eliciting specific responses from both B and T cells. Almost every aspect of immunity, including apoptosis and efficient clearance of apoptotic cells by macrophages, has been highlighted as either being protective or pathogenic in the atherosclerotic process.

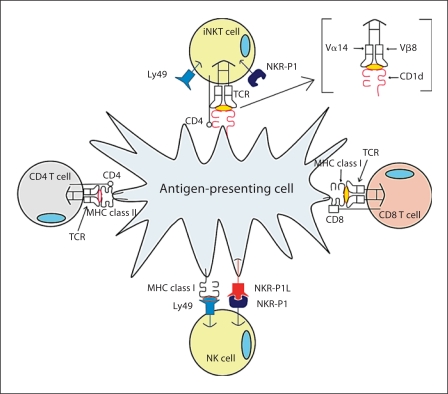

The purpose of this review is to highlight the importance of an interesting member of the innate immune system that shares qualities with cells of both innate and adaptive immune responses: natural killer T (NKT) cells. As detailed in the following sections, NKT cells are unique effector cells that share identity with traditional NK cells and classical T cells (fig. 1). Numerous investigators have demonstrated regulatory roles of NKT cells and have found that, although few in number, their presence and responses can have a catalytic impact on disease progression. Their importance in atherosclerosis was emphasized in 2004, when three studies were published demonstrating that activation of NKT cells by specific ligand resulted in enhanced aortic lesion formation [7,8,9]. In this review, we will discuss atherosclerosis as a disease of the immune system, as well as the unique characteristics of NKT cells and why they are relevant to study in the context of chronic inflammation and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Fig. 1.

iNKT cell receptor expression in comparison to NK cells and conventional CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Atherosclerosis and Immunity

Atherosclerosis is a disease involving many cellular processes, and has long been associated with hypercholesterolemia. A growing body of evidence also supports the role of inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Studies in CVD have suggested both anti- and pro-atherogenic roles for immunity. In general, it has been demonstrated that macrophages and T cells make up the largest percentage of immune cells present in the atherosclerotic plaque and they appear to contribute to the inflammatory process by producing cytokines that attract smooth muscle cells and other lymphocytes, and compromise plaque stability [10]. CD4+ T cells reactive against oxLDL can be isolated from human atherosclerotic lesions [11], and studies in T-cell-deficient mice have demonstrated a pro-atherogenic role for conventional CD4+ T cells. Conversely, CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells have been shown to protect against atherosclerosis [12,13].

Although it was thought that B cells were present in few numbers in lesions, Galkina et al. [14] recently demonstrated that B cells are a significant population in both normal and atherosclerotic mouse aortas. The effects of B cells and the antibodies they produce seem to depend on their antigen specificity. For example, although titers of oxLDL antibodies are shown to correlate directly with severity of disease and are often used as markers of CVD risk [15,16,17,18], antibodies generated against modified phospholipid (such as phosphorylcholine found in oxLDL and apoptotic cells) have been shown to be protective [19,20,21,22]. In fact, immunization of atherosclerosis-susceptible rabbits and mice with oxLDL and malondialdehyde (MDA)-LDL results in protection against atherosclerosis [22,23], perhaps via a strong Th2 (anti-inflammatory) polarization which seems to rely heavily on IL-5-mediated stimulation of B-1 B cells [20]. Conversely, antibodies against β2-glycoprotein I (β2GPI; identified in both humans suffering from CVD and in animal models of atherosclerosis [24,25,26,27,28]) are thought to promote atherosclerosis [29,30], and immunization of animals with HSP-60/65 results in increased atherosclerosis [30,31,32]. Finally, we have shown that specific deletion of B cells in LDLr–/– mice results in enhanced atherosclerosis compared to control animals [33]. Therefore, it is possible that the ‘quality’ of the antibody response (i.e. isotype or antigen specificity) may influence the atherosclerosis outcome. For more in depth discussion regarding adaptive immunity and atherosclerosis see recent reviews on this topic [34,35].

Innate Immunity and Atherosclerosis

It is no secret that innate immunity plays a major role in the atherosclerotic process. Macrophages, NK cells, mast cells and dendritic cells have all been studied and shown to play a role in plaque progression [35,36]. Macrophages are the initial and primary cell type that make up lesions both in humans and mice. Numerous studies have focused on the role of macrophages in CVD from the aspect of cells important for cholesterol homeostasis and scavenging modified lipoproteins and apoptotic cells [37] to their role as mediators of basic inflammatory responses.

More recent studies have demonstrated that macrophages have a unique ability to regulate inflammation in atherosclerosis via the expression of Toll-like receptors (TLRs). These receptors, specifically TLR-4 [38], TLR-2 [39] and most recently TLR-9 [40], have been shown to play integral roles in the development of atherogenic plaques. Mice that are deficient in MyD-88, a shared adapter molecule for TLR-4, TLR-2 and TLR-9, have been shown to have decreased atherosclerosis on the apoE–/– and LDLr–/– background [38]. These studies demonstrated that receptors and molecules once thought to only function in immunity against infection have specific roles in the atherogenic process. This further emphasizes that atherosclerosis is more than simply a disease associated with lipid metabolism and that the intricate interplay between immunity, inflammation and dyslipidemia is a significant area of further investigation.

Invariant NKT Cells

In addition to the more mainstream members of the innate and acquired immune system, recent studies have highlighted the role of a less traditional cell type, NKT cells, and their role in chronic inflammatory diseases. NKT cells are a unique subset of T lymphocytes that share surface receptors with both conventional T cells (TCR and CD4) and natural killer (NK) cells (NK1.1 and Ly49) and are found in both humans and mice. NKT cells are abundant in the liver and most lymphoid tissues, and type I NKT cells, or invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, have a restricted T-cell receptor expression (Vα14-Jα18/Vβ8 in mice and Vα24-Jα18/Vβ11 in humans) [41]. However, unlike conventional T cells which recognize peptide antigens presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) I or MHC II molecules, iNKT cells recognize glycolipid antigen presented by the non-classical antigen-presenting molecule CD1d on antigen-presenting cells (APCs). Upon activation, iNKT cells rapidly secrete large amounts of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-10 and IL-13, and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, which allows for a wide range of regulatory potential [42]. Activated iNKT cells can also promote dendritic cell maturation and monocyte activation by signaling through CD1d [43], and are capable of inducing tolerance by communicating with regulatory T cells [44]. In addition to displaying immune-regulating properties, iNKT cells have been implicated in a variety of disease conditions, thus modulation of the functions of these cells may lead to potential therapies. For example, studies involving autoimmune diseases (highlighted below) have shown that iNKT cells suppress inflammation [45,46,47]. iNKT cells have also been shown to increase anti-tumor immunity [48] and protect against infections [49]. In contrast, our laboratory [7] and others [8,9] have demonstrated that iNKT cells are pro-atherogenic in both apoE–/– and LDLr–/– mice, as well as C57BL/6 mice on a high-fat diet.

Although few physiological ligand(s) are known, iNKT cells strongly respond to and are specifically activated by α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer), a glycosphingolipid originally isolated from a marine sponge (Agelas mauritanus). First identified for its anti-metastatic properties, α-GalCer specifically binds to CD1d on APCs and selectively activates iNKT cells [50]. Activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer (synthetic homologue KRN7000) in vivo has been shown to suppress inflammation in autoimmune diseases such as type-1 diabetes in mice [51]; however it has also been shown to exacerbate atherosclerosis [7,8,9]. iNKT cells are also activated by other ‘natural’ glycolipid ligands, albeit much less effectively. For example, several bacterial glycolipids have been shown to activate iNKT cells and may possibly play a role in clearing of infections by iNKT cells. Among these are α-galactosyldiacylglycerols expressed by Gram-negative, LPS-negative Borrelia burgdorferi and α-galacturonosylceramide and α-glucuronosylceramide derived from Gram-negative, LPS-negative Sphingomonas[52].

iNKT Cell Ontogeny

iNKT cells undergo thymic development similar to conventional T cells, however they diverge during the double-positive thymocyte stage of development [53]. In contrast to the selection of conventional T cells by peptide antigens presented by MHC molecules, iNKT cell selection requires glycolipid antigen presented by CD1d on double-positive cortical thymocytes [54]. Once positively selected, iNKT cells undergo expansion within the thymus. Most iNKT cells leave the thymus as immature (NK1.1–) cells and further mature in the periphery [55,56], however, recent studies have shown that a smaller portion of mature NKT cells remain NK1.1– in peripheral tissues and are functionally distinct from the NK1.1+ population [57].

Mature iNKT cells have the capability to rapidly produce large amounts of cytokines upon activation. Although a variety of lipid antigens have been shown to activate iNKT cells, each of these molecules must be presented to iNKT cells by CD1d. CD1d is an MHC class I-like molecule constitutively expressed by APCs, such as macrophages, dendritic cells and B cells [58]. Shortly after biosynthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum, CD1d is loaded with endogenous lipid by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and trafficked to the plasma membrane. CD1d then undergoes extensive recycling between the plasma membrane and lysosome, where saposins facilitate lipid exchange.

Saposins are a group of four lipid transfer proteins derived from a common precursor, termed prosaposin [59]. A genetic link between iNKT cells and lipid metabolism was demonstrated in studies using prosaposin-deficient mice, which lack iNKT cells and display impaired ability to present iNKT ligand [60]. The deep hydrophobic antigen-binding pocket of CD1d allows for glycolipid antigen binding [61] and, after trafficking to the plasma membrane, lipid antigen-loaded CD1d engages the invariant TCR on the iNKT cell leading to subsequent activation and rapid cytokine production.

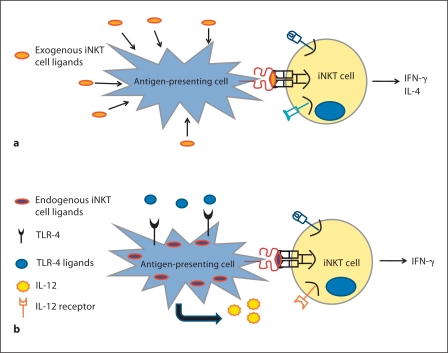

In addition to this direct pathway of activation by glycolipid antigens presented on CD1d, iNKT cell activation can also occur via an indirect mechanism first involving APC activation (fig. 2). Briefly, TLR-mediated activation of APCs leads to proinflammatory cytokine production which, along with weak interaction of iNKT cells with endogenous antigens, can activate iNKT cells [62].

Fig. 2.

Potential mechanisms of iNKT cell activation. a Direct activation of iNKT cells via exogenous glycolipids, such as α - GalCer, taken up by APCs and presented on CD1d. b Indirect activation of iNKT cells via TLR activation of APCs. Proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, produced during APC activation, activate iNKT cells in combination with weak interactions of the iNKT cells with endogenous antigens.

iNKT Cells and Infection

Cells of the iNKT lineage are essential components in the fight against infectious agents. Much like the cells of the innate immune system, iNKT cells are capable of recognizing pathogenic structures of similar patterns. An infectious agent capable of eliciting an iNKT cell response is the Gram-negative spirochete bacterium causative of Lyme disease: B. burgdorferi [63]. In a study performed to elucidate the B.-burgdorferi-mediated mechanism of iNKT cell activation, it was reported that BbGL-IIc, a galactosyl diacylglycerol comprising 12% of the lipid content of B. burgdorferi, is responsible for proliferation and activation of splenic and hepatic iNKT cells derived from C57BL/6 mice. BbGL-IIc associated with CD1d and variants of this lipid were ineffective at eliciting similar activated phenotypes on iNKT cells [64]. These data indicate that iNKT cells can respond to specific pathogen lipid components through direct engagement of their TCR. In a recent study, C57BL/6 mice lacking iNKT cells exhibited severe heart inflammation and bacterial burden in response to B. burgdorferi challenge. In contrast, it was found that C57BL/6 mice with functional iNKT cells were found to have reduced bacterial loads and mitigated symptoms of disease [65]. In this infectious model, iNKT cells were found to migrate to infected sites of the heart and provide protection via secreted IFN-γ and macrophage activation. A different, well-studied example of iNKT cell activation via microbial glycolipids includes GSL-1 derived from Sphingomona paucimobilis[66]. Just like BbGL-IIc, GSL-1 was found to load on CD1d and produce an iNKT-cell-mediated response. The only characteristic shared by these two iNKT cell ligands is an α-anomeric sugar attached to the different lipid groups [63]. These examples of glycolipid recognition illustrate the ability of iNKT cells to behave like cells of the innate immune system by responding to similar molecular patterns associated with different pathogens.

iNKT Cells and Cancer

Harnessing cytotoxic effects of iNKT cells to targets responsible for the formation of cancer has been one of the main drivers of research for this cell type. The marine-sponge-derived synthetic iNKT cell ligand α-GalCer was discovered by its ability to prevent metastatic tumor formation [67,68]. When iNKT cells were discovered to be the main cell type responsible for recognition of α-GalCer, great excitement followed research to understand their mechanism of tumor suppression [69]. This excitement has been met with difficulty to detect the endogenous lipid ligands present in cancer cells responsible for iNKT cell activation [70]. Early studies of mice deficient in iNKT cells provided an indirect measure to study resistance to tumor formation. In murine models of tumor induction mediated by methylcholanthrene-induced fibrosarcomas, it was shown that passive transfer of iNKT cells provided protection against sarcoma formation [71]. Initial findings of iNKT cell immunogenicity have driven scientific groups to produce iNKT cell vaccines that provide immunity against tumor formation. In an iNKT cell vaccine study [72], it was reported that loading of a non-immunogenic murine lymphoma cell line, A20, with α-GalCer produced tumor-specific protective immunity. Mice re-challenged with A20 cells exhibited a memory phenotype protecting mice against lymphoma formation. These studies have shown the adaptive immune system becomes activated following inoculation with iNKT-cell-specific vaccine. Adaptive immunity involvement is an interesting outcome and elucidating this mechanism would be a breakthrough in cancer research; it would provide a system that bridges innate and adaptive immunity and targets tumor cells. Translation of this protection to humans has proven difficult, as NKT cell frequency is lower in human spleen, thymus and blood than in mice [53], and use of the anti-metastatic compound α-GalCer can cause side effects affecting the cardiovascular system (see atherosclerosis section). Whether this protection translates to humans is a feat to be accomplished.

iNKT Cells and Autoimmunity

There is an intricate relationship between iNKT cell function and defects in the modulation of autoimmune disease. The majority of the information known about iNKT cell modulation of disease comes from murine models of autoimmune disorders such as: experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), non-obese diabetic mice, graft transplantation rejection model representing human type I diabetes (T1D) and human graft-versus-host disease [73]. A clue to the immunomodulatory ability of iNKT cells came from EAE studies where synthetic analogues of α-GalCer were utilized to treat a peptide-induced model of EAE [74]. In this particular study, a peptide derived from myelin oligodendrocyte was used to induce CNS disease in C57BL/6 mice and iNKT-cell-deficient (Jα281–/–) mice. C57BL/6 mice were protected from EAE by injection of α-GalCer analogues while in iNKT-cell-deficient mice EAE progression was not altered.

Additionally, iNKT cells have been studied in the context of T1D. In studies of monozygotic twins suffering from T1D, lower numbers of iNKT cells and abnormal polarization of Th1 responses have been observed [75]. This phenotype is similar to the non-obese diabetic mouse model [76], where iNKT cell number and function are abnormal, too. Similar to the EAE model, restoration of functional Vα14+ T cells provides protection against T1D progression. These studies indicate that iNKT cells can be modulators of autoimmune pathogenesis by affecting responses mediated by cells of the adaptive immune system. These examples illustrate how iNKT cell function alters progression of autoimmune disease. Although human studies of iNKT cell function in autoimmune diseases are limited in number and quality of controls, the presence of functional iNKT cells in humans makes this cell lineage a great target for therapy to modulate autoimmune disorders.

iNKT Cells in Atherosclerosis

Given that lipid accumulation is a hallmark of atherosclerosis and the fact that iNKT cells are activated by glycolipid antigens, it is not surprising that iNKT cells were hypothesized to play a role in this inflammatory disease. In fact, iNKT cells have been found in human carotid artery plaques, specifically in the shoulder region of these lesions [77], as well as in human atherosclerotic tissue derived from abdominal aortic aneurysms [78]. In addition, several different approaches have been taken to define the role of these unique cells in atherosclerosis using mouse models of the disease.

Given their strong association with decreasing inflammatory response, a reasonable hypothesis would be that iNKT cells are protective against progression of atherosclerosis. However, since 2004, several studies using both CD1d-deficient mice, which lack iNKT cells, have demonstrated that iNKT cells are pro-atherogenic. For example, when CD1d–/– mice were crossed onto the apoE–/– background, atherosclerosis was decreased [7,8,9]. In addition, wild-type CD1d–/– mice fed an atherogenic diet had decreased atherosclerotic lesions [8] compared to controls. It was also shown by our laboratory [7] and others [9] that repeated exogenous activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer (or the related glycolipid OCH [8]) increases atherosclerosis in apoE–/– mice. Reciprocally, using an adoptive transfer model of atherosclerosis in which iNKT cells were transferred to RAG1–/–LDLr–/– mice, VanderLaan et al. [79] demonstrated that iNKT cells are pro-atherogenic in the absence of exogenous stimulation by α-GalCer. Studies in CD1d-deficient mice were further confirmed and refined when Rogers et al. [80] observed that loss of functionally active iNKT cells by using a targeted deletion of the Jα18 gene in LDLr–/– mice reduced the formation of early atherosclerotic lesions. These latter experiments demonstrated that the invariant type I NKT cells and not the type II NKT cells (which have variant but limited TCR usage) were responsible for increasing lesion formation in the mouse models of atherosclerosis.

Interestingly, as with many effects of immunity on atherosclerosis, the effects of iNKT cells appear to be most influential during early lesion progression. This was reported by Aslanian et al. [81] who demonstrated that absence of iNKT cells in LDLr–/– mice leads to decreased early atherosclerosis but did not influence later, more advanced lesions, and that the iNKT cell contribution to lesion progression is transient. More recently, an adoptive transfer study using various subsets of iNKT cells transferred to apoE–/– mice fed high-fat diet showed that CD4+ iNKT cells are the subset responsible for pro-atherogenic activity of iNKT cells [82]. This appeared to be related to the decreased expression of the inhibitory surface receptor Ly49 on CD4+ iNKT cells and the increased ability of CD4+ iNKT cells to secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-2, TNF-α and IFN-γ upon stimulation with α-GalCer. These studies illustrate the complexity of the iNKT cell population and highlight the importance of considering their intricate functions in the design of lipid-mediated therapeutics for human inflammatory diseases.

Although most studies assign a pro-atherogenic role for iNKT cells, one study suggests the opposite effect of iNKT cells and therefore deserves discussion. van Puijvelde et al. [83] observed an atheroprotective role for iNKT cells in one model of atherosclerosis. Specifically, exogenous activation of iNKT cells by α-GalCer injections protected LDLr–/– mice, but not apoE–/– mice, from carotid atherosclerosis. However, in contrast to the previous studies which examined aortic sinus atherosclerotic lesions in response to α-GalCer, this study used a model of carotid atherosclerosis induced by placement of perivascular collars around the carotid arteries. These findings suggest that discrepancies in the roles of iNKT cells in atherosclerosis may be a result of the models used or that iNKT cells play different roles in different anatomic sites of the vasculature. At any rate, these diametrically opposed results indicate that further investigations are needed to fully determine the capabilities of iNKT cells to promote or protect against atherosclerosis in different settings.

Effects of Circulating Lipids on iNKT Cell Function

It is well established that increased lipid accumulation is associated with atherosclerosis in both humans and genetically altered mice. Interestingly, van den Elzen et al. [84] have shown that circulating lipoproteins, such as very low density lipoproteins and, more specifically, those associated with apoE, can enhance iNKT cell responses to glycolipid antigen presented by human dendritic cells. The authors suggest that perhaps lipoprotein-mediated uptake of bacterial lipid antigens, such as those associated with Mycobacterium spp., and the subsequent activation of NKT cells is an important means to enhance immunity. In addition, it has recently been shown that B cells, which can present lipid antigen to iNKT cells, use an apoE-dependent pathway of lipid antigen presentation, and that these APCs are more dependent upon this pathway than dendritic cells [85]. Studies from our laboratory [7] have shown that iNKT cell numbers in the spleen and liver, as well as iNKT-cell-induced IFN-γ production, are decreased in apoE–/– mice in an age-dependent manner, which correlates with increased levels of circulating lipids in these mice. Consistent with these results, B6 mice fed a high-fat diet have suppressed iNKT-cell-derived IFN-γ production in response to α-GalCer [86]. To further demonstrate the importance of lipids in iNKT cell responses, LDLr–/– mice fed Western-type diet accumulate a CD1d-dependent antigen in the serum, and the increased level of this antigen is consistent with the presence of LDL [79]. Collectively, these studies support the relationship between iNKT cells and lipoproteins and substantiate the possible link between infection, immunity and the progression of atherosclerosis.

In summary, iNKT cells are a specialized subset of T cells which recognize glycolipid antigens. These unique cells have been studied for their involvement in several inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Because of their ability to quickly secrete large amounts of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, these cells present an attractive target for potential therapies in human disease. Given that manipulation of iNKT cells has been proposed in human disease therapy, further investigation of how iNKT cells are influenced by their environment and how this might lead to unwanted side effects, such as an increased risk of CVD, could have obvious effects on potential therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

We thank past and present members of our laboratory and all of our colleagues for the wonderful work that is highlighted in this review. Work described in this review that was conducted in our laboratory was supported by NIH grant RO1 HL089667 to A.S.M.

References

- 1.Epstein SE, Zhu J, Burnett MS, Zhou YF, Vercellotti G, Hajjar D. Infection and atherosclerosis: potential roles of pathogen burden and molecular mimicry. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1417–1420. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farrugia PM, Lucariello R, Coppola JT. Human immunodeficiency virus and atherosclerosis. Cardiol Rev. 2009;17:211–215. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181b151a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuura E, Kobayashi K, Lopez LR. Atherosclerosis in autoimmune diseases. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2009;11:61–69. doi: 10.1007/s11926-009-0009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Oosten M, Rensen PC, Van Amersfoort ES, Van Eck M, Van Dam AM, Breve JJ, Vogel T, Panet A, Van Berkel TJ, Kuiper J. Apolipoprotein E protects against bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced lethality. A new therapeutic approach to treat gram-negative sepsis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8820–8824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyka N, Dayer J-M, Modoux C, Kohno T, Edwards CK, Roux-Lombard P, Burger D. Apolipoprotein A-I inhibits the production of interleukin 1b and tumor necrosis factor-α by blocking contact-mediated activation of monocytes by T lymphocytes. Blood. 2001;97:2381–2389. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.8.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimaoka T, Nakayama T, Hieshima K, Kume N, Fukumoto N, Minami M, Hayashida K, Kita T, Yoshie O, Yonehara S. Chemokines generally exhibit scavenger receptor activity through their receptor-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:26807–26810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Major AS, Wilson MT, McCaleb JL, Ru Su Y, Stanic AK, Joyce S, Van Kaer L, Fazio S, Linton MF. Quantitative and qualitative differences in proatherogenic NKT cells in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2351–2357. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000147112.84168.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakai Y, Iwabuchi K, Fujii S, Ishimori N, Dashtsoodol N, Watano K, Mishima T, Iwabuchi C, Tanaka S, Bezbradica JS, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Miyake S, Yamamura T, Kitabatake A, Joyce S, Van Kaer L, Onoe K. Natural killer T cells accelerate atherogenesis in mice. Blood. 2004;104:2051–2059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tupin E, Nicoletti A, Elhage R, Rudling M, Ljunggren HG, Hansson GK, Berne GP. CD1d-dependent activation of NKT cells aggravates atherosclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:417–422. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glass C, Witzaum J. Atherosclerosis. The road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stemme S, Faber B, Holm J, Wiklund O, Witztum JL, Hansson GK. T lymphocytes from human atherosclerotic plaques recognize oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3893–3897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ait-Oufella H, Salomon BL, Potteaux S, Robertson AK, Gourdy P, Zoll J, Merval R, Esposito B, Cohen JL, Fisson S, Flavell RA, Hansson GK, Klatzmann D, Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Natural regulatory T cells control the development of atherosclerosis in mice. Nat Med. 2006;12:178–180. doi: 10.1038/nm1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heller EA, Liu E, Tager AM, Yuan Q, Lin AY, Ahluwalia N, Jones K, Koehn SL, Lok VM, Aikawa E, Moore KJ, Luster AD, Gerszten RE. Chemokine CXCL10 promotes atherogenesis by modulating the local balance of effector and regulatory T cells. Circulation. 2006;113:2301–2312. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.605121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galkina E, Kadl A, Sanders J, Varughese D, Sarembock IJ, Ley K. Lymphocyte recruitment into the aortic wall before and during development of atherosclerosis is partially L-selectin dependent. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1273–1282. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Geest B, Collen D. Antibodies against oxidized LDL for non-invasive diagnosis of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1517–1518. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu JT, Wu LL. Autoantibodies against oxidized LDL. A potential marker for atherosclerosis. Clin Lab Med. 1997;17:595–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinerova A, Racek J, Stozicky F, Zima T, Fialova L, Lapin A. Antibodies against oxidized LDL – theory and clinical use. Physiol Res. 2001;50:131–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paiker JE, Raal FJ, von Arb M. Auto-antibodies against oxidized LDL as a marker of coronary artery disease in patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia. Ann Clin Biochem. 2000;37:174–178. doi: 10.1258/0004563001899177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Binder CJ, Horkko S, Dewan A, Chang MK, Kieu EP, Goodyear CS, Shaw PX, Palinski W, Witztum JL, Silverman GJ. Pneumococcal vaccination decreases atherosclerotic lesion formation: molecular mimicry between Streptococcus pneumoniae and oxidized LDL. Nat Med. 2003;9:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nm876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binder CJ, Hartvigsen K, Chang MK, Miller M, Broide D, Palinski W, Curtiss LK, Corr M, Witztum JL. IL-5 links adaptive and natural immunity specific for epitopes of oxidized LDL and protects from atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:427–437. doi: 10.1172/JCI20479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caligiuri G, Nicoletti A, Poirier B, Hansson GK. Protective immunity against atherosclerosis carried by B cells of hypercholesterolemic mice. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:745–753. doi: 10.1172/JCI07272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palinski W, Miller E, Witztum JL. Immunization of low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-deficient rabbits with homologous malondialdehyde-modified LDL reduces atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:821–825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freigang S, Horkko S, Miller E, Witztum JL, Palinski W. Immunization of LDL receptor-deficient mice with homologous malondialdehyde-modified and native LDL reduces progression of atherosclerosis by mechanisms other than induction of high titers of antibodies to oxidative neoepitopes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1972–1982. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.12.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wick G. Atherosclerosis – an autoimmune disease due to an immune reaction against heat-shock protein 60. Herz. 2000;25:87–90. doi: 10.1007/pl00001957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sherer Y, Tenenbaum A, Praprotnik S, Shemesh J, Blank M, Fisman EZ, Motro M, Shoenfeld Y. Autoantibodies to cardiolipin and beta-2-glycoprotein-I in coronary artery disease patients with and without hypertension. Cardiology. 2002;97:2–5. doi: 10.1159/000047411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.George J, Harats D, Shoenfeld Y. Autoimmunity in atherosclerosis. The role of autoantigens. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2000;18:73–86. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:18:1:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw PX, Horkko S, Chang MK, Curtiss LK, Palinski W, Silverman GJ, Witztum JL. Natural antibodies with the T15 idiotype may act in atherosclerosis, apoptotic clearance, and protective immunity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1731–1740. doi: 10.1172/JCI8472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palinski W, Horkko S, Miller E, Steinbrecher UP, Powell HC, Curtiss LK, Witztum JL. Cloning of monoclonal autoantibodies to epitopes of oxidized lipoproteins from apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Demonstration of epitopes of oxidized low density lipoprotein in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:800–814. doi: 10.1172/JCI118853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasunuma Y, Matsuura E, Makita Z, Katahira T, Nishi S, Koike T. Involvement of beta 2-glycoprotein I and anticardiolipin antibodies in oxidatively modified low-density lipoprotein uptake by macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;107:569–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.d01-948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afek A, George J, Shoenfeld Y, Gilburd B, Levy Y, Shaish A, Keren P, Janackovic Z, Goldberg I, Kopolovic J, Harats D. Enhancement of atherosclerosis in beta-2-glycoprotein I-immunized apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Pathobiology. 1999;67:19–25. doi: 10.1159/000028046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.George J, Afek A, Gilburd B, Blank M, Levy Y, Aron-Maor A, Levkovitz H, Shaish A, Goldberg I, Kopolovic J, Harats D, Shoenfeld Y. Induction of early atherosclerosis in LDL-receptor-deficient mice immunized with β2-glycoprotein I. Circulation. 1998;98:1108–1115. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.11.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Afek A, George J, Gilburd B, Rauova L, Goldberg I, Kopolovic J, Harats D, Shoenfeld Y. Immunization of low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient (LDL-RD) mice with heat shock protein 65 (HSP-65) promotes early atherosclerosis. J Autoimmun. 2000;14:115–121. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1999.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Major AS, Fazio S, Linton MF. B-lymphocyte deficiency increases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1892–1898. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000039169.47943.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersson J, Libby P, Hansson GK. Adaptive immunity and atherosclerosis. Clin Immunol. 2010;134:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Packard RR, Lichtman AH, Libby P. Innate and adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartvigsen K, Chou MY, Hansen LF, Shaw PX, Tsimikas S, Binder CJ, Witztum JL. The role of innate immunity in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(suppl):S388–S393. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800100-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tabas I. Apoptosis and efferocytosis in mouse models of atherosclerosis. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:1288–1296. doi: 10.2174/138945007783220623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doherty TM, Fisher EA, Arditi M. TLR signaling and trapped vascular dendritic cells in the development of atherosclerosis. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:222–227. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monaco C, Gregan SM, Navin TJ, Foxwell BM, Davies AH, Feldmann M. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates inflammation and matrix degradation in human atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;120:2462–2469. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.851881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JG, Lim EJ, Park DW, Lee SH, Kim JR, Baek SH. A combination of Lox-1 and Nox1 regulates TLR9-mediated foam cell formation. Cell Signal. 2008;20:2266–2275. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bendelac A, Rivera MN, Park SH, Roark JH. Mouse CD1-specific NK1 T cells: development, specificity, and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:535–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kronenberg M, Gapin L. The unconventional lifestyle of NKT cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:557–568. doi: 10.1038/nri854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gigli G, Caielli S, Cutuli D, Falcone M. Innate immunity modulates autoimmunity: type 1 interferon-beta treatment in multiple sclerosis promotes growth and function of regulatory invariant natural killer T cells through dendritic cell maturation. Immunology. 2007;122:409–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nowak M, Stein-Streilein J. Invariant NKT cells and tolerance. Int Rev Immunol. 2007;26:95–119. doi: 10.1080/08830180601070195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh AK, Wilson MT, Hong S, Olivares-Villagomez D, Du C, Stanic AK, Joyce S, Sriram S, Koezuka Y, Van Kaer L. Natural killer T cell activation protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2001;194:1801–1811. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.12.1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, Geng YB, Wang CR. CD1-restricted NK T cells protect nonobese diabetic mice from developing diabetes. J Exp Med. 2001;194:313–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oishi Y, Sumida T, Sakamoto A, Kita Y, Kurasawa K, Nawata Y, Takabayashi K, Takahashi H, Yoshida S, Taniguchi M, Saito Y, Iwamoto I. Selective reduction and recovery of invariant Valpha24JalphaQ T cell receptor T cells in correlation with disease activity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morita M, Motoki K, Akimoto K, Natori T, Sakai T, Sawa E, Yamaji K, Koezuka Y, Kobayashi E, Fukushima H. Structure-activity relationship of alpha-galactosylceramides against B16-bearing mice. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2176–2187. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tupin E, Kinjo Y, Kronenberg M. The unique role of natural killer T cells in the response to microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:405–417. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson MT, Singh AK, Van Kaer L. Immunotherapy with ligands of natural killer T cells. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Y, Bao M, Yoon JW. Intrinsic defects in the T-cell lineage results in natural killer T-cell deficiency and the development of diabetes in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Diabetes. 2001;50:2691–2699. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu D, Xing GW, Poles MA, Horowitz A, Kinjo Y, Sullivan B, Bodmer-Narkevitch V, Plettenburg O, Kronenberg M, Tsuji M, Ho DD, Wong CH. Bacterial glycolipids and analogs as antigens for CD1d-restricted NKT cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1351–1356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408696102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Control points in NKT-cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gapin L, Matsuda JL, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. NKT cells derive from double-positive thymocytes that are positively selected by CD1d. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:971–978. doi: 10.1038/ni710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Benlagha K, Kyin T, Beavis A, Teyton L, Bendelac A. A thymic precursor to the NK T cell lineage. Science. 2002;296:553–555. doi: 10.1126/science.1069017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pellicci DG, Hammond KJ, Uldrich AP, Baxter AG, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A natural killer T (NKT) cell developmental pathway involving a thymus-dependent NK1.1(-)CD4(+) CD1d-dependent precursor stage. J Exp Med. 2002;195:835–844. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McNab FW, Pellicci DG, Field K, Besra G, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI, Berzins SP. Peripheral NK1.1 NKT cells are mature and functionally distinct from their thymic counterparts. J Immunol. 2007;179:6630–6637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brossay L, Jullien D, Cardell S, Sydora BC, Burdin N, Modlin RL, Kronenberg M. Mouse CD1 is mainly expressed on hemopoietic-derived cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:1216–1224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kang SJ, Cresswell P. Saposins facilitate CD1d-restricted presentation of an exogenous lipid antigen to T cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:175–181. doi: 10.1038/ni1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou D, Cantu C, 3rd, Sagiv Y, Schrantz N, Kulkarni AB, Qi X, Mahuran DJ, Morales CR, Grabowski GA, Benlagha K, Savage P, Bendelac A, Teyton L. Editing of CD1d-bound lipid antigens by endosomal lipid transfer proteins. Science. 2004;303:523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1092009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zeng Z, Castano AR, Segelke BW, Stura EA, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of mouse CD1: an MHC-like fold with a large hydrophobic binding groove. Science. 1997;277:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Kaer L. NKT cells: T lymphocytes with innate effector functions. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brigl M, Brenner MB: How invariant natural killer T cells respond to infection by recognizing microbial or endogenous lipid antigens. Semin Immunol 2009, E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Kinjo Y, Tupin E, Wu D, Fujio M, Garcia-Navarro R, Benhnia MR, Zajonc DM, Ben-Menachem G, Ainge GD, Painter GF, Khurana A, Hoebe K, Behar SM, Beutler B, Wilson IA, Tsuji M, Sellati TJ, Wong CH, Kronenberg M. Natural killer T cells recognize diacylglycerol antigens from pathogenic bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:978–986. doi: 10.1038/ni1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olson CM, Jr, Bates TC, Izadi H, Radolf JD, Huber SA, Boyson JE, Anguita J. Local production of IFN-gamma by invariant NKT cells modulates acute Lyme carditis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3728–3734. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sriram V, Du W, Gervay-Hague J, Brutkiewicz RR. Cell wall glycosphingolipids of Sphingomonas paucimobilis are CD1d-specific ligands for NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1692–1701. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, Nakagawa R, Sato H, Kondo E, Koseki H, Taniguchi M. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson MT, Singh AK, Van Kaer L. Immunotherapy with ligands of natural killer T cells. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brutkiewicz RR, Sriram V. Natural killer T (NKT) cells and their role in antitumor immunity. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;41:287–298. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brutkiewicz RR. CD1d ligands: the good, the bad, and the ugly. J Immunol. 2006;177:769–775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crowe NY, Smyth MJ, Godfrey DI. A critical role for natural killer T cells in immunosurveillance of methylcholanthrene-induced sarcomas. J Exp Med. 2002;196:119–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chung Y, Qin H, Kang CY, Kim S, Kwak LW, Dong C. An NKT-mediated autologous vaccine generates CD4 T-cell dependent potent antilymphoma immunity. Blood. 2007;110:2013–2019. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Godfrey DI, Kronenberg M. Going both ways: immune regulation via CD1d-dependent NKT cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1379–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI23594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Miyamoto K, Miyake S, Yamamura T. A synthetic glycolipid prevents autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inducing TH2 bias of natural killer T cells. Nature. 2001;413:531–534. doi: 10.1038/35097097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wilson SB, Kent SC, Patton KT, Orban T, Jackson RA, Exley M, Porcelli S, Schatz DA, Atkinson MA, Balk SP, Strominger JL, Hafler DA. Extreme Th1 bias of invariant Vα24JαQ T cells in type 1 diabetes. Nature. 1998;391:177–181. doi: 10.1038/34419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gombert JM, Herbelin A, Tancrede-Bohin E, Dy M, Carnaud C, Bach JF. Early quantitative and functional deficiency of NK1+-like thymocytes in the NOD mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2989–2998. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bobryshev YV, Lord RS. Co-accumulation of dendritic cells and natural killer T cells within rupture-prone regions in human atherosclerotic plaques. J Histochem Cytochem. 2005;53:781–785. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4B6570.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan WL, Pejnovic N, Hamilton H, Liew TV, Popadic D, Poggi A, Khan SM. Atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm and the interaction between autologous human plaque-derived vascular smooth muscle cells, type 1 NKT, and helper T cells. Circ Res. 2005;96:675–683. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000160543.84254.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.VanderLaan PA, Reardon CA, Sagiv Y, Blachowicz L, Lukens J, Nissenbaum M, Wang CR, Getz GS. Characterization of the natural killer T-cell response in an adoptive transfer model of atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1100–1107. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rogers L, Burchat S, Gage J, Hasu M, Thabet M, Willcox L, Ramsamy TA, Whitman SC. Deficiency of invariant V alpha 14 natural killer T cells decreases atherosclerosis in LDL receptor null mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;78:167–174. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aslanian AM, Chapman HA, Charo IF. Transient role for CD1d-restricted natural killer T Cells in the formation of atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:628–632. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000153046.59370.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.To K, Agrotis A, Besra G, Bobik A, Toh BH. NKT cell subsets mediate differential proatherogenic effects in ApoE–/– mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:671–677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.van Puijvelde GH, van Wanrooij EJ, Hauer AD, de Vos P, van Berkel TJ, Kuiper J. Effect of natural killer T cell activation on the initiation of atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2009;102:223–230. doi: 10.1160/TH09-01-0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.van den Elzen P, Garg S, Leon L, Brigl M, Leadbetter EA, Gumperz JE, Dascher CC, Cheng TY, Sacks FM, Illarionov PA, Besra GS, Kent SC, Moody DB, Brenner MB. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 2005;437:906–910. doi: 10.1038/nature04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Allan LL, Hoefl K, Zheng DJ, Chung BK, Kozak FK, Tan R, van den Elzen P. Apolipoprotein-mediated lipid antigen presentation in B cells provides a pathway for innate help by NKT cells. Blood. 2009;114:2411–2416. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-211417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Miyazaki Y, Iwabuchi K, Iwata D, Miyazaki A, Kon Y, Niino M, Kikuchi S, Yanagawa Y, Kaer LV, Sasaki H, Onoe K. Effect of high fat diet on NKT cell function and NKT cell-mediated regulation of Th1 responses. Scand J Immunol. 2008;67:230–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]