Abstract

Proper chromosome congression (the process of aligning chromosomes on the spindle) contributes to accurate and faithful chromosome segregation. It is widely accepted that congression requires ‘K-fibres’, microtubule bundles that extend from the kinetochores to spindle poles1, 2. Here we demonstrate that chromosomes in human cells co-depleted for HSET (kinesin-14)3, 4 and hNuf2 (a component of the Ndc80/Hec1 complex)5 can congress to the metaphase plate in the absence of K-fibres. However, the chromosomes were not stably maintained at the metaphase plate under these conditions. Chromosome congression in HSET+hNuf2 co-depleted cells required the plus-end directed motor CENP-E (kinesin-7)6, which has been implicated in the gliding of mono-oriented kinetochores alongside adjacent K-fibres7. Thus, proper end-on attachment of kinetochores to microtubules is not necessary for chromosome congression. Instead, our data support the idea that congression allows unattached chromosomes to move to the middle of the spindle where they have a higher probability of establishing connections with both spindle poles. These bi-oriented connections are also utilized to maintain stable chromosome alignment at the spindle equator.

Keywords: Chromosome congression, Kinetochore, K-fibre, Kinesin-14, hNuf2, HSET, CENP-E

Assembly of a functional mitotic spindle involves the process of ‘chromosome congression’, which positions all chromosomes in the equatorial plane of the spindle. Congression is evolutionary conserved and enhances the fidelity of chromosome segregation8. Despite its importance, the molecular mechanisms that govern chromosome congression remain poorly understood. In the classic view, chromosomes move toward the spindle equator as a result of their ‘bi-orientation’ the process in which chromosomes establish connections with both spindle poles9. In this scenario, congression requires ‘kinetochore fibres’ (K-fibres), bundles of MTs that attach to the kinetochore of a chromosome in an end-on manner1, 2, 10. However, chromosome congression is also driven by gliding of kinetochores alongside K-fibers of other already bi-oriented chromosomes, a process dependent on the plus-end directed MT motor CENP-E and that does not require establishing end-on kinetochore attachments to K-fibres7. It is not clear which of the two congression mechanisms is utilised by the majority of chromosomes in a typical mammalian cell.

We sought to address the question of whether chromosomes can congress efficiently under conditions that make proper end-on kinetochore attachment and formation of K-fibres impossible. Perturbation of the Ndc80/Hec1 complex, which is essential for MT-kinetochore attachment, severely disrupts K-fibre formation and chromosome alignment5, 11. However, chromosomes are still capable of movements presumably via lateral interactions between kinetochores and MTs11. This prompted us to seek a condition in which we could restore efficient chromosome congression in the absence of end-on chromosome attachments.

To disrupt the Ndc80/Hec1 complex we used siRNA against the Ndc80 component hNuf211. As expected, depletion of hNuf2 disrupted K-fibres and caused a significant increase in the percentage of cells with severely misaligned chromosomes (Fig. 1a, b)5. We rationalised that forces driving chromosome congression are antagonised by minus-end directed MT motors that produce poleward directed forces. In the absence of K-fibres contributions of these minus-end directed forces might become overwhelming and cause chromosome scattering. Therefore we tested if inactivation of the human kinesin-14 (HSET) and cytoplasmic dynein, the two major minus-end directed MT motors involved in spindle function2, 12, 13, restores proper chromosome alignment in Nuf2-depleted cells.

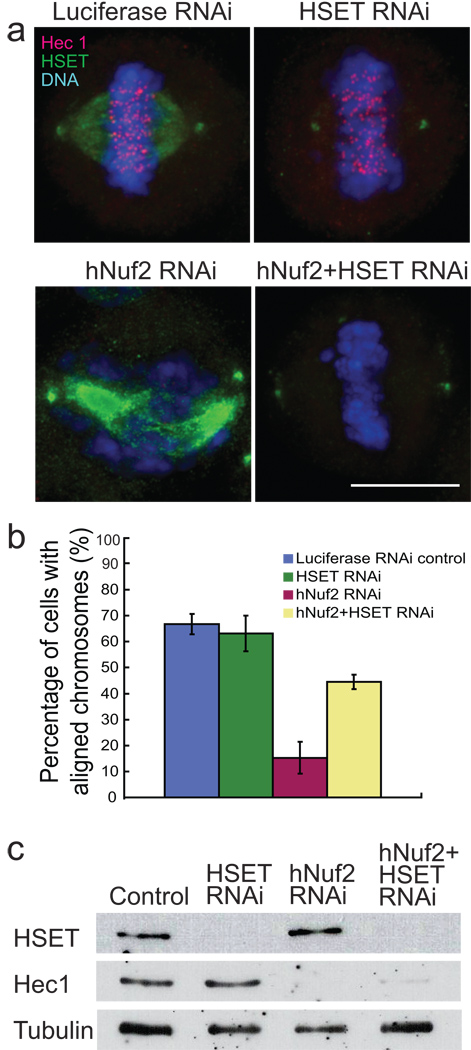

Figure 1. Chromosomes can align in cells lacking K-fibres.

(a) HeLa cells transfected with luciferase control RNAi oligo (Control), hNuf2 RNAi oligo, or hNuf2+HSET RNAi oligo and stained to visualise HSET (green) Hec1 (red), and DNA (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) The average percentage of prometaphase and metaphase cells with aligned chromosomes is graphed ± s.d. from three independent experiments where ~100 mitotic cells were scored per experiment. The differences between all the pairs are significant (p<0.05) (c) Western blot analysis of samples from each knockdown probed with antibodies to HSET, Hec1, and tubulin.

The frequency of cells with aligned chromosomes was significantly higher upon co-depletion of hNuf2 and HSET than upon depletion of hNuf2 alone (Fig. 1a, b), although not as high as in control cells. This result was observed with multiple HSET RNAi oligos (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1a, b). Western analysis showed that the Hec1 component of the Ndc80 complex and HSET were both efficiently knocked down in our experiments (Fig. 1c). Perturbation of kinetochore-bound dynein by knockdown of the dynein-targeting protein zw1014 also partially restored chromosome alignment in hNuf2 knockdown cells, although this treatment was much less efficient than HSET knockdown (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S1c, d).

We next tested whether restoration of chromosome alignment observed in the hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells was due to regeneration of the K-fibres. It has been reported that the number of MTs in the K-fibre is correlated with the amount of residual Ndc80 complex present on the kinetochore11. We quantified the amount of Hec1 that remained on kinetochores after knockdown using immunofluorescence11 and found that Hec1 levels at kinetochores were similar in hNuf2 RNAi cells and in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2a), suggesting that any residual kinetochore remnants that could mediate transient MT attachments were similar in hNuf2 RNAi and in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells despite the dramatically different levels of chromosome alignment. As an alternative means to assess the presence of K-fibre MTs we examined the localisation of the protein HURP, which is normally enriched toward the plus-ends of MTs in K-fibres15, 16. In control cells HURP was localised on the K-fibres, whereas in hNuf2 and hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells, HURP staining was diminished (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2b). These data suggest that K-fibres are not restored upon simultaneous knockdown of HSET and hNuf2.

As proper end-on amphitelic attachments of MTs are required for generating tension across the centromere, we compared inter-kinetochore distances between K-fibre intact (control) and K-fibre deficient (hNuf2+HSET RNAi) cells (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2c–e). These analyses were conducted in a HeLa cell line expressing GFP-CENP-A to mark kinetochores and γTubulin-GFP to mark centrosomes. During the pseudo-metaphase state, inter-kinetochore distances in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells were on average 40% lower than in control cells (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2d). These results are consistent with previous reports for cells depleted of hNuf25 and similar to cells treated with the MT depolymerising drug nocodazole and reveal that the centromeres in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells are not under tension. Further, live-cell analyses of individual kinetochore pairs revealed that the inter-kinetochore distance in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells (8 out of 10 cells) remained nearly constant over time while in control cells the distance between sister kinetochores exhibited periodic fluctuations (4 out of 4 cells) (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S2e, Video 1). This result was consistent with the more narrow distribution range of inter-kinetochore distances in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells versus control cells (Fig. S2d).

Similar to previous reports we also found that kinetochores in hNuf2 RNAi cells exhibited brief erratic movements11. These movements persisted in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2f–h). Together our results strongly support the idea that chromosomes in hNuf2+HSET RNAi fail to establish amphitelic attachments necessary to generate centromere tension.

To reveal the nature of interaction between chromosomes and MTs in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells we used CaCl2 to depolymerise highly dynamic MTs so that stable MTs of the spindle could be clearly observed. In both control and HSET RNAi cells, all aligned chromosomes established amphitelic attachments with K-fibres extending from each sister kinetochore towards the corresponding spindle pole (Fig. 2a, b). In contrast, in both hNuf2 and hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells most of the kinetochores were laterally associated with MT bundles that traversed the centre of the spindle (Fig.2c,d). We occasionally detected kinetochores in control cells that were not only connected to the K-fibres, but also laterally bound to continuous MT bundles extending from each half spindle through the spindle midzone (Fig. 2a, arrowhead), suggesting that these bundles are likely also present in control cells. In contrast, in hNuf2 and hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells, these bundles were prominently visible while MT bundles that terminated at the kinetochore were rarely detected.

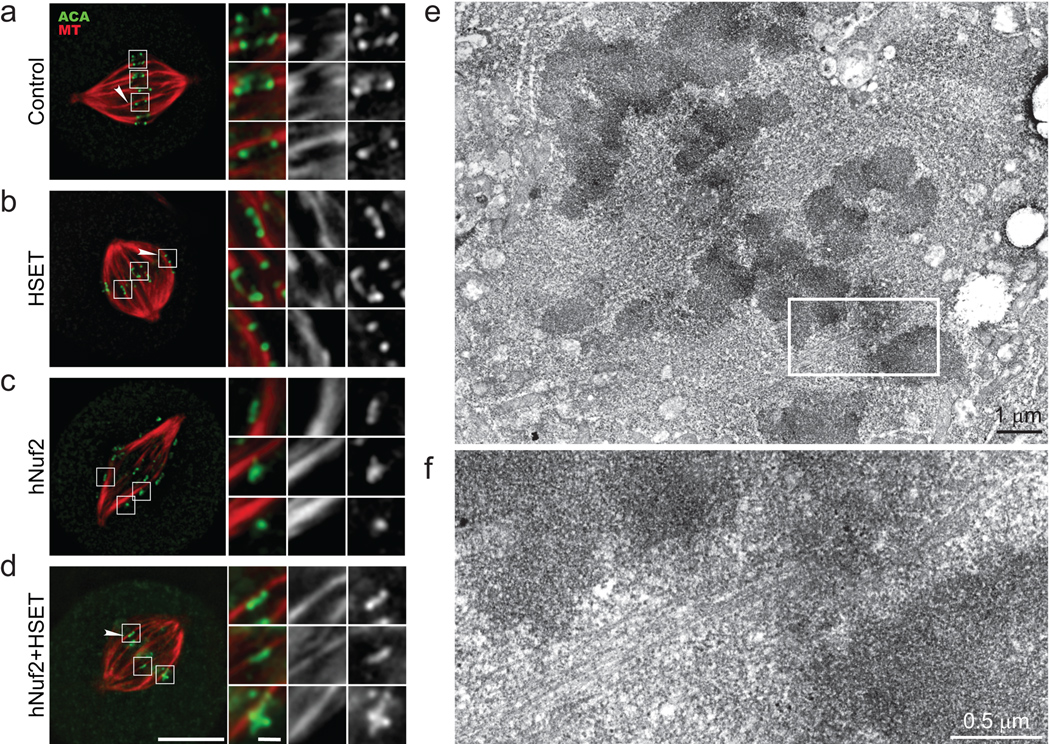

Figure 2. Kinetochores laterally bind stabilised MT bundles in the absence of K-fibres.

HeLa cells in control (a), HSET (b), hNuf2 (c), or hNuf2+HSET (d) RNAi were treated with 0.2 mM CaCl2 to depolymerise highly dynamic MTs and stained to visualise MTs (red), kinetochores (ACA, green) and DNA (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm for whole spindle images (left) or 1 µm for insets (right). Arrowheads indicate a MT bundle that transverses the spindle equator without making an end-on attachment to a kinetochore. (e) Correlative light/serial section EM was performed in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells. Low magnification view of a cell showing the spindle equator region. (f) Higher magnification view of the region boxed in panel (e). Notice a bundle of microtubules bypassing kinetochores.

To gain more insight into the interaction of chromosomes with MTs, we performed serial-section electron microscopy on hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells (Fig. 2e, f). Cells were first followed by time-lapse light-microscopy to monitor chromosome alignment, and then fixed and embedded for EM analyses (see Supplementary Information Fig. S3). Consistent with published data on Nuf2-depleted cells11, EM revealed no typical tri-laminar kinetochores in any of the >100 sections analysed in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells. We occasionally observed MT bundles traversing the central part of the spindle and laterally associated with chromosomes (Fig. 2e, f). However we never found evidence of MT bundles terminating at the chromosomes.

During classic congression chromosomes exhibit extended linear motion from the vicinity of the spindle pole toward the equator7, 17. To examine whether this characteristic movement was preserved in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells, we employed time-lapse imaging in HeLa cells triple-labelled for kinetochores (GFP-CENP-A), centrosomes (γTubulin-GFP), and chromosomes (mCherry-H2B). Cells were imaged at 30 s intervals on a spinning disk confocal microscope from prophase until telophase (Fig. 3). Of the 21 hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells imaged, 11 cells aligned their chromosomes, consistent with the frequency of chromosome alignment in our in fixed–cell analyses (Fig. 1b). Although sustained velocities of individual chromosome movements were similar between control and hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells (1.5 ± 0.5 µm/min, n = 6 and 1.6 ± 0.3 µm/min, n = 6 respectively; see also Supplementary Information Fig. S4), overall formation of the metaphase plate took significantly longer in cells co-depleted of hNuf2 and HSET. Furthermore, only 2 of the hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells exited mitosis during our imaging period of ~2 hr. In contrast, all control cells (n=9) progressed through mitosis with normal timing, similar to previous reports16, 18 (see Supplementary Information, Video 2). Thus, our imaging conditions did not impede normal mitotic progression. These results show that while chromosomes maintain the ability to congress when K-fibres are severely disrupted, the efficiency of the congression process is reduced.

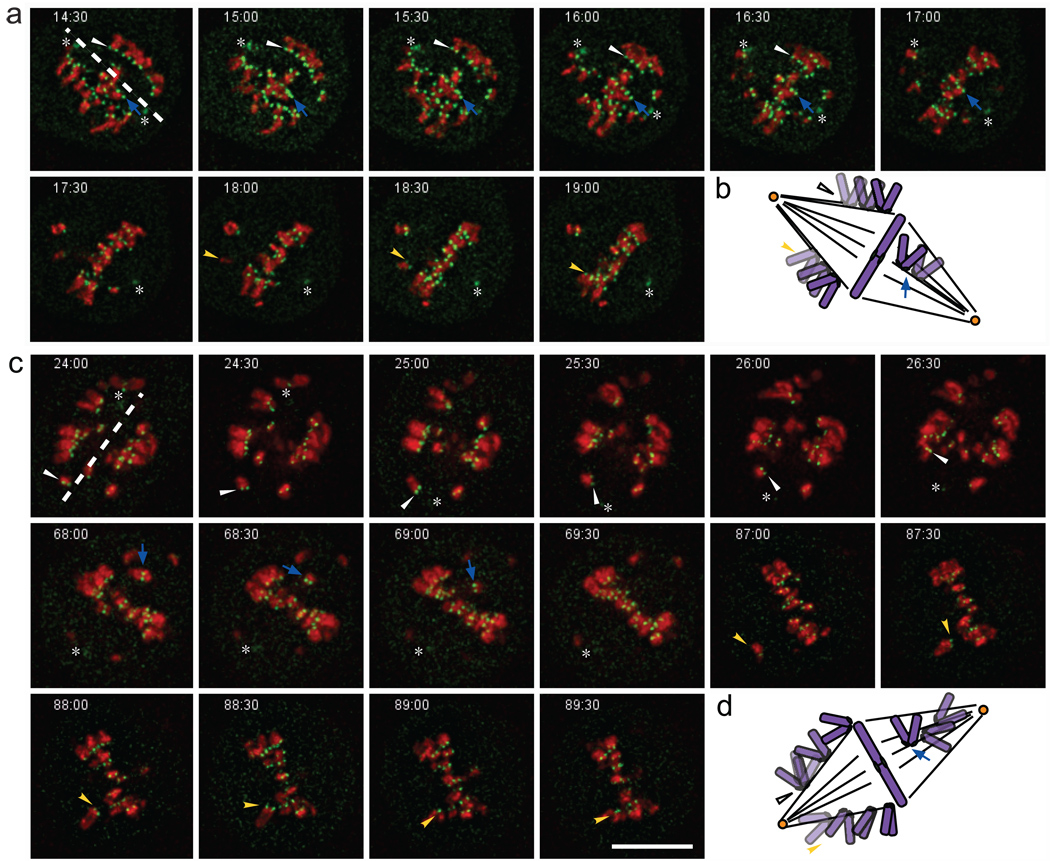

Figure 3. In the absence of K-fibres, kinetochores congress with alternating kinetochores leading.

Triple labelled HeLa cells (GFP-CENP-A, GFP-gamma-tubulin, and mcherry-H2B) treated with control luciferase (a) or hNuf2+HSET (c) RNAi were imaged at 30 s interval from nuclear envelope breakdown until telophase and analysed for kinetochore orientation during congression. The time stamp is marked in the upper left of each panel, asterisks mark the position of spindle poles, and the coloured arrowheads mark individual kinetochore pairs schematised in (b) and (d). Scale bar, 10 µm. Note that the arrow heads that reflect the orientation of the kinetochore pairs in the control cells do not change much over time, whereas the arrow heads in the hNuf2+HSET RNAi cell change orientation dramatically with time.

Analysis of individual chromosome movements revealed characteristic differences between chromosome congression in control versus hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells. In control cells one of the sister kinetochores continuously lead the way during congression, and the orientation of the sister kinetochores with respect to the spindle axis remained constant. (Fig. 3a, b; Supplementary Information, Video S2). In contrast, sister kinetochores tumbled frequently during congression in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells. It was not unusual for sister kinetochores to transiently orientate perpendicular to the spindle axis (Fig. 3c, d, and Supplementary Information, Video 2). This behaviour suggests that in the absence of end-on attachments congressing kinetochores do not maintain stable association with MTs. Instead, congression in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells is driven by both sister kinetochores that intermittently switch between leading and trailing positions. Overall, these findings strongly support a model in which chromosome congression occurs by gliding of unattached kinetochores alongside of MT bundles7. Because this type of congression has been reported to require activity of the plus-end kinesin CENP-E7 we sought to investigate whether this protein is required for chromosome alignment in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells.

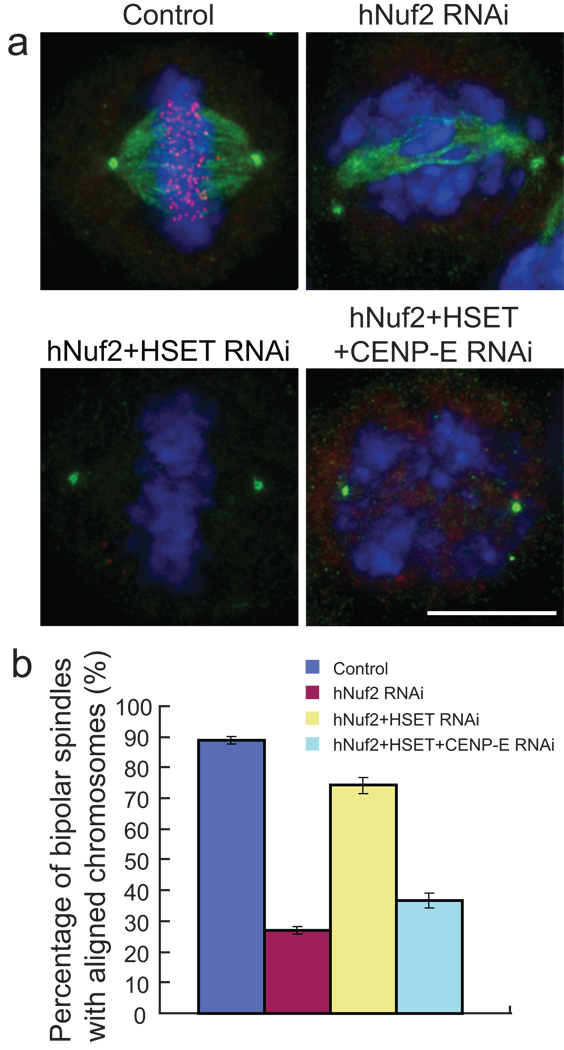

Immunofluorescence analysis of CENP-E showed that neither hNuf2 RNAi nor hNuf2+HSET RNAi affected CENP-E localisation to kinetochores (see Supplementary Information, Fig. S5a, b). Depletion of CENP-E in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells caused a decrease in the percentage of cells with aligned chromosomes down to the levels found in cells depleted for only hNuf2 (Fig. 4b). This result strongly suggests that congression in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells is driven by the activity of CENP-E.

Figure 4. Chromosome congression in cells with disrupted K-fibres is dependent on CENP-E.

(a) Cells in which hNuf2, HSET, and CENP-E were knocked down were stained to visualize HSET (green), Hec1 (red) and DNA (blue). Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) Quantification of the percentage of bipolar spindles with aligned chromosomes from the four different RNAi conditions. The mean percentages of spindles ± s.d. were graphed for each condition. Three independent experiments and approximately 300 total cells were scored per RNAi condition. The differences between the mean percentages of control versus hNuf2 RNAi, hNuf2 RNAi versus hNuf2+HSET RNAi and hNuf2+HSET versus hNuf2+HSET+CENP-E RNAi are all significant (p<0.05). The difference between hNuf2 RNAi and hNuf2+HSET+CENP-E RNAi is not significant (p=0.45).

Our findings that chromosome congression occurs in the absence of end-on attachments of kinetochores to K-fibres led us to speculate that the forces that drive chromosome congression may be distinct from those that maintain chromosomes at the metaphase plate. To test this idea, we compared post-congression behaviour of chromosomes in control and in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells. Unlike in control cells, chromosomes in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells were not stably maintained at the metaphase plate but exhibited periodic fast movements towards one of the spindle poles followed by a slower return to the spindle equator (Fig. 5ab; Supplementary Information, Video 3–4). The speed of the poleward excursions (~10 µm/min) was reminiscent of the rapid poleward movement of chromosomes observed during the capture of astral MTs19. It is noteworthy that fast dynein-dependent chromosome movements have been previously reported in cells with a disrupted Ndc80 complex20. To address whether the post-congression poleward excursions were also dynein-dependent, we knocked down zw10 in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells and then followed the behaviour of chromosomes near the metaphase plate. Whereas 77% of the hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells exhibited rapid poleward excursions (23 out of 30 cells) this type of movement was observed in only 36% of the cells in the hNuf2+ HSET+zw10 triple knockdown cells (13 cells out of 36). This difference suggests that dynein drives movement of chromosomes off the metaphase plate.

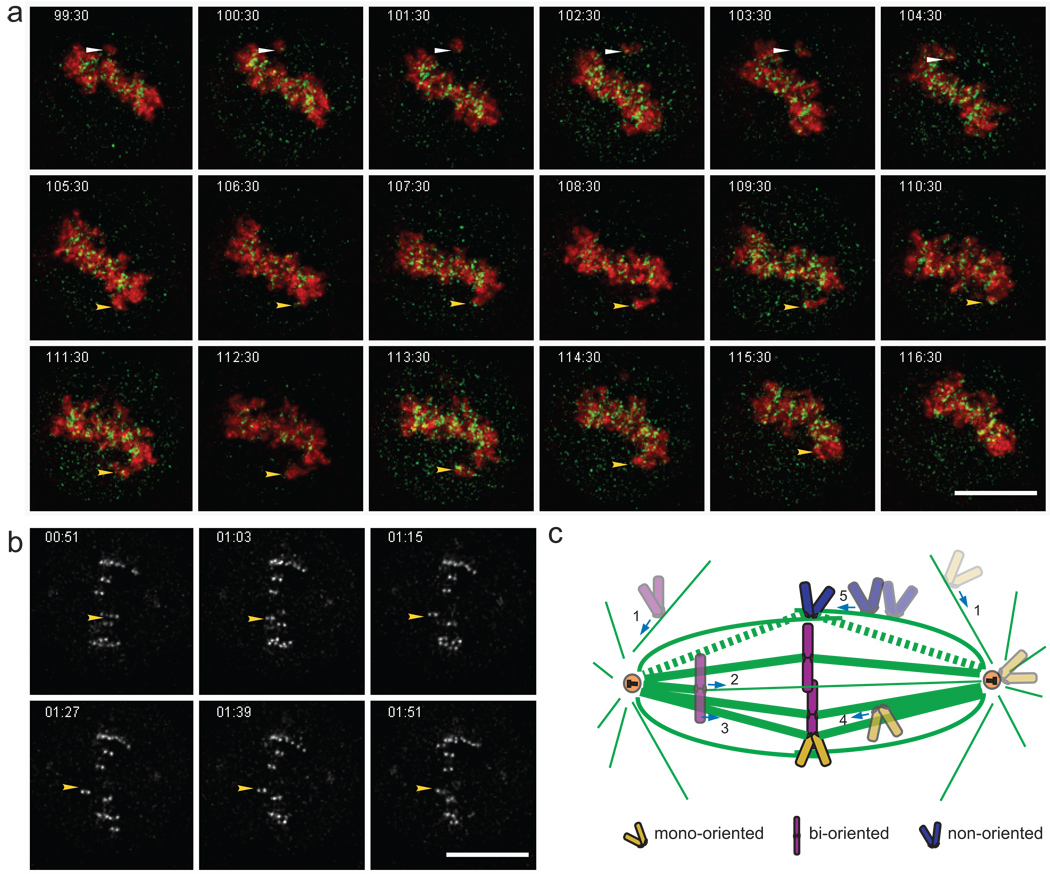

Figure 5. K-fibres are needed to maintain chromosome alignment.

(a) Triple labelled HeLa cells were analysed for chromosome movement at 30 s intervals after congression in hNuf2+HSET double RNAi cells. The timestamp is shown in the upper left panel of each panel, and white and yellow arrowheads point to two distinct unstable chromosomes that move off the metaphase plate and then congress back to the metaphase plate. (b) Kinetochore movements were tracked in cells with disrupted K-fibres at 3 s intervals during congression in hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells. The yellow arrowhead corresponds to a chromosome that displays a rapid movement away from and back toward the metaphase plate. (c) Model diagramming the different pathways by which chromosomes congress to the metaphase plate. Chromosome 1 (purple) exhibits rapid lateral movement toward the spindle pole and then becomes bi-oriented and congresses through activities at its kinetochore (2) or its chromosome arms (3). Alternatively, chromosome 1 (light yellow) can congress via the mono-oriented pathway (4). Our data suggest that chromosomes (blue) do not need to be specifically oriented but are still able to congress on any stabilised MT bundle (5).

From the standpoint of the classic ‘search-and-capture’ hypothesis21 attachment of sister kinetochores to the spindle occurs independently. This results in chromosome mono-orientation – movement of the chromosome towards one spindle pole (Fig. 5c). There the chromosome remains until its sister kinetochore captures MTs that emanate from the distal spindle pole. Only then will the chromosome congress and become stably positioned near the spindle equator. A conceptual difficulty with this mechanism is that the probability of capturing MTs that emanate from the centrosome decreases dramatically as the distance between the centrosome and the kinetochore increases22. Our data provide an explanation for how cells can overcome this difficulty by revealing that chromosomes have the ability to congress to the spindle equator in the absence of end-on MT attachments. We favour the idea that congression is not a consequence of chromosome bi-orientation but rather is a means to maximize the efficiency of kinetochore attachment by bringing the chromosome to the area with the highest concentration of MT plus ends. Although congression of unattached kinetochores alongside the K-fibre of another chromosome has been previously observed4 our data reveal for the first time that this mechanism is sufficient to achieve congression of all chromosomes in human cells in a reasonable timeframe. Further, we demonstrate that congression via CENP-E mediated kinetochore gliding can occur along any MT bundle and does not require the trailing kinetochore to be attached (Fig. 5c).

In the normal situation only a limited number of chromosomes appear to exhibit mono-orientation and congression via MT gliding6, 7, 23. This is likely because there are multiple pathways that act to achieve chromosome congression. In the presence of K-fibres mono-oriented chromosomes have a large number of adjacent K-fibres available to glide on. However, the search-and-capture hypothesis predicts that almost all chromosomes must transiently become bi-oriented, and live-cell microscopy reveals that the majority of chromosomes rapidly achieve stable bi-orientation during normal mitosis. Our data suggest that the fast bi-orientation can be achieved because unattached chromosomes are positioned near the spindle equator via CENP-E-mediated forces. Accordingly, the number of mono-oriented chromosomes increases in cells upon inhibition of CENP-E7, 23–25.

An intriguing question is why CENP-E-mediated forces fail to support chromosome congression in cells with disrupted Ndc80/HEC-1 and normal HSET activity. One possibility is that HSET provides a pole-directed force that antagonizes the activity of CENP-E. This pole-directed force would need to be indirect because we find no evidence of HSET association with chromosome arms or with kinetochores. Another possibility is that chromosome congression requires stabilised MT bundles, and thus mechanisms governing MT stability are critical to the congression process. In this light, we found that HSET plays an important role in spindle assembly via its MT cross-linking activity3, 4. We propose that inactivation of HSET results in an increase in the number of stabilised MT bundles in the central spindle. These bundles would provide the tracks for congressing chromosomes that glide in a Cenp-E mediated manner, and indicate that CENP-E may play a more active role in chromosome congression than previously thought.

METHODS

RNAi

HeLa cells at 4 × 104 cells/well were plated into each well of a 6-well culture dish, arrested with 2 mM thymidine for 20 h and then released into fresh media. Two h after release from the thymidine block, 200 nM luciferase RNAi negative control #2 oligo (Dharmacon, Chicago, IL) 200 nM HSET RNAi oligo to the coding region (UCA GAA GCA GCC CUG UCA A), 300 nM HSET 3’UTR-1 RNAi oligo (GUG UCC CUA UGU CUA UGU A), 200 nM HSET 3’UTR-2 RNAi oligo (CAU GUC CCA GGG CUA UCA AAU), 200 nM hNuf2 RNAi oligo3, or 200 nM zw10 RNAi oligo26 were transfected into HeLa cells using oligofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). When comparing knockdown of multiple proteins, an equivalent amount of luciferase negative control oligo was co-transfected with the specific oligo such that the total amount of oligo transfected was identical for each well. At 24 h after transfection, cells were blocked with 2 mM thymidine for 19 h to synchronize the cells and then released for 11~12 h to allow cells to progress to late G2. The cells were then processed for immunofluorescence or for western blot analysis. For time-lapse imaging of living cells, we used the same protocol except that cells were plated onto 22×22 mm coverslips in 60 mm dishes. For the CENP-E knockdown assays, 200 nM CENP-E RNAi oligo7 was transfected into HeLa cells 24 h after HSET and hNuf2 RNAi transfection and then cells were processed for immunofluorescence after an additional 24 h.

Electron Microscopy

GFP-CENP-A/GFP-γ-tubulin/mcherry-H2B HeLa cells were grown on EM grade gridded coverslips and then transfected with hNuf2+HSET siRNAs as described above. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were imaged on a Nikon spinning disk confocal microscope to monitor kinetochore movement. Mitotic cells exhibiting clear phenotype (aligned chromosomes but shortened inter-kinetochore distances, kinetochore orientation changes, and rapid movement towards spindle poles) were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in PBS (137mM NaCl, 2.7mM KCl, 10mM Na2HPO4, 2mM KH2PO4. pH 7.2) for 30 min, post-fixed in 1% OsO4 by standard protocols27. Cells of interest were re-located on the gridded coverslips and then serially sectioned (100-nm thickness). Images were collected on a Zeiss 910 microscope operated at 100 KV.

Imaging and data analysis

Fixed cells were imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 90i equipped with a 100× Apochromatic PLAN objective (NA 1.4) and a CoolSnap HQ CCD camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). The camera and filters were controlled by Metamorph (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Image stacks were collected at 0.5 µm steps through the whole cell volume and then deconvolved using Autodeblur (Autoquant Imaging, Bethesda, MD) for 10–20 iterations. For time-lapse imaging of living cells, RNAi treated HeLa cells were blocked at G1/S with thymidine as described above and then released into fresh Opti-MEM. 11–12 h after release, coverslips were placed into a Rose chamber with imaging medium (Opti-MEM, 20 mM Hepes pH 7.7, 30 units/ml Oxyrase) and covered with mineral oil. Cells were imaged at 37°C on a Yokagawa spinning disk CSU-10 mounted on a Nikon TE2000 microscope equipped with a 100× objective (Apochromatic PLAN, NA1.4). Images were captured on a Roper Cascade II EM-CCD camera set at 3700 gain with 100 ms exposures for each channel at three Z-axis sections of 0.5 µm. For experiments analysing mitotic progression, we used 30 s time intervals for approximately 2 h total imaging time. For experiments to measure kinetochore motility, we captured images from three focal planes at 3–5 s intervals for a total of 5 min.

To determine the percentage of cells with aligned or unaligned chromosomes, fixed cells were counted at 54 h post-transfection. The average percentage of cells with aligned or unaligned chromosomes was determined from three independent experiments with the HSET cDNA oligo in which 100 mitotic cells were counted per experiment. A cell was scored as having unaligned chromosomes when the majority of chromosomes were scattered throughout the spindle region. A cell was scored as having aligned chromosomes if the majority of chromosomes were tightly aligned at the metaphase plate. In addition, three independent experiments were performed for each of the two 3’UTR oligos. For each experiment, the average percentage of cells is graphed as the mean ± sd for n = 3 experiments.

The oscillatory behaviour of kinetochores and the inter-kinetochore distances were determined from transfection of the GFP-CENP-A/ gamma-tubulin-GFP HeLa cell line with luciferase control oligo or the hNuf2 and HSET oligos. For each movie, a randomly selected frame was analysed for the inter-kinetochore distance. A total of 27 kinetochores from four control cells and 54 kinetochores from eight hNuf2+HSET RNAi cells were measured. The average distance ± the s.d. is reported. To analyse the oscillation patterns, we tracked a single kinetochore pair over a defined period of time and plotted the inter-kinetochore distance versus time. The erratic kinetochore motility was manually tracked by identifying the center of GFP-CENP-A dots using Image J as described previously11. The positional data of the kinetochore at each time point were plotted with Excel. The kymographs that represent chromosome motility during congression were assembled frame by frame from the movies of mitotic progression (30 s time interval) by drawing a rectangular box along their movement trajectory toward the metaphase plate.

Two-tailed Student’s t-tests were performed where indicated in the text using Excel. Significance was considered when the p value was < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephanie Ems-McClung and Jim Powers for discussion of findings and critical comments on the manuscript. We thank Guowei Fang for HURP antibodies, Duane Compton for HSET constructs, Beth Sullivan for the GFP-CENP A construct, and Bruce Schaar for CENP-E antibody. SC is grateful to members of the MBL Physiology course for instruction in imaging and many thoughtful discussions. The IUB Light Microscopy Imaging Center and Wadsworth Center's EM Core facility provided microscopy resources. This work was supported by NIH grants GM59618 (CEW) and GM59363 (AK). CBO is supported by a Kirschstein-NRSA post-doctoral fellowship (GM077911).

Footnotes

Author contributions. SC performed most of the experiments, analysed the data and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. CO performed EM analyses. CEW and AK in conjunction with SC and CO designed the experiments, interpreted the data, edited the manuscript, and prepared the final data for publication.

References

- 1.Maiato H, DeLuca J, Salmon ED, Earnshaw WC. The dynamic kinetochore-microtubule interface. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:5461–5477. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walczak CE, Heald R. Mechanisms of mitotic spindle assembly and function. Int. Re.v Cytol. 2008;265:111–158. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)65003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai S, Weaver LN, Ems-McClung SC, Walczak CE. Kinesin-14 family proteins HSET/XCTK2 control spindle length by cross-linking and sliding microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2009;20:1348–1359. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-09-0971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manning AL, Compton DA. Mechanisms of spindle-pole organization are influenced by kinetochore activity in mammalian cells. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeLuca JG, Moree B, Hickey JM, Kilmartin JV, Salmon ED. hNuf2 inhibition blocks stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment and induces mitotic cell death in HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159:549–555. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood KW, Sakowicz R, Goldstein LS, Cleveland DW. CENP-E is a plus end-directed kinetochore motor required for metaphase chromosome alignment. Cell. 1997;91:357–366. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor TM, et al. Chromosomes can congress to the metaphase plate before biorientation. Science. 2006;311:388–391. doi: 10.1126/science.1122142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicklas RB, Arana P. Evolution and the meaning of metaphase. J Cell Sci. 1992;102(Pt 4):681–690. doi: 10.1242/jcs.102.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rieder CL, Salmon ED. The vertebrate cell kinetochore and its roles during mitosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:310–318. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01299-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maiato H, Sunkel CE. Kinetochore-microtubule interactions during cell division. Chromosome Res. 2004;12:585–597. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000036587.26566.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeLuca JG, et al. Hec1 and nuf2 are core components of the kinetochore outer plate essential for organizing microtubule attachment sites. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:519–531. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heald R, Walczak CE. Mitotic Spindle Assembly Mechanisms. In: De Wulf P, Earnshaw WC, editors. The Kinetochore: From Molecular Discoveries to Cancer Therapy. New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; 2009. pp. 231–268. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholey JM, Brust-Mascher I, Mogilner A. Cell division. Nature. 2003;422:746–752. doi: 10.1038/nature01599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Starr DA, Williams BC, Hays TS, Goldberg ML. ZW10 helps recruit dynactin and dynein to the kinetochore. J. Cell Biol. 1998;142:763–774. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.3.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sillje HH, Nagel S, Korner R, Nigg EA. HURP is a Ran-importin beta-regulated protein that stabilizes kinetochore microtubules in the vicinity of chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong J, Fang G. HURP controls spindle dynamics to promote proper interkinetochore tension and efficient kinetochore capture. J. Cell Biol. 2006;173:879–891. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skibbens RV, Skeen VP, Salmon ED. Directional instability of kinetochore motility during chromosome congression and segregation in mitotic newt lung cells: a push-pull mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:859–875. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bomont P, Maddox P, Shah JV, Desai AB, Cleveland DW. Unstable microtubule capture at kinetochores depleted of the centromere-associated protein CENP-F. EMBO J. 2005;24:3927–3939. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rieder CL, Alexander SP. Kinetochores are transported poleward along a single astral microtubule during chromosome attachment to the spindle in newt lung cells. J. Cell Biol. 1990;110:81–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.1.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vorozhko VV, Emanuele MJ, Kallio MJ, Stukenberg PT, Gorbsky GJ. Multiple mechanisms of chromosome movement in vertebrate cells mediated through the Ndc80 complex and dynein/dynactin. Chromosoma. 2008;117:169–179. doi: 10.1007/s00412-007-0135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirschner MW, Mitchison T. Microtubule dynamics. Nature. 1986;324:621. doi: 10.1038/324621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wollman R, et al. Efficient chromosome capture requires a bias in the 'search-and-capture' process during mitotic-spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 2005;15:828–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McEwen BF, et al. CENP-E is essential for reliable bioriented spindle attachment, but chromosome alignment can be achieved via redundant mechanisms in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:2776–2789. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.9.2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putkey FR, et al. Unstable kinetochore-microtubule capture and chromosomal instability following deletion of CENP-E. Dev. Cell. 2002;3:351–365. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver BA, et al. Centromere-associated protein-E is essential for the mammalian mitotic checkpoint to prevent aneuploidy due to single chromosome loss. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:551–563. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang Z, Tulu US, Wadsworth P, Rieder CL. Kinetochore dynein is required for chromosome motion and congression independent of the spindle checkpoint. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:973–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.04.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rieder CL, Cassels G. Correlative light and electron microscopy of mitotic cells in monolayer cultures. Methods Cell Biol. 1999;61:297–315. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)61987-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.