Abstract

Background

Awareness of the relative high rate of adverse events in laparoscopic surgery created a need to safeguard quality and safety of performance better. Technological innovations, such as integrated operating room (OR) systems and checklists, have the potential to improve patient safety, OR efficiency, and surgical outcomes. This study was designed to investigate the influence of the integrated OR system and Pro/cheQ, a digital checklist tool, on the number and type of equipment- and instrument-related risk-sensitive events (RSE) during laparoscopic cholecystectomies.

Methods

Forty-five laparoscopic cholecystectomies were analyzed on the number and type of RSE; 15 procedures were observed in the cart-based OR setting, 15 in an integrated OR setting, and 15 in the integrated OR setting while using Pro/cheQ.

Results

In the cart-based OR setting and the integrated OR setting, at least one event occurred in 87% of the procedures, which was reduced to 47% in the integrated OR setting when using Pro/cheQ. During 45 procedures a total of 57 RSE was observed—most were caused by equipment that was not switched on or with the wrong settings. In the integrated OR while using Pro/cheQ the number of RSE was reduced by 65%.

Conclusions

Using both an integrated OR and Pro/cheQ has a stronger reducing effect on the number of RSE than using an integrated OR alone. The Pro/cheQ tool supported the optimal workflow in a natural way and raised the general safety awareness amongst all members of the surgical team. For tools such as integrated OR systems and checklists to succeed it is pivotal not to underestimate the value of the implementation process. To further improve safety and quality of surgery, a multifaceted approach should be followed, focusing on the performance and competence of the surgical team as a whole.

Keywords: Patient safety, Integrated OR, Checklist, Time-out, Adverse events, Human factors

During the early days, laparoscopic surgery had a relatively large number of complications and adverse events [1, 2]. Compared with traditional open surgery, laparoscopic surgery requires a different set of skills and the surgical team is more dependent on technology to perform the procedure effectively and efficiently [3–5]. The operating room (OR) is considered to be the most common site for adverse events in hospitals, of which many may be prevented [4–6]. In the OR adverse events can have various origins. They can be related to surgical competence, but also to teamwork skills, equipment problems, ergonomic shortcomings of the instrumentarium, or fatigue [2, 4, 5]. The Dutch Healthcare Inspectorate established that almost 20 years after the introduction of the technique, there are still no standards to ensure the quality and safety of performing laparoscopic surgery [7]. Patient safety for laparoscopic surgery needs to be better safeguarded by creating barriers to prevent risk-sensitive events (RSE). RSE are events that as such appear seemingly unimportant and easy to solve without consequences for the patient; however, under certain circumstances could contribute to and result in an adverse event [8].

Technological innovations, such as the integrated OR system, can help to prevent technical problems, improve ergonomics, reduce OR clutter, and enhance efficiency by decreasing turn-over time and improving the flow of information [9–11]. The use of preoperative checklists and time-out briefings to prevent surgery on the wrong patient, site, or side also have improved patient safety, OR efficiency, and surgical outcomes [12–16]. This study was designed to investigate the influence of the integrated OR system and the combined effect of the integrated OR system with Pro/cheQ, a digital procedure-specific checklist tool, on the number and type of equipment- and instrument-related RSE during laparoscopic cholecystectomies. The cholecystectomy procedure was chosen because it is a very common procedure performed by operating teams of which the composition frequently alters and often includes surgeons and nurses in training.

Materials and methods

In a large, nonuniversity, teaching hospital, 45 random laparoscopic cholecystectomies were recorded and analyzed in three different OR settings. Fifteen laparoscopic cholecystectomies were registered in the cart-based laparoscopic OR setting in July and August 2005. The OR staff was given the chance to become acquainted with the Karl Storz OR1™ integrated OR system, which was introduced in January 2006, after which 15 laparoscopic cholecystectomies were registered in the integrated setting (April to June 2008). Finally, from July to September 2008, another 15 laparoscopic cholecystectomies were registered in the integrated setting while using the Pro/cheQ tool. During all registered procedures, the operating team consisted of a surgeon and surgical trainee performing the surgery, assisted by a scrub nurse, circulating nurse, and often a surgical intern to handle the laparoscope.

The cart-based OR and integrated OR equipment

In the cart-based OR setting, the standard laparoscopic equipment (insufflator, xenon light source, and camera control unit, all by Karl Storz) was placed on a cart with a CRT monitor on top and a flat-screen monitor on a swivel-arm attached to side of the cart. The diathermy equipment and the suction/irrigation system were each placed on a separate cart. All observed procedures in the integrated OR setting, with and without using Pro/cheQ, took place in the same OR equipped with the Karl Storz OR1™ system, comprising all SCB®, Telemedicine, and AIDA® modules available at the time. The stack comprising the standard laparoscopic equipment, electrosurgical equipment, the suction/irrigation system, and a flat screen monitor was suspended on a ceiling-mounted boom-arm. Three flat screen monitors and the OR1 touch screen were each attached to separate ceiling-mounted boom-arms.

Pro/cheQ

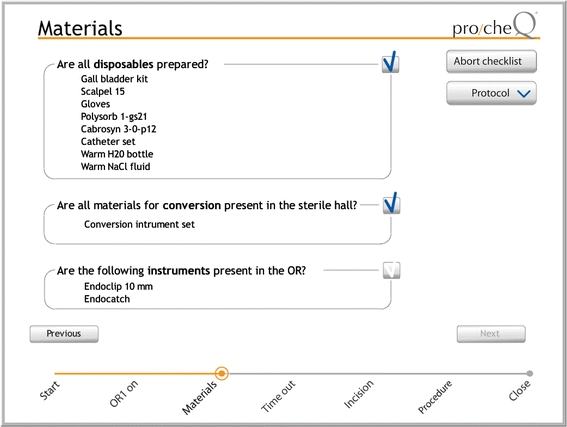

Pro/cheQ is a digital checklist tool designed to prevent RSE and enhance quality control during laparoscopic surgery by structuring and standardizing the preparation of equipment and instruments, time-out moments, recording of intraoperative images, debriefing, and filling out the operation report (Fig. 1). Pro/cheQ was developed following an iterative design process with a user-centered and user-participatory approach; combining knowledge from literature review with observations in the OR and multiple experts sessions with surgeons, OR nurses, and anesthesiologists [17]. The circulating nurse fills out most check items; however, completing Pro/cheQ requires active involvement of the whole surgical team. Therefore, all members of the surgical team of the observed procedures received instructions before the start of the preparations on how to use the checklist tool. A stand-alone procedure-specific laptop-based prototype of Pro/cheQ was used in this study, which did not incorporate the functions requiring a link with the digital hospital information system [17]. Therefore, these functions were simulated by the observing researcher, for example, by entering the patient data in Pro/cheQ and the AIDA system before the preparations of the procedure commenced.

Fig. 1.

One page of the Pro/cheQ tool

Registration of procedures

All procedures were recorded using a quad-audiovisual recording system that synchronously recorded the input from four cameras and one microphone. The recordings were started just before first incision and stopped when all the trocars were removed. Before each procedure, all members of the operating team were informed about the study and recordings and asked for consent. During all procedures, one of the researchers was present in the OR to observe the procedure and assist in the use of the checklist when requested. Procedures that were converted from laparoscopic to open procedures or where technical problems related to the recording equipment occurred were excluded.

In the cart-based OR setting, the quad-audiovisual stream comprised the laparoscope image, a room overview, and close-ups of the surgical team filmed by cameras mounted on top of the CRT monitor and the flat screen monitor, and a microphone. The video and audio streams were combined into one quad-audiovisual stream and recorded on a laptop. In the integrated OR setting, the AIDA and telemedicine facilities of the OR1 system were used to capture the images and combine them into one quad-audiovisual stream. The quad-audiovisual stream comprised the laparoscope image, a room overview, the touch screen interface, a close-up of the surgical team filmed by the OR1 surgical camera on a ceiling-mounted boom-arm, and the OR1 microphone. The quad-audiovisual stream was recorded by a separate DV recorder in the OR1 technical room to maintain availability of all OR1 utilities for the surgical team.

Data analysis

The recordings were analyzed by scoring the number and type of RSE related to the equipment or instruments used to perform the procedure. A RSE was defined as a situation when instruments or equipment were not available when needed by the surgeon. Next, the results for the three different OR settings were compared qualitatively. A randomly selected sample of five procedures for each OR setting was additionally analyzed by a second observer. The findings of the two observers for these 15 procedures were compared and the interobserver agreement was calculated. The Kappa statistic often is used for measuring interobserver agreement. However, Kappa presupposes that the total number of events is known or can be estimated. This was not the case in this study; therefore, the “any-two agreement” measure was used [18]. In total, the two observers identified 29 different equipment- or instrument-related RSE in the sample of 15 procedures, with a substantial any-two agreement of 0.66.

Results

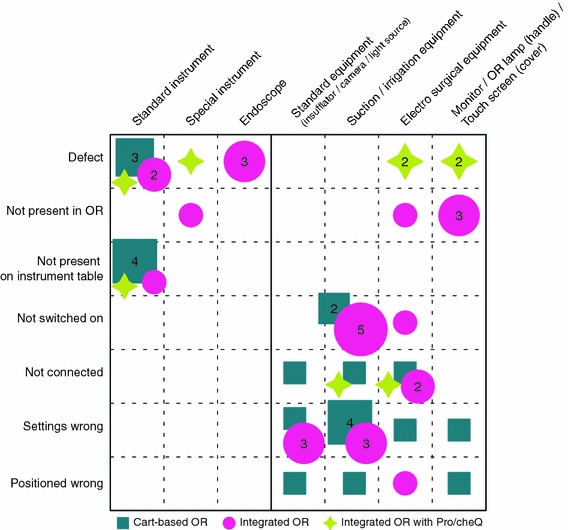

In 33 of the 45 analyzed procedures, one or more risk-sensitive events were observed (Table 1). Both in the cart-based OR setting and the integrated OR setting, at least one event occurred in 87% of the procedures. In the integrated OR setting when using Pro/cheQ, this was reduced to 47%. In total, 57 individual RSE were observed related to equipment or instruments (Table 1; Fig. 2). In the integrated OR with Pro/cheQ, considerably less events occurred compared with the cart-based OR; the total number was reduced by 59% and compared to the integrated OR setting alone by 65%. In all three environments most events were related to equipment. Most of the equipment- and instrument-related RSE that did occur in the integrated OR while Pro/cheQ was used were related to defects that could not have been identified during the preparation phase beforehand.

Table 1.

Total number of risk-sensitive events

| Cart-based OR | Integrated OR | Integrated OR with Pro/cheQ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedures ≥1 RSE | 13 (87%) | 13 (87%) | 7 (47%) |

| Procedures with | |||

| 0 RSE | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| 1 RSE | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| 2 RSE | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 3 RSE | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 6 RSE | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Total no. of RSE | 22 | 26 | 9 |

| Equipment related | 15 | 19 | 6 |

| Instrument related | 7 | 7 | 3 |

Fig. 2.

Type of equipment- and instrument-related risk-sensitive events observed in the three different OR settings

Discussion

General awareness has risen that patient safety needs to be improved, especially during procedures that are more dependent on technology and demand extra skills from the surgical team, such as laparoscopic surgery. Besides the skills of the surgeon, various nontechnical elements are of influence on surgical performance and patient safety [2, 4, 5]. Vincent et al. claimed that, amongst others, attention to ergonomics and equipment design and enhancing communication and team performance could even have a stronger influence on performance than surgical skills [5]. The use of an integrated OR system has the potential to improve the ergonomics, safety, and efficiency of laparoscopic surgery [9–11]. The application of preoperative checklists also has been shown to improve patient safety considerably [13–16]. Our purpose was to investigate the combined effect of using an integrated OR system—the Karl Storz OR1—together with a procedure-specific digital checklist—the Pro/cheQ tool—on the number and type of equipment- and instrument-related RSE.

This study showed that, in comparison to the cart-based OR, the combined usage of the integrated OR and the Pro/cheQ tool had a stronger reducing effect on the number of RSE than the usage of the integrated OR alone (Table 1). The type of events that occurred also differed (Fig. 2). Most RSE during the 45 observed procedures were restored by adjustment of the equipment settings or position. However, each event disrupted and prolonged the surgical process. In many cases the origin of the event could be traced back to the circulating nurse, who had forgotten or knowingly omitted to prepare something timely without informing the other members of the surgical team. Routine usage of Pro/cheQ proved to be feasible, it supported the optimal workflow in a natural way and was considered to be constructive by surgeons, anesthesiologists, and both inexperienced and experienced OR nurses [17]. The findings of this study are in concordance with previous investigations into the occurrence and type of equipment-related RSE during laparoscopic surgery, where equipment-related RSE were observed in 87 and 42% of the laparoscopic procedures [19, 20]. A study by Verdaasdonk et al. showed a similar effect on the reduction of RSE by the use of a reusable preoperative paper checklist for laparoscopic cholecystectomies; the number of procedures with one or more RSE was reduced from 87 to 47% [16].

The impact of using Pro/cheQ extended beyond a reduction of RSE. It increased the general safety awareness amongst the OR staff and improved the understanding of the importance of using all available means to work accordingly. To streamline the understanding of responsibilities and synchronize expectations amongst the members of the surgical team, Pro/cheQ structured several key elements of the communication within the team and required several issues to be uttered out loud in the presence of the whole team. The circulating nurse had the responsibility to secure the quality and course of the preparation process and to complete most of the checkmarks, but the whole team was responsible to execute Pro/cheQ properly. Catchpole et al. highlighted that improved team skills are associated with speedier completion of operations [4].

Unfortunately, adverse events can never be completely prevented. The engagement of the OR staff to look after quality and safety and the actual usage of supporting tools and setups, such as the integrated OR and checklist, is very important. In our hospital the technical department routinely checks all equipment following strict protocols and the scrub nurse checks the standard instruments before the start of each procedure, still several defects occurred during the observed procedures. Besides opportunities, new technology also brings along new risks and challenges [21]. The introduction and instructions for the use of new instruments and equipment often focuses mainly on functionality, whereas new tools are not always intuitive or straightforward in use. When using new technology to perform a procedure being already standard, a surgeon might encounter problems that expose previously unidentified gaps in his knowledge (related to the surgical technique or utilization of the technology, for example), in such a case he cannot rely on existing heuristics or experience but has to find new ways to bridge these gaps on an ad hoc basis. Improper usage of a product can sometimes affect a product’s functionality and create unsafe situations. To keep a checklist workable and efficient, it cannot comprise all potential issues to ensure detection of equipment defects before surgery. The OR staff should have sufficient knowledge about the working of the equipment and instruments, how to use them aptly, and how to act and troubleshoot if something unexpected occurs.

It can be pivotal for the success of an innovation not to underestimate the value of the implementation process when introducing new products or tools [14, 22]. The implementation process should be broadly based within the hospital; all staff should be familiar and aware of the added value and importance of the innovation. Training should focus on the application of the innovation as a whole, and create awareness and understanding about its added value for the total care chain. Preferably, future users should have a sense of ownership of the solution [14, 22]. Pro/cheQ was developed following a user-centered and user-participatory design approach, which diminished the habitual reluctance to changes in the existing workflow. This effect also was recognized in a similar study by Lingard et al. [14].

The setup of this study had some limitations. Fifteen months after introduction of the integrated OR system, which did include brief training of the OR staff, many of its functionalities were not actively used. The use of functionalities, such as importing patient data from the digital hospital information system into the AIDA system, highly depended on the circulating nurse’s personal preferences. Using Pro/cheQ in the integrated OR setting enforced the use of the key functionalities of the integrated OR. Possibly, this has influenced the results. The decrease in RSE in the integrated OR setting where Pro/cheQ was used was probably not only achieved due to the use of Pro/cheQ but also by the better use of the OR1 system. Second, Pro/cheQ was designed to run of the touch screen of the OR1 system. However, for this study a laptop-based prototype of Pro/cheQ was used and some Pro/cheQ functionalities were simulated. This made the presence of the checklist tool less prominent and less enforcing. Using an integrated OR system or Pro/cheQ properly does require a change of mindset and routine, and although while the teams did receive training, only 15 procedures were analyzed per OR setting. Even though a considerable reduction of RSE was found, we expect that when used for a longer period of time, fully embedded, and no longer perceived as “the new routine,” the benefits for patient safety of these tools can be even greater.

This study focused on equipment- and instrument-related RSE only. However, Pro/cheQ is more than a preoperative checklist. It was developed not only to prevent equipment- and instrument-related RSE, but also to improve the quality control throughout laparoscopic surgical procedures. Additional research is needed to further investigate the contribution of the integrated OR and Pro/cheQ on overall surgical performance and safeguarding of quality control. To further improve the safety and quality of surgery, a multifaceted approach should be followed. In this the improvement of the usability of the instruments and equipment is important as well as crew resource management and implementation of protocols and checklist to standardize work routines [19, 20]. The focus should shift from the technical skills of the surgeon to the competence and performance of the whole surgical team.

In conclusion, this study shows that using both an integrated OR system and the Pro/cheQ tool reduces equipment- and instrument-related risk-sensitive events more than using only an integrated OR. Routine usage of the Pro/cheQ tool with the integrated OR proved to support the optimal workflow in a natural way, and its impact extended beyond the reduction of RSE. It increased general safety awareness and synchronized the mutual understanding of responsibilities and expectations amongst the members of the surgical team. The engagement of the OR staff to value having a safety culture and actively use tools, such as the integrated OR and checklist, is very important. The implementation process of such tools should therefore be broadly based within the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the audiovisual department of the Catharina Hospital Eindhoven for their support in registering the procedures, in particular Guy van Dael. S.N. Buzink received a grant from the Scientific Fund of the Catharina Hospital Eindhoven, which was partly used for this research.

Disclosures

S. N. Buzink, L. van Lier, I. H. J. T. de Hingh, and J. J. Jakimowicz have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Moore M, Bennett C. The learning curve for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1995;170:55–59. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallagher A, Smith C. From the operating room of the present to the operating room of the future. Human-factors lessons learned from the minimally invasive surgery revolution. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2003;10:127–139. doi: 10.1177/107155170301000306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dincler S, Buchmann P. Evaluation of operational skills by learning curve. Chir Gastroenterol. 2004;20:16–19. doi: 10.1159/000083348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catchpole K, Mishra A, Handa A, McCulloch P. Teamwork and error in the operating room: analysis of skills and roles. Ann Surg. 2008;247:699–706. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181642ec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vincent C, Moorthy K, Sarker SK, Chang A, Darzi AW. Systems approaches to surgical quality and safety: from concept to measurement. Ann Surg. 2004;239:475–482. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000118753.22830.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leape L. The preventability of medical injury. In: Bogner M, editor. Human error in medicine. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van der Wal G (2007) Risico’s minimaal invasieve chirurgie onderschat. (Risks minimally invasive surgery underestimated). Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg (Dutch Healthcare Inspectorate), Den Haag, The Netherlands. http://www.igz.nl/publicaties/rapporten/2007/mic

- 8.Reason J. Human error: models and management. Br Med J. 2000;320:768–770. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7237.768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenyon TAG, Urbach DR, Speer JB, Waterman-Hukari B, Foraker GF, Hansen PD, Swanström LL. Dedicated minimally invasive surgery suites increase operating room efficiency. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1140–1143. doi: 10.1007/s004640080092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alarcon A, Berguer R. A comparison of operating room crowding between open and laparoscopic operations. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:916–919. doi: 10.1007/BF00188483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herron DM, Gagner M, Kenyon TL, Swanström LL. The minimally invasive surgical suite enters the 21st century. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:415. doi: 10.1007/s004640080134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saufl NM. Universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, wrong person surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004;19:348–351. doi: 10.1016/S1089-9472(04)00287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, Joseph S, Kibatala PL, Lapitan MC, Merry AF, Moorthy K, Reznick RK, Taylor B, Gawande AA. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–499. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingard L, Regehr G, Orser B, Reznick R, Baker GR, Doran D, Espin S, Bohnen J, Whyte S. Evaluation of a preoperative checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication. Arch Surg. 2008;143:12–17. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nundy S, Mukherjee A, Sexton JB, Pronovost PJ, Knight A, Rowen LC, Duncan M, Syin D, Makary MA. Impact of preoperative briefings on operating room delays: a preliminary report. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1068–1072. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verdaasdonk EG, Stassen LP, Hoffmann WF, van der Elst M, Dankelman J. Can a structured checklist prevent problems with laparoscopic equipment? Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2238–2243. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Lier L (2008) Design of a digital checklist interface for preparing laparoscopic procedures. MSc Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft

- 18.Hertzum M, Jacobsen NE. The evaluator effect: a chilling fact about usability evaluation methods. Int J Hum-Comput Int. 2003;15:183–204. doi: 10.1207/S15327590IJHC1501_14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verdaasdonk EG, Stassen LP, van der Elst M, Karsten TM, Dankelman J. Problems with technical equipment during laparoscopic surgery. An observational study. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:275–279. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Courdier S, Garbin O, Hummel M, Thoma V, Ball E, Favre R, Wattiez A. Equipment failure: causes and consequences in endoscopic gynecologic surgery. J Minim Invas Gyn. 2009;16:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geertsma RE (2008) Nieuwe technologieën. Rapportage ten behoeve van SGZ-2008. Bilthoven: Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM). Report no.: 360004002/2008. http://www.igz.nl/publicaties/staatvandegezondheidszorg/sgz-2008

- 22.Norton E. Implementing the universal protocol hospital-wide. AORN J. 2007;85:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.aorn.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]