Abstract

Background

Carcinoma of the gastric remnant after partial gastrectomy for benign disease or cancer is unusual but an important cancer model. The Japanese Society for the Study of Postoperative Morbidity after Gastrectomy (JSSPMG) performed a nationwide questionnaire survey to understand the current state of gastric stump carcinoma in Japan.

Methods

In the questionnaire survey of November 2008, gastric stump carcinoma was defined as an adenocarcinoma of the stomach occurring 10 years or more after Billroth I or Billroth II gastrectomy for benign condition or cancer disease. The survey was conducted at the request of reports on five or more patients with gastric stump carcinoma for each institution. Items for the survey included gender, age, methods of reconstruction in an original gastrectomy, original diseases, time interval between original gastrectomy and first detection of stump carcinomas, locations of stump carcinomas, tumor histology, tumor depth, and extent of lymph node metastasis. The questionnaire was sent to 163 surgical institutions in the JSSPMG.

Results

Ninety-five institutions (58.3%) responded to the survey, and the data of 887 patients satisfied the required conditions for the survey. A total of 887 patients were composed of 368 patients who received Billroth I distal gastrectomy and 519 who received Billroth II. The Billroth II group has a significantly higher number of original benign lesions than the Billroth I group (P < 0.001). This study confirmed the following issues: (1) The remnant stomach after gastrectomy for cancer disease had a higher prevalence to develop stump carcinomas occurring in a shorter time interval since original gastrectomy; (2) Patients with Billroth II gastrectomy had stump carcinomas most frequently in the anastomotic area, but not in the non-stump area as in Billroth I gastrectomy; (3) Tumor histology of 72.4% of 304 stump carcinomas at an early stage was intestinal type adenocarcinoma, i.e., well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, whereas it decreased to 42.2% at the locally advanced stage of 521 stump carcinomas (P = 0.0015), suggesting that stump carcinoma mostly may develop from intestinal type and change to diffuse type during the evolution to advanced stage cancers.

Conclusions

This large series of surveys suggest that there are two distinct biological plausibilities in the development of gastric stump carcinoma: (1) it develops in a shorter time interval of 10 years or less since the original gastrectomy, may come from a higher risk of gastric mucosa after gastrectomy for cancer diseases that highly predisposes to cancer, and (2) it develops during a longer time interval of 20 years or more, may come from gastrectomy-relating mechanisms after gastrectomy for original benign diseases.

Introduction

Carcinoma of the gastric remnant after partial gastrectomy for benign disease or cancer is unusual but an important cancer model. For the past 80 years, investigators have suggested that there is an increased risk of gastric cancer after gastrectomy for benign diseases [1–3]. Also, elevations in stomach cancer risk in the remnant stomach after gastric surgery have been reported in several cohort studies [4–7]. However, other investigators have found no increases in risk or increases limited to 15 or more years after gastrectomy [8–10]. Several reports have postulated that such different conclusions may come from some discrepancies between studies, i.e., a study of gastric ulcer patients alone would show an excess risk of gastric cancer, irrespective of the follow-up periods, whereas one of the duodenal ulcer patients alone would not indicate an excess risk unless the follow-up was more than 20 years [10]. The biological plausibility of the association of the remnant stomach with cancer development stems from the previous demonstration in animal models and in humans of increases in luminal bacterial flora resulting from neutralization of gastric acidity following gastric surgery [11, 12]. These anaerobic bacteria convert nitrates consumed in the diet to nitrites, known precursors of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds. In addition, persistent reflux of secondary bile, a common result of gastric surgery, promotes chronic gastritis and eventual metaplasia, often suggested as a precursor of neoplasia [13, 14].

Previous studies have demonstrated that rates of gastric stump carcinoma are consistently higher after treatment with a Billroth II procedure than after treatment with a Billroth I procedure [6, 7, 10, 15–17]. The increased risk with the Billroth II procedure has been attributed to continuous bathing of the gastric stump anastomosis with secondary bile acids, resulting in mucosal inflammation and regeneration [18].

In November 2008, the Japanese Society for the Study of Postoperative Morbidity after Gastrectomy (JSSPMG) conducted a nationwide questionnaire survey to evaluate the current state of gastric stump carcinoma in Japan. This paper demonstrates the results of 887 patients with gastric stump carcinoma who underwent surgical treatment in 95 Japanese medical institutions that responded to the questionnaire survey of SSPMG.

Patients and methods

Gastric stump carcinoma is defined as an adenocarcinoma of the stomach occurring 10 years or more after gastrectomy for benign disease or cancer. A minimal latency of 10 years is chosen to avoid spurious effects due to faulty diagnosis of conditions and to exclude any cases with recurrent cancer diseases, because recurrent cancer developing in the remnant stomach at 10 years or more after original gastrectomy for cancer is extremely rare [19, 20]. The methods for reconstruction after distal gastrectomy in this survey were limited to the Billroth I or Billroth II method and did not include any other type of reconstruction, such as Roux-en-Y or jejunal interposition. Items for the questionnaire survey included gender, age, methods of reconstruction at original gastrectomy, original disease, time interval between original gastrectomy and the first detection of stump carcinoma, location of stump carcinoma, tumor histology, tumor depth, and extent of lymph node metastases. The questionnaire was sent to a total of 163 surgical institutions in the JSSPMG. The survey was conducted at the request of reports on five or more patients with gastric stump carcinoma for each institution.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed by SSPS 12.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number and percentage of patients. Continual variables, including time interval after original surgery, have been expressed as mean ± SD, and comparisons between groups were performed by using the Mann–Whitney U test and t test. Comparisons of categorical variables were performed by using the Pearson’s chi-square or Fisher exact tests. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Ninety-five institutions (58.3%) responded to the survey, and the data of 887 patients satisfied the required conditions for the survey.

Time interval for development of stump carcinoma and relevance of original diseases and modes of reconstruction

A total of 887 patients were composed of 368 patients who received Billroth I distal gastrectomy and 519 who received Billroth II. More than 80% of patients of each group were men. The mean ages and gender distribution of both groups at detection of stump carcinoma were similar. The Billroth II group has a significantly higher number of original benign lesions than the Billroth I group (P < 0.001). The time interval between original gastrectomy and detection of stump carcinomas was 21.1 ± 9.5 years for 368 patients with Billroth I gastrectomy and 31.5 ± 11 years for 519 patients with Billroth II gastrectomy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics in the groups with Billroth I or Billroth II reconstruction

| Billroth I | Billroth II | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 368 | 519 |

| Male:female (%) | 82:18 | 88:12 |

| Age (yr) | 68 ± 9.4 | 68 ± 9.2 |

| Benign:cancer in origin | 161:207 | 417:102 |

| Intestinal:diffuse | 190:178 | 261:258 |

| Early:advanced | 154:214 | 163:256 |

| Time interval (year) | 21.1 ± 9.5 | 31.5 ± 11.0 |

Age and time intervals are mean ± standard deviation

To elucidate the effect of the time interval since original gastrectomy, the reported number of stump carcinomas was examined over time after the original gastrectomy. A total of 309 patients with original cancer disease (207 with the Billroth II method and 102 with Billroth I) developed stump carcinoma an average of 18.0 years after original gastrectomy, whereas the average time interval was extended to 32.0 years in 578 patients with original benign disease (161 with Billroth I and 417 with Billroth II; P < 0.001). When they were separately analyzed with a combination of Billroth methods, it was 27.2 ± 9 years for 161 patients with the Billroth I method and 33.9 ± 10.1 years for 417 patients with original benign disease with the Billroth II method, whereas it was 16.4 ± 6.8 years for 207 patients with Billroth I and 21.3 ± 8.1 years for 102 patients with Billroth II in those with original cancer disease (P > 0.05; Table 2). Namely, the patients with original cancer disease developed stump carcinoma in a significantly shorter time interval than those with original benign diseases, but there was no significant difference in the time interval between Billroth I and Billroth II for original benign or cancer disease.

Table 2.

Comparison of baseline characteristics in the groups stratified by combination of Billroth I or II reconstruction and original diseases

| Mode of surgery | BI benign | BI cancer | BII benign | BII cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 161 | 207 | 417 | 102 |

| Male:female (%) | 86:14 | 79:21 | 91:9 | 76:4 |

| Age (year) | 67 ± 9.4 | 69 ± 9.3 | 67 ± 9.2 | 70 ± 8.4 |

| Time interval (year) | 27.2 ± 9.0 | 16.4 ± 6.8 | 33.9 ± 10.1 | 21.3 ± 8.1 |

BI benign Billroth I reconstruction for an original benign disease, BI cancer Billroth I reconstruction for an original cancer disease

Age and time intervals are mean ± standard deviation

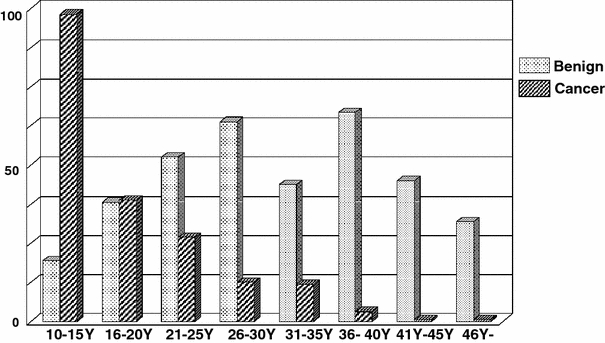

The time trend of a reported number of stump carcinomas for every 5 years after original distal gastrectomy was studied based on original benign or cancer diseases. For patients with original cancer disease, the reported number of stump carcinomas was the highest at 10–15 years after surgery, followed by a gradual decrease in incidence (Fig. 1). In contrast, for patients with original benign disease, it was the lowest incidence at 10–15 years after surgery, followed by a steady increase (P < 0.001; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Time trend of a reported number of stump carcinomas every 5 years after original distal gastrectomy for benign or cancer diseases: after gastrectomy for benign diseases; after gastrectomy for cancer

Tumor sites in the remnant stomach

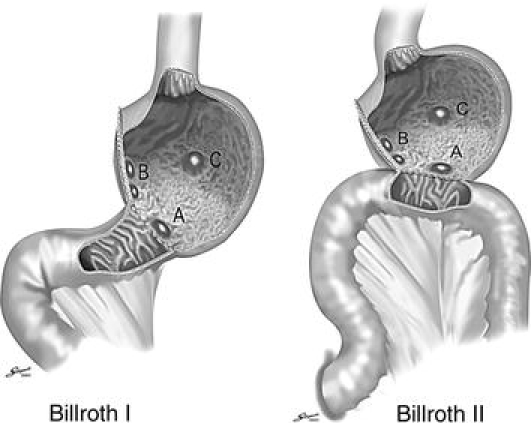

The location of stump carcinomas was evaluated based on the modes of reconstruction at original gastrectomy and the original character of the disease. Tumor locations were defined as the following four parts, including the gastroduodenal or gastrojejunal anastomotic site, gastric stump line, non-stump area, and broadly extended area in the remnant stomach (Fig. 2). Of interest was that patients with Billroth II gastrectomy had stump carcinomas most frequently in the anastomotic area, regardless of the character of the original diseases, whereas stump carcinomas for those with Billroth I gastrectomy were more frequently located in the non-stump area (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Tumor locations in the remnant stomach. a Anastomotic site; b gastric stump line; c non-stump area

Table 3.

Tumor locations of stump carcinomas in the remnant stomach mode of surgery

| Mode of surgery | BI benign | BI cancer | BII benign | BII cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 161 (100) | 207 (100) | 417 (100) | 102 (100) |

| Anastomotic site | 42 (26) | 39 (20) | 250 (60) | 39 (38) |

| Stump line | 36 (22) | 17 (23) | 50 (12) | 18 (17) |

| Non-stump area | 73 (46) | 103 (51) | 83 (20) | 31 (31) |

| Extended | 10 (6) | 13 (6) | 34 (8) | 14 (14) |

BI benign Billroth I reconstruction for an original benign disease, BI cancer Billroth I reconstruction for an original cancer disease

Data in parentheses are percentages

Tumor histology

Distribution of tumor histology of the stump carcinoma was evaluated based on tumor stages and tumor sites. Tumor histology of 72.4% of 304 stump carcinomas at an early stage was intestinal type adenocarcinoma, i.e., well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, whereas it decreased to 42.2% at the locally advanced stage of 521 stump carcinomas (P = 0.0015). This trend was consistent irrespective of the tumor sites (data not shown).

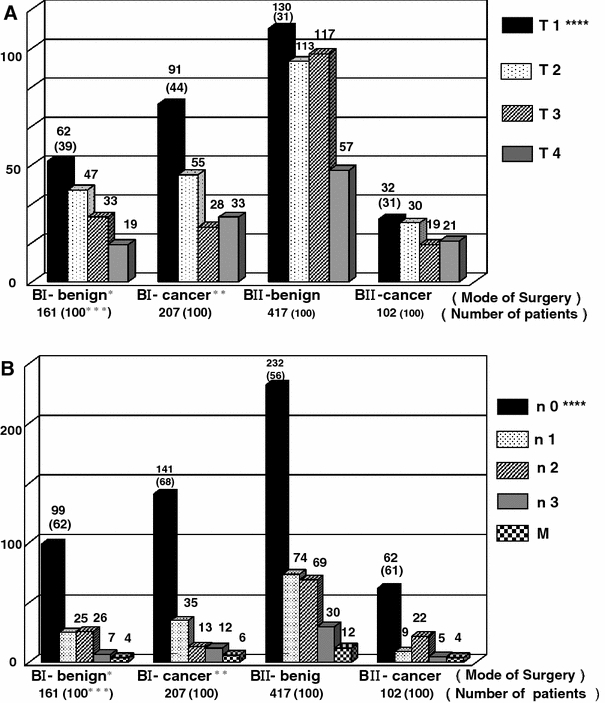

Tumor depth and extent of lymph node metastasis of stump carcinomas

Distribution of tumor depth and extent of lymph node metastasis also were evaluated based on the modes of reconstruction at original gastrectomy and characteristics of the original disease (Fig. 3a, b). Earlier stage of stump carcinomas, such as a tumor confined in the mucosa or submucosa (T1) and no lymph node metastasis (no), were more frequently detected in patients with Billroth I gastrectomy than those with Billroth II gastrectomy, regardless of the characteristics of the original disease (P < 0.0001 for T1 stage, P = 0.0102 for no stage).

Fig. 3.

a Tumor depths of stump carcinomas. * BI-benign means Billroth I gastrectomy for an original benign disease. ** BI-cancer means Billroth I gastrectomy for an original cancer disease. *** Number in parenthesis is a percentage. **** T1–4 was defined according to the UICC classification. b Extent of lymph node metastases of stump carcinomas. * BI-benign means Billroth I gastrectomy for an original benign disease. ** BI-cancer means Billroth I gastrectomy for an original cancer disease. *** Number in parenthesis is a percentage. **** n0–3 and M were defined according to the UICC classification

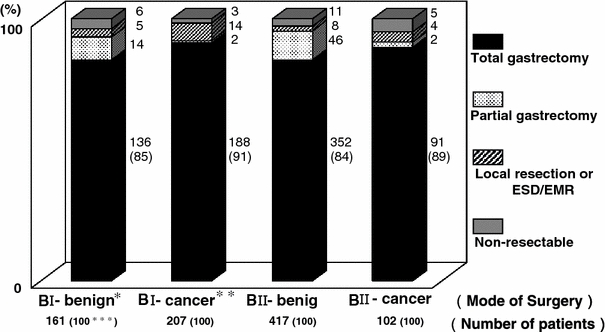

Surgical procedures for stump carcinomas

Modes of surgical procedure for stump carcinomas were evaluated in a similar way. Most surgical procedures (approximately 90%) were total gastrectomy regardless of Billroth I or II original gastrectomy. Partial gastrectomy and local resection, including endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), were significantly more frequent in patients with original benign disease than those with original cancer disease (Fig. 4; P = 0.0105).

Fig. 4.

Surgical procedures for gastric stump carcinomas. * BI-benign means Billroth I gastrectomy for an original benign disease. ** BI-cancer means Billroth I gastrectomy for an original cancer disease. *** Number in parenthesis is a percentage. EMR endoscopic mucosal resection, ESD endoscopic submucosal dissection

Discussion

Although a questionnaire survey is a useful tool for answering clinical inquiries by pooling data, it has the following drawbacks. The results of the survey are influenced by the character of the questions, including contents, order, length and the method of description, and the survey study lacks any systems of objective validation of the reported data. In addition, this case-survey study cannot estimate the incidence rate of the disease because the study does not include all patients like in a cohort setting. Despite these limitations, the present questionnaire survey makes important observations in the understanding of gastric stump carcinoma in Japan.

This study confirmed some important matters, including the fact that patients with original cancer disease developed stump carcinoma in a significantly shorter time interval than those with original benign diseases, mostly peptic ulcers. The time trend of the reported number of stump carcinomas was quite different in manner between the patients with original cancer diseases and those with benign conditions. Namely, it was the highest at 10–15 years (shortest time interval in the study) followed by a gradual decrease in number thereafter for patients with original cancer diseases, whereas it was the lowest at 10–15 years after surgery for patients with original benign diseases, followed by a steady increase thereafter.

Those data seem to suggest that carcinogenesis in the remnant stomach may occur based on quite different mechanisms, namely one may come from mucosa with higher risk in the remnant stomach after gastrectomy for cancer diseases and another may come from some already reported mechanisms developed after gastrectomy for original benign diseases [13, 14, 18]. Regarding the risk of stump carcinoma after gastric surgery for benign diseases, several investigations in western countries have reported on possible elevations in gastric stump carcinoma risk after gastric surgery [10, 21, 22], although other studies have found no increases in risk or increases limited to 15 or more years after gastrectomy for benign diseases [4, 5, 8, 9, 16, 23]. Thus, it is controversial whether the development of gastric stump carcinoma may be directly related to the postoperative time interval. However, part of this study of postgastrectomy for benign diseases confirmed that there is a higher risk of development of stump carcinoma in postoperative stomach and the risk increases gradually over time until 30 years postoperatively. In addition, although some studies [16, 24] suggested that the risk of gastric stump carcinomas increases after an apparent latency of 20 years or more after gastric surgery, there was no latency period found in the current study. The issue of whether there would be different risk of stump carcinoma based on the mode of reconstruction, Billroth I or II, is of interest. However, when the association between risk of stump carcinoma and the mode of reconstruction is evaluated, we should consider the varying number of applications of Billroth I or II procedures in these decades, because indication and absolute number of Billroth I or II procedures were not constant during these periods. It was preferable to use the Billroth II procedure, but not Billroth I, for gastrectomy for peptic ulcers before the late 1980 s in Japan [25]. Since H2-blocker became available for use in our clinics from the late 1980s to the early 1990s, the number of gastric surgeries for peptic ulcers remarkably decreased since 1990 in Japan [26, 27], and at the same time Billroth I gastrectomy, instead of Billroth II gastrectomy, has become the standard procedure for cases with peptic ulcer diseases [25, 27]. As this questionnaire survey was performed in the fall of 2008, the Billroth I procedure for peptic ulcers seemed to be more frequently applied than the Billroth II procedure at 16–20 or less postoperative years, whereas the number of Billroth II procedures was more dominant at 21–25 or more postoperative years. In addition to such variable backgrounds, as Table 2 indicates, there was no significant difference in the time interval between Billroth I and Billroth II gastrectomy for original benign or cancer disease. Accordingly, this retrospective survey does not seem appropriate to study the association of risk of stump carcinoma development with the mode of reconstruction.

Tumor locations in the remnant stomach were characteristic. Consistent with previous reports [12, 28–30], patients with Billroth II gastrectomy had stump carcinomas most frequently in the anastomotic area, but not the non-stump area, such as those with Billroth I gastrectomy. This issue is in line with various reports, indicating that the increased risk with the Billroth II procedure has been attributed to continuous bathing of the gastric stump anastomosis with secondary bile acids, resulting in mucosal inflammation and regeneration [18].

Evolutional changes of tumor histology of gastric stump carcinomas between an early stage and a locally advanced stage also were of interest, suggesting the stump carcinoma may mostly develop from intestinal type adenocarcinoma and change to diffuse type, during evolution towards locally advanced cancers. Gastritis cystic polyposa has long been identified as a characteristic precursor lesion of gastric stump carcinoma [31]. The issue that most of the early stump carcinomas were of the intestinal type in the current analysis does not conflict with previous findings. As for tumor histology of primary gastric cancer, there are, in general, slightly more intestinal types (55–60%) with early cancers and more diffuse types (58–63%) with advanced cancers [32–34]. Therefore, obvious changes of tumor histology in the current study may indicate a typical pattern of clonal evolution during the progression of gastric cancer.

The analysis of distribution of tumor depth and extent of lymph node metastases demonstrated that earlier stage stump carcinomas were found more in patients with Billroth I gastrectomy, probably because of easier detection of stump carcinoma in patients with Billroth I gastrectomy and less frequency of clinical manifestations in those with Billroth II [35].

Regarding surgical procedures for stump carcinomas, significantly more frequent application of partial gastrectomy and local resection for patients with those benign in origin might be associated with a rather larger size of stomach remaining for those patients.

The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection, a recently reported risk factor for stomach cancer [36, 37] is not known in this study sample. However, the current study clearly indicates that the remnant stomach after gastrectomy for cancer had higher prevalence to develop stump carcinomas occurring in a shorter time interval, suggesting a relationship between the higher risk of gastric mucosa and development of stump carcinomas in a shorter time interval. It is now widely accepted that Helicobacter pylori plays a role in the pathogenesis of gastric cancer. In addition, the higher prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in early cancer than in locally advanced cancer may suggest its possible association with the pathogenesis of gastric stump carcinomas [38].

Conclusions

This study provides adequate power to detect important observations in the understanding of gastric stump carcinoma by virtue of the large sample (887 patients with gastric stump carcinomas). This study confirms the following important issues: (1) Patients with original cancer disease developed stump carcinoma in a significantly shorter time interval than those with original benign conditions whose stump carcinomas gradually increased as years passed; (2) Patients with Billroth II gastrectomy had stump carcinomas most frequently in the anastomotic area but not in the non-stump area like those with Billroth I gastrectomy; (3) There were remarkable differences in the tumor histology of gastric stump carcinomas between the early stage mostly having intestinal type and the locally advanced stage having diffuse type.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Yasuichiro Nishimura, Department of Mathematics of Osaka Medical College, for his kind advice in the statistical analysis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Addendum

Institution (Principal Investigators)

National Cancer Center (Katai H), Kanazawa Medical University (Takashima S), National Cancer Center Hospital East (Kinoshita T), Aichi Cancer Center (Yamamura Y), Yokohama City University Medical Center (Kunisaki T), Nippon Medical School (Tajiri T), Kyoto Second Red Cross Hospital (Takenaka A), Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine (Otsuji E), National Kyushu Cancer Center (Fuji Y), Juntendo University School of Medicine (Tsurumaru M), Tokyo Women’s Medical University Center East (Ogawa K), Niigata City General Hospital (Saito H), Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medical Science (Ota T), Ibaraki Prefectural Central Hospital (Nagai H), Osaka Koseinenkin Hospital (Yamazaki Y), Graduate School of Medicine and Faculty of Medicine, the University of Tokyo (Kaminishi M), Hiroshima City Asa Hospital (Takiyama W), Kitasato University East Hospital (Sakuramoto S), School of Medicine Hirosaki University (Sasaki M), Osaka Medical College (Tanigawa N), Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine (Hirakawa K), Toyonaka Municipal Hospital (Tsukahara Y), Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences (Hatakeyama K), Miyagi Cancer Center (Fujiya T), University of Yamanashi Hospital (Fujii H), Health Insurance Naruto Hospital (Iwasaka N), Saku Central Hospital, Nagano Prefectural Federation of Agricultural Cooperatives for Health and Welfare (Ooi E), Tsuruoka municipal Shonai Hospital (Matsubara Y), Fukui Red Cross Hospital (Matsushita T), Hoshigaoka Koseinenkin Hospital (Tatsumi M), Akita University Graduate School of Medicine (Yamamoto Y), Arita GI Hospital (Arita T), Iwate Medical University (Wakabayashi G), Chiba Cancer Center (Takiguchi N), Yonezawa City Hospital (Kitamura M), University of Occupational and Environmental Health (Nagata N), Yamagata Prefectural Kahoku Hospital (Watanabe S), Yamagata University Faculty of Medicine (Kimura W), Social Insurance Chuo General Hospital (Bandai Y), Asahikawa Medical College (Kasai S), Asahikawa Red Cross Hospital (Hishiyama T), Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital (Yamada T), Oita University Faculty of Medicine Graduate School of Medicine (Kitano S), Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine (Monden M), Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital (Takabatake T), Kanagawa Cancer Center (Yoshikawa T), Kyushu University (Maehara Y), Gifu Municipal Hospital (Oshita H), Niigata Cancer Center Hospital (Nashimoto A), Tohoku University Hospital (Sasaki I), Saitama Medical Center (Ishida H), Sasebo City General Hospital (Ishikawa H), Shiga University of Medical Science (Tani T), Shikoku Cancer Center (Kurita H), Showa University of Toyosu Hospital (Kumagai K), Showa University Hospital (Kusano M), Sakai Municipal Hospital (Furukawa H), Saitama Medical Center Jichi Medical University (Konishi F), Tokai University Tokyo Hospital (Kondo Y), Kashiwa Hospital, Jikei University School of Medicine (Nakada K), Tokyo Women’s Medical University Hospital (Yamamoto M), Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious diseases Center Komagome Hospital (Iwasaki Y), Tochigi Cancer Center (Inada T), Tokyo Metropolitan Bokutoh Hospital (Arai K), Dokkyo Medical University (Sunagawa M), Nagaoka Chuo General Hospital (Shimizu T), Niigata Prefecture Yoshida Hospital (Tamiya Y), Nippon Medical School Musashi Kosugi Hospital (Tokunaga A), Nihon University School of Medicine (Takayama T), Himeji Central Hospital (Ishida Y), Hiroshima City Hospital (Ninomiya M), Fukushima Medical University (Goto M), Fujita Health University (Uyama I), Hokkaido Cancer Center (Naito H), National Defense Medical College (Mochizuki H), Matsuyama Shimin Hospital (Miyata N), South Miyagi Medical Center (Naito H), Yamaguchi University (Oka M), Wakayama Rosai Hospital (Tsuji T), Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases (Miyashiro I), Tokyo Medical University (Aoki T), Nagasaki University (Kanematsu T), Hokkaido Gastroenterology Hospital (Morita T), Aizawa Hospital (Tanaka K), NTT West Osaka Hospital (Monden T), Public Shiso General Hospital (Yamasaki Y), Hokkaido P.W.F.A.C Asahikawa-Kosei General Hospital (Takahashi M), Nagoya City University (Fujii Y), Kinki University School of Medicine (Shiozaki H), Teikyo University School of Medicine University Hospital, Mizonokuchi (Sugiyama Y).

Footnotes

Institutions and corresponding doctors are listed in the Addendum.

References

- 1.Balfour DC. Factors influencing the life expectancy of patients operated on for gastric ulcer surgery. Ann Surg. 1922;76:405–408. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192209000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helsingen N, Hillestad L. Cancer development in the gastric stump after partial gastrectomy for ulcer. Ann Surg. 1956;143:170. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195614320-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Domellof L, Eriksson S, Janunger KG. Late precancerous changes and carcinoma of the gastric stump after Billroth I resection. Am J Surg. 1976;132:26. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(76)90284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shafer LW, Larson DE, Melton LJ, III, et al. The risk of gastric carcinoma after surgical treatment for benign ulcer disease: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1210–1213. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198311173092003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross AH, Smith MA, Anderson JR, et al. Late mortality after surgery for peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:519–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198208263070902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundegardh G, Adami HO, Helmick C, et al. Stomach cancer after partial gastrectomy for benign ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:195–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807283190402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnthorsson G, Tulinius H, Egilsson V, et al. Gastric cancer after gastrectomy. Int J Cancer. 1988;42:365–367. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910420310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fischer AB, Graem N, Jensen OM. Risk of gastric cancer after Billroth II resection for duodenal ulcer. Br J Surg. 1983;70:552–554. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tokudone S, Kono S, Ikeda M, et al. A prospective study on primary gastric stump cancer following partial gastric surgery for benign gastroduodenal diseases. Cancer Res. 1984;44:2208–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caygill CPJ, et al. Mortality from gastric cancer following gastric surgery for peptic ulcer. Lancet. 1986;1:929–931. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)91041-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenlee HB, Bibit R, Paez H, et al. Bacterial flora of the jejunum following peptic ulcer surgery. Arch Surg. 1974;102:260–265. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1971.01350040022005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miwa K, Fujima T, Hasegawa H, et al. Duodenal reflux through the pylorus induces gastric adenocarcinoma in the rat. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13:2313–2316. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruddell W, Bone E, Hill M, et al. Gastric juice nitrate: a risk factor for cancer in the hypochlorhydric stomach? Lancet. 1976;2:1037–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90962-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlag P, Bockler R, Ulrich H, et al. Are nitrate and N-nitroso compounds in gastric juice risk factors for carcinoma in the operated stomach? Lancet. 1980;1:727–729. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(80)91229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahm K. Cancer of the gastric stump. In: Decosse JJ, Sherlock P, editors. Gastrointestinal cancer I. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff; 1981. pp. 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tersmette AC, Offerhaus GJ, Tersmette KW, et al. Meta-analysis of the risk of gastric stump cancer: detection of high risk patient subsets for stomach cancer after remote partial gastrectomy for benign conditions. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6468–6469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moller H, Toftgaad C. Cancer occurrence in a cohort of patients surgically treated for peptic ulcer. Gut. 1991;32:740–744. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.7.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher A, Graem N, Christiansen L. Causes and clinical significance of gastritis following Billroth II resection for duodenal ulcer. Br J Surg. 1983;70:321–325. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800700606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer and Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (1972–2001) Statistical report of nationwide registry of gastric carcinoma [in Japanese]. National Cancer Center, Tokyo, No. 1-54

- 20.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Registration Committee. Maruyama K, Hayashi K, Isobe Y, et al. Gastric cancer treated in 1991 in Japan: analysis of nationwide registry. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:51–66. doi: 10.1007/s10120-006-0370-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viste A, Bjornestad E, Opheim P, et al. Risk of carcinoma following gastric operations for benign disease. A historical cohort study of 3, 470 patients. Lancet. 1986;2:502–504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(86)90368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher SG, Davis F, Nelson R, et al. A cohort study of stomach cancer risk in men after gastric surgery for benign disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1303–1310. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.16.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asano A, Mizuno S, Sasaki R, et al. The long-term prognosis of patients gastrectomized for benign gastroduodenal diseases. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1987;78:337–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Offerhaus GJA, van de Stadt J, Huibregtse K, et al. Endoscopic screening for malignancy in the gastric remnant: the clinical significance of dysplasia in gastric mucosa. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:748–754. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.7.748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuwabara Y, Kataoka M. Change of surgical strategies for gastroduodenal ulcer diseases [in Japanese] Mod Med. 1994;42:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aoki T, Nagao F. Indication of surgical treatment and choice of surgical methods [in Japanese] Surg Treat. 1987;29:853–858. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimazu H. Current state of surgical treatment for peptic ulcers [in Japanese] Digest Surg. 1993;16:1157–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanigawa N, Nomura E, Niki H, et al. Clinical study to identify specific characteristics of cancer newly developed in the remnant stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:23–28. doi: 10.1007/s101200200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langhans P, Heger RA, Hohenstein J, et al. Operation-sequel carcinoma of the stomach. Experimental studies of surgical techniques with and without resection. World J Surg. 1981;5:593–605. doi: 10.1007/BF01655015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishidoi H, Koga S, Kaibara N. Possible role of duodenogastric reflux on the development of remnant gastric carcinoma induced by N-methyl-N’-nitro-N-nitroguanidine in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;72:1431–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Littler ER, Gleibermann E. Gastritis cystica polyposa. Cancer. 1972;29:205–209. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<205::AID-CNCR2820290130>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–225. doi: 10.1007/PL00011720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rohde H, Stutzer H, Bauer P, et al. Early stomach cancer in comparison with advanced stomach cancer. Results of a prospective study of diagnosis and 5-year survival of 131 patients with early stomach cancer and 795 patients with advanced stomach cancer. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1991;376:16–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00205122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, et al. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:453–462. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson JL, Wiener JL. Evaluation of surgical treatment for duodenal ulcer: short- and long-term effects. Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;13:569–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuipers EJ. Review article: exploring the link between Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kato M, Asaka M, Shimizu Y, et al. Relationship between Helicobacterpylori infection and the prevalence, site and histological type of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]