Abstract

The dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is one of the most prominent regions in the postnatal mammalian brain where neurogenesis continues throughout life. There is tremendous speculation regarding the potential implications of adult hippocampal neurogenesis, though it remains unclear to what extent this ability becomes attenuated during normal aging, and what genetic changes in the progenitor population ensue over time. Using defined elements of the nestin promoter, we developed a transgenic mouse that reliably labels neural stem and early progenitors with green fluorescent protein (GFP). Using a combination of immunohistochemical and flow cytometry techniques, we characterized the progenitor cells within the dentate gyrus and created a developmental profile from postnatal day 7 (P7) until 6 months of age. In addition, we demonstrate that the proliferative potential of these progenitors is controlled at least in part by cell-autonomous cues. Finally, in order to identify what may underlie these differences, we performed stem cell-specific microarrays on GFP-expressing sorted cells from isolated P7 and postnatal day 28 (P28) dentate gyrus. We identified several differentially expressed genes that may underlie the functional differences that we observe in neurosphere assays from sorted cells and differentiation assays at these different ages. These data suggest that neural progenitors from the dentate gyrus are differentially regulated by cell-autonomous factors that change over time.

Keywords: brain development, hippocampus, neural stem cell, microarray

Introduction

The subgranular zone (SGZ) in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is one of at least two neurogenic regions in the adult brain (Altman and Das, 1965; Gage et al., 1995; Luskin, 1993; Suhonen et al., 1996). It contains neural stem/progenitor cells that can give rise in vitro to various cell types including neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes, though in vivo they are primarily precursors for dentate gyrus granular neurons (Frederiksen and McKay, 1988; Fricker et al., 1999; Seaberg and van der Kooy, 2002; Suhonen et al., 1996). During hippocampal neurogenesis progenitors self-renew and produce granular neurons that migrate into the granule cell layer of the dentate gyrus (Abrous et al.; Kempermann and Gage, 2000)

Several processes must occur in order for neurogenesis to take place. First, mitotic cells divide to give rise to progenitor cells that will eventually become new neurons (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2002; Cameron and McKay, 2001). In the dentate gyrus these type I “stem cells” express markers characteristic of both stem and astrocytic lineages and are able to self-renew and differentiate into various committed cell types (Alvarez-Buylla et al., 2002; Cameron et al., 1998; Cameron and McKay, 2001; Edgar et al., 2002; Encinas et al., 2006; Frederiksen and McKay, 1988; Joels et al., 2004). Type I cells are distinguished from other progenitors by expression of the astrocytic marker glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) as well as GFP in the nestin transgenic animal (Miles and Kernie, 2008; Yu et al., 2008). Second, these newly formed progenitors (type I and II) must commit and differentiate into a neuronal lineage (Cameron et al., 1998). During this process most mitotic progenitors divide and produce postmitotic cells that begin to express neuroblast-specific markers including doublecortin (Dcx) and polysialic acid neural cell adhesion molecule (PSA-NCAM) (Christie and Cameron, 2006; Duan et al., 2008; Francis et al., 1999; Gage, 2002; Joels et al., 2004; Kronenberg et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2008; Seki, 2002; Seki and Arai, 1993). Next, these immature neurons (type III) mature into granule cell neurons, which express neuronal nuclei (NeuN) (Mullen et al., 1992). The final process required for neurogenesis is the ability of these newly formed neurons to incorporate and function within their environment (Barkho et al., 2006; Cameron and McKay, 2001; Goergen et al., 2002).

Although much is known about neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, its postnatal development has not been as well characterized. Many studies describe characteristics of “adult” stem cells within the dentate gyrus, however, the age at which “adult” is achieved is variable and has been reported to be anywhere from four to twelve weeks postnatal (Bailey et al., 2004; Bastos et al., 2008; Bulloch et al., 2008; Enwere et al., 2004; Goncalves et al., 2008; Kuhn et al., 1996; Lemaire et al., 2000; Molofsky et al., 2006; Tropepe et al., 1997; Wagner et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2009). One purpose of this study was to developmentally profile these progenitors at different ages since the dentate gyrus itself develops almost exclusively during the postnatal period, though critical aspects of its timing beyond the first week remain unclear.

Another important objective of this study was to identify key regulators that maintain neurogenesis in the adult brain. It is known that there are extrinsic factors that influence neurogenesis in the adult brain and participate in the neural stem cell niche (Doetsch, 2003; Riquelme et al., 2008; Tavazoie et al., 2008). These microenvironmental effectors include hormones, neurotransmitters, hypoxia, and trophic and morphogenic factors that are known to play roles in regulating neurogenesis (Barkho et al., 2006; Calof, 1995; Cameron and Gould, 1994; Cameron et al., 1998; Cameron et al., 1995; Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995; Goergen et al., 2002; Heller et al., 1996; Kaneko and Sawamoto, 2008; Kempermann et al., 2003; Kempermann et al., 1997; Kernie et al., 2001; Kronenberg et al., 2006; Muller et al., 1995). In addition, there are neural stem- and progenitor-specific factors that influence neurogenesis and include genes that regulate cell proliferation as well as ones that determine and regulate cell fate decisions. Although several factors have been shown to be involved in proliferation and cell fate, there are others that play mechanistic roles in regulating adult neurogenesis and remain unknown (Abrous et al., 2005).

We hypothesized that specific genes influencing neurogenesis may change over time, and we therefore chose to characterize the postnatal dentate gyrus by creating a developmental profile of neurogenesis at various time points. Neurosphere assays reveal a functional advantage for the progenitors from younger mice, while those from older mice divide more slowly. Furthermore, differentiation assays show that P7 progenitors are more neurogenic than those from P28. We also quantified early hippocampal stem/progenitors expressing GFP in nestin-GFP transgenic mice and demonstrate a progressive decline in the percentage of GFP-expressing progenitors until two months of age. In addition we utilized stereological techniques to determine absolute numbers of different progenitor populations at relevant time points. We then identify with microarray analysis between two different progenitor populations (P7 and P28), candidate genes that may mediate the changes in neurogenic potential that we observe. These results suggest that declining stem/progenitor populations in the hippocampus are in part regulated and maintained by cell-autonomous genetic changes that occur over time.

Materials and Methods

Mice

The Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at UT Southwestern Medical Center approved all animal experiments. Animals were humanely housed and cared for at the Animal Resource Center within UT Southwestern, which is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

The transgenic nestin-eGFP mouse has been described previously and extensively characterized (Bastos et al., 2008; Becq et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2008; Koch et al., 2008). Briefly, a nestin-rtTa-eGFP construct was used to create transgenic animals that express GFP exclusively within the neural tube and the proliferative zones of the dentate gyrus and subventricular zone (SVZ). The second intron of the nestin gene was also included as it contains the neural progenitor-specific enhancer element of the nestin promoter (Zimmerman et al., 1994).

Tissue Culture

Whole hippocampus was dissected from GFP transgenic animals at the indicated time points. The hippocampus was coronally sectioned in 600 µm slices and the dentate gyrus was extracted from all slices. The digestion media consisted of activated papain: 42 µl of papain (Worthington), 27 µl of 100 mM Cystein-HCl and 6 µl of 100 mM EDTA in 425 µl of DMEM/F12. Serum-containing media consisted of 10% FBS in DMEM/F12 with 1% Penicillin/Streptavidin. Neural stem cell media included 1% N2 supplement (Gibco), B27 1:50 (Gibco), 10 µg/µl Heparin, 20 ng/ml bFGF (Sigma) and bEGF (Invitrogen) and 1% antibiotics in DMEM/F12. The semi-solid media used in the neurosphere assays contains 60% neural stem cell media and 40% of 1.6% methylcellulose (Sigma).

In the neurosphere assay, dentate gyri were isolated as explained above. Then they were incubated in activated papain for 20–30 minutes at 37 degrees. After digestion, the papain was inactivated by washing the tissue with DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS. Then a flame-polished Pasteur pipette was used to dissociate the tissue into a single-cell suspension. This suspension was then passed through a 30 µm filter (Partec) and plated at a density of 20 cells/µl in semi-solid media. The total number of cells/well was 20,000 in a 12-well plate.

In neurosphere assays using fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis, dentate gyrus cells were isolated in the same manner however, the single-cell suspension was sorted using a MoFlo cell sorter (Dako). GFP-expressing cells were plated in the same conditions as the dentate gyrus cultures. All cultures were treated with 300 µl of semi-solid medium every three to four days and analyzed 14 days after plating.

To further determine whether neurosphere growth and proliferation was cell-autonomous, GFP-expressing progenitors from P7 and P28 dentate gyri were sorted and plated in 96-well plates with a final density of one cell/well. Neurospheres were cultured in neural stem cell media for 14 days and then quantified.

For the differentiation assay dentate gyri were microdissected from P7 and P28 transgenic animals and plated in neural stem cell media. Once neurospheres began to form, they were collected, washed and dissociated with acutase for five minutes at 37 degrees. Cells were then replated on coated chamber slides in differentiation media (1% serum in DMEM/F12) and allowed to differentiate for five days. The media was replaced on the third day. After five days in culture chamber slides were immunohistochemically labeled for analysis.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were perfused and their brains were removed and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde. After embedding in agarose, brains were cut into 50 µm sections using a Leica vibratome machine and every sixth section was used for immunostaining. Sections were first washed three times in 0.3% TritonX in PBS and then blocked for one hour at room temperature in 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) in 0.3% TritonX PBS. All fluorescent antibodies were mixed together and incubated for two hours at room temperature in their appropriate dilutions in a total volume of 500 µl of 5% NDS in 0.3% TritonX PBS. Tissues were then washed three times with 0.3% TritonX PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies for two hours. Slices were then washed two times with 0.3% TritonX PBS and two times with PBS. Tissue sections were placed onto glass slides, mounted with Immu-Mount and covered with plastic cover slips. Images were obtained using confocal microscopy (Zeiss, LSM 510).

For the developmental profile, the following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-GFP 1:500 (Molecular Probes), mouse anti-NeuN 1:500 (Chemicon) and goat anti-DCX 1:200 (Santa Cruz). Staining of the SVZ and SGZ used chicken anti-GFP 1:500 (Aves Labs) and rat anti-platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) 1:250 (BD Pharmingen) antibodies.

Differentiated cells attached to the chamber slides were stained with mouse anti-neuron-specific class III beta-tubulin (TUJ-1) 1:2000 (Covance) and rabbit anti-GFAP 1:2000 (Invitrogen) to identify neurons and astrocytes, respectively. Cells were also stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) 1:1000 (FLUKA) to label the nucleus.

Staining for design-based stereological counting was performed on 50 µm vibratome sections (described above). Sections were stained and incubated in primary antibodies overnight (to maximize antibody penetration) and were treated with biotinylated secondary antibodies followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-based Vectastain ABC Kit (Vector Laboratories). Incubation with 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) substrates was used to amplify and visualize the staining according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Vector Laboratories). Primary antibodies used include rabbit anti-GFP 1:500 (Invitrogen), goat anti-DCX 1:100, and rat anti-5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU) 1:400. All secondary antibodies used a concentration of 1:350 and were purchased from Vector Laboratories.

GltI immunostaining utilized the chicken anti-GFP antibody as well as mouse anti-GFAP 1:100 (BD Pharmingen), goat anti-DCX 1:200 (Santa Cruz), and guinea pig anti-glial high affinity glutamate transporter (GltI) 1:200 (Chemicon). All secondary antibodies used were in a final concentration of 1:200. GFP and BrdU co-localization studies used rabbit anti-GFP 1:500 and rat anti-BrdU 1:400 (Abcam) primary antibodies. Fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:200) were used to visualize the staining.

Western Blots

Whole cell lysates were isolated from P14 dentate gyri for PDGFRα and GFP immunoblotting (Fig. 2, L). An 8% polyacrylamide gel was used for PDGFRα blotting while a 12% gel was run for GFP immunoblotting. Antibodies used include rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes), rat anti-PDGFRα (BD Pharmingen), and rabbit anti-β-tubulin (Sigma). All primary antibodies were used at a concentration of 1:1000. All secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz, raised in goat serum and used at a dilution of 1:5000.

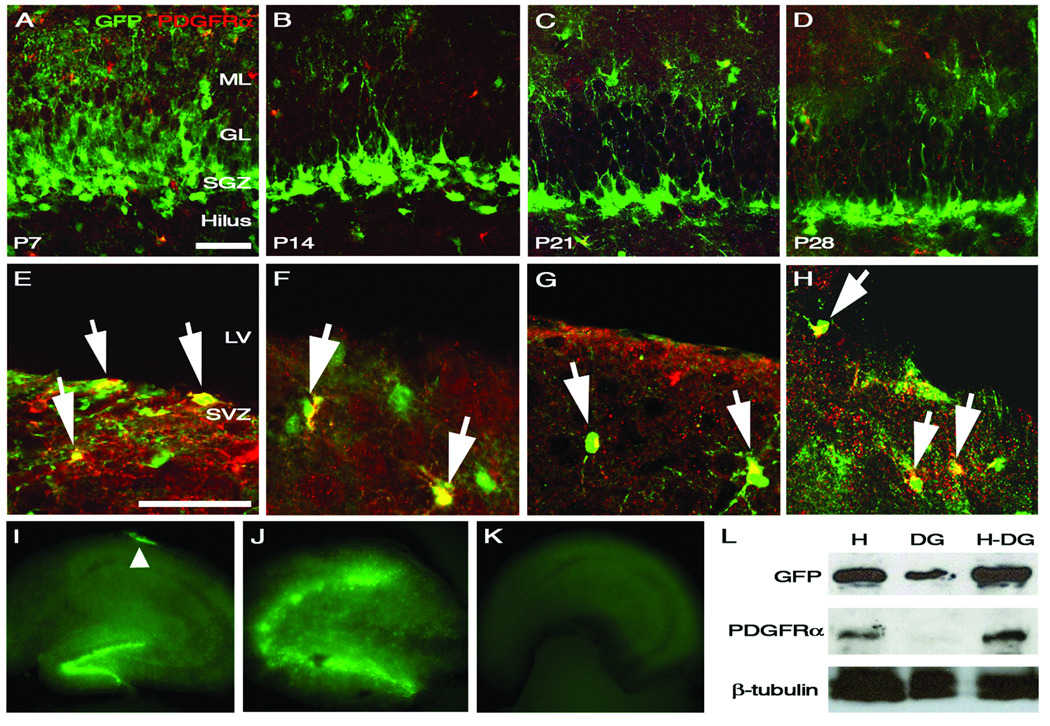

Figure 2.

Isolation of PDGFRα-negative neural progenitors. In order to distinguish between GFP-positive progenitors from the dentate gyrus and SVZ, PDGFRα expression was utilized to mark oligodendrocytes precursors in P7, P14, P21, and P28 mice. (A–D) shows a lack of GFP and PDGFRα co-expression within the SGZ. However, cells expressing both markers in (E–H) (yellow cells) are found within the SVZ of the lateral ventricle (arrows). In (I–K) transgenic whole mount tissue of the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, and the hippocampus without the dentate gyrus are pictured. The arrowhead in (I) highlights GFP-expressing neural progenitors from the lateral ventricle. Western blot analysis of GFP and PDGFRα protein expression in various parts of the hippocampus confirms that neural progenitors exclusively from the dentate gyrus were isolated. Scale bars in (A) and (B) are 50 µm each. Abbreviations: ML=molecular layer; GL=granular layer; SGZ=subgranular zone; LV=lateral ventricle; H=hippocampus; DG=dentate gyrus; H-DG=hippocampus with dentate gyrus removed.

For GltI immunoblotting lysates were extracted from P7 and P28 dentate gyri and from P14 cortex, hippocampus, dentate gyrus, and hippocampus without the dentate gyrus (Fig. 6, B). Protein was loaded on a 10% polyacrylamide gel for both blots. Antibodies used include guinea pig anti-GltI (Chemicon) at 1:5000 and rabbit anti-β-tubulin (Sigma) at 1:1000. Again, both secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz and used in a dilution of 1:5000.

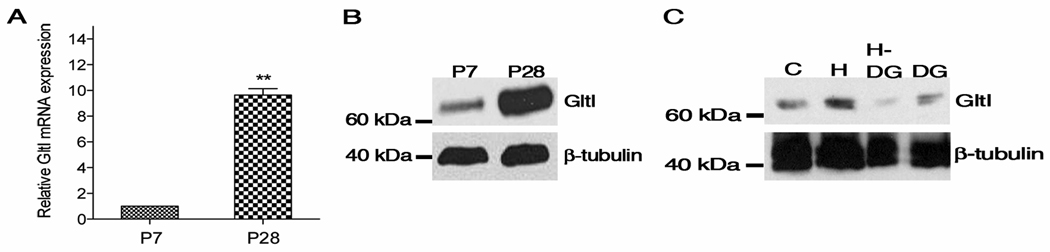

Figure 6.

GltI mRNA and protein levels confirm microarray results. (A) Using qPCR, relative GltI mRNA levels are up-regulated in P28 GFP-expressing cells while (B) GltI protein levels are also elevated in lysates extracted from microdissected dentate gyrus. Widespread distribution of GltI protein throughout P14 lysates is observed in (C). Abbreviations: C=Cortex; H=hippocampus; DG=dentate gyrus; H-DG=hippocampus with dentate gyrus removed. Statistical analysis in (A) was done using an unpaired t-test (**p=0.001–0.01).

Protein concentrations were all measured using a Bradford Assay. For all gels 20 µg of protein were loaded per well. After the gels were run, protein was transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk for one hour at room temperature. Primary and secondary antibodies were incubated for two hours at room temperature. Membranes were washed with PBS with 1% Tween. Protein bands were visualized using a Lumi-Light Western Blotting Substrate Kit from Roche followed by development.

Flow Cytometry

Dentate gyrus was microdissected from the hippocampus at the indicated time points. For quantification of GFP-expressing progenitors, fresh tissue was homogenized in DDP (20 µl DNase I, 2 ml 10× Dispase II, 10 ml 2× Papain in 20 ml F12/DMEM) and incubated at 37 degrees Celsius for 20 minutes. After incubation, tissue was triturated 100× with a pipette into a single-cell solution. Cells were spun down for 30 seconds at 16,000 rpm and washed with F12/DMEM containing 10% FBS three times. Then cells were resuspended in the same media and passed through a 70 µm filter (BD Biosciences). 10 minutes before analysis propidium iodide (PI) was added to each sample to identify dead cells (1:1000).

Cell sorting was done using a MoFlo machine from Dako. GFP-expressing and GFP-negative cells were collected and the percent GFP-positive cells were calculated from the total number of collected cells. The negative control was non-transgenic hippocampus. Population purity was analyzed by sorting GFP-expressing and GFP-negative cells onto a glass slide and looking at their fluorescence using a fluorescent microscope (Data not shown). No less than six mice were used per sorting sample at each age. Experiments were performed in triplicate and error bars represent standard deviation. Significance was determined using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post-hoc analysis for a p value level less than 0.1% (***p<0.001).

Microarray analysis was performed using validated methods and protocols developed by Miltenyi Biotec (Auffray et al., 2007; Landgraf et al., 2007). Briefly, at least 500 P7 and P28 GFP-expressing cells were independently collected from FAC-sorting and lysed at 42 degrees according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). Cells were shipped on dry ice to Miltenyi Biotec where the RNA was extracted and cDNA was amplified in a linear fashion using PCR. Equal cDNA amounts were spotted in quadruplicate on a Stem Cell-Specific Array consisting of 916 genes enriched in various stem cells. Sample collection and microarray analysis were completed in triplicate and candidate genes were significantly up or down regulated in all three trials. Genes were considered significantly up or down regulated if their expression levels were 1.7-fold higher or 0.58 fold lower compared to the P7 control, respectively. Prior to analysis baseline expression levels were analyzed and normalized to account for initial differences in gene expression.

Real-Time PCR was performed on FAC-sorted cells in order to determine relative GltI mRNA levels. Total RNA was extracted from P7 and P28 GFP-expressing cells and was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). All Real-Time PCR reactions were performed in a 20 µl volume that included amplified cDNA, SYBR Green dye (Roche), 2.5 µM GAPDH (as an internal control), and GltI real-time PCR primers. The primer information is as follows: GAPDH forward: 5’-CTC AAC TAC ATG GTC TAC ATG TTC CA-3’; GAPDH reverse: 5’-CCA TTC TCG GCC TTG ACT GT-3’; GltI forward: 5’-GGA AGA TGG GTG AAC AGG C-3’; GltI reverse: 5’-TTC CCA CAA ATC AAG CAG G-3’. Real-Time quantification was analyzed on the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System software.

Cell Quantification

Differentiated cells were quantified based on TUJ-1 and GFAP expression. An Olympus BX50 microscope and Photometrics CoolSNAP camera were used. The software used for imaging was MetaVue by Molecular Devices. Images of DAPI, TUJ-1 and GFAP expression were captured and merged to determine co-localization. At least 200 cells were analyzed per sample and each time point was done in quadruplicate. Statistical significance was analyzed using an unpaired t-test (***p<0.001).

Stereological quantification was performed on an Olympus BX51 System Microscope with a MicroFIRE A/R camera (Optronics). The Optical Fractionator Probe within the Stereo Investigator sotftware (MBF Bioscience, MicroBrightField, Inc.) utilized an unbiased counting frame(Gundersen, 1980; West, 1993)and was used to quantify cell number. Counting was performed using a 100× oil immersion lens. At least 200 cells were counted (per animal) and the average number of counting fields examined was close to 300. The average number of sections counted was 10 while the average mounted thickness after processing was approximately 35 µm.

In order to reduce bias between samples, a number of measures were undertaken. All tissue was processed in the same manner (see Immunohistochemistry methods above). Furthermore, to decrease the effect of shrinkage on our tissues, we used a height sampling fraction of 30 µm to account for actual tissue thickness observed after processing. The area-sampling fraction for DCX- and GFP-expressing cells was 1/8. BrdU quantification required an area-sampling fraction of one. Every sixth section (the section sampling fraction) was used to quantify cell populations within the SGZ and granular layer of the dentate gyrus. Furthermore, slides were only quantified if all sections were present and homogenously stained. The coefficient of variance for each animal quantified was always less than 15%.

Confocal microscopy was used to quantify the number of BrdU and GFP double positive cells within the SGZ and granular layer of the dentate gyrus. As described elsewhere [Miles, 2008 #87][Yu, 2008 #88], a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscopy utilizing Argon 488 and He 633 lasers was used to quantify double-labeled cells on a Zeiss Neofluar 40×/1.3 oil lens. Focusing through the z-axis of each cell was done to ensure only precisely colocalized signals were quantified. Slides were only analyzed if antibody penetration and signal intensity between sections was consistent. Every sixth section was stained as described and all BrdU-expressing cells within the SGZ and granular layer of the dentate gyrus were analyzed for their co-localization with GFP. Percentages were calculated based on the ratio of double-labeled cells to those only expressing BrdU.

Statistics were calculated using one-way ANOVA for overall signficance followed by Bonferonni post-hoc analysis to determine significance between multiple groups: ***p<0.001, **p=0.001–0.01 and *p=0.01–0.05.

Results

Developmental profile of the postnatal dentate gyrus

Dentate gyrus progenitors express a variety of well known markers throughout their ontogeny. We have previously characterized these subsets of progenitors using transgenic mice that we developed and have also used these mice to distinguish mature astrocytes from GFAP-expressing type I dentate gyrus progenitors. Although both express GFAP, GFP-expressing progenitors lack expression of glutamine synthetase (GS), a mature astrocyte marker(Miles and Kernie, 2008)Furthermore, after hypoxic-ischemic and traumatic brain injury, reactive astrocytes lack expression of GFP, while GFP-expressing progenitors lack expression of GS(Miles and Kernie, 2008; Shi et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2008). We have therefore demonstrated that GFP is expressed in GFAP-expressing type I progenitors but not in mature astrocytes. Here, we used this same transgenic to determine how other genetic characteristics change over time.

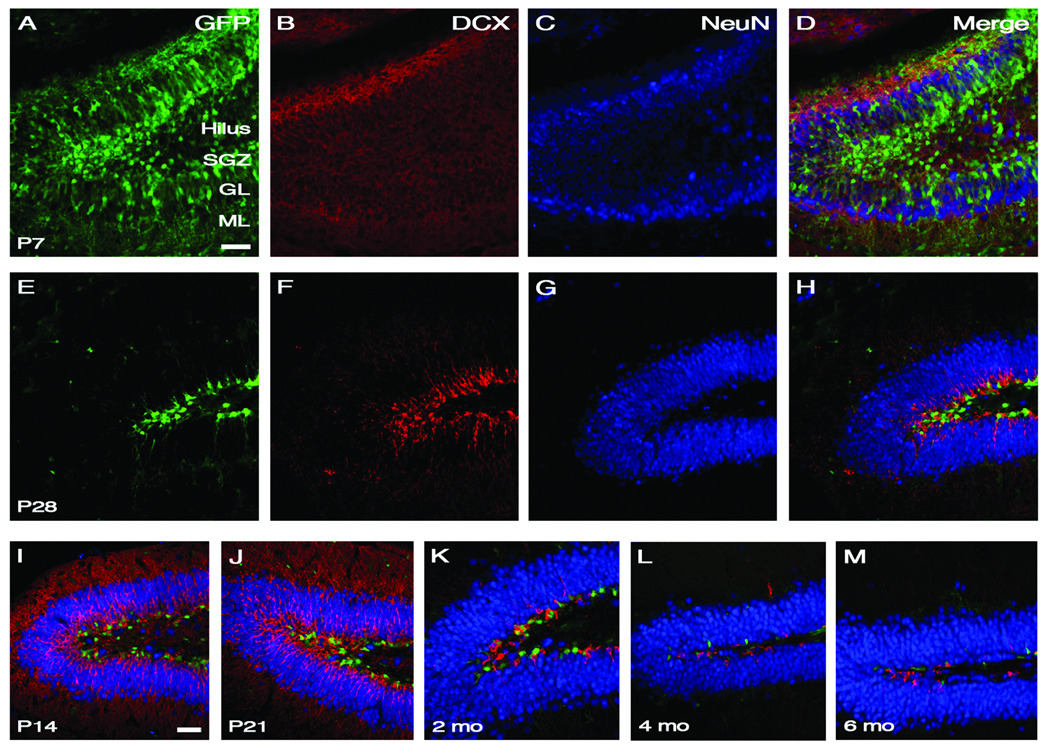

We first performed immunostaining to examine the progenitor cell types present in mice at various ages. Anti-GFP antibody was utilized to identify type I and type II progenitor populations whereas anti-DCX was used for later neural progenitors (type III) and anti-NeuN was used to identify mature neurons (Joels et al., 2004; Limke and Rao, 2003; Mullen et al., 1992). Mice at various ages were analyzed to encompass most stages of dentate gyrus development: postnatal days 7, 14, 21, 28, two months, four months, and six months. Results demonstrate that the number of GFP- and DCX-expressing cells decrease as the mice age (Fig. 1). In particular we observed a steady decline in GFP-expressing cells until about two months of age at which time the population appeared to stabilize.

Figure 1.

Developmental profile of the postnatal dentate gyrus. GFP, DCX, and NeuN markers were used to represent various cell types within the dentate gyrus during the course of postnatal development. Staining with GFP identifies early type I and II neural progenitors that have been labeled with the Nestin-eGFP transgenic mouse while DCX labels type III later progenitors and NeuN marks mature neurons. Panels (A–D) are from P7 transgenic mice and (E–H) correspond to P28 mice. Merged images are dentate gyri from P14, P21, 2 month, 4 month and 6 month old animals can be seen in (I–M). An age-dependent decline in the number of GFP-expressing progenitors occurs during the course of development. However, this progenitor population appears to stabilize at two months of age. Scale bars in (A) and (I) are 50 µm. Abbreviations: SGZ=subgranular zone; GL=granular layer; ML=molecular layer.

Dentate gyrus dissections are exclusive of GFP-expressing progenitors from the SVZ

The hippocampus is contiguous with the subventricular zone (SVZ) and gross hippocampal dissection results in a mixed population of both dentate gyrus and SVZ progenitors (Becq et al., 2005; Seaberg and van der Kooy, 2002; Tonchev and Yamashima, 2006). Before the various progenitor populations could be quantified, we needed to ensure exclusive isolation of GFP-expressing cells from the SGZ of the dentate gyrus and not from the SVZ of the lateral ventricle. To do this, we took advantage of the differential expression patterns of platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) in the SVZ and the SGZ. If our dissection methods were exclusive of SVZ progenitors, then we would not expect to see PDGFRα expression in the dentate gyrus since GFP-expressing cells from the SVZ also co-express PDGFRα (Jackson et al., 2006).

Immunostaining of the SVZ and SGZ for GFP and PDGFRα was carried out to determine progenitor specificity. Merged confocal images show GFP and PDGFRα co-localization in the SVZ but not in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus (Fig. 2, A–H). These results suggest that there are limited GFP-expressing SVZ neural progenitors mixed in with isolated dentate gyrus cells. Furthermore, hippocampal whole mounts were prepared and visualized using a fluorescent microscope and we demonstrate GFP-expressing cells in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus and along the CA1 region of the hippocampus (Fig. 2, I). The dissected dentate gyrus, however, only consists of GFP-expressing cells from the SGZ and not from the SVZ (Fig. 2, J). To further confirm these findings, whole cell lysates from P14 hippocampus and dentate gyrus were isolated and blotted for the presence of GFP and PDGFRα. As expected there was no detectable PDGFRα protein in the dentate gyrus lysates (Fig. 2, L).

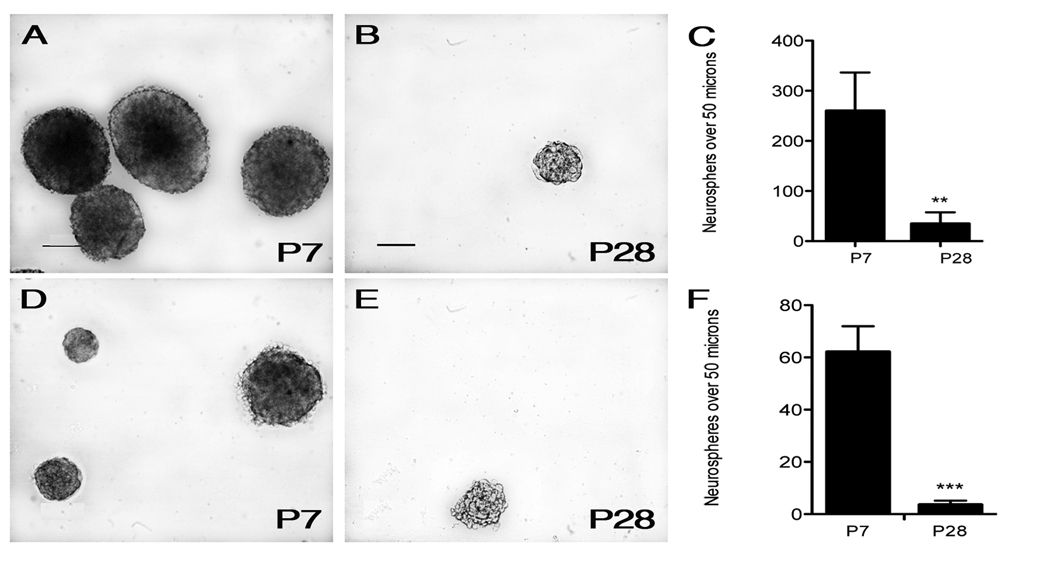

In vitro neurosphere assays suggest cell-autonomous differences between P7 and P28 progenitors

Due to the morphological differences between progenitor populations, we hypothesized that P7 and P28 progenitors would respond differently when cultured in vitro. To test this, cells were dissociated from P7 and P28 dentate gyrus and cultured at a density of 20 cells/µl and allowed to form neurospheres. To analyze the ability of the cultures to grow and proliferate, we counted the number of neurospheres present in each culture and measured their diameter 14 days after plating. We further assessed the number of neurospheres that were larger than 50 µm. The P7 progenitors were more proliferative and more easily formed neurospheres than the P28 progenitors (Fig. 3, A and B). Furthermore, there were more neurospheres that were at least 50 µm in diameter. The P7 dentate gyrus cultures had an average of 260 neurospheres over 50 µm while the P28 cultures only saw an average of 35 neurospheres of at least 50 µm (Fig, 3, C). These results suggest a functional difference between the P7 and P28 progenitor populations.

Figure 3.

Cell-autonomous factors affect progenitor growth and differentiation. To determine the growth phenotype of progenitors from P7 and P28 mice, neurosphere assays were used to quantify the number of neurospheres (over 50 µm)formed in culture. Representative pictures and quantification of neurospheres formed from the whole dentate gyrus (A–C) and GFP-positive FAC-sorted cells (D–F) are depicted. P7-derived neurospheres seem to have a growth advantage compared to cultures from P28 progenitors. This phenotype is observed in both a cell-autonomous (D–F) and non cell-autonomous fashion (A–C). Scale bars in (A) represents 50 µm. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t-test: ***p<0.001 and **p=0.001–0.01.

We next wanted to test whether the proliferative differences observed were in fact cell-autonomous and not influenced by differing densities of progenitors at these ages or extracellular cues from adjacent cell types. We therefore used flow cytometry to sort GFP-expressing cells from microdissected P7 and P28 dentate gyrus and repeated the neurosphere assay while maintaining a density of 20 cells/µl. Again we observed a significant difference between neurospheres cultured from P7 and P28 GFP-expressing cells (Fig. 3, D and E). Sorted GFP-expressing cells from P7 animals formed an average of 62.1 neurospheres per well that exceeded 50 µm while P28 progenitors produced 3.6 neurospheres per well (Fig. 3, F).

To further confirm that differences in growth and proliferation between P7 and P28 progenitors were due to cell-intrinsic factors, we performed a single-cell proliferation assay. Progenitors were sorted and plated at a density of one cell per well in a 96-well plate. After 14 days of culturing, no neurospheres of any size were derived from P28 progenitors in four different experiments. However, the P7 progenitors produced an average of 3 neurospheres per 96 well plate demonstrating that only single-cells sorted from the P7 hippocampus are capable of cell-autonomous self-renewal (not shown).

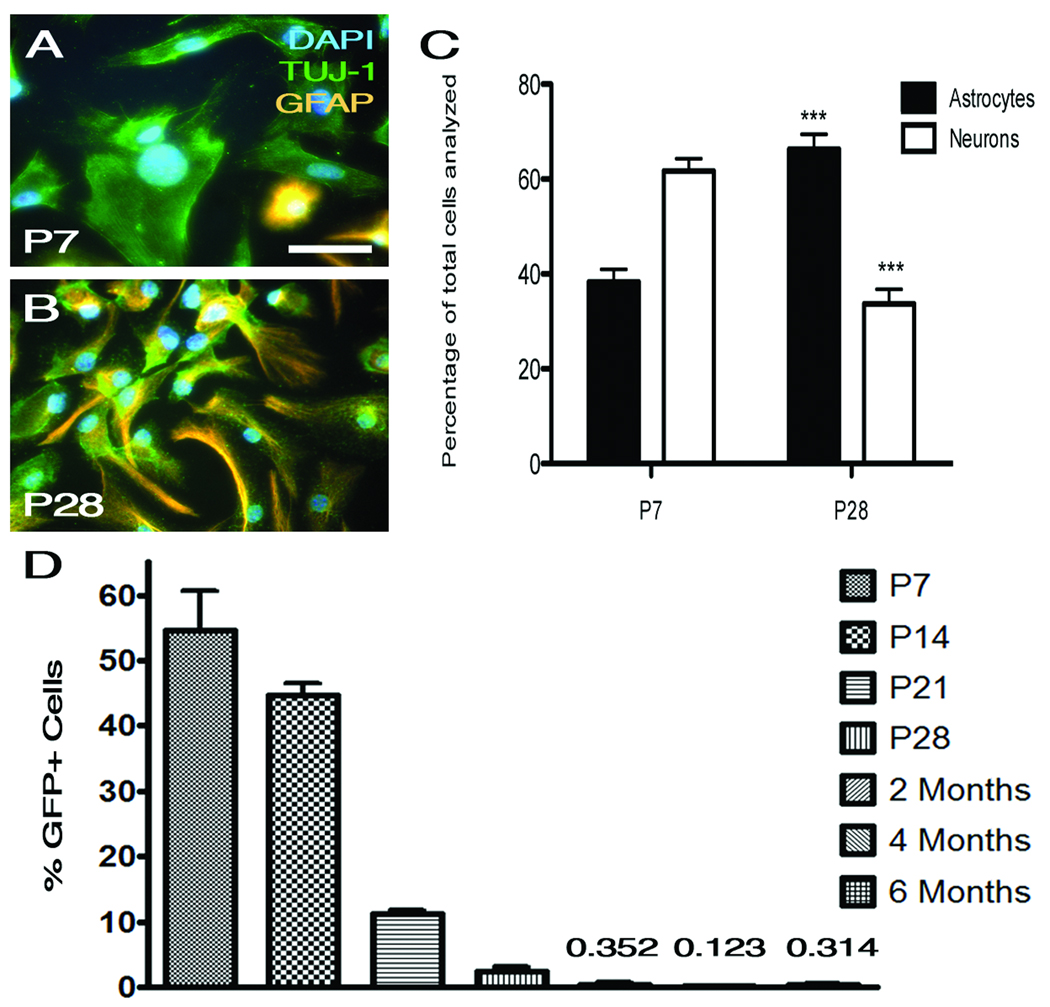

In vitro differentiation suggests that P7 progenitors are more neurogenic than those from P28

To determine the potential of progenitor cells to differentiate into neurons, primary neurospheres from P7 and P28 dentate gyrus were plated in serum for five days and then stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), GFAP, and TUJ-1 to distinguish neurons (expressing TUJ-1) from astrocytes and undifferentiated progenitors (expressing GFAP). Progenitors from P7 mice preferentially differentiated into neurons (61.7%) while most P28 progenitors became astrocytes or remained undifferentiated (66.3%) (Fig. 4, C). The percentage of GFAP-expressing cells and neurons observed were extremely significant when the two time points were compared (p<0.001). More than 99% of cells observed expressed either GFAP or TUJ-1. This suggests that under these culture conditions, progenitors rarely differentiate into oligodendrocytes.

Figure 4.

In vitro differentiation and quantification of GFP-expressing neural progenitors suggests early adulthood senescence. (A) and (B) illustrate representative images of differentiated cells derived from P7 and P28 progenitors, respectively. (C) Quantification of TUJ-1- and GFAP-expressing cells suggests that P7 progenitors preferentially mature into neurons while most P28 progenitors differentiate into astrocytes. The percentages of astrocytes and neurons are significant when P7 is compared to P28 (***p<0.001) (D) The percent of GFP-expressing cells separated by flow cytometry declines over the course of development and begins to stabilize at two months of age. This suggests that adulthood senescence may occur around two months of age in mice as indicated by the stabilized progenitor population preceding this developmental time point. Statistical analysis utilized ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni correction. P7 and P14 are significantly different from all other samples but are not statistically different from one another (***p<0.001). Error bars represent standard deviation and the scale bar (A) is 50 µm. Abbreviations: DAPI=4', 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; TUJ-1=neuron-specific class III beta-tubulin.

Quantification of GFP-expressing neural progenitors suggests early adulthood senescence

To further characterize the diminishing progenitor cell population, we used fluorescent activated cell sorting of the GFP-expressing cells to quantify the progenitor population at each postnatal time point. Interestingly, the P7 and P14 dentate gyrus had the highest percentage of progenitor cells and were statistically much higher when compared to all other time points (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4, D). Populations from older mice (two months, four months and six months) all exhibit similar percentages that were not statistically different from one another. Furthermore, there was about a 27-fold difference between the P7 and P28 progenitor populations. These quantification data support our observations from immunostaining and further demonstrate a steady decline in GFP-expressing early progenitors until about two months of age. These results suggest that adulthood senescence may occur around two months of age as indicated by the stabilized progenitor population preceding this developmental time point.

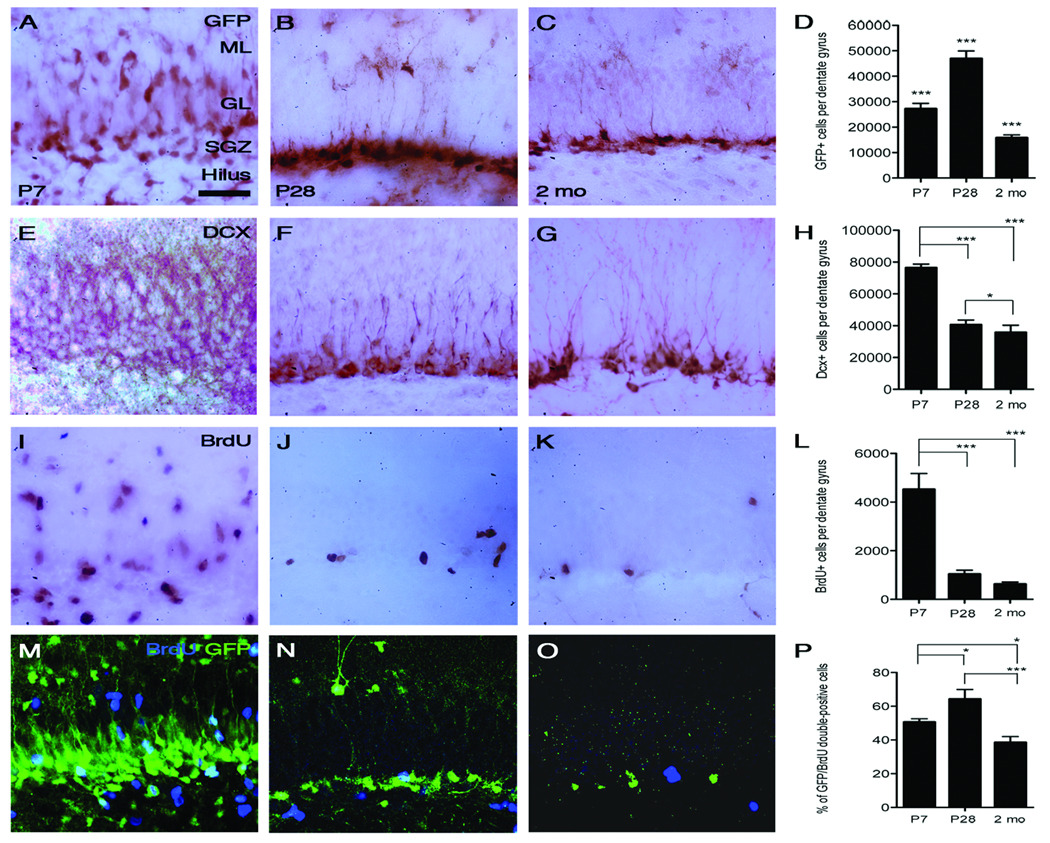

Design-based stereology of GFP-, DCX- and 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-expressing cells indicate age-dependent changes in cell number

In order to more closely analyze different progenitor populations within the dentate gyrus, design-based stereology and 3,3'-diaminobenzidine (DAB) immunohistochemistry was utilized to estimate the number of early progenitors (GFP-positive), late progenitors (DCX-positive), and BrdU-positive cells per dentate gyrus in P7, P28 and 2 month old transgenic mice. The total number of GFP-expressing cells was significantly different for each age group, with the highest absolute number in P28 animals. P7 animals had an average of 27,000 positive cells per dentate gyrus, while P28 animals had nearly double this number at 47,000 positive cells and 2 month old animals had approximately 16,000 (Fig. 5, D). One-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferonni post-hoc analysis determined that all three groups were significantly different from one another.

Figure 5.

Significant age-dependent changes in progenitor cell number. To better assess different progenitor populations within the dentate gyrus, dual immunofluorescence and design-based stereological methods were utilized. Representative pictures and quantifications of DAB histology of GFP (A–D), DCX (E–H) and BrdU (I–L) are shown as well as GFP and BrdU immunofluorescence (M–P). GFP staining seems to decrease with age (A–D), although P28 animals have a significantly increased number of GFP-expressing cells compared to the other time points quantified (D). Unlike type I and type II progenitors, the number of DCX-expressing type III progenitors remains highest in younger animals (E–H). BrdU expression (I–K) and cell number (L) are also significantly increased in P7 animals compared to P28 and 2-month old animals. Although GFP and BrdU immunofluorescence decrease with age (M–O), the percent of double-labeled cells is highest in P28 animals when compared to P7 and 2-month old transgenic animals (P). Significance was determined by ANOVA followed by Bonferonni post-hoc analysis. P values for GFP, DCX, BrdU, and double-labeling quantification are significant: ***p<0.001, **p=0.001–0.01 and *p=0.01–0.05. Error bars represent standard deviation and the scale bar in (A) represents 50 µm. Abbreviations: ML=molecular layer; GL=granular layer; SGZ=subgranular zone.

The number of DCX-expressing cells, however, decrease over time where there were approximately 76,000 at P7, this decreased to 40,000 at P28 and 36,000 at 2 months of age (Fig. 5, H). Unlike early type I and II progenitors that express GFP, The highest number of DCX-expressing cells is observed in younger (P7) mice while estimates at P28 and 2 months are not significantly different from one another. Similar to DCX staining, BrdU-positive cells were more numerous in P7 animals compared to P28 and 2 month olds. P7 animals had an average of 4,522 positive cells per dentate gyrus while P28 animals and 2-month old animals had 1,000 and 628 cells, respectively (Fig. 5, L).

Finally, in order to assess the percentage of GFP-expressing cells that are actually dividing in P7, P28, and 2-month old transgenic mice, dual-labeling immunofluorescence with GFP and BrdU was performed. Confocal analysis revealed that P7 mice injected with a two-hour pulse of BrdU demonstrated co-localization between GFP and BrdU approximately 50% of the time (Fig. 5, P). This number increased in P28 animals with 64% co-localization and was lowest in 2-month old animals at 38% (Fig. 5, P). This data can therefore be extrapolated to the number of GFP-expressing cells within the dentate gyrus (Fig. 5, I–L). Although the total number of BrdU-expressing cells is highest at P7 (Fig. 5, L), the percentage of GFP- and BrdU-labeled cells is highest at P28. The proportion of GFP-expressing early progenitors to DCX-expressing late progenitors is higher in P28 animals compared to P7 (Fig. 5, D and H). High numbers of DCX-positive cells in P7 animals (Fig. 5, F) may contribute to the decreased percentage of GFP- and BrdU-dual-labeled cells (type I and II progenitors) compared to P28 animals. This suggests that the increased percentage of GFP- and BrdU-labeled cells observed at P28 (Fig. 5, P) may be due to decreased numbers of DCX-positive cells at P28 and 2 months of age (Fig. 5, H).

Microarray analysis reveals differentially expressed genes between P7 and P28 progenitor populations

Results from the neurosphere assays suggest there are cell-autonomous factors that regulate a progenitor’s ability to proliferate and form neurospheres. Furthermore, the vast differences observed during the quantification of these progenitor populations at various developmental time points implies a role for intrinsic factors. We therefore hypothesized that differential gene expression may be involved in regulating and maintaining these hippocampal stem/progenitor cells. To identify these differences, we performed triplicate microarray analysis on P7 and P28 GFP-expressing dentate gyrus progenitors that were collected with FAC-sorting. Candidate genes were identified based on their significant up- or down-regulation (in all three trials) compared to the P7 controls.

This stringent analysis revealed nine candidate genes, three down-regulated and six up-regulated in P28 progenitors compared to the P7 controls. The candidate genes and their known functions are shown in Table 1. These results suggest the presence of a few differentially expressed genes which may be involved in regulating or maintaining the neural progenitor cells at various developmental time points. The genes presented in Table 1 make for a small list, though this was generated using very stringent criteria. In fact, many more genes were identified that are also differentially regulated and these have been deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and may be viewed using the following GEO Series accession number GSE15085 at the NCBI website: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE15085

Table 1.

Microarray Candidate Genes

| GENE | AVERAGE RATIO |

KNOWN CELLULAR FUNCTIONS |

|---|---|---|

| Downregulated compared to P7 | ||

| Cluster of Differentiation 47 (CD47) | 0.217 | Cell adhesion |

| Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan 2 (CSPG2) | 0.24 | Cell adhesion and development |

| T-box 5 (Tbx5) | 0.49 | Transcriptional regulator |

| Upregulated compared to P7 | ||

| Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) | 4.35 | Regulator of lipid metabolism |

| Claudin 10 (Cldn10) | 5.75 | Cell adhesion |

| Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter (Eaat2/GltI) | 9.77 | Glutamate transport |

| Gap Junction Protein 4 (Gja4) | 6.62 | Gap junction protein |

| Glypican 4 (Gpc4) | 4.31 | Cell proliferation and morphogenesis |

| Vitronectin (Vtn) | 7.32 | Cell adhesion and immune response |

GltI expression patterns confirms microarray data

The glutamate transporter GltI was found to be the most highly up-regulated gene in P28 progenitors. We validated this finding using a variety of methods. Relative GltI mRNA levels were detected in sorted GFP-expressing cells from P7 and P28 animals (Fig. 6, A). We demonstrate that GltI mRNA levels are an average of 9.65 fold higher in the P28 sample when normalized to the P7 sample. This result is consistent with our microarray data in which GltI was up-regulated in P28 cells by a factor of 9.77 when compared to the P7 control (Table 1).

To validate protein expression, Western blot analysis was carried out on whole cell lysates extracted from P7 and P28 dentate gyri. GltI protein levels are elevated in the P28 lysates compared to those from P7 (Fig. 6, B). In addition, GltI expression patterns in P14 lysates derived from various parts of the brain demonstrate its relatively specificity to the dentate gyrus though it is also found in the cortex and other parts of the hippocampus (Fig. 6, C).

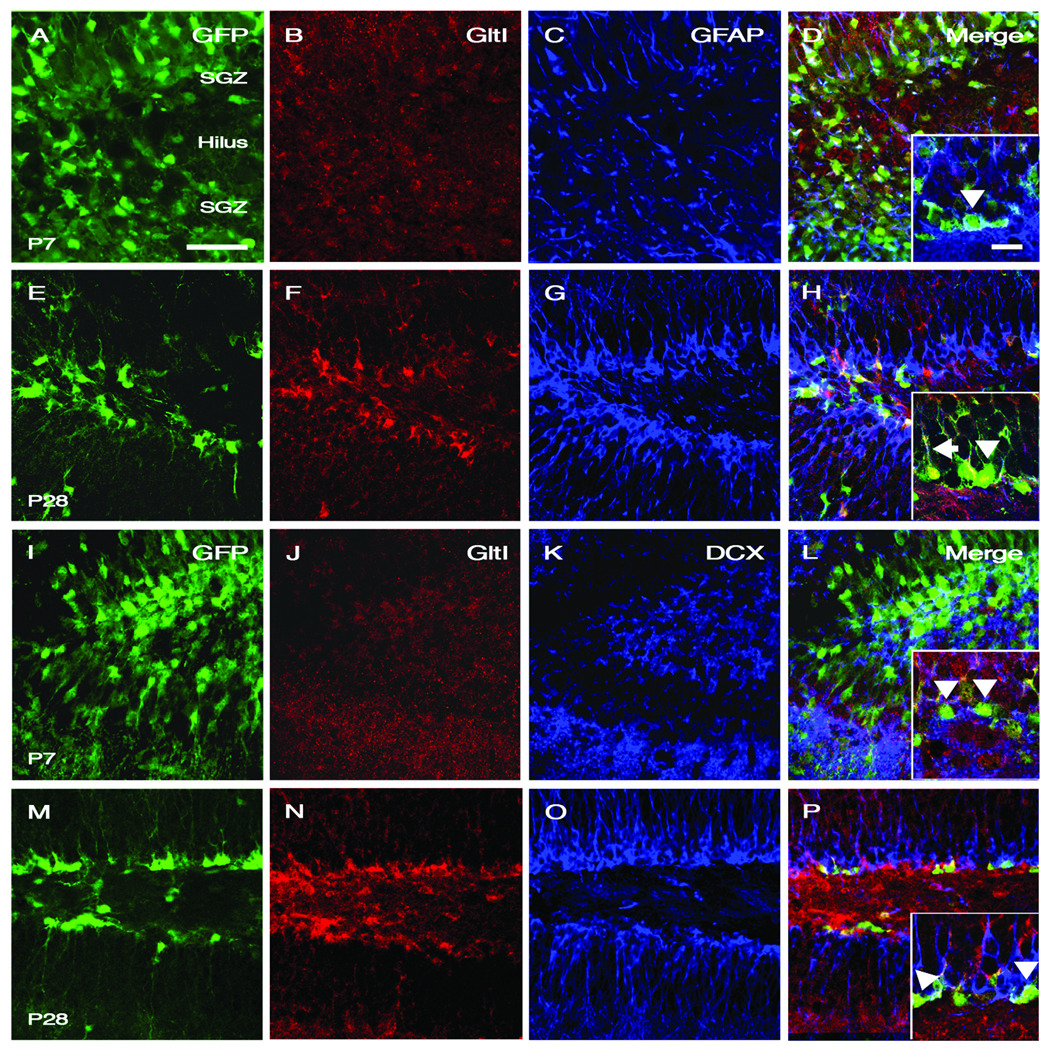

GltI is expressed in early but not late progenitors within the SGZ

Since there are several progenitor subtypes within the dentate gyrus, we wanted to determine whether GltI expression was specific to the early stem/progenitor population. Therefore, the cell-specificity of GltI expression was ascertained by performing immunostaining on P7 and P28 dentate gyrus. Consistent with the microarray data, GltI protein becomes increasingly evident on P28 GFP-expressing progenitors and is barely expressed at P7 (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the majority of GFP- and GltI-expressing cells also co-localize with GFAP indicating that GltI is found in early type I progenitors (Fig. 7, H). However, DCX did not co-localize with GFP- and GltI-expressing cells. These data confirm that GltI is not found on late (type III) neural progenitors (Fig. 7, P) and is specific to early stem/progenitor population of the P28 dentate gyrus.

Figure 7.

GltI colocalizes with GFAP-expressing type I progenitors but is not found on DCX-expressing type III neural precursors. In vivo immunofluorescence of GFP, GltI, and GFAP within the SGZ of P7 (A–D) and P28 (E–H) animals demonstrate that GltI is found on type I neural progenitor cells. The high magnification image within (D) illustrates co-localization between GFP and GFAP-expressing cells (arrowhead) while only background levels of GltI are present. In (H) GltI levels are elevated and colocalize with both GFP and GFAP (arrow). However, not all GFP and GltI double-positive cells express GFAP (H, arrowhead). DCX is not expressed on cells labeled with both GFP and GltI (P, arrowhead) and some GFP-expressing cells lack DCX expression altogether (L, arrowhead). Therefore, lack of co-localization between DCX and GltI in both P7 (I–L) and P28 (M–P) animals indicates GltI’s absence from later type III progenitors. Scale bar in (A) is 50 µm while scale bar within the inset picture (D) is 35 µm. SGZ=subgranular zone.

Discussion

This study demonstrates intrinsic differences between young and old progenitors within the developing dentate gyrus and suggests that these differences may underlie their proliferative and differentiation potential. It is well known that the ability of neural progenitors in the dentate gyrus to self-renew and proliferate declines with age. Several groups have used BrdU incorporation and markers of newborn neurons to quantify neurogenesis and progenitor proliferation in the dentate gyrus of rats (Heine et al., 2004; Kuhn et al., 1996; McDonald and Wojtowicz, 2005; Rao et al., 2006). Furthermore, expression patterns of various genes such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), insulin growth factor1 (IGF1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been linked to age-related decreases in neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus (Buckwalter et al., 2006; Hattiangady et al., 2005; Shetty et al., 2005). In addition, regulation of caspase activity in neurogenic regions of the brain also influences postnatal neurogenesis (Gemma et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2009). These studies, however, mainly demonstrate how the neurogenic niche changes over time and do not suggest cell-specific changes in gene expression that occur in the actual stem/progenitor population itself.

Similar to embryonic neurogenesis, early postnatal neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus occurs in three stages (Li and Pleasure, 2007; Nakai and Fujita, 1994). During the development of the dentate gyrus, the primary dentate neuroepithelium located near the ventricular zone, is the site where the dentate precursor pool begins to proliferate, expand and form the first granular cells (Altman and Bayer, 1990; Frotscher et al., 2007; Fujita, 1962; Fujita, 1963; Li and Pleasure, 2007). Then the secondary dentate matrix is formed and serves as the scaffold for what is to become the granular layer of the dentate gyrus (Altman and Bayer, 1990; Frotscher et al., 2007; Fujita, 1964; Li and Pleasure, 2007). By E13.5, cells within the secondary matrix are very proliferative and migrate to the nascent dentate gyrus and by E17.5, the tertiary matrix forms within the future hilus and progenitors and granule cell populations begin to mix and migrate to the limbs of the dentate gyrus (Altman and Bayer, 1990; Li and Pleasure, 2007). Finally, the granule cell layers are condensed and the neural progenitors become aligned with the SGZ (Altman and Bayer, 1990; Li and Pleasure, 2007). The peak of granular cell neurogenesis occurs during the secondary and tertiary matrix at the end of the first postnatal week (Schlessinger et al., 1975). Our analysis begins at this time (P7), when these early developmental stages are complete and the dentate gyrus is discretely formed but is just beginning to mature into its neuronal layers.

Our developmental profile (Fig. 1) broadly defines the different progenitor population present within the dentate gyrus while our quantification data more closely annotate type I and type II progenitors (Fig. 4, D and Fig. 5). Consistent with our immunostaining results, the percentage of GFP-expressing cells within the dentate gyrus steadily declines over the course of the first several postnatal weeks. In addition to declining neurogenesis, progenitor cells from older animals experience age-related genetic changes as well. It is well known that the microenvironment affects the proliferative potential of a variety of organ-specific stem/progenitor cells (Boyle et al., 2007; Fliedner et al., 1985; Ivasenko et al., 1990; Jenkinson et al., 2003; Yanai et al., 1991; Zhu et al., 2004). Here, we demonstrate that declining neurogenesis observed in vivo is mimicked by our in vitro neurosphere cultures. Although the environment is likely relevant in the SGZ during hippocampal development, our results indicate that decreased proliferation of P28 progenitors in culture might be due to intrinsic factors that are regulating their neurogenic potential.

It is also important to point out that our neurosphere proliferation experiments were performed using neural progenitor cells derived exclusively from the dentate gyrus (Fig. 2). This is relevant due to the identification of several differences among various progenitor populations in vitro. For example, neurospheres derived from the SVZ contain more neurosphere-forming cells, are more proliferative and multipotent, and respond to FGF2 differently than SGZ-derived neurospheres (Becq et al., 2005). Furthermore, progenitors located throughout various regions of the SVZ and lateral ventricle display differential growth properties and suggest that the progenitor population from the SVZ is itself very heterogeneous (Golmohammadi et al., 2008). Other evidence suggests that neurospheres cultured from various regions of the brain retain a region-specific phenotype when cultured in vitro (Armando et al., 2007). We therefore needed to ensure that our neurosphere culture results were specific to progenitors derived from the SGZ of the dentate gyrus.

There are two possibilities to explain the data revealed by the neurosphere assays. First, P7 GFP-expressing progenitors may be more proliferative than those from P28. Also, it might be that P7 brains contain an increased number of proliferative cells compared to P28. Although the results presented here do not definitively distinguish between these two possibilities, the underlying conclusion is the same, that the P7 dentate gyrus is more proliferative than at P28 and that this increase in proliferation is due at least in part to cell-autonomous effects.

Results from the differentiation assay suggest that P7 and P28 progenitors preferentially mature into neurons and astrocytes, respectively (Fig. 4, C). This suggests that early type I and type II progenitors from P28 transgenic mice possess less potential to become neurons when compared to P7. These age-dependent changes in the ability to differentiate further suggest that these GFP-expressing progenitors are differentially and dynamically regulated. Furthermore, this finding might have several implications in regards to stem cell/progenitor therapies. For example, these results might help explain why certain populations of stem/progenitor cells are insufficient to stimulate neurogenesis in studies aimed at attenuating neurodegeneration.

In addition to determining the percentage of GFP-expressing cells in the dentate gyrus (Fig. 4, D) unbiased stereological quantifications were performed. Although the percentage of GFP-positive cells is highest in P7 brains (Fig. 4, D), the actual cell number of GFP-positive cells within the SGZ and the granular layer of the dentate gyrus is highest at P28 (Fig. 5, D). This can be explained by the morphological differences observed between the ages tested (P7, P28 and 2 months). The hippocampus in general is much smaller in early postnatal brains compared to those that are more mature. In addition, the development of the dentate gyrus is not complete until after the first week of life. As a result, the pattern of GFP-expressing cells is not structurally defined within the SGZ and granular layer at P7 (Fig. 5, A). Therefore, any GFP-positive cells within the molecular layer of the dentate gyrus would not contribute to the overall cell number quantified with stereology. However, in P28 and 2-month old brains, the GFP-positive progenitors are restricted to the SGZ and granular layers (Fig. 5, B and C, respectively).

Using RNA extracted from the uniform GFP-expressing population of progenitors in vivo, we have identified several potential regulators that affect progenitor population in a cell-autonomous manner. The most differentially expressed candidate we identified is GltI, which has well-defined roles in mature astrocytes (Tanaka, 2007). In the synaptic cleft, GltI acts to uptake excess glutamate between nerves in order to prevent neurotoxicity (Anderson and Swanson, 2000; Liang et al., 2008; Rothstein et al., 1996; Rothstein et al., 1994; Tanaka, 2007; Tanaka et al., 1997). However, little is known about its role, if any, in regulating postnatal neurogenesis. Our expression data confirms reports of GltI within dentate gyrus progenitors in the SGZ (Fig. 6) (Bar-Peled et al., 1997). The different expression patterns of GltI on P7 and P28 progenitors suggest that it may somehow dynamically regulate early progenitors within the postnatal dentate gyrus. Because glutamate is the main excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter in the brain, glutamate receptors and transporters, including GltI, play key roles in maintaining brain homeostasis throughout development and life. However, functional studies are necessary to determine if and how GltI is a neurogenic regulator.

We did identify other genes in our microarray study that are compelling targets and might explain some of these age-related genetic changes that we observe. For example wingless (Wnt1), which has been linked with stem cell maintenance in certain tissues (Kleber et al., 2005; Lowry et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2004), is down-regulated in P28 progenitors compared to P7 (ratio of 0.46). In addition, genes involved in positive regulation of cell proliferation such as Sox4(Sinner et al., 2007)are also significantly down-regulated in P28 progenitors (ratio of 0.41). More importantly however, is the fact that VEGF, which has previously been associated with age-dependent decreases in neurogenesis (Buckwalter et al., 2006; Hattiangady et al., 2005; Shetty et al., 2005), is also variably expressed within our GFP-expressing progenitors. Although these variably expressed genes did not fulfill all our criteria for in depth analysis due to variance observed between replicates, they provide for validation of our techniques used as well as targets for further study.

The data we present here provides evidence that the neurogenic niche is still undergoing dynamic transformational changes until two months of age when the neural progenitor population begins to stabilize. This observation therefore provides insight to studies that begin their analysis prior to P60 when the “adult” phenotype is not clearly established and the stem/progenitor population still retains characteristics of an earlier and more developmentally immature dentate gyrus.

Age-dependent changes in progenitor proliferation, differentiation, and function have implications in stem cell therapy and our understanding of progenitor cell biology. Although it is not known what causes decreased neurogenesis in aging and diseased brains, cell-based therapies including ex vivo transplantation of stem cells and stimulation of endogenous progenitor proliferation are receiving much attention (Limke and Rao, 2002; Limke and Rao, 2003). However, the regulation of neurogenesis and its effect on the aging or diseased brain is both complex and not well understood. Understanding the mechanisms and relevance underlying these age-dependent changes is necessary before we will be able to utilize the therapeutic potential of neural stem/progenitors cells.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Gui Zhang and Ben Orr for their technical assistance. Special thanks also goes to Angela Mobley from the Flow Cytometry Core at UT Southwestern and Dr. Lawrence Weir of Miltenyi Biotec. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. Neal Melvin for his assistance with stereological experiments.

Support: NIH grant R01 NS048192 (SGK). The authors have no other financial interest to disclose.

References

- Abrous DN, Koehl M, Le Moal M. Adult neurogenesis: from precursors to network and physiology. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(2):523–569. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00055.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer SA. Prolonged sojourn of developing pyramidal cells in the intermediate zone of the hippocampus and their settling in the stratum pyramidale. J Comp Neurol. 1990;301(3):343–364. doi: 10.1002/cne.903010303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J Comp Neurol. 1965;124(3):319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Buylla A, Seri B, Doetsch F. Identification of neural stem cells in the adult vertebrate brain. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57(6):751–758. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00770-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CM, Swanson RA. Astrocyte glutamate transport: review of properties, regulation, and physiological functions. Glia. 2000;32(1):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armando S, Lebrun A, Hugnot JP, Ripoll C, Saunier M, Simonneau L. Neurosphere-derived neural cells show region-specific behaviour in vitro. Neuroreport. 2007;18(15):1539–1542. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f03d54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317(5838):666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey KJ, Maslov AY, Pruitt SC. Accumulation of mutations and somatic selection in aging neural stem/progenitor cells. Aging Cell. 2004;3(6):391–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Peled O, Ben-Hur H, Biegon A, Groner Y, Dewhurst S, Furuta A, Rothstein JD. Distribution of glutamate transporter subtypes during human brain development. J Neurochem. 1997;69(6):2571–2580. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69062571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkho BZ, Song H, Aimone JB, Smrt RD, Kuwabara T, Nakashima K, Gage FH, Zhao X. Identification of astrocyte-expressed factors that modulate neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2006;15(3):407–421. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastos GN, Moriya T, Inui F, Katura T, Nakahata N. Involvement of cyclooxygenase-2 in lipopolysaccharide-induced impairment of the newborn cell survival in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2008;155(2):454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becq H, Jorquera I, Ben-Ari Y, Weiss S, Represa A. Differential properties of dentate gyrus and CA1 neural precursors. J Neurobiol. 2005;62(2):243–261. doi: 10.1002/neu.20089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M, Wong C, Rocha M, Jones DL. Decline in self-renewal factors contributes to aging of the stem cell niche in the Drosophila testis. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(4):470–478. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckwalter MS, Yamane M, Coleman BS, Ormerod BK, Chin JT, Palmer T, Wyss-Coray T. Chronically increased transforming growth factor-beta1 strongly inhibits hippocampal neurogenesis in aged mice. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(1):154–164. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulloch K, Miller MM, Gal-Toth J, Milner TA, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Waters EM, Kaunzner UW, Liu K, Lindquist R, Nussenzweig MC, et al. CD11c/EYFP transgene illuminates a discrete network of dendritic cells within the embryonic, neonatal, adult, and injured mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508(5):687–710. doi: 10.1002/cne.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calof AL. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors regulating vertebrate neurogenesis. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Gould E. Adult neurogenesis is regulated by adrenal steroids in the dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 1994;61(2):203–209. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, Hazel TG, McKay RD. Regulation of neurogenesis by growth factors and neurotransmitters. J Neurobiol. 1998;36(2):287–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, McEwen BS, Gould E. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by excitatory input and NMDA receptor activation in the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 1995;15(6):4687–4692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04687.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435(4):406–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie BR, Cameron HA. Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Hippocampus. 2006;16(3):199–207. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F. A niche for adult neural stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13(5):543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X, Kang E, Liu CY, Ming GL, Song H. Development of neural stem cell in the adult brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encinas JM, Vaahtokari A, Enikolopov G. Fluoxetine targets early progenitor cells in the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(21):8233–8238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601992103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enwere E, Shingo T, Gregg C, Fujikawa H, Ohta S, Weiss S. Aging results in reduced epidermal growth factor receptor signaling, diminished olfactory neurogenesis, and deficits in fine olfactory discrimination. J Neurosci. 2004;24(38):8354–8365. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2751-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliedner TM, Calvo W, Klinnert V, Nothdurft W, Prummer O, Raghavachar A. Bone marrow structure and its possible significance for hematopoietic cell renewal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1985;459:73–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb20817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis F, Koulakoff A, Boucher D, Chafey P, Schaar B, Vinet MC, Friocourt G, McDonnell N, Reiner O, Kahn A, et al. Doublecortin is a developmentally regulated, microtubule-associated protein expressed in migrating and differentiating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23(2):247–256. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80777-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen K, McKay RD. Proliferation and differentiation of rat neuroepithelial precursor cells in vivo. J Neurosci. 1988;8(4):1144–1151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01144.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker RA, Carpenter MK, Winkler C, Greco C, Gates MA, Bjorklund A. Site-specific migration and neuronal differentiation of human neural progenitor cells after transplantation in the adult rat brain. J Neurosci. 1999;19(14):5990–6005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05990.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frotscher M, Zhao S, Forster E. Development of cell and fiber layers in the dentate gyrus. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:133–142. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S. Kinetics of cellular proliferation. Exp Cell Res. 1962;28:52–60. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(62)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S. The matrix cell and cytogenesis in the developing central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1963;120:37–42. doi: 10.1002/cne.901200104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita S. Analysis of Neuron Differentiation in the Central Nervous System by Tritiated Thymidine Autoradiography. J Comp Neurol. 1964;122:311–327. doi: 10.1002/cne.901220303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22(3):612–613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-00612.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH, Coates PW, Palmer TD, Kuhn HG, Fisher LJ, Suhonen JO, Peterson DA, Suhr ST, Ray J. Survival and differentiation of adult neuronal progenitor cells transplanted to the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(25):11879–11883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemma C, Bachstetter AD, Cole MJ, Fister M, Hudson C, Bickford PC. Blockade of caspase-1 increases neurogenesis in the aged hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26(10):2795–2803. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Greenberg ME. Distinct roles for bFGF and NT-3 in the regulation of cortical neurogenesis. Neuron. 1995;15(1):89–103. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goergen EM, Bagay LA, Rehm K, Benton JL, Beltz BS. Circadian control of neurogenesis. J Neurobiol. 2002;53(1):90–95. doi: 10.1002/neu.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golmohammadi MG, Blackmore DG, Large B, Azari H, Esfandiary E, Paxinos G, Franklin KB, Reynolds BA, Rietze RL. Comparative analysis of the frequency and distribution of stem and progenitor cells in the adult mouse brain. Stem Cells. 2008;26(4):979–987. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves MB, Suetterlin P, Yip P, Molina-Holgado F, Walker DJ, Oudin MJ, Zentar MP, Pollard S, Yanez-Munoz RJ, Williams G, et al. A diacylglycerol lipase-CB2 cannabinoid pathway regulates adult subventricular zone neurogenesis in an age-dependent manner. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38(4):526–536. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ. Stereology--or how figures for spatial shape and content are obtained by observation of structures in sections. Microsc Acta. 1980;83(5):409–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Shi D, Li W, Liang C, Wang H, Ye Z, Hu L, Wang HQ, Li Y. Proliferation and neurogenesis of neural stem cells enhanced by cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Microsurgery. 2008;28(1):54–60. doi: 10.1002/micr.20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattiangady B, Rao MS, Shetty GA, Shetty AK. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, phosphorylated cyclic AMP response element binding protein and neuropeptide Y decline as early as middle age in the dentate gyrus and CA1 and CA3 subfields of the hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 2005;195(2):353–371. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine VM, Maslam S, Joels M, Lucassen PJ. Prominent decline of newborn cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in the aging dentate gyrus, in absence of an age-related hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis activation. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(3):361–375. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller S, Ernsberger U, Rohrer H. Extrinsic signals in the developing nervous system: the role of neurokines during neurogenesis. Perspect Dev Neurobiol. 1996;4(1):19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivasenko IN, Klestova OV, Arkad'eva GE, Almazov VA. Role of stromal microenvironment in the regulation of bone marrow hemopoiesis after curantyl administration. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1990;110(7):98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson EL, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Gil-Perotin S, Roy M, Quinones-Hinojosa A, VandenBerg S, Alvarez-Buylla A. PDGFR alpha-positive B cells are neural stem cells in the adult SVZ that form glioma-like growths in response to increased PDGF signaling. Neuron. 2006;51(2):187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson WE, Jenkinson EJ, Anderson G. Differential requirement for mesenchyme in the proliferation and maturation of thymic epithelial progenitors. J Exp Med. 2003;198(2):325–332. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joels M, Karst H, Alfarez D, Heine VM, Qin Y, van Riel E, Verkuyl M, Lucassen PJ, Krugers HJ. Effects of chronic stress on structure and cell function in rat hippocampus and hypothalamus. Stress. 2004;7(4):221–231. doi: 10.1080/10253890500070005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko N, Sawamoto K. Adult neurogenesis in physiological and pathological conditions. Brain Nerve. 2008;60(4):319–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Novartis Found Symp. 2000;231:220–235. discussion 235-41, 302-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Gast D, Kronenberg G, Yamaguchi M, Gage FH. Early determination and long-term persistence of adult-generated new neurons in the hippocampus of mice. Development. 2003;130(2):391–399. doi: 10.1242/dev.00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Gage FH. More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature. 1997;386(6624):493–495. doi: 10.1038/386493a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernie SG, Erwin TM, Parada LF. Brain remodeling due to neuronal and astrocytic proliferation after controlled cortical injury in mice. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66(3):317–326. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber M, Lee HY, Wurdak H, Buchstaller J, Riccomagno MM, Ittner LM, Suter U, Epstein DJ, Sommer L. Neural crest stem cell maintenance by combinatorial Wnt and BMP signaling. J Cell Biol. 2005;169(2):309–320. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200411095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch JD, Miles DK, Gilley JA, Yang CP, Kernie SG. Brief exposure to hyperoxia depletes the glial progenitor pool and impairs functional recovery after hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(7):1294–1306. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg G, Bick-Sander A, Bunk E, Wolf C, Ehninger D, Kempermann G. Physical exercise prevents age-related decline in precursor cell activity in the mouse dentate gyrus. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27(10):1505–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci. 1996;16(6):2027–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, et al. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129(7):1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire V, Koehl M, Le Moal M, Abrous DN. Prenatal stress produces learning deficits associated with an inhibition of neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(20):11032–11037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Pleasure SJ. Genetic regulation of dentate gyrus morphogenesis. Prog Brain Res. 2007;163:143–152. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang J, Takeuchi H, Doi Y, Kawanokuchi J, Sonobe Y, Jin S, Yawata I, Li H, Yasuoka S, Mizuno T, et al. Excitatory amino acid transporter expression by astrocytes is neuroprotective against microglial excitotoxicity. Brain Res. 2008;1210:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limke TL, Rao MS. Neural stem cells in aging and disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2002;6(4):475–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2002.tb00451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limke TL, Rao MS. Neural stem cell therapy in the aging brain: pitfalls and possibilities. J Hematother Stem Cell Res. 2003;12(6):615–623. doi: 10.1089/15258160360732641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry WE, Blanpain C, Nowak JA, Guasch G, Lewis L, Fuchs E. Defining the impact of beta-catenin/Tcf transactivation on epithelial stem cells. Genes Dev. 2005;19(13):1596–1611. doi: 10.1101/gad.1324905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin MB. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron. 1993;11(1):173–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald HY, Wojtowicz JM. Dynamics of neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of adult rats. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles DK, Kernie SG. Hypoxic-ischemic brain injury activates early hippocampal stem/progenitor cells to replace vulnerable neuroblasts. Hippocampus. 2008;18(8):793–806. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky AV, Slutsky SG, Joseph NM, He S, Pardal R, Krishnamurthy J, Sharpless NE, Morrison SJ. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature. 2006;443(7110):448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen RJ, Buck CR, Smith AM. NeuN, a neuronal specific nuclear protein in vertebrates. Development. 1992;116(1):201–211. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HW, Junghans U, Kappler J. Astroglial neurotrophic and neurite-promoting factors. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;65(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai J, Fujita S. Early events in the histo- and cytogenesis of the vertebrate CNS. Int J Dev Biol. 1994;38(2):175–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Masuda N, Jiang M, Li Q, Zhao M, Ross CA, Duan W. The antidepressant sertraline improves the phenotype, promotes neurogenesis and increases BDNF levels in the R6/2 Huntington's disease mouse model. Exp Neurol. 2008;210(1):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MS, Hattiangady B, Shetty AK. The window and mechanisms of major age-related decline in the production of new neurons within the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Aging Cell. 2006;5(6):545–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme PA, Drapeau E, Doetsch F. Brain micro-ecologies: neural stem cell niches in the adult mammalian brain. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1489):123–137. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Dykes-Hoberg M, Pardo CA, Bristol LA, Jin L, Kuncl RW, Kanai Y, Hediger MA, Wang Y, Schielke JP, et al. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron. 1996;16(3):675–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Martin L, Levey AI, Dykes-Hoberg M, Jin L, Wu D, Nash N, Kuncl RW. Localization of neuronal and glial glutamate transporters. Neuron. 1994;13(3):713–725. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger AR, Cowan WM, Gottlieb DI. An autoradiographic study of the time of origin and the pattern of granule cell migration in the dentate gyrus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1975;159(2):149–175. doi: 10.1002/cne.901590202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaberg RM, van der Kooy D. Adult rodent neurogenic regions: the ventricular subependyma contains neural stem cells, but the dentate gyrus contains restricted progenitors. J Neurosci. 2002;22(5):1784–1793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01784.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T. Hippocampal adult neurogenesis occurs in a microenvironment provided by PSA-NCAM-expressing immature neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69(6):772–783. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seki T, Arai Y. Distribution and possible roles of the highly polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM-H) in the developing and adult central nervous system. Neurosci Res. 1993;17(4):265–290. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(93)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AK, Hattiangady B, Shetty GA. Stem/progenitor cell proliferation factors FGF-2, IGF-1, and VEGF exhibit early decline during the course of aging in the hippocampus: role of astrocytes. Glia. 2005;51(3):173–186. doi: 10.1002/glia.20187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Miles DK, Orr BA, Massa SM, Kernie SG. Injury-induced neurogenesis in Bax-deficient mice: evidence for regulation by voltage-gated potassium channels. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(12):3499–3512. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinner D, Kordich JJ, Spence JR, Opoka R, Rankin S, Lin SC, Jonatan D, Zorn AM, Wells JM. Sox17 and Sox4 differentially regulate beta-catenin/T-cell factor activity and proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(22):7802–7815. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02179-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhonen JO, Peterson DA, Ray J, Gage FH. Differentiation of adult hippocampus-derived progenitors into olfactory neurons in vivo. Nature. 1996;383(6601):624–627. doi: 10.1038/383624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. Role of glutamate transporters in astrocytes. Brain Nerve. 2007;59(7):677–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Takahashi K, Iwama H, Nishikawa T, Ichihara N, Kikuchi T, et al. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276(5319):1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Wang Y, Xie L, Mao X, Won SJ, Galvan V, Jin K. Effect of neural precursor proliferation level on neurogenesis in rat brain during aging and after focal ischemia. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(2):299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavazoie M, Van der Veken L, Silva-Vargas V, Louissaint M, Colonna L, Zaidi B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Doetsch F. A specialized vascular niche for adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3(3):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonchev AB, Yamashima T. Differential neurogenic potential of progenitor cells in dentate gyrus and CA1 sector of the postischemic adult monkey hippocampus. Exp Neurol. 2006;198(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropepe V, Craig CG, Morshead CM, van der Kooy D. Transforming growth factor-alpha null and senescent mice show decreased neural progenitor cell proliferation in the forebrain subependyma. J Neurosci. 1997;17(20):7850–7859. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-07850.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JP, Black IB, DiCicco-Bloom E. Stimulation of neonatal and adult brain neurogenesis by subcutaneous injection of basic fibroblast growth factor. J Neurosci. 1999;19(14):6006–6016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06006.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West MJ. New stereological methods for counting neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 1993;14(4):275–285. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(93)90112-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]