Introduction to Hsp70 Structure and Function

Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) is a molecular chaperone that is expressed in response to stress. In this role, Hsp70 binds to its protein substrates and stabilize them against denaturation or aggregation until conditions improve.1 In addition to its functions during a stress response, Hsp70 has multiple responsibilities during normal growth; it assists in the folding of newly synthesized proteins,2, 3 the subcellular transport of proteins and vesicles,4 the formation and dissociation of complexes,5 and the degradation of unwanted proteins.6, 7 Thus, this chaperone broadly shapes protein homeostasis by controlling protein quality control and turnover during both normal and stress conditions.8 Consistent with these diverse activities, genetic and biochemical studies have implicated it in a range of diseases, including cancer, neurodegeneration, allograft rejection and infection. This review provides a brief review of Hsp70 structure and function and then explores some of the emerging opportunities (and challenges) for drug discovery.

Hsp70 is Highly Conserved

Members of the Hsp70 family are ubiquitously expressed and highly conserved; for example, the major Hsp70 from Escherichia coli, termed DnaK, is approximately 50% identical to human Hsp70s.9 Eukaryotes often express multiple Hsp70 family members with major isoforms found in all the cellular compartments: Hsp72 (HSPA1A) and heat shock cognate 70 (Hsc70/HSPA8) in the cytosol and nucleus, BiP (Grp78/HSPA5) in the endoplasmic reticulum and mtHsp70 (Grp75/mortalin/HSPA9) in mitochondria. Some of the functions of the cytosolic isoforms, Hsc70 and Hsp72, are thought to be redundant, but the transcription of Hsp72 is highly responsive to stress and Hsc70 is constitutively expressed. In the ER and mitochondria, the Hsp70 family members are thought to fulfill specific functions and have unique substrates, with BiP playing key roles in the folding and quality control of ER proteins and mtHsp70 being involved in the import and export of proteins from the mitochondria. For the purposes of this review, we will often use Hsp70 as a generic term to encompass the shared properties of the family members.

Domain Architecture and Substrate Binding of Hsp70

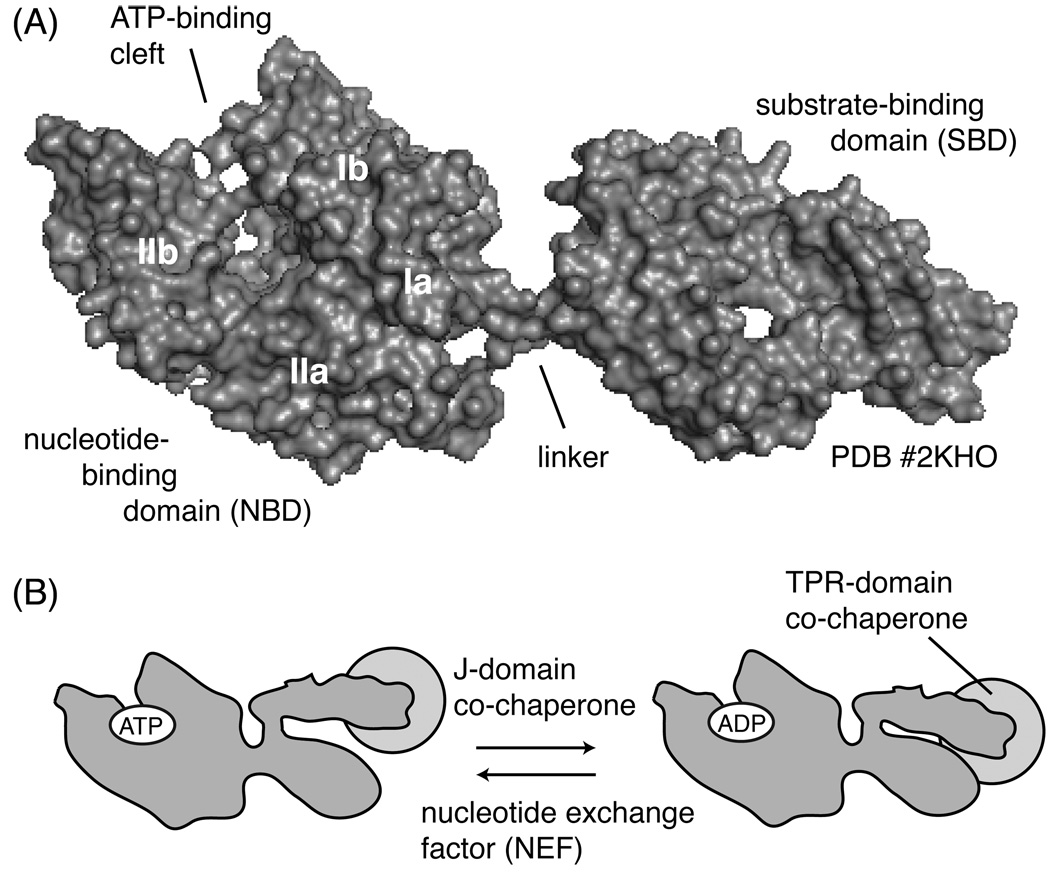

All members of the Hsp70 family have an N-terminal nucleotide binding domain (NBD) (~40 kDa) and a C-terminal substrate-binding domain (SBD) (~25 kDa) connected by a short linker (Figure 1A).10 The NBD consists of two subdomains, I and II, which are further divided into regions a and b. The Ia and IIa subdomains interact with ATP through a nucleotide-binding cassette related to those of hexokinase, actin and glycerol kinase.11, 12 The SBD consists of a 10-kDa α-helix subdomain and a 15-kDa β-sandwich. Crystal structures suggest that substrate peptides are bound in an extended conformation between loops of the β-sandwich and that the α-helix subdomain acts as a “lid”.13 The substrates of Hsp70 are thought to include both linear polypeptides, such as those found in newly synthesized proteins or folding intermediates,3 and exposed regions of fully or partially folded proteins. For example, Hsp70 is known to interact with clathrin, components of the transcriptional activation complex, nuclear hormone receptors and many others.5, 14, 15 This diversity of substrates is allowed by the low sequence selectivity of the SBD, which binds to most peptides composed of most non-polar amino acids.16

Figure 1. Structure and ATPase cycle of Hsp70.

(A) Heat shock protein 70 is composed of a 45 kDa nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), connected to a 30kDa substrate-binding domain (SBD) by a short, hydrophobic linker. The SBD contains a beta-sandwich and a helical lid domain. The representative structure shown is of prokaryotic DnaK in complex with ADP and a peptide substrate (PDB # 2KHO). (B) Schematic of ATP hydrolysis and the role of co-chaperones.

ATPase Activity of Hsp70

Many of the functions of Hsp70 appear to revolve around crosstalk between ATPase activity in the NBD and substrate binding in the SBD. Hsp70 binds tightly to ATP, with some reports of E. coli DnaK binding with a Kd of 1 nM.17 Through an inter-domain, allosteric mechanism, ATP binding increases the on- and off-rate of peptide binding in the adjacent SBD. In turn, nucleotide hydrolysis to ADP closes the “lid” and enhances the affinity for substrate (Figure 1B).18 Likewise, interactions between the SBD and its substrates increase the rate of ATP hydrolysis in the NBD, suggesting that communication between the two domains is two-way.18 The mechanisms of inter-domain communication have been studied extensively and appear to involve the conserved, hydrophobic linker.19, 20 Thus, from a drug discovery viewpoint, this allostery in Hsp70 provides multiple opportunities for chemical intervention, including inhibition of ATP turnover, substrate binding or even blocking inter-domain allostery.

Hsp70 Co-Chaperones

As isolated proteins, the ATP hydrolysis rates of Hsc70 and DnaK are extremely slow, 0.003 and 0.0003 s−1, respectively.17, 21 In vivo, this property provides the opportunity for regulation by co-chaperones, which associate with Hsp70s and control their nucleotide turnover. For example, the J proteins (or Hsp40s) are a large group of co-chaperones that stimulate ATP hydrolysis (Figure 1B).22 In the human genome, at least 40 different J protein genes have been identified23 and each contains the conserved, ~70 amino acid J domain required for binding and stimulation of Hsp70s.24 NMR, mutagenesis and crystallography studies indicate that at least one binding site of the J domain is on the NBD.25, 26 Protein-protein interactions between the J domain and Hsp70 trigger an allosteric “hotwire” through the NBD that enhances ATP turnover by approximately 7-fold. Thus, in the presence of a J-protein, the release of ADP becomes the rate-limiting step.27 To complete the ATPase cycle, a distinct class of co-chaperones, the nucleotide exchange factors (NEFs) catalyze ADP release. The major NEF families include, the GrpE-like family,28 BAG family proteins,29 HspBP130 and the atypical Hsp70 homologs (e.g. Hsp110).31 All of these NEFs appear to bind the NBD and favor ADP release, but each class uses a different structural mechanism to achieve this effect.32 Together, the J-domain proteins and NEFs regulate ATP cycling, and therefore they also control substrate binding. In addition, some of the co-chaperones independently bind substrates and, through this activity, have the potential to influence substrate selection by the Hsp70 complex.33, 34 Thus, although these co-chaperones do not have enzymatic activity, they are important regulatory factors and they are required for many chaperone functions of Hsp70.

A final group of co-chaperones, the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-containing proteins, bind to the EEVD sequence at the extreme C-terminus of Hsp70. Interestingly, the evolutionarily unrelated molecular chaperone, Hsp90, also contains the EEVD motif, allowing it to also interact with TPR domains. The TPR is characterized by a 34-amino acid motif that forms an antiparallel α-helical hairpin.35 Most proteins that have TPR domains also have additional domains with other activities and, thus, these co-chaperones are thought to recruit unique capabilities to the Hsp70 complex. For example, HOP has three domains (TPR1, TPR2A, and TPR2B) with three TPR motifs each.36 HOP preferably binds to the ADP-bound form of Hsp70 via TPR1 and TPR2B, while TPR2A specifically binds to Hsp90.37–39 In this way, Hop bridges Hsp70 and Hsp90, assists substrate transfer between these chaperones and is believed to promote substrate folding.40 Another TPR-domain protein, CHIP, also contains a U-box domain and it supervises the triage of Hsp70- or Hsp90-bound proteins.41, 42 Thus, although both HOP and CHIP bind via TPR domains, the outcomes of these interactions are diametrically opposed: HOP favors folding, while CHIP favors degradation. Based on these observations and many others, it is thought that competition between co-chaperones might drive combinatorial assembly of chaperone complexes with specific functions.5, 8, 43 Together, these features suggest that protein-protein contacts in the Hsp70 complex may be potential drug targets.

Roles of Hsp70 in Disease

Cancer and apoptosis

Hsp70 expression has been routinely associated with poor prognosis in multiple forms of cancer.44 For example, high Hsp70 levels are associated with adverse outcomes in breast, endometrial, oral, colorectal, prostate cancers as well as certain leukemias.45–48 Moreover, transgenic over-expression of Hsp70 is sufficient to induce T cell lymphoma in some models.47 This observation is important because induction of Hsp70 can be misregulated in cancer, potentially mediated by altered activity of the heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1).44, 49, 50 In cancer cells, over-expression of Hsp70 is thought to provide a survival advantage because it is able to interact with multiple components of both the caspase-dependent and –independent apoptotic pathways (Figure 2 and Table 1).44, 51, 52 For example, this chaperone was reported to regulate the important apoptotic mediator, Bcl-2.53 Similarly, expression of Hsp70 blocks TNF-induced apoptosis, activation of caspase-3, translocation of Bax and cleavage of PPAR.54–57 Some of these interactions are thought to be direct. For example, immunoprecipitation has shown an interaction between Hsp72 and Bax.55 In this context, Hsp72 prevents Bax translocation by blocking its oligomerization, a step necessary for disruption of the mitochondrial membrane.56, 57 By influencing multiple steps in the same cascade, Hsp70 is likely to exert even more potent anti-apoptotic activity than if it was acting on an individual protein. Similarly, Hsp70 has also been found to block caspase-independent signaling through activity on cathepsins and Apaf-1.58 For example, Hsp70 knockdown increases cathepsin B release and protects lysosomes from photo- and H2O2-mediated permeabilization.59 In addition to these effects on the caspase-dependent and –independent apoptotic pathways, Hsp72 also plays roles in senescence through effects on the p53-p21 pathway.60 Together, these results suggest that Hsp70 interacts with multiple partners in the apoptosis and senescence pathways, a model that is consistent with Hsp70’s known substrate promiscuity. Importantly, the ATPase activity of Hsp70 doesn’t appear to be required for all of these activities, as the action of Hsp70 on JNK and AIF occurs independent of nucleotide hydrolysis.61–63 64 This is an important observation, because many of the early Hsp70 inhibitors target its ATPase activity. While shRNA-mediated knockdown of Hsp70 induces apoptosis and slows cell proliferation in multiple cancer cell models,46, 65, 66 it is unclear whether inhibitors of specific Hsp70 functions, such as nucleotide turnover, will mimic this favorable cellular effect. Regardless, these studies suggest that cancer cells become “addicted” to Hsp70 through this chaperone’s activity on multiple, parallel signaling pathways.67

Figure 2. Roles of Hsp70 in anti-apoptotic signaling.

Hsp70 is thought to promote survival and block apoptosis through interactions with multiple steps in the pathway. For some substrates, Hsp70’s role appears to be stabilization of the substrate, while it appears to mediate the degradation of other substrates. The regulatory mechanisms that govern these activities are not known. See the main text and Table 1 for references.

Table 1.

Roles of Hsp70 in Apoptotic Signaling

| Process | Role of Hsp70 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Caspase-Dependent | ||

| Pathway | ||

| Bid | Hsp72 inhibits TNF activation of the Bid pathway | 54 |

| Caspase-9 | Hsp70 inhibits recruitment of procaspase-9 to the apoptosome | 58 |

| Hsp70 binds to Apaf-1, preventing formation of the active apoptosome |

194 | |

| BCL2 | Hsp70 inhibits the proteasomal degradation of Bcl2 proteins | 53 |

| Hsp70 inhibits cytochrome c release from mitochondria by inhibiting Bad and Bax |

195 | |

| Caspase-3 | Hsp70 inhibits caspase-3 induced apoptosis | 195 |

| Caspase-Independent | ||

| Pathway | ||

| JNK | Hsp72 inhibits JNK induced apoptosis, but its ATPase activity is dispensable |

61, 196–200 |

| AIF | Hsp70 prevents the release of AIF from mitochondria | 64, 201, 202 |

| Lysosome | Hsp70 stabilizes lysosomal membrane integrity | 59, 203, 204 |

| p53 | Hsp70 blocks p53-induced senescence through PI3K |

46, 60, 205– 207 |

Hsp70 over-expression has also been documented to provide resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, such as imatinib, etopiside, cisplatin and MG-132.68, 69 Although the detailed mechanisms of resistance remain to be elucidated, recent evidence suggests that reduced activation of ERK, NF-κB, and JNK pathways may be responsible.69 The protective effects of Hsp70 are particularly striking in response to treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors, such as geldanamycin and its derivatives.67, 70 Like Hsp70, Hsp90 is an ATP-utilizing molecular chaperone with roles in protein turnover.71 However, Hsp90 is often considered the more “specialized” chaperone, with a relatively restricted set of cellular substrates. Among Hsp90’s are key anti-apoptotic proteins, including Akt, Cdk4, Raf1 and Her2.71, 72 Inhibiting the binding of Hsp90 to ATP leads to proteasomal degradation of these substrates and corresponding anti-proliferative activity.50, 73, 74 In the context of our discussion, treatment with Hsp90 inhibitors has also been found to induce expression of Hsp70, likely through activation of HSF1.70 As discussed above, this compensatory mechanism can cause resistance to apoptosis and stabilization of some shared protein substrates, such as Akt.67, 70 Together, these observations suggest that dual therapy against both Hsp90 and Hsp70 might be beneficial. This hypothesis is strongly supported by observations that RNAi knockdown of Hsp70s enhances the efficacy of Hsp90 inhibitors.75, 76

Protein Misfolding and Neurodegenerative Disease

One of the other important roles of Hsp70 is to assist protein folding and turnover. In normal cells, quality control systems prevent the accumulation of toxic misfolded protein species. However, in response to mutagenesis, aging or oxidative stress, misfolding can often occur.77–79 As post-mitotic cells, neurons appear to be particularly sensitive to these effects and many neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, involve aberrant accumulation of misfolded or misprocessed proteins. Genetic studies have routinely linked Hsp70 and its co-chaperones to this process and, thus, it has emerged as a potential drug target (Table 2). For example, one recent study has shown that Hsp70 directly stabilizes lysozomes and plays a key role in Niemann-Pick disease.80 We will discuss two models here and further information can be found in recent reviews.81, 82

Table 2.

Roles of Hsp70 in Neurodegenerative Disease

| Disease | Role of Hsp70 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| HD | Hsp70 co-localizes with polyQ aggregates | 208 |

| Hsp70 and Hsp40 prevent aggregation of purified HD exon 1 | 85 | |

| Over-expression of Hsp70 and Hsp40 reduces polyQ aggregation and cytotoxicity |

88, 208 | |

| Hsp70 inhibits polyQ-induced caspase 3 and 9 activation and M3/6 JNK phosphatase aggregation |

94, 209 | |

| Over-expression of Hsp70 does not significantly ameliorate the disease symptoms of R6/2 HD model mice |

93 | |

| HSF-1 activating compounds reduce polyQ aggregation and rescue neurodegeneration in cultured cells and HD model mice |

100, 102, 103 |

|

| SCA1 | Hsp70 over-expression suppresses neurodegeneration and improves motor function in SCA1 mice |

91 |

| SCA3 | Hsp70 co-localizes with nuclear inclusions of ataxin-3 | 89, 210 |

| Over-expression of Hsp70 suppresses polyQ-mediated neuropathy in a Drosophila model of SCA3 |

89 | |

| SCA7 | Hdj2 and Hsp70 prevent mutant ataxin-7 aggregation in cultured cells but not in a mouse model |

92 |

| SBMA | Hsp70 co-localizes with nuclear inclusions of polyQ expanded androgen receptor (AR) |

90, 211 |

| Hsp70 and Hsp40 increases the SDS-solubility and proteasomal degradation of mutated AR in cultured cells |

212 | |

| Over-expression Hsp70 ameliorates disease phenotypes in a SBMA model | 90 | |

| Oral administration of GGA, an HSF1 inducer, ameliorates the SBMA phenotype in mouse models |

101 | |

| AD-Aβ | Hsp70 and Hsp40 block in vitro Aβ self assembly | 106 |

| Hsp70 reduces steady state Aβ levels and Aβ-induced cytoxicity in cultured cells | 107 | |

| AD-Tau | Hsp70 interacts with sites in tau important for aggregation | 109 |

| Hsp70-Bag2 captures and delivers insoluble and phosphorylated tau to the proteasome for ubiquitin-independent degradation |

116 | |

| Hsp70-Bag1 associates with tau and inhibits proteasomal degradation | 115 | |

| PD | Lewy bodies contain Hsp40 and Hsp70 | 213 |

| Over-expression of Hsp70 reduces α-synuclein aggregation and cytotoxicity | 214 | |

| Hsp70 over-expression prevents dopaminergic neuronal loss in PD models | 213, 215 | |

| CF | Immature CFTR and ΔF508 CFTR form complexes with Hdj-2 and Hsc70 | 216 |

| Inactivation of Hsc70 and CHIP in cultured cell increase surface expression of ΔF508 CFTR |

217 |

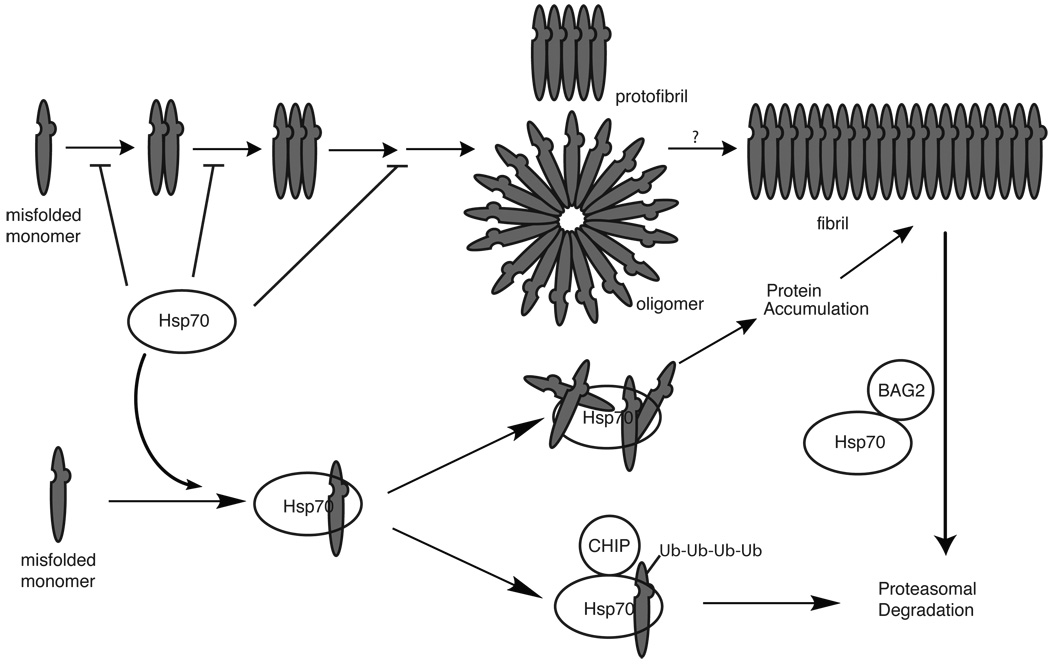

Polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases are a family of at least nine inherited neurodegenerative disorders, including Huntington’s disease (HD), spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA), and spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), caused by the expansion of trinucleotide CAG repeats in the disease genes.83 This expansion leads to the formation of an abnormally long glutamine tract in the synthesized protein.84 PolyQ expansion renders disease proteins prone to aggregation, and the extent of aggregation is correlated with the length of the polyQ.84 In vitro, Hsp70 (along with its J-domain co-chaperone Hdj1) can partially suppress the aggregation of the polyQ-expanded exon 1 of huntingtin (htt) in an ATP-dependent remodeling process.85 Importantly, these chaperones are only active when added during the lag phase of the aggregation reaction, which suggests that Hsc70 and Hdj1 preferably act on early, prefibrillar states (Figure 3).85 Similarly, in a yeast model, over-expression of the yeast Hsp70, Ssa1, decreases aggregation of htt and increased its SDS solubility.86 However, these relationships appear to be complex because, in O23, COS-7, PC12, SH-SY5Y, and HEK293 cells, Hsp70 over-expression showed little effect on htt aggregation.87, 88 Similar themes are observed in animal models. For example, in fly models of SCA1 and mouse models of SCA1 and SBMA, over-expression of Hsp70 suppresses the neurodegenerative phenotypes,89–91 while no significant effect is observed in mouse models of HD or SCA7.92, 93 It is worth noting that it is not clear whether polyQ aggregation is a good surrogate for toxicity. Moreover, it is not clear if Hsp70’s effects on cell viability are always mediated by direct effects on polyQ assembly or through more general buffering of pro-survival signaling.94

Figure 3. Potential roles for Hsp70 in protein misfolding and aggregation.

Hsp70 has been linked to multiple steps of the protein misfolding and aggregation pathway, including in preventing misfolding, blocking early stages of aggregation and in mediating the degradation of misfolded intermediates through coupling to the ubiquitin-proteasome system. The Hsp70 co-chaperones BAG2 and CHIP have both been linked to clearance of misfolded proteins. In some systems (including yeast prions), Hsp70 activity is required for fibril formation. For simplicity, this schematic encompasses broad aspects of the misfolding pathway of amyloid beta, polyglutamines and tau, although important differences likely exist. See the main text and Table 2 for references.

Despite these uncertainties, it is interesting to note that several co-chaperones, including J-domain proteins, CHIP and BAG, have dramatic effects on polyQ aggregate formation, either on their own or in concert with Hsp70. For example, over-expression of yeast Ydj1 (a J-domain co-chaperone) increase the solubility of htt,85 whereas a related J-domain co-chaperone, Sis1, splits large inclusions into smaller loci.86 The TPR-domain co-chaperone, CHIP, ubiquitinates htt and facilitates its degradation in a U-box dependent manner (Figure 3).95 The over-expression of CHIP also significantly rescues neurodegenerative symptoms in animal models of SCA1, SCA3, SBMA, and HD, while CHIP −/− mice have exaggerated disease progression in models of HD and SCA3.96–99 The role of Hsp70 in CHIP-mediated protection remains to be established, but current models suggest that Hsp70 is required for the CHIP–mediated effects.95, 96 Together, those observations suggest that protection against polyQ toxicity might require interplay between multiple components of the complex between chaperone and co-chaperones. Indeed, it has been shown that chemical stimulators of the heat shock response, such as geldanamycin, 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxy geldanamycin, geranylgeranylacetone, and celastrol, upregulate multiple chaperone components and rescue neurodegenerative symptoms in cell culture, fly, and mouse models of SCA1, HD, and SBMA.100–103

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common neurodegenerative disease and its patients are characterized by progressive memory loss and the accumulation of senile plaques (SP) composed of β-amyloid (Aβ) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) assembled from tau.104 Current models suggest that self-association of Aβ or tau into β-sheet rich oligomers leads to neuronal cell death (Figure 3).104, 105 Hsp70 has been shown to play important roles in the cytotoxicity of both Aβ and tau. For example, Hsp72 blocks the early stages of Aβ aggregation in vitro at substoichiometric levels106 (Figure 3), and Hsp70 has been shown to alter processing of the amyloid precursor protein.107 Also, this chaperone protects against Aβ-induced cytotoxicity via inhibiting caspase-9 and accelerating the elimination of Aβ.108 In addition to these effects on Aβ, Hsc70 also binds tau at two sites within its tubulin-binding repeats, which is the same region required for tau self-association.109 This finding suggests that Hsc70 might compete with aggregation and toxicity109 and, consistent with this model, over-expression of Hsp70 reduces aggregated tau in mouse models.110 Moreover, increasing Hsp70 levels promotes tau binding to microtubules and reduces the levels of hyperphosphorylated tau.111 Similar to the polyQ examples listed above, co-chaperones of Hsp70 also play roles in tau processing. For example, CHIP ubiquitinates phosphorylated tau in an Hsc70-dependent manner112, 113 and its over-expression accelerates tau degradation, reduces formation of insoluble tau and rescues tau-induced cell death (Figure 3).113, 114 The TPR-domain co-chaperones, BAG-1 and BAG-2, also impact tau aggregation, but in opposing ways.115, 116 An Hsc70-BAG-1 complex binds to tau and inhibits its turnover.115 In contrast, BAG-2 and Hsc70 form a microtubule-tethered complex that can capture and deliver insoluble and phosphorylated tau to the proteasome for degradation (Figure 3), likely through a ubiquitin-independent mechanism.116 Together, these results illuminate the complex relationships between Hsp70, its co-chaperones and their impact on AD and other tauopathies.

Infectious disease and immunity

The prokaryotic Hsp70, DnaK, is required for survival of bacteria under stressful conditions, such as thermal stress and challenge with heavy metals or antibiotics.117–119 Consistent with this activity, S. aureus dnaK mutants have reduced viability and are susceptible to stress.120 Most strikingly, these mutations increase sensitivity to oxacillin and methicillin in normally resistant S. aureus strains. Likewise, dnaK or dnaJ mutations in E. coli make the cells susceptible to fluoroquinolones.121, 122 These chaperones are also necessary for S. enterica to invade epithelial cells and for L. monocytogenes to survive in macrophages.123, 124 Thus, Hsp70 and its co-chaperones appear to be potential drug targets that would sensitize prokaryotes to stress, such as that provided by antibiotics or host responses.

In addition to its roles in bacterial physiology, Hsp70 is also important in host immunological responses and cell-cell interactions. For example, in mammalian cells infected with a virulent form of S. choleraesuis, the levels of Hsp70 correlate with an increase in TNF-α induced cell death.125 Hsc70 and other heat shock proteins also play important roles in IKK signaling, endocytic trafficking and possibly in antigen presentation, suggesting roles in activation and regulation of immune cells.126–128

Chemical Targeting of Hsp70s

Given these complex roles of Hsp70 in disease, it is not immediately apparent whether a good therapeutic strategy would be to stimulate, inhibit or otherwise re-direct the activity of this chaperone with chemical agents. For example, would stimulation of Hsp70’s ATPase activity provide protection from neurodegeneration? Would inhibition sensitize cancer cells to apoptosis? Moreover, should the ATPase activity of Hsp70 be the ideal target or is another function (e.g. protein folding, protein trafficking etc.) more appropriate? Given the promiscuity of Hsp70’s interactions with proteins, is it possible to influence the processing of individual substrates or will inhibitors have global effects? Although the answers to many of these important questions remain unknown, work over the last decade has provided first-generation, Hsp70-targeted compounds.129, 130 Interestingly, these compounds belong to a broad range of structural classes and some have distinct, non-overlapping binding sites on the Hsp70 surface. These observations suggest that there are multiple ways to impact Hsp70’s functions, such as through modulating its ATPase activity, its contacts with co-chaperones or binding to misfolded substrates. Importantly, these early probes have also begun to reveal unexpected aspects of Hsp70’s biology. Thus, even if these compounds do not directly lead to approved drugs, they have started to define Hsp70’s roles in disease and its potential as a drug target. In the following sections, we review the known chemical classes and briefly highlight the medicinal chemistry efforts and biological findings enabled by these probes.

Classes of Small Molecules that Interact with Hsp70

Spergualin-like Compounds

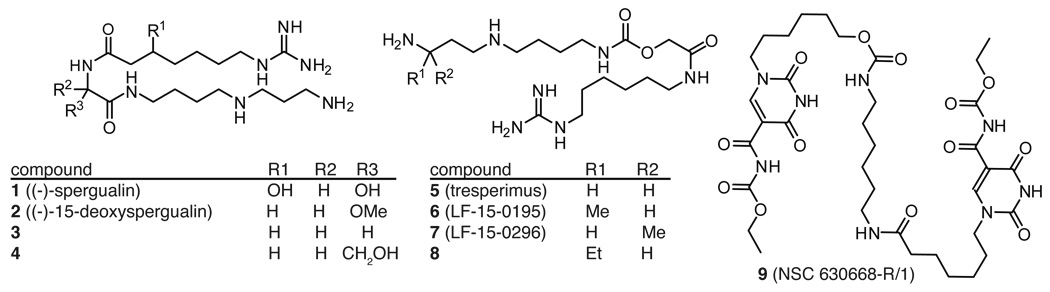

In 1981, Umezawa and colleagues reported the identification of a compound with antibiotic and anti-tumor activity from a Bacillus sp.131 They further characterized the active compound as the polyamine, (−)-spergualin 1 (Figure 4).132 Kondo and colleagues carried out the total synthesis of this compound in 14% overall yield.133 However, 1 was found to have poor stability in vitro and in vivo, which led to the synthesis of analogues, including 2 (15-deoxyspergualin; 15-DSG).134, 135 In an aqueous environment at pH 7, removal of the labile 15-hydroxyl group was found to improve stability to 2 days.136 The route to 2 and its derivatives involves formaldehyde-mediated cyclization of spermidine, followed by coupling of the free amine to an amino acid and installation of the ω-guanidino fatty acid.137 Thus, this approach allows ready variation of the amino acid identity. However, in antitumor assays against L1210 leukemia cells, only the glycine (3) and L-serine (4) derivatives retained activity, whereas even conservative replacements with alanine or leucine abolished function.137 Likewise, variations in the polyamine regions, such as the number of methyl groups or secondary amines, decreased efficacy.135 Taken together, these results suggest that the activity profile of spergualin analogues is surprisingly narrow.

Figure 4. Structures of spergualin and related polyamines.

Select structures from larger series are shown for clarity. See the text for references.

Despite the improved stability of 2, this compound still retained relatively poor bioavailability.138 In an attempt to circumvent some of these shortcomings, a series of derivatives was developed in which the amides are inverted and this change was found to greatly improve the molecule’s stability and activity.136 Following from these efforts, the hydroxyglycine moiety was substituted with a carbomoyl group, producing the promising derivatives 5 (tresperimus) and 6 (LF 15-0195) (Figure 4). However, in this series, only minor methyl substitutions were tolerated in a few positions without a dramatic loss of activity.139 For example, an R methyl group appended near the terminus, as in compound 6, was tolerated, while the opposite stereochemistry, as in compound 7, had no apparent Hsp70 binding and 3-fold reduced immunosuppressive activity.140 Likewise, conservative replacement of this methyl with an ethyl, as in compound 8, greatly reduced activity. Other portions of the molecule were equally sensitive to manipulation; for example, replacement of the guanidine with a pyridine reduced activity by approximately 4-fold.140 Taken together, the structure-activity studies have revealed a surprisingly limited range of acceptable modifications.

Using immobilized compound, 2 and its derivatives were found to bind to several proteins, including Hsc70 and Hsp90.140 141, 142 Based on mass spectrometry and competition studies, it was further proposed that 2 binds to the EEVD domain of these chaperones with an affinity ~ 5 µM.143, 144 This interaction appears to impact some of Hsp70’s functions, because 2 was able to increase Hsc70’s ATPase rate by approximately 20 to 40%.145 Although this change in ATP turnover rate seems minor, the biological activities of these compounds suggest that either (a) modest changes in enzymatic activity might disproportionately impact chaperone function or (b) ATP turnover is not the most relevant in vitro assay to describe the activity of these compounds on chaperone functions. Another possibility is that 2 has multiple cellular targets; for example α1-acid glycoprotein has been suggested as a potential partner.146

Although compound 1 was first identified as an anti-infective and anti-tumor agent, 2 was subsequently identified as a potent immunosuppressant. The molecular mechanisms of this activity are not entirely clear, but 2 has been proposed to block NF-κB trafficking and antigen presentation, two known cellular roles of Hsc70.128, 147 Regardless, 2 decreases the incidence of acute rejection in combination with cyclosporin and tacrolimus148 and it prolongs renal allograft survival.149 These immunological activities appear to arise from effects on dendritic cells150 and leukocyte151 and monocyte147 activation; for example, Birck and colleagues looked at T-cell activation in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis and found that patients treated with 2 had lower levels of proliferation markers, such as INF-γ and IL-10.149 Similarly, treatment with 2 leads to decreased mucosal injury and reduced TNF-α in a mouse model of colitis.152

Based on these activities, 2 has been explored in multiple clinical trials, with allograft rejection and malignant cancers being the most widely studied indications. For additional details an excellent review is available.146 Briefly, 2 is poorly bioavailable (5%), so it is typically delivered by i.v. infusion.138 It displays a bi-exponential decay, with an alpha half-life (t1/2) of 5 to 12 minutes and terminal half-life of approximately 2 hours.153 Metabolism is believed to occur, in part, through amine oxidases, with seven, inactive metabolites known.146 In rodents, infusion of 25 mg/kg/day for 9 days leads to a 4–6log reduction in tumor burden in a L1210 leukemia model.154 However, a Phase I clinical trial of 2 as a monotherapy against advanced malignancies showed no efficacy at 75 mg/kg/day.146 Similarly, a Phase II trial against metastatic breast cancer in 14 patients at 1800 or 2150 mg/m2/day by i.v. infusion for 5 days also showed no efficacy. However, in both trials, 2 was well tolerated and only low toxicity was observed (mild neuromuscular side effects as the only grade III toxicities).155 The activity of 2 in studies on immunological indications has been more promising. Since 1994, 2 has been used in Japan for acute kidney allograft rejection.146 The advantage of this compound is that, unlike FK506 or cyclosporin, it can be used up to 48 hrs after initiation of rejection and, therefore, can reverse ongoing organ rejection in animal models and humans. For example, 81% (25 of 31) of patients undergoing acute renal allograft rejection in one study showed reversal of rejection, even as a monotherapy in some cases.156 Importantly, 2 is not a P450 substrate and it can be used with cyclosporin or steroids.153 In fact, studies of kidney and liver allograft rejections in Western Europe revealed 65% reversion in combination with bolus steroids.157 In addition to these examples, many other pilot clinical studies in Japan and the U.S. have been reported, and these generally document good tolerability, low toxicity and efficacy in transplant models.146 While 2 has been used successfully in the clinic, the mechanism by which it exerts this effect is not fully understood. For example, how specific is this compound for Hsp70? If it is specific, how does binding to the EEVD control chaperone functions? Does the seemingly minor change in ATPase rate (20 to 40%) lead directly to the robust cellular effects? Is binding to both Hsp70 and Hsp90 important for activity? Clearly, additional structural and mechanistic experiments are needed.

Given the promising biological activity of these polyamines, Brodsky and colleagues searched the Developmental Therapeutics database at the National Cancer Institute for related compounds. This effort yielded, 9 (NSC 630668-R/1), which inhibits Hsc70’s ATPase activity and partially blocks chaperone-mediated protein translocation (Figure 4).158 However, unlike compound 2, which is a mild ATPase stimulator, 9 specifically inhibits Hsc70’s ATPase activity in the presence of a J-domain co-chaperone.158 This result is interesting because, although 9 was originally identified as a spergualin-like analogue, it might operate by a different mechanism.

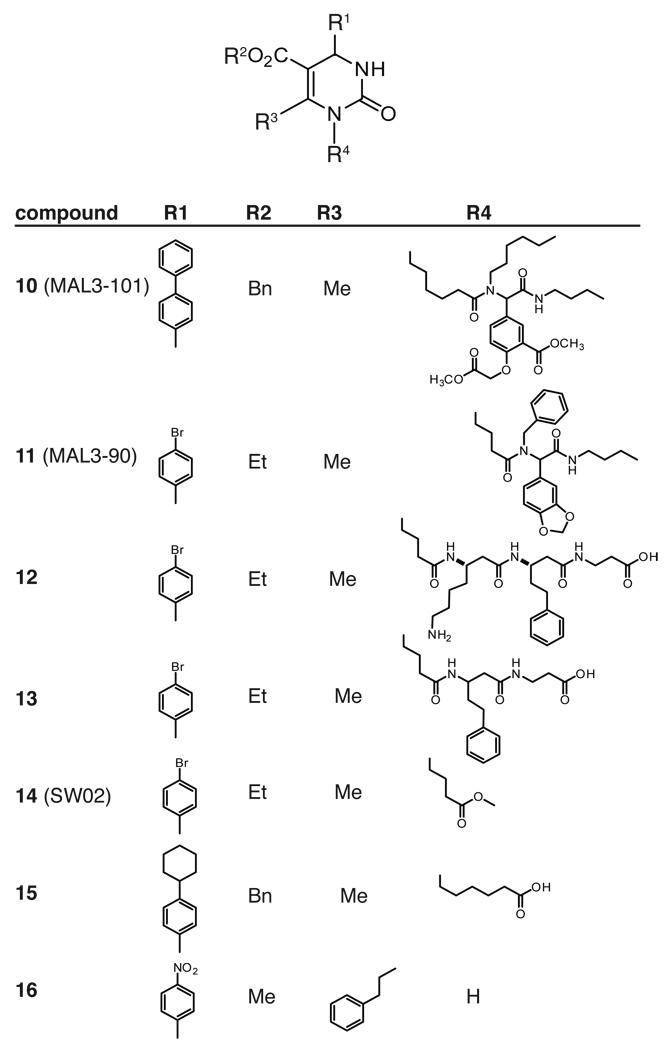

Dihydropyrimidines

Following the successful identification of 9, Brodsky and colleagues searched for other scaffolds able to alter Hsp70’s ATPase activity. Guided by structural similarity to 2 and 9, they focused on a series of functionalized dihydropyrimidines (Figure 5).159 The route to these compounds leveraged consecutive, Biginelli and Ugi multi-component reactions to yield diversity. In an ATPase assay, several compounds from this series were shown to inhibit ATP hydrolysis (e.g. compound 10), while others enhanced this activity (e.g. compound 11).159 Moreover, the activity of these compounds was dependent on the presence of a J-domain co-chaperone, similar to what had been seen with 9.158 For example, compound 10 had no effect on ATP hydrolysis by Hsc70 at up to 600 µM, but it gave a 4-fold reduction at 300 µM when added to the combination of Hsc70 and the J-domain of T-antigen.159 Approximately 30 compounds were tested in these experiments and, accordingly, quantitative SAR was not readily apparent. To further explore this series, seventeen additional dihydropyrimidines were synthesized in which the Ugi-derived peptoid portion was replaced with a protease-resistant, beta-peptide.160 The activity of these derivatives was tested against the ATPase activity of two Hsp70s (either Hsc70 or DnaK) in complex with a J-domain co-chaperone. The results of that study suggest that hydrophobic substitutions near the dihydropyrimidine core (R4; Figure 5) may be important for activity. For example, compounds 12 and 13, which have phenyl substitutions in this region, changed ATP turnover by between 20 and 45%.160 Interestingly, 12 was an inhibitor of ATPase activity, while 13 was a stimulator, consistent with the general observations that compounds of this class can have either type of activity when J-domains are present. Also, 13 only stimulated bovine Hsc70 and not E. coli DnaK, suggesting that these highly homologous proteins might be independently targeted. Despite these efforts, the potency of these compounds is very weak (EC50 values ~ 75 to 300 µM), making it challenging to interpret the SAR and to confirm selectivity for Hsp70 in cells. Part of the challenge, until recently, was that compounds had to be tested in small numbers because a high throughput assay for Hsp70’s ATPase activity had not been available. To improve this capacity, Chang et al. converted a malachite green assay into a high-throughput platform. Importantly, this assay employs purified DnaK and its co-chaperones, DnaJ, and GrpE, to boost the signal and provide physiological turnover rates.161 This advance allowed screening of a collection of more than 180 dihydropyrimidines and, from these efforts, several promising derivatives, such as 15, which blocks more than 80% of DnaK’s activity at 150 µM, were identified. To complement this approach, a medium throughput luciferase-refolding assay was developed. In this assay, denatured firefly luciferase is diluted in the presence of the three-component chaperone complex and refolding is monitored by recovered luminescence. The ~180 member dihydropyrimidine collection was screened in 96-well format and the best of these compounds, such as 16, had EC50 values around 4 µM.162 Interestingly, there was not obvious structural similarity between the active compounds from the ATPase assay and the luciferase-folding assay.

Figure 5. Structures of dihydropyrimidines with activity against Hsp70 family members.

Select compounds from larger series are shown for clarity. See the text for references.

Even though the dihydropyrimidines identified to date have weak activity and their selectivity remains to be established, the first-generation compounds have been employed in a variety of biological systems. Importantly, these studies have provided unexpected insights into Hsp70’s functions in disease models. In one example, the stimulatory dihydropyrimidine, 14, was found to enhance the Hsp70-mediated inhibition of amyloid-β aggregation.106 Conversely, a weak inhibitor of ATPase activity led to suppression, suggesting that the ATP hydrolysis rate of the chaperone might impact its anti-aggregation activity in vitro. To test this model in cells, Jinwal et al. used both inhibitors and activators of Hsp70’s ATPase activity in a model of tau aggregation.163 Surprisingly, they found that stimulators, including 14, led to dramatic accumulation of tau, while inhibitors had the opposite effect. The inhibitors reduced tau levels via rapid ubiquitination with EC50 values of ~5 to 10 µM. Importantly, over-expression of Hsp70 promoted the activity of the inhibitors and lowered their EC50 values, consistent with this chaperone as an important cellular target. Finally, intracranial injection was found to reduce tau in transgenic mice, which suggests that inhibiting the ATPase activity of Hsp70 might be a viable strategy for reducing the accumulation of misfolded tau.

In addition to these studies on protein misfolding and aggregation, dihydropyrimidines have also been employed to explore the potential of Hsp70 as a target in cancer. For example, compound 10 was found to have anti-proliferative activity against SKBr3 cells.164 This activity appears to be mediated by the ability of the dihydropyrimidines to interrupt stimulation of Hsp70 by J-protein co-chaperones, because the GI50 values for a series of peptoid-modified dihydropyrimidines tend to correlate with their activity in a J-stimulated ATPase assay.165 Moreover, the best compounds (of the nearly 50 derivatives tested) had promising GI50 values of approximately 6 to 10 µM against SKBR3 cells, suggesting the possibility that inhibition of Hsp70 alone is sufficient to induce apoptosis. To explore the potential mechanisms for anticancer activity, the effects of activators and inhibitors on stability of the pro-survival target, Akt, were explored.166 In that study, it was found that activators promote Akt stabilization, while inhibitors promote Akt degradation and subsequent cell death in a panel of cancer cells.166 This mechanism is similar to that proposed for Hsp90 inhibitors; namely, that selective destabilization of chaperone substrates leads to apoptosis.72 Because Hsp90 and Hsp70 often cooperate, it is not yet entirely clear what role Hsp90 might play in the response to the Hsp70 inhibitors. Further work is needed to understand the molecular mechanisms; however, these collective findings, across multiple models of protein misfolding and apoptosis, have begun to reveal potential avenues towards therapeutic intervention.

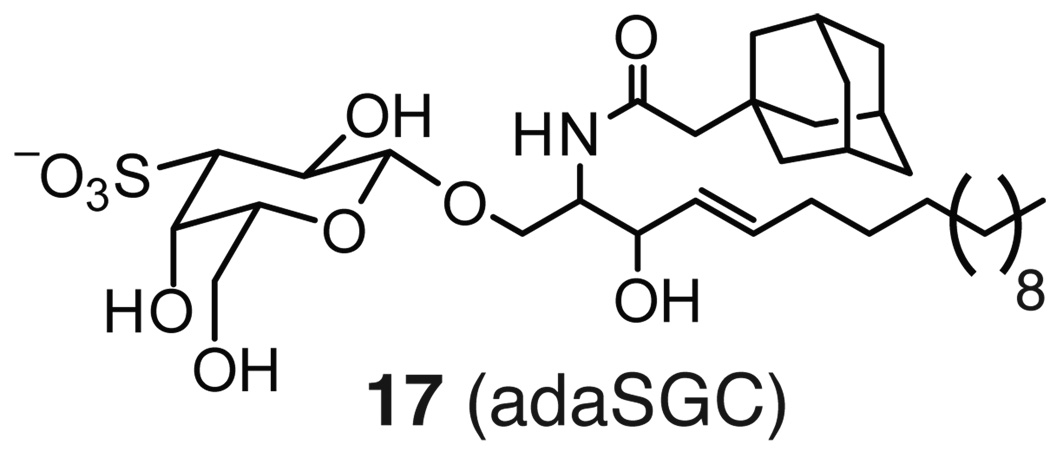

Fatty acids

Sulfogalactosyl ceramide and sulfogalactoglycerolipid are two sulfoglycolipids that have been found to bind Hsp70. Mamelak and Lingwood identified their putative binding site on the NBD through deletional analysis and site-directed mutagenesis; specifically, mutation of two residues in the NBD (Arg 342 and Phe 198) led to reduced binding of 3’sulfogalactolipid.167 It was further shown that the aglycone portion determines whether the molecules bind to bacterial or eukaryotic Hsp70s. Eukaryotic Hsp70 bound SG24Cer, SG18Cer, and SG20:OHCer while DnaK preferentially bound to SG18:1Cer and SG20:OHCer.168 Other substitutions on the aglycone or manipulations of the sulfation (or phosphorylation) pattern on the sugar ablated binding, demonstrating the narrow tolerance in these regions.169 A full SAR analysis of this class of molecules awaits expanded library synthesis and additional structural studies. However, early studies revealed that substituting the acyl chain with an adamantyl group improved affinity for Hsp70 (Figure 6). Specifically, 17 (adaSGC) was found to have an IC50 value of ~50 µM.167 Interestingly, 17 is a noncompetitive inhibitor of ATPase activity, but the molecular mechanism of inhibition is not entirely clear.170 In cells, 17 increases the protein levels of ΔF508CFTR,170 a mutant of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor (CFTR) that is prone to misfolding and degradation through ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Thus, this finding suggests that inhibition of Hsp70’s ATPase activity might suppress the ERAD pathway that normally acts to reduce the levels of mutated CFTR. Moreover, the activity of 17 was found to be dependent on the actions of both Hsp70 and a J-domain containing co-chaperone, consistent with this complex as a cellular target. These results might have important implications for the use of Hsp70 as a drug target in cystic fibrosis and other misfolding diseases. Despite these insights, the binding site for these glycolipids is only loosely defined and, further, their selectivity has yet to be firmly established.

Figure 6. Chemical structure of a representative sulfoglycolipid (adaSGC).

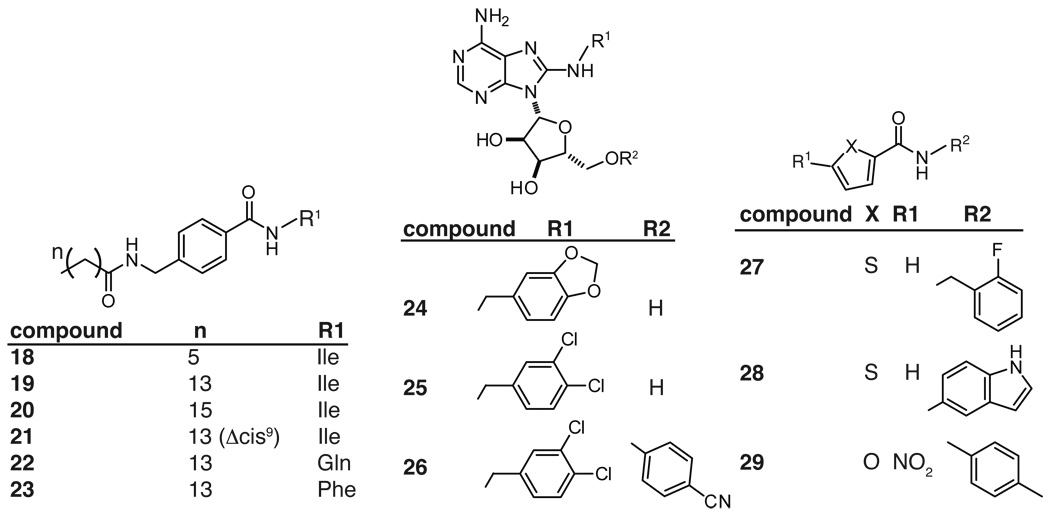

Another example of a fatty acid-like derivative that inhibits Hsp70 function is the acyl benzamide family. This class of compounds arose from work by the Schiene-Fisher group in which they targeted the cis/trans aminopeptidyl isomerase (APIase) activity of DnaK, in an effort to identify potential antibiotics. DnaK has been shown to catalyze isomerase activity through a poorly understood mechanism. Efforts to target this activity with small molecules yielded acyl benzamides with IC50 values as low as 2.7 µM.171 Further, they found that the length of the fatty acid chain is an important determinant of the molecule’s activity (Figure 7). For example, short acyl chains, such as those in 18, gave compounds with poor activity in both APIase and bacterial growth assays. Increasing the length of the chain tended to enhance potency: compound 19 had an IC50 in the APIase assay of 5 µM and an MIC against E. coli of 380 µg/mL, while 20 had an IC50 of 1.2 µM and MIC of 180 µg/mL. However, increasing the fatty acid chain-length also enhanced undesirable erythrocyte hemolytic activity. Hemolytic activity could be partially avoided by installation of unsaturations in the fatty acid; for example, compound 21, with a cis alkene at C9, had an EC50 >1500 µg/mL in the hemolytic assay, while it retained activity against APIase (36 µM) and bacterial growth (280 µg/mL). Substitutions in the amino acid portion (R1; Figure 7) altered the MIC values, with less predictable effects in the other in vitro assays.171 For example, dramatic substitutions of the isoleucine for a glutamine (22) or phenylalanine (23) caused modest changes in APIase inhibition but they increased the MIC by approximately 3- to 7-fold. Together, these findings suggest that the in vitro activity assays proscribed to Hsp70 might not best reflect the key mechanistic roles played by this chaperone in bacteria. This is a re-occurring theme in the Hsp70 field because the roles of measurable Hsp70 functions (e.g. ATPase, APIase, refolding, etc.) in controlling its biology in vivo remain uncertain. Despite this discrepancy, the MIC of the best acyl benzylamide is approximately 7-fold lower than that of ampicillin, which suggests that these compounds or their derivatives may be useful. However, it is important to note that their selectivity for Hsp70 has not been formally established and any off-target effects of these compounds remain unexplored.

Figure 7. Chemical structures of Hsp70 inhibitors.

Select compounds from larger series are shown for clarity. See the text for references.

Peptides

As mentioned above, DnaK is considered a potential target for anti-bacterials, but this model has only recently been tested with pharmacological agents. For example, a series of 18–20 amino acid, proline-rich peptides, including drosocin, pyrrhocoricin, and apidaecin (Table 4), were described that bind DnaK (and another prokaryotic chaperone, GroEL) and kill susceptible bacteria without impacting mammalian cells.172 Pyrrhocoricin inhibits the ATPase activity of E. coli DnaK and it binds in the SBD with a Kd of 50 µM.173 This interaction is thought to keep the “lid” domain in the closed position, preventing substrate release, a model supported by computational simulations and mutagenesis studies, which identified the SBD residues Glu589, Gln595, and Met598 as the key targets in DnaK.174 Interestingly, pyrrhocoricin does not bind to S. aureus DnaK,173 suggesting a potential difference between gram-positive and −negative strains. In an effort to optimize the pharmacokinetics and antibacterial activity of these peptides, several analogues representing combinations of the peptide sequences were generated. Of these derivatives, GRPDKPRPYLPRPRPPRPVRL is the most active and it also has improved serum stability.175 Importantly, this compound has activity against both E. coli and a resistant strain of Enterobactericeae sp., with an MIC approximately 4 times better than ciprofloxacin. Moreover, it was not toxic to eukaryotic cells at concentrations up to 1.5 mg/mL.175 Cudic et al. recently generated dimers of pyrrhocoricin in an effort to further improve stability and potency. Some of these compounds have increased serum stability compared to pyrrhocoricin and activity against isolates normally resistant to β-lactams, tetracycline, or aminoglycosides.176 While these compounds have not advanced to the clinic, they have shown that targeting DnaK may be a viable anti-bacterial strategy.

Table 4.

Sequences of Anti-Bacterial Peptides Targeting DnaK

| Peptide | sequence |

|---|---|

| drosocin | GKPRPYSPRPTSHPRPIRV |

| apidaecin | GNNRPVYIPQPRPPHPRI |

| pyrrhocoricin | VDKGSYLPRPTPPRPIYNRN |

ATP mimics

Given that Hsp70’s ATPase activity appears to be one central determinant of chaperone function, compounds that are competitive for binding to ATP might be expected to have potent activity. This hypothesis arises, in part, from analogy with Hsp90, in which ATP competitive compounds, such as geldanamycin derivatives, induce degradation of Hsp90 substrates. Recently, Williamson et al. published the first compounds that can be used to test this important hypothesis in Hsp70. Using a fluorescence polarization assay, they screened adenosine derivatives and identified 8-amino adenosines with affinity for the ATP-binding site, with the most active (24) having an IC50 of 4.9 µM (Figure 7).177 The intended binding orientation was confirmed by a co-crystal structure. Further, when the 8-amino group was substituted with 3,4-dichlorobenzyl (25), it retained activity (IC50 ~ 9.1 µM) and had an improved toxicity profile. Subsequent modifications optimized the π-stacking with residues in Hsc70 and the 5-substituent (R2; Figure 7) was further substituted with a 4-cyanophenyl group to yield a tight binding compound 26 (IC50 value of 0.5 µM). Importantly, 26 also had activity against HCT 116 colon carcinoma cells (GI50 of 5 µM) and it reduced the levels of Her2, a substrate that is sensitive to Hsp70 knockdown.177 Most recently, compounds from this class were also found to have synergy with an Hsp90 inhibitor in HCT116 cells,178 which might be expected based on shared functions of these chaperones. Together, these studies represent an important step towards submicromolar affinities and structure-guided design of Hsp70 inhibitors.

Thiophene-2-carboxamides

Celliti et al. recently used NMR spectroscopy to identify compounds that bind to DnaK.179 They specifically explored the protons in the aliphatic region of the 1D 1H NMR spectra of E. coli DnaK SBD (residues 393–507) in an effort to find scaffolds that interact with that domain. These efforts yielded a pocket near Leu484 and Pro419, which forms a groove important for allosteric communication between the SBD and the NBD. The compounds that bound this site were principally thiophene-2-carboxamides, such as 27, and their binding was confirmed by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), with Kd values around 70 µM. Based on these results, fifteen derivatives with either a thiophene or furan core and a variety of hydrophobic groups appended to the 2-position were synthesized (Figure 7). Adding bulk to the R2 substituent seemed to improve affinity and these efforts yielded the indole-substituted 28, which bound with a Kd of 12.7 µM. Finally, members of this series of compounds were found to inhibit growth of E. coli and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, with MIC values of approximately 10 to 400 µM depending on the strain and growth temperature. The best compound was the 2-substituted furan 29, which had an MIC of less than 12 µM against Y. pseudotuberculosis at 40 °C. Interestingly, the most potent inhibitor of microbial growth was not the compound with the highest affinity to DnaK as determined by ITC, again suggesting a complex relationship between Hsp70 binding and in vivo potency.

Phenylethynesulfonamide

Recently, Leu and colleagues reported the identification of 2-phenylethynesulfonamide (30) as a compound that binds Hsp72 (Figure 8).180 Compound 30 (also known as Pfithrin-μ) has been shown to be selectively toxic to cancer cell lines and it was proposed effect p53, but its mechanism of action had not been clear. Biotin-conjugated PES revealed Hsp72 (but not Hsc70, BiP or Hsp90) as a target and deletional analysis further restricted the binding site to the C-terminus.180 Using immunoprecipitations, the authors characterized the effects of 30 on assembly of the Hsp70 chaperone complex in different cell lines. They hypothesized that 30 would alter co-chaperone associations with Hsp72 and, thereby, alter chaperone functions. These studies revealed that 30 prevents the interaction between Hsp72 and some BAG proteins, depending on the cell type. Moreover, 30 blocks association of Hsp72 with p53, consistent with the ability of 30 to kill cancer cells and block caspase activation. Finally, 30 appears to interrupt the interaction of Hsp72 and LAMP2, an important protein in chaperone-mediated autophagy. Consistent with this idea, long-lived proteins are degraded at a reduced rate in response to 30 and this compound causes build up of procathespin L, indicating that autophagy and lysosomal enzyme processing are impaired.180 Together, these studies suggest that 30 changes the interactions of Hsp70 with some of its co-chaperone partners and, through this activity, impacts substrate fate. Moreover, 30 has a relatively simple structure and it seems likely that additional synthetic studies might improve its activity and, potentially, its selectivity. Those efforts will likely benefit from improved structural analysis and further biophysical studies on the mechanism for changes in Hsp70 complex assembly.

Figure 8. Chemical structures of miscellaneous Hsp70 inhibitors.

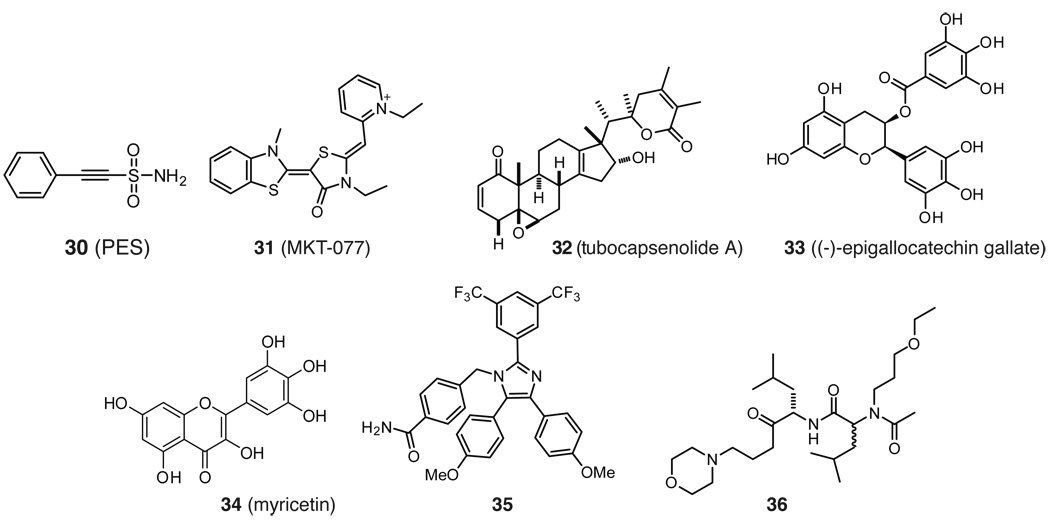

MKT-077

The rhodacyanine 31 (MKT-077; Figure 8), has been reported to bind to mtHsp70 in pull-down studies.181, 182 More specifically, deletion analysis revealed that 31 binds near the ATP-binding site of the mtHsp70 NBD. However, the cellular selectivity of mtHsp70 over other Hsp70 isoforms is likely driven, in part, from its cationic character. Cationic compounds are known to accumulate across the mitochondrial proton gradient in rapidly dividing cancer cells. In early experiments, 31 was found to inhibit proliferation of multiple human cancer cell lines, including colon, bladder and breast carcinoma cells, with IC50 values ranging from 1 to 5 µM with no toxicity against normal kidney cells.183 Based on these findings, pre-clinical evaluation in rats revealed low toxicity below 3 mg/kg/day and primarily renal impairment above that dose. In mouse xenograft studies, continuous infusion was required for anti-tumor activity.184 Based on the preclinical findings, a Phase I clinical trial against solid tumors was performed using daily infusions carried out five times over three weeks at 30–50 mg/m2/day.185 In a subset of these patients, renal toxicity was again seen as the major toxicity. Importantly, pharmacokinetic measurements failed to detect 31 above one micromolar in the serum, suggesting that therapeutic dose was not achieved. Consistent with this, little improvement in disease was seen (1 out of 10 patients achieved stable disease).185 However, these studies suggest that targeting mitochondrial Hsp70 might be a viable strategy if the toxicity and pharmacokinetics of this scaffold could be improved. In addition, more detail about the selectivity and mtHsp70-binding activity of this compound might guide these efforts.

Other Examples

Included in a comprehensive list of compounds with activity on Hsp70 are several molecules that are either recently discovered or older ones that await further study. For example, the steroid-like molecule 32 (tubocapsenolide A) was found to oxidize thiols on both Hsp70 and Hsp90, causing their inactivation.186 Also, there are several reports suggesting that 33 ((−)-epigallocatechin gallate) can inhibit Hsp70s, including BiP, allowing initiation of apoptotic pathways.187–189 Likewise, the flavonoid 34 (myricetin) inhibits the ATPase activity of Hsp70s, reduces tau levels and has anti-cancer activity in multiple models.163, 166 It should be clearly noted that polyphenols, such as 33 and 34, are notoriously promiscuous. However, uncovering their binding site(s) and mechanism(s) on Hsp70 might reveal new “druggable” sites and opportunities for structure-guided design. Recently, an imidazole 35 was reported by Williams et al. to induce apoptosis through interactions with Hsp70 and Hsc70190 and Haney et al. reported that Ugi-derived peptoids, such as 36, modulate Hsp70’s ATPase activity by up to 40% through binding to the SBD.191 Finally, peptides derived from BAG1 were shown to inhibit the BAG1-Hsc70 interaction and inhibit proliferation of breast cancer cells.192 These last results further emphasize the important contribution of co-chaperones in guiding the activity of the Hsp70 complex. While much work remains to optimize these compounds and establish their selectivity for Hsp70, they provide an illustration of the wide diversity of structures found to interact with this chaperone.

Analysis and Prospectus

Hsp70 is a critical molecular chaperone in cell survival signaling and protein homeostasis. As such, it has gathered significant attention as a potential, emerging drug target.44, 67, 129, 130 Genetic studies (e.g. knockdown and over-expression) have clearly demonstrate that Hsp70 and its co-chaperones are involved in cancer, neurodegeneration and other diseases. The next steps are to determine if the various functions of Hsp70 can be pharmacologically manipulated and, further, whether the outcomes of this intervention will be well tolerated. On first glance, targeting of a core mediator of protein homeostasis might be considered challenging, given its widespread cellular roles and ample opportunities for toxicity. In part, enthusiasm for Hsp70 as a drug target is based on the success of programs targeting other core molecular chaperones, such as Hsp90.67 As mentioned above, Hsp90 inhibitors specifically destabilize pro-survival signaling proteins in cancer cells and the results of early anti-cancer trials appear promising. However, the field of Hsp70 inhibitors is less mature and many, important questions remain before Hsp70 can be considered an equally good drug target.

In this review, we have discussed some of the early efforts to identify inhibitors of Hsp70 and highlighted some of the biological findings enabled by these reagents. However, many questions remain before Hsp70 can be considered a fully validated drug target. For example, there are multiple assays used to measure Hsp70 activity in vitro (e.g. ATPase activity, APIase activity, substrate folding, anti-apoptotic signaling, etc) and the relationships between any of these measurable functions and the chaperone roles of Hsp70 in vivo remain unclear. Additionally, there is a general lack of selectivity information for the first-generation, Hsp70-targeted compounds. Thus, it seems likely that at least some of these compounds are enacting their cellular activities through multiple pathways, which precludes definitive statements on Hsp70 as a drug target.

Clearly, one of the major problems in the field is that consensus assays for studying Hsp70 are lacking. By analogy, Hsp90 inhibitors are often tested against a battery of standard assays, including those that measure chaperone binding in vitro and the ability to reduce the levels of Hsp90 substrates, such as Akt, Cdk4, Raf and Her2, in cells.74 Future efforts on Hsp70 will benefit from similar, routine utilization of (a) in vitro binding assays, (b) examination of cellular effects on putative Hsp70 substrates, such as tau, Akt and Her2, and (c) studying the effects of Hsp70 over-expression on compound efficacy. This last point is particularly important because, in our opinion, the interpretation of pull-down studies (which are often used to document Hsp70 binding in cells) are complicated by both the hydrophobic promiscuity of this chaperone and its abundance. Thus, over-expression studies may provide a more readily interpretable alternative. Another interesting approach is transcriptional profiling, which was previously used to identify novel Hsp90 inhibitor.193 Finally, a greater emphasis on structural studies seems warranted, to permit insights into the binding sites of putative Hsp70 inhibitors. In the Hsp90 field, extensive crystallography studies have yielded important molecular details into the binding sites. As the field of Hsp70 inhibitors matures, increasing utilization of structural analysis and broader assay profiling will ultimately accelerate discovery.

It is interesting to note that a wide variety of chemical scaffolds (e.g. polyamines, fatty acids, sulfoglycolipids, peptides, adenosines, etc.) have been identified with affinity for Hsp70. Although some of these scaffolds are likely promiscuous, this observation still suggests that Hsp70 harbors an unusual number of potential drug-binding sites that can accommodate a variety of chemical scaffolds. These sites might include deep pockets, such as those found in the ATP-binding cleft and substrate-binding region, and more shallow surfaces, such as those involved in allostery and protein-protein interactions with co-chaperones. Although not all of the compounds discussed herein have been explored in sufficient molecular detail, the early findings suggest that there are multiple ways to impact Hsp70’s functions. For example, compounds 9, 10, 14, 30 and the BAG1-related peptides seem to interrupt Hsp70’s contacts with co-chaperones, while 26 directly competes for nucleotide binding.

One interesting aspect of Hsp70 biology that remains to be more fully leveraged is the ability of this chaperone to form multi-protein complexes. As discussed above, Hsp70 interacts with multiple classes of co-chaperones and these partners are known to shape its activities. Thus, specifically targeting the interactions between Hsp70 and its regulatory partners would be expected to control specific chaperone activities.8 This approach might be expected to have more limited toxicity because of reduced global impairment of protein homeostasis. Moving forward, we propose that an emphasis on the structural biology of co-chaperones, combined with a deeper insight into how these factors shape the proteome, will be required to rationally leverage Hsp70 as an effective drug target.

In summary, genetic and biochemical studies support Hsp70 as an interesting, potential drug target in a remarkably wide range of diseases. Early studies on Hsp70 inhibitors support this general conclusion. However, the field of Hsp70 inhibitors is clearly in its infancy and extensive work remains before it is clear how this chaperone can be best exploited.

Table 3.

Roles of Hsp70 in Infection and Immunity

| Disease/Process | Role of Hsp70 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Infection | ||

| Invasion | Mutations in DnaK make S. aureus less infective and inhibit biofilm formation in S. mutans |

118, 120, 218 |

| S. enterica DnaK required for invasion of epithelial cells | 123 | |

| Hsc70 enhances internalization of Brucella by trophoblasts | 219 | |

| H. pylori Hsp70 allows for its attachment to the gastric epithelia | 220 | |

| Survival | DnaK mutants are susceptible to stress | 117–120 |

|

S. enteric and L. monocytogenes DnaK required for survival in macrophages |

123, 124 | |

| Over-expression of Hsp70 in M. tuberculosis reduces survival during the chronic phase of infection |

221 | |

| Replication | DnaK necessary for replication of Brucella suis in macrophages | 222 |

|

Immune System Evasion |

Hsp70 protects macrophages from cell death when infected with Salmonella choleraesuis |

125 |

| Immune Function | ||

|

Antigen Presentation |

Hsp70s involved in MHC class II antigen presentation and endocytic maturation |

223, 224 |

| Viral Infection | ||

|

Cell Entry and Exit |

Hsc70 involved in rotavirus entry into cells Hsp70 involved in the disassembly of Polyomavirus and Papillomaviruses in mouse cells |

225, 226 227 |

| Replication | Hsp70 associates with RSV polymerase complex in lipid rafts | 228 |

| Interaction between Hsc70 and T-antigen required for the replication of Simian Virus 40 |

229–233 | |

| Hsp72 involved in Epstein-Barr virus replication | 234 | |

| Hsp70 can replace viral protein R in the pre-integration complex of HIV |

235 | |

| Immune Response | Hsp70 prevents cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in HIV infected cells | 236 |

| Viral Assembly | Hsp70 is associated with capsid formation in Polyomavirus and Papillomaviruses |

237 |

Acknowledgements

Our work on Hsp70 is supported by grants NS059690 and MCB-0844512 (to J.E.G.). C.G.E. is supported by a pre-doctoral fellowship (GM008353). The authors thank Erik Zuiderweg and members of the Gestwicki laboratory for helpful conversations and ideas.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- Apaf-1

apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1

- APIase

cis/trans aminopeptidyl isomerase

- BAG

Bcl-2-associated anthogene

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane receptor

- CHIP

C-terminal of Hsc70 interacting protein

- 15-DSG

15-deoxyspergualin

- ERAD

ER-associated degradation

- Hsc70

Heat shock cognate 70

- HSF1

Heat shock factor 1

- Hsp70

Heat shock protein 70

- HSBP1

Hsp70 binding protein 1

- HOP

Hsp70 organizing protein

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- IL-10

interleukin 10

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

- mtHsp70

mitochondrial HSP70

- NFT

neurofibrillary tangles

- NBD

Nucleotide binding domain

- NEF

Nucleotide exchange factor

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor

- PES

phenylethynesulfonamide

- polyQ

polyglutamine

- SAR

structure-activity relationships

- SBMA

spinal and bulbar muscular dystrophy

- SBD

substrate binding domain

- SCA

spinocerebellar ataxia

- Ssa1

stress seventy subfamily A

- TPR

Tetratricopeptide repeat

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

Biographies

Christopher G. Evans graduated from the University of Florida with both his B.S. (2001) and Pharm.D. (2005). He then joined the Chemical Biology Ph.D. program at the University of Michigan. His thesis work in Professor Jason Gestwicki’s laboratory involves the synthesis of new Hsp70 modulators, with a focus on multi-component reactions.

Lyra Chang received her bachelor's degree at Tzu Chi University (Taiwan) and completed her master’s degree in National Tsing Hua University (Taiwan) under the direction of Professor Suh-Chin Wu working on improving the mammalian cell-based expression of SARS-CoV spike protein. In 2006, she entered the Chemical Biology Ph.D. program at University of Michigan. Her thesis work in Professor Jason Gestwicki’s group is focused on discovering chemical modulators of Hsp70s via high-throughput screening and characterizing the mechanisms of those compounds.

Jason E. Gestwicki earned a Ph.D. in Biochemistry with Professor Laura L. Kiessling at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2002. His thesis work involved using synthetic, multivalent ligands with defined architecture to probe how receptor clustering controls signal transduction. He then performed post-doctoral work with Professor Gerald R. Crabtree at Stanford University before starting his independent group at the University of Michigan in 2005. His research interests are in chemical biology and the manipulation of protein-protein interactions with synthetic probes.

References

- 1.Mayer MP, Bukau B. Hsp70 chaperones: cellular functions and molecular mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:670–684. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schaffitzel E, Rudiger S, Bukau B, Deuerling E. Functional dissection of trigger factor and DnaK: interactions with nascent polypeptides and thermally denatured proteins. Biol Chem. 2001;382:1235–1243. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:603–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratt WB, Toft DO. Regulation of signaling protein function and trafficking by the hsp90/hsp70-based chaperone machinery. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:111–133. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young JC, Barral JM, Ulrich Hartl F. More than folding: localized functions of cytosolic chaperones. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang HL, Terlecky SR, Plant CP, Dice JF. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science. 1989;246:382–385. doi: 10.1126/science.2799391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bercovich B, Stancovski I, Mayer A, Blumenfeld N, Laszlo A, Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of certain protein substrates in vitro requires the molecular chaperone Hsc70. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9002–9010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meimaridou E, Gooljar SB, Chapple JP. From hatching to dispatching: the multiple cellular roles of the Hsp70 molecular chaperone machinery. J Mol Endocrinol. 2009;42:1–9. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daugaard M, Rohde M, Jaattela M. The heat shock protein 70 family: Highly homologous proteins with overlapping and distinct functions. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3702–3710. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertelsen EB, Chang L, Gestwicki JE, Zuiderweg ER. Solution conformation of wild-type E. coli Hsp70 (DnaK) chaperone complexed with ADP and substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8471–8476. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903503106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flaherty KM, DeLuca-Flaherty C, McKay DB. Three-dimensional structure of the ATPase fragment of a 70K heat-shock cognate protein. Nature. 1990;346:623–628. doi: 10.1038/346623a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. An ATPase domain common to prokaryotic cell cycle proteins, sugar kinases, actin, and hsp70 heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:7290–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X, Zhao X, Burkholder WF, Gragerov A, Ogata CM, Gottesman ME, Hendrickson WA. Structural analysis of substrate binding by the molecular chaperone DnaK. Science. 1996;272:1606–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erbse A, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Mechanism of substrate recognition by Hsp70 chaperones. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:617–621. doi: 10.1042/BST0320617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xing Y, Bocking T, Wolf M, Grigorieff N, Kirchhausen T, Harrison SC. Structure of clathrin coat with bound Hsc70 and auxilin: mechanism of Hsc70-facilitated disassembly. EMBO J. 2010;29:655–665. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flynn GC, Pohl J, Flocco MT, Rothman JE. Peptide-binding specificity of the molecular chaperone BiP. Nature. 1991;353:726–730. doi: 10.1038/353726a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell R, Jordan R, McMacken R. Kinetic characterization of the ATPase cycle of the DnaK molecular chaperone. Biochemistry. 1998;37:596–607. doi: 10.1021/bi972025p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayer MP, Schroder H, Rudiger S, Paal K, Laufen T, Bukau B. Multistep mechanism of substrate binding determines chaperone activity of Hsp70. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:586–593. doi: 10.1038/76819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vogel M, Mayer MP, Bukau B. Allosteric regulation of Hsp70 chaperones involves a conserved interdomain linker. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38705–38711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han W, Christen P. Mutations in the interdomain linker region of DnaK abolish the chaperone action of the DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE system. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:55–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02435-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ha JH, McKay DB. ATPase kinetics of recombinant bovine 70 kDa heat shock cognate protein and its amino-terminal ATPase domain. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14625–14635. doi: 10.1021/bi00252a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laufen T, Mayer MP, Beisel C, Klostermeier D, Mogk A, Reinstein J, Bukau B. Mechanism of regulation of hsp70 chaperones by DnaJ cochaperones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5452–5457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu XB, Shao YM, Miao S, Wang L. The diversity of the DnaJ/Hsp40 family, the crucial partners for Hsp70 chaperones. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2560–2570. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall D, Zylicz M, Georgopoulos C. The NH2-terminal 108 amino acids of the Escherichia coli DnaJ protein stimulate the ATPase activity of DnaK and are sufficient for lambda replication. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5446–5451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene MK, Maskos K, Landry SJ. Role of the J-domain in the cooperation of Hsp40 with Hsp70. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang J, Maes EG, Taylor AB, Wang L, Hinck AP, Lafer EM, Sousa R. Structural basis of J cochaperone binding and regulation of Hsp70. Mol Cell. 2007;28:422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierpaoli EV, Sandmeier E, Baici A, Schonfeld HJ, Gisler S, Christen P. The power stroke of the DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE molecular chaperone system. J Mol Biol. 1997;269:757–768. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrison C. GrpE, a nucleotide exchange factor for DnaK. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2003;8:218–224. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2003)008<0218:ganeff>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabbage M, Dickman MB. The BAG proteins: a ubiquitous family of chaperone regulators. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:1390–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-7535-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabani M, McLellan C, Raynes DA, Guerriero V, Brodsky JL. HspBP1, a homologue of the yeast Fes1 and Sls1 proteins, is an Hsc70 nucleotide exchange factor. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:339–342. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaner L, Morano KA. All in the family: atypical Hsp70 chaperones are conserved modulators of Hsp70 activity. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2007;12:1–8. doi: 10.1379/CSC-245R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bukau B, Weissman J, Horwich A. Molecular chaperones and protein quality control. Cell. 2006;125:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vos MJ, Hageman J, Carra S, Kampinga HH. Structural and functional diversities between members of the human HSPB, HSPH, HSPA, and DNAJ chaperone families. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7001–7011. doi: 10.1021/bi800639z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kota P, Summers DW, Ren HY, Cyr DM, Dokholyan NV. Identification of a consensus motif in substrates bound by a Type I Hsp40. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11073–11078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900746106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blatch GL, Lassle M. The tetratricopeptide repeat: a structural motif mediating protein-protein interactions. Bioessays. 1999;21:932–939. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<932::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheufler C, Brinker A, Bourenkov G, Pegoraro S, Moroder L, Bartunik H, Hartl FU, Moarefi I. Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell. 2000;101:199–210. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrigan PE, Nelson GM, Roberts PJ, Stoffer J, Riggs DL, Smith DF. Multiple domains of the co-chaperone Hop are important for Hsp70 binding. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16185–16193. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flom G, Behal RH, Rosen L, Cole DG, Johnson JL. Definition of the minimal fragments of Sti1 required for dimerization, interaction with Hsp70 and Hsp90 and in vivo functions. Biochem J. 2007;404:159–167. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernandez MP, Sullivan WP, Toft DO. The assembly and intermolecular properties of the hsp70-Hop-hsp90 molecular chaperone complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38294–38304. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206566200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onuoha SC, Coulstock ET, Grossmann JG, Jackson SE. Structural studies on the co-chaperone Hop and its complexes with Hsp90. J Mol Biol. 2008;379:732–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Connell P, Ballinger CA, Jiang J, Wu Y, Thompson LJ, Hohfeld J, Patterson C. The co-chaperone CHIP regulates protein triage decisions mediated by heat-shock proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:93–96. doi: 10.1038/35050618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballinger CA, Connell P, Wu Y, Hu Z, Thompson LJ, Yin LY, Patterson C. Identification of CHIP, a novel tetratricopeptide repeat-containing protein that interacts with heat shock proteins and negatively regulates chaperone functions. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4535–4545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hohfeld J, Cyr DM, Patterson C. From the cradle to the grave: molecular chaperones that may choose between folding and degradation. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:885–890. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mosser DD, Morimoto RI. Molecular chaperones and the stress of oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:2907–2918. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ciocca DR, Calderwood SK. Heat shock proteins in cancer: diagnostic, prognostic, predictive, and treatment implications. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2005;10:86–103. doi: 10.1379/CSC-99r.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohde M, Daugaard M, Jensen MH, Helin K, Nylandsted J, Jaattela M. Members of the heat-shock protein 70 family promote cancer cell growth by distinct mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2005;19:570–582. doi: 10.1101/gad.305405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seo JS, Park YM, Kim JI, Shim EH, Kim CW, Jang JJ, Kim SH, Lee WH. T cell lymphoma in transgenic mice expressing the human Hsp70 gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;218:582–587. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sliutz G, Karlseder J, Tempfer C, Orel L, Holzer G, Simon MM. Drug resistance against gemcitabine and topotecan mediated by constitutive hsp70 overexpression in vitro: implication of quercetin as sensitiser in chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:172–177. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]