Abstract

Binding to the extracellular matrix (ECM), one of the most abundant human protein complexes, significantly affects drug disposition. Specifically, the interactions with ECM determine the free concentrations of small molecules acting in tissues, including signaling peptides, inhibitors of tissue remodeling enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and other drug candidates. The nature of ECM binding was elucidated for 63 MMP inhibitors, for which the association constants to an ECM mimic were reported here. The data did not correlate with lipophilicity as a common determinant of structure-nonspecific, orientation-averaged binding. A hypothetical structure of the binding site of the solidified ECM surrogate was analyzed using the Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), which needed to be applied in our multi-mode variant. This fact indicates that the compounds bind to ECM in multiple modes, which cannot be considered as completely orientation-averaged and exhibit structural dependence. The novel CoMFA models, exhibiting satisfactory descriptive and predictive abilities, are suitable for prediction of the ECM binding for the untested chemicals, which are within applicability domains. The results contribute to a better prediction of the pharmacokinetic parameters such as the distribution volume and the tissue-blood partition coefficients, in addition to a more imminent benefit for the development of more effective MMP inhibitors.

Keywords: extracellular matrix - ECM; matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors; Comparative Molecular Field Analysis - CoMFA; 3D-QSAR, multiple binding modes; tissue accumulation; disposition; pharmacokinetics

Introduction

The involvement of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in extracellular homeostasis and signaling, as well as in etiology of cancer and other diseases, turned out to be more complex than originally assumed. Recent reviews show that among about two dozens of human MMPs, only MMP-1, -2, and -7 can be considered validated anti-cancer targets. Inhibition of some other MMPs, such as MMP-3, -8, and -12, results in promotion of tumorigenesis, at least in some stages of the disease, and may outweigh the benefits of the target inhibition (1,2). For more success than in the last two decades, the development of MMP inhibitors as anti-cancer drug candidates must reflect these findings and consider other aspects, such as the complexity of the protease system in the cell (2), slow inhibition (3, 4), and pharmacokinetics of the inhibitors (5). In vivo, the desired selective suppression of the malignant MMP activities, while keeping the anti-target MMPs intact, is an outcome of the interplay between two dynamic processes: the disposition of the inhibitor in the tumor microenvironment and the inhibitory action.

One of the processes directly affecting the free inhibitor concentrations in the MMP surroundings is the binding to the extracellular matrix (ECM), the most abundant protein component in the extracellular space. ECM consists mainly of laminin and collagen IV, which account for roughly 90% of the ECM ’s dry mass (6). The extent of the ECM binding of drugs acting in tissues needs to be well balanced to ensure that there is (i) a sufficient free drug concentration available for the targeted action, and (ii) a depot (buffer) effect present, maintaining the drug concentration for certain time period, which is especially important for slow-acting inhibitors. The understanding of the ECM binding in terms of structure and properties of inhibitors would greatly enhance the development of tailored inhibitors of MMPs and other tissue targets. Towards this goal, we recently developed a method for the measurement of the binding to a commercially available ECM surrogate, Matrigel, using a reconstituted ECM layer at the bottom of the vials (7). After adequate hydration of the solidified Matrigel, the dissolved drug was added and its free equilibrium concentration was determined following the 2-hr incubation. In this study, the ECM binding affinities of 63 MMP inhibitors, built around three structural scaffolds, were determined. The nature of the ECM binding was elucidated by the analysis of both property-based and 3-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR).

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Matrigel from one batch was purchased from BD Biosciences, Labware Discovery, Bedford, MA. All reagents including Bradford reagent, borate buffer species, and all solvents (analytical or spectroscopy grade) were purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO. The tested chemicals (Table 1) were synthesized and described previously: 1–13 (8); 14–16 (9); 17–37 from the precursor pyrazolidinones (10) as described for 17–21 (10) and 22, 23 (11), or by simple derivatization of the corresponding amines (11) for 24–26, such as benzoylation for 27–31, and phenylsulfonylation for 32–37; 38, 39 (12); and 40–62 (13). Compound 63 (GM6001, galardin, ilomastat) was purchased from Biomol International, Plymouth Meeting, PA.

Table 1.

Structures, Properties, and Binding Affinities of the Studied Compounds for Solidified (Ks) and Dissolved (Kd) ECM Proteins.

| No. | Sk.a | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | logP | logKsb | logKdb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp±SD | CoMFAc | exp±SD | CoMFAc | |||||||||

| st. | MM | st. | MM | |||||||||

| 1 | A | CH2=CH- | (S)-CH2OH | (S) -CH=CH2 | NAd | 2.27 | 0.69±0.01 | 0.47 | 0.17 | 3.80±0.01 | 2.58 | 3.33 |

| 2 | A | Ph-O-Ph-CH2- | (S)-CH2OH | (S) -CH=CH2 | NA | 2.64 | 0.06±0.09 | −0.05 | 0.17 | 3.54±0.18 | 2.56 | 3.50 |

| 3 | A | -(CH2)6CH3 | (S)-CH2OH | (S)-CH=CH2 | NA | 2.56 | 0.2±0.18 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 2.91±0.04 | 2.56 | 2.85 |

| 4 | A | Ph-CH=CH- | (S)-CH2OH | (S)- CH=CH2 | NA | 2.46 | −0.16±0.01 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.47±0.03 | 2.53 | 2.11 |

| 5e | A | Ph-CH=CH- | (R)-CH2OH | (R)-CH=CH2 | NA | 2.45f | 0.01±0.09 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 3.30±0.13 | 2.52 | 3.16 |

| 6 | A | 4-Ph-Ph- | (R)-CH2S-Ph | (S)-CH=CH2 | NA | 1.08f | 0.79±0.01 | 0.66 | 0.78 | 2.91±0.09 | 2.71 | 3.21 |

| 7 | A | 4-Cl-Ph- | (S)-CH2OH | (S)-CH2CH2OH | NA | 2.37 | −0.38±0.01 | −0.24 | −0.13 | 2.71±0.03 | 2.50 | 3.40 |

| 8 | A | 4-Ph-Ph | (S)-CH2S-CO-CH3 | (R)-CH=CH2 | NA | 2.57f | −0.05±0.01 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 2.44±0.19 | 2.56 | 2.50 |

| 9 | A | Ph-CH=CH- | (R)-CH2S-Ph | (S)-CH=CH2 | NA | 2.78 | −0.10±0.07 | 0.19 | 0.08 | 2.68±0.30 | 2.69 | 2.62 |

| 10 | A | 4-Cl-Ph- | (R)-CH2S-Ph | (S)-CH=CH2 | NA | 2.84 | 0.52±0.29 | 0.40 | 0.15 | 4.09±0.05 | 2.76 | 3.45 |

| 11e | A | 4-Br-Ph- | (R)-CH2S-Ph | (S)-CH=CH2 | NA | 2.86 | 0.31±0.19 | 0.41 | 0.01 | 3.93±0.17 | 2.76 | 3.72 |

| 12 | A | Ph- | (R)-CH2OH | (R)-C(=CH2)CH3 | NA | 2.24f | −0.65±0.01 | −0.48 | −0.73 | 2.29±0.07 | 2.63 | 2.20 |

| 13 | A | (4-Ph-CH2O(CO)O)-Ph- | (R)-CH2OH | (R)-C(=CH2)CH3 | NA | 2.46 | −0.78±0.12 | −1.06 | −0.77 | 2.57±0.16 | 3.07 | 2.55 |

| 14 | A | Ph(CH2)2CO-NH-CH2- | -COOH | H | NA | 2.37 | −0.92±0.03 | −1.31 | −0.95 | 2.53±0.17 | 2.01 | 2.40 |

| 15 | A | Ph-CH2CO-NH-CH2- | -COOH | H | NA | 2.41 | −0.24±0.02 | −0.28 | −0.22 | 3.74±0.03 | 3.08 | 3.71 |

| 16 | A | HC≡C-CH2CO-NH-CH2- | -COOH | H | NA | 2.22 | −1.21±0.10 | −0.77 | −1.22 | 2.20±0.14 | 1.87 | 2.35 |

| 17 | B | CH3CH=CH-CO- | Ph-CH2- | −CH2CH2CH2CH2- | 2.36 | −0.57±0.03 | −0.52 | −0.65 | 1.76±0.16 | 3.08 | 1.89 | |

| 18 | B | CH3CH=CH-CO- | Ph-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.10 | 1.05±0.01 | 0.8 | 1.05 | 4.42±0.01 | 3.32 | 4.57 |

| 19 | B | CH3CH=CH-CO- | Ph-CH2- | Ph-CH2- | Ph-CH2- | 4.08 | 0.15±0.26 | 0.25 | −0.14 | 5.05±0.24 | 3.27 | 4.85 |

| 20 | B | CH3CH=CH-CO- | 1-Naphthyl- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.81 | −0.77±0.17 | −0.74 | −0.55 | 2.62±0.24 | 2.92 | 2.75 |

| 21 | B | Ph-CH=CH-CO- | Ph-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 3.04 | −0.72±0.18 | −0.57 | −0.97 | 4.12±0.21 | 3.32 | 3.37 |

| 22 | B | Ph-CO- | CH3CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.04f | −0.46±0.01 | −0.61 | −0.36 | 2.90±0.04 | 3.09 | 2.95 |

| 23 | B | Ph-CO- | Ph-CH2- | CH3CH2- | CH3CH2- | 3.11 | −0.44±0.02 | −0.73 | −0.48 | 2.31±0.37 | 3.03 | 2.48 |

| 24 | B | 4-CH3Ph-CO- | CH3CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.61 | −1.21±0.05 | −0.78 | −1.39 | 2.67±0.10 | 3.12 | 2.70 |

| 25 | B | 4-Cl-Ph-CO- | CH3CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.75 | −0.52±0.01 | −0.41 | −0.42 | 2.56±0.06 | 3.00 | 2.56 |

| 26 | B | 4-CH3O-Ph-CO- | CH3CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.20f | −0.22±0.02 | −0.60 | −0.28 | 2.80±0.04 | 3.09 | 2.87 |

| 27e | B | Ph-CO- | −CH3(CH2)2CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.99f | −1.16±0.07 | −0.74 | −1.21 | 2.31±0.06 | 3.04 | 1.95 |

| 28 | B | 4-CH3O-Ph-CO- | CH3(CH2)2CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.93 | −0.81±0.04 | −0.88 | −0.71 | 2.90±0.11 | 3.04 | 2.94 |

| 29 | B | 4-Cl-Ph-CO- | Ph-CH2CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.54f | −1.63±0.14 | −1.92 | −1.66 | 2.27±0.06 | 2.96 | 2.32 |

| 30 | B | 4-CH3Ph-CO- | Ph-CH2CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.61f | −0.72±0.07 | −0.66 | −0.72 | 2.67±0.25 | 3.10 | 2.49 |

| 31 | B | 4-F-Ph-CO- | Ph-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.50 | 0.61±0.13 | 0.63 | 0.65 | 3.42±0.02 | 3.21 | 3.36 |

| 32 | B | Ph-SO2- | Ph-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.14 | −0.39±0.04 | −0.42 | −0.36 | 2.63±0.20 | 3.15 | 2.34 |

| 33g | B | Ph-SO2- | Ph-CH2CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.31 | −0.36±0.05 | −0.06 | 15.67 | 2.15±0.08 | 3.14 | 12.19 |

| 34e | B | Ph-SO2- | CH3CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.02 | −0.16±0.03 | −0.60 | 0.17 | 2.73±0.08 | 2.93 | 2.53 |

| 35 | B | Ph-SO2- | Ph-CH2- | −CH2CH2CH2CH2- | 2.77 | 0.22±0.02 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 2.54±0.31 | 3.02 | 2.72 | |

| 36 | B | Ph-SO2- | (CH3)2CH-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.63 | 0.27±0.03 | 0.33 | 0.10 | 3.70±0.04 | 3.12 | 3.93 |

| 37g | B | 4-(Ph-O)-Ph-SO2- | Ph-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 3.53 | −0.80±0.03 | −0.24 | −0.99 | 2.25±0.17 | 3.02 | 3.15 |

| 38 | B | Ph-CO- | Ph-CH2- | CH3- | CH3- | 2.41 | −1.43±0.13 | −1.02 | −0.79 | 2.68±0.14 | 3.17 | 3.54 |

| 39 | B | Ph-CO- | 2-Naphthyl-CO- | CH3- | CH3- | 1.74 | 0.05±0.07 | 0.02 | −0.15 | 4.14±0.07 | 3.03 | 3.82 |

| 40g | C | CH3- | Ph-CH2O- | NA | NA | 1.56 | −0.45±0.03 | 0.29 | 1.28 | 1.85±0.21 | 3.04 | 4.50 |

| 41 | C | Ph-CH2CH2- | -OH | NA | NA | 1.30 | 0.10±0.24 | −0.15 | −0.34 | 2.27±0.09 | 2.82 | 2.32 |

| 42 | C | Ph-CH2O- | Cyclobutyl | NA | NA | 2.14 | −0.26±0.04 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 2.39±0.08 | 3.09 | 2.00 |

| 43 | C | Ph-CH2O- | Cyclopropyl | NA | NA | 1.78 | 1.17±0.04 | 0.66 | 1.05 | 4.32±0.04 | 3.12 | 4.32 |

| 44 | C | Ph-CH=CH- | Ph-CH2O- | NA | NA | 3.06 | −0.05±0.18 | −0.25 | 0.00 | 2.36±0.18 | 3.00 | 2.65 |

| 45 | C | CH3CH=CH- | Ph-CH2O- | NA | NA | 1.84f | −0.51±0.14 | −0.34 | −0.05 | 2.98±0.09 | 3.05 | 2.97 |

| 46e | C | 2-CH3Ph-CH=CH- | -OH | NA | NA | 1.63f | −0.49±0.05 | −0.20 | −0.16 | 2.28±0.14 | 2.81 | 2.53 |

| 47 | C | 4-CH3O-Ph-CH=CH- | -OH | NA | NA | 2.24f | −0.25±0.02 | −0.37 | −0.16 | 3.03±0.02 | 3.02 | 2.85 |

| 48 | C | Ph-CH=CH- | Ph(CH2)2O- | NA | NA | 3.01f | −0.59±0.05 | −0.22 | −0.28 | 2.26±0.10 | 3.02 | 2.54 |

| 49 | C | Ph-CH=CH- | Ph(CH2)3O-- | NA | NA | 2.55f | 0.96±0.02 | 0.57 | 0.89 | 2.67±0.12 | 3.10 | 2.56 |

| 50 | C | Ph-CH=CH- | Ph-CH2- | NA | NA | 3.70 | 0.19±0.02 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 2.48±0.18 | 2.99 | 2.60 |

| 51 | C | 2- CH3O-Ph-CH=CH- | Ph-CH2- | NA | NA | 3.65 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.12 | 0.35 | 3.25±0.09 | 2.96 | 3.27 |

| 52e | C | 2- CH3O-Ph-CH=CH- | Ph-CH=CH- | NA | NA | 3.60 | 0.98±0.05 | 0.39 | 0.77 | 2.53±0.21 | 3.10 | 2.90 |

| 53 | C | 2- CH3O-Ph-CH=CH- | CH3(CH2)6CH2- | NA | NA | 4.43 | 0.63±0.03 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 2.99±0.13 | 3.12 | 2.59 |

| 54 | C | 2-Cl-Ph-CH=CH- | 4-CH3O-Ph-CH2- | NA | NA | 4.10 | 0.79±0.01 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 3.11±0.10 | 3.21 | 2.93 |

| 55 | C | 4-Cl-Ph-CH2CH2- | Ph(CH2)3O- | NA | NA | 3.77 | −0.12±0.03 | 0.34 | −0.04 | 3.10±0.18 | 3.15 | 3.31 |

| 56g | C | 4-Ph-Ph-CH=CH- | 4-CH3O-Ph-CH2- | NA | NA | 4.75 | 0.54±0.01 | 0.27 | 1.67 | 2.79±2.42 | 3.11 | 11.73 |

| 57 | C | 3-(Ph-O)-Ph-CH=CH- | Ph-CH=CH-CH2-O- | NA | NA | 4.75 | 0.77±0.20 | 0.70 | 0.39 | 4.16±0.07 | 3.26 | 3.92 |

| 58 | C | 3-(Ph-O)-Ph-CH=CH- | CH3(CH2)6CH2- | NA | NA | 5.79 | 0.54±0.10 | 0.67 | 0.38 | 3.01±0.29 | 3.26 | 3.14 |

| 59 | C | 4-CH3O-Ph-(CH2)2- | 4-CH3O-Ph-CH2O- | NA | NA | 2.77 | 0.44±0.01 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 3.38±0.08 | 3.20 | 3.56 |

| 60g | C | see Figure 2 | Ph-CH2O- | NA | NA | 5.39 | 0.52±0.01 | 0.54 | 2.78 | 2.84±0.21 | 3.07 | 16.45 |

| 61 | C | see Figure 2 | −OH | NA | NA | 1.34 | −0.18±0.01 | −0.21 | 0.09 | 2.99±0.02 | 3.00 | 3.17 |

| 62 | NA | see Figure 2 | 2.49 | −0.58±0.05 | −0.35 | −0.85 | 2.79±0.39 | 2.83 | 2.56 | |||

| 63 | NA | see Figure 2 | 0.90 | −0.67±0.06 | −0.89 | −0.68 | 2.42±0.21 | 2.96 | 2.30 | |||

See Figure 1 for the skeleton structure.

The KD values are given in L/mol and the KS values have no units.

Calculated values for the training set, predicted values for the test set, using calibrated standard and multi-mode CoMFA models.

Not applicable.

A test set member.

Experimental value. Unmarked logP values were predicted using the ClogP estimates and correlations with experimental data.

A singular compound.

1-Octanol/Water Partitioning was measured for representative sets of 10–15 inhibitors from each series (Figure 1) and predicted by the ClogP softwarea for the rest of the compounds. In each series, some fragment contributions were not available, and the software used the calculated estimates. For this reason, the ClogP values were correlated with the logarithms of the experimental partition coefficients P, and the final logP estimates were made from the linear correlation equations. The linear correlations were characterized by the slope, intercept, and the squared correlation coefficient (r2) values, respectively, as follows: 0.688, 0.430, and 0.819 for 4,5-dihydro-oxazolines, 0.890, −1.490, and 0.799 for 3-pyrazolidinones, and 0.626, 1.065, and 0.941 for N-carbonyl-ureas.

Figure 1.

Skeletons of the three studied series of MMP inhibitors: 4,5-dihydro-oxazoline (A), 3-pyrazolidinone (B), and N-carbonyl-urea (C).

The measurement of the 1-octanol/buffer P values was carried out using the shake flask method with mutually saturated solvents. The compound solution in the borate buffer (3 mL, pH 7.4) was mixed with appropriate volumes of 1-octanol in 8-mL test tubes with screw-caps and PTFE septa to create a closed system, and incubated at 25°C. After 75 and 102 hrs, the amount of compound left in the buffer phase was determined spectrophotometrically. The 1-octanol/buffer partition coefficient was calculated from the mass balance. Along with each sample, the control containing only the solution of compound in the buffer was processed to account for possible evaporation of compound.

ECM Binding

The determination of binding constants of small molecules to ECM was described previously (7), so only a brief synopsis is provided here. Matrigel (500 µL, 5.76 mg/mL) was carefully loaded to the bottoms of vials and let solidify at 37°C. The borate buffer (2 mL; pH 7.4) was incubated with Matrigel for four hours to establish the protein dissolution equilibrium. The compounds in different concentrations in DMSO (20 µL) were added to the buffer and incubated with Matrigel for another two hours to achieve the binding equilibrium. The UV-Vis spectrophotometry (Shimadzu 1601) was used to measure the absorbances at several wavelengths in the separated supernatant. The association constants K to solidified Matrigel (subscript S) and dissolved Matrigel (subscript D – in the original paper (7) the subscript P was used) were determined using the fitting of the absorbance dependence on the ligand concentration cL according to the previously described (7) eqn 1:

| (1) |

Here, AL and A denote the absorbances with and without the ligand added; cR refers to the total concentration of the receptor (ECM); ε are the absorption coefficients of the chemical and ligand-receptor complexes (subscripts L and LR, respectively) multiplied by the light path, H is the Henry’s law constant, and VG and VA are the volumes of gas phase and aqueous phase, respectively. The magnitudes of εL, εLR, and H were determined in separate experiments.

Structures of Compounds for CoMFA Analyses

All compounds, except the hydroxamates 62 and GM6001 (63), fell into three categories, namely 4,5-dihydro-oxazolines 1–16, 3-pyrazolidinones 17-39, and N-carbonyl-ureas 40–61 (structures in Table 1), each containing a comparatively novel zinc binding group. Only the major species were considered in the analysis, which means that the carboxy groups in compounds 14–16 were treated as ionized. All molecules were sketched de novo in Sybyl modeling suiteb, and initially assigned Gasteiger and Hückel atomic charges (14,15). The geometries were optimized using the Tripos force field and the Powell’s method available in the Sybyl’s Maximin2 procedure, until the energy gradient was smaller than 0.001 kcal/(mol·Å).

Ligand Superposition

Compound 60 (Table 1) in the optimum conformation was chosen as the template because of its size and a high association constant toward solidified ECM surrogate. The optimum conformation was obtained by the Sybyl’s systematic conformational search of 16 rotatable bonds in 10-degree increments and subsequent energy minimization of the six lowest-energy conformers as described above. These energy minimizations converged on the same optimum conformation. The superposition was performed using the Flexible Superposition option in the FlexS (16) module of Sybyl with the minimum overlap volume set to 0.6. No overlapping fragments were selected due to diverse structures. Fifteen conformations/modes were generated for each compound. The conformation sets were further screened to keep only those with the energies within two folds of the minimum energy, and with the highest similarity scores to the template molecules. At most ten conformations (modes) were kept for each compound. In the following text dealing with multiple modes, a molecule means a binding mode. The top-scoring modes were used in the standard CoMFA procedure.

CoMFA Interaction Energy Calculations

The CoMFA studies (17) were performed with the QSAR module of Sybylb. The superimposed molecules were placed in a rectangular box with the dimensions of 26×26×28 Å, with the grid points set 2 Å apart in each direction. For each ligand in each binding mode, two types of interaction energy, steric and electrostatic, were calculated in each grid point with an sp3-carbon probe with the charge and the distance–dependent dielectric constant. The maximum allowable steric and electrostatic energy values were set to 30 kcal/mol. The electrostatic energy term was not calculated in the grid points where the steric energy term reached the limit value of 30 kcal/mol. The energies are organized in a table, where each row holds the data for one molecule. Each column represents the steric or electrostatic energy Xijk (the subscripts are explained below) of all molecules in one grid point. The dependent variables, bioactivity or affinity, are only available for a compound. Therefore, in the table for the multimode (MM) CoMFA procedure, only one row per compound, the row associated with the first mode, contains the dependent variable.

To define the application space of the CoMFA models, the energies are carefully checked for singularities. All columns, where only one or two energies are different from the rest, are excluded, along with the respective molecules. The number of different energies can be higher, if they all come from one compound. In that case, the singular compound is excluded from the analysis. The procedure was coded in the C language and incorporated using the SPL scripting language into the Sybyl softwareb, as described before (18). Singular compounds can provide additional information about the singular subspace. After the calibration of the model without the singular compound in the data set, the activity of the singular compound can be predicted. If the prediction agrees with the experimental value, there is a high probability that the regression coefficients for the singular grid points are close to zero and, consequently, the singular subspace can be regarded as water. On the other hand, a substantial difference between the predicted and experimental values means that the singular subspace is a part of the receptor that cannot be appropriately characterized by the used set of compounds.

Standard CoMFA Analysis

In the superposition, the top poses generated by the FlexS (16) module of Sybyl with the minimum overlap volume set to 0.6 were used. The partial least squares analysis was performed using the QSAR module of Sybyl, to generate a model composed of latent variables representing orthogonal linear combinations of original variables (17).

Multi-Mode Binding Equilibria

All 3D-QSAR methods assume that the averaged binding site of the receptor (ECM in this case) is roughly of the size of the studied ligands, and accommodates only one ligand molecule at a time, so the multiple binding modes are mutually exclusive. The reversible ligand-receptor complexes usually form quickly via noncovalent interactions, and can be characterized by the association constant. The conformer distribution in the receptor surrounding usually does not play a significant role in the binding affinity, since the conformations are easily inter-convertible. The differences in internal energies of free and bound molecules can be incorporated into the correlation eqn 4 below, but this option was not used in the current study. The probabilities of bound conformations (mode prevalencies) differ depending upon the free energy of binding. Some ligands will have only one binding mode with 100−% prevalence, whereas other ligands may exhibit multiple modes, with prevalencies adding up to 100%.

Schematically, the non-covalent 1:1 interactions of the ligand L with a single binding site of the receptor R, involving the possibility of m binding modes can be written as:

| (2) |

Individual equilibria are characterized by the partial association constants Kij. The experimentally observed association constant Ki for the binding of the i-th ligand to the receptor reflects the total concentration of the 1:1 ligand/receptor complexes (LRi)

| (3) |

The square brackets denote the equilibrium concentrations, which are assumed to be sufficiently low to approximate activities.

The simple eqn 3 is in agreement with published analyses of formally analogous situations: the statistical thermodynamic (19) and equilibrium (20,21) treatment of multi-mode binding in ligand/protein interactions, and kinetic analyses of a reversible uni-molecular reaction leading to different products (22) or isomers (23). A similar treatment was used in the Mining Minima approach to structure-based prediction of binding affinities (24).

Multiple Modes in CoMFA

In the CoMFA approach (17), the natural logarithm of the association constant for a ligand binding in the j-th binding mode (lnKij) is expressed as the weighed summation of the ligand/probe interaction energies Xijk. The substitution of this expression in eqn 3 results in the correlation equation for the MM-CoMFA analysis:

| (4) |

The k-summation runs through up to f×g independent variables, where f is the number of used energy types (steric, electrostatic, sometimes hydrophobic, polarizability, or hydrogen bonding energies) and g is the number of the used grid points. The independent variables, Xijk, are the energies of the interaction between the i-th ligand molecule in the j-th binding mode and a probe placed in the k-th grid point. The regression coefficients Ck characterize the significance of the field contributions in each grid point for overall binding. Notably, the coefficients Ck and C0 have the same values in each exponential, because they are associated with individual grid points and are independent of individual compounds and their binding modes. The extension of the CoMFA approach to the multi-mode binding thus only changes the form of the correlation equation, but does not increase the number of adjustable coefficients. The extension of eqn 4 for other factors contributing to free binding energy (internal conformational energy, conformational entropy, desolvation) is straightforward but was not applied in the present study, in order to keep the number of optimized coefficients in an acceptable proportion to the available data.

Nonlinear regression analysis combined with forward-selection and backward-elimination of variables in logarithmized eqn 4 optimizes the number and magnitudes of the coefficients Ck. Thanks to the selection of significant variables, the final number of the coefficients Ck is much lower than the initial pool of the f×g values. The set of optimized coefficients Ck defines the putative partial association constants Kij for each binding mode, which are equal to individual exponentials in eqn 4. The Kij values are further used to calculate the prevalences, i.e. the Boltzmann probabilities, of individual modes as the ratios of the particular Kij divided by the sum of all Kij’s as shown in the right-hand term of eqn 3. In other words, the prevalence of each mode is calculated as the ratio of the respective exponential in eqn 4 and the sum of all exponentials, with the optimized Ck values used in each exponential. The prevalences of individual modes are thus one of the outcomes of optimization and do not require any predefined input from the user. In fact, an a priori estimate of the mode prevalences is not feasible because the prevalences depend on the optimized coefficients Ck and on the way, how individual modes interact with the grid points associated with the optimized coefficients Ck. For this reason, the CoMFA procedure built-in in Sybyl, requiring the a priori user specification of the mode prevalences, cannot appropriately treat multi-mode binding situations.

Coefficient Optimization was performed by nonlinear regression analysis combined with forward-selection and backward-elimination of variables, using the following procedure that was coded in the C language, compiled, and integrated with Sybyl using the SPL script language. All available CoMFA columns, containing the interaction energies Xijk representing the independent variables, were first sorted according to the decreasing standard deviations, and used for the forward-selection of variables in this order. The analyses were performed in a similar way as we described previously (25), with the following differences: (i) the forward-selection/backward-elimination nonlinear regression analysis was integrated into the approach, in addition to the partial least squares analysis; (ii) the last two phases in the original approach, called Shaping and Detailing, were fused into a single phase, called Shaping; and (iii) the squared correlation coefficient (r2), adjusted for the number of compounds (n) and number of the used Ck coefficients (k) as r2adj = 1 - (1 - r2)(n - k)/(n - k - 1) was used for the comparison of individual fits. The procedure was written in the way that the analysis automatically switches to the partial least squares analysis with linearized eqn 4 (25), once the number of optimized coefficients exceeds a given fraction (default 80 %) of the number of compounds. This switch was not activated in the analysis of the current data set.

In the first phase, called Outlining, an exhaustive search for the best models with the user-specified number of variables/columns (STCOL = 3 to 7), having the highest standard deviations, was performed using the user-specified initial Ck estimates. The best 5% fits were subjected to the one-by-one deletion of the columns with the lowest contribution, until r2adj did not improve anymore. A user-specified fraction of the worst models (usually 95%) was discarded.

The second phase, Shaping, started with an addition of a new group of columns, having the user-specified number of columns, ADCOL = 3 to 6, to the best models from Outlining. If the fit improved, the columns were iteratively eliminated until r2adj stopped improving. The results were compared with the analysis before the addition of the ADCOL columns, and kept if the model improved. The process was repeated with the next group of ADCOL columns. This evolution of the model continued until r2adj stopped improving.

For the best models of one run, characterized by the specific values of STCOL, ADCOL, and starting values of the coefficients, the standard deviations (SD) of the coefficients were calculated. The columns with the highest SD/coefficient ratios were iteratively dropped from the regression equation, if r2 decreased by less than 5%.

Typically, several hundred runs were performed, many of them resulting in acceptable models. The best MM-CoMFA model was selected based on the statistical indices, number of included columns, and SD/coefficient ratios as the primary criteria, and the spatial distribution of the included grid points and used fields as secondary criteria. The whole process took 3–5 hours on a current SGI or Linux workstation, which is a much shorter time than in the original proof-of-the-concept study (25). The main reasons for the performance improvement were the use of the forward-selection/backward-elimination nonlinear regression analysis instead of the exclusive use of linearized partial least squares analysis, and coding the routines in the C language instead of the SPL script language.

Cross-Validations

Predictivity of all developed models was tested using a 6-member test set, as well as the leave-one-out (L1O) and leave-three-out (L3O) cross-validations. The L1O cross-validation was performed only for the standard CoMFA models. The compounds for the 6-member test set (5, 11, 27, 34, 46, and 52 in Table 1) were selected in a way ensuring that (i) their binding affinities were evenly distributed within the affinity ranges for both s-ECM and d-ECM, and (ii) all three series are represented. For the L3O procedure, the compounds were ordered according to the binding affinities and divided into three bins of about equal size. The 3-member test set was created by a random selection of one compound from each bin, while satisfying the condition that the selected compounds could not have the logK values closer than 10% of the overall span. The selection was repeated 10 times.

Results and Discussion

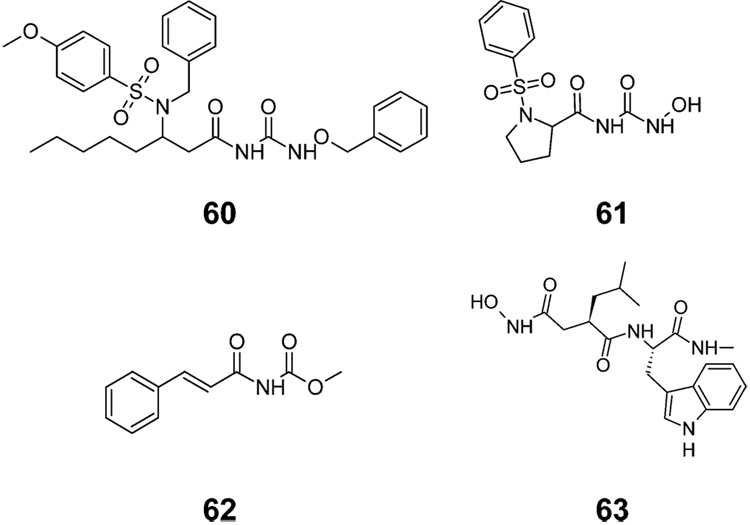

The studied compounds, mostly based on the 4,5-dihydro-oxazoline (A), 3-pyrazolidinone (B), and N-carbonyl-urea (C) skeletons (Figure 1), and some other structures (Figure 2) were tested for the ECM binding as a part of an in-house program aiming at the development of novel MMP inhibitors. Structures of the studied compounds are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2.

Some more complex structures of studied MMP inhibitors (Table 1). Compound 63 is widely used metalloproteinase inhibitor GM6001 (galardin, ilomastat).

Binding of MMP Inhibitors to ECM

Monitoring of the binding of chemicals to solidified ECM surrogate is complicated by the dissolution of the ECM proteins into the buffer. After establishing the protein dissolution equilibrium, the equilibrium absorbances at 6–12 wavelengths were measured for each of the 63 studied compounds in 3–5 concentrations. The association constants KS and KD to solidified (s-ECM) and dissolved (d-ECM) proteins, respectively, were determined by the fit of previously published equation (7) to the data sets, each of which contained at least 18 points. The absorption coefficients of individual species were determined at the pertinent wavelengths in separate titration experiments. The fits were excellent, as documented by the fact that the lowest value of the squared correlation coefficient was r2 = 0.925. The association constants resulting from the fits are summarized in Table 1.

The inhibitor affinities to the two forms of ECM proteins are not mutually dependent. For the bilogarithmic dependence of KD on KS, r2 = 0.264; slope = 0.544, and intercept = 2.990. Regretfully, this relation is too weak to be used for the prediction of KS from KD, because the sole use of the dissolved ECM surrogate would reduce the cost and time demand of the experiments. The correlations did not improve when the data set were broken down to individual series shown in Figure 1. These observations are in accordance with our previous results of the Western blot analysis, showing that there is a difference in the composition of the s-ECM and d-ECM proteins (7).

Binding vs. Lipophilicity

Intuitively, in a protein mixture such as ECM, several binding sites may be expected to exist, to which the compounds could bind weakly in multiple orientations and conformations, which are collectively called modes. This phenomenon is the hallmark of the nonspecific binding that has occasionally been correlated with lipophilicity (26–29), which was parametrized by the 1-octanol/water partition coefficient P, or with the pKa values for ionizable compounds (30). The dependencies on the acidity could not be examined in our data set, because the number of ionizable compounds was low. Only compounds 14–16 containing a carboxyl group, are fully ionized under the conditions of the experiments (pH = 7.4). Compounds 41, 46, 47, and 63 have the estimatedc pKa values of 8.85, 8.77, 8.68, and 9.16, respectively, and their ionization is less than 5% in our experiments. The dependencies of the affinities on lipophilicity, expressed as the logarithm of the measured or estimated 1-octanol/water partition coefficients (Table 1), are shown in individual panels of Figure 3. No significant overall correlations were apparent in our data set, although weak linear trends with some outliers can be spotted for binding of 4,5-dihydro-oxazolines to both s-ECM and d-ECM.

Figure 3.

The dependence of the binding affinities to solidified ECM (A) and dissolved ECM (B) on lipophilicity for 4,5-dihydro-oxazolines 1–16 (solid circles), 3-pyrazolidinones 17–39 (open circles), N-carbonyl-ureas 40–61 (crosses), and compounds 62 and 63 (stars). Structures are summarized in Table 1.

Lipophilicity describes conformation-averaged interactions (26–29). The failure of this approach for the ECM binding prompted us to look more closely at the nature of this event. Specifically, we were interested in the answers to such peculiar questions as what are the numbers of binding sites and modes. The presence of a single binding site was indicated above by the excellent fits of the binding isotherms, which were derived using the assumption of the 1:1 reversible binding (7). For a single binding site, the number of binding modes can be elucidated using one of the popular receptor site modeling methods, the Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), first in the standard, one-mode version, and then in our modification for multiple binding modes (MM CoMFA).

Ligand Superposition

In the absence of structural information of the binding site, the selection of the template for superposition was based on the standard criteria: (i) a high affinity toward solidified s-ECM surrogate because this form imitates the natural status of ECM; and (ii) size of the molecule. Several large molecules with high binding affinities were examined, with ligand 60 providing the best common template for the entire set of compounds. Ligand 60 was used as the template, in spite of the fact that it was later found to be a singular compound.

The FlexS (16) module in Sybyl does not require predefined information on the pharmacophore atoms shared by the template and superimposed ligands, and explicitly takes into account molecular flexibility of the superimposed ligand. The algorithm maximizes the overlap of the groups with similar binding abilities and, simultaneously, the overlap volume of the template and superimposed ligands. The modes generated by FlexS were screened to exclude those having high conformational energies and low similarity scores. At most 10 modes were kept for each molecule (Figure 4B). The similarity scores of the studied molecules to the template were in the range of 0.57–1.0.

Figure 4.

FlexS superposition of studied compounds using compound 60 as a template. A: the template 60 (yellow) and representatives of individual series - 6 (blue), 19 (red), and 57 (green); B: all compounds in all hypothetical binding modes; C: nonsingular compounds in nonsingular modes. All modes used in MM-CoMFA, as generated by FlexS, are included. Note the left and right bottom subregions, which are occupied by singular compounds in part B and are empty in part C. Structures are summarized in Table 1.

CoMFA Setup

The superimposed molecules were enclosed in a regular grid. The sp3- carbon probe with the charge was placed into each lattice point and the interaction energies between the probe and the superimposed ligands were calculated. The CoMFA analyses were performed according to described protocols.

To probe predictive ability of the resulting CoMFA models, the data set was split into two subsets, the training set and test set. The compounds for the test set were selected in a way ensuring that (i) their binding affinities were evenly distributed within the affinity ranges for both s-ECM and d-ECM, and (ii) all three series are represented. The test set consisted of compounds 5, 11, 27, 34, 46, and 52 (Table 1). In addition, the L1O cross-validation was performed for the standard CoMFA models and the L3O cross-validation with 10 selections of the test set was performed for both the standard and MM-CoMFA models.

Coverage of the 3D-Space by Superimposed Ligands

This aspect defines the application domain of 3D-QSAR models; yet, it is often neglected in published studies. The 3D-space around the superimposed ligands is defined by individual grid points. A grid point is deemed to be adequately characterized with respect to the given superposition of ligands, if the probe energies in that point, summarized in one column of the table, exhibit a distribution of the magnitudes for the given molecules. The opposite case is called a singularity and is defined as the situation when the energy values Xijk in a particular grid point are identical for all but one or two molecules. Typically, singularities arise in the situations when a subspace of the grid is occupied by: (i) only one or two molecules, while other molecules exhibit zero interaction energies in the pertinent grid points; or (ii) identical parts of all molecules, with the exception of one or two molecules exhibiting different interaction energies in the pertinent grid points. The affected subspace cannot be appropriately characterized by the CoMFA analysis. The regression coefficients are associated with the energies Xijk in the grid points and a correct optimization requires that there are several different energy values available for each grid point. The molecules causing the singularities can not be included in the correlation and need to be removed from the data set, along with the respective energies. The subspace must be marked as singular and the CoMFA model cannot be used for the prediction of activities of the compounds occupying the singular space (25). The singularities can be identified visually in the superposition of molecules or, more rigorously, by inspection of individual columns containing the energy sets. We used the latter approach. The singular sets differ for standard and multi-mode (MM) CoMFA analyses, because the ligand superpositions consisted of one mode vs. up to ten modes per ligand, respectively.

The energies in the grid points, where only one compound or mode contributed different energy values, were rigorously eliminated, along with the five compounds (33, 37, 40, 56, and 60; Table 1), causing the singularities. Interestingly, for compound 40 with no bulky group or atom extending into unoccupied space, the column causing singularity contains electrostatic energies. Ligand 60 was used as the template for superposition. Its identified singularity indicates that a portion of its structure was protruding into the subspace that was not shared with other compounds.

Standard CoMFA Analysis, using the top-scoring poses for all compounds in their major ionization state, was the first attempt to create a 3D-QSAR model. Compounds 33, 37, 40, 56, and 60 (Table 1 and Figure 4) had to be deleted because they caused singularities. The standard CoMFA models were built separately for s-ECM and d-ECM. The best models correlated the binding affinities with 334 and 485 energies, which were selected from the complete set using the SD filters of 4 and 2 kcal/mol, respectively. The weights for the steric/electrostatic energies were 0.528/0.472 and 0.475/0.525, respectively. The statistical indices are summarized in Table 2. The descriptive abilities of the CoMFA models were much better (r2 = 0.867) for s-ECM than for d-ECM (r2 = 0.194). The predictive abilities were tested in two ways, using the L1O and L3O cross-validations for the training set and the true predictions for the 6-member test set. For s-ECM, the statistical indices were r2L1O = 0.114, r2L3O = 0.101, and q2 = 0.678 for the test set. The results did not uniformly confirm an acceptable predictive ability of the model. For d-ECM, the results were even more disappointing: the predictive correlation coefficient for the test set of six compounds was only q2 = 0.123 and the weak predictivity was also indicated by the cross-validations in the training set (r2L1O = −0.159, r2L3O = 0.085). The unsatisfactory performance of the standard CoMFA model prompted us to examine the fit of the data with the MM-CoMFA model.

TABLE 2.

Statistical Indices for the Best CoMFA Models for Solidified and Dissolved ECM Surrogate

| Solidified ECM | Dissolved ECM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| standard | multi-mode | standard | multi-mode | |

| r2 | 0.867 | 0.877 | 0.194 | 0.882 |

| SSE | 2.921 | 2.711 | 23.04 | 4.515 |

| q2 | 0.678 | 0.865 | 0.123 | 0.735 |

| r2 L1O | 0.114 | NAb | −0.159 | NA |

| r2 L3Oc | 0.101 | 0.871 | 0.085 | 0.724 |

| # variablesa | 5/334 | 6/22 | 4/485 | 5/19 |

The number of principal components/number of considered energies for the standard CoMFA analyses and the number of selected steric/electrostatic energies for the MM-CoMFA models.

Not available.

Three-member test set, selection repeated ten times.

MM-CoMFA Analysis

The MM analysis started with up to ten top FlexS poses for each compound. The columns containing singularities were rigorously removed, along with the modes causing the singularities. Five compounds (33, 37, 40, 56, 60; Table 1) were eliminated, because all their modes were declared as singular. Further 38 modes of 16 compounds (2, 6, 12, 13, 15, 20, 21, 25, 29–32, 38, 39, 47, and 63; Table 1) were deleted as singular. Altogether, 412 modes were used for 58 compounds. The FlexS superpositions of all modes and the non-singular modes are shown in Figures 4B and 4C, respectively. An overview of used modes and singular modes for each compound is provided in Table 1S in the Supplementary Material.

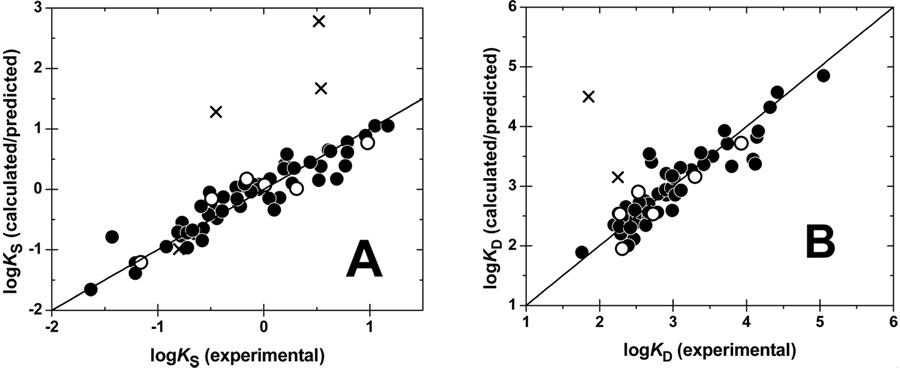

The coefficient optimization was performed by the forward-selection/backward-elimination nonlinear regression analysis. Statistical indices for the final selected MM-CoMFA models for s-ECM and d-ECM are summarized in Table 2, along with the results for the standard CoMFA models. The descriptive abilities improved significantly by the introduction of multi-mode binding: r2 = 0.877 and 0.882 for s-ECM and d-ECM, respectively. More importantly, the predictive abilities for the 6-member test set reached useful levels: q2 = 0.865 and 0.735, respectively. The predicted values for the test set and the calculated values for the training set are plotted against the experimental binding affinities in Figure 5. The L3O cross-validations, repeated 10 times, yielded the satisfactory values of r2L3O = 0.871 and 0.724, respectively.

Figure 5.

Description and prediction of experimental binding affinities by the MM-CoMFA models for s-ECM (A) and d-ECM (B) binding. Calculated affinities (full points) are for the training set. Predicted affinities (open points) are for compounds in the test set (5, 11, 27, 34, 46, and 52; Table 1) using the model developed for the training set. Predicted affinities for singular compounds, which protrude into an undefined region of the CoMFA map, are shown as crosses (33 for s-ECM and 33, 56, and 60 for d-ECM are out of shown ranges). Identity line is plotted as a visual aid.

Prevalences of Binding Modes for individual compounds are one of the results of the optimization. They are calculated as Kijk/ΣKijk, where Kijk corresponds to individual exponentials in the summation in eq 4. This is one of the important aspects of our multi-mode approach that does not require any subjective input regarding the preferences for individual binding modes. The modes were calculated for all compounds in the training and test sets, as well as for the singular compound 37 that showed a good predicted affinity (see below). All mode prevalences of MM-CoMFA analyses are summarized in Table 1S in the Supplementary Material. For s-ECM, total 12 of 59 compounds for which the modes were calculated demonstrated exclusively one binding mode (13, 18–20, 22, 29, 30, 31, 33, 36, 49, 63; Table 1), which contributes to at least 80% of binding affinity and there is no other mode accounting for more than a 10−% contribution. The remaining ligands exhibit two or more modes, each having at least 5−% mode prevalence. For the binding to d-ECM, there are 13 compounds (2, 5, 6, 13, 14, 16, 18–20, 29, 31, 33, 63), which exhibit one-mode binding according to the above criteria. These results illustrate why the standard, one-mode CoMFA procedure experienced problems with the current data sets, and the multi-mode approach performed better. The results of the one-mode CoMFA model using the most prevalent modes from the MM-CoMFA analysis (the results not shown) had unacceptable descriptive and predictive abilities. Consequently, there seems to be a need for the use of multiple modes in the CoMFA modeling of studied data.

CoMFA Maps of the Binding Site

Graphic representations of the best MM-CoMFA models for s-ECM and d-ECM are given in Figure 6. The showed regions indicate where the variations of steric or electrostatic properties in the structures of compounds in the training set led to the most significant changes in binding affinities. The CoMFA contour plots show all steric and electrostatic columns, which were selected in the best models for s-ECM and d-ECM. Polygons in green indicate the regions with positive coefficients (Ck > 0.1) associated with the van der Waals energies, where increased steric bulk leads to enhanced affinity. The yellow regions (Ck < −0.1) mark the opposite case. The regions where increased positive charge is favorable for stronger binding are indicated by blue (Ck > 2), while those where increased negative charge leads to increased affinity are shown as red polygons (Ck < −20). The spatial relations are illustrated using the series representatives 6, 19, and 57. The template 60 is also shown, in spite of the fact that as a singular compound it was excluded from the training set. Compounds 33, 37, 56, and 60 (Table 1) were larger than the superposition of the other molecules, and compound 40 elicited electrostatic interactions in a subregion, where no other compounds were interacting with the probe. The five compounds showed singularities in all modes. They were excluded from the training set and their affinities were later predicted from the calibrated models to provide further insight. The MM-CoMFA predictions for four singular compounds (33, 40, 56, and 60, Table 1) are uniformly much higher than the experimental affinities. Therefore, the developed model is deemed inconclusive for the respective singular regions (left bottom and right bottom regions in Figure 4), as defined by the compounds. However, the predicted binding affinities for compound 37 in both ECM forms were acceptable. The fact indicates that the singular region defined by 37 does not contain any points with significant regression coefficients and can be viewed as an aqueous region. The overpredicted binding affinities of compound 60, especially for d-ECM (Table 1) indicate that the n-pentyl chain, shown in the lower part of the superposition in Figure 6, which is located in the singular subregion, experiences a strong steric repulsion.

Figure 6.

The contour plots of steric and electrostatic fields for the best MM-CoMFA models for solidified ECM (A) and dissolved ECM (B) proteins. The series representatives 6, 19, and 57, and the template 60 are shown to illustrate spatial relations. Contours in green and yellow indicate the regions where the increase and decrease, respectively, in steric bulk lead to stronger binding. The blue and red electrostatic contours correspond to the regions where the increase in positive and negative charge, respectively, enhance the affinity.

Some similarities can be recognized by comparing the contour plots in Figure 6, despite slightly different viewing angles in the s-ECM and d-ECM models, which were chosen in order to provide unobstructed views of the regions. The number of electrostatic columns in both cases exceeds the number of steric columns and the coefficients associated with the electrostatic energies cover a wider range than those of the steric energies. These facts indicate that electrostatic interactions play more important roles in binding to both forms of ECM proteins.

The spatial distributions of the regions in the contour maps are, to some extent, similar for s-ECM and d-ECM, with electrostatic interactions concentrated in the left side and steric interactions appearing in the right-upper corner in the current view. For representative molecules of individual series (Figure 1), the left side of the current view includes the biphenyl ring of 6, one of the benzyl rings of 19, and the phenoxy group of 57. The majority of the coefficients of s-ECM and d-ECM in the same or neighboring points have the same signs. The differences in the signs, as well as the points with different coordinates, represent the differences in the s-ECM and d-ECM MM-CoMFA models, which reflect the different composition of both protein mixtures (7).

Earlier, we performed a similar 3D-QSAR study on binding data of 25 simple benzene derivatives to both s-ECM and d-ECM (18). In contrast to the MMP inhibitors studied here, the compounds ionize to significant degrees under the experimental conditions and multiple species had to be considered, along with multiple modes. The contour maps were also dominated by electrostatic interactions, although steric contributions were more significant than in the current maps. The distinct spatial separation of the electrostatic and steric regions is a common feature of the contours maps for the MMP inhibitors and the benzene derivatives, for both s-ECM and d-ECM.

Conclusions

This study was initiated by the desire to help in the prediction of the tissue distribution of MMP inhibitors, which appear to bind to a single binding site in ECM. The correlations between the association constants and lipophilicity, which are common for conformation-averaged binding, failed. This fact prompted us to deploy one of the frequently used 3D-QSAR techniques, CoMFA, which is capable of revealing the structural determinants of the binding behavior. Since the standard, one-mode CoMFA provided unsatisfactory results, we used our modification of the method for multi-mode binding. The resulting models exhibit satisfactory descriptive and predictive abilities, and provide structure-based interpretation of the binding affinities of MMP inhibitors to ECM. A singular region, where the MM-CoMFA models are inconclusive, is small. Therefore, the models can be used for prediction of binding affinities of the untested chemicals, which have structures and properties within the applicability domains. The domains are given by the nonsingular spatial overlap of steric and electrostatic fields of the tested compounds. The predictions for solidified ECM should be useful in the areas of pharmacokinetics, toxicology, and risk assessment.

Supplementary Material

Additional information is available from the online version of the article: Table 1S. Bound fractions (prevalences) of all modes and species.

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by the NIH NCRR grants 1 PP20 RR 15566 and 1 P20 RR 16471, as well as by the access to resources of the Computational Chemistry and Biology Network and the Center for High Performance Computing, both at the North Dakota State University.

Footnotes

ClogP, version 4.0 (1999), Claremont, CA, USA: Biobyte Corp.

Sybyl, version 7.3 (2007), St. Louis, MO, USA: Tripos Inc.

ACD/pKa DB, version 4.59 (2001), Toronto, ON, Canada: Advanced Chemistry Development.

References

- 1.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Validating matrix metalloproteinases as drug targets and anti-targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev. Cancer. 2006;6:227–239. doi: 10.1038/nrc1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Overall CM, Kleifeld O. Towards third generation matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Brit J Cancer. 2006;94:941–946. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernardo MM, Brown S, Li ZH, Fridman R, Mobashery S. Design, synthesis, and characterization of potent, slow-binding inhibitors that are selective for gelatinases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11201–11207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenblum G, Meroueh SO, Kleifeld O, Brown S, Singson SP, Fridman R, Mobashery S, Sagi I. Structural basis for potent slow binding inhibition of human matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) J Biol Chem. 2003;278:27009–27015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crul M, Beerepoot LV, Stokvis E, Vermaat JSP, Rosing H, Beijnen JH, Voest EE, Schellens JHM. Clinical pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and metabolism of the novel matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor ABT-518. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;50:473–478. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0515-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinman HK, McGarvey ML, Hassell JR, Star VL, Cannon FB, Laurie GW, Martin GR. Basement membrane complexes with biological activity. Biochemistry. 1986;25:312–318. doi: 10.1021/bi00350a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Lukacova V, Reindl K, Balaz S. Quantitative characterization of binding of small molecules to extracellular matrix. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2006;67:107–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook GR, Manivannan E, Underdahl T, Lukacova V, Zhang Y, Balaz S. Synthesis and evaluation of novel oxazoline MMP inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4935–4939. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin X. MS Thesis. Fargo, ND: North Dakota State University; 2006. Synthesis of novel n-heterocycles for MMP and HDAC inhibitors. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sibi MP, Stanely LM, Nie X, Venkatraman L, Liu M, Jasperse CP. The role of achiral pyrazolidinone templates in enantioselective diels-alder reactions: Scope, limitations, and conformational insights. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:395–405. doi: 10.1021/ja066425o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sibi MP, Manyem S, Palencia HJ. Fluxional additives: A second generation control in enantioselective catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13660–13661. doi: 10.1021/ja064472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manyem S. PhD thesis. Fargo: North Dakota State University; 2004. Forays in enantioselective catalysis. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun G. MS Thesis. Fargo: North Dakota State University; 2004. Preparation and biological evaluation of new matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitors. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gasteiger J, Marsili M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity: A rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:3219–3228. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streitwieser A., Jr . Molecular orbital theory for organic chemists. New York: Wiley; 1961. 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lemmen C, Lengauer T, Klebe G. FLEXS: A method for fast flexible ligand superposition. J Med Chem. 1998;41:4502–4520. doi: 10.1021/jm981037l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cramer RDI, Wold S. Comparative molecular field analysis (CoMFA) 5,307,287. U S Patent. 1994

- 18.Zhang Y, Lukacova V, Bartus V, Balaz S. Structural determinants of binding of aromates to extracellular matrix: A multi-species multi-mode CoMFA study. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006;20:11–19. doi: 10.1021/tx060188l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Szewczuk Z, Yue SY, Tsuda Y, Konishi Y, Purisima EO. Calculation of relative binding free energies and configurational entropies: A structural and thermodynamic analysis of the nature of non-polar binding of thrombin inhibitors based on hirudin 55-65. J Mol Biol. 1995;253:473–492. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balaz S, Hornak V, Haluska L. Receptor mapping with multiple binding modes: Binding site of PCB-degrading dioxygenase. Chemom Intell Lab Syst. 1994;24:185–191. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hornak V, Balaz S, Schaper KJ, Seydel JK. Multiple binding modes in 3D-QSAR: Microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. Quant Struct Act Rel. 1998;17:427–436. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jullien L, Proust A, LeMenn JC. How does the Gibbs free energy evolve in a system undergoing coupled competitive reactions? J Chem Educ. 1998;75:194–199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith WR, Missen RW. Chemical Reaction Equilibrium Analysis: Theory and Algorithms. New York, USA: Wiley; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Head MS, Given JA, Gilson MK. "Mining Minima": Direct computation of conformational free energy. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:1609–1618. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukacova V, Balaz S. Multimode ligand binding in receptor site modeling: Implementation in CoMFA. J Chem Inf Comp Sci. 2003;43:2093–2105. doi: 10.1021/ci034100a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansch C, Kiehs K, Lawrence GL. The role of substituents in the hydrophobic bonding of phenols by serum and mitochondrial proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:5770–5773. doi: 10.1021/ja00952a044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hersey A, Hyde RM, Livingstone DJ, Rahr E. A quantitative structure-activity relationship approach to the minimization of albumin binding. J Pharm Sci. 1991;80:333–337. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colmenarejo G, Alvarez-Pedraglio A, Lavandera JL. Cheminformatic models to predict binding affinities to human serum albumin. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4370–4378. doi: 10.1021/jm010960b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Valko K, Nunhuck S, Bevan C, Abraham MH, Reynolds DP. Fast gradient HPLC method to determine compounds binding to human serum albumin. Relationships with octanol/water and immobilized artificial membrane lipophilicity. J Pharm Sci. 2003;92:2236–2248. doi: 10.1002/jps.10494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ermondi G, Lorenti M, Caron G. Contribution of ionization and lipophilicity to drug binding to albumin: A preliminary step toward biodistribution prediction. J Med Chem. 2004;47:3949–3961. doi: 10.1021/jm040760a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional information is available from the online version of the article: Table 1S. Bound fractions (prevalences) of all modes and species.

Please note: Blackwell Publishing are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supplementary materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.