Abstract

In order to address the difficulty of assessing and managing multiple anxiety disorders in the primary care setting, this paper provides a simple, easy to learn, unified approach to the diagnosis, care management and pharmacotherapy of the four most common anxiety disorders (panic, generalized, and social anxiety disorders, and PTSD) in primary care. This evidence-based approach was developed for an ongoing NIMH-funded study designed to improve the delivery of evidence-based medication and psychotherapy treatment to primary care patients with these anxiety disorders. The paper presents a simple, validated method to screen for the four major disorders, which emphasizes identifying other medical or psychiatric comorbidities which can complicate treatment; an approach for initial education of the patient and discussion about treatment, including provision of some simple CBT skills, based on motivational interviewing/brief intervention approaches previously used for substance use disorders; a validated method for monitoring treatment outcome; an algorithmic approach for selection of initial medication treatment, selection of alternative or adjunctive treatments when the initial approach has not produced optimal results, and indications for mental health referral.

INTRODUCTION

In any given year, 18% of people will suffer from an anxiety disorder (1). The majority of these individuals receive treatment in general medical rather than specialty mental health settings(2). Anxiety disorders are as disabling as depressive disorders(3), and generate increased costs because the physical manifestations of anxiety often prompt expensive diagnostic procedures(4). In primary care, only a small minority of anxious patients receive treatment targeting their anxiety(5).

Studies suggest that the poor quality of care for anxiety in primary care may be related to difficulty recognizing and diagnosing anxiety disorders(6, 7), the increased time and enhanced skill needed to optimally engage such patients in care(8), and low perceived need for psychiatric treatment among patients(9). However, an even greater barrier to effective delivery of evidence-based care for anxiety is the non-unitary nature of anxiety disorders: instead of having one depressive disorder, major depression, to diagnose and treat, primary care physicians are faced with multiple anxiety disorders (e.g., panic (PD), generalized anxiety (GAD), social anxiety (SAD) and post traumatic stress (PTSD) disorders). This multiplicity of disorders makes it hard to have any unitary traction for public health education efforts: physicians must remember four different diagnostic and treatment approaches and, with the multitude of other problems they manage, this array of diagnostic algorithms and treatment options can become quite daunting.

This paper provides a unified approach to the diagnosis, care management and pharmacotherapy of primary care anxiety. We focus on the four most common anxiety disorders, all having an annual prevalence in primary care of between 5-10%, and cumulative rates for any of these between 10-15%. (10-14). We developed this simple, easy to learn, approach as part of an ongoing NIMH-funded study designed to improve the delivery of evidence-based medication and psychotherapy treatment to primary care patients with these anxiety disorders(15).

The paper presents a simple, validated method to screen for the four major disorders. The method emphasizes identifying other medical or psychiatric comorbidities which can complicate treatment; an approach for initial education of the patient and discussion about treatment based on motivational interviewing/brief intervention approaches previously used for substance use disorders(16); a validated method for monitoring treatment outcome; and an algorithmic approach for selection of initial medication treatment, and selection of alternative or adjunctive treatments when the initial approach has not produced optimal results. The entire procedure is outlined in Table 1 and for each step, a strength of recommendation is provided based on the recent SORT criteria recommended for family medicine journals(17).

TABLE 1.

ASSESSMENT AND TREATMENT APPROACH (with SORT level recommendations A-B-C)

| Screening and Assessment | |

| B | Four Anxiety Disorder Questions—ADD |

| A | Two Depression Questions |

| A | Alcohol Screen—AUDIT-C |

| C | Pain—One question |

| B | Suicide Evaluation—thoughts, plan, intent, reasons for living |

| B | Bipolar Disorder—MDS good specificity, poor sensitivity |

| Severity of Anxiety | |

| A | GAD-7—symptom severity |

| B | OASIS---functional impairment plus global symptoms |

| Treatment History | |

| C | Specify Response—little, moderate, a lot |

| Engaging the Patient-Brief Intervention | |

| B | Expectations for Outcome—0-10 |

| B | Expectation for Role in Outcome—0-10 |

| C | Use these and MI techniques |

| C | Help patient weight positives/negatives |

| Education and Skills | |

| C | Focus on Avoidance—Make list of avoided activities |

| C | Cognitive Restructuring to help with exposure |

| C | Breathing Techniques to help with exposure |

| C | Exposure (easiest to hardest) over 8-12 weeks |

| Initial Medication | |

| A | SSR/SNRII—start low and go slow, but go |

| B | Benzodiazepines—if > 4x week, keep taking for 12 weeks, then taper slowly |

| B | Benzodiazepines—may use as monotherapy in select cases |

| Treatment Resistant Anxiety | |

| C | Add another antidepressant or benzodiazepine |

| B | Consider in rare cases adding atypical neuroleptic |

| Medication Discontinuation | |

| C | After one year of therapy |

| C | Depending on comorbid psych and medical illness, avoidance, ongoing stress |

SCREENING AND ASSESSMENT

The assessment should determine: which anxiety disorders are present; what other conditions (e.g., depression, substance abuse and pain) accompany it, which treatments have been tried in the past, and what the patient expects of treatment. While performing a comprehensive diagnostic interview is not practical, asking a single question for each of the four common anxiety disorders, is simple, quick and sensitive(18). Asking two simple questions about mood and anhedonia for depression (a positive answer to either suggests major depression) may be as effective as using longer instruments(19, 20). The 3-item AUDIT-C is highly sensitive for problem alcohol use(21), with cutoff scores of 6 for men and 4 for women indicating problem use, and a single 0-10 analogue item asking about pain has been previously validated(22). This brief screening battery (Appendix 1) will suggest how many of the four anxiety disorders are present, and if major depression, problem alcohol use, or chronic pain are also issues. Patients screening positive for panic attacks might have them cued by social situations (social anxiety) or traumatic memories (PTSD) so a follow up question about whether they occur when the individual is alone and were unexpected can be useful in clarifying whether panic disorder is present.

All anxious patients, whether or not they also have depression, should be assessed for current thoughts of active self harm, passive thoughts of being “better off dead”, and a history of suicide attempts(23). Ask patients with suicidal thoughts whether they have a plan, access to means (i.e., firearms, stockpiled medications), or “reasons for living” that would stop them from acting (24). Caution them that substance abuse increases risk for suicide. Patients unable to both contract for safety and agree to a specific safety plan should be referred to mental health professionals for evaluation.

A patient who has failed to respond to several antidepressants and has a mixture of anxiety and depressive symptoms could be suffering from unrecognized bipolar illness(25). Such patients may also complain of overstimulation with antidepressants and may report brief positive responses to these agents that rapidly wane. This is a difficult diagnosis to make since it often requires multiple observations over a period of time to confirm retrospective reports of mood fluctuations. Patients endorsing less than 7 of 13 yes/no items on The Mood Disorder Questionnaire(26) are highly unlikely to have bipolar illness but scores greater than 7 detect less than half the cases(27). Hence, consultation with a psychiatrist is usually the most prudent option.

Anxiety severity can be measured with the GAD-7 scale, modeled after the now familiar PHQ-9 scale for depression(28, 29). A score above 10 suggests sufficient anxiety severity to consider treatment. Though this scale contains six GAD items and one panic disorder specific item, patients with other anxiety disorders also score high on this (see scale at http://www.healthandage.com/public/health-center/7/article/3308/gm=20!gid2=3129). For measurement of functional impairment due to anxiety, the five-item Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale(30, 31) is ideal. It measures, in addition to the frequency and intensity of anxiety, the degree of avoidance, and interference with work, and social function, and has a cut-off score of 8 for clinically significant anxiety (see Appendix 2). Once done at baseline, these scales should be used to monitor treatment outcome on subsequent visits, since multiple studies show that outcome improves with ongoing monitoring of treatment(32, 33).

Ask patients whether they’ve had medication or psychotherapy treatment in the past for their anxiety and how helpful it has been. Since there are no standardized scales to determine this, ask whether a treatment has helped a little, moderately, or a lot (i.e. returned them to their prior state). These questions correspond to frequently used measures in medication trials of “partial response” (25% improvement), “response” (50% improvement) and remission (75-100% improvement)(34). It is also important to know if treatment was stopped because of side-effects, and the nature of these. This is critical for anticipating problems with adherence. Finally, ask two simple questions about how much on a scale of 0-10 (none-definitely) the patient thinks treatment might work (“outcome expectancy”) and how confident they are they can help the treatment along (self-efficacy expectancy). Both these measures are powerful determinants of whether patients remain in treatment and whether they improve (35-38). If any problems with treatment adherence arise, these measures can be used productively in a follow-up counseling session with the physician or non-MD team members, employing the motivational interviewing approach outlined below.

MANAGING THE INITIAL VISIT: A BRIEF INTERVENTION

The goal of an initial visit is: to establish an empathic working relationship by using motivational interviewing techniques and style(16, 39-41); to give the patient feedback about their problem (what are the likely disorders and how does their anxiety severity fit in with population norms, using GAD-7 norms); to understand the patient’s motivation for treatment; and to review possible barriers to treatment, whether psychological, social, or logistical. Once the patient is interested in pursuing treatment, the physician, before prescribing medication, must help the patient see that making specific changes in behavior and thinking will speed improvement. This state of “self-activation” can frame the medication treatment, improving its efficacy and the patient’s adherence to it.

Avoiding an authoritarian and prescriptive approach with the anxious patient is essential, since such a style inadvertently encourages repeated reassurance seeking and discourages self-activation; instead the style is a blend of “supportive companion” and “knowledgeable consultant”. It is best to reflect how the anxiety has adversely affected them (the “negatives” of being anxious) and help them to overcome whatever barriers might interfere with their pursuit of treatment (e.g. logistical problems, concerns about taking medication, belief that treatment will not work). If the patient has low expectations that treatment will work (low “outcome expectancy”) or that they can do much to help it along (poor “self-efficacy expectancy”), ask what might improve these expectancies, and reinforce whatever strengths they have (e.g., perseverance). Avoid arguing (“roll” with any resistance the patient shows(41)), and instead help the patient develop an awareness of the discrepancy between where they “are” (all the “negatives” that go with anxiety) and where they would like to “be” (all the “positives” that go with being anxiety free, what they would be able to do etc). Some patients may not want to commit during an initial session, but laying the groundwork could make a repeat visit much easier. Available websites detail this interviewing approach (http://motivationalinterview.org/training/index.html#training), which has been shown to enhance adherence and participation for psychiatric and medical disorders. Though best known for use in substance abuse treatment, there is increasing interest in using these techniques with anxiety disorders, and evidence that it may increase efficacy and retention in cognitive behavioral treatment CBT(42, 43). Conceptualizing anxiety as a “behavior” (i.e. it ultimately can be under a patient’s control), rather than a “symptom,” makes it easier to apply this approach. Avoidance is the major driver of all anxiety, fuels failures of motivation and self-activation, and promotes maladaptive coping strategies. Patients need to be gently encouraged to face their fears by decreasing avoidant behavior and adopting a more “activated” life approach. By describing these behaviors as what successful people do to get over anxiety, greater self-activation will become more attractive to the patient.

PROVIDING EDUCATION AND SIMPLE SKILLS FOR ANXIETY

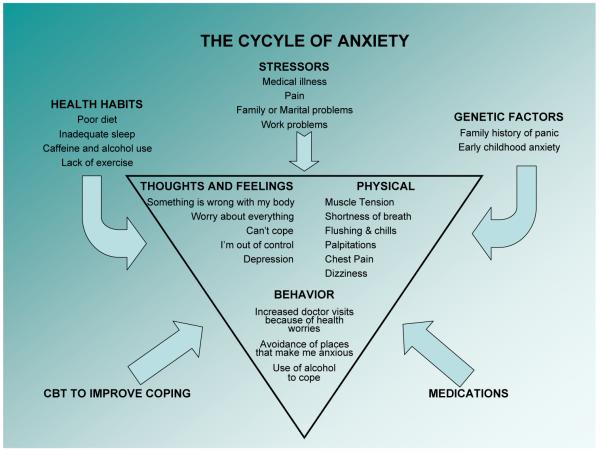

Use this part of the session to frame medication treatment. For patients ambivalent about treatment, try this by itself, and revisit the possibility of medication in a second visit. Educate patients about the “cycle of anxiety” (see Figure 1) which consists of a positive feedback cycle where anxious thoughts, physical symptoms and avoidance behavior feed on one another and aggravate anxiety. Use the figure to illustrate that genetic vulnerability, stressful experiences, and maladaptive thoughts and habits all contribute to anxiety and hence both medications and habit change can be therapeutic. Understanding that anxiety is a normal human response that the patient is having trouble turning off when it is not needed helps normalize the reaction(44).

Figure 1.

CBT approaches are used to interrupt this cycle and typically require at least 6-8 sessions. Though it has not been formally investigated, introducing these CBT principles into the primary care visit could be effective, since previous studies have found a single educational session can be beneficial(45). Here we provide some simple educational guidelines that address the behavioral, cognitive and physical manifestations of anxiety and are discussed in more detail in standard textbooks(44).

Behavioral avoidance can be directly counteracted by gradual exposure to feared objects or situations(46). Encourage the patient to make a list of their most feared situations from least to worst and suggest they gradually try to face thesesituations, starting with the easiest first (e.g. social situations for social anxiety disorder, reminders of trauma for posttraumatic stress disorder, situations from which it is difficult to escape or help is not readily available for panic disorder, and situations involving more self reliance, for example, for generalized anxiety disorder). If they take to this, it could well require 8-12 weeks to go from least to most. The most important point is for practice to be regular and daily, with little interruption.

During exposure, cognitive distortions are likely to arise and need to be questioned with an open scientific mind(47). The two most common errors made by anxious patients are overestimating the risk that something bad will happen (“jumping to conclusions” e.g. “if I feel lightheaded, I will faint”) or thinking that, if it does, the outcome will be terribly catastrophic (“blowing things out of proportion”, e.g., “I will panic while driving and will lose control of the car and crash”). Help patients understand that these thinking patterns are unrealistic (i.e., these beliefs have rarely, if ever, been confirmed in real life), so they can develop more evidence-based appraisals. Some patients may be able to apply these simple principles themselves, though many others are likely to need more coaching, which could be provided in brief follow-up sessions, or through referral to a CBT expert.

Finally, physical symptoms of anxiety can be counteracted by relaxation techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation(48) and diaphragmatic breathing (put one hand on your belly, the other on your chest, make only the belly hand move when you breathe—practice several times a day)(49). Regular exercise also contributes to counteracting physical symptoms of anxiety(50, 51), as will avoidance of caffeine and alcohol, and poor sleep hygiene, which can often aggravate anxiety. Addressing these lifestyle factors can often have a clear-cut effect. Finally, emphasize to patients that they do not need to totally eliminate anxious symptoms. Instead, they should develop an attitude that symptoms can be managed and even tolerated while they do something they were not able to do previously (e.g. drive on the freeway). This helps establish realistic expectations about treatment.

MEDICATION APPROACHES FOR ANXIETY

Selecting the Agent and Adjusting the Dose

There are more similarities than differences in indicated medication treatments for the four most common anxiety disorders (PD, GAD, SAD and PTSD). While developed for depression, anti-depressants are also anxiolytic and FDA approved for these four anxiety disorders. Antidepressants are generally first line pharmacotherapy, particularly because comorbid depression is common in such patients, and because there is no abuse liability, as there is with benzodiazepines. If a patient has never received medication treatment before, an SSRI is recommended. SSRIs and the SNRI venlafaxine XR are all equally efficacious for all four disorders(52, 53). Data on the other SNRI duloxetine support efficacy in GAD but other disorders have not been studied. When choosing between them, the clinician and patient should focus on: cost and generic availability; the risk of breakthrough symptoms when a dose is inadvertently missed (paroxetine and venlafaxine have the shortest half lives and produce more immediate withdrawal symptoms when a dose is missed, while fluoxetine is at the other end with a very long half life and no risk of breakthrough symptoms); ease of titration (venlafaxine requires more titration steps than SSRIs); the potential for CYP450-mediated interactions with other medications (citalopram, escitalopram and venlafaxine have no CYP450 effects); and the risk of adverse effects (which are highly idiosyncratic). For this last issue, there is little definitive data because there are few comparative studies among SSRIs not biased by industry funding; the best study failed to show any differences in depressed patients(54), and a smaller study showed similar negative findings in anxious depression(55). Furthermore, some adverse effects may be different in depressed as opposed to anxious patients. All medications with an SSRI effect, including venlafaxine, produce sexual dysfunction. These considerations are outlined in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

SSRI ANTIDEPRESSANT OPTIONS

| MEDICATION | ANXIOLYTIC EFFICACY* |

ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|---|

| fluoxetine | Panic**, PTSD* | Generic available; Long 1/2 life (No withdrawal) |

Most stimulating; Longer 1/2 life |

| paroxetine | Panic**, GAD**, SAD**, PTSD** |

Generic available; Most extensively studied across these anxiety disorders; Least stimulating; No P450 3A4 effects |

Most sedating; Shorter ½ life and worse withdrawal |

| sertraline | Panic**, GAD*, SAD**, PTSD** |

Well-studied across these 4 anxiety disorders; Least P4502D6 effects; Minimal P4503A4 effects; Intermediate 1/2 life (Less withdrawal) |

Most diarrhea |

| citalopram | Panic* | Generic available; No P450 effects |

|

| escitalopram | Panic*, GAD**, SAD* | No P450 effects | |

| venlafaxine ER | Panic**, GAD**, SAD**, PTSD |

No P450 effects | Short ½ life; Withdrawal with missed dose or sudden discontinuation; Increased BP at >225 mg |

RCTs but no FDA-approved indication

FDA-approved indication as of January 2006

If there is a prior history of response to a different antidepressant, that antidepressant can be tried first. If there is a prior response to a benzodiazepine, an SSRI is still preferred. If there has been prior non-response to an SSRI, a different SSRI is recommended. Determine whether prior medication trials were conducted for an adequate duration (minimal 8 to 12 weeks) at an adequate dosage (whichever is reached first: the maximum suggested by the manufacturer, or the maximally tolerated), since in this setting prescription of appropriate type of medication is common, but doses are often too low(56). Always start with a low dose, particularly with panic disorder, but titrate up to average doses in 2-3 weeks as tolerated, and then to higher maximally tolerated doses by 6 weeks, unless substantial response has occurred. Use the GAD-7 or OASIS to monitor treatment, and characterize trials as producing partial response, response or remission. Consider using the scale for a week before initiating treatment, since patients’ tendency to attribute fluctuations in their anxiety to new medications will be discouraged by observing that natural fluctuations occur without being on medication.

What to Do About Benzodiazepines

Although co-administratioin of a benzodiazepine with an SSRI has been shown to speed response (57), this strategy is not recommended routinely. However, if patients are taking regular daily doses of a benzodiazepine (more than 4 times a week), it is unwise to immediately taper medication. Start an antidepressant first, titrate up to a maximal dose, and wait 12 weeks in order to maximize the chance of response. Then, reduce the benzodiazepine dose gradually, by 10-20% at 2-4 week intervals(58-60). Substituting a long acting benzodiazepine like clonazepam for short half life medications may be useful in some patients. Patients will be more comfortable with an initial strategy of benzodiazepine dose reduction, rather than benzodiazepine elimination. Once their anxiety improves, and they see they can do well on reduced doses combined with an antidepressant, discontinuation is often much easier. However, adding a benzodiazepine to antidepressants is a commonly used, effective, but not formally studied strategy for treatment-resistant anxiety(61, 62) (see below), as some patients may require a benzodiazepine for therapeutic effect. Accordingly, elimination of the benzodiazepine may not be therapeutically appropriate in some cases.

If a patient has a history of non-response to several antidepressants, intolerance due to overstimulation, other adverse effects, or concomitant medical illness or its treatment, the evidence base suggests that a benzodiazepine may be a reasonable agent to use as monotherapy provided that: there is no current substance use problem, any prior history of substance use is remote or has been addressed in treatment, there is no current depression requiring treatment, and the anxiety syndrome is panic disorder or social anxiety disorder(52). Benzodiazepines have not been demonstrated to work for PTSD, though they are sometimes used to reduce hyperarousal, often in combination with other pharmacological therapies(63). GAD as a stand alone diagnosis is difficult to make and may be confused with adult ADHD, personality disorder, occult unrecognized substance use disorder, or atypical bipolar illness with “mixed” state features. Hence, use of benzodiazepines targeted exclusively toward a GAD diagnosis is fraught with risks and requires added psychiatric consultation. If benzodiazepines are to be used, alprazolam 2.0-6.0 mg daily (usually TID or QID) and lorazepam 4.0-12.0 mg daily (usually BID or TID) may be problematic because the multiple dosing required continually links pill taking with the need to cope with anxiety throughout the day. Instead, use high potency medications (clonazepam 1-4 mg daily, usually BID) because the long half life will reduce risk of withdrawal symptoms with missed doses. Clonazepam’s slower rate of absorption, also reduces abuse liability and it can be administered once daily, though BID use is more common. The cognitive effects of high potency benzodiazepines may be problematic(64). While elderly patients are clearly more vulnerable to this effect, the performance of younger individuals with jobs requiring complex information processing and multi-taking also may be subtly compromised. A promising alternative to benzodiazepines, with less risk of abuse, or physical dependence in studies so far, are GABA-ergic agents like gabapentin, shown to be effective for panic disorder(65) and social anxiety disorder(66) in small controlled trials, and pregabalin, now marketed for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia, and shown effective in controlled clinical trials for SAD and GAD(67). These agents are not FDA-approved for use in anxiety, but could be useful for treatment-resistant patients in whom benzodiazepines are contraindicated.

Anxiety Resistant to First-Line Treatment

Before exploring additional therapies, failure to respond should always prompt reconsideration of diagnosis. Are there other syndromes (e.g. atypical bipolar disorder) that may account for this? Are there new life stressors or changes? Occult substance abuse may be playing a role. Patients may not reliably report their substance abuse early on, but may be more willing to describe their usage patterns once they are in treatment. It is therefore worthwhile asking about substance use not only at the start of treatment, but again later in treatment, especially if the patient is not responding as well as expected. Finally, functional status should be reassessed, especially avoidance, which may continue to persist despite symptom improvement, and require a more behavioral approach.

In the absence of controlled data to guide strategies for treatment resistant anxiety, results on various strategies for treatment resistant depression from the recent STAR-D study(33, 68-71) can be used as a guideline for antidepressant selection (though it has no data on benzodiazepines). For patients showing at least partial response (25% improvement in symptoms and/or function) with a maximum dose of an antidepressant, continue this agent while adding another medication. Adding a benzodiazepine is one option especially useful when there is a prominence of residual anxious symptoms without residual depressive symptoms(62). Alternatively, adding another antidepressant is useful and could include combining an SSRI with venlafaxine, or combining either agent with mirtazapine or a tricyclic antidepressant. The small risk of serotonin syndrome when these serotonin-active agents are combined needs to be considered. If depression is more prominent in the clinical picture, the addition of bupropion could be considered. Third-line medication augmentation could include addition of an atypical antipsychotic, a strategy that is supported by some small randomized trials(72-74). While increased efficacy is likely with some of these atypical antipsychotics, the magnitude of additional benefit is sometimes small to modest at best and, the risk of adverse effects (e.g., weight gain, diabetes (typically a type II, and rarely type I) and dyslipidemia) requires careful consideration of the risk benefit ratio in the individual patient.

Medication Discontinuation

Use of medication may serve in many patients as a “safety” signal that reinforces their feeling that they cannot cope on their own or gradually master anxiety-provoking situations by exposing themselves and learning through actual experience that nothing terrible will happen. These “reverse CBT” effects may be particularly prominent with rapidly-acting and tranquilizing benzodiazepines, which immediately reinforce the user with prompt reduction in anxiety, undercutting their own abilities to “toughen up” in the face of stress. In many patients considering discontinuation of medication after a period of remission, these issues can become prominent; patients who are more confident they can master stress on their own and weather anxious feelings, are more likely to do well with medication discontinuation.

Decisions about discontinuing medication should be based on the probability of relapse once medication is stopped. This is greatest for patients with multiple disorders, who have some remaining residual symptoms, and/or who have ongoing medical or psychosocial stress. Patients with all these factors are likely to do poorly; patients with none of these are likely to do well. Most patients will fall somewhere in between and their status with respect to these factors should be used to make individual decisions

Acknowledgments

Funding: This manuscript was supported by grants MH057858 (PRB), MH070022 (GS), MH058915 (MGC), and MH057835 (MBS) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD.

APPENDIX 1

ANXIETY: “Have you…”

Had a spell or attack where all of a sudden you felt frightened, anxious, or uneasy? (Panic)

Been bothered by nerves or feeling anxious or on edge for 6 months? (GAD)

Had a problem being anxious or uncomfortable around people? (SAD)

Had recurrent dreams or nightmares of trauma or avoidance of trauma reminders? (PTSD)

DEPRESSION: “Over the past two weeks, have you

felt down depressed or hopeless felt little interest or pleasure in doing things

ALCOHOL PROBLEMS

| “In the past year…” | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1) How often did you have a drink containing alcohol? |

Never | Monthly or less |

2-4 times a month |

2-3 times a week |

4 or more times a week |

|

| 2) How many drinks containing alcohol did you have on a typical day when you were drinking? |

1 or 2 | 3 or 4 | 5 or 6 | 7 to 9 | 10 or more |

N/A (If #1 = 0) |

| 3) How often did you have six or more (4 or more for women) drinks on one occasion? |

Never | Less than monthly |

Monthly | Weekly | Daily or almost daily |

N/A (If #1 = 0) |

PAIN

On a scale of 0-10 where 0 means no pain and 10 means the worst pain imaginable, how would you rate your pain?

APPENDIX 2

Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS)

- In the past week, how often have you felt anxious?

- 0 = No anxiety in the past week.

- 1 = Infrequent anxiety. Felt anxious a few times.

- 2 = Occasional anxiety. Felt anxious as much of the time as not. It was hard to relax.

- 3 = Frequent anxiety. Felt anxious most of the time. It was very difficult to relax.

- 4 = Constant anxiety. Felt anxious all of the time and never really relaxed.

- In the past week, when you have felt anxious, how intense or severe was your anxiety?

- 0 = Little or None: Anxiety was absent or barely noticeable.

- 1 = Mild: Anxiety was at a low level. It was possible to relax when I tried. Physical symptoms were only slightly uncomfortable.

- 2 = Moderate: Anxiety was distressing at times. It was hard to relax or concentrate, but I could do it if I tried. Physical symptoms were uncomfortable.

- 3 = Severe: Anxiety was intense much of the time. It was very difficult to relax or focus on anything else. Physical symptoms were extremely uncomfortable.

- 4 = Extreme: Anxiety was overwhelming. It was impossible to relax at all. Physical symptoms were unbearable.

- In the past week, how often did you avoid situations, places, objects, or activities because of anxiety or fear?

- 0 = None: I do not avoid places, situations, activities, or things because of fear.

- 1 = Infrequent: I avoid something once in a while, but will usually face the situation or confront the object. My lifestyle is not affected.

- 2 = Occasional: I have some fear of certain situations, places, or objects, but it is still manageable. My lifestyle has only changed in minor ways. I always or almost always avoid the things I fear when I’m alone, but can handle them if someone comes with me.

- 3 = Frequent: I have considerable fear and really try to avoid the things that frighten me. I have made significant changes in my life style to avoid the object, situation, activity, or place.

- 4 = All the Time: Avoiding objects, situations, activities, or places has taken over my life. My lifestyle has been extensively affected and I no longer do things that I used to enjoy.

- In the past week, how much did your anxiety interfere with your ability to do the things you needed to do at work, at school, or at home?

- 0 = None: No interference at work/home/school from anxiety.

- 1 = Mild: My anxiety has caused some interference at work/home/school. Things are more difficult, but everything that needs to be done is still getting done.

- 2 = Moderate: My anxiety definitely interferes with tasks. Most things are still getting done, but few things are being done as well as in the past.

- 3 = Severe: My anxiety has really changed my ability to get things done. Some tasks are still being done, but many things are not. My performance has definitely suffered.

- 4 = Extreme: My anxiety has become incapacitating. I am unable to complete tasks and have had to leave school, have quit or been fired from my job, or have been unable to complete tasks at home and have faced consequences like bill collectors, eviction, etc.

- In the past week, how much has anxiety interfered with your social life and relationships?

- 0 = None: My anxiety doesn’t affect my relationships.

- 1 = Mild: My anxiety slightly interferes with my relationships. Some of my friendships and other relationships have suffered, but, overall, my social life is still fulfilling.

- 2 = Moderate: I have experienced some interference with my social life, but I still have a few close relationships. I don’t spend as much time with others as in the past, but I still socialize sometimes.

- 3 = Severe: My friendships and other relationships have suffered a lot because of anxiety. I do not enjoy social activities. I socialize very little.

- 4 = Extreme: My anxiety has completely disrupted my social activities. All of my relationships have suffered or ended. My family life is extremely strained.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Dr. Roy-Byrne reports he was a consultant for Jazz Pharmaceuticals and Solvay Pharmaceuticals, and speaker honoraria for Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceuticals and Forest Laboratories. Dr. Bystritsky reports he was a consultant, speaker honoraria, and on the speaker’s bureau for Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Stein reports receiving research support from Eli Lilly and Company and GlaxoSmithKline, and was a consultant for AstraZeneca, Avera Pharmaceuticals, BrainCells Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, EPI-Q Inc., Forest Laboratories, Hoffmann-La Roche Pharmaceuticals, Integral Health Decisions Inc., Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Johnson & Johnson, Mindsite, Sanofi-Aventis, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Virtual Reality Medical Center. The remaining authors have no interests to disclose. None of the entities mentioned above sponsored or had any role or influence in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, et al. Functional impact and health utility of anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Med Care. 2005;43:1164–70. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000185750.18119.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katon W, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost offset of a collaborative care intervention for primary care patients with panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:1098–1104. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein MB, Sherbourne CD, Craske MG, et al. Quality of care for primary care patients with anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2230–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nisenson LG, Pepper CM, Schwenk TL, et al. The nature and prevalence of anxiety disorders in primary care. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1998;20:21–28. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(97)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ormel J, Koeter MW, van den Brink W, et al. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320024004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kroenke K, Jackson JL, Chamberlin J. Depressive and anxiety disorders in patients presenting with physical complaints: clinical predictors and outcome. Am J Med. 1997;103:339–347. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:261–9. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leon AC, Olfson M, Broadhead WE, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in primary care: implications for screening. Arch Fam Med. 1995;4:857–61. doi: 10.1001/archfami.4.10.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherbourne CD, Jackson CA, Meredith LS, et al. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety diorders in primary care outpatients. Archives of Family Medicine. 1996;5:27–34. doi: 10.1001/archfami.5.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;28:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan G, Craske MG, Sherbourne C, et al. Design of the Coordinated Anxiety Learning and Management (CALM) study: innovations in collaborative care for anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17:59–67. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.17.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Means-Christensen A, CD S, Roy-Byrne P, et al. Using five questions to screen for five common mental disorders in primary care: the anxiety and depression detector (ADD) General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. PSTF Screening for Depression.

- 20.Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, et al. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:439–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, et al. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:1208–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butt Z, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, et al. Use of a single-item screening tool to detect clinically significant fatigue, pain, distress, and anorexia in ambulatory cancer practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linehan MM, Goodstein JL, Nielsen SL, et al. Reasons for staying alive when you are thinking of killing yourself: the reasons for living inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:276–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1873–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phelps JR, Ghaemi SN. Improving the diagnosis of bipolar disorder: predictive value of screening tests. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;46:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell-Sills L, Norman SB, Craske MG, et al. Validation of a brief measure of anxiety-related severity and impairment: The Overall Anxiety Severity and Impairment Scale (OASIS) J Affect Disord. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Norman SB, Cissell SH, Means-Christensen AJ, et al. Development and validation of an Overall Anxiety Severity And Impairment Scale (OASIS) Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:245–9. doi: 10.1002/da.20182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al. Rethinking practitioner roles in chronic illness: the specialist, primary care physician, and the practice nurse. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:138–44. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nierenberg AA, DeCecco LM. Definitions of antidepressant treatment response, remission, nonresponse, partial response, and other relevant outcomes: a focus on treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 16):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams SL, Kinney PJ, Falbo J. Generalization of therapeutic changes in agoraphobia: the role of perceived self-efficacy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:436–42. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.3.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Safren SA, Heimberg RG, Juster HR. Clients’ expectancies and their relationship to pretreatment symptomatology and outcome of cognitive-behavioral group treatment for social phobia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:694–8. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grilo CM, Money R, Barlow DH, et al. Pretreatment patient factors predicting attrition from a multicenter randomized controlled treatment study for panic disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:323–32. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shear MK. Psychotherapeutic issues in long-term treatment of anxiety disorder patients. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1995;18:885–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996;21:835–42. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller WR, Baca C, Compton WM, et al. Addressing substance abuse in health care settings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:292–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Westra H, Dozois D. Preparing clients for cognitive behavior theray: a randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing for anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and research. 2006;30:481–498. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slagla D, Gray M. The utility of motivational interviewing as an adjunct to exposure therapy i the treatment of anxiety disorders. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2007;38:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barlow DH. New York, NY. Guilford Press; 2002. Anxiety and its Disorders: the nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swinson RP, Soulios C, Cox BJ, et al. Brief treatment of emergency room patients with panic attacks. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:944–6. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.7.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Craske MG. Anxiety disorders: psychological approaches to theory and treatment. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck A, emery G, Greenberg R. Anxiety disordersr and phobias: a cognitive perspective. Basic Books; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ost L, Westling B. Applied relaxation vs cognitive therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1995;33:145–148. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)e0026-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garssen B, Ruiter Cd, Dyck Rv, et al. Will hyperventilation syndrome survive: A responder to Ley. Clinical Psychology Review. 1993;13:683–690. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Broman-Fulks JJ, Storey KM. Evaluation of a brief aerobic exercise intervention for high anxiety sensitivity. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2008;21:117–28. doi: 10.1080/10615800701762675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strohle A, Feller C, Onken M, et al. The acute antipanic activity of aerobic exercise. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2376–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roy-Byrne PP, Cowley D. In: Pharamcologic treatments for panic disorder, generalized anxiety disordere, specific phobia and social anxiety disorders in A guide to treatments that work. 3rd Edition Nathan P, Gorman J, editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein MB. In: Anxiety disorders: somatic treatment in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. HI K, Bj S, editors. Williams and Wilkins; Baltimore, Maryland: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kroenke K, West SL, Swindle R, et al. Similar effectiveness of paroxetine, fluoxetine, and sertraline in primary care: a randomized trial. Jama. 2001;286:2947–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Hoog SL, et al. Fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major depression: tolerability and efficacy in anxious depression. J Affect Disord. 2000;59:119–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00131-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Dugdale DC, et al. Undertreatment of panic disorder in primary care: role of patient and physician characteristics. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:443–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rickels K, Schweizer E, Case WG, et al. Long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines. I. Effects of abrupt discontinuation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1990;47:899–907. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810220015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rickels K, Schweizer E, Csanalosi I, et al. Long-term treatment of anxiety and risk of withdrawal. Prospective comparison of clorazepate and buspirone. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:444–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800290060008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rickels K, Schweizer E, Weiss S, et al. Maintenance drug treatment for panic disorder. II. Short- and long-term outcome after drug taper. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:61–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820130067010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pollack MH, Otto MW, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. Novel treatment approaches for refractory anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:467–76. doi: 10.1002/da.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bystritsky A. Treatment-resistant anxiety disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:805–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mellman TA, Clark RE, Peacock WJ. Prescribing patterns for patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1618–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.12.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stewart SA. The effects of benzodiazepines on cognition. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(Suppl 2):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pande AC, Pollack MH, Crockatt J, et al. Placebo-controlled study of gabapentin treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:467–71. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200008000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pande AC, Davidson JR, Jefferson JW, et al. Treatment of social phobia with gabapentin: a placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:341–8. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199908000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Feltner DE, Crockatt JG, Dubovsky SJ, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose, multicenter study of pregabalin in patients with generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:240–9. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000084032.22282.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fava M, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. A comparison of mirtazapine and nortriptyline following two consecutive failed medication treatments for depressed outpatients: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1161–72. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1531–41. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1531. quiz 1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rush AJ. STAR*D: what have we learned? Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:201–4. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905–17. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stein MB, Kline NA, Matloff JL. Adjunctive olanzapine for SSRI-resistant combat-related PTSD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1777–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pollack MH, Simon NM, Zalta AK, et al. Olanzapine augmentation of fluoxetine for refractory generalized anxiety disorder: a placebo controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:211–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rothbaum BO, Killeen TK, Davidson JR, et al. Placebo-Controlled Trial of Risperidone Augmentation for Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor-Resistant Civilian Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:e1–e6. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]