Abstract

Molecular dynamics simulations with coarse-grained and/or simplified Hamiltonians are an effective means of capturing the functionally important long-time and large-length scale motions of proteins and RNAs. Structure-based Hamiltonians, simplified models developed from the energy landscape theory of protein folding, have become a standard tool for investigating biomolecular dynamics. SMOG@ctbp is an effort to simplify the use of structure-based models. The purpose of the web server is two fold. First, the web tool simplifies the process of implementing a well-characterized structure-based model on a state-of-the-art, open source, molecular dynamics package, GROMACS. Second, the tutorial-like format helps speed the learning curve of those unfamiliar with molecular dynamics. A web tool user is able to upload any multi-chain biomolecular system consisting of standard RNA, DNA and amino acids in PDB format and receive as output all files necessary to implement the model in GROMACS. Both Cα and all-atom versions of the model are available. SMOG@ctbp resides at http://smog.ucsd.edu.

INTRODUCTION

It is well established that the dynamic properties of biomolecules are important for their biological function. Conformational rearrangements are necessary for a variety of protein functions including catalysis and regulation. Crystallography and cryoelectron microscopy have provided extensive structural information about local energetic minima in these functional landscapes. Recent experimental advances in techniques such as single molecule Förster resonance energy transfer and nuclear magnetic resonance have shown that proteins and large molecular assemblies are highly dynamic. These motions take place over large-length and long-time scales. While these experimental studies have provided tremendous insights into the functional dynamics of biomolecular systems, computer simulations offer the potential to bridge static structural data with dynamic experiments at atomic resolution.

Consideration of a fundamental dynamic process, folding, has motivated the energy landscape theory of protein folding (1–3). The theory states that evolution has achieved folding robustness by selecting for sequences where the interactions present in the functionally competent states are mutually consistent. The energy landscape for such sequences has an overall funnel shape, which has an enormous influence on folding mechanisms. Computational models that take advantage of the funneled nature of the energy landscape are called ‘structure-based models' (SBM) (4,5). The success of SBM and their interplay with experiments has led to a deeper understanding of the underlying physical properties that determine folding dynamics (3).

Since the funneled energy landscape upon which biomolecules fold is the same landscape that governs the functionally important motions, SBM have been used to study long-time and large-length scale molecular dynamics, e.g. (3–10). The simplest varieties of SBM are coarse-grained, where each residue is represented by a single bead and only the interactions present in the native state are attractive (4). All-atom SBM allow a more explicit connection with experimental observables and have been used to understand the interplay between side chain and backbone dynamics during protein and RNA folding (5,6).

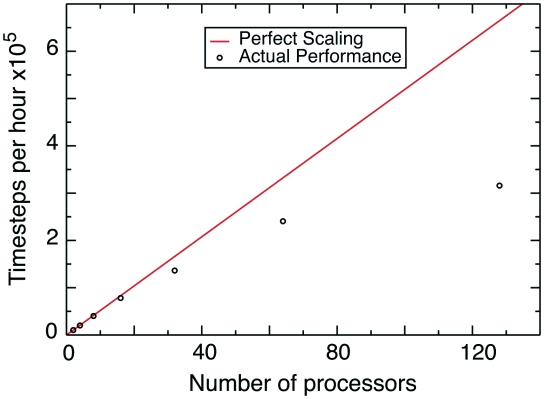

The SMOG@ctbp web server is available to facilitate creation and use of SBM to investigate the dynamics of proteins, RNA and DNA. Both Cα (4) and all-atom (5,6) models are available. The SBM represents a baseline model upon which additional complexity can be added by the user. Any PDB structure consisting of any number of chains of standard amino acids, RNA, DNA and a small library of ligands can be directly uploaded to the web server. The necessary files to implement the SBM in GROMACS (11) are provided as output. GROMACS is a state-of-the-art open-source molecular dynamics package that has the flexibility necessary to implement an efficient and highly scalable SBM (Figure 1; [10]). In this article, we describe the structure-based Hamiltonian and web server located at http://smog.ucsd.edu. Further explanation is included in the Supplementary Data and on the web server itself.

Figure 1.

Performance of an all-atom structure-based simulation with GROMACS version 4.0.5 for a ribosome with 142 196 atoms (PDB codes: 2WDG, 2WDH). The system scales up to 32–64 processors before significant performance loss. Due to large amounts of empty space inside the ribosome, this represents a lower bound on potential scalability. See Supplementary Data for more detail.

METHODS

Formulation of the Hamiltonian

In the creation of GROMACS topology files, the web server uses previously published and validated structure-based Hamiltonians for the Cα (4) and all-atom (5,6) models. The functional form of the Cα Hamiltonian  is,

is,

|

(1) |

and the all-atom Hamiltonian  is,

is,

|

(2) |

where the dihedral potential  is,

is,

| (3) |

A comprehensive listing and explanation of the parameters is available elsewhere (4–6). Here, we provide an overview of the forcefields for new users of these models. All geometrical parameters are determined from the provided PDB structure, such that the lowest energy value of each term corresponds to the PDB file configuration. Accordingly, by construction, the lowest energy configuration is the PDB structure. If multiple chains are present, any contacts between chains are equal in strength to intra-chain contacts.

The Cα model is defined only for proteins. Cα representations of RNA and DNA are not supported. In the Cα model, each residue is represented by a single bead, located at the position of the Cα atom. Bonds, bond angles and backbone dihedrals are between two, three and four consecutive beads, respectively. Backbone dihedrals and contacts are equally weighted and contacts are defined between native residue contacts.

The all-atom model includes each heavy atom and hydrogens are excluded. Since the atomic geometry is explicitly represented, bonds, bond angles and dihedrals have their traditional meanings. Improper dihedrals are included to preserve chirality, and where necessary, planarity. Contacts are defined between native atom pairs. In contrast to the Cα model, the overall interaction strength between residues is heterogeneous, since residues can have differing numbers native atom–atom pairs. This heterogeneity was shown to have only a weak effect on overall folding mechanisms for small globular proteins (5), though the small differences that arise can increase the agreement between experimental and theoretical ϕ-values (12).

Contact map

The SBM Hamiltonian can be roughly partitioned into two components, local terms to maintain the geometry and local bias, and non-local terms to provide the excluded volume and tertiary bias. The biasing non-local terms are contained within a ‘native contact map' and are called ‘contacts’. It should be noted that a subset of these contacts which are between atoms close in sequence, in particular 1–5 interactions, contribute to the local bias. Any atoms not interacting through a contact, bond, angle or dihedral, are considered ‘non-contacts' and interact only through excluded volume. In the Cα model, the contacts are defined between residue pairs and in the all-atom model between atom pairs. The contacts are determined from the given PDB structure. A pair of residues is defined as being in contact if any shared atom pair is in contact. In this web tool, we allow three possible definitions of native contacts: a ‘Cut-off’ distance criteria, the `Shadow’ algorithm or ‘User Defined’. The cut-off criterion defines two atoms in contact if the atom centers are within 4 Å in the provided PDB structure. The Shadow definition considers all atom pairs within a 6 Å cut-off and then excludes any atom pairs which have an occluding atom (Figure 2). Essentially, Shadow attempts to determine all contacts between interior protein surfaces without allowing atoms to interact through other atoms. The Shadow algorithm is explained in detail on the web server and is the subject of ongoing investigations.

Figure 2.

Shadow contact algorithm. To determine the contacts of atom  , all atoms within a cut-off radius of atom

, all atoms within a cut-off radius of atom  are considered. The algorithm effectively replaces atom

are considered. The algorithm effectively replaces atom  with a light source. Adjacent atoms are represented as opaque spheres with a radius of 1Å. All atoms within the cut-off that have a shadow cast upon them are discarded. The remaining atoms within the cut-off are defined as ‘in contact’ with atom

with a light source. Adjacent atoms are represented as opaque spheres with a radius of 1Å. All atoms within the cut-off that have a shadow cast upon them are discarded. The remaining atoms within the cut-off are defined as ‘in contact’ with atom  .

.

IMPLEMENTING A STRUCTURE-BASED MODEL IN GROMACS

Web server interaction

The main purpose of the web server is to create the input files necessary to simulate a biomolecular system with a SBM in GROMACS (Figure 3). A PDB structure that is uploaded from the user's computer is the only required input. While most PDB structures can be directly downloaded from the PDB database and used with the web tool, users should verify that the PDB file conforms to the guidelines described below and in the Supplementary Data. A valid PDB file has a TER statement (left justified) in between each chain and an END statement (left justified) at the end. The following residues are supported by the web tool:

Protein residues: all standard 20 amino acids (three letter codes used).

RNA residues: CYT or C, GUA or G, URA or U and ADE or A.

DNA residues: DG, DC, DA, DT.

Ligands: SAM (S-adenosylmethionine), GNP (Gpp(NH)p), ATP, ADP, AMP

Figure 3.

Flowchart explaining the logic of the SMOG@ctbp web server.

Upon request, additional ligands may be supported.

The web page where the PDB file is uploaded is entitled ‘Prepare a Simulation’ and is where all user input is obtained. Beyond uploading a PDB file, the web server interface allows the user to customize some basic parameters of the SBM Hamiltonian:

The level of graining: it can be varied between all-atom and Cα.

The contact map: the user can upload a native contact map or generate a map by choosing either the cut-off or Shadow algorithm. The contact map algorithms are based on the all-atom geometry, thus PDB files that lack some heavy atoms must be manually inspected to ensure proper performance.

The distribution of stabilizing energy: it can be varied between contacts, backbone dihedrals and side chain dihedrals. This is explored in detail (5).

The size of atoms: this can be controlled through

.

.The buffer space: the space between the system and the simulation box is an important parameter. Improved performance and effective parallelization in GROMACS depends on periodic boundary conditions being employed. When using the ‘dynamic load balancing’ features of GROMACS, excessive volumes of empty space can lead to poor scalability. Though, if the simulation box size is too small, the system can interact with its image. While the default 10Å buffer is sufficient for many simulations, for folding, the box size should be nearly the linear length of the molecule.

After uploading a PDB file, inspecting the above parameters, and pressing the ‘Submit’ button, the web server will either return a link to the completed output or return an error message describing any formatting inconsistencies. The completed output is a tarball containing:

GROMACS coordinate file: the initial structure corresponding to the provided PDB structure; shifted such that the box starts at the origin (.gro).

GROMACS topology file: describes all the atomic interactions in the SBM Hamiltonian (.top).

GROMACS index file: convenient for manipulating structures with multiple chains (.ndx).

Native contact map: if Shadow is selected (.contact).

Web server output: contains any non-fatal warnings and messages (.output).

Molecular dynamics with GROMACS

In order to run molecular dynamics, the user must have access to a compiled GROMACS 4 distribution. The GROMACS source code can be found at http://www.gromacs.org. The topology file and coordinate file, along with a molecular dynamics parameter settings file (.mdp) are sufficient to run the SBM in GROMACS. A suggested .mdp is available on the web server. Example output for an SH3 domain is shown in Figure 4. See the web server or the Supplementary Data for a brief tutorial highlighting the relevant GROMACS syntax and things to consider.

Figure 4.

SBM of SH3 domain. PDB code: 1FMK. Top Left: Cartoon representation of SH3 domain. Bottom Left: Cα model geometry. Bottom Middle: All-atom model geometry. Top Right: Contact map for SH3. Upper triangle shows 4Å cut-off and lower triangle shows Shadow. Coloring is by number of atom–atom pairs per residue–residue contact. Bottom Right: Folding of 57-residue SH3 domain at constant reduced temperature  with the all-atom model. Residues 84–140 taken directly from 1FMK.pdb and submitted at SMOG@ctbp with default parameters and Shadow contact map. MD parameters file taken from the web server example.

with the all-atom model. Residues 84–140 taken directly from 1FMK.pdb and submitted at SMOG@ctbp with default parameters and Shadow contact map. MD parameters file taken from the web server example.

CONCLUSION

In this article, we describe SMOG@ctbp, a web server that creates the necessary files to simulate a SBM in GROMACS from a provided PDB structure. The all-atom SBM represents a baseline model that the user is welcome to augment and explore with system-dependent details, e.g. electrostatics or non-native interactions. The possible applications of SBM go beyond equilibrium and kinetic molecular dynamics. A SBM is a starting point for any study where the overall geometry of the biomolecules is maintained, e.g. fitting crystallographic structures into cryoelectron microscopy maps (13) and predicting protein–DNA complexes (14). Hopefully, SMOG@ctbp will enable users to conceive of more new and exciting applications of SBM.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Center for Theoretical Biological Physics, National Science Foundation (PHY-0822283, NSF-MCB-0543906); the LANL LDRD program; National Institutes of Health (R01-GM072686); National Institutes of Health Molecular Biophysics Training Program at University of California at San Diego (T32GM08326 to J.K.N.). P.C.W. is currently funded by a LANL Director's Fellowship. Funding for open access charge: Center for Theoretical Biological Physics at UCSD.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the New Mexico Computing Applications Center for computing time on the Encanto Supercomputer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bryngelson JD, Wolynes PG. Spin-glasses and the statistical mechanics of protein folding. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1987;84:7524–7528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leopold PE, Montal M, Onuchic JN. Protein folding funnels - a kinetic approach to the sequence structure relationship. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;18:8721–8725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onuchic JN, Wolynes PG. Theory of protein folding. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004;14:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clementi C, Nymeyer H, Onuchic JN. Topological and energetic factors: what determines the structural details of the transition state ensemble and `en-route intermediates for protein folding? An investigation for small globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:937–953. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitford PC, Noel JK, Gosavi S, Schug A, Sanbonmatsu KY, Onuchic JN. An all-atom structure-based potential for proteins: bridging minimal models with all-atom empirical forcefields. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinf. 2009;75:430–441. doi: 10.1002/prot.22253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitford PC, Schug A, Saunders J, Hennelly SP, Onuchic JN, Sanbonmatsu KY. Nonlocal helix formation is key to understanding S-adenosylmethionine-1 riboswitch function. Biophys. J. 2009;96:L7–L9. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitford PC, Miyashita O, Levy Y, Onuchic JN. Conformational transitions of adenylate kinase: switching by cracking. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;366:1661–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.11.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyeon C, Onuchic JN. Mechanical control of the directional stepping dynamics of the kinesin motor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17382–17387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708828104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus DL, Cho SS, Hyeon CB, Thirumalai D. Minimal models for proteins and RNA: from folding to function. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2008;84:203–250. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)00406-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitford PC, Geggier P, Altman RB, Blanchard SC, Onuchic JN, Sanbonmatsu KY. Accommodation of aminoacyl-tRNA into the ribosome involves reversible excursions along multiple pathways. (RNA) 2010;16:1196–1204. doi: 10.1261/rna.2035410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clementi C, Garca AE, Onuchic JN. Interplay among tertiary contacts, secondary structure formation and side-chain packing in the protein folding mechanism: all-atom representation study of protein L. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;326:933–954. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01379-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orzechowski M, Tama F. Flexible fitting of high-resolution X-ray structures into cryoelectron microscopy maps using biased molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5692–5705. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.139451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schug A, Weigt M, Onuchic JN, Hwa T, Szurmant H. High-resolution protein complexes from integrating genomic information with molecular simulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:22124–22129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912100106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.