Abstract

China faces a rapidly emerging HIV epidemic and nation wide resurgence of sexually transmitted infections associated with a growing sex industry. Community empowerment and capacity building through community-based participatory research partnerships show promise for developing, testing, and refining multilevel interventions suited to the local context that are effective and appropriate to address these concerns. However, such efforts are fraught with challenges, both for community collaborators and for researchers. We have built an international team of scientists from Beijing and the U.S. and collaborating health policy makers, health educators and care providers from Hainan and Guangxi Province CDCs and the local counties and towns where we are conducting our study. This team is in the process of testing a community wide, multi-level intervention to promote female condoms and other HIV prevention within sex-work establishments. This article presents lessons learned from our experiences in the first two study sites of this intervention trial.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, HIV/AIDS prevention, China, female condom, sex work, multilevel intervention

INTRODUCTION

Context of HIV in China

HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases (STD) have become critical concerns in China in the past two decades. China faces a resurgence of STD that were reported to be virtually eradicated by the 1960s (X. S. Chen et al., 2006; Z. Q. Chen et al., 2007; Cohen, Henderson, Aiello, & Zheng, 1996; Cohen, Ping, Fox, & Henderson, 2000; van den Hoek et al., 2001). Between 1985 and 2001 the number of reported STD increased by a hundred fold (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004), with syphilis alone rising from 0.2 cases per 100,000 in 1993 to 5.7 per 100,000 in 2005 (Z. Q. Chen et al., 2007). This sets the stage for increased HIV transmission through heterosexual contact in the country. In fact, the incidence of HIV infections is also increasing rapidly. The Chinese State Council AIDS Working Committee & UN Theme Group on AIDS in China estimated that 700,000 were living with HIV in 2007. Among those living with HIV, 40.6% were infected through heterosexual transmission (Chinese Ministry of Health, 2007; Chinese Ministry of Health and WHO, 2007; Hong & Li, 2008b).

Though having made tremendous changes in policies and investment in HIV/AIDS in the past decade, the Chinese official response to the epidemic has been hampered by various structural, cultural and behavioral barriers (UNAIDS/WHO, 2004; L. Wang, 2007; Zhang, Detals, Liao, Cohen, & Yu, 2008; Zhang & Ma, 2002). HIV/AIDS campaigns have been launched in China for many years, but the extent of their effectiveness is limited (Hong & Li, 2008a). The population’s knowledge of the disease remains relatively superficial and perception of risk is extremely low, in contrast to actual potential for risk exposure, especially in some rural areas of China (Hu, Liu, Li, Stanton, & Chen, 2006; Liao, 1998; J. Wang, Jiang, Siegal, Falck, & Carlson, 2001). Additionally, social stigma associated with an HIV diagnosis, as well as with identification as a drug user, sex worker, or gay man, and the resulting potential for discrimination generate reluctance to access testing, treatment, or sources of information on prevention (J. Chen, Choe, Chen, & Zhang, 2007; Gil, Wang, Anderson, Lin, & Wu, 1996; McCarthy, 1999; L. Wang, 2007; Zhang et al., 2008). Further, the illegal nature of both drug use and prostitution and the potential severity of punishment for getting caught tend to push those at risk into hiding from officials. Fear of discovery may contribute to increased risk and barriers to accessing prevention information and materials (Cohen et al., 2000; Yang & Xia, 2006).

This complex problem and the growing epidemic require a comprehensive response. Increasing evidence suggests that theoretically grounded and locally implemented prevention efforts that build on community resources and enhance local capacity to address these problems lead to effective, culturally appropriate and sustainable action. Community-wide and multi-level interventions in particular are indicated to be most promising for addressing the complex intersection of factors affecting HIV risk and prevention (Fuller et al., 2007; Jana, Basu, Rotheram-Borus, & Newman, 2004). This is especially the case when tested in collaborations between researchers and community stakeholders.

Our team of scientists, public health educators, advocates, and health care workers joined together to develop, implement, and test a community-wide HIV prevention intervention. The China/U.S. Women’s Health Project, funded by the National Institute on Mental Health (R01 MH077541), is designed to promote the female condom (FC) as an HIV/STD prevention option among women working in sex work establishments in four rural and small urban towns in southern China. The approach we are using is built on principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). Our team recognized that community input enhances the relevance and the cultural and social congruence of such efforts through the use of local resources (e.g., community knowledge, experience, available services and other resources) enhanced with an infusion of new information and capacity offered by scientific knowledge and theory. We also recognized that such collaboration between indigenous public health workers and institutions and supportive researchers to build and implement the program would increase the ability to sustain it in the real-world context of local communities. However, these collaborations also generate unique challenges. Now in the third year of our five-year project, we have recently completed intervention and process evaluation efforts in the first two rural study sites (referred to here as FS and YF) in one county in Hainan Province. This experience has resulted in significant lessons learned, which have informed our plans for repeating the intervention and evaluation in the next two study sites.

The following provides a brief overview of the CBPR approach as it informed the development and implementation of our community prevention effort. We describe the model we used to design and carry out our collaborative community intervention test as we implemented it in the first two study sites, and discuss several key experiences illustrating significant components of the project. We then offer lessons learned for other scientists and community partners interested in implementing similar research and public health efforts in community settings.

Community Empowerment and the CBPR Approach

Principles of CBPR derive from a framework in public health education premised on the concept of empowerment of those whose health is at stake as a mechanism of their own health enhancement (Brown, 1991; Labonte, 1994; Robertson & Minkler, 1994). Empowerment is a multi-level concept theorized to work on the individual level (e.g., through critical consciousness) (Freire, 1970), the group level (e.g., through social identity development) (Campbell & MacPhail, 2002; Drury, Cocking, Beale, Hanson, & Rapley, 2005), the community level (e.g., through capacity building or community organizing) (Israel, Checkoway, Schulz, & Zimmerman, 1994; Minkler & Wallerstein, 1997), and the nation-state level (e.g., through independence movements) (Freire, 1970). The concept of empowerment has been used to refer to both internal processes, such as indigenous movements and organized efforts, and external resources, such as an influx of support and capacity building assistance from “outside” entities. Both of these serve to expand the capacity of community interests to participate in and insist on their own health.

This health promotion movement and associated empowerment approach have been applied to HIV prevention in varying ways within diverse settings with the goal to enhance outcomes at the social/community level and to encourage and support sustainability. The approach has had notable success (Beeker, Guenther-Grey, & Raj, 1998; T. Rhodes & Hartnoll, 1996; J. Schensul, 2005). Efforts like the harm reduction movement (van Ameijden, 1992), community readiness assessments (McCoy, Malow, Edwards, Thurland, & Rosenberg, 2007; Thurman, Vernon, & Plested, 2007), and other efforts to organize high-risk groups for HIV prevention (Jana et al., 2004; Jose et al., 1996; Romero et al., 2006; Weeks et al., 2009) are consistent with this community empowerment approach. Evidence increasingly supports the development of multi-level interventions using a community-empowerment intervention model to mobilize sectors of the community who have an interest in or desire to move HIV prevention forward in a sustained way (Beeker et al., 1998; Rotheram-Borus & Duan, 2003; Trickett, 2009).

Testing these multi-level community empowerment interventions, including in multi-cultural and international contexts, creates numerous challenges, most notably, the need for local cooperation and engagement in the intervention research effort. The most promising approach to meet the challenges of developing and testing community-wide and multi-level interventions is through community-based collaborative and participatory research (CBPR) (Foster & Stanek, 2007; Israel, Eng, Schulz, Parker, & Satcher, 2005; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Nyamathi et al., 2004; S. D. Rhodes et al., 2006; J. J. Schensul, 2005). CBPR applies concepts of community empowerment for social change through the research process (Israel et al., 2005; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). The method is based on the assumption that scientifically derived knowledge and community practical knowledge are equally valid, and that coalescence, integration, and synthesis of the two results in the best outcomes and most applicable findings (Foster & Stanek, 2007; Israel et al., 1994; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). CBPR involves community input and engagement by key stakeholders in all aspects of the design, development, implementation, and testing of the model. It has been shown to be effective for testing complex community-level interventions (Israel et al., 2005; Jana et al., 2004; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003; Schensul, 1998; Trickett, 2005), including HIV prevention interventions for at-risk populations (Fuller et al., 2007; Marcus et al., 2004; Nyamathi et al., 2004; S. D. Rhodes et al., 2006). CBCR offers great promise for generating an effective process by building infrastructure that utilizes existing resources (human, political, economic) and for sustaining intervention efforts over time (Altman, 1995; Jana et al., 2004; J. J. Schensul, 2005).

PROJECT DESIGN AND METHODS

Community/Research Partnership of the China/U.S. Women’s Health Project

The partnership engaged in the work described here was established and then expanded through two grants from the National Institute on Mental Health.1 The consortium was developed to study HIV risk and prevention among southern Chinese sex workers in Hainan and Guangxi Provinces and to enhance local prevention efforts to reach women working in the sex industry. Collaborators include investigators at the Department of Epidemiology at Peking Union Medical College/China Academy of Medical Sciences (PUMC/CAMS) in Beijing, China, and at the Institute for Community Research (ICR), a non-profit community research organization based in Hartford, Connecticut in the United States. They also include leaders, health educators, and public health service providers from the HIV/AIDS Divisions of the Hainan and Guangxi Provincial Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDCs) and the county-level CDCs where the research takes place. The project’s intervention trial is staffed part-time with local health workers (e.g., nurses, gynecologists) and public health educators who work in the government-run township hospitals in each of the study towns. A full-time local intervention assistant is also hired by the project in each town to work with the trained health professionals. Joint efforts of key collaborators from Beijing, Hainan and Guangxi have continued for over 15 years, and the U.S./China partnership has existed for nearly a decade. This long-term commitment and continued joint efforts have contributed greatly to the consortium’s successful implementation of community research on HIV prevention.

The collaboration began with prior efforts of the Chinese lead investigator to increase male condom (MC) use among female sex workers through community wide promotional efforts in these towns, and was followed with a study by the international team regarding the potential acceptability of microbicides as an option for women’s HIV prevention. The initial study to evaluate community wide MC promotion among sex workers was built on participatory involvement of local health education resources and staff. Findings from the study indicated that women sex workers significantly increased their use of MC as a result of this effort (Liao et al., 2006; Liao, Schensul, & Wolffers, 2003). Likewise, our mixed methodology exploration of factors that affect women’s readiness for and willingness to use vaginal microbicides (products used during sex to kill or prevent the transmission of HIV) helped us identify key dynamics in the relationships among women within establishments and between women and their “bosses” (the establishment owners) that created potential for effective site-base prevention dissemination. These included mutual support for prevention of unwanted pregnancy and risk of STD (Y. Wang et al., 2008; Weeks et al., 2007). Further, in qualitative interviews with sex workers in that study, they described using a wide variety of both effective and ineffective HIV/STD prevention methods when they could not get partners to use MC, suggesting the potential value of promoting and supporting the woman-initiated FC. However, several questions also arose that pointed to potential methodological concerns for testing a multi-level, site-based intervention in sex-work establishments, such as the stability of sites and sex workers and the dynamics and key factors within establishments that might affect the implementation, effectiveness, and sustainability of an intervention placed there to increase use of FC. These challenges are exacerbated given that the product is so new and requires significant ongoing support in order for women to begin to adopt it as a viable prevention option.

With our strong consortium and the significant knowledge and experience gained from our prior research, we developed the current FC intervention study, known in the local communities as the China/U.S. Women’s Health Project. The project is an intensive ethnographic, behavioral, and epidemiological study of sex-work establishments in four study towns aimed to design, implement and test an establishment-based and community wide prevention intervention to promote FC. It is delivered by local health workers and supported and evaluated by provincial and county CDC public health workers, with scientific contributions from the U.S. and Chinese investigators. Sex-work establishments in these towns include massage and beauty parlors, boarding homes, hotels, and roadside restaurants where sex work is either the primary business or a covert activity. Many of the women in these establishments are migrants from other parts of China, some of whom return to those places or move on to other locations after a few years. Others live with a steady paying partner in the study town where they engage in sex work while maintaining a household in a distant hometown for many years.

This study uses multiple and mixed methods to conduct formative research, intervention implementation, and process and outcome evaluation. Ethnographers from ICR and PUMC begin in each study site with formative ethnography to gain entree and explore the contexts and dynamics inside sex-work establishments in the study towns (e.g., relationships among women, bosses, and clients). They also explore the contexts of women’s HIV/STD risks and protections within these establishments and other characteristics of the study towns. They use in-depth interviews and field observations in the establishments and in local health organizations to assess the potential for a locally run social and behavioral intervention to promote FC for HIV/STD prevention. The formative ethnography is designed to inform the content, assist in tailoring components, and facilitate implementation procedures of a multi-level intervention anticipated to change the environment of risk and protection within the sex-work establishments by making use of site dynamics and local health promotion resources to increase information, access, support, and use of FC. Health care providers and health educators from the local township hospitals, who work part-time on the project, and the full-time local project intervention assistants then receive training (described more fully below) to implement the intervention in selected or all establishments in the town over a 6-month period. Additionally, a community Women’s Center is established in each study town, where women can go repeatedly for additional support, information, and FC if desired. Care was taken in selecting the location of the Center (e.g., within the hospital in one town and near the central market area in the second) both to maximize convenient access and to avoid drawing attention to or stigmatizing those who entered there. The Women’s Centers were advertised as a place where all women could access general health information and referrals for health services.

Outcomes of the intervention are being assessed by comparing a baseline cross-sectional survey of women working in those establishments and two post-intervention cross-sectional surveys at 6-months and 12-months after the baseline to measure community-wide changes in FC recognition, initiation and adoption among women in sex work establishments. When possible, we also will attempt to link baseline to follow-up surveys of women interviewed at multiple time points. The ethnographers are concurrently conducting intensive documentation of intervention process and outcomes. Findings of this test will be reported elsewhere; in this paper we describe our CBPR process and experiences useful for guiding our continued work as well as other intervention efforts of this nature.

Collaboration to Test a Multi-level Community Intervention to Promote FC in Sex Work Establishments

Structure and Staffing of the Consortium

As with our prior joint research efforts and following a model ICR has used for two decades in community research in Hartford, Connecticut (Singer & Weeks, 2005), we built a strong researcher/community collaborative effort with shared input, resources, research responsibilities, and ownership of project findings to conduct this study. The partnership model began with input from local key public health leaders and educators at the provincial, county, and township levels, whose knowledge of the local HIV and STD epidemics and characteristics of the sex work industry in their jurisdictions guided conceptualization of the steps needed to implement formative and intervention research in the study towns. Their guidance in the early years of STD prevention research helped to determine which towns should be the focus of study because of the significance of the sex industry in those towns and the lack of other focused research and prevention efforts there. Working within the hierarchically nested public health structure from the provincial down to the local township levels, a hallmark of Chinese political organization, has provided the necessary infrastructure of support and oversight to develop contractual shared responsibilities in this study. Having the support of the county and provincial CDCs has also increased the likelihood of longer term sustainability of intervention efforts in the townships in which services are ultimately provided. Meetings between key investigators from PUMC and ICR with the HIV division leaders of the provincial and county CDCs prior to funding of the study helped collaborators to determine the feasibility of conducting research and intervention in the selected towns, to identify local staffing needs and opportunities to conduct intervention activities, and to notify on-the-ground leaders of the basic requirements for conducting a study of this nature. These meetings included discussion of requirements for responsible and ethical conduct of research and protection of human subjects.

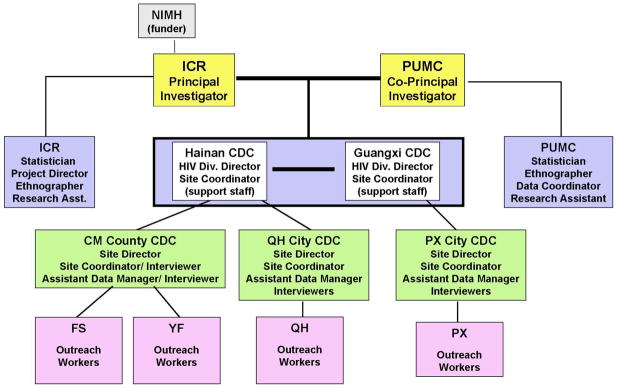

On the basis of those initial and subsequent meetings, a structure of research and intervention leadership and division of roles and responsibilities among all collaborating parties was decided (see Figure 1). This structure placed research oversight at the two institutions of the principal investigator at ICR and the co-principal investigator at PUMC, in each of which was place a community ethnographer and statistical data analysts. Data collection and management responsibilities, primarily for pre/post-intervention cross-sectional surveys and intervention tracking forms, were assigned to the provincial and county level CDCs, as was oversight of intervention related activities. Intervention implementation was assigned to staff at the township level, who had the greatest and most sustained access to local establishments where sex work and prevention intervention would take place. These local outreach staff were trained in the intervention protocol by key investigators, and supported in handling problems during implementation by both the county and provincial CDC leadership and the research field team and investigators.

Figure 1.

China/U.S. Women’s Health Study Staff and Organisational Structure

Despite the benefits of shared responsibilities and input from stakeholders at multiple levels, the project has faced significant staffing and other challenges. The first problem was to identify and hire or assign appropriate staff for local project related roles, such as outreach, health education, and data management. The temporary nature of employment on a time-limited research project contributed to this difficulty. The project needed experienced staff to take the lead in organizing key intervention and research activities on the community level. However, most experienced health workers were already overly committed with other work providing general and reproductive health care at the township hospital. They could contribute only limited time to the project. Moreover, local staff hired to work full-time on the project tended to have less experience with the target population, and required significant support from both township and research staff. In particular, they had limited ability to handle reproductive health or sex related questions of women in the sex work establishments. The more experienced health care providers from the township hospitals could handle such questions easily, but they were less present in the field. Also, some of the experienced staff had previously gained access to sex work establishments to provide health education and HIV prevention intervention, along with delivery of MC, whereas new staff on the project needed to gain confidence and build rapport for a period of time before they were fully comfortable with the process. These staffing challenges and support issues were an ongoing focus of regular project meetings.

We initiated each cycle of research and intervention activities in the study towns with an intensive 3–5 day training program to inform local staff of the study design, research and intervention components, and human subjects protections protocols (for certification). Health professionals also trained new staff in women’s anatomy and reproductive health, and all staff were trained in use and difficulties of the FC. New staff were also oriented to intervention implementation by first accompanying experienced staff into the sites until they were more comfortable with the process and content of the program. This training was supplemented with follow-up guidance in ongoing project meetings as health or project related questions arose in the process of intervention implementation. In addition to this capacity building focus, staff from the local townships provided feedback on the preliminary findings of the formative ethnography and input on questions about planned sampling and recruitment protocols for the surveys. They also identified local conditions in the towns and within sex work establishments that helped to inform development of the HIV prevention intervention to be implemented in the local sex-work establishments.

Conducting Formative Ethnographic Research

Ethnographers began formative documentation by walking through each study town accompanied by either the experienced outreach coordinator from the local township hospital, the newly hired full-time project staff, other part-time outreach staff on the project, or the county-level coordinator, who was fully familiar with each of the study towns in her county. Initial ethnographic observations were used to develop a community map of key locations, informally drawn to show sex-work establishments in relation to township services, but sufficiently undefined and codified to protect confidentiality of the establishments.

Local staff were familiar with the location of most places where sex work takes place and had previously built rapport with some of the establishment owners. Accessing the sites required a careful process in which local staff offered HIV prevention information, support, and MC, as well as other health information and referrals to local health services, while assisting the ethnographers and engaging with those present at the site in informal interviews. Existing rapport of the local outreach staff provided initial establishment entree to the ethnographers, who subsequently built their own relationships with establishment owners and women sex workers. Occasionally, involvement of local staff made the difference in the ethnographer’s ability to gain access to women in the establishments, as illustrated by the following summary field notes:

In YF, one of the boarding houses was a little difficult for me to enter. The establishment owner is an older man who can’t speak Mandarin well, and though I tried to communicate with him several times, it was hard to achieve my aim. Moreover, he didn’t want to talk with us strangers. But all that changed after a visit accompanied by YZ [the full time outreach worker in YF]. While I conducted an informal interview in the room of a woman who lived there, YZ chatted with the owner outside. YZ told me that her aunt and the owner’s daughter are good friends. YZ and his grandson are schoolmates. The owner was more cooperative about our work after that visit. We had good conversations several times.

The outreach workers’ deep knowledge of the local residents and regional dialects, and their long term relations with local people were also occasionally crucial for resolving tense encounters between researchers and participants. In one example of this, the ethnographer was conducting an in-depth interview with a local Li minority sex worker in a roadside restaurant establishment when the woman became increasingly uncomfortable and anxious with the interview process and the ethnographer’s note-taking, and eventually refused to participate in any aspect of the study. She expressed her concerns about feeling interrogated to the other women in the establishment and to the project outreach worker using Hainan dialect, which the ethnographer could not understand. The outreach worker felt the need to talk with the woman for a long time, also in Hainan dialect, to calm her fears and convince her that the information she shared with the ethnographer would never be used against her or turned over to the authorities. The outreach worker’s efforts and skill in addressing the woman’s concerns, her ability to converse in the local dialect, and her understanding of the local political environment regarding the sex industry as experienced by this woman were essential capacities that researchers from the “outside” did not have. The ethnographers were subsequently able to conduct interviews with other women at this establishment; however, the woman who expressed concerns was not pressed and did not choose to participate any further in the project research or intervention.

Conducting Surveys at Baseline and 6-Month Follow-up

Upon completion of 4–5 months of exploratory formative ethnography, we conducted a baseline survey of women recruited from the sex work establishments. Our first challenge was to achieve the recruitment goal of at least 80% of all women in these establishments in each town, based on local estimates. Feedback from the local staff and our prior research confirmed that some establishments also provide non-sex services (massage, hair and beauty services, etc.), and employed women who might not yet (or perhaps ever) have engaged in sex work, along with women who might exclusively have done so. Some women declared that they were sexually active but only with boyfriends. Considering the difficulty to differentiate sex work from other sexual relationships in some establishments and the potential for under-reporting of engagement in sex work because of its illegal nature, we decided to include all sexually active women, even if they did not report having had sex for money in the prior thirty days, and to define the inclusion criteria as being 16 years of age or older and having had sex with a man in the past month. This had the added advantage of reducing identification of the project as targeting sex workers and allowed local staff to emphasize the value of FC for all women.

Despite this, the focus of recruitment on sex work establishments was clear to many women and establishment owners. It discouraged some women from participating in the survey and made some proprietors reluctant to allow staff access to the site. Particularly in YF, many proprietors were local people and were concerned about being associated with HIV or with sex services. They were therefore reluctant to organize the women in the establishment to take part in the survey. Other barriers to recruitment included the tendency for women to spend time when they were not busy playing majiang, a Chinese board game used for gambling, which they often refused to abandon when asked to participate in the survey. Further, establishment owners sometimes did not want to allow women to leave the site to participate in the hour-long survey in case clients should arrive in the interim and then leave because the women were not present. Moreover, some women were reluctant to come to the interview site (a local hotel) where surveys were being conducted for fear of being recognized and, in the early part of the study, because rumors had begun that women were being brought to the interview site to be photographed for pornography. Strategies were needed to address each of these barriers to survey recruitment.

Deep understanding of local culture and the ability to negotiate effectively with establishment owners made local outreach staff highly instrumental both in discovering these recruitment barriers and in facilitating their resolution. Staff addressed fears of stigma associated with project participation by encouraging broad-based promotion of FC. In order to avoid using potentially disturbing terms such as “AIDS” and “high risk” that were in the research proposal title, staff used the title China/U.S. Women’s Health Project in all project introductions and documents. We emphasized that all sexually active women might be protected by using a FC from HIV/AIDS, STDs or unwanted pregnancy. In some establishments, local project staff negotiated the option to conduct the survey in safe, private rooms on site, thereby minimizing women’s absence from the worksite and increasing the rate of survey participation. To help allay rumors in one town, an outspoken female proprietor was recruited to take the survey, who then reported to others in the business that no photographs were being taken or other illicit or inappropriate activities during the private interviews.

Local input was also critical for identifying appropriate incentives for participation in the survey, which included non-cash gifts (beauty products, scarves, pajamas) that were sufficiently attractive but did not constitute a coercive enticement to participate. Likewise, these staff were essential in making arrangements to identify appropriate space centrally located in each town where survey interviewing could take place in privacy and without drawing undue attention to women entering the site to participate in research activities. In both towns, this occurred in rented rooms in a local hotel. Through this combination of strategies and the benefit of rapport local outreach workers had built over time, we were able to achieve our recruitment goals for the baseline, within the limited time frame of about a month, to get representation from 100% of the known establishments in FS and over 85% of the establishments in YF. This success was beyond the expectations of both the researchers and the local outreach staff. Most significant to the success was the county-level staff’s and the outreach workers’ full understanding of the project’s research goals and their commitment to facilitating the achievement of those goals.

Follow-up recruitment of women generated a two-fold set of challenges. The first concern was the unknown but expected high rate of turnover of the women; the second was the local staff’s perception of the difficulty of follow-up survey recruitment. The first challenge was addressed by designing a cross-sectional outcome evaluation, recruiting 80% or more women in the sex industry in each town at each time point. In this way, our outcome evaluation will be based on the study population rather than a sample. Further, because of the expected high turnover rate, our intervention is establishment focused, so that women who started sex work in the town after the baseline might still have the opportunity to be exposed to our intervention via peers or ongoing staff outreach. Establishment level intervention dosage and individual level “time in this establishment” were measured for the cross-sectional outcome evaluation.

Besides this design, we proposed an alternative longitudinal design in case the turnover rate was not actually as high as we anticipated. Therefore, we still encouraged a process of attempting to match women who participated in both the baseline and follow-up surveys. This was made possible through use of a unique ID code that could be reconstructed at follow-up time points to allow matching of women’s surveys. This code was also written on a card women were asked to bring to the follow-up survey(s) to confirm their “identity.”

When presented with the follow-up protocols, local and county-level staff expressed significant worries about the recruitment process and the burden of research on the women, establishment owners, and local outreach staff. These concerns stemmed from participant feedback at baseline that the survey (which lasted nearly an hour from introduction and informed consent through completion) was too long. Staff believed that women who had completed a baseline would refuse to sit through the process a second time, and would discourage other women from doing so. Further, staff worried that establishment owners would be more resistant to releasing the women to participate, particularly in sites in which the FC was not well liked or used or where the owner did not support its promotion. A related research concern regarded the ability to match participants’ baseline and follow-up assessments. Local staff feared that most women would not return with their cards and matching would be impossible.

In response to these concerns, research and outreach staff devised a combination of attractive incentives (silk sleepwear valued at approximately $10 U.S.) that differed from the baseline incentives (health and beauty products valued at approximately $5–7 U.S.), with an added bonus for women who participated in both surveys (a silk scarf, valued at approximately $7 U.S.). Staff arranged dozens of these colorful gifts on a table and let each woman choose her preference; women enjoyed the process and occasionally stayed longer to chat briefly and casually with project staff. After completing surveys with women willing to come to the interview location, outreach staff escorted interviewers to some of the establishments and helped them gain entree in order to conduct surveys on site. This increased both the participation rate and the interviewers’ ability to identify women who had completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys.

These methods resulted in recruitment of nearly 98% of eligible women who worked in the sex work establishments at the time of the 6-month survey interviews, thus achieving a sample of nearly the whole population. However, though the refusal rate for participation in the follow-up surveys was unexpectedly low, turnover of sex workers in the establishments (47% of women had not been in town at the time of the baseline and only 36% indicated having seen a similar interview around the time of the baseline) plus limited return of ID cards (only 29 out of 154 women turned in their project card with unique ID) resulted in a less than ideal rate of matched surveys needed to conduct a cohort study (about 20% confirmed). Thus, our primary post-intervention analyses are limited (as anticipated) to cross-sectional assessments. Because of this, cross-sectional comparison of the sample (actually, the population) at different time points and post-intervention data modeling will be our only option for outcome evaluation. Nevertheless, preliminary comparison of baseline to 6-month data indicated that even women who had entered the establishments after the baseline was completed had been exposed to the establishment-based intervention and other project activities in the town within the prior six months. While complex methodological challenges remained given the difficulty of conducting a full cohort design with this sensitive and mobile population, intensive presence of researchers (ethnographers and interviewers) in the study locations and the partnership with local outreach staff who frequented the establishments and maintained steady relationships with owners and women deepened the project’s ability to gather systematic data through both qualitative (ethnographic) and quantitative (pre/post surveys and intervention tracking) methods.

Intervention Development and Implementation

Community input combined with evidence-based intervention knowledge contributed to finalization of the multi-level intervention design that is being used in this study. A lead Chinese member of our study team was consultant on a China-UK AIDS Prevention Program, sponsored by the United Kingdom Department for International Development, which ended in 2006. This program added FC promotion in the last year in two cities in Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces. Information from interviews with female sex workers in those cities, combined with experiences of the AIDS Prevention Program staff introducing the FC to these women, significantly shaped the design of our intervention (Cheng, Li, Wang et al., 2002). Their project reports and conference presentations provided us with an understanding of sex workers’ likes and dislikes of the FC, as well as how differently subgroups of sex workers have responded to FC and how they negotiated FC with their male partners. One important and useful message we learned from these projects was that most sex workers had little knowledge of their genital anatomy, which created much difficulty for them to understand FC insertion if it was demonstrated only with hands. Because of this, we purchased a portable plastic model vagina from the U.S. for our Chinese project staff to use in delivering intervention.

The development of our project’s intervention activities was also fully based on lessons learned from successes and failures of our previous intervention work, such as outreach in sex establishment in FS and YF to promote MC. With this learning, we were able to set an achievable, minimal level of FC education and demonstration to be implemented in each establishment. Additionally, during the process of development, we were able to share some of our intervention materials, such as the project poster, with women sex workers in the local county seat near our two study sites and invite their comments and suggestions.

The FC intervention has two primary components: a site-based small group multi-session activity to be conducted inside the sex-work establishments, and a community Women’s Center for individual intervention and large group organized activities. The primary component, the establishment-based small-group intervention, includes a 20–30 minute demonstration of proper FC insertion using hands and the plastic model of women’s anatomy, skills building for successful FC insertion and discard, negotiation with partners, and troubleshooting. This 20-minute program is intended for delivery to at least 80% of the women in each establishment, whether at one sitting or in several visits. This is to be followed by one or more small group or individual troubleshooting/support sessions to answer questions and concerns and provide additional support for initial or continued FC use. During the intervention sessions, staff emphasize increasing protected sex through use of FC when MC are unavailable or are refused and continued use of MC if FC are untenable or unaccepted. To supplement the establishment-based intervention and provide broader community support for FC, the community Women’s Center in each town is staffed several hours per week by the full-time project outreach worker; she makes FC available to women who drop in and provides them other health information and materials, including MC. On several occasions, group events have been organized and implemented either in the Women’s Center or elsewhere in the community (e.g., in some of the sex work establishments themselves) to provide fun opportunities, games and other relaxing social activities to keep women engaged with the project.

Prior to initiation of the intervention in each town, the county-level project staff and the township hospital director invited all primary health care providers from private clinics and the township hospital, local pharmacists, and several local government leaders to a public presentation. A total of 24 attended in one town and 20 in the other, including almost all health care providers in each. At this event, researchers and local staff introduced the project and demonstrated FC for the audience’s general information and to garner support for the intervention effort. Though this event required minimal commitment from these local providers and policy makers, it was very significant for legitimizing the project locally and for notifying a large sector of the health care infrastructure of the benefits and limitations of the FC. In this presentation, the project was presented as targeting women in the town, particularly for the prevention of infections, including HIV, as well as unintended pregnancy, but did not specifically mention women working in the sex industry. Subsequent ethnographic interviews with pharmacists and providers after this session indicated their recognition of the research staff and willingness to provide information about FC, but varying degrees of understanding of the project goals.

To implement the site-based component of our intervention, outreach staff entered each establishment and negotiated with the owner to allow them to sit with all women present at the site to provide the intervention to them as a group, preferably in an area away from public view in order to increase women’s ability to focus on the activity. Establishment owners were also invited and encouraged to participate or observe. Ethnographic observations and subsequent in-depth interviews of women and establishment owners suggested the critical importance of the owners’ support for prevention activities within their sites.

However, dynamics and activities within the site when outreach workers arrived to conduct the intervention sometimes required additional effort and creative approaches to get and maintain women’s attention in order to complete the protocol, as illustrated by the following case description excerpted from the ethnographers intervention observations:

When we entered this (hair parlor) establishment for the initial intervention session, nine women and the establishment owner were present. One woman was watching TV, one reading the paper, two playing cards with the boss, one washing another’s hair, and two laying down on a bed in back. They greeted us, but all continued with their activities. The outreach workers decided to conduct intervention in the main parlor area, instead of trying to move all or a few women to a back room. However, the women’s attention was very fragmented. No one moved or stopped whatever activity they were engaged in. The boss had no protest to the demonstration, but offered no support in focusing the women’s attention. After outreach workers’ repeated unsuccessful attempts to get the group’s attention, they just handed out flip-books [the outreach workers’ intervention field manuals] to a few women and started talking. A few women took the books and began looking through them, but didn’t seem to listen to or watch instructions. Eventually the boss agreed to handle the FC, after a couple of requests for her to do so; then she tried to insert it in the [plastic] model. Women watched her try it, though no others agreed to try themselves. But after trying to insert it in model, the boss seemed more interested and attempted three more separate times. Two girls who had previously been occupied with hair washing and cards then started paying more attention. So YW [an outreach worker] began the demonstration again just for the two of them, seated on parlor chairs. As she talked, she turned the page in the flip-book for one, and the other girl followed along. The girls laughed at a few points and seemed a little shy, but paid attention. Before leaving, the outreach workers handed out FC to the women and placed about eight on top of the TV.

Ethnographers attended many of these sessions to document the women’s and establishment owners’ reactions and factors that interrupted or modified the staff’s ability to complete the intervention protocol (such as arrival of clients, blaring television, intensive majiang or card games). Outreach staff documented the number of women present, compared to the number working at the establishment, and planned subsequent visits to reach any women not present and provide additional support and follow-up troubleshooting for all women at the establishment. The goal to reach at least 80% of the women in each establishment with the full intervention program and to conduct at least one follow-up session at each site by the end of the six months of intensive intervention in the community was achieved in 11 out of 12 establishments in FS and 12 out of 15 establishments in YF. The accumulated number of women who received intervention over the total number of women working in the establishments at the time of the 6-month survey was 106% (including women who had entered the establishments after the program was initiated).

Despite this success, use of local health educators to conduct outreach and implement an intervention trial in their community setting presented some unique challenges, both initially and over time in the attempt to sustain the prevention effort. One issue was the problem of maintaining boundaries between their research responsibilities and their everyday lives. The following excerpt from one of the ethnographer’s field observations poignantly illustrates the problem:

I [the ethnographer] encountered an interesting event one hot summer day in YF. That afternoon, YW, YZ [two local project outreach workers] and I went to an establishment to do basic intervention. It was hard to organize the women to participate in a group, so YW decided to provide the FC intervention individually. After completing the intervention, YW opened the door to go out, when she bumped into a familiar person, namely, her primary school teacher, as he was entering the establishment. YW said later, she really wanted to draw back her feet and close the door quietly; unfortunately, there was not enough time to do so. YW said hi to her teacher. The man immediately went out and explained awkwardly why he had come here. He said that he had not felt very well in his neck and wanted to have a massage here. But he decided not to do it now. YW introduced me to her teacher, and at the same time she stepped on my foot with her foot to hint to me. This is real community!

This excerpt illustrates the delicate efforts local staff must make to protect the reputation of people encountered in the course of conducting research related activities for local HIV prevention. They must do so because they will continue to live and work in the study community even after the project is completed.

A second issue local staff faced associated with long-term implementation of the community intervention was the challenge of keeping the prevention program interesting and fresh. After staff had delivered the basic package to all or nearly all sex-work establishments in the town and conducted at least one follow-up visit, the women in the establishment often resisted subsequent and ongoing outreach or dismissed it as unnecessary, particularly in sites where the FC was unpopular. However, regular turn-over of women in the establishments and the complex problems of initial FC insertion and troubleshooting indicated the need for repeated visits over time. Staff became concerned about their ability to find creative ways to continue or expand their work, and were bothered themselves by the repetitiveness of the message and outreach activities. They did, however, find ways to incorporate women’s feedback into their intervention activities over time, for example by building answers to their common questions into the standard protocol. Nevertheless, refreshing the intervention messages and methods remains a challenge for long-term sustainability of the effort in each town.

Handling Ethical Challenges in the Field

During the course of developing and conducting the research and intervention activities with this vulnerable population, the project consortium faced and addressed several ethical challenges. A primary concern was balancing the need to document sensitive data on the dynamics of the sex industry using rigorous and systematic research methods with the need to protect the identities and security of women in the sex-work establishments. In these towns, the majority of women had limited long-term obligations to the establishment owners, and could, and often did, move from place to place based on reputation of the environment in different establishments or other dynamics affecting their standard of living, mobility, and ability to earn income. In many establishments, the owners provide food, living space, and protection in addition to organizing access to clients. Relationships between owners and women workers ranged from fairly hierarchical, with the owner maintaining basic rules about women’s daily routines, cost of sex services, etc., to a surrogate “family” arrangement in which relatively young women (late teens and early twenties) referred to female establishment owners as “mama” and to the other women in the establishment as “sisters,” or to a loose conglomerate of independent women in a boarding house responsible to the “boss” only for monthly rent. Given the illegal nature of prostitution in China and the tenuous status of these establishments, establishment owners were concerned about the project attracting attention of the local authorities and provoking “trouble” (e.g., fines). For this reason, the local project staff needed to understand well and carefully handle their concerns, particularly in YF, where the intervention activities had stopped after 2001 and only resumed with this project. These concerns created more restrictive dynamics within establishments and owner restrictions on the women in YF. Thus, “do no harm” was interpreted to include refraining from activities that might jeopardize supportive ties between establishment owners and women. Local staff guided ethnographers in protocols they also followed in deciding when to enter establishments and under what circumstances to curtail project work because of activities taking place at the site.

Protection of anonymity was also of paramount importance and framed the project’s capacity to use certain research tracking methods and documentation procedures. Unique codes were used on surveys and in-depth interviews and codes were developed to refer to establishments in field notes and on community maps. Data sharing was of particular concern, given the multi-site nature of the study (townships, county, province, and investigators in Beijing and the U.S.), requiring the need to find secure ways to transport and pass data via internet or other protected and encrypted means.

A significant concern that arose during intervention was handling health related issues of women in the establishments. These took several forms, from personal questions about possible symptoms of sexually transmitted infections and misunderstanding of anatomy, to problems specifically related to use of the FC. The hiring of health care providers as outreach workers to implement the intervention in the establishments was extremely effective for addressing questions women raised regarding their health and understanding of their bodies, particularly in relation to birth control, STD/HIV prevention, and FC use. However, outreach staff had significantly varying degrees of experience. The younger full time staff, who were more often in the field, were less able to handle many of the more complex medical concerns women raised. They had to refer women to the township hospital or to more experienced staff to address those questions. Also, in one town, a woman experienced an adverse event while using the FC in a sexual encounter that lasted 40 minutes, resulting in significant abrasion from the inner and outer rings. She reported the incident to intervention staff after having sought antibiotics on her own and having stopped work for three days. Staff followed up with her by checking in several times over the next several weeks, though she refused further medical intervention. Such events during the course of promoting a new product, even one fully tested for safety and used correctly, can create significant dilemmas for local study staff and researchers.

Ethnographers also were frequently asked questions about medical concerns and proper FC use. While they deferred medical questions to the health provider staff, deciding how much information to provide on proper FC use, the purview of project intervention staff, was more challenging. In some cases, ethnographers felt compelled to provide correct information on FC use in order to maintain women’s trust and prevent inadvertent misuse or other risks. Thus, maintaining research “boundaries” for staff in the field was sometimes difficult. Yet, such dilemmas were minimized by the collaboration among research and intervention staff in determining the most ethical and protective response to these issues in the field that were suitable to the context of the study and local conditions.

SUMMARY OF LESSONS LEARNED

The following are key lessons our international research team has learned through the process of developing and conducting this participatory community-based study to test a multilevel HIV prevention intervention.

Sharing ownership of responsibilities and benefits of the project, including grant resources, data, products of the research like curricula, authorship of publications, and dissemination materials, is critical to the long-term success of the community/research collaboration.

Partnership between researchers and key stakeholders from local communities to develop and test HIV prevention interventions enhances the feasibility and cultural congruence of the prevention effort, and increases the likelihood of continued implementation after the research endeavor has concluded.

Organization of sex workers themselves in an effort to build prevention efforts, e.g., to promote FC or other woman-initiated prevention options, is still very difficult in a context in which there is little cultural or political precedent for this kind of activity around public health (Zhang et al., 2008), even more so in rural settings. It will require a longer-term and more sustained effort than the 18 months of project activities in these townships to build support and a different orientation among local people from an expectation of reliance almost exclusively on government-based efforts for public health education, promotion, and intervention. However, one of the values of community-based research is the potential to build ties and channels of communication between researchers, community organizations and community members to lay this foundation.

To further increase the feasibility, cultural congruence, effectiveness, and sustainability of prevention efforts in real-world community settings, it is necessary to build on what local people do routinely, such as their mission to provide public health education and services, while increasing their capacity to expand their repertoire and enhance rigor in applying best scientific knowledge to intervention designs and methods. However, as often happens in intervention studies, the limited period of project activity in each study site (18 months) allowed us insufficient time for repeated and extended training needed to substantially expand local staff knowledge and their deep understanding of health, social, and behavioral issues that could greatly enhance their ability to do this intervention. Nevertheless, more collaboration between community providers and researchers will substantially improve community capacity over time.

-

Community/research collaborative problem solving facilitates handling challenges for local community staff to follow research protocols while managing complex community relationships. This is particularly important for:

assisting them to handle delicate research-generated tensions, such as potential exposure of community members’ illicit behaviors, adverse events participants experience, and distress or discomfort associated with research participation, and

renewing and refreshing the intervention content and implementation processes to address the problem of sustainability.

Collaborative problem solving with local community staff also assists researchers to quickly resolve methodological problems in the field and to ensure research conduct is acceptable by local social and cultural standards.

Strong research/community cooperation, shared research responsibilities, and complementary roles facilitate the team’s ability to conduct ethical research, minimize adverse events, ensure informed consent, and resolve ethical dilemmas in the field, including participant concerns about engaging in research.

CONCLUSION

Community/research partnerships in collaborative and participatory endeavors enhance the ability to develop, test, and disseminate complex, multi-level community interventions to promote HIV prevention using new or well-established technologies and behavioral interventions. Lessons we learned from the first round of research and intervention activities of our China/U.S. Women’s Health Project demonstrate the value of incorporating local resources and engaging community stakeholders in the effort to implement and test HIV prevention in sex-work establishments. Our experiences also flag the complexity of these collaborative efforts and the challenges of maintaining scientific rigor while responding appropriately to local conditions, and protecting the reputations of local staff by behaving in culturally appropriate ways and maintaining the highest standards of ethical research conduct.

Significant in this complex and delicate process is recognition of the importance of shared capacity building. Researchers must be open to listening to and learning from local staff and other community members about what is important and acceptable in research practice. Research design and practice must allow for the possibility that local conditions and specific events might require redirection or modification of protocols, such as techniques used to access research participants and strategies to engage local resources for the success of the intervention implementation process. Likewise, researchers can assist local staff, who are likely to remain on location after the study is completed, to find the delicate balance between research rigor and local expectations of their behavior and commitment. Though this shared experience and commitment, HIV prevention can advance to further reduce the impact of the epidemic.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express our deep appreciation for the tireless efforts of the county level and township level health educators and care providers who staffed and implemented the intervention of the China/U.S. Women’s Health Project. We also wish to thank Maryann Abbott of the Institute for Community Research for sharing her experiences with directing a similar study in Hartford, Connecticut, and Dr. Jingmei Jiang from Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences/Peking Union Medical College, for guidance on survey design and statistical methods. This study was funded with a grant from the National Institute on Mental Health (R01 MH077541).

Footnotes

“Microbicide/Female Condom Acceptability for Sex Workers in China,” National Institute on Mental Health (NIMH) Fogarty International Center (R03TW006302: 2003–2006; PI: Weeks; Co-PI: Liao); and “High-risk Establishments and Women’s HIV Prevention in Southern China,” NIMH (R01 MH077541, 2007–2012; PI: Weeks; Co-PI: Liao).

Contributor Information

Margaret R. Weeks, Institute for Community Research, 2 Hartford Sq. W., Ste. 100, Hartford, CT 06106

Susu Liao, Department of Epidemiology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Fei Li, Department of Epidemiology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Jianghong Li, Institute for Community Research, Hartford, Connecticut

Jennifer Dunn, Institute for Community Research, Hartford, Connecticut

Bin He, Hainan Center for Disease Prevention and Control, HIV/AIDS Division, Haikou, Hainan, China

Qiya He, Hainan Center for Disease Prevention and Control, HIV/AIDS Division, Haikou, Hainan, China

Weiping Feng, Chengmai County Center for Disease Prevention and Control, HIV/AIDS Division, Jinjiang, Hainan, China.

Yanhong Wang, Department of Epidemiology, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

References

- Altman DG. Sustaining interventions in community systems: On the relationship between researchers and communities. Health Psychology. 1995;14(6):526–536. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beeker C, Guenther-Grey C, Raj A. Community empowerment paradigm drift and the primary prevention of HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 1998;46(7):831–842. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown ER. Community action for health promotion: A strategy to empower individuals and communities. International Journal of Health Services. 1991;21:441–456. doi: 10.2190/AKCP-L5A4-MXXQ-DW9K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, MacPhail C. Peer education, gender and the development of critical consciousness: participatory HIV prevention by South African youth. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(2):331–345. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00289-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Choe MK, Chen S, Zhang S. The effects of individual- and community-level knowledge, beliefs, and fear on stigmatization of people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Care. 2007;19(5):666–673. doi: 10.1080/09540120600988517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XS, Yin YP, Mabey D, Peeling RW, Zhou H, Jiang W, et al. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infections among women from different settings in China: Implications for STD surveillance. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;82(4):283–284. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZQ, Zhang GC, Gong XD, Lin C, Gao X, Liang GJ, et al. Syphilis in China: Results of a national surveillance programme. Lancet. 2007;369:132–138. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60074-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YM, Li ZH, Wang XM, Wang SY, Hu LZ, Xie YY, et al. Introductory study on female condom use among sex workers in China. Contraception. 2002;66(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Ministry of Health. A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China. Beijing: Chinese Minsitry of Health; 2007. Chinese State Council AIDS Working Committee Office and UN Theme Group on AIDS in China. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Ministry of Health and WHO. A Joint Assessment of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Treatment and Care in China. Beijing: State Council AIDS Committee Office; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Henderson GE, Aiello P, Zheng HY. Successful eradication of sexually transmitted diseases in the People’s Republic of China: Implications for the 21st century. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;174(supp 2):S223–S229. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.supplement_2.s223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Ping G, Fox K, Henderson GE. Sexually transmitted diseases in the People’s Republic of China in Y2K: Back to the future. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2000;27(3):143–145. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200003000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury J, Cocking C, Beale J, Hanson C, Rapley F. The phenomenology of empowerment in collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2005;44(Pt 3):309–328. doi: 10.1348/014466604X18523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J, Stanek K. Cross-cultural considerations in the conduct of community-based participatory research. Family & Community Health. 2007;30(1):42–49. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller CM, Galea S, Caceres W, Blaney S, Sisco S, Vlahov D. Multilevel community-based intervention to increase access to sterile syringes among injection drug users through pharmacy sales in New York City. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):117–124. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.069591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil VE, Wang MS, Anderson AF, Lin GM, Wu ZO. Prostitutes, prostitution and STD/HIV transmission in mainland China. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42(1):141–152. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00064-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Li X. Behavioral studies of female sex workers in China: a literature review and recommendation for future research. AIDS & Behavior. 2008a;12(4):623–636. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Y, Li X. HIV/AIDS behavioral interventions in China: A literature review and recommendations for future research. AIDS Behavior. 2008b doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9483-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Liu H, Li X, Stanton B, Chen X. HIV-related sexual behaviour among migrants and non-migrants in a rural area of China: role of rural-to-urban migration. Public Health. 2006;120(4):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Checkoway B, Schulz A, Zimmerman M. Health education and community empowerment: conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational, and community control. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):149–170. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Satcher D, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jana S, Basu I, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Newman PA. The Sonagachi Project: a sustainable community intervention program. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2004;16(5):405–414. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.5.405.48734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose B, Freidman S, Neaigus A, Curtis R, Sufian M, Stepherson B, et al. Collective organization of injecting drug users and the struggle against AIDS. In: Rhodes F, Hartnoll R, editors. AIDS, Drugs and Prevention: Perspectives on Individual and Community Action. London: Routledge; 1996. pp. 216–233. [Google Scholar]

- Labonte R. Health promotion and empowerment: Reflections on professional practice. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):253–268. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SS. HIV in China: Epidemiology and risk factors. AIDS. 1998;12(suppl B):S19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SS, He QY, Choi KH, Hudes ES, Liao JF, Wang XC, et al. Working to prevent HIV/STIs among women in the sex industry in a rural town of Hainan, China. AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10:S35–S45. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SS, Schensul JJ, Wolffers I. Sex-related health risks and implications for interventions with hospitality women in Hainan, China. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2003;15(2):109–121. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.3.109.23834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus MT, Walker T, Swint JM, Smith BP, Brown C, Busen N, et al. Community-based participatory research to prevent substance abuse and HIV/AIDS in African-American adolescents. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2004;18(4):347–359. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M. Chinese AIDS experts call for more education to halt HIV epidemic. The Lancet. 1999;354(9192):1800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)70572-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy HV, Malow R, Edwards RW, Thurland A, Rosenberg R. A strategy for improving community effectiveness of HIV/AIDS intervention design: The Community Readiness model in the Caribbean. Substance Use & Misuse. 2007;42:1579–1592. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Improving health through community organization and community building. In: Glanz K, Rimer FM, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. Vol. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997. pp. 241–269. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamathi A, Koniak-Griffin D, Tallen L, Gonzalez-Figueroa E, Levson L, Mosley Y, et al. Use of community-based participatory research in preparing low income and homeless minority populations for future HIV vaccines. Journal of Interprofessional Care. 2004;18(4):369–380. doi: 10.1080/13561820400011735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes SD, Hergenrather KC, Montano J, Remnitz IM, Arceo R, Bloom FR, et al. Using community-based participatory research to develop an intervention to reduce HIV and STD infections among Latino men. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2006;18(5):375–389. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Hartnoll R. AIDS, drugs and prevention: Perspectives on individual and community action. London: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson A, Minkler M. New health promotion movement: A critical examination. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(3):295–312. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero L, Wallerstein N, Lucero J, Fredine HG, Keefe J, O’Connell J. Woman to Woman: Coming together for positive change--Using empowerment and popular education to prevent HIV in women. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2006;18(5):390–405. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Duan N. Next generation of preventive interventions. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2003;42(5):518–526. doi: 10.1097/01.CHI.0000046836.90931.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schensul J. Strengthening communities through research partnerships for social change. In: Hyland S, editor. Community building in the twenty-first century. 1. Santa Fe: School of American Research; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JJ. Community Based Risk Prevention with Urban Youth. School Psychology Review. 1998;27(2):233–245. [Google Scholar]

- Schensul JJ. Sustainability in HIV prevention research. In: Pequenot W, editor. Context, Culture, and Collaboration in AIDS Interventions: Ecological Ideas for Enhancing Community Impact. Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Singer M, Weeks MR. The Hartford model of AIDS practice/research collaboration. In: Trickett EJ, Pequegnat W, editors. Community Interventions and AIDS. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Thurman PJ, Vernon IS, Plested B. Advancing HIV/AIDS prevention among American Indians through capacity building and the Community Readiness model. Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2007;(supplement):S49–S54. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200701001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ. Community interventions and HIV/AIDS: Affecting the community context. In: Trickett EJ, Pequegnat W, editors. Community Interventions and AIDS. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Trickett EJ. Multilevel community-based culturally situated interventions and community impact: An ecological perspective. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43(3/4) doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS/WHO. Epidemiological Fact Sheets on HIV/AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. China: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- van Ameijden EJC, van den Hoek JAR, van Haastrecht HJA, Coutinho RA. The harm reduction approach and risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seroconversion in injecting drug users, Amsterdam. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992;136:236–243. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Hoek A, Yuliang F, Dukers NH, Zhiheng C, Jiangting F, Lina Z, et al. High prevalence of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases among sex workers in China: potential for fast spread of HIV. AIDS. 2001;15(6):753–759. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200104130-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jiang B, Siegal H, Falck R, Carlson R. Level of AIDS and HIV knowledge and sexual practices among sexually transmitted disease patients in China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2001;28(3):171–175. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200103000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Overview of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, scientific research and government responses in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S3–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304690.24390.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liao SS, Weeks MR, Jiang JM, Abbott M, Zhou YJ, et al. Acceptability of hypothetical microbicides among women in sex establishments in rural areas in Southern China. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35(1):102–110. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31814b8546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks MR, Convey M, Dickson-Gomez J, Li JH, Radda K, Martinez M, et al. Changing drug users’ risk environments: Peer Health Advocates as multi-level community change agents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43(3/4) doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks MR, Liao SS, Abbott M, He B, Zhou YJ, Jiang JM, et al. Opportunities for woman-initiated HIV prevention methods among female sex workers in Southern China. Journal of Sex Research. 2007;44(2):190–201. doi: 10.1080/00224490701263843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Xia G. Gender, work, and HIV risk: determinants of risky sexual behavior among female entertainment workers in China. AIDS Education & Prevention. 2006;18(4):333–347. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang KL, Detals R, Liao SS, Cohen M, Yu DB. China’s HIV/AIDS Epidemic: continuing challenge. Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1791–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang KL, Ma SJ. Epidemiology of HIV in China. British Medical Journal. 2002;324(7341):803–804. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7341.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]