Synopsis

The management of hypnotic discontinuation following regular and prolonged use may be a challenging task for patients and clinicians alike. Current evidence suggests that a stepped-care approach may be a cost-effective approach to assist patients in tapering hypnotics. This approach may involve simple information about the need to discontinue medication, implementation of a supervised and systematic tapering schedule, with or without professional guidance, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Research evidence shows that this approach appears promising; further research is however necessary to identify treatment and individual characteristics associated with better outcome.

Keywords: Insomnia, Benzodiazepines, Hypnotic Medications, Discontinuation, Stepped-care approach, Sleep Disorder

Introduction

Pharmacological approaches are the most widely used treatment options for the management of chronic insomnia [1, 2]. Hypnotic medications are indicated and efficacious for treating situational insomnia [3]. However, despite clear guidelines suggesting that hypnotic drug use should be time-limited [3], a considerable proportion of individuals with insomnia use hypnotics on a nightly basis for prolonged periods of time, often reaching many years. Furthermore, many individuals will continue reporting significant sleep disturbances in spite of an appropriate therapeutic use of hypnotic medications [4]. In clinical practice, clinicians treating patients with chronic complaints of sleep difficulties are often faced with the dilemma of hypnotic discontinuation versus continued prescription. While long-term use of hypnotics for the management of chronic insomnia remains controversial, information regarding hypnotic discontinuation is still scarce.

This article discusses different aspects of long-term hypnotic use in chronic insomnia, with a focus on the management of hypnotic withdrawal. Issues such as preoccupation with long-term use, factors associated with the development of hypnotic-dependent insomnia and step-by-step treatment strategies to help discontinuation of hypnotic use are presented.

1. Long-term Hypnotic Use

1.1 Preoccupation with long-term use

Chronic insomnia has been consistently associated with significant reduced quality of life, higher risks of depression and increased health care services utilization [5]. Different drug classes are routinely used for the management of insomnia. Those include benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), selective melatonin receptor agonists, and sedating antidepressants. The present article will focus on BzRA hypnotics only. This drug class includes two groups of prescription hypnotics: the classical benzodiazepines (BZDs; e.g. temazepam, triazolam, flurazepam, quazepam, estazolam) and the more recently introduced drugs, that have a nonbenzodiazepine structure but act at the benzodiazepine receptor sites (e.g. zaleplon, zolpidem, eszopiclone.). While classical BZDs have been the drug class of choice for the treatment of insomnia for many years, nonbenzodiazepine hypnotics are now the indicated drug class for insomnia pharmacotherapy [6]. The main advantages newer nonbenzodiazepines present over the traditional BZDs are their faster elimination rate and relative alpha-1 binding selectivity, which significantly decrease some of the side-effects associated with the classical BZDs [7]. Unfortunately, they are not free from side-effects or adverse effects and, like their predecessors, have been associated with risks of dependence, higher risks of accident and falls, and cognitive disturbances, which again calls for increased caution when they are prescribed to some specific groups of patients [7-10]. Furthermore, the risks associated with their prolonged daily use are still not very well documented and well-designed studies examining those risks are warranted. There is also very limited evidence in the literature regarding their sustained long-term efficacy over several years [11-13]. Another important limitation associated with hypnotic use for chronic insomnia is that treatment cessation is often associated with a return of sleep difficulties or with rebound insomnia, an exacerbation of the original insomnia severity. Recrudescence of insomnia symptoms after hypnotic discontinuation has been hypothesized to play a role in the development of hypnotic-dependent insomnia [14]. For these reasons, long-term use of hypnotics for the management of insomnia remains controversial [3, 15].

1.2. Factors associated with the development of hypnotic-dependent insomnia

Approximately 5% to 7% of the adult population uses prescribed sleep-promoting medications during the course of a year [1, 2, 16]. For most people, medication is used for a limited period of time (as in acute stress). For many patients, however, the pattern of use is occasional but recurrent and for others, medication is used on a regular and chronic basis. In most cases, sleep medication is initiated during acute episodes of insomnia due to psychological stress, medical illness, or important schedule changes associated with jet lag or shift work. It may also be initiated in the context of chronic insomnia, when a person can no longer cope with the daytime impairments produced by recurring sleep disturbances.

Although the initial intent for both patients and prescribing physicians is to use medication for the shortest possible duration (i.e., a few nights), some patients continue using it over prolonged periods of time, either because of persistent sleep disturbances or, on a prophylactic basis, in an attempt to prevent insomnia. Several psychological, behavioral, and physiological factors contribute to maintain this pattern of habitual and chronic use.

With nightly use, tolerance is likely to develop with most hypnotic drugs. To maintain efficacy, it is sometimes necessary to increase dosage but, when the maximum safe dosage is reached, the person is caught in a vicious cycle. While the medication may have lost its hypnotic properties, attempts at discontinuing it is likely to produce withdrawal symptoms, including rebound insomnia. Rebound insomnia is usually temporary but may persist for several nights in some patients. In any case, the experience of rebound insomnia heightens the patient's anticipatory anxiety and reinforces the belief that he or she cannot sleep without medication. This chain reaction is quite powerful in prompting the patient to resume medication use and hence the vicious cycle of hypnotic-dependent insomnia is perpetuated.

Conditioning factors are also involved in chronic hypnotic use. For instance, by alleviating an aversive state (i.e., sleeplessness), hypnotic drugs quickly acquire powerful reinforcing properties; as such, the pill-taking behavior becomes negatively reinforced. Although sleep medications are usually prescribed on an “as needed” basis in order to prevent tolerance, this intermittent schedule can also be quite powerful in maintaining the pill-taking behavior. A form of reverse sleep state misperception can also perpetuate hypnotic use. In general, unmedicated insomniacs tend to overestimate the time spent awake at night and underestimate total sleep time; conversely, medicated insomniacs (with BZD hypnotics) have a reversed sleep state misperception in that they overestimate sleep time and underestimate wake time while on medication and, upon withdrawal, become acutely aware of their sleep disturbances, a phenomenon that might very well be attributed to the amnestic properties of benzodiazepines [17]. This might also explain why so many individuals continue using benzodiazepines, despite objective evidence that their sleep is impaired [18].

In most cases of chronic hypnotic use, patients do not abuse their medications, in the sense of escalating and exceeding the recommended dosages; rather, they remain on the same therapeutic dose without escalation but continue using it for much longer periods than was initially intended and are unable to discontinue use. This self-contained and habitual pattern of drug use is still likely to lead to dependency, although this type of dependency is often more psychological than physiologically-based.

Although there is no specific profile that characterizes long-term hypnotic users, chronic use is more common among older adults, women, and persons with more severe insomnia, higher psychological distress and more health problems [10,19, 20]. Lack of standard monitoring and follow ups of patients may also contribute to long-term use. On the other hand, some patients may place undue pressure on their family physicians requesting sleep medications. Prescribing medication is certainly less time-consuming [20], at least in the short-term, than providing behavioral recommendations for insomnia.

2. Hypnotic Discontinuation

Side-effects and risks associated with long-term use are often major reasons for encouraging patients to discontinue use despite their perception of continued efficacy. Enduring insomnia symptoms in spite of appropriate therapeutic use may also warrant discontinuation and the need to seek other types of treatment. Other reasons may come from the patients themselves. By discontinuing hypnotic use, some patients report wanting to recover a more natural sleep, others will evoke wanting to feel less dependent on hypnotics or simply feel they have been using hypnotics for too long and fear long-term effects. On the other hand, risks and benefits associated with long-term hypnotic use need to be weighted against those associated with untreated or self-treated insomnia [6] and availability of nonpharmacological approaches.

Discontinuing hypnotic medications can pose quite a challenge to some individuals, especially for long-term chronic users [17, 21, 22]. Several physiological (withdrawal symptoms) and psychological factors (anticipatory anxiety, fear of rebound insomnia, personality) have been shown to influence discontinuation [9, 23, 24]. However, it remains difficult to predict who will encounter withdrawal problems and factors predicting relapse are still poorly understood.

Difficulties encountered during hypnotic withdrawal and high relapse rate following discontinuation have prompted the development of clinical treatment strategies to help patients discontinue long-term use of hypnotics. These interventions vary in their format and degree of specialized care they require, ranging from advice given during routine medical consultations to formal cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) delivered in the context of weekly therapy sessions by behavioral sleep medicine specialists.

2.1 Stepped-care approach to hypnotic discontinuation

Russell and Lader [25] have proposed a stepped-care approach to manage discontinuation of long-term therapeutic use of BZDs (taken as anxiolytics or hypnotics). This approach tailors the amount of intervention according to patients' needs. According to this model, the first step is to give simple advice -in the form of a letter or meeting to a large group of individuals regarding medication discontinuation- and, if this fails, to gradually augment treatment from formal supervised medication tapering to specialized care, including different augmentation strategies such as cognitive behavior therapy. Results of studies that have examined the outcome of this first-step intervention suggest that a simple information letter may be sufficient for some patients in helping them stop their hypnotic use. For example, in their study examining BZD taper with or without group cognitive-behavior therapy, Oude Voshaar and colleagues [26] reported that a significant portion (14 %; 285/2004) of the sample, who had received a personalized letter from their family physician advising them to discontinue BZD use, effectively discontinued use without more formal help. Using a similar first-step strategy, Gorgels and colleagues [27] observed a similar proportion of individuals in their sample who discontinued BZD use (15-28%) after having been advised to do so by their family physician.

For those who may need more intensive and structured guidance in discontinuing their medication, a next step may be to implement a systematic supervised tapering program alone. Many individuals, who had previously unsuccessfully attempted to stop their hypnotic use, seem to benefit from a supervised, structured, and goal-oriented approach [26, 27]. In a study comparing a taper alone program to taper combined with CBT for insomnia [28], the proportion of participants stopping their hypnotic use was greater in the condition receiving the combined intervention (85%), however, a significant proportion of participants (48%) succeeded in discontinuing hypnotic use in the taper program alone condition. Furthermore, when examining long-term outcome after discontinuation, those participants fared as well regarding abstinence as those who received the combined intervention [29].

2.2 Systematic discontinuation procedures

There is clear evidence that hypnotic drugs should be discontinued gradually because abrupt discontinuation is associated with higher risks of withdrawal symptoms and health complications [30, 31]. However, there are no empirically validated guidelines regarding the optimal rate of tapering. A regimen that has been frequently used in hypnotic reduction studies is to decrease initial dosage by 25% slices weekly or every other week until the smallest minimal dosage is reached [23, 28, 32]. It is important to keep in mind that taper pace may need to be adjusted according to the presence of withdrawal symptoms and anticipatory anxiety; it can also be slowed if the person finds it too difficult to cope or feels unable to meet the reduction goal [28, 33]. Nevertheless, taper duration should be time-limited as much as possible in order to mobilize the person's efforts over a restricted period [34]. Ideally, withdrawal should be supervised by a health care professional and regular follow ups should be scheduled during discontinuation. The taper process should be carefully planned with the patient and individualized to take into account hypnotic type, dosage, frequency and length of use, and psychological factors such as motivation, anxiety level and anticipations [24, 33, 35-37]. A step-by-step hypnotic discontinuation program and taper schedule is proposed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Step-by-Step Hypnotic Discontinuation Program in Chronic Long-Term Users

| Steps to Taper Hypnotic Medications | Procedure |

|---|---|

| Plan the whole process: Physician and patient plan the discontinuation process over the following weeks in a collaborative fashion. | Assess regular daily dosage used. Stabilize dosage if needed. When patients use more than one hypnotic, stabilize dosage on only one drug (1 to 2 weeks). Estimate total number of weeks required to complete withdrawal if medication is decreased by 25% every other week. A written plan can be given out to the patient as a worksheet to increase adherence. |

| Gradual taper | Decrease daily intake by 25% of initial dosage for two weeks. Repeat this step, until the smallest dosage is reached. |

| Hypnotic-free nights are gradually introduced | In the first week, it may be best to pre-select nights associated with apprehension regarding next day's functioning. Increase number of those hypnotic-free nights in the second week. |

| Use on pre-determined nights | Pre-select nights regardless of next day's activities or anticipations. Strongly encourage observance to the initial plan, give rationale. |

| Complete discontinuation. Plan follow-ups to assess maintenance and prevent relapse | Assess patient's anxiety regarding complete cessation and go over coping strategies. Remind the patient that the minimal dosage used in the last weeks likely had few objective effects on their sleep. |

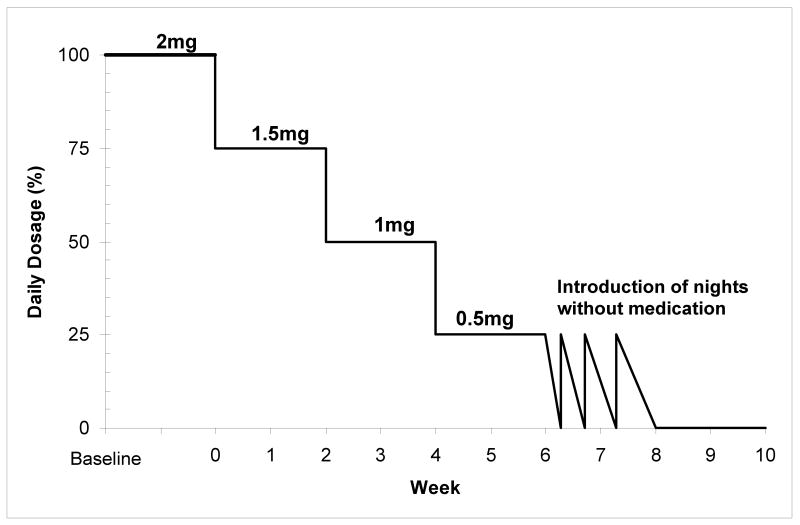

According to this procedure, the first step is to carefully plan the discontinuation strategy with the patient and to set clear reduction goals. For individuals using more than one hypnotic drug, the first step is to stabilize use on one compound only, preferably the drug with the longer half-life. Another strategy that has been used in withdrawal studies is to switch the original short-acting drug to a longer acting drug (diazepam for example) in order to minimize withdrawal symptoms. However, there is little evidence in the literature showing that this strategy is associated with better outcomes. Broad anchor points can be set a priori, for example, to have reduced initial dosage by 25% at the second week, 50% by the fourth week and 100% by the tenth week. At the end of taper, when the smallest dosage is reached, medication-free nights are gradually introduced. At first, these “drug-holidays” can be planned on nights when the person feels it will be easier for them to refrain from taking sleep medication (e.g. a week-end night, when there is no obligation the following day); then, pre-selected nights, on which the hypnotic will be used regardless of whether the person feels they need it or not, will be introduced. This last step may prevent the use of a medication on more “difficult” nights and, at the opposite, medication may be used on a night when there is no need for it. This strategy is used to weaken the association between lying in bed not sleeping and the pill taking behavior [21]. An example of this taper strategy is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Individualized Taper program example: Lorazepam 2 mg.

Some individuals may apprehend the final step of complete cessation and worry over the potential consequences of hypnotic withdrawal on their sleep. It may then be useful to remind them that the very small quantity of medication used in the final weeks of discontinuation was probably producing very little benefits on their sleep. Such apprehensions and worry about complete cessation should be addressed directly as they may be very well contribute to residual sleep disturbances after hypnotic discontinuation [19, 21].

2.3 Use of CBT during hypnotic discontinuation

There is now solid evidence that CBT is efficacious for treating insomnia, produces sustained benefits over time and, for many individuals, CBT is recognized as the treatment of choice [3, 38]. Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) for insomnia is often necessary to help chronic hypnotic users learn new skills to manage their sleep difficulties. The goals of using CBT during hypnotic discontinuation are two-folds: to help reduce hypnotic use per se, and to improve sleep during and post-withdrawal. CBT for insomnia is a multidimensional, time-limited, and sleep-focused approach including several strategies targeting maintenance factors of insomnia. Strategies most commonly used are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (CBT) for Insomnia

| Component | Aim | Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep Restriction | Consolidate sleep on a shorter period of time | Curtail time in bed to actual sleep time. Go to bed only when sleepy. Use the bed and bedroom only for sleep and sex. |

| Stimulus Control | Re-build the association between the bed and bedroom, and sleep | Get out of bed and bedroom if unable to fall asleep within 20 minutes. Arise at the same time every morning regardless of the amount of sleep obtained the previous night. Avoid napping. |

| Cognitive Therapy | Reduce cognitive activation at bedtime and during nocturnal awakenings Improve the management of daytime consequences of insomnia | Identify and challenge beliefs and attitudes that exacerbate insomnia, such as unrealistic expectations about sleep requirement, dramatization of the consequences of insomnia, erroneous beliefs about strategies to promote sleep, etc. |

| Sleep Hygiene Education | Reduce the impact of lifestyle and environmental factors on sleep disturbances | Review sleep hygiene principles about the effects of exercise, caffeine, alcohol, and environmental factors on sleep. |

The benefits of using cognitive and behavioral interventions to facilitate hypnotic taper and to help maintain abstinence among individuals with insomnia is supported by empirical evidence [19, 26, 28, 32, 39- 45]. For example, Lichstein and colleagues [39] showed that progressive relaxation during supervised gradual medication withdrawal lead to significant hypnotic reduction and that participants who received relaxation training reported higher sleep quality and efficiency and reduced withdrawal symptoms, compared to those who did not. Baillargeon and colleagues [40] compared two systematic taper programs, one was combined with multicomponent CBT and the other was not. Results showed a greater proportion of participants who had completely discontinued hypnotic medication in the group with CBT (77% versus 38%). A study by Morin and colleagues [28] showed similar results, with a greater proportion of drug-free participants in the group who received a systematic hypnotic taper program combined with CBT compared to the group receiving the taper alone (85% versus 48%). This study's results also showed greater subjective sleep improvements in the participants who discontinued sleep medication while undergoing CBT. Zavesicka and colleagues [32] have specifically examined the impact of discontinuing sleep medications during CBT on sleep quality and have shown that chronic hypnotic users may benefit to the same extent from this intervention, and maybe even more, than people with insomnia who did not use hypnotics. Their results showed that chronic users discontinuing hypnotic use showed greater sleep efficiency improvements after CBT compared to those who had received the same treatment, but had not previously resorted to pharmacological sleep aids. However, the study did not include a follow-up of participants and thus does not provide information about long-term outcomes.

Some of the studies examining the usefulness and efficacy of CBT for insomnia have included hypnotic users in their sample without addressing hypnotic discontinuation per se, or providing a structured taper program. Nevertheless, several of these studies report significant reductions in hypnotic dosage, frequency of use, or both [19, 46-47]. For example, Morgan and colleagues [19] examined the impact of CBT on hypnotic reduction without pairing it with a systematic taper intervention. Their results showed that CBT alone helps reduce hypnotic use and improve sleep quality, although the proportion of participants who no longer used hypnotics after six months was lower (33%) than reported in the previously cited studies. The authors suggested that this may in part be due to the fact that participants had not received explicit instructions to discontinue hypnotic use. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that a third of the sample discontinued sleep medications after having learned new ways to manage their sleep difficulties, without having been directly advised to do so. In their comparative study, Morin and colleagues [28] had also included a control group receiving CBT who did not receive any formal guidelines or recommendations to discontinue medication. Participants who expressed the wish to stop hypnotic use during the study were invited to consult their family physician. Results in this group showed that 54% of the sample had discontinued use by the end of the study. However, information as to which procedure they followed or which quantity of intervention they received regarding medication discontinuation was not systematically collected, thus limiting the possibility to further interpret these data. Long-term outcome after discontinuation were later analyzed in this sample [29] and the results showed that the participants from this group who had stopped their hypnotic use had significantly higher relapse rates than participants who had received the supervised taper program, either alone or combined with CBT. In a recent study, Soeffing and colleagues [4] examined insomnia treatment in older adults who were long-term chronic users of hypnotic medications and showed that even when patients kept their hypnotic use stable throughout the intervention, CBT was also associated with significant sleep improvements.

An important issue that often arises in clinical practice is about when to implement CBT in the context of hypnotic discontinuation. Should CBT be initiated before, at the same time, at any step during, or even after hypnotic discontinuation? Most discontinuation studies have implemented CBT and hypnotic discontinuation concurrently. For example, in the Morin and colleagues [28] and Belleville and colleagues [42] studies, the first intervention week included two appointments: a consultation with a physician, where the first reduction goal was set and instruction given to start taper the same night, and the first CBT session (either therapist-guided [28]; or self-help brochure [42]), providing information on sleep and introducing sleep restriction, was delivered. At week 2, the second reduction goal was set, and session 2 of CBT, introducing stimulus control strategies, was provided. At week 3, the third reduction goal was set while the third session of CBT was provided, and so on. This strategy has the advantage of introducing new CBT strategies to manage sleep while patients are progressively letting go of their hypnotics. However, a potential drawback of this combined strategy is the considerable amount of information and recommendations given to patients at the same time. For example, in the study comparing hypnotic discontinuation with and without self-help CBT [42], five participants in the CBT condition dropped out of the program. They all reported that hypnotic discontinuation and CBT guidelines were too difficult to follow. It is possible, however, that these patients may have needed direct therapist guidance. For some patients, it may be easier to introduce CBT before tapering or, on the contrary, begin taper for a few weeks, and then introduce CBT if sleep difficulties occur. In a small pilot study, Espie and colleagues [48] had found that patients who were withdrawn from medication early on in the behavioral treatment achieved better sleep outcomes than those withdrawn after the behavioral intervention.

In some cases, even if more clinical attention than a supervised taper program alone appears warranted, it may not be necessary to implement a full course of CBT (including 8-10 weekly sessions) delivered by a sleep specialist. It is possible that hypnotic discontinuation programs may be successful with fewer consultation visits (e.g., at week 1 and week 4) and a self-help format of CBT. In such a context, brief weekly (15-20 minutes) phone contacts with a therapist to discuss sleep difficulties and implementation of CBT strategies could be provided. This type of minimal intervention was examined recently and led to complete discontinuation of hypnotic use for two thirds of participants at post-treatment and about half at the 6-month follow-up [42]. A secondary analysis of these data indicated that individuals experiencing insomnia worsening, more withdrawal symptoms and psychological distress (e.g., anxiety or depressive symptoms), and lower self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in one's own ability to stop medication) during and after the discontinuation program were less likely to be drug-free at the end of the intervention as well as 6 months after [35]. These might be indications that more intensive and individualized therapeutic supervision may be warranted for these individuals.

Using a more intensive program (i.e., 10 weekly medical consultations with or without ten weekly 90-minute CBT group sessions) led to an average interval of 2.6- and 18.6-month interval before relapse, i.e. resuming regular use of hypnotics after the end of treatment, for individuals tapering their hypnotics with and without CBT [29]. Once again, higher insomnia severity and psychological distress were associated with shorter interval to relapse. These observations led to the suggestion that booster sessions might prove useful in preventing relapse, but this is yet to be empirically tested.

2.4 Clinical and practical considerations

Hypnotic discontinuation may require a good deal of adaptation for some patients, especially for long-term users with residual persistent insomnia symptoms who therefore need to learn new ways of managing their sleep difficulties. Aspects such as readiness to change and motivation [35], self-efficacy in being able to discontinue use or comply with the taper program [33] and anticipations [22, 28, 33 ] are important factors to assess prior to withdrawal. The person needs to be willing and ready to change their habitual way of coping with insomnia, and motivation should be intrinsic rather than result from pressure from a spouse or other family member. The latter is more likely to be associated with failure. Timing is also important; discontinuation of hypnotics in periods of acute stress or major life changes may be more difficult and waiting for a better timing may be prescribed. It is also important to define realistic goals for each individual; complete abstinence may not be desirable for all patients. For example, patients with very high anxiety levels may wish to discontinue their medication but their quality of life may be significantly reduced if their sleep worsens with drug discontinuation. Finally, contraindications to hypnotic withdrawal need to be very carefully assessed. For example, in patients with complex mental health problems (e.g., schizophrenia, manic-depressive disorder), a history of recurring depressive episodes or seizures, hypnotic discontinuation may provoke a relapse of the psychiatric problem and even worsen the patient's condition.

Summary and future directions

Observations stemming from different withdrawal studies suggest that a stepped-care approach to hypnotic discontinuation may be useful and cost-effective. In such an approach, long-term users would be first advised by their family practitioners on how to discontinue hypnotic use. If not able to taper off, or if experiencing a worsening of sleep or psychological distress in doing so, enrolment in a program with systematic interventions but minimal guidance such as a self-help approach, could be a next step. If this intervention appears to be insufficient to alleviate insomnia symptoms and distress, then patients could be referred to a behavioral sleep medicine specialist who would implement more intensive CBT involving weekly individual consultations. At the end of treatment, booster session could be planned in order to monitor and prevent relapse. A recent meta-analysis examining the success rate of different discontinuation strategies provide some evidence for the efficacy of stepped-care approaches to medication discontinuation [49]. Evidences suggest that a stepped-care approach, where the amount of intervention is progressively increased according to the needs of patients and according to their autonomy and distress levels in tapering off their medication, may be an interesting way to manage hypnotic discontinuation. However, much research remains necessary in order to tailor withdrawal programs according to patients' needs. At this time, factors such as treatment characteristics or individual characteristics of those who could most benefit from one or the other strategy-or of a combination of those- remain poorly understood.

Current evidence suggests that CBT may be a useful adjunct to systematic hypnotic discontinuation programs. Whether or not it helps reduce hypnotic use per se is still unclear, and could depend on themes and strategies discussed, but consistent favorable impacts of CBT on sleep quality have been repeatedly reported. Guidelines as to when and how to implement CBT during hypnotic taper are still scarce. Most programs start and run both hypnotic taper and CBT at the same time. Evidence regarding optimal sequencing of these interventions is very limited and future studies examining which combination is associated to better outcomes are necessary.

In conclusion, although the original intent is to prescribe hypnotics on a short time basis, some patients will use them for much longer periods than was initially intended and may be unable to discontinue their medication by themselves. Structured taper programs with or without augmentation strategies such as CBT appear promising in facilitating discontinuation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roehrs T, Roth T. Hypnotics prescription patterns in a large managed-care population. Sleep Med. 2004;5(5):463–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh JK. Pharmacologic management of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65 16:41–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference statement on Manifestations and Management of Chronic Insomnia in Adults; June 13-15, 2005; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sleep. 2005;28(9):1049–57. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soeffing JP, Lichstein KL, Nau S, et al. Psychological treatment of insomnia in hypnotic-dependent older adults. Sleep Med. 2008;9:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Prevalence, burden, and treatment of insomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(10):1417–23. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roehrs TA, Roth T. Safety of insomnia pharmacotherapy. Sleep Med Clin. 2006;1(3):399–407. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ebert B, Wafford KA, Deacon S. Treating insomnia: Current and investigational pharmacological approaches. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112(3):612–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass J, Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, et al. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1169. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth T, Roehrs TA, Vogel GW, et al. Evaluation of hypnotic medications. In: Prien RF, Robinson DS, editors. Clinical evaluation of psychotropic drugs: principles and guidelines. New York: Raven; 1994. pp. 579–92. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor S, McCracken CF, Wilson KC, et al. Extent and appropriateness of benzodiazepine use. Results from an elderly urban community. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:433–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.173.5.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh JK, Krystal AD, Amato DA, et al. Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with eszopiclone for six months: effect on sleep, quality of life, and work limitations. Sleep. 2007;30(8):959–68. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dundar Y, Dodd S, Strobl J, et al. Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19(5):305–22. doi: 10.1002/hup.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: A review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morin CM. Insomnia : Psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stepanski EJ. Hypnotics should not be considered for the initial treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1(2):125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, et al. Epidemiology of insomnia: Prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7(2):123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider-Helmert D. Why low-dose benzodiazepine-dependent insomniacs can't escape their sleeping pills. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1988;78(6):706–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1988.tb06408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bastien CH, LeBlanc M, Carrier J, et al. Sleep EEG power spectra, insomnia, and chronic use of benzodiazepines. 2003;26(3):313–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan K, Dixon S, Mathers N, et al. Psychological treatment for insomnia in the management of long-term hypnotic drug use: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(497):923–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brentsen P, Hensig G, McKenzie L, et al. Prescribing benzodiazepine- acritical incident study of a physician dilemma. Soc Sc Med. 1999;49:459–467. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin CM, Baillargeon L, Bastien C. Discontinuation of sleep medications. In: Lichstein LK, Morin CM, editors. Treatment of late-life insomnia. Thousand Oak: Sage Publications; 2000. pp. 271–96. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kan CC, Breteler MH, Zitman FG. High prevalence of benzodiazepine dependence in outpatient users, based on the DSM-III-R and ICD-10 criteria. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;96(2):85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1997.tb09911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor KP, Marchand A, Belanger L, et al. Psychological distress and adaptational problems associated with benzodiazepine withdrawal and outcome: a replication. Addict Behav. 2004;29(3):583–93. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oude Voshaar RC, Gorgels WJ, Mol AJ, et al. Predictors of long-term benzodiazepine abstinence in participants of a randomized controlled benzodiazepine withdrawal program. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(7):445–52. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell VJ, Lader MH. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of benzodiazepine dependence. London: Mental Health Fondation; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Voshaar RC, Gorgels WJ, Mol AJ, et al. Tapering off long-term benzodiazepine use with or without group cognitive-behavioural therapy: three-condition, randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:498–504. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorgels WJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Mol AJ, et al. Discontinuation of long-term benzodiazepine use by sending a letter to users in family practice: a prospective controlled intervention study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;78(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morin CM, Bastien C, Guay B, et al. Randomized clinical trial of supervised tapering and cognitive behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation in older adults with chronic insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):332–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morin CM, Belanger L, Bastien C, et al. Long-term outcome after discontinuation of benzodiazepines for insomnia: a survival analysis of relapse. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rickels K, Schweizer E, Case WG, et al. Long-term therapeutic use of benzodiazepines. I. Effects of abrupt discontinuation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(10):899–907. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810220015002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Whitehead A. Tolerance and rebound insomnia with rapidly eliminated hypnotics: a meta-analysis of sleep laboratory studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(5):287–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zavesicka L, Brunovsky M, Matousek M, et al. Discontinuation of hypnotics during cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belanger L, Morin CM, Bastien C, et al. Self-efficacy and compliance with benzodiazepine taper in older adults with chronic insomnia. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):281–7. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(1):19–34. doi: 10.2165/0023210-200923010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belleville G, Morin CM. Hypnotic discontinuation in chronic insomnia: impact of psychological distress, readiness to change, and self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):239–48. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holton A, Riley P, Tyrer P. Factors predicting long-term outcome after chronic benzodiazepine therapy. J Affect Disord. 1992;24(4):245–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90109-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schweizer E, Rickels K, De Martinis N, et al. The effect of personality on withdrawal severity and taper outcome in benzodiazepine dependent patients. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):713–20. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, et al. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: Update of the recent evidence (1998-2004) Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398–414. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.11.1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lichstein KL, Peterson BA, Riedel BW, Means MK, Epperson MT, Aguillard RN. Relaxation to assist sleep medication withdrawal. Behavior Modification. 1999;23:379–402. doi: 10.1177/0145445599233003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baillargeon L, Landreville P, Verreault R, et al. Discontinuation of benzodiazepines among older insomniac adults treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy combined with gradual tapering: A randomized trial. CMAJ. 2003;169(10):1015–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baillargeon L, Demers M, Ladouceur R. Stimulus-control: nonpharmacologic treatment for insomnia. Canadian Family Physician. 1998;44:73–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belleville G, Guay C, Guay B, et al. Hypnotic taper with or without self-help treatment: A randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75(2):325–35. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morin CM, Colecchi CA, Ling WD, Sood RK. Cognitive-behavior therapy to facilitate benzodiazepine discontinuation among hypnotic-dependent patients with insomnia. BehTher. 1995;26:733–745. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lichstein KL, Johnson RS. Relaxation for insomnia and hypnotic medication use in older women. Psychology and Aging. 1993;8:103–111. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.8.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riedel BW, Lichstein KL, Peterson BA, Epperson MT, Means MK, Aguillard RN. A comparison of the efficacy of stimulus control for medicated and non-medicated insomniacs. Behavior Modification. 1998;22:3–28. doi: 10.1177/01454455980221001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Backhaus J, Hohagen F, Voderholzer U, Riemann D. Long-term effectiveness of a short-term cognitive-behavioral group treatment for primary insomnia. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2001;251:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s004060170066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Verbeek I, Schreuder K, Declerck G. Evaluation of short-term nonpharmacological treatment of insomnia in a clinical setting. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999;47:369–383. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Espie CA, Lindsay WR, Brooks DN. Substituting behavioural treatment for drugs in the treatment of insomnia: an exploratory study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1988;19(1):51–6. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(88)90010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oude Voshaar RC, Couvee JE, van Balkom AJ, et al. Strategies for discontinuing long-term benzodiazepine use: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:213–20. doi: 10.1192/bjp.189.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]