Abstract

Replica exchange molecular dynamics and implicit solvent model are used to study two oligomeric species of Aβ peptides, dimer and tetramer, which are typically observed in in vitro experiments. Based on the analysis of free energy landscapes, density distributions, and chain flexibility, we propose that the oligomer formation is a continuous transition occurring without metastable states. The density distribution computations suggest that Aβ oligomer consists of two volume regions—the core with fairly flat density profile and the surface layer with rapidly decreasing density. The core is mostly formed by the N-terminal residues, whereas the C-terminal tends to occur in the surface layer. Lowering the temperature results in the redistribution of peptide atoms from the surface layer into the core. Using these findings, we argue that Aβ oligomer resembles polymer globule in poor solvent. Aβ dimers and tetramers are found to be structurally similar suggesting that the conformations of Aβ peptides do not depend on the order of small oligomers.

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid fibrils are ordered macromolecular assemblies resulting from the aggregation of polypeptide chains.1 Because amyloidogenic polypeptides have low sequence homology, it appears that the propensity to form fibrils is a generic property of proteins. Amyloid assembly is a complex multistage conformational transition, which begins with the oligomerization of monomers and gradually leads to the appearance of protofibrils and mature fibrils as final products.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The current interest in amyloidogenesis is twofold. Self-assembled amyloid structures have potential technological applications, such as production of conductive nanowires or peptide-metal composites.6, 7 On the other hand, amyloidogenesis is linked to more than 20 various medical disorders, including Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Creutzfeldt–Jakob diseases.8

There is a compelling experimental evidence suggesting that the onset of Alzheimer disease is related to the aggregation of Aβ peptides,9 which are produced in the course of proteolysis of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein. Although these peptides are released in a variety of lengths, the 40-residue species, Aβ1–40, are most abundant.1 At micromolar concentration and normal physiological conditions (∼300 K and normal pH) Aβ oligomers coexist with monomers10 and demonstrate a distinctive size distribution existing predominantly in the form of dimeric through tetrameric species.11, 12 Higher order oligomers have significantly smaller frequency of occurrence. Recent biomedical studies have showed that Aβ oligomers are the primary cytotoxic species in Alzheimer disease.2, 13, 14, 15 It has been reported that synaptic structure and function are impaired even by the smallest Aβ oligomers, dimers.16 There are also experimental indications of the dynamic equilibrium between soluble oligomeric species and amyloid fibrils.17 These observations implicate a crucial role of Aβ oligomers in amyloidogenesis.

Aβ monomers have been a focus of numerous experimental studies. In aqueous solution they are largely unstructured lacking stable secondary or tertiary structures.18, 19 The end products of amyloid assembly, Aβ fibrils, are characterized by extensive and remarkably homogeneous β-sheet structure.20, 21, 22 In contrast, relatively little is known about the structures of Aβ oligomers. In part, experimental difficulties in obtaining structural information are due to rapid interconversion of oligomeric species and apparent lack of stable structure.12 A useful alternative are computational methods, particularly, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which can probe the details of Aβ amyloid formation at all-atom resolution.23, 24 Several studies have explored the conformational properties of Aβ1–40 monomers25, 26 and its fragments27, 28, 29 as well as fibril growth and stability.30, 31, 32 The full-length Aβ1–40 was shown to have several structured regions, including short β-strands, helices, and β-turns, in generally random coil-like ensemble of conformations.25, 26 MD investigations of Aβ oligomers, which are more computationally intensive, have been recently reported.33, 34, 35, 36, 37 In general, these studies have shown that aggregation leads to considerable conformational changes in Aβ peptides. For example, we have found that interpeptide interactions in Aβ dimers induce a profound shift in the secondary structure, resulting in the conversion of helical states into β-strand conformations.35 Furthermore, the sequence region 10-23 in Aβ peptide was observed to form most of interpeptide interactions upon aggregation.35, 36 Studies of coarse grained models of Aβ peptides showed that Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 species form oligomers via distinct pathways in agreement with experimental data.37 However, many questions concerning oligomer structure and assembly remain unexplored. For example, (1) what are the basic physicochemical characteristics of Aβ oligomers? In particular, do oligomers resemble polymer globules? (2) What are the free energy landscapes of oligomer assembly and the nature of underlying structural transitions? (3) Are there differences between the conformational ensembles of oligomers of different orders? In other words, does the structure of small Aβ oligomer undergo further changes upon the addition of new chains?

To answer these questions, we use exhaustive replica exchange MD (REMD) and implicit solvent model to study the structural properties of Aβ dimers and tetramers. Because these two species represent the most abundant Aβ oligomers, we can make some tentative conclusions about their generic properties. We demonstrate that the density distribution in Aβ oligomer resembles the one in the globule formed by flexible polymer chains. Based on this analogy and the analysis of free energy landscapes, we propose that the formation of Aβ oligomers is consistent with the continuous barrierless transition. We further show that the oligomer core is predominantly formed by the N-terminals of Aβ peptides. By analyzing the radial density distributions, fluctuations, and solvent accessible surface areas along Aβ sequence, we infer that the structural characteristics of dimers and tetramers are similar. We conclude the paper with the comparison of our in silico results with experimental data.

METHODS

Simulation model

To perform simulations of Aβ peptides we used CHARMM MD program38 and united atom force field CHARMM19 coupled with the SASA implicit solvent model.39 Detailed description of the CHARMM19+SASA model and its extensive testing were reported in our previous studies.35, 40, 41, 42 In particular, we have shown that the CHARMM19+SASA force field correctly reproduces the experimental distribution of chemical shifts for Cα and Cβ atoms in Aβ monomers.35, 43 In the past, CHARMM19+SASA model has been used to fold α-helical and β-sheet polypeptides44, 45 and to study aggregation of amyloidogenic peptides.46, 47 Additional arguments supporting the use of CHARMM19+SASA implicit solvent model are presented in the supplementary material.48

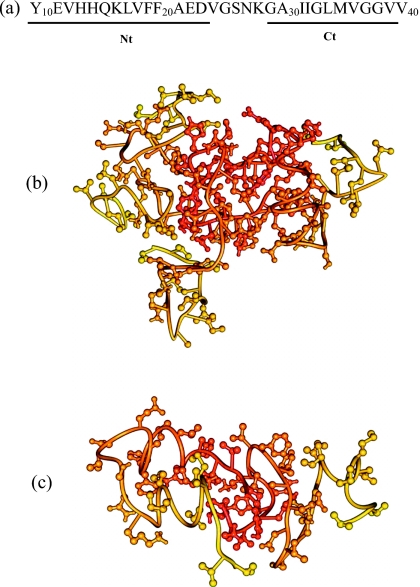

In this study we use Aβ10–40 peptides, the N-terminal truncated fragments of the full-length Aβ1–40 [Fig. 1a]. Solid-state NMR experiments have indicated that Aβ1–40 and Aβ10–40 form similar twofold symmetry fibril structures.21, 49 According to the experiments11 and simulations,41 Aβ1–40 and Aβ10–40 oligomers share significant similarities in terms of their size distributions and structure. It is also known that the first nine N-terminal residues in Aβ1–40 fibril are disordered.21 Consequently, Aβ10–40 is used as a model of the full-length Aβ1–40 peptide.

Figure 1.

(a) The sequence of Aβ10–40 peptide and the allocation of the N-terminal Nt and C-terminal Ct regions. [(b) and (c)] Typical structures of Aβ oligomers, tetramer (b) and dimer (c), sampled at 360 K. The N- and C-terminals are colored in shades of red and yellow, respectively. The Aβ Nt region tends to form the oligomer’s core, whereas the Ct mostly makes up the surface layer. The structures are visualized using Chimera (Ref. 60).

Two Aβ10–40 systems, tetramer and dimer, were considered [Figs. 1b, 1c]. The dimer system was introduced in our previous studies.35, 41 The tetramer system, which is similar to the dimer, involves four identical unconstrained Aβ10–40 peptides. Tetramer and dimer were subject to spherical boundary condition with the radius Rs=90 Å and the force constant ks=10 kcal∕(mol Å2). The concentration of Aβ peptides was therefore on the order of ∼mM.

Replica exchange simulations

Conformational sampling was performed using REMD.50 The REMD implementation is described in our previous studies.35, 47 Briefly, 24 replicas were distributed linearly in the temperature range from 300 to 530 K with the increment of 10 K. This temperature range spans the spectrum of conformational states of Aβ peptides from aggregated to completely dissociated. Small temperature increment provides significant overlap of energy distributions from neighboring replicas. The exchanges were attempted between all neighboring replicas with the average acceptance rate of 38%. Between replica exchanges, the system evolved using NVT underdamped Langevin dynamics with the damping coefficient γ=0.15 ps−1 and the integration step of 2 fs. The simulation time between replica exchanges was set to 80 ps. Eight REMD trajectories were produced for the tetramer resulting in the cumulative simulation time of 154 μs. Because the initial parts of REMD trajectories are not equilibrated and must be excluded from thermodynamic analysis, the cumulative equilibrium simulation time was reduced to τsim≈126 μs. The REMD trajectories were started with random distributions of peptides in the sphere. The REMD simulations for the dimer were described earlier.35

Computation of structural probes

To probe the interactions between Aβ peptides, we computed the number of side chain contacts. A side chain contact is formed if the distance between the centers of mass of side chains is less than 6.5 Å. If both amino acids in contact are apolar, the contact is considered hydrophobic. Two peptides are considered aggregated if there is at least one hydrophobic side chain contact between them. The radial distribution function g(r) reports the atom number density at the distance r from the center of mass of oligomer. To compute g(r) we considered nonhydrogen atoms from all peptides. The histogram of atom distances r was constructed using the bin-size of 0.5 Å. The solvent accessible surface area of amino acid was computed using SASA module in CHARMM program.39 To probe the extent of burial of amino acid X we considered the relative accessible surface area (rASA) defined as ASA∕ASA0. Here ASA and ASA0 are the accessible surface areas of amino acid X in a given conformation and in the reference extended trimer Gly-X-Gly.51

Throughout the paper, angular brackets ⟨..⟩ imply thermodynamic averages. Because tetramer (dimer) system includes several indistinguishable peptides, we report averages over four (two) peptides. The distributions of states produced by REMD were analyzed using multiple histogram method.52 The convergence of REMD simulations and error analysis are presented in the supplementary material.48

RESULTS

Using REMD we probe the conformational ensembles of Aβ10–40 dimers and tetramers (Fig. 1). Following experimental Aβ fibril structure,21 two sequence regions in Aβ10–40 are distinguished-the N-terminal (Nt, residues 10–23) corresponding to the first fibril β-strand and the C-terminal (Ct, residues 29–39) corresponding to the second fibril β-strand [Fig. 1a]. The thermodynamic quantities for Aβ oligomers are computed at the temperature 360 K, at which Aβ peptide locks into fibril-like state during fibril growth as reported earlier.40, 47

Thermodynamics of Aβ oligomer assembly

We start the investigation of Aβ10–40 oligomers by computing the probability P4 of forming the largest oligomer, tetramer, in the system consisting of four peptides. Operationally, P4 is defined as a probability of forming the four-peptide aggregate in which each chain makes at least one interpeptide hydrophobic side chain contact. At 360 K,P4≈0.99, suggesting that at the Aβ concentration of ∼mM, the tetramer is a single aggregate present in the system. The probability P2 of forming a dimer in the two-peptide system (defined similarly as P4) is ≈0.98 at 360 K. Because the tetramer and dimer are stable at 360 K, we use these terms to refer to the systems consisting of four and two peptides, respectively.

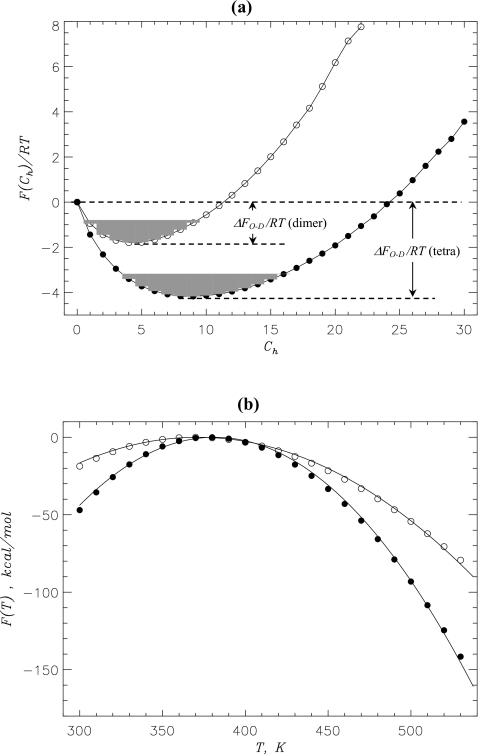

To map the free energy landscape of Aβ aggregation we computed the free energy of a peptide as a function of the number of interpeptide hydrophobic contacts, F(Ch) [Fig. 2a]. Because the oligomers are formed at 360 K (P4≈P2≈1.0), F(Ch) probes the free energy of incorporating a peptide into oligomer. The free energy profiles for the tetramer and dimer in Fig. 2a are similar, although the dimer profile is shallower. According to Fig. 2a, the free energy of incorporating a peptide into the tetramer ΔFO-D is ≈−6.4RT and is reduced to −3.7RT for the dimer. Therefore, compared to the dimer the free energy of peptide associated state in the tetramer is lower by ΔΔFO-D=ΔFO-D(tetra)−ΔFO-D(dimer)≈−2.7RT. Both free energy profiles F(Ch) in Fig. 2a show no metastable states or barriers suggesting that oligomer formation is a continuous transition. It is also important that the plots F(Ch) remain barrierless in the entire temperature range, in which the oligomer state is stable, i.e., P4 or P2>0.5(T≲490 K).

Figure 2.

(a) Free energies of Aβ10–40 peptide F(Ch) as a function of the number of interpeptide hydrophobic side chain contacts Ch at 360 K. The free energy of peptide incorporation into the oligomer is ΔFO-D=FO−FD, where FO and FD=0 are the free energies of the associated (O) and dissociated (D,Ch=0) states. FO is obtained by integrating over the O states (shaded in gray) for which F(Ch)≤Fmin+1.0RT, where Fmin is the minimum in F(Ch). (b) Temperature dependence of the oligomer free energy F(T). Quadratic fitting functions F(T)≃−α(T−To)2 are shown by black continuous curves. The fitting parameters are α=−0.003 kcal∕(mol K2),To=371 K (dimer) and α=−0.007 kcal∕(mol K2), To=382 K (tetramer). Maximum values of F(T) are set to zero. In panels (a) and (b) the data for dimer and tetramer are shown by open and filled circles, respectively. The figure suggests that the formation of oligomer is a continuous transition without intermediate states.

The temperature dependence of the oligomer free energy F(T) can be indicative of the nature of transition associated with the oligomer formation. For clarity, F(T) includes the contributions from inter- and intrapeptide interactions and conformational entropy but omits the ideal gas term associated with translational entropy. If the structural transition is continuous, then F(T) is expected to follow a quadratic dependence on temperature at T<To, i.e., F(T)∼−(T−To)2, where To is the temperature, at which oligomer formation is completed53 (see Sec. 4). Figure 2b demonstrates that the tetramer F(T) can be fit using the quadratic function with To=382 K. The dimer F(T) also follows the quadratic dependence, from which we obtained To=371 K. Smaller value of To for the dimer is consistent with the smaller free energy gain associated with incorporating a peptide into the dimer compared to the tetramer.

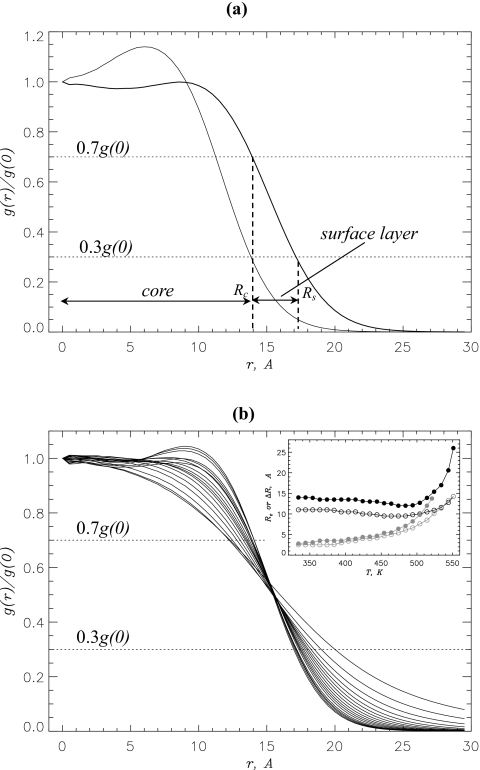

The analysis of the density profile in the oligomer is presented in Fig. 3a. This figure shows the normalized radial distribution function for the number density g(r) in the tetramer and dimer. Two observations follow from this plot. First, the density profiles for both oligomers are qualitatively similar. As expected the dimer g(r) decreases with r faster than for the tetramer indicating smaller spatial dimensions of the dimer. Second, the profiles of g(r) suggest that there are two volume regions in the oligomer-the core with relatively constant density (especially in the tetramer) and the surface layer in which the density rapidly decays. To get better understanding of the density distribution, we plot in Fig. 3b the tetramer functions g(r) computed in the temperature range of 330–490 K. It is seen that the inflection point atr≈15 Å does not depend on temperature and approximately corresponds to the midpoint of g(r) profile. This suggests that with the increase in temperature, a redistribution of oligomer atoms between the core and the surface layer takes place. As a result, the surface layer (and the oligomer itself) expands with temperature.

Figure 3.

(a) Normalized radial distribution function for the number density g(r) in the Aβ tetramer (thick line) and dimer (thin line) at 360 K. The distance r is measured with respect to the center of mass of the oligomer. The profiles of g(r) suggest that the oligomer volume can be divided into two regions—the core (r<Rc) and the surface layer (Rc<r<Rs). (b) Normalized radial distributions g(r) for the tetramer computed in the temperature range from 330 to 490 K with 5 K increment. The plots implicate the expansion of the oligomer with the increase in temperature. Inset: Temperature dependences of the core radius Rc (in black) and the thickness of surface layer ΔR (in gray): tetramer (filled circles) and dimer (open circles). Monotonic increase in ΔR with temperature coupled with relatively constant Rc suggests that the oligomer expansion is due to the swelling of the surface layer. In (a) and (b) dotted lines mark the minimum density levels in the core (0.7g(0)) and in the surface layer (0.3g(0)).

To probe the changes in tetramer structure with temperature, we assume that the tetramer core is confined to the sphere with the radius Rc defined from the conditiong(Rc)=0.7g(0). The surface layer is restricted to the concentric volume with the radii (Rc,Rs), where Rs is obtained from g(Rs)=0.3g(0). The inset to Fig. 3b demonstrates that the core radius Rc remains almost constant at 330 K<T≲490 K by changing merely 14%. At 360 K the core size is Rc≈14.0 Å. At high temperatures (T≳490 K), the core dramatically expands due to the dissociation of the tetramer. In contrast, the surface thickness ΔR=Rs−Rc monotonically increases threefold in the temperature range of 330–490 K. At T≳490 K, ΔR approaches Rc. The temperature dependencies of Rc and ΔR for the dimer are very similar to those of the tetramer. At 360 K the size of the dimer core Rc is 11.0 Å, which is 3.0 Å smaller than of the tetramer. This difference in Rc is consistent with the difference in the number of atoms in the dimer and tetramer.

Using the radial distribution functions g(r) and the values of core radii Rc, it is straightforward to compute the average number density in the oligomer core nc. The temperature dependence nc(T) for the tetramer and dimer shown in Fig. 4 demonstrates that the oligomer core becomes more dense with the decreases in T. Because the core dimensions remain almost constant with temperature [Fig. 3b], this implies that the peptide atoms are “pumped” (redistributed) into the core from the surface layer. This figure also reveals that the tetramer and dimer densities at T≲400 K are almost the same. As the core absorbs more peptide atoms, it is of interest to consider the temperature dependence of the fraction of atoms in the core, Φc(T). The inset of Fig. 4 reveals that more than half of tetramer and dimer atoms make up the core at the temperatures T≤Tc≈370 K. One can interpret Tc as the temperature at which the formation of oligomer is completed. We note that Tc are in agreement with the temperatures of oligomer formation To estimated from the temperature dependence of the free energy [Fig. 2b].

Figure 4.

The temperature dependence of the core number density nc(T) in Aβ oligomer. The plot shows that the atom packing in the core increases at low temperatures. Inset: the fraction of oligomer atoms in the core, Φc(T), as a function of temperature. The temperature, at which half of Aβ atoms are confined to the core, approximately coincides with the temperature of oligomer formation To [Fig. 2b]. Dotted line marks the level Φc=0.5. Data for the dimer and tetramer are shown by open and filled circles, respectively.

Structure of Aβ oligomers

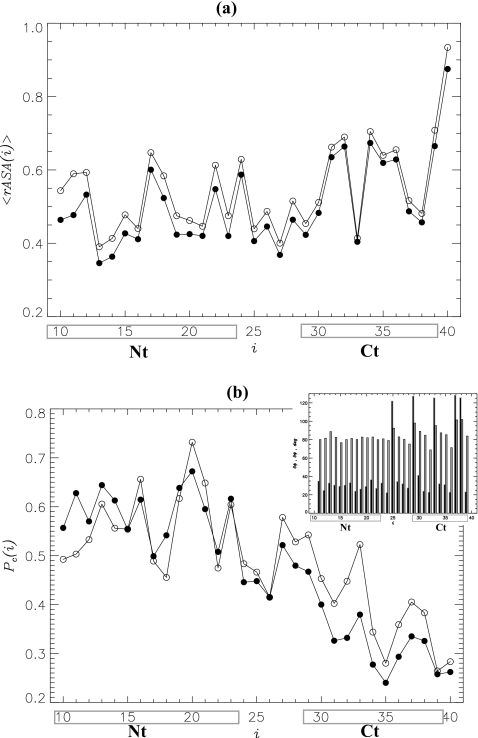

The analysis of the density distribution presented above suggests that Aβ oligomer is a two-tier system in which the core region of nearly constant density is surrounded by the surface layer of rapidly decreasing density. Because Aβ peptide is a heteropolymer, it is conceivable that the sequence regions Nt and Ct have different propensities to form the core and surface layer. To explore this possibility, we computed the distribution of relative solvent accessible surface areas (⟨rASA(i)⟩) of Aβ amino acids i in the tetramer and dimer [Fig. 5a]. There are considerable variations in ⟨rASA(i)⟩ along the sequence, but two conclusions can be drawn. First, although there is a small systematic decrease in rASA in the tetramer compared to the dimer, their profiles ⟨rASA(i)⟩ remain qualitatively similar. More importantly, the distribution of rASA values indicates that the C-terminal is exposed to solvent to a larger extent than the N-terminal. Indeed, for the dimer the ratio ⟨rASA(Ct)⟩∕⟨rASA(Nt)⟩≈1.2, whereas for the tetramer it increases to 1.3. (Here ⟨rASA(Nt)⟩ and ⟨rASA(Ct)⟩ are the average rASA values for the Nt and Ct sequence regions.)

Figure 5.

(a) The distribution of relative solvent accessible surface areas of amino acids i, ⟨rASA(i)⟩, in Aβ peptide. (b) Probabilities of occurrence of the residues i in the oligomer core, Pc(i). Data for the dimer and tetramer are shown by open and filled circles, respectively. Inset: standard deviations in the backbone dihedral angles ϕ(i), δϕ(i) (black bars), and ψ(i), δψ(i) (gray bars) in the tetramer as a function of the amino acid index i. The figure shows that the N-terminal Nt is mostly buried in the oligomer core, whereas the C-terminal Ct forms the surface layer. The Nt and Ct amino acids in Aβ peptide are boxed. The plots are computed at 360 K.

To directly check the residue distribution in the oligomer volume, we computed the probability of occurrence of the residue i in the core, Pc(i). In these computations the residue position is given by the location of its side chain center of mass. The plot of Pc(i) shown in Fig. 5b reveals that the probability of finding the N-terminal Nt in the tetramer core is significantly higher than of the C-terminal Ct. Specifically, the average probabilities of occurrence in the core of the Nt and Ct residues are Pc(Nt)≈0.59 and Pc(Ct)≈0.33, respectively, i.e., these probabilities differ nearly twofold. Similar results were obtained for Aβ dimer (Pc(Nt)≈0.57,Pc(Ct)≈0.40). Therefore, the oligomer core is predominantly composed of the amino acids from the Aβ N-terminal.

Further support for the burial of the N-terminal in the tetramer core comes from the distribution of fluctuations in the backbone dihedral angles ϕ(i) and ψ(i) along Aβ sequence (i is a residue index). It follows from the inset of Fig. 5b that the standard deviation in the ψ dihedral angle, δψ(i), has little variation with i. For example, the average values of δψ(i) for the Nt and Ct sequence regions are 82° and 88°. However, there is more than twofold difference in the standard deviations in the ϕ dihedral angle, δϕ(i), between the Nt and Ct (30° versus 64°, respectively). Large values of δϕ(i) in the Ct region are attributed to Gly residues. Therefore, the C-terminals in Aβ tetramer experience larger structural fluctuations than the N-terminals. Similar results have been obtained for the dimer (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Aβ oligomer resembles polymer globule

Our results suggest that Aβ oligomer formation is described by a continuous structural transition. This conclusion is based on two lines of evidence. First, we showed that the free energy landscape associated with oligomer formation appears to be barrierless. Indeed, the peptide free energy F(Ch) computed as a function of the number of interpeptide hydrophobic contacts Ch reveals no metastable states [Fig. 2a]. This observation holds in the entire temperature range in which oligomer (dimer or tetramer) is stable. Second, the oligomer free energy F(T) follows a quadratic temperature dependence near the temperature of oligomer formation To [Fig. 2b]. In statistical mechanics a quadratic dependence of the free energy of the low symmetry phase on the external parameter (in our case, temperature T<To) is associated with continuous phase transition.53

The continuous nature of oligomer formation is also consistent with the density distribution in the oligomer. Figure 3 shows that the oligomer volume can be separated into the core with relative flat density profile and the surface layer in which density rapidly decreases. Importantly, the core dimensions remain fairly constant with temperature, whereas the surface layer expands with temperature increase. According to Fig. 4, as temperature decreases the peptide atoms are pumped from the surface layer into the core, causing a steady increase in the core density. This density distribution in the oligomer strongly resembles the one observed in the polymer globule near the coil-globule transition.54 According to the mean field theory of coil-globule transition polymer globule expands with the increase in temperature due to swelling of the surface layer. Through the volume of the core the density remains constant, but its value decreases as the system approaches the coil transition.

The globule formation is a continuous (barrierless) transition as long as a polymer remains flexible,54 i.e., its persistence length l is comparable with the chain thickness d. We check if this requirement is satisfied for Aβ tetramer. The thickness d can be estimated from the packing of Aβ peptides in the experimentally resolved fibril structure.21, 47 In this structure Aβ peptides are arranged in parallel in-registry β-sheets. The average interpeptide distance between the Cα atoms from matching residues is d≈4.8 Å. To compute the persistence length l we define the backbone vectors, where is the radius vector of the Cα atom in the residue i. The autocorrelation function , where the bar indicates an average over i, peptide, and all equilibrated tetramer structures, probes the correlations in the chain orientation as a function of the residue distance k. Consistent with the polymer theory,54s(k) can be fit with an exponential function s(k)∼exp(−k∕k0), where k0 is a characteristic distance of correlation decay. The persistence length l can be computed using l=k0⟨r⟩, where ⟨r⟩ is the average distance between successive Cα atoms. At T=490 K, which approximately corresponds to the tetramer dissociation, l≈4.8 Å. The persistence length is reduced to 3.8 Å at 360 K due to entanglement of Aβ chains in dense oligomer core. It is important that at both temperaturesl≲d, indicating that the backbone of Aβ peptides is flexible. Therefore, exploiting the analogy with the polymer globule, we propose that the oligomer formation is consistent with continuous transition. The continuous transition is likely the result of low structural ordering in small Aβ oligomers.

It is also useful to mention that continuous structural transition is predicted to occur during denaturation of double-stranded heterogeneous DNA.55 Furthermore, according to spectrometry experiments DNA oligomers formed by short strands (from 15 to 60 bases) demonstrate although sharp but still continuous denaturation transition at the concentration of 100 mM.56 These experimental and theoretical results lend support to our findings that the oligomer formation is continuous at least in the range of millimolar polymer concentrations. Additional studies will be needed to establish if continuous nature of oligomer assembly remains valid at lower peptide concentrations.

Structural properties of Aβ dimers and tetramers are similar

Analysis of Aβ dimer and tetramer suggests that their properties are similar. Above we have shown that the tetramer and dimer assembly resembles the formation of polymer globule. The temperatures To, at which the assembly of these oligomers is completed, differ only by about 10 K. Now we further compare Aβ dimers and tetramers by considering specific structural quantities. First, it is noteworthy that according to Fig. 4, the tetramer and dimer densities at T≲400 K are similar. In addition, the thicknesses of surface layers ΔR in Aβ dimer and tetramer are almost identical [Fig. 3b]. Second, computations of accessible surface areas of Aβ residues suggest very similar trends in the exposure of individual amino acids in both oligomers [Fig. 5a]. In the dimer and tetramer, the C-terminal is mostly found in the surface layer and is exposed to solvent, whereas the N-terminal tends to be buried in the oligomer core [Fig. 5b]. Aβ peptides in both oligomers have uneven distribution of structural fluctuations along the sequence, with the C-terminal being more flexible than the N-terminal. Third, the analysis of the energetics of Aβ peptides in the dimers and tetramers also points out to the similarities in their conformational ensembles. For example, at 360 K the average energy of intrapeptide nonbonded interactions in the dimer is −229 kcal∕mol, which is very close to the tetramer value (−216 kcal∕mol).

In our previous studies we have reported that the aggregation interface in Aβ dimers predominantly involves the N-terminal.35, 41 Specifically, the numbers of interpeptide side chain contacts formed by the Nt and Ct regions, ⟨C(Nt)⟩ and ⟨C(Ct)⟩, differ twofold at 360 K. For the tetramer, the values of ⟨C(Nt)⟩ and ⟨C(Ct)⟩ are 30.2 and 14.9, respectively, which imply almost identical ratios of these quantities for the tetramer and dimer. Therefore, the conformational ensembles of Aβ peptides sampled in the dimer and tetramer appear to be similar.

Our conclusion about the importance of the Nt region for aggregation is consistent with some of the recent implicit solvent MD studies.36, 57, 58 In particular, Urbanc et al. showed that the central hydrophobic cluster (residues 17–21) plays a dominant role in Aβ1–40 aggregation.58 However, given a complexity of Aβ oligomer assembly, studies with explicit solvent models will be needed to ascertain the role of the Nt region in aggregation.

Comparison of experiments and simulations

It is important to compare our structural analysis of Aβ oligomers with experimental data. Although we are not aware of the experiments probing the thermodynamics of Aβ oligomer formation, few recent studies have explored the distribution and sizes of these mobile aggregates. Gel electrophoresis experiments have shown that Aβ peptides exist as monomers or oligomers of the sizes up to tetramer at micromolar concentration.12, 59 It follows from the electron microscopy studies that the dimers and tetramers have overall spherical shape with the diameter D increasing from 18 Å (dimer) to 220 Å (tetramer).12 The experimental size of the dimer is in a good agreement with our estimate of the size of the dimer core (D=2Rc=22 Å). Further experimental and simulation studies will clarify the discrepancy in the tetramer sizes.

Our conclusion that the structural properties of the dimers and tetramers are similar is in accord with the experimental analysis of the secondary structure of Aβ oligomers.12 The fractions of the residues in β-sheet conformation in the dimer and tetramer are 0.39 and 0.45, whereas the α-helix fractions are 0.11 and 0.13, respectively. These experimental data do not reveal considerable variation in the structures of Aβ oligomers. It is important to emphasize that the conformational ensemble of Aβ oligomers is distinct from those associated with Aβ monomers or fibrils as shown in recent simulations of O’Brien et al.31

Finally, we discuss an apparent discrepancy in the oligomer size distribution between experiments and simulations. In our two- and four-peptide systems, the largest possible oligomers (dimer or tetramer) are formed with an overwhelming probability (∼1.0). At the same time, experiments detect a continuous distribution of Aβ species from monomers to tetramers.12, 59 The likely source of this discrepancy is an elevated Aβ concentration used in our study. The experimental measurements are performed at micromolar concentrations, whereas the Aβ concentration in the simulations is in the millimolar range (that constitutes a 103 difference in concentrations). In silico elevated Aβ concentration is used for computational efficiency to enhance sampling of aggregated states. It is therefore reasonable to suggest that with the increase in Aβ concentration, the thermodynamic equilibrium is shifted to higher order oligomers disfavoring monomeric states or small oligomers.

CONCLUSIONS

We have investigated two oligomeric species of Aβ peptides, dimer and tetramer, which are typically observed inin vitro experiments. Based on the analysis of free energy landscapes, density distributions, and chain flexibility, we proposed that the oligomer assembly is a continuous transition occurring without metastable states. The density distribution computations revealed that Aβ oligomer consists of the core with fairly flat density profile and the surface layer with rapidly decreasing density. The core is mostly formed by the N-terminal residues, whereas the C-terminal tends to occur in the surface layer. Lowering the temperature results in the redistribution of peptide atoms from the surface layer into the core. Taken together these findings led us to argue that Aβ oligomers resemble polymer globules in poor solvent. Aβ dimers and tetramers are found to be structurally similar suggesting that the conformations of Aβ peptides do not depend on the order of small oligomers. The available experimental data appear to support the conclusions of our study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIH) under Grant No. R01 AG028191. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or NIH.

References

- Dobson C. M., Nature (London) 426, 884 (2003). 10.1038/nature02261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkitadze M. D., Bitan G., and Teplow D. B., J. Neurosci. Res. 69, 567 (2002). 10.1002/jnr.10328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R. M., Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 4, 155 (2002). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.4.092801.094202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R., Sawaya M. R., Balbirnie M., Madsen A. O., Riekel C., Grothe R., and Eisenberg D., Nature (London) 435, 773 (2005). 10.1038/nature03680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makin O. S., Atkins E., Sikorski P., Johansson J., and Serpell L. C., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 315 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0406847102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reches M. and Gazit E., Science 300, 625 (2003). 10.1126/science.1082387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Challa S. R., Medforth C. J., Qiu Y., Watt R. K., Pea D., Miller J. E., van Swolab F., and Shelnutt J. A., Chem. Commun. (Cambridge) 2004, 1044. 10.1039/b402126f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J., Nature (London) 426, 900 (2003). 10.1038/nature02264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J. and Selkoe D. J., Science 297, 353 (2002). 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan S. and Reif B., Biochemistry 44, 1444 (2005). 10.1021/bi048264b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitan G., Vollers S. S., and Teplow D. B., J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34882 (2003). 10.1074/jbc.M300825200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K., Condron M. M., and Teplow D. B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14745 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0905127106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R., Head E., Thompson J. L., McIntire T. M., Milton S. C., Cotman C. W., and Glabe C. G., Science 300, 486 (2003). 10.1126/science.1079469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C. and Selkoe D. J., Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 101 (2007). 10.1038/nrm2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor M. T., Kmmerer N., Schubert V., Esteras-Chopo A., Dotti C. G., de la Paz M. L., and Serrano L., J. Mol. Biol. 375, 695 (2008). 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M., Li S., Mehta T. H., Garcia-Munoz A., Shepardson N. E., Smith I., Brett F. M., Farrell M. A., Rowan M. J., Lemere C. A., Regan C. M., Walsh D. M., Sabatini B. L., and Selkoe D. J., Nat. Med. 14, 837 (2008). 10.1038/nm1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carulla N., Caddy G. L., Hall D. R., Zurdo J., Gair M., Feliz M., Giralt E., Robinson C. V., and Dobson C. M., Nature (London) 436, 554 (2005). 10.1038/nature03986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler W. P., Stimson E. R., Lachenmann M. J., Ghilardi J. R., Lu Y., Vinters H. V., Mantyh P. W., Lee J. P., and Maggio J. E., J. Struct. Biol. 130, 174 (2000). 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riek R., Guntert P., Dobeli H., Wipf B., and Wuthrich K., Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 5930 (2001). 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02537.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkoth T. S., Benzinger T., Urban V., Morgan D. M., Gregory D. M., Thiyagarajan P., Botto R. E., Meredith S. C., and Lynn D. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 7883 (2000). 10.1021/ja000645z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A. T., Yau W. -M., and Tycko R., Biochemistry 45, 498 (2006). 10.1021/bi051952q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhrs T., Ritter C., Adrian M., Loher D. R., Bohrmann B., Dobeli H., Schubert D., and Riek R., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17342 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0506723102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma B. and Nussinov R., Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10, 445 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teplow D. B., Lazo N. D., Bitan G., Bernstein S., Wyttenbach T., Bowers M. T., Baumketner A., Shea J. -E., Urbanc B., Cruz L., Borreguero J., and Stanley H. E., Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 635 (2006). 10.1021/ar050063s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sgourakis N. G., Yan Y., McCallum S. A., Wang C., and Garcia A. E., J. Mol. Biol. 368, 1448 (2007). 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. and Teplow D. B., J. Mol. Biol. 384, 450 (2008). 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini M., Curcio R., Pappalardo M., Melki R., and Caflisch A., J. Mol. Biol. 357, 1306 (2006). 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumketner A. and Shea J. -E., J. Mol. Biol. 362, 567 (2006). 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarus B., Straub J. E., and Thirumalai D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 16159 (2006). 10.1021/ja064872y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchete N. -V. and Hummer G., Biophys. J. 92, 3032 (2007). 10.1529/biophysj.106.100404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien E. P., Okamoto Y., Straub J. E., Brooks B. R., and Thirumalai D., J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 14421 (2009). 10.1021/jp9050098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy G., Straub J. E., and Thirumalai D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 11948 (2009). 10.1073/pnas.0902473106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., Derreumaux P., Guo Z., Mousseau N., and Wei G., Proteins 75, 954 (2009). 10.1002/prot.22305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellesia G. and Shea J. -E., Biophys. J. 96, 875 (2009). 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T. and Klimov D. K., Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 77, 1 (2009). 10.1002/prot.22406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P., Nandel F. S., and Hansmann U. H. E., J. Chem. Phys. 129, 195102 (2008). 10.1063/1.3021062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B., Cruz L., Yun S., Buldyrev S. V., Bitan G., Teplow D. B., and Stanley H. E., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17345 (2004). 10.1073/pnas.0408153101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks B. R., Bruccoler R. E., Olafson B. D., States D. J., Swaminathan S., and Karplus M., J. Comput. Chem. 4, 187 (1983). 10.1002/jcc.540040211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara P., Apostolakis J., and Caflisch A., Proteins 46, 24 (2002). 10.1002/prot.10001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T. and Klimov D. K., Biophys. J. 96, 4428 (2009). 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T. and Klimov D. K., J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6692 (2009). 10.1021/jp9016773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T. and Klimov D. K., J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 11848 (2009). 10.1021/jp904070w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L., Shao H., Zhang Y., Li H., Menon N. K., Neuhaus E. B., Brewer J. M., Byeon I. -J. L., Ray D. G., Vitek M. P., Iwashita T., Makula R. A., Przybyla A. B., and Zagorski M. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1992 (2004). 10.1021/ja036813f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara P. and Caflisch A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 10780 (2000). 10.1073/pnas.190324897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiltpold A., Ferrara P., Gsponer J., and Caflisch A., J. Phys. Chem. B 104, 10080 (2000). 10.1021/jp002207k [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini M., Rao F., Seeber M., and Caflisch A., J. Chem. Phys. 121, 10748 (2004). 10.1063/1.1809588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T. and Klimov D. K., Biophys. J. 96, 442 (2009). 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See supplementary material at http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3447894 for the applicability of implicit solvent model and REMD convergence.

- Paravastu A. K., Petkova A. T., and Tycko R., Biophys. J. 90, 4618 (2006). 10.1529/biophysj.105.076927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y. and Okamoto Y., Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 141 (1999). 10.1016/S0009-2614(99)01123-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. D., Geselowitz A. R., Lesser G. J., Lee R. H., and Zehfus M. H., Science 229, 834 (1985). 10.1126/science.4023714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrenberg A. M. and Swendsen R. H., Phys. Rev. Lett. 63, 1195 (1989). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau L. D. and Lifshitz E. M., “Course of Theoretical Physics,” Statistical Physics (Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 1984), Vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Grosberg A. Y. and Khokhlov A. R., Statistical Physics of Macromolecules (AIP, Woodbury, 1994). [Google Scholar]

- Cule D. and Hwa T., Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 2375 (1997). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.79.2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zocchi G., Omerzu A., Kuriabova T., Rudnick J., and Gruner G., e-print arXiv:cond-mat/0304567v1 (2003).

- Melquiond A., Dong X., Mousseau N., and Derreumaux P., Curr. Alzh. Res. 5, 244 (2008). 10.2174/156720508784533330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanc B., Betnel M., Cruz L., Bitan G., and Teplow D. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 4266 (2010). 10.1021/ja9096303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maji S. K., Ogorzalek R. R., Inayathullah M., Spring S. M., Vollers S. S., Condron M. M., Bitan G., Loo J. A., and Teplow D. B., J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23580 (2009). 10.1074/jbc.M109.038133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., and Ferrin T. E., J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605 (2004). 10.1002/jcc.20084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]