Summary

Background

The expression levels of the clotting initiator protein Tissue Factor (TF) correlates with vessel density and the histological malignancy grade of glioma patients. Increased procoagulant tonus in high grade tumors (glioblastomas) also indicate a potential role for TF in progression of this disease, and suggest that anticoagulants could be used as adjuvants for its treatment.

Objectives

We hypothesized that blocking of TF activity with the tick anticoagulant Ixolaris might interfere with glioblastoma progression.

Methods and results

TF was identified in U87-MG cells by flow-cytometric and functional assays (extrinsic tenase). In addition, flow-cytometric analysis demonstrated the exposure of phosphatidylserine in the surface of U87-MG cells which supported the assembly of intrinsic tenase (FIXa/FVIIIa/FX) and prothrombinase (FVa/FXa/prothrombin) complexes, accounting for the production of FXa and thrombin, respectively. Ixolaris effectively blocked the in vitro TF-dependent procoagulant activity of U87-MG human glioblastoma cell line and attenuated multimolecular coagulation complexes assembly. Notably, Ixolaris inhibited in vivo tumorigenic potential of U87-MG cells in nude mice, without observable bleeding. This inhibitory effect of Ixolaris on tumor growth was associated with downregulation of VEGF and reduced tumor vascularization.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that Ixolaris might be a promising agent for anti-tumor therapy of human glioblastoma.

Keywords: Tissue factor, glioblastoma, primary tumor growth, angiogenesis, Ixolaris, anticoagulant therapy

Introduction

Vessel wall injury leads to exposure of membrane-bound tissue factor (TF), which is a crucial step in the initiation of blood coagulation [1]. TF functions as a cofactor for blood coagulation factor VIIa (FVIIa), and the resultant binary FVIIa/TF complex then generates FIXa and FXa. Generation of FIXa by the FVIIa/TF complex results in formation of the tenase complex, following binding to the nonenzymatic co-factor, activated FVIIIa. The tenase complex, along with FVIIa/TF, converts FX to FXa, which assembles with FVa into the prothrombinase complex that is directly responsible for the formation of thrombin [2,3].

Constitutive tissue distribution of TF is highly heterogeneous [4] and its induced and/or deregulated expression has been related to a number of pathological processes [5,6]. Abnormal elevated TF expression has been well documented in several tumor types, seeming to be directly correlated with thromboembolic complications in cancer patients [7,8]. Moreover, studies employing cultured cells as well as patients’ specimens have demonstrated strong correlation between TF expression and aggressive tumor behaviour [9–12]. In particular, TF expression correlates with an unbalanced production of anti- and/or proangiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), thus favouring increased tumor vascularity [13–16].

Pro-tumoral effects of TF and blood clotting enzymes (FVIIa, FXa and thrombin) are intimately related to a group of G protein-coupled receptors named Protease Activated Receptors (PARs). In fact, activation of PARs in cancer cells elicits a vast number of cellular responses, which include migration, invasion, proliferation, metastasis, inhibition of apoptosis, and production of several pro-aggressive factors such as VEGF, interleukin-8 (IL-8), metalloproteases and others [17–18].

Malignant gliomas are very aggressive cancers, displaying high rates of mortality (within months) and resistance to therapeutic interventions [19]. As observed with other cancer types, studies performed with human surgical samples demonstrated that the levels of TF expression correlate with the histological grade of malignancy and vascularity [10–11]. Most remarkable, TF is overexpressed around the typical necrotic foci found in glioblastoma [20]. These regions are highly hypoxic and seem to play a key role in glioblastoma aggressiveness, presenting an increased production of VEGF, IL-8 and metalloproteases [21–22].

Given the importance of coagulation activation in human gliomas, it has been proposed that TF, as well as other clotting proteins, could serve as therapeutic targets [23]. Ixolaris, a tick salivary 140 amino acid protein containing 10 cysteines and 2 Kunitz-like domains, binds to FXa or FX as scaffolds for inhibition of TF/FVIIa complex, in which FVIIa catalytic site is inactivated, as previously demonstrated by inhibition of either synthetic or macromolecular – FX and FIX – substrates [24]. In contrast to TFPI [25], however, Ixolaris does not bind to the active site cleft of FXa. Instead, complex formation is mediated by the FXa heparin-binding exosite [26]. In addition, Ixolaris interacts with zymogen FX through a precursor state of the heparin-binding exosite [27]. Since Ixolaris displays potent and long-lasting antithrombotic activity [28], we hypothesized that this molecule might interfere with glioblastoma progression. In this study, we demonstrate that Ixolaris presents potent activity against the in vitro procoagulant properties and the in vivo tumor growth of U87-MG glioblastoma cells. Notably, inhibition of tumor growth was accompanied by downregulation of VEGF and vessel density in tumor mass. Our results provide strong evidence that TF may be regarded as an important therapeutic target for glioblastoma.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Recombinant Ixolaris was produced in High Five insect cells (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), purified, and quantified as previously described [28]. Human thrombin and prothrombin were purified following previously reported procedures [29]. FXa was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Human FVa, FX, dansyl-Glu-Gly-Arg (DEGR)-FVIIa and placental annexin V were purchased from Haematologic Technologies (Essex Junction, VT). Human FIXa and FVIIa were purchased from American Diagnostica (Greenwich, CT). Human FVIII (Advate) was from Baxter Healthcare Corporation (Westlake Village, CA). FVIII was activated with human thrombin. Chromogenic substrates for FXa (S-2765, n-α-benzyloxycarbonyl-d-Arg-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide) and thrombin (H-d-phenylalanyl-L-pipecolyl-L-argininep-nitroaniline dihydrochloride, S-2238) were purchased from Diapharma (Westchester, OH).

Cell culture

The human glioblastoma cell line, U87-MG, was grown at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere in culture flasks, by subconfluent passages in Dulbecco´s Modified Eagle Medium – DMEM-F12 (GibcoBRL) supplemented with 2 g/L HEPES, 60 mg/L penicillin, 100 mg/L streptomycin, 1.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate. Subconfluent cultures were washed twice with PBS, and cells were detached with Hank’s solution containing 10 mM HEPES and 0.2 mM EDTA, spun at 350 × g for 7 min, resuspended in supplemented DMEM-F12 and transferred at a 1:10 ratio to another culture flask. In all experiments, cells were resuspended in phosphate buffer-saline (PBS).

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells grown in culture were resuspended in phosphate buffered saline containing 0.1% BSA and incubated for 15 min, at 4 °C, with murine monoclonal antibodies against human TF (4503, American Diagnostica, Stamford, CT, USA). After washing to remove unbound antibody, cells were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cells were washed again and analyzed using a FACScalibur (Becton-Dickinson, San José, CA). Data were analyzed using the WinMDI 2.8 version software.

For surface phosphatidylserine detection, U87-MG cells were resuspended in 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.3 (annexin binding buffer) and incubated with 25 µg/mL annexin V-FITC (Molecular Probes) for 15 min at room temperature. U87-MG cells were also labeled with 10 µg/mL propidium iodide (PI) for exclusion of those which had lost plasma membrane integrity, thus becoming PI permeable.

Factor Xa generation assays

Activation of FX to FXa by FVIIa was performed as described [30] in 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 mg/mL BSA, pH 7.5 (HEPES-BSA buffer), as follows: FVIIa (1 nM) was incubated for different time periods, at 37 °C, with U87-MG cells (5 × 105/mL) in the presence of 100 nM FX. After addition of 50 µL of 300 µM S-2765, prepared in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mg/mL PEG 6,000, pH 7.5 (Tris-EDTA buffer), absorbance at 405 nm was recorded, at 37°C, for 20 min at 6-s intervals using a Thermomax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, CA, USA) equipped with a microplate mixer and heating system. Velocities (mOD/min) obtained in the first minutes of reaction were used to calculate the amount of FXa formed. Controls performed in the absence of cells or in the absence of FVIIa showed no significant FXa formation. The inhibitory effect of Ixolaris was evaluated by pre-incubating FX with varying amounts of the inhibitor (0–10 nM) for 10 min, at 37°C, prior to adding it to FVIIa (1 nM) and U87-MG cells (5 × 105/mL). FXa formed in the absence of Ixolaris was taken as 100%.

Activation of FX to FXa by FIXa was performed in HEPES-BSA buffer, using a previously described discontinuous assay [31]. FIXa (0.2 nM, final concentration) was incubated with FVIIIa (4 IU/mL, final concentration) in the presence of U87-MG cells (5 × 105/mL) for 5 min at 37°C. Reaction was initiated by addition of FX (100 nM, final concentration) and aliquots of 25 µL were removed every 2 min and placed into microplate wells containing 25 µL of Tris-EDTA buffer. After addition of 50 µL of 200 µM S-2765 prepared in Tris-EDTA buffer, absorbance at 405 nm was recorded, at 37°C, for 20 min at 6s intervals as described above. Negative controls were performed in the absence of cells or in the absence of FVIIIa, showing no significant FXa formation. In some cases, FX was previously incubated with varying amounts (0–100 nM) of Ixolaris for 10 min, at 37°C, and FXa formed in the absence of the inhibitor was taken as 100 %.

Thrombin generation assay

Activation of prothrombin by the prothrombinase complex (FXa/FVa) was performed in HEPES-BSA buffer, using a discontinuous assay [31]. FXa (10 pM, final concentration) was incubated with FVa (1 nM, final concentrations) in the presence of U87-MG cells (5 × 105/mL) for 2 min at 37°C. Reaction was initiated by the addition of prothrombin (0.5 µM, final concentration) and aliquots of 10 µL were removed every 1 min into microplate wells containing 25 µL of Tris-EDTA buffer. After addition of 50 µL of 400 µM S-2238 prepared in Tris-EDTA buffer, absorbance at 405 nm was recorded, at 37°C, for 20 min at 6s intervals using a Thermomax Microplate Reader. Velocities (mOD/min) obtained in the first minutes of reaction were used to calculate the amount of thrombin formed. Negative controls were carried out in the absence of cells or in the absence of FVa, showing no significant thrombin formation. Inhibitory effects of Ixolaris upon the prothrombinase complex was tested by pre-incubating FXa with varying amounts of Ixolaris (0–4 nM) for 10 min, at 37°C, in HEPES-BSA buffer.

Inhibition of coagulant complexes by annexin V

The effect of annexin V on thrombin or FXa formation was tested as follows: U87-MG cells (5 × 105/mL) were incubated with varying amounts of annexin V (0–25 nM) for 5 min at 37°C in HEPES-BSA buffer. Cells were then incubated with either FXa (10 pM)/prothrombin (0.5 µM), or FIXa (0.2 nM)/FX (100 nM) followed by the addition of FVa (1 nM) or FVIIIa (4 IU/mL), respectively. Aliquots of 25 µL were removed after 2 min, and delivered to microplate wells containing 25 µL of Tris-EDTA buffer. The amount of FXa or thrombin formed was evaluated as described above, using S-2238 or S-2765, respectively.

Procoagulant activity measured by recalcification time

The ability of U87-MG glioblastoma cells to potentiate plasma coagulation was assessed by measuring the recalcification time on an Amelung KC4A coagulometer (Labcon, Heppenheim, Germany) using plastic tubes. Human blood samples were collected from healthy donors in 3.8% trisodium citrate (9:1, v/v), and platelet-poor plasma were obtained by further centrifugation at 2,000×g for 10 min. Plasma was incubated with 50 µL of U87-MG glioblastoma cells at various concentrations (suspension in TBS buffer) for 1 min at 37 °C. Plasma clotting was initiated by the addition of 100 µL of 12.5 mM CaCl2 and the time for clot formation was then recorded. In some cases, cells were previously incubated with the inactivated form of FVIIa, DEGR-FVIIa, for 10 min at room temperature. The in vitro effect of Ixolaris on U87-MG-induced coagulation was evaluated using the following procedure: plasma (50 µl) was incubated with Ixolaris (10 µl) for 10 min at 37°C, followed by the addition of 100 µL of 12.5 mM CaCl2.

Tumor growth assay

U87-MG cells (2 × 106) were subcutaneously inoculated into the flank of 6 week-old, male Balb/C nude mice (Chemistry Institute Animal Room, São Paulo University, São Paulo, Brazil). Treatment with Ixolaris (diluted in PBS, 100 µL final volume) was initiated 3 days after tumor cell inoculation and continued daily for 17 days. Control animals received PBS instead of the inhibitor. Treatment was performed by subcutaneous administration into the flank, preferentially at distant sites from tumor inoculation. Tumor growth was evaluated for 20 days with calipers, and the volume was calculated using the equation: (length) × (width)2 × (π/6). Preliminary analysis showed macroscopic necrotic areas in some control animals after 20 days of cell inoculation. Tumor weight was determined at the time of sacrifice. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to establish differences between groups, and significance levels were determined by nonparametric Mann Whitney test. Animal experiments were performed under approved protocols of the institutional animal use and care committee.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcriptase Real-Time PCR

Tumor RNA was isolated using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). After cDNA synthesis using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), mRNA levels were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on a GeneAmp 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) using SYBR Green Master mix and sequence-specific primers designed using Primer Express 3 (Applied Biosystems). Primers used were: VEGF (F: 5’-AGTGGTGAAGTTCATGGATGT-3’, R: 5’-GCACACAGGATGGCTTGAAGA-3’) and GAPDH (F: 5’- CCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGA-3’, R: 5’-CTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCGT-3’).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue staining was performed on paraffin-embedded sections (4-µm thick) which were incubated overnight, following heat antigen retrieval, with primary antibodies: monoclonal anti-mouse endoglin (CD105) antibody (MAB-1320, R&D Systems, USA) at 1:20 dilution, or monoclonal antibody against VEGF (SC-7269, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:100 dilution. In order to reduce nonspecific antibody binding, sections were incubated with PBS containing 10% nonimmune goat serum, 5% BSA and 10% fetal bovine serum for 30 min prior to incubation with primary antibodies. Sections were further revealed using LSAB2 Kit, HRP (Dako-Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA) with diaminobenzidine (3, 3’-diaminobenzidine tablets; Sigma Chemical Co, St. Louis, MO) as the chromogen and counterstained with hematoxylin. Negative control slides consisted of sections incubated with antibody vehicle or nonimmune rat or mouse serum. Ten fields of immunostained section (CD105 and VEGF) were chosen at random and captured from each specimen. Quantification was assessed on captured high-quality images (2048 × 1536 pixels buffer) using the Image Pro Plus 4.5.1 (Media Cybernetics, Silver spring, MD). Data were stored in Adobe Photoshop, version 3.0, to enable uneven illumination and background color to be corrected. The number of transversal sections of CD105 was counted, and these numbers per square millimeter of the tumor were calculated, as previously described [32]. A semiquantitative evaluation of immunohistochemical staining for VEGF was performed as described [32]. Statistical analyses comparing control and treatment groups used the one-way ANOVA. Values of p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

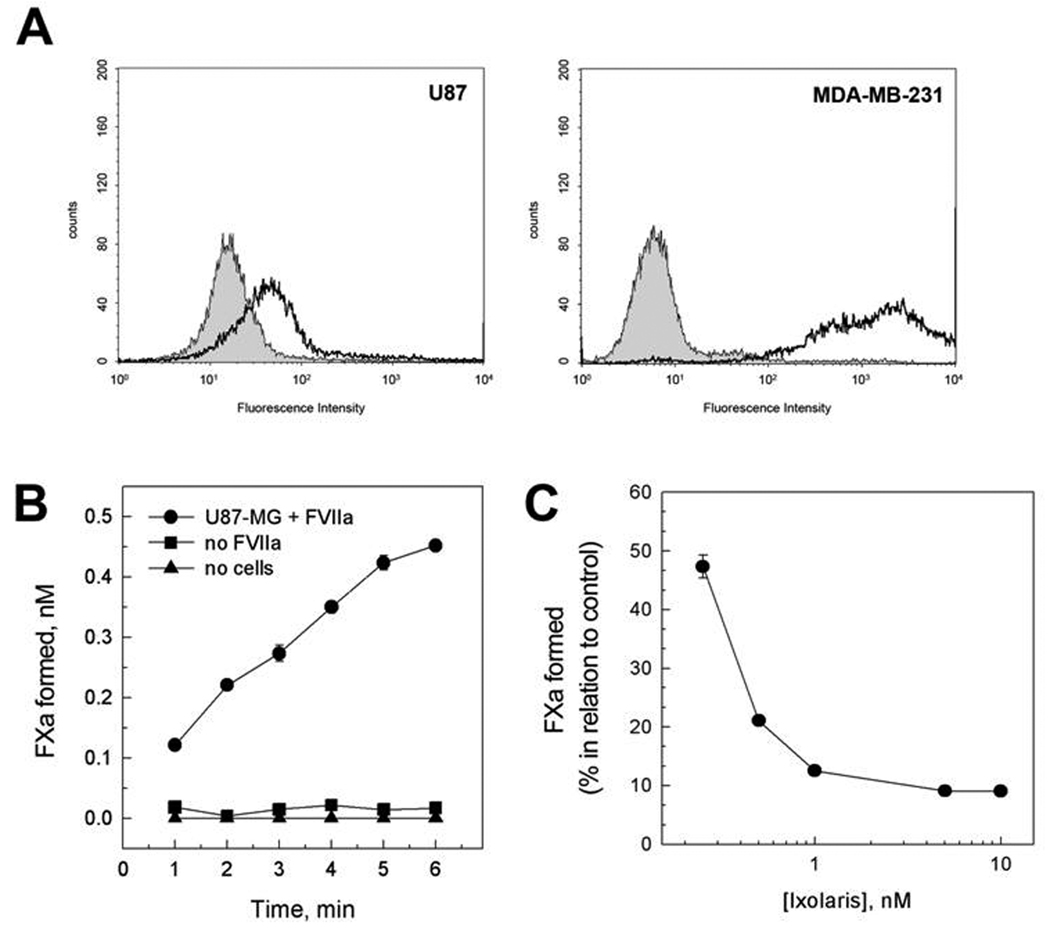

Previous studies employing the U87-MG human glioma cell line have demonstrated constitutive expression of the clotting initiator protein tissue factor (TF) [20,33]. Accordingly, Fig. 1A (left) demonstrates positive staining for TF on U87-MG cells, as assessed by flow-cytometric analysis. In fact, comparison with the human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231(Fig 1A, right) showed that U87-MG express moderate levels of TF. Further enzymatic assays showed that the TF expressed on U87-MG cells is functional. Fig. 1B shows that FXa formation was both cell- and FVIIa-dependent, indicating the formation of the FVIIa/TF complex (extrinsic tenase complex).

Figure 1.

Functional TF expressed by U87-MG cells is inhibited by Ixolaris. (A) Expression of TF on U87-MG (left) and MDA-MB-231 (right) cells was evaluated by flow-cytometric analysis. Dashed line represents staining with monoclonal anti-human TF antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Grey region represents control in the absence of primary antibody. (B) Assembly of extrinsic tenase complex on U87-MG cells. Kinetics for the activation of FX (100 nM) in the presence of FVIIa (1 nM) and U87-MG cells (5 × 105 /mL) (●). Controls were performed in the presence of cells (5 × 105 /mL) and absence of FVIIa (■) or in the absence of cells and presence of FVIIa (1 nM) (▲). (C) Inhibitory effect of Ixolaris. FX (100 nM) was incubated for 5 min with the indicated concentrations of Ixolaris prior to activation by FVIIa (1 nM) and U87-MG cells (5 × 105 /mL). The conditions for the assays and for quantification of Xa are described in the Materials and Methods section. Each point represents mean ± SD of three determinations.

Ixolaris is a potent inhibitor of FVIIa/TF complex that blocks FXa formation by forming a quaternary FVIIa/TF/FX/Ixolaris complex in which the FVIIa catalytic site is inactivated [24]. Therefore, we next determined whether Ixolaris inhibits the extrinsic tenase complex assembled on U87-MG cells. As shown in Fig. 1C, Ixolaris efficiently decreased FXa formation in this cell-based system.

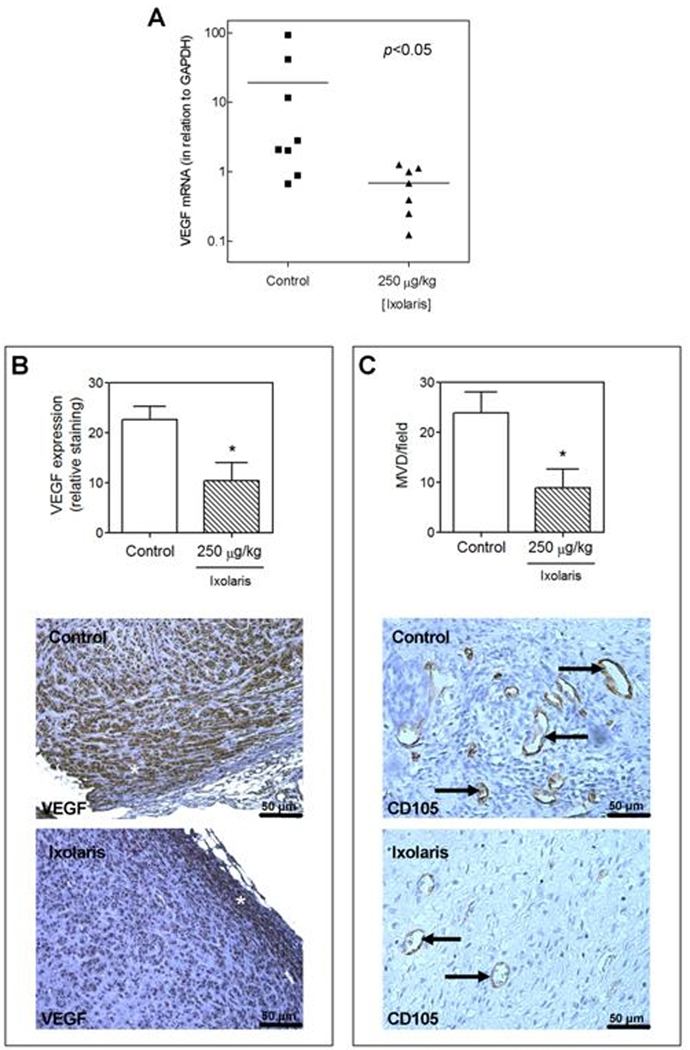

Previous studies demonstrate that viable tumor cells may expose the anionic phospholipid phosphatidylserine (PS) at the outer leaflet of the cell membrane [31,34]. This ability allows an alternative pathway for activation of FX through assembly of the intrinsic tenase complex, i.e. FIXa, FVIIIa and PS-containing membranes. The presence of PS on the surface of U87-MG cells was demonstrated by flow cytometric assays using annexin-V-FITC (Fig. 2A) and specific anti-PS antibodies (data not show). This indicates that U87-MG cells normally expose PS on their surface. We further investigated the ability of tumor cells to promote FX activation through assembly of the intrinsic tenase complex. Fig. 2B shows that zymogen activation was both cell- and FVIIIa-dependent. Thus, U87-MG glioma cells support the formation of the intrinsic tenase complex.

Figure 2.

Ixolaris inhibits PS-dependent procoagulant complexes assembled on U87-MG cells. Assembly of PS-dependent procoagulant complexes on U87-MG cells. (A) PS exposure on U87-MG was evaluated by flow-cytometric analysis of annexin V binding to cells. Dashed line represent staining with FITC-labeled annexin V. Grey region represents control performed in the absence of annexin V. (B) Assembly of intrinsic tenase complex on U87-MG cells. Kinetics for the activation of FX (100 nM) in the presence of FIXa (0.2 nM), FVIIIa (4 IU/mL) and (●) U87-MG cells (5 × 105 /mL). Controls were performed in the absence of cells (○). Assay conditions and quantification of Xa are described in the Materials and Methods section. Each point represents mean ± SD of three determinations. (C) Prothrombinase complex assembly on U87-MG cells. (A) Kinetics for the activation of prothrombin (0.5 µM) in the presence of FXa (10 pM), FVa (1 nM) and U87-MG cells (5 × 105 cells/mL) (■). Controls were performed in the absence of cells (□). Assay conditions and quantification of thrombin are described in the Materials and Methods section. Each point represents mean ± SD of three determinations. (D) Inhibitory effect of annexin V on FX (●) or prothrombin activation (■). U87-MG cells (5 × 105 /mL) were incubated with the indicated concentrations of annexin V prior to addition of either FXa (10 pM)/ prothrombin (0.5 µM) or FIXa (0.2 nM)/FX (100 nM) followed by addition of FVa (1 nM) or FVIIIa (4 IU/mL), respectively. Zymogen activation rates in the absence of annexin V were taken as 100%. Assay conditions are described in the Materials and Methods section. Each point represents mean ± SD of three determinations. (E) Activation of FX (100 nM) by FIXa (0.2 nM), FVIIIa (4 U/mL) and U87-MG cells (5 × 105 /mL) was assayed at the indicated concentrations of Ixolaris. (F) Prothrombin (0.5 µM) activation by FXa (10 pM) in the presence of FVa (1 nM) and U87-MG cells (5 × 105 /mL) was assayed at the indicated concentrations of Ixolaris. Assay conditions are described in the Materials and Methods section. Each point represents mean ± SD of three determinations.

Assembly of the prothrombinase complex on tumor cells is also supported by PS exposure [31,35]. Accordingly, Fig 2C shows that U87-MG cells potentiate prothrombin activation in the presence of FXa and Factor Va, its protein cofactor. On the other hand, no thrombin formation has been observed in the absence of cells or in the absence of FVa. These data are consistent with the assembly of the prothrombinase complex on U87-MG cells. Contribution of tumor cell PS for either FXa or thrombin formation was reinforced by the observation that increasing annexin V concentrations progressively decreased zymogen conversion by their respective U87-MG-assembled activating complexes (Fig. 2D).

It has been demonstrated that binding of Ixolaris to FX decreases the zymogen recognition by the intrinsic tenase complex, as demonstrated in a purified system [27]. Similarly, increasing Ixolaris concentrations reduced FXa formation by U87-MG-assembled intrinsic complex (Fig. 2E). Remarkably, effective Ixolaris concentrations in this assay are correlated with zymogen concentration and are expected to be much higher than that required to inhibit FVIIa/TF complex.

Binding of Ixolaris to FXa occurs through a specific heparin-binding region in the enzyme that is crucial for prothrombinase complex activity [26]. Therefore, Ixolaris progressively decreased thrombin formation by U87-MG-assembled prothrombinase complex, as observed in Fig 2F.

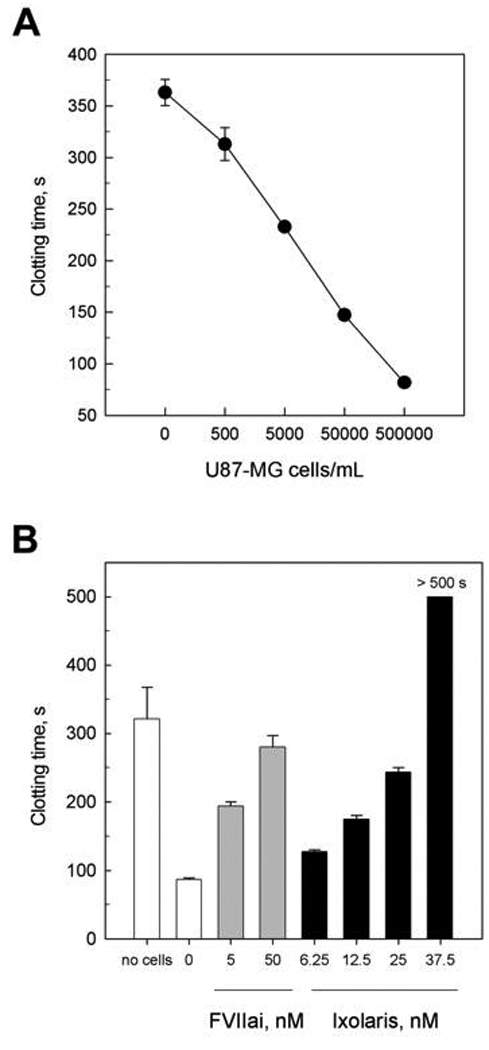

Since U87-MG cells contain the main components to initiate (TF) and to propagate (a PS-containing membrane) blood clotting in a highly efficient manner, we further tested the effect of these cells on human plasma clotting. As depicted in Fig. 3A, increasing cell concentrations dramatically accelerate the coagulation time, demonstrating that these cells display potent procoagulant activity. However, TF seems to be critical for this ability, since DEGR-FVIIa, which acts as a specific TF/FVIIa inhibitor, completely reversed U87 procoagulant activity (Fig. 3B, grey bars). We further examined the ability of Ixolaris to inhibit the tumor-dependent procoagulant activity. As expected, Ixolaris efficiently reversed tumor-induced plasma coagulation (Fig. 3B, black bars).

Figure 3.

Procoagulant activity of U87-MG cells is reversed by Ixolaris. (A) U87-MG cells (in PBS) at the indicated concentrations were incubated with human plasma followed by recalcification with 12.5 mM CaCl2. Each point represents mean ± SD of three assays. (B) Human plasma was incubated for 5 min with the indicated concentrations of DEGR-FVIIa (FVIIai, grey bars) or Ixolaris (black bars) prior to addition of U87-MG cells (5 × 105 cells) followed by recalcification with 12.5 mM CaCl2. Each point represents mean ± SD of three assays.

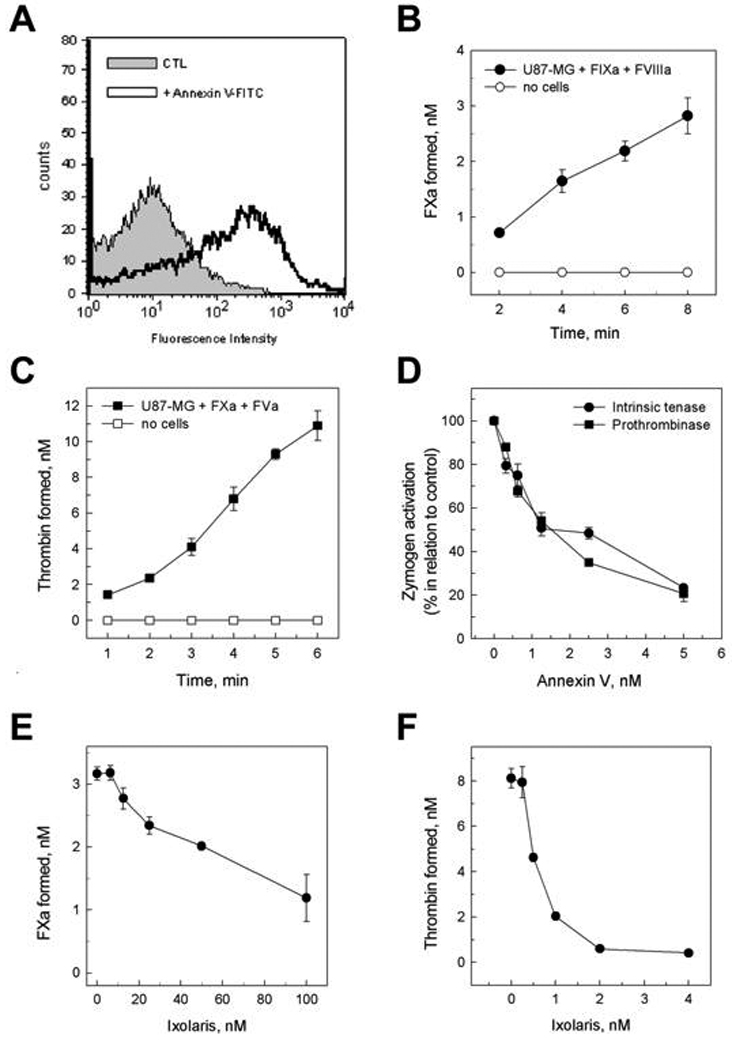

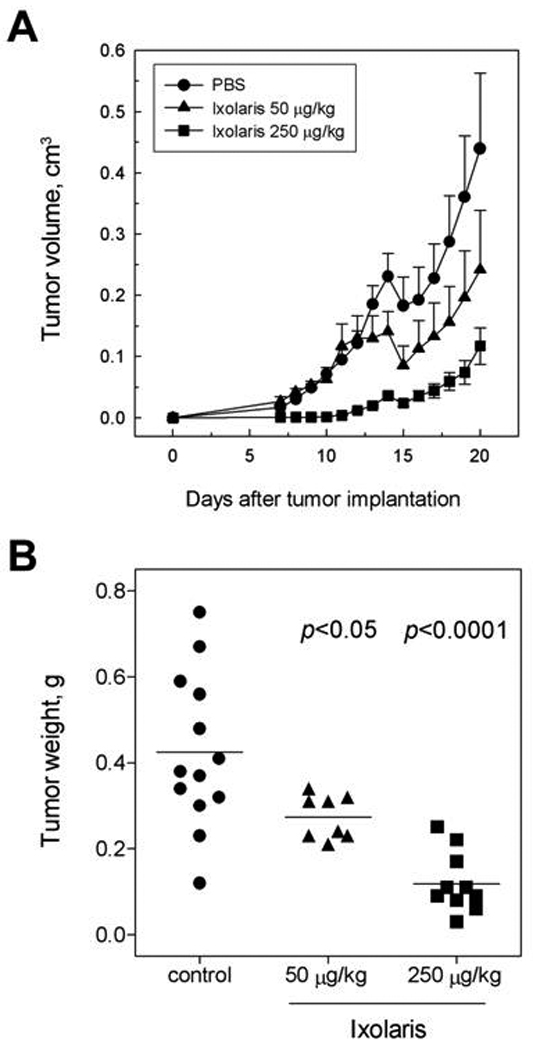

It has been demonstrated that coagulation inhibitors targeting the FVIIa/TF complex reduce primary tumor growth and tumor vessel density [36–37]. In this context, we next examined the ability of Ixolaris to interfere with in vivo U87-MG growth using a xenograft model in nude mice. As may be seen in Fig. 4, treatment with Ixolaris decreased tumor growth progression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig 4A) with significant reduction in tumor weight in animals treated with either 50 or 250 µg/kg (Fig 4B). In vitro assays for cell proliferation and viability showed no direct toxic effect of Ixolaris to tumor cells (data not shown). In addition, no bleeding has been observed in controls or tumor-bearing animals treated for up to 30 or 20 days, respectively, with both Ixolaris doses (data not shown). Remarkably, the antitumor effect of Ixolaris was accompanied by a significant decrease in the VEGF mRNA levels within tumors (Fig 5A). Further immunohistochemistry analysis confirmed that treatment with Ixolaris downregulates VEGF expression (Fig 5B). Therefore immunohistochemistry analysis also confirmed that treatment with Ixolaris reduces tumor vessel density, as assessed by CD105 staining (Fig 5C).

Figure 4.

Ixolaris inhibits in vivo primary tumor growth in a xenograft model. U87-MG cells were injected s.c. in nude mice. Treatment with Ixolaris was initiated three days after tumor cell inoculation; control animals were treated with an equivalent volume of PBS. A. Tumor size was measured at the indicated days. Each point represents mean ± SD. B. After 20 days of tumor cell inoculation, animals were sacrificed and tumors were removed and weighed.

Figure 5.

Treatment with Ixolaris decreases tumor angiogenesis. A. RNA was extracted from tumors obtained from experiments depicted on Fig. 4B and further analyzed for VEGF expression using RT-PCR, as described in the Material and Methods section. B. Bar graph shows decreased VEGF expression in Ixolaris-treated animals (n=5; 10.4 ± 3.6) than in PBS-treated controls (n=5; 22.7 ± 2.6). VEGF staining (asterisk) and quantification was performed as described in the materials and methods section. C. Bar graph shows that there are fewer blood vessels in Ixolaris-treated animals (n=5; 8.9 ± 3.7) than in PBS-treated controls (n=5; 23.9 ± 4.2). Vessel density was evaluated in CD105-stained tumor sections (arrows) as described in the materials and methods section. Values of p<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All values are given as mean ± SD.

Discussion

It is hypothesized that targeting the blood clotting cascade represents a feasible therapeutic approach for treatment of glioblastoma [23]. Here we demonstrate for the first time that Ixolaris, a potent exogenous TF inhibitor, blocks the in vivo growth of human glioblastoma (U87-MG) cells in a xenograft model. This phenomenon was accompanied by a significant decrease in VEGF expression as well as diminished tumor angiogenesis.

Our data shows that Ixolaris is highly efficient to inhibit U87-MG-assembled extrinsic tenase complex. Therefore, the antitumor effect of Ixolaris is likely attributable to the suppression of tumor-associated FVIIa/TF complex activity. This is supported by other studies showing that: a) xenograft models employing a specific anti-human TF showed that suppression of tumor- but not host-derived TF coagulant activity is sufficient to impair primary tumor growth [36,38]; b) low-TF mice exhibit unaltered growth of TF-expressing tumor cell lines, as compared to wild-type mice [39]. Most remarkable, tumor progression is also impaired by a TF-directed monoclonal antibody that specifically suppresses PAR-2-mediated signaling in tumor cells without affecting FVIIa/TF complex-mediated coagulation [40]. It has been clearly demonstrated that Ixolaris blocks FVIIa catalytic site [24] and therefore it possibly suppresses FVIIa/TF complex-mediated signaling in addition to its anticoagulant function on tumor cells.

Our in vitro data demonstrate that, in addition to FVIIa/TF complex, Ixolaris inhibits PS-dependent coagulation complexes assembled on U87-MG cells, through interaction with FX or FXa. Therefore, inhibition of thrombin formation by the prothrombinase might also contribute to the antitumor activity of Ixolaris. In this regard, it has been demonstrated that argatroban, a specific thrombin inhibitor, reduces in vivo growth of rat glioblastoma although displaying modest survival improvement [41]. At this point, it is possible that therapies targeting multiple coagulation steps, including the FVIIa/TF complex, may offer better results. In the case of Ixolaris, further studies employing an orthotopic model (intracerebral administration of tumor cells) may reinforce this hypothesis. This model will be also important to evaluate the risk for intracranial bleeding, which is an important side-effect of the antithrombotic therapy in glioma patients [42].

There is high incidence of thrombotic events throughout the course of malignant glioma [43]. More recently, tumoral intravascular thrombosis was reported as a distinguishing feature between glioblastoma – the most aggressive primary brain tumor - and lower grade astrocytomas [44]. In fact, the prothrombotic properties of glioblastoma cells seem to contribute to the appearance of hypoxic regions within the tumor [21] and, ultimately, to the formation of necrotic foci that are well-recognized predictors of poor prognosis [45]. This hypothesis is supported by the observation that: a) exposure of human glioma cell lines to hypoxia markedly increases TF expression resulting in higher procoagulant activity [20]; b) patients’ specimens show increased TF expression is cells surrounding the necrotic foci (“pseudopalisading” cells) [20]. Herein it is demonstrated that the human U87-MG glioblastoma cell line also displays TF and PS on their surface, resulting in high procoagulant activity in vitro. Notably, TF is determinant for the in vitro coagulant activity of U87-MG cells. However it is possible that in the tumor microenvironment context, PS contributes in vivo for the elevated occurrence of intra-tumoral thrombosis in high-grade gliomas.

Vaso-occlusive and prothrombotic mechanisms seem to be intimately related with tumor hypoxia, necrosis, and accelerated growth in glioblastoma [21]. In fact, intense angiogenesis is a distinguishing pathological hallmark of glioblastomas relative to lower-grade gliomas. Actually, glioblastomas are of the most highly vascularized malignant tumors and there is strong evidence that VEGF plays a key role in this process [46]. In this regard, our data shows that inhibition of glioblastoma growth by Ixolaris is accompanied by a significant downregulation of VEGF and angiogenesis in tumor mass. Given the known antithrombotic properties of Ixolaris [28], it is possible that suppression of angiogenesis derives at least in part, from reduction of intratumoral thrombosis, which could in turn decrease the hypoxic regions within tumor mass and hypoxia-driven VEGF production. In addition, other tumor models demonstrate decreased angiogenesis upon inhibition of TF, including carcinoma [36], colorectal [37] and breast cancer [38,40], and melanoma [47].

The involvement of TF on tumor angiogenesis might be coupled to activation of Protease-activated receptors (PARs) by coagulation enzymes generated in the tumor microenvironment [17–18]. Binding of FVIIa to TF-expressing tumor cells may elicit signal transduction through PAR-2 activation followed by upregulation in VEGF expression [50]. In fact, it has been recently demonstrated that PAR-2 contributes for the angiogenic switch during mammary tumor development [51]. On the other hand, Yin et al. have demonstrated that PAR-1 mediates angiogenesis, through VEGF production, in carcinoma and melanoma models [52]. In addition, thrombin-mediated activation of PAR-1 in U87-MG cells increases VEGF transcription and expression [53]. Taken together, the effect of Ixolaris on tumor growth and angiogenesis may additionally result from decreased activation of PAR-1 and/or PAR-2 in U87-MG cells. This mechanism remains to be determined.

In conclusion, Ixolaris is a potent anticoagulant that does not produce major bleeding when injected subcutaneously in different animal models [28,54]. Remarkably, Ixolaris is non-immunogenic molecule (non published observations) and displays long half-life (> 24 hrs, [28]). In addition, Ixolaris is effective at 50–250 µg/kg, doses which are 2 to 3 orders of magnitude lower than other molecules affecting TF or the coagulation cascade in the context of experimental therapeutics for cancer [38,41]. Finally, Ixolaris is an angiogenesis inhibitor that effectively suppresses tumor vessel formation in vivo. Accordingly, Ixolaris may attenuate the procoagulant state of cancer patients in one hand, and prevent angiogenesis on the other thus interfering with two important components that contribute to tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Luize G. Lima for helpful discussion and technical support; Dr. Carmen Nogueira (HUCFF/UFRJ, RJ, Brazil) for providing the human plasma samples; Ana Lúcia O. Carvalho, Angélica Dutra de Oliveira, Zizi de Mendonça, Sandra Regina de Souza, Débora Cristina da Costa and Ricardo Krett de Oliveira for technical assistance. This research was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro Carlos Chagas Filho (FAPERJ), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Financiadora de Estudos e Projetos (FINEP).

References

- 1.Gomez K, McVey JH. Tissue factor initiated blood coagulation. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1349–1359. doi: 10.2741/1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalafatis M, Swords NA, Rand MD, Mann KG. Membrane-dependent reactions in blood coagulation: role of the vitamin K-dependent enzyme complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1227:113–129. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monroe DM, Hoffman M, Roberts HR. Platelets and thrombin generation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1381–1389. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000031340.68494.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Østerud B, Bjørklid E. Sources of tissue factor. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32:11–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruf W, Edgington TS. Structural biology of tissue factor, the initiator of thrombogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 1994;8:385–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Francischetti IM, Seydel KB, Monteiro RQ. Blood coagulation, inflammation, and malaria. Microcirculation. 2008;15:81–107. doi: 10.1080/10739680701451516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buller HR, van Doormaal FF, van Sluis GL, Kamphuisen PW. Cancer and thrombosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical presentations. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5 Suppl 1:246–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwicker JI, Furie BC, Furie B. Cancer-associated thrombosis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;62:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kakkar AK, Lemoine NR, Scully MF, Tebbutt S, Williamson RC. Tissue factor expression correlates with histological grade in human pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1101–1104. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800820831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamada K, Kuratsu J, Saitoh Y, Takeshima H, Nishi T, Ushio Y. Expression of tissue factor correlates with grade of malignancy in human glioma. Cancer. 1996;77:1877–1883. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960501)77:9<1877::AID-CNCR18>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guan M, Jin J, Su B, Liu WW, Lu Y. Tissue factor expression and angiogenesis in human glioma. Clin Biochem. 2002;35:321–325. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(02)00312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakasaki T, Wada H, Shigemori C, Miki C, Gabazza EC, Nobori T, Nakamura S, Shiku H. Expression of tissue factor and vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with angiogenesis in colorectal cancer. Am J Hematol. 2002;69:247–254. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Deng Y, Luther T, Müller M, Ziegler R, Waldherr R, Stern DM, Nawroth PP. Tissue factor controls the balance of angiogenic and antiangiogenic properties of tumor cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1320–1327. doi: 10.1172/JCI117451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abe K, Shoji M, Chen J, Bierhaus A, Danave I, Micko C, Casper K, Dillehay DL, Nawroth PP, Rickles FR. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor production and angiogenesis by the cytoplasmic tail of tissue factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8663–8668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rak J, Milsom C, May L, Klement P, Yu J. Tissue factor in cancer and angiogenesis: the molecular link between genetic tumor progression, tumor neovascularization, and cancer coagulopathy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2006;32:54–70. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-933341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khorana AA, Ahrendt SA, Ryan CK, Francis CW, Hruban RH, Hu YC, Hostetter G, Harvey J, Taubman MB. Tissue factor expression, angiogenesis, and thrombosis in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2870–2875. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belting M, Ahamed J, Ruf W. Signaling of the tissue factor coagulation pathway in angiogenesis and cancer. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1545–1550. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000171155.05809.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao LV, Pendurthi UR. Tissue factor-factor VIIa signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:47–56. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000151624.45775.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behin A, Hoang-Xuan K, Carpentier AF, Delattre JY. Primary brain tumours in adults. Lancet. 2003;361:323–331. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rong Y, Post DE, Pieper RO, Durden DL, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ. PTEN and hypoxia regulate tissue factor expression and plasma coagulation by glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1406–1413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brat DJ, Van Meir EG. Vaso-occlusive and prothrombotic mechanisms associated with tumor hypoxia, necrosis, and accelerated growth in glioblastoma. Lab Invest. 2004;84:397–405. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rong Y, Durden DL, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ. 'Pseudopalisading' necrosis in glioblastoma: a familiar morphologic feature that links vascular pathology, hypoxia, and angiogenesis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:529–539. doi: 10.1097/00005072-200606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ornstein DL, Meehan KR, Zacharski LR. The coagulation system as a target for the treatment of human gliomas. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2002;28:19–28. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-20561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francischetti IM, Valenzuela JG, Andersen JF, Mather TN, Ribeiro JM. Ixolaris, a novel recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) from the salivary gland of the tick, Ixodes scapularis: identification of factor X and factor Xa as scaffolds for the inhibition of factor VIIa/tissue factor complex. Blood. 2002;99:3602–3612. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broze GJ., Jr Tissue factor pathway inhibitor and the revised theory of coagulation. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:103–112. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteiro RQ, Rezaie AR, Ribeiro JM, Francischetti IM. Ixolaris: a factor Xa heparin-binding exosite inhibitor. Biochem J. 2005;387:871–877. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monteiro RQ, Rezaie AR, Bae JS, Calvo E, Andersen JF, Francischetti IM. Ixolaris binding to factor X reveals a precursor state of factor Xa heparin-binding exosite. Protein Sci. 2008;17:146–153. doi: 10.1110/ps.073016308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nazareth RA, Tomaz LS, Ortiz-Costa S, Atella GC, Ribeiro JM, Francischetti IM, Monteiro RQ. Antithrombotic properties of Ixolaris, a potent inhibitor of the extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade. Thromb Haemost. 2006;96:7–13. doi: 10.1160/TH06-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monteiro RQ, Bock PE, Bianconi ML, Zingali RB. Characterization of bothrojaracin interaction with human prothrombin. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1897–1904. doi: 10.1110/ps.09001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geaquinto DL, Fernandes RS, Lima LG, Barja-Fidalgo C, Monteiro RQ. Procoagulant properties of human MV3 melanoma cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2008;41:99–105. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2008005000003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernandes RS, Kirszberg C, Rumjanek VM, Monteiro RQ. On the molecular mechanisms for the highly procoagulant pattern of C6 glioma cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:1546–1552. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Machado DE, Abrao MS, Berardo PT, Takiya CM, Nasciutti LE. Vascular density and distribution of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptor VEGFR-2 (Flk-1) are significantly higher in patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis affecting the rectum. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bastida E, Ordinas A, Escolar G, Jamieson GA. Tissue factor in microvesicles shed from U87MG human glioblastoma cells induces coagulation, platelet aggregation, and thrombogenesis. Blood. 1984;64:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connor J, Bucana C, Fidler IJ, Schroit AJ. Differentiation-dependent expression of phosphatidylserine in mammalian plasma membranes: quantitative assessment of outer-leaflet lipid by prothrombinase complex formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:3184–3188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.VanDeWater L, Tracy PB, Aronson D, Mann KG, Dvorak HF. Tumor cell generation of thrombin via functional prothrombinase assembly. Cancer Res. 1985;45:5521–5525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milsom CC, Yu JL, Mackman N, Micallef J, Anderson GM, Guha A, Rak JW. Tissue factor regulation by epidermal growth factor receptor and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transitions: effect on tumor initiation and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:10068–10076. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao J, Aguilar G, Palencia S, Newton E, Abo A. rNAPc2 inhibits colorectal cancer in mice through tissue factor. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:208–216. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ngo CV, Picha K, McCabe F, Millar H, Tawadros R, Tam SH, Nakada MT, Anderson GM. CNTO 859, a humanized anti-tissue factor monoclonal antibody, is a potent inhibitor of breast cancer metastasis and tumor growth in xenograft models. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1261–1267. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu J, May L, Milsom C, Anderson GM, Weitz JI, Luyendyk JP, Broze G, Mackman N, Rak J. Contribution of host-derived tissue factor to tumor neovascularization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1975–1981. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.175083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Versteeg HH, Schaffner F, Kerver M, Petersen HH, Ahamed J, Felding-Habermann B, Takada Y, Mueller BM, Ruf W. Inhibition of tissue factor signaling suppresses tumor growth. Blood. 2008;111:190–199. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hua Y, Tang L, Keep RF, Schallert T, Fewel ME, Muraszko KM, Hoff JT, Xi G. The role of thrombin in gliomas. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1917–1923. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Altschuler E, Moosa H, Selker RG, Vertosick FT., Jr The risk and efficacy of anticoagulant therapy in the treatment of thromboembolic complications in patients with primary malignant brain tumors. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:74–77. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199007000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marras LC, Geerts WH, Perry JR. The risk of venous thromboembolism is increased throughout the course of malignant glioma: an evidence-based review. Cancer. 2000;89:640–646. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<640::aid-cncr20>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tehrani M, Friedman TM, Olson JJ, Brat DJ. Intravascular thrombosis in central nervous system malignancies: a potential role in astrocytoma progression to glioblastoma. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:164–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barker FG, 2nd, Davis RL, Chang SM, Prados MD. Necrosis as a prognostic factor in glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer. 1996;77:1161–1166. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960315)77:6<1161::aid-cncr24>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential tumour angiogenesis factor in human gliomas in vivo. Nature. 1992;359:845–848. doi: 10.1038/359845a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hembrough TA, Swartz GM, Papathanassiu A, Vlasuk GP, Rote WE, Green SJ, Pribluda VS. Tissue factor/factor VIIa inhibitors block angiogenesis and tumor growth through a nonhemostatic mechanism. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2997–3000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu Y, Mueller BM. Protease-activated receptor-2 regulates vascular endothelial growth factor expression in MDA-MB-231 cells via MAPK pathways. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;344:1263–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Versteeg HH, Schaffner F, Kerver M, Ellies LG, Andrade-Gordon P, Mueller BM, Ruf W. Protease-activated receptor (PAR) 2, but not PAR1, signaling promotes the development of mammary adenocarcinoma in polyoma middle T mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7219–7227. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yin YJ, Salah Z, Maoz M, Ram SC, Ochayon S, Neufeld G, Katzav S, Bar-Shavit R. Oncogenic transformation induces tumor angiogenesis: a role for PAR1 activation. FASEB J. 2003;17:163–174. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0316com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamahata H, Takeshima H, Kuratsu J, Sarker KP, Tanioka K, Wakimaru N, Nakata M, Kitajima I, Maruyama I. The role of thrombin in the neo-vascularization of malignant gliomas: an intrinsic modulator for the up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:921–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Waddington SN, McVey JH, Bhella D, Parker AL, Barker K, Atoda H, Pink R, Buckley SM, Greig JA, Denby L, Custers J, Morita T, Francischetti IM, Monteiro RQ, Barouch DH, van Rooijen N, Napoli C, Havenga MJ, Nicklin SA, Baker AH. Adenovirus serotype 5 hexon mediates liver gene transfer. Cell. 2008;132:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]