Abstract

Base J is a hypermodified DNA base localized primarily to telomeric regions of the genome of Trypanosoma brucei. We have previously characterized two thymidine-hydroxylases (TH), JBP1 and JBP2, which regulate J-biosynthesis. JBP2 is a chromatin re-modeling protein that induces de novo J-synthesis, allowing JBP1, a J-DNA binding protein, to stimulate additional J-synthesis. Here, we show that both JBP2 and JBP1 are capable of stimulating de novo J-synthesis. We localized the JBP1- and JBP2-stimulated J by anti-J immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing. This genome-wide analysis revealed an enrichment of base J at regions flanking polymerase II polycistronic transcription units (Pol II PTUs) throughout the T. brucei genome. Chromosome-internal J deposition is primarily mediated by JBP1, whereas JBP2-stimulated J deposition at the telomeric regions. However, the maintenance of J at JBP1-specific regions is dependent on JBP2 SWI/SNF and TH activity. That similar regions of Leishmania major also contain base J highlights the functional importance of the modified base at Pol II PTUs within members of the kinetoplastid family. The regulation of J synthesis/localization by two THs and potential biological function of J in regulating kinetoplastid gene expression is discussed.

INTRODUCTION

Base J (β-d-glucopyranosyloxymethyluracil) is the only hyper-modified DNA base identified in eukaryotes. The modification is synthesized in two-steps. Step one involves the hydroxylation of thymidine by a thymidine hydroxylase (TH) enzyme, forming the intermediate HOMedU in DNA. This intermediate is then glucosylated by a glucosyl transferase (GT) (1). This DNA modification has been evolutionarily conserved within members of the kinetoplastid family, the most well studied of which are Trypanosoma brucei, Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania major, where J replaces about 1% of the total T in DNA.

In T. brucei, 50% of J is found within the telomeric repeats. J is also associated with sub-telomeric repetitive DNAs including the 177-bp, 70-bp and 50-bp repeats, as well as being scattered throughout the silent telomeric Pol I VSG expression sites (ES) (2–4). The regulation of the ∼15 telomeric ESs allows the parasite to evade the host immune system in a process called antigenic variation (5,6). The genome of T. brucei has over 1000 VSG genes, yet expression is monoallelic. This is achieved through regulated transcription of the telomeric ESs, only one of which is productively transcribed at any time. The association of the modified base with silent ESs in the bloodstream life-cycle stage of the parasite, and its absence during the Tsetse life-cycle stages that do not transcribe the telomeric VSGs, has led to the hypothesis that J plays a role in the regulation of antigenic variation. J has also been found at a few genome-internal sites, including the 5S ribosomal RNA and spliced leader RNA genes (3). However, no other regions of the genome have been shown to contain J, and the primary function of J in African trypansomes is thought to be restricted to some as-yet undefined aspect of telomere biology, such as the regulation of monoallelic VSG gene expression from the ∼15 telomeric ESs. However, so far no direct evidence for J regulating antigenic variation has been provided.

J is found in other kinetoplastids, the most widely studied of which are T. cruzi and L. major (2,7). In T. cruzi, J levels are developmentally regulated and are 2-fold higher in the promastigote stage than in epimastigotes. 75% of J is associated with the telomeric repeats (7). A significant level of J is also localized within the sub-telomeric region of the genome rich in large multi-gene families of surface glycoproteins that are essential for parasite pathogenesis. Whether J plays a role in regulating the expression of these surface proteins remains unknown. In L. major, 98% of J associates with telomeric DNA (8). The function of J in L. major remains unknown, but it appears to be essential for parasite survival (9,10).

We have characterized two distinct TH enzymes, JBP1 and JBP2, which regulate J synthesis (11,12). Both proteins contain a putative TH domain at the N-terminus, characterizing them as members of the recently identified TET/JBP superfamily of Fe2+/αKG enzymes (13). The mutation of key conserved residues within the TH domain, known to be critical for co-ordination of Fe2+ and binding of αKG, ablates JBP function in vivo (14,15). Deletion of either JBP1 or JBP2 from bloodstream-form (BF) T. brucei resulted in a 20- and 8-fold reduction in J levels, respectively (16,17). The generation of a J-null cell line upon deletion of both JBP1 and JBP2 confirmed that both TH enzymes are involved in the regulation of J synthesis (14).

The C-terminal domain of JBP2 contains a SWI2/SNF2 domain, thought to be involved in chromatin remodeling, whereas JBP1 contains a proposed J-DNA binding domain. JBP1 has been show to bind base J in the context of dsDNA with high affinity (18). The expression of JBP2 in procyclic (PC) cells, a life-stage that down-regulates JBP expression and thus normally lacks J, demonstrated that the protein induces de novo J synthesis. Similar experiments with JBP1 failed to demonstrate such activity (12). Based on these data, the model of J biosynthesis is that JBP2 binds chromatin via the SWI/SNF domain and modifies chromatin structure, thereby allowing the TH domain to hydroxylate specific T residues within the chromosome. This basal level of J provides substrate to which JBP1 can bind and propagate J. This separation of function is proposed to explain why two TH are required to regulate J biosynthesis (14).

Here, we show that the expression of JBP1 in the BF T. brucei J-null background induces de novo synthesis of J, but it is lost during subsequent cell proliferation. The expression of JBP2 rescues synthesis, whereas expression of an inactive mutant JBP2 does not. Solexa DNA sequencing analysis of anti-J immunoprecipitated genomic DNA revealed that base J is found throughout the genome of T. brucei, enriched at regions flanking Pol II polycistronic transcription units (PTUs). JBP1 and JBP2 stimulated J synthesis at different chromosomal sites, JBP1 being the primary inducer of genome-internal J and JBP2 functioning optimally within the telomeric environment. While JBP1 is able to stimulate high levels of de novo J at regions flanking Pol II PTUs, functional JBP2 is required for stabilized and optimal JBP1 function. We conclude that J synthesis leads to an epigenetic modification of chromatin that precludes optimal maintenance of J by JBP1. Therefore, J is lost unless JBP2 is co-expressed. These data provide an explanation for why two TH enzymes are required for J synthesis. The localization of base J at regions flanking Pol II PTU appears to be conserved among the kinetoplastida, suggesting a role in global Pol II transcription as well as at telomeric ESs involved in antigenic variation in T. brucei.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Enzymes and chemicals

Neomycin (neo) and phleomycin (phleo) were purchased from Research Diagnostic International. All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Anti-GFP antibody, anti-Ha antibody and Alexa labeled goat anti-rabbit and Benchmark Pre-stained protein standard were purchased from Invitrogen. Prime-It II random primer labeling kit was purchased from Stratagene, α-32P-dATP and γ-32P-ATP was purchased from Perkin Elmer. ECL and Hybond-N+ were from Amersham. Goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was purchased from Southern Biotec Inc. All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich.

Trypanosome cell culture

BF T. brucei cell line 221a of strain 427 was cultured in HMI-9 medium as described previously (12).

Generation and analysis of T. brucei transfectants

The generation of J-null cells expressing JBP2 was performed by transfection with either GFP-JBP2-Tub-phleo (Tub, tubulin) (or mutant versions of GFP-JBP2-Tub-Phleo) (12), or JBP2-Tub-phleo. Transfections were performed using a Nucleofector (Amaxa) as previously described (19). The construct was digested by NotI and XhoI prior to transfection. Transfectants were selected with 2.5 µg/ml phleomycin. Cell lines expressing JBP1-GFP were generated following transfection with GFP-JBP1-Tub-phleo. The construct was digested by NotI and XhoI prior to transfection. Transfectants were selected with 2.5 µg/ml phleomycin. Cell lines expressing an untagged JBP1 were generated by transfection with JBP1-neo (17). This construct allows the expression of JBP1 from the ribosomal locus. Five micrograms of the construct were linearized by AvaI digestion prior to transfection. Transfectants were selected at 2 µg/ml neomycin. H3V–/– cell lines were generated as previously described (20). The generation of cells expressing both JBP1 and a tagged JBP2 were generated to test for JBP1–JBP2 interaction. Cell lines expression untagged JBP1 were subject to an additional round of transfection using GFP-JBP2-Tub-phleo.

Mutagenesis

The mutations in JBP2 were made by site-directed mutagenesis using the Quik-Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) following the instruction of the manufacturer. The wild-type T. brucei GFP-JBP2-Tub-Phleo construct was used as a template. The different oligonucleotides used for the mutagenesis reaction as well as detailed maps of the expression vectors can be given upon request. Mutations were verified by sequencing using an ABI Prism 3700 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Determination of the genomic level of J

To quantify the genomic J levels, we used the anti-J DNA immunoblot assay as described (4) on total genomic DNA, which was isolated as described (21). Briefly, serially diluted genomic DNA was blotted to nitrocellulose followed by incubation with anti-J antisera. Bound antibodies were detected by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to HRP and visualized by ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence). The membrane was stripped and hybridized with a probe for the β-tubulin gene to correct for DNA loading.

Western blotting

Proteins from 107 cell equivalents were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS page 8% gel), transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with either anti-JBP2 (1:2000 dilution), anti-JBP1 (1:2000 dilution) or anti-GFP (1:3000 dilution) antisera as previously described (16). Bound antibodies were detected by a secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to HRP and visualized by ECL.

The localization of base J

J was localized in the telomeric repeat regions by anti-J immunoprecipitation of sonicated genomic DNA which was then cross-linked to nitrocellulose and subject to hybridization with radioactive probes as described previously (3,4,22). For the genome wide localization of base J, genomic DNA was sonicated and anti J immunoprecipitation was performed as described (3,4,22). DNA was then subject to further sonication to give fragments with an average size of 200 bp. Immunoprecipitated DNA was sequenced using a Solexa sequencer (Illumina) as previously described (23). Briefly, the sequenced DNA tags (32 bp or 36 bp) were annotated based on the T. brucei genome (version 4) using the Bowtie algorithm (24) using default parameters and allowing two mismatches. The number of hits per nucleotide position was determined using custom PERL scripts and displayed using MATLAB (The Math Works).

Confirmation of genome internal J by polymerase chain reaction

Genomic DNA was sonicated and J containing DNA was immunoprecipitated as above. Immunoprecipitated J containing DNA was then used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Input DNA was used as a positive control for PCR (10% of the IP). Each PCR cycle was 1 min 94°C, 1 min 56°C, 1 min 72°C (25 cycles) followed by 5 min at 94°C and 10 min at 72°C. Primers used were as follows (5′–3′):

1.1 SP ′GTC GCG AGC AAG GGT TGG G′

1.1 ASP ′CTC CCG TGC CGT CGG TAT G′

1.2 SP ′GCA AGG GTT GGG TTC GTT G′

1.2 ASP ′GTA CAA GGT CTG CGT GCT C′

1.3 SP ′GAG GCA GCC CTC AAT GCA TAG GAT G′

1.3 ASP ′CT TTT CG CCT GTA AGT GGG GAT CGG′

1.4 SP ′CGT CTG CGT CTA TTC GTG G′

1.4 ASP ′GTA CTC TGT CGC GCT CCG′

1.5 SP ′GTT CAC CTC CAT GTT ACA AGC′

1.5 ASP ′G GGT TGA AGG CAT ATA CAT TCC′

1.6 SP ′GGA ATG CCG AAT TTG GAA ACC′

1.6 ASP ′CG ACA TGC TTT GTA CGG ATG′

–10 kb SP ′GGC GTG ACA GCA CTT TTG G′

–10 kb ASP ′C TGG CGC TCT TCC AAC AAC′

–20 kb SP ′GAA GAC GGT GAG CGA GTA G′

–20 kb ASP ′CA CAA CTG TCG TCT TCA CCC′

+10 kb SP ′CTG GTT GGT TTG GAG AGA GAG′

+10 kb ASP ′CAA CTT TAC AAG CAA GGG AGG′

+20 kb SP ′CAA CCT TAC GGG ATG TCA AC′

+20 kb ASP ′G CCA AAC GAA TCG CAT ACC′

A SP ′GAT ATG TGA GGG GTG TTG AGG′

A ASP ′CTC TCT CAC ACA CAC ACA AGC′

B SP ′GAA CTG ATC AAC GTC TCG G′

B ASP ′GT AAT GAA GCG CTG CAC TAG′

C SP ′CTT ATC GGT TTC CGT CCT G′

C ASP ′GGG AAA AGG AGA GAC CAG′

D SP ′GTT CTT GTT TCG TCT ACC CTC G′

D ASP ′CT CAG CAC ATC CCC TCT GAT′

E SP ′GGA AGC TCT GAT GAC CAG AAA C′

E ASP ′C GCT AAC CGT CTC CAA ATC ATC′

F SP ′GGA AGC TCT GAT GAC CAG AAA C′

F ASP ′C GCT AAC CGT CTC CAA ATC ATC′.

Culture of L. major

Parasites were grown at 26°C in M199 media supplemented with 10% FBS as described (25).

Assessment of L. major SSR for presence of J

Leishmania major genomic DNA was isolated as described for T. brucei (21). Genomic DNA was sonicated and immunoprecipitated J containing DNA was used for PCR analysis as described above. Input DNA was used as a positive control for PCR. Primers used were as follows (5′–3′):

A SP ′CGC ATC AGT AGA TCT GCG TC′

A ASP ′ CG TCA CAT CGA AAG AAG GTT AAG′

B SP ′CAG CTC GAG AGA TCA CTC AC′

B ASP ′CGT TGC AGG CAT CGG AC′

C SP ′CGT GGC CGA AGA CAG AC′

C ASP ′C CAA AAA CCA AGC GCG CAT′

D SP ′CAC GAT GAC GCT CTA CCC′

D ASP ′CTC GGT TAG TAC TGA GGT CAG′

–VE SP ′ATG GAC CAA GTG GCC GTC′

–VE ASP ′CAG CTG GGA CGT CAA GTC′.

RESULTS

JBP1 stimulates de novo J synthesis but requires JBP2 function for optimal maintenance

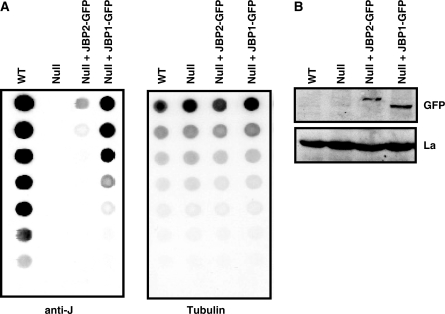

To help understand why two TH are required for J biosynthesis, we re-expressed JBP1 and JBP2 in the BF J-null cell line (JBP1–/–, JBP2–/–). Previous analysis in procyclic trypanosomes revealed that JBP1 was unable to stimulate de novo J synthesis but caused an increase in J once a basal level was provided by JBP2 (12). It was unexpected, therefore, that the expression of JBP1 in the BF J-null cell line induced high levels of de novo J synthesis, up to 5-fold more than due to JBP2 (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

JBP1 induces de novo J synthesis when expressed in the BF J-null. (A) Dot-blot analysis of J-null cells expressing either JBP1 or JBP2. DNA was isolated from bloodstream-form cell lines and analyzed for J content by spotting DNA in a 2-fold dilution series onto a membrane and incubation with anti-J antiserum. WT, wild-type bloodstream-form cells; Null, cells in which both JBP1 and JBP2 are deleted; Null + JBP2, J-null cells expressing JBP2-GFP for 45 generations; Null+ JBP1, J-null cells expressing JBP1-GFP for 45 generation. Blots were stripped and probed for tubulin using P32 labeled probe as a loading control. (B) Expression of either JBP1/2-GFP in the J-null cell line was confirmed by western blot using anti-GFP antiserum. Anti-La antiserum was used as a loading control.

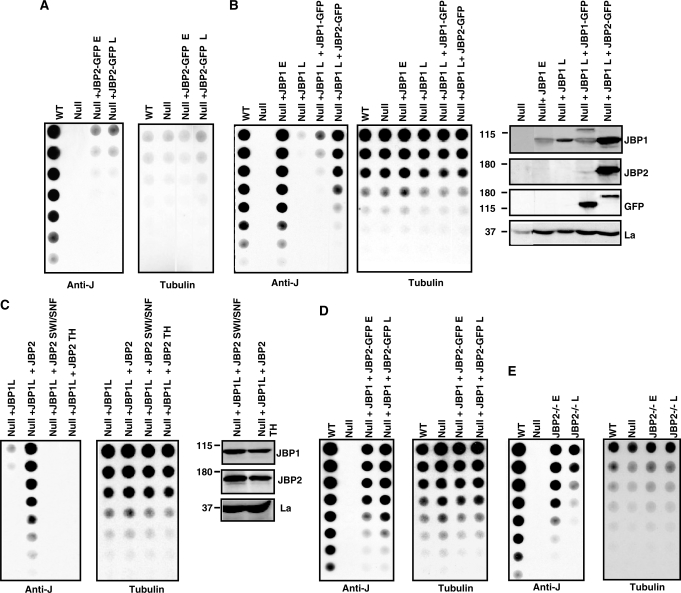

If the levels of J are followed in these cell lines over several generations, JBP2-induced J was stable (Figure 2A), whereas the JBP1-induced J was lost from the genome after propagation for 300 generations (Figure 2B). The activities of JBP1 and JBP2 are affected by the presence of the N-terminal GFP tag (Figure S1). This explains the different levels of de novo J stimulated by JBP1 in Figures 1A and 2B. The inability of JBP1 to function over time was not a consequence of a reduction in protein or RNA levels (Figure 2B, data not shown). In fact, an additional ∼1.5-fold increase in JBP1 expression failed to rescue this effect (Figure 2B). However, J synthesis was restored following JBP2 expression in the null+JBP1 cells cultured for 300 generations (null+ JBP1L) (Figure 2B). The increase in J upon re-expression of JBP2 was greater than that attributable to JBP2-stimulated de novo synthesis alone (compare Figure 2A and B), indicating that JBP2 alleviated the repression of JBP1 function. In support of this idea, the ability of JBP2 to rescue J synthesis was dependent upon functional TH and SWI2/SNF2 domains (Figure 2C). Furthermore, expression of JBP2 in the null+JBP1 cell line (null cells expressing JBP1 cultured for only 45 generations) stabilized and prevented the loss of J synthesis (Figure 2D). Therefore, JBP1 can stimulate de novo J synthesis (via de novo thymidine hydroxylation) but is unable to fully stimulate ongoing de novo or maintenance hydroxylation once the DNA has been modified. Consistent with this idea, the JBP2–/– cell line (which still contains JBP1) was unable to stably maintain J synthesis (Figure 2E). By contrast, the levels of J in the JBP1–/– were stable over 600 generations (data not shown).

Figure 2.

JBP1-induced de novo J is unstable but is rescued by the expression of JBP2. (A) Dot-blot analysis of J-null cells expressing JBP2-GFP over time. DNA was isolated from bloodstream-form cells indicated and analyzed for J content as described in Figure 1 Null + JBP2-GFP E, J-null cells expressing JBP2 grown for 45 generations; Null + JBP2-GFP L, J-null cells expressing JBP2 grown for 300 generations. (B) Dot-blot analysis of J-null cells expressing JBP1 over time. DNA was isolated from bloodstream-form cells indicated and analyzed for J content as described in Figure 1. Null + JBP1 E, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 45 generations; Null + JBP1 L, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 300 generations; Null + JBP1L + JBP1-GFP, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 300 generations and then transfected with JBP1-GFP; Null + JBP1L + JBP2-GFP, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 300 generations and then transfected with JBP2-GFP. On the right is a western blot confirming the expression of JBP1 and JBP2 in the indicated cell lines. The untagged JBP1 runs at 90 kDa and the GFP-tagged version at 120 kDa. JBP2-GFP runs at 150 kDa. (C) Dot-blot analysis of J-null cells expressing JBP1 complimented with WT and mutant JBP2. DNA was isolated from the BF cell lines cells indicated and analyzed for J content as described in Figure 1. Null + JBP1L + JBP2-GFP, null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 300 generations and then transfected with JBP2-GFP; Null + JBP1L + JBP2SWI/SNF null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 300 generations and then transfected with JBP2 with a mutation in the SWI/SNF domain (K550A) (12); Null + JBP1L + JBP2TH, null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 300 generations and then transfected with JBP2 with a mutation in the TH domain (H441A) (14). The expression of JBP1 and JBP2 in the J-null cell line was confirmed by western blot analysis (on the right) as described above. (D) Dot-blot analysis of J-null cells expressing JBP1 complimented with JBP2. DNA was isolated from cell lines cells indicated and analyzed for J as in Figure 1. Null + JBP1, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 90 generations; Null + JBP1 + JBP2E, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 90 generations and then transfected with JBP2-GFP; Null + JBP1 + JBP2L, J-null cells expressing JBP1 grown for 90 generations and then transfected with JBP2-GFP and grown for an additional 300 generations. (E) Dot-blot analysis of the BF JBP2–/– cell line. DNA was isolated from the indicated cells and analyzed for J content as described in Figure 1. JBP2–/–E, BF cells in which JBP2 has been deleted and then the cells grown for 45 generations; JBP2–/–L, JBP2 KO cells grown for 400 generations.

These data suggest that JBP1 and JBP2 work together to maintain hydroxylated thymidines in the genome for stable J biosynthesis. One possibility is that JBP1 requires physical interactions with JBP2 for full activity. To address this, JBP1 and JBP2-GFP were expressed in the J-null cell line and anti-GFP pull downs performed in the absence and presence of protein cross-linking agent. However, while the GFP pull down was successful, no JBP1 was detected in any condition examined (data not shown), suggesting that the two proteins do not form stable interactions in vivo. It is also possible that interactions between JBP1 and JBP2 are reduced in our analysis due to the presence of the GFP tag.

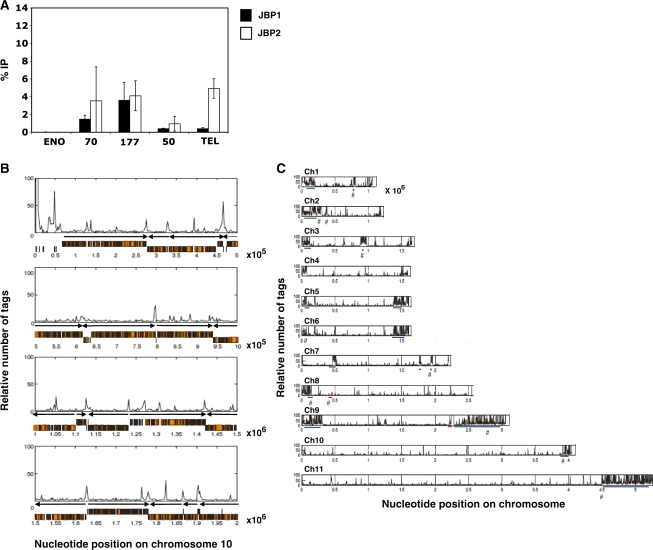

JBP1 regulates J synthesis at regions flanking Pol II PTU

The previous model for JBP1 function, as a maintenance hydroxylase for J biosynthesis, was based on its specific and high affinity for J-modified DNA. According to this model, JBP1 is able to bind and function anywhere thymidines are hydroxylated by JBP2 and converted to J in the genome. The finding that JBP1 can stimulate de novo J synthesis when expressed in the J-null cell line raised the question where the resulting J was located, given the absence of J as an initial binding platform. Initial analysis of the null + JBP1 cell line by anti-J IP and dot-blot hybridization indicates that J does not localize to the telomeric repeats to the same extent as that found in the JBP2 expressing cell (Figure 3A). While there are no significant differences in J levels in the sub-telomeric regions due to JBP1 and JBP2, JBP2 expression resulted in higher J levels in the telomeric repeats than JBP1. Taking into account the 10-fold higher global levels of de novo J by JBP1 (Figure 1), a significant fraction of the modified base must therefore be localized outside these telomeric regions in the null + JBP1 cell line.

Figure 3.

JBP1 and JBP2 stimulate J with different specificities for regions of the genome. (A) In order to localize J within the genome, DNA was isolated from J-null cells expressing either JBP1 or JBP2. DNA was sonicated and J-containing DNA fragments immunoprecipitated using J antiserum. Ten percent of the input DNA (IN) and 100% of the immunoprecipitated DNA (IP) were blotted onto nitrocellulose. Blots were then hybridized with radiolabeled DNA probes corresponding to indicated regions of the trypanosome genome. The percent IP was calculated for each region of the genome analyzed for the indicated cell line and values were normalized to background hybridization. ENO, enolase; 70, 177 and 50 refer to the corresponding repeat regions; Tel, telomere. Each value represents a mean of between three and five hybridizations ± SD. (B) J is found internally in the genome. DNA was isolated from WT BF cells, sonicated and J-containing DNA fragments immunoprecipitated and sequenced to analyze the genome-wide distribution of J. A representative region of chromosome10 is shown; the relative number of tags was calculated over a window of 2 kb and normalized to input DNA, eliminating artifacts attributable to repetitive DNA. Orange boxes represent ORFs, and black arrows indicate the direction of transcription from previously implicated transcription start sites. As indicated in the text, the peaks of J include the Pol II PTU flanking regions as well as other sequences within a PTU. The peaks of J within a PTU correlate with spacer regions between individual ORFs and corresponding to, in many cases, AT-rich sequences. The peaks of J within the sub-telomeric region (left end of the chromosome shown here) include silent VSG and ESAG genes. (C) Genome-wide distribution of base J on chromosomes 1-11 of WT T. brucei. Majority of the chromosome internal peaks represent J at the Pol II PTU flanking regions. The large concentration of J at the sub-telomeric regions includes arrays of silent VSG genes and, in some cases, telomeric repeat sequences (30). Silent VSG loci are indicated by blue underlines. The location of the SL array (at 2.23–2.27 × 106) chromosome 9, and 5S (4.5–4.6 × 105) on chromosome 8 is indicated by a red underline. A large SSR running from 8.7–9.7 × 105 on chromosome 3, and three large J peaks resulting from the close proximity of multiple SSRs on chromosomes 1 and 7, are indicated by an asterisk. Large RHS arrays are identified by a green underline. rDNA transcription units are indicated by #. All examined arrays localize to regions that contain base J, except one array on chromosome 8 at position 4.5–4.6 × 105. (D) Genome-internal J was confirmed by IP-PCR analysis in WT cells. The peak represents J at position 2.5 × 105 bp of chromosome 10. Primers were designed to span the peak and are indicated on the schematic as numbers 1–5. J-negative regions representing 10 and 20 kb upstream (–) and downstream (+) of the SSR were also examined. Dashed lines represent ORFs and arrows represent the direction and limit of PTU. (E) Internal J is stimulated preferentially by JBP1 versus JBP2. Anti-J IP/DNA sequencing was performed on WT, and null cells expressing either JBP1 or JBP2 as described above. The localization of J in the two JBP expressing cell lines was performed utilizing trypanosomes at similar number of generations (∼45) post transfection. A representative region of chromosome 10 is shown. Black represents WT; green, Null +JBP1; blue, Null+JBP2. (F) Anti-J IP/PCR analysis was performed on the indicated cell lines. Regions A–D represent 4 region of chromosome 10 shown to contain J in WT cells (positions along chromosome are 1.23 × 106, 1.63 × 106, 2.3 × 106, 2.86 × 106 nt respectively). Two regions negative for J by sequencing are also shown as controls (E and F), representing regions 1.35 × 106 and 1.68 × 106, respectively.

To determine the genome-wide distribution of base J in the null + JBP1 cell line, anti-J IP coupled with DNA sequencing was performed using Solexa (Illumina) high-throughput sequencing. This ChIP-seq approach was chosen as it is quantitative, non-biased and allows genome-wide analysis. This analysis was also performed on WT cells and null + JBP2 cells. The anti-J IP-seq analysis of WT T. brucei indicates J is highly enriched at telomeric and sub-telomeric regions of the genome (Figure 3B and C). The 927 trypanosome genome database does not include sequences from the telomeric VSG expression sites. However, the assembly of the IP-seq data utilizing the VSG expression site data from 427 trypanosome cell line confirmed the presence of J within the telomeric VSG expression sites (data not shown). Interestingly, we also found significant levels of the modified base distributed throughout the T. brucei genome (Figure 3B and C). Recent ChIP-seq analysis of genome-wide distribution of chromatin modifications (i.e. H4K10ac, H2AZ, H2BV, H3V and H4V) has mapped the Pol II polycistronic transcription units (PTU) along the genome of T. brucei (23). Comparing these data with the ChIP-seq analysis here, we found that the distribution of the genome-internal J was not random, but localized within regions flanking the Pol II PTU throughout the genome of WT T. brucei. These include convergent and divergent strand-switch regions (SSRs). Additional PCR analysis across one specific J-containing Pol II PTU flanking region of chromosome 10 (position 2.5 × 105 bp) tightly correlated with quantification of the ChIP-seq reactions (Figure 3D).

In addition to the peaks of J within the PTU flanks, the genome-wide analysis has confirmed the presence of J at previously identified internal regions of the genome, including SL RNA and 5S loci (data not shown and Figure 3C). We also find the modified base localized to silent sub-telomeric VSG gene arrays (Figure 3C). Moreover, as indicated in Figure 3B, J is localized at various sites within a PTU. The peaks of J within a PTU typically correlate with spacer regions between individual ORFs and in some cases correspond to AT-rich DNA sequences.

In the J-null cells expressing JBP1, J was stimulated at genome-internal sites, as seen in WT cells (Figure 3E and Table 1), demonstrating that JBP1 can stimulate specific localized de novo J synthesis. By contrast, while JBP2 stimulated J synthesis within regions we have previously identified (i.e. telomeric and sub-telomeric repeats), it failed to stimulate significant levels of the modified base at internal regions of the genome that flank Pol II PTU (i.e. JBP1 specific regions) (Figure 3E and Table 1). PCR analysis of anti-J IP DNA from WT, J-null + JBP1 and J-null + JBP2 cell confirmed the sequencing data (Figure 3F). The analysis of J localization shown in Figure 3F not only confirmed the specificity of the JBP1 versus JBP2-stimulated J synthesis within the Pol II PTU flanking regions, but also the inability of JBP1 to optimally function without JBP2. Therefore, the loss of J that occurs over several generations following JBP1 function was global, occurring in the PTU flanking regions within the genome as well as within telomeric repeat regions (Figure 3F and data not shown). Therefore, there appears to be a distinct chromatin substrate requirement for JBP1 and JBP2 function in vivo. JBP2 preferentially stimulates J synthesis in the telomeric and sub-telomeric regions of the genome, whereas JBP1 is responsible for the induction of J synthesis within internal regions of the genome. However, JBP2 function is required for optimal maintenance of J by JBP1 at these JBP1 specific internal regions of the genome.

Table 1.

Analysis of J containing PTU flanking regions on chromosome 10

| Cell type | Divergenta | Convergenta | Head to taila | Total %b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 5/10 | 7/10 | 10/10 | 73% |

| Null + JBP1 | 10/10 | 6/10 | 10/10 | 87% |

| Null + JBP2 | 0/10 | 3/10 | 1/10 | 13% |

aThe number of J containing divergent and convergent SSR and head-to-tail regions was determined, and expressed over the total number present on chromosome 10; only values >2500 sequence tags were deemed as significant.

bTotal % reflects the total number of J containing regions flanking PTU in each cell line.

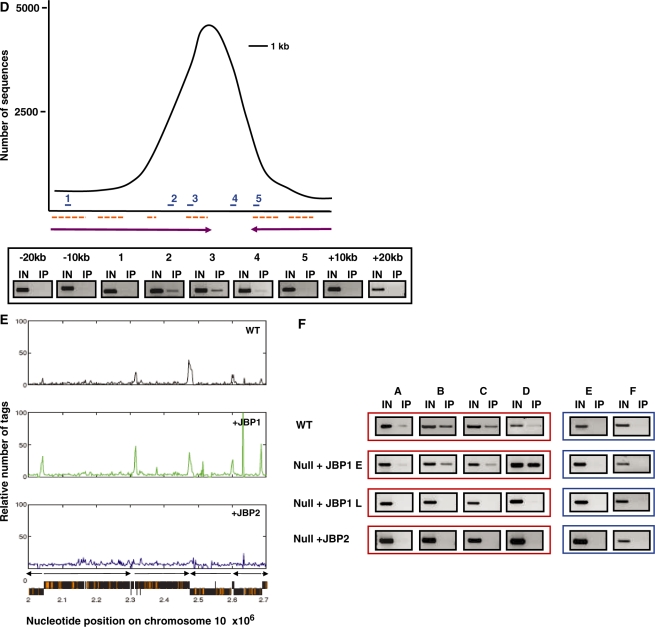

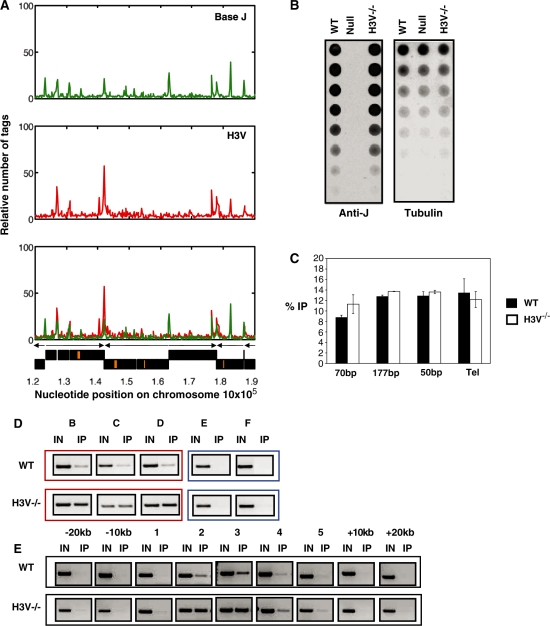

Histone variant 3 (H3V) co-localizes with base J

H3V is enriched at telomeric and sub-telomeric sites and at presumed transcription termination sites (TTSs) of Pol II PTU (20,23). A comparison of the genome-wide distribution of base J with ChIP-seq analysis of H3V showed a striking correlation between their localization (Figure 4A and Figure S2). As we show here, base J is localized to PTU flanks, including TTS, as well as previously characterized telomeric repeats. Thus, apparently all regions enriched with H3V also contain J. Interestingly, H4V was also found at TTS (23), but H4V is found at much lower levels in the telomeric and sub-telomeric regions than H3V and J. To address whether H3V is important in J synthesis and localization (and ultimately JBP1/JBP2 function), we utilized a cell line in which H3V had been deleted (20,23). Anti-J dot-blot analysis indicated that H3V is not essential for J synthesis (Figure 4B). Furthermore, H3V does not play a role in the localization of base J both at genome internal and telomeric sites (Figure 4C–E). Moreover, the deletion of H4V had no effect on J synthesis (Figure S3).

Figure 4.

Base J co-localizes with H3V at convergent SSRs. (A) Representative region of chromosome 10 is shown, indicating the localization of J in WT (green) and the relative number of sequence tags for immunoprecipitated H3V, as previously published, normalized to input DNA (red). The bottom panel shows an overlay of H3V and J. (B) The levels of base J in the H3V–/– cells were analyzed by dot blot as described in Figure 1. H3V–/–, histone variant 3 null cells. (C) Anti-J IP was performed and on WT and H3V–/– cells and subject to hybridization and phosophorimager analysis as described previously (18). 70, 177 and 50 refer to the corresponding repeat regions; Tel, telomere. Each value represents a mean of between three and five hybridizations ± SEM. (D) J localization in WT and H3V–/– cells. Anti J IP/PCR analysis was performed for regions B-D (as in Figure 4F) that represent three regions of chromosome 10 shown to contain J in WT cells. Two regions negative for J by sequencing are also shown as controls (E and F). (E) J localization across a SSR in the WT and H3V–/– genome. IP-PCR analysis was performed as described in Figure 4D.

Pol II PTU flanks in L. major also contain base J

Previous analysis indicated that 98% of J in Leishmania is present in telomeric repeats (8). However, our analysis of L. major DNA by anti-J IP and PCR identified J within regions flanking PTU, as in T. brucei (Figure S4). In this analysis, we examined six SSRs (three convergent and three divergent) located on different chromosomes of L. major. All sequences analyzed within the SSR tested positive for base J. PCR analysis of a gene within a PTU acted as a negative control. These data suggest that the presence of the modified base at sequences flanking Pol II PTU is a conserved feature of kinetoplastids.

DISCUSSION

The glucosylated thymidine DNA base J was initially described based on its presence in the silent telomeric VSG expression sites in T. brucei. Further studies identified 50% of the total J in telomeric repeats and the majority of the remaining J in subtelomeric repeats [50, 70 and 177 bp (2,3)]. A small number of internal repeat regions of the genome also contain low levels of J [such as the 5S, SLRNA (2,3)]. However, J was never detected elsewhere in the genome.

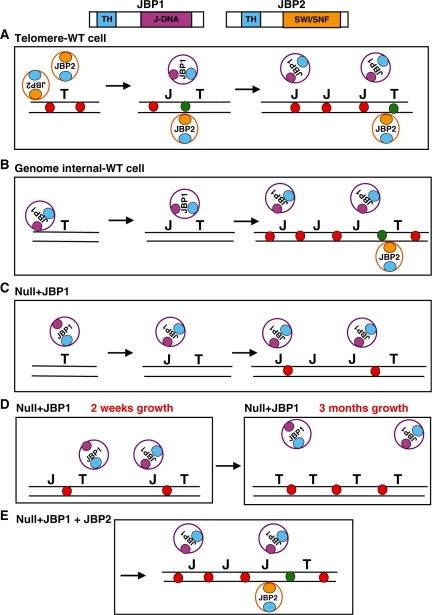

In this study, whole-genome analysis allowed the identification of significant levels of the novel modified DNA base J throughout the genome of T. brucei. Interestingly, the base shows a specific distribution pattern, with enrichment at regions flanking Pol II PTUs. The presence of base J at these regions is dependent upon the activity of two thymidine hydroxylases, JBP1 and JBP2, which have initial chromatin substrate preferences. JBP2 functions preferentially in telomeric regions, whereas JBP1 stimulates de novo J at regions flanking Pol II transcription units. However, JBP1 is unable to optimally maintain J synthesis without JBP2 function. These studies help explain why two thymidine hydroxylases are required for J synthesis and implicate base J in the regulation of Pol II PTU within members of Kinetoplastidea as well as the telomeric Pol I PTU involved in the regulation of antigenic variation of African trypanosomes.

The regulation of J biosynthesis by two thymidine hydroxylases

JBP1 and JBP2 have been identified as two distinct TH enzymes involved in step one of J-biosynthesis. In order to explain why two TH are needed to regulate J synthesis in T. brucei, the previous model of J biosynthesis proposed a separation of function for JBP1 and JBP2. This model was primarily based on the finding that JBP2 stimulated de novo J synthesis when expressed in the PC trypanosome (which normally lacks J), whereas JBP1 failed to demonstrate this activity (12). The levels of J stimulated by JBP2 were low, and mirrored the known localization of J in WT BF cells (telomeric and sub-telomeric repeats). JBP1 was identified based on its ability to bind J-DNA with high affinity (11,18) and, thus, represented the propagation/maintenance factor which could amplify the specific basal level of J seeded by JBP2 (12).

We now demonstrate that JBP1 is capable of de novo synthesis activity, raising the question why this activity was not detected previously using PC trypanosomes. The primary explanation appears to be the inability of JBP1 to optimally function without JBP2. We have also shown that the function of both JBP1 and JBP2 is affected by the presence of an N-terminal GFP tag, which reduces the J stimulation activity of both enzymes. We believe that the use of GFP-tagged version of JBP1, the analysis of J levels several generations post-transfection and the overall reduced activity of JBP1 in PC versus BS cells (data not shown) explains our previous failure to detect de novo J synthesis activity of JBP1. We, and others (Borst,P., personal communication), have since confirmed that the expression of an untagged JBP1 in PC cells induces J synthesis, although levels are significantly lower (8-fold) that in BF cells (data not shown).

The identification of de novo J synthesis activity of JBP1 has rendered our old model for the regulation of J synthesis obsolete (see Figure 5 for a revised model). Rather than a distinct separation of function between the JBPs, this work reveals a differential substrate preference for each. Analysis of the genome-wide distribution of the modified base due to either JBP1 or JBP2 function in the J-null cell line indicated that JBP2 preferentially stimulated J synthesis within the telomere and sub-telomeric repeat regions. While JBP1 is able to stimulate low levels of J within these regions, it primarily stimulated de novo J at specific genome-internal sites that flank Pol II PTU. The inability of JBP2 to stimulate de novo J synthesis at ∼90% of these sites emphasizes the different substrate affinities of the two TH enzymes. What this substrate is, or what directs JBP function to a specific site remains unknown. Whether any substrate preference is driven by sequence, chromatin structure, or a combination of both is unclear at present.

Figure 5.

Regulation of J biosynthesis by JBP1 and JBP2. (A) JBP1 is unable to function optimally in the telomeric environment due to presence of hypothetical specific chromatin structure or epigenetic mark (represented by the red circles). However, JBP2 is able to bind and remodel chromatin via its SWI/SNF domain. The domain structure of JBP1 and JBP2 is shown above. The TH domain of JBP2 then hydroxylates thymidine, forming the intermediate HOMedU, which is converted to J by an unidentified glucosyltransferase (not shown). This seeds de novo J at specific sites within the sub-telomeric environment. JBP1 is then able to bind the modified base via its J-binding domain and hydroxylate adjacent thymine residues, amplifying J levels at JBP2-dictated sites. (B) JBP1 is able to recognize and bind unmodified DNA at regions flanking pol II PTUs and hydroxylate thymidine, stimulating de novo J synthesis. The high affinity of JBP1 for J-DNA drives propagation of J synthesis within these regions. While JBP2 is initially unable to bind and function at these regions of the genome, the enzyme is essential for overall JBP1 function at these sites. As discussed below, JBP2 is needed to modify chromatin substrate in these regions that have become inaccessible to JBP1, and allow the maintenance of J biosynthesis. (C) When expressed alone, JBP1 is able to function in J synthesis, but over time its enzymatic activity/efficiency is reduced, and J levels diminish (D). We believe this reflects a change in chromatin structure following J synthesis. Initially, chromatin in the J-null has an ‘open’ conformation (C) and JBP1 is able to access thymidine (and J) and stimulate de novo synthesis and maintenance of J. Consequently, the presence of J induces a conformational change or epigenetic mark such that the chromatin is more ‘closed’ and JBP1 can no longer access substrate efficiently (D). J synthesis is therefore compromised and J is lost over time. This ‘epigenetic mark’ is stable and present even once base J has been lost from the genome. In the case of WT cells (B) or J-null + JBP1 + JBP2 (E), JBP2 provides substrate access through its chromatin remodeling activity and ability to hydroxylate ‘non-JBP1 accessible’ thymidine residues. T, thymidine; J, base J; TH, thymidine hydroxylase domain; blue circles, TH domain; orange circle, SWI/SNF domain; purple circle, J-DNA binding domain; DNA, black lines; red circles, modified nucleosome/ epigenetic mark preventing JBP1 function; green circles, JBP2-induced chromatin remodeling allowing JBP1 to function (i.e. access DNA substrate).

The inability of JBP1 to maintain stable J synthesis in the J-null cell line (and the JBP2–/–) identifies the importance of both TH enzymes in the biosynthesis pathway. JBP1 initially induces high levels of J synthesis, which it is unable to maintain, demonstrating that J–DNA substrate is neither necessary (at least initially) nor sufficient for JBP1 function. We believe that the inability of JBP1 to maintain stabile synthesis reflects a change in chromatin structure or nucleosome modification or epigenetic marks, such that JBP1 can no longer function optimally. This epigenetic mark must be stable when J is lost from the genome. The presence of the modified base potentially alters the chromatin such that the ability of JBP1 to function optimally on the DNA substrate is compromised. This altered chromatin would inhibit the maintenance of J synthesis via binding J–DNA and modification of T during replication. Concomitant JBP2 expression alleviates the loss of JBP1 function at regions flanking Pol II PTU despite the apparent inability of JBP2 to stimulate de novo J within these regions. Presumably, the change in chromatin that is induced by JBP1 allows JBP2 recognition of the DNA substrate. JBP2 function in this context is critically dependent upon both the TH and SWI/SNF domain. We believe that the SWI/SNF domain opens up chromatin, allowing JBP1 to access T residues that become inaccessible after J synthesis. Interestingly, mutation in the TH domain also inhibited JBP2 function. Therefore, JBP2 may act not only through its ability to remodel chromatin, but also by its ability to hydroxylate T residues in JBP1-inaccessible sites.

Within the telomere, the original model of J biosynthesis, where JBP2 represents the de novo J factor and JBP1 the propagation factor remains applicable (Figure 5) as JBP2 stimulates much higher levels of telomeric J than does JBP1 when expressed in the null. Presumably, the telomeric regions are, even in the absence of J, in a chromatin structural context optimal for JBP2 function. When JBP1 is expressed in the context of JBP2, J levels are amplified. JBP1 stimulated propagation of J within these regions is enhanced by the increased affinity of the enzyme for J within repetitive DNA elements (18).

Ultimately, optimal J synthesis, as defined by level and localization of synthesis is critically dependent upon the presence of both JBP1 and JBP2. JBP1 requires JBP2 to ‘stabilize’ its function at Pol II PTU flanks, and JBP2 requires JBP1 to amplify the J levels in the telomeric environment. The specific nature of this codependence at Pol II PTU flanking regions is unknown, but it appears not to be through direct interaction of the two proteins (unless the interaction if transient and unable to be detected by a pull-down assay). We suggest that this codependence is based on the ability of JBP2 to provide an optimal DNA substrate for JBP1 function by modifying chromatin structure and/or stimulating the synthesis of low levels of base J.

Pol II transcription initiation and termination regions are enriched for base J

As opposed to most eukaryotes, transcription in trypanosomes (and all kinetoplastids) is primarily polycistronic, with long arrays of genes assembled into PTU Genes within one PTU are transcribed from the same strand. Adjacent PTU can be either transcribed from opposing DNA strands (divergent or convergent), or from the same strand and organized in a head-to-tail fashion. All mRNAs corresponding to a PTU are processed post-transcriptionally by a splicing reaction, which adds a 39-nt leader to the 5′-end of every mRNA, and polyadenylation of the 3′-end of the mRNA (26). The polycistronic nature of Pol II transcription indicates the importance of post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms of gene expression, including RNA processing and protein translation. In fact, most, if not all, gene expression in this group of organisms is thought to occur at the level of RNA processing, stability and degradation (27). Our analysis has shown that the hyper-modified DNA base J is enriched at regions flanking Pol II PTU throughout the genome. This non-random distribution of J may be indicative of a specific biological function for the modified base in the bloodstream life-cycle stage of the parasite; namely the regulation of Pol II transcriptional initiation and termination. This finding may have direct implications for a strictly post-transcriptional model of regulated gene expression in kinetoplastids.

Base J is found in all kinetoplastids analyzed thus far, including L. major and T. cruzi. In L. major, it is thought that 98% of the J is localized in the telomeric repeats. Attempts to detect J within sub-telomeric regions or within the chromosome failed (8). We show here that J is also localized within the L. major chromosome at regions flanking Pol II PTU. Our previous localization of J in T. cruzi indicated that, similar to T. brucei, a significant fraction of J is localized within the telomeric and sub-telomeric regions (7). Recent analysis has indicated that J is also localized at Pol II flanking regions within the genome of T. cruzi (Ekanayake and Sabatini, in preparation). While genome-wide analysis needs to be performed in both L. major and T. cruzi, it appears that the localization of J throughout the genome at Pol II specific regions is a conserved modification within the kinetoplastida. The evolutionary maintenance of base J internally in the genome of the three species of kinetoplastids provides additional support for an important biological function for J in regulating Pol II transcription.

While evidence supporting the presence of defined promoters and promoter elements is lacking in trypanosomes, recent data have identified the enrichment of modified histones at regions flanking PTU. It has been suggested that these modified histones mark sites of transcriptional termination and initiation through the regulation of chromatin structure (23). The co-localization of base J and modified histones within these sites further supports a functional role of modified DNA in the regulation of Pol II transcription.

Methylation is an epigenetic DNA modification that is conserved in fungal, plant, invertebrate and mammalian DNA. Like base J, 5-MeC associates with repetitive DNA in eukaryotes, where it is has been proposed to serve to stabilize and silence transposable elements and other repeat sequences (28). Furthermore, 5-MeC has been proposed to play a role in transcriptional silencing by masking promoter elements (sequences), and thus blocking transcriptional initiation, via methyl-binding proteins or as a consequence of DNA methylation-induced heterochromatin formation. Given the association of J with regions flanking PTU, as well as its association with silent but not active VSG ES, it is tempting to propose a similar role for J is the regulation of gene transcription.

Recently, trypanosome DNA has been shown to contain very small amounts of 5-MeC, but its localization within the genome is unknown (29). 5-MeC was detected in both BF and procyclic life-cycle stages, in repetitive and non-repetitive DNA. Whether base J and 5MeC co-localize throughout the BF T. brucei genome remains to be determined, but preliminary evidence suggests that specific regions of the genome do contain both (Cliffe and Sabatini, unpublished data). The consequence of co-localization of these two epigenetic modifications of DNA in trypanosomes remains to be determined.

Our findings suggest that base J might play a role in transcription initiation and termination, although it is clearly not essential, in organisms where very little is understood concerning the regulation of Pol II transcription. The analysis of the T. brucei J-null cell line has failed to indicate a role of base J in regulating transcriptional silencing of the telomeric Pol I VSG ESs (Cliffe and Sabatini, unpublished data). However, preliminary whole-genome transcriptome analysis indicates that the loss of the modified base affects the regulation of Pol II PTU gene expression throughout the T. brucei genome (Cliffe and Sabatini, in preparation). It is possible that the modified DNA base has distinct biological roles at these two different regions of the genome. Further analysis of the J-null cell line should clarify the function of base J in kinetoplastid gene regulation.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grant numbers AI063523 to L.C., M.M., R.S. and AI021729 to T.N.S., G.A.M.C.). Funding for open access charge: NIH (063523).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Steve Hajduk, Piet Borst and members of the Borst laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. Anti-J antiserum and the JBP1-puran-neo construct were a gift from Piet Borst. The 70-bp probe was a gift from Richard McCulloch. The authors would like to thank Stephen Beverly for providing the initial L. major cell culture. We also would like to thank the students from the 2009 Biology of Parasitism course, for the initial identification of base J in L. major stand switch regions. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID or the NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borst P, Sabatini R. Base J: discovery, biosynthesis, and possible functions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;62:235–251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Leeuwen F, Taylor MC, Mondragon A, Moreau H, Gibson W, Kieft R, Borst P. beta-D-glucosyl-hydroxymethyluracil is a conserved DNA modification in kinetoplastid protozoans and is abundant in their telomeres [see comments] Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:2366–2371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Leeuwen F, Kieft R, Cross M, Borst P. Tandemly repeated DNA is a target for the partial replacement of thymine by beta-D-glucosal-hydroxymethyluracil in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000;109:133–145. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(00)00247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Leeuwen F, Wijsman ER, Kieft R, van der Marel GA, van Boom JH, Borst P. Localization of the modified base J in telomeric VSG gene expression sites of Trypanosoma brucei. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3232–3241. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.23.3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor JE, Rudenko G. Switching trypanosome coats: what′s in the wardrobe? Trends Genet. 2006;22:614–620. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertz-Fowler C, Figueiredo LM, Quail MA, Becker M, Jackson A, Bason N, Brooks K, Churcher C, Fahkro S, Goodhead I, et al. Telomeric expression sites are highly conserved in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekanayake DK, Cipriano MJ, Sabatini R. Telomeric co-localization of the modified base J and contingency genes in the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6367–6377. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Genest PA, Ter Riet B, Cijsouw T, van Luenen HG, Borst P. Telomeric localization of the modified DNA base J in the genome of the protozoan parasite Leishmania. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2116–2124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genest PA, Ter Riet B, Dumas C, Papadopoulou B, van Luenen HG, Borst P. Formation of linear inverted repeat amplicons following targeting of an essential gene in Leishmania. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:1699–1709. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vainio S, Genest PA, Ter Riet B, van Luenen H, Borst P. Evidence that J-binding protein 2 is a thymidine hydroxylase catalyzing the first step in the biosynthesis of DNA base J. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2009;164:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cross M, Kieft R, Sabatini R, Wilm M, de Kort M, van der Marel G, van Boom J, van Leeuwen F, Borst P. The modified base J is the target for a novel DNA-binding protein in kinetoplastid protozoans. EMBO J. 1999;18:6573–6581. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiPaolo C, Kieft R, Cross M, Sabatini R. Regulation of trypanosome DNA glycosylation by a SWI2/SNF2-like protein. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, et al. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cliffe LJ, Kieft R, Southern T, Birkeland SR, Marshall M, Sweeney K, Sabatini R. JBP1 and JBP2 are two distinct thymidine hydroxylases involved in J biosynthesis in genomic DNA of African trypanosomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1452–1462. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Z, Genest PA, Ter Riet B, Sweeney K, DiPaolo C, Kieft R, Christodoulou E, Perrakis A, Simmons JM, Hausinger RP, et al. The protein that binds to DNA base J in trypanosomatids has features of a thymidine hydroxylase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:2107–2115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieft R, Brand V, Ekanayake DK, Sweeney K, DiPaolo C, Reznikoff WS, Sabatini R. JBP2, a SWI2/SNF2-like protein, regulates de novo telomeric DNA glycosylation in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toaldo CB, Kieft R, Dirks-Mulder A, Sabatini R, van Luenen HG, Borst P. A minor fraction of base J in kinetoplastid nuclear DNA is bound by the J-binding protein 1. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;143:111–115. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabatini R, Meeuwenoord N, van Boom JH, Borst P. Recognition of base J in duplex DNA by J-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:958–966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glover L, Horn D. Repression of polymerase I-mediated gene expression at Trypanosoma brucei telomeres. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:93–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowell JE, Cross GA. A variant histone H3 is enriched at telomeres in Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell. Sci. 2004;117:5937–5947. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernards A, Van der Ploeg LH, Frasch AC, Borst P, Boothroyd JC, Coleman S, Cross GA. Activation of trypanosome surface glycoprotein genes involves a duplication-transposition leading to an altered 3′ end. Cell. 1981;27:497–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90391-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cross M, Kieft R, Sabatini R, Dirks-Mulder A, Chaves I, Borst P. J binding protein increases the level and retention of the unusual base J in trypanosome DNA. Mol. Microbiol. 2002;46:37–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel TN, Hekstra DR, Kemp LE, Figueiredo LM, Lowell JE, Fenyo D, Wang X, Dewell S, Cross GA. Four histone variants mark the boundaries of polycistronic transcription units in Trypanosoma brucei. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1063–1076. doi: 10.1101/gad.1790409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapler GM, Coburn CM, Beverley SM. Stable transfection of the human parasite Leishmania major delineates a 30-kilobase region sufficient for extrachromosomal replication and expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:1084–1094. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.3.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liang XH, Haritan A, Uliel S, Michaeli S. trans and cis splicing in trypanosomatids: mechanism, factors, and regulation. Eukaryot. Cell. 2003;2:830–840. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.5.830-840.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Günzl A, Vanhamme L, Myler PJ. Transcription in Trypanosomes: A Different Means to the End. In Trypanosomes – After the Genome. USA: Horizon Press, Pittsburgh, USA, Pittsburgh; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki MM, Bird A. DNA methylation landscapes: provocative insights from epigenomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:465–476. doi: 10.1038/nrg2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Militello KT, Wang P, Jayakar SK, Pietrasik RL, Dupont CD, Dodd K, King AM, Valenti PR. African trypanosomes contain 5-methylcytosine in nuclear DNA. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:2012–2016. doi: 10.1128/EC.00198-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berriman M, Ghedin E, Hertz-Fowler C, Blandin G, Renauld H, Bartholomeu DC, Lennard NJ, Caler E, Hamlin NE, Haas B, et al. The genome of the African trypanosome Trypanosoma brucei. Science. 2005;309:416–422. doi: 10.1126/science.1112642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.