Abstract

Objective

Vancouver, Canada has been the site of an epidemic of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among injection drug users (IDU). In response, the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU) initiated a peer-run outreach-based syringe exchange programme (SEP) called the Alley Patrol. We conducted an external evaluation of this programme, using data obtained from the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS).

Methods

Using generalised estimating equations (GEE) we examined the prevalence and correlates of use of the SEP among VIDUS participants followed from 1 December 2000 to 30 November 2003.

Results

Of 854 IDU, 233 (27.3%) participants reported use of the SEP during the study period. In multivariate GEE analyses, service use was positively associated with living in unstable housing (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.83, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.39 – 2.40), daily heroin injection (AOR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.01 – 1.70), daily cocaine injection (AOR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.03 – 1.73), injecting in public (AOR = 3.07, 95% CI: 2.32 – 4.06), and negatively associated with needle reuse (AOR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.46 – 0.92).

Conclusion

The VANDU Alley Patrol SEP succeeded in reaching a group of IDU at heightened risk for adverse health outcomes. Importantly, access to this service was associated with lower levels of needle reuse. This form of peer-based SEP may extend the reach of HIV prevention programmes by contacting IDU traditionally underserved by conventional syringe exchange programmes.

Keywords: injection drug use, syringe exchange, harm reduction, peer-driven approach, Vancouver

INTRODUCTION

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemics among people who inject drugs (IDU) remain a challenge globally (Mathers et al., 2008; UNAIDS, 2008). Although various evidence-based HIV prevention programmes for this population exist, (Farrell, Gowing, Marsden, Ling, & Ali, 2005; Needle et al., 2005; Wodak & Cooney, 2006), only 8% of IDU worldwide have access to HIV prevention initiatives (The Global HIV Prevention Working Group, 2007).

While a growing body of research demonstrates the effectiveness of HIV prevention service provision through peer-based outreach (Broadhead, Heckathorn, Grund, Stern, & Anthony, 1995; Broadhead et al., 1998; Grund et al., 1992; Latkin, 1998; Needle et al., 2005), the impact and reach of “drug user-initiated” HIV prevention programmes are seldom evaluated, primarily because such grass-root activities rarely incorporate rigorous evaluation activities (Friedman et al., 2007). Fortunately, in Vancouver, Canada, the existence of a prospective cohort study of IDU enabled us to conduct an external evaluation of a peer-run outreach-based syringe exchange programme (SEP) initiated by the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), a local drug user organisation.

VANDU Alley Patrol Syringe Exchange Programme

In the 1990s, Vancouver had an epidemic of HIV among IDU despite the presence of one of the largest SEPs in North America (Strathdee, Patrick, Currie et al., 1997). In autumn 2000, VANDU established the Alley Patrol, a novel peer-based outreach programme, designed to address gaps in conventional public health services by providing education on subjects such as HIV prevention as well as the means to prevent harm among those who used drugs in public spaces (Kerr et al., 2006). Approximately 20 trained volunteers paired up and distributed sterile injection equipment and condoms, collected used syringes, and provided harm reduction education to IDU in public places in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, where public drug use was concentrated. Each pair worked 4-hour shifts and received a small volunteer stipend ($20 CAD). Depending on funding, their patrol shifts ranged from two to five days a week during days or nights. The volunteers experienced many challenges while providing this support, such as finding IDU displaced during police crackdowns (Csete & Cohen, 2003; Eby, 2006). The programme ended in 2005, but several members later created the Injection Support Team. This provides support to IDU experiencing difficulty with injecting in the open drug scene.

METHODS

Data for this study were obtained from the Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS), an ongoing prospective cohort study of IDU recruited through self-referrals and street outreach since May 1996 (Tyndall et al., 2003; Wood et al., 2001). Eligibility criteria for participation include injecting drugs a minimum of once in the previous month, residing in the greater Vancouver region and providing written informed consent. Participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire and provide a blood sample at semi-annual follow-up visits so that drug use, HIV risk behaviour, and HIV incidence can be tracked longitudinally. The study has been approved by St. Paul’s Hospital and the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board. As the VANDU established the Alley Patrol programme, the VIDUS questionnaire was modified to examine whether study participants were obtaining syringes from Alley Patrol volunteers.

The present analyses included data from participants who completed follow-up visits between 1 December 2000 and 30 November 2003 and who reported having injected drugs during six months prior to their visits. The study period ending in November 2003 was chosen because after autunm of 2003, SEPs in Vancouver were radically changed by the opening of the supervised injection facility (Kerr, Tyndall, Li, Montaner, & Wood, 2005). The primary outcome of interest was the use of the VANDU Alley Patrol SEP during six months prior to the interviews. Explanatory variables were selected with the aim of evaluating the vulnerability of Alley Patrol SEP users to HIV infection and other forms of drug-related harm, and to evaluate potential impacts of the Alley Patrol SEP. These included age (continuous), gender, Aboriginal ancestry and HIV sero-status, as well as other relevant behaviours and activities during the previous six months: unstable housing; sex work; daily heroin and cocaine injection; injecting in public; injecting with others; requiring help injecting; having difficulty accessing sterile syringes; borrowing syringes; average needle reuse (>once vs. once); syringe disposal (unsafe vs. safe); and non-fatal overdose. All variables were coded dichotomously as yes or no, unless otherwise stated. Variable definitions were identical to earlier reports (DeBeck et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2003b).

First, we examined the rates of the VANDU Alley Patrol SEP use throughout the study period. The rate was derived as the proportion of individuals who accessed the SEP during a 6-month period over all individuals followed during that period. Next, we examined univariate associations between the explanatory variables and the use of the Alley Patrol SEP. Since the variables used for the analyses included serial measures for each subject, we used generalised estimating equations (GEE) (Lee, Herzog, Meade, Webb, & Brandon, 2007). We then applied an a priori-defined statistical protocol that examined factors associated with the use of the SEP. This was done by fitting a GEE multivariate logistic regression model that included all variables that were significantly associated with the use of the SEP at the p < 0.05 level in univariate analyses. All p-values were two-sided.

RESULTS

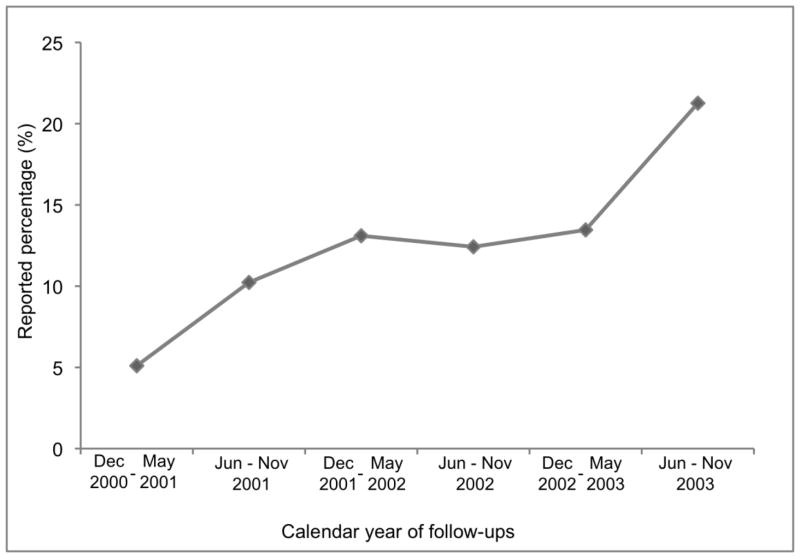

In total, 854 IDU were eligible for this analysis, including 350 (41.0%) females and 292 (34.2%) individuals of Aboriginal ancestry. The median age at baseline was 37.4 years (interquartile range (IQR): 29.2 – 44.2 years). In total, 233 (27.3%) participants reported obtaining syringes from VANDU Alley Patrol volunteers at some point during the study period. As shown in Figure 1, the proportions of IDU who accessed the Alley Patrol SEP steadily increased during the study period.

Figure 1.

Rates of self-reported use of the VANDU Alley Patrol SEP among active injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada (December 2000 - November 2003)

Table 1 presents the results of the univariate and multivariate GEE analyses of factors associated with the self-reported use of the SEP. In the multivariate GEE analyses, service use was associated with unstable housing (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR] = 1.83, 95% CI: 1.39 – 2.40), frequent heroin injection (AOR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.01 – 1.70), frequent cocaine injection (AOR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.03 – 1.73), injecting in public (AOR = 3.07, 95% CI: 2.32 – 4.06), and needle reuse (AOR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.46 – 0.92).

Table 1.

Univariate and multivariate GEE analyses of factors associated with accessing the VANDU Alley Patrol syringe exchange among a cohort of active injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada (study period December 2000 – November 2003; n = 854)

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p - value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P – value |

| Older age (per year older) | 0.97 (0.95 – 0.98) | <0.001 | 1.00 (0.98 – 1.01) | 0.681 |

| Gender (male vs. female) | 0.79 (0.59 – 1.04) | 0.095 | ||

| Aboriginal ancestry (yes vs. no) | 1.40 (1.05 – 1.86) | 0.022 | 1.24 (0.95 – 1.63) | 0.113 |

| HIV positivity (yes vs. no) | 1.23 (0.92 – 1.64) | 0.155 | ||

| Unstable housing*† (yes vs. no) | 2.04 (1.56 – 2.66) | <0.001 | 1.83 (1.39 – 2.40) | <0.001 |

| Sex work* (yes vs. no) | 1.71 (1.24 – 2.34) | <0.001 | 1.26 (0.91 – 1.74) | 0.162 |

| Heroin injection frequency* (≥1 per day vs. <1 per day) | 1.94 (1.51 – 2.49) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.01 – 1.70) | 0.039 |

| Cocaine injection frequency* ((≥1 per day vs. <1 per day) | 1.69 (1.31 – 2.18) | <0.001 | 1.34 (1.03 – 1.73) | 0.029 |

| Injected in public*§ (yes vs. no) | 3.47 (2.66 – 4.53) | <0.001 | 3.07 (2.32 – 4.06) | <0.001 |

| Injected with others*# (yes vs. no) | 1.28 (0.96 – 1.70) | 0.089 | ||

| Required help injecting* (yes vs. no) | 1.50 (1.17 – 1.93) | 0.001 | 1.30 (1.00 – 1.68) | 0.050 |

| Difficulty accessing syringes* (yes vs. no) | 1.27 (0.96 – 1.66) | 0.092 | ||

| Borrowed syringe* (yes vs. no) | 1.04 (0.73 – 1.47) | 0.836 | ||

| Average needle reuse* (>1 vs. 1) | 0.67 (0.48 – 0.94) | 0.020 | 0.65 (0.46 – 0.92) | 0.016 |

| Syringe disposal* (unsafe vs. safe)** | 0.71 (0.51 – 0.97) | 0.034 | 0.75 (0.54 – 1.04) | 0.080 |

| Non-fatal overdose* (yes vs. no) | 1.37 (0.88 – 2.14) | 0.163 | ||

GEE, generalized estimating equations; VANDU, Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users; CI, confidence interval.

denotes activities/events in the previous six months.

refers to living in a single room occupancy hotel, transitional living arrangements, or homelessness.

refers to bars, restaurants, parks, streets, public washrooms, parking lots, abandoned buildings, or other public settings.

refers to injecting drugs with somebody at least once in the previous six months.

Unsafe disposal refers to “threw it in the garbage or on the ground,” “gave it to another user,” or “flushed it down the toilet.” Safe disposal refers to “put it in: sharps containers, a safe place, syringe exchange, clinics or the Contact Centre.”

DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous studies of peer-based outreach HIV prevention programmes for IDU (Broadhead et al., 1998; Grund et al., 1992; Needle et al., 2005), our findings indicate that the VANDU Alley Patrol SEP succeeded in reaching a sub-population of local IDU at a high risk of HIV infection. Specifically, frequent cocaine injection has been shown to be strongly associated with HIV sero-conversion among IDU in Vancouver (Tyndall et al., 2003). Previous studies have also demonstrated that unstable housing (Corneil et al., 2006) and public injecting (DeBeck et al., 2009) are associated with elevated HIV risk in this setting. Of note is that the Alley Patrol SEP continued to serve this highly vulnerable population during periodic police crackdowns in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Eby, 2006). These crackdowns have been shown to have significantly decreased access to other local fixed-site SEPs (Csete & Cohen, 2003; Small, Kerr, Charette, Schechter, & Spittal, 2006; Wood et al., 2003a; Wood et al., 2004). The findings indicate further value of the Alley Patrol SEP in providing the equipment and support needed to reduce risks associated with unsafe injection practices.

Importantly, needle reuse was independently and negatively associated with the use of the VANDU Alley Patrol SEP, despite the fact that the IDU served by the SEP possessed several characteristics, such as unstable housing and frequent cocaine injection, that can increase the likelihood of needle reuse (Corneil et al., 2006; Strathdee, Patrick, Archibald et al., 1997; Wood et al., 2002; Wood et al., 2001). The Alley Patrol SEP, therefore, may have succeeded in reducing needle reuse among local IDU.

Our study has several limitations. We cannot infer causation from this observational study. Since VIDUS is not a random sample, our study findings may not be generalisable to other populations of IDU in Vancouver or other settings. The self-reported data may be affected by socially desirable reporting. However, since the participants and interviewers were blinded to the eventual use of the data, we believe it unlikely that socially desirable responding affected our findings. Lastly, it is unknown whether Alley Patrol SEP users would have simply used other SEPs in the local area if the Alley Patrol did not exist.

In sum, we found that the VANDU Alley Patrol SEP succeeded in reaching IDU at heightened risk for adverse health outcomes. Importantly, access to this service was associated with lower levels of needle reuse. These findings point to the important role that drug user-led initiatives can play in extending the reach of conventional public health programmes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would particularly like to thank the VIDUS participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. The authors would also like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance. The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (R01DA011591-04A1) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-67262). TK is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. KH is supported by a University of British Columbia Doctoral Fellowship.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kanna Hayashi, Email: kanna.hayashi@gmail.com.

Evan Wood, Email: uhri-ew@cfenet.ubc.ca.

Lee Wiebe, Email: stayoutin@yahoo.ca.

Jiezhi Qi, Email: jqi@cfenet.ubc.ca.

Thomas Kerr, Email: uhri-tk@cfenet.ubc.ca.

References

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Grund JPC, Stern LS, Anthony DL. Drug users versus outreach workers in combating AIDS: preliminary results of a peer-driven intervention. Journal of Drug Issues. 1995;25(3):531–564. [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead RS, Heckathorn DD, Weakliem DL, Anthony DL, Madray H, Mills RJ, et al. Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(Suppl 1):42–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneil TA, Kuyper LM, Shoveller J, Hogg RS, Li K, Spittal PM, et al. Unstable housing, associated risk behaviour, and increased risk for HIV infection among injection drug users. Health Place. 2006;12(1):79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csete J, Cohen J. A busing the user: police misconduct, harm reduction and HIV/A IDS in Vancouver. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- DeBeck K, Small W, Wood E, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Public injecting among a cohort of injecting drug users in Vancouver, Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(1):81–86. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.069013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eby D. The political power of police and crackdowns: Vancouver’s example. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell M, Gowing L, Marsden J, Ling W, Ali R. Effectiveness of drug dependence treatment in HIV prevention. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(Supplement 1):67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, de Jong W, Rossi D, Touze G, Rockwell R, Des Jarlais DC, et al. Harm reduction theory: Users’ culture, micro-social indigenous harm reduction, and the self-organization and outside-organizing of users’ groups. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18(2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grund JP, Blanken P, Adriaans NF, Kaplan CD, Barendregt C, Meeuwsen M. Reaching the unreached: targeting hidden IDU populations with clean need les via known user groups. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1992;24(1):41–47. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1992.10471617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Small W, Peeace W, Douglas D, Pierre A, Wood E. Harm reduction by a “user-run” organization: A case study of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VAN DU) International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr T, Tyndall M, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Safer injection facility use and syringe sharing in injection drug users. Lancet. 2005;366(9482):316–318. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA. Outreach in natural settings: the use of peer leaders for HIV prevention among injecting drug users’ networks. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(Suppl 1):151–159. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Herzog TA, Mead e CD, Webb MS, Brandon TH. The use of GEE for analyzing longitudinal binomial data: a primer using data from a tobacco intervention. Addict Behav. 2007;32(1):187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. The Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle RH, Burrows D, Friedman SR, Dorabjee J, TouzÈ G, Badrieva L, et al. Effectiveness of community-based outreach in preventing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2005;16(Supplement 1):45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: Evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2006;17(2):85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Archibald CP, Ofner M, Cornelisse PG, Rekart M, et al. Social determinants predict needle-sharing behaviour among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction. 1997;92(10):1339–1347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, Cornelisse PG, Rekart ML, Montaner JS, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11(8):F59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Global HIV Prevention Working Group. Bringing HIV prevention to scale: an urgent global priority. 2007 Retrieved November 12, 2009, from http://www.globalhivprevention.org/pdfs/PWG-HIV_prevention_report_FINAL.pdf.

- Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P, Li K, Wood E, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003;17(6):887–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak A, Cooney A. Do needle syringe programs reduce HIV infection among injecting drug users: a comprehensive review of the international evidence. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41(6–7):777–813. doi: 10.1080/10826080600669579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Small W, Jones J, Schechter MT, Tyndall MW. The impact of a police presence on access to needle exchange programs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003a;34(1):116–118. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309010-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Kerr T, Spittal PM, Small W, Tyndall MW, O’Shaughnessy MV, et al. An external evaluation of a peer-run “unsanctioned” syringe exchange program. Journal of Urban Health. 2003b;80(3):455–464. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Spittal PM, Small W, Kerr T, Li K, Hogg RS, et al. Displacement of Canada’s largest public illicit drug market in response to a police crackdown. CMAJ. 2004;170(10):1551–1556. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, Li K, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, et al. Factors associated with persistent high -risk syringe sharing in the presence of an established needle exchange programme. AIDS. 2002;16(6):941–943. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200204120-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, Li K, Kerr T, Hogg RS, et al. Unsafe injection practices in a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver: could safer injecting rooms help? CMAJ. 2001;165(4):405–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]