Abstract

Background

Cervical degenerative pathology produces pain and disability, and if conservative treatment fails, surgery is indicated. The aim of this study was to determined whether anterior decompression and interbody fusion according to Cloward is effective for treating segmental cervical degenerative pathology and whether the results are durable after a 10-year-minimum follow-up.

Materials and methods

Fifty-one patients affected by single-level cervical degenerative pathology between C4 and C7 were surgically treated by the Cloward procedure. Clinical evaluation was rated using the Neck Disability Index (NDI) and the visual analog scale (VAS). At last follow-up, the outcomes were rated according to Odom’s criteria. On radiographs, the sagittal segmental alignment (SSA) of the affected level and the sagittal alignment of the cervical spine (SACS) were measured.

Results

Average NDI was 34 preoperatively and 11 at last follow-up. Average VAS was 7 preoperatively and 1 at last follow-up. According to Odom’s criteria, the outcome was considered excellent in 18 cases, good in 22, and fair in 11. Average SSA was 0.5 ± 2.1 preoperatively, 1.8 ± 3.8 at 6 months, and 1.8 ± 5.7 at last follow-up. Average SACS was 16.5 ± 4.0 preoperatively, 20.9 ± 5.8 at 6 months, and 19.9 ± 6.4 at last follow-up. Degenerative changes at the adjacent levels were observed in 18 patients (35.3%).

Conclusions

The Cloward procedure proved to be a suitable and effective technique for treating segmental cervical degenerative pathology, allowing good clinical and radiographic outcomes even at a long-term follow-up.

Keywords: Cervical spondylosis, Cervical disc herniation, Single level, Surgical treatment, Cloward procedure, Long-term follow-up

Introduction

Cervical disc herniation and cervical spondylosis are common causes of acquired disability in patients over 50 years [1]. These two clinical pathologies can lead to different conditions ranging from axial neck pain to cervical radiculopathy and cervical myelopathy. In most patients, conservative treatment is sufficient to address symptoms [2]. Surgery is indicated if conservative treatment fails, leaving intractable pain, worsening radiculopathy, and myelopathy [3–5].

The main aim of surgical intervention is decompression, and historically, it has been attempted by either an anterior or posterior route with or without associated fusion [2, 3, 6–12]. Cervical decompression via an anterior approach associated with an interbody fusion is widely used and is the surgery of choice for neural compressions by the anterior structures in both single- and double-level surgeries [2, 9, 11, 13–17]. Anterior approach to cervical spine degeneration, first described by Robinson and Smith [18] and Cloward [19–21], has been widely used by many surgeons, with satisfactory short-term results [2, 9, 11, 13–17]. Despite the good clinical outcomes, some authors reported degenerative changes at disc spaces adjacent to the fused segment and lower clinical outcomes at long-term follow-up [22–24].

The aim of this study was to report clinical and radiological results of 51 patients operated on with discectomy and one-level anterior cervical fusion according to the Cloward procedure, with a minimum 10-year follow-up. We determined whether this procedure is effective for treating cervical disc herniation and cervical spondylosis in terms of postoperative recovery of the cervical sagittal alignment and symptoms relief. We also analyzed whether the clinical and radiographic results were durable after a 10-year-minimum follow-up.

Materials and methods

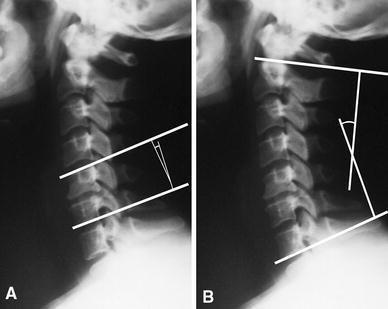

The study population consisted of 51 patients (seven women, 44 men) aged between 35 and 55 (mean 46) years who were affected by a single-level cervical disc disease between C4 and C7 and underwent surgery between 1985 and 1995. The operated levels were C4–C5 in 23 patients (45.1%), C5–C6 in 16 (31.4%), and C6–C7 in 12 (23.5%). Patients were included in the study according to the following criteria: single-level disease with absence of evident radiographic degenerative changes at adjacent levels above or below according to Kellgreen and Lawrence criteria [25]. Exclusion criteria were history of cervical spine trauma or previous cervical spine fractures and chronic systemic illnesses such as diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and neurodegenerative diseases. All patients were clinically and radiographically evaluated before surgery. Clinical evaluation included complete patient history and careful physical examination, including evaluation of strength and sensory and reflex response and assessment of pain, functional impairment, and disabilities. Clinical findings were then rated using the Neck Disability Index (NDI) [26, 27], and the visual analog scale (VAS) [28] from 0 to 10 (0 represents absence of pain and 10 represents maximum pain). Radiographic evaluation consisted of standard anterior–posterior and lateral cervical spine X-rays. On lateral images, the alignment of the affected intervertebral disc space [sagittal segmental alignment (SSA)] and the sagittal alignment of the whole cervical spine (SACS) were measured. The SSA was defined as the angle between the line parallel to the upper vertebral endplate of the proximal vertebra to the involved disc space and the line parallel to the lower vertebral endplate of the underlying vertebra (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, the SACS describes the sagittal alignment of the entire cervical spine and is defined as the angle between a line parallel to the upper facet joint of C2 and the line parallel to the lower vertebral endplate of C7 (Fig. 1b). These values were considered positive in lordosis and negative in kyphosis.

Fig. 1.

a Sagittal segmental alignment (SSA) angle and b sagittal alignment of the cervical spine (SACS) angle

In all patients, anterior surgery consisted of anterior cervical decompression and fusion according to the Cloward procedure [19]. Briefly, surgery is undertaken under general anesthesia with patients in the supine position with a slightly hyperextended neck. Before the spinal procedure, a bicortical iliac autograft was harvested from the anterior iliac crest. The surgical approach at the neck was performed through an anterior, oblique, skin incision. The trachea and esophagus were retracted medially and the neurovascular bundle with the sternocleidomastoid muscle laterally. After fluoroscopic confirmation of the affected level, a complete discectomy was performed. Finally, the previously harvested bone graft was placed into the intervertebral space under delicate extension. After surgery, anterior–posterior and lateral radiographs of the cervical spine were obtained. Postoperative immobilization consisted of plaster cast or neck collar for 40 days. All patients were clinically and radiographically evaluated preoperatively and a minimum of 10 years of follow-up (range 10–15 years). Clinical evaluations summarized with NDI and VAS were repeated at follow-up, and pre- and postoperative data were compared. At follow-up, patients were also evaluated according to Odom’s criteria [29], according to which, patients were rated from excellent to poor depending on resolution, improvement, or persistence of preoperative symptoms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Odom’s criteria

| Outcome | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Excellent | All preoperative symptoms relieved; abnormal findings improved |

| Good | Minimal persistence of preoperative symptoms; abnormal findings unchanged or improved |

| Fair | Definite relief of some preoperative symptoms; other symptoms unchanged or slightly improved |

| Poor | Symptoms and signs unchanged or exacerbated |

On lateral radiographs, cervical spine alignment was evaluated by SSA and SACS, and preoperative and postoperative data were compared. Moreover, the presence of degenerative changes at the levels adjacent to the fusion was evaluated according to Kellgreen and Lawrence [25]. The study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethical review board. Patients provided informed consent for enrollment.

Results

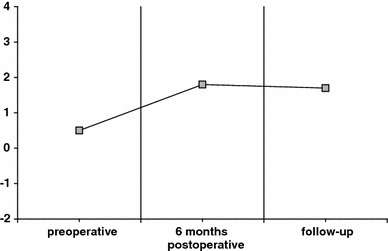

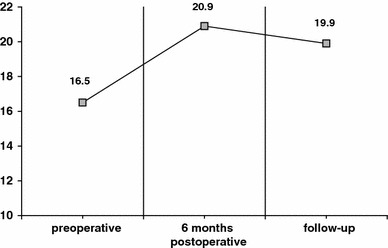

All patients healed uneventfully. Preoperatively, average NDI was 34 (range 31–50), at 6 months 13 (range 3–22), and at latest follow-up 11 (range 0–24). Average VAS was 7 (range 6–10) preoperatively, 2 at 6 months, and 1 (range 0–4) at final follow-up. According to Odom’s criteria, 18 patients presented excellent clinical outcome, 22 good, 11 fair, and none poor, demonstrating that at long-term follow-up, most patients showed clear relief of preoperative symptoms with subsequent functional improvement. Preoperatively, average SSA was 0.5 ± 2.1 and average SACS 16.5 ± 4.0. On 6 months postoperative radiographs, average SSA was 1.8 ± 3.8 and average SACS 20.9 ± 5.8. At last follow-up, average SSA was 1.7 ± 5.7 and average SACS 19.9 ± 6.4 (Figs. 2, 3). In all cases, an improvement of cervical sagittal alignment in terms of physiologic cervical lordosis recovery was achieved postoperatively compared with preoperative values.

Fig. 2.

Average sagittal segmental alignment (SSA) angle

Fig. 3.

Average sagittal alignment of the cervical spine (SACS) angle

Degenerative changes at the adjacent levels were observed in 18 patients (35.3%) (Fig. 4), whereas in the other 33 (64.7%), no signs of degeneration were found. Depending on the level of fusion, degenerative changes developed in nine patients who had C4–C5 fusion, six who had C5–C6 fusion, and three who had C6–C7 fusion. Of these 18 patients, five required conservative treatment, including the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and physical therapy. None of them required surgical revisions for such symptoms.

Fig. 4.

a Radiographic aspect at 12-year follow-up of a 61-year-old man treated with anterior decompression and fusion of the C5–C6 level, showing complete osteointegration of the bone graft with restoration of the physiologic lordosis and without radiographic evidence of degenerative changes at the levels adjacent. b Radiographic aspect at 13-year follow-up of a 59-year-old man treated with anterior decompression and fusion of the C6–C7 level. Early degenerative changes are noticeable at the C5–C6 level

Discussion

When conservative treatment for cervical disc herniation and cervical spondylosis fails, surgical treatment is indicated, and anterior decompression and fusion are considered as the treatment of choice [11, 13, 14, 17, 30–32]. The Cloward procedure proved to be a suitable and effective technique for treating segmental cervical degenerative pathology. In this series, with the use of carefully conducted Cloward procedure, improvement in sagittal alignment of the cervical spine with recovery of physiologic lordosis was obtained. In these patients, recovery of sagittal alignment was consistent with favorable clinical and radiographic outcomes at long-term follow-up. In fact, comparison between preoperative and follow-up SSA and SACS angles demonstrated the effectiveness of the Cloward procedure in correcting cervical sagittal misalignment when degenerative changes produce cervical spine straightening or cervical kyphosis. Moreover, no significant changes in SSA and SACS angles were observed between postoperative values and those measured at follow-up, suggesting that the correction obtained with surgery was maintained, even on long-term follow-up. Interestingly, no significant reabsorption or collapse of the bone graft occurred in the postoperative period. Radiographic evidence of degenerative changes at the levels adjacent to a previous fusion represent a frequent finding, even at long-term follow-up. However, it should be considered that disc degeneration represents the natural history of the aging cervical spine; therefore, it is not possible to explore the role of fusion in promoting this process. Most probably, in patients with preoperative evident adjacent disc degeneration, fusion increases degeneration rate; this occurs less frequently in patients with preoperatively intact discs, as in our study population. This has also been demonstrated in patients undergoing cervical spine arthroplasty surgery [33]. Moreover, even in patients with evident radiological adjacent disc degeneration, clinical symptoms remain scant and most often resolve conservatively. This result is in accordance with previous findings [8]. Finally, proper restoration of cervical alignment through a careful surgical technique and close decompression of the neural structures cannot be overemphasized [34].

In conclusion, spinal decompression and anatomic correction of cervical alignment, obtained with this technique, achieved resolution or significant improvement of clinical symptoms in most patients and allowed better exploitation of cervical spine residual function, counterbalancing the potential limitations imposed by the fused level.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Baba H, Furusawa N, Imura S, Kawahara N, Tsuchiya H, Tomita K. Late radiographic finding after anterior cervical fusion for spondylotic myeloradiculopathy. Spine. 1993;18:2167–2173. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199311000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey RW, Badgley CE. Stabilization of the cervical spine by anterior fusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42:565–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins AN, Colonel MC. Anterior cervical discectomy with and without interbody bone graft. J Neurosurg. 1944;44:290–295. doi: 10.3171/jns.1976.44.3.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwamura Y, Onari K, Kondo S, Inasaka R, Horii H. Cervical intradural disc herniation. Spine. 2001;26:698–702. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200103150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehlings MG, Arvin B. Surgical management of cervical degenerative disease: the evidence related to indications, impact and outcome. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:97–100. doi: 10.3171/2009.5.SPINE09210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kambin P. Anterior cervical fusion using vertical self-locking T-graft. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1980;153:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lunsford DL, Bissonette DJ, Janetta PJ, Sheptak PE, Zorub DS. Anterior surgery for cervical disc disease. J Neurosurg. 1980;53:1–11. doi: 10.3171/jns.1980.53.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boni M, Denaro V. Surgical treatment of cervical arthrosis. Follow-up review (2–13 years) of the 1st 100 cases operated on by anterior approach. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1982;68:269–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clements DH, O’Leary PF. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine. 1990;15:1023–1025. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199015100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herkowitz HN, Kurz LT, Overholt DP. Surgical management of cervical soft disc herniation. Spine. 1990;15:1027–1031. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199015100-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartolozzi P, Salvi M. Anterior surgery of the lower cervical spine. Chir Organi Mov. 1992;77:81–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Niu CC, Hai Y, Fredrickson BE, Yuan HA. Anterior cervical corpectomy and strut graft fusion using a different method. Spine J. 2002;2:179–187. doi: 10.1016/S1529-9430(02)00170-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cloward RB. The anterior surgical approach to the cervical spine: the Cloward procedure: past, present and future. Spine. 1988;13:823–827. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198807000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bohlman HH, Emery SE, Goodfellow DB, Jones PK. Robinson anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis for cervical radiculopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1298–1307. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palit M, Schofferman J, Goldthwaite N, Reynolds J, Kerner M, Keaney D, Lawrence-Miyasaki L. Anterior discectomy and fusion for the management of neck pain. Spine. 1999;24:2224–2228. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lofgren H, Johannsson V, Olsson T, Ryd L, Levander B. Rigid fusion after Cloward operation for cervical disc disease using autograft, allograft or xenograft: a randomized study with radiostereometric and clinical follow-up assessment. Spine. 2000;25:1908–1916. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200008010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vavruch L, Hedlund R, Javid D, Leszniewski W, Shalabi A. A prospective randomized comparison between the Cloward procedure and a carbon fiber cage in the cervical spine: a clinical and radiologic study. Spine. 2002;27:1694–1701. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200208150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson RA, Smith GW. Anterolateral cervical disc removal and interbody fusion for cervical disc syndrome. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1955;96:223–224. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloward RB. The anterior approach for removal of ruptured cervical disks. J Neurosurg. 1958;15:602–617. doi: 10.3171/jns.1958.15.6.0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cloward RB. Lesions of the intervertebral disks and their treatment by interbody fusion methods. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1963;27:51–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cloward RB. Complications of anterior cervical disc operation and their treatment. Surgery. 1971;69:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilibrand AS, Carlson GD, Palumbo MA, Jones PK, Bohlman HH. Radiculopathy and myelopathy at segments adjacent to the site of a previous anterior cervical arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:519–529. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199904000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CS, Cheng CK, Liu CL, Lo WH. Stress analysis of the disc adjacent to interbody fusion in lumbar spine. Med Eng Phys. 2001;23:483–491. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4533(01)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Espina CG, Amirouche F, Havalad V. Multilevel cervical fusion and its effect on disc degeneration and osteophyte formation. Spine. 2006;31:972–978. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000215205.66437.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kellgreen JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollard CA. Preliminary validity study of the pain disability index. Percept Mot Index. 1984;59:974. doi: 10.2466/pms.1984.59.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vernon H, Mior S. The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manip Physiol Ther. 1991;14:409–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scott J, Huskinsson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain. 1976;2:175–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(76)90113-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Odom GL, Finney W, Woodhall B. Cervical disc lesions. J Am Med Assoc. 1958;166:23–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.1958.02990010025006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Long-term result after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating. Spine. 2005;30:2138–2144. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000180479.63092.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samartzis D, Shen FH, Goldberg EJ, An HS. Is autograft the gold standard in achieving radiographic fusion in one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with rigid anterior plate fixation? Spine. 2005;30:1756–1761. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000172148.86756.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Macnab I. Cervical spondylosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975;109:69–77. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197506000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denaro V, Papalia R, Denaro L, Di Martino A, Maffulli N. Cervical spinal disc replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. 2009;91:713–719. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B6.22025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denaro V, Denaro L, Di Martino A, Longo UG, Maffulli N. Degenerative disk disease. In: Denaro L, D’Avella D, Denaro V, editors. Pitfalls in cervical spine surgery. Berlin: Springer; 2010. pp. 121–163. [Google Scholar]