Abstract

Cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) are famous for their ability to kill tumor, allogeneic and virus-infected cells. However, an emerging literature has now demonstrated that CTL also possess the ability to directly recognize and kill bacteria, parasites, and fungi. Here, we review past and recent findings demonstrating the direct microbicidal activity of both CD4+ and CD8+ CTL against various microbial pathogens. Further, this review will outline what is known regarding the mechanisms of direct killing and their underlying signalling pathways.

1. Introduction

The adverse consequences of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or T cell immunodeficiency provide evidence of the vital role of cytotoxic T-lymphocytes (CTL) in the immune response. Indeed, CTL are well-known elements of the immune response to virus-infected, tumour and allogeneic cells [1–3]. More recently, the role of CTL was expanded significantly when the ability to mediate direct killing of microbial pathogens was identified. Research defining the precise mechanisms underlying CTL killing of microbes, however, is still in its infancy. Remarkably, granulysin (in contrast to granzymes) has emerged as a fundamental mediator of microbial killing. The mode of action of granulysin appears to be through the disruption of membrane permeability [4]. It follows that granulysin has been found to insert into the microbial membrane through ionic interactions between the positively charged amino acid residues and negatively charged phospholipids. Insertion of granulysin in turn disrupts membrane permeability resulting in the influx of fluid into the cytoplasm and death by osmotic lysis [4]. Other mechanisms identified in the killing of tumor cells may also play a role, including Ca2+ influx and K+ efflux [5], and activation of a sphingomyelinase associated with the cell membrane to generate ceramide [6].

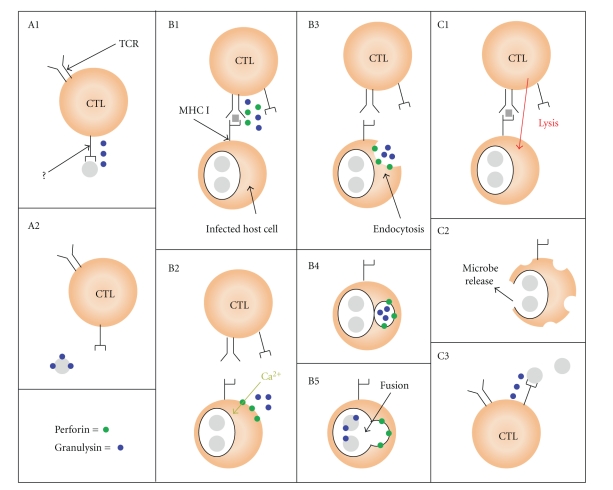

CTL killing of extracellular pathogens involves direct microbial recognition by the CTL (Figure 1(A)). In contrast to tumour and virus-infected cells, recognition of extracellular pathogens occurs through an apparent MHC-independent mechanism (as microbes have not been found to express MHC). Successful recognition induces the release of granulysin which may directly bind and kill the microbe. In the case of intracellular microbes, CTL must first bind to the infected host cell. These interactions, like recognition of tumor and virus-infected cells, are often MHC-restricted and antigen-specific. Binding triggers the release of granulysin, which must enter the infected host cell for microbial killing to occur (Figure 1(B)). This is thought to be mediated through perforin-generated pores in the host cell membrane. These pores facilitate the influx of extracellular Ca2+ which triggers the target cell to endocytose the damaged region of the membrane and internalize nearby granulysin [7–9]. Alternatively, CTL may mediate lysis of the infected host cells releasing microbes which may then be recognized and killed by nearby CTL (Figure 1(C)).

Figure 1.

Killing of extracellular and intracellular microbes by CTL. (A) CTL bind to an extracellular microbe (grey) via an unknown receptor (?) independently of MHC (panel A1). Binding triggers CTL to release granulysin (blue) which binds to and kills the microbe (panel A2). By contrast, CTL killing of intracellular microbes involves MHC-restricted antigen-specific recognition of infected host cells. (B) CTL-host cell interactions induce the release of perforin (green) and granulysin (panel B1). Perforin-generated pores in the host cell membrane facilitate the influx of extracellular Ca2+ which induces endocytosis of the membrane region damaged by perforin, along with nearby granulysin (panels B2–B4). Granulysin-containing endosomes fuse with intracellular compartments containing the microbe allowing granulysin to bind to and kill the microbe (panel B5). (C) Alternatively, CTL induce lysis of an infected host cell causing the release of intracellular microbes which are then killed by other nearby CTL (panels C1–C3).

To acquire microbicidal activity, T cells must be primed. This priming event can occur in response to cytokines such as T cell growth factors, stimulation by a mitogen, or antigen-specific responses. The receptors and signalling pathways involved in priming may be the same, but also might be quite distinct from the receptors and signalling that lead to immediate killing. Following the priming event, the microbicidal CTL is then ready to receive the signal that triggers them to kill the pathogen.

2. Direct Killing of Bacteria by CTL

One of the earliest studies describing bactericidal CTL came from investigations with Pseudomonas aeruginosa [10]. T cells from mice immunized with P. aeruginosa polysaccharide were stimulated with macrophages from nonimmune mice with or without the addition of heat-killed bacteria. The T cells were then able to kill live P. aeruginosa. Macrophages had to be present during the priming, but surprisingly, heat-killed bacteria did not. This suggested that the bactericidal activity of these T cells was dependent on their interaction with macrophages but did not require presentation of P. aeruginosa antigens. Supernatants collected from immune T cells exposed to macrophages and P. aeruginosa were found to kill P. aeruginosa in addition to Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli suggesting that these T cells were producing a soluble bactericidal product.

CTL have also been found to mediate killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through the release of bactericidal products [11–13]. M. tuberculosis growth was reduced as much as 74% in the presence of CD4+ CTL and 84% in the presence of CD8+ CTL [12]. When CD8+ CTL were pretreated with strontium chloride (which depletes granule contents), it caused a clear reduction in the ability to kill M. tuberculosis that correlated with a marked decrease in granulysin content [13]. In vitro, purified granulysin was able to kill extracellular M. tuberculosis in a dose-dependent fashion. However, killing of intracellular M. tuberculosis required the addition of perforin, which was not directly bactericidal, but was able to lyse M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages. Together this data suggests that perforin facilitates entry of granulysin into M. tuberculosis-infected cells where granulysin can access and kill the intracellular pathogen. In vivo studies have provided additional support for the conclusion that perforin is required for CD8+-mediated clearance of M. tuberculosis. In these studies, irradiated mice infected with M. tuberculosis were found to have a significantly greater bacterial load after receiving adoptively transferred perforin-deficient CD8+ T cells compared to wild-type CD8+ T cells [14].

However, for other bacteria, killing can occur independently of perforin. Studies conducted with Listeria innocua support a perforin-independent mechanism in which granulysin is actively taken up by the infected cell [15]. Both healthy and L. innocua-infected dendritic cells (DC) were found to take up recombinant granulysin in a temperature-sensitive manner, indicative of active internalization. Furthermore, cholesterol depletion abrogated granulysin uptake and killing of infected DC, suggesting lipid raft involvement. This was further supported by data showing colocalization of granulysin and cholera toxin (used as a marker of lipid rafts) during and shortly following uptake. Immunofluorescent microscopy showed granulysin trafficking through the endocytic pathway following internalization. Ninety minutes after uptake, granulysin was found to colocalize with phagosomes containing L. innocua DNA. Indeed, granulysin was found to kill both extracellular L. innocua and L. innocua-infected DC in a dose-dependent manner. While granulysin may function independently, perforin might also help. Another study found that perforin treatment (whether simultaneous or sequential to granulysin treatment) augmented granulysin-dependent killing of intracellular L. innocua which was not due to the formation of stable pores in the DC membrane [16]. Rather, perforin treatment was found to stimulate a transient change in the plasma membrane permeability (assessed by Ca2+ influx) that enhanced fusion of granulysin-containing endosomes with phagosomes containing L. innocua.

CTL killing of Mycobacterium leprae has also been found to involve granulysin. The highest level of expression of granulysin occurred in patients afflicted with the localized tuberculoid form, rather than the disseminated lepromatous form of the disease [17]. This correlation suggests that granulysin release by CTL may limit the spread and severity of M. leprae infection. Remarkably, granulysin expression was mostly limited to CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cell lines derived from tuberculoid leprosy lesions were found to lyse M. leprae infected macrophages and kill intracellular mycobacteria. Strontium treatment abrogated both the cytolytic and bactericidal activity of these CD4+T cells, which suggested that killing was mediated through the granule-exocytosis pathway. Blocking Fas using anti-Fas antibody also partially inhibited the cytolytic activity of two of four CD4+ T cell lines suggesting that the Fas-FasL pathway may also play a minor role in the lysis of M. leprae-infected cells. It follows that the extent of Fas-FasL mediated lysis may depend on the nature of the CTL [18] or the infected target cell [19].

3. Direct Killing of Parasites by CTL

Early studies with Schistosoma mansoni described the capacity of CTL to directly kill parasites [20]. T cells stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA), a mitogenic lectin, as well as various oxidative mitogens, antigens, and alloantigens were found to kill schistosomula. Killing was found to correlate with increased binding to schistosomula suggesting a contact-dependent mechanism. In support of this, supernatants from PHA-stimulated T cells were ineffective at killing, although the concentration of parasiticidal products in the supernatants may not have been high enough to mediate an appreciable response. Moreover, it remains unclear how PHA induces CTL parasiticidal activity. Removal of PHA prior to incubation of T cells with schistosomula was found to impair killing suggesting that PHA may have an ulterior function in addition to stimulating T cell activation and proliferation. CTL killing of Entameoba histolytica closely resembled that of Schistosoma mansoni in many respects [21]. First, nonspecific activation of T cells with PHA was found to significantly enhance killing of E. histolytica trophozoites compared to unstimulated T cells. PHA-stimulated T cells killed as many as 92% of trophozoites whereas amoebic viability in the presence of unstimulated T cells remained relatively unchanged [21]. Second, binding correlated with killing suggesting a contact-dependent mechanism. Third, and surprisingly, killing required the continuous presence of PHA, again alluding to direct participation. One possibility is that PHA bridges the T cells and E. histolytica. However, bridging the T cells and Entameoba cannot be the only mechanism by which PHA participates in killing because at least 18 hours of preincubation was required to elicit killing. Similarly, in studies with S. mansoni, pretreatment of schistosomula with PHA was not sufficient to induce parasiticidal activity of unstimulated T cells [20]. Thus, PHA appears to act both by activating the T cells as well as possibly functioning as a bridge for binding.

Specific activation of T cells isolated from patients with an amoebic liver abscess with an E. histolytica lysate also induced killing [22]. In contrast to prior studies with PHA [20, 21], stimulation with antigens from E. histolytica was found to augment binding intensity of T cells to the trophozoites rather than the binding frequency [22]. Thus, the more important determinants in killing amoeba may be the binding characteristics of the CTL rather than the number of CTL bound. The mechanism underlying the parasiticidal activity of these T cells is poorly understood. Anti-TNF-α antibody blocked killing of immune T cells from mice immunized against E. histolytica, although large doses of TNF-α did not directly kill the amoeba [23]. These results demonstrate the complexity of the system and the possible role of additional mediators.

CTL have also been reported to directly kill the pathogenic parasite Toxoplasma gondii. CD8+ T cells from mice immunized with P30 (a T. gondii membrane protein) and subsequently restimulated in vitro with P30 were found to kill extracellular T. gondii [24]. Unlike studies conducted with S. mansoni and E. histolytica [20, 21], killing of T. gondii appeared to be antigen specific. P30-antigen-specific splenocytes killed significantly more T. gondii than splenocytes stimulated with the mitogenic lectin, concanavalin A (ConA), despite greater T cell proliferation in response to ConA [24]. Although antigen stimulation resulting in microbicidal priming was likely to have been MHC-restricted, killing was direct. Since there is no evidence for expression of MHC or MHC-like molecules by T. gondii, this suggests that direct cytotoxicity was MHC-independent. MHC-unrestricted T cell killing of extracellular T. gondii has also been reported by others [25]. However, the mechanism by which antigen-specificity is accomplished in the absence of MHC is not yet defined.

CTL responses against intracellular T. gondii, on the other hand, have been found to proceed through an MHC-restricted mechanism [26]. Splenocytes from mice immunized against T. gondii mediated killing of both infected macrophages and intracellular T. gondii [26, 27]. These activities were found to be mediated by CD8+ T cells. Concanamycin, an inhibitor of the vacuolar ATPase that is required to maintain perforin in lytic granules, significantly impaired killing, implicating perforin in the response against T. gondii [27]. Indeed, perforin has been found to play a critical role in chronic toxoplasmosis. Perforin-deficient mice chronically infected with T. gondii were found to have a higher rate of mortality and a greater number of brain cysts compared to wild-type mice [28], although other studies came to disparate conclusions [29]. Moreover, the ability of CD8+ T cells to kill intracellular T. gondii is controversial. In one study, CD8+ T cells failed to kill T. gondii-infected B cells as assessed by quantitative PCR of the SAG-1 gene [30]. Further studies will be required to resolve the discrepancy between these studies.

Emerging from this uncertainly, Plasmodium falciparum is clearly killed directly by CTL. γδ T cells were found to kill blood-stage P. falciparum through a contact-dependent mechanism [31–33]. Killing appeared to be stage-dependent with extracellular merozoites being the suggested targets [31, 32]. In vitro studies revealed a correlation between the parasiticidal activity of the γδ T cells and expression of granulysin [33]. Treatment of the T cells with antigranulysin antibody abrogated this activity. Together, this data indicates that parasiticidal CTL mediate killing of P. falciparum via the release of granulysin.

4. Direct Killing of Fungi by CTL

Several studies have reported the ability of CTL to kill the opportunistic fungus Candida albicans. IL-2 stimulation of murine splenocytes was found to induce fungicidal activity against C. albicans as well as several other Candida species [34]. Anti-Candida activity required at least 3 days of priming with IL-2 and peaked at 7 days. The induction of fungicidal activity correlated with enhanced killing of an NK cell-resistant tumor cell line. Supernatants taken from IL-2 stimulated splenocytes had no effect on the growth of C. albicans suggesting a contact-dependent fungicidal mechanism. IL-2 stimulated human PBMC were also found to inhibit the growth of C. albicans. Moreover, another study found that the CD8+ T cells, and not NK1.1+ cells (NK cells), mediated fungicidal activity against C. albicans in response to IL-2 [35].

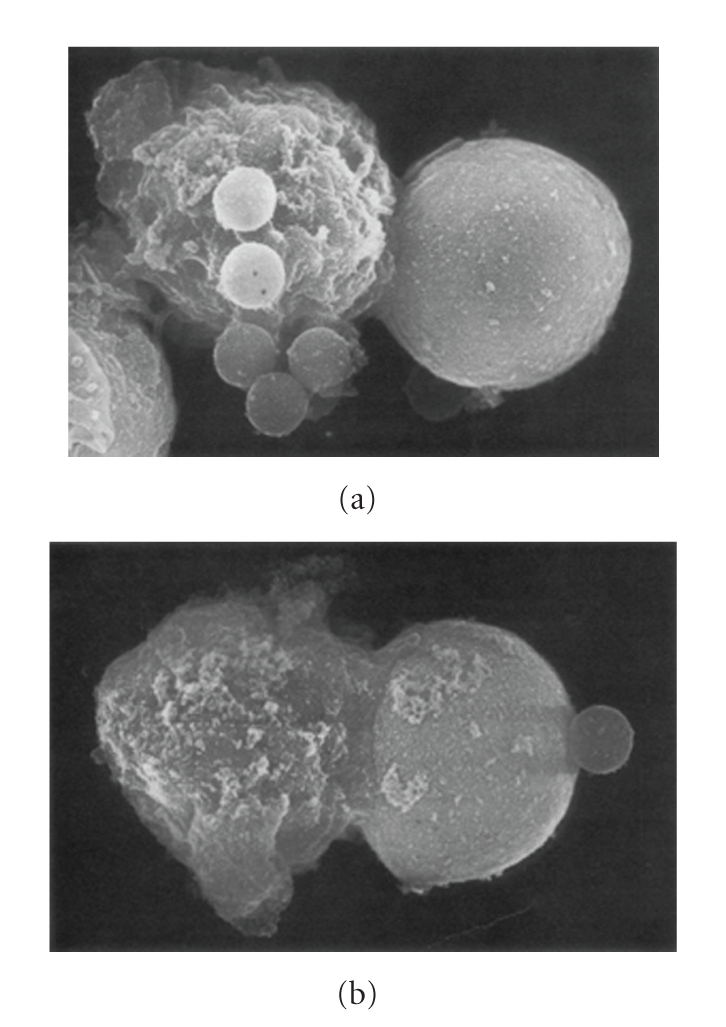

The CTL response against the yeast-like pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans has been described extensively. In one of the earlier studies, lymphoid cells were isolated after mice had been immunized with heat-killed C. neoformans in complete Freund's adjuvant [36]. The anticryptococcal activity of these cells was measured by assessing colony forming units, and delayed-type hypersensitivity was assessed by footpad swelling following administration of C. neoformans antigen. Only lymphoid cells from immunized mice were found to inhibit the growth of C. neoformans. Growth inhibition reached as high as 60–80% as assessed by CFU [36]. Furthermore, the magnitude of the anticryptococcal activity correlated with the intensity of the delayed-type hypersensitivity response. T cells within the peripheral lymphoid compartment were found to be the mediators of the anticryptococcal activity [36]. In another study, T cells were observed to interact directly with C. neoformans in vitro suggesting a contact-dependent mechanism of killing (Figure 2) [37]. However, between 11 and 35% of T cells were found to bind to C. neoformans suggesting recognition by a receptor other than the T cell receptor. Other studies reported similar killing with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) stimulated with dead C. neoformans [38] or cultured for 7 days with IL-2 and GM-CSF (but not with TNF, IFN-γ, or vitamin D3) [39]. In agreement with prior studies [36, 37], T cells (as well as NK cells) isolated from the PBMC were found to directly bind to, and possess fungicidal activity against C. neoformans after priming with IL-2 [40]. Another study found that freshly isolated T cells could mediate killing of C. neoformans without the need for IL-2 stimulation [41]. However, T cells cultured without IL-2 soon lost their ability to kill, suggesting that IL-2 is required for T cells to maintain their fungicidal activity. Treatment of T cells with the proteases trypsin and bromelain, which have been found to cleave several receptors on T cells [42], also impaired killing of C. neoformans suggesting that receptor-ligand interactions were involved in anticryptococcal activity [41].

Figure 2.

Scanning electron micrographs of conjugates formed between T cells (left) and C. neoformans (right). Magnification in both panels is ×16,370. Cells in (a) were labelled with mouse monoclonal anti-CD3 antibody followed by goat antimouse IgG bound to latex beads. Latex beads are seen attached to the effector cell (a). Cells in (b) were labelled with UPC10 as a control IgG2a followed by goat antimouse IgG conjugated to latex beads. One latex bead is seen associated with the cryptococcal cell; however, no beads attached to the effector cell (b).

Investigators have asked whether CTL kill Cryptococcus or exert their anticryptococcal activity by inhibiting the growth of the organism. Studies using the viability dye 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) showed that C. neoformans failed to demonstrate metabolic activity after incubation with T cells [43]. C. neoformans also becomes permeable and labels with propidium iodide after incubation with CTL providing further evidence for killing (unpublished observations, Anowara Islam). Furthermore, CTL can reduce the burden of organisms below the starting innocula [41, 44], and consistent with previous studies that suggested a contact-dependent mechanism of killing, separation of T cells and C. neoformans with a porous membrane during incubation was found to abrogate anticryptococcal activity [43]. Thus, the burden of evidence is that killing occurs.

4.1. Effector Mechanisms Used by CTL to Kill Fungi

Early studies investigating the mechanism of CTL anticryptococcal activity examined possible receptors and effector mechanisms. Antibody-mediated blockade of various T cell surface molecules such as LFA-1 and CD3 did not significantly inhibit killing [45]. Similar results were found using putative ligands to block mannose and hyaluronate receptors. Together this data suggests that CTL killing of C. neoformans may proceed through a novel receptor that is yet to be identified.

These early studies also examined the role of reactive hydroxyl radicals [45], which have been suggested to play a role in eosinophil-mediated killing [46]. Additionally, cyclooxygenase inhibitors and prostaglandin E2, which have been found to inhibit NK cell cytotoxicity [47, 48] and NF-κB activation [49], were assessed. Among the 3 hydroxyl radical scavengers used, only catechin was found to impair killing of C. neoformans [45]. Similarly, only 1 (salicylic acid) of the 3 cycloxygenase inhibitors abrogated killing, while prostaglandin E2 failed to have any appreciable effect. One study, however, described an effector mechanism by which IL-15 stimulated CD8+ CTL kill C. neoformans [44]. In vitro studies have previously shown that IL-15 from C. neoformans-stimulated monocytes induced T cells to become anticryptococcal [50]. This led to studies showing that the anticryptococcal activity of IL-15-stimulated CD8+ T cells correlated with the level of granulysin expression [44]. Furthermore, both strontium treatment and siRNA knockdown of granulysin abrogated anticryptococcal activity, directly implicating granulysin in the CTL response against C. neoformans. Perforin was not required, as neither concanamycin A nor EGTA treatment impaired anticryptococcal activity. These results are in contrast to NK cells, which depend on perforin, but not granulysin for killing [51].

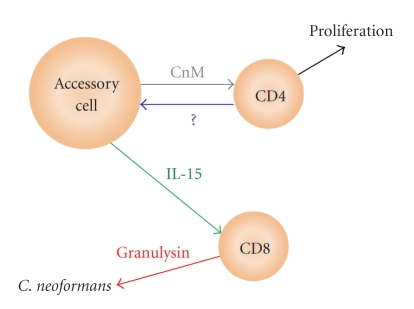

These results were extended using CD8+ T cells purified from PBMC that had been stimulated with C. neoformans mitogen (CnM) [44], a protein mitogen within the cryptococcal cell wall and membrane [52, 53]. Priming of anticryptococcal activity and granulysin expression by stimulation with CnM was dependent on CD4+ T cells [44]. Stimulation of PBMC with CnM in the presence of anti-IL-15 abrogated anticryptococcal activity and granulysin expression suggesting that the dependence on CD4+ T cells was mediated through IL-15. However, in the absence of accessory cells, CD4+ T cells were not sufficient to induce CD8+ T cell anticryptococcal activity and granulysin expression. Together this data suggests that the proliferating CD4+ T cells provide a retrograde stimulus to accessory cells that results in production of IL-15, which then primes CD8+ T cell for granulysin expression and anticryptococcal activity (Figure 3) [44]. Indeed, both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo have been found to be indispensable for an effective response to C. neoformans [54–58].

Figure 3.

CD8+ T cells are primed for microbicidal activity following stimulation with C. neoformans mitogen (CnM). Recognition of CnM (presented by accessory cells) by CD4+T cells triggers their activation and proliferation. Meanwhile, a reciprocal signal from CD4+T cells mediated through an unknown receptor-ligand interaction (?) induces accessory cells to express IL-15, which in turn primes CD8+ T cells for granulysin expression and anticryptococcal activity.

Aside from their role in licensing accessory cells to prime CD8+ CTL anticryptococcal activity [44], CD4+ T cells have also been demonstrated to directly kill C. neoformans [59]. Upon stimulation with IL-2, CD4+ T cells increased the expression of granulysin (but not perforin) which correlated with increased fungicidal activity. Both strontium treatment and granulysin siRNA knockdown abrogated CD4+ T cell killing of C. neoformans. Perforin involvement was excluded as neither concanamycin A nor perforin knockdown could interfere with anticryptococcal activity of CD4+ T cells stimulated with both IL-2 and anti-CD3 antibody (which stimulated both perforin and granulysin expression). Together this data suggests that CD4+CTL (like CD8+) directly kill C. neoformans through a granulysin-mediated mechanism.

The high prevalence of serious cryptococcal infection in HIV-infected patients [60, 61] may be at least partially due to a defect in this fungicidal activity. Indeed, CD4+ T cells from these patients were found to exhibit defective killing of C. neoformans [59]. Neither IL-2 nor IL-2 plus anti-CD3 stimulation could induce granulysin expression in these patients' cells. Furthermore, stimulation with IL-2 alone was sufficient to induce perforin expression. These results suggest that profound dysregulation of perforin and granulysin expression may account for the failure of CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected patients to kill C. neoformans.

4.2. Signalling Pathways Used by CTL to Kill Fungi

The signalling pathways regulating granulysin expression in CD8+ and CD4+ CTL are relatively unknown. In preparation for killing of fungi, CD4+ T cells were stimulated with IL-2, which resulted in expression of granulysin [62]. Expression of granulysin correlated with short-term (0–60 min) and long-term (1–5 days) phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK)1/2, p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, and p54 c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) as well as the transcription factor signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT)5. Meanwhile, no phosphorylation of the human oncogene Akt (signifying phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activation) could be detected following continuous IL-2 stimulation. Akt phosphorylation could only be detected when CD4+ T cells were stimulated with IL-2 for 3–5 days, rested (24 hours) and restimulated with IL-2 for 5 min, indicating that PI3K undergoes a transient activation after initial stimulation with IL-2. Continuous stimulation of CD4+ T cells with IL-2 was also found to increase expression of the IL-2Rα and IL-2Rβ subunits of the IL-2 receptor (by day 3) followed by expression of granulysin (on day 5). Pharmacological inhibition of Janus kinase (JAK)3/STAT5 or PI3K abrogated both granulysin expression and anticryptococcal activity of IL-2 stimulated CD4+ T cells, which correlated with decreased expression of the IL-2R subunits. Together this data suggests that granulysin expression requires acquisition of one or more of the IL-2R subunits. Indeed, blockade of IL-2Rβ expression using anti-IL-2Rβ antibodies or siRNA knockdown abrogated granulysin expression in IL-2 stimulated CD4+ T cells. Thus, IL-2 (and perhaps other T cell growth factors) signals T cells to increase expression of IL-2Rβ, which is then available for signalling that is necessary for granulysin expression.

Previous studies have shown that CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected patients exhibit dysregulated expression of perforin and granulysin [59]. Comparison of IL-2 signalling in CD4+ T cells from healthy donors and patients infected with HIV revealed the underlying cause to be defective STAT5 and PI3K signalling [62]. IL-2 stimulation of CD4+ T cells from HIV-infected patients failed to induce phosphorylation of STAT5 and failed to increase expression of IL-2Rβ. Furthermore, in contrast to CD4+ T cells from healthy donors, IL-2 failed to induce phosphorylation of Akt. Together these results demonstrate a critical role for JAK/STAT and PI3K signalling in granulysin-mediated killing of C. neoformans by CD4+ T cells.

The response in CD8+ T cells is similar. In a recent study, JAK/STAT signalling was also found to be required for granulysin expression in CD8+ T cells in response to IL-15 and IL-21 [63]. CD8+ T cells stimulated with either IL-15 or IL-21 were found to increase granulysin expression, which correlated with increased phosphorylation of STAT3 and STAT5. IL-15 was found to induce phosphorylation of both STAT3 and STAT5, while IL-21 only induced phosphorylation of STAT3. Pharmacological inhibition and siRNA knockdown of JAK/STAT signalling was found to abrogate granulysin expression by CD8+ T cells in response to IL-15 and IL-21. Together this data indicates that JAK/STAT signalling regulates granulysin expression by CD8+ T cells in response to IL-15 and IL-21. Consistent with previous studies conducted with CD4+ T cells [59, 62], HIV-infected CD8+ T cells exhibited reduced phosphorylation of STAT3, STAT5, and granulysin expression in response to IL-15 and IL-21 as compared to mock-infected cells [63].

5. Summary

It is clear that both CD4+ and CD8+CTL mediate direct killing of a wide range of bacterial, parasitic, and fungal pathogens. Studies demonstrate several key features of the microbicidal CTL response. First, with rare exceptions, killing is contact-dependent. Several studies reported a correlation between the frequency [20, 21] or intensity [22] of binding and killing. Moreover, microscopy [37, 40, 41] revealed direct CTL-microbe interactions. Finally, T cells separated from C. neoformans by a porous membrane were unable to mediate killing [43]. Contact may induce release of cytotoxic products by the CTL or provide a microenvironment or concentration at which the cytotoxic product can be efficacious. The latter may explain why supernatants from activated T cells were often unable to mediate killing [20, 34, 40, 41]. Second, killing is mediated primarily through the granule-exocytosis pathway. In many experimental systems, pretreatment of CTL with strontium (which depletes granule contents) was found to abrogate killing [13, 17, 44, 59]. Furthermore, granulysin, a granule constituent [4], has been implicated in the killing of several microbes [13, 15–17, 33, 44, 59]. Third, killing (at least of extracellular microbes) is neither antigen-specific nor MHC-dependent. Nonspecific stimulation with T cell growth factors [34, 35, 39, 40, 44, 59] or mitogenic lectins [20, 21] was often sufficient to prime the effector cells for killing.

The effector mechanisms at work during microbial killing by CTL are gradually being unravelled. While granulysin appears to be highly involved in killing, the role of perforin and other effector molecules is not as clear. In the case of extracellular pathogens, perforin has not been found to play a role in killing [54, 59], although it plays a role in direct killing by NK cells [51, 64, 65]. By contrast, killing of intracellular microbes requires perforin [13, 27], although some investigations have suggested a perforin-independent mechanism [15]. To be sure, this topic demands the attention of future studies.

Much less is known of the signalling pathways. JAK/STAT and PI3K signalling have been found to be essential in CTL killing of C. neoformans [62]. Defective JAK/STAT and PI3K signalling in CTL from HIV-infected patients [62, 63] may explain why these patients experience such a high incidence of severe cryptococcal infection.

During the process of evolution, CTL have developed the ability to specifically recognize altered self through complex TCR-MHC interactions. As a consequence, they have become the epitome of specific cell-mediated immunity. It is fascinating to now discover that during this process, CTL have, at the same time, preserved one of the most rudimentary immune functions of all, namely, the ability to directly recognize a microbe, bind, and without the help of antigen presenting cells or other effector cells kill the invading pathogen with competence and precision.

References

- 1.Bangham CRM. CTL quality and the control of human retroviral infections. European Journal of Immunology. 2009;39(7):1700–1712. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boon T, Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P. Human T cell responses against melanoma. Annual Review of Immunology. 2006;24:175–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cote I, Rogers NJ, Lechler RI. Allorecognition. Transfusion Clinique et Biologique. 2001;8(3):318–323. doi: 10.1016/s1246-7820(01)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ernst WA, Thoma-Uszynski S, Teitelbaum R, et al. Granulysin, a T cell product, kills bacteria by altering membrane permeability. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(12):7102–7108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada S, Li Q, Whitin JC, Clayberger C, Krensky AM. Intracellular mediators of granulysin-induced cell death. Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(5):2556–2562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gamen S, Hanson DA, Kaspar A, Naval J, Krensky AM, Anel A. Granulysin-induced apoptosis. I. Involvement of at least two distinct pathways. Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(4):1758–1764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keefe D, Shi L, Feske S, et al. Perforin triggers a plasma membrane-repair response that facilitates CTL induction of apoptosis. Immunity. 2005;23(3):249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podack ER. How to induce involuntary suicide: the need for dipeptidyl peptidase I. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(15):8312–8314. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi L, Keefe D, Durand E, Feng H, Zhang D, Lieberman J. Granzyme B binds to target cells mostly by charge and must be added at the same time as perforin to trigger apoptosis. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(9):5456–5461. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markham RB, Goellner J, Pier GB. In vitro T cell-mediated killing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. I. Evidence that a lymphokine mediates killing. Journal of Immunology. 1984;133(2):962–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva CL, Lowrie DB. Identification and characterization of murine cytotoxic T cells that kill Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(6):3269–3274. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3269-3274.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Canaday DH, Wilkinson RJ, Li Q, Harding CV, Silver RF, Boom WH. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells kill intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a perforin and Fas/Fas ligand-independent mechanism. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(5):2734–2742. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenger S, Hanson DA, Teitelbaum R, et al. An antimicrobial activity of cytolytic T cells mediated by granulysin. Science. 1998;282(5386):121–125. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodworth JS, Wu Y, Behar SM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD8+ T cells require perforin to kill target cells and provide protection in vivo. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(12):8595–8603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walch M, Eppler E, Dumrese C, Barman H, Groscurth P, Ziegler U. Uptake of granulysin via lipid rafts leads to lysis of intracellular Listeria innocua. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(7):4220–4227. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walch M, Latinovic-Golic S, Velic A, et al. Perforin enhances the granulysin-induced lysis of Listeria innocua in human dendritic cells. BMC Immunology. 2007;8, article 14 doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochoa M-T, Stenger S, Sieling PA, et al. T-cell release of granulysin contributes to host defense in leprosy. Nature Medicine. 2001;7(2):174–179. doi: 10.1038/84620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stenger S, Mazzaccaro RJ, Uyemura K, et al. Differential effects of cytolytic T cell subsets on intracellular infection. Science. 1997;276(5319):1684–1687. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewinsohn DM, Bement TT, Xu J, et al. Human purified protein derivative-specific CD4+ T cells use both CD95- dependent and CD95-independent cytolytic mechanisms. Journal of Immunology. 1998;160(5):2374–2379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellner JJ, Olds GR, Lee CW, Kleinhenz ME, Edmonds KL. Destruction of the multicellular parasite Schistosoma mansoni by T lymphocytes. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1982;70(2):369–378. doi: 10.1172/JCI110626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salata RA, Cox JG, Ravdin JI. The interaction of human T-lymphocytes and Entamoeba histolytica: killing of virulent amoebae by lectin-dependent lymphocytes. Parasite Immunology. 1987;9(2):249–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1987.tb00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vohra H, Kaur U, Sharma AK, Bhalla V, Bhasin D. Effective human defense against E. histolytica: high amoebicidal activity of lymphocytes and monocytes in amoebic liver abscess patients until 3 months follow-up. Parasitology International. 2003;52(3):193–202. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(03)00025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denis M, Chadee K. Murine T-cell clones against Entamoeba histolytica: in vivo and in vitro characterization. Immunology. 1989;66(1):76–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan IA, Smith KA, Kasper LH. Induction of antigen-specific parasiticidal cytotoxic T cell splenocytes by a major membrane protein (P30) of Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Immunology. 1988;141(10):3600–3605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan IA, Smith KA, Kasper LH. Induction of antigen-specific human cytotoxic T cells by Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1990;85(6):1879–1886. doi: 10.1172/JCI114649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakim FT, Gazzinelli RT, Denkers E, Hieny S, Shearer GM, Sher A. CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated against Toxoplasma gondii are cytotoxic for parasite-infected or antigen-pulsed host cells. Journal of Immunology. 1991;147(7):2310–2316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakano Y, Hisaeda H, Sakai T, et al. Granule-dependent killing of Toxoplasma gondii by CD8+ T cells. Immunology. 2001;104(3):289–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denkers EY, Yap G, Scharton-Kersten T, et al. Perforin-mediated cytolysis plays a limited role in host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Journal of Immunology. 1997;159(4):1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang X, Kang H, Kikuchi T, Suzuki Y. Gamma interferon production, but not perforin-mediated cytolytic activity, of T cells is required for prevention of toxoplasmic encephalitis in BALB/c mice genetically resistant to the disease. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(8):4432–4438. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4432-4438.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita K, Yui K, Ueda M, Yano A. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated lysis of Toxoplasma gondii-infected target cells does not lead to death of intracellular parasites. Infection and Immunity. 1998;66(10):4651–4655. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4651-4655.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elloso MM, van der Heyde HC, vande Waa JA, Manning DD, Weidanz WP. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum in vitro by human γδ T cells. Journal of Immunology. 1994;153(3):1187–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Troye-Blomberg M, Worku S, Tangteerawatana P, et al. Human γδT cells that inhibit the in vitro growth of the asexual blood stages of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite express cytolytic and proinflammatory molecules. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 1999;50(6):642–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farouk SE, Mincheva-Nilsson L, Krensky AM, Dieli F, Troye-Blomberg M. γ δ T cell inhibit in vitro growth of the asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum by a granule exocytosis-dependent cytotoxic pathway that requires granulysin. European Journal of Immunology. 2004;34(8):2248–2256. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beno DWA, Mathews HL. Growth inhibition of Candida albicans by interleukin-2-activated splenocytes. Infection and Immunity. 1992;60(3):853–863. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.853-863.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beno DWA, Stover AG, Mathews HL. Growth inhibition of Candida albicans hyphae by CD8+ lymphocytes. Journal of Immunology. 1995;154(10):5273–5281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fung PYS, Murphy JW. In vitro interactions of immune lymphocytes and Cryptococcus neoformans. Infection and Immunity. 1982;36(3):1128–1138. doi: 10.1128/iai.36.3.1128-1138.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy JW, Hidore MR, Wong SC. Direct interactions of human lymphocytes with the yeast-like organism, Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;91(4):1553–1566. doi: 10.1172/JCI116361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levitz SM, Farrell TP, Maziarz RT. Killing of Cryptococcus neoformans by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated in culture. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1991;163(5):1108–1113. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.5.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levitz SM. Activation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by interleukin-2 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor to inhibit Cryptococcus neoformans. Infection and Immunity. 1991;59(10):3393–3397. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3393-3397.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levitz SM, Dupont MP. Phenotypic and functional characterization of human lymphocytes activated by interleukin-2 to directly inhibit growth of Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;91(4):1490–1498. doi: 10.1172/JCI116354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levitz SM, Dupont MP, Smail EH. Direct activity of human T lymphocytes and natural killer cells against Cryptococcus neoformans. Infection and Immunity. 1994;62(1):194–202. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.194-202.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hale LP, Haynes BF. Bromelain treatment of human T cells removes CD44, CD45RA, E2/MIC2, CD6, CD7, CD8, and Leu 8/LAM1 surface molecules and markedly enhances CD2-mediated T cell activation. Journal of Immunology. 1992;149(12):3809–3816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muth SM, Murphy JW. Direct anticryptococcal activity of lymphocytes from Cryptococcus neoformans-immunized mice. Infection and Immunity. 1995;63(5):1637–1644. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1637-1644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ma LL, Spurrell JCL, Wang JF, et al. CD8 T cell-mediated killing of Cryptococcus neoformans requires granulysin and is dependent on CD4 T cells and IL-15. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(10):5787–5795. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Levitz SM, North EA, Dupont MP, Harrison TS. Mechanisms of inhibition of Cryptococcus neoformans by human lymphocytes. Infection and Immunity. 1995;63(9):3550–3554. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3550-3554.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCormick ML, Roeder TL, Railsback MA, Britigan BE. Eosinophil peroxidase-dependent hydroxyl radical generation by human eosinophils. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(45):27914–27919. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcia-Penarrubia P, Bankhurst AD, Koster FT. Prostaglandins from human T suppressor/cytotoxic cells modulate natural killer antibacterial activity. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1989;170(2):601–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linnemeyer PA, Pollack SB. Prostaglandin E2-induced changes in the phenotype, morphology, and lytic activity of IL-2-activated natural killer cells. Journal of Immunology. 1993;150(9):3747–3754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kopp E, Ghosh S. Inhibition of NF-κB by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science. 1994;265(5174):956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.8052854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mody CH, Spurrell JCL, Wood CJ. Interleukin-15 induces antimicrobial activity after release by Cryptococcus neoformans-stimulated monocytes. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1998;178(3):803–814. doi: 10.1086/515381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ma LL, Wang CLC, Neely GG, Epelman S, Krensky AM, Mody CH. NK cells use perforin rather than granulysin for anticryptococcal activity. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(5):3357–3365. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mody CH, Wood CJ, Syme RM, Spurrell JCL. The cell wall and membrane of Cryptococcus neoformans possess a mitogen for human T lymphocytes. Infection and Immunity. 1999;67(2):936–941. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.936-941.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mody CH, Sims KL, Wood CJ, Syme RM, Spurrell JCL, Sexton MM. Proteins in the cell wall and membrane of Cryptococcus neoformans stimulate lymphocytes from both adults and fetal cord blood to proliferate. Infection and Immunity. 1996;64(11):4811–4819. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4811-4819.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mody CH, Lipscomb MF, Street NE, Toews GB. Depletion of CD4+ (L3T4+) lymphocytes in vivo impairs murine host defense to Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Immunology. 1990;144(4):1472–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Syme RM, Wood CJ, Wong H, Mody CH. Both CD4+ and CD8+ human lymphocytes are activated and proliferate in response to Cryptococcus neoformans. Immunology. 1997;92(2):194–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huffnagle GB, Yates JL, Lipscomb MF. Immunity to a pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection requires both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1991;173(4):793–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mody CH, Chen G-H, Jackson C, Curtis JL, Toews GB. Depletion of murine CD8+ T cells in vivo decreases pulmonary clearance of a moderately virulent strain of Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine. 1993;121(6):765–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mody CH, Paine R, III, Jackson C, Chen G-H, Toews GB. CD8 cells play a critical role in delayed type hypersensitivity to intact Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Immunology. 1994;152(8):3970–3979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng CF, Ma LL, Jones GJ, et al. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells use granulysin to kill Cryptococcus neoformans, and activation of this pathway is defective in HIV patients. Blood. 2007;109(5):2049–2057. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coker RJ. Cryptococcal infection in AIDS. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 1992;3(3):168–172. doi: 10.1177/095646249200300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dismukes WE. Cryptococcal meningitis in patients with AIDS. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1988;157(4):624–628. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng CF, Jones GJ, Shi M, et al. Late expression of granulysin by microbicidal CD4+ T cells requires PI3K- and STAT5-dependent expression of IL-2Rβ that is defective in HIV-infected patients. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(11):7221–7229. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hogg AE, Bowick GC, Herzog NK, Cloyd MW, Endsley JJ. Induction of granulysin in CD8+ T cells by IL-21 and IL-15 is suppressed by human immunodeficiency virus-1. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2009;86(5):1191–1203. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0409222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wiseman JCD, Ma LL, Marr KJ, Jones GJ, Mody CH. Perforin-dependent cryptococcal microbicidal activity in NK cells requires PI3K-dependent ERK1/2 signaling. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(10):6456–6464. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marr KJ, Jones GJ, Zheng C, et al. Cryptococcus neoformans directly stimulates perforin production and rearms NK cells for enhanced anticryptococcal microbicidal activity. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77(6):2436–2446. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01232-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]