Abstract

Monocytes in SLE have been described as having aberrant behavior in a number of assays. We examined gene expression and used a genome-wide approach to study the posttranslational histone mark, H4 acetylation, to examine epigenetic changes in SLE monocytes. We compared SLE monocyte gene expression and H4 acetylation with three types of cytokine-treated monocytes to understand which cytokine effects predominated in SLE monocytes. We found that γ-interferon and α-interferon both replicated a broad range of the gene expression changes seen in SLE monocytes. H4 acetylation in SLE monocytes was overall higher than in controls and there was less correlation of H4ac with cytokine-treated cells than when gene expression was compared. A set of chemokine genes had downregulated expression and H4ac. Therefore, there are significant clusters of aberrantly expressed genes in SLE which are strongly associated with altered H4ac, suggesting that these cells have experienced durable changes to their epigenome.

1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has long been characterized as a disease associated with the overexpression of proinflammatory cytokines. The early studies focused on proinflammatory genes and identified increased serum levels of TNFα, IL-6, γIFN, and IL-10 [1–6]. When cells have been examined directly, either by flow cytometry or culture techniques, γIFN, IL-10, IL-17, and IL-6 have been found to be increased in SLE patients [7–12]. In contrast, studies have generally supported an underexpression of IL-12, which is classically considered a proinflammatory cytokine [13, 14]. More recently, studies have identified a signature of type I interferons in whole blood using gene expression arrays [15–19]. This has generated a sea change in the etiologic modeling of the disease and has led to a clinical trial using a neutralizing antibody [20].

Other studies have sought to identify altered expression of chemokines in SLE and these studies have demonstrated increased RANTES, and MCP-1 [21, 22]. Indeed, urine chemokine detection shows promise as an early biomarker of nephritis [23, 24]. Chemokines are often secondary regulators of cell migration, induced by cues from other cells.

This study defined gene expression alterations in monocytes from patients with SLE and correlated those changes with cytokine-induced gene expression changes. We further evaluated H4 acetylation (H4ac) changes, as H4ac is an epigenetic mark of transcriptional potential [25, 26]. Monocytes were selected for study because monocytes and their tissue counterpart, the macrophage, play an extremely important role in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Macrophage infiltration into end organs is thought to be critical to the disease process and renal infiltration of macrophages is specifically associated with a poor prognosis [27]. Monocyte infiltration into glomeruli is driven by fractalkine and both fractalkine levels and monocyte numbers in glomeruli correlate with BUN, proteinuria, and GFR [28]. Additionally, increased macrophage migration inhibitory factor levels correlate with disease activity in lupus patients [29]. Additional well-characterized roles for monocytes in SLE include the clearance of apoptotic cells, participation in atheroma formation, and the elaboration of inflammatory cytokines [30–37].

Monocytes have long been recognized as exhibiting aberrant behavior in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [38–42]. The behavior has been variously ascribed to the presence of cytokines, the presence of immune complexes, or inherited polymorphisms, which collectively alter the cells' behavior. The literature on monocytes in SLE is consistent in demonstrating that the monocytes have compromised viability [36, 43] have an altered capacity to develop into dendritic cells (DC) [37, 44, 45] and have compromised uptake of apoptotic debris [46–49]. STAT 1 is phosphorylated in monocytes of patients with SLE and cells have upregulated MHC class I [15, 50], consistent with a monocyte response to type I interferons in SLE [16, 17, 19, 51–53].

Patients with SLE have mildly altered monocytes as defined by cell surface markers [54, 55], however, cytokine expression is clearly aberrant [56, 57]. SLE monocytes are generally reported to overproduce IL-1RA [58], IL-6 [59, 60], and TNFα in vitro [55, 61], while IL-12 production in both humans and mice is diminished [62–64]. To better define disease effects on SLE monocytes, we examined gene expression changes in purified SLE monocytes and compared those to gene expression changes in control monocytes treated with different cytokines. To determine whether any of the gene expression changes could be mediated by altered chromatin, we examined H4ac, as a mark of transcriptional competence [65–67].

2. Methods

2.1. Cells and Reagents

The SLE monocyte gene expression and ChIP-chip data have been previously reported [68]. In both cases, healthy control donors were used to establish the baseline. The samples studied here are five controls and 9 patients. The patients had a very low SLEDAI score (mean score 0.6) and were on no immune suppressive medications at the time other than low dose prednisone. The cytokine-treated monocytes utilized the cells from a single donor for each set of cytokine treatments. The cytokine data were reported initially in a separate study (submitted). The data represent the averages of three different donors. The cells were purified by elutriation and were ≥95% pure by CD14 staining. The cells were treated with 50 ng/ml of IL-4, 50 ng/ml of γIFN (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), or 500 IU/ml of αIFN (PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ) for 18 hours. Flow cytometry for cell surface markers utilized antibodies from BD Pharmingen and were run on a FacsCalibur instrument using appropriate isotype controls.

2.2. Microarray Experiments

The H4ac immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described [69, 70]. Purified DNA from the immunoprecipitation was amplified, cleaved, and labeled using the GeneChip WT double-stranded DNA terminal labeling kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). DNA preparation and hybridization were all performed according to the recommendations for the GeneChip Human Promoter 1.0R array (Affymetrix). The U133A 2.0 platform was used for the expression analyses. cRNA was prepared according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (Affymetrix). The expression experiments included nine SLE patients, five healthy controls, and three samples of each cytokine treatment group. The H4ac experiments included four nonspecific GST controls, six patients, five healthy controls, and three samples of each treatment group. The data processing has been previously described for the coanalysis of expression and H4 acetylation data [68]. Additional information about the data processing and statistical methods is available in the Supplemental Methods.

3. Results

3.1. SLE Monocytes Exhibit Cell Surface Marker Expression Which Cannot Be Attributed to Single Cytokine Effect

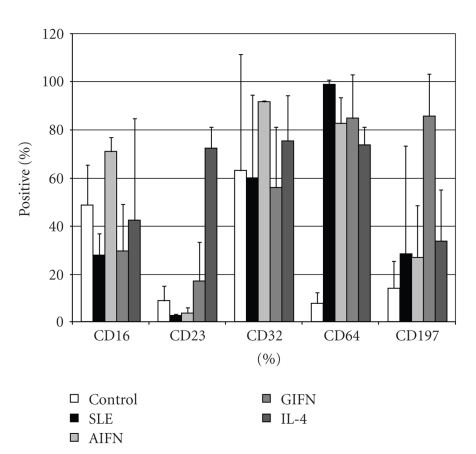

To understand the biology of monocytes from SLE patients, we examined cell surface markers by flow cytometry. We selected a variety of cell surface markers which have been implicated in monocyte function. The cells were gated on physical parameters and CD14. CD16, CD23, CD32, CD64, CD80, CD197, CD206, and CCR2 expression levels were compared between SLE monocytes and control monocytes treated for 18 hours with cytokines. Cell surface markers significantly altered in SLE are shown in Figure 1. γIFN treatment was associated with increased expression of FcγRI (CD64) and CCR7 (CD197). IL-4 treatment was associated with increased expression of FcεRII (CD23) and the macrophage mannose receptor (CD206). The monocytes polarized with αIFN displayed a unique phenotype with increased CD64. CD80 expression was not significantly altered by any treatment. The SLE monocytes expressed cell surface markers are somewhat consistent with the monocytes treated for 18 hours with αIFN, but with a clear difference in CD16 expression. Although in vitro treatment with cytokines does not perfectly replicate chronic in vivo exposure, these data suggested that the phenotype could not be attributed to a single cytokine exposure. We wished to examine whether cytokines could be molding the phenotype of SLE monocytes more globally. With multiple reports of elevated cytokines in addition to type I interferons, we hypothesized that we would find footprints of other cytokine effects within the monocyte population.

Figure 1.

Cell surface markers are altered in SLE and cytokine-treated monocytes. Control monocytes were either mock treated or treated with the indicated cytokines for 18 hours (n = 3). The SLE cells were studied without any intervention (n = 4). In each case, the cells were gated on physical parameters and CD14 expression. The SLE monocytes have statistically significant different expression of CD16 compared to the αIFN-treated cells.

3.2. Overlap between Cytokine-Induced Gene Expression and the SLE Gene Expression

We performed pairwise comparisons of gene expression between SLE monocytes or cytokine-treated monocytes and healthy or untreated control samples. We filtered the genes with P values (t test) <.05 and selected the top 200 genes with the highest or lowest log2 ratio of group means for further study. According to a permutation procedure, the false discovery rates of genes up- and down-regulated in SLE were 3.1% and 6.9%, respectively. To gain insights into the biological alterations as a result of these gene expression changes, we further performed Gene Ontology (GO) analysis through DAVID functional annotation [71]. Table 1 summarizes the top five nonredundant GO terms enriched in SLE or cytokine upregulated genes. The αIFN and γIFN GO terms were similar and partly overlaped the SLE terms, indicating that the SLE monocytes underwent some gene expression changes similar to the effect of interferon treatment. On the other hand, IL-4 terms had little similarity to SLE and interferon terms. This as expected because Il-4 has not been implicated in SLE and was included as a control.

Table 1.

DAVID analysis of SLE gene expression.

| Gene List | GO Term | Count | P value | Fold Enriched |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE UP | Immune system process | 45 | 6.46E-15 | 3.78 |

| Leukocyte activation | 14 | 9.91E-06 | 4.60 | |

| Cytokine receptor activity | 5 | 1.11E-03 | 10.67 | |

| Intracellular signaling cascade | 32 | 3.73E-03 | 1.68 | |

| Defense response | 15 | 2.16E-02 | 1.94 | |

| AIFN UP | Immune system process | 57 | 2.34E-23 | 4.59 |

| Response to virus | 24 | 4.02E-22 | 16.68 | |

| Defense response | 33 | 1.14E-11 | 4.09 | |

| Induction of apoptosis | 10 | 5.04E-03 | 3.08 | |

| Interferon type I production | 3 | 7.90E-03 | 21.38 | |

| GIFN UP | Immune system process | 63 | 2.08E-28 | 5.04 |

| Response to virus | 17 | 5.98E-13 | 11.75 | |

| Defense response | 34 | 2.62E-12 | 4.19 | |

| Regulation of apoptosis | 20 | 4.35E-04 | 2.46 | |

| Lymphocyte proliferation | 7 | 6.09E-04 | 6.61 | |

| IL4 UP | Response to external stimulus | 25 | 2.83E-05 | 2.59 |

| Ribosome biogenesis and assembly | 8 | 3.25E-04 | 6.05 | |

| Cell communication | 72 | 3.46E-04 | 1.43 | |

| Chemokine activity | 6 | 5.24E-04 | 8.85 | |

| Lymphocyte proliferation | 6 | 4.13E-03 | 5.60 | |

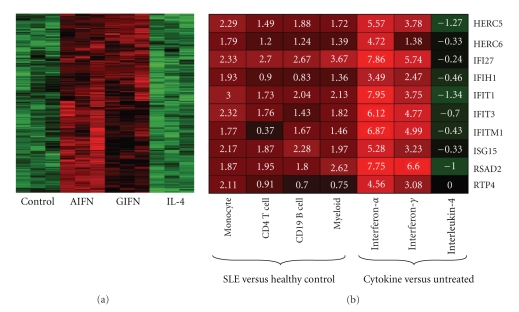

As interferons and IL-4 caused distinctive gene expression changes in monocytes, we carried out a gene clustering analysis on the cytokine data to identify a cluster of 187 genes that responded to both interferons, but not IL-4 (Figure 2(a)). In this cluster, DAVID analysis confirmed the enrichment of genes involved in immune system processes in this cluster (P = 1.4e − 20) and identified seven genes with a known relationship to SLE: FAS, CFB, CCR5, CD80, TRIM21, TAP1, and TAP2. The whole cluster was generally upregulated in SLE (P = 3.4e − 14) with an average increase of 36.3%. Further investigation of this gene cluster could reveal more details about the unique roles of interferons in SLE.

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis of genes upregulated by interferons. (a) A subset of genes identified by unbiased clustering analysis were responsive to both γIFN and αIFN, but not IL-4. On average, the expression of these genes was upregulated by 36.3% in SLE. (b) Ten focus genes identified as being upregulated in four cell types in SLE were examined in the cytokine-treated cells. These genes also exhibited increased expression after γIFN and αIFN treatment but not IL-4 treatment.

We also compared our SLE data with those of an independent study, in which purified CD4 T cells, CD19 B cells, and myeloid cells from patients with SLE were used as sources for gene expression arrays [72]. The raw data from the study were downloaded from the GEO database (GSE10325) and processed with the same procedure used in this study. The top 200 upregulated genes were identified with the same criteria from each cell type and ten of them were included in the lists of all cell types examined, including our SLE monocytes. These ten genes were also highly induced by αIFN with a smaller effect seen in the γIFN-treated cells, but slightly down-regulated by IL-4 (Figure 2(b)). This analysis ensured that although our sample population had very low disease activity, the findings were generalizeable.

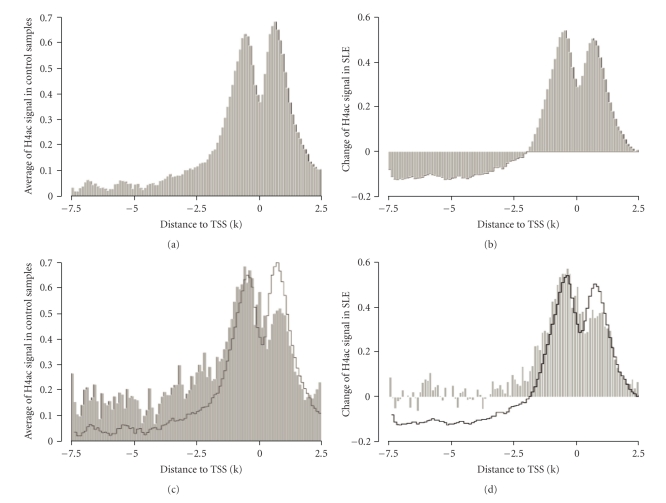

3.3. H4 Acetylation in SLE

We have previously reported that H4ac was altered in SLE monocytes [68, 73]. We therefore reanalyzed the data to understand the role of the different cytokines in the altered H4ac landscape of the cells. The H4ac mark was mapped using tiling arrays and all genes were aligned by their transcription start site (TSS). The H4ac content exhibits a forked peak pattern, centered on the TSS (Figure 3(a)) [66, 74]. When the SLE H4ac signal across the genome was compared to controls, SLE genes overall has a higher signal. Much of the difference between the patients and controls lies around the transcription start site, with relative hypoacetylation distant from the TSS (Figure 3(b)). H4 acetylation marks are typically placed by histone acetyltransferases recruited by transcription factors. We previously reported an increase of H4ac at potential binding sites of transcription factors like IRF1 and the expression change of IRF1-downstream targets [68]. We generalized our analysis in this study. All potential TFBSs in human genome conserved in human/mouse/rat alignment were downloaded from UCSC Genome Browser and mapped to the TSSs. The average H4ac at binding sites around TSSs had a distinctive pattern (Figure 3(c)). TFBSs located in the upstream promoter region had higher H4ac than average while those located immediately downstream of TSS had lower H4ac content. In SLE monocytes, the H4ac change at TFBSs had a similar pattern (Figure 3(d)). These observations suggest that H4ac at TFBSs is part of an expression regulatory network.

Figure 3.

The distribution of H4ac at the promoter. (a) H4ac was distributed around the transcription start site. (b) The SLE monocytes had increased H4ac globally around the transcription start site. (c) The average of H4ac at potential TFBSs (grey area) was different from the general pattern of H4ac around TSS (black line), most notably, it was higher in the promoter region, but lower immediately after the TSSs. (d). In SLE, the average change of H4ac at potential TFBS (grey area) was also different from the general pattern (black line).

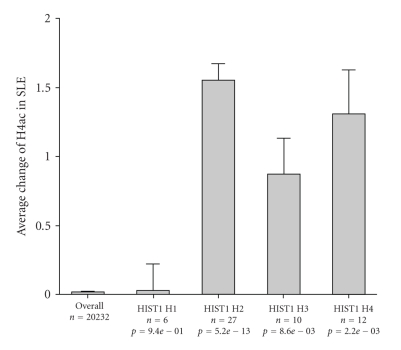

We considered whether increased competence for expression of the histone genes themselves could contribute to this picture. It may be seen that the H4ac at the H2, H3, and H4 gene clusters was generally increased in SLE monocytes (Figure 4). This could contribute to globally increased H4ac in the SLE monocytes but cannot be the complete explanation because the acetyl mark is placed posttranscriptionally. To understand whether histone acetyltransferases might have dysregulated expression as a mechanism to explain the globally increased H4ac, we examined the expression of the human histone acetyltransferases in SLE patients. The expression of these genes was not globally increased although several individual members were upregulated including HAT1 (log2 ratio = 0.79), KAT2B (log2 ratio = 0.77), MYST3 (log2 ratio = 0.74), and MYST4 (log2 ratio = 0.53). We examined whether this effect was replicated in any of the cytokine-treated monocytes. Only KAT2B was upregulated in γIFN and αIFN-treated cells, which is consistent with the observation that H4ac is globally elevated in SLE monocytes but not in cytokine-treated cells.

Figure 4.

H4ac at histone genes. H2, H3, and H4 gene families had increased H4ac in SLE monocytes.

To examine the biological processes anticipated to be altered as a result of the SLE H4ac landscape, we utilized DAVID for the GO analysis of the 200 genes with the highest H4ac due to cytokine treatment or SLE (Table 2). This strategy collapses the H4ac data into functional categories. In this analysis, the finding of increased H4ac in SLE was seen in processes related to basic cell biology, including basic metabolic processes. Besides the GO terms listed in Table 2, DAVID also found increased H4ac of the Kruppel-associated box (KRAB) family of transcriptional repressors in SLE monocytes (P = 8.1e − 9). These typically function in hematopoietic cell differentiation [75]. When DAVID was used to examine the inferred biological processes altered in SLE compared to those in γIFN and αIFN-treated cells, there was little overlap, suggesting that the SLE monocytes are more fundamentally altered than can be explained by brief cytokine exposure.

Table 2.

DAVID analysis of H4ac gene sets.

| Gene List | GO Term | Count | P value | Fold Enriched |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE UP | Membrane-bound organelle | 114 | 2.39E-06 | 1.35 |

| Nucleic acid binding | 62 | 2.07E-05 | 1.65 | |

| Metabolic process | 122 | 7.37E-04 | 1.19 | |

| Chromatin assembly | 6 | 4.56E-03 | 5.44 | |

| Ribosome biogenesis and assembly | 6 | 9.61E-03 | 4.57 | |

| AIFN UP | Response to virus | 13 | 1.10E-08 | 9.16 |

| Immune system process | 35 | 3.27E-08 | 2.84 | |

| Structural constituent of ribosome | 7 | 6.30E-03 | 4.18 | |

| Defense response | 17 | 9.08E-03 | 2.03 | |

| Interferon type I production | 3 | 1.20E-02 | 17.17 | |

| GIFN UP | Immune system process | 40 | 9.04E-11 | 3.17 |

| Late endosome | 7 | 6.58E-05 | 9.70 | |

| Defense response | 22 | 1.13E-04 | 2.56 | |

| Response to virus | 8 | 5.58E-04 | 5.50 | |

| Adaptive immune response | 6 | 5.73E-03 | 5.16 | |

| IL4 UP | Antigen processing and presentation | 7 | 2.08E-04 | 7.96 |

| Immune system process | 23 | 4.08E-03 | 1.90 | |

| Regulation of protein metabolic process | 11 | 8.14E-03 | 2.66 | |

| Structural molecule activity | 17 | 2.69E-02 | 1.79 | |

| Golgi vesicle transport | 6 | 2.90E-02 | 3.45 | |

3.4. Coanalysis of H4ac and Gene Expression

To understand whether cytokines could alter the chromatin landscape of monocytes and to correlate the H4ac changes seen in SLE monocytes with those induced by cytokines, we examined the agreement between H4ac and expression data of 9553 unique genes measured by both array platforms and the results are summarized in Table 3. The first part of Table 3 (with GST controls) compares the absolute measurements of expression and H4ac in six sample groups, after the GST control was used to remove nonspecific array signals from the H4ac data. The global correlation between expression and H4ac was consistently around 0.4 in all groups. We picked the 200 top and bottom genes from each group based on their expression and H4ac level and checked the overlap between the two lists. The numbers of overlapped genes and the odds ratios calculated by Fisher's test are also listed in Table 3. The genes with high expression had relatively less overlap with genes with high H4ac, compared to the down-regulated pair, suggesting that high H4ac is not sufficient to ensure high gene expression. The overlapping at the lower end was much more prominent. The second part of Table 3 (the last four lines) presents the same results based on the relative change of expression and H4ac within each experimental group. The relative change in expression was calculated from the reference for each group, given in the second column. The global expression-H4ac correlation was notably lower as most genes were not affected by SLE or cytokine treatment. The overlap between genes with increased expression and H4ac was more significant, especially genes responding to interferons.

Table 3.

Concordance between gene expression and H4ac content.

| Group 1 | Group 0 | Correlation (r) | Top 200 overlap* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num_gene (up) | Odds Ratio (up) | Num_gene (down) | Odds Ratio (down) | |||

| Healthy | GST | 0.39 | 8 | 1.99 | 17 | 4.65 |

| SLE | GST | 0.44 | 10 | 2.54 | 24 | 7.11 |

| NoRx | GST | 0.44 | 7 | 1.72 | 29 | 9.10 |

| AIFN | GST | 0.45 | 10 | 2.54 | 26 | 7.88 |

| GIFN | GST | 0.44 | 6 | 1.46 | 26 | 7.88 |

| IL4 | GST | 0.43 | 9 | 2.26 | 31 | 9.96 |

| SLE | Healthy | 0.21 | 13 | 3.41 | 22 | 6.37 |

| AIFN | NoRx | 0.23 | 49 | 19.76 | 10 | 2.54 |

| GIFN | NoRx | 0.19 | 34 | 11.32 | 19 | 5.32 |

| IL4 | NoRx | 0.14 | 18 | 4.98 | 23 | 6.73 |

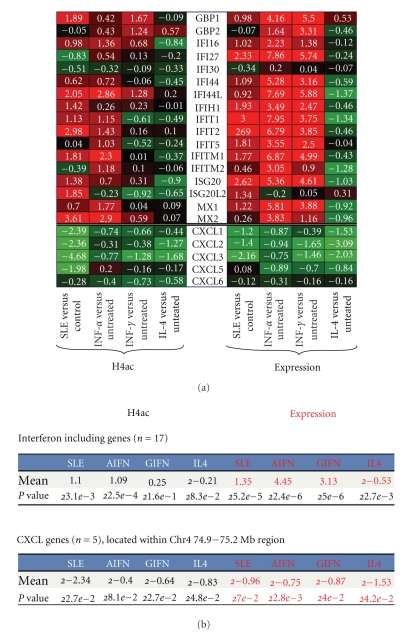

We identified two clusters of genes with an unusually high correlation of H4ac and gene expression. A cluster of chemokine genes that map to chromosome 4 had markedly repressed expression in SLE and this was associated with a markedly diminished H4ac. Interestingly, these genes were repressed by all three cytokines. These chemokines regulate neutrophil function, monocyte migration, and angiogenesis [76–80]. The interferon-responsive genes had a strong association of H4ac and gene expression in SLE and this was replicated in part by exposure to both types of interferon (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

SLE is known to be associated with increased expression of interferon-inducible genes and these genes have a strong association of H4ac and gene expression. We noted another cluster had a similarly strong association of H4ac and gene expression. The chemokine cluster was identified as having significantly decreased expression and H4ac in SLE monocytes. (a) The heatmap demonstrating the association of gene expression and H4ac. (b) The statistical relationship between the groups.

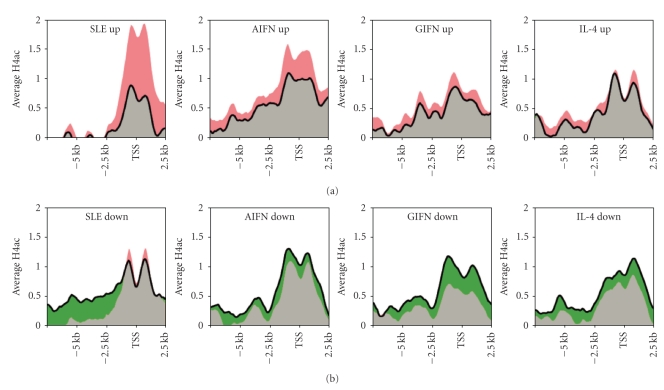

To more directly link gene expression change to histone modification, we summarized the average H4ac change of the genes identified above as differentially expressed in SLE or after cytokine treatment (Figure 6). On average, genes with upregulated expression in SLE had a dramatic increase in H4ac. However, as the H4ac was generally increased in SLE, the H4ac around the TSS of down-regulated genes was also increased slightly although H4ac was notably decreased in upstream promoter region. Genes up- or down-regulated by cytokines had a more consistent H4ac change. An interesting observation in Figure 6 is that the genes upregulated in SLE seemed to have lower baseline H4ac by average, suggesting that those genes may be repressed in healthy monocytes.

Figure 6.

The change in gene expression in SLE or cytokine-treated samples was matched by H4ac changes in the same samples. (a) Upregulated genes seen in SLE or after cytokine treatment were examined for H4ac content. The top 200 genes with the highest expression change caused by SLE or cytokines, as was identified by previous analysis were included. (b) Down-regulated genes seen in SLE or after cytokine treatment were examined for H4ac content. The 200 genes most down-regulated were examined. The black contour indicates the average H4ac in control samples and the colored regions correspond to the amount of H4ac increase (red) or decrease (green) in SLE or cytokine-treated samples.

4. Discussion

The concept of an altered epigenome in SLE is an attractive model because the epigenome could contribute to the disease perpetuation by molding pathologic gene expression. One of the best-characterized epigenetic changes in SLE is the hypomethylation of DNA in T cells [81]. This finding is consistent in murine models [82] and more recent studies have linked demethylation of DNA with the drug-induced lupus seen with procainamide and hydralazine [83, 84]. Induced demethylation alters the expression of a number of genes, which could contribute to the pathophysiology of lupus [85–87].

Several groups have utilized histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in lupus models in an effort to reregulate aberrant gene expression. Trichostatin (TSA) or the chemically related compound, SAHA, was used to treat MRL/lpr mice [88]. These agents increase H4ac through inhibition of histone deacetylases. This murine model of SLE is characterized by increased expression of γIFN, IL-12, IL-6, and IL-10. In vitro and in vivo treatment with an HDAC inhibitor decreased RNA and protein levels for all four overexpressed cytokines. In addition, administration of TSA led to less active renal disease [88]. HDAC inhibitors are immunosuppressive in vivo and therefore to better understand the epigenome in SLE, we directly characterized the epigenome in SLE [89]. Our previous study of H4ac in SLE monocytes found that many of the changes could be due to overexpression of the transcription factor IRF1 [68]. In the current study, we directly examined whether gene expression and H4ac alterations in SLE monocytes could be attributed to cytokine exposure. The SLE literature is replete with studies demonstrating overexpression of a broad range of cytokines, not just type I interferons. The finding of specific features attributable to cytokine exposure would have a significant impact on the conceptualization of new treatments. A caveat of the system we used is that the cytokine-treated cells used as comparators represent an artificial in vitro system that clearly cannot replicate the complex chronic exposures seen in a disease state. Nevertheless, this study demonstrates that such attribution is possible and can be used to examine both the epigenetic changes in SLE as well as gene expression.

An underlying hypothesis is that monocytes “polarized” by the disease can contribute to ongoing inflammation or may mold the end organ involvement. Supporting this is the finding that in murine models of SLE as well as human disease, macrophage infiltration into the kidney correlates with the severity of the renal disease and the prognosis [27]. Aberrant regulation of chemokines, as demonstrated in this study, would be predicted to alter migration and potentially alter disease manifestations. If some of these alterations can be traced to a specific signaling pathway, a novel therapeutic target would be identified.

This study examined a specific cell type in which dysfunction has been well characterized in humans. Murine lupus models also exhibit aberrant monocyte function, suggesting it is a consistent feature of the disease. Both monocyte uptake of apoptotic cells and DNA are abnormal [90–92]. Indeed, monocyte apoptosis itself may contribute to the disease process [93]. Many SLE murine models exhibit a monocytosis, and the monocytes may amplify the inflammatory process [94–97]. In MRL/lpr mice, macrophage expression of γIFN is required for the expression of the renal disease [98]. Additional studies demonstrated that engagement of TLR7 aggravated renal disease, characterized by infiltration of monocytes [98, 99]. In fact, inhibition of macrophage recruitment into the kidney, markedly attenuated the phenotype in MRL/lpr mice [100]. In the NZB × NZW system, signaling in myeloid cells through FcγR is critical to the inflammatory process and macrophages are critical for anti-dsDNA production [101, 102]. The SLE3 locus in the NZM2410 strain, derived from NZB × NZW, appears to confer susceptibility to lupus by driving increased macrophage costimulatory activity [103, 104]. A potential role for monocytes in these models is via the inflammatory cytokines produced by monocytes and macrophages as was demonstrated in the MRL/lpr system [98, 99].

This study provides a potential explanation for the persistent monocyte dysfunction seen in both human SLE patients and in murine models. The effect of cytokines can induce changes in the epigenome and persistence of these changes could lead to durably altered gene expression which in turn could underlie many of the aberrant functions. There were many other effects that did not trace to the three cytokines used in this study. Potential caveats include the short exposure to cytokines in our model system, the effects from other cytokines or stimuli and the potential for the cells to have an aberrant differentiation pathway in the presence of active SLE.

This study hypothesized that many of the changes in both gene expression and H4ac would be attributable to type I interferons since their effects have been well characterized in SLE [16, 51, 105]. Indeed, many effects in gene expression and H4ac could be traced to αIFN, although γIFN led to similar changes. There are several lines of evidence suggesting that monocytes have been molded by a complex set of exposures. Our cytokine attribution found that the interferon-responsive genes cluster was upregulated 36.3% in SLE monocytes, thus leaving a significant gene set unexplained by interferon exposure. The association was even less robust for H4ac. The finding that H4 acetylation was globally increased and this increase appeared to map to TFBSs suggests a globally altered epigenome with a complex etiology. Therefore, monocytes are significantly impacted by both αIFN and γIFN exposure, however, our data suggest that additional cytokines and other exposures contribute to the aberrant monocyte behavior observed in SLE patients.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by NIH R01 AI 0511323 and R01 ES 017627. The authors would like to thank Dr. Micheal Petzl.

References

- 1.Robak E, Sysa-Jedrzejewska A, Dziankowska B, Torzecka D, Chojnowski K, Robak T. Association of interferon γ, tumor necrosis factor α and interleukin 6 serum levels with systemic lupus erythematosus activity. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 1998;46(6):375–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waszczykowska E, Robak E, Wozniacka A, Narbutt J, Torzecka JD, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A. Estimation of SLE activity based on the serum level of chosen cytokines and superoxide radical generation. Mediators of Inflammation. 1999;8(2):93–100. doi: 10.1080/09629359990586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davas EM, Tsirogianni A, Kappou I, Karamitsos D, Economidou I, Dantis PC. Serum IL-6, TNFα, p55 srTNFα, p75 srTNFα, srIL-2α levels and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Rheumatology. 1999;18(1):17–22. doi: 10.1007/s100670050045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linker-Israeli M, Deans RJ, Wallace DJ, Prehn J, Ozeri-Chen T, Klinenberg JR. Elevated levels of endogenous IL-6 in systemic lupus erythematosus. A putative role in pathogenesis. Journal of Immunology. 1991;147(1):117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong CK, Lit LCW, Tam LS, Li EKM, Wong PTY, Lam CWK. Hyperproduction of IL-23 and IL-17 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: implications for Th17-mediated inflammation in auto-immunity. Clinical Immunology. 2008;127(3):385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong CK, Ho CY, Li EK, Lam CWK. Elevation of proinflammatory cytokine (IL-18, IL-17, IL-12) and Th2 cytokine (IL-4) concentrations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2000;9(8):589–593. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akahoshi M, Nakashima H, Tanaka Y, et al. Th1/Th2 balance of peripheral T helper cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1999;42(8):1644–1648. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1644::AID-ANR12>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagiwara E, Gourley MF, Lee S, Klinman DM. Disease severity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with an increased ratio of interleukin-10:interferon-γ-secreting cells in the peripheral blood. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1996;39(3):379–385. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Csiszár A, Nagy GY, Gergely P, Pozsonyi T, Pócsik É. Increased interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-10 and decreased IL-4 mRNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2000;122(3):464–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amel-Kashipaz MR, Huggins ML, Lanyon P, Robins A, Todd I, Powell RJ. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the balance between type 1 and type 2 cytokine-producing CD8− and CD8+ T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2001;17(2):155–163. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2001.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mongan AE, Ramdahin S, Warrington RJ. Interleukin-10 response abnormalities in systemic lupus erythematosus. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 1997;46(4):406–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crispín JC, Oukka M, Bayliss G, et al. Expanded double negative T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus produce IL-17 and infiltrate the kidneys. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(12):8761–8766. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horwitz DA, Gray JD, Behrendsen SC, et al. Decreased production of interleukin-12 and other Th1-type cytokines in patients with recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1998;41(5):838–844. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<838::AID-ART10>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min D-J, Cho M-L, Cho C-S, et al. Decreased production of interleukin-12 and interferon-γ is associated with renal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2001;30(3):159–163. doi: 10.1080/030097401300162932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dall’Era MC, Cardarelli PM, Preston BT, Witte A, Davis JC., Jr. Type I interferon correlates with serological and clinical manifestations of SLE. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2005;64(12):1692–1697. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett L, Palucka AK, Arce E, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197(6):711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G, Truedsson L, et al. Activation of type I interferon system in systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with disease activity but not with antiretroviral antibodies. Lupus. 2000;9(9):664–671. doi: 10.1191/096120300674499064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banchereau J, Pascual V. Type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune diseases. Immunity. 2006;25(3):383–392. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(5):2610–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yao Y, Richman L, Higgs BW, et al. Neutralization of interferon-α/β-inducible genes and downstream effect in a phase I trial of an anti-interferon-α monoclonal antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(6):1785–1796. doi: 10.1002/art.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rus V, Atamas SP, Shustova V, et al. Expression of cytokine- and chemokine-related genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from lupus patients by cDNA array. Clinical Immunology. 2002;102(3):283–290. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaneko H, Ogasawara H, Naito T, et al. Circulating levels of β-chemokines in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Rheumatology. 1999;26(3):568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu T, Xie C, Wang HW, et al. Elevated urinary VCAM-1, P-selectin, soluble TNF receptor-1, and CXC chemokine ligand 16 in multiple murine lupus strains and human lupus nephritis. Journal of Immunology. 2007;179(10):7166–7175. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.7166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferri GM, Gigante A, Ferri F, et al. Urine chemokines: biomarkers of human lupus nephritis? European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2007;11(3):171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schübeler D, MacAlpine DM, Scalzo D, et al. The histone modification pattern of active genes revealed through genome-wide chromatin analysis of a higher eukaryote. Genes and Development. 2004;18(11):1263–1271. doi: 10.1101/gad.1198204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agalioti T, Chen G, Thanos D. Deciphering the transcriptional histone acetylation code for a human gene. Cell. 2002;111(3):381–392. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hill GS, Delahousse M, Nochy D, et al. Predictive power of the second renal biopsy in lupus nephritis: significance of macrophages. Kidney International. 2001;59(1):304–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshimoto S, Nakatani K, Iwano M, et al. Elevated levels of fractalkine expression and accumulation of CD16+ monocytes in glomeruli of active lupus nephritis. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2007;50(1):47–58. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foote A, Briganti EM, Kipen Y, Santos L, Leech M, Morand EF. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31(2):268–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meijer C, Huysen V, Smeenk RTJ, Swaak AJG. Profiles of cytokines (TNFα and IL-6) and acute phase proteins (CRP and α1AG) related to the disease course in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 1993;2(6):359–365. doi: 10.1177/096120339300200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwitz DA, Wang H, Gray JD. Cytokine gene profile in circulating blood mononuclear cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: increased interleukin-2 but not interleukin-4 mRNA. Lupus. 1994;3(5):423–428. doi: 10.1177/096120339400300511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pégorier S, Stengel D, Durand H, Croset M, Ninio E. Oxidized phospholipid: POVPC binds to platelet-activating-factor receptor on human macrophages. Implications in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188(2):433–443. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denny MF, Thacker S, Mehta H, et al. Interferon-α promotes abnormal vasculogenesis in lupus: a potential pathway for premature atherosclerosis. Blood. 2007;110(8):2907–2915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asanuma Y, Oeser A, Shintani AK, et al. Premature coronary-artery atherosclerosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349(25):2407–2415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barath P, Fishbein MC, Cao J, Berenson J, Helfant RH, Forrester JS. Detection and localization of tumor necrosis factor in human atheroma. American Journal of Cardiology. 1990;65(5):297–302. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shoshan Y, Shapira I, Toubi E, Frolkis I, Yaron M, Mevorach D. Accelerated Fas-mediated apoptosis of monocytes and maturing macrophages from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: relevance to in vitro impairment of interaction with iC3b-opsonized apoptotic cells. Journal of Immunology. 2001;167(10):5963–5969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.10.5963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Köller M, Zwölfer B, Steiner G, Smolen JS, Scheinecker C. Phenotypic and functional deficiencies of monocyte-derived dendritic cells in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients. International Immunology. 2004;16(11):1595–1604. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell PJ, Steinberg AD. Studies of peritoneal macrophage function in mice with systemic lupus erythematosus: depressed phagocytosis of opsonized sheep erythrocytes in vitro. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology. 1983;27(3):387–402. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(83)90091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dang-Vu AP, Pisetsky DS, Weinberg JB. Functional alterations of macrophages in autoimmune MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Journal of Immunology. 1987;138(6):1757–1761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brozek CM, Hoffman CL, Savage SM, Searles RP. Systemic lupus erythematosus sera inhibit antigen presentation by macrophages to T cells. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology. 1988;46(2):299–313. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(88)90192-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez-Karpovitch X, Cardiel M, Cardenas R, Piedras J, Alarcon-Segovia D. Circulating colony-forming units of granulocytes and monocytes/macrophages in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1989;77(1):43–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zippel D, Lackovic V, Kociskova D, Rovensky J, Borecky L, Stelzner A. Abnormal macrophages and NK cell cytotoxicity in human systemic lupus erythematosus and the role of interferon and serum factors. Acta Virologica. 1989;33(5):447–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G, Gullstrand B, Truedsson L. Induction of apoptosis in monocytes and lymphocytes by serum from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus—an additional mechanism to increased autoantigen load? Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2004;135(3):535–543. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2003.02386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bayry J, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Delignat S, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin abrogates dendritic cell differentiation induced by interferon-α present in serum from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;48(12):3497–3502. doi: 10.1002/art.11346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Figueroa-Vega N, Galindo-Rodríguez G, Bajaña S, et al. Phenotypic analysis of IL-10-treated, monocyte-derived dendritic cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2006;64(6):668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baumann I, Kolowos W, Voll RE, et al. Impaired uptake of apoptotic cells into tingible body macrophages in germinal centers of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2002;46(1):191–201. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200201)46:1<191::AID-ART10027>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ren Y, Tang J, Mok MY, Chan AWK, Wu A, Lau CS. Increased apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages and impaired macrophage phagocytic clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;48(10):2888–2897. doi: 10.1002/art.11237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bijl M, Reefman E, Horst G, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CGM. Reduced uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages in systemic lupus erythematosus: correlates with decreased serum levels of complement. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2006;65(1):57–63. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.035733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tas SW, Quartier P, Botto M, Fossati-Jimack L. Macrophages from patients with SLE and rheumatoid arthritis have defective adhesion in vitro, while only SLE macrophages have impaired uptake of apoptotic cells. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2006;65(2):216–221. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.037143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuroiwa T, Schlimgen R, Illei GG, Boumpas DT. Monocyte response to Th1 stimulation and effector function toward human mesangial cells are not impaired in patients with lupus nephritis. Clinical Immunology. 2003;106(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(02)00022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, et al. Coordinate overexpression of interferon-α-induced genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2004;50(12):3958–3967. doi: 10.1002/art.20798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hua J, Kirou K, Lee C, Crow MK. Functional assay of type I interferon in systemic lupus erythematosus plasma and association with anti-RNA binding protein autoantibodies. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(6):1906–1916. doi: 10.1002/art.21890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preble OT, Black RJ, Friedman RM. Systemic lupus erythematosus: presence in human serum of an unusual acid-labile leukocyte interferon. Science. 1982;216(4544):429–431. doi: 10.1126/science.6176024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liou L-B. Different monocyte reaction patterns in newly diagnosed, untreated rheumatoid arthritis and lupus patients probably confer disparate C-reactive protein levels. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2003;21(4):437–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steinbach F, Henke F, Krause B, Thiele B, Burmester G-R, Hiepe F. Monocytes from systemic lupus erythematous patients are severely altered in phenotype and lineage flexibility. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2000;59(4):283–288. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.4.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zeuner RA, Klinman DM, Illei G, et al. Response of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from lupus patients to stimulation by CpG oligodeoxynucleotides. Rheumatology. 2003;42(4):563–569. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Katsiari CG, Liossis S-NC, Souliotis VL, Dimopoulos AM, Manoussakis MN, Sfikakis PP. Aberrant expression of the costimulatory molecule CD40 ligand on monocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Immunology. 2002;103(1):54–62. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liou L-B. Serum and in vitro production of IL-1 receptor antagonist correlate with C-reactive protein levels in newly diagnosed, untreated lupus patients. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 2001;19(5):515–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linker-Israeli M, Wallace DJ, Prehn J, et al. Association of IL-6 gene alleles with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and with elevated IL-6 expression. Genes and Immunity. 1999;1(1):45–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chae BS, Shin TY. Immunoregulatory abnormalities of T cells and hyperreactivity of B cells in the in vitro immune response in pristane-induced lupus mice. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2007;30(2):191–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02977694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jones BM, Liu T, Wong RWS. Reduced in vitro production of interferon-gamma, interleukin-4 and interleukin-12 and increased production of interleukin-6, interleukin-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Weak correlations of cytokine production with disease activity. Autoimmunity. 1999;31(2):117–124. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu J, Beller D. Aberrant production of IL-12 by macrophages from several autoimmune-prone mouse strains is characterized by intrinsic and unique patterns of NF-κB expression and binding to the IL-12 p40 promoter. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(1):581–586. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alleva DG, Kaser SB, Beller DI. Intrinsic defects, in macrophage IL-12 production associated with immune dysfunction in the MRL/++ and New Zealand black/white F1 lupus-prone mice and the Leishmania major-susceptible BALB/c strain. Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(12):6878–6884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu TF, Jones BM. Impaired production of IL-12 in systemic lupus erythematosus. I. Excessive production of IL-10 suppresses production of IL-12 by monocytes. Cytokine. 1998;10(2):140–147. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1997.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu H, Zhu S, Zhou B, Xue H, Han J-DJ. Inferring causal relationships among different histone modifications and gene expression. Genome Research. 2008;18(8):1314–1324. doi: 10.1101/gr.073080.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, et al. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell. 2005;120(2):169–181. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roh T-Y, Wei G, Farrell CM, Zhao K. Genome-wide prediction of conserved and nonconserved enhancers by histone acetylation patterns. Genome Research. 2007;17(1):74–81. doi: 10.1101/gr.5767907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Z, Song L, Maurer K, Petri MA, Sullivan KE. Global H4 acetylation analysis by ChIP-chip in systemic lupus erythematosus monocytes. Genes and Immunity. 2009 doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Garrett S, Dietzmann-Maurer K, Song L, Sullivan KE. Polarization of primary human monocytes by IFN-γ induces chromatin changes and recruits RNA pol II to the TNF-α promoter. Journal of Immunology. 2008;180(8):5257–5266. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JY, Kim NA, Sanford A, Sullivan KE. Histone acetylation and chromatin conformation are regulated separately at the TNF-α promoter in monocytes and macrophages. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2003;73(6):862–871. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1202618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dennis G, Jr., Sherman BT, Hosack DA, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biology. 2003;4(5):p. P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hutcheson J, Scatizzi JC, Siddiqui AM, et al. Combined deficiency of proapoptotic regulators bim and fas results in the early onset of systemic autoimmunity. Immunity. 2008;28(2):206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sullivan KE, Suriano A, Dietzmann K, Lin J, Goldman D, Petri MA. The TNFα locus is altered in monocytes from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Immunology. 2007;123(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Clayton AL, Hazzalin CA, Mahadevan LC. Enhanced histone acetylation and transcription: a dynamic perspective. Molecular Cell. 2006;23(3):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bellefroid EJ, Poncelet DA, Lecocq PJ, Revelant O, Martial JA. The evolutionarily conserved Kruppel-associated box domain defines a subfamily of eukaryotic multifingered proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1991;88(9):3608–3612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haghnegahdar H, Du J, Wang D, et al. The tumorigenic and angiogenic effects of MGSA/GRO proteins in melanoma. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2000;67(1):53–62. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pelus LM, Fukuda S. Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization: the CXCR2 ligand GROβ rapidly mobilizes hematopoietic stem cells with enhanced engraftment properties. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34(8):1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Smith DF, Galkina E, Ley K, Huo Y. GRO family chemokines are specialized for monocyte arrest from flow. American Journal of Physiology. 2005;289(5):H1976–H1984. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00153.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang M-S, McNinch J, Basu R, Simonet S. Cloning and characterization of the human neutrophil-activating peptide (ENA-78) gene. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(41):25277–25282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wuyts A, Van Osselaer N, Haelens A, et al. Characterization of synthetic human granulocyte chemotactic protein 2: usage of chemokine receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 and in vivo inflammatory properties. Biochemistry. 1997;36(9):2716–2723. doi: 10.1021/bi961999z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richardson B, Scheinbart L, Strahler J, Gross L, Hanash S, Johnson M. Evidence for impaired T cell DNA methylation in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1990;33(11):1665–1673. doi: 10.1002/art.1780331109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quddus J, Johnson KJ, Gavalchin J, et al. Treating activated CD4+ T cells with either of two distinct DNA methyltransferase inhibitors, 5-azacytidine or procainamide, is sufficient to cause a lupus-like disease in syngeneic mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;92(1):38–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI116576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deng C, Lu Q, Zhang Z, et al. Hydralazine may induce autoimmunity by inhibiting extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway signaling. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2003;48(3):746–756. doi: 10.1002/art.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Scheinbart LS, Johnson MA, Gross LA, Edelstein SR, Richardson BC. Procainamide inhibits DNA methyltransferase in a human T cell line. Journal of Rheumatology. 1991;18(4):530–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kaplan MJ, Lu Q, Wu A, Attwood J, Richardson B. Demethylation of promoter regulatory elements contributes to perforin overexpression in CD4+ lupus T cells. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(6):3652–3661. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;97(12):2866–2871. doi: 10.1172/JCI118743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Richardson BC, Strahler JR, Pivirotto TS, et al. Phenotypic and functional similarities between 5-azacytidine-treated T cells and a T cell subset in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1992;35(6):647–662. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reilly CM, Mishra N, Miller JM, et al. Modulation of renal disease in MRL/lpr mice by suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid. Journal of Immunology. 2004;173(6):4171–4178. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Skov S, Rieneck K, Bovin LF, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: a new class of immunosuppressors targeting a novel signal pathway essential for CD154 expression. Blood. 2003;101(4):1430–1438. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ogawa Y, Yoshinaga T, Yasuda K, Nishikawa M, Takakura Y. The uptake and degradation of DNA is impaired in macrophages and dendritic cells from NZB/W F1 mice. Immunology Letters. 2005;101(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Licht R, Dieker JWC, Jacobs CWM, Tax WJM, Berden JHM. Decreased phagocytosis of apoptotic cells in diseased SLE mice. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2004;22(2):139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Carlucci F, Cortes-Hernandez J, Fossati-Jimack L, et al. Genetic dissection of spontaneous autoimmunity driven by 129-derived chromosome 1 loci when expressed on C57BL/6 mice. Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(4):2352–2360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Denny MF, Chandaroy P, Killen PD, et al. Accelerated macrophage apoptosis induces autoantibody formation and organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(4):2095–2104. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davis TA, Lennon G. Mice with a regenerative wound healing capacity and an SLE autoimmune phenotype contain elevated numbers of circulating and marrow-derived macrophage progenitor cells. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2005;34(1):17–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vieten G, Hadam MR, De Boer H, Olp A, Fricke M, Hartung K. Expanded macrophage precursor populations in BXSB mice: possible reason for the increasing monocytosis in male mice. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology. 1992;65(3):212–218. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(92)90149-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Muller M, Emmendorffer A, Lohmann-Matthes M-L. Expansion and high proliferative potential of the macrophage system throughout life time of lupus-prone NZB/W and MRL lpr/lpr mice. Lack of down-regulation of extramedullar macrophage proliferation in the postnatal period. European Journal of Immunology. 1991;21(9):2211–2217. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Amano H, Amano E, Santiago-Raber M-L, et al. Selective expansion of a monocyte subset expressing the CD11c dendritic cell marker in the Yaa model of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52(9):2790–2798. doi: 10.1002/art.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carvalho-Pinto CE, García MI, Mellado M, et al. Autocrine production of IFN-γ by macrophages controls their recruitment to kidney and the development of glomerulonephritis in MRL/lpr mice. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(2):1058–1067. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.2.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pawar RD, Patole PS, Zecher D, et al. Toll-like receptor-7 modulates immune complex glomerulonephritis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2006;17(1):141–149. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hoi AY, Hickey MJ, Hall P, et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor deficiency attenuates macrophage recruitment, glomerulonephritis, and lethality in MRL/lpr mice. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(8):5687–5696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bergtold A, Gavhane A, D’Agati V, Madaio M, Clynes R. FcR-bearing myeloid cells are responsible for triggering murine lupus nephritis. Journal of Immunology. 2006;177(10):7287–7295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Moller G, Fernandez C. Macrophage depletion decreases IgG anti-DNA in cultures from (NZB × NZW)F1 spleen cells by eliminating the main source of IL-6. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1993;91(2):220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sobel ES, Morel L, Baert R, Mohan C, Schiffenbauer J, Wakeland EK. Genetic dissection of systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis: evidence for functional expression of Sle3/5 by non-T cells. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(7):4025–4032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.4025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhu J, Liu X, Xie C, et al. T cell hyperactivity in lupus as a consequence of hyperstimulatory antigen-presenting cells. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115(7):1869–1878. doi: 10.1172/JCI23049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Baechler EC, Bauer JW, Slattery CA, et al. An interferon signature in the peripheral blood of dermatomyositis patients is associated with disease activity. Molecular Medicine. 2007;13(1-2):59–68. doi: 10.2119/2006-00085.Baechler. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]