Abstract

Peptides and proteins find an ever-increasing number of applications in the biomedical and materials engineering fields. The use of non-proteinogenic amino acids endowed with diverse physicochemical and structural features opens the possibility to design proteins and peptides with novel properties and functions. Moreover, non-proteinogenic residues are particularly useful to control the three-dimensional arrangement of peptidic chains, which is a crucial issue for most applications. However, information regarding such amino acids –also called non-coded, non-canonical or non-standard– is usually scattered among publications specialized in quite diverse fields as well as in patents. Making all these data useful to the scientific community requires new tools and a framework for their assembly and coherent organization. We have successfully compiled, organized and built a database (NCAD, Non-Coded Amino acids Database) containing information about the intrinsic conformational preferences of non-proteinogenic residues determined by quantum mechanical calculations, as well as bibliographic information about their synthesis, physical and spectroscopic characterization, conformational propensities established experimentally, and applications. The architecture of the database is presented in this work together with the first family of non-coded residues included, namely, α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids. Furthermore, the NCAD usefulness is demonstrated through a test-case application example.

Introduction

The repertoire of amino acids currently available for application in life and materials sciences is rapidly expanding. Besides the 20 genetically coded α-amino acids contained in proteins, more than 700 different amino acids have been found in Nature1 (most of them, also α-amino acids), and many others have been synthesized by organic chemists.1a,2 These residues are joined under the common name of non-proteinogenic or non-coded amino acids (nc-aa). Although they are rigorously excluded from ribosomally-synthesized native peptides and proteins, several naturally occurring peptides (produced non-ribosomally) have been found to contain nc-aa.2i,3 Additionally, they are increasingly used to improve the pharmacological profile of natural peptides endowed with biological activity4 (to confer resistance against enzymatic degradation, enhance membrane permeability, or increase selectivity and affinity for a particular receptor). Nc-aa have also led to the development of efficient drugs of non-peptidic nature.5 Moreover, recent advances in biotechnology have paved the way for protein engineering with nc-aa.6 Thus, proteins containing residues with fluorescent,7 redox-active, 8 photosensitive groups,7c,9 or other side chains endowed with specific chemical reactivity10 or spectroscopic properties,11 may serve as biosensors and spectroscopic or biophysical probes, as well as to construct systems for drug delivery and diagnosis through imaging useful in medicine.6–11 Nc-aa have also found application in nanobiology to promote the self-assembly of nanostructures.12 Other remarkable applications of nc-aa include the development of bio-inspired synthetic organic polymers that emulate the shape and properties of natural peptides and proteins.13

In spite of the great significance and potential utility of nc-aa in modern biology, biomaterials engineering and medicine, structural information is only available for a limited number of them. Specifically, the intrinsic conformational preferences of nc-aa, which are typically obtained by sampling the potential energy hypersurface of small peptide systems incorporating them through sophisticated quantum mechanical calculations at the ab initio or Density Functional Theory (DFT) levels in the absence of external forces, have been reported for only several tenths of these compounds. Knowledge of such intrinsic conformational preferences is however essential to understand the features that distinguish these nc-aa from the coded ones and, therefore, for a complete and satisfactory exploitation of their capabilities. Structural data yielded by crystallographic or spectroscopic studies on peptide sequences incorporating nc-aa are also available for an increasing number of cases. Comparison of such experimental information with that derived from high-level theoretical calculations helps establish the influence of the external packing forces, the solvent effects, and the chemical environment on the conformational propensities of nc-aa.

In practice, the use of nc-aa with well-characterized conformational properties is frequently limited because the relevant information is highly dispersed. Indeed, the quantum mechanical calculations describing the intrinsic conformational preferences of these compounds are typically reported in physical chemistry journals, while their synthesis appears in organic chemistry publications. Crystallographic and spectroscopic studies of small peptide sequences containing nc-aa are usually developed by organic and peptide chemists and published in journals specialized in these fields. In contrast, many applications of nc-aa are tested by researchers working on protein engineering, medicine, or materials science. This highly dispersed information together with the wide and diverse potential applications of nc-aa made us realize that the design of a simple informatics tool integrating the contributions supplied by the different research fields would facilitate the use of these compounds in many practical applications. To this aim, we have built a database of nc-aa containing the fundamental conformational descriptors and relevant bibliographic information about experimental studies and already developed practical applications. This user-friendly on-line facility is intended as an aid to the development of new applications by combining the structural descriptors with thermodynamics criteria for a proper selection of nc-aa compatible with the user-defined requirements.

In this work, we present NCAD (Non-Coded Amino acids Database), a database conceived and created to identify the nc-aa that are compatible with a given structural motif, which is the key requirement for the application of these compounds in life and materials sciences. The database integrates structural and energetic descriptors of those nc-aa whose intrinsic conformational properties have been previously studied using ab initio or DFT quantum mechanical calculations and reported in the literature. The information about NCAD presented in the following sections is organized as explained next. First, the most relevant aspects of the database are described, such as structure, contents, technical features, and relationships allowed among the different descriptors. Next, α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids, being the first family of nc-aa integrated into the database, are presented. The conformational preferences of these compounds, which have been the subject of extensive study by our research groups, are examined and discussed using the overall information captured in the database. Finally, the utility and applicability of the database is illustrated with a simple example. Specifically, conformationally restricted analogues of the neuropeptide Met-enkephalin are designed through targeted replacements with nc-aa, using the information incorporated in the database.

NCAD: Contents, Tools and Technical Features

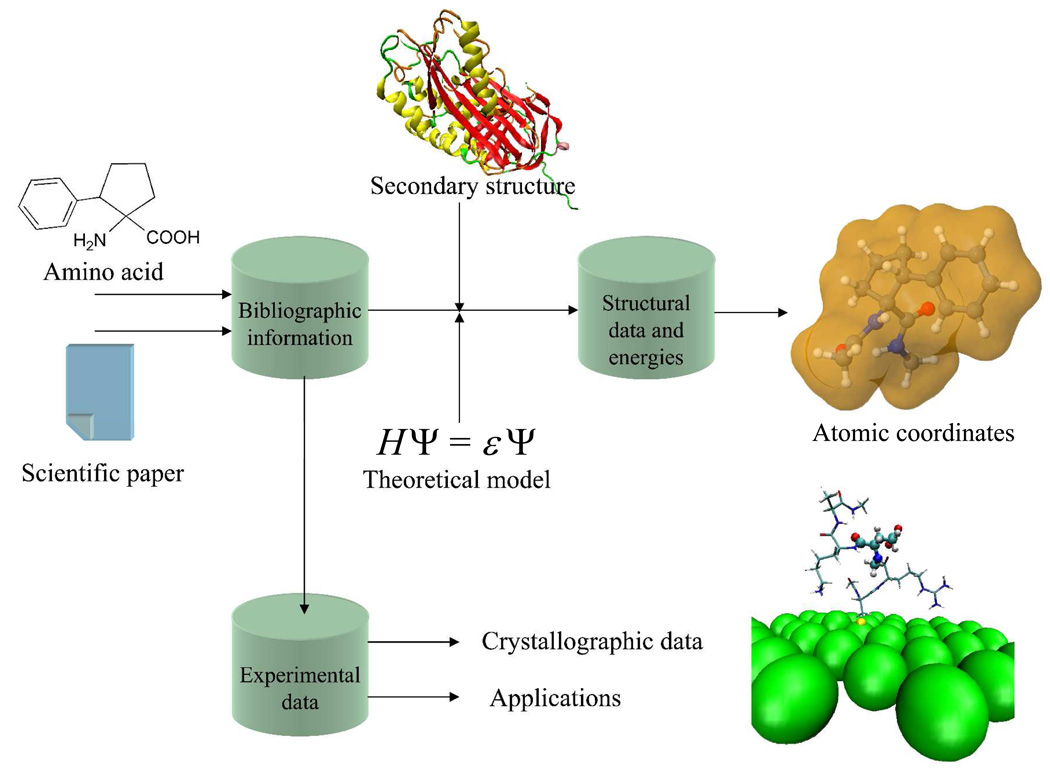

Figure 1 portrays the NCAD contents. The information contained in the database for each nc-aa is the following:

A complete description (dihedral angles, three-dimensional structure, relative energy, etc) of all the minimum energy conformations found for each amino acid using ab initio or DFT quantum mechanical calculations. It should be noted that such theoretical studies are carried out on small peptide systems of general formula RCO-Xaa-NHR’ (Xaa = amino acid; R and R’ = Me or H). When several theoretical studies were available in the literature for a particular amino acid, the information was extracted from that using the highest level of calculation. Conformational studies based on calculations less accurate than ab initio or DFT methods, i.e. molecular mechanics based on classical force-fields, semiempirical procedures, etc, have not been considered for NCAD. It is worth noting that only in a few cases are the atomic coordinates of the minimum energy conformations supplied by the authors as Supporting Information of the original article. Accordingly, in order to incorporate such coordinates into the database for all nc-aa, all minimum energy conformations for which coordinates were not available have been re-calculated using the same theoretical level as in the original study. Although this is an arduous and extremely time-consuming task, we considered it essential for the usefulness of the database. Throughout the theoretical works describing the conformational propensities of nc-aa, different nomenclature systems are used to term the energy minima located. We have unified them so that only the nomenclature introduced by Perczel et al. 14 is used in NCAD to identify the backbone conformation of the different minima characterized for each amino acid. According to it, nine different conformations can be distinguished in the potential energy surface E=E(φ,ψ) of α-amino acids,14 namely γD, δD, αD, εD, βDL, εL, αL, δL, and γL. This information is particularly useful to check the compatibility of the minima energetically accessible to a particular nc-aa with the secondary structure motifs typically found in peptides and proteins (helices, sheets, turns, etc).

Bibliographic information related to experimental data, when available. Selected references describing the synthesis and characterization of each particular amino acid in its free form, as a salt, or with the amino group adequately protected for use in peptide synthesis are given. Also references providing experimental information about the conformational preferences of the amino acid are included in NCAD. These concern mainly structural studies of peptides incorporating nc-aa using either spectroscopic or crystallographic techniques. Furthermore, in selected cases, atomic coordinates extracted from X-ray crystal structures have also been included in the database. Such three-dimensional structures allow a direct comparison with the minimum energy conformations predicted by theoretical calculations. Upon request and permission of the authors, we plan to include in NCAD examples of crystal structures of peptide sequences incorporating different nc-aa. This does not intend to be comprehensive, since we are aware that the crystal structures of peptides and proteins containing nc-aa are already stored in specialized databases, like the Cambridge Structural Database15 (CSD) and the Protein Data Bank16 (PDB).

Applications reported for each particular nc-aa divided into two main categories, namely, those related to the biological properties of the amino acid (or compounds incorporating it), and applications in materials science. The most relevant publications in each field, either papers in scientific journals or patents, are given.

Figure 1.

Schematic graphic algorithm showing the structure of the NCAD database.

As commented above, NCAD has been conceived to contain all those nc-aa whose intrinsic conformational propensities have been determined through ab initio or DFT quantum mechanical calculations. Such amino acids may be chiral or not. In the former case, two enantiomeric forms do exist for a given amino acid. Obviously, the conformational preferences of only one enantiomer have been calculated and are included in the database, since those of the enantiomeric species may be obtained by simply changing the signs of the dihedral angles. The bibliographic information concerning synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, experimental structural properties, and applications included in the database covers the two enantiomers as well as the racemic form, when applicable.

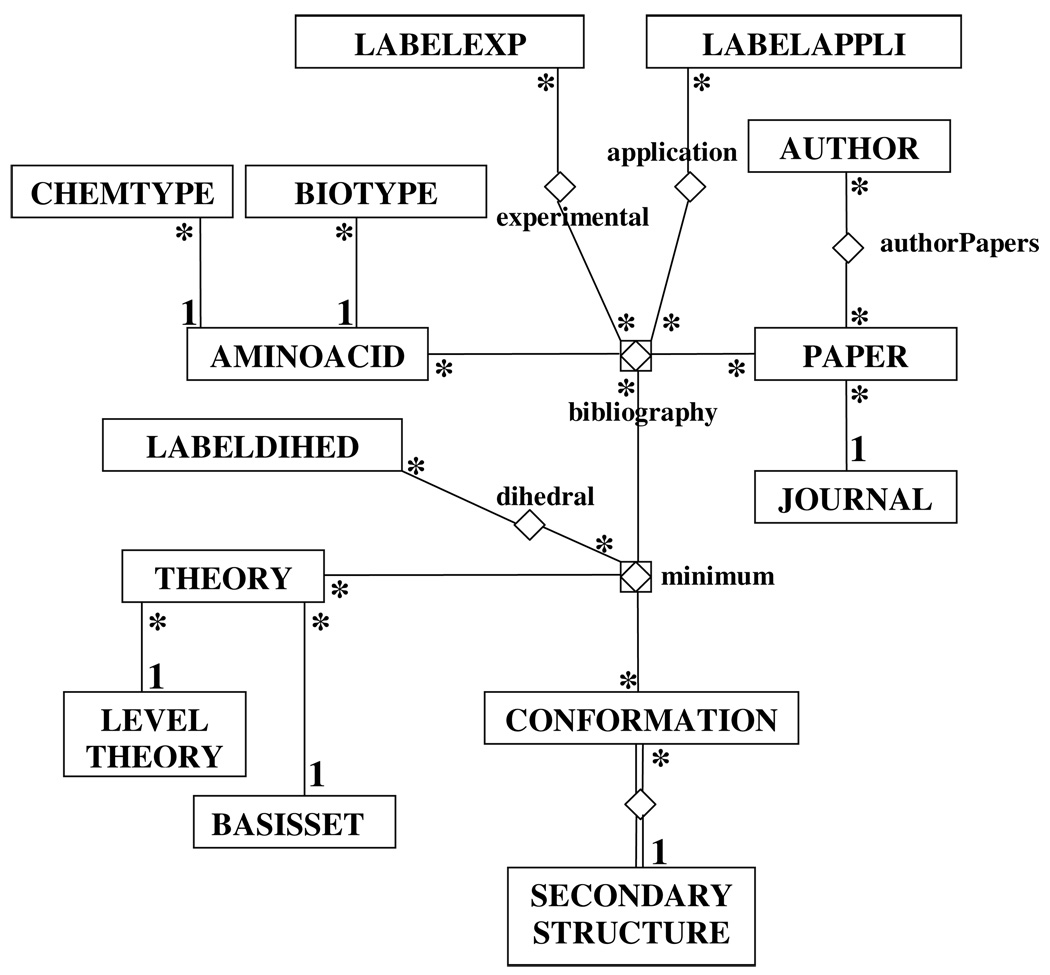

Figure 2 shows the entity-relationship diagram17 (ERD) of NCAD. This diagram summarizes the conceptual representation of the information stored in the database, as well as their inter-relational scheme. The entities are shown in squares, the relationships are lines between boxes, and their multiplicities are displayed using numbers or stars following ERD standards. All the experimental and theoretical information in the database has been extracted from relevant literature sources and, accordingly, all data available in NCAD for a given amino acid are connected with the bibliographic references. Labels (labelexp, labelappli entities) allow the identification of the applications described for each amino acid as well as the experimental data. The database also stores the atomic coordinates of the minimum energy conformations (minimum) predicted by a particular quantum mechanical method (theory), which have been extracted from the literature (bibliography), and its correspondence with secondary structure motifs (conformation-secondarystructure). Furthermore, internal coordinates, such as dihedrals angles (dihedrals) for both the backbone and the side chain, can be easily obtained from the database for each minimum energy conformation of a given amino acid.

Figure 2.

Chen’s diagram showing the relationships among the entities in NCAD.

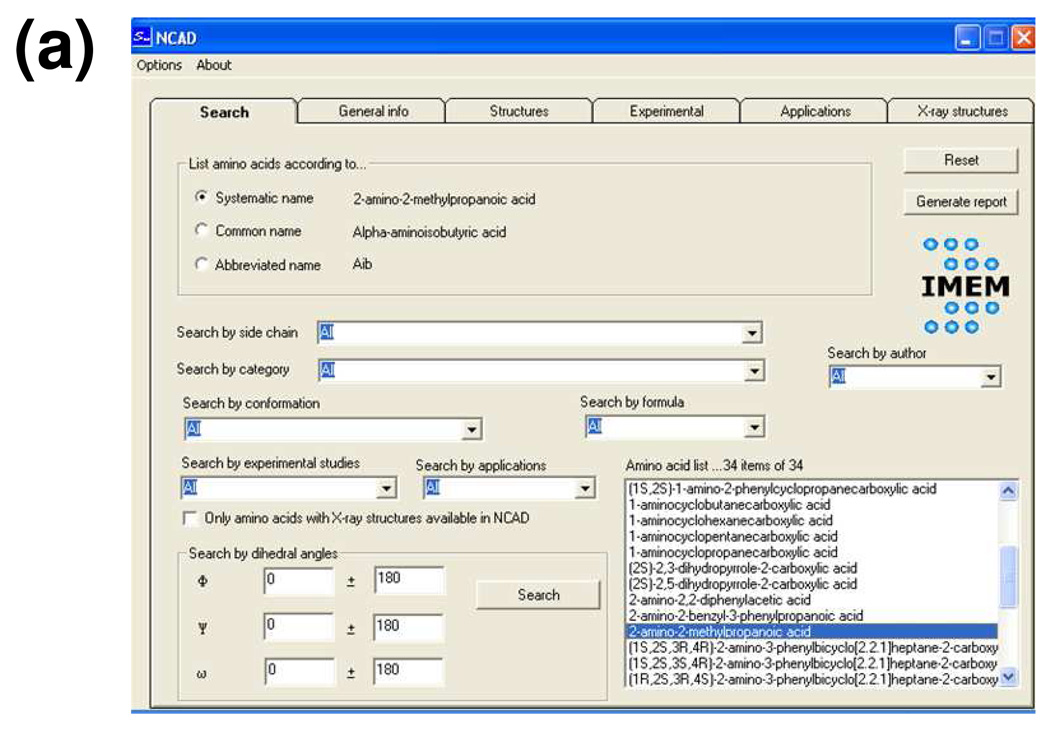

NCAD can be easily used by non-experts in informatics, since the interface designed applies a simple windows system. This system provides access to six folders. The first one (Figure 3a) is used to define the criteria (one or several, i.e. .AND. or .OR.) applied to the search. These may be chosen among the following: (i) the chemical nature of the side chain, i.e. aromatic, aliphatic, charged, or polar (non-charged); (ii) the category, which corresponds to the structural feature distinguishing a particular family of nc-aa, e.g. α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids, dehydro α-amino acids, N-substituted α-amino acids, ω-amino acids, etc; (iii) the molecular formula of the amino acid; (iv) the type of backbone conformation located among the energy minima, according to the nomenclature established by Perczel et al.,14 i.e. γD, δD, αD, εD, βDL, εL, αL, δL, and γL; (v) the (φ,ψ) backbone dihedral angles corresponding to such energy minima, with both the values and the tolerance being specified by the user; (vi) the name of the researcher who performed the theoretical or experimental investigation (author); (vii) the experimental studies reported in the literature relative to synthesis and characterization or to conformational properties; and (ix) the applications (in medicine or materials science) described.

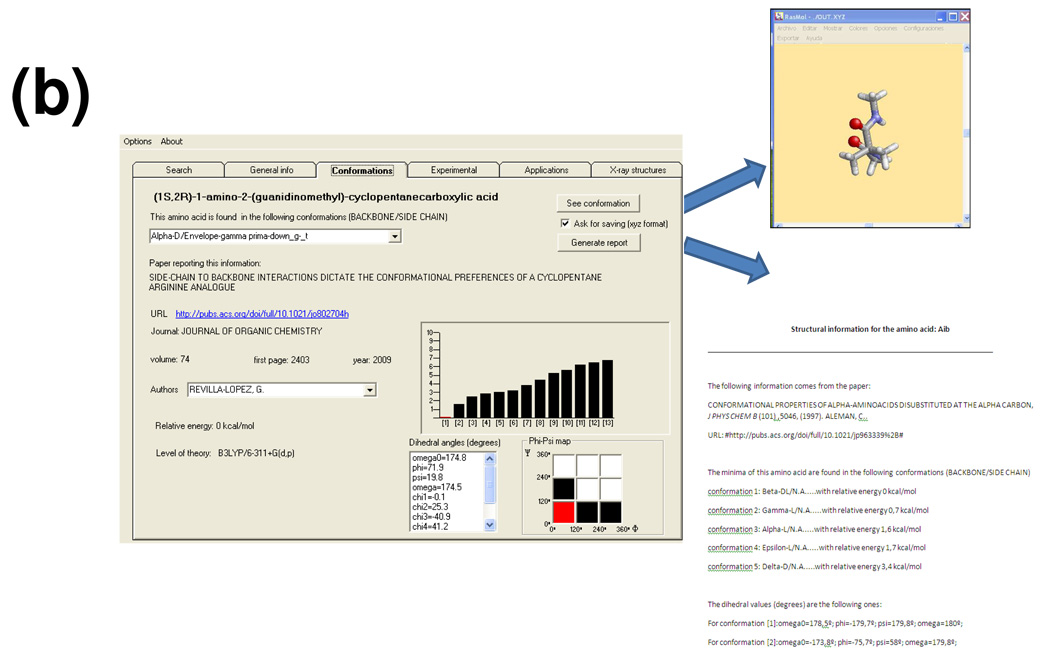

Figure 3.

Interface system used to interact with the NCAD database. (a) Window used to perform the search. (b) Window showing details about the theoretical study at the highest quantum mechanical level reported in the literature for the nc-aa selected; the Rasmol 3D-view of a selected minimum energy conformation and the report are also displayed (both are generated through internal calls of the interface upon the user’s request).

The amino acids fulfilling all the selected criteria are displayed in a list (Figure 3a) (by default, when no criterion is specified, all residues included in NCAD are listed) and a report with the search criteria and results may be generated. The user can select three different nomenclatures to indicate the amino acids names: systematic, common or abbreviated (usually resembling the three-letter code used for proteinogenic amino acids), e.g. 2-amino-2-methylpropanoic acid, α-aminoisobutyric acid or Aib, respectively. It should be noted that the common and abbreviated names are not available for all residues.

Selection of an amino acid from this list allows access to all the information stored in the database for this particular residue, which is presented in the remaining five folders. The “general info” folder provides the chemical description of the amino acid, including a graphical scheme of its chemical structure and the types of experimental studies and applications available. These data together with the corresponding bibliographic references stored in the database for the selected amino acid may be exported to a report. The “conformations” folder (Figure 3b) displays information extracted from the theoretical study performed at the highest quantum mechanical level reported in the literature. Specifically, it includes the bibliographic source, the number of minima characterized, the list of dihedral angles and energy of each minimum, the position of each minima within the Ramachandran map, and the quantum mechanical method used in the theoretical study. A report containing this information may be generated. Furthermore, this folder allows a graphical inspection of each minimum energy conformation with the molecular visualization software Rasmol.18 This is made possible by accessing the atomic coordinates stored in the database through an internal call of the interface. The atomic coordinates of each minimum energy conformation may be also extracted. The next two folders provide bibliographic data about experimental studies (synthesis and characterization, conformational propensities) and reported applications in medicine and materials science. Such bibliographic information is not intended to be comprehensive but rather present some significant publications in the field. Thus, these folders supply essential information reported for the amino acid considered, but a systematic literature search is recommended if this amino acid is finally selected by the user for practical applications. Finally, the last folder allows access to the X-ray crystal structures of peptide sequences containing the selected amino acid that are available in the database. Three-dimensional visualization of these structures is made through the Rasmol software.18

α-Tetrasubstituted α-Amino Acids

Because of our interest in α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids and their relevance in the design of peptides with well-defined conformational properties,19 this is the first family of nc-aa integrated into NCAD. Table 1 lists the 29 α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids whose intrinsic conformational propensities have been determined to date using ab initio or DFT quantum mechanical methods20–37 according to a literature search. This list is expected to be dynamic and thus be updated when studies on new compounds in this category are reported. Other families of nc-aa will be integrated into NCAD in the near future.

Table 1.

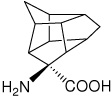

α-Tetrasubstituted α-amino acids stored in NCAD. The systematic name (and the common and abbreviated names,a when available), the chemical structure, and the reference reporting the quantum mechanical study are given for each amino acid.

| Abbreviated name |

Systematic name (common name) |

Structure | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

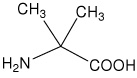

| Aib | 2-amino-2-methylpropanoic acid (α-aminoisobutyric acid) |

|

20 |

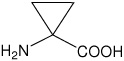

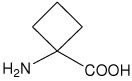

| Ac3c | 1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid |  |

21 |

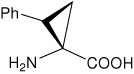

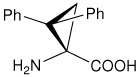

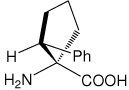

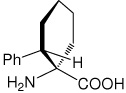

| (1S,2S)c3Phe | (1S,2S)-1-amino-2-phenylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid |

|

21 |

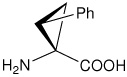

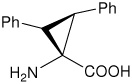

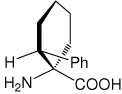

| (1S,2R)c3Phe | (1S,2R)-1-amino-2-phenylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid |

|

21 |

| l-c3Dip | (S)-1-amino-2,2-diphenylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid |

|

22 |

| (2S,3S)c3diPhe | (2S,3S)-1-amino-2,3- diphenylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid |

|

23 |

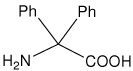

| Dpg | 2-amino-2,2-diphenylacetic acid (diphenylglycine) |

|

24 |

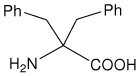

| Dbg | 2-amino-2-benzyl-3-phenylpropanoic acid (dibenzylglycine) |

|

25 |

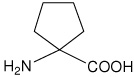

| Ac4c | 1-aminocyclobutanecarboxylic acid |  |

26 |

| Ac5c | 1-aminocyclopentanecarboxylic acid |  |

27 |

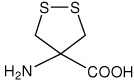

| Adt | 4-amino-1,2-dithiolane-4-carboxylic acid |

|

28 |

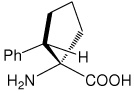

| (1S,2S)c5Phe | (1S,2S)-1-amino-2-phenylcyclopentanecarboxylic acid |

|

29 |

| (1S,2R)c5Phe | (1S,2R)-1-amino-2-phenylcyclopentanecarboxylic acid |

|

29 |

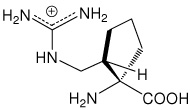

| (1S,2S)c5Arg | (1S,2S)-1-amino-2-(guanidinomethyl)- cyclopentanecarboxylic acid |

|

30 |

| (1S,2R)c5Arg | (1S,2R)-1-amino-2-(guanidinomethyl)- cyclopentanecarboxylic acid |

|

30 |

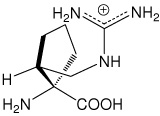

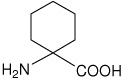

| Ac6c | 1-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid |  |

31 |

| (1S,2S)c6Phe | (1S,2S)-1-amino-2-phenylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid |

|

32 |

| (1S,2R)c6Phe | (1S,2R)-1-amino-2-phenylcyclohexanecarboxylic acid |

|

32 |

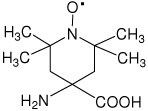

| Toac | 4-amino-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl-4- carboxylic acid |

|

33 |

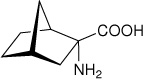

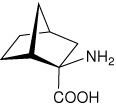

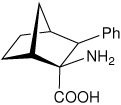

| — | (1S,2R,4R)-2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2- carboxylic acid |

|

34 |

| — | (1R,2R,4S)-2-aminobicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2- carboxylic acid |

|

34 |

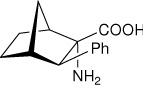

| — | (1S,2S,3R,4R)-2-amino-3- phenylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid |

|

34 |

| — | (1S,2S,3S,4R)-2-amino-3- phenylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid |

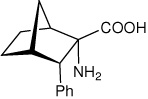

|

34 |

| — | (1R,2S,3R,4S)-2-amino-3- phenylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid |

|

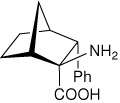

34 |

| — | (1R,2S,3S,4S)-2-amino-3- phenylbicyclo[2.2.1]heptane-2-carboxylic acid |

|

34 |

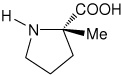

| l-(αMe)Pro | (2S)-2-methylpyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid [(α-methyl)proline)] |

|

35 |

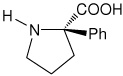

| l-(αPh)Pro | (2R)-2-phenylpyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid [(α-phenyl)proline] |

|

35 |

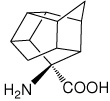

| — | (1S,2R,3R,5R,6R,7S,8R,9R,10R)-8- aminopentacyclo[5.4.0.0(2,6).0(3,10).0(5,9)]-undecane-8- carboxylic acid |

|

36 |

| — | (S)-4-aminopentacyclo[6.3.0.0(2,6).0(3,10).0(5,9)]- undecane-4-carboxylic acid |

|

37 |

In the abbreviated name, the configuration is defined by the l/d nomenclature when only the α carbon is chiral (l usually corresponding to S). When two or more chiral centers are present, the R/S stereochemical descriptors are used instead.

α-Tetrasubstituted amino acids are characterized by an α-carbon atom bearing four substituents (different from hydrogen) and hence are also called quaternary amino acids. They are usually divided into two subtypes, depending on whether the α carbon is involved in a cyclic structure or not. Notably, the former has been studied much more frequently, the number of entries in the database being 24 and 5, respectively. Regarding chirality, 9 residues in Table 1 present two identical substituents at the α carbon and are therefore achiral, namely Aib, Ac3c, Dpg, Dbg, Ac4c, Ac5c, Adt, Ac6c, and Toac. The remaining 20 amino acids present at least one chiral center. In the latter case, only the low energy minima of one enantiomer (usually l) have been considered for incorporation into NCAD, those of the other enantiomer being easily deducible by simply changing the sign of both (φ,ψ) angles. When two or more chiral centers are present in the molecule, the stereochemistry is indicated through the R/S instead of the l/d nomenclature (the S configuration at the α carbon usually corresponding to l).

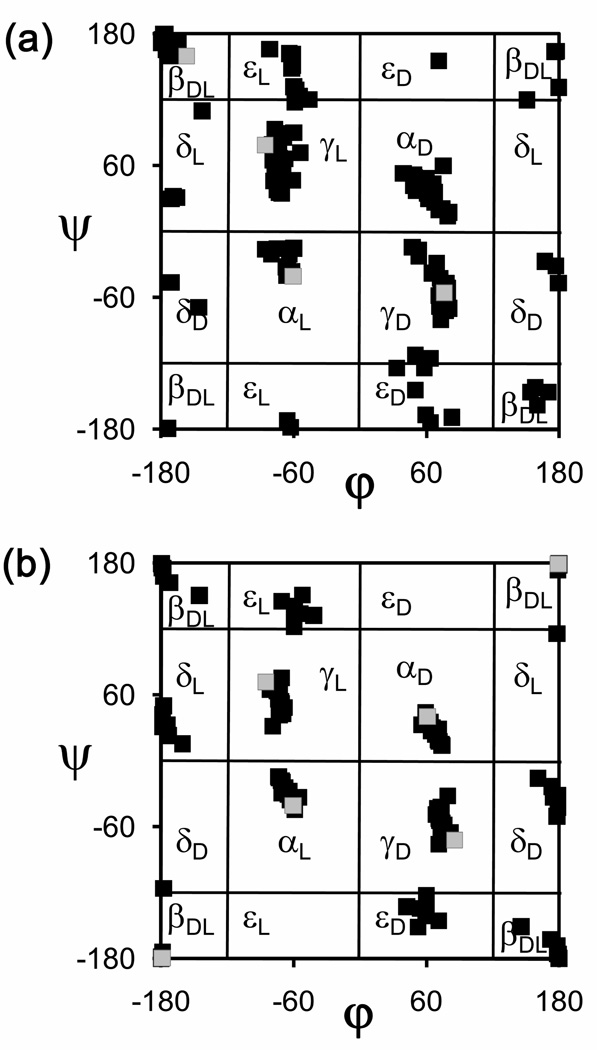

Figure 4 presents Ramachandran maps corresponding to the (φ,ψ) backbone dihedral angles of all the energy minima reported for the 29 α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids included in the database.20–37 Those chiral in nature (Figure 4a) are represented together with the minima calculated by ab initio quantum mechanical methods for the N-acetyl-N’-methylamide derivative of l-alanine38 (MeCO-Ala-NHMe), as a reference for proteinogenic amino acids. The non-chiral α-tetrasubstituted residues (Figure 4b) are compared with the glycine minima (calculated ab initio on MeCO-Gly-NHMe38). The latter map is centrosymmetric, since two points (φ,ψ) and (−φ,−ψ) are equivalent for achiral amino acids.

Figure 4.

Ramachandran maps showing all the minimum energy conformations predicted by quantum mechanical calculations for the α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids included in NCAD (see Table 1): (a) chiral residues (black squares) compared with Ala (grey squares); (b) achiral residues (black squares) compared with Gly (grey squares).

As can be seen, tetrasubstitution at the α carbon affects the location of the minimum energy conformations typically found for proteinogenic residues. Specifically, the γL conformation (intramolecularly hydrogen-bonded seven-membered ring, also denoted C7 conformation), which was found38 at (φ,ψ) = (−86,79) and (−86,72) for Ala and Gly, respectively, tends to evolve towards lower absolute ψ values upon replacement of the α-hydrogen atom by a substituent. The distortion of the ψ dihedral angle shown by quaternary α-amino acids is maximal for 1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid (Ac3c, Table 1), which presents a γL minimum at (φ,ψ) = (−77,34),21 as a consequence of the peculiar stereoelectronic properties of the three-membered ring.39

The ψ backbone dihedral angle characterized for the α-helix conformation also deviates to lower absolute values when the α carbon is tetrasubstituted. Thus, the αL conformation of Ala was located at (φ,ψ) = (−61,−41),38 (as was for Gly38) whereas that of its α-methylated counterpart, α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib, Table 1) is found at (−65,−31).20 A similar trend, or even more pronounced, is observed for most amino acids in Table 1, either chiral or not. Thus, for example, Ac5c, Ac6c, and l-c3Dip exhibit αL minima with (φ,ψ) values (−73,−15),27 (−70,−20),31 and (−80,−20),22 respectively. This apparently minor change brings about important consequences and, indeed, Aib and other quaternary α-amino acids are known to stabilize the 310-helix19 rather than the α-helix typically found for proteinogenic amino acids. The slight difference in the backbone dihedral angles translates into significant variations in the parameters associated to each helical structure, including the hydrogen bonding pattern, which involves residues i and i+3 in the 310-helix and residues i and i+4 in the α-helix.40 Quaternary α-amino acids can therefore be used to design helical structures exhibiting hydrogen-bonding schemes and geometries different from those formed by standard amino acids.

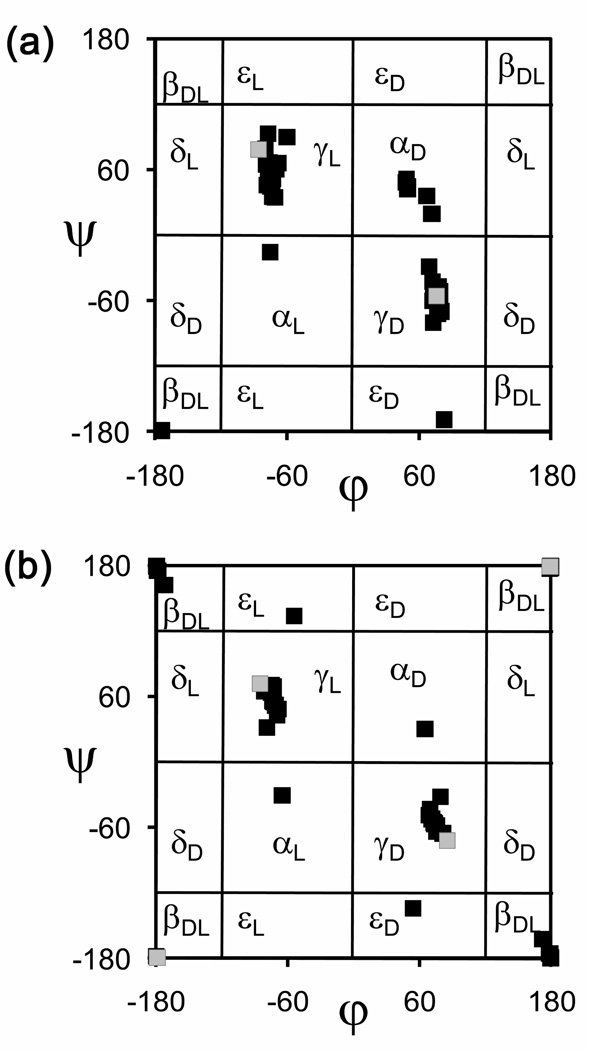

Another effect of α-tetrasubstitution is the stabilization of minimum energy conformations that are not usually detected experimentally for coded amino acids because they are energetically unfavored. This feature is clearly observed when only the minima found for quaternary amino acids within a relative energy interval of 2.0 kcal/mol, i.e. those energetically accessible, are considered and compared with Ala or Gly (see Figures 5a and 5b for chiral and achiral residues, respectively). Specifically, the εD and εL regions of the (φ,ψ) map are visited by some α-tetrasubstituted amino acids, like Aib20 and (1S,2R)c3Phe21 but not by Ala38 or Gly.38 Furthermore, the αL conformation is energetically accessible to several of the nc-aa considered, whereas the Ala38 αL minimum is unfavored by near 4.0 kcal/mol with respect to the global minimum and the same holds true for Gly.38 Moreover, minima in the αD region are found under the threshold of 2.0 kcal/mol for several amino acids in Table 1, among which are not only those of achiral nature, and therefore presenting an identical propensity to accommodate αL and αD conformations, but also some exhibiting an l configuration, like (1S,2S)c5Arg.30 Therefore, tetrasubstitution at the α carbon may result in the stabilization of conformations typically accessed by d amino acids even if the l chirality is maintained.

Figure 5.

As in Figure 4, but only minimum energy conformations with a relative energy below 2.0 kcal/mol are considered.

The features commented above illustrate the great conformational impact that may derive from the presence of α-tetrasubstituted amino acids in a peptide chain, which has been demonstrated in numerous investigations.19,40 Nowadays, the usefulness of this family of nc-aa in the control of peptide conformation is beyond doubt, but the practical application to the design of biologically relevant molecules or peptide-based materials is only in its earliest stages. NCAD is intended to mean a significant contribution to its development.

In Silico Molecular Engineering for Targeted Replacements in Met-Enkephalin Using NCAD: A Test Case

We provide in this section a computational design study aimed at constructing mutants of Met-Enkephalin using information extracted from NCAD. This is not intended to provide a deep and rigorous investigation of the resulting peptides, but to illustrate the potential utility of the database in applications involving peptide and protein engineering through a test case.

The Met-enkephalin neurotransmitter is a pentapeptide (Tyr-Gly-Gly-Phe-Met) that interacts with opioid receptors.41 Opioid systems play a significant role in pain medication and opiate dependence, regulate dopamine release and are thought to be important for drug-induced reward. Interestingly, no unique native structure has been found for Met-enkephalin, whose conformational flexibility has been examined using a wide variety of experimental techniques (e.g. X-ray crystallography, NMR, circular dichroism, and infrared, ultraviolet and fluorescence spectroscopies).42 Accordingly, this short peptide is able to adopt different conformations depending on the biological context, which explains its ability to interact with opioid receptors of the µ, κ, and δ types.41 The multiple conformational states accessible to Met-enkephalin are therefore at the basis of its poor selectivity of action. A number of theoretical studies using both conventional and advanced simulation methods based on molecular dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) algorithms have been devoted to explore the energy landscape of Met-enkephalin and have shown its ill-defined conformational state.43–45

We have examined the information stored in NCAD to propose targeted replacements able to stabilize one of the conformations experimentally detected for Met-enkephalin. Specifically, we considered the conformation identified by NMR for Met-enkephalin in fast-tumbling bicelles.46 The atomic coordinates of this conformation were extracted from the Protein Data Bank16 (PDB code: 1PLW).

The peptide was placed in the center of a cubic simulation box (a = 44.6 Å) filled with 2916 explicit water molecules, which were represented using the TIP3 model.47 The N- and C-termini were described using the positively charged ammonium and the negatively charged carboxylate groups, respectively. All the MD simulations were performed using the NAMD computer program.48 In order to equilibrate the density of the simulation box, different consecutive rounds of short MD runs were performed. Thus, 0.5 ns of NVT-MD at 350K were used to homogeneously distribute the solvent in the box. Next, 0.5 ns of NVT-MD at 298K (thermal equilibration) and 0.5 ns of NPT-MD at 298K (density relaxation) were run. After this, the peptide conformation was equilibrated by running a 3 ns trajectory of NVT-MD at 298K. The last snapshot of this trajectory was used to determine the (φ,ψ) dihedral angles of the three central residues of Met-enkephalin (Gly-Gly-Phe), which define the most flexible region of the peptide. The (φψ) values thus obtained were (83,77) for Gly2, (61,−81) for Gly3, and (−66,−38) for Phe4, which correspond to the αD, γD, and αL conformations, respectively, according to Perczel’s nomenclature.14

These structural parameters have been used to design targeted substitutions in Met-enkephalin aimed at reducing the flexibility of the peptide backbone so that the particular conformation selected is stabilized. This molecular design pursues the validation of the performance and usefulness of the NCAD database. The following criteria were considered in the design: (i) the side chain functionality of the nc-aa selected should be similar to that of the natural residue to be replaced, which is essential to preserve the biological functions of the peptide; and (ii) the intrinsic conformational properties of the selected nc-aa must be consistent with the conformation adopted by the targeted residue in the parent peptide. Based on these selection criteria and the structural parameters provided by MD for the Gly-Gly-Phe peptide fragment, three different mutations were proposed using the information in NCAD:

Replacement of Gly2 or Gly3 by α-aminoisobutyric acid (Aib, see Table 1). This amino acid bears two methyl groups at the α position (instead of the two α-hydrogen atoms in Gly) and presents low-energy minima20 located at the αL and γL regions of the Ramachandran map, with (φ,ψ) angles (−65,−31) and (−76,58), and relative energies 1.7 and 0.0 kcal/mol, respectively, at the MP2/6-31G(d)//HF/6-31G(d) level. Given the non-chiral nature of Aib, these minimum energy conformations are equivalent to the enantiomeric αD and γD, characterized by (φ,ψ) dihedrals (65,31) and (76,−58), respectively. The latter values fit very well with those provided by MD for the Gly2 [(83,77)] and Gly3 [(61,−81)] residues of Met-enkephalin. The mutants resulting from these substitutions are denoted G2 and G3.

Replacement of Phe4 by (2R,3R)-1-amino-2,3-diphenylcyclopropanecarboxylic acid, known in the abbreviated form as (2R,3R)c3diPhe. This cyclic α-tetrasubstituted residue contains a cyclopropane ring bearing two vicinal phenyl substituents in a trans relative disposition [see the (2S,3S) enantiomer in Table 1]. It retains the side chain of Phe and shows an energy minimum of the αL type characterized by (φ,ψ) values (−67,−27),23 which closely resemble those obtained for Phe4 in Met-enkephalin in the MD trajectory described above, (−66,−38). Moreover, (2R,3R)c3diPhe has been shown experimentally to exhibit a high propensity to adopt αL conformations due to the interaction between the two rigidly held aromatic groups and the peptide backbone.49 The mutant resulting from the replacement of Phe4 by (2R,3R)c3diPhe in Met-enkephalin is denoted F4.

MD trajectories of 6 ns were performed for the wild-type peptide and the three mutants designed. The starting geometries for the mutants were constructed using the coordinates stored in the database for the minimum energy conformation selected for each nc-aa. The protocols applied for thermal equilibration and density relaxation were identical to those described above. All the force-field parameters for the MD simulations were extracted from the AMBER libraries,50 with the exception of the electrostatic charges for the nc-aa, which were taken from the papers quoted in the database.

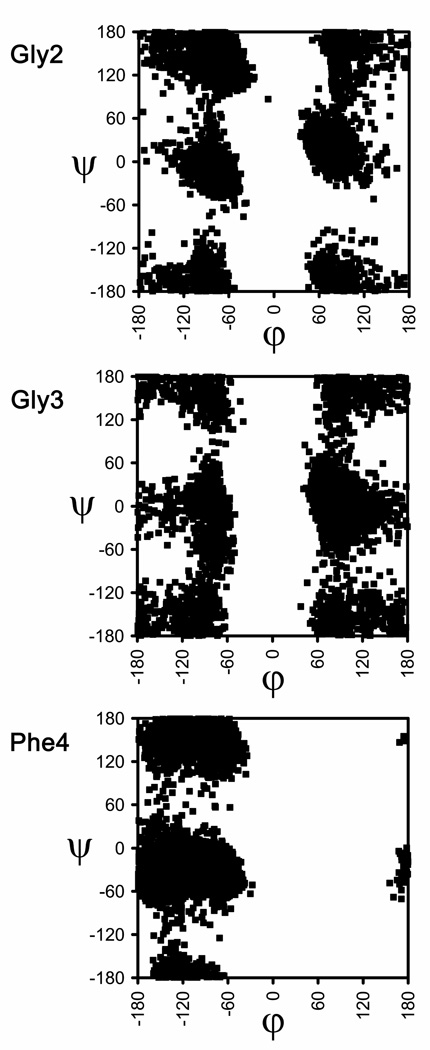

Figure 6 shows the accumulated Ramachandran plots obtained through 6 ns of simulation corresponding to the Gly2, Gly3 and Phe4 residues for the wild-type peptide. As can be seen, the two Gly residues sample all the accessible regions of the (φ,ψ) space, which is consistent with the large conformational flexibility observed for Met-enkephalin in aqueous solution both by experimental42a,b,d–f and theoretical techniques.43–45 The Phe4 residue also exhibits a great flexibility, although it only explores conformations in the left-half part of the map, as expected from its l configuration (in comparison, for the non-chiral Gly residue, the left and right parts of the map are energetically equivalent). Therefore, all three residues are actually found to adopt (φ,ψ) values in all the regions that are energetically accessible to them. In other words, no selectivity is detected towards a particular structure among those allowed to l (in the case of Phe) or achiral (in the case of Gly) coded residues. It is worth noting that the sampling of the conformational space shown in Figure 6 is in excellent agreement with that obtained for the same peptide using replica exchange MD.45

Figure 6.

Backbone (φ,ψ) dihedral angles distributions obtained for the Gly2, Gly3, and Phe4 residues in wild-type Met-enkephalin.

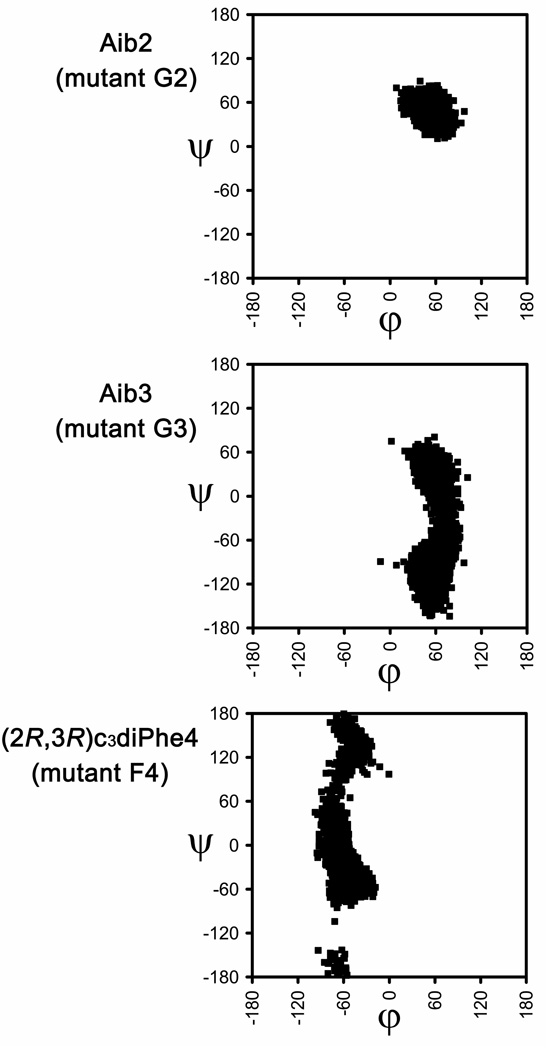

Figure 7 shows the (φ,ψ) distributions obtained for the nc-aa included in mutants G2, G3 and F4 of Met-enkephalin. Table 2 displays the population of the different backbone conformations, which is expressed in terms of number of visits to a certain region of the Ramachandran map during the MD trajectories. These data provide evidence for the great conformational selectivity induced by the α-tetrasubstituted amino acids used. In particular, for the G2 mutant, the Aib residue (Gly2 substitute) falls exclusively in the αD region. Accordingly, the substitution designed using NCAD successfully restricts the conformational flexibility of the Gly2 residue and, moreover, preserves the selected arrangement. Thus, the replacement of Gly2 by Aib results in the stabilization of the conformation adopted by the coded residue in the starting geometry.

Figure 7.

Backbone (φ,ψ) dihedral angles distributions obtained for the Aib2, Aib3, and (2R,3R)c3diPhe4 residues in the G2, G3, and F4 mutants of Met-enkephalin.

Table 2.

Relative shares of populations (%) found for selected residues in wild-type Met-enkephalin (Gly2, Gly3, and Phe4) and for the α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids included in the G2, G3, and F4 mutants.a

| αD | εD | γD | δD | βDL | δL | γL | εL | αL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gly2 | 25.1 | 8.9 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 10.1 | 34.0 | 12.3 |

| Gly3 | 29.2 | 7.3 | 30.3 | 3.6 | 7.0 | 1.9 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| Phe4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 19.1 | 18.4 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 21.7 | 34.4 |

| Aib2 (G2) | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Aib3 (G3) | 29.5 | 4.4 | 66.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| (2R,3R)c3diPhe4 (F4) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.1 | 4.7 | 82.2 |

The nine types of backbone conformation defined in ref. 14 have been considered.

Replacement of Gly3 by Aib also has a conformational confinement effect although less intense. Indeed, only the αD, γD, and εD structures are adopted by the Aib residue in the G3 mutant (Figure 7), their respective populations being 29.5%, 66.1% and 4.4% (Table 2). In contrast, Gly3 in the unmodified peptide was found to visit all nine regions used by Perczel et al. 14 to describe the conformational space. We also note that the two regions most populated by Gly3 in the wild-type system, namely αD and γD, are kept by Aib in the G3 mutant. Thus, although the Gly-Aib exchange proved less restrictive in G3 than in G2, the results obtained for the G3 mutant illustrate again that properly selected nc-aa can be successfully used to reduce the conformational freedom of biological (macro)molecules through the stabilization of selected secondary structure motifs.

To further evidence the magnitude of the conformational restrictions introduced by the nc-aa in this study, Table 3 displays the ratio between the populations of the conformations found for the quaternary α-amino acids and those of the corresponding coded residues in the wild-type peptide. For instance, mutant G3 increases the population obtained for the γD conformation of Gly3 in Met-enkephalin by a factor of 2.2.

Table 3.

Ratio between the populations of conformationsa found for the α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids in the G2, G3, and F4 mutants and the corresponding proteinogenic residues in wild-type Met-enkephalin.

| αD | εD | γD | δD | βDL | δL | γL | εL | αL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aib2 (G2) | 4.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Aib3 (G3) | 1.0 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| (2R,3R)c3diPhe4 (F4) | –b | –b | –b | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 2.4 |

The nine types of backbone conformation defined in ref. 14 have been considered.

This conformation was not adopted by the α-tetrasubstituted residue.

In the F4 mutant, the restricted geometry of (2R,3R)c3diPhe affects mainly the φ angle, which remains fixed in the neighborhood of −60° during the whole MD trajectory (Figure 7). In comparison, the Phe4 residue in Met-enkephalin was found to cover all the possible negative values of φ: −180° < φ < −50° (Figure 6). As a result, the αL conformation, which corresponds to that adopted by Phe4 in the original arrangement selected, significantly increases its population from the wild-type peptide (34.4%) to the F4 mutant (82.2%) and becomes the most visited structure during the simulation of the latter peptide. The selectivity ratio for the F4 mutant is 4.5 and 2.4 for the γL and αL regions, respectively (Table 3). Accordingly, the nc-aa used as a Phe4 substitute also stabilizes the desired conformation and further proves the utility and potential applicability of the new database.

Conclusions

NACD (Non-Coded Amino acids Database) is an easy-to-use research tool that integrates the intrinsic conformational preferences of non-coded amino acids to facilitate their use in the design of peptide- or protein-based compounds useful in different fields of the life and materials sciences. Our aim is to provide the outcome of structural studies of nc-aa, including their properties and chemical characteristics, obtained by scientists in the organic and physical chemistry disciplines to those focusing on biological, bioengineering and medicinal applications, bringing the fields together. The information provided in NCAD, which is not available in other databases, is also expected to be a useful resource for protein designers, modelers and experts in bioinformatics. The present paper presents the structure and informatics architecture of the database, the interface that connects the database with the users, the description of the first family of nc-aa integrated into the database (α-tetrasubstituted α-amino acids), and a test case showing the applicability of the database. Researchers can now easily select the most appropriate residue from a collection of nc-aa with well established conformational properties and introduce it in a peptide sequence or any other (macro)molecule. Additional families of non-proteinogenic amino acids will be included in NCAD in due course.

Acknowledgements

Computer resources were generously provided by the Centre de Supercomputació de Catalunya (CESCA). Financial support from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación - FEDER (grants CTQ2007-62245 and CTQ2008-00423-E/BQU; Ramón y Cajal contract for D.Z.), Gobierno de Aragón (research group E40), and Generalitat de Catalunya (research group 2009 SGR 925; XRQTC; ICREA Academia prize for excellence in research to C.A.) is gratefully acknowledged. This project has been funded in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the view of the policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported [in part] by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

References

- 1.(a) Hughes AB, editor. Amino Acids, Peptides and Proteins in Organic Chemistry; Volume 1: Origins and Synthesis of Amino Acids. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Barrett GC, Elmore DT. Amino Acids and Peptides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mauger AB. J. Nat. Prod. 1996;59:1205. doi: 10.1021/np9603479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wagner I, Musso H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1983;22:816. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Soloshonok VA, Izawa K, editors. Asymmetric Synthesis and Application of α-Amino Acids. Washington DC: American Chemical Society; 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cativiela C, Ordóñez M. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:1. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Michaux J, Niel G, Campagne J-M. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2093. doi: 10.1039/b812116h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ordóñez M, Rojas-Cabrera H, Cativiela C. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:17. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.09.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Cativiela C, Díaz-de-Villegas MD. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:569. [Google Scholar]; (f) Ordóñez M, Cativiela C. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2007;18:3. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Bonauer C, Walenzyk T, König B. Synthesis. 2006:1. [Google Scholar]; (h) Aurelio L, Brownlee RTC, Hughes AB. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:5823. doi: 10.1021/cr030024z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Lelais G, Seebach D. Biopolymers (Pept. Sci.) 2004;76:206. doi: 10.1002/bip.20088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Toniolo C, Brückner H, editors. Peptaibiotics: Fungal Peptides Containing α-Dialkyl α-Amino Acids. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kastin AJ, editor. Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides. London: Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]; (c) Degenkolb T, Bruckner H. Chem. Biodiversity. 2008;5:1817. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Schwarzer D, Finking R, Marahiel MA. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003;20:275. doi: 10.1039/b111145k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Jensen KJ, editor. Peptide and Protein Design for Biopharmaceutical Applications. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nestor JJ. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:4399. doi: 10.2174/092986709789712907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Horne WS, Gellman SH. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1399. doi: 10.1021/ar800009n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Seebach D, Gardiner J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1366. doi: 10.1021/ar700263g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Chatterjee J, Gilon C, Hoffman A, Kessler H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1331. doi: 10.1021/ar8000603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cowell SM, Lee YS, Cain JP, Hruby VJ. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:2785. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Sagan S, Karoyan P, Lequin O, Chassaing G, Lavielle S. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:2799. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Adessi C, Soto C. Curr. Med. Chem. 2002;9:963. doi: 10.2174/0929867024606731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Kleemann A, Engel J, Kutscher B, Reichert D, editors. Pharmaceutical Substances: Syntheses, Patents, Applications. Stuttgart: Thieme; 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ersmark K, Del Valle JR, Hanessian S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1202. doi: 10.1002/anie.200605219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Menard J, Patchett AA. Adv. Protein Chem. 2001;56:13. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(01)56002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Voloshchuk N, Montclare JK. Mol. BioSyst. 2010;6:65. doi: 10.1039/b909200p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wu X, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12497. doi: 10.1021/ja9026067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartman MCT, Josephson K, Szostak JW. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:4356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509219103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang L, Schultz PG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:34. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Hendrickson TL, De Crécy-Lagard V, Schimmel P. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004;73:147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.012803.092429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wang L, Brock A, Herberich B, Schultz PG. Science. 2001;292:498. doi: 10.1126/science.1060077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Lee HS, Guo J, Lemke E, Dimla R, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12921. doi: 10.1021/ja904896s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Summerer D, Chen S, Wu N, Deiters A, Chin JW, Schultz PG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:9785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603965103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Vázquez ME, Nitz M, Stehn J, Yaffe MB, Imperiali B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10150. doi: 10.1021/ja0351847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Murakami H, Hohsaka T, Ashizuka Y, Hashimoto K, Sisido M. Biomacromolecules. 2000;1:118. doi: 10.1021/bm990012g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Alfonta L, Zhang Z, Uryu S, Loo JA, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14662. doi: 10.1021/ja038242x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shinohara H, Kusaka T, Yokota E, Monden R, Sisido M. Sens. Actuators B. 2000;65:144. [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Lemke EA, Summerer D, Geierstanger BH, Brittain SM, Schultz PG. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:769. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bose M, Groff D, Xie J, Brustad E, Schultz PG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:388. doi: 10.1021/ja055467u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hino N, Okazaki Y, Kobayashi T, Hayashi A, Sakamoto K, Yokohama S. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:201. doi: 10.1038/nmeth739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rothman DM, Vázquez ME, Vogel EM, Imperiali B. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2865. doi: 10.1021/ol0262587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Wang W, Takimoto JK, Louie GV, Baiga TJ, Noel JP, Lee KF, Slesinger PA, Wang L. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1063. doi: 10.1038/nn1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kiick KL, Saxon E, Tirrell DA, Bertozzi CR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:19. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012583299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(a) Cellitti SE, Jones DH, Lagpacan L, Hao X, Zhang Q, Hu H, Brittain SM, Brinker A, Caldwell J, Bursulaya B, Spraggon G, Brock A, Ryu Y, Uno T, Schultz PG, Geierstanger BH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9268. doi: 10.1021/ja801602q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Reid PJ, Loftus C, Beeson CC. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2441. doi: 10.1021/bi0202676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Zanuy D, Ballano G, Jiménez AI, Casanovas J, Haspel N, Cativiela C, Curcó D, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009;49:1623. doi: 10.1021/ci9001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cejas MA, Kinney WA, Chen C, Vinter JG, Almond HR, Jr, Balss KM, Maryanoff CA, Schmidt U, Breslav M, Mahan A, Lacy E, Maryanoff BE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:8513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800291105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zanuy D, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:3236. doi: 10.1021/jp065025k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang ZM, Liang GL, Ma ML, Gao Y, Xu B. Small. 2007;3:558. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Crisma M, Toniolo C, Royo S, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C. Org. Lett. 2006;8:6091. doi: 10.1021/ol062600u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Behanna HA, Donners JJJM, Gordon AC, Stupp SI. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1193. doi: 10.1021/ja044863u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Brea RJ, Amorín M, Castedo L, Granja JR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:5710. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Hartgerink JD. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2004;8:604. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Science. 2001;294:1684. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Clark TD, Buehler LK, Ghadiri MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:651. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Lee M-R, Stahl SS, Gellman SH, Masters KS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16779. doi: 10.1021/ja9050636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Connor RE, Tirrell DA. Polym. Rev. 2007;47:9. [Google Scholar]; (c) Börner HG, Schlaad H. Soft Matter. 2007;3:394. doi: 10.1039/b615985k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tu RS, Tirrell M. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56:1537. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kirshenbaum K, Zuckermann RN, Dill KA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1999;9:530. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kirshenbaum K, Barron AE, Goldsmith RA, Armand P, Bradley EK, Truong KTV, Dill KA, Cohen FE, Zuckermann RN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:4303. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Wang X, Huq I, Rana TM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6444. [Google Scholar]; (h) Yoshikawa E, Fournier MJ, Mason TL, Tirrell DA. Macromolecules. 1994;27:5471. [Google Scholar]; (i) Cho CY, Moran EJ, Cherry SR, Stephans JC, Fodor SPA, Adams CL, Sundaram A, Jacobs JW, Schultz PG. Science. 1993;261:1303. doi: 10.1126/science.7689747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Perczel A, Angyán JG, Kajtar M, Viviani W, Rivail J-L, Marcoccia J-F, Csizmadia IG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:6256. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hudáky I, Kiss R, Perczel A. J. Mol. Struct. 2004;675:177. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen FH. Acta Crystallogr. B. 2002;58:380. doi: 10.1107/s0108768102003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. Nucl. Acids Res. 2000;28:235. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sussman JL, Lin D, Jiang J, Manning NO, Prilusky J, Ritter O, Abola EE. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1998;54:1078. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998009378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen PP-S. ACM Trans. Database Syst. 1976;1:9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayle RA, Milner-White EJ. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1995;20:374. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Toniolo C, Formaggio F, Kaptein B, Broxterman QB. Synlett. 2006:1295. [Google Scholar]; (b) Venkatraman J, Shankaramma SC, Balaram P. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3131. doi: 10.1021/cr000053z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C. Biopolymers (Pept. Sci.) 2001;60:396. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:6<396::AID-BIP10184>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alemán C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1997;101:5046. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alemán C, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Pérez JJ, Casanovas J. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2002;106:11849. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casanovas J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Pérez JJ, Alemán C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:5762. doi: 10.1021/jp0542569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Casanovas J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Pérez JJ, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7088. doi: 10.1021/jo034720a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casanovas J, Zanuy D, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:2174. doi: 10.1021/jo0624905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casanovas J, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:4205. doi: 10.1021/jo8005528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casanovas J, Zanuy D, Nussinov R, Alemán C. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006;429:558. doi: 10.1021/jp062804s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alemán C, Zanuy D, Casanovas J, Cativiela C, Nussinov R. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:21264. doi: 10.1021/jp062804s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aschi M, Lucente G, Mazza F, Mollica A, Morera E, Nalli M, Paradisi MP. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2003;1:1980. doi: 10.1039/b212247b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casanovas J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:644. doi: 10.1021/jo702107s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Revilla-López G, Torras J, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:2403. doi: 10.1021/jo802704h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rodríguez-Ropero F, Zanuy D, Casanovas J, Nussinov R, Alemán C. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008;48:333. doi: 10.1021/ci700291x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alemán C, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Nussinov R, Casanovas J. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:7834. doi: 10.1021/jo901594e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Amore M, Improta R, Barone V. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:6264. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cordomí A, Gomez-Catalan J, Jimenez AI, Cativiela C, Perez JJ. J. Pept. Sci. 2002;8:253. doi: 10.1002/psc.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores-Ortega A, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Nussinov R, Alemán C, Casanovas J. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3418. doi: 10.1021/jo702710x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bisetty K, Gomez-Catalan J, Alemán C, Giralt E, Kruger HG, Perez JJ. J. Pept. Sci. 2004;10:274. doi: 10.1002/psc.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bisetty K, Govender P, Kruger HG. Biopolymers. 2006;81:339. doi: 10.1002/bip.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornell WD, Gould IR, Kollman PA. J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem) 1997;392:101. [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Meijere A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1979;18:809. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toniolo C, Crisma M, Formaggio F, Peggion C, Broxterman Q, Kaptein B. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2005;51:121. [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Bodnar RJ. Peptides. 2009;30:2432. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) McLaughlin PJ. Proenkephalin-Derived Opioid Peptides. In: Kastin AJ, editor. Handbook of Biologically Active Peptides. London: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 1313–1318. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hughes J, Smith TW, Kosterlitz HW, Fothergill LA, Morgan BA, Morris HR. Nature. 1975;258:577. doi: 10.1038/258577a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.(a) Cai X, Dass C. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:1. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Graham WH, Carter ES, II, Hicks RP. Biopolymers. 1992;32:1755. doi: 10.1002/bip.360321216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Griffin JF, Langs DA, Smith GD, Blundell TL, Tickle IJ, Bedarkar S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1986;83:3272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Higashijima T, Kobayashi J, Nagai U, Miyazawa T. Eur. J. Biochem. 1979;97:43. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Spirtes MA, Schwartz RW, Mattice WL, Coy DH. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1978;81:602. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Khaled MA, Long MM, Thompson WD, Bradley RJ, Brown GB, Urry DW. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1977;76:224. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(77)90715-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.(a) Koca J, Carlsen HJ. J. Mol. Struct. 1995;337:17. [Google Scholar]; (b) Perez JJ, Loew GH, Villar HO. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1992;44:263. [Google Scholar]

- 44.(a) Hansmann UHE, Okamoto Y, Onuchic JN. Proteins. 1999;34:472. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990301)34:4<472::aid-prot7>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li Z, Scheraga HA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:6611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanbonmatsu KY, García AE. Proteins. 2002;46:225. doi: 10.1002/prot.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marcotte I, Separovic F, Auger M, Gagné SM. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1587. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74226-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, Villa E, Chipot C, Skeel RD, Kale L, Schulten K. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Crisma M, De Borggraeve WM, Peggion C, Formaggio F, Royo S, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Toniolo C. Chem. Eur. J. 2006;12:251. doi: 10.1002/chem.200500865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Royo S, De Borggraeve WM, Peggion C, Formaggio F, Crisma M, Jiménez AI, Cativiela C, Toniolo C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2036. doi: 10.1021/ja043116u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179. [Google Scholar]