Abstract

HIV and AIDS, in resource-limited settings, contribute to increased maternal and infant mortality where such vital indicators are already high. In these settings, babies born to HIV-positive women continue to have added risks of acquiring HIV infection and dying from it before their fifth birthdays if no interventions are employed. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) is an international initiative whose implications within the local context need to be known. An operational research approach was adopted to study the demand and adherence of key components within the PMTCT Programme among women in rural Malawi. This study was carried out at Malamulo SDA Hospital in rural Malawi and employed the mixture of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. While the introduction of innovative policies in antenatal care (ANC) that has positive impact particularly on marginalised women's access to the services, negative effects are also inevitable. Marginalised women in resource-poor settings fail to deliver at the health facility due to lack of transportation, economic difficulties, gender inequalities, tradition and negative attitude of health workers. Integration of HIV testing and opt-out testing in ANC coupled with the introduction of free maternal care resulted in more women accessing maternal services and PMTCT services. It is as a result of this that institutional delivery facilitates increased adherence to antiretroviral prophylaxis and is supported by both women and the communities. The paper summarises the research conducted and elaborates on how it contributed to actions to improve staff attitude, increase male involvement in reproductive health care and discussions on how available resources can be maximised.

Keywords: HIV and AIDS, PMTCT, policies, antenatal care, rural Malawi

HIV and AIDS have caused untold harm and human suffering globally. Over 90% of people infected with this deadly virus live in sub-Saharan Africa including Malawi. In Malawi, the prevalence of HIV among the childbearing age group (15–49) is estimated to be at 14% and close to a million people have already died of AIDS-related conditions (1). Women and children are more affected than the rest of the general population. HIV infection in children below 15 years is largely due to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT). Worldwide, over two million children have been infected through MTCT (2).

The high prevalence of HIV among the women is contributed from multiple factors. The factors that are responsible for the proliferation of HIV and AIDS in these women include tradition, gender inequalities, biological make up, inadequate coverage of health care in some areas, distance, failure of women to negotiate on matters regarding sex and poverty among others. It is estimated that 18% of the pregnant women in Malawi are infected with HIV and this prevalence is relatively high in urban areas as it ranges from 19 to 30% (1). As a result of this, MTCT of HIV becomes an area of concern and calls for the prevention of MTCT (PMTCT) of HIV.

PMTCT was first introduced in 2001 into the ANC as an international initiative and then was adopted by different countries in Africa (3, 4). The primary aim of the PMTCT programme, as put in the guidelines, was to decrease the number of HIV-infected babies born to HIV-positive mothers. Primary prevention of HIV infection, particularly among women of childbearing age, has always been the backbone of the programme. It is believed that without intervention, up to 50% of babies born from HIV-positive women get infected through labour, delivery and breast feeding. A number of interventions have been aimed at limiting the risk of newborn infections during delivery, such as caesarian section as the mode of delivery and administering antiretroviral (ARV) drugs prepartum and peripartum and providing alternatives to breast feeding. However, all these approaches are not always possible in developing countries and the relative importance of ARV drugs, in particular nevirapine (NVP), has been investigated (5, 6).

HIV testing starting with ‘opt-in’ strategy was introduced in PMTCT programmes in 2001 following international initiatives, with efforts to reduce MTCT. Opt-in strategy is an approach whereby all clients are encouraged to undergo voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) at their own will (7). Later, opt-out strategy was adopted by many countries in sub-Saharan Africa (8). The aim was to enable all pregnant women to be screened for HIV infection. Screening should occur after a woman is notified that HIV screening is recommended for all pregnant women and that she will receive an HIV test as part of the routine panel of prenatal tests unless she declines (opt-out screening) (9).

PMTCT programmes adopted different policies to ensure successful intervention of the programmes. In 2002, the MTCT-plus Initiative was established, which aimed to move beyond interventions to prevent infant HIV infection. It does this by supporting the provision of specialised care to HIV-infected women, their partners and their children who are identified in MTCT programmes (10, 11).

Much attention has been given to the ARV prophylaxis in developing countries. Commonly a single dose of NVP 200 mg administered to a woman at the onset of labour and a similar drug, but in syrup form given to the child within 72 h after delivery reduces infection by 38–50% (12). The single use of NVP as prophylaxis in PMTCT has been recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and widely adopted by many resource-poor countries particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa. The common availability of NVP and its simplicity in administration including the fact that it is cheap with fewer side effects make it acceptable, accessible and affordable in resource-poor settings. However, the single use of NVP as prophylaxis in PMTCT programmes has been associated with the development of resistance at some stages in the lives of women who eventually receive ARV treatment (13). It is for this reason that a combined regimen has been adopted; although at the time of conducting the study, only NVP was being used in PMTCT.

Prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) at Malamulo

Malamulo PMTCT programme was started in July 2004 as part of a national initiative to protect more HIV-positive pregnant women from transmitting HIV to their babies. With a catchment population of 70,000, it was observed that more pregnant women who came to Malamulo hospital for the antenatal care (ANC) tested HIV-positive and this was the same at the national level. As a Christian Health Association of Malawi (CHAM) unit, Malamulo hospital is supported by Malawi Government's Ministry of Health through CHAM like any other faith-based health facility in Malawi. Malamulo hospital is owned by the Seventh Day Adventist Church.

Fig. 1.

PMTCT beneficiaries.

Both curative and preventive services are offered by this hospital and the integrated approach is used to run the preventive services. The services include: VCT and synonymously called HIV testing and counselling (HTC); management of sexually transmitted infections (STIs); home-based care (HBC); youth-friendly health services (YFHS); family planning (FP); PMTCT of HIV; provision of ARVs, nutrition, static and outreach mother and child health (MCH) services. Over the study period, the project was largely funded by USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development) through local and international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) called Umoyo Network and later Private Agencies Collaborating Together (PACT Malawi), respectively, among other donors.

At that time Malamulo hospital HIV-testing services adopted an opt-in approach whereby women accessed HIV testing after receiving information if they wished to do so. The HIV testing was done at one central point and this was in the out-patient department (OPD). Therefore, women in the ANC were routinely referred to OPD for HIV testing after accessing all the necessary ANC. However, it was observed that not all antenatal women accessed HIV testing in the OPD regardless of being referred to the services and many were lost in the process. It was due to this that HIV testing was integrated in the ANC as a local initiative so as to capture more women in March 2005.

In January 2006, opt-out (routine) HIV testing was started and by this approach, more antenatal women accessed HIV testing in the same way they accessed other routine antenatal investigations and consequently joined the PMTCT programme. Unfortunately, maternal services at that time were payable, so much as more antenatal women accessed HIV testing and joined PMTCT programme, quite a small proportion of them completed full ANC and delivered in the hospital.

In October 2006, free maternal care was introduced at Malamulo also as a national initiative to capture and help more marginalised women access maternal care and consequently reduce preventable maternal and infant mortality.

It is only Malamulo hospital that offers a comprehensive PMTCT package in the catchment area. All antenatal women who test HIV-positive are routinely registered into the PMTCT programme. These HIV-positive women are then subjected to the prescribed PMTCT package and this comprises of the following: provision of ARV prophylaxis (NVP) with advice to be taken at the onset of labour and the child to get the same drug in syrup form within 72 h after delivery, to access hospital delivery and to exclusively breast feed the child for 6 months. The consequences of home delivery as well as hospital delivery in relation to the PMTCT programme are explained to these women to understand why it is important for them to make informed choices. If eligible, the woman is provided with long-term ARV treatment. There is also provision of supplementary feeds to the women and their infants when necessary, provision of cotrimoxazole to the infants as prophylaxis.

Further, these women are encouraged to come with their husbands so that they can access HIV testing as couples. After delivery, women and their infants are followed up to 18 months when babies’ HIV status is determined. HIV-negative babies at 18 months are discharged from the PMTCT programme and the HIV-positive ones are then subjected to comprehensive care and investigations such as CD4 counts, haemoglobin and continuous provision of cotrimoxazole as prophylaxis for chest infections and depending on the levels of CD4 counts, these infants are put on long-term general ARV treatment.

Why operational research?

The overall aim of the study was to analyse the demand and adherence to key components of the PMTCT programme.

A good number of researche s continue to be done in various fields but much of their applicability remains questionable and, if anything, they end up on bookshelves and an award of academic credentials thereof. This study took a different direction all together in that not only did it suffice the requirements but also paved a way to improve the reality on the ground. It is as a result of this that positive consequences of service delivery regarding its acceptability, accessibility, as well as affordability, by the marginalised rural communities have been explored.

The conducted research in a nutshell

This study employed a mixture of both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Data sources included ANC, PMTCT and delivery registers, structured questionnaires, in-depth interviews with HIV-positive women in the programme and focus group discussions with community members, health care workers and traditional birth attendants.

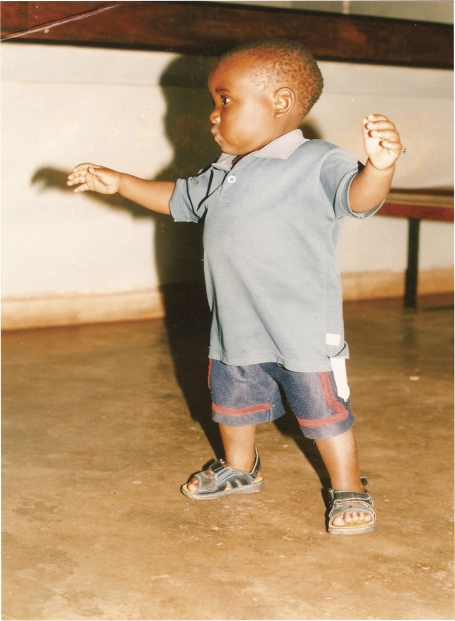

Fig. 2.

PMTCT beneficiary at 18 months.

Three interventions were introduced in the ANC at the hospital at different times. These were HIV testing integrated in the ANC clinic in March 2005, opt-out testing in January 2006 and free maternal services in October 2006. A steady increase of the service uptake as interventions were being introduced was observed over time. HIV testing was generally accepted by the community and women within the programme. However, positive HIV tests among pregnant women were also experienced to cause conflicts and fear within the family. Although hospital deliveries were recognised to be safe and clean, home deliveries were common. Lack of transport, spouse support and negative attitudes among staff were some of the underlying factors (14).

Research-triggered actions

As a result of this study, the following consequences were arrived at: ever since PMTCT programme got started at Malamulo hospital, very few marginalised women actually accessed hospital delivery services despite attending ANC due to financial constraints. Coincidentally, with long-standing lobbying with Malawi Government through its Ministry of Health and district health office (DHO), free maternal care was introduced in October 2006. Good proportions of women in general as well as those in the PMTCT programme now do access maternity care. This has also beefed up the uptake of HIV testing, ARV prophylaxis for the HIV-positive women and their infants as well as access to general long-term ARV treatment. This has created an opportunity to scale up the programme and improve the quality of care given as has been commented by other authors (15). It is clear that apart from financial constraint as a barrier, there are also other challenges that prevent women from accessing the services at the hospital.

Negative attitude of health workers was observed as one of the barriers that prevent women from accessing maternity care. Pregnant women in delivery suits would like to be treated as human beings with respect and dignity, an observation that was echoed as missing among some of the midwives at the health facility's labour ward. The same women preferred home delivery with the assistance of traditional birth attendants to hospital delivery due to the warm reception the traditional birth attendants accord them. Previous successful home delivery experiences, provision of warm bath, porridge, respect and dignity to the women before and after delivery were said to be some of the motivating factors for the women to continue having home deliveries. After debriefing the study findings to the management, strategies were developed to improve on this. All the health workers were involved and issues such as increased workload, less experience in labour ward and tradition among other factors, were named as contributing factors to the negative attitude of health care staff. In response to this the management came up with the following strategies:

Suggestion box was put in maternity ward for the women and interested parties to put in their aspirations. These suggestion boxes are reviewed monthly to respond to the issues as they arise.

Monthly and yearly ward performance competitions began so that the best ward receives an award as a token of appreciation. There is a committee that has been set up to handle this activity.

Best health worker of the year for each department and should receive awards.

General staff meetings organised by the management through the human resources' office to handle personnel issues including staff attitude to patients in general. In such meetings people expressed their opinions and what ought to be done to improve the situation. Also staffing issues in such meetings were being tackled as health workers expressed concern that they were understaffed.

The matron's office took an active role in seeing to it that nurses and midwives performed their duties in accordance with their profession and routine meetings were held relating to this.

Minimal male involvement in reproductive health care was as well long observed right at the inception of the programme. This observation was contrary to the fact that men in this study decided for their wives where to access maternal care. It is important to note that traditional tendencies in the study area are enshrined in paternalistic approaches; as such whatever men decide is firmly held by the general communities, particularly women. From the time immemorial until the turn of the century, it has been very uncommon to see men participating actively in the reproductive health services or rather MCH services in general. This has for a long time disadvantaged not only women and the children but also men themselves resulting in poor understanding and acceptability of different health issues and family break ups particularly when health matters in question require both couples to take actions.

Based on the study findings, the hospital management through the community medicine department developed the following strategies to positively address this challenge:

Women in the ANC to be encouraged to come with their spouses to PMTCT and ANC services in general and to participate in what is called ‘couple counselling’ before and after undergoing HIV testing.

Men to be encouraged to come with under five children to the health facility for screening, immunisation, growth monitoring just as women routinely do.

If a man comes alone to the health facility with a sick child or joins his wife to access ANC he ought not to be in the queues.

Males may be encouraged to accompany their wives to the labour ward to see and support their wives as they undergo delivery experiences. This is optional as this issue is culturally sensitive and few men wish to participate in this way.

To enforce this, routine meetings with men and women, village headmen and faith-based leaders continue to be conducted in the communities. In addition, the DHO, various NGOs and funding agencies including USAID through Private Agencies Collaborating Together (PACT Malawi), which funded the activities in the study area, supported the male involvement initiative. However, it is encouraging to note that currently, over 10% of women who come to the health facility are now being accompanied by their husbands, a move that was not there before.

The provision of ARV prophylaxis (NVP) that was given to the women in the PMTCT programme at 32 weeks and above is now given at the first contact with the woman during the ANC. It was observed that when NVP was being given in late pregnancy, there were lots of missing opportunities as some women could deliver at home or on the way to the hospital before accessing the ARV prophylaxis. This as well resulted in babies not accessing NVP as per the PMTCT programme protocol. Therefore, early administration of ARV prophylaxis to women in the PMTCT programme has improved the accessibility of the services.

The study further explored the opportunities of maximising the various resources at different levels; namely, health workers at facility and health surveillance assistants (HSAs) from the DHO who work both at the health facility as well as at the community levels. In addition opinion leaders such as village headmen, faith-based leaders and community volunteers at community levels were some of the resources that were utilised and provided a way of possible decentralisation of the services so as to widely reach a good proportion of the population within the studied facility's catchment area.

The involvement of TBAs in maternity care has always been a contentious issue although their home delivery services cannot be completely ruled out. There are trained TBAs in the area who conduct normal deliveries with minimal or no complications, but there has been a thin line between those who can afford to refer some of the cases they cannot manage and those who cannot as well. It has also been not clear to establish the number of women who deliver at the home of trained and untrained TBAs as some of the TBAs do conduct their services in secrecy. Although the Malawi Government recognises their participation in maternal health but it is clear that their services can be potentially harmful to some of the women particularly those at risk. It is as a result of this that official home delivery with the assistance of the TBAs is being discouraged and this calls for all women to access maternal care at the health facility.

Conclusions and recommendations

Based on the study findings, the following were concluded and recommended; increased accessibility and utilisation of maternity care can, as well, potentially increase the coverage of PMTCT services. Free maternity care partly removes the economic constraints that prevent marginalised women from accessing the services. Similarly, the integration of services into ANC increased the women's uptake of HIV testing and hospital delivery influenced women's adherence to ARV prophylaxis (NVP). Both women as well as the community in general supported institutional delivery. Further, by encouraging hospital delivery and male involvement, more PMTCT women are likely to adhere to the PMTCT programme and consequently reduce MTCT of HIV.

Further studies on the quality of care offered in the presence of increased service uptake, estimation of true programme coverage and effectiveness are required. Policy makers as well as potential donors need to come up with interventions that have positive effects for the disadvantaged communities. Operational research provides an opportunity for health care institutions to optimise the local implementation of programmes like PMTCT. The provision of such research skills should be encouraged by MOHP and donor organisations. Service providers at facility and community levels, policy makers at all levels, all stakeholders and the communities should see themselves as partners in development and should work together to reduce preventable maternal and infant mortality including MTCT of HIV.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express the sincere and the profound thanks to the Swedish Institute, Sweden and the Centre for the Global health, Umeå University, Sweden supported by FAS the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (Grant No. 2006-1512) for the financial support to make this study possible. I again, thank the Malamulo hospital management and staff for their support in kind to make this study a possibility.

Conflict of interest and funding

The author conducted this study with support from the Swedish Institute, Sweden; Department of Clinical Medicine and Public Health, Epidemiology and Global Health, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden and Malamulo SDA Hospital, Makwasa, Malawi.

References

- 1.MDHS. Zomba: National Statistics Office, Demographic and Social Statistics Division; 2004. Malawi demographic health survey, HIV/AIDS prevalence. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS/WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS/WHO; 2008. Epidemiological fact sheet on HIV and AIDS in Malawi.Core data on epidemiology and response. [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants in resource-limited settings: towards universal access. 2006. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/pmtct/en/index.html [cited 20 March 2010]

- 4.Druce N, Nolan A. Seizing the big missed opportunity: linking HIV and maternity care services in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:190–201. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(07)30337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan JL. Prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV – what next? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003;34:S567–72. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200309011-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volmink J, Siegfried N, van der Merwe L, Brocklehurst P. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858. CD003510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez F, Zvandaziva C, Engelsmann B, Dabis F. Acceptability of routine HIV testing (“opt-out”) in antenatal services in two rural districts of Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41:514–20. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000191285.70331.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.CDC. Introduction of routine HIV testing in prenatal care-Botswana. MMWR. 2006;53:1083–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajunirwe F, Muzoora M. Barriers to the implementation of programs for the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: a cross sectional survey in rural and urban Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2005;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. HIV and infant feeding: guidelines for decision makers. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iliff PJ, Piwoz EG, Tavengwa NV, Zunguza CD, Marinda ET, Nathoo KJ, et al. Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-free survival. AIDS. 2005;19:699–708. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166093.16446.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scarlatti G. Mother to child transmission of HIV-1: advances and controversies of the twentieth centuries. AIDS Rev. 2004;6:67–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lallemant M, Jourdain G, Le Coeur S, Mary JY, Ngo-Giang-Huong N, Koetsawang S, et al. Perinatal HIV prevention trial (Thailand) investigators, single dose perinatal nevirapine plus standard zidovudine to prevent mother to child transmission of HIV-1 in Thailand. N Engl J Med. 2004;251:217–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasenga F, Hurtig A-K, Emmelin M. Community perceptions of a PMTCT programme in Malawi. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2009;3:42–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pai NP, Klein MB. Rapid testing at labour and delivery to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in developing settings: issues and challenges. Women Health (Lond) 2009;5:55–62. doi: 10.2217/17455057.5.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]