Abstract

The pleiotropic cytokine interferon alpha is involved in multiple aspects of lupus etiology and pathogenesis. Interferon alpha is important under normal circumstances for antiviral responses and immune activation. However, heightened levels of serum interferon alpha and expression of interferon response genes are common in lupus patients. Lupus-associated autoantibodies can drive the production of interferon alpha and heightened levels of interferon interfere with immune regulation. Several genes in the pathways leading to interferon production or signaling are associated with risk for lupus. Clinical and cellular manifestations of excess interferon alpha in lupus combined with the genetic risk factors associated with interferon make this cytokine a rare bridge between genetic risk and phenotypic effects. Interferon alpha influences the clinical picture of lupus and may represent a therapeutic target. This paper provides an overview of the cellular, genetic, and clinical aspects of interferon alpha in lupus.

1. Introduction

In systemic lupus erythematosus, a finely tuned system of cells and signals is dysregulated, and the balance between tolerance and autoimmunity is disrupted. Cytokines, as a fundamental mechanism through which the immune system is kept in balance, play an important role in the etiology and pathogenesis of lupus. An example of an important cytokine involved in lupus etiology and pathogenesis is interferon alpha (IFNα).

IFNα is a pleiotropic cytokine that can affect multiple cell types involved in lupus. Several genes in the interferon pathway are associated with risk for lupus, suggesting a role for this pathway in etiology. Additionally, increased IFNα levels and expression of IFN response genes are often found in lupus. IFNα may affect the clinical manifestations of lupus and is a promising target for therapeutic interventions.

2. Cellular Aspects of IFNα in Lupus

Interferon alpha (IFNα) is a key molecule in immune regulation. It is produced by multiple cell types in response to viral infection. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells have a special role in the production of IFNα and are the main sources of serum interferon [1]. IFNα has the potential to dramatically influence the development, progression, and pathogenesis of SLE as it can influence the function and activation state of most major immune cell subsets and function as a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity.

2.1. Toll-Like Receptors and Interferon

One of the principal mechanisms through which IFNα is produced is through Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling [2, 3]. TLR7 recognizes single-stranded RNA, culminating in interferon regulatory factor (IRF) 5 and IRF7 activation [4] and production of IFN [5–7]. Excessive TLR 7 signaling produces lupus-like autoimmunity in male Yaa mice, where an extra copy of the TLR7 gene is present on the Y chromosome [8–10]. The autoimmune phenotype conferred by the Yaa genotype is dependent on IFN α, and addition of IFNα can partially duplicate the Yaa phenotype [11]. Additionally, knocking out the IRF7 gene or inhibiting its action with pharmacologic agents inhibits antibody production against RNA-containing nuclear components [12], suggesting that TLR7 is essential for this type of autoantibody production.

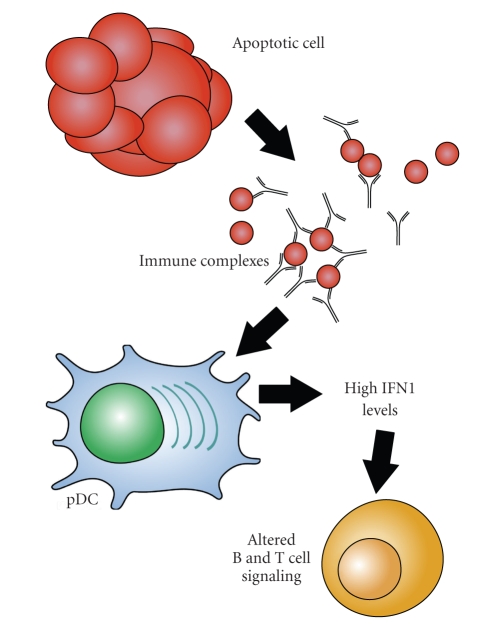

A characteristic of many cases of lupus is the production of antibodies against RNA-containing protein complexes such as Sm, nRNP, Ro, and La. In fact, antibodies against the spliceosomal protein Sm are so specific for lupus that they are used as a diagnostic criterion. The RNA found in these complexes is capable of promoting the production of IFNα through the stimulation of TLR7 [3, 13] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Putative source and effects of interferon alpha in lupus. RNA-containing complexes from apoptotic cells are bound by autoantibodies. These immune complexes are internalized after binding to FC receptors on plasmacytoid dendritic cells and stimulate toll-like receptors in the endosomes. Toll-like receptor ligation drives production of interferon alpha, leading to alteration of T-cell profiles, disruption of regulatory T-cell networks, and alteration of B-cell development.

Because TLR7 is located in the endosomes, RNA-containing complexes must access the interior of the cell before they are able to act as activators. Autoantibodies specific for these lupus-associated riboproteins can bind with antigens derived from apoptotic cells and form antibody-protein-RNA complexes. The Fc portions of the immune complexes are recognized and internalized by cells with Fc receptors, providing a route of entry for RNA to reach TLR7, resulting in interferon alpha production [3, 14]. This process is especially well established in PDCs [15, 16]. Interestingly, in addition to being produced as a result of TLR7 ligation, IFNα enhances TLR7 signaling in PDCs [17, 18], forming a positive feedback loop.

Despite these data and the strong association between SLE-associated autoantibodies and serum IFNα, SLE-associated autoantibodies are not sufficient for high serum IFNα in humans in vivo [19]. Healthy subjects with anti-Ro antibodies do not have high serum IFN-α, while a significant proportion of anti-Ro positive patients with SLE or Sjogren's syndrome do have high serum IFNα, suggesting that these autoantibodies require other disease-associated factors to result in high serum IFNα in humans.

2.2. IFNα and Adaptive Immune Regulation

Excess serum IFNα and IFN-response gene expression are characteristics of lupus and are most likely the result of excessive PDC activation. Such high levels of interferon could contribute to lupus by promoting immune activation rather than tolerance. Dendritic cells are the primary activators of T cells, and affect both T-cell tolerance and activation, depending on the state of the dendritic cell. When treated with interferon alpha, dendritic cells mature and become more prone to activate T cells [20, 21]. Myeloid dendritic cells from lupus patients are able to phagocytose and present self-antigens to T cells in a stimulatory, rather than regulatory manner, a process which is interferon-dependent [22]. Such a process likely contributes to loss of T-cell tolerance to self-antigens and subsequent autoimmunity.

Exposure of the dendritic cell to IFNα contributes to T cell polarity. When CD4+ T cells are activated in the presence of IFNα-producing dendritic cells, their polarity is shifted towards IFN-γ producing cells rather than IL-4 producing cells [23, 24], which may promote autoimmunity or immune dysregulation. The T-cells activated by IFNα-treated dendritic cells also are enriched for T-follicular helper cells, a recently described cell type which are adept at activating B cells and driving antibody production [25].

Regulatory T cells (T-reg) are attracting increased attention as a mechanism of immune regulation and suppression of autoimmunity. In lupus, T-regs are often, though not always, found in lower numbers than in controls [26–31]. Those T-regs that are present in lupus are inefficient at suppressing inflammation and T-cell proliferation [27, 29, 30, 32]. T-reg development is suppressed by treatment of dendritic cells with IFNα [33]. In lupus patients, T-reg activity is diminished, due at least in part to the action of IFNα [34] indicating that increased IFNα levels in lupus patients is likely contributing to the development or maintenance of autoimmunity through suppression of T-reg cells.

B cells are important in lupus, since humoral autoimmunity is a hallmark of the disease. IFNα can prevent apoptosis and enhance proliferation of primary B cells, even in the absence of mitogenic stimuli [35]. Interestingly, isolated B cells are inhibited from developing into antibody-producing plasma cells by IFNα treatment [36]. However, this inhibition is reversed if the B cells are allowed to come into contact with monocytes, in which case IFNα actually stimulates B-cell development and antibody production [37].

The ability of IFNα to influence the activation and function of many major immune cell subsets is a testament to the wide and far-reaching effects of this cytokine. It is clear that interferon is dysregulated in lupus and that overexpression of IFNα can result from the autoantibodies present in lupus. Many components of the molecular pathways through which IFNα and TLRs drive immune activation include genetic risk factors for lupus, further implicating IFNα in lupus etiology and pathogenesis.

3. IFN and IFN-Related Genes Associated with SLE Risk

Lupus involves a combination of both environmental and genetic factors. Support for a genetic component includes a high sibling risk ratio [8–29], high heritability (greater than 66%), and higher concordance rates between monozygotic twins (20 to 40%) as compared to other full siblings and dizygotic twins (2 to 5%) [38, 39]. A large number of genetic risk factors are associated with increased susceptibility to the SLE. This genetically determined increased risk status has been referred to as a “threshold liability” [40], which is expected to be highly polygenic in nature and widely variable between individuals. Environmental factors also affect lupus susceptibility and likely interact with this “threshold liability”, but as in the case of genetic factors, there is no single environmental cause. A person may have only a few of the genetic risk variations and never get SLE despite exposure to environmental triggers. In contrast, another person may have many of these variations and then develop SLE on first exposure to an environmental trigger.

3.1. Lupus-Associated Risk Loci

Research into the etiopathogenesis of SLE has recently been advanced by several large scale case-control genetic studies, including genome-wide association scans. There is now a pool of approximately 30 genes that have been associated with SLE susceptibility with a high degree of statistical certainty and many others with probable evidence for association (reviewed in [41–45]). With this large number of SLE-associated genes, we can begin to group the list of identified SLE associated genes which should provide insight into initial disease pathogenesis into functional categories. These categories include TLR and IFN signaling, apoptosis and clearance of immune complexes, and B- and T-cell signaling. Several genes affecting the interferon pathway have been associated with risk for lupus. The Interferon pathway normally serves an important function in defense against viral infection. Yet in people with genetic predisposition, environmental triggers such as viral infections may tip the scales in favor of autoimmunity.

Once a genetic variation is identified, functional inference then characterization is necessary to move from identification to an understanding of how the variation affects the etiology or pathogenesis of SLE. Since most of the genes involved in genetic susceptibility to SLE have been identified only recently, there remains much work to identify the functional differences in the genetic associations. However, work done thus far in human cohorts is promising, and the categories of genes and loci associated with risk of lupus already suggest pathways that are of high importance.

3.2. Interferon Regulatory Factors

Certain lupus-associated genetic variations have been shown to directly increase IFNα levels or response to IFNα signaling. Interferon regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) has been confirmed as a risk locus in several different ethnic groups [46–50]. Three main functional variants in IRF5 have been described, which combine to form a risk haplotype in individuals of European descent [51]. One of these loci, at rs2004640, creates an alternate splice site (exon 1B) in the untranslated first exon. Another is a copy number variation of a 30-bp insertion/deletion sequence in exon 6, and the final is rs10954213, which creates an alternate polyadenylation site, resulting in shorter, stabler mRNA [52].

Since IRF5 activates IFNα production, these more stable variants may pose a risk due to their ability to produce excess IFNα. In fact, studies of this gene in human SLE cohorts have shown that the risk variant predisposes to greater serum IFN-α, supporting the idea that the risk haplotype is a gain-of-function variant [53]. IRF5 itself is activated by IFNα signaling, producing a potential positive feedback loop. Another IRF, IRF7, has been highlighted by the association of the IRF7/KIAA1542 locus with lupus in recent studies [54, 55]. Several SNPs in this area were shown to correlate with IFNα levels and alter autoantibody profiles in certain ethnicities [56].

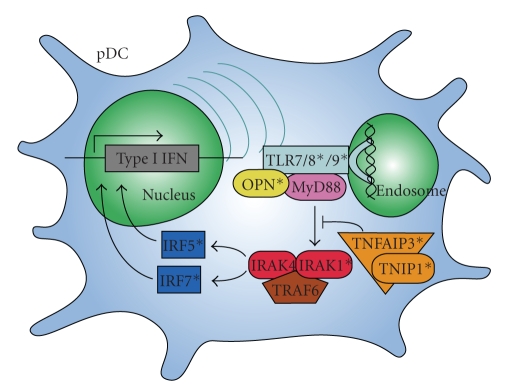

IRF5 and IRF7 are activated by signaling through the endosomal toll-like receptors (TLRs) 7, 8, and 9. Interestingly, both of the IRF variants which are implicated in SLE predispose to higher serum IFN-α, but only in the presence of SLE-associated autoantibodies [53, 56] suggesting that these autoantibodies may provide chronic stimulation of the endosomal TLR pathway of IFN-α generation that when combined with gain-of-function polymorphisms in the IRFs results in dysregulation of the pathway in vivo. Additionally, TLRs 8 and 9 were identified in recent studies as containing susceptibility loci to SLE [57, 58]. The role of TLRs in the interferon production was discussed above.

3.3. Interferon-Associated Genes

Another confirmed locus of susceptibility is in the gene encoding IL1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1). This kinase is part of the signal transduction which follows TLR ligation. In a mouse model of lupus, IRAK deficiency eliminated most lupus symptoms, showing the importance of this key intermediate [59]. Since this gene is on the X chromosome, gene dosage may contribute to the risk and the prevalence of the disease in women [59].

Two interacting proteins involved in inflammation, TNFα-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3) and TNFAIP3-interacting protein 1 (TNIP1), have been identified as risk loci [60–64]. TNFAIP3 encodes the protein A20, which helps turn off signaling through NFκB after an inflammatory response [65, 66]. TNIP1 interacts with TNFAIP3 and is involved in several signal transduction pathways.

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 (STAT4) is another risk locus with direct links to the interferon pathway. It is involved in proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. STAT4 has 2 risk loci, one at rs7574865 which has been shown to increase sensitivity to IFNα [67], and another at rs3821236 which increases STAT4 transcription and interacts with IRF5 susceptibility loci [68]. The presence of both of these risk alleles gives an additive effect, increasing risk to SLE [69]. Osteopontin (OPN) is a key molecule for IFNα production in pDCs [70]. Presence of a lupus risk-associated form of this gene was recently tied to high IFN levels in males and young-onset female lupus patients [71].

Possible interactions of the IFN-associated genes that have been linked to lupus are shown in Figure 2. The risk variants of these genes influence the production of and response to IFNα, likely driving the increased levels seen in lupus patients and affecting the clinical manifestations of the disease.

Figure 2.

Multiple genes involved in interferon production and regulation are associated with risk for lupus. Shown are components of the signal transduction pathway from TLR stimulation by nucleic acids to IFN production. Genes that have been associated with risk for lupus are marked (*). IFN: interferon, IRAK: interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase, IRF: interferon regulatory factor, MyD88: myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88, OPN: osteopontin, pDC: plasmacytoid dendritic cell, TLR: toll-like receptor, TNFAIP3: tumor necrosis factor alpha induced protein 3, TNIP1: TNFAIP3 interacting protein 1, and TRAF6: tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6.

4. Clinical Aspects of IFNα in Lupus

Lupus primarily affects women in the reproductive years; however people of all ages, genders, and ancestral backgrounds are susceptible. Disease features range from mild manifestations such as rash or arthritis to life-threatening end-organ manifestations such as glomerulonephritis or thrombosis, and it is difficult to predict which manifestations will affect a given patient.

4.1. IFN-α as a Causal Factor in Human Lupus

A number of patients treated with IFNα have developed lupus or lupus-like syndrome [72–74]. In these reports, many specific manifestations of idiopathic lupus such as malar or discoid rash, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, renal involvement, and anti-Sm and anti-dsDNA antibodies were represented, suggesting that these cases were not “drug-induced” SLE but instead resembled idiopathic SLE [73]. Discontinuation of IFNα typically resulted in remission of SLE symptoms [73], supporting a causal relationship with IFN-α. While only a minority of patients treated with IFNα develop SLE (<1% of patients) [75], these data support the idea that IFNα can be sufficient to induce SLE in some individuals. Many more IFNα-treated individuals develop a “lupus-like” syndrome [74], with some SLE symptoms which are insufficient to meet formal diagnostic criteria for SLE [76]. IFN-induced SLE can be severe, and there are reports of life-threatening multiorgan SLE involvement including glomerulonephritis, serositis, discoid rash, myopericarditis, and vasculitis [77, 78].

Another finding which supports the hypothesis of IFNα as a primary causal factor in human SLE is the clustering of high serum IFNα in lupus families [79]. Patients with lupus and their healthy relatives have higher serum IFNα activity as compared to healthy unrelated individuals [79]. Strong familial correlations in serum IFNα were observed regardless of disease status (affecteds versus unaffecteds), and SLE probands in the same family tended to have similar IFNα levels [79]. Spouses of SLE patients did not have high serum IFNα activity, and taken together these data suggest that high serum IFNα is a heritable risk factor for SLE. Interestingly, age-related patterns of serum IFNα were also observed in SLE families in which the ages of highest IFNα mirrored the ages of peak SLE incidence [80, 81]. The discovery of several lupus risk loci in IFN-related genes provides further support for the above observation that serum IFN-α is heritable, and the SLE risk variants of each of these genes result in a gain of function increase in IFNα signaling as detailed above.

4.2. Clinical Correlations with IFN Alpha

A very strong correlation is consistently observed between the presence of SLE-associated autoantibodies, such as anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, and anti-dsDNA [79, 82]. Lupus patients with high serum IFNα had a significantly higher prevalence of cutaneous and renal disease in most studies [82–84]. It is interesting that both of these clinical manifestations share an association with a particular serology (rash with anti-Ro and nephritis with anti-dsDNA), and whether these clinical manifestations are associated independent of serology has not been shown to our knowledge.

A number of studies have shown that IFNα correlates with disease activity when assessed cross sectionally [82–85]. Results are conflicting regarding the potential fluctuation of IFNα with disease activity in SLE, and there are a number of studies which did not find a longitudinal correlation [86, 87]. In these studies, a cross-sectional relationship between IFNα and disease activity is still observed, suggesting that IFNα may indicate those patients who generally have higher disease activity as compared to other patients. A recent prospective study evaluated the utility of serum interferon-regulated chemokine levels as potential biomarkers of SLE disease activity [88]. In this study, IFNα-induced chemokines correlated with disease activity cross sectionally, rose at the time of a flare, and decreased as the disease remitted [88]. In this same study, high chemokine levels were predictive of SLE flare over the next year in a subset of patients.

4.3. Anti-IFNα Therapies in Lupus

Given all of the studies presented above, there has been considerable interest in therapies which block IFNα. To date there is one published study describing a phase I trial of a fully human monoclonal antibody that binds to the majority of the subtypes of human interferon alpha [89]. Treatment with this anti-IFN antibody resulted in a dose-dependent inhibition of interferon-induced gene expression in peripheral blood cells as well as skin lesions in patients with mild to moderate SLE [89]. No obvious safety signals were reported during the phase I trial of anti-IFN therapy, and the proof-of-principle analyses supported a biological effect blocking the IFN pathway in humans. Phase two trials to assess efficacy of these agents in treating SLE are currently underway. There are many known predictors of high serum IFNα in SLE patients, including both serologic and genetic markers outlined in this paper. We anticipate that incorporation of these variables into clinical trial design would enhance efficacy and potentially minimize side effects by targeting the most relevant patient group. Long-term safety data will be important, since IFNα is such a highly conserved and important immunological mediator of viral defense.

5. Conclusions

IFN-α is associated with SLE through multiple lines of evidence. These include genetic, immunological/serological, and clinical associations, as described in this review. It is likely that IFN-α plays a key role in SLE etiology, pathogenesis, and/or disease persistence. Despite this large body of evidence associating IFN-alpha with lupus, the association between interferon alpha and SLE is largely inferential. The exact cellular and immunological mechanisms through which IFN affects lupus also remain undiscovered for the most part. These mechanisms and pathways are potentially fertile areas for future investigation. Such studies will likely lead to new therapeutic targets as well as a greater understanding of lupus as a disease.

References

- 1.Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Dai J, Singh S. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and type I IFN: 50 years of convergent history. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2008;19(1):3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito T, Wang Y-H, Liu Y-J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors/type I interferon-producing cells sense viral infection by Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and TLR9. Springer Seminars in Immunopathology. 2005;26(3):221–229. doi: 10.1007/s00281-004-0180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lövgren T, Eloranta M-L, Kastner B, Wahren-Herlenius M, Alm GV, Rönnblom L. Induction of interferon-alpha by immune complexes or liposomes containing systemic lupus erythematosus autoantigen- and Sjogren’s syndrome autoantigen-associated RNA. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(6):1917–1927. doi: 10.1002/art.21893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenemeyer A, Barnes BJ, Mancl ME, et al. The interferon regulatory factor, IRF5, is a central mediator of toll-like receptor 7 signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(17):17005–17012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412584200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoshino K, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto M, et al. IκB kinase-α is critical for interferon-α production induced by Toll-like receptors 7 and 9. Nature. 2006;440(7086):949–953. doi: 10.1038/nature04641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Sato S, Ishii KJ, et al. Interferon-α induction through Toll-like receptors involves a direct interaction of IRF7 with MyD88 and TRAF6. Nature Immunology. 2004;5(10):1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/ni1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Löseke S, Grage-Griebenow E, Heine H, et al. In vitro-generated viral double-stranded RNA in contrast to polyinosinic: polycytidylic acid induces interferon-α in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2006;63(4):264–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairhurst A-M, Hwang S-H, Wang A, et al. Yaa autoimmune phenotypes are conferred by overexpression of TLR7. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;38(7):1971–1978. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pisitkun P, Deane JA, Difilippantonio MJ, Tarasenko T, Satterthwaite AB, Bolland S. Autoreactive B cell responses to RNA-related antigens due to TLR7 gene duplication. Science. 2006;312(5780):1669–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.1124978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian S, Tus K, Li Q-Z, et al. A Tlr7 translocation accelerates systemic autoimmunity in murine lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(26):9970–9975. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603912103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramanujam M, Kahn P, Huang W, et al. Interferon-α treatment of Female (NZW × BXSB)F1 mice mimics some but not all features associated with the Yaa mutation. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(4):1096–1101. doi: 10.1002/art.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Chan JH, Guiducci C, Coffmann RL. Treatment of lupus-prone mice with a dual inhibitor of TLR7 and TLR9 leads to reduction of autoantibody production and amelioration of disease symptoms. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37(12):3582–3586. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Gregorio J, et al. Nucleic acids of mammalian origin can act as endogenous ligands for Toll-like receptors and may promote systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;202(8):1131–1139. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Batteux F, Palmer P, Daëron M, Weill B, Lebon P. FCγRII (CD32)-dependent induction of interferon-alpha by serum from patients with lupus erythematosus. European Cytokine Network. 1999;10(4):509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Båve U, Magnusson M, Eloranta M-L, Perers A, Alm GV, Rönnblom L. FcγRIIa is expressed on natural IFN-α-producing cells (plasmacytoid dendritic cells) and is required for the IFN-α production induced by apoptotic cells combined with Lupus IgG. Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(6):3296–3302. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savarese E, Chae O-W, Trowitzsch S, et al. U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein immune complexes induce type I interferon in plasmacytoid dendritic cells through TLR7. Blood. 2006;107(8):3229–3234. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajagopal D, Paturel C, Morel Y, Uematsu S, Akira S, Diebold SS. Plasmacytoid dendritic cell-derived type I interferon is crucial for the adjuvant activity of Toll-like receptor 7 agonists. Blood. 2010;115(10):1949–1957. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-238543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asselin-Paturel C, Brizard G, Chemin K, et al. Type I interferon dependence of plasmacytoid dendritic cell activation and migration. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201(7):1157–1167. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niewold TB, Rivera TL, Buyon JP, Crow MK. Serum type I interferon activity is dependent on maternal diagnosis in anti-SSA/Ro-positive mothers of children with neonatal lupus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(2):541–546. doi: 10.1002/art.23191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farkas A, Tonel G, Nestle FO. Interferon-α and viral triggers promote functional maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. British Journal of Dermatology. 2008;158(5):921–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakakibara M, Kanto T, Inoue M, et al. Quick generation of fully mature dendritic cells from monocytes with OK432, low-dose prostanoid, and interferon-α as potent immune enhancers. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2006;29(1):67–77. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000183093.77687.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blanco P, Palucka AK, Gill M, Pascual V, Banchereau J. Induction of dendritic cell differentiation by IFN-α in systemic lupus erythematosus. Science. 2001;294(5546):1540–1543. doi: 10.1126/science.1064890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito T, Amakawa R, Inaba M, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells regulate Th cell responses through OX40 ligand and type I IFNs. Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(7):4253–4259. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohty M, Vialle-Castellano A, Nunes JA, Isnardon D, Olive D, Gaugler B. IFN-α skews monocyte differentiation into toll-like receptor 7-expressing dendritic cells with potent functional activities. Journal of Immunology. 2003;171(7):3385–3393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cucak H, Yrlid U, Reizis B, Kalinke U, Johansson-Lindbom B. Type I interferon signaling in dendritic cells stimulates the development of lymph-node-resident T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2009;31(3):491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baráth S, Soltész P, Kiss E, et al. The severity of systemic lupus erythematosus negatively correlates with the increasing number of CD4+CD25highFoxP3+ regulatory T cells during repeated plasmapheresis treatments of patients. Autoimmunity. 2007;40(7):521–528. doi: 10.1080/08916930701610028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonelli M, Savitskaya A, Von Dalwigk K, et al. Quantitative and qualitative deficiencies of regulatory T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) International Immunology. 2008;20(7):861–868. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu S, Xiao W, Kong F, Ke D, Qin R, Su M. Regulatory T cells and their molecular markers in peripheral blood of the patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology—Medical Science. 2008;28(5):549–552. doi: 10.1007/s11596-008-0513-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suen J-L, Li H-T, Jong Y-J, Chiang B-L, Yen J-H. Altered homeostasis of CD4+FoxP3+ regulatory T-cell subpopulations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology. 2009;127(2):196–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02937.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Venigalla RKC, Tretter T, Krienke S, et al. Reduced CD4+,CD25-T cell sensitivity to the suppressive function of CD4+, CD25high, CD127−/low regulatory T cells in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(7):2120–2130. doi: 10.1002/art.23556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yates J, Whittington A, Mitchell P, Lechler RI, Lightstone L, Lombardi G. Natural regulatory T cells: number and function are normal in the majority of patients with lupus nephritis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2008;153(1):44–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03665.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gómez J, Prado C, López P, Suárez A, Gutiérrez C. Conserved anti-proliferative effect and poor inhibition of TNFα secretion by regulatory CD4+CD25+ T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Immunology. 2009;132(3):385–392. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gigante M, Mandic M, Wesa AK, et al. Interferon-alpha (IFN-α)-conditioned DC preferentially stimulate type-1 and limit treg-type in vitro T-cell responses from RCC patients. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2008;31(3):254–262. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318167b023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan B, Ye S, Chen G, Kuang M, Shen N, Chen S. Dysfunctional CD4+,CD25+ regulatory T cells in untreated active systemic lupus erythematosus secondary to interferon-α-producing antigen-presenting cells. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(3):801–812. doi: 10.1002/art.23268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruuth K, Carlsson L, Hallberg B, Lundgren E. Interferon-α promotes survival of human primary B-lymphocytes via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2001;284(3):583–586. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oka H, Hirohata S, Inoue T, Ito K. Effects of interferon-α on human B cell responsiveness: biphasic effects in cultures stimulated with Staphylococcus aureus. Cellular Immunology. 1992;139(2):478–492. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oka H, Hirohata S. Regulation of human B cell responsiveness by interferon-α: interferon-α-mediated suppression of B cell function is reversed through direct interactions between monocytes and B cells. Cellular Immunology. 1993;146(2):238–248. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1993.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alarcón-Segovia D, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Cardiel MH, et al. Familial aggregation of systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other autoimmune diseases in 1,177 lupus patients from the GLADEL cohort. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52(4):1138–1147. doi: 10.1002/art.20999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deapen D, Escalante A, Weinrib L, et al. A revised estimate of twin concordance in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1992;35(3):311–318. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wandstrat A, Wakeland E. The genetics of complex autoimmune diseases: non-MHC susceptibility genes. Nature Immunology. 2001;2(9):802–809. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sebastiani GD, Galeazzi M. Immunogenetic studies on systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009;18(10):878–883. doi: 10.1177/0961203309106918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moser KL, Kelly JA, Lessard CJ, Harley JB. Recent insights into the genetic basis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes and Immunity. 2009;10(5):373–379. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harley ITW, Kaufman KM, Langefeld CD, Harley JB, Kelly JA. Genetic susceptibility to SLE: new insights from fine mapping and genome-wide association studies. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10(5):285–290. doi: 10.1038/nrg2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Graham RR, Hom G, Ortmann W, Behrens TW. Review of recent genome-wide association scans in lupus. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2009;265(6):680–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rhodes B, Vyse TJ. The genetics of SLE: an update in the light of genome-wide association studies. Rheumatology. 2008;47(11):1603–1611. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee YH, Song GG. Association between the rs2004640 functional polymorphism of interferon regulatory factor 5 and systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology International. 2009;29(10):1137–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kawasaki A, Kyogoku C, Ohashi J, et al. Association of IRF5 polymorphisms with systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population: support for a crucial role of intron 1 polymorphisms. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(3):826–834. doi: 10.1002/art.23216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kelly JA, Kelley JM, Kaufman KM, et al. Interferon regulatory factor-5 is genetically associated with systemic lupus erythematosus in African Americans. Genes and Immunity. 2008;9(3):187–194. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reddy MVPL, Velázquez-Cruz R, Baca V, et al. Genetic association of IRF5 with SLE in Mexicans: higher frequency of the risk haplotype and its homozygozity than Europeans. Human Genetics. 2007;121(6):721–727. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0367-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimane K, Kochi Y, Yamada R, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the IRF5 promoter region is associated with susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis in the Japanese population. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;68(3):377–383. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.085704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Graham RR, Kyogoku C, Sigurdsson S, et al. Three functional variants of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) define risk and protective haplotypes for human lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(16):6758–6763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701266104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graham RR, Kyogoku C, Sigurdsson S, et al. Three functional variants of IFN regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) define risk and protective haplotypes for human lupus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(16):6758–6763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701266104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niewold TB, Kelly JA, Flesch MH, Espinoza LR, Harley JB, Crow MK. Association of the IRF5 risk haplotype with high serum interferon-α activity in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(8):2481–2487. doi: 10.1002/art.23613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harley JB, Alarcón-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(2):204–210. doi: 10.1038/ng.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suarez-Gestal M, Calaza M, Endreffy E, et al. Replication of recently identified systemic lupus erythematosus genetic associations: a case-control study. Arthritis Research and Therapy. 2009;11(3, article 69) doi: 10.1186/ar2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salloum R, Franek B, Kariuki S, Utset T, Niewold TT. Genetic variation at the IRF7/KIAA1542 locus is associated with autoantibody profile and serum interferon alpha levels in lupus patients. Clinical Immunology. 2009;131(supplement 1):p. S54. doi: 10.1002/art.27182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Armstrong DL, Reiff A, Myones BL, et al. Identification of new SLE-associated genes with a two-step Bayesian study design. Genes and Immunity. 2009;10(5):446–456. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu C-J, Zhang W-H, Pan H-F, Li X-P, Xu J-H, Ye D-Q. Association study of a single nucleotide polymorphism in the exon 2 region of toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) gene with susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus among Chinese. Molecular Biology Reports. 2009;36(8):2245–2248. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9440-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jacob CO, Zhu J, Armstrong DL, et al. Identification of IRAK1 as a risk gene with critical role in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(15):6256–6261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bates JS, Lessard CJ, Leon JM, et al. Meta-analysis and imputation identifies a 109kb risk haplotype spanning TNFAIP3 associated with lupus nephritis and hematologic manifestations. Genes and Immunity. 2009;10(5):470–477. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Genetics. 2009;41(11):1228–1233. doi: 10.1038/ng.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Graham RR, Cotsapas C, Davies L, et al. Genetic variants near TNFAIP3 on 6q23 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(9):1059–1061. doi: 10.1038/ng.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Han J-W, Zheng H-F, Cui Y, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Genetics. 2009;41(11):1234–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Musone SL, Taylor KE, Lu TT, et al. Multiple polymorphisms in the TNFAIP3 region are independently associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(9):1062–1064. doi: 10.1038/ng.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Honma K, Tsuzuki S, Nakagawa M, et al. TNFAIP3/A20 functions as a novel tumor suppressor gene in several subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2009;114(12):2467–2475. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-194852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kato M, Sanada M, Kato I, et al. Frequent inactivation of A20 in B-cell lymphomas. Nature. 2009;459(7247):712–716. doi: 10.1038/nature07969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kariuki SN, Kirou KA, MacDermott EJ, Barillas-Arias L, Crow MK, Niewold TB. Cutting edge: autoimmune disease risk variant of STAT4 confers increased sensitivity to IFN-alpha in lupus patients in vivo. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182(1):34–38. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abelson AK, Delgado-Vega AM, Kozyrev SV, et al. STAT4 associates with systemic lupus erythematosus through two independent effects that correlate with gene expression and act additively with IRF5 to increase risk. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;68(11):1746–1753. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.097642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sigurdsson S, Nordmark G, Garnier S, et al. A risk haplotype of STAT4 for systemic lupus erythematosus is over-expressed, correlates with anti-dsDNA and shows additive effects with two risk alleles of IRF5. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17(18):2868–2876. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao W, Liu Y-J. Opn: key regulator of pDC interferon production. Nature Immunology. 2006;7(5):441–443. doi: 10.1038/ni0506-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kariuki SN, Moore JG, Kirou KA, Crow MK, Utset TO, Niewold TB. Age- and gender-specific modulation of serum osteopontin and interferon-α by osteopontin genotype in systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes and Immunity. 2009;10(5):487–494. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ronnblom LE, Alm GV, Oberg KE. Possible induction of systemic lupus erythematosus by interferon α-treatment in a patient with a malignant carcinoid tumour. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1990;227(3):207–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Niewold TB, Swedler WI. Systemic lupus erythematosus arising during interferon-alpha therapy for cryoglobulinemic vasculitis associated with hepatitis C. Clinical Rheumatology. 2005;24(2):178–181. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-1024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ioannou Y, Isenberg DA. Current evidence for the induction of autoimmune rheumatic manifestations by cytokine therapy. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2000;43(7):1431–1442. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1431::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gota C, Calabrese L. Induction of clinical autoimmune disease by therapeutic interferon-α. Autoimmunity. 2003;36(8):511–518. doi: 10.1080/08916930310001605873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythrematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1982;25(11):1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ho V, McLean A, Terry S. Severe systemic lupus erythematosus induced by antiviral treatment for hepatitis C. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;14(3):166–168. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181775e80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Niewold TB. Interferon alpha-induced lupus: proof of principle. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 2008;14(3):131–132. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318177627d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Niewold TB, Hua J, Lehman TJA, Harley JB, Crow MK. High serum IFN-α activity is a heritable risk factor for systemic lupus erythematosus. Genes and Immunity. 2007;8(6):492–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Niewold TB, Adler JE, Glenn SB, Lehman TJA, Harley JB, Crow MK. Age- and sex-related patterns of serum interferon-α activity in lupus families. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2008;58(7):2113–2119. doi: 10.1002/art.23619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weckerle CE, Niewold TB. The unexplained female predominance of systemic lupus erythematosus: clues from genetic and cytokine studies. doi: 10.1007/s12016-009-8192-4. Clinical Reviews in Allergy and Immunology, 2010. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kirou KA, Lee C, George S, Louca K, Peterson MGE, Crow MK. Activation of the interferon-α pathway identifies a subgroup of systemic lupus erythematosus patients with distinct serologic features and active disease. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;52(5):1491–1503. doi: 10.1002/art.21031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dall’Era MC, Cardarelli PM, Preston BT, Witte A, Davis JC., Jr. Type I interferon correlates with serological and clinical manifestations of SLE. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2005;64(12):1692–1697. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.033753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Feng X, Wu H, Grossman JM, et al. Association of increased interferon-inducible gene expression with disease activity and lupus nephritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(9):2951–2962. doi: 10.1002/art.22044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhuang H, Narain S, Sobel E, et al. Association of anti-nucleoprotein autoantibodies with upregulation of type I interferon-inducible gene transcripts and dendritic cell maturation in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Immunology. 2005;117(3):238–250. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Landolt-Marticorena C, Bonventi G, Lubovich A, et al. Lack of association between the interferon-α signature and longitudinal changes in disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2009;68(9):1440–1446. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.093146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petri M, Singh S, Tesfasyone H, et al. Longitudinal expression of type I interferon responsive genes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009;18(11):980–989. doi: 10.1177/0961203309105529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bauer JW, Petri M, Batliwalla FM, et al. Interferon-regulated chemokines as biomarkers of systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity: a validation study. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(10):3098–3107. doi: 10.1002/art.24803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yao Y, Richman L, Higgs BW, et al. Neutralization of interferon-α/β-inducible genes and downstream effect in a phase I trial of an anti-interferon-α monoclonal antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009;60(6):1785–1796. doi: 10.1002/art.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]