Abstract

A novel highly efficient regiodivergent Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization of allenyl- and homopropargylic ketones into synthetically valuable 2- and 3-silylfurans has been designed with the aid of the DFT calculations. This cascade transformation features 1,2-Si- or 1,2-H migrations in a common Au-carbene intermediate. Both experimental and computational results clearly indicate that the 1,2-Si migration is kinetically favored over the 1,2-shifts of H, alkyl, and aryl groups in the β-Si-substituted Au-carbenes. In addition, experimental results on the Au(I)-catalyzed cycloisomerization of homopropargylic ketones demonstrated that counterion and solvent effects could reverse the above migratory preference. The DFT calculations provided a rationale for this 1,2-migration regiodivergency. Thus, in the case of AuSbF6−, DFT-simulated reaction proceeds through the initial propargyl-allenyl isomerization followed by the cyclization into the Au-carbene intermediate with the exclusive formation of 1,2-Si migration products and solvent effects cannot affect this regioselectivity. However, in the case of TfO−-counterion, reaction occurs via the initial 5-endo-dig cyclization to give cyclic furyl-Au intermediate. In the case of nonpolar solvents, subsequent ipso-protiodeauration of the latter is kinetically more favorable than the generation of the common Au-carbene intermediate and leads to the formation of formal 1,2-H migration products. In contrast, when polar solvent is employed in this DFT-simulated reaction, β-to-Au protonation of the furyl-Au species to give Au-carbene intermediate competes with the ipso-protiodeauration. Subsequent dissociation of the triflate ligand in this carbene in polar media due to efficient solvation of charged intermediates facilitates formation of the 1,2-Si shift products. The above results of DFT calculations were validated by the experimental data. The present study demonstrates that the DFT calculations could efficiently support experimental results, providing guidance for rational design of new catalytic transformations.

Keywords: furans, gold, rearrangement, allenes, alkynes, DFT calculations

Introduction

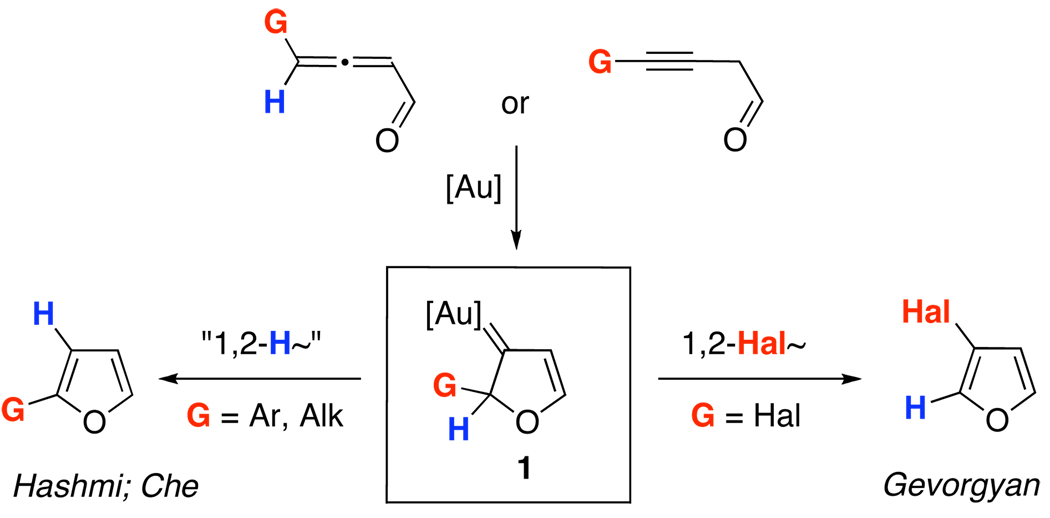

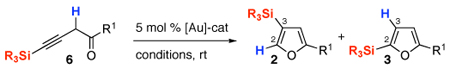

Cycloisomerizations of alkynes and allenes arguably represent the most versatile methodologies for the assembly of heterocycles.1 Introduction of molecular rearrangements into these processes often provides highly efficient routes toward densely substituted heterocycles. Within this area, Hashmi2 and later Che3 reported Au-catalyzed4 cycloisomerizations of alkynyl- and allenyl ketones into furans.5 These cascades were proposed to proceed via a formation of the key putative Au-carbene 1 followed by a formal 1,2-H shift (Scheme 1).6 Apparently, 1,2-migration of groups other than H, proceeding via intermediate 1, would allow for an expedient synthesis of diversely functionalized furans with substitution patterns not easily accessible via the existing methodologies.7 Along this line, we recently reported the Au-catalyzed regiodivergent synthesis of halofurans involving 1,2-Hal or 1,2-H migration in 1.7j Herein, we wish to report a computation-designed regiodivergent Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization of homopropargyl- and allenyl ketones into silylfurans, featuring 1,2-Si- or 1,2-H migration in the Au-carbene intermediate 1 (Scheme 2).

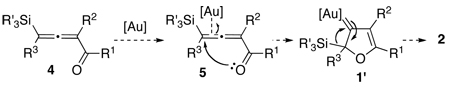

Scheme 1.

1,2-Group Migrations in the Synthesis of Furans via Au-Carbene Intermediate 1

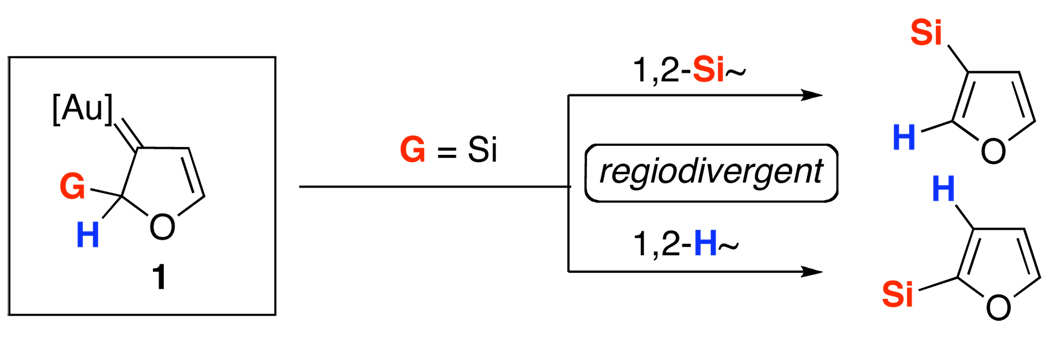

Scheme 2.

Regiodivergent 1,2-Si Migrations in the Synthesis of Furans via Au-Carbene Intermediate

Results and Discussion

Recent DFT study revealed that the Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization of bromoallenyl ketones7j proceeds through the Au-carbene 1, wherein the 1,2-Br migration is kinetically favored over a facile 1,2-H shift.8 Naturally, we were interested in identifying other migrating groups capable of undergoing a selective 1,2-migration over the 1,2-H shift. Thus, we turned our attention to a silyl group, which is known to undergo a facile 1,2-migration to electron-deficient centers. Despite the well-known 1,2-Si migration to cationic centers,9,10 only little attention was devoted to 1,2-Si shifts to free-11 or metal-stabilized carbenes,12 especially with a focus on synthetic significance. Besides, scarce studies on migratory aptitudes in these systems have been reported.11,12

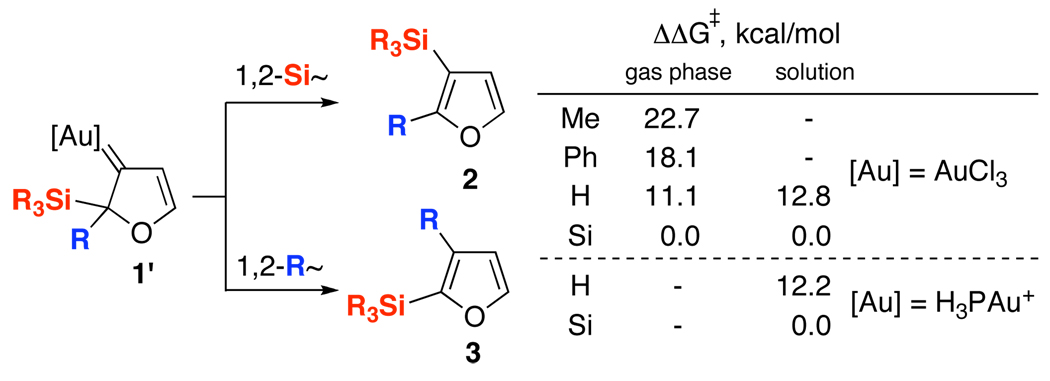

We envisioned that DFT calculations could shed light on the relative rates of 1,2-migrations of Si-, Hand alkyl groups in the Au-carbene 1’ (Scheme 3).13 Thus, the results of DFT computations14,15 indicated that the 1,2-Si migration is strongly favored over the 1,2-shifts of methyl, phenyl, and even H in 1’ for both AuCl3 and H3PAu+ (Scheme 3).14

Scheme 3.

Predicted Activation Energies for the 1,2-Si- versus 1,2-R Migration in the Au-Carbene Intermediate 1’

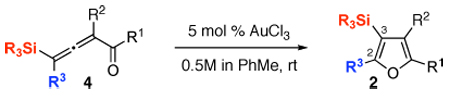

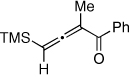

Synthesis of Furans via Au(III)-Catalyzed 1,2-Si Migration in Allenes

It occurred to us that the Au-catalyzed cyclization of silyl allenes 4 could provide a straightforward access to the Au-carbene 1’ via a well-established route (eq 1).2,6 The latter intermediate, upon the 1,2-Si shift, should furnish the 3-silylfuran 2.

|

(1) |

To this end, we have tested the possible cycloisomerization of allenes 4 into 3-silylfurans 2 in the presence of various Au catalysts. Gratifyingly, it was found, that α-to-Si alkyl-substituted allenes 4a and 4b in the presence of AuCl3-catalyst underwent a highly selective 1,2-Si migration, affording 3-silylfurans 2a and 2b in high yields (Table 1, entries 1–2). Likewise, cycloisomerization of phenyl-substituted allenes 4c,d proceeded highly efficiently to give 3-silylfurans 2c,d as sole isomers (entries 3–4). To our delight, α-to-Si-unsubstituted allene 4e cyclized highly selectively into a product of the exclusive 1,2-Si- over 1,2-H shift 2e in both toluene or more polar, nitromethane, solvent (entry 5). Thus, the experimentally observed exclusive Si-migration is in an excellent agreement with the computation-predicted higher 1,2-migratory aptitude of Si- over H-, Alk-, and Ar groups. It is worth mentioning, that allene 4e was not stable in the presence of Ph3PAuOTf complex when performing reaction in toluene or 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) solvents. In addition, similarly to AuCl3, employment of Ph3PAuSbF6 catalyst provided exclusive formation of 1,2-Si migration product 2e in DCE solvent, albeit notable amounts of the desilylated 3-methyl-2-phenylfuran were observed.

Table 1.

Au-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Allenyl Ketones 4

Isolated yield of product for reactions performed on 0.5 mmol scale.

Isolated yield of 2e for reaction performed in MeNO2.

Isolated yield of 2e for reaction performed with 1 mol % of catalyst.

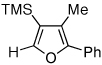

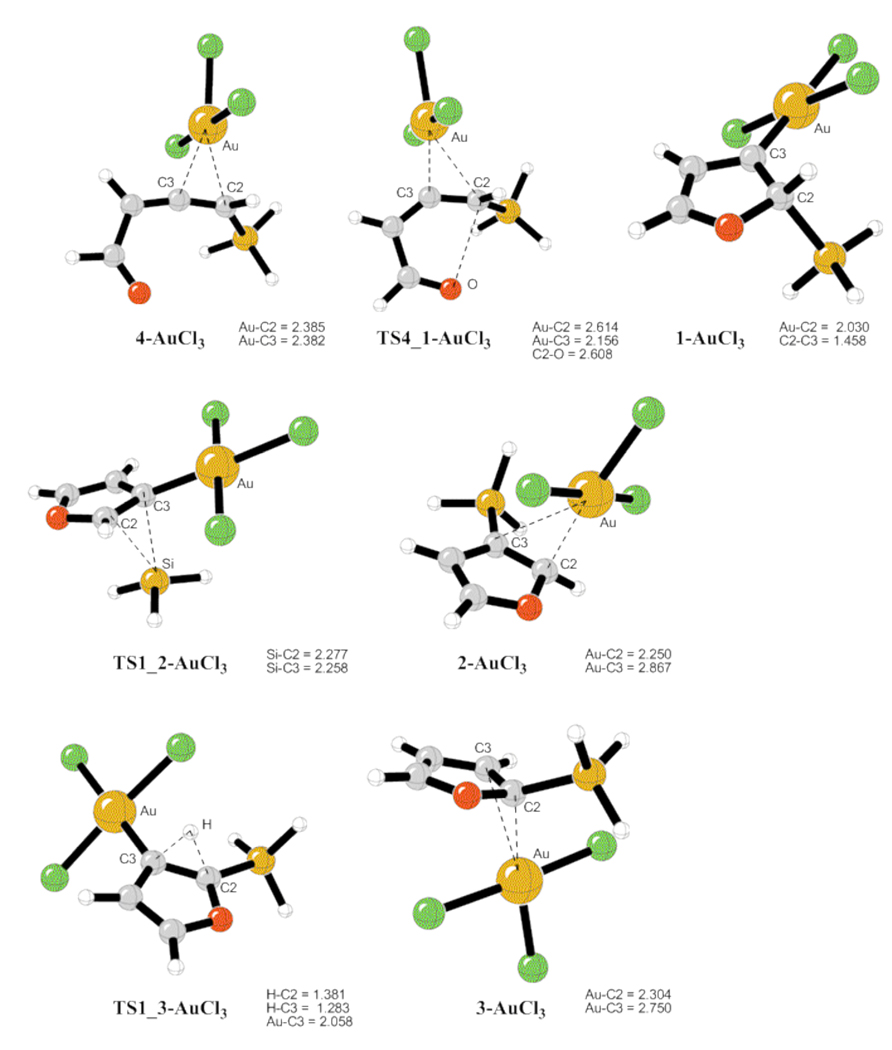

The computed energy surface for the Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization of allene 4 (AuCl3) is provided in Scheme 4.14 Hence, a highly exergonic (24.7 kcal/mol) cyclization of complex 4-AuCl3 into the carbene 1-AuCl3 required 2.6 kcal/mol activation energy only. A subsequent kinetically more favorable 1,2-Si migration (TS1_2-AuCl3, 11.1 kcal/mol activation energy) over the 1,2-H shift (TS1_3-AuCl3, 23.6 kcal/mol activation energy) led to the product complex 2-AuCl3. A requisite ligand exchange reaction proceeded as illustrated in Scheme 5 to complete the catalytic cycle, thus furnishing the final products and regenerating the active allene complex 4-AuCl3. The free energy values indicated that the formation of 2 and 3 via the reactions of allene 4 with 2-AuCl3 and 3-AuCl3 were both endergonic by 17.8 and 12.2 kcal/mol, respectively (Scheme 5). The optimized structures of key stationary points along the reaction pathway for the cycloisomerization of allenes 4 are presented in Figure 1.

Scheme 4.

Potential Energy Surfaces for the AuCl3-catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Allenes 4 (R = H)

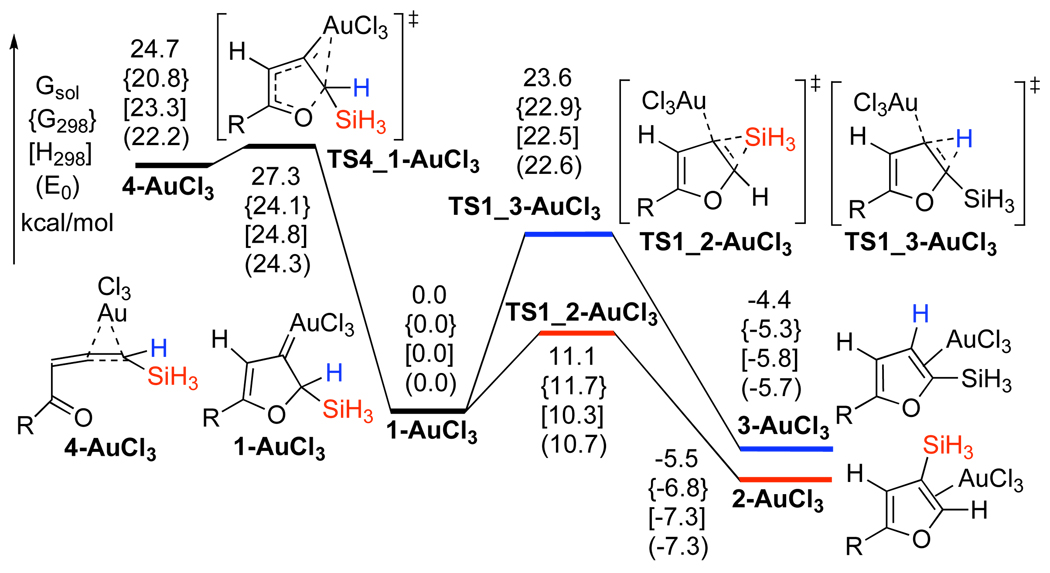

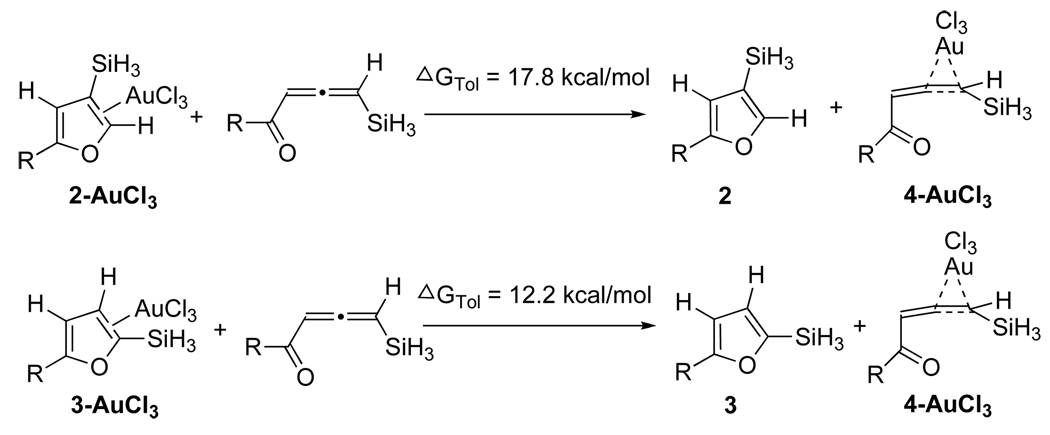

Scheme 5.

Generation of Products 2 and 3 from Complexes 2-AuCl3 and 3-AuCl3

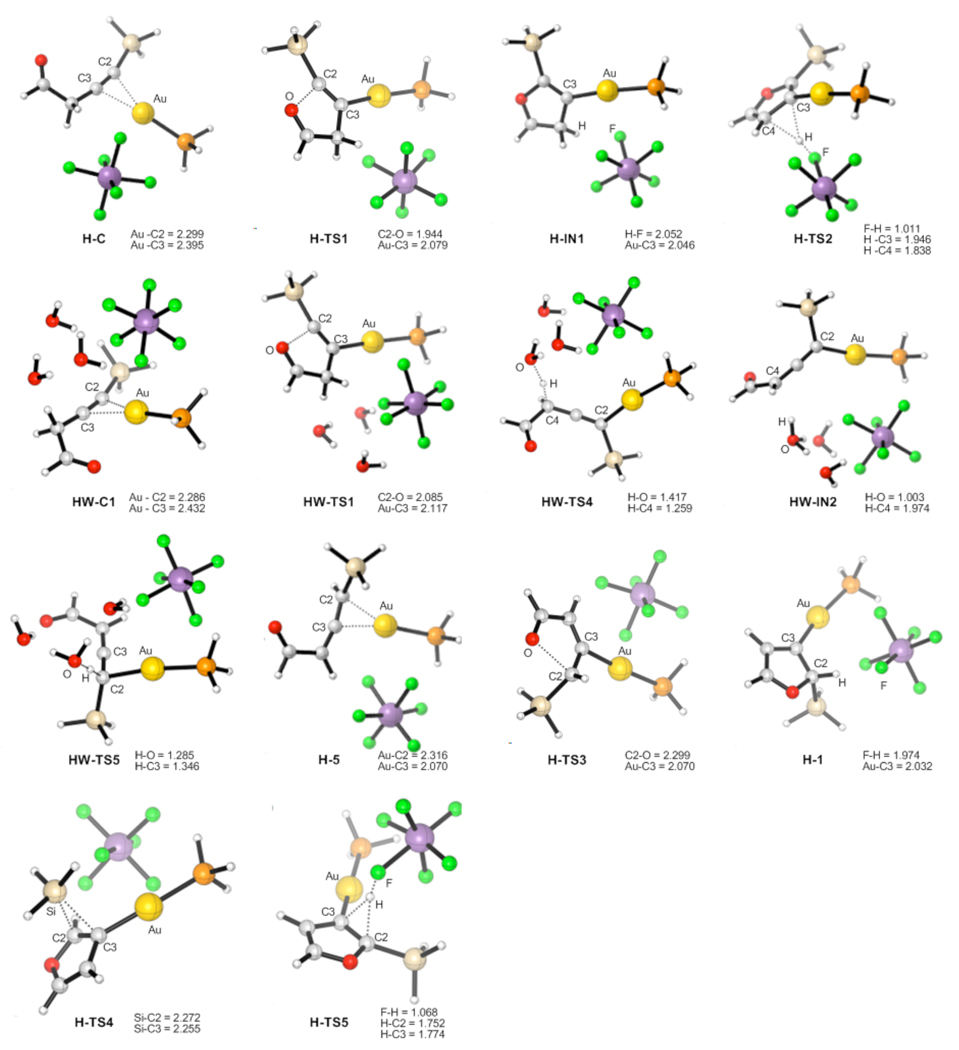

Figure 1.

Geometries for the intermediates and transition states given in Scheme 4, selected distances are in angstroms

Counterion Effects on the Au(I)-Catalyzed 1,2-Si Migration in Alkynes

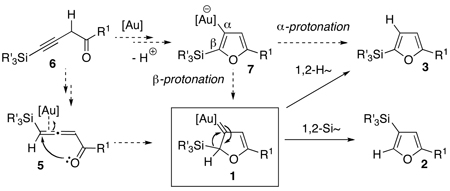

Next, we envisioned that easily accessible homopropargylic ketones 6 could also serve as precursors7e,7j for the allene 5 toward the common Au-carbene intermediate 1 (eq 2). Alternatively, cyclization of 6 into furyl-Au species 7,2,16 followed by its β-protonation at the vinyl-gold moiety17 would generate the Au-carbene 1. Based on the computation results, it was predicted that a subsequent facile 1,2-Si shift in 1 would furnish 3-silylfuran 2. On the other hand, counterion-assisted8,18 1,2-H shift in 1 or direct α-protonation of the vinyl-Au moiety in 7 might compete with the 1,2-Si migration, affording the 2-silylfurans 3 (eq 2).

|

(2) |

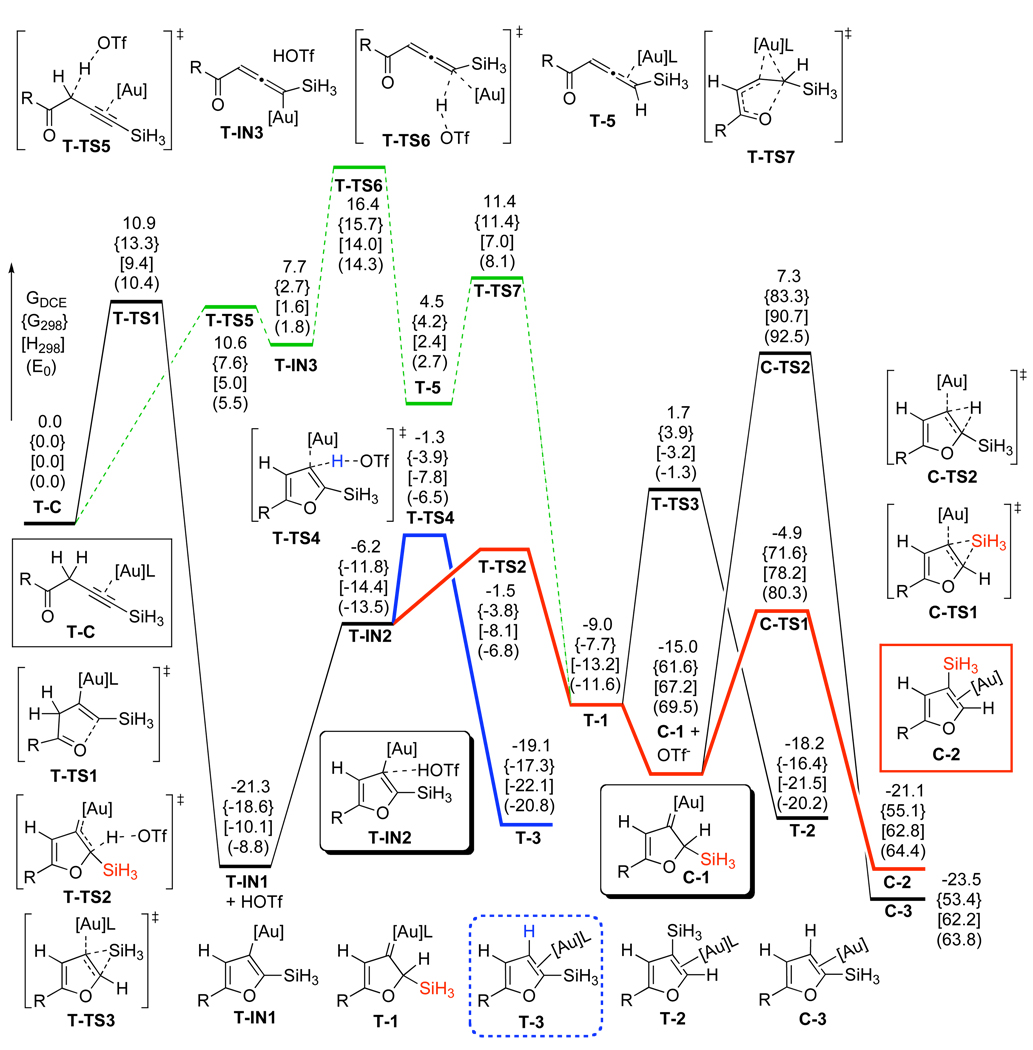

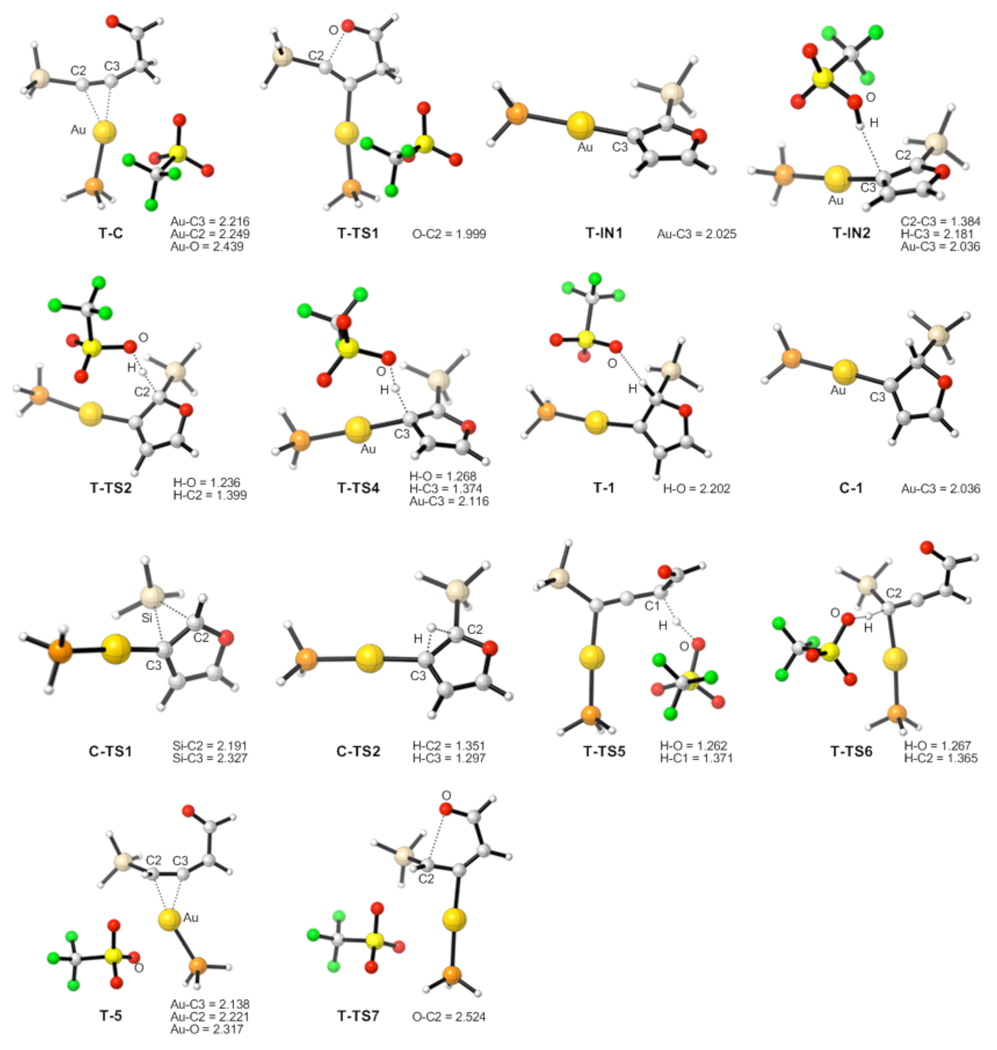

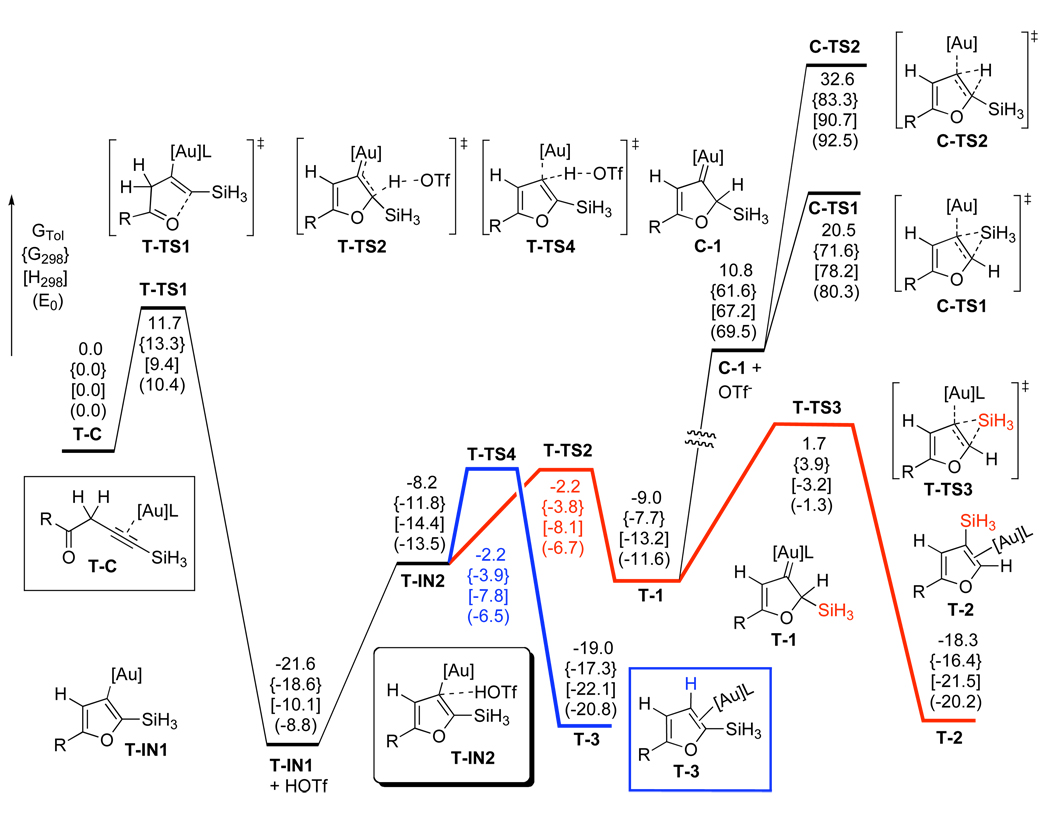

Thus, DFT calculations were performed to evaluate possible counterion effects8,18 and establish overall reaction pathways for cycloisomerization of homopropargylic ketones 6 in the presence of electrophilic Ph3PAuOTf and Ph3PAuSbF6 catalysts in DCE or toluene solvents, respectively. The potential energy surfaces for the predictions of the effects of TfO−- and SbF6−-counterions are depicted in Schemes 6 and 7, respectively. In the case of Ph3PAuOTf catalyst in DCE solution (Scheme 6), a highly exergonic (21.3 kcal/mol) direct 5-endo-dig cyclization of complex T-C proceeded with the simultaneous abstraction of propargylic H-atom by TfO−-counterion to give the furyl-Au T-IN1 and HOTf, requiring 10.9 kcal/mol activation energy. Subsequent endergonic association of HOTf (15.1 kcal/mol) with the α-C-atom of the vinyl-Au moiety in T-IN1 followed by ipso-protiodeauration of the T-IN2 intermediate (T-TS4, 4.9 kcal/mol activation energy) provided product of the formal 1,2-H migration T-3. On the other hand, kinetically more favorable β-protonation at the vinyl-gold moiety in T-IN2 (T-TS2, 4.7 kcal/mol activation energy) over the ipso-protiodeauration (T-TS4, 4.9 kcal/mol activation energy) should lead to a competing generation of the Au carbene T-1. Subsequent 1,2-Si migration from T-1 required 10.7 kcal/mol free energy (T-TS3) to give 1,2-Si migration product T-2. Alternatively, it was found that TfO− ligand dissociation reaction could occur efficiently from carbene T-1 (6.0 kcal/mol) to give more electrophilic carbene C-1, wherein a more kinetically facile 1,2-Si shift (C-TS1, 10.1 kcal/mol activation energy) afforded 3-silylfuran C-2. In both carbene intermediates T-1 and C-1, direct 1,2-H migrations were predicted to have higher activation energy barriers, than those for direct 1,2-Si shifts (C-TS2 versus C-TS1, 22.3 versus 10.1 kcal/mol activation free energy, respectively). In addition, an alternative reaction pathway, involving generation of reactive allene-Au complex T-5 via Ph3PAuOTf-assisted propargyl-allenyl isomerization of T-C was found to be higher in energy (T-TS6, 16.4 kcal/mol) than the direct cyclization route in DCE. Thus, based on the predicted 0.2 kcal/mol difference between α- (T-TS4) and β- (T-TS2) protonation paths, a competing formation of products 2 and 3 can be expected in the Ph3PAuOTf-catalyzed cycloisomerization of homopropargylic ketone 6. It should be mentioned that analogous high-energy profiles were later found for the propargyl-allenyl isomerization of 6 into 5 and for the direct 1,2-H shift in Au-carbene intermediates 1 in toluene solvent (vide infra). The optimized structures of key stationary points along the reaction pathway for the Ph3PAuOTf-catalyzed cycloisomerization of alkynes 6 are presented in Figure 2.

Scheme 6.

DFT Predictions for the Ph3PAuOTf-Catalyzed Reaction ([Au] = AuPH3, L = OTf, R = H) in 1,2-Dichloroethane Solution, Relative Energies (ΔGDCE, ΔG298, ΔH298, ΔE0) are in kcal/mol

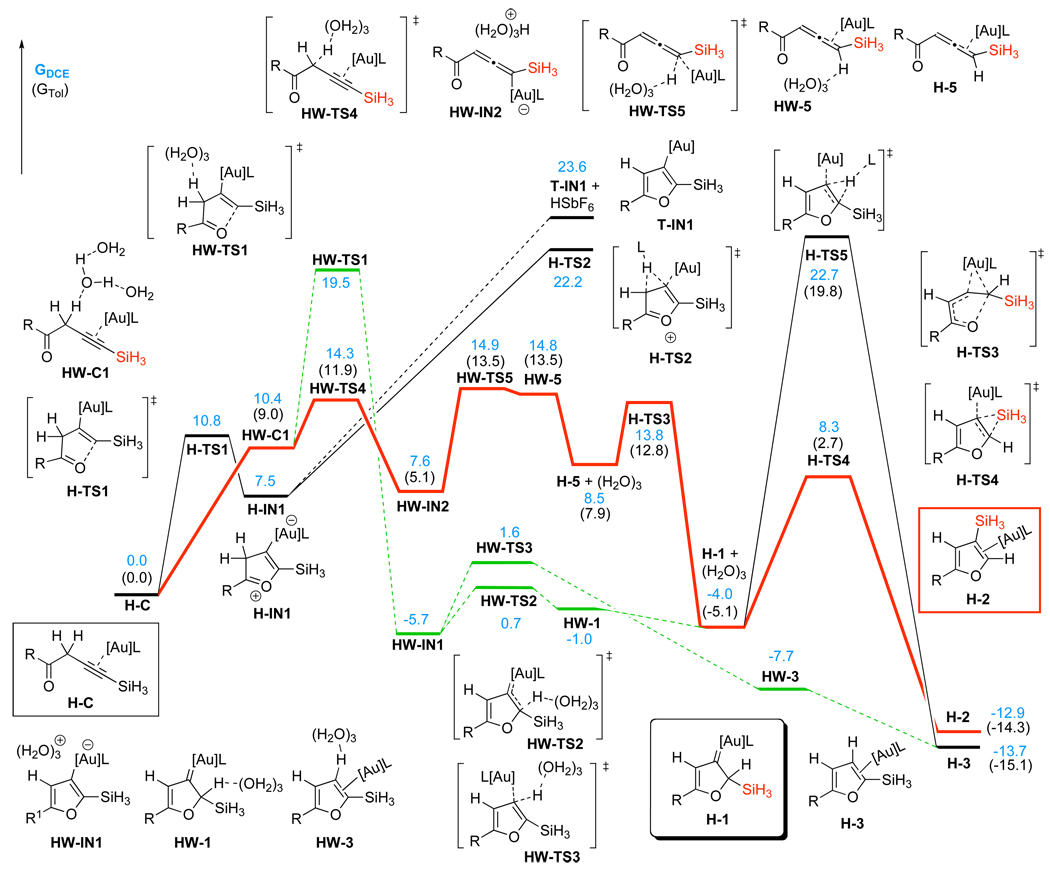

Scheme 7.

DFT Predictions for the Ph3PAuSbF6-Catalyzed Reaction ([Au] = AuPH3, L = SbF6, R = H) in 1,2-Dichloroethane and Toluene Solutions, Relative Energies (ΔGDCE, ΔGTol) are in kcal/mol

Figure 2.

Geometries of the intermediates and transition states for the Ph3PAuOTf-catalyzed reaction, selected distances are in angstroms

In the case of Ph3PAuSbF6 catalyst (Scheme 7) in DCE solvent, direct 5-endo-dig cyclization of complex H-C afforded cyclic zwitter-ionic intermediate H-IN1 via the H-TS1 transition state, requiring 10.8 kcal/mol activation free energy. However, we were not able to locate the next transition state for the highly endergonic (23.6 kcal/mol) formation of the furyl-Au intermediate T-IN1 and HSbF6, probably due to an extreme acidity of HSbF6. An alternative pathway, involving a [1,5]-hydride shift via H-TS2, was also found to be high in energy (22.2 kcal/mol activation free energy). We believe that an extremely high acidity of HSbF6 and very low nucleophilicity of its conjugate base SbF6− complicate DFT-simulation of the elementary reaction processes involving a counterion-assisted proton transfer step. This reasoning prompted us to perform DFT-calculations of the Ph3PAuSbF6-catalyzed reaction in the presence of three water molecule cluster (H2O)3, which could model reactivity of a more nucleophilic than SbF6− counterion and much milder than HSbF6 acid in its monoprotonated form. Accordingly, initial coordination of water cluster to homopropargylic ketone H-C provided HW-C1 endergonically (10.4 kcal/mol free energy).8,13h Similarly to TfO−-counterion, water cluster could also abstract propargylic H-atom during a subsequent 5-endo-dig cyclization of HW-C1 (HW-TS1, 9.1 kcal/mol activation free energy) to give the furyl-Au HW-IN1 and protonated water cluster.19 However, a lower energy reaction path was found for the complex HW-C1. Thus, formation of the activated allene H-5 from the latter occurred as a stepwise H-abstraction/donation process via transition states HW-TS4 and HW-TS5, respectively. The first step of this process required an activation free energy of only 3.9 kcal/mol in DCE and 2.9 kcal/mol in toluene, respectively, leading to the intermediate HW-IN2 exergonically. The second quite facile H-donation step to give HW-5 occurred with the activation energies of 7.3 kcal/mol (DCE) or 8.4 kcal/mol (toluene) and was followed by exergonic decoordination of water cluster to produce allene-Au complex H-5. A facile cyclization of the latter via H-TS3 provided Au-carbene H-1 with 5.3 kcal/mol activation free energy in DCE and 4.9 kcal/mol in toluene. A subsequent 1,2-Si migration in H-1 via H-TS4 was strongly favored over the 1,2-H shift (H-TS5) in both DCE and toluene solvents, leading to the 1,2-Si migration product complex H-2. The optimized structures of key stationary points along the reaction pathway for the Ph3PAuSbF6-catalyzed cycloisomerization of alkynes 6 are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Geometries of the intermediates and transition states for the Ph3PAuSbF6-catalyzed reaction, selected distances are in angstroms

To examine the above DFT-based prognosis, we investigated cycloisomerization of the homopropargylic ketones 6 in the presence of various Au catalysts (Table 2). It was found that the experimental results overall are in good agreement with the computational predictions.14 Thus, the Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization of alkynes 6 in the presence of non-nucleophilic SbF6−-counterion in DCE gives exclusive formation of 1,2-Si migration products 2f, l, and k (entries 1, 7, 11). As suggested by the DFT-calculations, switching to Ph3PAuOTf catalyst in DCE with a more nucleophilic counterion leads to a competing formation of 1,2-Si- and 1,2-H migration products 2f and 3f, respectively, for the cycloisomerization of 6f (entry 2). However, the DFT predictions cannot explain a selective formation of the 1,2-Si migration product 2l during the cycloisomerization of 6l (entry 10). In addition, it was found that AuCl3 could also catalyze cycloisomerization of alkynes 6, however, the regioselectivity of this reaction toward the 1,2-Si migration product 2f was poor in a variety of solvents (entries 4–6). Unfortunately, analogous study on counterion effect in allenyl systems was not possible since allenes 4 were not stable in the presence of Ph3PAuOTf and even less electrophilic Ph3PAuOBz complexes.

Table 2.

Optimization of the Au-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Homopropargyl Ketones 6

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | R1 | Catalyst | Solvent (C, M) | 2 : 3 Ratioa |

| 1 | Ph (6f) | Ph3PAuSbF6 | DCE (0.05) | 100 : 0 |

| 2 | Ph3PAuOTf | DCE (0.05) | 66 : 34 | |

| 3 | Ph3PAuOTf | PhMe (0.1) | 7 : 93 | |

| 4 | AuCl3 | PhMe (0.1) | 60 : 40 | |

| 5 | AuCl3 | DCE (0.1) | 72 : 28 | |

| 6 | AuCl3 | MeNO2 (0.05) | 84 : 16 | |

| 7 | n-C8H17 (6l) | Ph3PAuSbF6 | DCE (0.05) | 100 : 0 |

| 8 | Ph3PAuSbF6 | PhMe (0.05) | 100 : 0 | |

| 9 | Ph3PAuOTf | PhMe (0.1) | 12 : 88 | |

| 10 | Ph3PAuOTf | DCE (0.05) | 98 : 2 | |

| 11 | t-Bu (6k) | Ph3PAuSbF6 | DCE (0.05) | 100 : 0 |

| 12 | Ph3PAuOTf | PhMe (0.1) | 17 : 83 | |

H1 NMR ratio of products for reactions performed on 0.5 mmol scale.

Solvent Effects on the Au(I)-Catalyzed 1,2-Si Migration in Alkynes

Remarkably, it was found that the solvent effect could dominate over the counterion effect, as evidenced by a reverse regioselectivity observed in the Ph3PAuOTf-catalyzed cycloisomerization of 6 (Table 2, entries 2 vs 3 and 9 vs 10).20 Accordingly, when reaction was conducted in DCE solution, the preferred formation of 1,2-Si migration products was observed. However, when toluene was employed as a solvent, the 1,2-H migration products were the major ones. To shed light on these quite uncommon results,20 DFT calculations for evaluation of the solvent effects on the 1,2-H and 1,2-Si migrations were performed. DFT predictions for the Ph3PAuOTf-catalyzed reaction in DCE solvent were provided above (Scheme 6). The results for toluene solvent are outlined in Scheme 8. According to the calculated potential energy surfaces, employment of toluene solvent leads to the intermediate T-IN2 via 5-endo-dig cyclization of T-C with a reaction energy profile similar to that for DCE solvent. However, in the case of toluene solvent, there is no difference in activation energy barriers for α- (T-TS4) and β- (T-TS4) protonation pathways of furyl-Au complex T-IN2. Most importantly, while solvents do not affect the relative barriers of the subsequent 1,2-H- and 1,2-Si migrations from Au-carbene intermediates T-1 or C-1 much, they alter the stability of the dissociated noninteracting Au-carbene C-1 and TfO−-anion relative to the associated Au-carbene complex T-1. For instance, when the reaction is conducted in toluene solution, which has a lower polarity than DCE, the stabilization effects of the solvent on the charged species C-1 and TfO− are limited (compare relative energies of C-1 intermediates in Schemes 6 and 8). On the other hand, an alternative direct 1,2-Si migration from carbene T-1 via T-TS3 has 10.7 kcal/mol activation free energy barrier. Since complex T-1 does not undergo dissociation of the TfO−-ligand in toluene solution easily, its formation becomes reversible, forcing reaction to proceed via the α-protonation route T-IN2 – T-TS4 – T3, which is 3.9 kcal/mol lower in activation free energy than the direct 1,2-Si shift in T-1. The DFT calculations suggest that the Ph3PAuOTf-catalyzed cycloisomerization of 6 in toluene solvent should lead to the 1,2-H migration product 3, thus supporting the experimentally observed reversed regioselectivity of the reaction (Table 2, entries 2 vs 3 and 9 vs 10). In contrast to the above case, no solvent effect was observed in the DFT-simulated Ph3PAuSbF6-catalyzed reactions (Scheme 7). Thus, formation of the allene-Au complex H-5 and its cyclization into the Au-carbene H-1 were found to be more efficient than other possible processes in both DCE and toluene solvents. In addition, energies of the direct- or base-/SbF6−-assisted 1,2-H migrations were much higher than that of the 1,2-Si migration from H-1, regardless on the solvent (compare entries 7 and 8 in Table 2). Thus, the experimentally observed migratory preference (Table 2, entries 1, 7, 8, and 11) for the Ph3PAuSbF6-catalyzed reactions was in a good agreement with the performed DFT calculations. Finally, it is worth mentioning here that, in contrast to the cycloisomerization of alkynes 6, employment of solvents more polar than toluene did not affect the AuCl3-catalyzed cycloisomerization of allenyl ketone 4e (Table 1, entry 5).

Scheme 8.

Solvation Effect of Toluene on the Ph3PAuOTf-Catalyzed Reaction (R = H), Relative Free Energies in Toluene (ΔGTol) are in kcal/mol

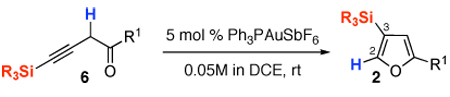

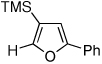

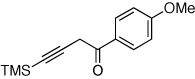

Synthesis of Furans via Au(I)-Catalyzed 1,2-Si Migration in Alkynes

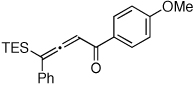

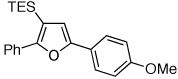

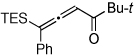

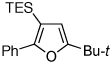

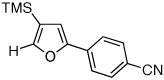

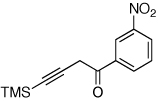

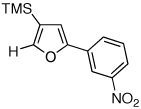

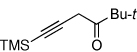

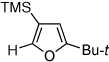

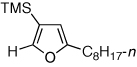

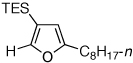

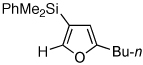

Next, we investigated the scope of the above 1,2-Si migration cascade reaction of alkynes (Table 3). Thus, cycloisomerization of a variety of 4-silyl homopropargylic ketones 6, possessing aryl- (entries 1, 2), primary- (entries 7–9), and tertiary (entry 6) alkyl groups, proceeded smoothly affording the C2-unsubstituted 3-silylfurans 2 as sole regioisomers in good to excellent yields (Table 3). It was found that alkynes bearing TMS- (entries 1–7), TES- (entry 8), as well as PhMe2Si (entry 9) groups could be successfully employed in this transformation. In the case of cycloisomerization of substrates 6 bearing electron-deficient aryl substituents (entries 3–5), 1,2-H shift competed with the 1,2-Si-migration, which resulted in formation of isomeric silylfurans 2 and 3 with good to high degrees of regioselectivity favoring 3-silylfurans 2. It was also demonstrated that a variety of functional groups such as methoxy (entry 2), bromo (entry 3), cyano (entry 4), and nitro (entry 5) could be tolerated under these reaction conditions.

Table 3.

Au-Catalyzed Cycloisomerization of Homopropargyl Ketones 6

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

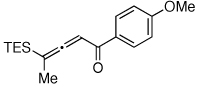

| Entry | Substrate | Product | 2, %a,b |

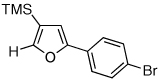

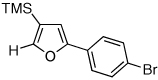

| 1 |  |

2f, 79 | |

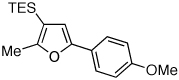

| 2 |  |

|

2g, 91 |

| 3 |  |

|

2h, 91c |

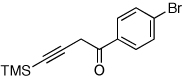

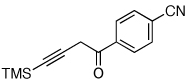

| 4 |  |

|

2i, 48d |

| 5 |  |

|

2j, 65e |

| 6 |  |

|

2k, 71f |

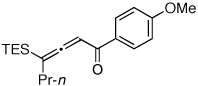

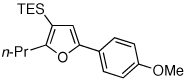

| 7 |  |

2l, 68 | |

| 8 |  |

2m, 77 | |

| 9 |  |

2n, 67 | |

Isolated yield of product for reactions performed on 0.5 mmol scale.

2f and 2l contained 8 and 6% of the corresponding desilylated furan, respectively.

14:1 ratio of 2h:3h.

10:1 ratio of 2i:3i.

8:1 ratio of 2j:3j.

GC Yield, 2k is a volatile compound.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a regiodivergent Au-catalyzed cycloisomerization of allenyl- and homopropargylic ketones into 2- and 3-silylfurans featuring 1,2-Si- or 1,2-H migrations in the common Au-carbene intermediate. The present methodology constitutes a general and efficient route for the synthesis of 3-silylfurans, important synthons,21 not easily available via the existing methodologies. Both experimental and computational results indicate that the 1,2-Si migration is kinetically more favored over the 1,2-shifts of H, alkyl-, and aryl groups in the β-Si-substituted Au-carbenes. However, according to the experimental data obtained for the cycloisomerization of homopropargylic ketones, counterion and solvent effects may reverse this migratory preference. The DFT calculations provided a rationale for this 1,2-migration regiodivergency. Accordingly, in the case of cationic Au-catalyst possessing non-nucleophilic SbF6−-counterion, DFT-simulated reaction affords 1,2-Si migration products exclusively via the initial propargyl-allenyl isomerization followed by the cyclization into the Au-carbene intermediate regardless on the solvent employed in the reaction. However, in the case of TfO−-counterion in nonpolar solvents, a pronounced counterion effect is observed. Thus, reaction occurs via the initial 5-endo-dig cyclization to give cyclic furyl-Au intermediate followed by a subsequent ipso-protiodeauration, which is kinetically more favorable than the generation of the common Au-carbene intermediate and leads to the formation of formal 1,2-H migration products. In contrast, when polar solvent is employed, β-to-Au protonation of the furyl-Au species, leading to Au-carbene intermediate, competes with the ipso-protiodeauration. Subsequent dissociation of the triflate ligand in the latter carbene in polar media due to efficient solvation facilitates formation of the 1,2-Si shift products. The above results of DFT calculations were validated by the experimental data. Finally, the present study highlights that the DFT calculations could efficiently complement experimental results, providing guidance for design of new transformations and offering better understanding of this chemistry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by Hundreds of Talents Program of CAS, Natural Science Foundation of China (20872105), and NIH of the US (GM-64444).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Computational and experimental details, and full citation of computational methods. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For selected reviews on transition metal-catalyzed transformations of alkynes and allenes, see: Alonso F, Beletskaya IP, Yus M. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:3079. doi: 10.1021/cr0201068. Kirsch SF. Synthesis. 2008:3183. Nakamura I, Yamamoto Y. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:2127. doi: 10.1021/cr020095i. Patil TN, Yamamoto Y. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3395. doi: 10.1021/cr050041j. Jiménez-Núñez E, Echavarren AM. Chem. Commun. 2007:333. doi: 10.1039/b612008c. Crone B, Kirsch SF. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:3514. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701985. Rubin M, Sromek AW, Gevorgyan V. Synlett. 2003:2265. Ma S. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2829. doi: 10.1021/cr020024j. Bates RW, Satcharoen V. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2002;31:12. doi: 10.1039/b103904k. Zimmer R, Dinesh CU, Nandanan E, Khan FA. Chem. Rev. 2000;100:3067. doi: 10.1021/cr9902796. Abu Sohel SM, Liu R-S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:2269. doi: 10.1039/b807499m. Majumdar KC, Debnath P, Roy B. Heterocycles. 2009;78:2661.

- 2.Hashmi ASK, Schwarz L, Choi J-H, Frost TM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:2285. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000703)39:13<2285::aid-anie2285>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou CY, Chan PWH, Che CM. Org. Lett. 2006;8:325. doi: 10.1021/ol052696c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.For selected recent reviews on Au-chemistry, see: Arcadi A. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3266. doi: 10.1021/cr068435d. Hashmi ASK. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:3180. doi: 10.1021/cr000436x. Gorin DJ, Toste FD. Nature. 2007;446:395. doi: 10.1038/nature05592. Li Z, Brouwer C, He C. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3239. doi: 10.1021/cr068434l. Fürstner A, Davies PW. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:3410. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604335. Jiménez-Núñez E, Echavarren AM. Chem. Rev. 2008;109:3326. doi: 10.1021/cr0684319. Widenhoefer RA, Han X. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:4555. Shen HC. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:3885. Shen HC. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:7847. Hashmi ASK, Hutchings GJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:7896. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602454. Belmont P, Parker E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009:6075. Hoffmann-Röder A, Krause N. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:387. doi: 10.1039/b416516k.

- 5.For recent reviews on furan synthesis, see: Brown RCD. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:850. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461668. Kirsch SF. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006;4:2076. doi: 10.1039/b602596j. Patil NT, Yamamoto Y. ARKIVOC. 2007:121. Hou XL, Cheung HY, Hon TY, Kwan PL, Lo TH, Tong SY, Wong HNC. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:1955. Hou X-L, Yang Z, Yeung K-S, Wong HNC. Prog. Heterocycl. Chem. 2008;19:176. Balme G, Bouyssi D, Monteiro N. Heterocycles. 2007;73:87. D'Souza DM, Muller TJJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1095. doi: 10.1039/b608235c. For selected recent examples on transition metal-catalyzed synthesis of furans, see: Zhang M, Jiang H-F, Neumann H, Beller M, Dixneuf PH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:1681. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805531. Xiao Y, Zhang J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009;351:617. doi: 10.1002/adsc.200900383. Pan Y-M, Zhao S-Y, Ji W-H, Zhan Z-P. J. Comb. Chem. 2009;11:103. doi: 10.1021/cc8001316. Zhang G, Huang X, Li G, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1814. doi: 10.1021/ja077948e. Xiao Y, Zhang J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1903. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704531. Shibata Y, Noguchi K, Hirano M, Tanaka K. Org. Lett. 2008;10:2825. doi: 10.1021/ol800966f. Ji K-G, Shen Y-W, Shu X-Z, Xiao H-Q, Bian Y-J, Liang Y-M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:1275. Barluenga J, Riesgo L, Vicente R, López LA, Tomás M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:13528. doi: 10.1021/ja8058342. Aurrecoechea JM, Durana A, Pérez E. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:3650. doi: 10.1021/jo800211q. Zhao L-B, Guan Z-H, Han Y, Xie Y-X, He S, Liang Y-M. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:10276. doi: 10.1021/jo7019465. Shu X-Z, Liu X-Y, Xiao H-Q, Ji K-G, Guo L-N, Qi C-Z, Liang Y-M. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007;349:2493. Peng L, Zhang X, Ma M, Wang J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:1905. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604299. Arimitsu S, Hammond GB. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:8559. doi: 10.1021/jo701616c. Zhang J, Schmalz H-G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:6704. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601252. Aponick A, Li C-Y, Malinge J, Marques EF. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4624. doi: 10.1021/ol901901m. Blanc A, Tenbrink K, Weibel J-M, Pale P. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:5342. doi: 10.1021/jo9008172. Blanc A, Tenbrink K, Weibel J-M, Pale P. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4360. doi: 10.1021/jo900483m. Yoshida M, Al-Amin M, Shishido K. Synthesis. 2009:2454. Egi M, Azechi K, Akai S. Org. Lett. 2009;11:5002. doi: 10.1021/ol901942t. Liu F, Yu Y, Zhang J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:5505. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901299. Suhre MH, Reif M, Kirsch SF. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3925. doi: 10.1021/ol0514101. Patil NT, Wu H, Yamamoto Y. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:4531. doi: 10.1021/jo050191u. Liu Y, Song F, Song Z, Liu M, Yan B. Org. Lett. 2005;7:5409. doi: 10.1021/ol052160r. Yao T, Zhang X, Larock RC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11164. doi: 10.1021/ja0466964. Hashmi ASK, Sinha P. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:432. Kel'in AV, Gevorgyan V. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:95. doi: 10.1021/jo010832v.

- 6.For Ag-catalyzed synthesis of furans via a formal 1,2-H shift in allenones, see: Marshall JA, Robinson ED. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:3450. Hashmi ASK. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:1581.

- 7.For selected examples on 1,2-shifts in the synthesis of aromatic heterocycles, see: Kim JT, Kel'in AV, Gevorgyan V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003;42:98. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390064. Sromek AW, Kel'in AV, Gevorgyan V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:2280. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353535. Schwier T, Sromek AW, Yap DML, Chernyak D, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9868. doi: 10.1021/ja072446m. Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5195. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701128. Dudnik AS, Sromek AW, Rubina M, Kim JT, Kel'in AV, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1440. doi: 10.1021/ja0773507. Gorin DJ, Davis NR, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:11260. doi: 10.1021/ja053804t. Li G, Huang X, Zhang L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:346. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702931. Takaya J, Udagawa S, Kusama H, Iwasawa N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:4906. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705517. Davies PW, Martin N. Org. Lett. 2009;11:2293. doi: 10.1021/ol900609f. Sromek AW, Rubina M, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10500. doi: 10.1021/ja053290y.

- 8.Xia Y, Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V, Li Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:6940. doi: 10.1021/ja802144t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.For selected examples, see: Danheiser RL, Carini DJ, Basak A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:1604. Danheiser RL, Kwasigroch CA, Tsai Y-M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:7233. Becker DA, Danheiser RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:389. Panek JS, Yang M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9868.

- 10.For selected examples of Si-shifts in the synthesis of aromatic heterocycles, see: Nakamura I, Sato T, Terada M, Yamamoto Y. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4081. doi: 10.1021/ol701951n. Seregin IV, Gevorgyan V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12050. doi: 10.1021/ja063278l. Danheiser RL, Stoner EJ, Koyama H, Yamashita DS, Klade CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4407.

- 11.(a) Creary X, Butchko MA. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:1115. doi: 10.1021/jo001112b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Creary X, Wang Y-X. Tetrahedron Lett. 1989;30:2493. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creary X, Butchko MA. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:112. doi: 10.1021/jo0106546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For selected examples of DFT studies in Au-chemistry, see: Nevado C, Echavarren AM. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:3155. doi: 10.1002/chem.200401069. Comas-Vives A, González-Arellano C, Corma A, Iglisias M, Sánchez F, Ujaque G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4756. doi: 10.1021/ja057998o. Nieto-Oberhuber C, López S, Muñoz MP, Cárdenas DJ, Buñuel E, Nevado C, Echavarren AM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:6146. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501937. Faza ON, López CS, Álvarez R, de Lera AR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:2434. doi: 10.1021/ja057127e. Straub BF. Chem. Commun. 2004:1726. doi: 10.1039/b404876h. Correa A, Marion N, Fensterbank L, Malacria M, Nolan SP, Cavallo L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:718. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703769. Nieto-Oberhuber C, Muñoz MP, Buñuel E, Nevado C, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:2402. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353207. Shi F-Q, Li X, Xia Y, Zhang L, Yu Z-X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15503. doi: 10.1021/ja071070+. Lemière G, Gandon V, Cariou K, Hours A, Fukuyama T, Dhimane A-L, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2993. doi: 10.1021/ja808872u. Nieto-Oberhuber C, Pérez-Galán P, Herrero-Gómez E, Lauterbach T, Rodríguez C, López S, Bour C, Rosellón A, Cárdenas DJ, Echavarren AM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:269. doi: 10.1021/ja075794x.

- 14.B3LYP/6-31G*(LANL2DZ for Au) method was used for all the calculations, and solvation effect was calculated by CPCM model.

- 15.See Supporting Information for details.

- 16.(a) Sheng H, Lin S, Huang Y. Synthesis. 1987:1022. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukuda Y, Shiragami H, Utimoto K, Nozaki H. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:5816. [Google Scholar]; (c) Shapiro ND, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:4160. doi: 10.1021/ja070789e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang W, Xu B, Hammond GB. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:1640. doi: 10.1021/jo802450n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.For examples of the proposed β-electrophilic attack on vinyl-gold, see: Huang X, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6398. doi: 10.1021/ja0717717. Luzung MR, Mauleón P, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12402. doi: 10.1021/ja075412n.

- 18.For review on counterion effects in Au-catalysis, see: Gorin DJ, Sherry BD, Toste FD. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:3351. doi: 10.1021/cr068430g. For selected examples, see: Lemière G, Gandon V, Agenet N, Goddard J-P, de Kozak A, Aubert C, Fensterbank L, Malacria M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:7596. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602189. Bhunia S, Liu R-S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16488. doi: 10.1021/ja807384a. Gorin DG, Watson IDG, Toste FD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:3736. doi: 10.1021/ja710990d. Kovács G, Ujaque G, Lledós A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:853. doi: 10.1021/ja073578i.

- 19.Simulation of a base in the Ph3AuOTf-catalyzed transformation using water cluster demonstrated that the 5-endo-dig cyclization path has the lowest energy profile, similarly to that for TfO−-counterion base. See Supporting Information for details.

- 20.For a single example of a solvent effect in the Au-catalyzed synthesis of pyrroles, see ref. 7i.

- 21.For review on silylfurans, see: Keay BA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1999;28:209.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.