Abstract

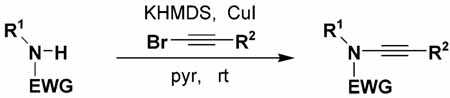

A general amination strategy for the N-alkynylation of carbamates, sulfonamides, and chiral oxazolidinones and imidazolidinones is described. A variety of substituted ynamides are available by deprotonation of amides with KHMDS followed by reaction with CuI and an alkynyl bromide.

We report herein a convenient and general method for the synthesis of ynamides via the copper-promoted coupling of amides with alkynyl bromides. Interest in the application of ynamides in organic synthesis has increased enormously in recent years.1 Considerably more robust than simple ynamines, ynamides are more easily stored and handled and tolerate a variety of conditions destructive to typical ynamines. Ynamides have thus emerged as versatile building blocks in a wide range of useful synthetic transformations including Pauson–Khand reactions,2 ring-closing metatheses,3 cycloadditions (and other ring-forming processes),4 and a variety of hydrometalation and hydrohalogenation reactions. 5,6

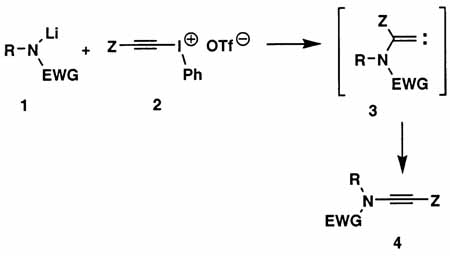

In connection with our studies on [4 + 2] cycloadditions of conjugated enynes7 and heteroenynes,8 we required an efficient method for the preparation of a wide range of ynamides, preferably via the direct alkynylation of carbamates, sulfonamides, and other simple amide derivatives. Initially we focused our attention on the reaction of metalated amides with alkynyl(phenyl)iodonium salts (eq 1).9 Stang10 and Feldman11 have shown that this process provides an excellent route to “push–pull”-type ynamides (4, Z = COR, CO2R, SO2Ar, etc.), and more recently Witulski and Rainier have extended this chemistry to the preparation of ynamides where Z = hydrogen, TMS, and phenyl.2a–d,4b Unfortunately, this approach is not applicable to the synthesis of ynamides in which Z is a simple alkyl group. The addition of soft nucleophiles to alkynyl(phenyl)iodonium salts is believed to proceed via the rearrangement of alkylidenecarbene intermediates of type 3, and the requisite 1,2-shift only is a facile process when Z is a hydrogen atom or trialkylsilyl or aryl group.12 In addition, whereas sulfonamide derivatives (e.g., 1, EWG = Ts) participate smoothly in the desired transformation, reactions of lactams,1a oxazolidinones,1a and acyclic carbamates13 proceed at best in low yield.

|

(1) |

The aforementioned limitations of alkynyl(phenyl)iodonium methodology prompted us to consider alternative and potentially more general approaches to the synthesis of the ynamides required for our studies. Recent developments in the laboratories of Buchwald and Hartwig have revolutionized methodology for carbon–nitrogen bond formation.14 Encouraged, in particular, by Buchwald’s recent success in achieving copper-catalyzed amidation of aryl halides,15,16 we turned our attention to the coupling of amide derivatives with readily available alkynyl halides.17

Initial results were disappointing. Application of Buchwald’s catalyst system15 to the coupling of acyclic carbamates with 1-bromo-2-phenylacetylene gave only trace amounts of the desired ynamide, with the predominant product being the 1,3-diyne generated from “homocoupling” of the alkynyl halide. During the course of our work, an important communication by Hsung and co-workers appeared reporting the successful application of Buchwald’s catalyst system15 to the N-alkynylation of oxazolidinones and lactams.18,19 Unfortunately, Hsung found these conditions to be less effective when applied to other amide derivatives, including acyclic carbamates and sulfonamides. Thus, under the Buchwald protocol ureas and sulfonamides undergo alkynylation in less than 10% yield. Somewhat better results are obtained in the case of carbamates; by terminating reactions at 30–50% conversion, Hsung and co-workers were able to isolate the desired ynamides, albeit in only 24–42% yield.

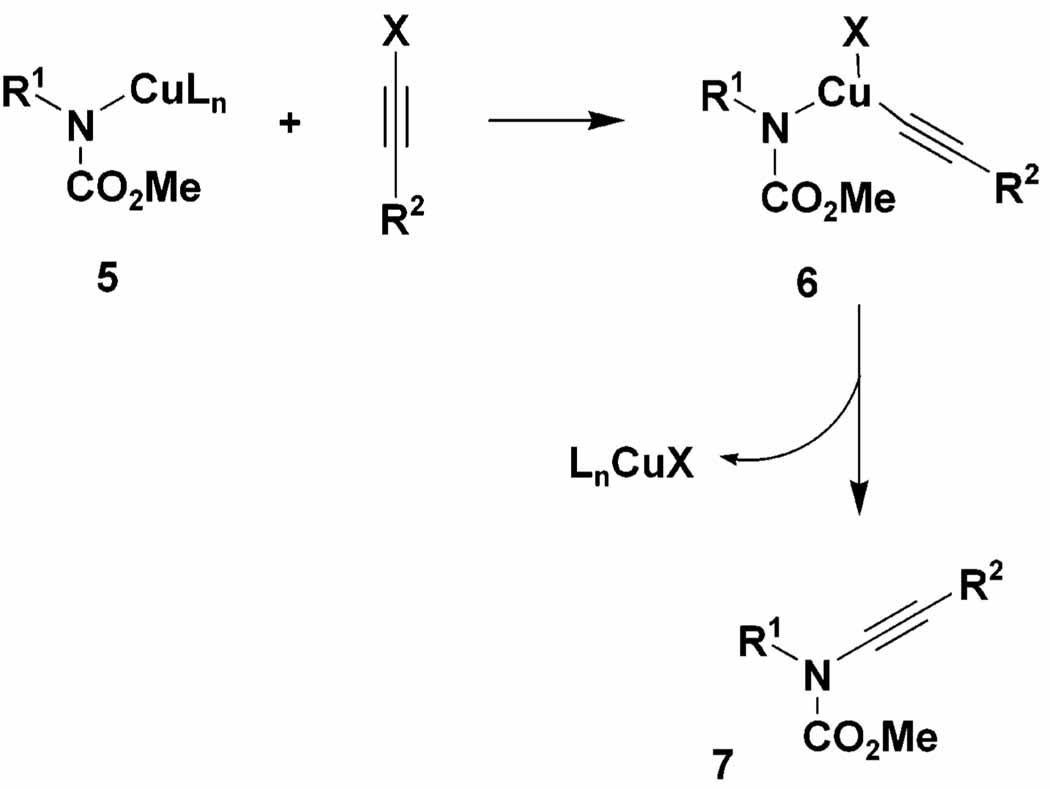

Our first success in effecting the desired alkynylation was achieved when we turned our attention to protocols in which complete conversion of the amide substrate to its copper derivative (e.g., 5) was carried out prior to addition of the alkynyl halide. Under these conditions, copper-promoted dimerization of the alkynyl halide is greatly diminished and the desired ynamides emerge as the major product of the reaction. As outlined in Scheme 1, oxidative addition of 5 to the alkynyl halide presumably generates a copper(III) intermediate 6, which then furnishes the desired ynamide by reductive elimination. Preforming the copper amide intermediate 5 maximizes the rate of its reaction with the alkynyl halide, allowing amidation to more effectively compete with the reaction of the alkynyl halide with copper salts in pathways leading to “homodimer” byproducts.

Scheme 1.

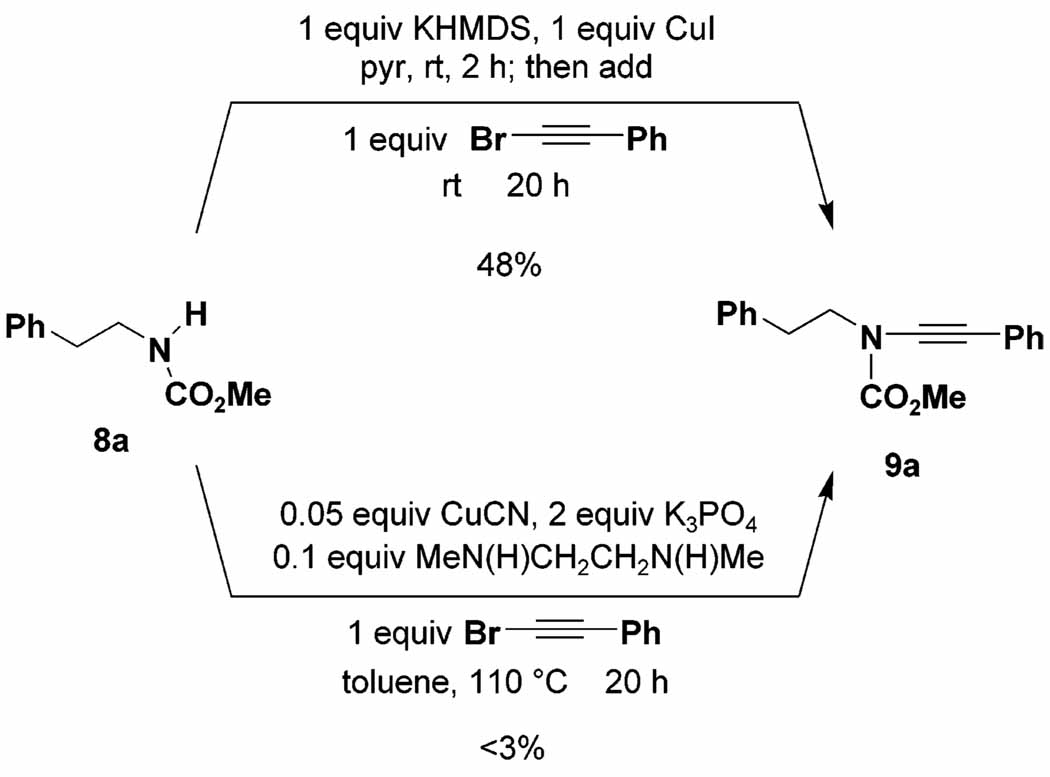

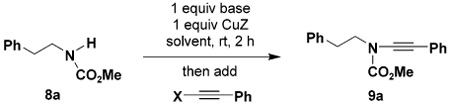

A systematic investigation of reaction variables using carbamate 8a as the test substrate led to the protocol outlined in Scheme 2. Under these conditions, 1-bromo-2-phenyl-acetylene undergoes amidation in 48% yield. Note that this bromo alkyne is especially prone to homocoupling, and in our hands the application of Buchwald’s catalyst system (as reported by Hsung18) afforded <3% of the desired ynamide 9a. Also notable is the observation that under our conditions the reaction proceeds smoothly at room temperature, in contrast to the elevated temperatures (110–150 °C) required in the Buchwald and Hsung amidations.

Scheme 2.

As summarized in Table 1, acetylenic iodides also participate in the alkynylation, whereas chloro alkynes are significantly less reactive and undergo amidation only upon heating and then in poor yield (entries 1–3). As expected, somewhat improved yields are observed when 2 equiv of alkynyl halides are employed to compensate for losses due to homocoupling (compare entries 2 and 9).20 Interestingly, pyridine proved to be the most effective solvent for the alkynylation reaction, clearly superior to the toluene–diamine ligand system (entry 11) employed by Buchwald15 and Hsung18 in their amidation studies. Under our optimal conditions (entry 9), the desired ynamide is obtained in 67% yield, with the yield increasing to 76% when the reaction is carried out on a multigram scale.21

Table 1.

Optimization of Alkynylation Conditionsa

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | base | CuZ | solvent | alkyne equiv, X |

yield (%)b |

| 1 | KHMDS | CuI | pyr | 1.0, I | 44 |

| 2 | KHMDS | CuI | pyr | 1.0, Br | 48 |

| 3 | KHMDS | CuI | pyrc | 1.0, Cl | 23 |

| 4 | KHMDS | CuI | DMF | 1.0, Br | 26 |

| 5 | n-BuLi | CuI | pyr | 1.0, Br | 0 |

| 6 | n-BuLi | CuI | DMSO | 1.0, Br | 20 |

| 7 | n-BuLi | CuTCd | DMSO | 1.0, Br | 24 |

| 8 | KHMDS | CuI | pyr | 0.6, Br | 40e |

| 9 | KHMDS | CuI | pyr | 2.0, Br | 67f |

| 10 | KHMDS | CuCN | pyr | 2.0, Br | 41 |

| 11 | KHMDS | CuI | tol, diamineg | 2.0, Br | 40 |

| 12 | KHMDS | CuI | pyr | 5.0, Br | 28h |

All reactions were carried out at rt for 20 h unless otherwise indicated. Concentration of 8a (0.200 g scale) was 0.15 M. Alkynes were added as benzene solutions.

Isolated yields of products purified by column chromatography.

Reaction at 75 °C.

Copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate.

Yield based on 1-bromo-2-phenylethyne.

Yield improved to 76% when scale increased to 2.0 g of 8a.

4.0 equiv of diamine ligand MeN(H)CH2-CH2N(H)Me.

Reaction for 90 h.

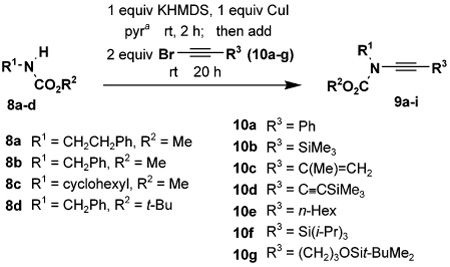

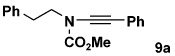

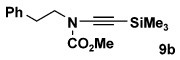

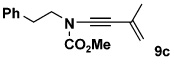

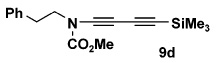

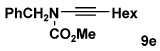

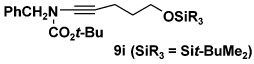

Table 2 details the scope of the N-alkynylation reaction as applied to acyclic carbamates. A broad range of substituted and functionalized alkynyl bromides participate in the reaction, including systems especially prone to homocoupling such as the bromo derivatives of conjugated enynes and diynes. Note also that these conditions provide access to ynamides 9e and 9f in yields considerably better than that reported by Hsung18 using the Buchwald catalyst system.

Table 2.

Synthesis of Ynamides by Alkynylation of Carbamates

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | carbamate | alkyne | ynamide | yield(%)b |

| 1 | 8a | 10a |  |

76 |

| 2 | 8a | 10b |  |

56 |

| 3 | 8a | 10c |  |

65 |

| 4 | 8a | 10d |  |

40 |

| 5 | 8b | 10e |  |

50 |

| 6 | 8b | 10f | 74 | |

| 7 | 8c | 10a |  |

42 |

| 8 | 8d | 10a | 61 | |

| 9 | 8d | 10g |  |

53 |

KHMDS was added as a solution in THF and the alkynyl bromide was added as a solution in benzene.

Isolated yields of products purified by column chromatography.

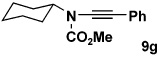

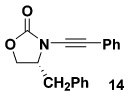

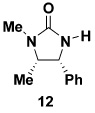

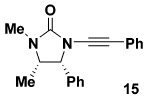

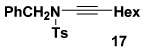

As summarized in Table 3, we have also found that our alkynylation protocol can be applied with good results to several other classes of amide derivatives. Notably, both imidazolidinones and sulfonamides undergo N-alkynylation in good yield. Both classes of amides are exceedingly poor substrates in alkynylations with the Buchwald catalyst system,18 and alkynyl sulfonamides such as 17 bearing alkyl substituents on the acetylene cannot be prepared via alkynyl-(phenyl)iodonium methodology (vide supra).

Table 3.

N-Alkynylation of Sulfonamides and Cyclic Carbamates and Ureasa

| entry | amide | alkyne | ynamide | yield(%)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

10a |  |

74 |

| 2 |  |

10a |  |

60 |

| 3 |  |

10a | 78 | |

| 4 |  |

10e |  |

42 |

Amide was treated with 1 equiv each of KHMDS and CuI in pyridine–THF (rt, 2 h); 2 equiv of bromo alkyne in benzene was then added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at rt for 20 h.

Isolated yields of products purified by column chromatography.

In summary, we have developed a general procedure for the copper-promoted N-alkynylation of a variety of amide derivatives that is complementary to the catalytic process recently introduced by Hsung and co-workers. Hsung’s protocol offers the advantage of requiring only a catalytic amount of copper salt but requires reaction at elevated temperatures (110–150 °C) and is not applicable to the efficient synthesis of ynamides from certain important classes of amides such as sulfonamides and acyclic carbamates. Our alkynylation reaction proceeds at room temperature and can be applied to a broad range of substrates but does require a full equivalent of (relatively inexpensive) copper iodide. Both methods have the advantageous feature of employing alkynyl bromides, which are easily prepared by bromination of terminal acetylenes, and thus represent more attractive alkynylating agents than alkynyl(phenyl)iodonium salts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the National Institutes of Health (GM 28273), Pharmacia, and Merck Research Laboratories for generous financial support. We thank Dr. Artis Klapars for helpful discussions concerning copper-mediated amidation chemistry.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and characterization data for all alkynylation reactions and ynamide products. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For reviews of the chemistry of ynamines and ynamides, see: Mulder JA, Kurtz KCM, Hsung RP. Synlett. 2003:1379. Zificsak CA, Mulder JA, Hsung RP, Rameshkumar C, Wei L-L. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:7575. Himbert G. In: Methoden der Organischen Chemie (Houben-Weyl) Part 3. Kropf H, Schaumann E, editors. Vol. E15. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag; 1993. pp. 3267–3443. Collard-Motte J, Janousek Z. Top. Curr. Chem. 1986;130:89.

- 2.(a) Witulski B, Stengel T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:489. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980302)37:4<489::AID-ANIE489>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Rainier JD, Imbriglio JE. Org. Lett. 1999;1:2037. [Google Scholar]; (c) Witulski B, Gössmann M. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1999:1879. [Google Scholar]; (d) Rainier JD, Imbriglio JE. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:7272. doi: 10.1021/jo001044t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Witulski B, Gössmann M. Synlett. 2000;12:1793. [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Saito N, Sato Y, Mori M. Org. Lett. 2002;4:803. doi: 10.1021/ol017298y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huang J, Xiong H, Hsung RP, Rameshkumar C, Mulder JA, Grebe TP. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2417. doi: 10.1021/ol020097p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Hsung RP, Zificsak CA, Wei L-L, Douglas CJ, Xiong H, Mulder JA. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1237. [Google Scholar]; (b) Witulski B, Stengel T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1999;38:2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Witulski B, Stengel T, Fernández-Hernández JM. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 2000:1965. [Google Scholar]; (d) Witulski B, Alayrac C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002;41:3281. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020902)41:17<3281::AID-ANIE3281>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Witulski B, Lumtscher J, Bergsträsser U. Synlett. 2003:708. [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Witulski B, Buschmann N, Bergsträsser U. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:8473. [Google Scholar]; (b) Minière S, Cintrat J-C. Synthesis. 2001;5:705. [Google Scholar]; (c) Minière S, Cintrat J-C. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:7385. doi: 10.1021/jo015824t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Timbart L, Cintrat J-C. Chem. Eur. J. 2002;8:1637. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20020402)8:7<1637::aid-chem1637>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Mulder JA, Kurtz KCM, Hsung RP, Coverdale H, Frederick MO, Shen L, Zificsak CA. Org. Lett. 2003;5:1547. doi: 10.1021/ol0300266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Also see: Tanaka R, Hirano S, Urabe H, Sato F. Org. Lett. 2003;5:67. doi: 10.1021/ol027209x. Mulder JA, Hsung RP, Frederick MO, Tracey MR, Zificsak CA. Org. Lett. 2002;4:1383. doi: 10.1021/ol020037j. Frederick MO, Hsung RP, Lambeth RH, Mulder JA, Tracey MR. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2663. doi: 10.1021/ol030061c.

- 7.Danheiser RL, Gould AE, Fernández de la Pradilla R, Helgason AL. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5514. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wills MSB, Danheiser RL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9378. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For reviews, see: Stang PJ. In: Modern Acetylene Chemistry. Stang PJ, Diederich F, editors. Weinheim: VCH; 1995. pp. 67–98. Stang PJ, Zhdankin VV. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:1123. doi: 10.1021/cr940424+. Zhdankin VV, Stang PJ. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:10927. Zhdankin VV, Stang PJ. Chem. Rev. 2002;102:2523. doi: 10.1021/cr010003+.

- 10.Murch P, Williamson BL, Stang PJ. Synthesis. 1994:1255. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldman KS, Bruendl MM, Schildknegt K, Bohnstedt AC. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:5440. [Google Scholar]

- 12.In the case where Z is an acyl or sulfonyl group, it is not clear if a 1,2-shift is involved or whether the mechanism proceeds via an addition–elimination pathway.

- 13.Our attempts to alkynylate acyclic carbamates (1, R = alkyl, EWG = CO2Me) with 2 (Z = SiMe3) produced the desired ynamides 4 in 15–20% yield.

- 14.For recent reviews, see: Muci AR, Buchwald SL. Top. Curr. Chem. 2002;219:131. Hartwig JF. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:2046. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980817)37:15<2046::AID-ANIE2046>3.0.CO;2-L.

- 15. Klapars A, Huang X, Buchwald SL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7421. doi: 10.1021/ja0260465. The Buchwald procedure for amidation of aryl bromides involves reaction with 0.01–0.1 equiv of CuI, 2 equiv of K3PO4, and 0.1 equiv of a diamine ligand in toluene or dioxane at 110 °C for 15–24 h.

- 16.Also encouraging were recent reports on the preparation of enamides and enamines via amidation and amination of vinyl halides and triflates. See: Ogawa T, Kiji T, Hayami K, Suzuki H. Chem. Lett. 1991:1443. Shen R, Porco JA. Org. Lett. 2000;2:1333. doi: 10.1021/ol005800t. Arterburn JB, Pannala M, Gonzalez AM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:1475. Barluenga J, Fernández MA, Aznar F, Valdés C. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 2002:2362. doi: 10.1039/b207524e. Kozawa Y, Mori M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:111. Lebedev AY, Izmer VV, Kazyul’kin DN, Beletskaya IP, Voskoboynikov AZ. Org. Lett. 2002;4:623. doi: 10.1021/ol0172370. Willis MC, Brace GN. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:9085.

- 17.For reviews of the chemistry of halo acetylenes, see: Hopf H, Witulski B. In: Modern Acetylene Chemistry. Stang PJ, Diederich F, editors. Weinheim: VCH; 1995. pp. 33–66. Brandsma L. Preparative Acetylenic Chemistry. New York: Elsevier; 1988.

- 18.Frederick MO, Mulder JA, Tracey MR, Hsung RP, Huang J, Kurtz KCM, Shen L, Douglas CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2368. doi: 10.1021/ja021304j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.For two early reports of the observation of copper-promoted formation of ynamines and ynamides from reactions of amine derivatives with terminal alkynes, see: Peterson LI. Tetrahedron Lett. 1968;9:5357. Balsamo A, Macchia B, Macchia F, Rossello A, Domiano P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1985;26:4141.

- 20.Interestingly, Hsung found that the yields of ynamides decrease when more than 1 equiv of alkynyl halide is employed under the Buchwald amidation conditions (which are catalytic in copper salt); see Supporting Information in ref 18.

- 21.Typical Experimental Procedure. A 250-mL, two-necked, round-bottomed flask equipped with a rubber septum and addition funnel fitted with a rubber septum and argon inlet needle was charged with carbamate 8a (1.951 g, 10.89 mmol) and 44 mL of pyridine. The solution was cooled at 0 °C while 12.0 mL of KHMDS solution (0.91 M in THF, 11 mmol) was added via syringe over 4 min. The reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 10 min, and then a solution of CuI (2.073 g, 10.89 mmol) in 22 mL of pyridine was added via cannula in one portion (10-mL pyridine rinse). The ice bath was removed, and the resulting solution was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. A solution of bromo alkyne 10a (36 mL, 0.60 M in benzene, 22 mmol) was then added via the addition funnel over 1 h, and the resulting mixture was stirred at room temperature for 20 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with 300 mL of Et2O and washed with three 100-mL portions of a 2:1 mixture of saturated NaCl solution and concentrated NH4-OH. The combined aqueous layers were extracted with three 75-mL portions of Et2O, and the combined organic layers were washed with 300 mL of saturated NaCl solution, dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated to provide 4.397 g of a dark red oil. Column chromatography on 120 g of silica gel (gradient elution with 0–3% EtOAc–hexanes) furnished 2.309 g (76%) of ynamide 9a as a yellow oil.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.