Molecular basis of the head-to-tail assembly of giant muscle proteins obscurin-like 1 and titin

Large filament proteins in muscle sarcomeres comprise many immunoglobulin-like domains that provide a molecular platform for self-assembly and interactions with heterologous protein partners. Sauer and colleagues now provide the molecular basis for the anti-parallel head-to-tail complex formed by the giant muscle proteins titin and obscuring-like 1. The interaction is mediated by a parallel intermolecular ß-sheet that represents a new assembly mechanism in sarcomeric filament proteins.

Keywords: muscle sarcomere, titin, obscurin, Ig-like domains, protein–protein complexes

Abstract

Large filament proteins in muscle sarcomeres comprise many immunoglobulin-like domains that provide a molecular platform for self-assembly and interactions with heterologous protein partners. We have unravelled the molecular basis for the head-to-tail interaction of the carboxyl terminus of titin and the amino-terminus of obscurin-like-1 by X-ray crystallography. The binary complex is formed by a parallel intermolecular β-sheet that presents a novel immunoglobulin-like domain-mediated assembly mechanism in muscle filament proteins. Complementary binding data show that the assembly is entropy-driven rather than dominated data by specific polar interactions. The assembly observed leads to a V-shaped zipper-like arrangement of the two filament proteins.

Introduction

Although the ultrastructure of muscle sarcomeres is highly ordered, there is increasing evidence of a dynamic exchange of many protein components between different sarcomere segments and the surrounding cellular structures (Lange et al, 2006; Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al, 2009). The giant muscle protein obscurin (Obs) provides a link between the longitudinal sarcomeric reticulum and the overall sarcomere architecture (Lange et al, 2009). Various Obs-binding sites for different isoforms of ankyrin 1 and ankyrin 2 from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, and for several signalling protein components and sarcomeric filament proteins, have been determined (reviewed by Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos et al, 2009). However, because Obs is found in different isoforms, and highly related proteins with virtually identical domain arrangements such as Obs-like 1 (Obsl1) have been identified, it is safe to assume that there is substantial functional diversity in the individual proteins.

Obs was discovered as a titin-binding protein and the respective binding sites were mapped to immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains (Z8 and Z9) from the Z-disk segment of titin, and to the carboxy-terminal Ig domains 58 and 59 of Obs (Young et al, 2001). Recently, a second M-band Obs–titin interaction site was found, allowing a remarkable head-to-tail assembly of these two giant filament proteins (Fukuzawa et al, 2008). Identification of this interaction has also allowed the reconciliation of molecular binding data with previous localization studies, which indicated that Obs is preferentially found in the sarcomeric M-band rather than in the Z-disk (Young et al, 2001; Bowman et al, 2007). Interestingly, at the Obs amino-terminus, next to the titin interaction site (Ig1), there are two additional Ig-domain-binding sites specifically for myosin-binding protein C slow, isoform 1 (Ackermann et al, 2009) and myomesin (Fukuzawa et al, 2008). Obsl1, which has high sequence similarity and domain organization with the N-terminal part of Obs, shows a broader expression pattern and is localized to different subcellular compartments, including the perinuclear region and intercalated discs (Geisler et al, 2007). Several Obsl1 mutations are associated with the primordial growth disorder, 3-M syndrome (Hanson et al, 2009), suggesting a functional spectrum beyond the known, muscle-specific functions of Obs.

In this paper, we focus on the molecular basis of the head-to-tail assembly of Obs/Obsl1 and titin. The atomic-resolution structure of Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) shows an unexpected, parallel β-sheet complex of the two Ig domains that forms a V-shaped, zipper-like assembly of the termini opposite the two filament proteins.

Results

Obsl1(Ig1) and titin(M10) fold into related Ig domains

We separately expressed and purified the N-terminal Ig domains of Obsl1 (residues 1–105) and Obs (residues 1–103), and the C-terminal Ig domain M10 from titin (residues 34,253–34,350). For convenience, we have renumbered the residues of the titin M10 domain to 3–100 in this paper. Purified Obs(Ig1)–titin(M10) and Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) domains form stable protein–protein complexes (supplementary Fig S1 online). To unravel the molecular basis of this complex formation, we crystallized the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex and solved the X-ray structure at 1.4 Å resolution with experimental phases from soaked bromide ions (Figs 1, 2; Table 1). The structure of Obsl1(Ig1) includes the complete domain fragment used for crystallization, except for the N-terminal residues (1–9) and two C-terminal residues (104 and 105). The structure of titin(M10) also comprises the complete domain fragment, except for the N-terminal residue Gly 1, and the C-terminal residue Ile 100.

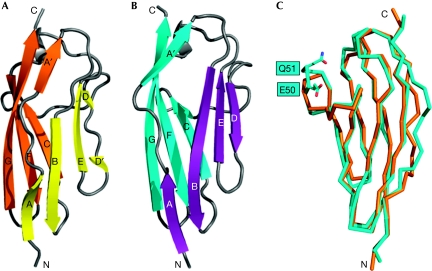

Figure 1.

Structures of Obsl1(Ig1) and titin(M10). The structures of the two Ig domains are shown as ribbon presentations. (A) The two β-sheets of Obsl1(Ig1) are in yellow and orange; (B) the two β-sheets of titin(M10) are in cyan and violet. The remaining structural elements are in grey. The β-strands and the termini are labelled. (C) Cα trace of superimposed Obsl1(Ig1) is shown in orange, and of titin(M10) in cyan. The loop inserted in titin(M10) is labelled. Obsl1, obscurin-like 1.

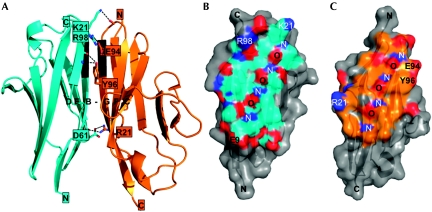

Figure 2.

Structure of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex. (A) Ribbon representation, showing Obsl1(Ig1) in orange and titin(M10) in cyan. The intermolecular β-sheet DEB-GFC is labelled. Those parts of interacting β-strands B from Obsl1(Ig1) and G from titin(M10) with a regular β-sheet hydrogen bond pattern are shown in black. Atoms of residues that are involved in specific intermolecular interactions are shown. Hydrogen bonds are indicated by dashed lines. Residues, the side chains of which are involved in these interactions, are labelled. (B,C) Semi-transparent surface presentation of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) interface: (B) titin(M10); (C) Obsl1(Ig1). The interfaces are highlighted in the colours used in (A). Surface-exposed oxygen and nitrogen atoms are shown in red and blue, respectively. The same residues as in (A) are labelled. In addition, the regular nitrogen–oxygen main-chain pattern of the two interacting β-strands, B and G, is labelled with ‘N' for nitrogen atoms and ‘O' for oxygen atoms. Obsl1, obscurin-like 1.

Table 1. X-ray structure determination.

| Native | LiBr derivative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray data collection | ||||

| Space group | P31 | P31 | ||

| Cell dimensions (Å) | a=60.9 | a=61.2 | ||

| c=42.1 | c=42.8 | |||

| Peak | Inflection | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.99184 | 0.91740 | 0.91706 | |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.40 (1.44–1.40) | 1.69 (1.73–1.69) | 1.90 (1.95–1.90) | |

| Number of measured reflectionsa | 113,955 | 106,892 | 156,326 | |

| Number of unique reflectionsa | 34,179 | 39,569 | 27,160 | |

| Multiplicitya | 3.3 | 2.7 | 5.8 | |

| Mean I/σ(I) | 20.6 (3.3) | 27.9 (5.5) | 41.9 (11.6) | |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (99.6) | 98.6 (96.3) | 98.0 (82.7) | |

| Anomalous completeness (%) | 98.0 (96.7) | 98.0 (87.2) | ||

| Anomalous multiplicity | 2.6 (2.4) | 5.7 (4.7) | ||

| Rmerge(%)b | 2.7 (33.0) | 4.1 (28.1) | 2.6 (13.4) | |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.21 | |

| Phasing | ||||

| Figure of merit (SHELXE) | 0.709 | |||

| Pseudo free CC (SHELXE) (%) | 72.39 | |||

| Number of sites | 15 | |||

| Refinement | ||||

| No. of reflections (test) | 34,177 (1,711) | |||

| Rcryst/Rfreec | 16.4/19.5 | |||

| Protein atoms | 1585 | |||

| Solvent atoms | 266 | |||

| Other atoms | 5 | |||

| Protein residues with alternative conformations | 25 | |||

| r.m.s.d. bond length (Å) | 0.006 | |||

| r.m.s.d. bond angles (°) | 1.1 | |||

| Values in parentheses correspond to those from the highest-resolution cell. | ||||

| aFor the peak and inflection point data sets, each reflection constituting Friedel pairs has been counted separately. | ||||

|

b | ||||

|

c | ||||

Each of the two protein fragments, titin(M10) and Obsl1(Ig1), are formed by related Ig domains (Fig 1). They superimpose with an r.m.s. deviation of 1.2 Å from 95 aligned residues (Fig 1C). Of these residue pairs, 21 (22%) are identical, thus showing a significant overall sequence similarity of the two domains (Fig 3). There is a peak level of similarity specifically for the sequence segment GEPxPxVxWxxGG, which comprises residues 31–43 from titin(M10) aligned with residues 39–50 from Obsl1(Ig1). The two Ig domains share the same I-set topology (Harpaz & Chothia, 1994) with two β-sheets, ABED and A′GFC. The first two-segmented β-strand, A–A′, which is interrupted by proline-containing sequences in each of the two Ig domains, crosses over the two β-sheets (Fig 1A,B).

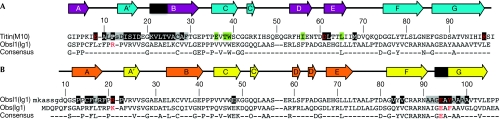

Figure 3.

Structure/sequence similarities of Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) and titin(M10). (A) Structure-based sequence alignment of titin(M10) and Obsl1(Ig1). (B) Sequence alignment of Obsl1(Ig1) and Obs(Ig1). Obsl1 residues that are not visible in the X-ray structure of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex are indicated in lowercase characters. The consensus of each of the two alignments indicates identical residues. The positions of all β-strands are indicated with arrows, using the colour codes as shown in Fig 1. In addition, those parts of β-strands B of titin(M10) and G of Obsl1(Ig1) with a regular intermolecular hydrogen bond pattern are shown in black (cf. Fig 2). Those residues that are involved in the interface of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex are highlighted: main-chain atoms only, grey background; side-chain atoms involved, black background; side chains with specific interactions, red characters. Residues that have been associated with tibial muscular dystrophy are shown on a green background (for details, see Discussion). Obs, obscurin; Obsl1, obscurin-like 1.

Interestingly, there are substantial structural differences in the formation of β-strand D, which is one of the two outer strands of the β-sheet ABED. In contrast to titin(M10), the equivalent β-strand in Obsl1(Ig1) is divided into two short, two-residue segments, D (residues 60–61) and D′ (residues 64–65). The fragmentation is probably due to the presence of Pro 63 between D and D′ (Fig 3); no proline is found in a similar position in titin(M10). In addition, there is a two-residue insertion (residues 50–51) in the loop connecting β-strands C and D in titin(M10).

Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) forms a parallel β-sheet

The structure of Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) shows how the two Ig domains form a complex with 1:1 stoichiometry and an overall interface of about 780 Å2 (Fig 2). The core of the interface is generated by a parallel, intermolecular β-sheet with DEB(titin)–GFC(Obsl1) topology (Fig 2A). Although the assembly-mediating β-strands B from titin(M10) and G from Obsl1(Ig1) are the longest in each of the two Ig domains (Fig 1A,B), regular β-sheet interactions are restricted to the N-terminal parts of these two β-strands (Fig 2A). By contrast, in titin(M10), the C-terminal part of β-strand B interacts with the N-terminal part of strand A (titin), and, in Obsl1, the C-terminal part of β-strand G interacts with the C-terminal part of strand A (Obsl1), which is referred to as A′ (Fig 1A,B). The Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) assembly is further supported by a limited number of hydrogen bonds, which include two salt bridges by Asn 61(titin)–Arg 21(Obsl1) and Arg 98(titin)–Gln 94(Obsl1) (Fig 2A). None of these residues are conserved in the other interaction partner (Fig 3A), thus rendering unlikely the self-assembly of either titin(M10) or Obsl1(Ig1) with identical topology. Under the experimental conditions in this study, neither of the two separate domains shows any tendency for oligomerization (supplementary Fig S1 online). In addition, fluorescence resonance energy transfer data are in agreement with the demonstrated antiparallel arrangement of the titin(M10)–Obsl1(Ig1) complex (supplementary Fig S2 online).

Obsl1(Ig1) and titin(M10) bind with micromolar affinity

To demonstrate the validity of our structural findings, we performed quantitative affinity measurements by isothermal microcalorimetry (ITC; Table 2; supplementary Fig S3 online). Both Obsl1 and Obs fragments bind with the same affinity, with a Kd of about 1 μM and stoichiometry of 1:1 to the titin(M10) domain (Table 2). The assembly is an entropy-driven process, with TΔS (T, temperature; ΔS, entropy difference) being close to 50 kJ/mol.

Table 2. Binding affinities measured by isothermal microcalorimetry.

| Titin(M10) | Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) | n | ΔH (kJ/mol) | −TΔS (kJ/mol) | ΔG (kJ/mol) | Kd (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | Obsl1 | 1.01±0.04 | 25±0.5 | 59.4±0.3 | −34.4±0.2 | 0.94±0.08 |

| Obs | 1.16±0.08 | 59.6±1.7 | 93.6±1.6 | −33.9±0.1 | 1.16±0.08 | |

| Titin(M10)–Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) interface mutants | ||||||

| R98E | Obsl1 | 0.96±0.05 | 11.5±0.5 | 45.3±0.9 | −34.4±0.2 | 0.92±0.07 |

| Obs | 1.19±0.05 | 26.7±1.4 | 63.4±1.3 | −33.7±0.2 | 1.22±0.07 | |

| D61R | Obsl1 | 0.95±0.06 | 12.6±2.0 | 42.0±1.6 | −29.4±0.6 | 28.5±4.8 |

| Obs | 1.01±0.06 | 54.1±4.8 | 80.0±4.4 | −25.9±0.4 | 7.2±1.5 | |

| V22P | Obsl1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Obs | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Titin(M10) disease mutants | ||||||

| L65P | Obsl1 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Obs | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| H55P | Obsl1 | 0.98±0.02 | 9.6±0.2 | 41.5±0.1 | −32.0±0.2 | 2.5±0.2 |

| Obs | 0.88±0.02 | 26.9±1.3 | 58.9±1.1 | −32.0±0.3 | 2.4±0.3 | |

| I56N | Obsl1 | 0.98±0.01 | 11.1±0.7 | 44.1±0.5 | −33.0±0.6 | 1.5±0.2 |

| Obs | 0.97±0.03 | 42.2±1.2 | 75.3±1.1 | −33.1±0.1 | 1.6±0.1 | |

| ND, not determined; Obs, obscurin; Obsl1, obscurin-like 1; wt, wild type. | ||||||

Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) provides a model for Obs

A sequence alignment of Obsl1(Ig1) and Obs(Ig1) shows that 38% (40/105) of all residues are identical (Fig 3B). The highest level of similarity is found at the YVCRARNAxGEAxAA motif from the C-termini of the two proteins, covering β-strand F and part of strand G. This sequence segment includes one of the two major assembly regions in the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex (Figs 2A,C, 3). The two Obsl1(Ig1) residues (Arg 21 and Gln 94) that contribute to intermolecular salt bridges in the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex are either similar or identical in the aligned Obs(Ig1) sequence (Fig 3). As the interaction observed for Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) was also reported for the equivalent N-terminal Obs domain (Fukuzawa et al, 2008), we also analysed the Obs(Ig1)–titin(M10) assembly by isothermal microcalorimetry with purified protein domains. The binding affinity and stoichiometry of this complex is the same as that of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex (Table 2).

To investigate further whether binding of Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) to titin(M10) is driven by common principles, we targeted a total of three residues from titin(M10), which are involved in the interface with Obsl1(Ig1)/Obs(Ig1): Val 22 from the interface segment of β-strand B (Fig 2A, in black), Asn 61 and Arg 98. The latter two residues contribute to intermolecular salt bridges in the structure of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex (Fig 2A). Correct folding of each of the mutants was verified by circular dichroism (supplementary Fig S4 online). The two charge-reversal titin(M10) variants showed either no effect (R98E) or only a mild effect (D61R) on Obsl1(Ig1)/Obs(Ig1) binding, indicating that the two observed intermolecular salt bridges are not essential for Obsl1/Obs–titin assembly. By contrast, the V22P variant of titin(M10) lost the ability to bind to Obsl1(Ig1)/Obs(Ig1). These observations suggest that, regardless of whether the interaction of titin(M10) is with Obsl1(Ig1) or Obs(Ig1), the assembly is driven by intermolecular β-sheet formation rather than by specific side-chain interactions. This finding is also supported by the consistently positive TΔS term in all measured isothermal microcalorimetry data, suggesting that binding is dominated by order and disorder terms (Table 2), possibly by displacement of a substantially ordered solvent shell at those β-strands that participate in Obsl1(Ig1)/Obs(Ig1)–titin(M10) assembly.

We therefore conclude that there is most likely no major functional difference in the ability of the N-terminal Ig domain from Obs or Obsl1 to bind to the C-terminal Ig domain M10 from titin. In agreement with the previous data (Fukuzawa et al, 2008), we therefore discuss further the biological implications of our findings on the basis of the assumption that the assembly of titin(M10) with Obs(Ig1) and Obsl1(Ig1) is virtually identical.

Discussion

Mechanistic implications of Obs/Obsl1–titin assembly

Both Obs/Obsl1 and titin present some of the largest sarcomeric filament proteins with particular requirements for molecular anchoring and assembly within muscle cells. One established mechanism in a number of sarcomeric filament proteins such as titin (N-terminus), filamin C (C-terminus) and myomesin (C-terminus) is Ig-domain-mediated self-assembly or hetero-assembly (Heikkinen et al, 2009; Pinotsis et al, 2009). Except for one known case of filamin C (Pudas et al, 2005), all characterized Ig-domain-mediated assemblies of sarcomeric filament proteins involve one or both of the β-strands B and G, which are generally the longest β-strands in each of the two β-sheets in I-set Ig domains (Harpaz & Chothia, 1994; Pinotsis et al, 2009). In the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex, however, both β-strands are shielded in each of the two protein components and function as potential interaction sites for either self-assembly or binding to other Ig-domain-containing proteins (Fig 2; cf. Fig 1A,B). By contrast, the potential second β-sheet interaction site, which is formed by β-strands C and D, is exposed in both protein domains of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex. However, at least for Obsl1, the options for further regular β-sheet-mediated assembly are restricted by fragmentation of β-strand D (Fig 1A).

Interestingly, several mutations of the titin Mex6 exon that have been shown to be associated with severe tibial muscular dystrophy are located in a sequence segment of titin(M10) that includes β-strands C–E (Hackman et al, 2002; Van den Bergh et al, 2003; Pollazzon et al, 2009; Fig 3; supplementary Fig S5 online). In yeast two-hybrid and pull-down experiments, only one titin(M10) variant (I56N) from a Belgian family did not impair Obs/Obsl1(Ig1) binding (Fukuzawa et al, 2008). We purified the three single-residue titin(M10) mutants (H55P, I56N and L65P) for characterization of folding by circular dichroism (supplementary Fig S4 online) and Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) binding by ITC (Table 2). In contrast to all other titin(M10) variants, the French family L65P mutant did not fold properly and, therefore, was unable to bind to Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1). This finding is supported by the structure of titin(M10), which shows that Leu 65 is located at the central β-strand E of the BED β-sheet (Fig 2A; supplementary Fig S5 online), and when mutated into proline, inevitably leads to disruption of the β-sheet. The other two mutants (H55P and I56N) fold as wild-type-titin(M10) and do not show significant effects in Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) binding and, thus, do not support that failure of Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) binding alone could cause a tibial muscular dystrophy disease phenotype. For another titin(M10) variant that was found to cause a serious disease phenotype in Finnish populations, in which residues 36–39 from β-strand C are mutated (supplementary Fig S5 online), it would be difficult to dissect the effects of single mutated residues. It is likely that Trp 39, which is a principal residue of the titin(M10) hydrophobic core, mutating into a charged residue might lead to a folding defect of the Ig domain.

Another unexpected finding in the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex is that the antiparallel arrangement of titin(M10) and Obsl1(Ig1) is generated by a parallel rather than an antiparallel intermolecular β-sheet (Fig 2A), which is without precedent (Pinotsis et al, 2009). The extent of the β-sheet observed is restricted to only three residues per β-strand, whereas the antiparallel β-sheets in other complexes from sarcomeric filament proteins are considerably more extensive in terms of the number of participating residues. This might explain the moderate binding affinity in the low micromolar range for both Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) and Obs(Ig1)–titin(M10) (Table 2). Therefore, although no experimental evidence is available yet, we cannot rule out the possibility that the titin–Obs/Obsl1 assembly might be in competition with other, potentially stronger binding partners.

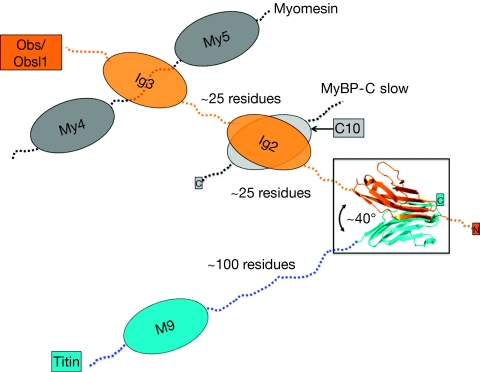

As the two assembly-mediating β-strands are in a parallel orientation with respect to each other in each of the two participating Ig domains, the overall arrangement of titin(M10) and Obsl1(Ig1) is that of a V-shape with an angle of about 40° (Fig 4). Because the two domains are from opposite termini of the two sarcomeric filament proteins, the titin C-terminus and the Obs/Obsl1 N-terminus, the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex functions as a zipper-like head-to-tail assembly module rather than as a connecting assembly module (Pinotsis et al, 2009). In the latter arrangement, the two assembled protein chains basically extend in opposite directions. Thus, in the absence of further ligands, it would be difficult to comprehend a potential filament-anchoring function for the observed Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) assembly. It is possible that such an additional anchoring function could be generated by the recently reported interactions of Obs domains Ig2 and Ig3 with myosin-binding protein C slow and myomesin (Fukuzawa et al, 2008; Ackermann et al, 2009; Fig 4). However, the mechanisms of these additional interactions remain elusive. Therefore, a principal future aim will be to investigate the structural–functional relationships of the neighbouring Obs/Obsl1–ligand complexes and the overall arrangement of these assemblies, in the context of the native sarcomeric M-line ultrastructure.

Figure 4.

Biological implications of the Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) assembly. The Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex has a V-shaped, parallel arrangement, generating a zipper-like assembly of the termini from titin and Obs/Obsl1. Colour codes are as shown in Fig 2. The neighbouring Obs/Obsl1 interactions with myomesin and MyBP-C (isoform 1) are indicated schematically. Approximate lengths of the domain-connecting loops are also indicated. MyBP-C, myosin-binding protein C; Obs, obscurin; Obsl1, obscurin-like 1.

Methods

Protein expression, purification and complex formation. Genes coding for titin(M10) (Q8WZ42, residues 34,253–34,350), Obsl1(Ig1) (O75147, residues 1–105) and Obs(Ig1) (Q5VST9, residues 1–103) were amplified by PCR from complementary DNA (titin, DKFZp451a172q; Obsl1, IMAGp958P2155Q; ImaGenes, Berlin, Germany) or synthetic DNA (Obs; MrGene, Regensburg, Germany). The genes were cloned into pET-M14, an in-house vector that carries an N-terminal 3C-protease cleavable polyhistidine tag.

All genes were expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 star (DE3) pRARE2 (Novagen). Cells were grown at 37°C in terrific broth medium supplemented with 100 μg/ml kanamycin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol. Overexpression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside at an OD600 of 3.0 and cells were harvested after continuous shaking at 20°C for 14 h.

The cells were lysed by sonication in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine) and the clarified lysate was applied to a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column. The bound protein was eluted from the column in an elution buffer (25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP). Affinity tags were cleaved overnight by addition of HRV14-3C protease in a mass ratio of 1:100 and the proteins were further purified to homogeneity by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75 16/60 pg column (GE Healthcare) in a buffer containing 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM TCEP. Folding of all titin(M10) mutants was analysed by circular dichroism. The spectra were recorded using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter, equipped with a thermostatically controlled water bath at 20°C, between 190 and 260 nm, and using a quartz cuvette with a 1 mm path length at 0.5 nm intervals. Protein concentrations were in the range of 0.11–0.25 mg/ml, in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). Each recorded spectrum represents three scans of a sample.

The Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex was formed by mixing the protein in a molar ratio of 1:1 in the same buffer and confirming by analytical gel filtration. For this purpose, 100 μl of the complex, Obs(Ig1)–titin(M10) or Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10), and separate protein components, titin(M10), Obs(Ig1) and Obsl1(Ig1), at concentrations of 130–300 μM, were injected onto a Superdex 75 HR 10/300 column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 10 mM Tris pH (8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM TCEP. Peak elution volumes were determined using the Unicorn software (GE Healthcare).

Crystallization conditions. The Obsl1(Ig1)–titin(M10) complex was crystallized by hanging-drop vapour diffusion at 20°C using a mixture of 2 μl protein solution (40 mg/ml) and 2 μl reservoir solution, containing 0.1 M imidazole (pH 8.0) and 2.0 M ammonium sulphate. Details of the X-ray structure determination are described in the supplementary information online. Crystallographic coordinates can be obtained from Protein Data Bank (accession code: 3KNB).

Determination of binding affinities. Before all ITC experiments, purified Obsl1(Ig1), Obs(Ig1) and titin(M10) samples were dialysed against 2 l of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2, 1 mM TCEP) at 4°C overnight. Titin(M10) was titrated as a ligand into the cell (V=1.42 ml) containing Obs(Ig1) or Obsl1(Ig1) at concentrations of 29–55 μM. The concentration of titin(M10) varied from 0.33 to 0.50 mM. The ligand was injected in volumes of 10 μl Obs(Ig1) or Obsl1(Ig1) in a total of 27 steps, resulting in a 1:2 molar ratio of Obs(Ig1)/Obsl1(Ig1) and titin(M10) at the end of each experiment. All titration experiments were performed at a constant cell temperature of 25°C in triplicate. To estimate the effects due to injection, mixing or dilution of the ligand, titin(M10) was injected under identical experimental conditions into the buffer. The absorbed heat measured in the last three data points was subtracted from the determined enthalpy values in all data sets. The enthalpy values on complex formation were calculated using ORIGIN software by integrating the observed peak area. Further binding parameters (stoichiometry, enthalpy and entropy) were obtained through curve fitting using ORIGIN.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by an FWF/DFG grant (P19060-B12) to M.W. and to Professor Kristina Djinovic-Carugo (University of Vienna).

Author contributions: F.S. and J.V. performed the experimental work. Y.-H.S. analysed the fluorescence resonance energy transfer data. M.W. and F.S. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Ackermann MA, Hu LY, Bowman AL, Bloch RJ, Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A (2009) Obscurin interacts with a novel isoform of MyBP-C slow at the periphery of the sarcomeric M-band and regulates thick filament assembly. Mol Biol Cell 20: 2963–2978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman AL, Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Hirsch SS, Geisler SB, Gonzalez-Serratos H, Russell MW, Bloch RJ (2007) Different obscurin isoforms localize to distinct sites at sarcomeres. FEBS Lett 581: 1549–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuzawa A, Lange S, Holt M, Vihola A, Carmignac V, Ferreiro A, Udd B, Gautel M (2008) Interactions with titin and myomesin target obscurin and obscurin-like 1 to the M-band—implications for hereditary myopathies. J Cell Sci 121: 1841–1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler SB, Robinson D, Hauringa M, Raeker MO, Borisov AB, Westfall MV, Russell MW (2007) Obscurin-like 1, OBSL1, is a novel cytoskeletal protein related to obscurin. Genomics 89: 521–531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackman P et al. (2002) Tibial muscular dystrophy is a titinopathy caused by mutations in TTN, the gene encoding the giant skeletal-muscle protein titin. Am J Hum Genet 71: 492–500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson D et al. (2009) The primordial growth disorder 3-M syndrome connects ubiquitination to the cytoskeletal adaptor OBSL1. Am J Hum Genet 84: 801–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpaz Y, Chothia C (1994) Many of the immunoglobulin superfamily domains in cell adhesion molecules and surface receptors belong to a new structural set which is close to that containing variable domains. J Mol Biol 238: 528–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heikkinen OK, Ruskamo S, Konarev PV, Svergun DI, Iivanainen T, Heikkinen SM, Permi P, Koskela H, Kilpelainen I, Ylanne J (2009) Atomic structures of two novel immunoglobulin-like domain pairs in the actin cross-linking protein filamin. J Biol Chem 284: 25450–25458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A, Ackermann MA, Bowman AL, Yap SV, Bloch RJ (2009) Muscle giants: molecular scaffolds in sarcomerogenesis. Physiol Rev 89: 1217–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange S, Ehler E, Gautel M (2006) From A to Z and back? Multicompartment proteins in the sarcomere. Trends Cell Biol 16: 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange S, Ouyang K, Meyer G, Cui L, Cheng H, Lieber RL, Chen J (2009) Obscurin determines the architecture of the longitudinal sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci 122: 2640–2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinotsis N, Abrusci P, Djinovic-Carugo K, Wilmanns M (2009) Terminal assembly of sarcomeric filaments by intermolecular beta-sheet formation. Trends Biochem Sci 34: 33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollazzon M et al. (2009) The first Italian family with tibial muscular dystrophy caused by a novel titin mutation. J Neurol 257: 575–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudas R, Kiema TR, Butler PJ, Stewart M, Ylanne J (2005) Structural basis for vertebrate filamin dimerization. Structure 13: 111–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh PY, Bouquiaux O, Verellen C, Marchand S, Richard I, Hackman P, Udd B (2003) Tibial muscular dystrophy in a Belgian family. Ann Neurol 54: 248–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P, Ehler E, Gautel M (2001) Obscurin, a giant sarcomeric Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor protein involved in sarcomere assembly. J Cell Biol 154: 123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.