Abstract

cdx4, a caudal-related homeodomain-containing transcription factor, functions as a regulator of hox genes, thereby playing a critical role in anterior–posterior (A-P) patterning during embryogenesis. In zebrafish, homozygous deletion of the cdx4 gene results in a mutant phenotype known as kugelig, with aberrant A-P patterning and severe anemia characterized by decreased gata1 expression in the posterior lateral mesoderm. To identify pathways that interact with cdx4 during primitive hematopoiesis, we conducted a chemical genetic screen in the cdx4 mutant background for compounds that increase gata1 expression in cdx4 mutants. Among 2640 compounds that were tested, we discovered two compounds that rescued gata1 expression in the cdx4-mutant embryos. The strongest rescue was observed with bergapten, a psoralen compound found in bergamont oil. Another member of the psoralen family, 8-methoxypsoralen, was also found to rescue gata1 expression in cdx4-mutant embryos. The psoralen compounds also disrupted normal A-P patterning of embryos. These compounds modify the cdx4-mutant phenotype and will help elucidate signaling pathways that act downstream or parallel to the cdx4-hox pathway.

Introduction

Because of their small size, optical clarity, and substantial fecundity, zebrafish embryos are excellent tools for testing the effects of chemicals in vivo in a vertebrate animal model. Several recent studies have proven the efficacy of chemical screening using zebrafish embryos, identifying small molecules regulating hematopoietic stem cell emergence as well as other developmental pathways.1–11 Because most developmental and signaling pathways are conserved between mammals and teleosts, chemicals discovered using this approach in zebrafish are likely to be applicable to humans. In addition, characterizing the mechanism of action of compounds discovered in this type of screen may lead to new insights into the function of a specific gene of interest.

To date, most of the published chemical screens using zebrafish have been performed using wild-type embryos. Another advantage of the zebrafish model is the availability of many mutant strains and transgenic strains with phenotypes analogous to human diseases, which can be utilized in chemical screens.12 Two such chemical modifier screens have been published to date. The first took advantage of a vascular mutant called gridlock, with a mutation in the hey2 gene.1 The second utilized the crash-and-burn mutant, with a defect in cell cycle regulation.2 Performing a chemical screen on a mutant background allows selection of compounds that rescue the phenotype of interest, with the hope of identifying modifying signaling pathways and potentially finding therapeutically relevant molecules.

The zebrafish has also proven to be an excellent model to study blood development, and forward genetic screens have generated numerous blood mutants that have advanced the understanding of developmental hematopoiesis.13,14 As in mammals, hematopoiesis in the zebrafish consists of two waves. The primitive or embryonic wave occurs during the first 24 h postfertilization, specifying blood cell development in the anterior lateral mesoderm (ALM) and posterior lateral mesoderm (PLM). Blood cells born in the ALM region become myeloid cells, expressing the myeloid transcription factor pu.1, whereas the PLM region gives rise to some myeloid cells but mostly erythroid cells, a process that is governed by the transcription factor gata1.15–17 Definitive hematopoiesis starts later and generates hematopoietic stem cells, which will produce all blood cell types for the animal's lifetime.

The zebrafish mutant kugelig, with a deletion in the caudal-related homeobox gene cdx4, has aberrant anterior–posterior (A-P) patterning and hox gene expression, in addition to severe anemia due to failed specification of PLM cells into gata1+ erythroid cells.18 At the 10-somite stage, cdx4 mutants show decreased expression of gata1 in the PLM. This defect in primitive hematopoiesis can be partially rescued by 4-diethylamino benzaldehyde (DEAB), an inhibitor of retinoic acid (RA) biosynthesis19 (J.L.O. de Jong and L.I. Zon, unpublished data).

In this study, we conducted a chemical screen using cdx4-mutant embryos to seek new pathways that interact with cdx4 during primitive hematopoiesis. A total of 2640 compounds were tested, revealing two that rescued gata1 expression in cdx4-mutant embryos. Bergapten, also known as 5-methoxypsoralen (5-MOP), produced the most robust rescue of all the compounds tested. Bergapten was found to have effects similar to DEAB, including changes in A-P patterning. Neither bergapten nor DEAB significantly alters the expression of other blood genes including fli1, scl, and pu.1 in wild-type embryos. However, similar to the rescue of gata1 expression, bergapten and DEAB both rescue the expression of pu.1 in cdx4-mutant embryos. The related compound 8-methoxypsoralen (8-MOP) was also shown to affect A-P patterning and to rescue loss of gata1 and pu.1 in cdx4-mutant embryos. This indicates that psoralen compounds may interact with cdx4-hox downstream pathway or a parallel pathway.

Methods

Zebrafish care and mutant lines

Wild-type AB strain, and kugelig heterozygote zebrafish carrying the cdx4-mutant allele were bred and maintained using standard zebrafish husbandry.20 Developmental staging was done by embryo morphology.21 All zebrafish experiments and procedures were performed as approved by the Children's Hospital Boston Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Chemical library

Compounds from the known bioactives collection (NINDS Custom Collection 2, Biomol 3, Prestwick 1, and Biomol 4) were obtained from the Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology (ICCB) Longwood screening facility at Harvard Medical School. A total of 2640 compounds were screened. The ICCB compounds were stored at −20°C, dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in desiccated storage containers in 384-well plates. All chemical transfers were performed robotically. One microliter of each compound dissolved in 100% DMSO was diluted into 300 μL of embryo medium (E3 fishwater)20 with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) and 1% DMSO in a 48-well nontissue culture-treated plate (Falcon). In addition, each 48-well plate contained blank wells used as negative control wells (E3 water with 1% DMSO and 1% Pen/Strep) and positive control wells with 20 μM DEAB.

Chemicals

Stock solutions were prepared as follows: DEAB (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved at 1 M concentration in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich). Bergapten (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in acetone at 5 mM concentration. 8-MOP (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in acetone at 5 mM concentration. 5-(4-Phenoxybutoxy)psoralen (PAP-1) (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO at 7.25 mM concentration. All stock solutions were stored at −20°C, and fresh dilutions of working concentrations were prepared on the day of experiments.

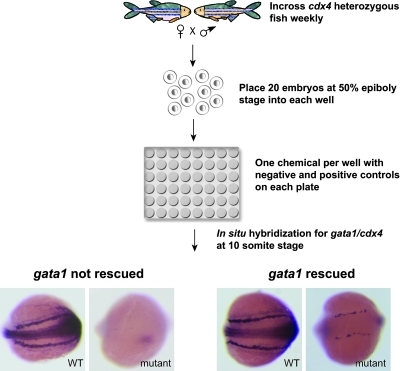

Screening procedure

cdx4 heterozygous fish were mated every 1–2 weeks to generate embryos for screening. Males and females were set up overnight and kept separated until morning when they were allowed to mate and the embryos were collected. Embryos were kept at 28°C until treatment with chemicals. When embryos reached the dome stage, dead and unfertilized embryos were discarded, and healthy stage-synchronized embryos were pooled. At the 50% epiboly stage, approximately 20 embryos per well were arrayed in the 48-well plates containing one compound per well. As cdx4 affects early mesodermal patterning, embryos were treated from the beginning of gastrulation (50% epiboly stage) until the 10-somite stage to find compounds that could overcome the need for cdx4 in specifying primitive blood cells. Following the incubation at 21°C for approximately 14–15 h, embryos were dechorionated by incubation in pronase 167 μg/mL (Roche) for 6 min. They were then washed repeatedly with E3 water to remove the chorions and the treatment chemicals and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for whole-mount in situ hybridization with gata1 and cdx4 riboprobes (Fig. 1). The bilateral mRNA expression of gata1, a transcription factor critical for erythroid development, was used as the readout for the screen, with positive hits showing increased gata1 in cdx4-mutant embryos. cdx4-mutant embryos were easily identified in each well by the lack of cdx4 RNA expression in the midline and the tail bud (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Screen design. cdx4 heterozygous adult fish were incrossed weekly to generate embryos for the chemical screen. Chemicals from the Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology library were transferred by robotics from 384-well plates to 48-well plates. Each plate contained negative (1% DMSO) and positive (20 μM DEAB) control wells. About 20 synchronized embryos at 50% epiboly stage were placed manually into each well of the 48-well plates. Once the embryos reached the 10-somite stage, they were fixed and whole-mount in situ hybrization was performed with both gata1 and cdx4 riboprobes. Each well was examined and scored manually. A posterior view of representative embryos is shown, with anterior to the left and posterior to the right. cdx4-mutant embryos were identified by lack of cdx4 expression. In most wells, cdx4-mutant embryos had little or no gata1 expression. The wells with increased gata1 expression in the cdx4-mutant embryos were scored as a “rescue.” DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DEAB, 4-diethylamino benzaldehyde; WT, wild type. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/zeb.

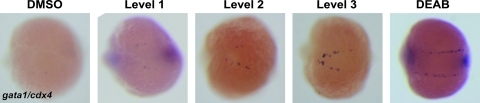

After in situ hybridization, embryos were transferred into 24-well plates to minimize optical distortion from the smaller wells in the 48-well plates. Each well was scored manually using a dissecting microscope. To minimize the influence of plate-to-plate variation of the scoring results, two negative control wells (E3 + 1% DMSO and 1% Pen/Strep) and two positive control wells (20 μM DEAB) were included in each 24-well plate. For each well, the number of mutant embryos was recorded, along with the level of gata1 expression relative to the positive and negative controls for that plate. If the expression was deemed to be increased in comparison to the negative control wells, the level of increase was scored based on the intensity of gata1 staining in the mutant embryos and the percentage of total mutants with increased gata1. We assigned each compound to a distinct level of rescue (Fig. 2). Level 3 compounds had the strongest gata1 expression with >50% of mutant embryos uniformly displaying as much or more gata1 expression as the positive controls from the same plate. Level 2 compounds had >50% of mutant embryos with increased gata1 compared with negative controls, but the level of gata1 expression was mixed, with some embryos displaying a high level of gata1 expression and others less. Finally, level 1 compounds had <50% of mutant embryos with increased gata1 and a generally weakly increased degree of gata1 expression when compared with negative controls (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Scoring system for rescued embryos. The level of gata1 rescue was determined by the percentage of rescued mutant embryos in each well and by the intensity of gata1 expression in these embryos in comparison to the negative and positive control wells for each individual plate. DMSO vehicle was the negative control, and 20 μM DEAB was the positive control. Representative mutant embryos are shown after in situ hybridization for gata1 and cdx4 expression. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/zeb.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Whole mount in situ hybridizations were performed as previously described using antisense riboprobes labeled with digoxigenin and detected with antidigoxigenin antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase.22 The following antisense riboprobes were generated as described: cdx4, hoxa9a, hoxb7a,18 fli1,23 gata1,17 krox-20,24 myoD,25 pu.1,16 and scl.26 The in situ protocol was performed using the Biolane™ HTI machine (Holle & Huttner AG).

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from fin clips or whole embryos as previously described.27 cdx4 heterozygous fish and homozygous mutant embryos were genotyped as previously described.18

Results

Chemical screen to identify cdx4 modifier phenotype

A total of 2640 compounds from the known bioactive collection of the ICCB were tested. This same panel of compounds had been tested previously in our laboratory during a screen to identify small molecules that alter runx1 and c-myb expression during definitive hematopoiesis.5,10 Each compound was tested individually in a single well, because preliminary experiments with pooled compounds yielded high levels of toxicity (data not shown). When tested individually in our assay, 42 compounds were noted to cause developmental delay (1.6%), 24 were teratogenic (0.9%), and 72 were toxic to embryos (2.7%), resulting in death of all or most embryos in the well.

A total of 5 compounds were scored as level 3 hits, 16 compounds as level 2 hits, and 18 compounds as level 1 hits. All the level 2 and level 3 compounds and most of the level 1 compounds were purchased and a range of concentrations were retested in the gata1/cdx4 in situ hybridization assay. Two of the level 3 compounds, bergapten and asarylaldehyde, had reproducible rescue of gata1 expression in cdx4 mutants, whereas none of the results with level 1 or 2 compounds could be repeated convincingly.

A small percentage (0.9%) of chemicals tested had only wild-type embryos in the well, and thus no cdx4 mutants to score. On the unlikely possibility that the chemical exposure had completely rescued the cdx4-mutant phenotype rendering the cdx4-mutant animal indistinguishable from the wild-type, the embryos in these otherwise unscorable wells were genotyped to confirm they were all wild type or heterozygous for the mutant cdx4 allele. In all cases no homozygous mutant embryos with a wild-type phenotype were identified. Each of these compounds were then retested, and none had cdx4-mutant embryos with increased gata1 expression on subsequent testing.

Bergapten rescues gata1 expression in cdx4-mutant embryos but has minimal effect on the expression of other posterior mesodermal genes

Bergapten and asarylaldehyde were found to increase gata1 expression in cdx4-mutant embryos. We decided to focus on bergapten only, because asarylaldehyde had a very simple chemical structure, such that we could not identify related compounds to study. Bergapten, also known as 5-MOP, is a member of the psoralen family, which is found in bergamont oil.28 Psoralen family members have been utilized in the treatment for psoriasis and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, in combination with ultraviolet A (UVA) phototherapy (reviewed in Ref.29). The original concentration of bergapten in the screening well was estimated to have been approximately 30 μM. When a serial dilution of purchased bergapten was tested, maximal rescue of gata1 expression was observed at 33 μM, whereas treatment with 100 μM bergapten was toxic (Fig. 3A). In one representative experiment, 36% of the embryos treated with 100 μM bergapten were dead by the 10-somite stage (24/67), and 51% of the live embryos were dysmorphic (22/43).

FIG. 3.

Bergapten increases gata1 and pu.1 in cdx4-mutant embryos. All embryos are displayed with anterior to the left and posterior to the right. (A) cdx4 heterozygous adults were incrossed, and the resulting embryos were treated with varying doses of bergapten. Bergapten rescues gata1 expression (level 3) in the cdx4-mutant embryos, and this rescue is most effective at 33 μM. Whole-mount embryos at the 10-somite stage are displayed from a representative experiment. (B) cdx4 heterozygous adults were incrossed, and the resulting embryos were treated with DMSO vehicle control, 20 μM DEAB, or 30 μM bergapten. Flatmounted embryos at the 10-somite stage are shown. WT embryos and cdx4 mutants stained with pu.1 were confirmed by genotyping. Bergapten does not change the expression pattern of mesodermal genes fli1, scl, and pu.1 in WT embryos. In cdx4-mutant embryos, however, pu.1 expression is rescued in the posterior lateral mesoderm when either DEAB or bergapten is applied. Ber, bergapten. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/zeb.

To determine whether bergapten also affected other posterior tissues in the developing embryo, we examined the expression patterns of multiple mesodermal genes, including fli1, scl, and pu.1, in cdx4-mutant embryos treated with bergapten (Fig. 3B). In wild-type embryos, all of these genes are expressed in the ALM and PLM from the three-somite stage.23,26 fli1 marks vascular progenitors, whereas scl is expressed by both vascular and hematopoietic cells, and pu.1 is expressed by committed myeloid cells.15–16 The cdx4-mutant embryos have decreased expression of fli1 and scl in the PLM, and almost normal expression in the ALM. When treated with either DEAB or bergapten, there was no observable difference between the expression level of fli1 or scl in untreated wild-type embryos and embryos treated with DEAB or bergapten. Although the overall expression domain in the posterior mesoderm is shorter in the cdx4-mutant embryos treated with DEAB or bergapten, the intensity of expression is unchanged compared with untreated cdx4 mutants (Fig. 3B). In contrast, the expression of pu.1 is absent in the PLM of cdx4 mutants and appears relatively normal in the ALM. When treated with bergapten, cdx4-mutant embryos have increased expression of pu.1 in the PLM, similar to the rescue effect observed with gata1 expression. This same result is also evident after incubation with DEAB. This indicates that both DEAB and bergapten may expand primitive blood development by acting upon a common erythromyeloid progenitor, but these compounds do not appear to act upon hemangioblasts.

Bergapten disrupts A-P patterning

The morphology of the gata1+ stripes in the posterior mesoderm was similar in both DEAB-treated and bergapten-treated embryos, but the anterior portion did not merge toward the midline as seen in wild-type embryos at the 10-somite stage. We hypothesized that bergapten and DEAB would have similar effects on A-P patterning overall. Having observed that posterior expression of gata1, pu.1, scl, and fli1 had similar patterns for embryos treated with either DEAB or bergapten, we examined anterior patterning more closely by studying the expression of krox-20 and myoD. As krox-20 stains rhombomeres 3 and 5 in the hindbrain, whereas myoD stains the somites, this allowed a measurement of the distance between the hindbrain and the most anterior somite pair. Previous studies have shown this distance between krox-20 and myoD to be highly sensitive to RA concentration, as demonstrated in mutants with disrupted RA signaling.30 Likewise, treatment of wild-type embryos with DEAB is reported to have a similar effect.7 When treated with DEAB, the gap between krox-20 and myoD expression disappears, indicating defects in the posterior hindbrain. This result is identical for embryos treated with 33 μM bergapten, whereas a clear gap is noted in the untreated control embryos (138.6 ± 7.6 μm) (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that bergapten and DEAB have similar effects on A-P patterning. When the same krox-20–myoD assay was conducted with embryos obtained from an incross of cdx4 heterozygous animals, embryos were found to lose the gap between krox-20 and myoD regardless of their genotype. However, in the cdx4-mutant embryos, krox-20 expression overlapped with that of somite 1 and 2, indicating that A-P patterning in the cdx4-mutant embryos was more severely affected compared with their siblings (Supplemental Fig. S1, available online at www.liebertonline.com). As DEAB is known to inhibit RA biosynthesis,19,31 it is possible that bergapten may also inhibit the RA pathway through an unknown mechanism.

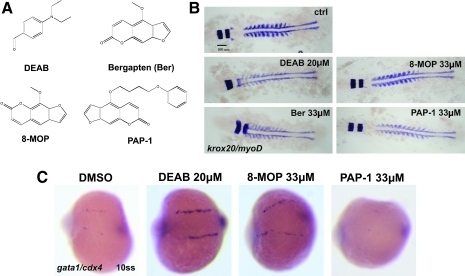

FIG. 4.

Bergapten and other psoralen compounds affect anterior–posterior patterning. (A) Chemical structures of the compounds tested. (B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of WT AB embryos with krox-20 and myoD riboprobes. Whole-mount 10-somite stage embryos are shown from a representative experiment. The average distance between krox-20 and myoD in control embryos is 138.6 μm (±7.6 μm). The bergapten-treated embryos lose the gap between krox-20 and myoD, similar to DEAB-treated embryos. 8-MOP also affects the distance, but to a lesser degree (85.8 ± 4 μm). In contrast, PAP-1 does not affect this distance. (C) cdx4 heterozygous adults were incrossed, and the resulting embryos were treated with DMSO vehicle control, 20 μM DEAB, 33 μM 8-MOP, or 33 μM PAP-1. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was done with gata1 and cdx4 riboprobes at the 10-somite stage. 8-MOP robustly rescues gata1 expression in the cdx4-mutant embryos, whereas PAP-1 does not rescue. ss, somite stage; PAP-1, 5-(4-phenoxybutoxy)psoralen; 8-MOP, 8-methoxypsoralen. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/zeb.

8-MOP has similar effect as bergapten on gata1 expression, whereas PAP-1 does not

To determine if structurally similar psoralen compounds related to bergapten may have similar effects on hematopoiesis, 8-MOP and PAP-1 were tested in these same assays. Like bergapten, 8-MOP is used clinically to treat psoriasis and has DNA intercalating activity (reviewed in Ref.29). In contrast, PAP-1 is a potassium channel blocker, which is also used for clinical treatment of psoriasis, but with decreased phototoxicity due to bulky side groups attached to the psora ring32 (Fig. 4A).

We first tested if 8-MOP and PAP-1 also affect A-P patterning in wild-type embryos using the krox-20–myoD assay mentioned earlier. As expected, 8-MOP disrupts the posterior hindbrain for all doses tested, with maximal effect at 33 μM, albeit at lesser degree when compared with bergapten-treated embryos (average krox-20/myoD distance of 8-MOP-treated embryos = 85.8 ± 4 μm) (Fig. 4B; data not shown). In contrast, PAP-1 does not affect the distance between krox-20 and myoD (average distance = 141.2 ± 13 μm). When we examined the ability of 8-MOP and PAP-1 to rescue gata1 expression in cdx4-mutant embryos, 8-MOP increased gata1 expression at 33 μM, whereas PAP-1 did not (Fig. 4C). Overall, 8-MOP seems to act similarly to bergapten, as the effect of 8-MOP on other mesodermal lineage gene expressions, including scl, fli1, and pu.1, was identical to bergapten (Supplemental Fig. S2, available online at www.liebertonline.com).

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a chemical modifier screen in the cdx4 mutant background to identify pathways that interact with the cdx4 pathway in regulating primitive hematopoiesis. On screening a library of known bioactive compounds, bergapten, a member of the psoralen family, was found to increase gata1 expression in cdx4-mutant embryos. Further investigation of additional psoralen family members, including 8-MOP and PAP-1, revealed that 8-MOP acts similarly to increase gata1, albeit less robustly than bergapten. In addition to the gata1 rescue, these compounds also affected A-P patterning, particularly of the hindbrain, as evidenced by the decreased distance between krox-20 and myoD expression pattern in embryos treated with psoralen family members. This pattern was reminiscent of embryos treated with an inhibitor of RA biosynthesis, as well as genetic mutants with disruption in RA signaling.30,33

Inhibitors of RA signaling, such as DEAB, have been shown previously to increase gata1 expression during primitive hematopoiesis in zebrafish (J.L.O. de Jong and L.I. Zon, unpublished data). Taken together, these results suggest that the mechanism of gata1 rescue by psoralen compounds may also result from inhibitory effects on the RA pathway. No direct interaction is known between psoralens and retinoids, although both are used to treat diseases of the skin, such as psoriasis. Case reports suggest that there may be an additive or even synergistic effect when using both retinoids and psoralens with UVA to treat scleroderma.34 Another report has shown that psoralens with UVA increase the expression of CYP2S1, a cytochrome P450 enzyme that is predominant for the metabolism of RA in the skin.35 If an analogous mechanism were present in our assay, then bergapten may induce the expression of cyp26a1 or another metabolizing enzyme in the developing zebrafish, thereby decreasing the effective RA concentration by enhanced biodegradation.

To test if bergapten disrupts RA signaling, an epistasis experiment was conducted by simultaneously treating wild-type embryos with both bergapten and RA. The expression pattern of krox-20 and myoD was the same for embryos treated with RA alone (data not shown), indicating that bergapten does not suppress exogenous RA signaling, and suggesting that if bergapten does affect the RA pathway, it most likely functions upstream of raldh2, the rate-limiting enzyme for RA biosynthesis.33,36 It could also be possible that while bergapten induces cyp26a1, the RA-metabolizing enzyme, the level of cyp26a1 may not be sufficient to metabolize a high concentration of exogenous RA. Additional experiments are needed to determine whether the activity of the psoralens in blood development is due to inhibition of RA biosynthesis, activation of RA metabolism, or a parallel pathway.

In addition to the RA pathway, we also examined if bergapten rescues gata1 via the hox pathway. It has been previously reported that cdx4 homozygous mutant embryos lose posterior hox gene expression, and that hoxb7a and hoxa9a overexpression in these embryos rescue gata1 expression.18 However, when examined by in situ hybridization, the levels of hoxb7a and hoxa9a RNA expression in the control and bergapten-treated embryos were identical (Supplemental Fig. S3, available online at www.liebertonline.com). This indicates that bergapten rescues gata1 expression via a mechanism that is independent of the hox pathways.

Multiple steps need to be carefully considered before performing a modifier screen on a mutant background. First is the variability in the rescue phenotype. During this screen, significant plate-to-plate variability of gata1 expression in the untreated mutant embryos was noted. This was likely due to slight differences in staging and nonsynchronized embryos. Another influencing factor was the in situ hybridization step, which depended on the quality of the riboprobe used and the length of staining time. Of note, even with the most robust rescues, increased gata1 expression was never observed in 100% of the cdx4-mutant embryos in a given well. Using 50% as the threshold proved to be adequate to identify legitimate hits.

A second point to be considered is the toxicity of chemicals to the embryos. The overall toxicity detected in our screen was 5.2%. This was more than double the 2% toxicity level experienced by North et al. (T.E. North, pers. comm.), who screened the same chemical library we did. Of note, in our screen, embryos were incubated at an earlier stage than in the screen by North et al., whose embryos were incubated from the three-somite stage to 36 h postfertilization.5 Not surprisingly, incubation during gastrulation resulted in a higher rate of toxicity. This should be taken into account when designing a chemical screen, along with the stages when the mutant gene is anticipated to have the most influence. For example, as cdx4 has important A-P patterning effects during gastrulation that set up the expression levels of the posterior hox genes, our screen was designed to include chemical exposure during gastrulation. The effect of bergapten on gata1 is diminished when added to embryos after completing gastrulation (data not shown), and so if our screen had been designed for later chemical exposure time, we may not have detected bergapten as a hit.

Chemical modifier screens using a mutant background can provide useful knowledge about the affected pathways in that mutant, particularly related to a specific phenotype of interest. We have shown in our study that the loss of gata1 and pu.1 expression in the cdx4-mutant embryos is rescued by changing A-P axis development. The zebrafish community has many mutants with hematopoietic defects that are affected at various steps during hematopoietic development, including mutants with defective hematopoietic stem cells and mutants with problems at later stages of blood differentiation. Conducting a chemical modifier screen in these various mutants will increase our understanding of normal hematopoietic development and may provide insight into aberrant development and hematopoietic malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the ICCB at Harvard Medical School for providing the chemical libraries used in the screen. The authors also thank R. White for insightful suggestions, and other members of the Zon Laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (5K08DK074595 to J.L.O.d.; 2R01HL048801-15A2 to L.I.Z.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (to L.I.Z.).

Disclosure Statement

L.I.Z. is a founder and stockholder of Fate, Inc. and a scientific advisor for Stemgent.

References

- 1.Peterson RT. Shaw SY. Peterson TA. Milan DJ. Zhong TP. Schreiber SL, et al. Chemical suppression of a genetic mutation in a zebrafish model of aortic coarctation. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stern HM. Murphey RD. Shepard JL. Amatruda JF. Straub CT. Pfaff KL, et al. Small molecules that delay S phase suppress a zebrafish bmyb mutant. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nchembio749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayliss PE. Bellavance KL. Whitehead GG. Abrams JM. Aegerter S. Robbins HS, et al. Chemical modulation of receptor signaling inhibits regenerative angiogenesis in adult zebrafish. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nchembio778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murphey RD. Stern HM. Straub CT. Zon LI. A chemical genetic screen for cell cycle inhibitors in zebrafish embryos. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;68:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.North TE. Goessling W. Walkley CR. Lengerke C. Kopani KR. Lord AM, et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates vertebrate haematopoietic stem cell homeostasis. Nature. 2007;447:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/nature05883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao J. Daleo MA. Murphy CK. Yu PB. Ho JN. Hu J, et al. Dorsomorphin, a selective small molecule inhibitor of BMP signaling, promotes cardiomyogenesis in embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachidanandan C. Yeh JR. Peterson QP. Peterson RT. Identification of a novel retinoid by small molecule screening with zebrafish embryos. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu PB. Hong CC. Sachidanandan C. Babitt JL. Deng DY. Hoyng SA, et al. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao Y. Semanchik N. Lee SH. Somlo S. Barbano PE. Coifman R, et al. Chemical modifier screen identifies HDAC inhibitors as suppressors of PKD models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21819–21824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911987106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.North TE. Goessling W. Peeters M. Li P. Ceol C. Lord AM, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell development is dependent on blood flow. Cell. 2009;137:736–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh JR. Munson KM. Elagib KE. Goldfarb AN. Sweetser DA. Peterson RT. Discovering chemical modifiers of oncogene-regulated hematopoietic differentiation. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:236–243. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieschke GJ. Currie PD. Animal models of human disease: zebrafish swim into view. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:353–367. doi: 10.1038/nrg2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ransom DG. Haffter P. Odenthal J. Brownlie A. Vogelsang E. Kelsh RN, et al. Characterization of zebrafish mutants with defects in embryonic hematopoiesis. Development. 1996;123:311–319. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein BM. Schier AF. Abdelilah S. Malicki J. Solnica-Krezel L. Stemple DL, et al. Hematopoietic mutations in the zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:303–309. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett CM. Kanki JP. Rhodes J. Liu TX. Paw BH. Kieran MW, et al. Myelopoiesis in the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Blood. 2001;98:643–651. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lieschke GJ. Oates AC. Paw BH. Thompson MA. Hall NE. Ward AC, et al. Zebrafish SPI-1 (PU.1) marks a site of myeloid development independent of primitive erythropoiesis: implications for axial patterning. Dev Biol. 2002;246:274–295. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Detrich HW., 3rd Kieran MW. Chan FY. Barone LM. Yee K. Rundstadler JA, et al. Intraembryonic hematopoietic cell migration during vertebrate development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10713–10717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson AJ. Ernst P. Wang Y. Dekens MP. Kingsley PD. Palis J, et al. cdx4 mutants fail to specify blood progenitors and can be rescued by multiple hox genes. Nature. 2003;425:300–306. doi: 10.1038/nature01973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russo JE. Hauguitz D. Hilton J. Inhibition of mouse cytosolic aldehyde dehydrogenase by 4-(diethylamino)benzaldehyde. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:1639–1642. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) 4th. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimmel CB. Ballard WW. Kimmel SR. Ullmann B. Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thisse C. Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson MA. Ransom DG. Pratt SJ. MacLennan H. Kieran MW. Detrich HW, 3rd, et al. The cloche and spadetail genes differentially affect hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis. Dev Biol. 1998;197:248–269. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxtoby E. Jowett T. Cloning of the zebrafish krox-20 gene (krx-20) and its expression during hindbrain development. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.5.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weinberg ES. Allende ML. Kelly CS. Abdelhamid A. Murakami T. Andermann P, et al. Developmental regulation of zebrafish MyoD in wild-type, no tail and spadetail embryos. Development. 1996;122:271–280. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao EC. Paw BH. Oates AC. Pratt SJ. Postlethwait JH. Zon LI. SCL/Tal-1 transcription factor acts downstream of cloche to specify hematopoietic and vascular progenitors in zebrafish. Genes Dev. 1998;12:621–626. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J. Talbot WS. Schier AF. Positional cloning identifies zebrafish one-eyed pinhead as a permissive EGF-related ligand required during gastrulation. Cell. 1998;92:241–251. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80918-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Honigsmann H. Jaschke E. Gschnait F. Brenner W. Fritsch P. Wolff K. 5-Methoxypsoralen (Bergapten) in photochemotherapy of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 1979;101:369–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1979.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern RS. Psoralen and ultraviolet a light therapy for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:682–690. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct072317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emoto Y. Wada H. Okamoto H. Kudo A. Imai Y. Retinoic acid-metabolizing enzyme Cyp26a1 is essential for determining territories of hindbrain and spinal cord in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2005;278:415–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perz-Edwards A. Hardison NL. Linney E. Retinoic acid-mediated gene expression in transgenic reporter zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2001;229:89–101. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitz A. Sankaranarayanan A. Azam P. Schmidt-Lassen K. Homerick D. Hansel W, et al. Design of PAP-1, a selective small molecule Kv1.3 blocker, for the suppression of effector memory T cells in autoimmune diseases. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68:1254–1270. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Begemann G. Schilling TF. Rauch GJ. Geisler R. Ingham PW. The zebrafish neckless mutation reveals a requirement for raldh2 in mesodermal signals that pattern the hindbrain. Development. 2001;128:3081–3094. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozdemir M. Engin B. Toy H. Mevlitoglu I. Treatment of plaque-type localized scleroderma with retinoic acid and ultraviolet A plus the photosensitizer psoralen: a case series. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:519–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith G. Wolf CR. Deeni YY. Dawe RS. Evans AT. Comrie MM, et al. Cutaneous expression of cytochrome P450 CYP2S1: individuality in regulation by therapeutic agents for psoriasis and other skin diseases. Lancet. 2003;361:1336–1343. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niederreither K. McCaffery P. Drager UC. Chambon P. Dolle P. Restricted expression and retinoic acid-induced downregulation of the retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 2 (RALDH-2) gene during mouse development. Mech Dev. 1997;62:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.