Abstract

TDP-43 is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed member of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) family of proteins. Recently, TDP-43 was shown to be a major disease protein in the ubiquitinated inclusions characteristic of most cases of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), tau-negative frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), and inclusion body myopathy. In these diseases, TDP-43 is redistributed from its predominantly nuclear location to ubiquitin-positive, cytoplasmic foci. The extent to which TDP-43 drives pathophysiology is unknown, but the identification of mutations in TDP-43 in familial forms of ALS and FTLD-U suggests an important role for this protein in pathogenesis. Little is known about TDP-43 function and only a few TDP-43 interacting proteins have been previously identified, which makes further insight into both the normal and pathological functions of TDP-43 difficult. Here we show, via a global proteomic approach, that TDP-43 has extensive interaction with proteins that regulate RNA metabolism. Some interactions with TDP-43 were found to be dependent on RNA-binding, whereas other interactions are RNA-independent. Disease-causing mutations in TDP-43 (A315T and M337V) do not alter its interaction profile. TDP-43 interacting proteins largely cluster into two distinct interaction networks, a nuclear/splicing cluster and a cytoplasmic/translation cluster, strongly suggesting that TDP-43 has multiple roles in RNA metabolism and functions in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Finally, we found numerous TDP-43 interactors that are known components of stress granules and, indeed, we find that TDP-43 is also recruited to stress granules.

Introduction

The RNA binding protein TDP-431 was recently identified as the major disease protein in the ubiquitinated inclusions characteristic of sporadic and familial forms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), tau-negative frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), and inclusion body myopathy. TDP-43 pathology also frequently accompanies the pathognomonic pathology of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases2-4. In these diseases, TDP-43 is redistributed from its predominantly nuclear location to ubiquitin-positive, cytoplasmic foci. The extent to which TDP-43 drives pathophysiology is unknown, but the identification of mutations in TDP-43 underlying rare familial forms of ALS and FTLD suggests an important role for this protein in pathogenesis5-9.

TDP-43 is a highly conserved and ubiquitously expressed member of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) family of proteins10. TDP-43 contains two RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) and binds RNA primarily through the first of these1. The glycine-rich C-terminus of TDP-43 has been shown to mediate interaction with several other hnRNP proteins, specifically hnRNPs A1, A2/B1, C1/C2, and A311, although the full extent of TDP-43 interactions has not been previously described. Predominantly a nuclear protein, TDP-43 has been shown to shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm12. Interestingly, TDP-43 redistributes to cytosolic granules as a physiological response to neuronal injury, and nuclear localization is restored after recovery13, 14.

Little is known about TDP-43 function, although there is evidence from experimental systems that TDP-43 can negatively regulate expression of target genes at multiple levels, including transcription, splicing and translation15-17, although the full extent of TDP-43 target genes and the influence of TDP-43 on their expression is not known. Additionally, there is no clear consensus of how pathological TDP-43 functions within diseased cells.

To date, only a few TDP-43 interacting proteins have been identified, which makes further insight into both the normal and pathological functions of TDP-43 difficult. Here we show, via a global proteomic approach, that TDP-43 has extensive interaction with proteins that regulate mRNA metabolism. TDP-43 interacting proteins largely cluster into two distinct protein interaction networks. The first is a network of nuclear proteins that regulate RNA splicing and other aspects of nuclear RNA metabolism, and the second is a network of cytoplasmic proteins that regulate mRNA translation. Additionally, we show that TDP-43 interaction with some proteins is dependent on TDP-43 interaction with RNA, whereas other interactions are RNA-independent. Surprisingly, the disease-causing mutations A315T and M337V do not alter the profile of TDP-43 interactions. Numerous proteins in translational regulation cluster are known to accumulate in stress granules and, indeed, we find that TDP-43 is also recruited to stress granules.

Methods

Plasmids

FLAG-TDP-43 was subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA 3.1(+) (Invitrogen). FLAG-TDP-43(A315T), FLAG-TDP-43(M337V) and FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) with the W113A and R151A mutations were generated using PCR to perform site-directed mutagenesis.

Immunoprecipitations/Immunoblot

10 cm2 plates of HEK-293T or HeLa cells grown in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 culture media were transfected with 5μg of FLAG-TDP-43 or relevant TDP-43 mutant plasmid for 48 hours. Cells were then lysed in gentle lysis buffer (1X PBS, 5mM EDTA, 0.2% NP-40, 10% glycerol + Roche complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail Cat# 11836170001), passed five times through a 21-gauge needle, and spun at 20,000g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was pre-cleared using Protein G affinity gel (Sigma, Cat# E3403) for 30 minutes and then immunoprecipitated using Anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma, Cat# F2426) for 1.5 hours at 4C. The immunoprecipitate was then eluted using FLAG peptide (Sigma, Cat# F3290) at 4C for 30 minutes. 330 μg of RNase A (Sigma, Cat# R4642) was added immediately following lysis prior to immunoprecipitation where indicated. For immunoprecipitation from mouse brain tissue, mouse brain homogenate was lysed as described above and then immunoprecipitated with 2.5 μg of TDP-43 polyclonal antibody (Proteintech, Cat# 10782-2-AP). As a control, half of the homogenate was immunoprecipitated using normal rabbit IgG.

Lysates/immunoprecipitates were separated on a 8-16% gradient tris-glycine gel. M2 monoclonal antibody (Sigma, Cat# F1804) and TDP-43 polyclonal antibody (Proteintech, Cat# 10782-2-AP) were used to visualize TDP-43. Polyclonal antibodies were also used to visualize PABPC1, hnRNP H and hnRNP U respectively (Abcam Cat# ab21060 and ab10374, Bethyl Laboratories Cat# A300-689A).

Immunofluorescence

HEK-293T cells grown on chamber slides (Lab-Tek Cat#154917) were transiently transfected with FLAG-TDP43 or FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics). After 48 h, HEK-293T cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature. The cells were then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X in PBS and incubated with primary antibodies for 1 hr to visualize TDP-43, hnRNP H, PABPC1, EIF4G and G3BP1. Cells were then washed and proteins were visualized using secondary antibodies conjugated to Rhodamine Red-X and FITC (Jackson Immunoresearch). Cells were then washed, stained with DAPI and visualized on a Leica DMIRE2 fluorescent microscope using a 63X objective.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used to visualize proteins: mouse anti-FLAG M2 (1:1000 for western blot and immunofluorescence) (Sigma Cat# F1804), rabbit anti-TDP-43 (1:350 for immunofluorescence) (Proteintech Group Cat# 10782-2-AP), rabbit anti-PABPC1 (1:1000 for western blot, 1:200 for immunofluorescence) (Abcam Cat# ab21060-100), rabbit anti-hnRNP H (1:10,000 western blot, 1:500 for immunofluorescence) (Abcam, Cat# 10374-50), mouse anti-G3BP1 (1:200 for immunofluorescence) (BD Transduction Laboratories Cat #611126), and rabbit anti-EIF4G (1:200 for immunofluorescence) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Cat# sc-11373)

LC-MS/MS protein identification

FLAG epitope-tagged TDP-43 constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells and immunoprecipitated as described above. The sample was then run on an 8-16% gel, and analyzed as described below.

Enzymatic Digest of Proteins

The gel lane containing the immunoprecipitated sample was manually excised into 24 bands in the molecular weight range between 14 kDa and greater than 200 kDa. Each of the protein bands was then digested individually as below. The protein bands were cut into small plugs, washed with 50% acetonitrile, and destained by several incubations in 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8 containing 50% acetonitrile. Reduction (10 mM, DTT for 1 hour at 37°C) and alkylation (50 mM iodoacetamide for 45 min at room temperature in the dark) were performed, followed by washing of the gel plugs with 50% acetonitrile in 50mM ammonium bicarbonate twice. The gel plugs were then dried using a speedvac (Savant) and rehydrated in 10 μl of 0.2ug trypsin. 25uL of 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8 was added to the tube after 10 minutes. The peptides were extracted from the gel plugs using 20 to 30uL of 0.2% formic acid after an overnight (approx 12 hours) enzymatic reaction at 37°C. The solution was then transferred to a sample vial for LC-MS/MS analysis. Non-transfected cells were used as a control and treated in an identical manner to determine non-specific interactions.

Electrospray Ionization Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry Analysis

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed using a ThermoFisher LTQ XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer in line with a nanoAcquity ultra performance LC system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). Tryptic peptides generated above were loaded onto a “precolumn” (Symmetry C18, 180μm i.d X 20mm, 5μm particle) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA) which was connected through a zero dead volume union to the analytical column (BEH C18, 75μm i.d X 100mm, 1.7μm particle) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). The peptides were then eluted over a gradient (0-70% B in 60 minutes, 70-100% B in 10 minutes, where B = 70% Acetonitrile, 0.2% formic acid) at a flow rate of 250nL/min and introduced online into the linear ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Corporation, San Jose, CA) using electrospray ionization (ESI). Data dependent scanning was incorporated to select the 10 most abundant ions (one microscan per spectra; precursor isolation width 3.0Da, 35% collision energy, 30ms ion activation, exclusion duration: 30s; repeat duration: 15s; repeat count: 2) from a full-scan mass spectrum for fragmentation by collision activated dissociation (CAD).

Database Searching

Product ions generated above (b/y-type ions) were used in an automated database search against the Swissprot (Swissprot 57.1, Homo Sapiens subset) database by the Mascot search algorithm18 using trypsin (1 missed cleavages) as the digestion enzyme. The following residue modifications were allowed in the search: carbamidomethylation on cysteine and oxidation on methionine. Mascot was searched with a precursor ion tolerance of 1.0 Da and a fragment ion tolerance of 0.6 Da. Using the automatic decoy database searching tool in the Mascot, a false discovery rate for peptide matches above the identity threshold was estimated to be 4%. In addition, searches were also performed on two mgf files (one for IP lane and one for the control lane) that were generated by merging data from all the bands in each lane. The identifications from the automated search were further validated through Scaffold (Proteome Software, Portland, OR) and manual inspection of the raw data. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95% probability as specified by the Peptide Prophet algorithm19. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 99% probability and contained at least 2 identified peptides. Protein probabilities were assigned by the Protein Prophet algorithm20.

Results

Identification of the TDP-43 interacting proteins in HEK-293 cells

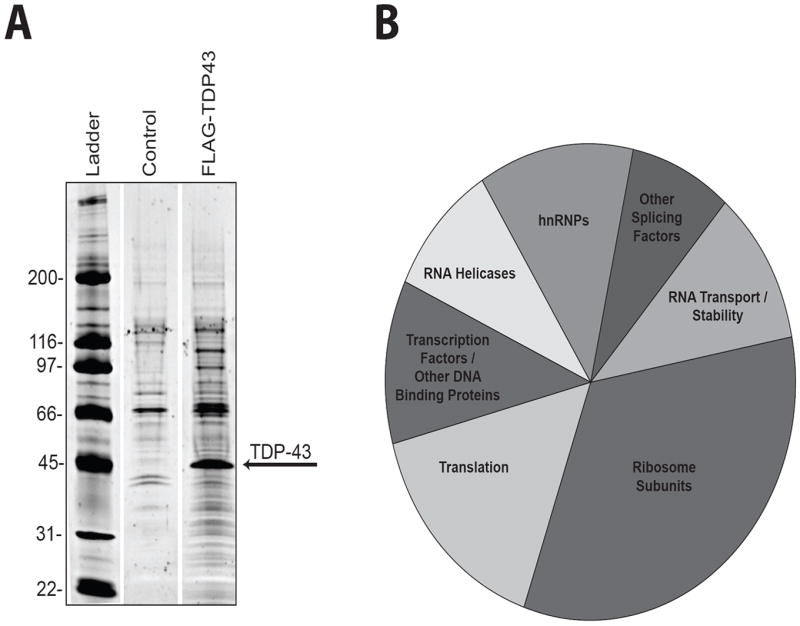

TDP-43 interacting proteins in human epithelial kidney (HEK-293T) cells were isolated by immunoprecipitation of FLAG-TDP-43 followed by identification of co-purified proteins by mass spectrometry (Figure 1A, Sup. Figure 1). We found 261 proteins to be enriched in the FLAG-TDP-43 immunoprecipitate relative to control (Table 1). Of these 261 proteins, 126 were found exclusively in association with TDP-43. Sixty-eight proteins were found to be enriched in the control relative to the immunoprecipitate indicating that our immunoprecipitation was highly specific ( Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1. Identification of TDP-43 interacting proteins by FLAG-immunoprecipitation.

(A) Immunoprecipitates from FLAG-TDP-43-expressing HEK-293T cells or control HEK-293T cells were separated by gel electrophoresis and stained with Sypro-Ruby to visualize proteins. Both the control and FLAG-TDP-43 lanes were separated into 24 bands along the entire length of the gel and analyzed by mass spectrometry. Intervening empty lanes were removed for visualization purposes. (B) Pie-chart representation of functional classes of TDP-43-interacting proteins.

Table 1. TDP-43 Interacting Proteins.

Proteins identified by mass spectrometry that were enriched in TDP-43 immunoprecipitation compared to control. Protein symbol in parenthesis is gene name assigned by STRING as used in Figure 2 if it differs from the official gene name. An asterisk in the final column indicates that no peptides were identified as being present in the control lane.

| Protein Name | Symbol | Molecular Weight (kDa) | Accession Number | Total Spectra: FLAG IP | Unique Peptides: FLAG IP | Percent Coverage: FLAG IP | Total Spectra: Control | Unique Peptides: Control | Percent Coverage: Control | Fold Spectra Increase: IP / Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAR DNA-binding protein 43 | TARDBP | 45 | Q13148 | 176 | 17 | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S3 | RPS3 | 27 | P23396 | 68 | 16 | 55 | 22 | 10 | 47 | 3.1 |

| Nucleolin | NCL | 77 | P19338 | 57 | 20 | 25 | 19 | 8 | 11 | 3.0 |

| Polyadenylate-binding protein 1 | PABPC1 | 71 | P11940 | 53 | 27 | 36 | 27 | 16 | 25 | 2.0 |

| Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | HSPA8 | 71 | P11142 | 51 | 23 | 33 | 13 | 7 | 14 | 3.9 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase A | DHX9 | 141 | Q08211 | 49 | 27 | 23 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 3.5 |

| Histone H1.3 | HIST1H1D | 22 | P16402 | 46 | 7 | 19 | 5 | 3 | 15 | 9.2 |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1 | HSPA1A | 70 | P08107 | 44 | 23 | 28 | 14 | 10 | 17 | 3.1 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U | HNRNPU (HNRPU) | 91 | Q00839 | 43 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 2.9 |

| Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 | ILF3 | 95 | Q12906 | 42 | 14 | 17 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 4.2 |

| Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase DHX30 | DHX30 | 134 | Q7L2E3 | 41 | 24 | 18 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20.5 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S9 | RPS9 | 23 | P46781 | 40 | 15 | 46 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 4.4 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L7a | RPL7A | 30 | P62424 | 38 | 12 | 35 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 3.5 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 | HNRNPA2B1 (HNRPA2B1) | 37 | P22626 | 38 | 9 | 24 | 13 | 5 | 17 | 2.9 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C1/C2 | HNRNPC (HNRPC) | 34 | P07910 | 34 | 12 | 28 | 6 | 5 | 19 | 5.7 |

| Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 | IGF2BP1 | 63 | Q9NZI8 | 33 | 17 | 31 | 20 | 13 | 27 | 1.7 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX5 | DDX5 | 69 | P17844 | 32 | 15 | 27 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 4.0 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S18 | RPS18 | 18 | P62269 | 31 | 11 | 49 | 5 | 3 | 19 | 6.2 |

| 40S ribosomal protein SA | RPSA | 33 | P08865 | 30 | 12 | 42 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 4.3 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L6 | RPL6 | 33 | Q02878 | 30 | 9 | 29 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 10.0 |

| Nucleolar RNA helicase 2 | DDX21 | 87 | Q9NR30 | 29 | 16 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| RNA-binding protein Musashi homolog 2 | MSI2 | 35 | Q96DH6 | 29 | 5 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Trypsin-3 | PRSS3 | 33 | P35030 | 29 | 3 | 10 | 18 | 2 | 7 | 1.6 |

| La-related protein 1 | LARP1 | 124 | Q6PKG0 | 27 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6.8 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | HNRNPA1 (HNRPA1) | 39 | P09651 | 27 | 8 | 25 | 8 | 5 | 18 | 3.4 |

| Putative helicase MOV-10 | MOV10 | 114 | Q9HCE1 | 26 | 18 | 21 | 7 | 6 | 8 | 3.7 |

| Regulator of nonsense transcripts 1 | UPF1 | 124 | Q92900 | 25 | 18 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Tubulin beta chain | TUBB | 50 | P07437 | 25 | 8 | 20 | 12 | 7 | 19 | 2.1 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S3a | RPS3A | 30 | P61247 | 24 | 11 | 36 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 6.0 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX17 | DDX17 | 72 | Q92841 | 23 | 11 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 23.0 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S16 | RPS16 | 16 | P62249 | 23 | 7 | 42 | 4 | 3 | 19 | 5.8 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Q | SYNCRIP | 70 | O60506 | 23 | 9 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 2.9 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K | HNRNPK | 51 | P61978 | 23 | 10 | 25 | 19 | 11 | 28 | 1.2 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S2 | RPS2 | 31 | P15880 | 22 | 9 | 27 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 11.0 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | HNRNPM (HNRPM) | 78 | P52272 | 22 | 13 | 24 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7.3 |

| ATP-dependent DNA helicase 2 subunit 1 | XRCC6 | 70 | P12956 | 21 | 12 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S6 | RPS6 | 29 | P62753 | 21 | 7 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 10.5 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-like protein 1 | HNRNPUL1 (HNRPUL1) | 96 | Q9BUJ2 | 21 | 9 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 21.0 |

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | RPLP0 | 34 | P05388 | 21 | 12 | 47 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 5.3 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L26 | RPL26 | 17 | P61254 | 20 | 6 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 10.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L8 | RPL8 | 28 | P62917 | 20 | 6 | 19 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 6.7 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform | RPS4X | 30 | P62701 | 20 | 12 | 46 | 7 | 4 | 17 | 2.9 |

| Zinc finger CCCH-type antiviral protein 1 | ZC3HAV1 | 101 | Q7Z2W4 | 19 | 12 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Ubiquitin | RPS27A (UBB) | 9 | P61864 | 19 | 3 | 45 | 8 | 2 | 33 | 2.4 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D0 | HNRNPD | 38 | Q14103 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 1.9 |

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 2 | PCBP2 | 39 | Q15366 | 19 | 7 | 25 | 9 | 5 | 19 | 2.1 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX1 | DDX1 | 82 | Q92499 | 19 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 1.3 |

| BAT2 domain-containing protein 1 | BAT2D1 | 317 | Q9Y520 | 18 | 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L7 | RPL7 | 29 | P18124 | 18 | 7 | 16 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4.5 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DHX36 | DHX36 | 115 | Q9H2U1 | 18 | 11 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 18.0 |

| DNA-binding protein A | CSDA | 40 | P16989 | 18 | 8 | 24 | 5 | 2 | 10 | 3.6 |

| Polyadenylate-binding protein 4 | PABPC4 | 71 | Q13310 | 18 | 14 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 9.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L13 | RPL13 | 24 | P26373 | 18 | 6 | 27 | 8 | 5 | 21 | 2.3 |

| Splicing factor, proline- and glutamine-rich | SFPQ | 76 | P23246 | 18 | 11 | 16 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 1.8 |

| Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 3 | IGF2BP3 | 64 | O00425 | 18 | 12 | 23 | 14 | 10 | 16 | 1.3 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma 1 | EIF4G1 | 176 | Q04637 | 17 | 10 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nucleophosmin | NPM1 | 33 | P06748 | 17 | 6 | 26 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8.5 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L4 | RPL4 | 48 | P36578 | 17 | 7 | 19 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 8.5 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | HNRNPH1 (HNRPH1) | 49 | P31943 | 17 | 7 | 22 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 4.3 |

| DNA topoisomerase 1 | TOP1 | 91 | P11387 | 16 | 10 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| La-related protein 4 | LARP4 | 81 | Q71RC2 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S25 | RPS25 | 14 | P62851 | 16 | 4 | 24 | 7 | 3 | 24 | 2.3 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L18 | RPL18 | 22 | Q07020 | 16 | 6 | 31 | 15 | 4 | 25 | 1.1 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S11 | RPS11 | 18 | P62280 | 15 | 9 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S14 | RPS14 | 16 | P62263 | 15 | 6 | 25 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 7.5 |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase 38 | STK38 | 54 | Q15208 | 15 | 6 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 1.3 |

| 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | HSPD1 | 61 | P10809 | 15 | 10 | 17 | 10 | 8 | 15 | 1.5 |

| Matrin-3 | MATR3 | 95 | P43243 | 14 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase YTHDC2 | YTHDC2 | 160 | Q9H6S0 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein | NONO | 54 | Q15233 | 14 | 9 | 25 | 12 | 7 | 22 | 1.2 |

| ELAV-like protein 1 | ELAVL1 | 36 | Q15717 | 13 | 5 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3.3 |

| Far upstream element-binding protein 2 | KHSRP | 73 | Q92945 | 13 | 9 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 6.5 |

| Tubulin alpha-1B chain | TUBA1B | 50 | P68363 | 13 | 9 | 26 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 3.3 |

| Microtubule-associated protein 1B | MAP1B | 271 | P46821 | 13 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Dermcidin | DCD | 11 | P81605 | 12 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B | HNRNPAB | 36 | Q99729 | 12 | 5 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 2 | IGF2BP2 | 66 | Q9Y6M1 | 12 | 8 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 12.0 |

| Constitutive coactivator of PPAR-gamma-like protein 1 | FAM120A | 122 | Q9NZB2 | 12 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4.0 |

| Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1 | G3BP1 | 52 | Q13283 | 12 | 5 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6.0 |

| Caprin-1 | CAPRIN1 | 78 | Q14444 | 12 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 2.4 |

| Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 2 | ILF2 | 43 | Q12905 | 12 | 7 | 21 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 3.0 |

| Heat shock protein 105 kDa | HSPH1 | 97 | Q92598 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-like protein 2 | HNRNPUL2 | 85 | Q1KMD3 | 11 | 8 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Lupus La protein | SSB | 47 | P05455 | 11 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Probable dimethyladenosine transferase | DIMT1L | 35 | Q9UNQ2 | 11 | 7 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A3 | HNRNPA3 (HNRPA3) | 40 | P51991 | 11 | 8 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 11.0 |

| Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 | PTBP1 | 57 | P26599 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L3 | RPL3 | 46 | P39023 | 11 | 7 | 21 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 3.7 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S19 | RPS19 | 16 | P39019 | 11 | 4 | 18 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 1.6 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L5 | RPL5 | 34 | P46777 | 10 | 7 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| RNA-binding protein Musashi homolog 1 | MSI1 | 39 | O43347 | 10 | 5 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L10 | RPL10 | 25 | P27635 | 10 | 6 | 21 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 2.5 |

| UPF0027 protein C22orf28 | C22orf28 | 55 | Q9Y3I0 | 10 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 1.7 |

| 14-3-3 protein sigma | SFN | 28 | P31947 | 9 | 6 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Double-stranded RNA-binding protein Staufen homolog 1 | STAU1 | 63 | O95793 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| La-related protein 4B | LARP4B | 81 | A6NEL6 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S20 | RPS20 | 13 | P60866 | 9 | 6 | 29 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 9.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L12 | RPL12 | 18 | P30050 | 9 | 6 | 43 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4.5 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L19 | RPL19 | 23 | P84098 | 9 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3.0 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX3X | DDX3X | 73 | O00571 | 9 | 7 | 12 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4.5 |

| Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7 | SFRS7 | 27 | Q16629 | 9 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4.5 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L24 | RPL24 | 18 | P83731 | 9 | 3 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 13 | 1.8 |

| ADP/ATP translocase 2 | SLC25A5 | 33 | P05141 | 9 | 7 | 20 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 4.5 |

| ATP-dependent DNA helicase 2 subunit 2 | XRCC5 | 83 | P13010 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Histone H1x | H1FX | 22 | Q92522 | 8 | 4 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Probable helicase with zinc finger domain | HELZ | 219 | P42694 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Putative ATP-dependent RNA helicase DHX57 | DHX57 | 156 | Q6P158 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L31 | RPL31 | 14 | P62899 | 8 | 2 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 2.7 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L35 | RPL35 | 15 | P42766 | 8 | 2 | 19 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 2.0 |

| Heat shock 70 kDa protein 4 | HSPA4 | 94 | P34932 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 8.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L14 | RPL14 | 23 | P50914 | 8 | 6 | 24 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 4.0 |

| Elongation factor 2 | EEF2 | 95 | P13639 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2.7 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G | RBMX | 42 | P38159 | 8 | 5 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Nuclease-sensitive element-binding protein 1 | YBX1 | 36 | P67809 | 8 | 2 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 19 | 1.6 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S7 | RPS7 | 22 | P62081 | 7 | 5 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Far upstream element-binding protein 3 | FUBP3 | 62 | Q96I24 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein-like 3 | GNL3 | 62 | Q9BVP2 | 7 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein R | HNRNPR (HNRPR) | 71 | O43390 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Ribosome-binding protein 1 | RRBP1 | 152 | Q9P2E9 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase SRPK1 | SRPK1 | 74 | Q96SB4 | 7 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 6 | SFRS6 | 40 | Q13247 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Transcription intermediary factor 1-beta | TRIM28 | 89 | Q13263 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Desmoplakin | DSP | 332 | P15924 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L23a | RPL23A | 18 | P62750 | 7 | 5 | 28 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 2.3 |

| Junction plakoglobin | JUP | 82 | P14923 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 2.3 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L | HNRNPL | 64 | P14866 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1.8 |

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX50 | DDX50 | 83 | Q9BQ39 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Bystin | BYSL | 50 | P48634 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nuclear fragile X mental retardation-interacting protein 2 | NUFIP2 | 76 | Q7Z417 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Plakophilin-1 | PKP1 | 83 | Q13835 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 RNA-binding protein | SERBP1 | 45 | Q8NC51 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Protein LYRIC | MTDH | 64 | Q86UE4 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Serrate RNA effector molecule homolog | SRRT | 101 | Q9BXP5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 200 kDa helicase | SNRNP200 (ASCC3L1) | 245 | O75643 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Zinc finger RNA-binding protein | ZFR | 117 | Q96KR1 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S5 | RPS5 | 23 | P46782 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 1.5 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L10a | RPL10A | 25 | P62906 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L23 | RPL23 | 15 | P62829 | 6 | 3 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 11 | 3.0 |

| 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein | HSPA5 | 72 | P11021 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6.0 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A0 | HNRNPA0 (HNRPA0) | 31 | Q13151 | 6 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6.0 |

| Serum albumin | ALB | 69 | P02768 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1.2 |

| Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 2 | G3BP2 | 54 | Q9UN86 | 6 | 4 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 3.0 |

| Methylosome subunit pICln | CLNS1A | 26 | P54105 | 6 | 5 | 32 | 5 | 3 | 19 | 1.2 |

| U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein A’ | SNRPA1 | 28 | P09661 | 6 | 4 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 2.0 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S23 | RPS23 | 16 | P62266 | 5 | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L17 | RPL17 | 21 | P18621 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L28 | RPL28 | 16 | P46779 | 5 | 4 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L9 | RPL9 | 22 | P32969 | 5 | 4 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| NF-kappa-B-repressing factor | NKRF | 78 | O15226 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nuclear RNA export factor 1 | NXF1 | 70 | Q9UBU9 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nucleolar protein 56 | NOP56 (NOL5A) | 66 | O00567 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 | PCBP1 | 37 | Q15365 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Putative RNA-binding protein Luc7-like 2 | LUC7L2 | 47 | Q9Y383 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| RNA-binding protein Raly | RALY | 32 | Q9UKM9 | 5 | 4 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| rRNA 2’-O-methyltransferase fibrillarin | FBL | 34 | P22087 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| YTH domain family protein 2 | YTHDF2 | 62 | Q9Y5A9 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit B | EIF3B (PRT1) | 92 | P55884 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5.0 |

| Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-I | EIF4A1 | 46 | P60842 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1.7 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein D-like | HNRPDL | 46 | O14979 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2.5 |

| RING finger protein 219 | RNF219 | 81 | Q5W0B1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1.7 |

| RNA-binding protein FUS | FUS | 53 | P35637 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1.7 |

| 28S ribosomal protein S29, mitochondrial | DAP3 | 46 | P51398 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Ataxin-2-like protein | ATXN2L | 113 | Q8WWM7 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Cell division cycle 5-like protein | CDC5L | 92 | Q99459 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Desmocollin-1 | DSC1 | 100 | Q08554 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| DNA-directed RNA polymerase, mitochondrial | POLRMT | 139 | O00411 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Double-stranded RNA-specific adenosine deaminase | ADAR | 136 | P55265 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| G-rich sequence factor 1 | GRSF1 | 53 | Q12849 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Large proline-rich protein BAT2 | BAT2 | 229 | P48634 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nuclear cap-binding protein subunit 1 | NCBP1 | 92 | Q09161 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nucleolar protein 58 | NOP58 (NOL5) | 60 | Q9Y2X3 | 4 | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Pre-rRNA-processing protein TSR1 homolog | TSR1 | 92 | Q2NL82 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Putative ribosomal RNA methyltransferase NOP2 | NOP2 (NOL1) | 89 | P46087 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| TRM1-like protein | TRM1L | 82 | Q7Z2T5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 10 | USP10 | 87 | Q14694 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L11 | RPL11 | 20 | P62913 | 4 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L22 | RPL22 | 15 | P35268 | 4 | 2 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 10 | 2.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L27a | RPL27A | 17 | P46776 | 4 | 2 | 16 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 1.3 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | EIF3C (EIF3S8) | 105 | Q99613 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4.0 |

| Pre-mRNA-processing factor 19 | PRPF19 | 55 | Q9UMS4 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2.0 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX6 | DDX6 | 54 | P26196 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 4.0 |

| Staphylococcal nuclease domain-containing protein 1 | SND1 | 102 | Q7KZF4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.0 |

| Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 59 | LRRC59 | 35 | Q96AG4 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 1.3 |

| Myosin-9 | MYH9 | 227 | P35579 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Uncharacterized protein C11orf84 | C11orf84 | 41 | Q9Y520 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 1.3 |

| Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-III | EIF4A3 | 47 | P38919 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 1.3 |

| Protein FAM98B | FAM98B | 37 | Q9NZB2 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1.3 |

| 28S ribosomal protein S27, mitochondrial | MRPS27 | 48 | Q92552 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 39S ribosomal protein L12, mitochondrial | MRPL12 | 21 | P52815 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 39S ribosomal protein L22, mitochondrial | MRPL22 | 24 | Q9NWU5 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 39S ribosomal protein L44, mitochondrial | MRPL44 | 38 | Q9H9J2 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S17 | RPS17 | 16 | P08708 | 3 | 3 | 32 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 5’-3’ exoribonuclease 1 | XRN1 | 194 | Q8IZH2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L18a | RPL18A | 21 | Q02543 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Aspartyl/asparaginyl beta-hydroxylase | ASPH | 86 | Q12797 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| BAG family molecular chaperone regulator 2 | BAG2 | 24 | O95816 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Complement component 1 Q subcomponent-binding protein, mitochondrial | C1QBP | 31 | Q07021 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| CUG-BP- and ETR-3-like factor 1 | CUGBP1 | 52 | Q92879 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| ELAV-like protein 2 | ELAVL2 | 40 | Q12926 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit I | EIF3I (EIF3S2) | 37 | Q13347 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma 3 | EIF4G3 | 177 | O43432 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 | GNB2L1 | 35 | P63244 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Importin subunit alpha-2 | KPNA2 | 58 | P52292 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Microtubule-associated protein 4 | MAP4 | 121 | P27816 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Myb-binding protein 1A | MYBBP1A | 149 | Q9BQG0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Partner of Y14 and mago | WIBG | 23 | Q9BRP8 | 3 | 2 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Protein FAM98A | FAM98A | 55 | Q8NCA5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Protein LSM12 homolog | LSM12 | 22 | Q3MHD2 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Protein PAT1 homolog 1 | PATL1 | 87 | Q86TB9 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Replication factor C subunit 4 | RFC4 | 40 | P35249 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| RNA-binding protein 39 | RBM39 | 59 | Q14498 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| RuvB-like 2 | RUVBL2 | 51 | Q9Y230 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Transcriptional activator protein Pur-beta | PURB | 33 | Q96QR8 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase | VCP | 89 | P55072 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| U2-associated protein SR140 | SR140 | 118 | O15042 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| U4/U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Prp3 | PRPF3 | 78 | O43395 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| UPF0568 protein C14orf166 | C14orf166 | 28 | Q9NYF8 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 11A | ZC3H11A | 89 | O75152 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Zinc finger protein 346 | ZNF346 | 33 | Q9UL40 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 116 kDa U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein component | EFTUD2 | 109 | Q15029 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 |

| 28S ribosomal protein S22, mitochondrial | MRPS22 | 41 | P82650 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L15 | RPL15 | 24 | P61313 | 3 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3.0 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L32 | RPL32 | 16 | B2R4Q3 | 3 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3.0 |

| Leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 15 | LRRC15 | 64 | Q8TF66 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.0 |

| PERQ amino acid-rich with GYF domain-containing protein 2 | GIGYF2 | 150 | Q6Y7W6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.0 |

| Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein Sm D2 | SNRPD2 | 14 | P62316 | 3 | 2 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 1.5 |

| Ubiquitin-associated protein 2-like | UBAP2L | 115 | Q14157 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 2 | PSMD2 | 100 | Q13200 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1.5 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S13 | RPS13 | 17 | P62277 | 3 | 2 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 1.5 |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase family member 5 | PGAM5 | 32 | Q96HS1 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 1.5 |

| Vimentin | VIM | 54 | P08670 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1.5 |

| 28S ribosomal protein S34, mitochondrial | MRPS34 | 26 | P82930 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 39S ribosomal protein L48, mitochondrial | MRPL48 | 24 | Q96GC5 | 2 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 40S ribosomal protein S24 | RPS24 | 15 | P62847 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 5’-3’ exoribonuclease 2 | XRN2 | 109 | Q9H0D6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L13a | RPL13A | 24 | P40429 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| 60S ribosomal protein L21 | RPL21 | 19 | Q6IAX2 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| ATP synthase subunit alpha, mitochondrial | ATP5A1 | 60 | P25705 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Calcium-binding mitochondrial carrier protein SCaMC-3 | SLC25A23 | 52 | Q9BV35 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Cell division protein kinase 4 | CDK4 | 34 | P11802 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor subunit 1 | CPSF1 | 161 | Q10570 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| DnaJ homolog subfamily B member 6 | DNAJB6 | 36 | O75190 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 3 | EIF2S3 | 51 | P41091 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A | EIF3A (EIF3S10) | 167 | Q14152 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit H | EIF3H (EIF3S3) | 40 | O15372 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Glutaminyl-peptide cyclotransferase-like protein | QPCTL | 43 | Q9NXS2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nascent polypeptide-associated complex subunit alpha | NACA | 23 | Q13765 | 2 | 2 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK | AHNAK | 629 | Q09666 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nucleolar protein 14 | NOP14 | 98 | P78316 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Nucleolar protein 16 | NOP16 | 21 | Q9Y3C1 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Periodic tryptophan protein 2 homolog | PWP2 | 102 | Q15269 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| RING finger protein 10 | RNF10 | 90 | Q8N5U6 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| S1 RNA-binding domain-containing protein 1 | SRBD1 | 112 | Q8N5C6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Superkiller viralicidic activity 2-like 2 | SKIV2L2 | 118 | P42285 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Transcriptional activator protein Pur-alpha | PURA | 35 | Q00577 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| U4/U6.U5 tri-snRNP-associated protein 1 | SART1 | 90 | O43290 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | PHGDH | 57 | O43175 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Elongation factor 1-gamma | EEF1G | 50 | Q53YD7 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Protein argonaute-2 | EIF2C2 | 97 | Q9UKV8 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.0 |

| Protein KIAA1967 | KIAA1967 | 103 | Q8N163 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Protein SDA1 homolog | SDAD1 | 80 | Q9NVU7 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | TPI1 | 27 | P60174 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2.0 |

Analysis of the TDP-43 interactors reveals extensive interaction with proteins that associate with RNA, consistent with previously described roles for TDP-43 in RNA metabolism. These include hnRNPs, RNA helicases, splicing factors, translation regulatory proteins, as well as proteins involved in mRNA transport and stability (Figure 1B and Table I). TDP-43 was found to interact with a smaller number of DNA binding proteins such as transcription factors, consistent with a previously described role for TDP-43 in transcriptional repression1, but also interacts with DNA repair proteins such as Ku70 suggesting that TDP-43 may have roles in DNA metabolism beyond transcriptional regulation (Figure 1B and Table I). Notably, although TDP-43 is predominantly a nuclear protein, we found interaction with both cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins, as well as many proteins that are known to shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm. This likely reflects a functional role for TDP-43 in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm consistent with the observation that TDP-43 itself undergoes nucleocytoplasmic shuttling12.

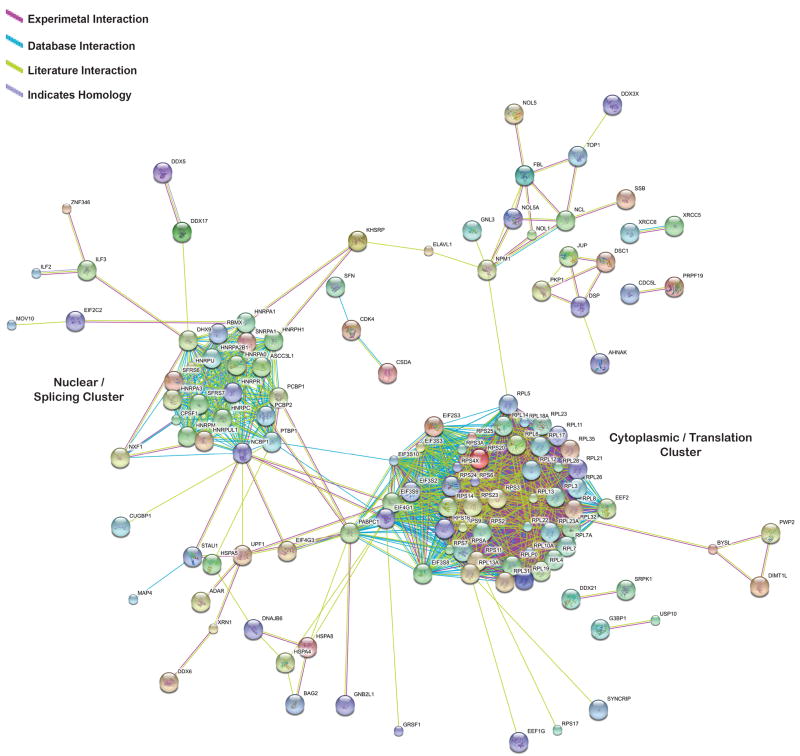

TDP-43 associates with two distinct protein interaction networks

To gain a better understanding of the relationships between TDP-43 interacting proteins, we employed the STRING interaction database21. To minimize the chance of including false positives, our analysis included only those proteins in which the spectral count was at least two-fold enriched in the TDP-43 immunoprecipitate relative to control. Furthermore, only high confidence interactions as determined by the STRING database were accepted. This analysis reveals that TDP-43 interactors cluster largely into two distinct protein interaction networks (Figure 2). The “Nuclear/Splicing Cluster” is comprised entirely of nuclear proteins including many hnRNPs, but also serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins, small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), an ATP-dependent RNA helicase, and nuclear RNA export factors. These proteins are all involved in nuclear RNA metabolism, primarily RNA splicing but also export of mRNA to the cytoplasm (Table 2). The “Cytoplasmic/Translation Cluster” is comprised entirely of cytoplasmic proteins, including translation initiation and elongation factors, and ribosomal subunits (Table 3). Interestingly, PABPC1 was found to link these two distinct protein interaction networks (Figure 2).

Figure 2. TDP-43 interacting proteins form two distinct protein interaction networks.

TDP-43 proteins identified by mass spectrometry were analyzed using STRING interaction software to identify high confidence interactions using database, literature, and experimental search parameters. Only proteins that were at least two-fold enriched in the TDP-43 immunoprecipitate were analyzed using STRING. Two distinct protein interactions were observed that are labeled as the Nuclear/Splicing Cluster and the Cytoplasmic/Translation Cluster.

Table 2. Nuclear hnRNP cluster.

TDP-43 interacting proteins found in the Nuclear/Splicing cluster. The references cited here may be found in the Supplementary References.

| Name | Symbol | Function | Supplementary Reference # |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-dependent RNA helicase A | DHX9 | transcription / translation | 1,2 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U | HNRNPU (HNRPU) | transcrption / mRNA stability | 3,4 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins C1/C2 | HNRNPC (HNRPC) | splicing / mRNA stability | 5,6 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins A2/B1 | HNRNPA2B1 (HNRPA2B1) | splicing | 7 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U-like protein 1 | HNRNPUL1 (HNRPUL1) | mRNA transport | 8 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | HNRNPA1 (HNRPA1) | splicing / mRNA stability | 5,9 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | HNRNPM (HNRPM) | splicing | 5 |

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 2 | PCBP2 | translation | 10 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H | HNRNPH1 (HNRPH1) | splicing | 5 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A3 | HNRNPA3 (HNRPA3) | mRNA transport | 11 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein G | RBMX | splicing | 12 |

| Polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1 | PTBP1 | splicing | 13 |

| Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 7 | SFRS7 | splicing | 14 |

| U5 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein 200 kDa helicase | SNRNP200 (ASCC3L1) | splicing | 15 |

| Poly(rC)-binding protein 1 | PCBP1 | transcription / translation / mRNA stability | 16 |

| Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 6 | SFRS6 | splicing | 17 |

| Nuclear RNA export factor 1 | NXF1 | mRNA transport | 18 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein R | HNRNPR (HNRPR) | splicing / mRNA stability | 19 |

| Nuclear cap-binding protein subunit 1 | NCBP1 | splicing / mRNA transport | 20,21 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A0 | HNRNPA0 (HNRPA0) | Unknown | 22 |

| U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein A’ | SNRPA1 | splicing | 7 |

Table 3. Cytoplasmic translational cluster.

TDP-43 interacting proteins found in the Cytoplasmic/Translation cluster. The references cited here may be found in the Supplementary References.

| Name | Symbol | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40S ribosomal protein S11 | RPS11 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S14 | RPS14 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S16 | RPS16 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S18 | RPS18 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S2 | RPS2 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S20 | RPS20 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S23 | RPS23 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S24 | RPS24 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S25 | RPS25 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S3 | RPS3 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S3a | RPS3A | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S4, X isoform | RPS4X | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S6 | RPS6 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S7 | RPS7 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein S9 | RPS9 | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 40S ribosomal protein SA | RPSA | 40S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S acidic ribosomal protein P0 | RPLP0 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L10a | RPL10A | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L11 | RPL11 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L12 | RPL12 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L13 | RPL13 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L13a | RPL13A | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L14 | RPL14 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L17 | RPL17 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L18A | RPL18A | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L19 | RPL19 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L21 | RPL21 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L22 | RPL22 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L23 | RPL23 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L23a | RPL23A | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L26 | RPL26 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L28 | RPL28 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L3 | RPL3 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L31 | RPL31 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L32 | RPL32 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L35 | RPL35 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L4 | RPL4 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L5 | RPL5 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L6 | RPL6 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L7 | RPL7 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L7a | RPL7A | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| 60S ribosomal protein L8 | RPL8 | 60S ribosome subunit | 24 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma 1 | EIF4G1 | translation initiation factor | 25 |

| Elongation factor 2 | EEF2 (EF2) | translation elongation factor | 26 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit I | EIF3I (EIF3S2) | translation initiation factor | 27 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit A | EIF3A (EIF3S10) | translation initiation factor | 27 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit B | EIF3B (PRT1) | translation initiation factor | 27 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit C | EIF3C (EIF3S8) | translation initiation factor | 27 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit H | EIF3H (EIF3S3) | translation initiation factor | 27 |

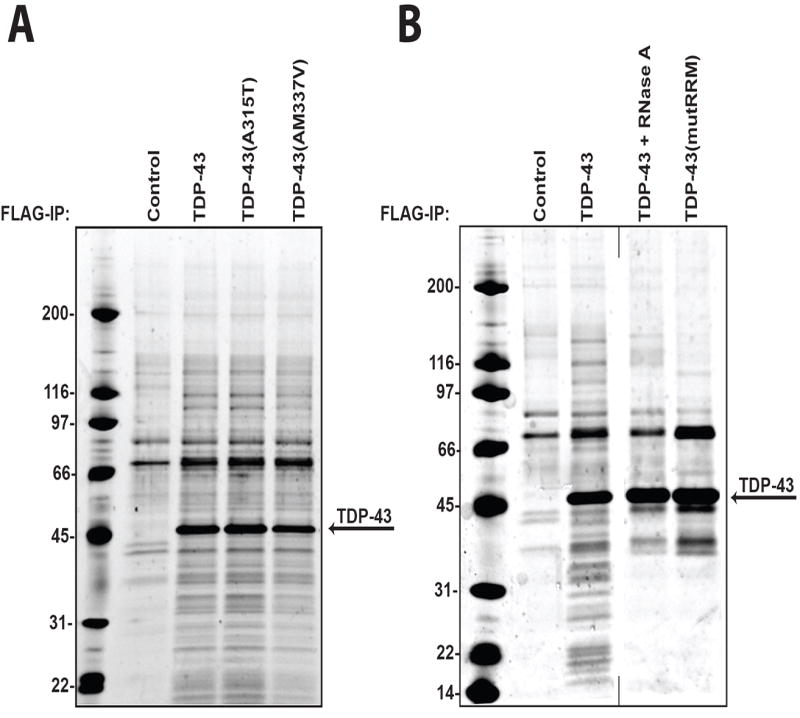

Disease-associated TDP-43 mutations do not significantly impact TDP-43 interactions

The missense mutations A315T and M337V are causative of dominantly inherited ALS5, 7. To investigate whether disease-associated mutations alter the complement of proteins that interact with TDP-43, we introduced each of these mutations into TDP-43 by site-directed mutagenesis and examined their interaction profiles. We found that TDP-43 variants harboring either the A315T or M337V mutation have interaction profiles that are qualitatively indistinguishable from that of wild type TDP-43 by examination of Sypro-Ruby-stained gel (Figure 3A). This finding suggests that the mechanism by which TDP-43 missense mutants are pathogenic may be due to cell type-specific interactions that do not occur in 293T cells or that disease-causing mutations do not grossly alter the function of TDP-43 or its binding partners.

Figure 3. The impact of TDP-43 mutations on interactions.

(A) Disease-associated mutations do not alter the TDP-43 interactome. The figure shows Sypro-Ruby-stained FLAG immunoprecipitates from control HEK-293T cells, HEK-293T cells expressing wild type FLAG-TDP-43, FLAG-TDP-43 (A315T) or FLAG-TDP-43 (M337V) as indicated. FLAG-TDP-43 (M337V) reproducibly immunoprecipitates less efficiently than either FLAG-TDP-43 or FLAG-TDP-43 (A315T) which is proportional to the decrease in intensity of interacting proteins as visualized by Sypro-Ruby. (B) Some TDP-43 interactions are RNA-dependent. The figure shows Sypro-Ruby-stained FLAG immunoprecipitates from control HEK-293T cells, HEK-293T cells expressing wild type FLAG-TDP-43, wild type FLAG-TDP-43 (treated with RNase A), or FLAG-TDP-43 (mutRRM), as indicated. Immunoprecipitation was repeated at least three times with consistent results. Representative images were chosen for display.

Some TDP-43 interactions are RNA-dependent whereas others are RNA-independent

Since TDP-43 and many of its interacting proteins are RNA binding proteins, we sought to determine how RNA binding influences the TDP-43 interactome. RNA binding by TDP-43 is mediated by its first RRM domain22. Two specific point mutations, W113A and R151A, have been previously shown to abolish RNA binding by TDP-4322. We introduced both of these mutations into FLAG-TDP-43 to generate the RNA binding mutant FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM). In comparison with FLAG-TDP-43, some TDP-43 interactions are lost with FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) indicating that many TDP-43 interacting proteins/complexes are strongly influenced by RNA binding (Figure 3B, lane 4). To further examine the role of RNA binding in determining TDP-43 interactions, we performed immunoprecipitation of TDP-43 in the presence of RNase A to degrade RNA. This approach yielded an almost identical interaction profile to FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM), further demonstrating the strong influence of RNA binding on TDP-43 interactions (Figure 3B, lane 3). Many of the RNA-dependent interactions are proteins with molecular weights between ~14 and 35 kDa, a cohort largely comprised of ribosomal subunits, which suggests that the association of TDP-43 with ribosomes is indirect and mediated by interaction with the same transcript. However, other proteins are likely to interact with TDP-43 independent of its ability to bind RNA. Such proteins are more likely to be present in a multimeric protein complex with TDP-43.

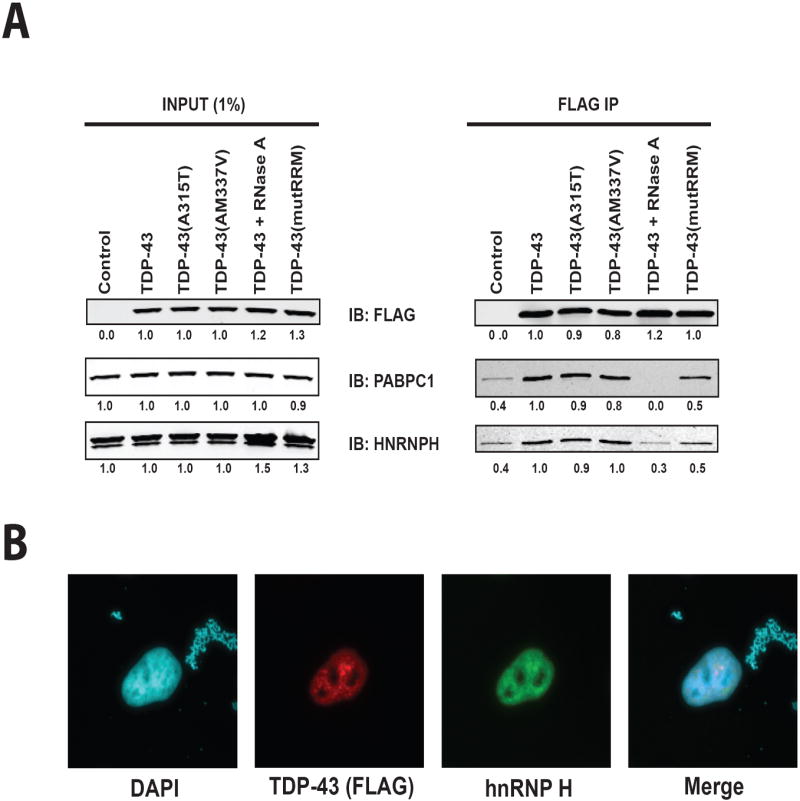

Verification of TDP-43 interacting proteins

We verified a subset of TDP-43 interacting proteins by co-immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot. hnRNP H is one of a large number of hnRNPs found to interact with TDP-43 in our proteomic analysis. Similar to TDP-43, this protein has been shown to be involved in the regulation of splicing23. Immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot confirms an interaction between TDP-43 and hnRNP H (Figure 4A). This interaction is not altered in the disease-associated point mutations A315T or M337V (Figure 4A). The interaction between TDP-43 and hnRNP H is at least partially influenced by TDP-43 binding to RNA because treatment with RNase A strongly mitigates interaction (Figure 4A). Consistent with this finding, hnRNP H shows reduced interaction with the TDP-43(mutRRM) mutant (Figure 4A). To determine the subcellular compartment in which the interaction between TDP-43 and hnRNP H occurs, immunofluorescence was performed in HeLa cells to simultaneously visualize TDP-43 and hnRNP H. TDP-43 and hnRNP H both show pan-nuclear localization and are found to co-localize in nuclear puncta (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Characterization of TDP-43 interaction with hnRNP H and PABPC1.

(A) Validation of TDP-43 interaction with hnRNP H and PABPC1 by co-immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis in HEK-293T cells. Left panel: Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates prior to immunoprecipitation was used to visualize 1% of protein input. Right panel: Western blot analysis of FLAG immunoprecipitates. Quantification was performed using Image J (shown below each band) and normalized to the amount of TDP-43 in lane 2. Immunoprecipitation was repeated at least three times with consistent results and representative images were chosen for display. (B) Immunofluorescence was used to visualize the localization of TDP-43 and hnRNP H in HeLa cells. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nucleus. TDP-43 and hnRNP H both showed pan-nuclear expression with co-localization in sub-nuclear foci in HeLa cells. The immunofluorescence data shown represents consistent results obtained in multiple replicates. IB: immunoblot, IP: immunoprecipitation.

Verification of the interaction between TDP-43 and PABPC1 was also performed. PABPC1 is a predominantly cytoplasmic protein that associates with and stabilizes poly(A) mRNA and is regulates RNA translation24, 25. Immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot confirms that PABPC1 associates with TDP-43 and that this association is not affected by either the A315T or M337V mutation (Figure 4A). Immunoprecipitation in the presence of RNase A reveals that the association between TDP-43 and PABPC1 is also dependent upon RNA since binding is strongly mitigated by treatment with RNAse A (Figure 4A). Consistent with this finding, PABPC1 shows reduced interaction with the TDP-43(mutRRM) mutant (Figure 4A). Thus, hnRNP H and PABPC1 interaction with TDP-43 is completely abolished by RNase A treatment, but only partially mitigated by selectively impairing the ability of TDP-43 to bind RNA (TDP-43-(mutRRM)). RNase A treatment is likely to completely disassemble ribonucleoprotein complexes, thus abolishing both direct and indirect interactions between TDP-43 and RNA binding proteins. On the other hand, the residual binding exhibited by TDP-43(mutRRM) indicates limited ability to associate with multimeric ribonucleoprotein complexes independent of its ability to bind RNA, although the interaction is clearly stabilized by RNA binding. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments were also performed in HeLa cells, confirming the interaction between PABPC1 and hnRNP H with TDP-43 and associated mutants (Sup. Figure 2A) and providing a second cell type in which these novel interactions are observed. Furthermore, we performed co-immunoprecipitation from mouse brain homogenate to confirm that interactions between TDP-43 and PABPC1 and hnRNP U occur with the endogenous TDP-43 protein in one tissue that is frequently affected in TDP-43-related disease (Sup Figure 2B).

TDP-43 localizes to RNA granules in the cytoplasm

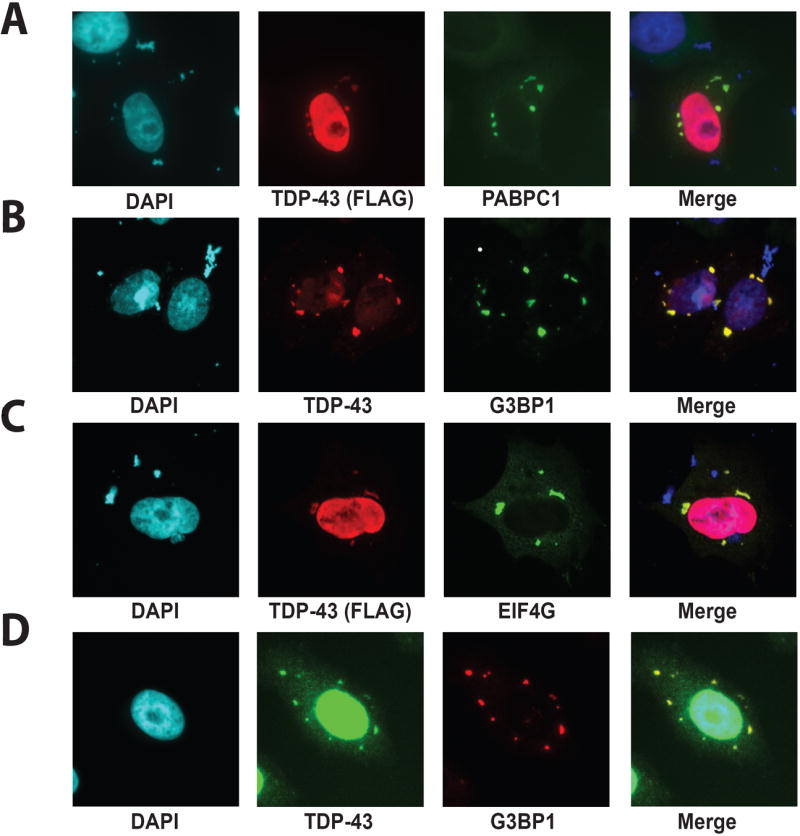

Although TDP-43 is predominantly a nuclear protein, in some HeLa cells TDP-43 can be visualized in discrete cytoplasmic puncta in addition to diffuse nuclear staining (Figure 5A). These puncta do not stain for hnRNP H (data not shown) although they stain strongly for PABPC1, a marker for cytoplasmic RNA granules26 (Figure 5A). Our findings are consistent with previous evidence indicating that TDP-43 co-purifies with cytoplasmic RNA granules27. Cytoplasmic RNA granules, including stress granules, processing bodies and germ cell (or polar) granules are cytoplasmic structures believed to represent physiological accumulations of mRNA and ribonucleoproteins that modulate gene expression by influencing translation, trafficking and stability28. PABPC1 is a specific marker of stress granules26, suggesting that TDP-43 is present in this specific subtype of RNA granule. Further extensive evidence that TDP-43 associates with stress granules was the identification of TDP-43 interaction with numerous additional protein components of stress granules28, 29 (Table 4).

Figure 5. Cytoplasmic TDP-43 is localized in stress granules.

Immunofluorescence was used to visualize the localization of exogenous (A-C) FLAG-TDP-43 or endogenous (D) TDP-43 and (A) PABPC1, (B, D) G3BP1 and (C) EIF4G in HeLa cells. DAPI staining was used to visualize the nucleus. TDP-43 was found to localize with stress granules in the cytoplasm of HeLa cells. (D) After treatment with 50 μM MG-132 for 3 hours, RNA granules were observed in 66% of cells. At least 1 TDP-43 positive stress granule was observed in 25% of cells after MG-132 treatment. 300 HeLa cells were counted. All of the immunofluorescence data shown represents consistent results obtained in multiple replicates.

Table 4. TDP-43 associated stress granule proteins.

Stress granule proteins found to co-immunoprecipitate with TDP-43.

| Name | Symbol |

|---|---|

| Protein argonaute-2 | EIF2C2 |

| Caprin-1 | CAPRIN1 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (5 subunits) | EIF3 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 gamma (2 subunits) | EIF4G |

| Far upstream element-binding protein 2 | KHSRP |

| Ras GTPase-activating protein-binding protein 1 | G3BP1 |

| ELAV-like protein 1 | ELAVL1 |

| Polyadenylate-binding protein 1 | PABPC1 |

| Probable ATP-dependent RNA helicase DDX6 | DDX6 |

| Plakophilin-1 | PKP1 |

| Double-stranded RNA-binding protein Staufen homolog 1 | STAU1 |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 10 | USP10 |

| Eukaryotic initiation factor 4A (2 subunits) | EIF4A |

| Nuclease sensitive element-binding protein 1 | YBX1 |

| 40S Ribosome (20 subunits) | 40S |

To confirm the association of TDP-43 with stress granules, we performed immunofluorescence to examine two additional stress granule proteins (EIF4G and G3BP1) that are also known to associate with stress granules. FLAG-TDP-43 was found to strongly co-localize with these proteins in discrete cytoplasmic puncta clearly indicating that cytoplasmic TDP-43 associates with stress granules (Figure 5B-C). Furthermore, endogenous TDP-43 was found to localize to stress granule markers following challenge with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132, a well-established stimulus of stress granule formation (Figure 5D).

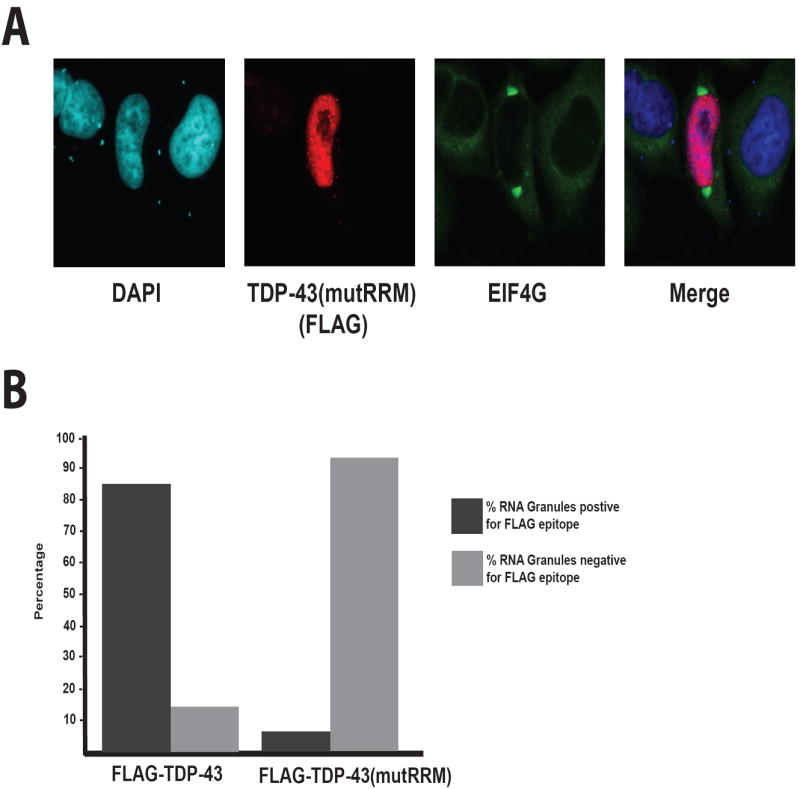

To determine whether RNA binding is necessary for TDP-43 localization to stress granules, we visualized the localization of FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) and EIF4G as a marker for RNA granules. The localization of FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) remains predominantly nuclear, although the presence of tiny discreet puncta is observed in many cells that have both nuclear and cytoplasmic localization that do not co-localize with stress granules (Figure 6). FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) was found to be present in only 6.5% of stress granules whereas FLAG-TDP-43 was found to be present in 84.7% of stress granules (Figure 6). This indicates that the association of TDP-43 with stress granules is strongly impaired by an inability to interact with RNA.

Figure 6. TDP-43 association with stress granules is strongly mitigated by inability to bind RNA.

(A) TDP-43(mutRRM) was rarely found in cytoplasmic RNA granules (as visualized by EIF4G). (B) In FLAG-TDP-43 expressing cells, FLAG-TDP-43 was found to co-localize with EIF4G in 85% of stress granules (n=242 cells) whereas FLAG-TDP-43(mutRRM) was found in only 6.5% of stress granules (n=168 cells).

Discussion

Using a global proteomic approach we have demonstrated that TDP-43 has extensive interaction with proteins that regulate mRNA metabolism. These include nuclear proteins, cytoplasmic proteins, and proteins known to undergo nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Among TDP-43’s interactors are hnRNPs, RNA helicases, splicing factors, translation regulatory proteins, as well as proteins involved in mRNA transport and stability. TDP-43 was found to interact with a smaller number of DNA binding proteins such as transcription factors, consistent with a previously described role for TDP-43 in transcriptional repression1, but also interactions with DNA repair proteins such as Ku70 suggesting that TDP-43 may be involved in other aspects of DNA metabolism.

Disease-associated mutations in TDP-43 are nearly all located within a C-terminal glycine-rich domain that has previously been found to interact with some hnRNPs5-9,11. Surprisingly, the disease-causing mutations A315T and M337V do not alter the profile of TDP-43 interactions in 293T cells. Analysis using the STRING database of protein-protein interactions demonstrates that TDP-43 associates with two distinct protein interaction networks. The first is a network of nuclear proteins that regulate RNA splicing and other aspects of nuclear RNA metabolism, consistent with prior evidence that TDP-43 can influence transcription and RNA splicing10. The second is a network of cytoplasmic proteins that regulate mRNA translation. Although a predominantly nuclear protein, it has been previously shown that TDP-43 shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm12. Moreover, TDP-43 has been found to redistribute to cytoplasmic RNA granules in response to neuronal injury13, 14. This is consistent with our finding that TDP-43 has extensive interaction with components of stress granules and that TDP-43 colocalizes with stress granules.

TDP-43 is a relatively new player in a growing list of RNA binding proteins that are associated with disease30. In addition to TDP-43, there are at least two other RNA binding proteins in which mutations lead to motor neuron disease. Loss of function mutations affecting the SMN gene cause spinal muscular atrophy31 whereas mutation in the SR protein FUS/TLS also leads to dominantly inherited ALS32, 33. Furthermore, a large number of additional neurodegenerative diseases are also associated with mutations in RNA binding proteins indicating that defects in RNA metabolism may be a common underlying mechanism causing neurodegeneration30. Our work suggests that TDP-43 may play a role in regulation of mRNA at multiple levels that may include transcription, stability, trafficking and translation. Other RNA binding proteins mutated in neurodegenerative disease are similarly multifunctional, including SMN, FUS/TLS, and FMRP. It remains to be determined whether any one particular aspect of RNA metabolism is perturbed in common amongst these diseases.

TDP-43 has a well described role in the nucleus in the negative regulation of splicing, specifically it has been shown to promote exon skipping by direct interaction with the CFTR mRNA34. In the cytoplasm, TDP-43 has been shown to stabilize the mRNA of the neurofilament light chain through direct interaction with mRNA17. Recently, it has been shown that TDP-43 interacts with 14-3-3 protein subunits (also identified in our screen) to modulate the stability of the NFL mRNA35. Another intriguing possibility is that TDP-43 is required for site specific translation of specific mRNAs. Previous work has shown localization of TDP-43 in RNA granules in the dendrites of hippocampal neurons and repression of translation in vitro36. Altered regulation of site specific translation of mRNAs in motor neurons may prove to be an important mechanism leading to development of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Thus, future studies will be required to determine specific mRNAs that associate with TDP-43 in neurons.

TDP-43 pathology in ALS, FTLD-TDP and IBMPFD is typically characterized by clearance of TDP-43 from the nucleus and accumulation in the cytoplasm of affected cells2. Thus, diseases mediated by TDP-43 could involve loss of TDP-43 nuclear function or gain of a toxic of function in the cytoplasm. Given the dominant mode of inheritance of ALS associated with TDP-43 mutations5-7, and insight derived from our Drosophila model of TDP-43-related disease (Ritson et al. submitted) we hypothesize that toxic gain of cytoplasmic function is more likely.

Conclusion

TDP-43 associates with two distinct protein interaction networks, one implicated in RNA metabolism nucleus and the other involved in mRNA metabolism in the cytoplasm. Many of these interactions are dependent upon the ability of TDP-43 to bind RNA. TDP-43 interactions are not altered by two mutations that are causative of ALS. The association of TDP-43 with translational machinery, as well as histological evidence of TDP-43 assocaition with stress granules, strongly suggests that TDP-43 plays a role in translational regulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the Taylor lab, particularly Natalia Nedelsky, for helpful discussion and advice. This work was supported by NIH grant AG031587 and a grant from the Packard Foundation for ALS Research at Johns Hopkins to JPT.

References

- 1.Ou SH, Wu F, Harrich D, Garcia-Martinez LF, Gaynor RB. Cloning and characterization of a novel cellular protein, TDP-43, that binds to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 TAR DNA sequence motifs. J Virol. 1995;69(6):3584–96. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3584-3596.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, Truax AC, Micsenyi MC, Chou TT, Bruce J, Schuck T, Grossman M, Clark CM, McCluskey LF, Miller BL, Masliah E, Mackenzie IR, Feldman H, Feiden W, Kretzschmar HA, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314(5796):130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neumann M, Mackenzie IR, Cairns NJ, Boyer PJ, Markesbery WR, Smith CD, Taylor JP, Kretzschmar HA, Kimonis VE, Forman MS. TDP-43 in the ubiquitin pathology of frontotemporal dementia with VCP gene mutations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66(2):152–7. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31803020b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Kwong LK, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, frontotemporal dementia and beyond: the TDP-43 diseases. J Neurol. 2009;256(8):1205–14. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5069-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sreedharan J, Blair IP, Tripathi VB, Hu X, Vance C, Rogelj B, Ackerley S, Durnall JC, Williams KL, Buratti E, Baralle F, de Belleroche J, Mitchell JD, Leigh PN, Al-Chalabi A, Miller CC, Nicholson G, Shaw CE. TDP-43 mutations in familial and sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2008;319(5870):1668–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1154584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gitcho MA, Baloh RH, Chakraverty S, Mayo K, Norton JB, Levitch D, Hatanpaa KJ, White CL, 3, Bigio EH, Caselli R, Baker M, Al-Lozi MT, Morris JC, Pestronk A, Rademakers R, Goate AM, Cairns NJ. TDP-43 A315T mutation in familial motor neuron disease. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(4):535–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.21344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kabashi E, Valdmanis PN, Dion P, Spiegelman D, McConkey BJ, Vande Velde C, Bouchard JP, Lacomblez L, Pochigaeva K, Salachas F, Pradat PF, Camu W, Meininger V, Dupre N, Rouleau GA. TARDBP mutations in individuals with sporadic and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):572–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutherford NJ, Zhang YJ, Baker M, Gass JM, Finch NA, Xu YF, Stewart H, Kelley BJ, Kuntz K, Crook RJ, Sreedharan J, Vance C, Sorenson E, Lippa C, Bigio EH, Geschwind DH, Knopman DS, Mitsumoto H, Petersen RC, Cashman NR, Hutton M, Shaw CE, Boylan KB, Boeve B, Graff-Radford NR, Wszolek ZK, Caselli RJ, Dickson DW, Mackenzie IR, Petrucelli L, Rademakers R. Novel mutations in TARDBP (TDP-43) in patients with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(9):e1000193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borroni B, Bonvicini C, Alberici A, Buratti E, Agosti C, Archetti S, Papetti A, Stuani C, Di Luca M, Gennarelli M, Padovani A. Mutation within TARDBP leads to Frontotemporal Dementia without motor neuron disease. Hum Mutat. 2009 doi: 10.1002/humu.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Multiple roles of TDP-43 in gene expression, splicing regulation, and human disease. FrontBiosci. 2008;13:867–78. doi: 10.2741/2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buratti E, Brindisi A, Giombi M, Tisminetzky S, Ayala YM, Baralle FE. TDP-43 binds heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B through its C-terminal tail: an important region for the inhibition of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator exon 9 splicing. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37572–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505557200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayala YM, Zago P, D’Ambrogio A, Xu YF, Petrucelli L, Buratti E, Baralle FE. Structural determinants of the cellular localization and shuttling of TDP-43. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 22):3778–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.038950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moisse K, Volkening K, Leystra-Lantz C, Welch I, Hill T, Strong MJ. Divergent patterns of cytosolic TDP-43 and neuronal progranulin expression following axotomy: implications for TDP-43 in the physiological response to neuronal injury. Brain Res. 2009;1249:202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moisse K, Mepham J, Volkening K, Welch I, Hill T, Strong MJ. Cytosolic TDP-43 expression following axotomy is associated with caspase 3 activation in NFL(-/-) mice: Support for a role for TDP-43 in the physiological response to neuronal injury. Brain Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buratti E, Baralle FE. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(39):36337–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abhyankar MM, Urekar C, Reddi PP. A novel CpG-free vertebrate insulator silences the testis-specific SP-10 gene in somatic tissues: role for TDP-43 in insulator function. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(50):36143–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705811200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strong MJ, Volkening K, Hammond R, Yang W, Strong W, Leystra-Lantz C, Shoesmith C. TDP43 is a human low molecular weight neurofilament (hNFL) niRNA-binding protein. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35(2):320–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(18):3551–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keller A, Nesvizhskii AI, Kolker E, Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem. 2002;74(20):5383–92. doi: 10.1021/ac025747h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nesvizhskii AI, Keller A, Kolker E, Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2003;75(17):4646–58. doi: 10.1021/ac0341261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen LJ, Kuhn M, Stark M, Chaffron S, Creevey C, Muller J, Doerks T, Julien P, Roth A, Simonovic M, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING 8--a global view on proteins and their functional interactions in 630 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Database issue):D412–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ayala YM, Pantano S, D’Ambrogio A, Buratti E, Brindisi A, Marchetti C, Romano M, Baralle FE. Human, Drosophila, and C.elegans TDP43: nucleic acid binding properties and splicing regulatory function. J Mol Biol. 2005;348(3):575–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou MY, Rooke N, Turck CW, Black DL. hnRNP H is a component of a splicing enhancer complex that activates a c-src alternative exon in neuronal cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(1):69–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bernstein P, Peltz SW, Ross J. The poly(A)-poly(A)-binding protein complex is a major determinant of mRNA stability in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9(2):659–70. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sachs AB, Davis RW. The poly(A) binding protein is required for poly(A) shortening and 60S ribosomal subunit-dependent translation initiation. Cell. 1989;58(5):857–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90938-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann I, Casella M, Schnolzer M, Schlechter T, Spring H, Franke WW. Identification of the junctional plaque protein plakophilin 3 in cytoplasmic particles containing RNA-binding proteins and the recruitment of plakophilins 1 and 3 to stress granules. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(3):1388–98. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elvira G, Wasiak S, Blandford V, Tong XK, Serrano A, Fan X, del Rayo Sanchez-Carbente M, Servant F, Bell AW, Boismenu D, Lacaille JC, McPherson PS, DesGroseillers L, Sossin WS. Characterization of an RNA granule from developing brain. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5(4):635–51. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500255-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules: post-transcriptional and epigenetic modulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(6):430–6. doi: 10.1038/nrm2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33(3):141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper TA, Wan L, Dreyfuss G. RNA and disease. Cell. 2009;136(4):777–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Benichou B, Cruaud C, Millasseau P, Zeviani M, et al. Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell. 1995;80(1):155–65. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, Davis A, Gilchrist J, Kasarskis EJ, Munsat T, Valdmanis P, Rouleau GA, Hosler BA, Cortelli P, de Jong PJ, Yoshinaga Y, Haines JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Yan J, Ticozzi N, Siddique T, McKenna-Yasek D, Sapp PC, Horvitz HR, Landers JE, Brown RH., Jr Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2009;323(5918):1205–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vance C, Rogelj B, Hortobagyi T, De Vos KJ, Nishimura AL, Sreedharan J, Hu X, Smith B, Ruddy D, Wright P, Ganesalingam J, Williams KL, Tripathi V, Al-Saraj S, Al-Chalabi A, Leigh PN, Blair IP, Nicholson G, de Belleroche J, Gallo JM, Miller CC, Shaw CE. Mutations in FUS, an RNA processing protein, cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis type 6. Science. 2009;323(5918):1208–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1165942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buratti E, Dork T, Zuccato E, Pagani F, Romano M, Baralle FE. Nuclear factor TDP-43 and SR proteins promote in vitro and in vivo CFTR exon 9 skipping. EMBO J. 2001;20(7):1774–84. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volkening K, Leystra-Lantz C, Yang W, Jaffee H, Strong MJ. Tar DNA binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43), 14-3-3 proteins and copper/zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD1) interact to modulate NFL mRNA stability. Implications for altered RNA processing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) Brain Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang IF, Wu LS, Chang HY, Shen CK. TDP-43, the signature protein of FTLD-U, is a neuronal activity-responsive factor. J Neurochem. 2008;105(3):797–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.