In the article by La Merrill et al. [Environ Health Perspect 117:1414–1419 (2009)], the keys in Figure 3B and Figure 5C should have been in Figure 3C and Figure 5D, respectively. The corrected figures are provided below.

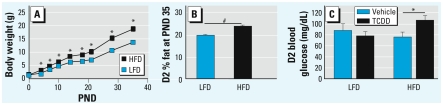

Figure 3.

Diet and maternal TCDD exposure effects on body composition and fasting blood glucose. (A) HFD increased postnatal D2 body weights (mean ± SE; n = 27–31 at PNDs 0–26 for HFD, and n = 28 at PND35 for LFD). (B) HFD (n = 26 mice) increased percent fat at PND35 relative to LFD (mean ± SE; n = 28 mice). (C) Fasting blood glucose was increased by HFD and maternal TCDD-treated (n = 5 litters) compared with HFD and maternal vehicle-treated (n = 6 litters) female progeny at PND36 (mean ± SE). Because diet, but not TCDD, changed body weight and percent body fat, these analyses were done on individual D2 mice, with TCDD- and vehicle-treated D2 mice pooled within diet.

*p < 0.05. #p < 0.0001.

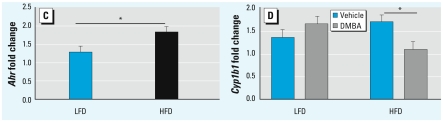

Figure 5.

Maternal TCDD exposure and effect of diet on gene expression. Normalized message levels are represented as mean ± SE. (C) Induction of Ahr was increased by HFD relative to LFD (n = 11 and 10 litters, respectively). Measurements were pooled across TCDD and DMBA groups. (D) Induction of Cyp1b1 by DMBA was decreased compared with vehicle in HFD-fed but not in LFD-fed D2 mice. LFD groups are vehicle (n = 5 litters) and DMBA (n = 5 litters); HFD groups are vehicle (n = 6 litters) and DMBA (n = 5 litters).

*p < 0.05.

EHP apologizes for the errors.