Abstract

Streptomyces ambofaciens synthesizes spiramycin, a 16-membered macrolide antibiotic used in human medicine. The spiramycin molecule consists of a polyketide lactone ring (platenolide) synthesized by a type I polyketide synthase, to which three deoxyhexoses (mycaminose, forosamine, and mycarose) are attached successively in this order. These sugars are essential to the antibacterial activity of spiramycin. We previously identified four genes in the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster predicted to encode glycosyltransferases. We individually deleted each of these four genes and showed that three of them were required for spiramycin biosynthesis. The role of each of the three glycosyltransferases in spiramycin biosynthesis was determined by identifying the biosynthetic intermediates accumulated by the corresponding mutant strains. This led to the identification of the glycosyltransferase responsible for the attachment of each of the three sugars. Moreover, two genes encoding putative glycosyltransferase auxiliary proteins were also identified in the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster. When these two genes were deleted, one of them was found to be dispensable for spiramycin biosynthesis. However, analysis of the biosynthetic intermediates accumulated by mutant strains devoid of each of the auxiliary proteins (or of both of them), together with complementation experiments, revealed the interplay of glycosyltransferases with the auxiliary proteins. One of the auxiliary proteins interacted efficiently with the two glycosyltransferases transferring mycaminose and forosamine while the other auxiliary protein interacted only with the mycaminosyltransferase.

Macrolide antibiotics consist of a polyketide macrolactone ring to which one or more deoxysugars are attached. They inhibit protein synthesis by binding to the large subunit of the ribosome and can also, in some cases, interfere with the assembly of the large subunit (reviewed in reference 19). As with many other natural products, glycosylation of macrolides is essential for their biological activity. The determination of the three-dimensional structure of the 50S ribosomal unit in complex with various macrolides showed that the sugar moieties are involved in specific interactions with the 23S rRNA (11, 38). All macrolides block the ribosomal peptide exit tunnel, thus preventing peptide chain elongation. In addition to their role in binding, the sugars are also important for steric hindrance in the tunnel. For instance, it was shown that the C-5 disaccharide moieties of some 16-membered macrolides, such as spiramycin or tylosin, extend in the tunnel toward the peptidyl transferase center, and a correlation could be established between the length of the macrolide saccharide side chain and the number of amino acids which could be incorporated before peptide chain elongation was blocked (11).

One of the most common resistance mechanisms to macrolide antibiotics encountered in pathogenic bacteria involves target modification. These modifications could include mutation or methylation of the 23S residues involved in the interaction with macrolide antibiotics (30, 35, 40). Molecular modeling helped to explain how these modifications could hamper the binding of macrolides to modified ribosomes (11, 22). Taken together, these studies suggested that modification of the glycosylation pattern of macrolides was a way to obtain new macrolides with enhanced or modified affinities for their targets, which could help to circumvent some resistance mechanisms. As a consequence, many studies were undertaken to characterize the biosynthetic pathways of the sugars present in macrolides and the glycosyltransferases involved in their attachment to the macrolactone ring (for a review, see references 23, 26, and 36). The resulting knowledge was applied for the generation of novel compounds by combinatorial biology (34, 36). To be successful, these approaches rely on the availability of macrolide glycosyltransferases with a certain degree of substrate flexibility regarding the sugar donor and/or the aglycone acceptor. In this perspective, it is interesting to characterize the glycosyltransferases involved in the glycosylation of various macrolide antibiotics.

It was recently discovered that some glycosyltransferases require an auxiliary activator protein for full activity. This was determined during the study of DesVII, a glycosyltransferase that catalyzes the attachment of desosamine onto 12- and 14-membered macrolactone rings during the biosynthesis of the macrolide antibiotics methymycin and pikromycin in Streptomyces venezuelae. For glycosylation to proceed efficiently, the presence of an auxiliary protein, DesVIII, was found to be necessary in vivo as well as in vitro (2, 3, 12, 13). Since the discovery of the role of DesVIII in glycosylation, other pairs of glycosyltransferases and auxiliary proteins have been identified and characterized, and most of these are involved in macrolide biosynthesis (14, 24, 25). However, the mechanistic role of these auxiliary proteins remains unclear. Auxiliary proteins are most probably not involved in the transfer itself. Indeed, it has been observed that the auxiliary protein is required for the initial activation of the glycosyltransferase, but then the activated glycosyltransferase can catalyze the glycosyltransfer alone. It was thus proposed that auxiliary proteins induce a one-time conformational change of the glycosyltransferase to its active form (2).

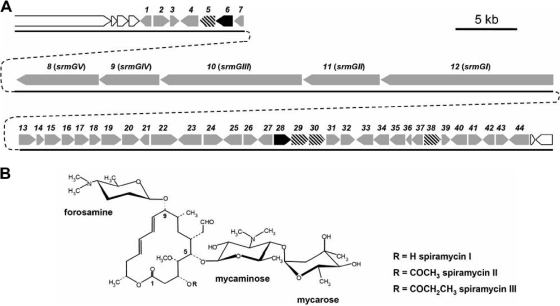

Spiramycin is a macrolide antibiotic used in human medicine. It is synthesized by Streptomyces ambofaciens and consists of a 16-membered polyketide lactone ring (platenolide) with two amino deoxyhexoses (mycaminose and forosamine) and one neutral deoxyhexose (mycarose) attached (Fig. 1 A). As the result of several studies (reference 18 and references therein), the complete sequence and organization of the gene cluster directing the biosynthesis of spiramycin have been determined (Fig. 1B). It was therefore possible to address the question of glycosylation in spiramycin biosynthesis by inactivating genes putatively involved in glycosylation and then characterizing the resulting mutant strains.

FIG. 1.

(A) The spiramycin molecules. (B) The spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster. Genes encoding putative glycosyltransferases are represented by dashed arrows, and those encoding putative auxiliary proteins are represented by black arrows.

We report here the identification of the three genes encoding the glycosyltransferases responsible for sugar attachment in spiramycin biosynthesis, the determination of the sugar attached by each of these enzymes, and the interplay of two of these glycosyltransferases with two auxiliary proteins encoded in the cluster.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Standard media and culture conditions were used for Escherichia coli and Streptomyces strains (20, 37). The following antibiotics were incorporated in the medium when required for selection: ampicillin (Amp), thiostrepton (Tsr), apramycin (Apr), hygromycin B (Hyg), and puromycin (Pur). For spiramycin production, Streptomyces strains were grown in MP5 medium (29). The detection and quantification of spiramycin in culture supernatants by bioassays or by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) were performed as previously described (9). Spiramycin I, II, and III were used as standards for quantification by HPLC.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| ATCC 23877 | Wild-type S. ambofaciens strain | ATCC |

| OSC2 | Derivative of S. ambofaciens ATCC 23877 devoid of pSAM2 | 33 |

| SPM102 | Δsrm29::att3aac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM103 | Δsrm30::att3aac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM104 | Δsrm38::att3aac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM120 | Δsrm5::att3aac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM108 | Δsrm29::att3 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM109 | Δsrm30::att3 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM110 | Δsrm38::att3 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM121 | Δsrm5::att3 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM209 | Δsrm28::att2Ωaac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM211 | Δsrm6::att2Ωaac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM212 | Δsrm28::att2 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM213 | Δsrm6::att2 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM214 | Δsrm28::att2 Δsrm6::att2Ωaac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM215 | Δsrm28::att2 Δsrm6::att2 in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM216 | Δsrm29::att3 Δsrm6::att2Ωaac in OSC2 | This work |

| SPM217 | Δsrm29::att3 Δsrm6::att2 in OSC2 | This work |

| DH5α | General cloning host strain | Promega |

| S17-1 | Host strain for conjugation from E. coli to S. ambofaciens | 39 |

| DY330 | Used for PCR-targeted mutagenesis | 43 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEMTeasy | Ampr; E. coli vector for cloning PCR product | Promega |

| pUWL201 | Ampr Tsrr; E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector for gene expression in S. ambofaciens under the control of the ermE*p promoter | 6 |

| pOSV554 | Aprr; E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector for gene expression in S. ambofaciens under the control of the ermE*p promoter | Darbon et al., unpublished |

| pOSV234 | Ampr Aprr; att3aac cassette (33) cloned into the vector pGP704Not (5, 27) | This work |

| pOSV221 | Ampr Aprr; att2Ωaac cassette (33) cloned into the vector pGP704Not (5, 27) | This work |

| pOSV508 | Ampr Tsrr; E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle plasmid expressing the Xis and Int proteins for site-specific excision of excisable cassettes | 33 |

| pOSV236 | Ampr Tsrr PurroriT; E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle plasmid expressing the Xis and Int proteins for site-specific excision of excisable cassettes. Derived from pOSV508 (33) | This work |

| pSPM36 | Ampr PurroriT; cosmid from the S. ambofaciens OSC2 gene library containing part of the spiramycin cluster | 18 |

| pSPM45 | Ampr PurroriT; cosmid from the S. ambofaciens OSC2 gene library containing part of the spiramycin cluster | 17 |

| pSPM47 | Ampr PurroriT; cosmid from the S. ambofaciens OSC2 gene library containing part of the spiramycin cluster | 17 |

| pSPM209 | Ampr Aprr Purr; srm28 inactivation (srm28::att2Ωaac) by PCR targeting into pSPM45 | This work |

| pSPM102 | Ampr Aprr Purr; srm29 inactivation (srm29::att3aac) by PCR targeting into pSPM45 | This work |

| pSPM103 | Ampr Aprr Purr; srm30 inactivation (srm30::att3aac) by PCR targeting into pSPM45 | This work |

| pSPM104 | Ampr Aprr,Purr; srm38 inactivation (srm38::att3aac) by PCR targeting into pSPM36 | This work |

| pSPM120 | Ampr Aprr Purr; srm5 inactivation (srm5::att3aac) by PCR targeting into pSPM47 | This work |

| pSPM220 | Ampr Aprr Purr; srm6 inactivation (srm6::att2Ωaac) by PCR targeting into pSPM45 | This work |

| pSPM224 | Aprr; coding sequence of srm28 cloned into pOSV554 | This work |

| pSPM154 | Ampr Tsrr; coding sequence of srm29 cloned into pUWL201 | This work |

| pSPM129 | Ampr Tsrr; coding sequence of srm38 cloned into pUWL201 | This work |

| pSPM133 | Ampr Tsrr; coding sequence of srm5 cloned into pUWL201 | This work |

| pSPM222 | Aprr; coding sequence of srm6 cloned into pOSV554 | This work |

Gene nomenclature.

Some genes of the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster were named previously, for instance, srmGI to srmGIV for the polyketide synthase (PKS) genes (21) or srmB, srmR, and srmX for a resistance gene, a regulatory gene, and a biosynthetic gene, respectively (8). When the complete sequence of the gene cluster was determined by Karray et al. (18), the putative spiramycin genes identified were named orf followed by a number as follows: the designations orf1 to orf34c were used for the ones upstream of the PKS genes, with orf1 close to srmGI, and the designations orf1*c to orf11* were used for the ones downstream of the PKS, with orf1*c being close to srmGIV. But this nomenclature raised several problems. Therefore, a new nomenclature is now used in which the genes are named srm followed by a number, in ascending order from left to right across the cluster (from srm1 to srm44).

Preparation and manipulation of DNA.

DNA extraction from E. coli and Streptomyces, in vitro DNA manipulation, bacterial transformation with DNA, and introduction of DNA in Streptomyces by E. coli-Streptomyces intergenic transfer were performed according to well-established protocols (20, 37). DNA amplification by PCR was carried out using either Taq polymerase from Qiagen or a GC-rich PCR system from Roche. The oligonucleotides used as primers in this study are listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| KF230 | AGCTGGCCGACCGCGAACTGGGGCGCAGACTGCACCGGATATCT ACCTCTTCGTCCCGAAGCAACT | Forward primer for deletion of srm28 |

| KF231 | GCACGCCCAGCGCGGTCTCGGCGGCACGGCCGACGAACTCATCGGCGCGCTTCGTTCGGGACGAAG | Reverse primer for deletion of srm28 |

| KF44 | TACCACCTGGTACCGCTGATCTGGGCTCTGCGTGCCTCGGATCGCGCGCGCTTCGTTCGGGACGAA | Forward primer for deletion of srm29 |

| KF45 | GGGCGGCGGAGTTCTGCGCGAACATGTGCTGCCGTACGGCATCTGCCTCTTCGTCCCGAAGCAACT | Reverse primer for deletion of srm29 |

| KF46 | CCGCTCGCGGGCCACCTGCTTCCGCTGGTGCCCATCGCGTATCGCGCGCGCTTCGTTCGGGACGAA | Forward primer for deletion of srm30 |

| KF47 | GCGCCATCTCCTCGGCGAGCCCGGCTGCCGCCTTGGCATAATCTGCCTCTTCGTCCCGAAGCAACT | Reverse primer for deletion of srm30 |

| KF48 | CCGGGCATGTGAATCCGACCCTGGGAGTCGCCGAGGAACTATCGCGCGCGCTTCGTTCGGGACGAA | Forward primer for deletion of srm38 |

| KF49 | CCGCCGGCCGCCCTGATCTGCTCCCGGAACCCGCGCATGTATCTGCCTCTTCGTCCCGAAGCAACT | Reverse primer for deletion of srm38 |

| KF77 | CATCTCCTCGCTCAGCCGCCGCGCGCCCGCCCTGATCGCGATCGCGCGCGCTTCGTTCGGGACGAA | Forward primer for deletion of srm5 |

| KF78 | GAGCCCGCCCTCCCTCACCGACGTCATCACCTCCACCGGCATCTGCCTCTTCGTCCCGAAGCAACT | Reverse primer for deletion of srm5 |

| Del.srm6F | GCGGCCGGGTCAGGGGCGGTCCCTCGGCCCGCAGGCCGGGATCTACCTCTTCGTCCCGAAGCAACT | Forward primer for deletion of srm6 |

| Del.srm6R | CGGACACGAGCACGGGCGTCCGTGCGCTCGGCCGTCGGCTATCGGCGCGCTTCGTTCGGGACGAAG | Reverse primer for deletion of srm6 |

| Orf16F | CGACGCAGGTCAGCACGGTG | Confirmation of srm28 disruption |

| Orf16R | CAGGTCATCCACTCCGCGAC | Confirmation of srm28 disruption |

| KF54 | GTGACCTCCATCCCGCACCACACGC | Confirmation of srm29 disruption |

| KF55 | GGCTCCTCGAGCAGGCGCACCAGCG | Confirmation of srm29 disruption |

| KF56 | GGGCCCTCTTCACGACCGCGCCGCT | Confirmation of srm30 disruption |

| KF57 | GGTAACTCCGCGGCATGTCCGGCCC | Confirmation of srm30 disruption |

| KF58 | CTTCCGGTTGCCGGGCATGTGAATC | Confirmation of srm38 disruption |

| KF59 | GCAGCAGTCCCTCGATCGCGTCGGC | Confirmation of srm38 disruption |

| KF79 | GTGCAGGGCGGTGAGGCGCTCCAGG | Confirmation of srm5 disruption |

| KF80 | CTGCGCGCCGCCGGGCACGAGGTAC | Confirmation of srm5 disruption |

| Srm6F | CGCGGCCCGGAGGCGGGTTG | Confirmation of srm6 disruption |

| Srm6R | AGCGCCCAGGCGAGGGGCAC | Confirmation of srm6 disruption |

| OE.srm28F | ATAAAGCTTAATCTGTGGACGGGGCGGTG | Forward primer for amplification of srm28 |

| OE.srm28R | ATACTGCAGCAGGACGCGCACGGCACTCC | Reverse primer for amplification of srm28 |

| KF98 | AAGCTTGGGCCCGCGGCCGGCGTCCCCT | Forward primer for amplification of srm29 |

| KF97 | GGATCCTGCAGGGCCCGCGCGCCGGTTCA | Reverse primer for amplification of srm29 |

| KF83 | AAGCTTCGACGCATGAAGGGTTTCACATGGCTCAT | Forward primer for amplification of srm38 |

| KF84 | GGATCCACGTCTCAGCCCACCCGGGGCAGCAGTCC | Reverse primer for amplification of srm38 |

| KF90 | AAGCTTGAGAAGGGAGCGGACATGTGCGCGTCCTGCTGACATC | Forward primer for amplification of srm5 |

| KF91 | GGATCCTGCAGAACATGTCGGTGTCCTCTTTGCGGACGGTCAC | Reverse primer for amplification of srm5 |

| OE.srm6F | ATAAAGCTTCGCGGCCCGGAGGCGGGTTG | Forward primer for amplification of srm6 |

| OE.srm6R | ATACTGCAGAGCGCCCAGGCGAGGGGCAC | Reverse primer for amplification of srm6 |

Construction of the excisable cassettes att1aac, att2aac, and att3aac.

These cassettes are similar to the excisable cassettes att1Ωaac, att2Ωaac, and att3Ωaac previously described (33) except that the terminators originating from the Ω interposon (31) and flanking the apramycin resistance gene in Ωaac (1) are absent in these excisable cassettes.

Inactivation of srm5, srm6, srm28, srm29, srm30, and srm38 by in-frame deletion in S. ambofaciens.

PCR targeting (5, 10, 43) was used to inactivate the srm5, srm6, srm28, srm29, srm30, and srm38 genes. The cosmids pSPM36, pSPM45, and pSPM47 were used in these experiments. They all contain large regions of the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster cloned into the cosmid pWED2 (18). This vector is unable to replicate in Streptomyces, but it contains the pac gene conferring puromycin resistance in Streptomyces and the oriT sequence for efficient interspecific transfer from E. coli to Streptomyces. The general procedure was as follows. The gene targeted for replacement and located in the cosmid insert was replaced by a resistance cassette via λRED-mediated recombination. For this purpose, the E. coli DY330 strain harboring the cosmid was transformed with PCR products corresponding to the cassette flanked by short sequences identical to both extremities of the coding sequence from the targeted gene. The cassettes used (att2Ωaac and att3aac) confer apramycin resistance in E. coli and Streptomyces. The modified cosmids were checked by restriction analysis and PCR. A cosmid in which the targeted gene had been replaced by the cassette was then introduced into S. ambofaciens by protoplast transformation or intergenic conjugation, with E. coli S17-1 as the donor strain. After selection for apramycin resistance, the colonies obtained were screened to find apramycin-resistant and puromycin-sensitive S. ambofaciens clones in which gene replacement had occurred after recombination on each side of the targeted gene. The gene replacement in S. ambofaciens was confirmed by PCR or Southern blot analysis. For each gene replacement experiment, at least one clone was chosen for further studies. In order to excise the apramycin resistance cassette, the plasmid pOSV508 or its derivative pOSV236 was introduced into the mutant strain. The plasmid pOSV236 was constructed by cloning a fragment containing the pac-oriT sequence of pWED2 (18) into the EcoRV site of pOSV508. These plasmids express the excisionase and integrase from pSAM2. As a result, the apramycin resistance cassette was excised through site-specific recombination, leading to in-frame deletion of the targeted gene. After loss of the unstable pOSV508 or pOSV236 plasmid, the in-frame deletion of the targeted gene was verified by PCR amplification and sequencing of the PCR product.

Using this procedure, sequences of 1,013 bp from srm5, 1,093 bp from srm6, 1,033 bp from srm28, 965 bp from srm29, 980 bp from srm30, and 1,052 bp from srm38 were replaced by apramycin resistance cassettes. The excisable cassette att3aac, leaving a scar sequence of 35 bp after excision, was used for the deletion of srm5, srm29, srm30, and srm38 for which 3n + 2 bp were deleted, where n is any integer. The excisable cassette att2Ωaac, leaving a scar sequence of 34 bp after excision, was used for the deletion of srm6 and srm28 for which 3n + 1 bp were deleted. The primer pairs used in the PCR amplifications are presented in Table 2. The resulting recombinant cosmids obtained after PCR targeting are presented in Table 1. After gene replacement in S. ambofaciens and excision of the cassette, the strains SPM121 (Δsrm5::att3), SPM213 (Δsrm6::att2), SPM212 (Δsrm28::att2), SPM108 (Δsrm29::att3), SPM109 (Δsrm30::att3), and SPM110 (Δsrm38::att3) were obtained.

Strains in which two genes were inactivated were constructed by successive deletion of the genes. Strain SPM212 (Δsrm28::att2) was transformed with the cosmid pSPM220 to inactivate srm6. After gene replacement and excision of the cassette, the resulting mutant strain was named SPM215 (Δsrm6::att2 Δsrm28::att2). Strain SPM108 (Δsrm29::att3) was transformed with the cosmid pSPM220 to inactivate srm6. After gene replacement and excision of the cassette, the resulting mutant strain was named SPM217 (Δsrm6::att2 Δsrm29::att3).

Complementation of the mutants.

For complementation, the glycosyltransferase and auxiliary protein genes were expressed under the control of the constitutive promoter ermE*p, using either the multicopy vector pUWL201 (6) or the integrative vector pOSV554 (E. Darbon et al., unpublished data). The srm5, srm6, srm28, srm29, and srm38 genes were PCR amplified using a GC-rich PCR system (Roche) and the primer pairs KF90/KF91 (srm5), OE.srm6F/OE.srm6R (srm6), OE.srm28F/OE.srm28R (srm28), KF98/KF97 (srm29), and KF83/KF84 (srm38), respectively. The PCR products were then cloned into pGEMT-Easy, and their sequences were verified. The genes were then cloned as HindIII-PstI fragments into either pOSV554 (srm6 and srm28) or pUWL201 (srm29) or as HindIII-BamHI fragments into pUWL201 (srm5 and srm38), yielding the plasmids pSPM133 for srm5, pSPM222 for srm6, pSPM224 for srm28, pSPM154 for srm29, and pSPM129 for srm38. These constructs were introduced into S. ambofaciens mutants either by protoplast transformation (pSPM154, pSPM129, and pSPM133) or by conjugation (pSPM224 and pSPM222).

LC-MS analyses.

After 4 days of culture at 26°C, supernatants were filtered through an Ultrafree-MC filter unit (0.1-μm pore size; Millipore) and analyzed on an Atlantis dC18 column (250 mm by 4.6 mm; particle size, 5 μm; column temperature, 25°C) using an Agilent 1200 HPLC instrument equipped with a quaternary pump. Samples were eluted with isocratic 0.1% HCOOH in H2O (solvent A)-0.1% HCOOH in CH3CN (solvent B) (95:5) at 1 ml min−1 for 5 min, followed by a gradient to 50:50 solvent A/solvent B over 35 min. Spiramycins were detected by monitoring absorbance at 232 nm. A Bruker Daltonik Esquire HCT ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with an orthogonal atmospheric pressure interface-electrospray ionization (AP-ESI) source was used for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses. Elution from the Atlantis dC18 was split into two flows: 1/10 was directed to the ESI-mass spectrometer for MS and tandem MS (MS/MS) measurements, and the remaining 9/10 was directed to a diode array UV detector. In the ESI process, nitrogen served as the drying and nebulizing gas, and helium gas was introduced into the ion trap both for efficient trapping and cooling of the ions generated by the ESI and for fragmentation processes. Ionization was carried out in positive/negative mode with the nebulizing gas set at 241 kPa, the drying gas set at 8 μl/min, and the drying temperature set at 345°C for optimal spray and desolvation. Ionization and mass analysis conditions (capillary high voltage, skimmer and capillary exit voltages, and ion transfer parameters) were tuned for optimal detection of compounds in the range of masses between 50 and 1,000 m/z.

RESULTS

Putative glycosyltransferases and auxiliary proteins encoded in the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster.

There are three deoxysugar moieties in the spiramycin molecule: two amino sugars, mycaminose and forosamine, and one neutral sugar, mycarose (Fig. 1A). Enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of these sugars are encoded by genes in the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster (18). The analysis of the cluster revealed the presence of four genes (srm5, srm29, srm30, and srm38) encoding putative glycosyltransferases (18) (Fig. 1B). This was unexpected as there is usually one specific glycosyltransferase for each sugar to be transferred. To explain the discrepancy between the number of putative glycosyltransferases and the number of sugar moieties, several hypotheses can be formulated. For instance, one of these genes might not be expressed. However, transcriptional analysis of the cluster showed that all four genes are transcribed during spiramycin biosynthesis, and their transcription is coregulated with that of the other biosynthetic genes (F. Karray et al., unpublished data). Alternatively, the product of one of the genes might be inactive, but comparisons and alignments with the protein sequences of functional glycosyltransferases did not provide any obvious indication that this might be the case. In that light, if all of the glycosyltransferases are expressed and active, two of them could independently catalyze the attachment of the same sugar. Finally, one of the four glycosyltransferases may be involved in a process other than spiramycin biosynthesis, for instance, in macrolide resistance by drug inactivation, which has been observed in Streptomyces antibioticus, a producer of the macrolide oleandomycin (32).

In the spiramycin cluster, two genes (srm6 and srm28) encode putative glycosyltransferase auxiliary proteins. These two genes are located immediately upstream of putative glycosyltransferase genes (srm5 and srm29), as is generally the case. Gene clusters studied thus far contained only one gene coding for an auxiliary protein, and it has been shown that when several glycosyltransferases are encoded within the gene cluster, the auxiliary protein activates only the glycosyltransferase encoded next to the auxiliary protein gene in the cluster. However, it has been shown for DesVII, which requires the auxiliary protein DesVIII for its activity, that heterospecific auxiliary proteins can also activate DesVII in the absence of DesVIII, although with a reduced efficiency (14).

With four glycosyltransferases and two auxiliary proteins encoded within the spiramycin gene cluster, the situation appears complex and deserves further study. Moreover, this provides the opportunity to study the interplay of two auxiliary proteins with different glycosyltransferases in a natural situation. To address the questions on the roles of the different proteins in spiramycin glycosylation, the six genes encoding the putative glycosyltransferases or auxiliary proteins were inactivated, and the resulting mutant strains were studied.

Identification of the glycosyltransferases involved in spiramycin biosynthesis.

The wild-type strain OSC2 and the four mutant strains inactivated in one of the putative glycosyltransferase genes [SPM108 (Δsrm29::att3), SPM109 (Δsrm30::att3), SPM110 (Δsrm38::att3), and SPM121 (Δsrm5::att3)] were grown in the spiramycin production medium. The production of spiramycin by these strains was then analyzed by bioassays and HPLC; the results are presented in Table 3. Three of the four mutant strains no longer produced spiramycin, but one of them, SPM109 (Δsrm30::att3), still synthesized it. To verify that the lack of spiramycin production in the three nonproducing mutants was really due to the inactivation of the glycosyltransferase gene, complementation experiments were performed. When a glycosyltransferase gene cloned into a multicopy vector and transcribed from the constitutive ermE*p promoter was introduced into the corresponding mutant strain, spiramycin production was restored (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Spiramycin production by the wild-type strain and mutant strains in which the putative glycosyltransferase genes have been inactivated

| Straina | Characteristics | Spiramycin production |

|---|---|---|

| OSC2 | Wild type | + |

| SPM108 | Δsrm29::att3 in OSC2 | − |

| SPM109 | Δsrm30::att3 in OSC2 | + |

| SPM110 | Δsrm38::att3 in OSC2 | − |

| SPM121 | Δsrm5::att3 in OSC2 | − |

| SPM108(pSPM154) | Δsrm29::att3 in OSC2 complemented by srm29 | + |

| SPM110(pSPM129) | Δsrm38::att3 in OSC2 complemented by srm38 | + |

| SPM121(pSPM133) | Δsrm5::att3 in OSC2 complemented by srm5 | + |

The name of the plasmid harbored by the strain is given in parentheses.

These results indicated that three of the glycosyltransferase genes (srm5, srm29, and srm38) are involved in spiramycin biosynthesis. As the inactivation of srm30 had no effect on spiramycin biosynthesis, the role of this gene remains elusive.

Identification of the sugars added by the glycosyltransferases.

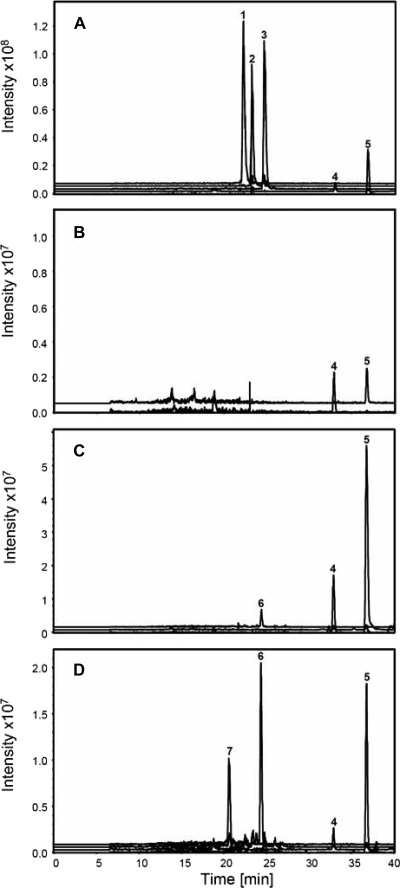

During spiramycin biosynthesis, the sugars are added in a preferred order (28). Mycaminose is the first sugar attached to platenolide, at C-5, yielding forocidin. Then, forosamine is attached to C-9, yielding neospiramycin. Mycarose is the last to be attached, and it is linked to mycaminose, to give spiramycin. As three glycosyltransferases seemed to be required for spiramycin biosynthesis, each of them should catalyze the incorporation of one specific sugar. Sequence comparisons with characterized enzymes that transfer mycaminose, mycarose, or forosamine and analyses performed with SEARCHGTr (a program for the analysis of glycosyltransferases involved in glycosylation of secondary metabolites [16]) did not allow us to make unambiguous predictions concerning the sugars transferred by the three glycosyltransferases. Thus, to determine the role of each glycosyltransferase, we used LC-MS to analyze the culture supernatant of the wild-type strain and of the mutant strains with deletions of a glycosyltransferase gene. The results are presented in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

LC-MS analysis of the metabolites produced by S. ambofaciens mutant strains. Extracted ion currents are shown for compounds with m/z values corresponding to those of the three forms of spiramycin, the two forms of platenolide, and the glycosylated intermediates of spiramycin biosynthesis. Strains are as follows: OSC2 (A), SPM121 (Δsrm5::att3) (B), SPM108 (Δsrm29::att3) (C), strain SPM110 (Δsrm38::att3) (D). Peak 1, spiramycin I; peak 2, spiramycin II; peak 3, spiramycin III; peak 4, platenolide II; peak 5, platenolide I; peak 6, forocidin; and peak 7, neospiramycin. Intensity is expressed in arbitrary units.

In the supernatant of the wild-type strain, the three forms of spiramycin were detected, together with small amounts of the two forms of the aglycone and platenolide I and II, which differ by the group at C-9 (a keto group for platenolide I and a hydroxyl group for platenolide II). No other biosynthetic intermediates were detected. In the supernatant of the SPM121 (Δsrm5::att3) mutant strain, the two forms of platenolide were found, but no glycosylated intermediates were detected. This is consistent with the involvement of Srm5 in the attachment of the first sugar added, mycaminose. Forocidin was the only glycosylated intermediate detected in the supernatant of the SPM108 (Δsrm29::att3) mutant strain, in addition to the two forms of platenolide. This indicated that, in this mutant strain, mycaminose could be attached to platenolide, but further glycosylation was not possible, consistent with the involvement of Srm29 in forosamine attachment. The two forms of platenolide and forocidin and neospiramycin could be detected in the supernatant of the SPM110 (Δsrm38::att3) mutant strain. This indicated that Srm38 is involved in the attachment of mycarose.

Involvement of the auxiliary proteins in glycosylation.

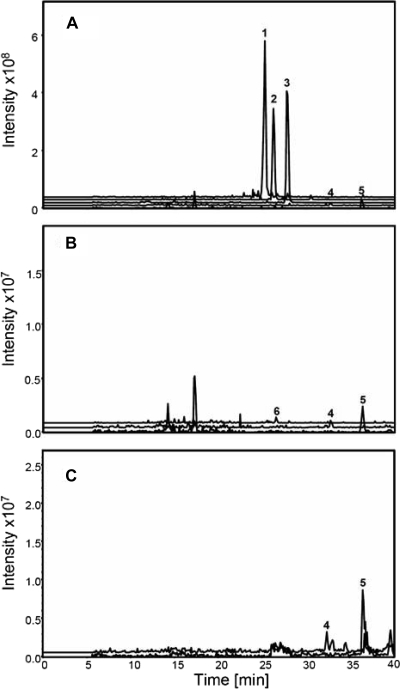

The srm6 gene, encoding a putative auxiliary protein, is located immediately upstream of the gene encoding the Srm5 mycaminosyltransferase. The other gene encoding a putative auxiliary protein, srm28, is located upstream of the gene encoding the Srm29 forosaminyltransferase. According to previous studies of auxiliary proteins, Srm6 might be required for the full activity of Srm5, and Srm28 might be required for the full activity of Srm29. To study the role of the putative glycosyltransferase auxiliary proteins in spiramycin biosynthesis, the ability of the corresponding mutant strains to synthesize spiramycin was examined. To take into account a possible interplay of the auxiliary proteins, a mutant with a deletion of both srm6 and srm28 was constructed and also studied. Culture supernatants were studied by bioassays, HPLC, and LC-MS, and relevant results are presented in Fig. 3 and summarized in Table 4.

FIG. 3.

LC-MS analysis of the metabolites produced by S. ambofaciens mutant strains. Extracted ion currents are shown for compounds with m/z values corresponding to those of the three forms of spiramycin, the two forms of platenolide, and the glycosylated intermediates of spiramycin biosynthesis. Strains are as follows: SPM213 (Δsrm6::att2) (A), SPM212 (Δsrm28::att2) (B), and SPM215 (Δsrm6::att2 Δsrm28::att2) (C). Peak 1, spiramycin I; peak 2, spiramycin II; peak 3, spiramycin III; peak 4, platenolide II; peak 5, platenolide I; and peak 6, forocidin. Intensity is expressed in arbitrary units.

TABLE 4.

Glycosylated compounds synthesized by S. ambofaciens strains

| Straina | Description | Glycosylated compound detected |

Amt of spiramycin (μM/g of DCW ± SD)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forocidin | Neospiramycin | Spiramycin | |||

| OSC2 | Wild type | − | − | + | 71.5 ± 3.5 |

| SPM213 | Δsrm6::att2 in OSC2 | − | − | + | 181.5 ± 5.8 |

| SPM212 | Δsrm28::att2 in OSC2 | + | − | − | 0 |

| SPM215 | Δsrm28::att2 Δsrm6::att2 in OSC2 | − | − | − | 0 |

| SPM212(pSPM224) | SPM212 complemented by srm28 | − | − | + | 178.5 ± 3.1 |

| SPM215(pSPM222) | SPM215 complemented by srm6 | + | − | − | 0 |

| SPM215(pSPM224) | SPM215 complemented by srm28 | − | − | + | 194.9 ± 3.1 |

| SPM217 | Δsrm29::att3 Δsrm6::att2 in OSC2 | + | − | − | 0 |

The name of the plasmid harbored by a strain is given in parentheses.

For strains synthesizing spiramycin, the total amount of the three forms of spiramycin is given. DCW, dry cell weight.

The inactivation of srm6 did not suppress spiramycin production; the three forms of spiramycin (together with small amounts of the two forms of platenolide) were present in the culture supernatant of the mutant strain SPM213 (Δsrm6::att2) (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the deletion of srm6 was accompanied by an increase in spiramycin production (Table 4). The reason for this increase is unknown, but the same phenomenon was observed for three independent srm6 inactivation mutant strains. In contrast, the inactivation of srm28 abolished spiramycin production in the SPM212 (Δsrm28::att2) strain. This effect was due to the inactivation of srm28 because the introduction of the srm28 gene, expressed under the control of the constitutive ermE*p promoter and carried by an integrative vector, into the SPM212 strain restored spiramycin biosynthesis (Table 4). When the SPM212 culture supernatant was analyzed by LC-MS, small amounts of forocidin could be detected, together with the two forms of platenolide (Fig. 3B). No other glycosylated intermediates were detected, indicating that glycosylation was blocked after the addition of mycaminose, and forosamine could not be attached. This is in agreement with the requirement of the auxiliary protein Srm28 for the activity of the forosaminyltransferase Srm29. The amount of forocidin present in culture supernatants of strain SPM212 was sufficient for detection by LC-MS but not for reliable quantification. This low level of intermediate accumulation is reminiscent of the observation that in Streptomyces fradiae inactivation of some glycosyltransferase or deoxyhexose biosynthetic genes involved in tylosin biosynthesis did not lead to the accumulation of the macrolactone (tylactone) under conditions that normally favor tylosin production (4, 7). The complementation experiment, in which high levels of spiramycin production are obtained, demonstrates that the mutant strain SPM212 is not impaired in other spiramycin biosynthetic genes.

As expected from the phenotype of the srm28 deletion mutant, the SPM215 (Δsrm6::att2 Δsrm28::att2) mutant strain did not produce any spiramycin. However, when the SPM215 culture supernatant was analyzed by LC-MS, the two forms of platenolide were the only intermediates detected (Fig. 3C). No glycosylated intermediates were detected, indicating that this strain was impaired not only in forosamine attachment, as expected, but also in mycaminose attachment. This indicated that Srm6, although dispensable, nevertheless plays a role in glycosylation and that Srm5 also requires an auxiliary protein for its activity.

Interplay of the auxiliary proteins.

No glycosylated spiramycin biosynthetic intermediates were observed in the culture supernatants of the SPM215 strain, which is devoid of both auxiliary proteins. To further investigate the possible role of Srm6 in glycosylation and the possible interplay of the auxiliary proteins, each of the genes srm6 or srm28, expressed under the control of the constitutive ermE*p promoter and carried by an integrative vector, was introduced into SPM215.

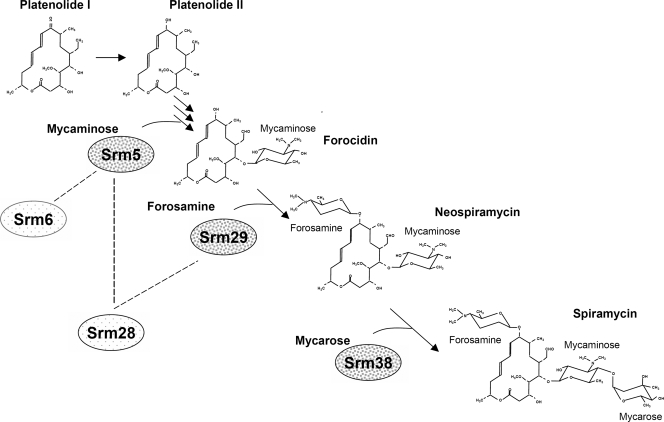

When srm6 was introduced into this mutant, yielding the strain SPM215(pSPM222), forocidin was detected (Table 4). This demonstrated that Srm6 can interact with the Srm5 glycosyltransferase and promote the transfer of mycaminose. The fact that spiramycin biosynthesis is blocked after forocidin formation demonstrated that there was no productive interaction between Srm6 and Srm29. When srm28 was introduced into SPM215, yielding SPM215(pSPM224), it restored spiramycin production. As both Srm5 and Srm29 require an auxiliary protein, this showed that Srm28 was able to interact efficiently with both glycosyltransferases. The interaction of Srm28 with the Srm5 mycaminosyltransferase was confirmed by the study of the SPM217 (Δsrm6::att2 Δsrm29::att3) mutant strain. In this strain, the Srm28 auxiliary protein could not activate the Srm29 forosaminyltransferase, whose gene was deleted. The Srm6 auxiliary protein, whose gene was deleted, could not activate the Srm5 mycaminosyltransferase. However, this strain could produce forocidin (Table 4), confirming that Srm28 activates Srm5. Figure 4 summarizes the results obtained concerning the enzymes involved in the glycosylation of spiramycin.

FIG. 4.

Schematic representation of the glycosylation steps during spiramycin biosynthesis. The intermediates (platenolide I, forocidin, and neospiramycin) are presented together with the glycosyltransferase associated with each glycosylation step. The interactions of the glycosyltransferases with the two auxiliary proteins are also represented by dotted lines. The two forms of platenolides (platenolide I and II) are also presented.

DISCUSSION

The work reported here shows that, among the four putative glycosyltransferases encoded within the spiramycin biosynthetic gene cluster, only three are involved in spiramycin biosynthesis. Each of these three glycosyltransferases is required for the attachment of a specific sugar: Srm5 is the mycaminosyltransferase, Srm29 is the forosaminyltransferase, and Srm38 is the mycarosyltransferase. The role of Srm30, the fourth putative glycosyltransferase, remains unknown. However, it is known that the srm30 gene is transcribed at the same time as the other biosynthetic genes. A role for Srm30 in the inactivation of macrolides was hypothesized. Inactivation of macrolides by glycosylation has been observed in S. ambofaciens extracts, and two glycosyltransferase activities could be distinguished by their macrolide substrate profiles (9). The GimA glycosyltransferase is responsible for one of these activities. Interestingly, the gene encoding this glycosyltransferase has been identified, and it is not located within the spiramycin biosynthetic cluster. However, the gene responsible for the second activity, called GimB, has not yet been identified. One possibility could be that the Srm30 glycosyltransferase is responsible for this activity, a situation that would be similar to that in S. antibioticus, the producer of the macrolide oleandomycin (32). In S. antibioticus two glycosyltransferases, OleI and OleD, can inactivate macrolides by glycosylation and differ in their pattern of substrate specificity. The oleI gene is located in the oleandomycin biosynthetic gene cluster, while oleD is located elsewhere in the genome. However, all of our attempts to demonstrate that Srm30 has a macrolide-inactivating activity were unsuccessful (data not shown). Moreover, we constructed an S. ambofaciens mutant strain in which gimA and srm30 were both deleted. Extracts from this strain retained a macrolide-inactivating activity (data not shown). While this does not absolutely rule out the possible involvement of Srm30 in macrolide inactivation, it minimally shows that Srm30 is not the only gene responsible for the so-called GimB activity.

The involvement of the two glycosyltransferase auxiliary proteins in spiramycin biosynthesis was also elucidated. Our results showed that both of them are involved in glycosylation. The two glycosyltransferases Srm5 and Srm29 require the assistance of an auxiliary protein to perform the attachment of mycaminose and forosamine, respectively. The genes encoding these glycosyltransferases are both immediately downstream of the genes encoding the auxiliary proteins. Each glycosyltransferase can be activated by the auxiliary protein encoded by the upstream gene: Srm5 by Srm6 and Srm29 by Srm28. In addition, we have demonstrated the existence of an interplay between the auxiliary proteins (i.e., Srm28 can also efficiently activate Srm5). This explains why srm6 is dispensable for spiramycin biosynthesis. In contrast, we did not observe any activation of Srm29 by Srm6. Because of the observed flexibility of auxiliary proteins, we cannot exclude that Srm38, the mycarosyltransferase, might require the assistance of an auxiliary protein, but this cannot be studied in vivo in S. ambofaciens.

As Srm28 possesses certain flexibility, it would be interesting to determine if it can efficiently activate other glycosyltransferases requiring the assistance of auxiliary proteins. It was shown that different auxiliary proteins could activate the DesVII glycosyltransferase, but the efficiency of the activation ranged between 26 and 66% compared to that of the natural partner DesVIII (14). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the interplay of auxiliary proteins involved in different glycosylation steps during the synthesis of a single compound, but the auxiliary proteins studied thus far have been involved in pathways where only one glycosyltransferase required the assistance of an auxiliary protein. Other macrolide biosynthetic pathways may also involve two auxiliary proteins with two glycosyltransferases that require them. One such example might be the megalomicin biosynthetic pathway. Megalomicin, which is produced by Micromonospora megalomicea, is structurally very similar to erythromycin but differs by the addition of the deoxyamino sugar megosamine, attached at the C-6 of the macrolactone. In the megalomicin biosynthetic cluster, there are two genes located immediately upstream of the mycaminosyltransferase and megosaminyltransferase genes, which are predicted to code for auxiliary proteins though they were originally annotated as nucleoside diphosphate (NDP)-sugar epimerases (14, 41). It would be interesting to investigate the role and eventual interplay of the putative auxiliary proteins in this pathway.

Most of the known or putative auxiliary proteins activate glycosyltransferases that attach amino sugars, and this is also the case in the spiramycin pathway. However, a role as an amino sugar carrier for the auxiliary proteins does not seem probable, as DesVIII equally activates DesVII activity for the attachment of both amino sugars and nonamino sugars (2). In this respect, it should be noted that while the Srm29 forosaminyltransferase requires the Srm28 auxiliary protein, there is no evidence for such a requirement for the activity of the SpnP forosaminyltransferase involved in spinosyn biosynthesis, and no putative auxiliary protein is encoded in the spinosyn biosynthetic gene cluster (15, 42).

The mechanism by which auxiliary proteins activate glycosyltransferases remains unclear (2, 3, 24, 44). Auxiliary proteins are most probably not involved in the transfer reaction itself but might act by inducing a conformational change in the glycosyltransferase. Further studies of Srm28, which can efficiently activate two different glycosyltransferases for the attachment of two different sugars, may help to better elucidate the role of these intriguing proteins.

Acknowledgments

H.C.N. received fellowships from the Vietnamese Ministry of Education and from the Université Paris-Sud 11. F.K. was supported by a CNRS-BDI fellowship. This work was supported in part by the European Union through the Integrated Project ActinoGEN (CT-2004-0005224) and by Pôle de Recherche et d'Enseignement Supérieur UniverSud Paris.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blondelet-Rouault, M. H., J. Weiser, A. Lebrihi, P. Branny, and J. L. Pernodet. 1997. Antibiotic resistance gene cassettes derived from the omega interposon for use in E. coli and Streptomyces. Gene 190:315-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borisova, S. A., C. Zhang, H. Takahashi, H. Zhang, A. W. Wong, J. S. Thorson, and H. W. Liu. 2006. Substrate specificity of the macrolide-glycosylating enzyme pair DesVII/DesVIII: opportunities, limitations, and mechanistic hypotheses. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 45:2748-2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borisova, S. A., L. Zhao, I. C. Melancon, C. L. Kao, and H. W. Liu. 2004. Characterization of the glycosyltransferase activity of desVII: analysis of and implications for the biosynthesis of macrolide antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:6534-6535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler, A. R., S. A. Flint, and E. Cundliffe. 2001. Feedback control of polyketide metabolism during tylosin production. Microbiology 147:795-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaveroche, M. K., J. M. Ghigo, and C. d'Enfert. 2000. A rapid method for efficient gene replacement in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:E97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doumith, M., P. Weingarten, U. F. Wehmeier, K. Salah-Bey, B. Benhamou, C. Capdevila, J. M. Michel, W. Piepersberg, and M. C. Raynal. 2000. Analysis of genes involved in 6-deoxyhexose biosynthesis and transfer in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Mol. Gen. Genet. 264:477-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fish, S. A., and E. Cundliffe. 1997. Stimulation of polyketide metabolism in Streptomyces fradiae by tylosin and its glycosylated precursors. Microbiology 143:3871-3876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geistlich, M., R. Losick, J. R. Turner, and R. N. Rao. 1992. Characterization of a novel regulatory gene governing the expression of a polyketide synthase gene in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2019-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gourmelen, A., M. H. Blondelet-Rouault, and J. L. Pernodet. 1998. Characterization of a glycosyl transferase inactivating macrolides, encoded by gimA from Streptomyces ambofaciens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2612-2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gust, B., G. L. Challis, K. Fowler, T. Kieser, and K. F. Chater. 2003. PCR-targeted Streptomyces gene replacement identifies a protein domain needed for biosynthesis of the sesquiterpene soil odor geosmin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:1541-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen, J. L., J. A. Ippolito, N. Ban, P. Nissen, P. B. Moore, and T. A. Steitz. 2002. The structures of four macrolide antibiotics bound to the large ribosomal subunit. Mol. Cell 10:117-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong, J. S. 2005. The role of a second protein (DesVIII) in glycosylation for the biosynthesis of hybrid macrolide antibiotics in Streptomyces venezuelae. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 15:640-645. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong, J. S., S. H. Park, C. Y. Choi, J. K. Sohng, and Y. J. Yoon. 2004. New olivosyl derivatives of methymycin/pikromycin from an engineered strain of Streptomyces venezuelae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238:391-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong, J. S., S. J. Park, N. Parajuli, S. R. Park, H. S. Koh, W. S. Jung, C. Y. Choi, and Y. J. Yoon. 2007. Functional analysis of desVIII homologues involved in glycosylation of macrolide antibiotics by interspecies complementation. Gene 386:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong, L., Z. Zhao, C. E. Melancon III, H. Zhang, and H. W. Liu. 2008. In vitro characterization of the enzymes involved in TDP-d-forosamine biosynthesis in the spinosyn pathway of Saccharopolyspora spinosa. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130:4954-4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamra, P., R. S. Gokhale, and D. Mohanty. 2005. SEARCHGTr: a program for analysis of glycosyltransferases involved in glycosylation of secondary metabolites. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W220-W225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karray, F. 2005. Etude de la biosynthèse de l'antibiotique spiramycine par Streptomyces ambofaciens. Ph.D. thesis. Université de Paris-Sud 11, Orsay, France.

- 18.Karray, F., E. Darbon, N. Oestreicher, H. Dominguez, K. Tuphile, J. Gagnat, M. H. Blondelet-Rouault, C. Gerbaud, and J. L. Pernodet. 2007. Organization of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the macrolide antibiotic spiramycin in Streptomyces ambofaciens. Microbiology 153:4111-4122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz, L., and G. W. Ashley. 2005. Translation and protein synthesis: macrolides. Chem. Rev. 105:499-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 21.Kuhstoss, S., M. Huber, J. R. Turner, J. W. Paschal, and R. N. Rao. 1996. Production of a novel polyketide through the construction of a hybrid polyketide synthase. Gene 183:231-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu, M., and S. Douthwaite. 2002. Resistance to the macrolide antibiotic tylosin is conferred by single methylations at 23S rRNA nucleotides G748 and A2058 acting in synergy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:14658-14663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lombo, F., C. Olano, J. A. Salas, and C. Mendez. 2009. Chapter 11. Sugar biosynthesis and modification. Methods Enzymol. 458:277-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, W., C. Leimkuhler, G. J. Gatto, Jr., R. G. Kruger, M. Oberthur, D. Kahne, and C. T. Walsh. 2005. AknT is an activating protein for the glycosyltransferase AknS in l-aminodeoxysugar transfer to the aglycone of aclacinomycin A. Chem. Biol. 12:527-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Melancon, C. E., III, H. Takahashi, and H. W. Liu. 2004. Characterization of tylM3/tylM2 and mydC/mycB pairs required for efficient glycosyltransfer in macrolide antibiotic biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:16726-16727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendez, C., and J. A. Salas. 2001. Altering the glycosylation pattern of bioactive compounds. Trends Biotechnol. 19:449-456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Omura, S., H. Sano, and T. Sunazuka. 1985. Structure activity relationships of spiramycins. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 16(Suppl. A):1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pernodet, J. L., M. T. Alegre, M. H. Blondelet-Rouault, and M. Guerineau. 1993. Resistance to spiramycin in Streptomyces ambofaciens, the producer organism, involves at least two different mechanisms. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139:1003-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pernodet, J. L., S. Fish, M. H. Blondelet-Rouault, and E. Cundliffe. 1996. The macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance phenotypes characterized by using a specifically deleted, antibiotic-sensitive strain of Streptomyces lividans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:581-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prentki, P., and H. M. Krisch. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quiros, L. M., I. Aguirrezabalaga, C. Olano, C. Mendez, and J. A. Salas. 1998. Two glycosyltransferases and a glycosidase are involved in oleandomycin modification during its biosynthesis by Streptomyces antibioticus. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1177-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raynal, A., F. Karray, K. Tuphile, E. Darbon-Rongere, and J. L. Pernodet. 2006. Excisable cassettes: new tools for functional analysis of Streptomyces genomes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4839-4844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rix, U., C. Fischer, L. L. Remsing, and J. Rohr. 2002. Modification of post-PKS tailoring steps through combinatorial biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 19:542-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roberts, M. C., J. Sutcliffe, P. Courvalin, L. B. Jensen, J. Rood, and H. Seppala. 1999. Nomenclature for macrolide and macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance determinants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2823-2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salas, J. A., and C. Mendez. 2007. Engineering the glycosylation of natural products in actinomycetes. Trends Microbiol. 15:219-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russel. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 38.Schlunzen, F., R. Zarivach, J. Harms, A. Bashan, A. Tocilj, R. Albrecht, A. Yonath, and F. Franceschi. 2001. Structural basis for the interaction of antibiotics with the peptidyl transferase centre in eubacteria. Nature 413:814-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simon, R., U. Priefer, and A. Puhler. 1983. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1:784-791. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vester, B., and S. Douthwaite. 2001. Macrolide resistance conferred by base substitutions in 23S rRNA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Volchegursky, Y., Z. Hu, L. Katz, and R. McDaniel. 2000. Biosynthesis of the anti-parasitic agent megalomicin: transformation of erythromycin to megalomicin in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Mol. Microbiol. 37:752-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Waldron, C., P. Matsushima, P. R. Rosteck, Jr., M. C. Broughton, J. Turner, K. Madduri, K. P. Crawford, D. J. Merlo, and R. H. Baltz. 2001. Cloning and analysis of the spinosad biosynthetic gene cluster of Saccharopolyspora spinosa. Chem. Biol. 8:487-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, D., H. M. Ellis, E. C. Lee, N. A. Jenkins, N. G. Copeland, and D. L. Court. 2000. An efficient recombination system for chromosome engineering in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:5978-5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan, Y., H. S. Chung, C. Leimkuhler, C. T. Walsh, D. Kahne, and S. Walker. 2005. In vitro reconstitution of EryCIII activity for the preparation of unnatural macrolides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:14128-14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]