Abstract

The reduced in vivo sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum has recently been confirmed in western Cambodia. Identifying molecular markers for artemisinin resistance is essential for monitoring the spread of the resistant phenotype and identifying the mechanisms of resistance. Four candidate genes, including the P. falciparum mdr1 (pfmdr1) gene, the P. falciparum ATPase6 (pfATPase6) gene, the 6-kb mitochondrial genome, and ubp-1, encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme, of artemisinin-resistant P. falciparum strains from western Cambodia were examined and compared to those of sensitive strains from northwestern Thailand, where the artemisinins are still very effective. The artemisinin-resistant phenotype did not correlate with pfmdr1 amplification or mutations (full-length sequencing), mutations in pfATPase6 (full-length sequencing) or the 6-kb mitochondrial genome (full-length sequencing), or ubp-1 mutations at positions 739 and 770. The P. falciparum CRT K76T mutation was present in all isolates from both study sites. The pfmdr1 copy numbers in western Cambodia were significantly lower in parasite samples obtained in 2007 than in those obtained in 2005, coinciding with a local change in drug policy replacing artesunate-mefloquine with dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine. Artemisinin resistance in western Cambodia is not linked to candidate genes, as was suggested by earlier studies.

Antimalarial drug resistance is the single most important threat to global malaria control. Over the past 40 years, as first-line treatments (chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine) failed, the malaria-attributable mortality rate rose, contributing to a resurgence of malaria in tropical countries (11). In the last decade, artemisinins, deployed as artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs), have become the cornerstone of the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria (20) and, in conjunction with other control measures, have contributed to a remarkable decrease in malaria morbidity and mortality in many African and Asian countries (4). The recent confirmation of the reduced artemisinin sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum parasites in western Cambodia has therefore alarmed the malaria community (6). A large containment effort has been launched by the World Health Organization, in collaboration with the national malaria control programs of Cambodia and neighboring Thailand. The resistant phenotype has not been well characterized and is not well reflected by the results of conventional in vitro drug susceptibility assays. No molecular marker has been identified, which impedes surveillance studies to monitor the spread of the resistant phenotype. Identification of molecular markers would give insight into the mechanisms underlying artemisinin resistance and the mechanism of antimalarial action of the artemisinins.

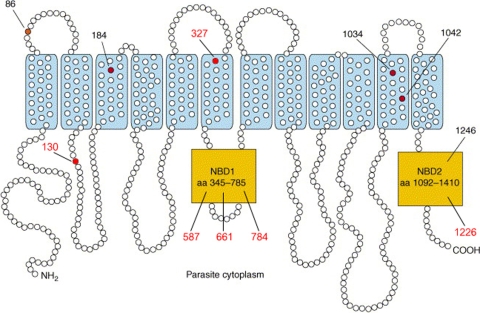

Mutations in several candidate genes have been postulated to confer artemisinin resistance. (i) P. falciparum mdr1 (pfmdr1) encodes the P-glycoprotein homologue 1 (Pgh1), which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily, members of which couple ATP hydrolysis to the translocation of a diverse range of drugs and other solutes across the food vacuole and plasma membranes of the parasite (Fig. 1) (5). The gene is located on chromosome 7, is 4.2 kb in length, and contains only one exon. Mutations in and, more importantly, amplification of the wild-type gene confer resistance to the 4-methanolquinoline mefloquine, presumably through an increased ability to efflux the drug (15, 16). Mutations and amplification of the gene have also been associated with reduced in vitro susceptibility to the artemisinins (7, 16). In vivo selection of the pfmdr1 86N allele after artemether-lumefantrine treatment has been observed in Africa (17).

FIG. 1.

Predicted structure and representative haplotypes of P. falciparum multidrug resistance transporter. PfMDR1 is predicted to have 12 transmembrane domains, with its N and C termini located on the cytoplasmic side of the digestive vacuole membrane (adapted from reference 19). Mutations identified in pfmdr1 full-length sequences from Pailin and WangPha are indicated by the red circles. aa, amino acid.

(ii) P. falciparum ATPase6 (pfATPase6) encodes the calcium-dependent sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase, which was shown to be a target for the artemisinin drugs in Xenopus oocytes (8). The gene is 4.3 kb in length and has three exons on chromosome 1. A single amino acid change in pfATPase6, L263E, is associated with resistance to artemisinins in this model (8, 18). Mutation S769N in pfATPase6 in P. falciparum isolates from French Guiana was associated with decreased in vitro sensitivity to artemether (10). However, it is unclear whether mutations in pfATPase6 are associated with artemisinin resistance in vivo (1).

(iii) The electron transport chain in the mitochondrial inner membrane is key to the malaria parasite's capacity to produce ATP. Since activation of the endoperoxide bridge in the artemisinins by an electron donor is central to their antimalarial activity, mitochondrial proteins are potential activation sites for the artemisinins. Mutations in the mitochondrial genome, which is 6 kb long and which contains three genes (cytochrome b, COXI, COXIII), could therefore potentially change susceptibility to the artemisinins.

(iv) ubp-1, a 3.3-kb gene located on chromosome 2, encodes a deubiquitinating enzyme. Mutations V739F and V770F in ubp-1 of P. chabaudi were recently identified by linkage group analysis of an elegant genetic-cross experiment to confer resistance to artesunate in this rodent malaria parasite (9).

(v) Laboratory-induced artemisinin resistance in the P. chabaudi model has been demonstrated in a chloroquine-resistant strain. This suggests that chloroquine resistance in this model might be a prerequisite for the subsequent development of artemisinin resistance. We therefore also assessed the parasite genome for the presence of the P. falciparum CRT (pfCRT) K76T mutation, which plays a central role in the chloroquine resistance of P. falciparum.

We report here the molecular characteristics of these five groups of genes in P. falciparum isolates from western Cambodia, where most infections show reduced sensitivity to artesunate, compared to those of strains obtained from northwestern Thailand, where infections are artemisinin sensitive (6).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Parasite DNA was collected from patients with falciparum malaria enrolled in clinical studies on artemisinin resistance conducted in Pailin, western Cambodia, and WangPha, northwestern Thailand, in 2007 and 2008 and from studies in Trat Province (eastern Thailand) and MaeSot (northwestern Thailand) in 2006. The clinical trials were registered under ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00493363 and Current Controlled Trials numbers ISRCTN64835265 and ISRCTN15351875. The results of these studies showed a relatively uniform in vivo resistance of P. falciparum in the patients studied in western Cambodia in 2007, characterized by an almost doubling of the parasite clearance times compared to those for the patients studied in northwestern Thailand, who had similar plasma concentration profiles for artesunate and dihydroartemisinin (6).

Parasite DNA was extracted from either filter paper (Whatman 3MM) or whole blood using a Qiagen kit (Hilden, Germany).

Quantitation of pfmdr1 copy number by TaqMan real-time PCR.

The pfmdr1 copy number was assessed by TaqMan real-time PCR on a Corbett Rotor-Gene 3000 apparatus (Corbett Research, Australia). The primers and probes have been described previously (15). A Quantitec multiplex PCR without 6-carboxyl-X-rhodamine (Qiagen) was used, and the temperature profile used was according to the manufacturer's instructions. Amplification was carried out as a multiplex PCR in a total volume of 10 μl. The samples were set up in triplicate. Every amplification run contained nine replicates of the 3D7 control and triplicates without template as negative controls. The β-tubulin gene served as an internal control for the amount of sample DNA added to the reaction mixtures. Normalized relative amounts of the target gene were calculated by using 3D7 as a calibrator. The relative amounts of the target genes were calculated by using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method. Copy numbers were calculated using the formula 2−ΔΔCT, with ΔΔCT being the difference between the ΔCT of the unknown sample and the ΔCT of the reference sample.

Assessment of full lengths of pfserca, pfmdr1, and mtDNA.

Pairs of primers were designed to span 4,068 bp of the P. falciparum serca (pfserca) gene (9 pairs), 4,260 bp of pfmdr1 (10 pairs), and 6 kb of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA; 14 pairs; Table 1 ) using the primer 3 program (http://primer3.sourceforge.net/). Each pair of primers was designed to overlap at least 100 bp in order to cover all sequencing results. Different pairs of primers were optimized regarding the reaction conditions and the temperature profile. Single PCR amplifications were performed in a 100-μl total sample volume. The DNA sequences were assessed by direct sequencing of the PCR product (Macrogen, South Korea) and were analyzed with the Bioedit bioinformatics program.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of primers used for full-length sequencing and PCR conditions

| Sequence GenBank accession no. and gene | Region (bases) | Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Size (bp) | Tma (°C) | Product size (bp) | MgCl2 concn (mM) | Annealing temp (°C) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB121056 (T9/96) | |||||||||

| pfATPase6 | 6-742 | Pfserca_S1F | CTTATTATATCTTTGTCATTCGTG | 24 | 46 | 737 | 3 | 52 | |

| Pfserca_S1R | CCACATACAATAGCGGTAGATG | 22 | 49 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 555-1367 | Pfserca_S2F | AATAAAACTCCCGCTGATGC | 20 | 58 | 813 | 2 | 58 | |

| Pfserca_S2R | TTCTCCATCATCCGTTAAAGC | 21 | 60 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 994-1837 | Pfserca_S3F | TTGCTTTAGCTGTTGCTGCT | 20 | 58 | 844 | 1.5 | 58 | |

| Pfserca_S3R | TTGTTGATACCCCTTGGTGA | 20 | 58 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 1327-2026 | Pfserca_S4F | AAGATGAAGGAAATGTTGAAGC | 22 | 50 | 700 | 3 | 55 | |

| Pfserca_S4R | CCCAATTTTGAGTGGAAACAA | 21 | 60 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 1940-2489 | Pfserca_S5NF | GGCAACAACAAATGGATATGA | 21 | 50 | 550 | 2 | 55 | |

| Pfserca_S5R | TCCTTTTCATCATCTCCTTCA | 21 | 49 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 2341-3216 | Pfserca_S6F | GAGCATTAAGAACACTTAGCTTTGC | 25 | 53 | 876 | 1 | 58 | |

| Pfserca_S6R | CTGTTGCTGGTAATCCGTCA | 20 | 60 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 2721-3457 | Pfserca_S7F | CCAAGAATTGTTTTCTGTAGAACTGA | 26 | 53 | 737 | 3 | 58 | |

| Pfserca_S7R | CGTGTGCATATCTGAATCTGG | 21 | 62 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 3106-3805 | Pfserca_S8F | CTGACGGATTACCAGCAACA | 20 | 60 | 700 | 1 | 60 | Difficult sequencing |

| Pfserca_S8R | CACTCAAGGCATTCAAAGCA | 20 | 58 | ||||||

| pfATPase6 | 3526-4068 | Pfserca_S9NF | CCAGATTCAGATATGCACACG | 24 | 51 | 543 | 1 | 52 | Difficult sequencing |

| Pfserca_S9R | ATCAATTTTAATTTTCTTGGTTC | 23 | 56 | ||||||

| M76611 | |||||||||

| PfmtDNAa | 1-546 | Pfmt 1-546_F | AAGCTTTTGGTATCTCGTAATG | 22 | 56 | 546 | 2 | 55 | |

| Pfmt 1-546_R | CAGCTATCCATAGTTAATTGATTCC | 25 | 58 | ||||||

| PfmtDNA | 429-959 | Pfmt 429-959_F | ATGTGTTCCACCGCTAGTGT | 20 | 59 | 531 | 2 | 55 | COXIII |

| Pfmt 429-959_R | TTGTGTTACAGGATTACATTTTTCTC | 26 | 58 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 799-1340 | Pfmt 799-1340_F | TTGTAATTTGATCAGTGTGAGG | 22 | 56 | 542 | 3 | 55 | COXIII |

| Pfmt 799-1340_R | TTCTATTCGAGAAAGTTTTTATTCTG | 26 | 57 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 1208-1750 | Pfmt 1208-1750_F | TGGATATGGTGATAAACTAAAATG | 24 | 56 | 543 | 2 | 55 | COXIII |

| Pfmt 1208-1750_R | ATTACCTTTCCGGCTGTTTC | 20 | 59 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 1654-2201 | Pfmt 1654-2201_F | CTTGTACACACCGCTCGTC | 19 | 58 | 548 | 2 | 58 | COXI |

| Pfmt 1654-2201_R | TCTTGTGCAATTATTCTTAAAGATG | 25 | 57 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 2103-2626 | Pfmt 2103-2626_F | TTTATGGTTTTCATTTTTATTTGG | 24 | 57 | 524 | 2 | 58 | COXI |

| Pfmt 2103-2626_R | TGATCAATGACCATGTAGAAACA | 23 | 59 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 2482-3025 | Pfmt 2482-3025_F | GCTGTAGATGTAATAATTTTTGGTTT | 26 | 57 | 544 | 1 | 55 | COXI |

| Pfmt 2482-3025_R | TCCAGTTAAATACTTTTGTACCG | 23 | 56 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 2896-3442 | Pfmt 2896-3442_F | GCTGTTTTAGGAAGCTTAGTATGG | 24 | 58 | 547 | 1 | 55 | COXI |

| Pfmt 2896-3442_R | TCATTGTTGACCCAATAGAACA | 22 | 59 | ||||||

| PfmtDNA | 3328-3874 | Pfmt 3328-3874_F | TTAACATTTTTACCTATGCATTTTT | 25 | 56 | 547 | 3 | 55 | COXI and COB |

| Pfmt 3328-3874_R | AAGACATAACCAACGAAAGCA | 21 | 58 | ||||||

| PfmtDNA | 3690-4329 | Pfmt 3690-4329_F | GAATTATGGAGTGGATGGTG | 20 | 58 | 640 | 3 | 55 | COB |

| Pfmt 3690-4329_R | CAGCTGGTTTACTTGGAA | 18 | 52 | ||||||

| PfmtDNA | 4188-4687 | Pfmt 4188-4687_F | AGTTTATTTGGAATTATACCTTTATCA | 27 | 56 | 500 | 3 | 55 | COB |

| Pfmt 4188-4687_R | AACCTTACGGTCTGATTTGTTC | 22 | 58 | ||||||

| PfmtDNA | 4596-5140 | Pfmt 4596-5140_F | GATTACAGCTCCCAAGCAAA | 20 | 58 | 545 | 1 | 55 | |

| Pfmt 4596-5140_R | AGACCGAACCTTGGACTCTT | 20 | 58 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 4965-5573 | Pfmt 4965-5573_F | GTTCGGTATTGCATGCCTG | 19 | 58 | 609 | 1 | 55 | |

| Pfmt 4965-5573_R | CTTATGTGTTGGCATGGTT | 19 | 54 | ||||||

| Pfmt DNA | 5353-5945 | Pfmt 5353-5945_F | GAAATCCGTATATCGATGTC | 20 | 56 | 593 | 1 | 55 | |

| Pfmt 5353-5945_R | GTTGAACATAGGCTGAGTC | 19 | 56 | ||||||

| XM 001351751 | |||||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 1-504 | Pfmdr1_1-504_F | CATTTTATTTGATTTTGTGTTGAAA | 25 | 50 | 504 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_1-504_R | CGTACCAATTCCTGAACTCAC | 21 | 49 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 329-878 | Pfmdr1_329-878_F | TGATATCAAGTTATTGTATGGATGTAA | 27 | 49 | 550 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_329-878_R | CCGAATGCATAAGAAACTAAAA | 22 | 49 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 728-1261 | Pfmdr1_728-1261_F | CTGTTGCAAGTTATTGTGGAGA | 22 | 50 | 534 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_728-1261_R | TTGATTTCCCACAACCTGAT | 20 | 56 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 1155-1684 | Pfmdr1_1155-1684_F | TCATTATGATACTAGAAAAGATGTTGA | 27 | 49 | 530 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_1155-1684_R | TGGATGCATTGGAACCTACT | 20 | 58 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 1589-2131 | Pfmdr1_1589-2131_F | CTGATGTTGTTGATGTGTCCA | 21 | 49 | 543 | 3 | 60 | |

| Pfmdr1_1589-2131_R | CCGATCCATTATCATTTCCA | 20 | 56 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 2013-2539 | Pfmdr1_2013-2539_F | TGAACAAGGTACACATGATAGTCTT | 25 | 49 | 527 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_2013-2539_R | TGTTTCTGAAATGAACATAGCAA | 23 | 50 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 2401-2911 | Pfmdr1_2401-2911_F | GGATTATATCCCGTATTTGCTTT | 23 | 51 | 511 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_2401-2911_R | CAAAAACTCCGCTTGACATA | 20 | 56 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 2780-3279 | Pfmdr1_2780-3279_F | ATTTTTGTCCAATTGTTGCAG | 21 | 50 | 500 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_2780-3279_R | TGATAATTTTGCATTTTCTGAATC | 24 | 50 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 3179-3777 | Pfmdr1_3179-3777_F | TTGATGACTTTATGAAATCCTTATT | 25 | 49 | 599 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_3179-3777_R | CATGGGTTCTTGACTAACTATTGA | 24 | 50 | ||||||

| Pfmdr1 | 3639-4260 | Pfmdr1_3639-4260_F | TCAAACCAATCTGGATCTGC | 20 | 58 | 622 | 3 | 57 | |

| Pfmdr1_3639-4260_R | GCTTCATTTAGCTAATTTTACATATTTTT | 29 | 52 |

PfmtDNA, P. falciparum mtDNA.

Assessment of point mutations in pfcrt and ubp-1.

The pfcrt gene was amplified from the DNA template using nested PCR. A PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay was then used to assess the mutation at position 76 using ApoI (New England Biolabs, United Kingdom), as described previously (7). Digestion fragments were analyzed on a 3% agarose gel. The ubp-1 gene encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme was amplified from the DNA template using nested PCR, as described previously (9). PCR products were sent for DNA sequencing (Macrogen), and the Bioedit software program was used for the analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done with the STATA (version 10) and Epistat programs. Since the current definition of artemisinin resistance is based solely on the parasite clearance rates in patients (6), which also partly depend on host factors, we do not know whether the parasite strains from the small subset of patients in Pailin in western Cambodia with relatively fast clearance rates consist of a separate, distinct sensitive population or merely represent a genetically resistant population at the faster end of a spectrum of resistance development. Therefore, the analysis compares the genetic differences in parasites between the two geographical areas, as well as between parasites obtained from patients with fast versus slow clearance rates. Comparisons between sites were conducted for each genotype using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

To compare the fast and slow responders, the clearance rate was calculated for each patient. This was defined as the slope of the best-fitting line when the log10 parasitemia was plotted against the time since the start of treatment. Using the 90% cutoff reported by Anderson et al. (3), patients with a clearance rate of 0.065 or less were classified as slow responders. Comparisons were made using Fisher's exact test and were adjusted for site.

RESULTS

Candidate genes for artemisinin resistance were compared according to study site and parasite clearance rates (Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

Mutations of pfmdr1, pfATPase6, 6-kb mitochondrial genome, ubp-1, and pfCRT in samples from Pailin and WangPhaa

| Candidate gene | No. of corresponding genotypes (total no. of patients) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pailin (2007) | WangPha | ||

| pfmdr1 (multidrug resistance) | |||

| Single copy no. | 41 (43) | 19 (35) | |

| Multiple copy no. | 2 (43) | 16 (35) | <10−6 |

| E130K mutant | 0 (40) | 6 (27) | 0.003 |

| Y184F mutant | 32 (41) | 2 (37) | <10−8 |

| L327H mutant | 5 (43) | ND | |

| D587E mutant | 1 (40) | 0 (30) | 1.000 |

| S784L mutant | 12 (43) | 0 (20) | 0.006 |

| N1042D mutant | 1 (42) | 0 (39) | 1.000 |

| F1226Y mutant | 0 (43) | 18 (33) | <10−8 |

| pfmdr1 (indels) | |||

| Wild type | 2 (41) | 0 (29) | 0.333 |

| Insertion 1 amino acid + N | 20 (41) | 17 (29) | 0.222 |

| Insertion 3 amino acids + NNN | 6 (41) | 0 (29) | 0.030 |

| Deletion 1 amino acid − N | 0 (41) | 8 (29) | 0.168 |

| Deletion 3 amino acids − NNN | 13 (41) | 4 (29) | 0.460 |

| pfATPase6 (SERCA) | |||

| I89T mutant | 8 (43) | 2 (96)b | 0.118 |

| H243Y mutant | 0 (43) | 1 (38)b | 0.480 |

| L263E mutant | 0 (43) | 1 (96)b | 0.480 |

| A438D mutant | 1 (40) | 2 (56)b | 0.490 |

| N464 deletion | 1 (43) | 0 (56)b | 0.510 |

| N465S mutant | 5 (42) | 1 (56)b | 0.118 |

| N465deletion | 1 (43) | 0 (56)b | 0.518 |

| E847K mutant | 2 (39) | 0 (86)b | 0.253 |

| PfDUB (deubiquitinating enzyme) | |||

| V739F wild type | 17 (17) | 20 (20) | 0.999 |

| V770F wild type | 17 (17) | 20 (20) | 0.999 |

| pfcrt (chloroquine resistance transporter), K76T mutant | 43 (43) | 37 (37) | 0.999 |

| P. falciparum mtDNA (mtDNA genome) | |||

| I239V mutant (COXIII) | 19 (38) | 23 (49)b | 0.473 |

| A312V mutant (cytochrome b) | 0 (42) | 1 (45)b | 0.523 |

Mutation frequencies were determined by full-length sequencing and copy number polymorphism forpfmdr1, full-length sequencing forpfATPase6, and full-length sequencing for the 6-kb mitochondrial genome and by the detection of specific mutations forubp-1 (which encodes a deubiquitinating enzyme) and pfCRT.

The results were obtained for P. falciparum parasites collected in 2006 in MaeSot, Thailand. No mutations were found at position N86Y, S1034C, or D1246Y in the pfmdr1 gene.

pfmdr1 copy number and mutations.

Parasite DNA obtained from patients in Pailin (2005 and 2007), WangPha, and Trat was assessed for pfmdr1 copy number variations using real-time PCR. pfmdr1 amplification was found in 50% of all samples from WangPha (Thailand), and the median copy number was 1.47 (range, 0.75 to 3.35 copies). Multiple copies were present in 45.9% of the samples from Trat Province in eastern Thailand, close to Cambodia (median = 2.28; range = 0.87 to 3.53), and in 33% of samples from Pailin collected in 2005 (median = 1.23; range = 0.85 to 2.65). In contrast, parasite DNA from patients in Pailin in 2007 showed multiple pfmdr1 copies in only 2 of 43 primary infections (5%), with both having a copy number of 2 (P < 10−6; Table 2).

Full-length sequencing of pfmdr1 was performed for samples from Pailin and WangPha collected in 2007. Mutations at positions N86Y, S1034C, and D1246Y were not detected in any of the samples; but mutant codon Y184F was present in 32 (78%) of the parasites from Pailin and in 2 (5%) from WangPha (P <10−8). Six novel nonsynonymous mutations at E130K, L327H, D587E, S784L, and F1226Y, one synonymous mutation at a747g, and an indel at position 661N were found (Fig. 1). The mutations at L327H, D587E, S784L, and N1042D were observed only at a low frequency in Pailin. The other two mutations, E130K and F1226Y, were found only in WangPha (P < 10−8). The indel of N at position 661N (using 3D7 [GenBank accession number XM_001351751] as a reference) was found in both areas (Table 2).

Sequencing of full-length pfserca.

Sequencing of the full length of the pfserca gene, spanning 4,049 bp with 3 exons and 2 introns, revealed only sporadic point mutations compared to the wild-type sequence. Mutations at codons L263E and S769N, which have been proposed to confer artemisinin resistance, were not detected. Mutations occurred only sporadically in both areas and were situated at positions I89T, H243Y, A438D, t2951a, N465S, and E847K, as shown in Table 2. Indels of TA located in intron nucleotides 3621 to 3671 (T9/96 [GenBank accession number AB121056] was used as a reference) were observed at both sites, had repeats that varied from 10 to 19, and were similar in length in both areas.

Mutations in pfcrt and ubp-1.

The K76T mutation in the pfcrt gene was present in all parasites from both Pailin and WangPha. The ubp-1 gene encoding a deubiquinating enzyme was assessed for the V739F and V770F mutations, which are the equivalent of the mutations conferring artemisinin resistance in the rodent model of malaria (9), but no mutations were detected.

Sequencing of full-length mtDNA.

The whole mitochondrial genome of 6 kb in length was assessed using directed PCR sequencing with 14 overlapping paired primers. In the coding region, only one nonsynonymous mutation was observed in a coding region, which was the I239V mutation in the COXIII gene, present in 50% (19/38) of the parasites (Table 2). The frequency of this mutation did not differ between study sites. Four mutations were found in intergenic regions, which were located at nucleotides a74t, c204t, t1776c, and t2686c, all with relatively low frequencies.

Comparison according to parasite clearance rates.

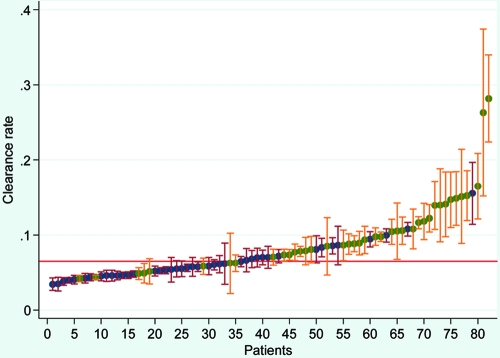

There were 28/42 patients (66.7%) in western Cambodia and 8/40 (20%) in northwestern Thailand with a slow parasite clearance rate (Fig. 2), defined as a slope of the log parasite-time curve of less than 0.065 (3). Differences in the frequencies of mutations between the fast and slow responders were observed only for pfmdr1 F1226Y (P = 0.03) and Y184F (P = 0.001). For F1226Y, there was a lower frequency of mutations in the slow responders (4/35 versus 14/40 for the fast responders), while for Y184F, there was a higher frequency of mutations among slow responders (22/33 versus 12/44 for the fast responders). The association for Y184F did not persist when the results were adjusted for site (P = 0.54). The results for F1226Y were not adjusted for site, as there were no mutations in any of the Pailin samples (Table 2). The frequencies of none of the other genes showed significant differences between sites.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of clearance rates in patients from Pailin (blue dots) and Maesot (green dots). Clearance rates of less than 0.065 (red line) were considered low. Bars, 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated genes which have been proposed to be potential contributors to artemisinin resistance: pfmdr1, pfserca, pfcrt, ubp-1, and mtDNA. The only mutation that was more frequent in parasites with slow parasite clearance rates was Y184F in pfmdr1. However, if the analysis was adjusted for both study site and clearance rate, the association was no longer significant, suggesting that it is unlikely that the Y184F mutation plays a causal role in reduced artemisinin resistance.

pfmdr1 gene amplification was not associated with reduced artemisinin susceptibility. In fact, the opposite was found. In western Cambodia, the pfmdr1 copy numbers were significantly lower in the parasite samples obtained in 2007 than in those obtained 2 years previously, in 2005. This coincided with a change in drug policy in the region from the use of artesunate-mefloquine to the use of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine in 2006. This has considerably diminished the mefloquine drug pressure in the Pailin area. In vitro, pfmdr1 amplification can readily be induced by exposure to low concentrations of mefloquine, and it has been estimated that the frequency of amplification and deamplification of the gene is very high, at about one event every 108 mitoses during the asexual cycle of P. falciparum (14). This high frequency of amplification and deamplification fits with the observations made in the current study, with rapid deamplification of pfmdr1 copy numbers occurring after mefloquine pressure is removed from the population. In the absence of mefloquine, the amplified pfmdr1 gene and gene products confer a fitness disadvantage (14), possibly through the increased energy demands of the ATP-consuming ATP-binding cassette transporter.

PfATPase6, the product of the pfserca gene, has been suggested to be a specific target of the artemisinin drugs (8). In vitro resistance to artemether in parasites obtained from French Guiana (but not Cambodia) was linked to the S769N mutation in pfserca. In the present study, mutations in the pfserca gene were infrequent in both western Cambodia and northwestern Thailand, and there was no clear pattern, excluding mutations in this gene as a cause of artemisinin resistance.

The mitochondrial inner membrane is a site of intense electron transfer, which is inherent to its function, and is thus a potential site of artemisinin activation, which requires reduction of the unique endoperoxide bridge generating carbon-based free radicals (12). Although mutations in the COXIII gene at the I239V position were found in 50% of the parasites, the frequency of this mutation did not differ between sites with artesunate-resistant and -sensitive parasite strains.

The ubp-1 gene encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme was identified as the gene conferring artemisinin resistance in a rodent model of infection with P. chabaudi. The equivalent mutations, V739F and V770F, however, were not identified in P. falciparum. Underlying differences in chloroquine resistance do not confound the lack of correlation between the candidate genes and artemisinin resistance, since the pfCRT K76T mutation was present in all parasite strains.

Microsatellite typing strongly suggests that a slow parasite clearance rate in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria in Pailin is a heritable trait of the parasite (3), implying that a genetic change in the parasite confers artemisinin resistance rather than epigenetic causes. Since mutations (and for pfmdr1 also amplification) in the candidate genes investigated here do not account for artesunate resistance, other approaches have to be followed. These include whole-genome sequencing of resistant parasite genes for comparison with the sequences of sensitive strains, analysis of gene expression profiles using microarrays, microsatellite mapping, and genome-wide hybridization and single nucleotide polymorphism mapping (2, 13, 15, 16). These findings do not exclude the possibility that the gene products of the genes examined play a role in the mechanism of artemisinin's action, since resistance can be conferred through a variety of mechanisms, such as changes in influx and efflux mechanisms. Also, in case artemisinin resistance is conferred by multiple gene mutations, with each contributing to a different extent to the resistant phenotype, the small sample size of this study might have precluded their detection.

In summary, although artemisinin resistance in western Cambodia seems to be a heritable genetic trait, none of the candidate genes suggested by earlier studies confer artemisinin resistance. The use of a genome-wide approach by whole-genome sequencing and gene expression transcriptome studies to identify the molecular basis of artemisinin resistance is now indicated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Colin Sutherland for his support.

This study was supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust of Great Britain (Major Overseas Programme—Thailand Unit Core Grant), the Li Ka Shing Foundation (grant B9RMXT0-2), the Global Malaria Program, and the WHO (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation grant 48821 and Western Pacific Regional Office grant WP/07/66224 CAM). M.I. is a Wellcome Trust intermediate fellow (grant 080867/Z/06/Z). M.I. is supported by the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) and Commission on Higher Education (CHE).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afonso, A., P. Hunt, S. Cheesman, A. C. Alves, C. V. Cunha, V. do Rosario, and P. Cravo. 2006. Malaria parasites can develop stable resistance to artemisinin but lack mutations in candidate genes atp6 (encoding the sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase), tctp, mdr1, and cg10. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:480-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, M. O., J. Sherrill, P. B. Madrid, A. P. Liou, J. L. Weisman, J. L. DeRisi, and R. K. Guy. 2006. Parallel synthesis of 9-aminoacridines and their evaluation against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 14:334-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, T. J. C., S. Nkhoma, J. T. Williams, M. Imwong, P. Yi, D. Socheat, D. Das, K. Chotivanich, N. P. J. Day, N. J. White, and A. M. Dondorp. 2010. Malaria parasite “twin” studies suggest a genetic basis for artemisinin resistance. J. Infect. Dis. 201:1326-1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes, K. I., D. N. Durrheim, F. Little, A. Jackson, U. Mehta, E. Allen, S. S. Dlamini, J. Tsoka, B. Bredenkamp, D. J. Mthembu, N. J. White, and B. L. Sharp. 2005. Effect of artemether-lumefantrine policy and improved vector control on malaria burden in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS Med. 2:e330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowman, A. F., and S. Karcz. 1993. Drug resistance and the P-glycoprotein homologues of Plasmodium falciparum. Semin. Cell Biol. 4:29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dondorp, A. M., F. Nosten, P. Yi, D. Das, A. P. Phyo, J. Tarning, K. M. Lwin, F. Ariey, W. Hanpithakpong, S. J. Lee, P. Ringwald, K. Silamut, M. Imwong, K. Chotivanich, P. Lim, T. Herdman, S. S. An, S. Yeung, P. Singhasivanon, N. P. Day, N. Lindegardh, D. Socheat, and N. J. White. 2009. Artemisinin resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 361:455-467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duraisingh, M. T., P. Jones, I. Sambou, L. von Seidlein, M. Pinder, and D. C. Warhurst. 2000. The tyrosine-86 allele of the pfmdr1 gene of Plasmodium falciparum is associated with increased sensitivity to the anti-malarials mefloquine and artemisinin. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 108:13-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eckstein-Ludwig, U., R. J. Webb, I. D. Van Goethem, J. M. East, A. G. Lee, M. Kimura, P. M. O'Neill, P. G. Bray, S. A. Ward, and S. Krishna. 2003. Artemisinins target the SERCA of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 424:957-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt, P., A. Afonso, A. Creasey, R. Culleton, A. B. Sidhu, J. Logan, S. G. Valderramos, I. McNae, S. Cheesman, V. do Rosario, R. Carter, D. A. Fidock, and P. Cravo. 2007. Gene encoding a deubiquitinating enzyme is mutated in artesunate- and chloroquine-resistant rodent malaria parasites. Mol. Microbiol. 65:27-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jambou, R., E. Legrand, M. Niang, N. Khim, P. Lim, B. Volney, M. T. Ekala, C. Bouchier, P. Esterre, T. Fandeur, and O. Mercereau-Puijalon. 2005. Resistance of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates to in-vitro artemether and point mutations of the SERCA-type PfATPase6. Lancet 366:1960-1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korenromp, E. L., B. G. Williams, E. Gouws, C. Dye, and R. W. Snow. 2003. Measurement of trends in childhood malaria mortality in Africa: an assessment of progress toward targets based on verbal autopsy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meshnick, S. R. 2002. Artemisinin: mechanisms of action, resistance and toxicity. Int. J. Parasitol. 32:1655-1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickard, A. L., C. Wongsrichanalai, A. Purfield, D. Kamwendo, K. Emery, C. Zalewski, F. Kawamoto, R. S. Miller, and S. R. Meshnick. 2003. Resistance to antimalarials in Southeast Asia and genetic polymorphisms in pfmdr1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2418-2423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preechapornkul, P., M. Imwong, K. Chotivanich, W. Pongtavornpinyo, A. M. Dondorp, N. P. Day, N. J. White, and S. Pukrittayakamee. 2009. Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 amplification, mefloquine resistance, and parasite fitness. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1509-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Price, R. N., A. C. Uhlemann, A. Brockman, R. McGready, E. Ashley, L. Phaipun, R. Patel, K. Laing, S. Looareesuwan, N. J. White, F. Nosten, and S. Krishna. 2004. Mefloquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum and increased pfmdr1 gene copy number. Lancet 364:438-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sidhu, A. B., A. C. Uhlemann, S. G. Valderramos, J. C. Valderramos, S. Krishna, and D. A. Fidock. 2006. Decreasing pfmdr1 copy number in Plasmodium falciparum malaria heightens susceptibility to mefloquine, lumefantrine, halofantrine, quinine, and artemisinin. J. Infect. Dis. 194:528-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sisowath, C., J. Stromberg, A. Martensson, M. Msellem, C. Obondo, A. Bjorkman, and J. P. Gil. 2005. In vivo selection of Plasmodium falciparum pfmdr1 86N coding alleles by artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem). J. Infect. Dis. 191:1014-1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uhlemann, A. C., A. Cameron, U. Eckstein-Ludwig, J. Fischbarg, P. Iserovich, F. A. Zuniga, M. East, A. Lee, L. Brady, R. K. Haynes, and S. Krishna. 2005. A single amino acid residue can determine the sensitivity of SERCAs to artemisinins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12:628-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valderramos, S. G., and D. A. Fidock. 2006. Transporters involved in resistance to antimalarial drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27:594-601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. 1996. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.