Abstract

The amino acid at position 36 of the HIV-1 protease differs among various viral subtypes, in that methionine is usually found in subtype B viruses but isoleucine is common in other subtypes. This polymorphism is associated with higher rates of treatment failure involving protease inhibitors (PIs) in non-subtype B-infected patients. To investigate this, we generated genetically homogeneous wild-type viruses from subtype B, subtype C, and CRF02_AG full-length molecular clones and showed that subtype C and CRF02_AG I36 viruses exhibited higher levels of resistance to various PIs than their respective M36 counterparts, while the opposite was observed for subtype B viruses. Selections for resistance with each variant were performed with nelfinavir (NFV), lopinavir (LPV), and atazanavir (ATV). Sequence analysis of the protease gene at week 35 revealed that the major NFV resistance mutation D30N emerged in NFV-selected subtype B viruses and in I36 subtype C viruses, despite polymorphic variation. A unique mutational pattern developed in subtype C M36 viruses selected with NFV or ATV. The presence of I47A in LPV-selected I36 CRF02_AG virus conferred higher-level resistance than L76V in LPV-selected M36 CRF02_AG virus. Phenotypic analysis revealed a >1,000-fold increase in NFV resistance in I36 subtype C NFV-selected virus with no apparent impact on viral replication capacity. Thus, the position 36 polymorphism in the HIV-1 protease appears to have a differential effect on both drug susceptibility and the viral replication capacity, depending on both the viral subtype and the drug being evaluated.

The high rate of mutation of HIV-1 isolates belonging to group M permits the phylogenetic taxonomic division of viral variants into multiple subtypes, currently designated A1 to A4, B, C, D, F1, F2, G, H, J, and K (19, 37). Furthermore, genomic recombination between different HIV-1 subtypes (resulting from co- or superinfection) has led to the circulation of genetically mosaic HIV-1 conventionally termed “circulating recombinant forms” (CRFs) (19, 33, 37). Non-subtype B HIV-1 subtypes constitute >90% of the isolates in the current pandemic (14, 38), with over 50% of new infections now being characterized as subtype C HIV-1 (2, 3, 38). Given that most antiretroviral drug design and resistance research has utilized subtype B (5, 16, 24, 28, 30, 31, 35, 40), there is a paucity of information in regard to drugs and non-subtype B subtypes. Since most globally accessible first-line therapies consist of reverse transcriptase (RT) inhibitors, it is known that second-line regimens will commonly need to include protease inhibitors (PIs) to counteract the development of drug resistance (DR). However, the nucleotide sequences of the HIV-1 protease (PR) of subtype B and C HIV-1 are notably different (8, 18) due to polymorphisms that might affect the development of DR. Hence, we wished to define the role of a suspect PR polymorphism in the context of HIV-1 evolution under PI pressure.

An isoleucine at position 36 (I36) in PR is found in 13% of subtype B viruses but in over 80% of subtype C and CRF02_AG (A/G) viruses (28, 32). After PI treatment, the prevalence of this polymorphism increases to 35% and 90% in patients infected with subtype B and non-subtype B viruses, respectively (32), and the presence of I36 in PR is linked to a higher rate of treatment failure (29). Furthermore, biochemical studies with subtype A and C recombinant I36 PR revealed that the PR enzymes of non-subtype B viruses have a higher Ki and greater catalytic efficiency than subtype B viruses (39) and that introduction of I36 into subtype B HIV-1 results in a higher virus replication capacity in both the absence and presence of PIs (15).

Accordingly, we hypothesized that the presence of methionine or isoleucine at position 36 within PR (M36 and I36, respectively) might impact the development of PI-selected resistance. To this end, we introduced I36 or M36 into full-length HIV-1 molecular clones of subtypes B, C, and CRF02_A/G and cultured both the wild-type and mutated resultant viruses for 35 weeks in cord blood mononuclear cells (CBMCs) under increasing PI drug concentrations. The drugs atazanavir (ATV) and nelfinavir (NFV) were chosen for study because they have demonstrated a low genetic barrier for resistance, while lopinavir (LPV) was used because of its high genetic barrier for resistance (25, 30). The genotypic profile, phenotypic susceptibility, and replication capacities of the drug-selected viruses were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Molecular clones, virus production, and drugs.

ATV, NFV, and LPV were kind gifts from Bristol-Myers Squibb Inc., Pfizer Inc., and Abbott Laboratories Inc., respectively.

Full-length subtype-specific infectious HIV-1 molecular clones were used in this study. The pNL4-3 plasmid (catalogue number 114, GenBank accession number AF324493) was obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH (Bethesda, MD), courtesy of Malcolm Martin (1). pAG_97 (GenBank accession number AB052867) and pINDIE C (GenBank accession number AB023804) were kindly provided by M. Takahoko (36) and N. Mochizuki (27), respectively. These clones were used to create I36 and M36 polymorphic variants using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The subtype B M36I clone was created using the following forward and reverse primers: 5′-GCAGATGATACAGTATTAGAAGAAATAAATTTGCCAGGAAGATGG-3′ and 5′-CCATCTTCCTGGCAAATTTATTTCTTCTAATACTGTATCATCTGC-3′, respectively. The subtype C I36M clone was created using the following forward and reverse primers: 5′-GCAGATGATACAGTATTAGAAGAAATGAATTTGCCAGGAAAATGGAAACC-3′ and 5′-GGTTTCCATTTTCCTGGCAAATTCATTTCTTCTA ATACTGTATCATCTGC-3′, respectively. Subtype CRF02_AG I36M was created with primers 5′-GATGATACAGTACTAGAAGACATGGACTTACCAGGAAAATGG-3′ and 5′-CCATTTTCCTGGTAAGTCCATGTCTTCTAGTACTGTATCATC-3′. Underlined codons denote sites at which single nucleotide substitutions were introduced.

Viral plasmids were transfected into 293T cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions, to generate replication-competent HIV-1 inocula. The virus-containing supernatants were filtered and tested for reverse transcriptase (RT) activity (10, 20). RT-PCR was used to amplify the viral RNA isolated from the viral supernatants in order to confirm the presence of the I36 or M36 PR via sequencing of the amplification product.

Standardization of virus infections for selection studies.

Viruses derived from subtype-specific molecular clones were used to infect CBMCs stimulated for 72 h with phytohemagglutinin in complete RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Invitrogen), penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen), l-glutamine (Invitrogen), and interleukin-2 (IL-2; Roche) (34). RT activity was quantified as described elsewhere (10, 20), and the results were used to determine the amounts of stock virus required to infect CBMCs on day 0 to equalize the infections with the different viruses on day 7 in the selection experiments.

Selection of resistance mutations to PIs in CBMCs.

CBMCs were infected with viruses to yield equalized infections at day 7 postinfection. On day 7, PIs were first included in the culture medium at the drug concentration needed to block HIV replication by 25% (EC25). Infections were maintained in these cultures (at 37°C under 5% CO2) at increasing PI concentrations. Fresh CBMCs (4 × 106) were added in complete medium every 7 days for the duration of the experiment. Infected CBMCs in the absence of drug were included for each of the tested viral variants and were maintained throughout the study to serve as no-drug control cultures.

Genotyping.

Viral RNA was extracted from the culture supernatants at 0, 25, and 35 weeks using a Qiagen QIAmp viral extraction kit (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Viral RNA was amplified via RT-PCR, and nested PCR was employed to amplify the HIV-1 protease gene. The resulting DNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), as specified by the manufacturer. The presence of the expected 1.7-kb PCR product was confirmed by running 5 μl of each product on a 1% agarose gel. The samples were directly sequenced with subtype-specific PR primers using the BigDye Terminator cycle sequencing kit (version 1.1; Applied Biosystems). The sequences were run on an ABI Prism 3130xl genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The data were analyzed using SeqScape software (version 2.5), and the PR sequences were aligned using Bioedit software, version 7.0.

Phenotypic drug susceptibility.

Wild-type (week 0) and viral variants selected with ATV, NFV and LPV were phenotyped against the PIs ATV, NFV, and LPV at 0, 25, and 35 weeks using drug concentrations ranging from 0.04 nM to 10 μM in 96-well plates. CBMCs were infected for 2 h with week 0 or PI-selected virus and plated at 5 × 105 cells per well in the presence of a PI. Following 3 days of incubation, the viral cultures were replenished with fresh RPMI 1640 complete medium (Invitrogen) containing serial drug dilutions to determine a dose-response. On day 7, the culture supernatants were collected to quantify RT activity as a reflection of viral replication. The data were analyzed using Prism software, version 5.0 (GraphPad, Inc.), to determine the EC50 for each PI tested.

Viral replication assays.

TZM-bl cells (104 cells/well) (19, 29) were added to 96-well plates in 100 μl of Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine (Invitrogen) and infected with each virus polymorphic variant isolated at weeks 0 and 35. The virus-cell cultures were permitted to incubate for 48 h, after which the cells were rinsed with 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently lysed with 1% cell lysis buffer (diluted from 5× cell lysis buffer; Promega). Luciferase activity was measured by use of a luciferase assay system (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The relative light units were quantified using a 1450 LSC luminescence counter (MicroBeta TriLux luminometer; Perkin-Elmer).

RESULTS

Generation and verification of subtype-specific HIV-1 M36 and I36 HIV-1.

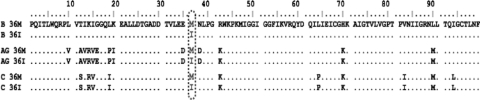

To evaluate the impact of M36 and/or I36 on the development of PI resistance, genetically homogeneous viral variants coding for M36 and/or I36 were generated from full-length subtype-specific HIV-1 molecular clones. Site-directed mutagenesis was employed to introduce the less frequently occurring polymorphisms into subtype B, subtype C, and CRF02_AG clones to ultimately obtain six HIV-1 polymorphic variants. Each viral variant was sequenced to confirm the presence of the introduced amino acid (Fig. 1). The results show that the only differences within a given subtype were at PR position 36.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of protease from parental HIV-1. Shown are the predicted protease amino acid sequences from the six different parental HIV-1 variants generated from subtype-specific full-length molecular clones: subtype B (B 36M and B 36I), CRF02_AG (AG 36M and AG 36I), and subtype C (C 36M and C 36I). Protease amino acid sequences were ultimately determined by RT-PCR amplification of genomic HIV-1 RNA isolated from transfected 293T cell supernatants and the subsequent sequencing of the amplification products. Data analyses and alignments were completed using SeqScape and BioEdit software, respectively. Vertical dashes and numbers indicate amino acid position. Dots indicate identical residues using subtype B (B 36M) as the reference sequence.

Baseline phenotypes in CBMCs and viral replication in the TZM-bl reporter cell line.

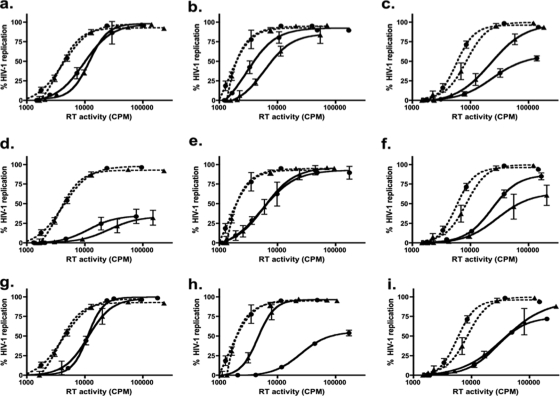

Most commercially available EC50 tests use viruses generated from a standard laboratory-adapted backbone that contains an insert of a specific drug-targeted HIV-1 genomic region (e.g., pol) derived from a patient sample or viral isolate. Since polymorphisms can affect drug susceptibility (9, 15, 16) and commercial testing does not fully consider HIV-1 genetic diversity, we performed phenotypic analyses with subtype-specific full-length parental/preselected polymorphic virus variants in CBMCs using ATV, NFV, and LPV. In general, the less frequently occurring polymorphisms appeared to increase drug susceptibility within each subtype (Table 1 ). For example, in the presence of either NFV or LPV, M36 subtype B virus was approximately two times more resistant than the I36 polymorphic variant. Similarly, the I36 subtype C and CRF02_A2 variants appeared to be slightly more adept than their respective M36 counterparts at replicating in the presence of all tested PIs (Table 1). To assess the replication capacity of each of the parental viral variants, a short-term TZM-bl cell-based replication assay was employed. The presence of M36 or I36 in PR did not appear to compromise the replication capacity within subtype B (Fig. 2 a), subtype C (Fig. 2b), or CRF02_AG (Fig. 2c) virus, although minor differences in replication capacity between subtypes were observed (C > B > A/G).

TABLE 1.

Major mutations, polymorphisms, and EC50 values for wild-type and drug-selected HIV-1 isolates

| PI | Wk | Subtype B |

Subtype C |

CRF02_AG |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (M36)a |

(I36) |

(M36) |

(I36) |

(M36) |

(I36) |

||||||||

| Mutations | EC50 (nM) ± SEMb | Mutations | EC50 (nM) ± SEM | Mutations | EC50 (nM) ± SEM | Mutations | EC50 (nM) ± SEM | Mutations | EC50 (nM) ± SEM | Mutation(s) | EC50 (nM) ± SEM | ||

| NFV | 0 | 16.3 ± 0.87 | 9.8 ± 0.78 | 1.67 ± 0.87 | 3.0 ± 0.94 | 5.7 ± 0.75 | 8.7 ± 0.85 | ||||||

| 35 | D30N,c (M36), M46I, A71T,d V77I | 1,139 ± 1.27 (70)e | D30N, L33I, (I36), M46I, N88D | 1,463 ± 1.12 (149) | L23I, (M36), M46I, L89T | 272 ± 0.91 (163) | D30N, E35G, (I36), I85V, L90L/Mf | 3,473 ± 1.12 (1,158) | L33I, (M36), M46I, A71T | 202 ± 1.20 (35) | (I36), M46L | 55 ± 1.30 (6) | |

| LPV | 0 | 12.4 ± 0.81 | 7.4 ± 0.87 | 2.2 ± 1.02 | 3.4 ± 1.16 | 6.0 ± 0.90 | 14.5 ± 1.16 | ||||||

| 35 | L10F, (M36), V82A | 196 ± 1.13 (16) | NDg | L10R, (M36), M46I, I54V, V82S | 418 ± 0.97 (190) | L23I, (I36), M46I/M, L76V | 157 ± 1.01 (46) | (M36), M46I, L76V, I84V | 134 ± 0.82 (22) | (I36), M46I, I47A, I84V | 1,467 ± 1.30 (101) | ||

| ATV | 0 | 3.0 ± 1.33 | 3.0 ± 1.33 | 0.3 ± 1.33 | 1.0 ± 1.33 | 2.0 ± 1.27 | 5.5 ± 1.6 | ||||||

| 35 | M46I, I50L, N88S | 183 ± 1.37 (61) | ND | 7.1 ± 1.4 (2.4) | L23I, (M36), M46I/M, L89T | 88 ± 1.28 (293) | E35G, (I36) | 3.7 ± 1.34 (3.7) | (M36), I50FILV, A71V | 9.3 ± 1.31 (4.7) | (I36) | 18.6 ± 1.2 (3.4) | |

Lightface type in parentheses indicates polymorphisms.

The data analyzed were from at least two independent experiments performed in duplicate.

All boldface type not in parentheses indicates major PI-specific selected resistance mutations, according to the Stanford database.

All lightface type not in parentheses indicates non-major PI-specific selected resistance mutations, according to the Stanford database.

All boldface data in parentheses indicate the fold resistance compared to that of the preselected (week 0) HIV-1 parental variants.

A major resistance mutation was observed at week 25 but not at week 35.

ND, not done.

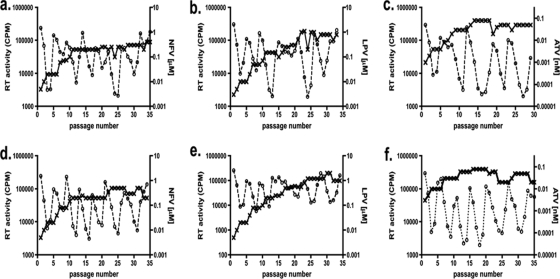

FIG. 2.

Replication capacity of parental HIV-1 variants compared to that of drug-selected progeny HIV-1. The results for parental isolates and subtype B, subtype C, and CRF02_AG HIV-1 isolates selected with NFV (a, b, and c, respectively), LPV (d, e, and f, respectively), and ATV (g, h, and i, respectively) are shown. Percent replication of preselected (---) and drug-selected (—) M36 (▴) and I36 (•) HIV-1 in TZM-bl cells are expressed as a function of HIV-1 RT activity (cpm). Data points depict the averages (mean ± standard deviation) of three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Impact of the M/I36 PR polymorphism on resistance mutations, drug susceptibility, and viral replication.

To better understand the patterns of PI resistance mutations in non-subtype B subtypes and the impact of the M36I polymorphism on drug resistance, full-length replication-competent clonal viruses (B M36, B M36I, C I36, C I36M, A/G I36, and A/G I36M) were grown under increasing PI pressure for 35 weeks. The viruses were phenotyped and genotyped, and replication capacity was measured at weeks 0 and 35 (Table 1 and Fig. 2, respectively). Of note, all viruses grown under increasing PI pressure maintained the original parental genotypes at PR position 36, and the genotypes of the no-drug control cultures genotyped at week 35 did not differ from the parental genotypes in either the viral PR or RT genes (data not shown).

(i) Subtype B selections.

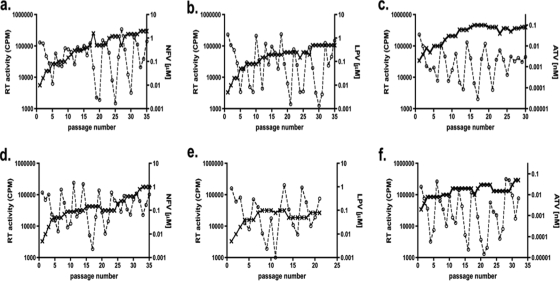

Both M36 and I36 subtype B viruses selected with NF developed the D30N and M46I mutations at as early as 25 weeks (data not shown), and these mutations continued to be present at week 35 (Table 1). The level of drug resistance was ∼2-fold higher at week 35 in the I36 subtype B virus (149-fold more resistant to parental virus) than in the M36 subtype B virus (70-fold more resistant to parental virus) (Table 1), even though greater NFV pressure was applied to the M36 subtype B viral culture (Fig. 3 a and d). The resistance mutations L10F and V82A emerged in M36 subtype B LPV-selected virus and conferred a 16-fold increase in the EC50 (Table 1). M36 subtype B virus grown under ATV pressure developed two major ATV resistance mutations (according to the Stanford Database), I50L and N88S, which conferred a 61-fold increase in the EC50 (Table 1). Even though similar ATV pressure was applied to both cultures (Fig. 3c and f), the fold increases in the EC50s were modest with the I36 variant, possibly due to the absence of major resistance mutations. Replication capacity analysis of the NFV- and ATV-selected subtype B viruses revealed only a modest difference between the M36 and I36 viruses and their respective parental counterparts (Fig. 2a and g). In contrast, viral replication capacity was severely compromised in the LPV-selected subtype B polymorphic variants (Fig. 2d).

FIG. 3.

Growth of subtype B M/I36 HIV-1 in the presence of drug. CBMCs were infected and cultured over 35 weeks with subtype B M36 (a to c) or I36 (d to f) HIV-1 in the presence of NFV (a and d), LPV (b and e), or ATV (c and f). Drug (- - × - -) concentrations (μM for NFV and LPV and nM for ATV, right vertical axis) were adjusted every week, according to virus replication (- - ○ - -), measured as RT activity (cpm, left vertical axis) in the cell culture supernatants. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

(ii) Subtype C selections.

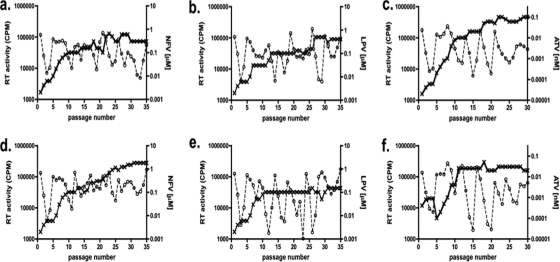

By week 35, the evolutionary paths of NFV- and ATV-selected subtype C polymorphic variants diverged. The resistance mutations L23I, M46I, and L89T emerged in M36 subtype C cultures at week 35 with ATV and NFV pressure (Table 1), while the drug resistance mutations D30N, E35G, and I85V and the accessory mutation E35G were detected in NFV- and ATV-selected I36 subtype C cultures, respectively (Table 1). A higher level of NFV pressure was applied to the I36 viral cultures than to the M36 viral cultures (Fig. 4 a and d), which may have contributed to the greater fold resistance observed (1,158-fold and 163-fold, respectively) (Table 1). The presence of the primary resistance mutation L90M in NFV-selected I36 subtype C (which emerged at week 25 but which was undetectable by week 35) may account for the higher level of NFV resistance. In contrast, ATV-selected M36 subtype C virus exhibited higher-level ATV fold resistance (Table 1) and withstood higher-level ATV pressure (Fig. 4c) than the I36 virus did (Table 1 and Fig. 4f, respectively). In the selections with both NFV and ATV, the viral variant that was best able to endure higher-level PI pressure and that exhibited higher-level resistance also possessed superior replication ability in the TZM-bl cell assay. With ATV-selected variants, the difference was marked (Fig. 2 h); however, for NFV-selected viruses, differences in replication capacity were modest (Fig. 2b).

FIG. 4.

Growth of M/I36 subtype C HIV-1 in the presence of drug. CBMCs were infected and cultured over 35 weeks with M36 subtype C (a to c) or I36 (d to f) HIV-1 in the presence of NFV (a and d), LPV (b and e), or ATV (c and f). Drug (- - × - -) concentrations (μM for NFV and LPV and nM for ATV, right vertical axis) were adjusted every week, according to virus replication (- - ○ - -), measured as RT activity (cpm, left vertical axis) in the cell culture supernatants. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

The development of resistance mutations in LPV-selected I36 subtype C virus was slower than that with M36 virus. The I36 viral cultures selected with LPV contained the L76V major mutation at week 35, at which time a second mutation, M46I/M, was beginning to emerge (Table 1). In contrast, the LPV-selected M36 subtype C virus contained three major mutations after 35 weeks: M46I, I54V, and V82S (Table 1). Furthermore, higher concentrations of LPV could be applied to the M36 viruses than to the I36 viruses (Fig. 4b and e). Accordingly, the observed resistance to LPV (Table 1) was greater for LPV-selected M36 subtype C virus than I36 virus. However, the replication capacities for both LPV-selected subtype C polymorphic variants in the short-term replication assay were very similar (Fig. 2e).

(iii) CRF02_AG selections.

NFV-selected M36 CRF02_AG virus withstood greater PI pressure over 35 weeks (Fig. 5 a and d), developed more resistance mutations (Table 1), presented with a greater fold NFV resistance (Table 1), and had a replication capacity similar to that of parental virus, in contrast to NFV-selected I36 CRF02_AG virus, which did not (Fig. 2c). The accessory mutations detected in the NFV-selected M36 CRF02_AG virus, L33I and A71T, may have contributed to a higher-level NFV resistance phenotype than was seen with NFV-selected I36 CRF02_AG (Table 1). The opposite was observed with LPV-selected CRF02_AG viruses. Even though similar LPV pressure was applied to both types of viral cultures over time (Fig. 5b and e), the I36 CRF02_AG virus developed greater LPV fold resistance (Table 1) and possessed a better replication capacity than the LPV-selected M36 CRF02_AG virus (Fig. 2f). The major and cross-resistance LPV resistance mutations, M46I and I84V, respectively, were detected in both M36 and I36 CRF02_AG LPV-selected viruses (Table 1). However, a rare I47A major LPV resistance mutation was detected in LPV-selected I36 CRF02_AG virus (Table 1). The simultaneous presence of I47A, together with M46I and I84V, may be the reason for the higher fold resistance to LPV seen in the I36 viruses than in the M36 viruses.

FIG. 5.

Growth of CRF02_AG M/I36 HIV-1 in the presence of drug. CBMCs were infected and cultured over 35 weeks with CRF02_AG M36 (a to c) or I36 (d to f) HIV-1 in the presence of NFV (a and d), LPV (b and e), or ATV (c and f). Drug (- - × - -) concentrations (μM for NFV and LPV and nM for ATV, right vertical axis) were adjusted every week according to virus replication (- - ○ - -) measured as RT activity (cpm, left vertical axis) in the cell culture supernatants. Data represent means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

ATV-selected M36 CRF02_AG viruses developed the accessory mutation A71V and also started to develop a major resistance mutation at position 50 in PR (Table 1). In contrast, no resistance mutations were observed in the ATV-selected I36 CRF02_AG viruses (Table 1), which may be due, in part, to the modestly lower ATV pressure that was applied to the viral cultures over time (Fig. 5c and f). At week 35, a mixed signal was present at amino acid 50 at the first nucleotide position (XTT) of these viruses (Table 1). This probably represents a mutation that is only beginning to emerge but one for which the signal was not yet strong enough to be resolved by the chromatogram. The fold resistance to ATV (Table 1) and the replication capacity (Fig. 2i) were comparable between the I36 and M36 viruses; of note, these viruses did not replicate as well as the parental virus (Fig. 2i).

DISCUSSION

The impact of a single nucleotide polymorphism at position 36 in PR on the selection of NFV, LPV, and ATV resistance mutations in HIV-1 subtype B and non-subtype B subtypes was investigated in culture using CBMCs infected with genetically homogeneous virus containing defined polymorphisms. Although previous work has suggested that subtype B clonal virus encoding I36 in PR should display greater drug resistance and possess a higher replicative capacity than M36 virus (15, 40), this had not yet been assessed in other HIV-1 subtypes or studied in the context of drug resistance mutation development.

These studies are both labor-intensive and tedious, requiring viral cultivation over many months. Accordingly, it has not been possible to conduct all of this work on repeat occasions. However, certain of the selections were carried out in parallel in different cultures, yielding similar results on each occasion. The possibility that stochastic changes may also have affected viral susceptibility to the PIs used cannot be ruled out. We also cannot rule out a potential role for mutations within Gag, including cleavage site mutations, as has previously been shown (21, 25, 42). An investigation of this topic is beyond the scope of this paper.

At the baseline, we observed that only modest differences in NFV, LPV, and ATV resistance may be attributed to polymorphic variation at position 36 in PR (Table 1). I36 HIV-1 may have a slight natural competitive advantage over M36 HIV-1 that is independent of drug pressure. We also assessed viral replication capacity in the TZM-bl indicator cell line. The presence of M36 or I36 in PR did not compromise the replication capacity of subtype B (Fig. 2a), subtype C (Fig. 2b), or CRF02_AG (Fig. 2c), although minor differences in replication capacity between subtypes were observed (C > B > A/G). It is possible that some evolutionary divergence may have resulted from the introduction of PI-containing antiretroviral therapy (ART) in developed countries. Since the majority of HIV-1 infections in developed countries are subtype B, it is possible that the clinical prevalence of M36 subtype B over I36 subtype B is a function of the selective pressure of PI-containing ART.

NFV pressure led to the development of mutations in I36 subtype B virus that resulted in a phenotype more resistant than that found with M36 (150-fold and 70-fold, respectively) (Table 1). This agrees with the concept that the I at position 36 in PR acts as a resistance mutation only when other resistance mutations are present (26). In addition, the combination of mutations L33I and N88D together with I36 may provide the virus with a resistance advantage over the combination of A71T and V77I together with M36 (Table 1); a negligible loss of replication capacity was observed for both viruses (Fig. 2a). In the case of subtype B and ATV pressure, the presence of M36 as opposed to I36 may have favored resistance development without compromising viral replication capacity (Table 1 and Fig. 2g).

The V82A mutation is known to emerge in subtype B HIV-1 following LPV therapy and to modestly decrease the level of binding between PIs and PR because of changes to the enzyme active-site cavity (17, 22, 23). Our results show that V82A results in a modest increase in the LPV fold resistance (Table 1) at great expense to viral replication capacity (Fig. 2d). Additional accessory and/or compensatory mutations are possibly needed to restore viral replication capacity in this context.

Gag and Gag-Pol cleavage site mutations have been described, but the frequency with which they occur in the context of non-subtype B subtypes is unknown. Both compensatory mutations that appear following the emergence of PI resistance and cleavage site mutations can partially restore replication capacity (11, 21, 25, 42). It is possible that cleavage site mutations may have been present in some of our viruses.

A unique mutational signature (L23I, M46I, and L89T) was present in subtype C M36 viruses grown under increasing NFV or ATV pressure. We also detected this mutational pattern in other non-subtype B drug-selected viruses that originated from clones or clinical isolates (data not shown). These PI-selected viruses displayed >150-fold resistance (Table 1) to the PIs used in the selections. However, this elevated level of resistance did not result in a replicative disadvantage (Fig. 2b and h). The conformational changes caused by these mutations possibly reduce the binding affinity between the PIs and the viral PR (8, 23).

After 35 weeks of NFV pressure, M36 CRF02_AG virus manifested a greater fold resistance and replication capacity than I36-encoding viruses (Table 1 and Fig. 2c). Conceivably, either or both the L33I and A71T mutations may help to restore replicative capacity and/or increase NFV resistance in M36-containing CRF02_AG viruses to an extent that exceeds that seen with I36. In contrast to the subtype B and I36 subtype C viruses, none of the CRF02_AG polymorphic HIV-1 variants developed the D30N mutation following NFV pressure, in agreement with previous findings (7, 9, 10, 13, 32). These results contribute to the increasing body of evidence that different HIV-1 subtypes develop different resistance mutations or develop them at differential rates following exposure to the same PI (4, 6, 10, 12, 13, 16).

Full-length non-subtype B subtype replication-competent molecular clones are scarce. Moreover, no work has previously investigated which polymorphisms affect resistance patterns in non-subtype B subtypes, a clinical impossibility given the paucity of non-subtype B-infected patients who have been treated with atazanavir and darunavir. Few such samples have ever been genotyped for resistance, the only exception being subtype C in the context of lopinavir.

We chose to focus on the I36 polymorphism, because it was found to be linked to a higher rate of treatment failure among treatment-naïve patients infected with non- subtype B subtypes (15, 28, 29, 32). Our results could not ascertain whether I36 is the determining factor that predicts which resistance mutations will emerge; rather, it might contribute to the emergence of mutational patterns that eventually develop. This polymorphism appears to affect the resistance level to a different extent among viruses of assorted subtypes exposed to the same PIs. The effect of minor mutations or polymorphisms cannot be extrapolated from data generated for subtype B and applied to interpretations of resistance in non-subtype B subtypes until clinical responses or phenotypic validations have been completed.

In general, the D30N mutation seems to occur commonly in NFV-experienced individuals infected with subtype B viruses and in some subtype C-infected individuals but not in subjects infected with CRF02_AG viruses (7, 10, 13). Our polymorphic HIV-1 selection results are in agreement with these findings (Table 1). The levels of resistance to NFV following 35 weeks of comparable drug pressure were 6-, 70-, and 1,173-fold for CRF02_AG (I36), subtype B (M36), and subtype C (I36) viruses, respectively (Table 1); and the ability of the CRF02_AG polymorphic variants to replicate in TZM-bl cells was compromised.

Our observations suggest that different subtypes might adapt differently following the acquisition of resistance mutations. Subtype C LPV- and NFV-selected clones, in contrast to subtype B and CRF02_AG HIV-1 isolates grown under PI pressure, showed only minimal reductions in replication capacity, despite the presence of polymorphisms, resistance mutations, and increased levels of drug resistance. However, the replication capacity of ATV-selected subtype C virus, in contrast to subtype B and CRF02_AG virus grown under ATV pressure, was greatly reduced, despite the presence of one accessory resistance mutation, low drug pressure, and 3-fold resistance to ATV. In general, among the HIV-1 isolates tested, the rate of emergence of resistance mutations following ATV pressure appeared to be slower than that with selections using NFV or LPV. These findings may be important in the context of widespread NFV and LPV use as part of first-line and second-line PI-based antiretroviral therapy in developing country settings.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The work of J.-L.M.-C. was supported by a Canadian HIV Trials Network Fellowship Award. S.M.S. was supported by a CIHR predoctoral fellowship.

We thank Olga Golubkov for technical assistance, Véronique Michaud for guidance with data analysis, and Bluma G. Brenner for intellectual support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi, A., H. E. Gendelman, S. Koenig, T. Folks, R. Willey, A. Rabson, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 59:284-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arien, K. K., G. Vanham, and E. J. Arts. 2007. Is HIV-1 evolving to a less virulent form in humans? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:141-151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessong, P. O. 2008. Polymorphisms in HIV-1 subtype C proteases and the potential impact on protease inhibitors. Trop. Med. Int. Health 13:144-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner, B., D. Turner, M. Oliveira, D. Moisi, M. Detorio, M. Carobene, R. G. Marlink, J. Schapiro, M. Roger, and M. A. Wainberg. 2003. A V106M mutation in HIV-1 clade C viruses exposed to efavirenz confers cross-resistance to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. AIDS 17:F1-F5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonaguro, L., M. L. Tornesello, and F. M. Buonaguro. 2007. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype distribution in the worldwide epidemic: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. J. Virol. 81:10209-10219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camacho, R., A. Godinho, P. Gomes, A. Abecasis, A. M. Vandamme, C. Palma, A. P. Carvalho, J. Cabanas, and J. Gonçalves. 2005. Different substitutions under drug pressure at protease codon 82 in HIV-1 subtype G compared to subtype B infected individuals including a novel I82M resistance mutation. Antivir. Ther. 10:S151. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaix, M. L., F. Rouet, K. A. Kouakoussui, R. Laguide, P. Fassinou, C. Montcho, S. Blanche, C. Rouzioux, and P. Msellati. 2005. Genotypic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance in highly active antiretroviral therapy-treated children in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 24:1072-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clavel, F., and A. J. Hance. 2004. HIV drug resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 350:1023-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemente, J. C., R. Hemrajani, L. E. Blum, M. M. Goodenow, and B. M. Dunn. 2003. Secondary mutations M36I and A71V in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease can provide an advantage for the emergence of the primary mutation D30N. Biochemistry 42:15029-15035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doualla-Bell, F., A. Avalos, T. Gaolathe, M. Mine, S. Gaseitsiwe, N. Ndwapi, V. A. Novitsky, B. Brenner, M. Oliveira, D. Moisi, H. Moffat, I. Thior, M. Essex, and M. A. Wainberg. 2006. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C on drug resistance mutations in patients from Botswana failing a nelfinavir-containing regimen. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2210-2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doyon, L., G. Croteau, D. Thibeault, F. Poulin, L. Pilote, and D. Lamarre. 1996. Second locus involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 resistance to protease inhibitors. J. Virol. 70:3763-3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grossman, Z., V. Istomin, D. Averbuch, M. Lorber, K. Risenberg, I. Levi, M. Chowers, M. Burke, N. B. Yaacov, and J. M. Schapiro. 2004. Genetic variation at NNRTI resistance-associated positions in patients infected with HIV-1 subtype C. AIDS 18:909-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossman, Z., E. E. Paxinos, D. Averbuch, S. Maayan, N. T. Parkin, D. Engelhard, M. Lorber, V. Istomin, Y. Shaked, E. Mendelson, D. Ram, C. J. Petropoulos, and J. M. Schapiro. 2004. Mutation D30N is not preferentially selected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C in the development of resistance to nelfinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2159-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemelaar, J., E. Gouws, P. D. Ghys, and S. Osmanov. 2006. Global and regional distribution of HIV-1 genetic subtypes and recombinants in 2004. AIDS 20:W13-W23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holguin, A., C. Sune, F. Hamy, V. Soriano, and T. Klimkait. 2006. Natural polymorphisms in the protease gene modulate the replicative capacity of non-B HIV-1 variants in the absence of drug pressure. J. Clin. Virol. 36:264-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantor, R., D. A. Katzenstein, B. Efron, A. P. Carvalho, B. Wynhoven, P. Cane, J. Clarke, S. Sirivichayakul, M. A. Soares, J. Snoeck, C. Pillay, H. Rudich, R. Rodrigues, A. Holguin, K. Ariyoshi, M. B. Bouzas, P. Cahn, W. Sugiura, V. Soriano, L. F. Brigido, Z. Grossman, L. Morris, A. M. Vandamme, A. Tanuri, P. Phanuphak, J. N. Weber, D. Pillay, P. R. Harrigan, R. Camacho, J. M. Schapiro, and R. W. Shafer. 2005. Impact of HIV-1 subtype and antiretroviral therapy on protease and reverse transcriptase genotype: results of a global collaboration. PLoS Med. 2:e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kempf, D. J., J. D. Isaacson, M. S. King, S. C. Brun, Y. Xu, K. Real, B. M. Bernstein, A. J. Japour, E. Sun, and R. A. Rode. 2001. Identifications of genotypic changes in human immunodeficiency virus protease that correlate with reduced susceptibility to the protease inhibitor lopinavir among viral isolates from protease inhibitor-experienced patients. J. Virol. 75:7462-7469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Korber, B., B. Gaschen, K. Yusim, R. Thakallapally, C. Kesmir, and V. Detours. 2001. Evolutionary and immunological implications of contemporary HIV-1 variation. Br. Med. Bull. 58:19-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leitner, T., B. Foley, B. Hahn, et al. 2009. HIV sequence compendium. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics Group, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM.

- 20.Loemba, H., B. Brenner, M. A. Parniak, S. Ma'ayan, B. Spira, D. Moisi, M. Oliveira, M. Detorio, M. Essex, and M. A. Wainberg. 2002. Polymorphisms of cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL) and T-helper epitopes within reverse transcriptase (RT) of HIV-1 subtype C from Ethiopia and Botswana following selection of antiretroviral drug resistance. Antiviral Res. 56:129-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maguire, M. F., R. Guinea, P. Griffin, S. Macmanus, R. C. Elston, J. Wolfram, N. Richards, M. H. Hanlon, D. J. Porter, T. Wrin, N. Parkin, M. Tisdale, E. Furfine, C. Petropoulos, B. W. Snowden, and J. P. Kleim. 2002. Changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag at positions L449 and P453 are linked to I50V protease mutants in vivo and cause reduction of sensitivity to amprenavir and improved viral fitness in vitro. J. Virol. 76:7398-7406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcelin, A. G., P. Flandre, J. Pavie, N. Schmidely, M. Wirden, O. Lada, D. Chiche, J. M. Molina, V. Calvez, and the AI454-176 Jaguar Study Team. 2005. Clinically relevant genotype interpretation of resistance to didanosine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:1739-1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin, P., J. F. Vickrey, G. Proteasa, Y. L. Jimenez, Z. Wawrzak, M. A. Winters, T. C. Merigan, and L. C. Kovari. 2005. “Wide-open” 1.3 A structure of a multidrug-resistant HIV-1 protease as a drug target. Structure 13:1887-1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Cajas, J. L., N. Pant-Pai, M. B. Klein, and M. A. Wainberg. 2008. Role of genetic diversity amongst HIV-1 non-B subtypes in drug resistance: a systematic review of virologic and biochemical evidence. AIDS Rev. 10:212-223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez-Cajas, J. L., and M. A. Wainberg. 2007. Protease inhibitor resistance in HIV-infected patients: molecular and clinical perspectives. Antiviral Res. 76:203-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendoza, C., and V. Soriano. 2004. Resistance to HIV protease inhibitors: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Curr. Drug Metab. 5:321-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mochizuki, N., N. Otsuka, K. Matsuo, T. Shiino, A. Kojima, T. Kurata, K. Sakai, N. Yamamoto, S. Isomura, T. N. Dhole, Y. Takebe, M. Matsuda, and M. Tatsumi. 1999. An infectious DNA clone of HIV type 1 subtype C. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 15:1321-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ode, H., S. Matsuyama, M. Hata, S. Neya, J. Kakizawa, W. Sugiura, and T. Hoshino. 2007. Computational characterization of structural role of the non-active site mutation M36I of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease. J. Mol. Biol. 370:598-607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perno, C. F., A. Cozzi-Lepri, F. Forbici, A. Bertoli, M. Violin, M. Stella Mura, G. Cadeo, A. Orani, A. Chirianni, C. De Stefano, C. Balotta, and A. d'Arminio Monforte. 2004. Minor mutations in HIV protease at baseline and appearance of primary mutation 90M in patients for whom their first protease-inhibitor antiretroviral regimens failed. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1983-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Platt, E. J., K. Wehrly, S. E. Kuhmann, B. Chesebro, and D. Kabat. 1998. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophage tropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2855-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rhee, S. Y., R. Kantor, D. A. Katzenstein, R. Camacho, L. Morris, S. Sirivichayakul, L. Jorgensen, L. F. Brigido, J. M. Schapiro, and R. W. Shafer. 2006. HIV-1 pol mutation frequency by subtype and treatment experience: extension of the HIVseq program to seven non-B subtypes. AIDS 20:643-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rhee, S. Y., M. J. Gonzales, R. Kantor, B. J. Betts, J. Ravela, and R. W. Shafer. 2008. HIV drug resistance database. Stanford University, Stanford, CA. http://hivdb.stanford.edu.

- 33.Robertson, D. L., J. P. Anderson, J. A. Bradac, J. K. Carr, B. Foley, R. K. Funkhouser, F. Gao, B. H. Hahn, M. L. Kalish, C. Kuiken, G. H. Learn, T. Leitner, F. McCutchan, S. Osmanov, M. Peeters, D. Pieniazek, M. Salminen, P. M. Sharp, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber. 2000. HIV-1 nomenclature proposal. Science 288:55-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salomon, H., A. Belmonte, K. Nguyen, Z. Gu, M. Gelfand, and M. A. Wainberg. 1994. Comparison of cord blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells as targets for viral isolation and drug sensitivity studies involving human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2000-2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Snoeck, J., R. Kantor, R. W. Shafer, K. Van Laethem, K. Deforche, A. P. Carvalho, B. Wynhoven, M. A. Soares, P. Cane, J. Clarke, C. Pillay, S. Sirivichayakul, K. Ariyoshi, A. Holguin, H. Rudich, R. Rodrigues, M. B. Bouzas, F. Brun-Vezinet, C. Reid, P. Cahn, L. F. Brigido, Z. Grossman, V. Soriano, W. Sugiura, P. Phanuphak, L. Morris, J. Weber, D. Pillay, A. Tanuri, R. P. Harrigan, R. Camacho, J. M. Schapiro, D. Katzenstein, and A. M. Vandamme. 2006. Discordances between interpretation algorithms for genotypic resistance to protease and reverse transcriptase inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus are subtype dependent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:694-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takahoko, M., M. Tobiume, K. Ishikawa, W. Ampofo, N. Yamamoto, M. Matsuda, and M. Matsumi. 2001. Infectious DNA clone of HIV type 1 A/G recombinant (CRF02_AG) replicable in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 17:1083-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor, B. S., M. E. Sobieszczyk, F. E. McCutchan, and S. M. Hammer. 2008. The challenge of HIV-1 subtype diversity. N. Engl. J. Med. 358:1590-1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.UNAIDS. 2008. 2008 report on the global AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 39.Velazquez-Campoy, A., M. J. Todd, S. Vega, and E. Freire. 2001. Catalytic efficiency and vitality of HIV-1 proteases from African viral subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:6062-6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Velazquez-Campoy, A., S. Vega, E. Fleming, U. Bacha, Y. Sayed, H. W. Dirr, and E. Freire. 2003. Protease inhibition in African subtypes of HIV-1. AIDS Rev. 5:165-171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei, X., J. M. Decker, H. Liu, Z. Zhang, R. B. Arani, J. M. Kilby, M. S. Saag, X. Wu, G. M. Shaw, and J. C. Kappes. 2002. Emergence of resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in patients receiving fusion inhibitor (T-20) monotherapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1896-1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, Y. M., H. Imamichi, T. Imamichi, H. C. Lane, J. Falloon, M. B. Vasudevachari, and N. P. Salzman. 1997. Drug resistance during indinavir therapy is caused by mutations in the protease gene and in its Gag substrate cleavage sites. J. Virol. 71:6662-6670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]