Abstract

Type IV pili are virulence factors in various bacteria and mediate, among other functions, the colonization of diverse surfaces. Various subclasses of type IV pili have been identified, but information on pilus expression, biogenesis, and the associated phenotypes is sparse for the genus Yersinia. We recently described the identification of PypB as a transcriptional regulator in Yersinia enterocolitica. Here we show that the pypB gene is associated with the tad locus, a genomic island that is widespread among bacterial and archaeal species. The genetic linkage of pypB with the tad locus is conserved throughout the yersiniae but is not found among other bacteria carrying the tad locus. We show that the genes of the tad locus form an operon in Y. enterocolitica that is controlled by PypB and that pypB is part of this operon. The tad genes encode functions necessary for the biogenesis of the Flp subfamily of type IVb pili initially described for Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans to mediate a tight-adherence phenotype. In Y. enterocolitica, the Flp pilin protein shows some peculiarities in its amino acid sequence that imply similarities as well as differences compared to typical motifs found in the Flp subtype of type IVb pili. Flp is expressed and processed after PypB overproduction, resulting in microcolony formation but not in increased adherence to biotic or abiotic surfaces. Our data describe the transcriptional regulation of the tad type IVb pilus operon by PypB in Y. enterocolitica but fail to show most previously described phenotypes associated with this type of pilus in other bacteria.

Bacteria are able to colonize diverse biotic and abiotic surfaces. The attachment of a pathogenic bacterium to the surface of a eukaryotic cell is an important step for a successful infection and also the prerequisite for subsequent events like internalization or contact-dependent translocation of effector molecules by type III secretion systems. For interactions with surfaces, many bacteria make use of fimbrial or nonfimbrial adhesins (10). Fimbriae or pili are hair-like structures that extrude from the bacterial surface and usually consist of only one structural protein called pilin (29). Pili can be grouped by their morphological characteristics. Recently, however, they have been classified according to their biosyntheses. In Gram-negative bacteria one can distinguish chaperone-usher, curli, and type IV pili (T4P) (9), with T4P being the most abundant pili described so far. T4P are characterized as being 1- to 4-μm-long, flexible filaments with an average diameter of 5 to 8 nm. The functions of T4P are quite diverse. Besides mediating adhesion to and, in part, invasion into eukaryotic cells, they have been shown to play a role in microcolony and biofilm formation, twitching motility on surfaces, and the uptake of DNA by natural transformation. In addition, bacteriophages make use of pili as a receptor. The contact of pili with receptors on eukaryotic cells can result in the induction of signaling cascades. Therefore, it is not surprising that pili are essential virulence factors of many bacteria (6).

According to sequence similarities, T4P can be divided into type IVa (T4a) and type IVb (T4b) pili. The N-terminal signal sequence of the structural protein of T4a pili is relatively short and consists of only 5 to 6 amino acids (aa), while the signal sequence of T4b pilin contains 15 to 30 aa. Similarly, the mature T4a pilin is relatively short compared to the T4b pilin (ca. 150 aa versus 190 aa) (6, 29). Interestingly, genes encoding T4a pili are usually scattered throughout the genome and are widespread throughout the bacterial kingdom. In contrast, the distribution of T4b pili is restricted to enteropathogenic bacteria, including Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Salmonella enterica (6, 29).

Studies of the periodontitis-causing bacterium Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans revealed the presence of T4b pili with specific characteristics. These characteristics include a long leader peptide and a relatively short mature pilin of 50 to 80 aa. Due to its unique features, it has been described as the Flp subfamily of T4b pili (17). In A. actinomycetemcomitans, the Flp pili mediate unspecific attachment to surfaces and the formation of microcolonies and tenacious biofilms. Further analysis revealed that Flp pili can be found in a wide variety of bacterial and archaeal species encoded by the tad (tight adherence) locus that has spread via horizontal gene transfer (15, 31, 37).

The Gram-negative human pathogen Yersinia enterocolitica causes a variety of gastrointestinal syndromes. After uptake by the human host via contaminated food or water, Y. enterocolitica colonizes the intestine and crosses the epithelial barrier via M cells to reach the underlying lymphoid tissues, where the bacteria multiply extracellularly and, in rare cases, may spread to deeper tissues to cause a systemic disease (2). Besides Y. enterocolitica, two more Yersinia species are pathogenic for humans. While Y. pestis is transmitted via a flea bite and causes the devastating disease plague, Y. pseudotuberculosis is a gastrointestinal pathogen. All three species have a tropism for lymphatic tissues in common. Extracellular survival and replication in lymphoid tissues are made possible by the virulence plasmid-encoded type III secretion system that secretes antiphagocytic and anti-inflammatory effector proteins into host cells (5). Y. enterocolitica uses several adherence and invasion factors to colonize its host, including Inv, Ail, and the virulence plasmid-encoded protein YadA (8, 14, 25). While pili have been described to mediate surface attachment in many bacterial species, they are not well characterized for Yersinia. Y. enterocolitica possesses Myf fibrillae (similar to the pH 6 antigen of Y. pestis) that can be found on the bacterial surface by immunogold labeling, but the role in pathogenesis remains ill defined (13). Recent analyses identified a type IV pilus operon in Y. pseudotuberculosis that contributes to pathogenicity in the mouse model of infection. This pil operon is located on a genomic island termed YAPI (Yersinia adhesion pathogenicity island). A homolog of this island in Y. enterocolitica, but not Y. pestis, was also identified by in silico analysis (3, 4, 35).

In a previous analysis we identified three regulators, termed PypA, PypB, and PypC, in Y. enterocolitica that activate the transcription of the in vivo-expressed hreP gene, encoding a protease necessary for full virulence in the mouse model of yersiniosis (38). Analysis of the organization of the genomic locus around pypB revealed that it is located upstream of a putative operon homologous to the tad locus of A. actinomycetemcomitans. In this study we show that pypB is part of the tad operon and characterize the transcriptional regulation and expression of Flp pili in Y. enterocolitica.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. For routine growth, all strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or on agar plates at 26°C for Y. enterocolitica or 37°C for E. coli or as otherwise indicated. Antibiotics were used as described previously (38). For the induction of protein expression from the PBAD promoter, bacteria were grown in the presence of 0.1 to 0.2% (wt/vol) arabinose.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Y. enterocolitica | ||

| JB580v | ΔyenR (r− m+) Nalr; serogroup O:8 | 19 |

| GHY545 | JB580v Δflp | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80dΔ(lacZ)M15 Δ(argF-lac)U169 endA1 recA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+)deoR thi-1 supE44 gyrA96 relA1 | Gibco BRL |

| S17-1λpir | Tpr SmrrecA thi pro hsdR M+ RP4::2-Tc::Mu::Km Tn7λpir lysogen | 26 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEP185.2 | Camrmob+ (RP4) R6K ori (suicide vector) | 19 |

| pKW1 | Ampr Strep/Specr; low-copy-no. lacZYA reporter plasmid | 38 |

| pBAD18Kan | Kanr; PBAD expression vector | 11 |

| pBAD33 | Camr; PBAD expression vector | 11 |

| pWSK129 | Kanr; low-copy-no. cloning vector | 39 |

| pET-pypBΔc | PypBΔc expression vector | 38 |

| pEP-Δflp | Camr; flp deletion construct | This study |

| pKW-flp150 | flp-lacZYA transcriptional fusion containing 150 nt 5′ of flp start codon | This study |

| pKW-flp250 | flp-lacZYA transcriptional fusion containing 250 nt 5′ of flp start codon | This study |

| pKW-flp500 | flp-lacZYA transcriptional fusion containing 500 nt 5′ of flp start codon | This study |

| pKW-pypB126 | pypB-lacZYA transcriptional fusion containing 126 nt 5′ of pypB start codon | This study |

| pKW-pypB244 | pypB-lacZYA transcriptional fusion containing 244 nt 5′ of pypB start codon | This study |

| pKW-pypB500 | pypB-lacZYA transcriptional fusion containing 500 nt 5′ of pypB start codon | This study |

| pBAD-pypB | pypB in pBAD18Kan | 38 |

| pBAD33-pypB | pypB in pBAD33 | This study |

| pWSK-pypB/flpHA | pypB and flp under the control of their native promoters in pWSK129; expression of Flp with a C-terminal HA tag | This study |

| pWSK-kflp | pypB and flp under the control of their native promoters in pWSK129 | This study |

Construction of bacterial strains and plasmids.

Primers used for PCR amplification of DNA fragments are listed in Table 2. For the overproduction of PypB under the control of the PBAD promoter, we cloned the respective gene into pBAD33. For this purpose, plasmid pBAD-pypB (38) was digested with XbaI/PstI, and the pypB fragment (660 nucleotides [nt]) was isolated. Subsequent ligation into XbaI/PstI-digested pBAD33 resulted in plasmid pBAD33-pypB.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| JS-pypB126 | GCTCTAGACACGCACACAACATCAAAGAG | XbaI |

| JS-pypB244 | GCTCTAGACATCATGCAAGAATACGTCG | XbaI |

| JS-pypB1 | GCTCTAGAGCCGTTGCATCACTAAGACTG | XbaI |

| JS-pypB-200r | CGGAATTCTTCACTGACCGCTCCACGCTGTTCCTT | EcoRI |

| JS-pypB6 | CGGAATTCTTTAAACACAATCTCATTTGTCTC | EcoRI |

| GH-flp150f | GCTCTAGAAAAGGATTTTACAACCTGGAA | XbaI |

| GH-flp250f | GCTCTAGACAGTCTTAATCATGATTATCT | XbaI |

| GH-flp500f | GCTCTAGACGTTATACCGGGTCAGTGAGT | XbaI |

| SF-flp1-10 | GGAATTCTTGCGCATTAACTTGTGCTGTAAC | EcoRI |

| JS-flp-KpnI.for | GGGGTACCTATACCGGGTCAGTGAGTAAA | KpnI |

| JS-flp-XbaI.rev | GCTCTAGACCAATCAGGTGGAAATGAAAT | XbaI |

| JS-flp-XhoI.for | CCGCTCGAGATAATAGAAACTCATCTTCTC | XhoI |

| JS-flp-XhoI.rev | CCGCTCGAGAATTCTTTCCTTGTTAAATGT | XhoI |

| JS-pypB.for | GCTCTAGAGGCCTCACTATACCTCAAGCT | XbaI |

| JS-rcpA.rev | CGGGATCCCTTGTTTAGGATTAATTGCAT | BamHI |

| JS-flp1.rev | CGGAATTCTTATTTAACCATGTCTTTTAT | EcoRI |

| JS-flp1 | CGGAATTCAGTCCGTTATACCGGGTCAGTGAG | EcoRI |

| SF-flp1-RT1 | TTACGTTACAGCACAAGTTAATGCG | |

| SF-flp1-RT2 | ATGTTTGTCATGGATGTATCGACG | |

| JS-tadV1 | TAAGGCCAGCGCATTGATAGCGAT | |

| JS-tadV2 | TCTCTATACAGCGATGATGGGCGG | |

| JS-rcpC1 | GCTCGCGATTCAATTCGGTTGAGT | |

| JS-rcpC2 | CCACCATCGATGGCGAAGATGATA | |

| JS-rcpA1 | TCATAGTCTGCGATAGCTGCGGCA | |

| JS-rcpA2 | GTTCTTCCGCAATGCAGAGACACG | |

| JS-tadZ1 | TACACACCAACAATCTCGCGGGGT | |

| JS-tadZ2 | CGAGATAACCGGCAGGTAACTCGT | |

| JS-tadA1 | CGGCGAGAGGTTAAGGTTATCATC | |

| JS-tadA2 | ATTTAAACCCGCTAAAGAACGTGG | |

| JS-tadB1 | GTAAGATAACCATTCGTTAAGCGT | |

| JS-tadB2 | GATCCTATCACCATAGAGTCAATG | |

| JS-tadC1 | GACTGAACACAGGCAGCTGTTATA | |

| JS-tadC2 | CTGCAGCGCACTCCAATATAGTAT | |

| JS-tadD1 | GTGAGCTTCTGCACTATCAGGTGA | |

| JS-tadD2 | TGACCGCTACAGTGATGCCGTAAG | |

| JS-tadE1 | TTAGCAGTCTTGGTGGCCTCCGAA | |

| JS-tadE2 | AGATGATAACAACCTGGCACTCGC | |

| JS-tadF1 | TTACTCGCTCTCGAACGATCCCTG | |

| JS-tadF2 | ATGAGTGACTTATCACCCTATGGA | |

| JS-tadG1 | CGATGGTCAGTGCTAATGTTGCTT | |

| JS-flp.dig | TTTAACCATGTCTTTTATGTT | |

| JS flp2 | GCTCTAGATTAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTATTTAACCATGTCTTTTATGTTTGTCATGGATGTATC | XbaI |

| JS-alkB2.for | CCCGTCCAGCACGACGAAAGGTTA | |

| KR-cpxA1 | CCGCTCGAGATGCTGGAGCAACACATTGAG | XhoI |

| GH-cpx9 | GAAGATCTGCCCGATAAAGTTACGCACCAT | BglII |

Restriction sites are underlined.

For the construction of the Y. enterocolitica flp deletion strain (GHY545), we first amplified the flp gene, including approximately 500 nt upstream and downstream, by using primers JS-flpKpnI.for and JS-flpXbaI.rev and ligated the PCR fragment into suicide plasmid pEP185.2. The resulting plasmid was then used as a template in an inverse PCR using primers JS-flpXhoI.rev and JS-flpXhoI.for, thereby deleting the flp gene. After digestion with XhoI, the plasmid was religated and used to transform E. coli S17-1λpir to chloramphenicol resistance, resulting in plasmid pEP-Δflp. The plasmid was transferred into Y. enterocolitica by mating. Following analysis of proper chromosomal integration, cycloserine enrichment was used to identify Cams exintegrants with a deletion in the flp gene. Western blotting and PCR confirmed the correct genotype.

The construction of 3′ nested deletions of the flp and pypB promoter regions fused to lacZ was performed as follows. DNA fragments comprising the flp upstream region were amplified by PCR using GH-flp150f, GH-flp250f, and GH-flp500f as forward primers and SF-flp1-10 as the reverse primer, respectively, and ligated into XbaI/EcoRI-digested pKW1 to result in pKW-flp150, pKW-flp250, and pKW-flp500, respectively. The constructs contain 150, 250, or 500 bp, respectively, upstream of the ATG start codon and the first 50 bp of the flp coding region fused to the promoterless lacZYA genes. Similarly, DNA fragments comprising the pypB upstream region were amplified by PCR using JS-pypB1 as the forward primer and JS-pypB6 as the reverse primer, resulting in pKW-pypB500 (containing 500 bp upstream of the pypB ATG start codon and the first 27 bp of the coding region) or JS-pypB244 and JS-pypB126 as forward primers and JS-pypB-200 as the reverse primer, respectively, and ligated into XbaI/EcoRI-digested pKW1, resulting in pKW-pypB126 and pKW-pypB244, respectively (containing 244 or 126 bp upstream of the pypB ATG start codon, respectively, and the first 200 bp of the coding region).

To complement the flp deletion strain (GHY545), primers JS-pypB.for and JS-flp1.rev were used for PCR amplification of a 1.5-kb DNA fragment containing the pypB promoter region, pypB and flp. The PCR product was digested with XbaI and EcoRI and ligated into XbaI/EcoRI-digested pWSK129, resulting in plasmid pWSK-kflp.

To construct a C-terminally hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged version of the Flp protein, primers JS-pypB1 and JS-flp2 were used in a PCR to amplify the pypB and flp genes, including PpypB. The DNA sequence encoding the HA epitope was inserted via the reverse primer. The 1.5-kb PCR product was digested with XbaI and EcoRI and ligated into pWSK129, resulting in pWSK-pypB/flpHA.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

A culture of Y. enterocolitica carrying pBAD-pypB grown overnight was diluted 1:10 in fresh medium, and PypB expression was induced for 3 h with 0.2% (wt/vol) arabinose at 26°C. Total RNA was isolated by using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). Residual DNA contaminations were removed by digestion with DNase (Turbo DNA-free; Ambion). Subsequently, RNA was precipitated with 3 M sodium acetate and quantified by using a UV spectrophotometer at 260 nm.

The synthesis of cDNA was carried out by using avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) by random priming. The derived cDNA was used as a PCR template using the following primer pairs for the indicated gene junction: JS-flp1/SF-flp1-RT2 (pypB-flp), SF-flp1-RT1/JS-tadV1 (flp-tadV), JS-tadV2/JS-rcpC1 (tadV-rcpC), JS-rcpC2/JS-rcpA1 (rcpC-rcpA), JS-rcpA2/JS-tadZ1 (rcpA-tadZ), JS-tadZ2/JS-tadA1 (tadZ-tadA), JS-tadA2/JS-tadB1 (tadA-tadB), JS-tadB2/JS-tadC1 (tadB-tadC), JS-tadC2/JS-tadD1 (tadC-tadD), JS-tadD2/JS-tadE1 (tadD-tadE), JS-tadE2/JS-tadF1 (tadE-tadF), and JS-tadF2/JS-tadG1 (tadF-tadG). The cDNA was also used as a PCR template to detect the indicated longer transcripts by using primer pairs JS-flp1/JS-rcpC1 (pypB-flp-tadV-rcpC), JS-tadV2/JS-rcpA1 (tadV-rcpC-rcpA), JS-rcpA2/JS-tadA1 (rcpA-tadZ-tadA), JS-tadA2/JS-tadC1 (tadA-tadB-tadC), JS-tadC2/JS-tadE1 (tadC-tadD-tadE), and JS-tadE2/JS-tadG1 (tadE-tadF-tadG) to detect longer transcripts of the tad operon. As a negative control, primer pair JS-alkB2for/SF-flp1-RT2 was used, spanning a region upstream of pypB (in YE3631) to flp. As a further control, 1 μg of total RNA was used as a template. RT-PCR products were separated on 1% agarose gels.

Northern blot analysis.

For Northern blot analysis, total RNA (15 μg) was separated on a 2% formaldehyde-containing agarose gel. The RNA was transferred from the gel to a positively charged nylon membrane and UV cross-linked to the membrane. For hybridization and detection, we used the digoxigenin (DIG) labeling and detection system (Roche). After prehybridization, the blot was hybridized by using a 170-bp flp DNA fragment that was amplified by PCR using primers SF-flp1-RT1 and JS-flp.dig (DIG labeled at its 3′ end) (Table 2) according to the manufacturer's protocol (DIG Easy Hyb granules; Roche). Five hundred nanograms of the PCR product was used for hybridization at 50°C overnight. Subsequently, the membrane was washed and developed by using anti-DIG-alkaline phosphatase solution (1:15,000; Roche). Chemiluminescence was detected by using a Lumi Imager F1 (Roche).

β-Galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase assays of the lacZYA fusion strains were performed as previously described (38). Briefly, cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:20 in fresh medium and grown for 3 h with aeration at 26°C. The cultures were then collected by centrifugation at 4°C and washed in cold 0.85% (wt/vol) NaCl before enzyme activity assays were performed. β-Galactosidase enzyme activities are expressed in arbitrary units, which were determined according to a formula described previously by Miller (24). The reported values are the means and standard deviations of data from experiments that have been repeated at least three times, each in triplicate.

Production of antibodies directed against Flp.

For the production of a Flp-specific antiserum, a peptide containing the amino acids KTPLKEIVDTSMTNIKDMVK (corresponding to aa 20 to 39 of the mature Flp protein) (Fig. 1) was synthesized and conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The peptide was used to immunize rabbits according to standard procedures (Seqlab, Göttingen, Germany) to obtain polyclonal antiserum against Flp.

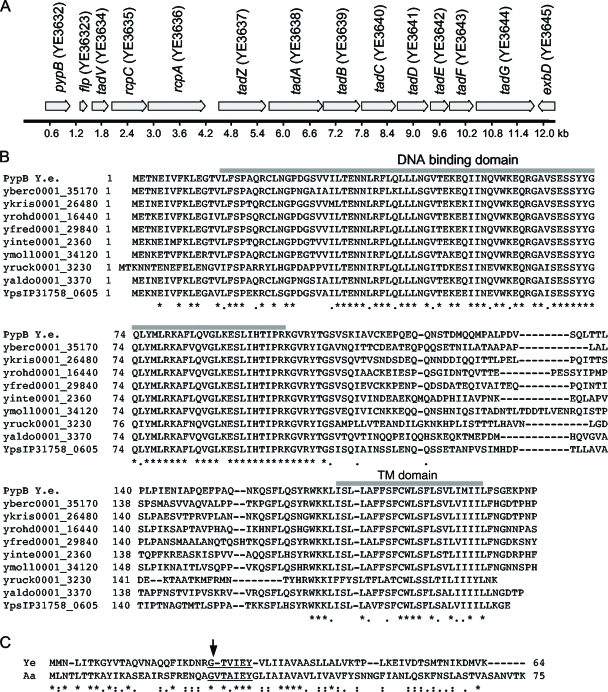

FIG. 1.

The pypB gene is part of the tad locus in Y. enterocolitica and encodes the PypB transmembrane transcriptional regulator that is conserved in yersiniae. (A) Genomic organization of the tad locus of Y. enterocolitica. Arrows indicate open reading frames and their directions of transcription. (B) Alignment of PypB of Y. enterocolitica with orthologs from other Yersinia species. The locus tags of the respective genes are indicated (yberc, Y. bercovieri; ykris, Y. kristensenii; yrohd, Y. rohdei; yfred, Y. frederiksenii; yinte, Y. intermedia; ymoll, Y. mollaretii; yruck, Y. ruckeri; yaldo, Y. aldovae; ypsIP31758, Y. pseudotuberculosis IPS31758). Gray bars above the sequence indicate the DNA binding domain and the transmembrane (TM) domain of PypB. (C) Alignment of the Flp protein of Y. enterocolitica (Ye) and Flp-1 of A. actinomycetemcomitans (Aa). The arrow indicates the predicted processing site. The conserved G/(X)4EY and G/(X)3EY motifs are underlined. An asterisk indicates identical residues in all sequences, a colon indicates conserved residues, and a full stop indicates semiconserved residues. Alignments have been generated by using the ClustalW algorithm (22).

Detection of Flp expression by immunoblotting.

To analyze Flp expression in Y. enterocolitica, the wild type, the Δflp strain (GHY545), and the complemented Δflp strain (GHY545 carrying pWSK-kflp), each carrying pBAD33-pypB to overproduce PypB, were grown overnight at 26°C. The next day, the strains were diluted 1:10 in fresh LB medium containing 0.1% arabinose to induce the expression of the PypB protein and grown for 5 h at 26°C. For the preparation of bacterial supernatants, cultures normalized to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 were centrifuged three times at 4°C at 3,500 × g. Between each centrifugation the supernatant was carefully removed and transferred into a fresh microcentrifuge tube, leaving a residual volume behind, to avoid contamination of the supernatant fraction with bacteria. After the addition of 4× protein loading buffer, 20 μl of supernatant was boiled and separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). To analyze whole cells, bacteria normalized to an OD600 of 0.25 (corresponding to approximately 1.2 × 106 bacteria) were resuspended in 4× protein loading buffer, boiled, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose by Western blotting, blocked with 5% (wt/vol) milk powder, and incubated with Flp antiserum (1:5,000) and goat anti-rabbit peroxidase (PO)-coupled secondary antibody (1:5,000; Dianova). As a control for the contamination of the bacterial supernatants with cytoplasmatic proteins, streptavidin-PO (1:5,000; Roche) was used to detect the cytoplasmatic acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) carboxylase biotin carboxyl carrier protein (YE3811; AccB).

To analyze Flp-HA expression in Y. enterocolitica and in E. coli DH5α, strains containing plasmids pBAD33-pypB and pWSK-pypB/flpHA were grown overnight at 26°C and 37°C, respectively. The next day, the strains were diluted 1:10 in fresh LB medium containing 0.1% arabinose to induce the expression of the PypB protein from PBAD and grown for 5 h at 26°C or 37°C, respectively. Bacteria normalized to an OD600 of 0.25 (corresponding to approximately 1.2 × 106 bacteria) were resuspended in 4× protein loading buffer, boiled, and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane by Western blotting. The membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) milk powder in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), washed with PBS, and incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-HA tag antibody (1:1,000; Cell Signaling) and goat anti-mouse PO-coupled secondary antibody (1:5,000; Dianova). Bound antibodies were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Pierce) using a Lumi Imager F1 (Roche).

EMSA.

For the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), we employed purified C-terminally His-tagged PypBΔc in elution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 250 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100) that was affinity purified as described elsewhere previously (38). As probes, we employed a PCR fragment encompassing 250 bp upstream of the flp ATG start codon and the first 50 bp of the flp coding region (primer pair GH-flp250f/SF-flp1-10) or a PCR fragment encompassing 500 bp upstream of the pypB ATG start codon and 27 bp of the pypB coding region (primer pair JS-pypB500/SS-pypB6). For the binding reaction, 3 ng of the respective DIG-labeled PCR product (DIG gel shift kit, second generation; Roche) was incubated at room temperature for 45 min with different amounts of PypBΔc. To test the specificity of the protein-DNA interaction, we used specific (unlabeled PCR fragment used as a probe) and unspecific (200-bp PCR fragment generated using primers KR-cpxA1 and GH-cpx9, encompassing an internal fragment of the Y. enterocolitica cpxA gene) unlabeled competitor DNA. For the pypB EMSA, competitor DNA was used in a 300-fold excess. For the flp EMSA, competitor DNA was used in a 500-fold excess. After the binding reaction, the samples were separated on a 6% native polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane by electroblotting. For detection by chemiluminescence we employed an anti-DIG-AP-coupled antibody (1:15,000; Roche) and a Lumi Imager F1 (Roche).

Biofilm assays.

For biofilm assays, cultures of Y. enterocolitica wild-type and Δflp strains grown overnight, both containing pBAD-pypB but lacking virulence plasmid pYV, were diluted 1:20 in fresh LB medium containing 0.1% arabinose or glucose for the induction or repression of PypB expression and grown in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) 96-well microtiter plates for different time periods (3 h to 50 h) at 26°C or 37°C. Subsequently, the supernatants were discarded, and the 96-well plates were washed three times with double-distilled water (ddH2O). After incubation with 1% crystal violet for 15 min, the plates were again washed three times with ddH2O. To solubilize the crystal violet, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added for 60 min, and the degree of staining was quantified at a wavelength of 590 nm. Uninoculated wells were used as a blank and subtracted from each value. Alternatively, bacteria were grown overnight in LB medium lacking NaCl and subcultured in PVC 96-well microtiter plates in M63 minimal medium as described previously by Kim et al. (18).

Microcolony formation.

Cultures of the Y. enterocolitica wild type and Y. enterocolitica Δflp strains carrying pBAD-pypB grown overnight at 26°C in LB medium were diluted 1:20 in fresh LB medium containing 0.1% or 0.2% arabinose to induce PypB expression from the PBAD promoter in microtiter plates for 24 h to 48 h at 26°C. Microcolony formation was detected by light microscopy.

Immunofluorescence analysis.

For immunofluorescence analysis, the Y. enterocolitica wild type, the Δflp strain (GHY545), and the complemented Δflp strain (GHY545 carrying pWSK-kflp), all carrying pBAD33-pypB, were grown overnight at 26°C. The next day, strains were diluted 1:10 in LB medium containing 0.1% arabinose and grown for 5 h to induce PypB expression from the PBAD promoter. Subsequently, bacteria were washed with Dulbecco's PBS, fixed with 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA), and incubated with 50 mM NH4Cl. After blocking unspecific binding sites by incubation with 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), Flp-specific antiserum (1:200) was added, and incubation was continued overnight at 4°C. After washing the cells several times with PBS, secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit Cy3, 1:200; Dianova) was added for 1 h at room temperature. DNA was stained with DRAQ5 (Biostatus Limited). Bacteria were then transferred onto a microscope slide, mounted with fluorescence mounting medium (Dako Cytomation), and analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (Axiovert 200 M).

Determination of cell-associated bacteria.

To determine the numbers of bacteria associated with eukaryotic cells, the Y. enterocolitica wild type, the Δflp strain (GHY545), and the complemented Δflp strain (GHY545 carrying pWSK-kflp), all carrying pBAD33-pypB but lacking the pYV virulence plasmid, were grown as described above. HeLa, CHO-K1, and Caco-2 cells were infected with 10 μl of bacterial suspension for 1 to 3 h, washed three times with PBS, and lysed with PBS containing 1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. The percentage of cell-associated bacteria was determined by plating appropriate dilutions onto LB agar and compared to the initial inoculum used for infection.

Electron microscopy.

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), cultures of the Y. enterocolitica wild-type and Δflp (GHY545) strains carrying pBAD-pypB grown overnight were diluted 1:20 in LB medium containing 0.1% (wt/vol) arabinose to induce PypB expression from the PBAD promoter for 3 h at 26°C. Bacteria were negatively contrasted with 1% (wt/vol) phosphotungstic acid and applied onto formvar-coated copper grids. The samples were analyzed by using a Tecnai G2 Spirit Twin electron microscope (Fei).

For ultracryo-electron microscopy, cultures of the Y. enterocolitica wild type, the Δflp strain (GHY545), and the complemented Δflp strain (GHY545 carrying pWSK-kflp), all carrying pBAD33-pypB, grown overnight were diluted 1:20, and the expression of PypB was induced with 0.1% (wt/vol) arabinose for 3 h at 26°C. Cells were fixed with 2% (wt/vol) PFA and 2% (wt/vol) glutaraldehyde in D-PBS (pH 7.4). Ultrathin frozen sections were prepared by the Tokayasu method (34a) (70-nm samples), immunostained using gold-coupled Flp antiserum, and observed by electron microscopy (Tecnai Spirit Twin; Fei).

RESULTS

The tad locus of Y. enterocolitica.

In a previous analysis we showed that PypB is a transmembrane transcriptional regulator similar to ToxR of Vibrio cholerae and CadC of E. coli (38). Characteristic for this class of transcriptional regulators is a cytoplasmatic OmpR-like winged helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif that is separated from a carboxy-terminal periplasmatic domain by a transmembrane domain. In PypB, this periplasmatic domain is unusually short (∼9 aa, compared to 95 aa in ToxR of V. cholerae). Analysis of the genomic localization of pypB revealed that it is located on the YGI-1 genomic island of Y. enterocolitica (Fig. 1A) (35). This island harbors genes with similarity to tad loci, carrying genes for the biogenesis of the Flp subfamily of T4b pili. Further analysis of completed and unfinished genomes revealed that this locus is conserved throughout the yersiniae but, as reported previously by Thomson et al. (35), is inactivated in Y. pestis. Interestingly, analysis of available genome sequences revealed that all YGI-1 homologs in Yersinia show some specific characteristics. First, they are all inserted at the same genomic locus 5′ of the exbD gene. Second, in contrast to most tad loci described so far, it contains only one instead of two flp genes. Third, all tad loci are associated with a gene at their 5′ end coding for a transcriptional regulator homologous to PypB.

Although the tad locus is widespread among bacteria and archaea, an association with a transmembrane transcriptional regulator has so far not been described. Analysis of available completed as well as unfinished prokaryotic genomes using the BLAST algorithm did not reveal a similar association of the tad locus with a transcriptional regulator besides the genus Yersinia, with one exception. We identified a transcriptional regulator similar to PypB in the genome of Shigella flexneri 2A strain 301. In this strain, SF3009 is 41% identical at the protein level to PypB of Y. enterocolitica. Similar to the genomic organization in Y. enterocolitica, an flp gene (SF3008) and a tadV gene (SF3007) are immediately downstream of SF3009. However, additional genes of the tad locus are not present. Instead, the genes SF3007 to SF3009 are flanked by genes encoding insertion sequence (IS) elements and transposases, indicating a mobile genetic element. As shown in Fig. 1, homologs of Y. enterocolitica PypB are conserved between pathogenic as well as nonpathogenic Yersinia strains. The level of similarity is high in the DNA binding as well as the transmembrane domains of PypB, while the region of the PypB sequence linking both domains is relatively variable (Fig. 1B). A conserved DNA binding domain suggests that similar promoter regions are recognized in all species, while the conservation of the transmembrane domain might be an indication for a role in signal perception.

A comparison of tad loci in different genomes revealed that probably not all genes are essential for functionality in all prokaryotes. RcpA, RcpB, and TadD are predicted outer membrane proteins not found in Gram-positive bacteria due to a lack of an outer membrane (37). Most genes of the tad locus from A. actinomycetemcomitans can be identified in the same genetic organization in the genome of Y. enterocolitica with the exception of rcpB (35). The rcpB gene has so far been identified only in tad loci of the Pasteurellaceae and encodes an outer membrane protein (30). A specific feature of the tad locus of Yersinia is related to the Flp structural protein. As mentioned above, the tad locus of A. actinomycetemcomitans encodes a pilus with specific characteristics. These characteristics include a long leader peptide and a relatively short mature pilin. Processing occurs by the TadV prepilin peptidase after a Gly residue in the conserved G/(X4)EY processing site (the slash indicates the processing site) (17, 36). In addition, a shared “Flp motif” has been identified at the amino terminus of the mature pilin that is characterized by adjacent Glu and Tyr residues within a stretch of approximately 20 hydrophobic, nonpolar, aliphatic amino acids. In addition, most predicted Flp proteins contain a conserved phenylalanine residue toward their C terminus (16, 17). All predicted Flp proteins of the yersiniae show differences in these features that are conserved in the genus Yersinia. Besides the missing conserved Phe in the C terminus, the N terminus of the mature Y. enterocolitica Flp protein shows a different sequence at the putative prepilin peptidase cleavage site, which is G/(X3)EY. Therefore, the Glu of the mature pilin is located at position 4 in the Y. enterocolitica processed Flp protein instead of position 5 in other T4P (Fig. 1C). An alignment with Flp-1 of A. actinomycetemcomitans suggests that the conserved N-terminal residue of the mature pilin, which is usually Val, Met, or Leu in typical T4b pili, has been omitted, to result in Thr as the N-terminal amino acid in the mature Yersinia Flp protein (Fig. 1C) (6). However, the putative pseudopilins TadE and TadF of Yersinia, which are presumably also processed by the TadV prepilin peptidase as in A. actinomycetemcomitans (36), have a consensus cleavage site [G/(X4)EY] of T4b pili (data not shown).

PypB overproduction results in flp transcription.

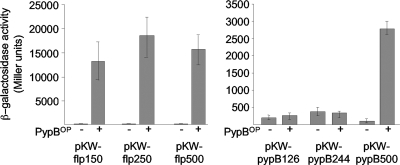

In previous analyses we have shown that pypB is autoregulated and regulated by PypC (38). As pypB is associated with the tad locus in yersiniae, we hypothesized that PypB might be involved in the transcriptional regulation of the tad locus. To analyze if a promoter exists upstream of flp and if PypB activates this promoter, we constructed a transcriptional fusion of the flp 5′ region with the lacZ gene as a reporter. To avoid potential readthrough from the promoter upstream of pypB, we did not construct a strain with a reporter homologously integrated into the chromosome of Y. enterocolitica but instead used the episomal β-galactosidase reporter plasmid pKW-flp500. The plasmid contains approximately 500 nt 5′ of the ATG start codon of the flp gene. In this reporter construct, the transcription of lacZ is independent of PpypB and depends only on a putative promoter upstream of flp. The overproduction of PypB from a PBAD promoter in this strain resulted in a strong increase in β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 2). Similar results can be obtained when reporter plasmid pKW-pypB500 is used, containing 500 bp 5′ of the pypB ATG start codon fused to lacZ, to monitor pypB transcription, confirming previous results with a chromosomal pypB-lacZ fusion (38). To identify regions at the pypB and flp promoter that might be necessary for activation by PypB, we constructed transcriptional fusions with lacZ containing fragments of the pypB or flp promoter region deleted from the 5′ end. As shown in Fig. 2, a region between 250 and 500 nt 5′ of the ATG start codon of pypB and 150 nt upstream of the start codon of flp, respectively, are required for transcriptional activation by PypB. From these data we conclude that PypB is a positive transcriptional regulator of the pypB gene as well as the flp gene of Y. enterocolitica and that a PypB-responsive promoter exists upstream of the flp gene.

FIG. 2.

PypB activates transcription of flp and pypB. Y. enterocolitica cultures containing the indicated flp-lacZ or pypB-lacZ reporter plasmids and either pBAD18Kan (−) as a control or pBAD-pypB (+) to induce PypB overproduction (PypBOP) from the PBAD promoter were grown in the presence of 0.2% arabinose for 3 h at 26°C before determinations of β-galactosidase activity (in arbitrary Miller units). Data are means and standard deviations of data from at least three experiments, each performed in triplicate. One hundred fifty nucleotides upstream of the flp ATG start codon are sufficient for flp activation by PypB, while nt 245 to 500 upstream of the ATG start codon of pypB are necessary for pypB activation by PypB.

The tad locus of Y. enterocolitica is organized as an operon including pypB.

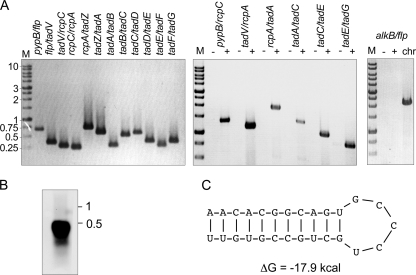

The analysis of tad loci in other bacteria revealed that it is organized as an operon (12, 27). Our data indicate that promoters exist upstream of pypB and of flp in Y. enterocolitica. Transcription from these promoters might result in mono- and/or polycistronic transcripts. To study this in more detail, total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA and used as a template for PCR (RT-PCR). The primers were designed to bind in the 3′ region of a gene and the 5′ region of the adjacent gene so that a PCR product would result only when the genes are cotranscribed. As shown in Fig. 3A, we obtained PCR products in all cases, indicating that all genes of the tad locus, including pypB, are cotranscribed into a polycistronic mRNA. PCR products could also be obtained for larger transcripts, including the pypB-flp-tadV-rcpC, tadV-rcpC-rcpA, rcpA-tadZ-tadA, tadA-tadB-tadC, tadC-tadD-tadE, and tadE-tadF-tadG regions (Fig. 3). In contrast, PCR products could not be obtained when total RNA was used as a template or when a primer pair spanning a region upstream of pypB (in YE3631) to flp was used (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional analysis of the tad locus. (A) RT-PCR analysis of the tad locus using primers binding in the 3′ region of a gene and the 5′ region of the adjacent gene or a gene further downstream so that the transition region between genes as indicated in the figure is amplified. −, RNA as a template; +, cDNA as a template; chr, chromosomal DNA of Y. enterocolitica as a template. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from PypB-overproducing Y. enterocolitica that was probed with an flp fragment reveals an flp transcript with an approximate size of 400 nt. (C) Stem-loop structure in the flp-tadV intergenic region predicted by Mfold (40).

In A. actinomycetemcomitans a monocistronic transcript that corresponds to the flp gene has been identified (20). To analyze if a transcriptional terminator might exist downstream of flp, we performed a Northern blot analysis using an flp-specific probe. As shown in Fig. 3B, we were able to detect a transcript with a size of approximately 400 nt. The size of this fragment corresponds well with a monocistronic flp transcript starting from Pflp, indicating a transcriptional terminator downstream of the flp gene as described previously for A. actinomycetemcomitans (20). Indeed, we identified a putative stem-loop structure in the intergenic flp-tadV region that resembles classical terminators and has a calculated ΔG of −17.9 kcal (Fig. 3C). Similar to A. actinomycetemcomitans, larger transcripts could not be identified by Northern blotting, indicating that they are transcribed only in small amounts or are unstable.

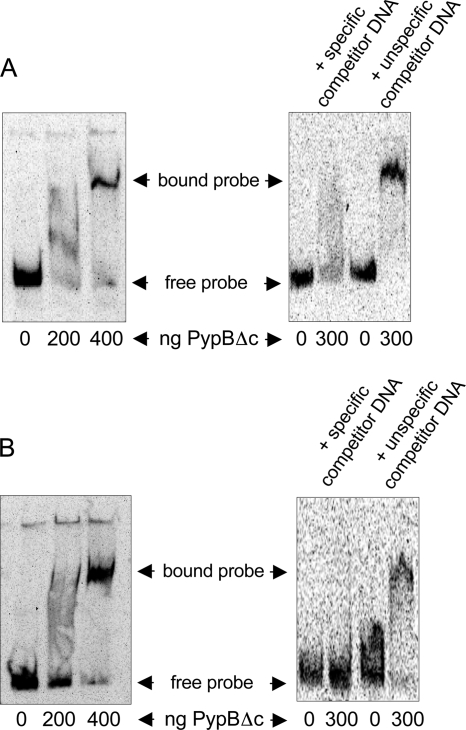

PypB directly interacts with the pypB and the flp promoter regions.

In a previous study we showed that PypB is able to activate and interact directly with the hreP promoter (38). To show that the effect of PypB overproduction on pypB and flp activation is also direct, we performed electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs). For this purpose we employed a recombinant version of PypB that is lacking its C-terminal membrane domain (PypBΔc) but has an intact winged helix-turn-helix motif necessary for DNA interactions (38). To analyze if this protein is able to activate pypB and flp, we introduced a plasmid to express PypBΔc, including a C-terminal six-His tag from the PBAD promoter in E. coli carrying reporter plasmid pKW-flp250 or pKW-pypB500, respectively, and determined the β-galactosidase activity. The overproduction of PypBΔc resulted in a level of activation of gene expression comparable to that observed for wild-type PypB (for pypB-lacZ, 38 ± 8 Miller units for the control and 891 ± 341 Miller units for PypBΔc overproduction; for flp-lacZ, 196 ± 165 Miller units for the control and 9,820 ± 5,252 Miller units for PypBΔc overproduction), indicating that the membrane localization of PypB is not required for the activation of flp and pypB.

For EMSAs, recombinant PypBΔc was incubated with DIG-labeled DNA fragments encompassing 500 nt upstream of the pypB start codon or 250 bp upstream of the flp start codon, respectively. Both fragments have been shown to contain regions responsive to PypB (Fig. 2). Increasing amounts of PypBΔc result in a mobility shift of the pypB probe as well as of the flp probe (Fig. 4). The shift can be blocked by the addition of an excess of specific competitor DNA (unlabeled promoter fragment of pypB or flp, respectively). In contrast, the addition of an excess of unspecific competitor DNA (an internal fragment of the Y. enterocolitica cpxA gene) had no effect on the DNA mobility shift. From these data we conclude that PypB is able to bind directly and specifically to the pypB and the flp promoters, resulting in transcriptional activation. Sequence similarities indicative of a PypB binding site could not be identified in the pypB, flp, and hreP promoter regions.

FIG. 4.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrate a direct interaction of PypB with the pypB and flp promoter region. Increasing amounts of recombinant PypBΔc were incubated with a DIG-labeled DNA fragment encompassing 500 nt upstream of the pypB start codon (A) and 250 bp upstream of the flp start codon (B), resulting in a mobility shift of the DNA fragment. Shifting of the probe can be inhibited by specific but not by unspecific unlabeled competitor DNA.

Flp is expressed and processed after PypB overproduction.

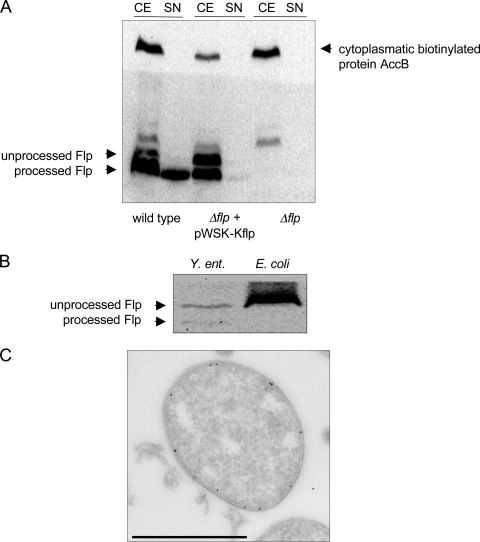

Our data indicate that PypB activates the transcription of promoters upstream of pypB and flp, thereby activating the whole tad locus. To analyze if the Tad locus is expressed after PypB overproduction, we used Western blotting to detect Flp in Y. enterocolitica. Whole-cell fractions as well as supernatants of Y. enterocolitica strains carrying PBAD-pypB plasmids grown in the presence of arabinose were separated by SDS-PAGE and subsequently processed for Western blotting using Flp-specific peptide antiserum. As shown in Fig. 5A, Flp is expressed in the Y. enterocolitica wild type but not in a strain deleted for the flp gene. Two bands with apparent molecular masses of 4 and 6 kDa specifically reacting with Flp antiserum can be detected in whole-cell lysates (calculated molecular masses of 7 kDa for full-length Flp and 4.2 kDa for processed Flp, respectively). Only the 4-kDa band appears in the supernatant, indicating that Flp is processed and that the 4-kDa protein represents mature Flp that is secreted most likely by the tad-encoded secretion system. When complementing the Δflp deletion from a plasmid, both the 4-kDa as well as the 6-kDa proteins missing in the mutant strain appeared in whole-cell lysates, indicating that they correspond to Flp. The complemented Δflp strain also secreted Flp into the supernatant although in smaller amounts than those of the wild type. As a control for cytoplasmatic contamination of the supernatants, streptavidin-PO was used to detect the cytoplasmatic acetyl-CoA carboxylase biotin carboxyl carrier protein. The protein could be detected only in whole-cell lysates, indicating that cytoplasmatic proteins do not contaminate the supernatants. As a further control we expressed an HA-tagged version of Flp from a plasmid in E. coli. While Flp-HA is expressed in E. coli and in Y. enterocolitica, it is processed only in Y. enterocolitica, indicating that the processing of Flp occurs by a Y. enterocolitica-specific peptidase, presumably TadV (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Flp is secreted and processed by Y. enterocolitica. (A) Whole-cell extracts (CE) and supernatants (SN) of the Y. enterocolitica wild type, the Δflp strain, and the complemented Δflp strain and overproducing PypB from pBAD33-pypB were analyzed by Western blotting using Flp-specific antiserum. The upper part of the blot was probed with streptavidin-PO to detect the cytoplasmatic acetyl-CoA carboxylase biotin carboxyl carrier protein (AccB) to exclude contamination of supernatants with cytoplasmatic proteins. (B) Whole-cell extracts of the Y. enterocolitica wild type and E. coli DH5α carrying pWSK-pypB/flpHA and pBAD33-pypB to overproduce PypB were analyzed by Western blotting with HA-specific antibody to detect Flp-HA. Flp-HA is expressed in both strains but is processed only in Y. enterocolitica. (C) Ultracryo-electron microscopy of Y. enterocolitica overproducing PypB indicates that Flp is expressed and transported to the bacterial inner membrane. Flp was detected by using gold-labeled Flp antiserum (bar, 1 μm).

As the processing of prepilins by their cognate prepilin peptidase occurs at the cytoplasmatic membrane (21, 34), we analyzed whether we can detect Flp associated with the inner membrane of Y. enterocolitica by cryo-electron microscopy. Indeed, using a Flp-specific gold-labeled antibody, we found Flp at the inner membrane of PypB-overproducing wild-type but not Δflp bacteria (Fig. 5C and data not shown). We conclude that Flp is expressed in PypB-overproducing Y. enterocolitica, processed by a prepilin peptidase missing in E. coli DH5α, and subsequently transported through the bacterial outer membrane.

Phenotypic characterization of the Y. enterocolitica tad locus.

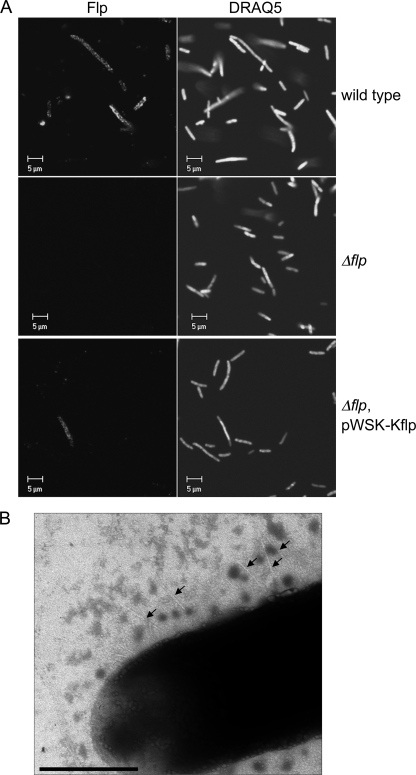

The tad locus has been shown to encode a type IVb pilus that is implicated in the formation of biofilms and microcolonies and adherence to eukaryotic cells in A. actinomycetemcomitans, Haemophilus ducreyi, as well as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7, 15-17, 27). As we showed that the tad locus is expressed in Y. enterocolitica after PypB overproduction, we were interested in analyzing if it mediates similar phenotypes. As an initial attempt to analyze whether Flp is not only expressed but also assembled into pili, we tried to detect Flp pili on the surface of Y. enterocolitica by immunofluorescence microscopy. The wild type and the Δflp mutant strain as well as a complemented Δflp strain were grown for 5 h at 26°C in the presence of 0.1% arabinose to induce PypB expression from the PBAD promoter. Cells were incubated with Flp-specific peptide antibody and Cy3-labeled secondary antibody and analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy. As shown in Fig. 6A, only a fraction of the wild-type bacteria were expressing Flp at their surface, while no signal could be detected for the Δflp mutant, indicating the specificity of the antiserum for Flp. The signals obtained for Flp are distributed in a patchy pattern on the bacterial surface. Similar Flp signals were observed for the complemented Δflp strain; however, only a fraction of all cells showed Flp expression. This finding is in agreement with data obtained by Western blotting, which revealed only weak secretion of Flp in the complemented Δflp mutant strain (Fig. 5A). To follow up on these results, we analyzed the bacteria by negative-contrasting transmission electron microscopy. We were able to detect thin pilus-like structures on the bacterial surface of wild-type but not Δflp bacteria, indicating that they might represent Flp pili (Fig. 6B). However, only a very small fraction of all analyzed bacteria were found to carry these pili. As subsequent transmission electron microscopy coupled with immunogold labeling did not result in the detection of gold-labeled pili or any other specific signal associated with the bacterial surface, even after several attempts (data not shown), we cannot unequivocally state that the observed structures are indeed Flp pili. Our results indicate either that the amount of pili expressed is too low to be detected or that the Flp protein is not assembled into a functional pilus. We also cannot exclude the possibility that the Flp pili are instable and disassemble during processing for electron microscopy.

FIG. 6.

Flp is associated with the bacterial surface. (A) Confocal fluorescence microscopy indicates that Flp is expressed by and transported to the surface of the PypB-overproducing Y. enterocolitica wild type and the complemented Δflp mutant strain but not by the Δflp mutant. Flp was detected by using Flp-specific antiserum and a Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (left), and DNA was stained with DRAQ5 (right). (B) TEM of a negative-contrasted sample indicates the presence of short pili (arrows) on the surface of the wild-type strain overproducing PypB (bar, 0.5 μm).

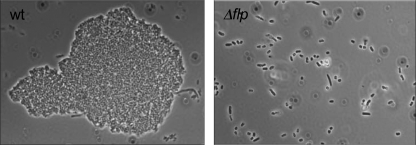

Next, we determined if the tad locus of Y. enterocolitica is associated with microcolony formation. Wild-type and Δflp bacteria were grown in 96-well plates at 26°C in the presence of 0.1% arabinose to induce PypB overproduction from PBAD. After 24 h, small bacterial aggregates were visible in the wild-type culture but not in the Δflp mutant strain. After prolonged growth (up to 50 h), we detected larger microcolonies that are dependent on the presence of the flp gene, similar to what was described previously for other bacteria (Fig. 7) (16).

FIG. 7.

Microcolony formation of PypB-overproducing Y. enterocolitica depends on Flp. Wild-type (wt) bacteria cultured in microtiter plates for 48 h at 26°C and expressing PypB from the PBAD promoter form microcolonies, while the Δflp mutant strain does not.

To determine whether the tad locus is also involved in the attachment of Y. enterocolitica to plastic surfaces and biofilm formation, we grew pYV-cured wild-type and Δflp bacteria overproducing PypB from PBAD at 26°C and 37°C in 96-well plates for various time points. After the removal of the growth medium and washing away of unbound bacteria, attached cells were stained with crystal violet and quantified. However, we were not able to detect any significant difference in the attachment of bacteria to plastic surfaces (data not shown). In addition, we analyzed whether the expression of Flp contributes to the binding of Y. enterocolitica to cultured eukaryotic cell lines. To this end, we infected HeLa, CHO-K1, and Caco-2 cells with wild-type bacteria, the Δflp strain, or the complemented Δflp strain, each overproducing PypB, for various times (1 h to 3 h) and determined the amount of cell-associated bacteria. As we expected that the well-described invasion factors Inv and the pYV-encoded YadA might mask our results, we also performed the experiments with inv-negative and pYV-cured strains. However, although in some experiments, the presence of Flp seemed to positively affect the number of cell-associated bacteria, the values that we obtained were highly variable. Even after several attempts, also by directly counting cell-associated bacteria by microscopic examination, we were not able to detect a significant difference in cell adhesion dependent on the flp gene (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

T4P mediate phenotypes associated with bacterial surface interactions and have been described to be virulence factors in various bacteria (6). The expression of pili by pathogens has to be tightly regulated, especially during an infection, as pili not only are important for colonization but also are antigens that can be recognized by the immune system of the host. Pili have been identified previously in the genus Yersinia, but T4P in Y. enterocolitica have not been characterized (3, 4, 13). Here we describe the transcriptional activation of the tad operon, encoding Flp T4b pili of the human pathogen Y. enterocolitica, by the transcriptional regulator PypB. The pypB gene is part of the tad operon, a genetic organization that is specific for yersiniae. PypB activates the transcription of the tad locus by binding to promoter regions upstream of pypB as well as flp, resulting in the expression, processing, and secretion of the Flp pilin protein. Although we describe Flp-dependent microcolony formation, other typically tad-associated phenotypes such as biofilm formation and host cell attachment could not be detected for the Flp pili of Y. enterocolitica.

In previous studies we showed that PypB acts as a transcriptional regulator of hreP, pypC, and pypB (38). A closer examination of the pypB locus revealed that pypB is associated with the tad locus that has been identified for diverse bacteria but is best characterized so far for A. actinomycetemcomitans (16, 37). Although many bacterial species carry the tad locus, it has never been shown to be associated with a transmembrane transcriptional regulator similar to PypB. However, analysis of genome sequences of the genus Yersinia available so far revealed that they all possess the tad locus associated with the pypB gene at their 5′ end, indicating that yersiniae have evolved to employ PypB as a regulator activating the tad locus in response to specific environmental conditions. Similar to what was described previously for Y. enterocolitica (38), PypB might be involved in coordinating the expression of other genes in other Yersinia species. Interestingly, pypC and its homolog, pclR, encode transcriptional regulators that are associated with type II secretion system gene clusters in yersiniae, indicating a common theme of activating the transcription of molecular export machines by associated regulators (32).

P. aeruginosa has also been shown to possess an flp-tad-rcp gene cluster. Its transcriptional activation is controlled by a genetically linked two-component regulatory system (1). However, the genetic organization of the locus is different from that in Y. enterocolitica or A. actinomycetemcomitans, as the cluster is composed of five independent transcriptional units (1).

PypB activates the transcription of the tad locus by directly binding at regulatory regions upstream of pypB as well as flp. The genes of the tad locus are organized in one large transcriptional unit, and our Northern blot experiments furthermore reveal a shorter flp-carrying transcript, indicating a transcriptional terminator 3′ of the flp gene. This finding is similar to what was described previously for A. actinomycetemcomitans and, to a certain extent, H. ducreyi (20, 27), with the exception that in Y. enterocolitica, the pypB gene is part of the operon but is missing in other species outside the genus Yersinia.

Besides the association of the tad locus with a transcriptional regulator, there are further peculiarities associated with the Flp pilin protein. Kachlany et al. previously described that the tad locus of A. actinomycetemcomitans encodes a subtype of T4b pili that has specific characteristics (17). The tad locus of Y. enterocolitica, however, is again different. First, there is only one flp gene instead of two in most other tad loci; second, the mature Flp of Y. enterocolitica is unusually short (only 39 aa); third, Flp is missing a conserved Phe residue in its hydrophilic C-terminal part; and fourth, the conserved amino acids Glu and Tyr usually found in the hydrophobic N terminus at positions 5 and 6 of the mature pilin are shifted to positions 4 and 5, respectively (Fig. 1C). These characteristics are conserved throughout the Flp proteins of yersiniae. Interestingly, the pseudopilins TadE and TadF are presumably also processed by the TadV prepilin peptidase, and the amino acids at positions 5 and 6 (Glu-Phe) in the mature pseudopilins are also conserved in Y. enterocolitica (36). Obviously, the unusual features of the Flp protein do not interfere with processing. All T4b pili are processed by prepilin peptidase after a Gly residue that is also conserved in the Flp pili and the TadE/TadF pseudopilins of yersiniae. Whether processing indeed occurs by the TadV prepilin peptidase, or by another so-far-not-identified enzyme, has to be elucidated in the future. At least, we did not detect Flp processing in E. coli DH5α, where the TadV peptidase is absent.

We clearly demonstrate that the transcriptional activation of the tad locus after PypB overproduction results in the expression and secretion of Flp; however, the associated phenotypes are different from what we expected. Although we detected microcolony formation dependent on Flp, we did not observe a characteristic biofilm or adhesion to eukaryotic cells. Also, we were not able to detect Flp pili by TEM after immunogold labeling, so we cannot say with certainty that the pilus-like structures detected on the Y. enterocolitica surface after negative-contrasting TEM are indeed Flp pili. Similar observations were previously made for H. ducreyi: although the tad genes are expressed and mediate microcolony formation, no Flp pili could be detected on the bacterial surface (27). In contrast, however, we localized Flp after cryo-immunoelectron microscopy at the bacterial inner membrane and also detected Flp-specific signals at the bacterial surface by immunofluorescence microscopy. Our findings might be explained by the specific characteristics of the Y. enterocolitica Flp protein. As it was suggested previously that the N-terminal amino acids of the mature pilin (the Glu-Tyr motif) (see above) are especially important for the proper assembly of pilin subunits into a pilus (23, 28, 33), this might be a reason why we were not able to clearly demonstrate pilus assembly by (immunogold labeling) TEM. However, as we detected Flp-specific signals at the bacterial surface by immunofluorescence microscopy, additional biochemical studies have to be performed before we can make a final statement regarding this aspect. In preliminary experiments, we detected Flp multimers in the supernatant of PypB-overproducing bacteria after gel filtration chromatography, further indicating that Flp is able to polymerize (data not shown). These multimers might be unstable due to decreased hydrophobic interactions via the N termini of the Flp protein that are necessary for pilus assembly (6). Flp pili in other bacteria are stable, and the question remains what the function of Y. enterocolitica Flp might be if it is not assembly into a pilus associated with biofilm formation or adhesion onto surfaces. Flp is able to mediate Y. enterocolitica microcolony formation, and this might result in a growth advantage under specific conditions compared to planktonic bacteria. It might be possible that Flp acts as a “glue” mediating cell-cell contacts due to increased availability at the bacterial surfaces.

In summary, although we show that Flp is expressed in Y. enterocolitica after PypB overproduction, we could not unequivocally show that it is assembled into a pilus. Therefore, future studies will be aimed at identifying factors that might play a role in pilus biogenesis. To this end, we will identify in vitro conditions that result in tad activation, as this might also result in pilus expression and assembly, but we will also study the Flp protein and other tad-encoded proteins necessary for pilus biogenesis using molecular and biochemical approaches. Alternatively, we cannot rule out that pili are not formed and that the tad locus encodes a secretion system determined to secrete Flp subunits into the supernatant. In this case, Flp might have a different role independent of pilus-mediated functions that needs to be determined. As the tad locus is found in pathogenic as well as nonpathogenic species of the genus Yersinia, the function of the tad locus might not be associated with virulence but with a Yersinia-specific environment outside the human host.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefan Fälker for his contributions during the initial phase of the project, Christoph Buss and other members of our group for suggestions and discussion, and Anja Grützner, Annika Pfeiffer, and Kingsley Cheung for assistance. This study is part of the Ph.D. thesis of J.S. and K.W.

This work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (HE3079/6-1 and HE3079/9-1; Graduiertenkolleg 1409/1).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 14 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernard, C. S., C. Bordi, E. Termine, A. Filloux, and S. de Bentzmann. 2009. Organization and PprB-dependent control of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa tad locus, involved in Flp pilus biology. J. Bacteriol. 191:1961-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bottone, E. J. 1997. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:257-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collyn, F., A. Billault, C. Mullet, M. Simonet, and M. Marceau. 2004. YAPI, a new Yersinia pseudotuberculosis pathogenicity island. Infect. Immun. 72:4784-4790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collyn, F., M. A. Lety, S. Nair, V. Escuyer, A. Ben Younes, M. Simonet, and M. Marceau. 2002. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis harbors a type IV pilus gene cluster that contributes to pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 70:6196-6205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornelis, G. R. 2002. The Yersinia Ysc-Yop ‘type III’ weaponry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:742-752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig, L., M. E. Pique, and J. A. Tainer. 2004. Type IV pilus structure and bacterial pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2:363-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Bentzmann, S., M. Aurouze, G. Ball, and A. Filloux. 2006. FppA, a novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa prepilin peptidase involved in assembly of type IVb pili. J. Bacteriol. 188:4851-4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Tahir, Y., and M. Skurnik. 2001. YadA, the multifaceted Yersinia adhesin. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:209-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fronzes, R., H. Remaut, and G. Waksman. 2008. Architectures and biogenesis of non-flagellar protein appendages in Gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 27:2271-2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerlach, R. G., and M. Hensel. 2007. Protein secretion systems and adhesins: the molecular armory of Gram-negative pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297:401-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guzman, L. M., D. Belin, M. J. Carson, and J. Beckwith. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121-4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haase, E. M., J. O. Stream, and F. A. Scannapieco. 2003. Transcriptional analysis of the 5′ terminus of the flp fimbrial gene cluster from Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Microbiology 149:205-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iriarte, M., J. C. Vanooteghem, I. Delor, R. Diaz, S. Knutton, and G. R. Cornelis. 1993. The Myf fibrillae of Yersinia enterocolitica. Mol. Microbiol. 9:507-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isberg, R. R., D. L. Voorhis, and S. Falkow. 1987. Identification of invasin: a protein that allows enteric bacteria to penetrate cultured mammalian cells. Cell 50:769-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kachlany, S. C., P. J. Planet, M. K. Bhattacharjee, E. Kollia, R. DeSalle, D. H. Fine, and D. H. Figurski. 2000. Nonspecific adherence by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans requires genes widespread in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 182:6169-6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kachlany, S. C., P. J. Planet, R. DeSalle, D. H. Fine, and D. H. Figurski. 2001. Genes for tight adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: from plaque to plague to pond scum. Trends Microbiol. 9:429-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kachlany, S. C., P. J. Planet, R. Desalle, D. H. Fine, D. H. Figurski, and J. B. Kaplan. 2001. flp-1, the first representative of a new pilin gene subfamily, is required for non-specific adherence of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Mol. Microbiol. 40:542-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim, T. J., B. M. Young, and G. M. Young. 2008. Effect of flagellar mutations on Yersinia enterocolitica biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:5466-5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinder, S. A., J. L. Badger, G. O. Bryant, J. C. Pepe, and V. L. Miller. 1993. Cloning of the YenI restriction endonuclease and methyltransferase from Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O8 and construction of a transformable R−M+ mutant. Gene 136:271-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kram, K. E., G. A. Hovel-Miner, M. Tomich, and D. H. Figurski. 2008. Transcriptional regulation of the tad locus in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans: a termination cascade. J. Bacteriol. 190:3859-3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LaPointe, C. F., and R. K. Taylor. 2000. The type 4 prepilin peptidases comprise a novel family of aspartic acid proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1502-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larkin, M. A., G. Blackshields, N. P. Brown, R. Chenna, P. A. McGettigan, H. McWilliam, F. Valentin, I. M. Wallace, A. Wilm, R. Lopez, J. D. Thompson, T. J. Gibson, and D. G. Higgins. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947-2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macdonald, D. L., B. L. Pasloske, and W. Paranchych. 1993. Mutations in the fifth-position glutamate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin affect the transmethylation of the N-terminal phenylalanine. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:500-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press., Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 25.Miller, V. L., and S. Falkow. 1988. Evidence for two genetic loci in Yersinia enterocolitica that can promote invasion of epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 56:1242-1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nika, J. R., J. L. Latimer, C. K. Ward, R. J. Blick, N. J. Wagner, L. D. Cope, G. G. Mahairas, R. S. Munson, Jr., and E. J. Hansen. 2002. Haemophilus ducreyi requires the flp gene cluster for microcolony formation in vitro. Infect. Immun. 70:2965-2975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasloske, B. L., D. G. Scraba, and W. Paranchych. 1989. Assembly of mutant pilins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: formation of pili composed of heterologous subunits. J. Bacteriol. 171:2142-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pelicic, V. 2008. Type IV pili: e pluribus unum? Mol. Microbiol. 68:827-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez, B. A., P. J. Planet, S. C. Kachlany, M. Tomich, D. H. Fine, and D. H. Figurski. 2006. Genetic analysis of the requirement for flp-2, tadV, and rcpB in Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 188:6361-6375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Planet, P. J., S. C. Kachlany, D. H. Fine, R. DeSalle, and D. H. Figurski. 2003. The widespread colonization island of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Nat. Genet. 34:193-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shutinoski, B., M. A. Schmidt, and G. Heusipp. 2010. Transcriptional regulation of the Yts1 type-II secretion system of Yersinia enterocolitica and identification of secretion substrates. Mol. Microbiol. 75:676-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strom, M. S., and S. Lory. 1991. Amino acid substitutions in pilin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Effect on leader peptide cleavage, amino-terminal methylation, and pilus assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 266:1656-1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strom, M. S., and S. Lory. 1987. Mapping of export signals of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pilin with alkaline phosphatase fusions. J. Bacteriol. 169:3181-3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Takayasu, K. T. 1980. Immunocytochemistry on ultrathin frozen sections. Histochem. J. 12:381-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomson, N. R., S. Howard, B. W. Wren, M. T. Holden, L. Crossman, G. L. Challis, C. Churcher, K. Mungall, K. Brooks, T. Chillingworth, T. Feltwell, Z. Abdellah, H. Hauser, K. Jagels, M. Maddison, S. Moule, M. Sanders, S. Whitehead, M. A. Quail, G. Dougan, J. Parkhill, and M. B. Prentice. 2006. The complete genome sequence and comparative genome analysis of the high pathogenicity Yersinia enterocolitica strain 8081. PLoS Genet. 2:e206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tomich, M., D. H. Fine, and D. H. Figurski. 2006. The TadV protein of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans is a novel aspartic acid prepilin peptidase required for maturation of the Flp1 pilin and TadE and TadF pseudopilins. J. Bacteriol. 188:6899-6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomich, M., P. J. Planet, and D. H. Figurski. 2007. The tad locus: postcards from the widespread colonization island. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:363-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner, K., J. Schilling, S. Falker, M. A. Schmidt, and G. Heusipp. 2009. A regulatory network controls expression of the in vivo-expressed HreP protease of Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Bacteriol. 191:1666-1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, R. F., and S. R. Kushner. 1991. Construction of versatile low-copy-number vectors for cloning, sequencing and gene expression in Escherichia coli. Gene 100:195-199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zuker, M. 2003. Mfold Web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3406-3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]