Abstract

Pantoea stewartii SW2 contains 13 plasmids. One of these plasmids, pSW200, has a replicon that resembles that of ColE1. This study demonstrates that pSW200 contains a 9-bp UP element, 5′-AAGATCTTC, which is located immediately upstream of the −35 box in the RNAII promoter. A transcriptional fusion study reveals that substituting this 9-bp sequence reduces the activity of the RNAII promoter by 78%. The same mutation also reduced the number of plasmid copies from 13 to 5, as well as the plasmid stability. When a similar sequence in a ColE1 derivative, pYCW301, is mutated, the copy number of the plasmid also declines from 34 to 16 per cell. Additionally, inserting this 9-bp sequence stabilizes an unstable pSW100 derivative, pSW142K, which also contains a replicon resembling that of ColE1, indicating the importance of this sequence in maintaining the stability of the plasmid. In conclusion, the 9-bp sequence upstream of the −35 box in the RNAII promoter is required for the efficient synthesis of RNAII and maintenance of the stability of the plasmids in the ColE1 family.

Plasmids of the ColE1 type are commonly found in the bacteria belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae (2, 9, 10, 13, 14, 27, 37, 55). Rather than utilizing a replication initiation protein, these plasmids synthesize preprimer RNA (22, 31), which forms a DNA-RNA hybrid at oriV (48), which allows the RNA to be cleaved by RNase H (22, 41). The cleaved RNA, which is called RNAII, acts as a primer to facilitate the initiation of plasmid replication (22). Therefore, the capacity of the preprimer RNA to couple with oriV is critical to the initiation of plasmid replication (22, 48). The plasmid also transcribes RNAI, which is complementary to the 5′ region of preprimer RNA (22, 49). The annealing between RNAI and preprimer RNA changes the conformation of the preprimer RNA, preventing its coupling and cleavage at oriV (30); accordingly, replication is prevented. Therefore, RNAI critically controls the copy number of a ColE1-type plasmid and determines the incompatibility phenotype of the plasmid (47).

As is generally known, ColE1-type plasmids usually do not have a partition system for segregation. Rather, they randomly segregate into daughter cells (16, 45). The lack of an active partition system makes the plasmid copy numbers critical to plasmid stability (45). For instance, plasmid ColE1 has 15 copies per cell (38, 40). According to the equation for the frequency of the loss of ColE1 after plasmid replication (44, 45), the probability of a daughter cell not receiving 1 of the 30 copies of ColE1 is 1.9 × 10−9, a value which reveals why ColE1 can be stably maintained in its hosts. However, the copy number of ColE1 is reduced by half when a dimer is formed (45). Under such conditions, the probability of a cell not receiving a plasmid substantially increases to 6.1 × 10−5, which value explains why dimer formation can reduce the stability of ColE1 (45). Hence, ColE1 employs a cer-xer system to convert the dimer by recombination back to monomers to stabilize the plasmid (5, 6, 12, 46). ColE1 is known to use various strategies to keep its number of copies constant. Earlier investigation established that the level of preprimer synthesis and the amount of RNAII affect the copy number of ColE1 (34). Therefore, mutating the sequence that promotes the synthesis of preprimer RNA commonly reduces the copy number and the stability of the plasmid (34). As is well known, the C-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit (αCTD) often binds to a 17-bp A- and T-rich sequence, called an UP element, enhancing the transcriptional activity of various promoters (4, 17, 20, 36). In fact, each of the two αCTDs in RNA polymerase binds to two subsites in the element, which are centered at positions −42 and −52 (17, 20). Ross et al. (36) demonstrated that the transcription activity of the RNAII promoter (RNAIIp) in vitro depends on αCTD, suggesting that an UP element is required for the efficient synthesis of RNAII. Other sequences in RNAIIp that are important to RNAII synthesis are two Dam methylation sequences at −43 and −32; mutations at these two sites reduce the activity of the promoter and the stability of the plasmid (34). The amount of RNAI and its ability to anneal with preprimer RNA also affect the frequency of replication initiation and the copy number of the ColE1 plasmid (26, 35). For instance, the ColE1 plasmid encodes a protein, RNA one modulator (Rom), which binds and stabilizes the RNAI preprimer RNA hybrid to repress the formation of RNAII and the initiation of ColE1 replication (1, 43). Furthermore, Ala-tRNA(UGC) appears to facilitate RNAI cleavage in vitro in the presence of Mg2+, which may result in an increase in the ColE1 copy number (51, 52). The pcnB gene, which encodes poly(A) polymerase I to polyadenylate and reduce the stability of RNAI (23, 28, 53, 54), is also critically involved in maintaining the copy number of ColE1 (21, 28, 39).

Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii, a member of the Enterobacteriaceae, is a corn pathogen that causes Stewart's wilt (15). One of the strains, SW2, contains 13 plasmids (15). The two smallest plasmids in this strain, pSW100 and pSW200, contain a replicon that resembles that of ColE1 (18, 19). Although neither of these plasmids carries a gene that encodes the synthesis of bacteriocin, these two plasmids contain mob genes and a bom region that are also present in ColE1 (19). The mob genes and bom enable pSW100 and pSW200 to be mobilized by the F plasmid (19). Plasmid pSW100 has about 10 copies per cell (18) and uses TraC in the sex pilus assembly as an apparatus for segregation to maintain the stability of the plasmid (25). This study finds that a 9-bp sequence region, which is located at −43 in RNAIIp in pSW200 and ColE1, is an UP element and important to the synthesis of RNAII and the stability of the plasmid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture medium.

Escherichia coli HB101 (8) was used as a host to determine the stability of the pSW200 replicon. E. coli CSH50 (33) was used in fusion studies to analyze the activity of RNAIIp. LB medium was utilized to culture E. coli. Ampicillin (Ap) at 100 μg/ml, kanamycin (Km) at 50 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol (Cm) at 25 μg/ml were used to culture the strains that were resistant to these antibiotics.

Plasmids.

A Km resistance gene from pUC4-KISS (3) was isolated by PstI digestion and inserted into the PstI site in pSW200 to yield pSW201 (19). The Km resistance gene was ligated with a TaqI DNA fragment that contained the sequence from nucleotide (nt) 172 to 1473 in pSW200, and generated pSW203 (Fig. 1 A) (19). DNA fragments that contained the regions in pSW200 from nt 334 to 998, 345 to 998, 354 to 998, 372 to 998, 375 to 998, 378 to 998, 379 to 998, 380 to 998, 381 to 998, 382 to 998, and 389 to 998 in pSW200 (Fig. 2 A) were amplified by PCR, using pSW201 as a template, and ligated with a Km resistance gene to generate pSW240, pSW241, pSW242, pSW243, pSW244, pSW245, pSW246, pSW247, pSW248, pSW249 and pSW250, respectively. Plasmid pSW240M had a sequence that was identical to that of pSW240, except that the sequence from nt 380 to 386 (Fig. 1B) was mutated from 5′-AAGATCT to 5′-CCTCGAG. The sequence between nt 378 and 388 in pSW245 was mutated to generate pSW245-M1, pSW245-M2, pSW245-M3, pSW245-M4, pSW245-M5, pSW245-M6, pSW245-M7, pSW245-M8, pSW245-M9 and pSW245-M10 (Fig. 3 A). 5′-CC, 5′-CCGGG, and 5′-CCCCCCCGGG were inserted at nt 389 in pSW245 and generated pSW245-I2, pSW245-I5, and pSW245-I10, respectively. Plasmid pSW261 was formed by inserting a DNA fragment that contained the region from nt 360 to 439 in pSW200 at the XbaI site in a fusion vector, pKM005 (29). The sequence from nt 380 to 386 in pSW261 was mutated to 5′-CCTCGAG and generated pSW262. Plasmid pSW263 was constructed by inserting a PCR-amplified DNA fragment that contained the region from nt 380 to 439 into pKM005 (Table 1). Plasmid pSW264 had a sequence that was identical to that of pSW263, except the 5′-GATC sequence at nt 382 was changed to 5′-AATC (Table 1). Plasmids pSW266, pSW267, pSW268, and pSW269 were constructed by the same approach, using DNA fragments that contained the region from nt 381, 382, 387, and 389, respectively, to 439 (Table 1). A DNA fragment that contained the sequence from nt 2436 to 3161 in pBR322 (7, 38) was ligated with a Km resistance gene to yield pYCW301. Plasmid pYCW301M had a sequence that was identical to that of pYCW301, except that the sequence from nt 3125 to 3131 was mutated from 5′-AAGGTCT to 5′-CCTCGAG. Plasmid pSW142K was constructed by ligating a DNA fragment that contained the nt-83-to-745 region in pSW100 (25) with a Km resistance gene. 5′-AAGATCTTC was inserted at the 5′ end of the pSW100 replicon in pSW142K to generate pSW142KWR. A DNA fragment that encoded the E. coli αCTD, from amino acid 236 to amino acid 329, was amplified using the primers 5′-CGATGAATTCGATGTACGTCAGCCTGAAGTGAAAGAAGAG and 5′-CGATCTCGAGTTACTCGTCAGCGATGCTTGCCGGTGG and inserted into the EcoRI and XhoI sites in pET-32a(+) (Novagen) to generate pWCTD and thus express histidine-tagged αCTD (His-αCTD).

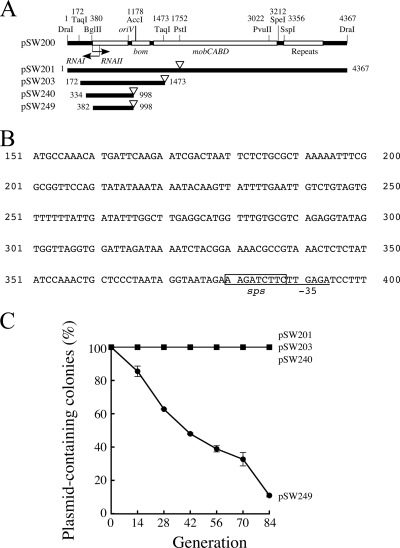

FIG. 1.

Identifying the region in pSW200 that affects plasmid stability. (A) Map of pSW201, pSW203, pSW240, and pSW249. An empty triangle represents a kanamycin resistance gene. (B) Sequence from nt 151 to 400 in pSW200. “−35,” −35 box of RNAIIp; sps, sequence for plasmid stability. (C) E. coli HB101, which contained pSW201, pSW203, pSW240, or pSW249, was cultured and replica plated to determine the numbers of colonies that did not contain a plasmid. The experiment was performed three times. Error bars represent standard deviations.

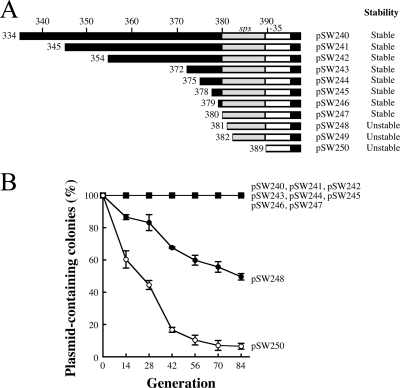

FIG. 2.

Region upstream of −35 box in RNAIIp and stability of the pSW200 replicon. (A) The region upstream of the −35 box in RNAIIp, from nt 334 to 388, in pSW240 was deleted to generate plasmids pSW241 to pSW250. sps, sequence for plasmid stability (gray box). (B) E. coli HB101, which contained one of these plasmids, was cultured and replica plated to determine the numbers of colonies that did not contain a plasmid. The experiment was performed three times. Error bars represent standard deviations.

FIG. 3.

Sequence essential to the stability of pSW200. (A) The sps region in pSW245 was mutated by nucleotide substitution or insertion. “−35” represents the −35 box in RNAIIp. sps, sequence for plasmid stability. (B and C) Stability of plasmids was evaluated in E. coli HB101. Cells were cultured and replica plated to determine the numbers of colonies that did not contain a plasmid. The experiment was performed three times. Error bars represent standard deviations.

TABLE 1.

Influence of sps on activity of RNAIIp and plasmid stability

| Plasmid | Fragment in pSW200 (nt) | Sequence in sps-−35 region in RNAIIpa | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units) | Plasmid stabilityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pSW261 | 360-439 | 5′-AAGATCTTCTTGAGATC | 1,932 ± 127.4 | 100 |

| pSW262 | 360-439 | 5′-CCTCGAGTCTTGAGATC | 422 ± 67.6 | 33 |

| pSW266 | 381-439 | 5′-AGGTCTTCTTGAGATC | 1,360 ± 189.9 | 50 |

| pSW267 | 382-439 | 5′-GGTCTTCTTGAGATC | 908 ± 16.3 | 30 |

| pSW268 | 387-439 | 5′-TCTTGAGATC | 735 ± 53.7 | 10 |

| pSW269 | 389-439 | 5′-TTGAGATC | 659 ± 79.8 | 6.5 |

| pSW263 | 380-439 | 5′-AAGATCTTCTTGAGATC | 2,321 ± 329.4 | 100 |

| pSW264 | 380-439 | 5′-AAAATCTTCTTGAGATC | 2,384 ± 157.6 | 100 |

| pKM005 | NAc | NAc | 7.8 ±1 | NA |

Underlined sequence represents nucleotide substitution. The −35 box is boldfaced.

Determined after 84 generations of culturing.

NA, not applicable.

Determining plasmid stability.

Plasmid stability was determined using a method that has been described elsewhere (25). Cells were cultured in LB-Km broth overnight at 37°C. The culture was then used to inoculate LB broth with an inoculum size of 1%. The bacteria were subcultured with an inoculum of the same size every 12 h to achieve seven generations of growth. After subculturing, cells were plated on LB agar. About 1,000 colonies were replica plated on LB-Km agar to determine the percentage of the colonies that had lost their plasmid. Each stability experiment was performed three times. The numbers of colonies on three LB-agar plates were averaged, and the standard deviation was calculated.

Determining plasmid copy number.

E. coli HB101(pSW240, pACYC184) and E. coli HB101(pSW240M, pACYC184) were cultured overnight in LB-Km broth at 37°C. Plasmids in the cells were isolated, cut by SmaI, serially diluted, and separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. Plasmid bands were then photographed over a UV transilluminator and using a digital camera after the gel had been stained with ethidium bromide. The intensity of the plasmid bands was measured using the Gel-Pro software program (Media Cybernetics). The values from the bands were graphed, and the values in the linear range were used for copy number estimation. Plasmid pACYC184, which has 18 copies per cell (10, 38), was used as a reference to determine the copy numbers of pSW240 and pSW240M in E. coli HB101. The copy numbers of pYCW301 and pYCW301M were determined by the same method, except that the plasmids were digested with SacII.

Transcriptional fusion.

The β-galactosidase activity exhibited by a fusion plasmid in E. coli CSH50 was measured using the method of Zubay et al. (56). The results of three independent experiments were averaged, and the standard deviation was calculated.

DNA affinity precipitation assay.

A 5′-biotin end-labeled double-stranded DNA probe, p-sps, which contained the sequence in the region between nt 374 and 423 in pSW200, was used to study the binding of αCTD to an UP sequence. Probe p-msps had the same sequence as p-sps except that the region between nt 380 and 388 was changed from 5′-AAGATCTTC to 5′-CCACGAGGA. αCTD (250 ng), purified from E. coli BL21(pWCTD) using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose beads (Qiagen) according to a method described elsewhere (24), was mixed with 1 μg of a biotinylated probe. The beads were washed and captured using streptavidin MagneSphere paramagnetic particles (Promega). After washing, the proteins that were bound to the beads were extracted using a 2× electrophoresis sample buffer, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and detected by immunoblotting using anti-His antibody (Sigma), following the method of Chang et al. (11). A peptide that was expressed from empty pET-32a(+), which contained the sequences for Trx, His, and an S tag, was purified by the same method and used as a negative control.

RESULTS

Identifying the region in pSW200 that determines plasmid stability.

Deletions were made in pSW200 to identify the region that was critical to the stability of the plasmid. Plating results indicated that pSW201, which contained the entire pSW200 sequence and a kanamycin resistance gene (Fig. 1A), was stable in E. coli HB101; no plasmid loss was observed during 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 1C). Plasmid pSW203, which contained the region from nt 172 to 1473 in pSW200 and a Km resistance gene (Fig. 1A and B), was also stable in E. coli HB101 (Fig. 1C), indicating that the region between nt 172 and 1473 contains the sequence on which the stability of the plasmid depends. Deleting the regions from nt 172 to 333 and nt 999 to 1473 from pSW203 (pSW240) (Fig. 1A and B) also did not alter the stability of the plasmid (Fig. 1C). However, deletion of the region from nt 334 to 381 (pSW249) (Fig. 1A and B) affected the stability of the plasmid. After 14 and 42 generations of culturing, 14.5% and 52% of the colonies had lost pSW249, respectively. At the 84th generation, the corresponding value was 89% (Fig. 1C). These results show that the region between nt 334 and 381 (Fig. 1A and B) contains the sequence that is critical to the stability of the pSW200 replicon.

Deletion analysis of sequence upstream of the −35 box in RNAIIp.

Since the region between nt 334 and 381 contained a sequence that affected plasmid stability, this study deleted the region between nt 334 and 379 in pSW240 and generated pSW241, pSW242, pSW243, pSW244, pSW245, pSW246, and pSW247 to determine the sequence that is important to plasmid stability (Fig. 2A). These plasmids were stable in E. coli HB101 throughout 84 generations of culturing in LB broth (Fig. 2B). However, when the deletion was extended to nt 380, the plasmid, pSW248 (Fig. 2A), became unstable. After 14, 42, and 84 generations of culturing, 13.5%, 34.2%, and 50.4% of the cells, respectively, had lost the plasmid (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, plasmid pSW249, which contained a deletion from nt 334 to 381, was also unstable (Fig. 1C). When the deletion reached nt 388, the plasmid, pSW250 (Fig. 2A), was lost more quickly than pSW248. At the 14th generation, 39.7% of the cells had lost the plasmid; at the 42nd generation, the corresponding percentage was 83.4%, and at the 84th generation, it was 93.5% (Fig. 2B). The result indicated that the region between nt 380 and 388 is important to plasmid stability.

Mutational analysis of pSW245.

In this study, pSW245 was mutated to elucidate how the sequence between nt 378 and 388 influenced the stability of the pSW200 replicon. Mutating nt 378 and 379 (pSW245-M1) (Fig. 3A) did not alter plasmid stability. The plasmid was stable in E. coli HB101 during 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 3B). However, a plasmid with a mutation in the region between nt 380 and 382 (pSW245-M2) (Fig. 3A) was unstable. At the 84th generation, the plasmid was absent from 95.2% of the colonies (Fig. 3B). Mutating the regions from nt 383 to 385 (pSW245-M3) (Fig. 3A) and nt 386 to 388 (pSW245-M4) (Fig. 3A) also destabilized the replicon. At the 84th generation, 74.4% and 95% of the colonies, respectively, had lost the plasmid (Fig. 3B). Additionally, mutating the nucleotide sequence immediately upstream of the −35 box, nt 387 or 388, only slightly affected the stability of the plasmid. A mutation from T to G at nt 387 (pSW245-M7) decreased the plasmid stability only 1.5% after 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 3A and B). On other hand, a T-to-A (pSW245-M9) or T-to-C (pSW245-M8) mutation (Fig. 3A) did not influence plasmid stability, and the plasmids were stable over 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 3B). Similarly, a single nucleotide substitution from C to A at nt 388 (pSW245-M6) (Fig. 3A) reduced the stability by 1.5% after 84 generations of culturing. However, mutating nucleotides 387 and 388 simultaneously from TC to GA (pSW245-M5) markedly reduced the stability of the plasmid; by the 84th generation, 29.3% of the colonies had lost the plasmid (Fig. 3B). Mutating nt 386 to 388 from TTC to GGA (pSW245-M4) (Fig. 3A) further reduced stability. At the 84th generation, 95% of the colonies had lost the plasmid (Fig. 3B), indicating that the region from nt 380 to 388, which has a 5′-AAGATCTTC sequence, is essential to maximal stability of pSW200. This segment of DNA is here called the sequence for plasmid stability or sps. Because the sps region contains a Dam methylation site, 5′-GATC, this study mutated this sequence to 5′-AATC (Fig. 3A) and found that the mutant, pSW245-M10, was stable during 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 3B). Additionally, 2, 5, and 10 nucleotides were separately inserted between sps and the −35 box of RNAIIp. These plasmids, pSW245-I2, pSW245-I5, and pSW245-I10 (Fig. 3A), were unstable in E. coli HB101. At the 84th generation, 86%, 99%, and 73% of the colonies had lost the plasmids, respectively (Fig. 3C), suggesting that the distance between sps and the −35 box is also crucial to plasmid stability.

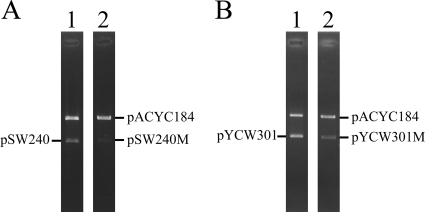

sps and plasmid copy number.

Whether mutation of sps changed the copy number of pSW240 was studied. The first seven nucleotides in sps in pSW240 were changed from 5′-AAGATCT to 5′-CCTCGAG to yield pSW240M. In E. coli HB101, the mutant plasmid was unstable. After culturing in LB broth for 84 generations, 67% of the colonies had lost the plasmid (data not shown). Meanwhile, E. coli HB101 was cotransformed with pACYC184 and pSW240. The transformants were cultured in LB broth that contained Cm and Km. The plasmids in the cells were purified, linearized by restriction digestion, and then separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 4 A, lane 1). Plasmid pACYC184 is known to have 18 copies per cell (10, 38). The intensity of the pSW240 band was compared with that of pACYC184, and the value was normalized to the size of the plasmid. Accordingly, pSW240 was estimated to have 13 copies per cell. A parallel experiment demonstrated that pSW240M had five copies per cell (Fig. 4A, lane 2), indicating that a mutation in sps reduces the copy number of the plasmid.

FIG. 4.

Copy numbers of pSW240M and pYCW301M. E. coli HB101(pACYC184) was transformed with pSW240 (lane 1) or pSW240M (lane 2) (A) or pYCW301 (lane 1) or pYCW301M (lane 2) (B). Plasmids were isolated from the cell and cut using SmaI (A) or SacII (B). DNA was then separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. The intensity of the plasmid bands was determined using Gel-Pro software.

sps and synthesis of RNAII.

To demonstrate that sps is important to the activity of RNAIIp, a transcriptional fusion between the region in pSW200 from nt 360 to 439 and lacZ was generated in a fusion vector, pKM005. This fusion plasmid, pSW261, in E. coli CSH50 exhibited 1,932 Miller units of β-galactosidase activity (Table 1). Another fusion plasmid in E. coli CSH50, pSW262, which had a sequence identical to that of pSW261 except that the first seven nucleotides in sps were mutated to 5′-CCTCGAG, exhibited 422 units of activity (Table 1), 78% less than that of pSW261. Deleting sps in pSW261, e.g., pSW266, pSW267, pSW268, and pSW269, also reduced promoter activity (Table 1), indicating that sps is critical to the activity of RNAIIp. The instability of the plasmid was shown to be associated with reduced transcriptional activity (Table 1). The 5′-GATC sequence in sps in pSW263 was also mutated (Table 1). Changing 5′-GATC to 5′-AATC in pSW264 did not affect the activity of RNAIIp (Table 1).

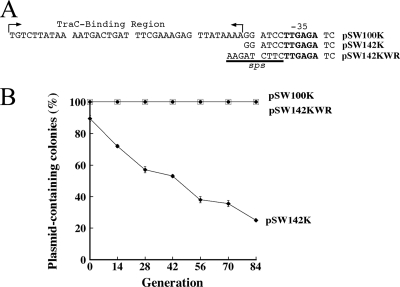

Stabilization of pSW100 replicon by sps.

The effect of sps on plasmid stability in a context other than pSW200 was examined. In addition to pSW200, P. stewartii SW2 has another ColE1-like plasmid, pSW100 (18). Unlike pSW200, pSW100 does not contain a sequence resembling sps. Our earlier work established that pSW100 utilizes a 38-bp TraC-binding sequence for segregation (Fig. 5 A) and that this sequence is important to the stability of the plasmid (25). This work verified that a pSW100 derivative that contains a Km resistance gene, pSW100K (Fig. 5A), was stable (Fig. 5B) and that deleting the 38-bp TraC-binding region from the plasmid, pSW142K (Fig. 5A), decreased the stability of the plasmid 75% over 84 generations of culturing in LB broth. However, inserting sps upstream of the −35 box in RNAIIp in pSW142K (pSW142KWR) (Fig. 5A) stabilized the plasmid. No plasmid loss was observed over 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Stabilization of pSW100 replicon by sps. (A) Sequence upstream of −35 region in pSW100K, pSW142K, and pSW142KWR. (B) E. coli HB101(pSW100K), E. coli HB101(pSW142K), and E. coli HB101(pSW142KWR) were cultured and replica plated to determine the numbers of colonies that did not contain a plasmid. The experiment was performed three times. Error bars represent standard deviations.

sps and copy number of ColE1 replicon.

Plasmid pBR322 contains a sequence, 5′-AGGATCTTC, in RNAIIp which resembles sps in pSW200, 5′-AAGATCTTC. To study the function of this sequence, a DNA fragment that contained the region from nt 2436 to 3161 in pBR322 (38), including the entire replicon and sps, was ligated with a Km resistance gene to yield pYCW301. According to the analysis, a copy number of 34 copies per cell was estimated for pYCW301 (Fig. 4B, lane 1). When the first seven nucleotides in sps in pYCW301 were changed from 5′-AGGATCT to 5′-CCTCGAG, the copy number of the mutant plasmid, pYCW301M, decreased to 16 copies per cell (Fig. 4B, lane 2).

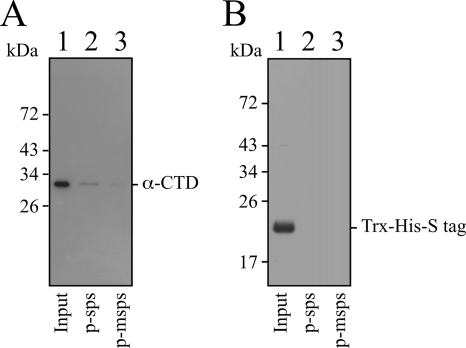

Binding of αCTD to sps.

An earlier study demonstrated that the transcription in vitro of the RNAII promoter depends on αCTD, suggesting that the binding of αCTD to a region upstream of the −35 box is required to maximize RNAII synthesis (36). Therefore, a DNA affinity precipitation assay was performed to confirm the binding of His-αCTD to sps. Accordingly, His-αCTD (Fig. 6 A, lane 1) and a biotinylated probe, p-sps, which contained RNAIIp and sps, were mixed. After the probe was captured using streptavidin magnetic beads, immunoblotting revealed the binding of His-αCTD to the probe (Fig. 6A, lane 2). A parallel experiment indicated that His-αCTD did not bind to a probe, p-msps, that lacks sps (Fig. 6A, lane 3), confirming the binding of His-αCTD to sps. Additionally, His-αCTD that was used herein had a segment of peptide in the N-terminal region that contained Trx, His, and S tags. This segment of peptide, which was purified from E. coli BL21[pET-32a(+)] (Fig. 6B, lane 1), did not bind to p-sps or p-msps (Fig. 6B, lanes 2 and 3), indicating that the binding of His-αCTD to p-sps was not attributable to the N-terminal tag region of the protein.

FIG. 6.

Binding of αCTD to sps. His-αCTD (A) or the N-terminal tag region (Trx-His-S tag) (B), which was purified from E. coli BL21(pWCTD) or E. coli BL21[pET-32a(+)], respectively, was mixed with a probe, p-sps, which contained sps (lane 2) or a mutant probe, p-msps (lane 3), which did not contain sps. Proteins that were bound to the probe were captured using streptavidin magnetic beads and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-His antibody. Lane 1 was loaded with 250 ng of purified protein.

DISCUSSION

P. stewartii SW2 contains 13 plasmids. The two smallest plasmids in the strain, pSW100 and pSW200, are present in all P. stewartii strains that are isolated from nature (15), indicating that these two plasmids are stable throughout evolution. As is commonly known, plasmids of the ColE1 type usually do not use an active partition system for segregation to maintain their stability (16, 45). Rather, they segregate in random numbers into daughter cells during cell division (16, 45). Therefore, the goal of this work is to elucidate the mechanism by which pSW200 maintains its stability in the cell.

According to our results, pSW200 contains a 9-bp sequence, sps, that is located immediately upstream of the −35 box of RNAIIp and is critical to the stability of the plasmid. When this sequence is mutated, the pSW200 replicon becomes unstable and is rapidly lost during 84 generations of culturing (Fig. 1, 2, and 3). An analysis of the plasmid copy number after sps was mutated indicated that the number of copies of the pSW200 replicon declines from 13 to 5 per cell (Fig. 4A). An equation, p0 = 2(1 − n) (44, 45), for the probability of the loss of ColE1 plasmids during random segregation, where p0 and n represent the probability that a cell that does not receive a plasmid during segregation and the number of copies of the plasmid before cell division, respectively, is adopted to estimate the effect of the decline in the number of copies from 13 to 5 on plasmid stability. The calculation indicates that the probability of a cell not receiving a plasmid after cell division declines substantially, from 3.0 × 10−8 to 2.0 × 10−3, as the number of copies decreases from 13 to 5, respectively. Additionally, the drop in the number of copies is probably caused by a decrease in the synthesis of preprimer RNA, since a fusion study reveals that the activity of RNAIIp decreases 78% when sps is mutated (Table 1), and an earlier study demonstrated that the level of preprimer RNA synthesis affects the number of copies of ColE1 (34). Moreover, a sequence that resembles that of sps is present at the same location in both ColE1 and p15A. In a ColE1 derivative, pYCW301, which lacks the rom gene, mutating this sequence reduces the number of copies from 34 to 16 per cell (Fig. 4B). These observations show that plasmids of the ColE1 type commonly use sps to promote the transcription of preprimer RNA to maintain a high number of copies, such that the plasmids can be stably maintained in their host. This study also analyzed the sequences of 15 plasmids of the ColE1 family in GenBank and found that 12 of them contain a consensus sequence, 5′-APuPuATCTTC, which resembles that of sps in pSW200, indicating that this sequence is present in many ColE1-type plasmids.

The UP element is a stretched A- and T-rich sequence of about 17 bp that is located immediately upstream of the −35 box and facilitates the efficient binding of RNA polymerase to a promoter through αCTD to enhance transcription (4, 17, 36). The promoters that are regulated by an UP element include E. coli rrnB P1 and that of the Bacillus subtilis fengycin synthetase operon (24, 36). In fact, an UP element contains two subsites where the two αCTDs in RNA polymerase bind (17, 20). Furthermore, the presence of only the proximal subsite, where sps is located, often suffices to activate transcription (17, 50). Ross et al. (36) demonstrated that deleting the C-terminal 73 amino acids in the RNA polymerase α subunit substantially reduced the capacity of RNA polymerase to transcribe the ColE1 preprimer RNA in vitro and proposed that the efficient synthesis of preprimer RNA depends on an UP element. This study shows that sps is indeed an UP element, since αCTD binds to sps (Fig. 6). Moreover, a transcriptional fusion that is generated with a fragment from nt 380 to 439 (pSW263), which contains an intact sps but not the sequence upstream of sps, yields LacZ activity to a degree that is similar to that of pSW261, which contains the region from nt 360 to 439 in pSW200 (Table 1), suggesting that the sequence upstream of nt 380 in pSW200 does not contain a distal UP subsite that promotes RNAII synthesis.

The ColE1 plasmid is known to contain three 5′-GATC methylation sites in RNAIIp, two of which, at −43 and −32, are also present in pSW200 (Fig. 1B). Patnaik et al. (34) demonstrated that mutations at both sites reduce the RNAIIp activity and plasmid stability. Our fusion study established that mutating the sequence at −43 in pSW200 to 5′-AATC does not affect the activity of RNAIIp or plasmid stability (Table 1), indicating that methylation at this site may not be important to RNAII synthesis. However, the possibility that methylation at −43 is important to RNAIIp activity and mutating the sequence to 5′-AATC strengthens the function of sps as an UP element, potentially compensating for the mutation of the methylation site at −43, cannot be excluded. Additionally, 5′-AGATCT in sps is a DnaA-binding site (32, 42), but the binding of DnaA to sps may not be important, since an earlier study revealed that ColE1 replication is independent of the dnaA gene (14).

Plasmid pSW200 may depend on additional mechanisms to maintain stability. In fact, pSW200 contains 41 15-bp repeats, from nt 3341 to 3955 (Fig. 1A) (19). This region confers a phenotype of plasmid exclusion (19); accordingly, a pSW200 derivative, pSW207, which does not contain the repeats cannot transform a host that contains a resident homoplasmid, pSW201, which itself contains the repeats (19), suggesting that the stability of pSW200 depends on these repeats. The function of these repeats is now being studied. In conclusion, this work identifies a sequence, sps, that is important to the transcription of RNAII and to maintaining the copy number of plasmids of the ColE1 type.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mei-Hui Lin and Wan-Ju Ke for their critiques. We also thank Li-Kwan Chang for her technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from Chang-Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPD170251), the Chang-Gung Research Center for Pathogenic Bacteria, and the National Science Council of the Republic of China (NSC 90-2320-B-182-063).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 21 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrazi, M., G. Fellas, E. G. Kapetaniou, D. Kotsifaki, M. Providaki, and M. Kokkinidis. 2008. Purification, crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of a variant of the ColE1 Rop protein. Acta Crystallogr. F 64:432-434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avgustin, J. A., and M. Grabnar. 2007. Sequence analysis of the plasmid pColG from the Escherichia coli strain CA46. Plasmid 57:89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barany, F. 1985. Single-stranded hexameric linkers: a system for in-phase insertion mutagenesis and protein engineering. Gene 37:111-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benoff, B., H. Yang, C. L. Lawson, G. Parkinson, J. Liu, E. Blatter, Y. W. Ebright, H. M. Berman, and R. H. Ebright. 2002. Structural basis of transcription activation: the CAP-α CTD-DNA complex. Science 297:1562-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaby, I. K., and D. K. Summers. 2009. The role of FIS in the Rcd checkpoint and stable maintenance of plasmid ColE1. Microbiology 155:2676-2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blakely, G., G. May, R. McCulloch, L. K. Arciszewska, M. Burke, S. T. Lovett, and D. J. Sherratt. 1993. Two related recombinases are required for site-specific recombination at dif and cer in E. coli K12. Cell 75:351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolivar, F., R. L. Rodriguez, P. J. Greene, M. C. Betlach, H. L. Heyneker, H. W. Boyer, J. H. Crosa, and S. Falkow. 1977. Construction and characterization of new cloning vehicles. II. A multipurpose cloning system. Gene 2:95-113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao, V., T. Lambert, and P. Courvalin. 2002. ColE1-like plasmid pIP843 of Klebsiella pneumoniae encoding extended-spectrum β-lactamase CTX-M-17. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1212-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang, A. C., and S. N. Cohen. 1978. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 134:1141-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, L. K., J. Y. Chung, Y. R. Hong, T. Ichimura, M. Nakao, and S. T. Liu. 2005. Activation of Sp1-mediated transcription by Rta of Epstein-Barr virus via an interaction with MCAF1. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:6528-6539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chant, E. L., and D. K. Summers. 2007. Indole signalling contributes to the stable maintenance of Escherichia coli multicopy plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 63:35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, C. Y., G. W. Nace, B. Solow, and P. Fratamico. 2007. Complete nucleotide sequences of 84.5- and 3.2-kb plasmids in the multi-antibiotic resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium U302 strain G8430. Plasmid 57:29-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins, J., P. Williams, and D. R. Helinski. 1975. Plasmid ColE1 DNA replication in Escherichia coli strains temperature-sensitive for DNA replication. Mol. Gen. Genet. 136:273-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coplin, D. L., R. G. Rowan, D. A. Chisholm, and R. E. Whitmoyer. 1981. Characterization of plasmids in Erwinia stewartii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42:599-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durkacz, B. W., and D. J. Sherratt. 1973. Segregation kinetics of colicinogenic factor col E1 from a bacterial population temperature sensitive for DNA polymerase I. Mol. Gen. Genet. 121:71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Estrem, S. T., W. Ross, T. Gaal, Z. W. Chen, W. Niu, R. H. Ebright, and R. L. Gourse. 1999. Bacterial promoter architecture: subsite structure of UP elements and interactions with the carboxy-terminal domain of the RNA polymerase α subunit. Genes Dev. 13:2134-2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fu, J. F., H. C. Chang, Y. M. Chen, Y. S. Chang, and S. T. Liu. 1995. Sequence analysis of an Erwinia stewartii plasmid, pSW100. Plasmid 34:75-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fu, J. F., J. M. Hu, Y. S. Chang, and S. T. Liu. 1998. Isolation and characterization of plasmid pSW200 from Erwinia stewartii. Plasmid 40:100-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gourse, R. L., W. Ross, and T. Gaal. 2000. UPs and downs in bacterial transcription initiation: the role of the α subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter recognition. Mol. Microbiol. 37:687-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He, L., F. Soderbom, E. G. Wagner, U. Binnie, N. Binns, and M. Masters. 1993. PcnB is required for the rapid degradation of RNAI, the antisense RNA that controls the copy number of ColE1-related plasmids. Mol. Microbiol. 9:1131-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh, T., and J. Tomizawa. 1980. Formation of an RNA primer for initiation of replication of ColE1 DNA by ribonuclease H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 77:2450-2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jasiecki, J., and G. Wegrzyn. 2006. Transcription start sites in the promoter region of the Escherichia coli pcnB (plasmid copy number) gene coding for poly(A) polymerase I. Plasmid 55:169-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ke, W. J., B. Y. Chang, T. P. Lin, and S. T. Liu. 2009. Activation of the promoter of the fengycin synthetase operon by the UP element. J. Bacteriol. 191:4615-4623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin, M. H., and S. T. Liu. 2008. Stabilization of pSW100 from Pantoea stewartii by the F conjugation system. J. Bacteriol. 190:3681-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin-Chao, S., and S. N. Cohen. 1991. The rate of processing and degradation of antisense RNAI regulates the replication of ColE1-type plasmids in vivo. Cell 65:1233-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu, M., Z. Ren, C. Lei, Y. Wen, W. Yan, and Z. Zheng. 2002. Sequence analysis and characterization of plasmid pSFD10 from Salmonella choleraesuis. Plasmid 48:59-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopilato, J., S. Bortner, and J. Beckwith. 1986. Mutations in a new chromosomal gene of Escherichia coli K-12, pcnB, reduce plasmid copy number of pBR322 and its derivatives. Mol. Gen. Genet. 205:285-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masui, Y., J. Coleman, and M. Inouye. 1983. Multipurpose expression cloning vehicles in Escherichia coli. Academic Press, New York, NY.

- 30.Masukata, H., and J. Tomizawa. 1986. Control of primer formation for ColE1 plasmid replication: conformational change of the primer transcript. Cell 44:125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masukata, H., and J. Tomizawa. 1984. Effects of point mutations on formation and structure of the RNA primer for ColE1 DNA replication. Cell 36:513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Messer, W., F. Blaesing, D. Jakimowicz, M. Krause, J. Majka, J. Nardmann, S. Schaper, H. Seitz, C. Speck, C. Weigel, G. Wegrzyn, M. Welzeck, and J. Zakrzewska-Czerwinska. 2001. Bacterial replication initiator DnaA. Rules for DnaA binding and roles of DnaA in origin unwinding and helicase loading. Biochimie 83:5-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, J. H. 1983. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 34.Patnaik, P. K., S. Merlin, and B. Polisky. 1990. Effect of altering GATC sequences in the plasmid ColE1 primer promoter. J. Bacteriol. 172:1762-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polisky, B. 1988. ColE1 replication control circuitry: sense from antisense. Cell 55:929-932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross, W., K. K. Gosink, J. Salomon, K. Igarashi, C. Zou, A. Ishihama, K. Severinov, and R. L. Gourse. 1993. A third recognition element in bacterial promoters: DNA binding by the α subunit of RNA polymerase. Science 262:1407-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozhon, W. M., E. K. Petutschnig, and C. Jonak. 2006. Isolation and characterization of pHW15, a small cryptic plasmid from Rahnella genomospecies 2. Plasmid 56:202-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook, J. F., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed., p. 1.4. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 39.Sarkar, N., G. J. Cao, and C. Jain. 2002. Identification of multicopy suppressors of the pcnB plasmid copy number defect in Escherichia coli. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt, L., and J. Inselburg. 1982. ColE1 copy number mutants. J. Bacteriol. 151:845-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Selzer, G., and J. I. Tomizawa. 1982. Specific cleavage of the p15A primer precursor by ribonuclease H at the origin of DNA replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 79:7082-7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Speck, C., C. Weigel, and W. Messer. 1999. ATP- and ADP-dnaA protein, a molecular switch in gene regulation. EMBO. J. 18:6169-6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Struble, E. B., J. E. Ladner, D. M. Brabazon, and J. P. Marino. 2008. New crystal structures of ColE1 Rom and variants resulting from mutation of a surface exposed residue: implications for RNA-recognition. Proteins 72:761-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Summers, D. K. 1991. The kinetics of plasmid loss. Trends. Biotechnol. 9:273-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Summers, D. K., and D. J. Sherratt. 1984. Multimerization of high copy number plasmids causes instability: CoIE1 encodes a determinant essential for plasmid monomerization and stability. Cell 36:1097-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Summers, D. K., and D. J. Sherratt. 1988. Resolution of ColE1 dimers requires a DNA sequence implicated in the three-dimensional organization of the cer site. EMBO. J. 7:851-858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tomizawa, J., and T. Itoh. 1981. Plasmid ColE1 incompatibility determined by interaction of RNA I with primer transcript. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:6096-6100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomizawa, J., and T. Itoh. 1982. The importance of RNA secondary structure in ColE1 primer formation. Cell 31:575-583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomizawa, J., T. Itoh, G. Selzer, and T. Som. 1981. Inhibition of ColE1 RNA primer formation by a plasmid-specified small RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:1421-1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Typas, A., and R. Hengge. 2005. Differential ability of σs and σ70 of Escherichia coli to utilize promoters containing half or full UP-element sites. Mol. Microbiol. 55:250-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang, Z., L. Xiang, J. Shao, A. Wegrzyn, and G. Wegrzyn. 2006. Effects of the presence of ColE1 plasmid DNA in Escherichia coli on the host cell metabolism. Microb. Cell Fact. 5:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang, Z., Z. Yuan, L. Xiang, J. Shao, and G. Wegrzyn. 2006. tRNA-dependent cleavage of the ColE1 plasmid-encoded RNA I. Microbiology 152:3467-3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu, F., S. Lin-Chao, and S. N. Cohen. 1993. The Escherichia coli pcnB gene promotes adenylylation of antisense RNAI of ColE1-type plasmids in vivo and degradation of RNAI decay intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90:6756-6760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu, F. F., C. Gaggero, and S. N. Cohen. 2002. Polyadenylation can regulate ColE1 type plasmid copy number independently of any effect on RNAI decay by decreasing the interaction of antisense RNAI with its RNAII target. Plasmid 48:49-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zioga, A., J. M. Whichard, S. D. Kotsakis, L. S. Tzouvelekis, E. Tzelepi, and V. Miriagou. 2009. CMY-31 and CMY-36 cephalosporinases encoded by ColE1-like plasmids. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:1256-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zubay, G., D. E. Morse, W. J. Schrenk, and J. H. Miller. 1972. Detection and isolation of the repressor protein for the tryptophan operon of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 69:1100-1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]