Abstract

CD8+ T-cell immunity has been shown to play an important role in the protective immune response against Encephalitozoon cuniculi. Although earlier studies suggest that dendritic cells (DC) are important for the induction of this response, the factors responsible for initiation of the dendritic cell response against this pathogen have not been evaluated. In the current study, we demonstrate that E. cuniculi infection causes strong Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-dependent dendritic cell activation and a blockade of this molecule reduces the ability of DC to prime an antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell response. Pretreatment of DC with anti-TLR4 antibody causes a defect in both in vitro and in vivo CD8+ T-cell priming. These findings, for the first time, emphasize the contribution of TLR4 in the induction of CD8+ T-cell immunity against E. cuniculi infection.

Microsporidia are small obligate intracellular parasites that, until recently, were thought to be protozoans; however, evidence now suggests that they are related to fungi (15, 17). Microsporidia can infect a vast number of species of vertebrates and invertebrates; of the 150 genera of microsporidia, however, only 7 have been found to infect humans (13). Severe infections have been reported predominantly for immunocompromised patients, such as patients with HIV and organ transplant recipients (2, 7, 23, 37). Acute infections have also been reported in travelers and the elderly (26, 27), and there is evidence of colonization of healthy, nonsymptomatic patients (34).

Due to the prevalence of opportunistic microsporidian infections associated with the HIV-AIDS pandemic, recent research has focused on the host's immune response to these pathogens. Early animal studies showed that cellular immunity was necessary to protect SCID mice from a lethal Encephalitozoon cuniculi challenge. Moreover, depletion of CD8+ T cells caused mice to succumb to intraperitoneal (i.p.) E. cuniculi infection (21), and previous studies in our laboratory have shown that cytotoxic lymphocytes play a major role in protection against this effect (20, 21).

Recent reports from our laboratory have demonstrated that dendritic cells (DC) play an important role in the priming of the immune response against E. cuniculi (31, 32). T cells incubated with E. cuniculi-pulsed DC exhibited antigen-specific characteristics, specifically gamma interferon (IFN-γ) production, cytotoxicity, and proliferation (31, 32). In order to mount an immune response against a foreign pathogen, DC must first recognize the pathogen to initiate an appropriate response. One key method of recognition is through Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which were first discovered in Drosophila in response to infection with fungal pathogens (24). However, specific TLR molecules involved in DC activation during E. cuniculi infection have not been identified previously. We evaluated the upregulation of specific molecules involved in activation of the DC response after E. cuniculi infection. Different TLR molecules were tested, and TLR4 expression was found to be essential for induction of the optimal CD8+ T-cell response by these cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Six- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). The animals were housed under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved conditions at the Animal Research Facility at The George Washington University (Washington, DC).

Parasites and infection.

A rabbit isolate of E. cuniculi (genotype II), kindly provided by L. Weiss (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY), was used throughout this study. The parasites were maintained by continuous passage in rabbit kidney (RK-13) cells, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). The RK-13 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT). Mice were infected via the intraperitoneal (i.p.) route with 2 × 107 spores/mouse. In vitro stimulation was performed using irradiated parasites (220 krads).

TLR expression by dendritic cells.

Expression of TLR2, -4, and -9 by dendritic cells was assessed on various days postinfection (p.i.) (2, 4, and 6 p.i.) by performing a phenotypic analysis. Briefly, spleens were harvested, and this was followed by enzymatic (collagenase D and DNase I) and mechanical, disruption, allowing for DC separation. The cell suspension was labeled for CD11c, NK1.1, CD19, and TLR2 (eBioscience, San Diego CA) or TLR4 (BD Bioscience, San Jose CA) expression. Intracellular TLR9 expression was determined after permeabilization and fixation with FoxP3 staining buffer (eBioscience) and intracellular staining with anti-TLR9 antibody (eBioscience). Cells were acquired with a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

TLR2, -4, and -9 messages were detected by real-time PCR according to standard protocol in our laboratory (45). Splenic DC were isolated according to a previously described protocol (45). Briefly, spleens were harvested as described above. A cell suspension was then labeled with anti-CD11c biotin-conjugated antibodies (eBioscience) and positively selected by magnetic purification using the manufacturer's protocol (Stem Cell Technology, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). Positively selected cells were then labeled, and CD11c+ CD19− NK1.1− DC were purified using a cell sorter (FACSAria; BD Biosciences). RNA was isolated with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions and reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out using an MyiQ single-color real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules CA) and each of the following primers at a concentration of 200 nM: 5mTLR2 (5′-GCCACCATTTCCACGGACT-3′), 3mTLR2 (5′-ACCTGGCTGGTTTACACGTC-3′), 5mTLR4 (5′-GTGCCAGAGACATTGCAGAA-3′), 3mTLR4 (5′-GGCTTCCTCTTGGCCTGG-3′), 5mTLR9 (5′-ACTGAGCACCCCTGCTTCTA-3′), 3mTLR9 (5′-AGATTAGTCAGCGGCAGGAA-3′), 5mβ-actin (5′-AGAGGGAAATCGTGCGTGAC-3′), and 3mβ-actin (5′-CAATTAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′). Amplification was performed with SYBR GreenER qPCR Supermix (Invitrogen) for TLR2 and TLR4 or with iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) for TLR9 and consisted of 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60.5°C for 1 min, followed by melt curve analysis. A baseline value of 1.0 was established using DC from uninfected mice.

Detection of intracellular IL-12.

To assess interleukin-12 (IL-12) production, splenic DC were isolated as described above. DC were plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 DC/well and incubated with monensin (BD Biosciences) overnight. On the following day, cells were stained for surface markers using anti-CD11c, anti-NK1.1, and anti-CD19 antibodies. The cells were then fixed and permeabilized using a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience) according to the manufacturer's instructions and were labeled with anti-IL-12p40 antibody (eBioscience).

Immunoprecipitation.

Splenic dendritic cells from naïve and day 4 infected mice were isolated as described above. Purified DC were then incubated with lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA) for 20 min on ice. Supernatants were collected following centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min and incubated with myeloid differentiating factor 88 (MyD88) F-19 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz CA) for 1 h and then overnight with protein A/G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The immunoprecipitated complex was separated on a precast 4 to 15% Tris-HCl gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad). After overnight incubation with 5% dry milk in TBST (Tris-NaCl with 0.05% Tween 20), membranes were incubated with anti-mouse TLR4 antibody (1:4,000; eBioscience) for 1 h and then with anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:160,000; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The hybridized bands were visualized by chemiluminescence using an ECL kit (Pierce).

Expression of costimulatory molecules.

DC were purified as described above and plated at a concentration of 5 × 104 cells/well in a 96-well plate. The cells were then incubated with 40 μg/ml of anti-TLR4 (MD-2) antibody (BD Biosciences) or rat IgG2a isotype control antibody (eBioscience) for 1.5 h before irradiated E. cuniculi was added (2.5 × 105 cells/wells). Following overnight incubation, cells were harvested and labeled with phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-CD80, -CD86, or -major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antibodies (eBioscience). Data were acquired with a FACSAria (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed with FlowJo software.

Measurement of CD8+ T-cell response.

DC were isolated, treated with anti-TLR4 antibody, and incubated with irradiated E. cuniculi as described above. The next day, splenic TCRβ+ T cells were isolated from naïve mice and added to the culture (5 × 105 cells/well). After 96 h of incubation, CD8+ T-cell activation was examined using Ki67 and IFN-γ intracellular staining. Briefly, monensin was added to the culture overnight according to the manufacturer's protocol. Labeling of cells with anti-CD8β and anti-CD25 was followed by permeabilization using a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences). Cells were then labeled with anti-IFN-γ and anti-Ki67. Cells were acquired with a FACSCalibur and analyzed with Flowjo software.

Adoptive transfer of E. cuniculi-pulsed DC.

DC were isolated, treated with anti-TLR4 antibody, and incubated with irradiated E. cuniculi as described above. The next day, 4 × 105 to 5 × 105 cells were adoptively transferred to naïve C57BL/6 mice via injection into the tail vein. At day 6 posttransfer, spleens were harvested, and cell suspensions were prepared and incubated overnight with irradiated E. cuniculi spores in the presence of monensin. The next morning, cells were labeled for CD8 and CD25 expression. After permeabilization as described above, cells were labeled with anti-IFN-γ and -KI67 antibodies. Cells were acquired with a FACSCalibur and were analyzed with Flowjo software.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using a two-tailed Student t test (33).

RESULTS

Splenic dendritic cell response following E. cuniculi infection.

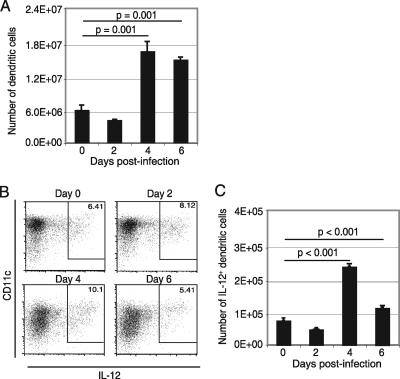

DC have been shown to be the main antigen-presenting cells during infection (1) and can produce IL-12 in response to various pathogens (25). Previous studies from our laboratory have reported that aging mice with a defect in DC function are unable to prime an optimal T-cell immunity against E. cuniculi infection (31). Splenic DC were analyzed at different time points after E. cuniculi infection (days 2, 4, and 6 p.i.), and IL-12 expression was assessed by intracellular staining. The frequency of total DC as well as IL-12-producing DC peaked at day 4 p.i. and started to decline by day 6 (Fig. 1 A to C). The early increase in the frequency of IL-12-producing DC in response to E. cuniculi infection demonstrates that these cells play an important role in initiation of the immune response against E. cuniculi.

FIG. 1.

Splenic DC response after E. cuniculi infection. C57BL/6 mice were infected i.p. with 2 × 107 E. cuniculi spores. At different time points p.i. (days 2, 4, and 6), animals were sacrificed, spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were prepared by using collagenase D and DNase I digestion. Cells were directly labeled for CD11c, CD19, and NK1.1 (A) or were incubated overnight with monensin before intracellular IL-12 staining (B and C). Experiments were performed twice, and the data are representative of the results of one experiment.

E. cuniculi infection induces TLR4 expression by splenic DC.

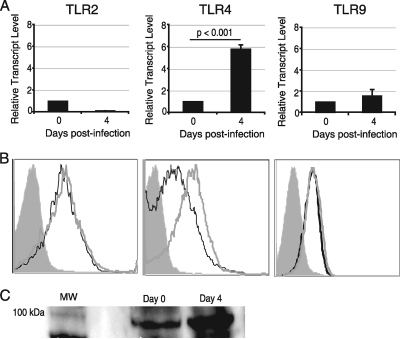

DC are known to initiate an immune response through recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) by Toll-like receptors. Microsporidia consist of a chitinous spore wall that contains O-linked glycans similar in structure to those found in the cell wall of Candida albicans (38), which has been shown to signal through TLR2 and -4 (3, 14). Additionally, microsporidia contain glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchors analogous to those found in Trypanosome cruzi, Plasmodium falciparum, and Toxoplasma gondii, all of which activate TLR2 and/or TLR4 (4, 8, 22, 28). TLR2, -4, and -9 expression was measured to determine if these molecules are involved in activation of DC during E. cuniculi infection. Spleens were harvested from infected animals at day 4 p.i., DC were purified, and the levels of mRNA transcripts for TLR2, -4, and -9 were determined. As shown in Fig. 2 A, significant upregulation of the TLR4 message was observed at day 4 p.i. Conversely, no significant increases in the messages for other two TLRs (TLR2 and TLR9) in response to E. cuniculi infection were noted (Fig. 2A). To further determine the TLR molecules involved in DC activation, the expression of these molecules by DC was measured by a flow cytometry assay. As shown in Fig. 2B, there was no change in the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for either TLR2 or TLR9 following infection. However, a significant increase in the TLR4 MFI at day 4 p.i. (P = 0.0001) was noted. These observations suggest that splenic DC upregulate TLR4 in response to E. cuniculi infection.

FIG. 2.

TLR4 upregulation after E. cuniculi infection is MyD88 dependent. Splenic DC were isolated at day 4 p.i. and analyzed for TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 expression. TLR mRNA expression was normalized using β-actin mRNA levels (A). Relative expression was measured using the mean for each group and the formula for the relative transcript level:  × 1,000 where CT is the cycle threshold. DC were labeled with CD11c, CD19, NK1.1, and either TLR2, TLR4, or TLR9 antibodies (B). Splenic DC were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-MyD88, and the complex was then immunoblotted for TLR4 (C). Lane MW contains a protein ladder. Experiments were performed twice, and the data are representative of two experiments.

× 1,000 where CT is the cycle threshold. DC were labeled with CD11c, CD19, NK1.1, and either TLR2, TLR4, or TLR9 antibodies (B). Splenic DC were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-MyD88, and the complex was then immunoblotted for TLR4 (C). Lane MW contains a protein ladder. Experiments were performed twice, and the data are representative of two experiments.

TLR4 expression is associated with MyD88.

Since activation of TLR4 by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulation has been shown to act in both myeloid differentiating factor 88 (MyD88)-dependent and MyD88-independent pathways (12, 19), we sought to determine the involvement of MyD88 during E. cuniculi infection. Splenic DC were isolated at day 4 p.i., and the cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with anti-MyD88 antibody and subsequently immunoblotted with anti-TLR4 antibody. As shown in Fig. 2C, DC from infected mice exhibited an increase in TLR4 protein interacting with MyD88 (Fig. 2C), suggesting that TLR4 signaling in response to E. cuniculi infection is MyD88 dependent.

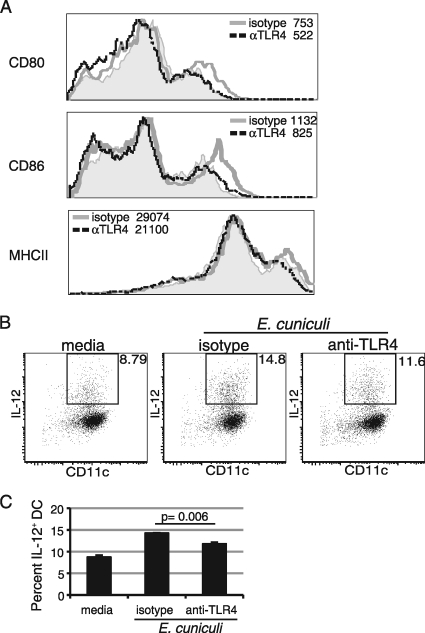

In vitro TLR4 blockade reduces the expression of costimulatory molecules on DC.

Upregulation of costimulatory molecules and antigen presentation by DC are essential for induction of the optimal T-cell response (5). To further assess the role of TLR4 in the DC function, an in vitro blocking assay was performed. Splenic DC from naïve mice were isolated and incubated with anti-TLR4 antibody or an isotype control for 1.5 h and then pulsed overnight with E. cuniculi spores. Subsequently, the cells were harvested, and the expression of costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, and MHC class II) was measured by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 3 A, blocking TLR4 prior to E. cuniculi stimulation prevented upregulation of all of the costimulatory molecules mentioned above. To ensure that the stimulation through TLR4 was not due to LPS contamination, polymyxin B (an antibiotic that binds to and neutralizes LPS) was added to DC cultures prior to the E. cuniculi pulse. Addition of polymyxin B to the cultures did not alter the expression of costimulatory molecules, ruling out the possibility that LPS was involved (data not shown). These results demonstrate that TLR4 blockade prevents upregulation of costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, and MHC class II) on DC, which most likely impairs their functions.

FIG. 3.

Costimulatory molecule expression and IL-12 production are TLR4 dependent. Splenic DC were purified from naïve mice, plated, and incubated with anti-TLR4 (αTLR4) or isotype control antibody. Cells were stimulated overnight with irradiated E. cuniculi and stained for CD80, CD86, or MHC class II expression (A). Unstimulated cells are represented by the shaded histogram. The mean fluorescence intensity is presented next to each antibody treatment. IL-12 production by splenic DC was measured by intracellular staining after overnight treatment with monensin (B and C). Experiments were carried out twice, and the data are representative of one experiment.

Reduced IL-12 production by DC after anti-TLR4 treatment.

DC are known to be an important source of IL-12, a cytokine reported to play an important role in the immune response against E. cuniculi (35). Moreover, data shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate that there was an increase in the frequency of IL-12-producing DC in response to E. cuniculi infection. Next, we determined the effect of TLR4 blockade on IL-12 production by DC. Splenic DC were purified and treated with anti-mouse TLR4 antibody or an isotype control, as described above. Cells were pulsed with E. cuniculi overnight, and IL-12 was detected by intracellular staining the next day. As shown in Fig. 3B, the frequency of IL-12+ DC was significantly reduced after anti-TLR4 treatment compared to the results for cells treated with the isotype control (P = 0.006).

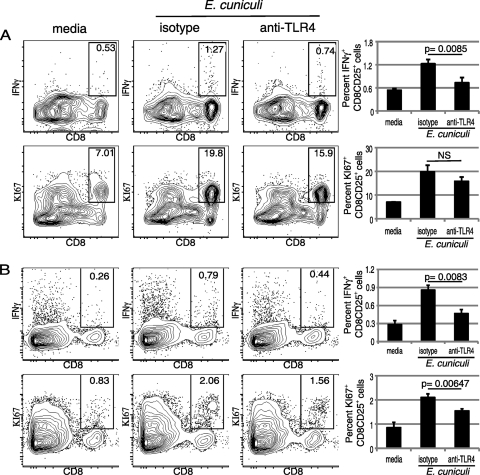

Inhibition of TLR4 signaling suppresses effective T-cell priming.

The data presented above demonstrate that TLR4 blockade affects the upregulation of costimulatory molecules known to be critical for T-cell priming (5). To study the downstream effect of this blockade, we determined if prior treatment with anti-TLR4 antibody inhibits the ability of DC to initiate an optimal CD8+ T-cell response against E. cuniculi infection. Purified DC were isolated and treated with anti-mouse TLR4 or isotype control antibody, as described above. Following overnight stimulation with E. cuniculi spores, T cells were added to the cultures, and 96 h later, the response was measured by measuring IFN-γ, CD25, and Ki67 expression. As expected, an increase in the frequency of CD25+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells was observed when DC were incubated with the isotype control (Fig. 4 A). Conversely, prior treatment with TLR4 antibody significantly reduced the ability of these cells to prime the CD8+ T-cell response compared to that of cells treated with the isotype control (P = 0.0085) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, there was no significant increase in the percentage of CD8+ T cells (CD25+ Ki67+) when DC were treated with antibody to TLR4. These observations suggest that this molecule is important for priming the CD8+ T-cell immunity against E. cuniculi.

FIG. 4.

Downregulated CD8+ T-cell response after TLR4 blockade. Splenic DC purified from naïve mice were plated, incubated with either anti-TLR4 antibody or anti-rat IgG2a antibody, and pulsed overnight with irradiated E. cuniculi. For the in vitro assay, the next day, purified splenic CD8β+ T cells were added to cultures (A). After 96 h of incubation, cells were harvested and labeled for CD8β, Ki67, IFN-γ, and CD25. For the in vivo assay, E. cuniculi-pulsed DC treated with anti-TLR4 were adoptively transferred intravenously to naïve recipients (B). Six days posttransfer, spleens were harvested, and single-cell suspensions were prepared. After overnight incubation with monensin, cells were labeled for CD8β, KI67, IFN-γ, and CD25. Cells displayed in all dot plots were gated on CD25+ cells. Experiments were performed twice, and the data are representative of the results of one experiment. NS, not significant.

To further establish the importance of TLR4 signaling in the priming of the CD8+ T-cell response, adoptive transfer studies were performed. Anti-TLR4 antibody-treated DC were pulsed with E. cuniculi spores in vitro and subsequently transferred to naïve syngeneic mice. At day 6 posttransfer, the recipient animals were sacrificed, and splenic CD8 T cells were evaluated for IFN-γ, CD25, and KI67 expression. As shown in Fig. 4B, recipient animals that received anti-TLR4 antibody-treated DC exhibited reduced T-cell priming compared to control animals, which received control antibody-treated DC. A significantly lower percentage of IFN-γ-producing cells was observed for the CD25+ CD8+ T-cell population of these animals (P = 0.0083). Similarly, the frequency of proliferating CD25+ CD8+ T cells was significantly reduced in the mice that received anti-TLR4 antibody-treated DC (P = 0.00647) (Fig. 4B). These findings further establish that TLR4 upregulation by DC is essential for the CD8+ T-cell response against E. cuniculi infection.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that TLR4 plays a major role in activation of splenic DC during E. cuniculi infection, which results in initiation of a protective immune response. While increases in TLR4 transcript and surface protein expression on splenic DC were observed, the expression of other important TLRs (TLR2 and TLR9) remained the same. The data presented in this paper demonstrate that TLR4 expressed by DC signals through the MyD88 adapter molecule and that in vitro blockade of this receptor reduces the expression of MHC class II costimulatory molecules, as well as IL-12p40 production by these cells. This significantly decreases the ability of DC to prime an optimal T-cell response against E. cuniculi. These results emphasize the role of the TLR4 molecule in initiating immunity against this pathogen.

TLR signaling on DC is involved in the immune responses to numerous pathogens (18, 36, 39). Specifically, TLR4 has been demonstrated to be one of the molecules stimulated in several infectious diseases (3, 6, 8-10). Additionally, it has been shown that TLR polymorphism increases susceptibility to certain diseases. For instance, Mockenhaupt et al. found that African children with a TLR4 polymorphism were more susceptible to severe malaria infections, which showed the importance of this molecule in initiation of the immune response against P. falciparum (28). Furthermore, it has been reported that a mutation in TLR4 increased the risk of invasive meningococcal disease in infants less than 12 months old (10).

The TLR molecules involved in the priming of the T-cell response during E. cuniculi infection have not been well described. This pathogen has been reported to induce a less robust immune response in TLR9−/− mice following oral infection (16). The altered immune response in these mutant animals was attributed to enhancement of the regulatory T-cell response by commensal DNA in the intestinal tissues and/or to the inability of the mice to generate optimal effector T-cell immunity (16). Recent in vitro studies have demonstrated that E. cuniculi infection upregulates the TLR2 message in human monocyte-derived macrophages (11). However, no increase in the TLR4 message was observed in this study (11). Although a role for TLR2 in activation of DC during E. cuniculi was not observed in our study, it is possible that TLR2 may be involved in activation of other antigen-presenting cells, like macrophages, as reported in previous studies (3). Alternatively, it is very likely that TLRs involved in the responses to microsporidian infections in human and mouse macrophages or DC are different.

In the present study, we demonstrated that TLR4 signaling is important for generation of robust CD8+ T-cell immunity against E. cuniculi. Interestingly, TLR4 blockade reduces IL-12 production by E. cuniculi-pulsed DC. A role for IL-12 in induction of short-lived effector CD8+ T cells against intracellular parasitic infection has been demonstrated (40). Thus, reduced IL-12 production by DC due to TLR4 blockade may contribute to the inability of these cells to induce an optimal CD8+ T-cell response.

As E. cuniculi and other microsporidia are an ever-increasing problem for immunocompromised patients, an effective vaccination against these pathogens would be advantageous. This study demonstrated that TLR4 is involved in the priming of CD8+ T cells, which have been shown to be critical for protection against E. cuniculi infection (21, 29, 30). The novel feature of our observations is that they demonstrate the importance of TLR4 in elicitation of CD8+ T-cell immunity against E. cuniculi infection, which has been reported to be critical for protection of hosts against this pathogen. These findings suggest the need to target the TLR4 molecule for developing immunotherapeutic reagents against E. cuniculi and other microsporidian species, such as Enterocytozoon bieneusi, which cause severe complications in HIV-infected individuals.

Acknowledgments

We thank Teresa Hawley for her help with flow cytometry.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grant AI 043693 awarded to I.A.K.

Editor: J. L. Flynn

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banchereau, J., and R. M. Steinman. 1998. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature 392:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaugerie, L., M. F. Teilhac, A. M. Deluol, J. Fritsch, P. M. Girard, W. Rozenbaum, Y. Le Quintrec, and F. P. Chatelet. 1992. Cholangiopathy associated with Microsporidia infection of the common bile duct mucosa in a patient with HIV infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 117:401-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasi, E., A. Mucci, R. Neglia, F. Pezzini, B. Colombari, D. Radzioch, A. Cossarizza, E. Lugli, G. Volpini, G. Del Giudice, and S. Peppoloni. 2005. Biological importance of the two Toll-like receptors, TLR2 and TLR4, in macrophage response to infection with Candida albicans. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 44:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campos, M. A., I. C. Almeida, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, E. P. Valente, D. O. Procopio, L. R. Travassos, J. A. Smith, D. T. Golenbock, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Activation of Toll-like receptor-2 by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from a protozoan parasite. J. Immunol. 167:416-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chai, J. G., S. Vendetti, I. Bartok, D. Schoendorf, K. Takacs, J. Elliott, R. Lechler, and J. Dyson. 1999. Critical role of costimulation in the activation of naive antigen-specific TCR transgenic CD8+ T cells in vitro. J. Immunol. 163:1298-1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, X. M., S. P. O'Hara, J. B. Nelson, P. L. Splinter, A. J. Small, P. S. Tietz, A. H. Limper, and N. F. LaRusso. 2005. Multiple TLRs are expressed in human cholangiocytes and mediate host epithelial defense responses to Cryptosporidium parvum via activation of NF-kappaB. J. Immunol. 175:7447-7456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curry, A., H. S. Mudhar, S. Dewan, E. U. Canning, and B. E. Wagner. 2007. A case of bilateral microsporidial keratitis from Bangladesh—infection by an insect parasite from the genus Nosema. J. Med. Microbiol. 56:1250-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debierre-Grockiego, F., M. A. Campos, N. Azzouz, J. Schmidt, U. Bieker, M. G. Resende, D. S. Mansur, R. Weingart, R. R. Schmidt, D. T. Golenbock, R. T. Gazzinelli, and R. T. Schwarz. 2007. Activation of TLR2 and TLR4 by glycosylphosphatidylinositols derived from Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 179:1129-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenbarth, S. C., D. A. Piggott, J. W. Huleatt, I. Visintin, C. A. Herrick, and K. Bottomly. 2002. Lipopolysaccharide-enhanced, Toll-like receptor 4-dependent T helper cell type 2 responses to inhaled antigen. J. Exp. Med. 196:1645-1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faber, J., C. U. Meyer, C. Gemmer, A. Russo, A. Finn, C. Murdoch, W. Zenz, C. Mannhalter, B. U. Zabel, H. J. Schmitt, P. Habermehl, F. Zepp, and M. Knuf. 2006. Human Toll-like receptor 4 mutations are associated with susceptibility to invasive meningococcal disease in infancy. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 25:80-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer, J., C. Suire, and H. Hale-Donze. 2008. Toll-like receptor 2 recognition of the microsporidia Encephalitozoon spp. induces nuclear translocation of NF-kappaB and subsequent inflammatory responses. Infect. Immun. 76:4737-4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fitzgerald, K. A., D. C. Rowe, B. J. Barnes, D. R. Caffrey, A. Visintin, E. Latz, B. Monks, P. M. Pitha, and D. T. Golenbock. 2003. LPS-TLR4 signaling to IRF-3/7 and NF-kappaB involves the Toll adapters TRAM and TRIF. J. Exp. Med. 198:1043-1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franzen, C., and A. Muller. 2001. Microsporidiosis: human diseases and diagnosis. Microbes Infect. 3:389-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gil, M. L., and D. Gozalbo. 2009. Role of Toll-like receptors in systemic Candida albicans infections. Front. Biosci. 14:570-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill, E. E., and N. M. Fast. 2006. Assessing the microsporidia-fungi relationship: combined phylogenetic analysis of eight genes. Gene 375:103-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall, J. A., N. Bouladoux, C. M. Sun, E. A. Wohlfert, R. B. Blank, Q. Zhu, M. E. Grigg, J. A. Berzofsky, and Y. Belkaid. 2008. Commensal DNA limits regulatory T cell conversion and is a natural adjuvant of intestinal immune responses. Immunity 29:637-649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirt, R. P., J. M. Logsdon, Jr., B. Healy, M. W. Dorey, W. F. Doolittle, and T. M. Embley. 1999. Microsporidia are related to Fungi: evidence from the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II and other proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:580-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoshino, K., T. Kaisho, T. Iwabe, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2002. Differential involvement of IFN-beta in Toll-like receptor-stimulated dendritic cell activation. Int. Immunol. 14:1225-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawai, T., O. Takeuchi, T. Fujita, J. Inoue, P. F. Muhlradt, S. Sato, K. Hoshino, and S. Akira. 2001. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates the MyD88-independent pathway and results in activation of IFN-regulatory factor 3 and the expression of a subset of lipopolysaccharide-inducible genes. J. Immunol. 167:5887-5894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan, I. A., and M. Moretto. 1999. Role of gamma interferon in cellular immune response against murine Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. Infect. Immun. 67:1887-1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan, I. A., J. D. Schwartzman, L. H. Kasper, and M. Moretto. 1999. CD8+ CTLs are essential for protective immunity against Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. J. Immunol. 162:6086-6091. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnegowda, G., A. M. Hajjar, J. Zhu, E. J. Douglass, S. Uematsu, S. Akira, A. S. Woods, and D. C. Gowda. 2005. Induction of proinflammatory responses in macrophages by the glycosylphosphatidylinositols of Plasmodium falciparum: cell signaling receptors, glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) structural requirement, and regulation of GPI activity. J. Biol. Chem. 280:8606-8616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanternier, F., D. Boutboul, J. Menotti, M. O. Chandesris, C. Sarfati, M. F. Mamzer Bruneel, Y. Calmus, F. Mechai, J. P. Viard, M. Lecuit, M. E. Bougnoux, and O. Lortholary. 2009. Microsporidiosis in solid organ transplant recipients: two Enterocytozoon bieneusi cases and review. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 11:83-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemaitre, B., E. Nicolas, L. Michaut, J. M. Reichhart, and J. A. Hoffmann. 1996. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell 86:973-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, C. H., Y. T. Fan, A. Dias, L. Esper, R. A. Corn, A. Bafica, F. S. Machado, and J. Aliberti. 2006. Cutting edge: dendritic cells are essential for in vivo IL-12 production and development of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii infection in mice. J. Immunol. 177:31-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopez-Velez, R., M. C. Turrientes, C. Garron, P. Montilla, R. Navajas, S. Fenoy, and C. del Aguila. 1999. Microsporidiosis in travelers with diarrhea from the tropics. J. Travel Med. 6:223-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lores, B., I. Lopez-Miragaya, C. Arias, S. Fenoy, J. Torres, and C. del Aguila. 2002. Intestinal microsporidiosis due to Enterocytozoon bieneusi in elderly human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients from Vigo, Spain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:918-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mockenhaupt, F. P., J. P. Cramer, L. Hamann, M. S. Stegemann, J. Eckert, N. R. Oh, R. N. Otchwemah, E. Dietz, S. Ehrhardt, N. W. Schroder, U. Bienzle, and R. R. Schumann. 2006. Toll-like receptor (TLR) polymorphisms in African children: common TLR-4 variants predispose to severe malaria. J. Commun. Dis. 38:230-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moretto, M., L. Casciotti, B. Durell, and I. A. Khan. 2000. Lack of CD4+ T cells does not affect induction of CD8+ T-cell immunity against Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. Infect. Immun. 68:6223-6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moretto, M., L. M. Weiss, and I. A. Khan. 2004. Induction of a rapid and strong antigen-specific intraepithelial lymphocyte response during oral Encephalitozoon cuniculi infection. J. Immunol. 172:4402-4409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moretto, M. M., E. M. Lawlor, and I. A. Khan. 2008. Aging mice exhibit a functional defect in mucosal dendritic cell response against an intracellular pathogen. J. Immunol. 181:7977-7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moretto, M. M., L. M. Weiss, C. L. Combe, and I. A. Khan. 2007. IFN-gamma-producing dendritic cells are important for priming of gut intraepithelial lymphocyte response against intracellular parasitic infection. J. Immunol. 179:2485-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neter, J., W. Wasserman, and M. H. Kutner. 1985. Applied linear statistical models, 2nd ed. Irwin, Homewood, IL.

- 34.Nkinin, S. W., T. Asonganyi, E. S. Didier, and E. S. Kaneshiro. 2007. Microsporidian infection is prevalent in healthy people in Cameroon. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:2841-2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salat, J., B. Sak, T. Le, and J. Kopecky. 2004. Susceptibility of IFN-gamma or IL-12 knock-out and SCID mice to infection with two microsporidian species, Encephalitozoon cuniculi and E. intestinalis. Folia Parasitol. (Praha) 51:275-282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato, A., M. M. Linehan, and A. Iwasaki. 2006. Dual recognition of herpes simplex viruses by TLR2 and TLR9 in dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:17343-17348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stark, D., S. van Hal, J. Barratt, J. Ellis, D. Marriott, and J. Harkness. 2009. Limited genetic diversity among genotypes of Enterocytozoon bieneusi strains isolated from HIV-infected patients from Sydney, Australia. J. Med. Microbiol. 58:355-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taupin, V., E. Garenaux, M. Mazet, E. Maes, H. Denise, G. Prensier, C. P. Vivares, Y. Guerardel, and G. Metenier. 2007. Major O-glycans in the spores of two microsporidian parasites are represented by unbranched manno-oligosaccharides containing alpha-1,2 linkages. Glycobiology 17:56-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, Z. Y., D. Yang, Q. Chen, C. A. Leifer, D. M. Segal, S. B. Su, R. R. Caspi, Z. O. Howard, and J. J. Oppenheim. 2006. Induction of dendritic cell maturation by pertussis toxin and its B subunit differentially initiate Toll-like receptor 4-dependent signal transduction pathways. Exp. Hematol. 34:1115-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yap, I. K., J. V. Li, J. Saric, F. P. Martin, H. Davies, Y. Wang, I. D. Wilson, J. K. Nicholson, J. Utzinger, J. R. Marchesi, and E. Holmes. 2008. Metabonomic and microbiological analysis of the dynamic effect of vancomycin-induced gut microbiota modification in the mouse. J. Proteome Res. 7:3718-3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]