Abstract

Enterocin X, composed of two antibacterial peptides (Xα and Xβ), is a novel class IIb bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium KU-B5. When combined, Xα and Xβ display variably enhanced or reduced antibacterial activity toward a panel of indicators compared to each peptide individually. In E. faecium strains that produce enterocins A and B, such as KU-B5, only one additional bacteriocin had previously been known.

Bacteriocins are gene-encoded antibacterial peptides and proteins. Because of their natural ability to preserve food, they are of particular interest to researchers in the food industry. Bacteriocins are grouped into three main classes according to their physical properties and compositions (11, 12). Of these, class IIb bacteriocins are thermostable non-lanthionine-containing two-peptide bacteriocins whose full antibacterial activity requires the interaction of two complementary peptides (8, 19). Therefore, two-peptide bacteriocins are considered to function together as one antibacterial entity (14).

Enterocins A and B, first discovered and identified about 12 years ago (2, 3), are frequently present in Enterococcus faecium strains from various sources (3, 5, 6, 9, 13, 16). So far, no other bacteriocins have been identified in these strains, except the enterocin P-like bacteriocin from E. faecium JCM 5804T (18). Here, we describe the characterization and genetic identification of enterocin X in E. faecium KU-B5. Enterocin X (identified after the enterocin P-like bacteriocin was discovered) is a newly found class IIb bacteriocin in E. faecium strains that produce enterocins A and B.

Enterocins A and B in Enterococcus faecium KU-B5.

E. faecium KU-B5, a thermotolerant lactic acid bacterium screened from sugar apples in Thailand, has the ability to multiply and express antibacterial activity across a wide range of temperatures (20 to 43°C). Bacteriocin activity was tested by the critical dilution spot-on-lawn method (21) and expressed in activity units (AU) per milliliter. The strongest antibacterial activity of E. faecium was observed when it was cultured at 37°C in de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) broth, with a wide spectrum of targets, including Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Bacillus, and Listeria (Table 1). Since enterocins A and B are frequently found in many antibacterial E. faecium strains, we initially examined the enterocin A- and B-encoding genes in E. faecium KU-B5 by using PCR with specific primers (5′-TGTACGAAGTGCATTCTCAA-3′ and 5′-TATTAAAGGACCGGGATCTA-3′ for enterocin A; 5′-ACTCTAAAAGGAGCGAGTTT-3′ and 5′-AGAGCTGGGGATGAAATATT-3′ for enterocin B). As expected, these genes were detected in genomic DNA of E. faecium KU-B5. However, the pooled activities from enterocins A and B could not explain the total activities in the culture supernatant of E. faecium KU-B5, such as activity toward Bacillus circulans JCM 2504T (Table 1). On the other hand, the gene encoding the enterocin P-like bacteriocin (18) was not detected in E. faecium KU-B5. Thus, we assumed that other bacteriocins exist in E. faecium KU-B5, and we obtained the purified bacteriocins, as described below.

TABLE 1.

Antibacterial spectra of bacteriocins found in Enterococcus faecium KU-B5

| Indicator strain | Antibacterial activity in culture supernatant (AU/ml) | MIC (nM)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EntA | EntB | EntXα | EntXβ | EntXα+Xβb | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis JCM 5803T | 1,600 | 64.7 | 86.9 | 50.8 | 813 | 203e (0.5; 8.0) |

| Enterococcus faecalis OU510 | 1,600 | 32.3 | 174 | 102 | 813 | 406e (0.5; 4.0) |

| Enterococcus faecium JCM 5804T | 200 | NAf | NA | NA | NA | 813c (>16; >16) |

| Enterococcus faecium TUA 1344L | 3,200 | 129 | 43.4 | 50.8 | 813 | 50.8e (2.0; 32) |

| Enterococcus faecium KU-B5 | 100 | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1,630c (>8.0; >8.0) |

| Enterococcus hirae ATCC 10541 | 6,400 | 129 | 5.44 | 50.8 | 406 | 50.8e (2.0; 16) |

| Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 14917T | 3,200 | 259 | 86.9 | 102 | 813 | 203e (1.0; 8.0) |

| Lactobacillus sakei subsp. sakei JCM 1157T | 12,800 | 16.2 | 5.44 | 50.8 | 102 | 203e (0.5; 1.0) |

| Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris ATCC 19257T | 6,400 | 4,140 | NA | 813 | NA | 12.7c (130; >1,020) |

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus ATCC 12600T | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Streptococcus salivarius JCM 5707T | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bacillus cereus JCM 2152T | 400 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bacillus circulans JCM 2504T | 6,400 | NA | NA | NA | 3,250 | 813c (>16; 8.0) |

| Bacillus coagulans JCM 2257T | 200 | 8,280 | 89,000 | NA | 3,250 | 1,630c (>8.0; 4.0) |

| Bacillus subtilis JCM 1465T | 400 | 4,140 | 44,500 | NA | 3,250 | 1,630c (>8.0; 4.0) |

| Listeria innocua ATCC 33090T | 400 | 1,040 | NA | 25.4 | 3,250 | 406d (0.13; 16) |

| Micrococcus luteus NBRC 12708 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

MICs of enterocin A (EntA), enterocin B (EntB), enterocin Xα (EntXα), enterocin Xβ (EntXβ), and the combination of enterocins Xα and Xβ (EntXα+Xβ), determined by the spot-on-lawn method (21).

The MICs of EntXα+Xβ represent the antibacterial activities of the combination of equimolar amounts of enterocin Xα and enterocin Xβ against a panel of indicator bacteria. The values in parentheses represent two MIC ratios: EntXα/(1/2 × EntXα+Xβ) and EntXβ/(1/2 × EntXα+Xβ). The activity change of at least 4-fold is considered significant. For EntXα and EntXβ, the enterocin with higher activity against a particular bacterium (i.e., lower MIC) is used to evaluate the extent in activity change (numbers in boldface type in parentheses) after combination.

The activity of EntXα+Xβ was enhanced compared with that of EntXα or EntXβ.

The activity of EntXα+Xβ was reduced compared with that of EntXα or EntXβ.

The activity of EntXα+Xβ was not significantly changed compared with that of EntXα or EntXβ.

NA, no activity detected at the highest concentration of applied EntA (132,500 nM), EntB (89,000 nM), EntXα (6,500 nM), EntXβ (6,500 nM), or EntXα+Xβ (6,500 nM).

Isolation of antibacterial substances and identification of a novel two-peptide bacteriocin.

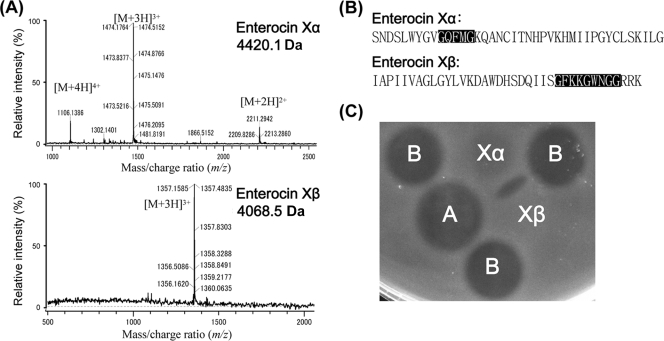

The supernatant from an overnight culture (at 37°C in MRS broth without shaking) of E. faecium KU-B5 was collected and subjected to a three-step purification process (10), including cation-exchange chromatography (SP Sepharose Fast Flow column), hydrophobic interaction (Sep-Pak Plus cartridge), and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; Resource RPC 3-ml column) in sequence. Four antimicrobial substances were separated; of these, the 4,830.5- and 5,463.8-Da substances were identified according to their sizes as enterocins A and B, respectively. The other two substances (4,420.1 Da and 4,068.5 Da; pI = 8.83 and 10.32, respectively) were 40- and 37-residue cationic peptides, respectively, without posttranslationally modified bases and displayed synergistic antibacterial activity on the indicator lawn (Fig. 1). A database search for sequence similarity revealed no known bacteriocins; however, in their sequences, we detected the GXXXG motifs, which are suggested to be involved in helix-helix interaction (19) and often found in most two-peptide bacteriocins (14) (Fig. 1). The characteristics mentioned above fit typical features of two-peptide bacteriocins (17); therefore, they were named enterocin Xα (4,420.1 Da) and enterocin Xβ (4,068.5 Da), together comprising enterocin X.

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of enterocin Xα and enterocin Xβ. (A) Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry spectra of purified enterocins Xα and Xβ. The observed molecular sizes are indicated in each panel. (B) Amino acid sequences of enterocins Xα and Xβ from N to C termini. The GXXXG motifs are shaded in black. (C) Synergism assay for pairs of enterocins A, B, Xα, and Xβ. Enterocins with the appropriate dilution were spotted onto the indicator lawn of Enterococcus faecium TUA 1344L. The additional inhibition zone that appears between enterocins Xα and Xβ depicts the synergic antibacterial activity.

Individual enterocins Xα and Xβ exhibited narrow-spectrum weak-to-moderate antibacterial activities, similar to those of plantaricin E/F and plantaricin J/K (1), but enterocin Xα had stronger antilisterial activity (Table 1). Synergistic antibacterial activity was observed when enterocins Xα and Xβ were assessed on the indicator lawn (Fig. 1). However, when they were mixed beforehand in equimolar amounts, the combined antibacterial activity was not uniformly enhanced toward a panel of indicator bacteria, with activity 0.13- to 130-fold or 1.0- to 1,020-fold that of enterocin Xα or enterocin Xβ alone, respectively (Table 1). Therefore, depending on indicator strains, the combined antibacterial activity was either enhanced (greatly or slightly) or reduced. Thus, rather than saying that enterocins Xα and Xβ function together as one antibacterial entity (14), it is better to say that enterocins Xα and Xβ presenting together become “a new bacteriocin” with an entirely different antibacterial spectrum than those of their component peptides.

Genetic region encoding enterocin X.

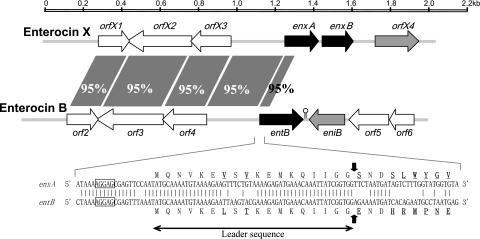

The structural gene of enterocin Xα (enxA) was discovered using PCR with degenerate primers corresponding to Trp6-Gly14 (forward) and Leu35-His27 (reverse). The neighboring DNA regions were extended by means of single-specific-primer PCR (20) and inverse PCR (15, 16). In the acquired 2,047-bp consecutive DNA fragment that contains the genes for enterocins Xα (enxA) and Xβ (enxB), six open reading frames (ORFs) were sequentially recognized according to the rules described by Harley and Reynolds (7) (Fig. 2). The functions of the orfX1, orfX2, and orfX3 genes are unknown. The orfX4 gene, located downstream of enxB, may be the immunity gene for enterocin X, based on its location and predicted product, a 73-residue, hydrophobic, and cationic (pI = 10.2) protein with two putative transmembrane domains (4, 12).

FIG. 2.

Alignment of the DNA sequences containing the genetic determinants for enterocin X and enterocin B. The DNA sequence of the enterocin B locus is obtained from the entB locus in Enterococcus faecium BFE 900 (accession no. AF076604). The horizontal arrows denote ORFs, the black arrows represent the genes encoding a prepeptide with a putative double-glycine-type leader sequence, the gray arrows represent (putative) immunity genes, and the white arrows represent the genes with unknown functions. The enxA and enxB genes are the structural genes for enterocins Xα and Xβ, respectively. The entB and eniB genes are the structural gene and the immunity gene for enterocin B, respectively. The lollipop represents a stem-loop structure functioning as a rho-independent terminator. Upstream regions of enterocin X and B loci share a sequence-similar region (longer than 1 kb; >95% identity, as shown by the gray zones between their gene clusters). The 5′ ends of enxA and entB, as well as N-terminal parts of their translation products, show high sequence similarity. The identical nucleotide bases are denoted with a bar, and the diverse amino acid residues are indicated by underlined boldface type. The rectangles indicate the proposed ribosome-binding sites. The vertical black arrows indicate the putative cleavage sites for the prepeptides translated from enxA and entB.

The enxB gene is located 19 nucleotides downstream from enxA in the same direction, with no obvious rho-independent transcriptional terminator (invert repeats) between them. Thus, enxA and enxB may belong to the same transcriptional unit, an arrangement typical of genes encoding two-peptide bacteriocins. Both enxA and enxB encode a double-glycine-type prepeptide with an 18-residue leader sequence, representing the typical structure of class II bacteriocin prepeptides. Thus, enterocin X, composed of enterocins Xα and Xβ, was confirmed to be a novel two-peptide class II bacteriocin.

Interestingly, the upstream region of the enterocin X locus (from orfX1 to the 5′ end of enxA; ∼1 kb) is sequence similar with the upstream region of the enterocin B locus (Fig. 2). These sequence-similar regions contribute to the formation of almost-identical leader sequences on enterocin B and enterocin Xα prepeptides. Thus, enterocin Xα and enterocin B were suggested to have the same transport apparatus, maybe the same as that for enterocin A (6). Furthermore, the gene encoding enterocin X was also detected by PCR in other E. faecium strains that produce enterocins A and B (strains JCM 5804T and WHE 81) (data not shown). These sequence-similar DNA regions, therefore, may imply the occurrence of gene rearrangement in bacteriocin genes.

In conclusion, this study not only reports the discovery of a novel two-peptide bacteriocin in E. faecium KU-B5 but also is the first to report the nonuniform change in antibacterial activity toward a panel of bacteria when two antibacterial peptides were combined. We also reported the interesting fact about the sequence-similar regions upstream of the enterocin X and B loci. In addition, the thermotolerant property of E. faecium KU-B5, the enterocin X producer, is beneficial in bacteriocin applications, such as silage production.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The DNA sequences of the loci for enterocins A, B, and X in E. faecium KU-B5 have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases. The accession numbers are AB292463, AB292464, and AB430879, respectively.

Acknowledgments

We thank Japan Educational Exchanges and Services for providing the JINNAI international student scholarship as financial support to C.-B.H. This work was partially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the JSPS-NRCT Core University Program on “Development of Thermotolerant Microbial Resources and Their Applications.”

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderssen, E. L., D. B. Diep, I. F. Nes, V. G. Eijsink, and J. Nissen-Meyer. 1998. Antagonistic activity of Lactobacillus plantarum C11: two new two-peptide bacteriocins, plantaricins EF and JK, and the induction factor plantaricin A. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2269-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aymerich, T., H. Holo, L. S. Håvarstein, M. Hugas, M. Garriga, and I. F. Nes. 1996. Biochemical and genetic characterization of enterocin A from Enterococcus faecium, a new antilisterial bacteriocin in the pediocin family of bacteriocins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1676-1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casaus, P., T. Nilsen, L. M. Cintas, I. F. Nes, P. E. Hernández, and H. Holo. 1997. Enterocin B, a new bacteriocin from Enterococcus faecium T136 which can act synergistically with enterocin A. Microbiology 143:2287-2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotter, P. D., C. Hill, and R. P. Ross. 2005. Bacteriocins: developing innate immunity for food. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3:777-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ennahar, S., Y. Aso, T. Zendo, K. Sonomoto, and A. Ishizaki. 2001. Biochemical and genetic evidence for production of enterocins A and B by Enterococcus faecium WHE 81. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 70:291-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Franz, C. M., R. W. Worobo, L. E. Quadri, U. Schillinger, W. H. Holzapfel, J. C. Vederas, and M. E. Stiles. 1999. Atypical genetic locus associated with constitutive production of enterocin B by Enterococcus faecium BFE 900. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2170-2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harley, C. B., and R. P. Reynolds. 1987. Analysis of E. coli promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:2343-2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauge, H. H., D. Mantzilas, V. G. Eijsink, and J. Nissen-Meyer. 1999. Membrane-mimicking entities induce structuring of the two-peptide bacteriocins plantaricin E/F and plantaricin J/K. J. Bacteriol. 181:740-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herranz, C., P. Casaus, S. Mukhopadhyay, J. M. Martínez, J. M. Rodríguez, I. F. Nes, P. E. Hernández, and L. M. Cintas. 2001. Enterococcus faecium P21: a strain occurring naturally in dry-fermented sausages producing the class II bacteriocin enterocin A and enterocin B. Food Microbiol. 18:115-131. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu, C.-B., T. Zendo, J. Nakayama, and K. Sonomoto. 2008. Description of durancin TW-49M, a novel enterocin B-homologus bacteriocin in carrot-isolated Enterococcus durans QU 49. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105:681-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klaenhammer, T. R. 1993. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 12:39-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nes, I. F., D. B. Diep, L. S. Håvarstein, M. B. Brurberg, V. Eijsink, and H. Holo. 1996. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 70:113-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsen, T., I. F. Nes, and H. Holo. 1998. An exported inducer peptide regulates bacteriocin production in Enterococcus faecium CTC492. J. Bacteriol. 180:1848-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nissen-Meyer, J., P. Rogne, C. Oppegård, H. S. Haugen, and P. E. Kristiansen. 2009. Structure-function relationships of the non-lanthionine-containing peptide (class II) bacteriocins produced by gram-positive bacteria. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 10:19-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochman, H., A. S. Gerber, and D. L. Hartl. 1988. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction. Genetics 120:621-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Keeffe, T., C. Hill, and R. P. Ross. 1999. Characterization and heterologous expression of the genes encoding enterocin A production, immunity, and regulation in Enterococcus faecium DPC1146. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1506-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oppegård, C., P. Rogne, L. Emanuelsen, P. E. Kristiansen, G. Fimland, and J. Nissen-Meyer. 2007. The two-peptide class II bacteriocins: structure, production, and mode of action. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 13:210-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park, S. H., K. Itoh, and T. Fujisawa. 2003. Characteristics and identification of enterocins produced by Enterococcus faecium JCM 5804T. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95:294-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogne, P., G. Fimland, J. Nissen-Meyer, and P. E. Kristiansen. 2008. Three-dimensional structure of the two peptides that constitute the two-peptide bacteriocin lactococcin G. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784:543-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shyamala, V., and G. F. Ames. 1989. Genome walking by single-specific-primer polymerase chain reaction: SSP-PCR. Gene 84:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zendo, T., N. Eungruttanagorn, S. Fujioka, Y. Tashiro, K. Nomura, Y. Sera, G. Kobayashi, J. Nakayama, A. Ishizaki, and K. Sonomoto. 2005. Identification and production of a bacteriocin from Enterococcus mundtii QU 2 isolated from soybean. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99:1181-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]