Abstract

NtcA is a transcription factor that has been found in a diverse range of cyanobacteria. This nitrogen-controlled factor was focused on as a key component in the yet-to-be-deciphered regulatory network controlling microcystin production. Adaptor-mediated PCR was utilized to isolate the ntcA gene from Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. This gene was cloned, and the recombinant (His-tagged) protein was overexpressed and purified for use in mobility shift assays to analyze NtcA binding to putative sites identified in the microcystin mcyA/D promoter region. Autoregulation of NtcA in M. aeruginosa was shown via NtcA binding in the upstream ntcA promoter region. The observation of binding of NtcA to the mcyA/D promoter region has direct relevance for the regulation of microcystin biosynthesis, as transcription of the mcyABCDEFGHIJ gene cluster appears to be under direct control of nitrogen.

Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 is a bloom-forming unicellular photosynthetic cyanobacterium that is capable of producing the hepatotoxin microcystin. Investigations of the role and function of microcystin are ongoing, as the true nature of this toxin has not been determined yet. Cyanobacteria have developed adaptive mechanisms that enable them to survive in a vast range of habitats, and their wide distribution and diversity, coupled with the accelerating frequency and intensity of toxic blooms, have sustained interest in this field in recent years. The transcriptional regulation of the microcystin synthetase gene cluster is a key focus of this research and may provide further evidence for existing hypotheses related to microcystin physiology, including siderophore (19, 26, 28), defense (23), and quorum-sensing (3) functions. Factors such as micronutrient levels in the environment provide interesting links to systems of regulation at the transcriptional level. As elements of transcriptional control are elucidated, a clearer role for microcystin may be proposed.

Microcystin has been shown to be highly toxic to humans (20) and animals and displays bioactivity against algae, bacteria, fungi, and mammalian cell lines (2). Toxicity in mammals occurs through an association with hepatocytes due to active transport of the toxin to the liver via bile acid multispecific organic anion transporters (24). The discovery that this toxin was produced nonribosomally (27) complemented a growing number of studies of the transcriptional regulation of cyclic peptide synthesis gene clusters, and there has been particular interest due to the vast array of bioactive compounds that these gene clusters encode (1). Early indications suggested that the light level and wavelength affect transcription of the microcystin synthetase gene cluster (mcy) (9). Acclimation responses to nutrient availability can be characterized as either responses that are specific for the nutrient that is limiting (18, 21) or responses that are general (34) and occur under a number of different nutrient limitation conditions (25). The 750-bp promoter region which bidirectionally initiates transcription of mcyABC and mcyDEFGHIJ is centrally located in the toxin biosynthesis gene cluster and is predicted to be the principal site of regulation. Characterization of the mcy promoter may result in a clearer understanding of the factors that affect toxin production.

Nitrogen control and assimilation in cyanobacteria are subject to fine control. The prokaryotic global nitrogen regulator NtcA facilitates regulation of nitrogen-responsive genes and belongs to the CAP family of transcription factors (4, 5, 29-31). In most cases, NtcA is an activator; however, it may also act as a repressor (7). NtcA was first isolated from Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 (29) and has now been characterized for a wide range of cyanobacterial genera. Due to the large number of cyanobacterial genes shown to be regulated by NtcA, it appears that NtcA responds not only to ammonium but also to the C/N ratio in the cell (13). NtcA is produced at a basal level in the presence of ammonium, and the level is elevated under nitrogen stress conditions (10, 16, 22, 31). NtcA possesses the C-terminal helix-turn-helix motif consistent with the DNA binding domain of transcription factors (33) and binds to the consensus region GTAN8TAC, and there is some variation in the length of the spacer between the palindrome and the bases flanking the binding sequences. The consensus is frequently located 22 or 23 bp upstream from an accompanying σ70-like −10 hexamer of TAN3T (5, 13), while multiple NtcA binding sites have also been shown to occur in a single promoter. NtcA can autoregulate its own transcription, and therefore a binding site homologous to the established consensus sequence is also expected to be present in the promoter region upstream of an ntcA gene.

We have identified regions with similarity to the consensus motifs recognized and bound by NtcA in the internal mcyA/D promoter region in M. aeruginosa PCC 7806. The complete gene encoding NtcA in this cyanobacterium was isolated by degenerate and adaptor-mediated PCR. The protein was then overexpressed and used to characterize the interaction and binding of NtcA to the mcyA/D promoter in vitro. The autoregulation of ntcA was also assessed, along with the transcription of ntcA and mcyB in response to different nitrogen availability conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of ntcA from Microcystis.

Total genomic DNA was extracted from mid-exponential-growth-phase cells of M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 as described previously (17). Degenerate primers were designed to target regions of cyanobacterial ntcA homology to amplify a corresponding gene fragment from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806. The unknown genomic regions flanking this amplicon were elucidated by gene walking based on adaptor-mediated PCR (14). Briefly, primers for short adaptor sequences ligated to partially digested genomic DNA and specific outward-facing primers were utilized to amplify and then sequence flanking regions. Automated sequencing was performed using the Prism BigDye cycle sequencing system and an ABI 3730 capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA).

Cloning, overexpression, and isolation of recombinant NtcA.

The ntcA gene was amplified from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 using primers NtcANde1F and NtcAXho1R (Table 1), which incorporated NdeI and XhoI restriction sites at the N and C termini, respectively. The amplified ntcA gene was ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega) for sequencing, and the results of sequencing were analyzed using Autoassembler software (Applied Biosystems). The ntcA gene was excised from pGEM-T Easy by digestion with NdeI and XhoI and subcloned into the corresponding pET-30a (Novagen) restriction sites. Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) was transformed with the new plasmid, and transformants were selected on solid LB agar supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. Plasmid inserts were again confirmed by sequencing. An initial inoculum of E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring the plasmid was grown at 30°C for 16 h and used to inoculate 600 ml of LB broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin. The expression culture was incubated at 37°C with orbital shaking at 150 rpm to obtain an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6, and then expression was induced by addition of 0.02 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Following incubation at 16°C for 2 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −20°C. For processing, cell pellets were thawed on ice, resuspended in 6 ml HEPES buffer (50 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl; pH 7.4), and sonicated three times at 4°C and 25% amplitude for 30 s with 0.5-s pulses (Branson, Danbury, CT). Following centrifugation at 4°C at 20,000 × g for 20 min, the cleared lysate containing the soluble recombinant NtcA was used for purification with a Hi-Trap nickel-charged affinity column (Amersham Biosciences) utilizing the BioLogics-HR apparatus (Bio-Rad). The purity of fractions was analyzed by SDS-PAGE (15% [wt/vol] polyacrylamide), and the columns were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue and visually recorded with LAS-3000 (FujiFilm). Fractions containing the desired protein were pooled and frozen with 10% glycerol in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80°C. Western blotting was performed to verify that the overexpressed protein was indeed recombinant (His-tagged) NtcA. Protein sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL X, and a neighbor-joining tree was produced (see Fig. 3).

TABLE 1.

Strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study

| Strain, plasmid, or primer | Relevant feature or sequence | Sequence | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 | Microcystin-producing cyanobacterium | UNSW culture collection | |

| E. coli DH5α | Cloning host | UNSW culture collection | |

| E. coli BL-21(DE3) | Expression host | UNSW culture collection | |

| Plasmids | |||

| pGEM-T Easy | Cloning vector | Promega | |

| pET-30a | Expression vector | Novagen | |

| Primers | |||

| NF | ntcA degenerate | CAGTGTTTTTGGGGTGYT | Timothy Downing, University of Port Elizabeth |

| NR | ntcA | GTTTCAATCATCATTTCCGT | Timothy Downing, University of Port Elizabeth |

| NF/1 | ntcA pan-handle | CGAGAGTAATTCTACCGGAG | This study |

| NF/2 | ntcA | GATCCCTCCGCAATAATCCC | This study |

| NF/3 | ntcA | TTTCTACCTGCTCGATCGG | This study |

| NF/4 | ntcA | AGTGAACAGATAGCTGTGC | This study |

| NF/5 | ntcA | CTGACCAAACGTGAACCCAT | This study |

| NF/6 | ntcA | CGAGTGTCACCTCTATTAAACAC | This study |

| NTCANDE1F | ntcA cloning | TCCATATGGACTTATCATTAATACAAGATAAAC | This study |

| NTCAXHO1R | ntcA cloning | TCCTCGAGAGTAAATTGTTGACTGAGAGCG | This study |

| T7 term | pET-30a | GCTAGTTATTGCTCAGCGGT | Novagen |

| T7 prom | pET-30a | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG | Novagen |

| MPF | pGEM-T Easy | CCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAACG | Promega |

| MPR | pGEM-T Easy | AGCGGATAACAATTTCACACAGG | Promega |

| T7Pr1 | Adaptor primer | CCCCTATCCACCCTTACACCTATC | 15 |

| M4F | NtcA binding site in mcyA/D promoter | CGAATTCTAATGATTTTTACTAATTTATTGGG | This study |

| M4R | NtcA binding site in mcyA/D promoter | CCGCCGGCGAATTGTTCTGAGCCTCGACAT | This study |

| M5F | NtcA binding site in mcyA/D promoter | CGAATTCCCGTCGGGTTTCCTGT | This study |

| M5R | NtcA site in mcyA/D promoter | CCGCCGGCGCATTGCTGTTCTAACTTTTTCC | This study |

| M6F | ntcA promoter | CGAATTCCAATAGCCGACCCCAGCG | This study |

| M6R | ntcA promoter | CCGCCGGCGTTTTTATTATCCAACGAGTGTCA | This study |

| NtcArealF | ntcA reverse transcription-PCR short product | CATTTCCGTTTGCAGAATCC | This study |

| NtcArealR | ntcA reverse transcription-PCR short product | TGTTTTTGGGGTGCTATCCT | This study |

| RpoC1F | rpoc1 reverse transcription-PCR short product | CCTCAGCGAAGATCAATGGT | This study |

| RpoC1R | rpoc1 reverse transcription-PCR short product | CCGTTTTTGCCCCTTACTTT | This study |

| McyBrealF | mcyB reverse transcription-PCR short product | CTGAGGGGATTACGGATTGA | This study |

| McyBrealR | mcyB reverse transcription-PCR short product | ACCATATAAGCGGGCAGTTG | This study |

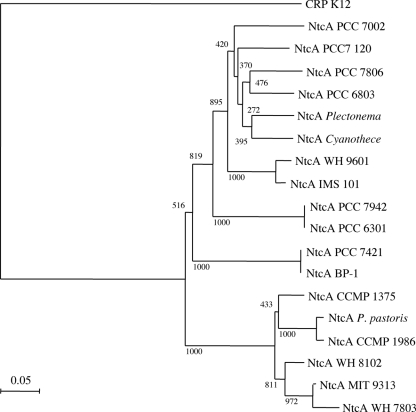

FIG. 3.

Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of NtcA protein sequences from cyanobacteria identified thus far. Bootstrap values resulting from 1,000 trials are indicated at the nodes. The sequences included in the tree are sequences obtained from the following cyanobacteria: Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 (accession no. AAK49022), Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (BAB76091), Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (BAA18011), Plectonema boryanum (AAK26380), Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142-BH68K (AAB62977), Trichodesmium sp. WH9601 (AAF63203), Trichodesmium sp. IMS 101 (AAD53080), Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 (CAA42755), Synechococcus sp. PCC 6301 (YP_172087), Gloeobacter sp. PCC 7421 (NP_926231), Thermosynechococcus sp. BP-1 (NP_682440), Prochlorococcus sp. CCMP 1375 (AAY25557), Prochlorococcus marinus subsp. pastoris (AAM82249), Prochlorococcus sp. CCMP 1986 (AAZ93923), Synechococcus sp. WH8102 (AAY25543), Prochlorococcus sp. MIT 9313 (AAY25548), and Synechococcus sp. WH7803 (AAQ55486). The E. coli K-12 CRP protein (AAC76382) was used to root the tree.

Electromobility shift assay.

Short DNA probes that were approximately 200 bp long were generated by PCR using a genomic DNA template from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806. These probes were designed to incorporate the putative NtcA binding motifs. Primers were used to introduce EcoRI and NotI restriction sites to facilitate radiolabeling. Two probes represented the mcyA/D promoter region, while a third probe targeted the promoter region of the newly identified M. aeruginosa ntcA gene (accession no. EU402445). The probes were digested with EcoRI and NotI (Promega), and the resultant overhangs were end labeled on both strands using [α-32P]dCTP and [α-32P]dATP (Perkin-Elmer) in addition to unlabeled dGTP and dTTP (Promega) in a 1-h Klenow reaction (Promega) performed at room temperature. The labeled DNA probes were precipitated with ethanol for 12 h at −20°C and then resuspended in sterile water and stored at 4°C. The probes were incubated with various concentrations of partially purified NtcA in order to establish a binding pattern. Control reactions without NtcA were also performed in order to determine the migration of the unbound free probe DNA. Binding reactions were performed in binding buffer [10 mM Tris, 40 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 100 μM MnCl2, 5% glycerol, 0.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 μg poly(dI-dC), 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then electrophoresed at 4°C through nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels for approximately 4 h at 4°C. The gels were exposed to radiosensitive imaging plates for up to 18 h and visualized using an FLA-5010 phosphoimager (FujiFilm). Analysis of labeled hybridization products was performed utilizing Image Gauge 4.0 software.

Nitrogen-limited growth of M. aeruginosa PCC 7806.

M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 was grown under nitrogen-excess, nitrogen-limited, and nitrogen-starved conditions using defined BG11 medium supplemented with 1.5 g/liter, 0.75 g/liter, and 0 g/liter sodium nitrate, respectively. To investigate the ntcA and mcyB transcription profile under the new transition conditions, RNA was extracted after 28 days (mid-log phase). To analyze ntcA and mcyB transcription in cells acclimatized to the different levels of nitrogen, RNA was extracted from the fourth generation of cells, again during the mid-log phase of growth (28 days), following three subcultures under the same conditions.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR.

RNA was extracted after cell lysis with Trizol (Invitrogen), which was followed by DNase treatment (Promega) in order to remove all traces of DNA, which was confirmed by PCR. cDNA was generated by reverse transcription using a First Strand cDNA synthesis system (Marligen Biosciences). Samples containing 100 ng/μl of cDNA were analyzed in triplicate using a Corbett Rotor-Gene real-time PCR machine (Corbett Life Sciences) with SYBR brilliant green chemistry (Invitrogen). Primers were designed to amplify 200-bp products of ntcA, the rpoC1 RNA polymerase housekeeping gene, and mcyB to indicate microcystin synthetase transcription. The primer efficiencies for amplification of ntcA, mcyB, and rpoC1 were calculated, which yielded E values of 1.6745, 2.29848, and 2.56774, respectively, where an E value of 2 indicates 100% PCR efficiency. Relative quantification of the ntcA and mcyB target genes compared with the rpoC1 reference gene was also performed (11), which yielded a fold change in transcription compared to the results for the control conditions (excess nitrogen).

RESULTS

Identification of NtcA binding sites.

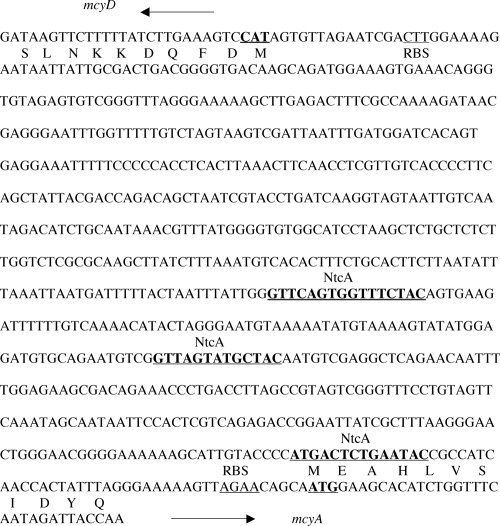

Characterization of the mcyA/D promoter sequence revealed regions that were identified as potential binding sites for the global nitrogen regulator transcription factor NtcA (Fig. 1). Possible binding and regulation by NtcA were suggested by identification of regions with high levels of similarity to the highly conserved sequence GTAN8TAC (5, 12). Three putative NtcA binding sites were found in the mcyA/D promoter.

FIG. 1.

Sequence data for the mcyA/D promoter region of M. aeruginosa PCC 7806, showing putative NtcA binding sites identified in this study. The consensus sequence target for NtcA binding proteins is GTAN8TAC.

NtcA from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806.

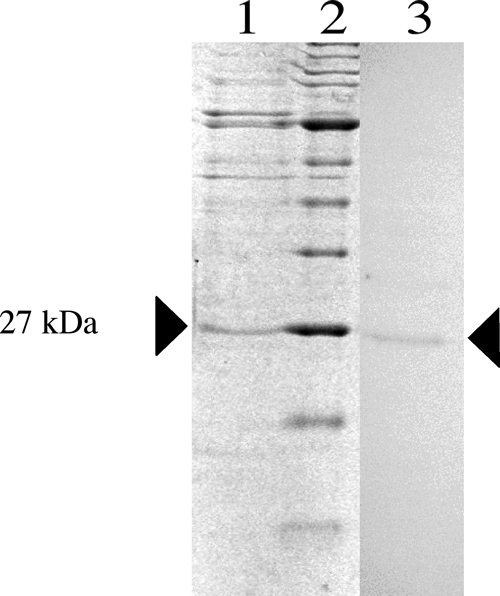

The 675-bp ntcA gene was identified and amplified in its entirety utilizing an adaptor-mediated PCR. Following ligation into the pGEM-T Easy cloning vector and sequencing, the gene was subcloned into the pET-30a expression vector, overexpressed, and purified (Fig. 2). The molecular mass of the recombinant protein was approximately 27 kDa, and the presence of the His tag was confirmed by Western blotting. Figure 3 shows the neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree produced from a Clustal X protein alignment. The E. coli K-12 cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) protein was used as an outgroup to root the tree. The NtcA protein sequence of M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 clustered with that of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803.

FIG. 2.

Partially purified recombinant NtcA electrophoresed through a 15% polyacrylamide gel (lane 1) along with a broad-range NEB ladder (lane 2). Lane 3 shows the corresponding Western blot verifying overexpression of the His-tagged protein.

Autoregulation of ntcA.

Genome walking was also used to obtain the nucleotide sequence upstream from the ntcA start codon. Autoregulation of ntcA would require the ntcA promoter in M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 to have one or several NtcA binding sites to enable gene activation under nitrogen-depleted conditions. Two putative NtcA binding sites with significant similarity to the GTAN8TAC consensus sequence were identified. Compared to the palindromic consensus sequence, the upstream NtcA binding site was identical for all six bases, while the other site matched only four bases in the motif.

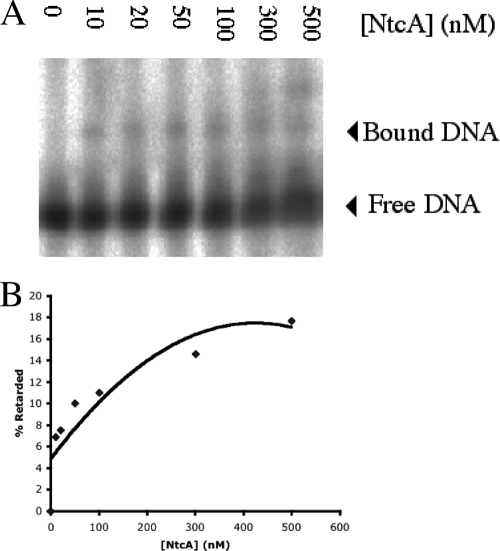

The physical interaction of the recombinant NtcA protein heterologously expressed from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 and the ntcA promoter was assayed by using the electromobility gel shift assay. Probes (200 bp) were created using the ntcA promoter sequence containing the two putative NtcA binding sites. Electrophoretic retardation of the DNA probe was observed when it was incubated with NtcA, confirming that the promoter region was bound by NtcA (Fig. 4A). An increase in the shift intensity was observed when the amount of protein was increased, and no retardation was observed for the sample lacking protein. The approximate percentage of the DNA probe retarded in the gel is shown in Fig. 4B. At an NtcA concentration of 500 nM, 18% of the probe was retarded. To investigate the potential redox regulation of DNA binding, the assay was repeated with increasing concentrations of DTT. This reducing agent did not appear to increase binding of NtcA to the probe (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

(A) Electromobility shift assay of recombinant NtcA from M. aeruginosa binding to the ntcA promoter. Lane 0 contained no protein and shows the migration of unbound free DNA. (B) Approximate percentages of the probe retarded in the gel.

NtcA binding to the mcyA/D promoter.

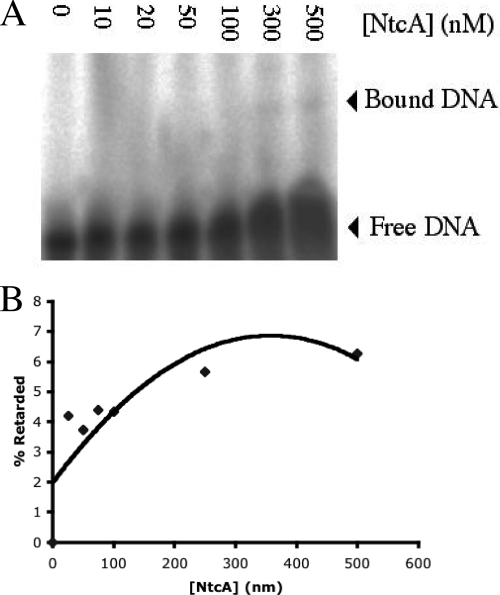

Three putative NtcA binding sites were also identified in the region upstream from the mcyD start codon (Fig. 1). Figure 5 A shows NtcA binding to the mcyA/D promoter in the electromobility shift assay, and the estimated percentage of the radiolabeled DNA probe retarded in the gel due to NtcA binding (Fig. 5B) was up to 7%. Increasing the concentration of the reducing agent DTT did not appear to affect binding of NtcA to the mcyA/D promoter (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

(A) Electromobility shift assay of recombinant NtcA from M. aeruginosa binding to the mcyA/D promoter. Lane 0 contained no protein and shows the migration of unbound free DNA. (B) Approximate percentages of the probe retarded in the gel.

Profiles of ntcA and mcyB expression under different nitrogen conditions.

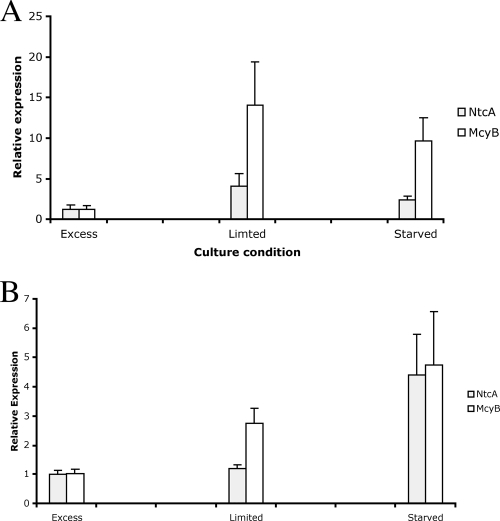

The relative levels of transcription of ntcA and mcyB under nitrogen-excess, nitrogen-limited, and nitrogen-starved culture conditions were determined (Fig. 6). The transcription levels were expressed as the relative levels of expression by using the cycle threshold (CT) values of rpoC1 and ntcA or mcyB in addition to the primer efficiency E value. The nitrogen-excess conditions were designated the control conditions, and therefore the results were normalized to a value of 1. For acclimatized cells (Fig. 6A), ntcA transcription increased 4.07-fold under the nitrogen-limited conditions. The level of upregulation in the nitrogen-starved conditions was 2.36-fold. The transcription of mcyB increased markedly under the nitrogen-limited conditions to a level that was 14.09 greater than the level under nitrogen-excess conditions. The increase again was smaller under the nitrogen-starved conditions (9.70-fold compared to the control). For the nutrient-shocked cells (Fig. 6B), ntcA transcription increased 1.21-fold under the nitrogen-limited conditions and 4.40-fold under the nitrogen-starved conditions. A similar trend was seen for mcyB transcription; there was a 2.75-fold increase under the nitrogen-limiting conditions, and there was a 4.76-fold increase under the nitrogen-starved conditions.

FIG. 6.

Relative expression of ntcA and mcyB under nitrogen-excess, nitrogen-limited, and nitrogen-starved conditions after addition of 1.5 g/liter, 0.75 g/liter, and 0 g/liter sodium nitrate, respectively, to defined BG11 medium. (A) Real-time PCR results for nitrogen-acclimatized cells. (B) Results for nitrogen-shocked cells (see text for details).

DISCUSSION

Inspection of the mcyA/D promoter revealed putative binding sites for the transcription factor NtcA, a global transcription regulator for nitrogen control in cyanobacteria. NtcA binding and regulation sequences in promoter regions are identified by motifs that exhibit significant similarity to the highly conserved sequence GTAN8TAC (5, 12). Initially identified in Synechococcus sp. PCC 7942 as an activator of genes repressed by ammonium (29), NtcA was subsequently identified in many cyanobacteria, including filamentous, unicellular, and heterocyst-forming species (5). Here, an ntcA gene fragment was amplified from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 utilizing degenerate primers targeting a highly conserved region of the gene corresponding to the β-roll and α-helices in the protein. Following amplification of the complete ntcA gene sequence by adaptor-mediated PCR, the translated NtcA protein was characterized. The NtcA protein was cloned and overexpressed in E. coli (Fig. 2). A phylogenetic tree (Fig. 3) indicated that NtcA from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 was closely related to NtcA from Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, a unicellular, non-nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium. However, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 is nontoxic and therefore fundamentally distinct from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806. It is noteworthy that in a 16S rRNA sequence tree, M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 are also closely related.

In addition to the complete gene sequence for ntcA, the upstream promoter region was also obtained by adaptor-mediated PCR. It was hypothesized that a canonical NtcA binding motif would be found in this region. Two putative sites were identified, and their sequences were GTATAATAGGGATAC and GTTGTGTTTAATAG. It has previously been reported that multiple NtcA binding sites may occur in a single promoter, enabling more sensitive attenuation (12). Separated by approximately 60 bp, the NtcA binding motifs presumably are on the same face of the DNA helix. In addition, motifs homologous to a σ70-type E. coli promoter were observed, and the short 7-bp spacer region between the −10 (GATAAT) and −35 (GTGACA) regions suggested that the NtcA activator site, which is only 2 bases upstream from the −35 sequence, permits increased affinity for the σ factor of RNA polymerase (33). The stronger NtcA binding consensus sequence (GTATAATAGGGATAC) was identified at position −52 from the start codon and could therefore provide sensitive NtcA autoregulation.

Weak NtcA binding was observed in electromobility shift assays after incubation of the ntcA promoter region with partially purified NtcA (Fig. 4A). Monomeric and dimeric binding was observed and is proposed to occur at the GTAN9TAC NtcA binding motif identified. Quantification of retarded gel electrophoresis bands revealed that up to 18% of the DNA probe was retarded in the gel (Fig. 4B). This suggested that ntcA is autoregulated in M. aeruginosa PCC 7806. In particular, analysis of the redox attenuation of NtcA DNA binding affinity has focused on the thiol groups of cysteine residues (7). Addition of the reducing agent DTT to the binding reaction with NtcA and the ntcA promoter probe was investigated; however, this agent did not appear to increase binding of the promoter and ligand. Thiol groups on cysteine residues are necessary for DNA binding due to their inactivation when they are incubated with diamide (7), even though a double cysteine mutant strain of Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 had increased binding affinity after addition of DTT (32). The translated sequence of NtcA from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 contained only one cysteine; hence, the observed absence of redox regulation of binding affinity may be sequence specific. In fact, it was anticipated that addition of DTT would lead to increased binding, despite the fact that a single cysteine residue was present and the fact that low binding affinity was expected due to the presence of a noncanonical motif.

An additional gel shift product was observed with 300 and 500 nM NtcA (Fig. 4A), which suggested that there was formation and binding of a protein dimer. DNA binding proteins that possess a C-terminal helix-turn-helix motif, such as NtcA, are likely to form dimers or even polymers (12). NtcA also bound weakly to the mcyA/D GTAN9TAC motif (Fig. 5A). Approximately 7% of the total DNA probe was retarded in the electromobility gel shift assay by NtcA binding activity (Fig. 5B). This result suggested that the transcription of microcystin is regulated in part by NtcA. Addition of DTT also had no effect on the binding of NtcA and the mcyA/D promoter. As discussed above, this could be attributed to the lack of multiple cysteine residues in the protein; hence, the redox regulation of the binding of NtcA to the mcyA/D promoter would be limited. Although the presence of the GTAN9TAC NtcA binding motif identified in the ntcA and mcyA/D promoters was confirmed by NtcA binding in electromobility gel shift assays, the observed level of binding was low. NtcA binding to promoters with motifs that differ from the established GTAN8TAC sequence has been reported (8), and the more divergent the binding sequences compared with the consensus sequence, the lower the NtcA affinity. A weakly conserved sequence central to the palindromic loci was also proposed to result in differential NtcA binding under various physiological conditions (8). It is apparent that the promoter sequences putatively recognized by NtcA from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 include a spacer region consisting of nine bases, and this divergence from the classical consensus explains the weak binding observed.

The classical pattern of transcription expected for an activator regulatory protein such as NtcA includes an increase in transcription under dynamic conditions. Subsequently, as production of the activator protein increases, the transcription of the target protein is also upregulated. The transcription of mcyB under nitrogen stress conditions was mirrored by the increase in ntcA transcription, which strongly suggested that nitrogen levels affect microcystin production rates (Fig. 6). Multiple transcripts of ntcA have been found (22), and this finding could be linked to the theory that changes in the weakly conserved N8 sequence in the GTAN8TAC motif may modulate NtcA binding under changing physiological conditions (8). The method employed in this study was unable to determine if multiple transcripts were synthesized from a single promoter; however, it would be beneficial to elucidate if multiple transcripts of ntcA or mcyB were produced. Future research in this area could also include a variety of nitrogen sources.

It has been suggested that NtcA may also act as a repressor, as reported for gor in Anabaena sp. PCC 7120 (6), under general stress conditions and in response to nitrogen availability. Several NtcA binding sites were identified, one of which overlaps the σ70-type E. coli promoter. This organization may result in the production of multiple transcripts under cellular conditions, as needed (6). This promoter arrangement echoes that of the mcyA/D promoter, and therefore it is possible that NtcA also acts as a repressor of microcystin synthetase transcription. In this case, however, the level of the mcyB transcript would be expected to decline as the level of the ntcA transcript increased.

In summary, the cloning and overexpression of NtcA from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 in this study revealed the predicted autoregulation of ntcA, and additional results reflected the role of NtcA as a transcriptional activator. Binding of NtcA to the mcyA/D promoter from M. aeruginosa PCC 7806 suggests that the regulation of microcystin synthetase gene transcription is responsive to nitrogen.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially support by the Australian Research Council and the CRC for Water Quality and Treatment.

We thank Ralitza Alexova for editing the manuscript and I. W. Dawes for gel shift materials.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burja, A. M., B. Banaigs, E. Abou-Mansour, J. G. Burgess, and P. C. Wright. 2001. Marine cyanobacteria—a prolific source of natural products. Tetrahedron 57:9347-9377. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carmichael, W. W. 1992. Cyanobacteria secondary metabolites—the cyanotoxins. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 72:445-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dittmann, E., M. Erhard, M. Kaebernick, C. Scheler, B. A. Neilan, H. von Dohren, and T. Borner. 2001. Altered expression of two light-dependent genes in a microcystin-lacking mutant of Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806. Microbiology 147:3113-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frias, J. E., A. Merida, A. Herrero, J. Martin-Nieto, and E. Flores. 1993. General distribution of the nitrogen control gene ntcA in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 175:5710-5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrero, A., A. M. Muro-Pastor, and E. Flores. 2001. Nitrogen control in cyanobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 183:411-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang, F., U. Hellman, G. E. Sroga, B. Bergman, and B. Mannervik. 1995. Cloning, sequencing, and regulation of the glutathione reductase gene from the cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. J. Biol. Chem. 270:22882-22889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang, F., B. Mannervik, and B. Bergman. 1997. Evidence for redox regulation of the transcription factor NtcA, acting both as an activator and a repressor, in the cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. Biochemistry 327:513-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang, F., S. Wisen, M. Widersten, B. Bergman, and B. Mannervik. 2000. Examination of the transcription factor NtcA-binding motif by in vitro selection of DNA sequences from a random library. J. Mol. Biol. 301:783-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaebernick, M., B. A. Neilan, T. Borner, and E. Dittmann. 2000. Light and the transcriptional response of the microcystin biosynthesis gene cluster. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:3387-3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindell, D., E. Padan, and A. F. Post. 1998. Regulation of ntcA expression and nitrite uptake in the marine Synechococcus sp. strain WH 7803. J. Bacteriol. 180:1878-1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luque, I., E. Flores, and A. Herrero. 1994. Molecular mechanism for the operation of nitrogen control in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 13:2862-2869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luque, I., M. F. Vazquez-Bermudez, J. Paz-Yepes, E. Flores, and A. Herrero. 2004. In vivo activity of the nitrogen control transcription factor NtcA is subjected to metabolic regulation in Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 236:47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffitt, M. C., and B. A. Neilan. 2004. Characterization of the nodularin synthetase gene cluster and proposed theory of the evolution of cyanobacterial hepatotoxins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:6353-6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffitt, M. C., and B. A. Neilan. 2001. On the presence of peptide synthetase and polyketide synthase genes in the cyanobacterial genus Nodularia. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 196:207-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muro-Pastor, A. M., A. Valladares, E. Flores, and A. Herrero. 2002. Mutual dependence of the expression of the cell differentiation regulatory protein HetR and the global nitrogen regulator NtcA during heterocyst development. Mol. Microbiol. 44:1377-1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neilan, B. A., D. Jacobs, and A. E. Goodman. 1995. Genetic diversity and phylogeny of toxic cyanobacteria determined by DNA polymorphisms within the phycocyanin locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:3875-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omata, T., X. Andriesse, and A. Hirano. 1993. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster involved in nitrate transport in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. PCC7942. Mol. Gen. Genet. 236:193-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orr, P. T., and G. J. Jones. 1998. Relationship between microcystin production and cell division rates in nitrogen limited Microcystis aeruginosa cultures. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43:1604-1614. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pouria, S., A. de Andrade, J. Barbosa, R. L. Cavalcanti, V. T. Barreto, C. J. Ward, W. Preiser, G. K. Poon, G. H. Neild, and G. A. Codd. 1998. Fatal microcystin intoxication in haemodialysis unit in Caruaru, Brazil. Lancet 352:21-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quisel, J. D., D. D. Wykoff, and A. R. Grossman. 1996. Biochemical characterization of the extracellular phosphatases produced by phosphorus-deprived Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 111:839-848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramasubramanian, T. S., T. F. Wei, A. K. Oldham, and J. W. Golden. 1996. Transcription of the Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 ntcA gene: multiple transcripts and NtcA binding. J. Bacteriol. 178:922-926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rohrlack, T., E. Dittmann, M. Henning, T. Borner, and J. G. Kohl. 1999. Role of microcystins in poisoning and food ingestion inhibition of Daphnia galeata caused by the cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:737-739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Runnegar, M., N. Berndt, and N. Kaplowitz. 1995. Microcystin uptake and inhibition of protein phosphatases: effects of chemoprotectants and self-inhibition in relation to known hepatic transporters. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 134:264-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwarz, R., and A. R. Grossman. 1998. A response regulator of cyanobacteria integrates diverse environmental signals and is critical for survival under extreme conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:11008-11013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi, L., W. W. Carmichael, and I. Miller. 1995. Immuno-gold localisation of hepatotoxins in cyanobacterial cells. Arch. Microbiol. 163:7-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tillett, D., E. Dittmann, M. Erhard, H. von Dohren, T. Borner, and B. A. Neilan. 2000. Structural organization of microcystin biosynthesis in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC7806: an integrated peptide-polyketide synthetase system. Chem. Biol. 7:753-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Utkilen, H., and N. Gjolme. 1995. Iron-stimulated toxin production in Microcystis aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:797-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vega-Palas, M. A., E. Flores, and A. Herrero. 1992. NtcA, a global nitrogen regulator from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus that belongs to the Crp family of bacterial regulators. Mol. Microbiol. 6:1853-1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vega-Palas, M. A., F. Madueno, A. Herrero, and E. Flores. 1990. Identification and cloning of a regulatory gene for nitrogen assimilation in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 172:643-647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei, T., T. S. Ramasubramanian, F. Pu, and J. W. Golden. 1993. Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120 bifA gene encoding a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein cloned by in vivo transcriptional interference selection. J. Bacteriol. 175:4025-4035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wisen, S., B. Bergman, and B. Mannervik. 2004. Mutagenesis of the cysteine residues in the transcription factor NtcA from Anabaena PCC 7120 and its effects on DNA binding in vitro. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1679:156-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wisen, S., F. Jiang, B. Bergman, and B. Mannervik. 1999. Expression and purification of the transcription factor NtcA from the cyanobacterium Anabaena PCC 7120. Protein Expr. Purif. 17:351-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wykoff, D. D., J. P. Davies, A. Melis, and A. R. Grossman. 1998. The regulation of photosynthetic electron transport during nutrient deprivation in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 117:129-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]