Abstract

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common infectious diseases of humans, with Escherichia coli being responsible for >80% of all cases. Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ABU) occurs when bacteria colonize the urinary tract without causing clinical symptoms and can affect both catheterized patients (catheter-associated ABU [CA-ABU]) and noncatheterized patients. Here, we compared the virulence properties of a collection of ABU and CA-ABU nosocomial E. coli isolates in terms of antibiotic resistance, phylogenetic grouping, specific UTI-associated virulence genes, hemagglutination characteristics, and biofilm formation. CA-ABU isolates were similar to ABU isolates with regard to the majority of these characteristics; exceptions were that CA-ABU isolates had a higher prevalence of the polysaccharide capsule marker genes kpsMT II and kpsMT K1, while more ABU strains were capable of mannose-resistant hemagglutination. To examine biofilm growth in detail, we performed a global gene expression analysis with two CA-ABU strains that formed a strong biofilm and that possessed a limited adhesin repertoire. The gene expression profile of the CA-ABU strains during biofilm growth showed considerable overlap with that previously described for the prototype ABU E. coli strain, 83972. This is the first global gene expression analysis of E. coli CA-ABU strains. Overall, our data suggest that nosocomial ABU and CA-ABU E. coli isolates possess similar virulence profiles.

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most common infectious diseases acquired in nosocomial settings. UTIs may be symptomatic (e.g., cystitis and pyelonephritis) or asymptomatic. Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ABU) is an asymptomatic carrier state that resembles commensalism. ABU patients often carry >105 CFU/ml of urine of a single bacterial strain without symptoms; in nosocomial settings, ABU frequently occurs in both catheterized and noncatheterized patients. In catheterized patients, the risk of bacteriuria is estimated to be 5 to 10% per day (46), and most patients with an indwelling urinary catheter for 30 days or longer develop bacteriuria (35). ABU in catheterized and noncatheterized patients may also lead to symptomatic UTIs, with patients experiencing fever, suprapubic tenderness, and, in some cases, bacteremia, acute pyelonephritis, and death (16, 45).

ABU is caused by a range of Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms, including Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Providencia stuartii, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Enterococcus faecalis (16, 46). In many cases, the bacteria that cause these infections are resistant to multiple antibiotics, and thus, they pose a serious threat to the safety and proper functioning of health care facilities. E. coli is one of the most common causes of nosocomial UTIs (including ABU) (17, 36). Many ABU E. coli strains are phylogenetically related to virulent uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) strains, with the differences in virulence properties being multifactorial and associated with various combinations of genotypic and phenotypic factors (26, 49). The prototype ABU E. coli strain, strain 83972, is a B2 clinical isolate capable of long-term bladder colonization, as shown in human inoculation studies (14, 38). Bladder infection with E. coli 83972 fails to induce a host inflammatory response, and this is associated with the attenuation of several virulence determinants, including type 1, P, and F1C fimbriae (24, 32, 47). The lack of fimbriae appears to be essential, as a P-fimbriated and adherent transformant of E. coli 83972 triggers inflammation in the human urinary tract (47).

The characteristics of E. coli that cause asymptomatic bacteriuria in catheterized patients (catheter-associated ABU [CA-ABU]) and their relationship to ABU E. coli in noncatheterized patients have not been investigated. The insertion and presence of an indwelling catheter predispose an individual to infection by causing damage to the uroepithelial mucosa and providing a surface for biofilm formation, which may thus affect the normal functioning and voiding of the bladder (7, 16). Therefore, E. coli strains causing asymptomatic bacteriuria in noncatheterized and catheterized patients may utilize different strategies to efficiently colonize the urinary tract. In the present study, we have compared the molecular characteristics, phenotypic properties and antimicrobial resistance profiles of 176 consecutively isolated ABU E. coli strains (from noncatheterized patients) and CA-ABU E. coli strains from the same geographic area. Biofilm formation was identified as a common feature for both ABU and CA-ABU strains, and we explored this further by examining the transcriptome of two CA-ABU E. coli strains during biofilm growth and comparing this with the transcriptome for ABU E. coli 83972 grown under the same conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and bacterial isolates.

Eighty-eight E. coli ABU isolates and 88 E. coli CA-ABU isolates were obtained from urine samples of patients at the Princess Alexandra Hospital (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia) during the period from February to July 2006. ABU was defined as a clean-catch voided urine specimen with counts of >105 CFU/ml of a single organism. There were no ABU patients who were catheterized. CA-ABU was defined by the presence of an indwelling catheter and a urine specimen with counts of >105 CFU/ml. ABU and CA-ABU patients had no conditions indicative of symptomatic UTIs (i.e., fever, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral angle tenderness) in the 48-h period prior to or following urine collection. ABU patients (67% female) had a mean age of 66 years (range, 20 to 100 years); CA-ABU patients (46% female) had a mean age of 56 years (range, 17 to 94 years). The most common comorbid conditions were 23% endocrine, 19% cardiovascular dysfunction, 16% neurological, and 15% urological for patients with ABU and 51% neurological, 22% endocrine, 15% urological, 7% musculoskeletal, and 7% cardiovascular dysfunction for patients with CA-ABU. Urine cultures were performed as part of ward screening. All E. coli isolates were identified by typical morphology, lactose fermentation, and a positive spot indole test. Isolates that did not meet these criteria were identified in full by a Vitek 2-GN card (bioMérieux). Isolates were tested for resistance to common antimicrobial agents using the Vitek 2 system at the Princess Alexandra Hospital. E. coli 83972 is a prototype ABU clinical isolate originally isolated from a young Swedish girl who carried it for 3 years without adverse affects (1a, 25). All strains were routinely grown at 37°C on solid or in liquid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium.

PCR screening.

The presence of the following virulence genes was assessed for each ABU and CA-ABU isolate: fimH (type 1 fimbrial adhesin), papG I to III (P fimbriae adhesins), flu (antigen 43), focG (F1C fimbrial subunit protein), sfaS (S fimbrial adhesin), afa/draBC (Afa/Dr chaperone and anchoring proteins), mrkB (type 3 fimbrial chaperone protein), hlyA (hemolysin), cnf1 (cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1), fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), iutA (aerobactin receptor), iroN (salmochelin receptor), kpsMT II (group II capsule), kpsMT III (group III capsule), kpsMT K1 (K1 capsule), and kpsMT K5 (K5 capsule). The methods for bacterial DNA preparation, primer sequences, and reaction conditions have been described previously (22, 23, 29, 42). The E. coli phylogenetic group of origin was determined using a three-locus PCR-based method (4). All strains were tested in duplicate with appropriate positive and negative controls.

Phenotypic assays.

The capacity of bacteria to express type 1 fimbriae was assayed by determining their ability to agglutinate yeast cells on glass slides (34). Those strains that reacted negative in this assay were retested after three successive rounds of 48 h of static growth in LB medium. Mannose-resistant hemagglutination (MRHA) was assessed as described previously (9). Hemolysin production was detected on sheep blood agar plates as described previously (21). Strains that produced a clear zone of lysis after incubation for 24 h at 37°C were considered positive. Motility was assayed by inoculating 0.25% LB agar plates with 2 μl of overnight liquid cultures and measuring the diameter of bacterial growth 16 h after inoculation.

Biofilm assays.

For screening of the isolate collection, biofilm formation on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) surfaces was monitored using 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon), following growth in synthetic urine, as described previously (26). Isolates were considered positive for biofilm formation if the stained biofilm had an absorbance at 595 nm equal to or greater than 0.5. The results represent the averages of three independent experiments, each with four replicates per strain. E. coli M366 and MS2034 and their respective ybtS deletion mutants were assayed for biofilm formation in the same manner. Biofilm growth on Bard Biocath Foley latex catheters was assayed for 10 ABU and 10 CA-ABU strains selected as representatives for the different levels of biofilm growth observed on the PVC microtiter plates. The strains were grown statically for 24 h at 37°C in 3 ml of pooled human urine in the presence of a catheter section (1 cm long, vertically dissected). The urine was then removed and replaced with fresh pooled human urine from the same original source, and the incubation was continued as described above for a further 24 h. Following this incubation, the catheter sections were removed, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and transferred to 1 ml sterile PBS, and the biofilm was disrupted by vigorous vortexing using a TissueLyser (Qiagen). The bacteria were enumerated using quantitative colony counts on agar to determine the amount of biofilm growth. All experiments were repeated at least twice.

Microarray experiments.

DNA microarrays were performed for CA-ABU E. coli strains M366 and MS2034, as described previously (11). Briefly, M366 and MS2034 were grown to mid-exponential phase in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) minimal medium (supplemented with 0.2% glucose) or pooled human urine or as a biofilm in urine in 94-mm petri dishes (Greiner Bio-One). Each combination of strain and growth condition was assayed in triplicate. Samples for RNA isolation were extracted and mixed directly with 2 volumes of RNAprotect bacterial reagent (Qiagen AG). Total RNA was isolated, and on-column DNase digestion was performed using an RNeasy minikit and an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen AG). Purified RNA (10 μg per sample) was converted to cDNA, and microarray analysis was performed according to the guidelines of the GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual 701023, revision 4 (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) (1). Labeled cDNA was hybridized to GeneChip E. coli Genome 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix). Overall, nine samples were hybridized to nine chips for each strain, with triplicates for the three growth conditions being used. Hybridization, washing, and staining were performed as described in the GeneChip Expression Analysis Technical Manual 701023 (1), with the microarrays being scanned using a GeneChip Scanner 3000 scanner. The 18 arrays for strains M366 and MS2034 were normalized with the E. coli 83972 arrays previously analyzed under the same growth conditions (11, 33). Data analysis was performed as described previously (11). For each strain, the fold changes were calculated for biofilm growth compared to either planktonic growth in MOPS or planktonic growth in urine. Randomly permuting the samples 200 times gave false discovery rates of 0.0 to 0.7% (1 to 22 false-positive genes) for the different comparisons.

Construction of ybtS deletion mutants.

Deletion mutants of the yersiniabactin synthesis gene ybtS in strains M366 and MS2034 were constructed using the bacteriophage λ red recombinase gene inactivation method, as described previously (5). Plasmid pKD4 was used as the template with the deletion primers previously employed by Henderson et al. (12). The PCR product was transformed into M366(pKD46) and MS2034(pKD46), respectively, and mutants were selected following growth on LB agar containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Deletion mutants were verified by PCR with the ybtS flanking primers 5′-GCACCGCCTTATACAATTGG and 5′-GTTATCGGTGGCGTTGTTG.

Statistical analysis.

Comparisons of prevalence data were tested using the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test with MiniTab (version 15) statistical software. The median virulence scores were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Differences in catheter biofilm growth were tested using a Student t test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Microarray data accession number.

The microarray data have been deposited in Array Express (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress) under accession number E-MEXP-2298.

RESULTS

Phylogenetic grouping of ABU and CA-ABU strains.

Our collection comprised 88 ABU and 88 CA-ABU E. coli strains isolated from the same geographic location. The majority of the strains belonged to phylogenetic group B2 (68% versus 8% for group A, 5% for group B1, and 19% for group D) (Table 1). The distribution of phylogenetic groups did not differ significantly between the ABU and CA-ABU strains (for ABU strains, 8% A, 6% B1, 68% B2, and 18% D; for CA-ABU strains, 9% A, 3% B1, 68% B2, and 19% D).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of phylogenetic groups and virulence factors among ABU and CA-ABU E. coli isolates

| Phylogenetic group, virulence gene, or phenotype | All strains |

Ampicillin resistance |

Cephalothin resistance |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of strains |

Pb | No. (%) of ABU strains |

P for ABU strains | No. (%) of CA-ABU strains |

P for CA-ABU strains | No. (%) of ABU strains |

P for ABU strains | No. (%) of CA-ABU strains |

P for CA-ABU strains | ||||||

| ABU (n = 88) | CA-ABU (n = 88) | Susceptible (n = 45) | Resistant (n = 43) | Susceptible (n = 44) | Resistant (n = 44) | Susceptible (n = 40) | Resistant (n = 48) | Susceptible (n = 36) | Resistant (n = 52) | ||||||

| Phylogenetic group | |||||||||||||||

| A | 7 (8) | 8 (9) | NS | 3 (7) | 4 (9) | NS | 3 (7) | 5 (11) | NS | 1 (3) | 6 (13) | NS | 4 (11) | 4 (8) | NS |

| B1 | 5 (6) | 3 (3) | NS | 3 (7) | 2 (5) | NS | 3 (7) | 0 (0) | NS | 2 (5) | 3 (6) | NS | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | NS |

| B2 | 60 (68) | 60 (68) | NS | 33 (73) | 27 (63) | NS | 28 (64) | 32 (73) | NS | 35 (88) | 25 (52) | <0.001 | 22 (61) | 38 (73) | NS |

| D | 16 (18) | 17 (19) | NS | 6 (13) | 10 (23) | NS | 10 (23) | 7 (16) | NS | 2 (5) | 14 (29) | 0.005 | 8 (22) | 9 (17) | NS |

| Virulence gene | |||||||||||||||

| fimH | 86 (98) | 86 (98) | NS | 45 (100) | 41 (95) | NS | 43 (98) | 43 (98) | NS | 40 (100) | 46 (96) | NS | 35 (97) | 51 (98) | NS |

| papG I | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | NS | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | NS | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | NS | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS |

| papG II | 16 (18) | 26 (30) | NS | 8 (18) | 8 (19) | NS | 6 (14) | 20 (45) | 0.001 | 8 (20) | 8 (17) | NS | 7 (19) | 19 (37) | NS |

| papG III | 21 (24) | 17 (19) | NS | 13 (29) | 8 (19) | NS | 8 (18) | 9 (20) | NS | 15 (38) | 6 (13) | 0.006 | 9 (25) | 8 (15) | NS |

| papG (all alleles) | 37 (42) | 38 (43) | NS | 21 (47) | 16 (37) | NS | 14 (32) | 24 (55) | 0.031 | 22 (55) | 15 (31) | 0.025 | 15 (42) | 23 (44) | NS |

| flu | 51 (58) | 55 (63) | NS | 25 (56) | 26 (60) | NS | 21 (48) | 34 (77) | 0.004 | 27 (68) | 24 (50) | NS | 23 (64) | 32 (62) | NS |

| focG | 14 (16) | 20 (23) | NS | 9 (20) | 5 (12) | NS | 9 (20) | 11 (25) | NS | 11 (28) | 3 (6) | 0.009 | 11 (31) | 9 (17) | NS |

| sfaS | 8 (9) | 7 (8) | NS | 4 (9) | 4 (9) | NS | 5 (11) | 2 (5) | NS | 6 (15) | 2 (4) | NS | 2 (6) | 5 (10) | NS |

| afa/draBC | 7 (8) | 7 (8) | NS | 6 (13) | 1 (2) | NS | 2 (5) | 5 (11) | NS | 4 (10) | 3 (6) | NS | 4 (11) | 3 (6) | NS |

| mrkB | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | NS | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | NS | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | NS | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | NS | 2 (6) | 1 (2) | NS |

| hlyA | 17 (19) | 24 (27) | NS | 12 (27) | 5 (12) | NS | 12 (27) | 12 (27) | NS | 13 (33) | 4 (8) | 0.006 | 11 (31) | 13 (25) | NS |

| cnf1 | 24 (27) | 23 (26) | NS | 12 (27) | 12 (28) | NS | 11 (25) | 12 (27) | NS | 15 (38) | 9 (19) | 0.049 | 10 (28) | 13 (25) | NS |

| fyuA | 69 (78) | 73 (83) | NS | 34 (76) | 35 (81) | NS | 34 (77) | 39 (89) | NS | 31 (78) | 38 (79) | NS | 26 (72) | 47 (90) | 0.026 |

| iutA | 31 (35) | 43 (49) | NS | 10 (22) | 21 (49) | 0.009 | 13 (30) | 30 (68) | <0.001 | 15 (38) | 16 (33) | NS | 14 (39) | 29 (56) | NS |

| iroN | 44 (50) | 37 (42) | NS | 27 (60) | 17 (40) | NS | 17 (39) | 20 (45) | NS | 30 (75) | 14 (29) | <0.001 | 16 (44) | 21 (40) | NS |

| kpsMT II | 45 (51) | 63 (72) | 0.005 | 18 (40) | 27 (63) | 0.033 | 29 (66) | 34 (77) | NS | 18 (45) | 27 (56) | NS | 20 (56) | 43 (83) | 0.006 |

| kpsMT III | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | NS | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | NS | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | NS | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | NS | 2 (6) | 2 (4) | NS |

| kpsMT K1 | 11 (13) | 28 (32) | 0.002 | 7 (16) | 4 (9) | NS | 16 (36) | 12 (27) | NS | 5 (13) | 6 (13) | NS | 9 (25) | 19 (37) | NS |

| kpsMT K5 | 24 (27) | 34 (39) | NS | 9 (20) | 15 (35) | NS | 12 (27) | 22 (50) | 0.029 | 10 (25) | 14 (29) | NS | 11 (31) | 23 (44) | NS |

| Virulence gene score, median | 5 | 6 | NS | 5 | 5 | NS | 4 | 6 | 0.017 | 7 | 4 | 0.004 | 6 | 6 | NS |

| Phenotype | |||||||||||||||

| Yeast agglut.a | 82 (93) | 81 (92) | NS | 43 (96) | 39 (91) | NS | 41 (93) | 40 (91) | NS | 37 (93) | 45 (94) | NS | 33 (92) | 48 (92) | NS |

| MRHA | 30 (34) | 13 (15) | 0.003 | 16 (36) | 14 (33) | NS | 7 (16) | 6 (14) | NS | 18 (45) | 12 (25) | 0.049 | 9 (25) | 4 (8) | 0.033 |

| Hemolysis | 18 (20) | 16 (18) | NS | 13 (29) | 5 (12) | 0.045 | 8 (18) | 8 (18) | NS | 14 (35) | 4 (8) | 0.003 | 8 (22) | 8 (15) | NS |

| Motility | 60 (68) | 63 (72) | NS | 30 (67) | 30 (70) | NS | 34 (77) | 29 (66) | NS | 25 (63) | 35 (73) | NS | 24 (67) | 39 (75) | NS |

| Biofilm | 52 (59) | 42 (48) | NS | 26 (58) | 26 (60) | NS | 27 (61) | 15 (34) | 0.010 | 24 (60) | 28 (58) | NS | 20 (56) | 22 (42) | NS |

agglut., agglutination.

Only significant P values (P < 0.05) have been shown; nonsignificant values are labeled NS.

Resistance to antibacterial agents.

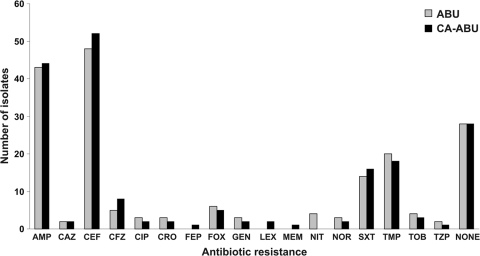

We compared the antibiogram of each ABU and CA-ABU E. coli strain by examining for resistance to ampicillin, ceftazidime, cephalothin, cefazolin, ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, cefepime, cefoxitin, gentamicin, cephalexin, meropenem, nitrofurantoin, norfloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, tobramycin, and piperacillin-tazobactam. There was no significant difference in the number of ABU and CA-ABU strains resistant to each antibiotic (Fig. 1). The antibiotics to which there was most commonly resistance were cephalothin (57% of all strains) and ampicillin (49% of all strains); 32% of the strains were susceptible to all of the antibiotics tested.

FIG. 1.

Numbers of ABU and CA-ABU E. coli isolates resistant to each antibiotic included in the antibiotic screening. The “none” category indicates isolates that were susceptible to all antibiotics included in this study. There were no statistically significant differences between the numbers of resistant isolates in the ABU and CA-ABU groups for any antibiotic. AMP, ampicillin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CEF, cephalothin; CFZ, cefazolin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CRO, ceftriaxone; FEP, cefepime; FOX, cefoxitin; GEN, gentamicin; LEX, cephalexin; MEM, meropenem; NIT, nitrofurantoin; NOR, norfloxacin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TMP, trimethoprim; TOB, tobramycin; and TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam.

Distribution of virulence genes.

The prevalence of 18 defined virulence marker genes in the 176 ABU and CA-ABU E. coli strains was assessed by PCR (Table 1). The median numbers of virulence genes for the ABU and CA-ABU strains were similar: five and six, respectively. The fimH gene was the most common virulence gene and was present in 98% of both ABU and CA-ABU strains. The papG gene was detected in 42% of ABU strains and 43% of CA-ABU strains. Genes for F1C fimbriae, S fimbriae, and the Afa/Dr family of adhesins were present in 8 to 23% of strains, with similar numbers observed for ABU and CA-ABU strains. The gene encoding the autotransporter adhesin Ag43 (flu) was present in 60% of all strains, and the distributions were similar among the ABU and CA-ABU groups. Genes encoding the UPEC toxins hemolysin (hlyA) and cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (cnf1) were also found in similar numbers in ABU strains (19% hlyA positive, 27% cnf1 positive) and CA-ABU strains (27% hlyA positive, 26% cnf1 positive). Several siderophore receptor-encoding genes were examined; the fyuA gene (encoding the yersiniabactin receptor) was the most prevalent (78% of ABU strains, 83% of CA-ABU strains), while the iutA (encoding the aerobactin receptor) and iroN (encoding the salmochelin receptor) genes were present in 35 to 50% of ABU and CA-ABU strains (the differences were not significant). The only statistically significant differences in prevalence were observed for the kpsMT II gene, specific for group II capsule biosynthesis, and the kpsMT K1 gene, which were more frequently associated with CA-ABU isolates than with ABU isolates (P = 0.005 and P = 0.002, respectively). Overall, the virulence factor loads of isolates from both the ABU and CA-ABU groups were similar. The median numbers of virulence factors for each phylogenetic group were as follows: for ABU strains, three virulence factors for group A, two for B1, seven for B2, and four for D; for CA-ABU strains, two virulence factors for group A, one for B1, seven for B2, and six for D.

Distribution of virulence genes among ampicillin- and cephalothin-resistant strains.

Ampicillin and cephalothin were the antibiotics to which the E. coli strains examined in this study were most commonly resistant. There was a significant difference in the median number of virulence factors between ampicillin-resistant and ampicillin-susceptible CA-ABU strains (six versus four; P = 0.017). Ampicillin-resistant CA-ABU E. coli had a significantly higher prevalence of the papG, flu, iutA, and kpsMT K5 virulence genes (Table 1). There was no difference in the median number of virulence factors between ampicillin-resistant and ampicillin-susceptible ABU strains. The comparison between cephalothin-resistant ABU and CA-ABU strains revealed the opposite distribution: the median numbers of virulence factors for cephalothin-resistant and cephalothin-susceptible ABU strains were 4 and 7, respectively (P = 0.004), while there was no difference between cephalothin-resistant and cephalothin-susceptible CA-ABU strains. Genes found more commonly in cephalothin-susceptible strains than in cephalothin-resistant strains included papG, focG, hlyA, cnf1, and iroN.

Phenotypic characterization of ABU and CA-ABU strains.

Many UTI E. coli strains carry virulence genes but fail to express the associated phenotype (26). Phenotypic assays were therefore performed to assess the expression of type 1 fimbriae, P fimbriae, and hemolysin (Table 1). The majority of fimH-positive ABU and CA-ABU strains agglutinated yeast cells (95% and 94%, respectively), demonstrating functional type 1 fimbrial expression. MRHA can be promoted by several different fimbrial types, including P, S, G, and M fimbriae, as well as the Afa/Dr family of adhesins (19). A higher percentage of ABU strains than CA-ABU strains showed an MRHA phenotype (34% and 15%, respectively; P = 0.003). More strains contained the papG allele than expressed the associated MRHA phenotype: 65% ABU and 29% CA-ABU papG-positive strains expressed MRHA (P = 0.002). Hemolysin assays were also performed to determine if strains possessing hlyA were hemolytic. Three hlyA-positive strains were nonhemolytic, while four strains that screened negative for hlyA were hemolytic. There was no significant difference in the number of hemolytic ABU strains (20%) and CA-ABU strains (18%).

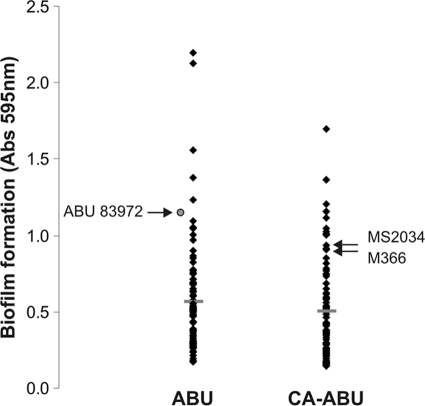

Biofilm formation.

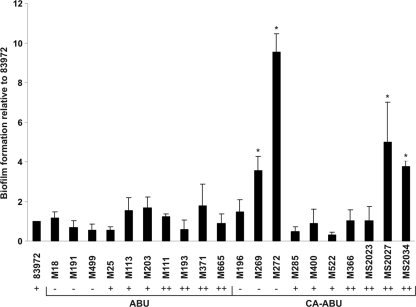

The ability of each ABU and CA-ABU E. coli isolate to form a biofilm was assessed using the microtiter plate biofilm assay. The CA-ABU strains displayed no significant difference from the ABU strains in the biofilm formation phenotype; 48% of CA-ABU and 59% of ABU strains formed a biofilm (Table 1). The mean biofilm formation values were similar for the ABU and CA-ABU groups (0.58 versus 0.54; P = 0.391) (Fig. 2). To examine how these results compared with biofilm formation on a catheter surface, we selected 10 ABU and 10 CA-ABU strains that encompassed the range of biofilm formation observed on PVC microtiter plates and examined their biofilm formation phenotype using a catheter biofilm assay. Under these experimental conditions, all of the ABU strains formed a biofilm equivalent to that produced by the prototype ABU E. coli strain, 83972 (Fig. 3). In contrast, four of the CA-ABU strains showed significantly higher levels of biofilm growth on the catheter surface than E. coli 83972 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Biofilm formation of ABU and CA-ABU E. coli isolates in synthetic urine. Strains were grown in PVC microtiter plates, washed, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. The absorbance at 595 nm correlates to the amount of biofilm formed. The results are the averages of three independent experiments, each with four replicates. Horizontal bars indicate the mean for each infection category. The CA-ABU E. coli isolates selected for transcriptome analysis (M366 and MS2034) and the relative position of ABU E. coli strain 83972 are indicated.

FIG. 3.

Biofilm formation of selected ABU and CA-ABU E. coli isolates on Foley latex catheters. Catheter sections were incubated with isolates in human urine, and biofilm formation was assessed via colony counting. Biofilm formation as the number of CFU per 1-cm catheter section was standardized to that of ABU E. coli strain 83972. The results are the averages of at least duplicates, with error bars indicating standard deviations. The four CA-ABU isolates which had significantly higher levels of biofilm growth than ABU E. coli 83972 are marked with asterisks (P < 0.05). The corresponding amount of biofilm growth for each strain on PVC microtiter plates is also indicated and expressed as either low (−), medium (+), or high (++).

Global gene expression of CA-ABU E. coli strains during biofilm formation.

To examine the similarities between the ABU and CA-ABU strains further, two CA-ABU strains (M366 and MS2034) with a limited repertoire of known adhesins and biofilm growth similar to that of prototype ABU E. coli strain 83972 were selected for further analysis (Table 2; Fig. 2). We examined the global gene expression profile of E. coli M366 and MS2034 during biofilm growth in pooled human urine as well as during planktonic growth in pooled human urine and in MOPS minimal medium. We then compared these data with those previously obtained for E. coli 83972 grown under the same conditions (11, 33).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of CA-ABU E. coli isolates selected for transcriptome analysis compared with those of ABU E. coli strain 83972a

| Characteristic | M366 | MS2034 | 83972 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesins | |||

| fimH | + | + | NF |

| papG I | − | − | − |

| papG II | − | − | − |

| papG III | − | − | NF |

| flu | − | − | + |

| focG | − | − | NF |

| sfaS | − | − | − |

| afa/draBC | − | − | − |

| mrkB | − | − | − |

| Toxins | |||

| hlyA | − | + | NF |

| cnf1 | − | + | + |

| Iron uptake systems | |||

| fyuA | + | + | + |

| iutA | − | − | + |

| iroN | − | + | + |

| Capsular types | |||

| kpsMT II | + | + | + |

| kpsMT III | − | − | − |

| kpsMT K1 | + | + | − |

| kpsMT K5 | − | − | + |

| Agglutination | |||

| Yeast | + | + | − |

| MRHA | − | − | − |

| Hemolysis | − | − | − |

| Biofilm formation on PVC | + | + | + |

| Motility | + | + | − |

| Antibiotic resistance | CEF | AMP/CEF | − |

All three strains are phylogenetic group B2. Abbreviations: NF, nonfunctional; CEF, cephalothin; AMP, ampicillin.

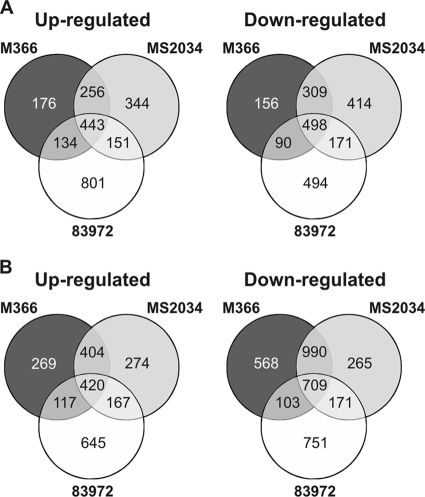

Transcriptomic analysis of M366 and MS2036 revealed that there was considerable overlap with E. coli 83972 in the genes up- or downregulated during biofilm growth versus planktonic growth in urine and MOPS minimal medium (Fig. 4). Comparing biofilm and planktonic growth in urine, 69% and 57% of the upregulated genes in M366 were also upregulated in MS2034 and 83972, respectively; under the same conditions, 77% and 57% of the downregulated M366 genes were shared with MS2034 and 83972, respectively. Overall, the three strains shared 443 genes significantly upregulated and 498 genes downregulated during biofilm growth in urine compared to the level of gene expression during planktonic growth in urine (data not shown). The three strains also shared 420 genes significantly upregulated and 709 genes downregulated during biofilm growth in urine compared to the level of gene expression during planktonic growth in MOPS (data not shown). The majority of the top 50 upregulated genes of E. coli M366 during biofilm growth compared to the level of gene expression during planktonic growth were also upregulated in strains MS2034 and 83972. These genes included those encoding cold and heat shock proteins, transcriptional regulators, enzymes, putative transport proteins, and iron uptake proteins.

FIG. 4.

Numbers of significantly up- and downregulated genes of E. coli strains 83972, M366, and MS2034 during biofilm growth compared to the level of gene expression during planktonic growth in urine (A) and MOPS minimal medium (B).

We also compared the gene expression profiles of M366, MS2034, and 83972 according to functional group classifications (Table 3). The two CA-ABU strains had similar numbers of genes up- or downregulated as ABU strain 83972 for most functional groups. The most upregulated functional groups were transcription, intracellular trafficking and secretion, and signal transduction mechanisms. In contrast, the most downregulated functional groups were translation; amino acid transport and metabolism; and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism.

TABLE 3.

Numbers of significantly up- and downregulated E. coli MG1655 genes in each functional group for the E. coli strains during biofilm growth in urine compared to the level of expression during planktonic growth in urine

| Functional group | No. (%) of genesa |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated genes in biofilm |

Downregulated genes in biofilm |

Total | |||||

| M366 | MS2034 | 83972 | M366 | MS2034 | 83972 | ||

| Amino acid transport and metabolism | 28 (9) | 39 (13) | 36 (12) | 93 (31) | 102 (34) | 85 (29) | 296 |

| Carbohydrate transport and metabolism | 39 (13) | 40 (13) | 37 (12) | 81 (27) | 94 (32) | 90 (30) | 298 |

| Cell cycle control, mitosis, and meiosis | 6 (19) | 9 (29) | 7 (23) | 8 (26) | 9 (29) | 6 (19) | 31 |

| Cell motility | 4 (4) | 7 (8) | 14 (15) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 91 |

| Cell wall/membrane biogenesis | 25 (13) | 28 (14) | 28 (14) | 45 (23) | 54 (27) | 37 (19) | 200 |

| Coenzyme transport and metabolism | 22 (20) | 24 (22) | 23 (21) | 16 (15) | 24 (22) | 16 (15) | 108 |

| Defense mechanisms | 2 (6) | 3 (9) | 9 (26) | 6 (17) | 9 (26) | 1 (3) | 35 |

| Energy production and conversion | 25 (10) | 21 (9) | 32 (13) | 71 (30) | 84 (35) | 74 (31) | 240 |

| Function unknown | 45 (18 | 52 (21) | 65 (26) | 50 (20) | 61 (25) | 43 (17) | 247 |

| General function prediction only | 48 (18) | 45 (17) | 68 (25) | 48 (18) | 61 (23) | 42 (16) | 269 |

| Inorganic ion transport and metabolism | 24 (15) | 32 (20) | 40 (25) | 22 (14) | 34 (21) | 18 (11) | 160 |

| Intracellular trafficking and secretion | 9 (25) | 13 (36) | 8 (22) | 5 (14) | 4 (11) | 7 (19) | 36 |

| Lipid transport and metabolism | 12 (17) | 12 (17) | 11 (15) | 12 (17) | 18 (25) | 17 (24) | 71 |

| Nucleotide transport and metabolism | 19 (24) | 19 (24) | 14 (18) | 10 (13) | 20 (26) | 13 (17) | 78 |

| Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones | 19 (16) | 25 (21) | 31 (26) | 22 (18) | 31 (26) | 19 (16) | 119 |

| Replication, recombination, and repair | 26 (16) | 30 (18) | 33 (20) | 20 (12) | 23 (14) | 18 (11) | 165 |

| Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism | 4 (7) | 5 (9) | 5 (9) | 16 (30) | 20 (37) | 16 (30) | 54 |

| Signal transduction mechanisms | 19 (16) | 19 (16) | 37 (32) | 19 (16) | 28 (24) | 11 (9) | 116 |

| Transcription | 65 (28) | 73 (31) | 74 (31) | 24 (10) | 35 (15) | 26 (11) | 235 |

| Translation | 40 (26) | 48 (31) | 26 (17) | 20 (13) | 22 (14) | 55 (35) | 156 |

| Not in COGsb | 175 (16) | 190 (18) | 217 (20) | 100 (9) | 164 (15) | 126 (12) | 1,065 |

| MG1655 (total of above genes) | 656 (16) | 734 (18) | 815 (20) | 692 (17) | 901 (22) | 723 (18) | 4,070 |

Values in boldface indicate the functional groups with the highest percentage of differentially regulated genes for each E. coli strain.

COGs, clusters of orthologous groups.

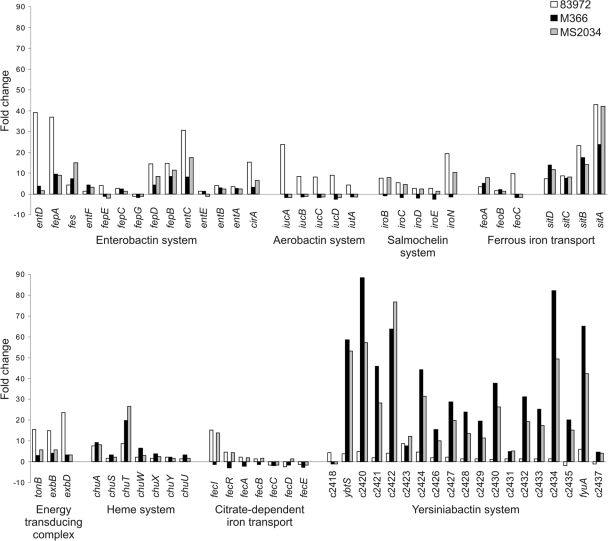

Upregulation of genes involved in iron uptake.

We specifically examined the transcription of genes involved in iron uptake by E. coli M366 and MS2034 during biofilm growth in urine and compared this to transcription during planktonic growth in MOPS minimal medium (Fig. 5). We observed a consistent pattern of increased gene expression, with the most strongly expressed genes being associated with the enterobactin, SitABCD, and yersiniabactin pathways (for example, 12/19 yersiniabactin genes and sitA were in the top 50 upregulated genes of M366 during biofilm formation compared to the gene expression during planktonic growth in MOPS). We next compared these data with the transcription profile for E. coli 83972 grown under the same conditions. Unlike E. coli 83972, E. coli M366 and MS2034 did not express the genes encoding aerobactin synthesis, which is consistent with our PCR typing of these strains as iutA negative. E. coli M366 was also iroN negative, and we did not detect transcription of the iroBCDEN genes. However, a major difference between the M366 and MS2034 CA-ABU strains and ABU E. coli strain 83972 was the level of expression of the yersiniabactin genes. Most of the genes involved in the yersiniabactin biosynthetic pathway, as well as the fyuA receptor-encoding gene, were significantly upregulated in E. coli M366 and MS2034 compared to the level of expression in E. coli 83972 (Fig. 5). To examine if the biosynthesis of yersiniabactin affected biofilm formation, we deleted the ybtS gene from E. coli M366 and MS2034. There was no difference in biofilm growth between wild-type and ybtS mutant strains, suggesting that while the level of transcription of the yersiniabactin biosynthesis genes was increased, this was not an absolute requirement for biofilm growth by E. coli M366 and MS2034 under the experimental conditions employed.

FIG. 5.

Fold changes in the levels of expression of iron acquisition genes of E. coli strains 83972, M366, and MS2034 during biofilm growth in urine compared to the levels during planktonic growth in MOPS minimal medium.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we compared E. coli strains that cause ABU and CA-ABU for differences in phylogenetic group, antibiotic resistance, virulence factors, and phenotypic properties (including biofilm formation). We then selected two CA-ABU strains and examined their global gene expression profile during biofilm growth in urine and compared this to the profile for the prototype ABU E. coli strain 83972.

Our analysis revealed that the majority of the ABU and CA-ABU strains belonged to phylogenetic groups B2 and D. These phylogenetic groups are most commonly associated with extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (2, 23, 30, 39). In support of this typing, we also observed a widespread occurrence of virulence factors for ABU and CA-ABU strains. Of the 18 UTI-associated virulence genes examined, there was a similar prevalence rate for all genes except the group II capsule-specific kpsMT II gene and the K1 capsule marker gene kpsMT K1, which were more prevalent within CA-ABU strains. This difference may reflect polysaccharide production during catheter colonization and biofilm growth by CA-ABU strains. Although there was no increased expression of capsule genes during biofilm growth in vitro for CA-ABU isolates M366 and MS2034, capsule production may be increased during host infection.

An interesting finding in our study was the observation that ABU and CA-ABU strains displayed very similar profiles with respect to antibiotic resistance. Ampicillin, cephalothin, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were the antibiotics to which resistance was most commonly detected. This is consistent with the use of these antibiotics to treat nosocomial and community-acquired UTIs. The low levels of resistance to gentamicin and quinolone antibiotics reflect their restricted use in Australia. Previous studies have epidemiologically linked antimicrobial resistance in extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli strains with reduced inferred virulence, often due to a decreased prevalence of phylogenetic group B2 within antimicrobial-resistant strains (20, 37, 44). In our study, cephalothin-resistant ABU strains had a lower median number of virulence factors and a decreased prevalence of phylogenetic group B2 compared to the cephalothin-susceptible ABU strains. However, analysis of group B2 ABU strains independently revealed that the difference in phylogenetic grouping between resistant and susceptible strains did not account for the difference in inferred virulence (five and seven median virulence factors for group B2 cephalothin-resistant and -susceptible strains, respectively; P = 0.016). Interestingly, resistance to ampicillin among the CA-ABU strains followed a reverse trend with respect to the median number of virulence factors (four versus six for susceptible and resistant strains, respectively). Overall, the relationship between antimicrobial resistance and virulence in our isolate collection varied not only with the antimicrobial agent but also with the strain clinical origin.

Since UTI E. coli strains may possess virulence genes but fail to express the associated phenotype, several virulence-related phenotypes were examined. ABU and CA-ABU E. coli strains differed only with regard to MRHA, possibly due to the decreased number of papG-positive CA-ABU strains capable of MRHA under the conditions used for testing. While P fimbriae are not associated with persistence in healthy or catheterized urinary tracts, they have been shown to enhance the establishment of bacteriuria by ABU strain 83972 (1a, 28, 48). Type 1 fimbriae, as determined by yeast agglutination, were expressed by the majority of the ABU and CA-ABU E. coli strains. This fimbrial type, unlike P fimbriae, is associated with catheter colonization and persistence in the catheterized urinary tract (28, 41). Furthermore, the introduction of a plasmid containing type 1 fimbrial genes increased catheter adherence of ABU strain 83972 up to 100-fold and improved its ability to prevent colonization by pathogenic E. coli (41).

CA-ABU results from the growth of bacterial biofilms on the inner surface of the urinary catheter. Although the molecular mechanisms of biofilm formation by E. coli in the catheterized urinary tract are not fully understood, surface adhesins such as type 1 fimbriae, type 3 fimbriae, and curli have been shown to contribute to biofilm growth (28, 29, 41, 43). In contrast, ABU E. coli strains are often associated with poor epithelial cell adhesion properties, and thus, the role of biofilm growth in colonization by these strains is less clear. Despite this, we found that the ABU and CA-ABU E. coli strains examined in this study possessed similar biofilm formation properties, as assessed by the PVC microtiter plate assay. Furthermore, we did not observe any significant difference in the adhesin gene repertoires of the ABU and CA-ABU strains. It is possible that some ABU strains form biofilms within the bladder without invoking host responses through direct attachment to mucosal cell receptors or that biofilm growth in the urinary tract leads to reduced virulence gene expression and thus a decreased interaction with the host. Indeed, we previously found several ABU strains able to adhere to bladder epithelial cells without provoking a cytokine response (26).

To examine biofilm growth in more detail, we also tested a representative selection of ABU and CA-ABU strains for their ability to form a biofilm on a catheter surface in pooled human urine. All of the ABU strains formed a biofilm similar to that formed by E. coli 83972 in this assay. Among the CA-ABU strains examined, four strains displayed a significant increase in the level of biofilm formation relative to that of E. coli 83972. We have previously reported that E. coli strains which cause symptomatic and asymptomatic infections display different biofilm formation phenotypes in human urine on polystyrene microtiter plates and catheter surfaces (6). The results presented here suggest that while there is some degree of congruence between these two assays, some differences are also apparent at the strain level.

We further examined biofilm formation for selected CA-ABU strains using global gene expression analysis with comparison to the gene expression of prototype ABU E. coli strain 83972. The two CA-ABU strains (M366 and MS2034) selected were from the same phylogenetic group as ABU 83972 and also had a limited adhesin repertoire. There was a significant overlap in the genes up- or downregulated during biofilm growth compared to the gene expression during planktonic growth for the three E. coli strains, with 420 to 709 genes being shared between the three strains, depending on the comparison.

We focused on the transcription of genes involved in iron uptake, since free iron is strictly limited in the urinary tract. Efficient iron uptake has been suggested to be a mechanism by which ABU strains grow in urine and are maintained in the bladder (31, 33). One widespread method for iron acquisition is the production of siderophores, low-molecular-mass iron-chelating compounds, and their associated membrane receptors (27). We examined the transcription of genes involved in iron uptake by CA-ABU E. coli M366 and MS2034 with comparison to the transcription by ABU strain 83972. The majority of these genes were upregulated during biofilm growth compared to their level of expression during planktonic growth in MOPS minimal medium for all three E. coli strains. Most notably, the genes involved in the synthesis and transport of the siderophore yersiniabactin (including the receptor-encoding fyuA gene) were upregulated up to 88-fold in strains M366 and MS2034, with smaller changes (up to 9-fold) occurring in strain 83972. Increased expression of the yersiniabactin pathway genes has previously been shown for ABU E. coli 83972 and VR50 during biofilm formation (10, 11) and for E. coli 83972 during colonization of the human urinary tract (31). Additionally, the yersiniabactin receptor FyuA is required for efficient biofilm formation by strains 83972 and VR50 in urine (10). However, when the yersiniabactin synthesis gene, ybtS, was deleted in strains M366 and MS2034, no change in biofilm growth was observed. Although the siderophore yersiniabactin appears to be important for biofilm formation by ABU strain 83972, this was not seen in the CA-ABU strains examined here. Of note also is the fact that E. coli 83972 is unable to express type 1, P, and F1C fimbriae (24, 32). In contrast, 93% and 34% of the ABU isolates in the present study expressed type 1 and MRHA fimbriae, respectively. This suggests that E. coli 83972 may use a different than that utilized strategy to colonize the urinary tract by other ABU strains.

Overall, the E. coli ABU and CA-ABU isolates in our collection had similar virulence profiles. Previous studies have compared the virulence properties of E. coli ABU isolates in noncatheterized patients to those of fecal isolates and isolates from patients with other clinical syndromes, including cystitis and pyelonephritis. Urinary isolates, including ABU E. coli, typically have higher inferred virulence than fecal isolates from healthy individuals (3, 18). Pyelonephritis isolates display the most consistent differences in virulence properties from those of ABU isolates, specifically, a higher prevalence of P-fimbrial genes and an increased ability to cause MRHA (18, 26). There is limited research on the virulence properties of E. coli isolates colonizing the catheterized urinary tract, despite the high numbers of catheterized patients and the high risk of developing bacteriuria once one is catheterized. The catheter literature has also been complicated by the lack of differentiation between bacterial isolates causing CA-ABU and catheter-associated symptomatic urinary tract infection (CAUTI), with guidelines recently being published to rectify this (13, 40). Comparative studies have been carried out mainly with patients with bladder dysfunction and intermittent catheterization where there were limited or no differences between the E. coli strains causing asymptomatic and symptomatic infections (8, 15). Since the insertion and presence of an indwelling catheter substantially change the urinary tract environment, we compared the virulence properties of E. coli isolates causing asymptomatic bacteriuria in catheterized and noncatheterized patients. An indwelling catheter predisposes an individual to infection by introducing bacteria into the bladder, causing damage to the uroepithelial mucosa, and providing a surface for biofilm formation and can also affect normal functioning and voiding of the bladder (7, 16). Despite this, we found little difference in the virulence properties between the E. coli ABU and CA-ABU isolates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Johnson (Princess Alexandra Hospital) for providing patient clinical data. We also thank all members of the Microbiology Lab, Princess Alexandra Hospital, for expert microbiological technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (grant 569676), the University of Queensland, the Danish Medical Research Council (grant 271-06-0555), and the Lundbeckfonden (grant R17-A1603).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 5 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Affymetrix Inc. 2004. GeneChip expression analysis technical manual 701023, revision 4. Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA.

- 1a.Andersson, P., I. Engberg, G. Lidin-Janson, K. Lincoln, R. Hull, S. Hull, and C. Svanborg. 1991. Persistence of Escherichia coli bacteriuria is not determined by bacterial adherence. Infect. Immun. 59:2915-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bingen, E., B. Picard, N. Brahimi, S. Mathy, P. Desjardins, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1998. Phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli strains causing neonatal meningitis suggests horizontal gene transfer from a predominant pool of highly virulent B2 group strains. J. Infect. Dis. 177:642-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, M. P. Alonso, and J. Blanco. 1996. Virulence factors and O groups of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with acute pyelonephritis, cystitis and asymptomatic bacteriuria. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 12:191-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clermont, O., S. Bonacorsi, and E. Bingen. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555-4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrières, L., V. Hancock, and P. Klemm. 2007. Specific selection for virulent urinary tract infectious Escherichia coli strains during catheter-associated biofilm formation. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 51:212-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garibaldi, R. A., J. P. Burke, M. R. Britt, W. A. Miller, and C. B. Smith. 1980. Meatal colonization and catheter-associated bacteriuria. N. Engl. J. Med. 303:316-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidoni, E. B. M., V. A. Dalpra, P. M. Figueiredo, D. D. Leite, L. M. J. Mimica, T. Yano, J. E. Blanco, and J. Toporovski. 2006. E. coli virulence factors in children with neurogenic bladder associated with bacteriuria. Pediatr. Nephrol. 21:376-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagberg, L., U. Jodal, T. K. Korhonen, G. Lidin-Janson, U. Lindberg, and C. Svanborg Edén. 1981. Adhesion, hemagglutination, and virulence of Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infections. Infect. Immun. 31:564-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hancock, V., L. Ferrières, and P. Klemm. 2008. The ferric yersiniabactin uptake receptor FyuA is required for efficient biofilm formation by urinary tract infectious Escherichia coli in human urine. Microbiology 154:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hancock, V., and P. Klemm. 2007. Global gene expression profiling of asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli during biofilm growth in human urine. Infect. Immun. 75:966-976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson, J. P., J. R. Crowley, J. S. Pinkner, J. N. Walker, P. Tsukayama, W. E. Stamm, T. M. Hooton, and S. J. Hultgren. 2009. Quantitative metabolomics reveals an epigenetic blueprint for iron acquisition in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hooton, T. M., S. F. Bradley, D. D. Cardenas, R. Colgan, S. E. Geerlings, J. C. Rice, S. Saint, A. J. Schaeffer, P. A. Tambayh, P. Tenke, and L. E. Nicolle. 2010. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:625-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hull, R., D. Rudy, W. Donovan, C. Svanborg, I. Wieser, C. Stewart, and R. Darouiche. 2000. Urinary tract infection prophylaxis using Escherichia coli 83972 in spinal cord injured patients. J. Urol. 163:872-877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hull, R. A., D. C. Rudy, I. E. Wieser, and W. H. Donovan. 1998. Virulence factors of Escherichia coli isolates from patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic bacteriuria and neuropathic bladders due to spinal cord and brain injuries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:115-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobsen, S. M., D. J. Stickler, H. L. T. Mobley, and M. E. Shirtliff. 2008. Complicated catheter-associated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21:26-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansen, T. E. B., M. Çek, K. G. Naber, L. Stratchouski, M. V. Svendsen, and P. Tenke. 2006. Hospital acquired urinary tract infections in urology departments: pathogens, susceptibility and use of antibiotics. Data from the PEP and PEAP-studies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 28:S91-S107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johanson, I. M., K. Plos, B. I. Marklund, and C. Svanborg. 1993. Pap, papG, and prsG DNA sequences in Escherichia coli from the fecal flora and the urinary tract. Microb. Pathog. 15:121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, J. R. 1991. Virulence factors in Escherichia coli urinary tract infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:80-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, J. R., M. A. Kuskowski, A. Gajewski, D. F. Sahm, and J. A. Karlowsky. 2004. Virulence characteristics and phylogenetic background of multidrug-resistant and antimicrobial-susceptible clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from across the United States, 2000-2001. J. Infect. Dis. 190:1739-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, J. R., P. L. Roberts, and W. E. Stamm. 1987. P fimbriae and other virulence factors in Escherichia coli urosepsis: association with patients' characteristics. J. Infect. Dis. 156:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson, J. R., T. A. Russo, P. I. Tarr, U. Carlino, S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, and A. L. Stell. 2000. Molecular epidemiological and phylogenetic associations of two novel putative virulence genes, iha and iroNE. coli, among Escherichia coli isolates from patients with urosepsis. Infect. Immun. 68:3040-3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, J. R., and A. L. Stell. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klemm, P., V. Roos, G. C. Ulett, C. Svanborg, and M. A. Schembri. 2006. Molecular characterization of the Escherichia coli asymptomatic bacteriuria strain 83972: the taming of a pathogen. Infect. Immun. 74:781-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindberg, U., L. A. Hanson, U. Jodal, G. Lidin-Janson, K. Lincoln, and S. Olling. 1975. Asymptomatic bacteriuria in schoolgirls. II. Differences in Escherichia coli causing asymptomatic and symptomatic bacteriuria. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 64:432-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mabbett, A. N., G. C. Ulett, R. E. Watts, J. J. Tree, M. Totsika, C. L. Y. Ong, J. M. Wood, W. Monaghan, D. F. Looke, G. R. Nimmo, C. Svanborg, and M. A. Schembri. 2009. Virulence properties of asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 299:53-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martínez, J. L., A. Delgado-Iribarren, and F. Baquero. 1990. Mechanisms of iron acquisition and bacterial virulence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 75:45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mobley, H. L. T., G. R. Chippendale, J. H. Tenney, R. A. Hull, and J. W. Warren. 1987. Expression of type 1 fimbriae may be required for persistence of Escherichia coli in the catheterized urinary tract. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2253-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ong, C. L. Y., G. C. Ulett, A. N. Mabbett, S. A. Beatson, R. I. Webb, W. Monaghan, G. R. Nimmo, D. F. Looke, A. G. McEwan, and M. A. Schembri. 2008. Identification of type 3 fimbriae in uropathogenic Escherichia coli reveals a role in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 190:1054-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Picard, B., J. S. Garcia, S. Gouriou, P. Duriez, N. Brahimi, E. Bingen, J. Elion, and E. Denamur. 1999. The link between phylogeny and virulence in Escherichia coli extraintestinal infection. Infect. Immun. 67:546-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roos, V., and P. Klemm. 2006. Global gene expression profiling of the asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli strain 83972 in the human urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 74:3565-3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roos, V., M. A. Schembri, G. C. Ulett, and P. Klemm. 2006. Asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli strain 83972 carries mutations in the foc locus and is unable to express F1C fimbriae. Microbiology 152:1799-1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roos, V., G. C. Ulett, M. A. Schembri, and P. Klemm. 2006. The asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli strain 83972 outcompetes uropathogenic E. coli strains in human urine. Infect. Immun. 74:615-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schembri, M. A., E. V. Sokurenko, and P. Klemm. 2000. Functional flexibility of the FimH adhesin: insights from a random mutant library. Infect. Immun. 68:2638-2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamm, W. E. 1991. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and prevention. Am. J. Med. 91:65S-71S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stamm, W. E., S. M. Martin, and J. V. Bennett. 1977. Epidemiology of nosocomial infections due to Gram-negative bacilli: aspects relevant to development and use of vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 136:S151-S160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Starčič Erjavec, M., M. Rijavec, V. Križan-Hergouth, A. Fruth, and D. Žgur-Bertok. 2007. Chloramphenicol- and tetracycline-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) exhibit reduced virulence potential. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 30:436-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundén, F., L. Håkansson, E. Ljunggren, and B. Wullt. 2006. Bacterial interference—is deliberate colonization with Escherichia coli 83972 an alternative treatment for patients with recurrent urinary tract infection? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 28:S26-S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi, A., S. Kanamaru, H. Kurazono, Y. Kunishima, T. Tsukamoto, O. Ogawa, and S. Yamamoto. 2006. Escherichia coli isolates associated with uncomplicated and complicated cystitis and asymptomatic bacteriuria possess similar phylogenies, virulence genes, and O-serogroup profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:4589-4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trautner, B. W. 2010. Management of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23:76-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trautner, B. W., M. E. Cevallos, H. G. Li, S. Riosa, R. A. Hull, S. I. Hull, D. J. Tweardy, and R. O. Darouiche. 2008. Increased expression of type-1 fimbriae by nonpathogenic Escherichia coli 83972 results in an increased capacity for catheter adherence and bacterial interference. J. Infect. Dis. 198:899-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ulett, G. C., J. Valle, C. Beloin, O. Sherlock, J. M. Ghigo, and M. A. Schembri. 2007. Functional analysis of antigen 43 in uropathogenic Escherichia coli reveals a role in long-term persistence in the urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 75:3233-3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vidal, O., R. Longin, C. Prigent-Combaret, C. Dorel, M. Hooreman, and P. Lejeune. 1998. Isolation of an Escherichia coli K-12 mutant strain able to form biofilms on inert surfaces: involvement of a new ompR allele that increases curli expression. J. Bacteriol. 180:2442-2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vila, J., K. Simon, J. Ruiz, J. P. Horcajada, M. Velasco, M. Barranco, A. Moreno, and J. Mensa. 2002. Are quinolone-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli less virulent? J. Infect. Dis. 186:1039-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warren, J. W., D. Damron, J. H. Tenney, J. M. Hoopes, B. Deforge, and H. L. Muncie, Jr. 1987. Fever, bacteremia, and death as complications of bacteriuria in women with long-term urethral catheters. J. Infect. Dis. 155:1151-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Warren, J. W., J. H. Tenney, J. M. Hoopes, H. L. Muncie, and W. C. Anthony. 1982. A prospective microbiologic study of bacteriuria in patients with chronic indwelling urethral catheters. J. Infect. Dis. 146:719-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wullt, B., G. Bergsten, H. Connell, P. Röllano, N. Gebratsedik, L. Hang, and C. Svanborg. 2001. P-fimbriae trigger mucosal responses to Escherichia coli in the human urinary tract. Cell. Microbiol. 3:255-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wullt, B., G. Bergsten, H. Connell, P. Röllano, N. Gebretsadik, R. Hull, and C. Svanborg. 2000. P fimbriae enhance the early establishment of Escherichia coli in the human urinary tract. Mol. Microbiol. 38:456-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zdziarski, J., C. Svanborg, B. Wullt, J. Hacker, and U. Dobrindt. 2008. Molecular basis of commensalism in the urinary tract: low virulence or virulence attenuation? Infect. Immun. 76:695-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]