Abstract

During murine peri-implantation development, the egg cylinder forms from a solid cell mass by the apoptotic removal of inner cells that do not contact the basement membrane (BM) and the selective survival of the epiblast epithelium, which does. The signaling pathways that mediate this fundamental biological process are largely unknown. Here we demonstrate that Rac1 ablation in embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies (EBs) leads to massive apoptosis of epiblast cells in contact with the BM. Expression of wild-type Rac1 in the mutant EBs rescues the BM-contacting epiblast, while expression of a constitutively active Rac1 additionally blocks the apoptosis of inner cells and cavitation, indicating that the spatially regulated activation of Rac1 is required for epithelial cyst formation. We further show that Rac1 is activated through integrin-mediated recruitment of the Crk-DOCK180 complex and mediates BM-dependent epiblast survival through activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt signaling pathway. Our results reveal a signaling cascade triggered by cell-BM interactions essential for epithelial morphogenesis.

All epithelial sheets and tubes rest upon a basement membrane (BM), a thin mat of specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) consisting of laminins, type IV collagens, perlecan, and nidogens. The BM provides essential survival signals to protect epithelial cells from apoptosis, in addition to its role in cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, and polarity orientation. In the developing chick retina, removal of the retinal BM by collagenase digestion resulted in severe apoptosis of retinal neuroepithelial cells (17). In mice, targeted deletion of the genes for the BM component laminins or perlecan caused BM defects and various degrees of apoptosis of cells that attach to the BM (34, 41, 42). Also, mammary epithelial cells can survive for a long period of time when grown on a reconstituted basement membrane derived from Engelbreth-Holmof Swarm (EHS) tumor (Matrigel), but they die by apoptosis when grown on plastic, fibronectin, or type I collagen despite their firm attachment on these substrates (2, 11, 36). A similar response of keratinocytes to BM type IV collagen versus non-BM matrix proteins was observed in bioengineered human skin equivalents (40). These results suggest that the BM provides a unique microenvironment for the survival of associated epithelial cells.

Embryoid body (EB) differentiation has been used to study epithelial morphogenesis and early embryogenesis. When cultured in suspension as small aggregates, mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells adhere strongly together and form spherical EBs. The outer cells of the EB differentiate to become endoderm cells, which secrete laminins, type IV collagen, perlecan, and other BM components that assemble into an underlying BM equivalent to the embryonic BM separating extraembryonic endoderm from the epiblast. Integrin α6β1 in the epiblast cells and integrin α5β1 in the endoderm cells redistribute from a pericellular location to a predominantly sub-basement membrane location (28). Following BM formation, the epiblast cells adjacent to the BM polarize to become a pseudostratified columnar epithelium (the epiblast epithelium), whereas the inner cells not in contact with the BM undergo apoptosis and are selectively removed by phagocytosis/autophagy, creating a proamniotic-like cavity. That the BM is essential for these sequential processes is evidenced by the observation that targeted deletion of the laminin γ1 gene in EBs blocks BM assembly, subsequent epiblast epithelialization, and then apoptosis-dependent cavitation (32, 42). These differentiation processes recapitulate peri-implantation development and provide a tractable in vitro model for the study of apoptosis and BM-dependent cell survival during epithelial morphogenesis.

While BM-dependent cell survival is often coupled with apoptotic removal of centrally located cells not in contact with the BM during morphogenesis of epithelial cysts such as mammary glandular acini and embryonic mouse egg cylinders (7, 29), the molecular mechanisms underlying this fundamental process are poorly understood. Elegant studies on teratocarcinoma cell-derived EBs have suggested that formation of an epithelial cyst as they develop is the result of the interplay of two signals (7). One is a death signal from the endoderm that induces apoptosis of the centrally located cells to create a cavity; the other is a rescue signal mediated by contact with the BM and is required for the survival of the newly formed epiblast epithelium. Subsequent studies have revealed that bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) is highly expressed in the endoderm and that expression of a dominant-negative (DN) BMP receptor in EBs blocked cavitation, suggesting BMP-2 to be a death factor (6). The survival signals from the interaction of the epiblast cells with the BM were studied by treating the EBs with polyclonal antiserum against membrane glycoproteins consisting of ECM adhesion receptors. The antiserum treatment induced programmed cell death in the BM-contacting epiblast layer. However, the identities of the receptors and the downstream signaling molecules involved have not been explored.

In this study, we utilized EBs differentiated from genetically modified ES cells to investigate the mechanisms of BM-dependent cell survival. We show that targeted deletion of the Rac1 gene in EBs leads to massive apoptosis of epiblast cells in contact with the BM. Rac1 is activated in a BM- and integrin-dependent fashion. Stable expression of wild-type Rac1 in the mutant EBs rescues the BM-contacting epiblast, while expression of a constitutively active Rac1 also blocks the apoptosis of inner cells and cavitation. These results suggest that the spatial activation of Rac1 is essential not only for BM-dependent epiblast survival but also for apoptosis-mediated cavitation. We further show that Crk mediates Rac1 activation by recruiting the Rac1-specific activator DOCK180 to the cell-BM adhesions and that the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt pathway acts downstream of Rac1 to promote BM-dependent survival. Collectively, our results have established a key role for Rac1 in embryonic epithelial morphogenesis and have uncovered a signaling pathway that mediates BM-dependent epithelial survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culturing of ES cells and embryoid bodies.

The ES cell lines used for this study were wild-type R1 and D3 ES cells and Rac1fl/−, Rac1-null, laminin γ1-null, and integrin β1-null ES cells (12, 42, 46). All the ES cells were cultured on mitomycin C-treated STO cells except for integrin β1-null ES cells, which were directly grown on plastic culture dishes (26). EB differentiation was initiated from ES cell aggregates in suspension culture as described previously (27). Integrin β1-null EBs were cultured in poly(hydroxyethyl methacrylate) [poly(HEMA)]-coated bacteriological petri dishes (28).

Antibodies and cDNA constructs.

Polyclonal antibodies (PAb) to cleaved caspase-3, pAkt (Ser473), pAkt (Thr308), Akt, pERK1/2, ERK1/2, pPAK1/2, and PAK1/2 were from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). Caspase-3 PAb was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Monoclonal antibodies (MAb) to laminin γ1 and Rac1 were from Upstate Biotechnology (Charlottesville, VA). MAb to Crk and PI3K were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). DOCK180 PAb and perlecan MAb were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Actin PAb, Flag tag MAb, and β-tubulin MAb were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Syntaxin-3 PAb was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). MUPP1 PAb was provided by Makoto Adachi of Kyoto University. Cy3-, Cy5-, and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA). Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged Rac1 protein bound to agarose beads was from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO). Laminin-111 was isolated from ESH tumor and provided by Peter Yurchenco of Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

The retroviral short hairpin RNA (shRNA) vectors targeting specifically to mouse DOCK180 and the control vector pSM2c were purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). The pCXN2-flag-CrkI/W169L-IRES-GFP vector, which expresses a dominant-negative CrkI, was kindly provided by Naoki Mochizuki of the National Cardiovascular Center Research Institute (Osaka, Japan) (33). The pcDNA3-myr-HA-Akt1 vector, encoding a myristoylated, constitutively active Akt1, was obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA) (37). Wild-type human Rac1 and constitutively active Rac1 G12V were subcloned by PCR from pcDNA3.1 (Missouri S&T cDNA Resource Center, Rolla, MO) to pEGFP-N1 and pCXN2-flag-IRES-GFP, respectively. pCAGGS-His-DOCK180, pCAGGS-His-DOCK180-DOHRS (residues 1 to 1714), and pCAGGS-His-DOCK180-del PS (residues 1 to 1472) were kindly provided by Michiyuki Matsuda of Kyoto University, Japan (23). All the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Stable transduction of ES cells.

For stable expression of wild-type Rac1 and Rac1 G12V, dominant-negative CrkI, and constitutively active Akt1, ES cells were transfected with the corresponding vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). Stable ES cell clones were selected with 500 μg/ml G418. Green fluorescent protein (GFP)-positive colonies were cloned and expanded on STO feeders. For knockdown of DOCK180, ecotropic 293 retroviral packaging cells were transfected with the retroviral vectors using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. The conditioned medium was mixed with an equal volume of fresh medium and was added to ES cells with 4 μg/ml Polybrene. After 48 h, the cells were selected with 3 μg/ml puromycin. Antibiotic-resistant colonies were cloned, expanded, and grown in the medium containing 3 μg/ml puromycin.

Immunofluorescence.

EBs were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde, imbedded in OCT compound, and sectioned on a Leica cryostat. EB processing and immunostaining were carried out as described previously (27). Slides were examined with a Nikon inverted fluorescence microscope (Eclipse TE2000), and digital images were acquired with an Orca-03 cooled charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (Hamamatsu) controlled by IP Lab software (Scanalytics). To quantify apoptosis of the epiblast epithelium, 5-day EBs were double immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 and BM perlecan. EBs positively stained for cleaved caspase-3 throughout a section of the epiblast layer were considered to be undergoing apoptosis of the epiblast epithelium. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

EBs were collected by settling by gravity, washed once in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (26).

Affinity pulldown assay.

To assay Rac1 activity, EB lysates were affinity purified using the p21 binding domain (PBD)-GST fusion protein as we described previously (14). Briefly, the pGEX-2T-PBD construct was expressed in Escherichia coli, and bacteria were lysed by sonication. The PBD-GST fusion protein was isolated with glutathione-agarose beads (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). EB lysates containing 1 mg of protein (bicinchoninic acid [BCA]; Pierce) were incubated with 15 μg of the bead-bound PBD-GST fusion protein at 4°C for 60 min. Affinity-purified proteins were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and immunoblotted using a Rac1 MAb. Bound primary antibody was detected with anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody and chemiluminescence detection reagents. The bands were assessed by densitometry (Image J), and the amount of PBD-bound Rac1 was compared with that of total cellular Rac1 determined by direct immunoblot analysis.

To identify Rac1 activators and effectors in differentiating EBs, the bead-bound nucleotide-free Rac1 G15A-GST or wild-type Rac1-GST fusion proteins loaded with either GTPγS (100 μmol/liter) or GDP (1 mmol/liter) were incubated with EB lysates at 4°C for 60 min. Proteins bound to the beads were washed six times and resolved by 8% SDS-PAGE. After transferred to PVDF membranes, the blots were probed with desired primary antibodies. The specific binding was detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and chemiluminescence detection reagents.

Transient transfection of epiblast cells and apoptosis assay.

Epiblast cells were isolated from 5-day DOCK180 knockdown EBs by brief incubation in deionized water for 20 s to selectively remove endoderm. The remaining EBs containing BMs and epiblast were dissociated with trypsin-EDTA. Isolated epiblast cells were cultured on laminin-111 (100 μg/ml)-coated culture dishes or glass coverslips overnight. The cells were transfected with pCAGGS-His-DOCK180, pCAGGS-His-DOCK180-DOHRS, pCAGGS-His-DOCK180-del PS, or pCAGGS-His using Lipofectamine 2000. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were used for immunostaining or apoptosis assay. To assess the contribution of the Crk binding site of DOCK180 to cell survival, the transfected cells were incubated with 100 μM H2O2 for 16 h and harvested for immunoblot analysis for cleaved caspase-3.

RESULTS

Rac1 is required for basement membrane-dependent epiblast survival.

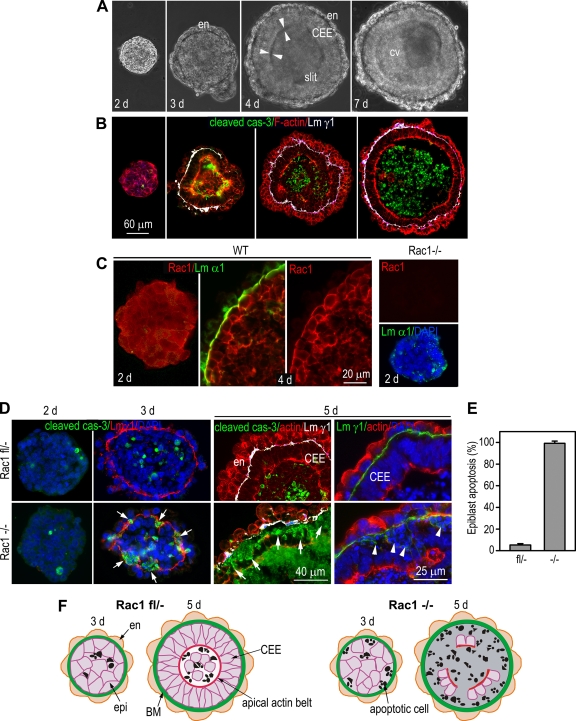

EBs differentiated from mouse ES cells have been used as a model to study epithelial morphogenesis and early embryogenesis (7, 25). When dispersed into small aggregates and cultured in suspension, ES cells undergo a process of compaction and form spherical EBs on day 2 in culture. Only a few apoptotic cells were found randomly in the EBs at this stage of differentiation as assessed by cleaved (activated) caspase-3 staining (Fig. 1 B). Later, an outer layer of endoderm develops on the EB surface, which is followed by the assembly of an underlying BM as demonstrated by linear staining of the laminin γ1 chain. As the EB further differentiates, the epiblast cells in contact with the BM polarize to form a pseudostratified columnar epiblast epithelium (CEE) which is characterized by the formation of an apical actin belt (Fig. 1A and B). Apoptosis of the inner apolar cells follows epiblast epithelialization and initially occurs in the area adjacent to the apex of the epiblast epithelium (Fig. 1B). At around day 4 in culture, slit-like clefts form at the apoptotic zone (arrowheads in Fig. 1A). Concurrently, apoptosis is also observed at the center of the EB, and the centrally located cells are eventually removed by programmed cell death, creating a proamniotic-like cavity. In contrast, very few apoptotic cells were observed in the epiblast epithelium which contacts the BM, demonstrating EB differentiation as a tractable model for BM-dependent survival (Fig. 1B) (7).

FIG. 1.

Rac1 ablation causes massive apoptosis of epiblast cells in contact with basement membrane. (A) Phase-contrast micrographs show live normal EBs cultured in suspension for 2 to 7 days. Endoderm (en) formed on the EB surface on day 3, and a columnar epiblast epithelium (CEE) was evident on day 4. Arrowheads point to slit-like clefts formed between the CEE and the remaining inner cells. After 7 days, a central cavity (cv) was created. (B) Frozen EB sections were immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 (cas-3) to identify apoptotic cells. Basement membrane (BM) was stained with anti-laminin γ1 chain (Lm γ1) antibody. The EBs were also stained for F-actin to identify the cell boundary. (C) Normal EBs (wild type [WT]) were immunostained for Rac1 and the laminin α1 chain. BM formation induced a redistribution of Rac1 from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane in BM-contacting cells. Rac1-null (−/−) EBs served as a negative control for Rac1 staining. (D) Rac1−/− and Rac1fl/− EBs were cultured for 2 to 5 days and immunostained for cleaved caspase-3, Lm γ1, and/or F-actin (actin). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Arrows point to apoptotic epiblast cells adjacent to the BM. Arrowheads indicate condensed and fragmented nuclei. (E) Five-day EBs with segmental, full-thickness apoptosis of the epiblast epithelium were counted and plotted as a percentage of total EBs examined (mean ± standard deviation [SD]). (F) Cartoons show the apoptotic patterns of Rac1-null and Rac1fl/− control EBs.

Prior studies using dominant-negative Rac1 suggest that Rac1 regulates epithelial cell polarization (35). To elucidate the role of Rac1 in epiblast epithelial morphogenesis, we first examined the spatial expression of Rac1 in EBs by immunofluorescence microscopy. Rac1 was mostly localized to the cytoplasm in 2-day EBs and was translocated from the cytoplasm to the plasma membrane of epiblast cells, especially those adjacent to the BMs in 4-day EBs, suggesting Rac1 activation by the BM (Fig. 1C). We then carried out a loss-of-function study by analyzing EBs with a targeted deletion of the Rac1 gene. In contrast to the results of dominant-negative Rac1 expression, the initiation of the basal and apical polarity of the epiblast was not affected (46). Rather, the most prominent phenotype of the mutant EBs was apoptosis of the epiblast cells in contact with the BM, especially the epiblast epithelium in differentiated EBs (Fig. 1D). The massive apoptosis of the BM-contacting epiblast was identified in all the null mutant EBs examined by DAPI staining of condensed and fragmented nuclei as well as positive staining of cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 1D and E). The apoptosis was detected as early as on day 3 after BM formation and was most evident on day 5 in culture. On day 5, we observed only a few clusters of surviving epiblast cells surrounded by apoptotic cells (Fig. 1D and F). By 7 days, the epiblast layer disappeared completely in most of Rac1-null EBs, whereas the fl/− control was perfectly normal (Fig. 2 B). These results demonstrate an essential role for Rac1 in BM-dependent embryonic epithelial survival.

FIG. 2.

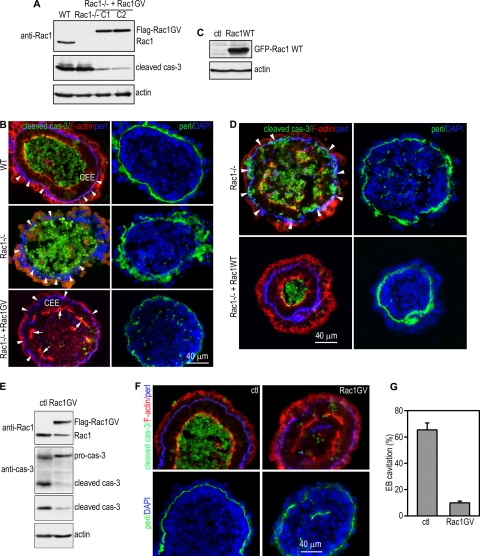

Rescue of Rac1-null EBs by stable expression of wild-type and constitutively active Rac1. (A) Wild-type (WT) EBs, and Rac1−/− EBs stably transfected with Rac1 G12V (Rac1GV) or the control vector (Rac1−/−) were cultured for 5 days. EB lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using Rac1 and cleaved caspase-3 antibodies. Actin served as a loading control. (B) Seven-day EBs were immunostained for cleaved caspase-3, F-actin, and perlecan. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Arrowheads point to the BM. Arrows point to apical F-actin staining in columnar epiblast epithelial (CEE) cells. (C) Rac1−/− EBs stably transfected with wild-type GFP-Rac1 (Rac1WT) or the control vector (ctl) were analyzed for the expression of the GFP-Rac1 fusion protein and cleaved caspase-3. Actin served as a loading control. (D) Five-day EBs were stained for cleaved caspase-3, F-actin, and BM perlecan. Arrowheads point to the BM. Transfection of Rac1−/− EBs with wild-type Rac1 completely rescued the epiblast epithelium without affecting the apoptosis of the inner cells. (E) Normal ES cells were stably transfected with Flag-tagged constitutively active Rac1, Rac1 G12V (Rac1GV), or the empty vector pCXN2 (ctl). Five-day EBs were analyzed by immunoblotting with Rac1, caspase-3 and cleaved caspase-3 antibodies. Actin served as a loading control. (F) Five-day wild-type EBs expressing Rac1 G12V or the empty vector were immunostained for cleaved caspase-3. F-actin was stained with rhodamine-phalloidin. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Expression of Rac1 G12V blocked apoptosis and cavitation. (G) Cavitated EBs were counted by phase-contrast microscopy and plotted as a percentage of total EBs examined (mean ± SD).

Interestingly, the level of apoptosis was very low in Rac1-null EBs on day 2 before BM formation and was comparable to that in fl/− control EBs (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, there was a close spatial relationship between apoptosis and BMs in the null mutant EBs. This was demonstrated by the fact that almost all the apoptotic cells positive for cleaved caspase-3 were detected adjacent to BMs, including small segments of BMs in the interior of the EBs (Fig. 1D; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These findings suggest that the apoptotic signal may be associated with the BM in Rac1-null EBs.

Rescue of Rac1-null EBs by stable expression of wild-type and constitutively active Rac1.

To confirm the apoptosis phenotype of Rac1-null EBs, we established stable ES cell lines expressing wild-type or a constitutively active Rac1 (Rac G12V) on the Rac1-null background (Fig. 2A and C). Rac1-null ES cell colonies, unlike their fl/− controls, had an irregular shape and a tendency to detach from feeders. Transfection of Rac1-null ES cells with either wild-type Rac1 or Rac1 G12V completely restored the mutant cell colonies to the normal morphology and prevented their detachment (data not shown). Analysis of EB differentiation showed that stable expression of wild-type or G12V mutant Rac1 in Rac1-null EBs fully rescued the apoptosis phenotype of the epiblast epithelium as assessed by immunostaining for cleaved caspase-3 and DAPI nuclear staining, confirming an essential role for Rac1 in BM-dependent epiblast survival (Fig. 2B and D). Of note, both immunoblotting and immunostaining for cleaved caspase-3 demonstrated that expression of the G12V mutant but not wild-type Rac1 also significantly inhibited the normal apoptosis of epiblast cells that do not contact with the BM, resulting in failure of cavitation (Fig. 2A and B). However, cell polarity still developed, as evidenced by the accumulation of the polarity markers syntaxin-3 and multiple PDZ domain protein (MUPP1) as well as F-actin on the apical side of the epiblast epithelium, although the staining was discontinuous. This suggests that complete polarization of epiblast cells may require apoptosis-mediated cavitation (Fig. 2B; see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). To verify the effect of Rac1 G12V expression on EB morphogenesis, we also stably transfected wild-type EBs with Rac1 G12V and found that it also blocked apoptosis of centrally located cells and cavitation (Fig. 2E, F, and G). Altogether, these results suggest that the spatially regulated activation of Rac1 in epiblast cells is required not only for the survival of the epiblast epithelium but also for apoptosis-dependent removal of the inner cells that do not contact with the BM. Forced activation of Rac1 in epiblast cells not in contact with the BM blocked cavitation and epithelial cyst formation.

Integrin β1 mediates basement membrane-dependent Rac1 activation.

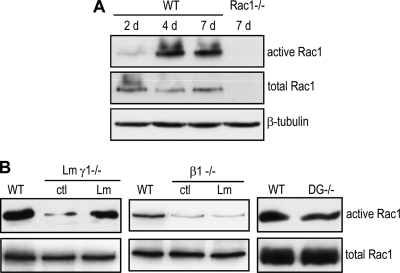

Previous studies using polyclonal antiserum against membrane glycoproteins have suggested that cell surface receptors for the ECM may be involved in BM-dependent epiblast survival (7). Integrins of the β1 subfamily and dystroglycans are major ECM receptors expressed during mouse peri-implantation development. We reasoned that binding of β1 integrins and/or dystroglycan to BM substrates might activate Rac1 and mediate epiblast survival. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed Rac1 activity in EBs using a pulldown assay with the p21 binding domain (PBD) of p21-activated kinase (PAK), which specifically interacts with the active, GTP-bound form of Rac1. In normal EBs, the time course experiments revealed that Rac1 activity was low on day 2 before BM formation and was markedly increased on day 4 after BM formation (Fig. 3 A). In contrast, despite constant levels of total Rac1 protein, the upregulation of Rac1 activity was not observed in laminin γ1-null EBs, which lack a BM (Fig. 3B) (42). However, exogenous laminin-111 treatment rescued Rac1 activation as the BM was reconstituted (26). Similarly, Rac1 activity was also significantly lower in integrin β1-null EBs even in the presence of laminin-111, which promotes BM formation (26) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, Rac1 activity remained high in dystroglycan-null EBs. These results suggest that BM formation activates Rac1 through β1 integrins during EB morphogenesis.

FIG. 3.

Rac1 is activated in a basement membrane- and integrin-dependent manner. (A) Wild-type (WT) and Rac1−/− EBs were cultured for 2 to 7 days, and Rac1 activation was determined by affinity pulldown assay using the PBD-GST fusion protein. Total Rac1 was analyzed by immunoblotting. β-Tubulin served as a loading control. The level of GTP-bound, active Rac1 was low at 2 days before BM formation and was significantly upregulated after BM formation at 4 days. (B) WT, Lm γ1−/−, integrin β1−/− (β1−/−), and dystroglycan−/− (DG−/−) EBs were cultured for 5 days with or without 25 μg/ml laminin-111 (Lm). Active Rac1 was determined by affinity pulldown assay. The level of Rac1 activation was markedly reduced in Lm γ1−/− EBs, which lack the BM. Laminin treatment reconstituted the BM and restored Rac1 activity. The level of Rac1 activation was also markedly decreased in integrin β1−/− EBs, and the activity was not restored by laminin treatment. Rac1 activity remained high in the absence of dystroglycan.

DOCK180 mediates BM-dependent Rac1 activation and epiblast survival.

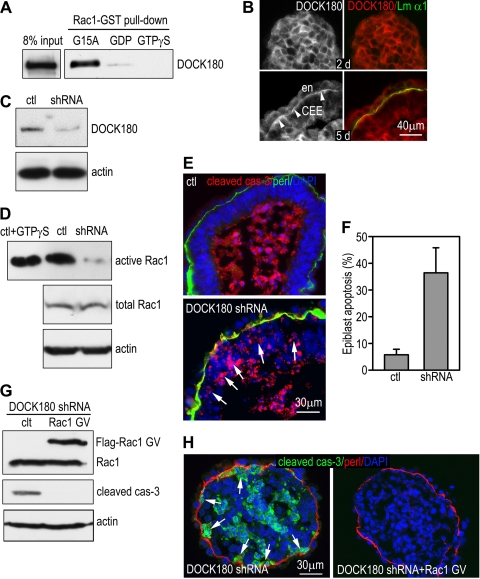

Rac1 shares many activators (guanine nucleotide exchange factors [GEFs]) and effectors with Cdc42. However, ablation of Cdc42 in EBs causes failure in epiblast polarization, whereas the predominant phenotype of Rac1-null EBs is loss of BM-dependent epiblast survival (46). This phenotype divergence suggests that these two GTPases might be activated by distinct GEFs. To seek the Rac1-specific activators that are downstream of integrins, we performed microarray gene expression profiling in differentiating EBs. We found that the mRNA for DOCK180, a focal adhesion component and an unconventional GEF for Rac1 (3, 5, 31), was significantly upregulated after BM formation in 5-day EBs. Affinity pulldown assay on 5-day EBs with Rac1-GST fusion proteins confirmed that DOCK180 interacted specifically with the nucleotide-free form of Rac1 (Rac1 G15A) but not GTPγS-loaded Rac1, which is in consistent with the previous report (Fig. 4 A). Immunostaining located DOCK180 close to cell-cell junctions prior to BM formation and to the epithelial-BM adhesion site in differentiating EBs (Fig. 4B). To test whether DOCK180 activates Rac1 and mediates BM-dependent epiblast survival, we generated stable ES cell lines that expressed short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) targeted specifically to the mouse DOCK180 mRNA. Immunoblot analysis of EBs revealed that DOCK180 expression was reduced by 72% in one of the DOCK180 knockdown clones compared to the control that expressed the empty vector (Fig. 4C). As a consequence, Rac1 activation was markedly inhibited (Fig. 4D). To assess the effect of DOCK180 knockdown on BM-dependent epiblast survival, we immunostained 5-day EBs for cleaved caspase-3 and BM perlecan. Sparse apoptotic cells were occasionally observed in the polarized epiblast layer of control EBs that expressed the empty vector (Fig. 4E). In contrast, extensive, full-thickness apoptosis of the epiblast epithelium was observed in 36.4% ± 9.4% of the knockdown EBs (versus the control; P < 0.01) (Fig. 4E and F). If Rac1 is downstream of DOCK180 in mediating BM-dependent epiblast survival, expression of a constitutively active Rac1 should rescue the epiblast phenotype. To test this, we stably transfected DOCK180 knockdown EBs with Rac1 G12V (Fig. 4G). Similar to the result of the Rac1-null rescue experiment, Rac1 G12V expression inhibited apoptosis of both the epiblast epithelium and the inner cells (Fig. 4H). These results suggest that the recruitment of DOCK180 to the cell-BM adhesion site leads to spatial activation of Rac1 and the protection of BM-adherent epiblast cells from apoptosis.

FIG. 4.

DOCK180 activates Rac1 and mediates BM-dependent epiblast survival. (A) Five-day normal EBs were analyzed by affinity pulldown assay using the Rac1 G15A- or the wild-type Rac1-GST fusion protein loaded with either GTPγS or GDP. DOCK180 selectively bound to nucleotide-free Rac1 G15A. (B) Normal EBs were cultured for 2 and 5 days and were immunostained for DOCK180 and the laminin α1 chain (Lm α1). DOCK180 was recruited to the BM zone (arrowheads). en, endoderm; CEE, columnar epiblast epithelium. (C) EBs stably transduced with DOCK180 shRNA or the empty vector (ctl) were cultured for 5 days. Immunoblots show reduced DOCK180 expression in the shRNA-transduced EBs. (D) Lysates of 5-day EBs were subjected to pulldown assay using PBD-GST agarose beads. GTPγS-loaded control lysates were used as a positive control. Knockdown of DOCK180 suppressed Rac1 activation without affecting Rac1 protein expression. (E) Control (ctl) and DOCK180 knockdown (DOCK180 shRNA) EBs were cultured for 5 days and immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 and perlecan. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Arrows point to the apoptotic epiblast cells adjacent to the BM. (F) The percentage of EBs with epiblast apoptosis was plotted (mean ± SD). (G) DOCK180 knockdown EBs were stably transfected with constitutively active Rac1 (Rac1 GV) and cultured for 5 days. Immunoblotting was performed for the expression of Flag-tagged Rac1 GV, cleaved caspase-3, and actin. (H) These EBs were also immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 (cas-3) and BM perlecan (perl). Nuclei were counterstained for DAPI. Expression of Rac1 GV in DOCK180 knockdown EBs not only rescued epiblast cells in contact with the BM but also blocked inner cell apoptosis and cavitation.

Crk recruits DOCK180 to epithelial-BM adhesions and mediates Rac1 activation and BM-dependent epiblast survival.

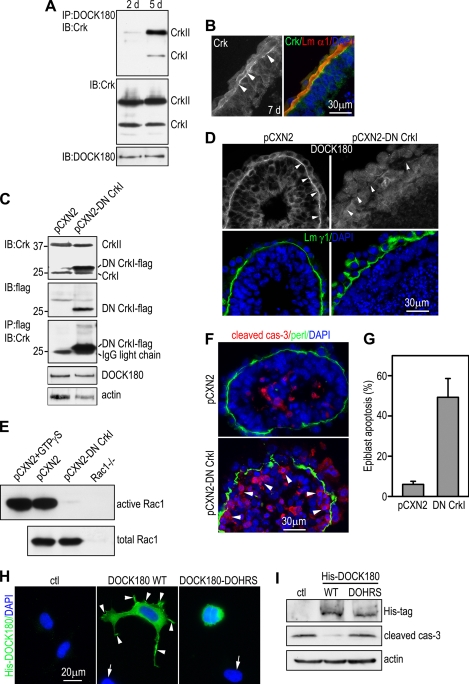

DOCK180 has been shown to interact with Crk, an adaptor protein found at focal adhesions in cultured fibroblasts (46). To test whether Crk might recruit DOCK180 to the epithelial-BM adhesion site during EB morphogenesis, we carried out coimmunoprecipitation on EBs before (2 days) and after BM (5 days) formation. DOCK180 formed a complex with CrkI/II only in 5-day EBs, although its expression levels were not affected by BM formation (Fig. 5 A). Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that both Crk and DOCK180 were recruited to the BM zone (Fig. 4B and 5B). Crk binds to DOCK180 through its SH3 domain (30). The W169L mutation in CrkI, which renders the SH3 domain nonfunctional, has been shown to act as a dominant-negative (DN) mutant for both CrkI and CrkII (20, 21). To test whether CrkI W169L expression might block DOCK180 recruitment to cell-BM adhesions and inhibit Rac1 activation, we established ES cell lines that expressed a Flag-tagged DN CrkI. Overexpression of CrkI W169L did not change the expression of the DOCK180 protein (Fig. 4C). However, it dissociated DOCK180 from the epithelial-BM adhesion site in 5-day EBs (Fig. 5D). Affinity pulldown assay demonstrated that Rac1 activity was significantly reduced in DN CrkI EBs compared to controls that expressed the vector alone (Fig. 5E). The inhibition of Rac1 activation by DN CrkI expression led to severe apoptosis of the epiblast cells adjacent to the BM as evidenced by cleaved caspase-3 staining (Fig. 5F). Nearly 50% of the DN CrkI EBs had at least one segment of the epiblast layer undergoing full-thickness apoptosis, whereas only 6.0% ± 1.6% of control EBs showed such changes (Fig. 5G, DN CrkI versus controls; P < 0.01). Collectively, these results suggest that Crk mediates DOCK180 recruitment to the epithelial-BM adhesion site and is required for BM-induced Rac1 activation and epiblast survival.

FIG. 5.

Crk recruits DOCK180 to epithelial-BM adhesions and mediates BM-dependent Rac1 activation and epiblast survival. (A) Normal EBs cultured for 2 and 5 days were used for coimmunoprecipitation (IP) assay. DOCK180 formed a complex with CrkI/II in 5-day but not 2-day EBs. IB, immunoblotting. (B) Seven-day EBs were immunostained for Crk and the laminin α1 chain (Lm α1). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Crk was located at the endoderm/epiblast-BM adhesion site (arrowheads). (C) Normal EBs were stably transfected with pCXN2 or pCXN2-CrkI/W169L, which encodes a Flag-tagged dominant-negative (DN) CrkI. Immunoblotting with anti-Crk and anti-Flag antibodies revealed that Flag-CrkI/W169L was expressed at a high level in 5-day EBs. Immunoprecipitation with anti-Flag antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-Crk antibody confirmed the transgene expression. CrkI/W169L expression did not change the protein level of DOCK180. (D) DN Crk and control EBs were cultured for 5 days and immunostained for DOCK180 and the Lm α1 chain. DN CrkI expression dissociated DOCK180 from the epithelial-BM adhesion site (arrowheads). (E) Lysates of 5-day EBs were analyzed by pulldown assay for active Rac1. Total Rac1 was detected by immunoblotting. Lysates of pCXN2 EBs loaded with GTPγS were used as a positive control, while those of Rac1−/− EBs were used as a negative control. Expression of DN Crk markedly inhibited Rac1 activation. (F) Five-day EBs were immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 and perlecan. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Overexpression of DN CrkI induced massive apoptosis of epiblast cells adjacent to the BM (arrowheads). (G) The percentage of EBs with epiblast apoptosis was plotted (mean ± SD). (H) DOCK180 knockdown epiblast cells were transiently transfected with His-tagged wild-type DOCK180 (DOCK180 WT), DOCK180-DOHRS (which lacks the Crk binding site), or the control vector. Cells were stained with His tag antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. His-tagged wild-type DOCK180 was concentrated in the membrane protrusions (arrowheads), whereas DOCK180-DOHRS was mostly localized to the cytoplasm. Arrows point to untransfected cells. (I) After transfection, the cells were treated with 100 μM H2O2 for 16 h, and the activation of caspase-3 was evaluated by immunoblotting for cleaved caspase-3 (cas-3). The expression of His-DOCK180 was confirmed by immunoblotting. Transfection with wild-type DOCK180 but not the mutant DOCK180 reduced H2O2-induced apoptosis of DOCK180 knockdown epiblast cells.

In addition to DOCK180, Crk has been reported to interact via its SH3 domain with C3G, a GEF for the small GTPase Rap1, and the nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Abl1. These interactions may indirectly regulate DOCK180 activity by affecting integrin signaling (13). To test whether DOCK180 is recruited to cell matrix adhesions through direct binding to the SH3 domain of Crk, we transfected epiblast cells isolated from DOCK180 knockdown EBs with either His-tagged wild-type DOCK180 or a mutant of DOCK180 that lacks the Crk binding site (23). Compared to wild-type controls, DOCK180 knockdown epiblast cells spread poorly on the laminin-111 substrate. Transfection with wild-type DOCK180 but not the Crk binding site mutant improved cell spreading (Fig. 5H). Immunofluorescence microscopy revealed that His-tagged wild-type DOCK180 was concentrated in membrane protrusions. In contrast, the Crk binding mutant was mostly localized in the cytoplasm. To assess the effect of transgene expression on cell survival, we treated the transfected cells with 100 μM H2O2, which has been suggested to participate in epiblast apoptosis during EB cavitation (19). H2O2 induced apoptosis of the DOCK180 knockdown cells transfected with the control vector as evidenced by an increase in cleaved caspase-3 (Fig. 5I). Expression of wild-type DOCK180 markedly attenuated caspase-3 activation, whereas the Crk binding mutant failed to rescue the epiblast cells from H2O2-induced apoptosis. These results suggest that the direct binding of DOCK180 to Crk is required for the adhesion/spreading and survival of epiblast cells.

The PI3K-Akt pathway is downstream of Rac1 and mediates BM-dependent epiblast survival.

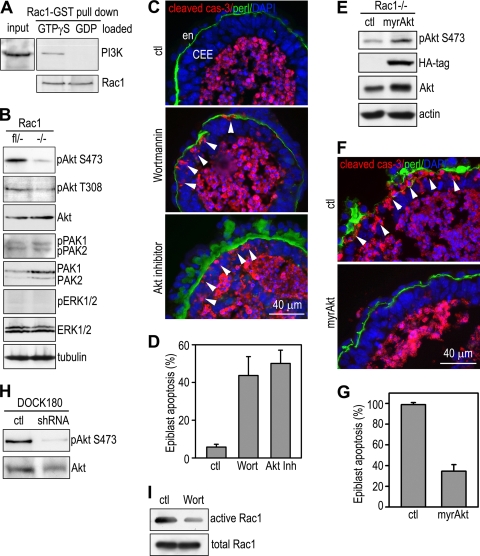

To determine the downstream effectors of Rac1 that mediate BM-dependent epiblast survival, we used GTPγs-loaded Rac1-GST fusion protein to pull down Rac1 effectors that have been implicated in the regulation of cell survival. We found that PI3K and PAK1/2 bound to GTPγs-loaded Rac1, suggesting that they are Rac1 effectors in differentiating EBs (Fig. 6 A and data not shown). PI3K-mediated signaling leads to the activation of Akt, which is activated by phosphorylation at Ser473 in the regulatory C terminus and Thr308 in the catalytic domain (44). To test whether Akt is activated during EB morphogenesis and whether the activation depends on Rac1, we detected Akt phosphorylation by immunoblotting using antibodies specific to phosphorylated Akt1. We found that in control EBs Akt1 was activated through phosphorylation at both Ser473 and Thr308. In the absence of Rac1, Akt1 phosphorylation was suppressed, especially at Ser473 (Fig. 6B). The reduction in Akt activation was specific, because the phosphorylation/activation of PAK1/2 and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) ERK1/2 showed little if any difference between Rac1-null and Rac1fl/− EBs (Fig. 6B). We did not observe any changes in the phosphorylation status of p38 MAPK in Rac1-null EBs (data not shown). These results suggest that the PI3K-Akt pathway but not PAK1/2 or the MAPKs may be involved in Rac1-dependent epiblast survival.

FIG. 6.

The PI3K-Akt pathway is downstream of Rac1 in mediating BM-dependent epiblast survival. (A) Lysates of 5-day normal EBs were analyzed by affinity pulldown assay using Rac1-GST agarose beads loaded with either GTPγS or GDP. The regulatory subunit of PI3K (p85) selectively bound to GTPγS-loaded Rac1. (B) Five-day Rac1−/− and Rac1fl/− EBs were analyzed by immunoblotting for phospho-Akt Ser473 (pAkt S473) and Thr308 (pAkt T308), phospho-PAK1/2 Thr144/141 (pPAK1/2), and phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK1/2), as well as total Akt, PAK1/2, and ERK1/2. pAkt S473 and T308 were reduced in Rac1−/− EBs, while the phosphorylation of PAK1/2 and ERK1/2 was unchanged in the absence of Rac1. (C) Normal EBs were cultured in the presence of 10 nmol/liter of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin, 150 nmol/liter AktI/II inhibitor, or the equal volume of solvent control (ctl) for 5 days. EBs were immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 and perlecan. Treatment of EBs with wortmannin (Wort) or AktI/II inhibitor (Akt Inh) caused apoptosis of the epiblast cells adjacent to the BM (arrowheads). en, endoderm; CEE, columnar epiblast epithelium. (D) The percentage of EBs with epiblast apoptosis was plotted (mean ± SD). (E) Rac1−/− ES cells were stably transfected with either pcDNA3 (ctl) or pcDNA3-myrAkt (myrAkt), which expresses myristoylated, HA-tagged constitutively active Akt1. Five-day EBs were subject to immunoblot analysis for active Akt (pAkt S473), HA tag, and total Akt. Actin served as a loading control. (F) EBs were cultured for 5 days and immunostained for cleaved caspase-3 and perlecan. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Expression of the constitutively active Akt1 in Rac1−/− EBs significantly reduced epiblast apoptosis compared to the vector control. Arrowheads point to apoptotic cells adjacent to the BM. (G) Epiblast apoptosis was quantified and plotted (mean ± SD). (H) Five-day DOCK180 knockdown (shRNA) and control (ctl) EBs were subject to immunoblotting for pAkt S473 and total Akt. Knockdown of DOCK180 reduced Akt activation. (I) Normal EBs were treated with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (Wort) or solvent control (ctl) for 5 days and analyzed using the pulldown assay for Rac1 GTP loading. PI3K inhibition significantly reduced Rac1 activation.

To elucidate the role of the PI3K-Akt pathway in BM-dependent epiblast survival, we pharmacologically inhibited the pathway using PI3K- and Akt-specific inhibitors. As shown in Fig. 6C, treatment of normal EBs with either 10 nmol/liter of the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin or 250 nmol/liter of the Akt1/2 inhibitor 1,3-dihydro-1-(1-(4-(6-phenyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-g]quinoxalin-7-yl)phenyl)methyl)-4-piperidinyl)-2H-benzimidazol-2-one hydrate trifluoroacetate resulted in marked apoptosis of epiblast cells in contact with the BM. Around 50% of the EBs treated with wortmannin (43.7% ± 10.0%) or Akt inhibitor (50.1% ± 7.0%) displayed segmental apoptosis of the epiblast epithelium, whereas similar apoptotic changes were observed in only 5.6% ± 1.5% of the solvent controls (Fig. 6D) (wortmannin or Akt inhibitor versus control, P < 0.01). These results suggest that the activation of the PI3K-Akt pathway is required for BM-dependent epiblast survival.

If the PI3K-Akt pathway mediates Rac1-dependent epiblast survival, the expression of constitutively active Akt should bypass the Rac1 requirement and rescue the Rac1-null phenotype. To test this possibility, we stably expressed a myristoylated, constitutively active mutant of Akt1 in Rac1-null EBs. Immunoblotting for phospho-Akt Ser473 showed a 4-fold increase in Akt activation when normalized to actin levels (Fig. 5E). Overexpression of the myristoylated Akt in Rac1-null EBs reduced epiblast apoptosis by 64.3% compared with the EBs that expressed a GFP control vector (Fig. 6F and G). Cavitation was slightly delayed in the myristoylated Akt-expressing EBs but was not prevented (data not shown). Altogether, these results suggest that Rac1 activates the PI3K-Akt pathway, which in turn mediates BM-dependent epiblast survival.

Since DOCK180 is required for Rac1 activation and BM-dependent epiblast survival in EBs, we reasoned that DOCK180 might also prevent epiblast apoptosis through the PI3K-Akt pathway. To test this, we examined Akt phosphorylation in DOCK180 knockdown EBs by immunoblot analysis. shRNA-mediated DOCK180 suppression markedly reduced Akt phosphorylation at Ser473, suggesting that Akt is activated downstream of DOCK180 (Fig. 6H). DOCK180 contains phosphoinositide binding sites and could be recruited to the plasma membrane through binding to phosphatidylinositol(3,4,5)-triphosphate (PIP3), a product of PI3K activation (4). To assess whether PI3K signaling might also facilitate Rac1 activation, we performed an affinity pulldown assay for GTP-bound Rac1 in EBs treated with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin. PI3K inhibition reduced Rac1 GTP loading without affecting Rac1 protein expression (Fig. 6I). These results suggest a positive feedback loop between DOCK180-Rac1 and Rac1-PI3K to enhance Akt activation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrate that Rac1 is essential for BM-dependent survival of the epiblast epithelium. Our results suggest a regulatory mechanism to explain how Rac1 is activated during embryonic epithelial morphogenesis and how activated Rac1 protects BM-contacting epiblast cells from apoptosis. In addition, our rescue experiment with constitutively active Rac1, which blocks essentially all apoptosis, indicates that the spatially restricted activation of Rac1 by the BM is required for epithelial cyst morphogenesis. Based on our data, we propose a model in which integrins recruit DOCK180 to the epithelial-BM adhesion sites through Crk. DOCK180 in turn activates Rac1, which mediates the survival of the epiblast epithelium by activating the PI3K-Akt pathway. In contrast, the inner cells that do not contact with the BM have low Rac1 activity and are selectively removed by apoptosis, resulting in the formation of a proamniotic-like cavity and an epithelial cystic structure.

Role of Rac1 in epithelial morphogenesis.

Rac1 belongs to the Rho family of small GTPases and is implicated in the regulation of many cellular processes, including actin cytoskeletal reorganization, migration, proliferation, and differentiation (10). Most of these functions are demonstrated in traditional cell cultures by overexpressing dominant-negative Rac1. This approach may cause nonspecific effects through neutralizing the GEFs for other GTPases (39). Dominant-negative Rac1 has also been used to study epithelial morphogenesis in three-dimensional cultures. Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) epithelial cells cultured in type I collagen gel form epithelial cysts with the apical surface facing the cavity. Expression of dominant-negative Rac1 caused the inversion of epithelial cell polarity and abnormal deposition of laminin (35). In mammary epithelial cells cultured on Matrigel, expression of dominant-negative Rac1 or Cdc42 blocked apical polarization, cyst formation, and lactation (1). In contrast to these findings, Rac1-null EBs are able to form a polarized epiblast epithelium as evidenced by the assembly of an apical actin belt and junctional complexes (apical polarization) and by the accumulation of integrins and dystroglycans to the BM zone (basal polarization) (46). However, the epiblast cells in contact with the BM undergo severe apoptosis in the absence of Rac1. These results uncover a novel role of Rac1 in epithelial morphogenesis and are in agreement with the phenotype of Rac1 knockout mice, which die at the peri-implantation stage because of defective germ layer formation (43). Hematoxylin-eosin staining of embryonic day 6.5 (E6.5) mutant embryos revealed pyknotic cells adjacent to the embryonic BM, although apoptosis was not evaluated. The analysis of Rac1-null EBs thus provides a possible explanation for the embryonic lethality of the mutant mice. Taken together, both the previous studies using dominant-negative Rac1 and our genetic analysis suggest a key role for Rac1 in epithelial morphogenesis despite the fact that it performs distinct functions in different tissue contexts.

Rac1 activation during embryonic epithelial morphogenesis.

Various extracellular stimuli can activate Rac1. During tissue morphogenesis, growth factor-mediated signaling and cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions likely contribute to Rac1 activation. While a low level of Rac1 activity was detected by affinity pulldown assay in normal EBs before BM formation and may be mediated by E-cadherin-mediated cell-cell interactions, Rac1 activity was significantly upregulated after BM formation. Significantly, this increase in Rac1 activation was abolished by targeted deletion of the laminin γ1 chain in EBs, which prevents BM formation, and furthermore, treatment of laminin γ1-null EBs with exogenous laminin both restored BM and rescued Rac1 activation. These results strongly suggest that laminin-mediated BM assembly activates Rac1 during EB morphogenesis.

Integrins and dystroglycans are two major ECM receptors in epithelial cells, and both have been implicated in the regulation of Rac1 activation (8, 49). Our previous work demonstrated that ablation of either integrin β1 or dystroglycan results in apoptosis of the epiblast epithelium (26). In this study, we found that Rac1 activity was low in integrin β1-null EBs both in the absence and in the presence of exogenous laminin, which improves BM assembly when added to the culture medium. This result is in line with the observation that Rac1 activity is reduced in integrin β1-null mammary epithelial cells and suggests that β1 integrins mediate BM-dependent Rac1 activation during EB differentiation. In contrast, BM-induced Rac1 activation was not altered in EBs deficient for dystroglycan. Therefore, dystroglycan may protect the epiblast epithelium from apoptosis through mechanisms other than Rac1 signaling.

Rho GTPases are activated by GEFs that catalyze GDP-GTP exchange. Previous studies have identified several Rac1 GEFs, including DOCK180, Sos1, Tiam1, Tiam2, and Vav, that might mediate integrin signaling. Among them, DOCK180 mRNA was significantly upregulated after BM formation during EB differentiation. Our affinity pulldown assay showed that DOCK180 specifically binds to nucleotide-free Rac1, suggesting that it is a Rac1 GEF in EBs. DOCK180 belongs to a family of unconventional GEFs for Rho GTPases. It was discovered as a binding partner of Crk, an adaptor protein found at focal adhesions (18). In the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, the DOCK180 homolog CED-5 (cell death abnormal 5) forms a ternary complex with CED-2/CrkII and CED-12/ELMO that activates CED-10/Rac and regulates cell migration and phagocytosis of apoptotic corpus (16, 38, 47). In the present study, we have provided the following evidence suggesting a novel role of the DOCK180-Crk complex in BM-dependent epiblast survival. First, DOCK180 forms a complex with Crk and is recruited to the integrin-based epithelial-BM adhesion sites. Second, overexpression of a mutant CrkI that blocks the Crk-DOCK interaction displaces DOCK180 from the epithelial-BM adhesion sites, inhibits Rac1 activation, and induces apoptosis of the epiblast cells in contact with the BM. Third, shRNA-mediated knockdown of DOCK180 also suppresses Rac1 activation and mimics the Rac1 apoptotic phenotype. Finally, wild-type DOCK180 but not the mutant DOCK180 that lacks the Crk binding site is recruited to membrane protrusions and rescues DOCK180 knockdown epiblast cells from apoptosis. These results suggest a mechanism by which integrin-BM ligation recruits Crk to the cell matrix adhesion site. The SH3 domain of Crk binds to DOCK180, which in turn activates Rac1 and provides a survival signal to the epiblast cells in contact with the BM. In the experiments with isolated epiblast cells, DOCK180 knockdown may cause apoptosis indirectly through reducing cell adhesion/spreading, although epiblast adhesion to the basement membrane was unchanged in DOCK180 knockdown EBs.

Recently it has been shown that DOCK180 knockout mice die around birth because of defective myoblast fusion (24). This phenotype is different from that of Rac1 ablation, which causes gastrulation failure. This phenotypic discrepancy suggests that DOCK180 cannot be the sole GEF for Rac1 during mouse embryogenesis. Our DNA microarray analysis revealed that DOCK2 is also expressed in EBs, although it is downregulated during differentiation. In addition, double deletion of DOCK180 and DOCK5 genes in mice leads to early embryonic lethality (24). DOCK2, DOCK5, and DOCK180 belong to the same subfamily that activates only Rac1. Therefore, DOCK2 and DOCK5 may compensate for the loss of DOCK180 in mice, although they are expressed at very low levels or silenced, respectively, in differentiating EBs. It is also possible that GEFs other than DOCK family members may activate Rac1 in addition to DOCK180 to mediate epiblast survival. Sos1, Tiam1, and Tiam2 are expressed in EBs, and their role in Rac1 activation and BM-dependent epiblast survival is unexplored.

Rac1 effectors in EB differentiation.

PI3K and its downstream effector Akt constitute a major survival pathway in various cell types. PI3K is a heterodimer consisting of a catalytic subunit, p110, and a regulatory subunit, p85. The latter contains a GTPase-responsive domain to which Rac1/Cdc42 bind and activate PI3K (48). PI3K-mediated signaling leads to the activation of Akt, which acts on multiple effectors in the survival/apoptosis pathways to protect cells from programmed cell death (15). In this study, we present four lines of evidence suggesting that the PI3K-Akt pathway is downstream of Rac1 to mediate BM-dependent epiblast survival. (i) The regulatory subunit of PI3K selectively binds to GTPγs-loaded Rac1, suggesting that PI3K is a Rac1 effector. (ii) Akt activation as detected with phosphorylation-specific antibodies is markedly reduced in Rac1-null EBs, indicating that Akt activation is controlled by Rac1. (iii) Pharmacological inhibition of PI3K or Akt in normal EBs induces apoptosis of cells in contact with the BM. (iv) Stable expression of myristoylated, constitutively active Akt in Rac1-null EBs partially rescues the apoptotic phenotype.

Despite the importance of the PI3K-Akt pathway in BM-dependent epiblast survival, our data suggest that other Rac1 effectors may also contribute to the cell survival, because overexpression of constitutively active Akt only delayed apoptosis and cavitation in Rac1-null EBs, whereas expression of constitutively active Rac1 effectively blocks the apoptosis of centrally located cells and the consequent cavitation. In our affinity pulldown assay, we also identified PAK1/2, which specifically binds to GTPγS-loaded Rac1 in differentiating EBs. However, PAK1/2 activation is not controlled by Rac1, because no change in activation-associated PAK1/2 phosphorylation was observed in Rac1-null EBs. Similarly, the activity of the MAPK ERK1/2 and p38 is low in differentiated EBs and is not affected by Rac1 ablation. Therefore, neither PAK1/2 nor MAPK ERK1/2 and p38 are likely to be the downstream effectors of Rac1 in mediating BM-dependent survival. There is evidence that c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs) are activated downstream of Crk-DOCK180-Rac1 signaling (9, 22) and that the JNK pathway is implicated in the regulation of apoptosis (45). It remains to be explored whether JNKs cooperates with PI3K-Akt to promote basement membrane-dependent epiblast survival.

In summary, our study establishes an essential role for Rac1 in BM-dependent epithelial survival and cavitation. We have also uncovered the signaling events that lead to Rac1 activation and mediate its prosurvival function. These results are important for our understanding of adhesion signaling and small GTPase regulation in the fundamental processes of tissue morphogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM081674) to S.L.

We thank Sean Lee for proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 May 2010.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://mcb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhtar, N., and C. H. Streuli. 2006. Rac1 links integrin-mediated adhesion to the control of lactational differentiation in mammary epithelia. J. Cell Biol. 173:781-793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boudreau, N., C. J. Sympson, Z. Werb, and M. J. Bissell. 1995. Suppression of ICE and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells by extracellular matrix. Science 267:891-893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugnera, E., L. Haney, C. Grimsley, M. Lu, S. F. Walk, A. C. Tosello-Trampont, I. G. Macara, H. Madhani, G. R. Fink, and K. S. Ravichandran. 2002. Unconventional Rac-GEF activity is mediated through the Dock180-ELMO complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:574-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cote, J. F., A. B. Motoyama, J. A. Bush, and K. Vuori. 2005. A novel and evolutionarily conserved PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-binding domain is necessary for DOCK180 signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 7:797-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cote, J. F., and K. Vuori. 2002. Identification of an evolutionarily conserved superfamily of DOCK180-related proteins with guanine nucleotide exchange activity. J. Cell Sci. 115:4901-4913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coucouvanis, E., and G. R. Martin. 1999. BMP signaling plays a role in visceral endoderm differentiation and cavitation in the early mouse embryo. Development 126:535-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coucouvanis, E., and G. R. Martin. 1995. Signals for death and survival: a two-step mechanism for cavitation in the vertebrate embryo. Cell 83:279-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Pozo, M. A., L. S. Price, N. B. Alderson, X. D. Ren, and M. A. Schwartz. 2000. Adhesion to the extracellular matrix regulates the coupling of the small GTPase Rac to its effector PAK. EMBO J. 19:2008-2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolfi, F., M. Garcia-Guzman, M. Ojaniemi, H. Nakamura, M. Matsuda, and K. Vuori. 1998. The adaptor protein Crk connects multiple cellular stimuli to the JNK signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95:15394-15399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etienne-Manneville, S., and A. Hall. 2002. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature 420:629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farrelly, N., Y. J. Lee, J. Oliver, C. Dive, and C. H. Streuli. 1999. Extracellular matrix regulates apoptosis in mammary epithelium through a control on insulin signaling. J. Cell Biol. 144:1337-1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fassler, R., M. Pfaff, J. Murphy, A. A. Noegel, S. Johansson, R. Timpl, and R. Albrecht. 1995. Lack of beta 1 integrin gene in embryonic stem cells affects morphology, adhesion, and migration but not integration into the inner cell mass of blastocysts. J. Cell Biol. 128:979-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feller, S. M. 2001. Crk family adaptors—signalling complex formation and biological roles. Oncogene 20:6348-6371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fera, E., C. O'Neil, W. Lee, S. Li, and J. G. Pickering. 2004. Fibroblast growth factor-2 and remodeled type I collagen control membrane protrusion in human vascular smooth muscle cells: biphasic activation of Rac1. J. Biol. Chem. 279:35573-35582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke, T. F., D. R. Kaplan, and L. C. Cantley. 1997. PI3K: downstream AKTion blocks apoptosis. Cell 88:435-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gumienny, T. L., E. Brugnera, A. C. Tosello-Trampont, J. M. Kinchen, L. B. Haney, K. Nishiwaki, S. F. Walk, M. E. Nemergut, I. G. Macara, R. Francis, T. Schedl, Y. Qin, L. Van Aelst, M. O. Hengartner, and K. S. Ravichandran. 2001. CED-12/ELMO, a novel member of the CrkII/Dock180/Rac pathway, is required for phagocytosis and cell migration. Cell 107:27-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halfter, W., M. Willem, and U. Mayer. 2005. Basement membrane-dependent survival of retinal ganglion cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 46:1000-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasegawa, H., E. Kiyokawa, S. Tanaka, K. Nagashima, N. Gotoh, M. Shibuya, T. Kurata, and M. Matsuda. 1996. DOCK180, a major CRK-binding protein, alters cell morphology upon translocation to the cell membrane. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:1770-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernandez-Garcia, D., S. Castro-Obregon, S. Gomez-Lopez, C. Valencia, and L. Covarrubias. 2008. Cell death activation during cavitation of embryoid bodies is mediated by hydrogen peroxide. Exp. Cell Res. 314:2090-2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichiba, T., Y. Hashimoto, M. Nakaya, Y. Kuraishi, S. Tanaka, T. Kurata, N. Mochizuki, and M. Matsuda. 1999. Activation of C3G guanine nucleotide exchange factor for Rap1 by phosphorylation of tyrosine 504. J. Biol. Chem. 274:14376-14381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ichiba, T., Y. Kuraishi, O. Sakai, S. Nagata, J. Groffen, T. Kurata, S. Hattori, and M. Matsuda. 1997. Enhancement of guanine-nucleotide exchange activity of C3G for Rap1 by the expression of Crk, CrkL, and Grb2. J. Biol. Chem. 272:22215-22220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiyokawa, E., Y. Hashimoto, S. Kobayashi, H. Sugimura, T. Kurata, and M. Matsuda. 1998. Activation of Rac1 by a Crk SH3-binding protein, DOCK180. Genes Dev. 12:3331-3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi, S., T. Shirai, E. Kiyokawa, N. Mochizuki, M. Matsuda, and Y. Fukui. 2001. Membrane recruitment of DOCK180 by binding to PtdIns(3,4,5)P3. Biochem. J. 354:73-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laurin, M., N. Fradet, A. Blangy, A. Hall, K. Vuori, and J. F. Cote. 2008. The atypical Rac activator Dock180 (Dock1) regulates myoblast fusion in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:15446-15451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, S., D. Edgar, R. Fassler, W. Wadsworth, and P. D. Yurchenco. 2003. The role of laminin in embryonic cell polarization and tissue organization. Dev. Cell 4:613-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li, S., D. Harrison, S. Carbonetto, R. Fassler, N. Smyth, D. Edgar, and P. D. Yurchenco. 2002. Matrix assembly, regulation, and survival functions of laminin and its receptors in embryonic stem cell differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 157:1279-1290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, S., and P. D. Yurchenco. 2006. Matrix assembly, cell polarization, and cell survival: analysis of peri-implantation development with cultured embryonic stem cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 329:113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu, J., X. He, S. A. Corbett, S. F. Lowry, A. M. Graham, R. Fassler, and S. Li. 2009. Integrins are required for the differentiation of visceral endoderm. J. Cell Sci. 122:233-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mailleux, A. A., M. Overholtzer, T. Schmelzle, P. Bouillet, A. Strasser, and J. S. Brugge. 2007. BIM regulates apoptosis during mammary ductal morphogenesis, and its absence reveals alternative cell death mechanisms. Dev. Cell 12:221-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsuda, M., S. Ota, R. Tanimura, H. Nakamura, K. Matuoka, T. Takenawa, K. Nagashima, and T. Kurata. 1996. Interaction between the amino-terminal SH3 domain of CRK and its natural target proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 271:14468-14472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meller, N., M. Irani-Tehrani, W. B. Kiosses, M. A. Del Pozo, and M. A. Schwartz. 2002. Zizimin1, a novel Cdc42 activator, reveals a new GEF domain for Rho proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 4:639-647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray, P., and D. Edgar. 2000. Regulation of programmed cell death by basement membranes in embryonic development. J. Cell Biol. 150:1215-1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagashima, K., A. Endo, H. Ogita, A. Kawana, A. Yamagishi, A. Kitabatake, M. Matsuda, and N. Mochizuki. 2002. Adaptor protein Crk is required for ephrin-B1-induced membrane ruffling and focal complex assembly of human aortic endothelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:4231-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen, N. M., D. G. Kelley, J. A. Schlueter, M. J. Meyer, R. M. Senior, and J. H. Miner. 2005. Epithelial laminin alpha5 is necessary for distal epithelial cell maturation, VEGF production, and alveolization in the developing murine lung. Dev. Biol. 282:111-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O'Brien, L. E., T. S. Jou, A. L. Pollack, Q. Zhang, S. H. Hansen, P. Yurchenco, and K. E. Mostov. 2001. Rac1 orientates epithelial apical polarity through effects on basolateral laminin assembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:831-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pullan, S., J. Wilson, A. Metcalfe, G. M. Edwards, N. Goberdhan, J. Tilly, J. A. Hickman, C. Dive, and C. H. Streuli. 1996. Requirement of basement membrane for the suppression of programmed cell death in mammary epithelium. J. Cell Sci. 109:631-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramaswamy, S., N. Nakamura, F. Vazquez, D. B. Batt, S. Perera, T. M. Roberts, and W. R. Sellers. 1999. Regulation of G1 progression by the PTEN tumor suppressor protein is linked to inhibition of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:2110-2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddien, P. W., and H. R. Horvitz. 2000. CED-2/CrkII and CED-10/Rac control phagocytosis and cell migration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:131-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt, A., and A. Hall. 2002. Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases: turning on the switch. Genes Dev. 16:1587-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segal, N., F. Andriani, L. Pfeiffer, P. Kamath, N. Lin, K. Satyamurthy, C. Egles, and J. A. Garlick. 2008. The basement membrane microenvironment directs the normalization and survival of bioengineered human skin equivalents. Matrix Biol. 27:163-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sher, I., S. Zisman-Rozen, L. Eliahu, J. M. Whitelock, N. Maas-Szabowski, Y. Yamada, D. Breitkreutz, N. E. Fusenig, E. Arikawa-Hirasawa, R. V. Iozzo, R. Bergman, and D. Ron. 2006. Targeting perlecan in human keratinocytes reveals novel roles for perlecan in epidermal formation. J. Biol. Chem. 281:5178-5187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smyth, N., H. S. Vatansever, P. Murray, M. Meyer, C. Frie, M. Paulsson, and D. Edgar. 1999. Absence of basement membranes after targeting the LAMC1 gene results in embryonic lethality due to failure of endoderm differentiation. J. Cell Biol. 144:151-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugihara, K., N. Nakatsuji, K. Nakamura, K. Nakao, R. Hashimoto, H. Otani, H. Sakagami, H. Kondo, S. Nozawa, A. Aiba, and M. Katsuki. 1998. Rac1 is required for the formation of three germ layers during gastrulation. Oncogene 17:3427-3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vanhaesebroeck, B., and D. R. Alessi. 2000. The PI3K-PDK1 connection: more than just a road to PKB. Biochem. J. 346:561-576. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner, E. F., and A. R. Nebreda. 2009. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9:537-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, X., S. Li, A. Chrostek-Grashoff, A. Czuchra, H. Meyer, P. D. Yurchenco, and C. Brakebusch. 2007. Cdc42 is crucial for the establishment of epithelial polarity during early mammalian development. Dev. Dyn. 236:2767-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu, Y. C., and H. R. Horvitz. 1998. C. elegans phagocytosis and cell-migration protein CED-5 is similar to human DOCK180. Nature 392:501-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng, Y., S. Bagrodia, and R. A. Cerione. 1994. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity by Cdc42Hs binding to p85. J. Biol. Chem. 269:18727-18730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou, Y. W., D. B. Thomason, D. Gullberg, and H. W. Jarrett. 2006. Binding of laminin alpha1-chain LG4-5 domain to alpha-dystroglycan causes tyrosine phosphorylation of syntrophin to initiate Rac1 signaling. Biochemistry 45:2042-2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.