Abstract

Classical sex steroid receptors (SRs) localize at the plasma membranes (PMs) of cells, initiating signal transduction through kinase cascades that contribute to steroid hormone action. Palmitoylation of the SRs is required for membrane localization and function, but the proteins that facilitate this modification and subsequent receptor trafficking are unknown. Initially using a proteomic approach, we identified that heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) binds to a motif in estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and promotes palmitoylation of the SR. Hsp27-induced acylation occurred on the ERα monomer and augmented caveolin-1 interactions with ERα, resulting in membrane localization, kinase activation, and DNA synthesis in breast cancer cells. Oligomerization of Hsp27 was required, and similar results were found for the trafficking of endogenous progesterone and androgen receptors to the PMs of breast and prostate cancer cells, respectively. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of Hsp27 prevented sex SR trafficking to and signaling from the membrane. These results identify a conserved and novel function for Hsp27 with potential as a target for interrupting signaling from membrane sex SRs to tumor biology in hormone-responsive cancers.

Steroid hormones bind nuclear receptors in cells, thereby modulating gene transcription that subsequently affects organ development and functions (2). More recently, it has been established that extranuclear pools of steroid receptors (SRs) exist in cytoplasmic organelles and localize to the plasma membranes (PMs) of many cells (reviewed in reference 14). At the PM, steroid binding rapidly induces signal transduction, potentially contributing to the proliferation and survival of hormone-responsive tumor cells (27). As examples, estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and progesterone receptor B (PRB) have been found at the PMs of breast cancer cells (27, 33), where they may contribute to cell proliferation. Membrane-initiated signals, such as kinase activation, cause the phosphorylation of substrate proteins to alter their cellular location and functions. As a result, membrane-localized SR signaling in bone, cardiovascular, and central nervous systems has been implicated for the in vivo actions of various steroids (14).

At the membrane, steroid receptors exist primarily in caveola rafts (18, 20). Here, the receptors physically interact with multiple signal molecules and scaffold and linker proteins, and effect activation of discrete G protein α and βγ subunits (14, 25). G protein activation results in the transduction of cyclic nucleotides, calcium, and kinase cascades that occur in seconds to minutes after receptor binding by ligand (7, 25). The localization of all sex SR to the PM rafts requires a dynamic process of palmitoylation at a highly conserved sequence in the respective E (ligand binding) domains (33). Depalmitoylation of at least ERα and ERβ also rapidly occurs, but the consequences of this are not well understood (11). Acylation appears to occur in the cytoplasm, where palmitoylation facilitates a productive interaction with the caveolin-1 protein, an interaction that is required for subsequent trafficking of SR to the plasma membrane (37). However, the identities of proteins that facilitate sex SR palmitoylation and membrane translocation are currently unknown.

Signaling by SR at the PM has also been implicated in pathophysiological processes. Increased localization of ERα at the PM and the resulting augmented kinase activity have been reported to underlie some aggressive breast cancers (24) or resistance to tamoxifen actions in this malignancy (8). Thus, the ability to modulate extranuclear SR signaling may provide novel prevention or treatment strategies for cancer or cardiovascular diseases (21). This strategy depends upon identifying the key proteins that facilitate SR trafficking to the PM.

Here, we describe a proteomic approach for identifying proteins that interact with ERα and facilitate membrane translocation of this SR to the PM. This and additional approaches identified heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) as such a protein, subsequently found to be required for trafficking of all sex steroid receptors to the PM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Wild-type (WT) PcIHA27 and mutant Hsp27 plasmids with deletions of amino acids 5 to 23, 18 to 30, 28 to 79, and 50 to 79 were kind gifts from Hebert Lambert and Jacque Landry (42). Dimer mutant ERα (L405E) was from Geof Greene (38). Antibodies to ERα, androgen receptor (AR), progesterone receptor (PR), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), 5′-nucleotidase (5′NT), transportin, nuclear transfer factor 2 (NTF-2), β-COP, caveolin-1, and Hsp27 were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Myelin basic protein (MBP) substrate for ERK kinase activity was from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). Phospho-specific antibody to Ser473 of AKT was from Upstate Biotechnology. PD 98059 (MEK inhibitor) and wortmannin (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase [PI3K] inhibitor) were from Calbiochem.

Isolation of palmitoylation motif interacting proteins.

MCF-7 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)-Ham's F-12 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) to 90% confluence. MCF-7 cells (109) underwent lysis in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, protease inhibitor cocktail, and 0.2% Triton X-100). The cytoplasmic-membrane (CM) fraction from the lysate was isolated by centrifugation at 6, 000 × g with a Beckman GS-6R tabletop centrifuge, eliminating the nuclear fraction. The CM fraction was split and equally applied for 1 h to affinity columns packed with protein A agarose beads conjugated to either ERα palmitoylation motif peptide (FVCLKSIII)- or scrambled-peptide (IKSLVCIFL)-conjugated beads, using proprietary binding buffer (Pierce). The columns were washed, and bound peptide was eluted with proprietary low-pH buffer (Pierce). After centrifugation, the supernatant(s) was run over a 9,000-Da-cutoff column to eliminate small and denatured proteins. The remaining eluted proteins from the two columns were separated on a 10% gel by SDS-PAGE, and the gel was stained with Imperial stain (Pierce) and then destained. The protein band at ∼27 kDa from the specific affinity column was cut out and sent to the Medical College of Wisconsin mass spectrometry facility (Milwaukee, WI). Trypsin digests of the band yielded multiple small peptides that were further analyzed by electrospray matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. Data analysis was carried out in Wisconsin using the Sequest search engine.

Cell culture and experiments.

Most cell lines were from ATCC. MCF-7 cells were grown at 37°C in 100-mm dishes to 75% confluence, using DMEM-Ham's F-12 medium, 10% FBS, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Invitrogen). NIH 3T3, LNCaP, or CHO cells were similarly cultured. At 24 h prior to experiments, the cells were switched to charcoal-stripped serum to remove any steroids in the media. For experiments detecting PR, MCF-7 cells were always cultured in media with non-charcoal-stripped FBS.

For protein knockdown, cells were transfected to express small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to Hsp27, Hsp90 (Qiagen-Xeragon), or Bap31 (Santa Cruz). The target sequences were as follows: for Hsp27, AACGAGATCACCATCCCAGTC; for Hsp90, AAACCCAGACCCAAGACCAAC; and for Bap31, GAGAAUGACCAGCUCAAGATT. Twenty-three micrograms of siRNA was used in each well of 6-well plates or 10 to 15 μg per 100-mm dish of cells. Protein immunoblot analyses at 48 h posttransfection confirmed selective protein decreases.

Palmitoylation of sex steroid receptors was carried out as described previously (33). MCF-7 or LNCaP cells were grown on 100-mm-diameter dishes in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-Ham's F-12 nutrient mixture medium without phenol red. The cells were synchronized without serum overnight and then labeled with [3H]palmitic acid (0.5 mCi/ml) for 4 h in the absence of sex steroids. The cells were lysed in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, protease inhibitor cocktail, and 0.2% Triton X-100), and nuclear pellets were collected by low-speed centrifugation (6,000 rpm). Cytoplasmic extracts were immunoprecipitated for 2 h at 4°C with antibodies to ERα (MC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), PR (C-20; Santa Cruz), or AR (C-19; Santa Cruz), each conjugated to protein A Sepharose. The immunoprecipitates were washed and then eluted with 4× Laemmli sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol after boiling for 5 min. Samples were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, followed by fluorography and autoradiography.

Proliferation was reflected by thymidine incorporation (DNA synthesis) in response to 10 nM E2 with or without kinase inhibitors, 10 μM PD98059 (MEK), or 100 nM wortmannin (PI3K), determined at 24 h as described previously (37, 39). Under some conditions, siRNAs were transfected 48 h before the study.

Protein localization and protein-protein interactions.

To determine ERα abundance in cell subfractions, MCF-7 cells were scraped and then pelleted by centrifugation. The pellets were suspended in cold buffer (10 nM Tris with 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors), transferred to a cool Dounce homogenizer, and homogenized. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4°C for 1 h, and the supernatant was saved as the cytosolic fraction. Pellets were resuspended in cold, high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 400 mM NaCl, and protease inhibitors) for 1 h and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4°C. The supernatants were used as the nuclear fraction. The cytosolic fractions were then subjected to ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g) at 4°C for 1 h. The pellet contained the plasma membranes and after resuspension was again subjected to ultracentrifugation. The membrane receptors were solubilized by adding 0.2% NP-40.

Both nuclear and membrane fractions underwent electrophoretic separation using a 10% reducing gel, followed by transfer to nylon and immunoblotting for ERα (antibody MC-20; Santa Cruz). The procedure was done with randomly cycling cells, as we previously described (33). IgG antibody at each stage yielded no blots. To determine the purity of the cell fractions, immunoblotting with antibodies to 5′-nucleotidase (5′NT) (plasma membrane protein), transportin and nuclear transfer factor 2 (NTF-2) (nuclear proteins), and β-COP (endosomal/Golgi marker protein) was also performed.

For the oligomerization and other experiments, Hsp27 WT or various mutant plasmids were cotransfected with ERα into NIH 3T3 or CHO cells cultured in the absence of ligand, the cells recovered overnight, and the association of each Hsp27 with ERα was determined by immunoprecipitation of ERα followed by immunoblot analysis of Hsp27 and then in reverse order. Palmitoylation was carried out after transfection as described above.

Cell localization of SR proteins was also determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. MCF-7 or LNCaP prostate cancer cells were cultured on poly-d-lysine-coated, 35-mm glass bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA). After undergoing siRNA transfection or other treatment, the cells were recovered over 24 to 48 h, depending on the cell type, and cultured to approximately 50% confluence. The cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 prior to specific ER, PR, or AR antibody staining. Nonspecific IgG antibody served as a control (data not shown). Areas of low cell density were selected for microscopy to visualize the unfurled membranes and expression of SR. Under each condition, 200 cells were examined and the study was repeated.

To determine the overlap of endogenous Hsp27 and ERα, MCF-7 cells were cultured in the absence of ligand and then fixed as described above. Incubation with first antibody to either protein was followed by incubation with second antibody conjugated to fluorescein (green) or Texas Red (red) (Vector Labs, Inc.) or a combination of the two antibodies to determine overlap. IgG antibody incubation yielded no protein detection.

Kinase signaling.

ERK activity in MCF-7 or LNCaP cells expressing endogenous membrane SR was determined at 8 min after exposure to steroid ligand. The activity of immunoprecipitated and protein-normalized ERK was directed against the myelin basic protein substrate in an in vitro assay, as described previously (35). PI3K activity was determined as phosphorylation of AKT at serine 473 (32, 34) after a 15-min exposure of the cells to steroid. The statistical analysis of the data shown in the bar graphs is based on three experiments combined. The means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) of results for each condition were calculated and subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) plus Schefe's test. Significance of difference was designated at P values of <0.05.

Image acquisition.

The immunofluorescent microscopic images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse TE-200 scope with magnification from ×200 to ×400 at room temperature. A Diagnostic Instruments camera, model 3.2.0, was used in conjunction with Spot Advance software to capture and transfer images to the computer. Texas Red (red)- and fluorescein (green)-conjugated secondary antibodies were used for fluorescence visualization.

RESULTS

Proteomic approach for identifying proteins that facilitate ERα trafficking to the PM.

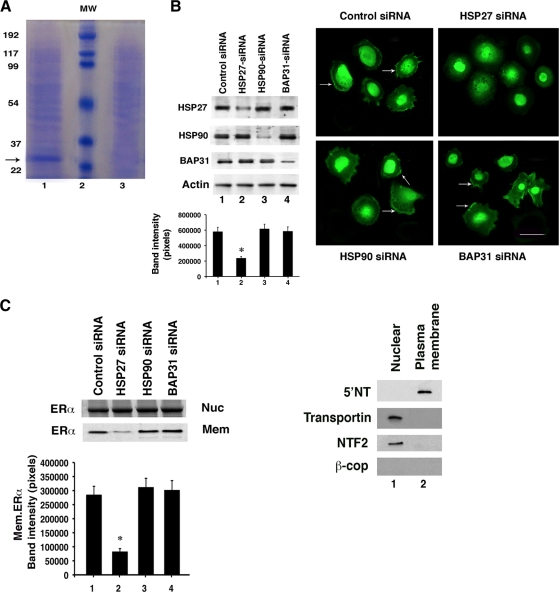

We previously identified a 9-amino-acid sequence in the ligand binding (E) domains of ERα, ERβ, PR, and the androgen receptor (AR) that was highly conserved. By mutational analysis, this motif was shown to be required for sex SR palmitoylation, membrane translocation, and rapid signaling (33). In contrast, nuclear ERα was not palmitoylated, indicating that this modification is specific for PM trafficking by the SR. We therefore had synthesized ERα palmitoylation motif and scrambled motif peptides in order to construct specific and nonspecific protein A agarose affinity columns, respectively. Since endogenous ERα translocates to the PM and signals in MCF-7 breast cancer cells, we isolated the cytoplasmic/membrane protein fraction from these cells and applied the material to both columns. Elution of proteins that bound the specific affinity bead-peptide column revealed only one prominent band (∼27 kDa) after separation by SDS-PAGE; this band was not seen in the eluate from the nonspecific affinity column (Fig. 1 A). Mass spectrometry analysis of peptides derived from the single band identified two proteins that were far more abundant than other identified proteins. As seen in Table 1, Hsp27 was identified with 91% of the protein covered by the trypsin-digested peptides. Much less abundant were Bap31 (endoplasmic reticulum protein)-derived peptides, and the coverage was only 32% of the protein.

FIG. 1.

Hsp27 promotes ERα trafficking to the plasma membrane. (A) Protein bands were eluted from either a palmitoylation motif peptide affinity column (lane 1) or a scrambled peptide column (lane 3) and separated by SDS-PAGE. “MW” represents molecular mass markers, with sizes in kDa on the left. The arrow refers to an abundant protein band subsequently subjected to trypsin digest and mass spectrometry analysis. (B) (Left) siRNA knockdown of Hsp27, Hsp90, or Bap31 by expression of a specific double-stranded oligomer(s). The results shown were observed 48 h following transfection of MCF-7 cells. The bar graph shows the means ± standard errors of the means (SEM) for protein expression of Hsp27 from three studies combined. +, P < 0.05 for control, Hsp90, or Bap31 siRNA versus Hsp27 siRNA(s). (Right) Localization of ERα at the plasma membranes (PMs) of MCF-7 cells. Cells were transfected with various siRNAs for 48 h and recovered, and then ERα was detected by immunofluorescence microscopy, as described in Materials and Methods. Nonspecific IgG antibody revealed no ER staining (data not shown). Images are representative of 200 cells surveyed per condition, and arrows point to membrane localization of ERα. The bar on the photomicrograph is 25 μm in length. (C) Immunoblots of ERα localization at the nucleus (Nuc) or PM (Mem) of MCF-7 cells treated as for panel B. Nuclear and membrane fractions from cell lysates were isolated under each condition, immunoprecipitation of ERα was carried out, and the precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to nylon that was incubated with specific antibody to ERα. Additional blot analyses for 5′ nucleotidase (5′NT) (plasma membrane protein), transportin and nuclear transfer factor 2 (NTF2) (nuclear proteins), or β-COP (endosomal/Golgi marker protein) were performed with the nuclear and plasma membrane cell fractions to show purity. The bar graph represents mean ± SEM densitometry values for PM blots from three experiments combined. +, P < 0.05 for control, Hsp90, or Bap31 siRNA(s) versus Hsp27 siRNA.

TABLE 1.

Analysis of tandem mass spectrometry results from peptides derived from digests of the specific affinity column gel banda

| Swiss-Prot accession no. | Description | Peptide count | Scan count | % coverage | Molecular wt | p1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P04792 | Heat shock protein beta-1; heat shock 27-kDa protein; stress-responsive protein 27; estrogen-regulated 27-kDa protein; 28-kDa heat shock protein | 42 | 3,548 | 91.18 | 22,769 | 6.03 |

| P51572 | B-cell receptor-associated protein 31; BCR-associated protein Bap31; p28 Bap31; protein CDM; 6C6-AG tumor-associated antigen | 16 | 426 | 32.24 | 27,975 | 8.15 |

Data analysis was done with the Sequest search engine. Several peptides were additionally derived (not shown) from low-abundance proteins and were not further investigated. The protein probability for each protein was 1.

We then asked whether Hsp27 or Bap31 facilitates trafficking of ERα to the membrane and rapid signal transduction. To investigate the importance and roles of these two proteins, we used an RNA interference (RNAi) approach with MCF-7 cells. A specific siRNA for each of the proteins Hsp27, Bap31, and Hsp90 (Hsp specificity control) knocked down only the intended endogenous target protein (Fig. 1B, left). Hsp90 was included because this protein interacts with ERα (31) and plays important chaperone and other roles in a variety of cancers (45).

We then assessed the subcellular localization of ERα in MCF-7 cells by immunofluorescence microscopy of several hundred cells per condition. Endogenous ERα localization at the PM was seen in 92% of the control siRNA-treated cells. In most of the remaining 8% of cells, the membranes were folded under the main body, preventing adequate visualization. Similarly, we clearly saw membrane ERα expression in 89 to 93% of cells expressing siRNAs to Bap31 or Hsp90 (Fig. 1B, right). In contrast, we detected PM ERα in only ∼11% of Hsp27 knockdown cells, consistent with a significant but incomplete knockdown. Importantly, nuclear ERα expression was seen in all cells and was unaffected by any siRNA.

There is a sensitivity limitation of fluorescence microscopy since small numbers of membrane-localized ERα may not be visualized. To further support these findings, we performed immunoblot analyses of ERα in PM and nuclear fractions of MCF-7 cells that showed no appreciable contamination from other cell fractions (Fig. 1C). The expression levels of ERα protein at the PM were consistent across all experimental conditions, except these levels were substantially reduced by Hsp27 knockdown. In contrast, nuclear ERα expression levels were similar in all samples. Collectively, these results indicate that Hsp27 facilitates the trafficking of endogenous ERα to the PM.

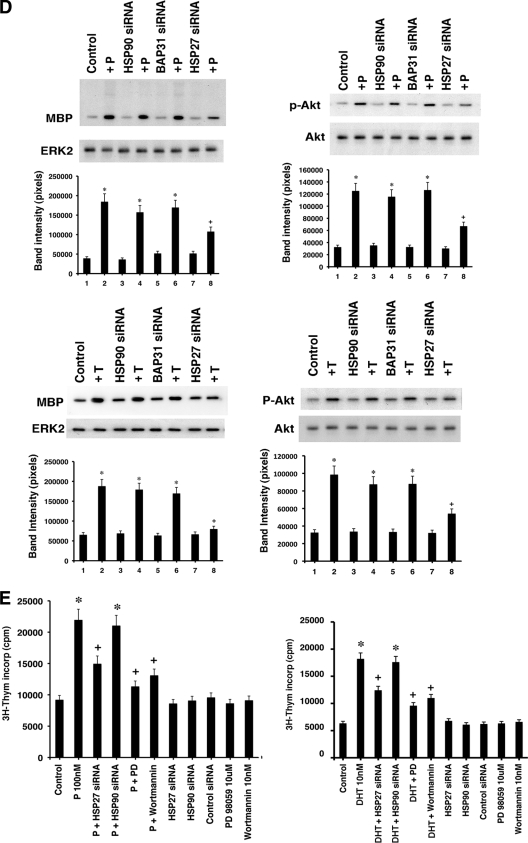

Functional effects of Hsp27 on ER signaling.

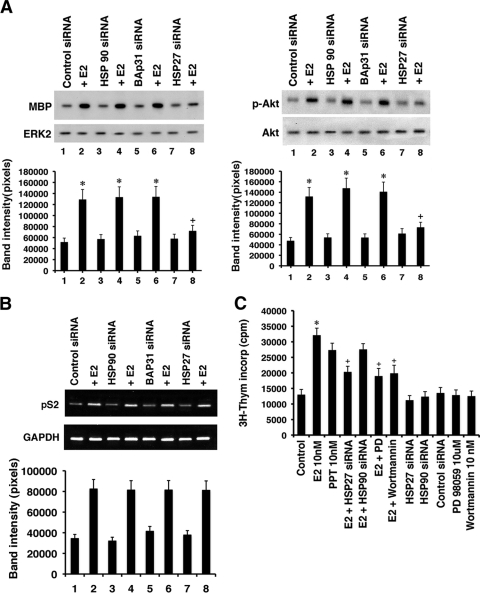

In order to assess the functional impact for membrane ERα, rapid transductions of ERK and PI3K activities in response to E2 were determined, as described previously (32). Kinase activation arises from membrane SR pools (13), and we found that only Hsp27 knockdown significantly prevented the activation of these signal molecules by physiological E2 concentrations (Fig. 2 A). We also determined whether Hsp27 affected the transactivation of an estrogen response element-dependent gene, pS2. E2 signaling from membrane ER would not be expected to alter pS2 gene expression since trans activation of this gene results from binding of nuclear ERα to its response element (31). Accordingly, Hsp27 siRNA did not affect the ability of E2 to stimulate pS2 gene expression (Fig. 2B). This is consistent with a lack of effect of Hsp27 for the trafficking of ERα to the nucleus (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 2.

E2-stimulated rapid signaling to DNA synthesis is inhibited by Hsp27 knockdown. (A) MCF-7 cells were transfected with various siRNAs, recovered, and then incubated with 10 nM E2 for 5 or 15 min. Cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation of ERK activity, as determined by an in vitro assay, against myelin basic protein (MBP) substrate or for phosphorylation of AKT at Ser473 (PI3K-induced site), as determined by immunoblot analysis. The bar graph represents mean ± SEM determinations from 3 experiments combined. *, P < 0.05 by ANOVA plus Schefe's test for control versus E2; +, P < 0.05 for E2 plus control, Hsp90, or Bap31 siRNA versus E2 plus Hsp27 siRNA. (B) pS2 gene expression is stimulated by E2. MCF-7 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and pS2 expression in response to 10nME2 was determined by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) expression serves as a control. The bar graph is based on a study representative of two experiments. (C) Thymidine incorporation stimulated by E2 in MCF-7 cells was inhibited by Hsp27 knockdown or MEK or PI3K inhibition. The bar graph represents mean ± SEM determinations from 3 experiments combined, with triplicate replicates in each study. *, P < 0.05 by ANOVA plus Schefe's test for control versus E2; +, P < 0.05 for E2 versus E2 plus Hsp27 siRNA, PD98059 (MEK inhibitor), or wortmannin (PI3K inhibitor).

Ligand engagement of sex SRs at the membrane results in signaling to cell biology (14). We previously showed that after transfection of membrane or nucleus-targeted estrogen receptors, cell proliferation occurs in response to E2 acting at either membrane or nuclear receptors (37). Here, we found that incorporation of thymidine into MCF-7 cells as induced by E2 was reduced to ∼50% specifically from Hsp27 knockdown (Fig. 2C). Comparable loss of E2-induced DNA synthesis also resulted from the inhibition of MEK by PD98059 or that of PI3K by wortmannin, supporting the concept that these specific kinase pathways importantly contribute to E2/membrane ERα-induced breast cancer cell cycle progression and proliferation (27, 37, 39). Thus, Hsp27 facilitates ERα trafficking to the PM, resulting in E2-stimulated signaling by the endogenous receptor pool to growth-promoting kinases in breast cancer cells.

Hsp27 promotes palmitoylation of sex steroid receptors.

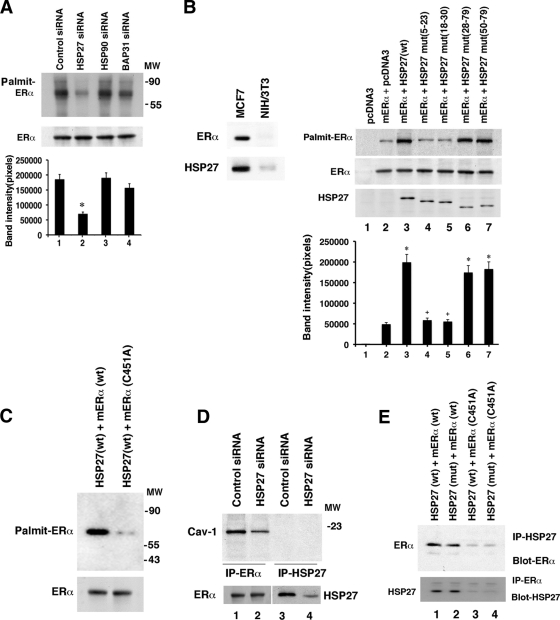

How does Hsp27 promote sex steroid receptor trafficking to the PM? One possibility is that Hsp27 facilitates SR palmitoylation. We first determined that knockdown of only Hsp27 significantly diminished endogenous ERα palmitoylation in breast cancer cells (Fig. 3 A). The studies were done in the absence of E2 because we previously showed that the sex steroid does not significantly facilitate palmitoylation or membrane localization (33, 37).

FIG. 3.

Hsp27 is required for ER palmitoylation. (A) MCF-7 cells were transfected with control siRNA or siRNA to Hsp27, Hsp90, or BAP31, and endogenous ERα palmitoylation was determined as described in Materials and Methods. The total SR abundance, as shown by the immunoblot, served as a loading control, and the study was repeated. Molecular weight markers were run in a parallel well. The bar graph represents the means ± SEM of results from three experiments combined. *, P < 0.05 for control versus Hsp27 siRNA. (B) (Left) Presence of ERα and Hsp27 in NIH 3T3 and MCF-7 cells. (Right) Expression of wild-type (lane 3) but not oligomerization mutant (lanes 4 and 5) Hsp27 promotes ERα palmitoylation. NIH 3T3 cells were cotransfected with ERα and the WT or one of four Hsp27 deletion mutants, the cells were recovered, and ERα palmitoylation was determined. Total ERα and Hsp27 isoform proteins are shown as loading controls, with the latter resolved over 5 h on a 10% gel. The bar graph represents 3 experiments combined, each with the means ± SEM compared by ANOVA plus Schefe's test. *, P < 0.05 for expression of control (lane 1 or 2) versus that of Hsp27 (lane 3) or Hsp27 mutants that retain oligomerization (lanes 6 and 7). +, P < 0.05 for WT Hsp27 (lane 2) versus oligomerization-deficient Hsp27 mutants (lanes 4 and 5). (C) C451A mutant ERα is not palmitoylated by Hsp27. WT or mutant ERα was expressed with WT Hsp27 in NIH 3T3 cells, and palmitoylation studies were carried out. (D) Caveolin-1 associates with ERα but not Hsp27. MCF-7 cells were lysed, and lysate was immunoprecipitated with either ERα antibody (lanes 1 and 2) or Hsp27 antibody (lanes 3 and 4), followed by immunoblot analysis for caveolin-1. Under some conditions, the cells were first transfected with control or Hsp27 siRNA. ERα and Hsp27 blots are shown as controls. (E) Structural requirements for ERα/Hsp27 interaction and function. Either WT or oligomerization mutant Hsp27 was transfected into NIH 3T3 cells with WT or C451A mutant ERα. Protein associations were determined by immunoprecipitation (IP) of Hsp27, followed by immunoblot analysis for ERα. IP-IB was also carried out in the reverse order, while IP with nonspecific IgG yielded no proteins (data not shown). The study was repeated.

We also cotransfected ERα and Hsp27 into NIH 3T3 cells. The native NIH 3T3 cells have undetectable endogenous ERα and very low levels of Hsp27 proteins, in contrast to MCF-7 cells (Fig. 3B, left). We found that in the absence of Hsp27 transfection/expression, scant palmitoylation of expressed ERα was seen (Fig. 3B, right, lanes 1 and 2). Coexpression of wild-type (WT) Hsp27 resulted in significant palmitoylation of the sex steroid receptor (lane 3). We also expressed WT or mutant C451A ERα in the NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. 3C). Cysteine 451 is the site of palmitoylation that is required to drive mouse ERα to the plasma membrane (1, 33). Only WT ERα, and not C451A ERα, was palmitoylated in the setting of WT Hsp27 expression, indicating that C451 is the site of palmitoylation that is promoted by this heat shock protein (Fig. 3C). One consideration is that Hsp27 might function as a palmitoyl acyltransferase (PAT) for ERα. However, there are 23 known mammalian PATs, and each contains the signature amino acid sequence DHHC (30). Hsp27 does not contain this sequence, making it highly unlikely that this protein is a PAT.

Membrane localization occurs in part because palmitoylation of ERα promotes the interaction of the SR with caveolin-1 protein, an association that importantly facilitates membrane trafficking (1, 37). We found that knockdown of Hsp27 resulted in significantly diminished ERα-caveolin-1 association without affecting ER abundance (Fig. 3D). In contrast, we found no physical association of Hsp27 and caveolin-1 under any condition.

Oligomerization of Hsp27 is often required for its activity (42). To determine whether oligomerization is necessary to promote ERα palmitoylation, we expressed the WT or 4 different mutant Hsp27 constructs in NIH 3T3 cells. Two of these constructs delete amino acids 5 to 23 or 18 to 30 and are known to abrogate oligomerization, while two other mutants feature the loss of amino acids 28 to 79 or 50 to 79, producing Hsp27 proteins that retain the ability to form oligomers (42). We determined that expressing oligomerization mutant Hsp27 proteins with ERα did not promote palmitoylation of the SR, in contrast to what was found for all other Hsp27 constructs (Fig. 3B).

These results raised the following questions. Does WT but not oligomer mutant Hsp27 physically interact with the palmitoylation motif of ERα? Does the interaction of ERα with Hsp27 correlate with promotion of the palmitoylation of the sex steroid receptor? To further understand these structural requirements that are important to these questions, we expressed WT or C451A ERα with WT or oligomer mutant Hsp27 in NIH 3T3 cells. Interestingly, either WT or oligomer mutant Hsp27 proteins were capable of binding to WT ERα (Fig. 3E, lanes 1 and 2). However, when the critical cysteine in the palmitoylation motif of ERα was mutated, neither form of Hsp27 bound SR. These results indicate that the ERα palmitoylation motif (and cysteine 451 specifically) is required for the Hsp27-ERα interaction. Furthermore, oligomerization of Hsp27 mediates the promotion of SR palmitoylation (Fig. 3B) but not the association of the heat shock protein with ERα. It must be noted that other proteins in the cell could be in complex with Hsp27 to facilitate binding to ERα that may therefore be indirect.

The ERα monomer is preferentially palmitoylated.

In the nucleus, SR dimerizes as a necessary state to modulate gene transcription. Additionally, membrane-localized ERα undergoes rapid dimerization in the presence of ligand, a structural change that is required to bind small G proteins and activate signal transduction (38). We speculated that the ERα monomer in the cytoplasm is more likely to undergo palmitoylation, perhaps facilitated by Hsp27. Indirectly supporting this idea, we reported that endogenous ERα at the membrane of MCF-7 cells is mainly a monomer in the absence of ligand (38). This suggests that the monomer may be palmitoylated and transported to the PM: we previously showed that ER trafficking is not facilitated by E2 (37).

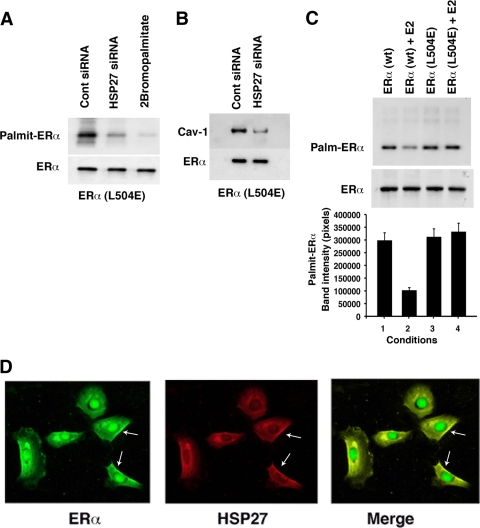

To support our hypothesis, we expressed a point mutant ERα that is unable to dimerize (38) in ER-null CHO cells. L504E ERα was cotransfected with control siRNA, resulting in strong palmitoylation of the SR. Palmitoylation of the monomer was facilitated by the endogenous Hsp27 since knockdown of the heat shock protein prevented ER palmitoylation (Fig. 4 A). As a control, 2-bromopalmitate, a soluble inhibitor of palmitoylation (11), also prevented acylation of the ERα monomer. Additionally, strong association of the monomeric ERα (dimer mutant) with caveolin-1 was seen but was inhibited by Hsp27 knockdown (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

The ERα monomer is palmitoylated. (A) Hsp27 facilitates the palmitoylation of the ERα monomer. A mutant ERα (L504E) was expressed in ER-null CHO cells, and after overnight recovery, the cells were labeled with [3H]palmitate and palmitoylation studies were carried out. Under some conditions, siRNAs (control or Hsp27) were transfected into the cells at the same time as L504E ERα while other cells were exposed to the palmitoylation inhibitor, 2-bromopalmitate (10 μM). (B) Monomeric ERα associates with caveolin-1. L504E ERα was expressed in ER-null CHO cells, with or without siRNA to Hsp27. After recovery, ERα was immunoprecipitated, followed by immunoblot analysis for caveolin-1. The ERα immunoblot serves as a loading control. (C) Monomeric ERα is the predominant form palmitoylated. CHO cells were transfected to express WT or L504E ERα, and the cells were recovered in charcoal-stripped serum overnight and then incubated in the absence or presence of E2 for 1 h. Palmitoylation was then carried out. The bar graph is based on 2 experiments. (D) Immunofluorescence microscopy of endogenous ERα expression (left), HSP27 expression (middle), and the overlap merge (right) in MCF-7 cells. Arrows point to membrane localization of the two proteins, and the study was repeated.

To determine if monomeric ERα is preferentially palmitoylated compared to the ERα dimer, we expressed WT and L504E ERα in CHO cells. In the absence of E2, WT ERα exists primarily as a monomer and is induced to dimerize by E2. However, ∼10 to 15% of ERα remains monomeric in the presence of ligand (38). We found that WT ERα is palmitoylated to a much greater extent in the absence than in the presence of E2 (Fig. 4C). The decreased but present palmitoylation of WT receptor in the presence of E2 probably reflects the small amount of monomeric ERα that remains upon exposure of the cells to ligand, as mentioned. L504E mutant ERα was strongly palmitoylated, unaffected by E2 since this receptor protein cannot undergo dimerization.

We previously determined that palmitoylation of ERα most likely occurs in the cytoplasm (33). Therefore, we determined whether Hsp27 and ERα colocalize in this region of the cell. Using immunofluorescence microscopy, we found extensive overlap of endogenous Hsp27 and ERα in the cytoplasm of MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4D). Importantly, Hsp27 was not found in the nucleus, despite the abundant presence of ERα, consistent with our results indicating that Hsp27 has no role in the nuclear transport of the SR (Fig. 1B and C). We did note colocalization of both Hsp27 and ERα at the plasma membrane, indicating that Hsp27 either is cotransported with ERα or reassociates with the SR at that site. Overall, these results indicate that oligomerized (WT) Hsp27 binds monomeric ERα at the palmitoylation motif within the E domain. This interaction promotes preferential palmitoylation of monomeric SR, facilitating the association of ER and caveolin-1. As a result, ERα traffics to the PM, the SR rapidly induced to undergo dimerization and productive signaling upon estrogen binding (38). A model of ERα trafficking to the PM is shown in Fig. 5.

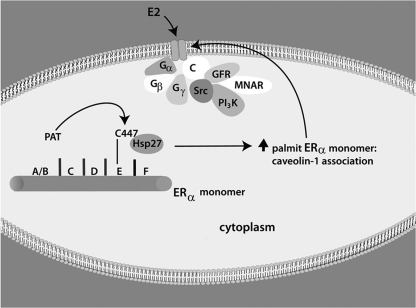

FIG. 5.

Model of ERα trafficking to the plasma membrane. Human ERα is palmitoylated by an unknown palmitoyl acyltransferase(s) (PAT) at cysteine 447 in the E domain (ligand binding domain), presumably after Hsp27 binds to the palmitoylation site. Hsp27 promotes palmitoylation of the ERα monomer, perhaps through alteration of the structure of the monomer to allow subsequent access by the putative PAT(s) to the palmitoylation motif. Palmitoylation promotes a strong protein-protein interaction of monomeric ERα with caveolin-1, an interaction that is required for subsequent trafficking of monomeric ERα to PM caveolae (C) (1, 34). At the membrane, E2 induces dimerization of ERα, required for the productive interaction of the sex steroid receptor with signaling molecules that localize to caveolae and are activated by E2/ER (35). MNAR, modulator of nongenomic action of the estrogen receptor; GFR, growth factor receptor.

Hsp27 and trafficking of PR and AR.

The results with ERα inspired the question as to whether Hsp27 also facilitates palmitoylation and trafficking of other sex SRs. We previously showed that endogenous PRB exists at the PMs of MCF-7 cells and that endogenous AR is detected at the PMs of prostate cancer cells (33). We therefore introduced control, Hsp27 or Hsp90, or Bap31 siRNAs into MCF-7 and LNCaP cells and found that only Hsp27 knockdown prevented PM localization of PR and AR (Fig. 6A). We also performed immunoblot analyses of PR and AR expression in cell fractions and found that Hsp27 siRNA strongly decreased PR or AR expression only at the PM (Fig. 6B). Similarly, decreasing Hsp27 diminished AR and PR palmitoylation (Fig. 6C). Thus, Hsp27 facilitates the palmitoylation and PM translocation of the three classes of sex steroid receptors.

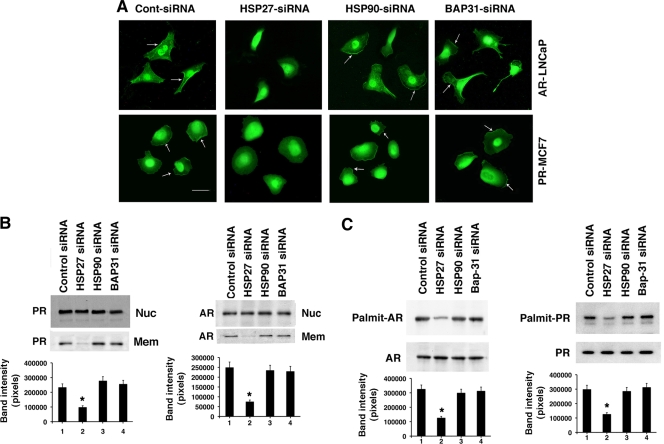

FIG. 6.

Hsp27 and androgen and progesterone receptors at the membrane. (A) Hsp27 facilitates androgen receptor (AR) and progesterone receptor (PR) trafficking to the membrane. LNCaP prostate cancer cells (upper panels) or MCF7 cells (lower panels) were transfected to individually express the indicated siRNAs, and the cells recovered overnight. Cell localization of endogenous AR (upper panels) or PR (lower panels) was determined by immunofluorescence microscopy. Nonspecific IgG second antibody revealed no PR or AR staining (data not shown). (B) MCF-7 cells (left) or LNCaP cells (right) were treated as for panel A, and then PR or AR was detected by immunoblot analyses of nuclear (Nuc) and PM (Mem) fractions after receptor protein immunoprecipitation, followed by SDS-PAGE separation and transfer of proteins. The bar graph represents three experiments combined. *, P < 0.05 by ANOVA plus Schefe's test for control siRNA versus HSP27 siRNA in the membrane fraction. (C) Palmitoylation of endogenous AR and PR depends upon Hsp27 presence. LNCaP and MCF-7 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and palmitoylation of the sex steroid receptors was determined. The bar graph is based on 3 combined experiments. *, P < 0.05 for control siRNA versus HSP27 siRNA. (D) Hsp27 is required for ERK or PI3K activation by P in MCF-7 cells or by T in LNCaP cells. Signal transduction experiments were carried out as described for Fig. 1C. The bar graph represents mean ± SEM determinations from 3 experiments combined. *, P < 0.05 by ANOVA plus Schefe's test for control versus P or T; +, P < 0.05 for P or T plus control, Hsp90, or Bap31 siRNA versus P or T plus Hsp27 siRNA. (E) Thymidine incorporation stimulated by progesterone (P) in MCF-7 cells or androgen (dihydrotestosterone [DHT]) in LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Cells were transfected with siRNAs as indicated and recovered, and then thymidine incorporation was carried out over 24 h in response to sex steroids with or without ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitor (PD98059) or PI3K inhibitor (wortmannin). The bar graph shows mean ± SEM determinations from 3 experiments combined, with triplicate replicates in each study. *, P < 0.05 by ANOVA plus Schefe's test for control versus P or DHT; +, P < 0.05 for sex steroid versus the same plus Hsp27 siRNA, PD98059, or wortmannin.

We then determined whether loss of Hsp27 modulated PR and AR signaling in breast and prostate cancer cells, respectively. Knockdown of Hsp27 significantly prevented progesterone (P)-induced ERK and PI3K activity in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6D, top), while knockdown of Hsp90 or Bap31 had no effect. Similarly, testosterone (T)-induced rapid signaling in LNCaP cells was specifically prevented by the loss of Hsp27 (Fig. 6D, lower). Sex steroid-induced signaling was not completely prevented under these conditions, commensurate with the incomplete knockdown of endogenous Hsp27.

We also examined whether PR and AR signaling from the PM modulated DNA synthesis, reflected as thymidine incorporation (Fig. 6E). In MCF-7 cells, P induced more than a 2-fold increase in DNA synthesis, inhibited approximately 60% only by Hsp27 knockdown. P-stimulated thymidine incorporation was also significantly blocked by MEK or PI3K inhibitors, supporting the important role of membrane PR rapid signaling for DNA synthesis, reflecting cell cycle progression in breast cancer. Similarly, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) stimulated thymidine incorporation in LNCaP prostate cancer cells, suggesting that this pool of AR contributes to cell cycle progression. Due to the more prolonged nature of these experiments (24 h) than of rapid signal transduction (5 to 15 min), we used an androgen, DHT, that does not undergo aromatization to estrogen. Thus, all sex steroids demonstrated significant although partial dependence on membrane receptor functions to stimulate DNA synthesis. It is also likely that the nuclear receptor pool importantly contributes to this cellular action of sex steroids.

DISCUSSION

Once sex SRs traffic to plasma membrane caveola rafts, liganded receptors engage and activate Gα and Gβγ subunits. G protein activation initiates a variety of subsequent signals that promote cell proliferation, migration, and other biological functions (14, 25). The localization of sex SRs at the PM requires the attachment of palmitic acid to an internal cysteine, reversibly S palmitoylated via thioester linkage that is promoted by an unknown palmitoyl acyltransferase enzyme(s) (33). Palmitoylation occurs at a cysteine within a conserved 9-amino-acid motif in the E domains of ERα, ERβ, PR, and AR (33). For ERα, palmitoylation promotes the interaction of this SR with the transporter protein, caveolin-1, an association that is required for membrane localization of ERα (1, 37). Through isolating proteins that bind the palmitoylation motif of ERα, we here identify Hsp27 as a stress protein/chaperone that broadly promotes sex SR palmitoylation, a novel function of the heat shock protein. These results provide (i) an important new focus for understanding the dynamic trafficking of all sex SR and (ii) a potential target for selectively interrupting PM localization of sex SRs and preventing rapid signaling by steroid hormones.

Endogenous membrane ERα in breast cancer cells exists as a monomer in the absence of ligand (38). This suggests that palmitoylation of monomeric ERα is an important event for membrane trafficking of the SR. Since the palmitoylation motif is deep within the structure of ERα, the receptor dimer is probably unable to provide access to the PAT protein. An unexplained observation is that E2 promotes dimerization and hence functional activation of ERα but does not significantly augment membrane localization (37). This is now explained here in that palmitoylation preferentially occurs on the ER monomer and is not enhanced by sex steroid. Indeed, E2-induced dimerization may be a rate-limiting factor that prevents more than ∼5% of receptors from undergoing acylation and trafficking to the PM (32). Subsequent binding of ligand to membrane-localized ERα induces dimerization of the receptor, required for activation of discrete Gα subunits, a very rapid signal generated upon E2 addition (35). An interesting recent observation is that E2 induces rapid depalmitoylation of ERα (11). This leads to dissociation of ER from caveolin-1. However, is not clear what impact depalmitoylation has for broad-signal transduction or relocalization of ER away from the plasma membrane.

We report that Hsp27 must be oligomerized to promote ERα palmitoylation and membrane localization since Hsp27 oligomer mutant proteins fail to carry out these actions. This is consistent in that unrelated actions of this small heat shock protein in cancer cells require oligomerization (26). Specifically, we find that oligomerized Hsp27 promotes palmitoylation of the ERα monomer, facilitating the interaction of this form of the SR with caveolin-1. We speculate that sequential binding of Hsp27 and then the ER PAT occurs at the palmitoylation motif sequence in ERα. Oligomerized Hsp27 binding might alter the monomeric conformation, opening up the structure to allow a productive interaction of ERα with its PAT, and this would also be applicable in principle to the other sex SRs. Since Hsp27 lacks the DHHC sequence characteristic of mammalian PATs (10), the heat shock protein probably facilitates palmitoylation rather than directly catalyzing this protein modification. Isolation of the SR-specific PAT(s) and X-ray structural studies of ER will be required to fully understand how Hsp27 facilitates SR acylation.

Hsp27 is known to interact with ER and has been reported to modify some transcriptional actions of the nuclear sex SR (4). These studies exclusively utilized transfection/overexpression of exogenous Hsp27 in cells. We find that endogenous Hsp27 does not interfere with estrogen response element-mediated transcription by nuclear ERα or affect the nuclear localization of the SR. As a general principal, Hsp27 can affect signal transduction, stimulating PI3K-dependent AKT activity and Bax inactivation through undetermined mechanisms, leading to cell survival during stress (17). PI3K and AKT are important to the ability of E2 to promote the survival and growth of breast cancer cells (9, 38), and our linking Hsp27 to membrane trafficking of ERα and signaling defines a potentially important pathway for SR and Hsp27 functions. This may underlie the known overlapping functions of estrogen and Hsp27 to regulate cell growth, survival, and migration (22).

It is the membrane and not the nuclear ERα that is required and sufficient for rapid signal transduction in normal organs (34) or breast cancer cells (37). Expanding the importance of this concept, we report that knockdown of Hsp27 prevents rapid signal transduction and reduces E2-stimulated DNA synthesis in breast cancer by ∼50%. Although knockdown of the chaperone protein was incomplete, the partial reversal of this E2 action is consistent with evidence that both membrane- and nucleus-localized pools of ERα contribute to cell proliferation (37). In human breast cancer, Hsp27 inhibits doxorubicin-induced apoptosis (15), promotes resistance to induction chemotherapy (43), and reduces susceptibility to the antitumor effects of trastuzumab (Herceptin) (19). It is reasonable to postulate that several of these actions may be linked to Hsp27's promotion of the localization and functions of membrane ERα in this malignancy, as Hsp27 and E2/ER prevent chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity (15, 43). Hsp27 is associated with decreased survival rates among patients with node-negative breast cancer, which is often ER positive (41), but does not correlate with the clinical course of metastatic breast cancer (19). The latter often reflects the overexpression of the ErbB2 membrane tyrosine kinase receptor that amplifies PI3K signaling in ER-negative tumors (5).

The effects of Hsp27 were specific, as Hsp90, an important chaperone protein for the stress response and cancer (6), had no effect on ERα trafficking. Similarly, Bap31 had no effect on ERα palmitoylation or membrane localization. Hsp90 has been reported to chaperone nucleus-bound ERα but repress its trans-activating activity in the absence of ligand (44). We found little effect of knocking down this protein on nuclear localization or the positive trans-activating function of E2 at this ER pool. It is unknown how much Hsp90 protein is required for chaperoning of nuclear ERα, and perhaps the residual protein remaining after siRNA transfection may suffice for this purpose.

Hsp27 also promoted the palmitoylation and localization of endogenous PR at the membranes of breast cancer cells and of AR at the membranes of prostate cancer cells. Knockdown of this heat shock protein prevented rapid signaling to DNA synthesis. These results suggest that similar to ER, Hsp27 could modulate the growth and survival signaling by PR and AR in hormone receptor-responsive cancers. Membrane PR (3, 40) and AR (12, 29) are well established to mediate rapid signaling through ERK, Src kinase, and PI3K to proliferation and other aspects of cell biology in both cancer and nontransformed cells. By selectively limiting PR and AR trafficking to the membrane, we can further investigate cellular actions of sex steroids that originate from rapid signal transduction.

In addition to Hsp27 modulating ER function, E2 signaling from membrane ER through p38β mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase to MAP kinase-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAPK2) causes the phosphorylation of Hsp27 (36). Phosphorylation of Hsp27 by MAPKAPK2 is essential to the ability of E2 to preserve endothelial cell (EC) morphology and survival after stress and to stimulate EC migration and primitive blood vessel tube formation (36). Thus, the bidirectional interplay of Hsp27 and ERα ensures the ability of E2 to modulate cell biology. We believe that this interaction not only is relevant to cellular stress responses and tumor biology but also may play important roles in membrane sex SR functions in bone and cardiovascular biology (23, 28). Selectively inactivating one receptor pool (as we did here) while maintaining signaling from the other cellular SR pools represents an important tool for dissecting specific roles. This approach could justify more-precise intervention strategies for disease states using membrane-specific steroid receptor agonists and antagonists (16).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Research Service of the Department of Veteran's Affairs and NIH CA-10036 to E.R.L.

No conflicts were reported by the authors who approved the submitted work.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acconcia, F., P. Ascenzi, A. Bocedi, E. Spisni, V. Tomasi, A. Trentalance, P. Visca, and M. Marino. 2005. Palmitoylation-dependent estrogen receptor alpha membrane localization: regulation by 17beta-estradiol. Mol. Biol. Cell 16:231-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beato, M., and J. Klug. 2000. Steroid receptors: an update. Hum. Reprod. Update 6:225-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonyaratanakornkit, V., E. McGowan, L. Sherman, M. A. Mancini, B. J. Cheskis, and D. P. Edwards. 2007. The role of extranuclear signaling actions of progesterone receptor in mediating progesterone regulation of gene expression and the cell cycle. Mol. Endocrinol. 21:359-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, H., M. Hewison, and J. S. Adams. 2008. Control of estradiol-directed gene transactivation by an intracellular estrogen-binding protein and an estrogen response element-binding protein. Mol. Endocrinol. 22:559-569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciocca, D. R., S. Green, R. M. Elledge, G. M. Clark, R. Pugh, P. Ravdin, D. Lew, S. Martino, and C. K. Osborne. 1998. Heat shock proteins hsp27 and hsp70: lack of correlation with response to tamoxifen and clinical course of disease in estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer (a Southwest Oncology Group Study). Clin. Cancer Res. 4:1263-1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demonty, G., G. Bernard-Marty, F. Puglisi, I. Mancini, and N. Piccart. 2007. Progress and new standards of care in the management of HER-2 positive breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 43:497-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.el-Zein, G., D. Boujard, D. H. Garnier, and J. Joly. 1988. The dynamics of the steroidogenic response of perifused Xenopus ovarian explants to gonadotropins. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 71:132-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fan, P., J. Wang, R. J. Santen, and W. Yue. 2007. Long-term treatment with tamoxifen facilitates translocation of estrogen receptor alpha out of the nucleus and enhances its interaction with EGFR in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 67:1352-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernando, R. I., and J. Wimalasena. 2004. Estradiol abrogates apoptosis in breast cancer cells through inactivation of BAD: Ras-dependent nongenomic pathways requiring signaling through ERK and Akt. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:3266-3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukata, Y., T. Iwanaga, and M. Fukata. 2006. Systematic screening for palmitoyl transferase activity of the DHHC protein family in mammalian cells. Methods 40:177-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galluzzo, P., P. Ascenzi, P. Bulzomi, and M. Marino. 2008. The nutritional flavanone naringenin triggers antiestrogenic effects by regulating estrogen receptor alpha-palmitoylation. Endocrinology 149:2567-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haas, D., S. N. White, L. B. Lutz, M. Rasar, and S. R. Hammes. 2005. The modulator of nongenomic actions of the estrogen receptor (MNAR) regulates transcription-independent androgen receptor-mediated signaling: evidence that MNAR participates in G protein-regulated meiosis in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol. Endocrinol. 19:2035-2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagve, T. A., and B. O. Christophersen. 1987. In vitro effects of alpha-bromopalmitate on metabolism of essential fatty acids studied in isolated rat hepatocytes: sex differences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 917:333-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammes, S. R., and E. R. Levin. 2007. Extra-nuclear steroid receptors: nature and function. Endocr. Rev. 28:726-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen, R. K., I. Parra, P. Lemieux, S. Oesterreich, S. G. Hilsenbeck, and S. A. Fuqua. 1999. Hsp27 overexpression inhibits doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 56:187-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrington, W. R., S. H. Kim, C. C. Funk, Z. Madak-Erdogan, R. Schiff, J. A. Katzenellenbogen, and B. S. Katzenellenbogen. 2006. Estrogen dendrimer conjugates that preferentially activate extranuclear, nongenomic versus genomic pathways of estrogen action. Mol. Endocrinol. 20:491-502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Havasi, A., Z. Li, Z. Wang, J. L. Martin, B. Venugopal, K. Ruchalsi, J. H. Schwartz, and S. C. Borkan. 2008. Hsp27 inhibits Bax activation and apoptosis via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 283:12305-12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huhtakangas, J. A., C. J. Olivera, J. E. Bishop, L. P. Zanello, and A. W. Norman. 2004. The vitamin D receptor is present in caveolae-enriched plasma membranes and binds 1 alpha,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Endocrinol. 18:2660-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang, S. H., K. W. Kang, K. H. Kim, B. Kwon, S. K. Kim, H. Y. Lee, S. Y. Kong, E. S. Lee, S. G. Jang, and B. C. Yoo. 2008. Upregulated HSP27 in human breast cancer cells reduces Herceptin susceptibility by increasing Her2 protein stability. BMC Cancer 8:286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim, H. P., J. Y. Lee, J. K. Jeong, S. W. Bae, H. K. Lee, and I. Jo. 1999. Nongenomic stimulation of nitric oxide release by estrogen is mediated by estrogen receptor alpha localized in caveolae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 263:257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim, J., and E. R. Levin. 2006. Estrogen signaling in the cardiovascular system. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 4:e013-e017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kostenko, S., and U. Moens. 2009. Heat shock protein 27 phosphorylation: kinases, phosphatases, functions and pathology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66:3259-3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kousteni, S., J. R. Chen, T. Bellido, L. Han, A. A. Ali, C. A. O'Brien, L. Plotkin, Q. Fu, A. T. Mancino, Y. Wen, A. M. Vertino, C. C. Powers, S. A. Stewart, R. Ebert, A. M. Parfitt, R. S. Weinstein, R. L. Jilka, and S. C. Manolagas. 2002. Reversal of bone loss in mice by nongenotropic signaling of sex steroids. Science 298:843-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar, R., R. A. Wang, A. Mazumdar, A. H. Talukder, M. Mandal, Z. Yang, R. Bagheri-Yarmand, A. Sahin, G. Hortobagyi, L. Adam, C. J. Barnes, and R. K. Vadlamudi. 2002. A naturally occurring MTA1 variant sequesters oestrogen receptor-alpha in the cytoplasm. Nature 418:654-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar, P., Q. Wu, K. L. Chambliss, I. S. Yuhanna, S. M. Mumby, C. Mineo, G. G. Tall, and P. W. Shaul. 2007. Direct interactions with Gαi and Gβγ mediate nongenomic signaling by estrogen receptor β. Mol. Endocrinol. 21:1370-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lelj-Garolla, B., and A. G. Mauk. 2006. Self-association and chaperone activity of Hsp27 are thermally activated. J. Biol. Chem. 281:8169-8174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levin, E. R., and R. J. Pietras. 2008. Estrogen receptors outside the nucleus in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 108:351-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mendelsohn, M. E., and R. H. Karas. 2005. Molecular and cellular basis of cardiovascular gender differences. Science 308:1583-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Migliaccio, A., G. Castoria, M. Di Domenico, A. de Falco, A. Bilancio, M. Lombardi, M. V. Barone, D. Ametrano, M. S. Zannini, C. Abbondanza, and F. Auricchio. 2000. Steroid-induced androgen receptor-oestradiol receptor beta-Src complex triggers prostate cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J. 19:5406-5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohno, Y., A. Kihara, T. Sano, and Y. Igarashi. 2006. Intracellular localization and tissue-specific distribution of human and yeast DHHC cysteine-rich domain-containing proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761:474-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oxelmark, E., R. Knoblauch, S. Arnal, L. F. Su, M. Schapira, and M. J. Garabedian. 2003. Genetic dissection of p23, an Hsp90 co-chaperone, reveals a distinct surface involved in estrogen receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 278:36547-36555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedram, A., M. Razandi, and E. R. Levin. 2006. Nature of functional estrogen receptors at the plasma membrane. Mol. Endocrinol. 20:1996-2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedram, A., M. Razandi, R. C. A. Sainson, J. K. Kim, C. C. Hughes, and E. R. Levin. 2007. A conserved mechanism for steroid receptor translocation to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 282:22278-22288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedram, A., M. Razandi, J. K. Kim, F. O'Mahony, E. Y. H. P. Lee, U. Luderer, and E. R. Levin. 2009. Developmental phenotype of a membrane only estrogen receptor α (MOER) mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 284:3488-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Razandi, M., A. Pedram, G. L. Greene, and E. R. Levin. 1999. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors derive from a single transcript: Studies of ERα and ERβ expressed in CHO cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 13:307-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Razandi, M., A. Pedram, and E. R. Levin. 2000. Estrogen signals to preservation of endothelial cell form and function. J. Biol. Chem. 275:38540-38546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Razandi, M., G. Alton, A. Pedram, S. Ghonshani, D. Webb, and E. R. Levin. 2003. Identification of a structural determinant for the membrane localization of ERα. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:1633-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Razandi, M., A. Pedram, I. Merchenthaler, G. L. Greene, and E. R. Levin. 2004. Plasma membrane estrogen receptors exist and function as dimers. Mol. Endocrinol. 18:2854-2865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razandi, M., A. Pedram, E. Rosen, and E. R. Levin. 2004. BRCA1 inhibits membrane estrogen and growth factor receptor signaling to cell proliferation in breast cancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24:5900-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skildum, A., E. Faivre, and C. A. Lange. 2005. Progesterone receptors induce cell cycle progression via activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol. Endocrinol. 19:327-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thanner, F., M. W. Sutterlin, M. Kapp, L. Rieger, A. K. Morr, P. Kristen, J. Dietl, A. M. Gassel, and T. Muller. 2005. Heat shock protein 27 is associated with decreased survival in node-negative breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 25:1649-1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thériault, J. R., H. Lambert, A. T. Chávez-Zobel, G. Charest, P. Lavigne, and J. Landry. 2004. Essential role of the NH2-terminal WD/EPF motif in the phosphorylation-activated protective function of mammalian Hsp27. J. Biol. Chem. 279:23463-23471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vargas-Roig, L. M., F. E. Gago, O. Tello, J. C. Aznar, and D. R. Ciocca. 1998. Heat shock protein expression and drug resistance in breast cancer patients treated with induction chemotherapy. Int. J. Cancer 79:468-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whitesell, L., and S. L. Lindquist. 2005. Hsp90 and the chaperoning of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5:761-772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Workman, P., F. Burrows, L. Neckers, and N. Rosen. 2007. Drugging the cancer chaperone HSP90: combinatorial therapeutic exploitation of oncogene addiction and tumor stress. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1113:202-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]