Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus nonstructural protein 2 (nsp2) contains a cysteine protease domain at its N terminus, which belongs to the ovarian tumor (OTU) protease family. In this study, we demonstrated that the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain antagonizes the type I interferon induction by interfering with the NF-κB signaling pathway. Further analysis revealed that the nsp2 OTU domain possesses ubiquitin-deconjugating activity. This domain has the ability to inhibit NF-κB activation by interfering with the polyubiquitination process of IκBα, which subsequently prevents IκBα degradation. To determine whether the nsp2 protein antagonist function can be ablated from the virus, we introduced point mutations into the OTU domain region by use of reverse genetics. The D458A, S462A, and D465A mutations targeting on a B-cell epitope in the OTU domain region generated the viable recombinant viruses, and the S462A and D465A mutants were attenuated for growth in cell culture. The OTU domain mutants were examined to determine whether mutations in the nsp2 OTU domain region altered virus ability to inhibit NF-κB activation. The result showed that certain mutations lethal to virus replication impaired the ability of nsp2 to inhibit NF-κB activation but that the viable recombinant viruses, vSD-S462A and vSD-D465A, were unable to inhibit NF-κB activation as effectively as the wild-type virus. This study represents a fundamental step in elucidating the role of nsp2 in PRRS pathogenesis and provides an important insight in future modified live-virus vaccine development.

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) continues to be the most economically significant disease of swine worldwide. Since its emergence in domestic swine in the late 1980s, PRRS has resulted in tremendous economic losses in the swine industry, with recent costs in the United States of at least $600 million annually (35). The etiologic agent PRRS virus (PRRSV) is a small enveloped virus containing a single positive-stranded RNA genome. It is classified in the order Nidovirales, family Arteriviridae, which includes equine arteritis virus (EAV), lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV), and simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) (47). Nucleotide sequence comparisons show that PRRSV can be divided into distinct European (type I) and North American (type II) genotypes, possessing only about 63% nucleotide identity at the genomic levels (1, 33, 42). PRRSV infection appears to elicit poor innate interferon and cytokine responses. Its effects result in a weak adaptive immune response, as demonstrated by prolonged viremia and slow development of virus-specific humoral and cell-mediated immune responses (28, 32, 44).

The type I interferon (IFN) system is a key component of the innate immune response against viral infection (18, 41, 45). Initially, the pathogen-associated molecular pattern in double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) is recognized by host cell receptors, such as Toll-like receptor, retinoic acid-inducible protein I (RIG-I), or the melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5) protein. The binding of viral dsRNA with receptors activates protein signaling cascades, which results in the activation of transcription factors, including interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), NF-κB, and ATF-2/c JUN. The coordinated activation of these transcription factors leads to the formation of transcriptionally competent enhanceosomes in the cell nucleus to induce the expression of type I interferons. NF-κB is one of the critical transcription factors, and its activation is tightly controlled by interaction with a family of inhibitory proteins (IκBs). NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells through binding to the inhibitory proteins of the IκB family, including IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBɛ. Cellular stimulation by the viral dsRNA (or other stimuli, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) triggers the activation of signal transduction pathways, and the IκB kinase alpha (IKKα), IKKβ, and IKKγ kinases phosphorylate IκB. Phosphorylated IκB is targeted for proteasomal degradation by K48-linked polyubiquitination (poly-Ub). Degradation of the IκB protein releases NF-κB dimers for its translocation to the nucleus, where they regulate transcription of type I interferons (26).

Many viruses encode proteins that inhibit or modulate several important signaling pathways that are involved in interferon production. The PRRSV genome contains nine open reading frames. Based on the studies of EAV, the ORF1a- and ORF1b-encoded nonstructural polyproteins, pp1a and pp1ab, are proteolytically processed into 14 nonstructural protein (nsp) products (nsp1α, nsp1β, and nsp2 to nsp12), including the recently identified internal processing products of nsp7 (nsp7α and nsp7β) (9, 11, 47, 49, 56, 57). nsp2 is the largest viral protein and was determined to be critical in the proteolytic process for viral replication. The N-terminal region of nsp2 contains a cysteine protease domain that possesses characteristics of both papain-like cysteine proteases and chymotrypsin-like serine proteases. This protease is responsible for nsp2/3 cleavage and functions as a cofactor with nsp4 serine protease to process the other cleavage products (47, 48, 60). The nsp2 protein is also implicated in the formation of double membrane vesicles, as well as acting as a membrane anchor for the assembly of multiprotein viral replication complexes (38). Besides its critical roles in viral replication, recent studies from our laboratory and others (5, 8, 23, 36) showed that PRRSV nsp2 elicits strong humoral antibody responses, which suggests that this protein is also involved in the modulation of the host immune response. Frias-Staheli et al. (15) reported that the cysteine protease domain of PRRSV nsp2 belongs to the ovarian tumor (OTU) protease superfamily. The biological significance of the OTU domain-containing protease was evidenced by the ability of this protease to inhibit the host innate immune response. In this study, we demonstrated that the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain inhibits NF-κB activation by interfering with the polyubiquitination process of IκBα and, subsequently, preventing the degradation of the IκBα protein. Site-directed mutagenesis identified specific amino acid residues in the OTU domain region that are important for viral replication, and these mutations dramatically impaired the ability of nsp2 to inhibit NF-κB activation. A certain level of improvement in NF-κB activation was observed for those mutations that generated viable recombinant viruses. This study provides an important insight into the role of nsp2 in PRRS pathogenesis and represents a fundamental step in future modified live-virus vaccine development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

HEK-293T cells were used for in vitro characterization of nsp2 protein. BHK-21 cells were used for initial transfection to recover the recombinant virus from in vitro-transcribed RNA. MARC-145 cells, a continuous cell line that is permissive to PRRSV, were used for recombinant virus rescue and subsequent experiments. These cells were cultured in modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and maintained at 37°C under 5% CO2 incubation conditions. Porcine alveolar macrophages were obtained by lung lavage of 6-week-old, PRRSV-naïve piglets by use of the method described previously (64).

Viruses.

The type I PRRSV isolate SD01-08 (GenBank accession number DQ489311) (14) and its OTU domain mutants were used to infect macrophage and MARC-145 cells. The Sendai virus (SeV) Cantell strain was grown in embryonated chicken eggs. Virus titer was determined by a hemagglutination assay using chicken red blood cells as described previously (62).

Antibody production.

The B-cell epitope PEDDWASDYDLAQA (ES2 epitope of SD01-08 virus) was synthesized as a synthetic peptide. Monoclonal antibody (MAb) SD36-19 was produced by immunizing BALB/c mice with the ES2 synthetic peptide. Polyclonal antibody against nsp2 (pAb-nsp2) was raised in New Zealand White rabbits by using nsp2 recombinant protein. The detailed methods were described in our previous publication (9).

Expression plasmids.

The portion or full-length nsp2 region of SD01-08 was reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) amplified from genomic RNA, and PCR products were cloned into a eukaryotic expression vector, pCAGGS (31), designated pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-1446), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-725), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-883), and pCAGGS-nsp2 (579-1446) (Fig. 1A). The pCAGGS-NS1 plasmid was constructed by RT-PCR amplification of the NS1 gene from influenza A/swine/Texas/4199-2/98 (TX/98, H3N2 subtype) (50) and subsequently cloned into the pCAGGS vector. The reporter plasmid expressing the firefly luciferase under the control of the IFN-β promoter (p125-Luc) was kindly provided by Takashi Fujita (63). The pNF-κB-Luc reporter plasmid expressing the firefly luciferase under the control of a promoter with the NF-κB responsive element was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The pRL-SV40 plasmid that expresses a Renilla luciferase under the control of a simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). pcDNA 3.1(+)-HA-Ub was provided by Domenico Tortorella (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY) (54). The plasmid expressing mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) was constructed as we described previously (9). The NF-κB p65 gene was purchased from Thermo Scientific Open Biosystems (GenBank accession number BC033522) and was subsequently cloned into the pEGFP-N1 vector with a stop codon at the C terminus of p65 gene, which expresses only p65 protein (no green fluorescent protein [GFP] expressed). The p4489 Flag-beta TrCP plasmid expressing FWD1/betaTrCP and the pCMV2-IKK2-WT plasmid expressing IKKβ were obtained from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). The IκBα gene was purchased from Thermo Scientific Open Biosystems (GenBank accession number NM020529) and was subsequently cloned into the pFLAG-myc-CMV vector (Sigma-Aldrich).

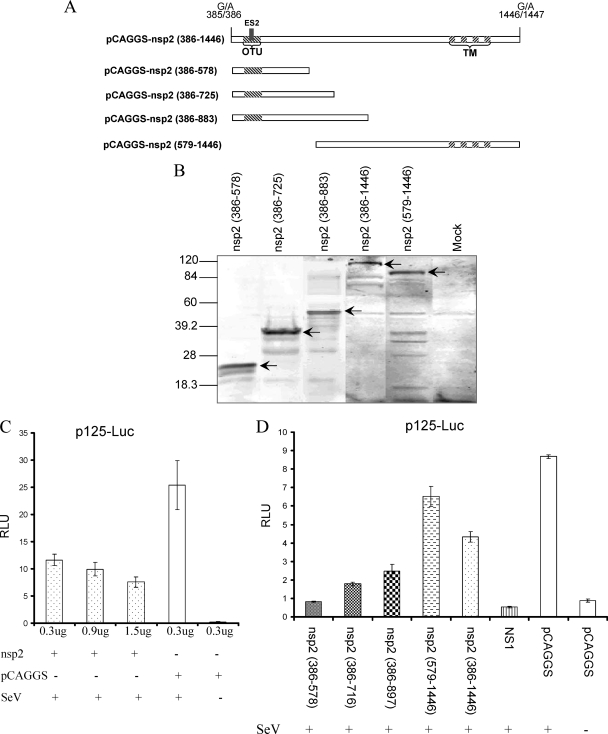

FIG. 1.

PRRSV nsp2 inhibits IFN-β synthesis. (A) Schematic diagram of the nsp2 N-terminal and C-terminal truncations. Each truncated region was cloned into the pCAGGS vector for in vitro expression in mammalian cells. The amino acid positions of each truncation in the SD01-08 pp1a are indicated. The nsp2 cysteine protease domain and transmembrane (TM) regions are indicated by hatched boxes. (B) Western blot analysis of the expression of truncated nsp2 proteins in 293T cells. Membrane was stained with rabbit anti-nsp2 polyclonal antibody. Arrows point to specific PRRSV nsp2 proteins. (C and D) nsp2 inhibits the expression of IFN promoter-driven luciferase expression. (C) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with an increased amount of plasmid expressing full-length nsp2, reporter plasmid p125-Luc, and pRL-SV40. (D) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing a portion of nsp2 or full-length nsp2, p125-Luc, and pRL-SV40. Cells were stimulated with Sendai virus 24 h posttransfection. The luciferase activity was measured at 12 to 16 h poststimulation.

Cell transfection.

To determine the effect of nsp2 on IFN-β production, HEK-293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected with 0.3 μg plasmid pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-1446), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-725), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-883), pCAGGS-nsp2 (579-1446), or empty pCAGGS vector, along with 0.3 μg of reporter plasmid p125-Luc or pNF-κB-Luc and 0.1 μg pSV40-RL. Transfection was performed using FuGENE HD transfection reagent in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were infected with Sendai virus at 5,000 hemagglutinin (HA) units/0.5 ml/well. Cells were harvested at 12 to 16 h poststimulation.

To determine the effect of nsp2 on NF-κB signaling, HEK-293T cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected with 0.3 μg of either pEGFP-N1-MAVS, pCMV2-IKK2-WT, or pEGFP-N1-p65 mixed with 0.3 μg of a plasmid expressing the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain, proteinase active-site mutant pCAGGS-C429A or pCAGGS-H498A, or empty pCAGGS plasmid and 0.3 μg pNF-κB-Luc and 0.1 μg pSV40-RL. Cells were stimulated by 20 ng/ml TNF-α and harvested at 6 h poststimulation.

To determine the effect of OTU domain mutation on the ability of the virus to inhibit NF-κB activation, MARC-145 cells were seeded into 24-well plates 2 days prior to infection. Cells were infected by mutant viruses vSD-nsp2-D458A, vSD-nsp2-S462A, and vSD-nsp2-D465A and parental virus vSD01-08 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.0. Sendai virus was used to infect MARC-145 cells as a control. Two hours after infection, 0.3 μg plasmid pNF-κB-Luc and 0.1 μg pSV40-RL were transfected into the infected cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were lysed using lysis buffer for the luciferase reporter assay and Western blot analysis.

To determine the effect of nsp2 on the expression of host ubiquitinated proteins, 293T cells were transfected with 0.6 μg pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-1446), pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578), or pCAGGS empty plasmid and 0.5 μg of pcDNA3.1-HA-Ub plasmid expressing HA-ubiquitin. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting analysis. For analysis of the IκBα expression, 293T cells were transfected with 0.6 μg pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578) or empty vector pCAGGS. Cells were stimulated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) at 24 h posttransfection and harvested at 5, 10, 15, and 30 min after TNF-α stimulation.

Luciferase reporter assays.

A reporter gene assay was performed using the dual luciferase reporter system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured with a luminometer (Bethold). Values for each sample were normalized using the Renilla luciferase values.

In vitro IκBα de-Ub assay.

The detailed method for the in vitro IκBα deubiquitination (de-Ub) assay was described previously (51). Briefly, the polyubiquitinated IκBα substrate was prepared by cotransfecting the HEK-293T cells with plasmid expression of HA-ubiquitin, Flag-IκBα, IKKβ, and FWD1. At 36 to 48 h posttransfection, cells were incubated with MG-132 (40 μM) for 1 h and then stimulated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for 15 min. Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer A (buffer C [20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 0.2% NP-40] supplemented with fresh protease inhibitors [1 μg/ml pepstatin, 3 μg/ml aprotinin, 20 μM leupeptin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride {PMSF}, 1 mM EGTA, and 1 mM EDTA], phosphatase inhibitors [10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM NaF, and 0.4 mM sodium orthovanadate], and 5 mM N-ethylmaleimide [NEM] [for the inhibition of endogenous deubiquitinating enzymes]). Cell lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration of the clarified lysate was determined using a Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Lysates were diluted to 4 mg/ml in lysis buffer A, and immunoprecipitation was performed using 24 μl of a 50% slurry of anti-HA resin per milligram of cell lysate protein. The immune complexes were incubated at 4°C overnight and washed five times in lysis buffer A and five times in reaction buffer A (buffer C supplemented with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 1% bovine serum albumin [BSA], phosphatase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors minus leupeptin, pH 7.5). The immune complex was suspended as 15% slurry of anti-HA matrix-protein complexes in reaction buffer A for subsequent use as a substrate for the deubiquitination assay.

For preparation of the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain for the deubiquitination assay, 293T cells were transfected by the pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578) plasmid. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were washed three times in PBS and lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer B (buffer C supplemented with 1 mM dithiothreitol, phosphatase inhibitors, and protease inhibitors). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 10 min, and the supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined using a Bradford protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Approximately 15 min prior to use in deubiquitination reactions, lysates were diluted to 10 mg/ml in lysis buffer B, and dithiothreitol was added to give a final concentration of 5 mM.

To determine the ability of nsp2 OTU to deubiquitinate polyubiquitinated IκBα substrate, 10 μl of nsp2 OTU (10 mg/ml) was added to 20 μl of the substrate and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 10 μl of 4× SDS sample buffer. Reaction products were heated in 95°C for 5 min, separated in 15% SDS-PAGE gel, and detected by Western blot analysis using an anti-IκBα carboxyl terminus rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

In vitro deconjugation assay.

The K48-linked polyubiquitin chain (Ub2-7) was purchased from Boston Biochem (Cambridge, MA). The reaction was performed in reaction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 5 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM DTT) at 37°C for 2 h. The PRRSV nsp2 OTU protein was immunoprecipitated from the pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578) plasmid-transfected 293T cells by use of mAb SD36-19 and protein-A Sepharose beads. As a negative control, mAb SD36-19 was also used to immunoprecipitate the proteins from nontransfected cells. The immunoprecipitated products were incubated with 2.5 μg of Ub2-7 chains. Reactions were terminated by addition of Laemmli sample buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis on a 15% polyacrylamide gel. Proteins were visualized by Coomassie blue dye staining.

Immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for p65 translocation.

HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing nsp2 (0.3 μg) and p65 (0.1 μg). The empty plasmid was used as a negative control. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 2 h. Cells were fixed with 2.5% formaldehyde for 20 min and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for an additional 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed three times with PBS and stained with anti-p65 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-nsp2 rabbit polyclonal antibody. Following a wash with PBS, cells were stained with DyLight 549-conjugated goat anti-mouse (p65) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (nsp2) secondary antibodies (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). Nuclear localization of p65 was observed under an inverted fluorescence and phase-contrast microscope (Olympus). Images were taken at a ×200 or ×400 magnification and processed with DP-BSW (version 03.02; Olympus) and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 software.

Western blotting.

Cell lysates were heated in Laemmli sample buffer for 10 min and separated by SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane as we described previously (61). After the blotting, membranes were blocked with PBST (1× PBS in 0.05% Tween 20) and 5% nonfat dry milk. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature and then incubated at 4°C overnight. After a wash with PBST, DyLight 680 labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody or DyLight 800 labeled goat anti-mouse antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) was added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The blots were developed under the appropriate excitation wavelength using a digital image system (Odyssey infrared imaging system; LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE). For detecting the expression of PRRSV proteins, MAb SD36-19 or rabbit antisera specific to nsp2 was used. For the detection of IκBα expression, a nitrocellulose membrane was probed with rabbit anti-total IκBα or rabbit anti-Ser32/36-IκBα recognizing phosphorylated IκBα (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The anti-IKKβ rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to detect the IKKβ expression. The mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (Lamda Biotech) was used as an internal control.

nsp2 OTU domain mutant construction.

Each individual point mutation was introduced into the ES2 epitope or protease catalytic sites on the OTU domain region of pSD01-08 full-length cDNA using a modified overlapping extension PCR technique as we described previously (13, 20). Figure 5 shows each mutant construct. The corresponding mutations were also introduced into the pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-883) construct. To rescue the recombinant virus, the full-length cDNA plasmid was in vitro transcribed, and the full-length transcript was used for transfection of BHK-21 cells. Detailed methods for in vitro transcription and transfection of BHK-21 cells have been described in previous publications (13, 14). To rescue the virus, cell culture supernatant obtained at 24 to 48 h posttransfection was passaged on MARC-145 cells. Two days after infection, rescued infectious virus was confirmed by an indirect immunofluorescence assay using nsp2- and nucleocapsid (N) protein-specific monoclonal antibodies SD36-19 and SDOW17 (34), respectively. Infected cells were fixed with 80% acetone and incubated with MAb SD36-19 at 37°C for 1 h. After three washes in PBS, the DyLight 549-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (red fluorescence) was added as a secondary antibody for 1 h at 37°C. Cells were washed again with 1× PBS and stained with FITC-conjugated SDOW17 overnight at 4°C. Cell preparations were imaged under an inverted fluorescence and phase-contrast microscope (Olympus). Images were taken with ×200 or ×400 magnification and processed with DP-BSW (version 03.02; Olympus) and Adobe Photoshop 6.0 software.

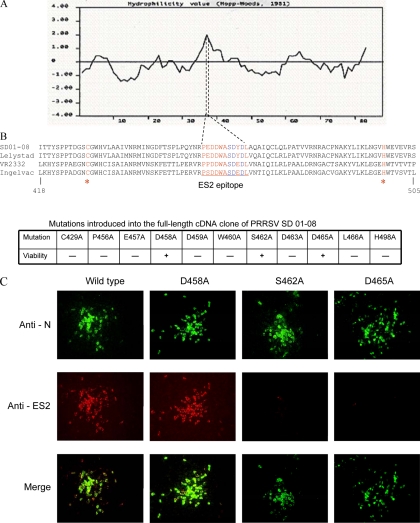

FIG. 5.

Analysis of mutations introduced into the nsp2 OTU domain region of the virus. (A) Hydrophilicity plot of the OTU domain region, showing that the ES2 epitope region contains the highest hydrophilic value. (B) Sequence alignment of the OTU domain region. The ES2 epitope region (aa 456 to 466) is indicated. Red and blue indicate amino acids being tested by site-directed mutagenesis; blue indicates that the S462A, D463A, or D465A mutation caused the loss of MAb SD36-19 recognition. Amino acid numbers are based on pp1a of SD01-08. (C) Recombinant viruses recovered from the nsp2 OTU domain mutation. Cells were stained with anti-ES2 MAb and SD36-19, and the DyLight 549-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (red fluorescence) was used as the secondary antibody for MAb SD36-19 staining. The FITC conjugated anti-N MAb SDOW17 was used to detect N protein expression. Images were obtained by fluorescence and phase-contrast microscopy using a 20× objective.

Growth kinetics and plaque assay.

Growth kinetics was examined by infecting MARC-145 cells with nsp2 mutants and parental virus at an MOI of 0.1. Infected cells were collected at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h postinfection, and virus titers were determined by an IFA with MARC-145 cells and quantified as numbers of fluorescent focus units per ml (FFU/ml). Plaque morphologies between the recombinant virus and parental virus were compared by a plaque assay with MARC-145 cells. Confluent cell monolayers were infected with seriously diluted parental or mutant virus. After 2 h, cell culture supernatant was removed, and an agar overlay was applied. Plaques were detected after 3 to 5 days of incubation at 37°C and stained by using 0.1% crystal violet.

Sequencing of the nsp2 OTU domain mutation region.

To determine the stability of the mutations introduced into the nsp2 OTU domain region, cell lysates from recombinant virus-infected cells were harvested, and RNA was extracted using a QiaAmp viral RNA kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The corresponding deletion regions were amplified by RT-PCR. The PCR product was sequenced at the Iowa State University DNA sequencing facility (Ames, IA).

RESULTS

The PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain inhibits NF-κB activation.

Previous studies from our laboratory (52) and others (3) identified PRRSV nsp2 as one of the viral proteins that inhibit the IFN-β production. However, the detailed mechanism of nsp2 involved in interfering with IFN-β induction has not been determined. Since nsp2 is the largest viral protein of PRRSV (1,061 amino acids [aa] in SD01-08 virus), initially, we determined which region of nsp2 is responsible for inhibition of IFN-β synthesis. Plasmids expressing full-length nsp2 and four truncations of the nsp2 protein were constructed (Fig. 1A). nsp2 is a proteolytic cleavage product from pp1a polyprotein. In our previous study (9), we identified the N-terminal cleavage site of nsp2, which is located at 385G↓A386 of pp1a in SD01-08. There are two predicted C-terminal cleavage sites of PRRSV nsp2, based on the study of EAV (1, 66). A previous study (19) determined that the second cleavage site is most likely the actual cleavage site. The classification of the nsp2 cysteine protease as an OTU family member suggests that the enzyme does not cleave inside but cleaves downstream of the proposed Gly-Gly doublet (15), which is predicted to be located at 1446G↓A1447 of pp1a in SD01-08. Therefore, full-length nsp2 contains aa 386 to 1446 of pp1a. Each of the nsp2 truncation contains amino acids in the N-terminal or C-terminal region of nsp2 as shown in Fig. 1A. These truncations were designed based on the predicted secondary protein structure analysis (PepTool; BioTools, Inc.), which maintains the integrity of the protein secondary structure in each truncation. The nsp2 (386-578) construct was designed to maintain the conformation of the cysteine protease domain based on the study by Han et al. (19). Each of these protein-encoding regions was cloned into the pCAGGS plasmid, and protein expression from these plasmids was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B).

To determine which region of the nsp2 has an effect on IFN-β production, we used an IFN-β promoter-luciferase reporter plasmid (p125-Luc) that expresses the firefly luciferase under the control of the IFN-β promoter. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with each individual plasmid that expresses full-length nsp2 or a portion of nsp2, p125-Luc, and a Renilla luciferase expression plasmid (pRL-SV40) to normalize expression levels of samples. As a positive control, the influenza NS1 gene was used to cotransfect the cells with the reporter plasmid. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were infected with Sendai virus (SeV) to induce luciferase production. As we expected, the expression of influenza NS1 significantly inhibited the luciferase expression. In contrast, a strong reporter signal was observed in cells transfected with empty plasmid pCAGGS after infection with SeV. The PRRSV nsp2 expression reduced the level of the IFN-β promoter-driven luciferase reporter signal, and this effect is dose dependent (Fig. 1C). The N-terminal region of nsp2 (386-578) showed the greatest inhibition of luciferase expression (Fig. 1D). This result indicates that expression of the PRRSV nsp2 protein decreases the level of IFN-β induction, and this activity was mapped to the N-terminal cysteine protease (OTU) domain region of the nsp2.

As indicated previously (15), some of the OTU proteases have the ability to inhibit NF-κB-dependent signaling. To confirm that the PRRSV nsp2 protein had a specific effect on the NF-κB signaling pathway for IFN-β production, activation of NF-κB was examined using a reporter plasmid containing a firefly luciferase gene under the control of an NF-κB responsive promoter with two NF-κB binding sites (pNF-κB-Luc). HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with full-length PRRSV nsp2 or the OTU domain region [pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578)] and expression plasmids pNF-κB-Luc and pRL-SV40. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with TNF-α to induce luciferase production. As we expected, PRRSV nsp2 proteins affect the NF-κB-dependent reporter gene expression, and the OTU domain region resulted in the greatest inhibition of the reporter gene expression. As a control, point mutations in protease active sites (C429A or H498A) were introduced. The result showed that expression of the mutated cysteine protease domain did not have any effect on the reporter gene expression (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

PRRSV nsp2 inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway. (A) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with pNF-κB-Luc, pRL-SV40, and pCAGGS expressing nsp2 proteins or pCAGGS empty vector for 20 h. Cells were then treated with 20 ng/ml TNF-α for 6 h. (B to D) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with the plasmid pEGFP-N1-MAVS (B), pCMV2-IKK2-WT (C), or pEGFP-N1-p65 (D), along with pNF-κB-Luc, pRL-SV40, and pCAGGS expressing the nsp2 OTU domain, for 20 to 24 h. Plasmids expressing the protease active-site mutation were used as negative controls. Cells were harvested and measured for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities. Relative luciferase (RLU) activity is defined as the ratio of firefly luciferase reporter activity to Renilla luciferase activity. Each data point shown represents a mean value from three experiments. Error bars show standard deviations for the normalized data.

The PRRSV OTU domain prevents IκBα degradation by interfering with the polyubiquitination process.

We further determined which step in the NF-κB signaling pathway is targeted by the nsp2 OTU domain. NF-κB is sequestered in the cytoplasm of unstimulated cells through binding to IκB. Upon stimulation, the MAVS, IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ kinases are activated, which initiates IκB phosphorylation and is followed by K48-linked polyubiquitination targeting IκB for proteasomal degradation. Degradation of IκB releases NF-κB dimers for translocation to the nucleus, where they regulate transcription of IFN genes (26). We cotransfected cells with a plasmid expressing the MAVS, IKKβ, or NF-κB subunit p65 protein, a plasmid expressing individual PRRSV proteins, the plasmid pRL-SV40, and the pNF-κB-Luc reporter plasmid. As shown in Fig. 2B to D, overexpression of MAVS, IKKβ, or p65 in cells led to activation of transcription from the reporter, and coexpression of the nsp2 OTU domain with p65 did not affect this activity. However, the luciferase expression was suppressed by coexpression of the nsp2 OTU domain with MAVS or IKKβ. This result indicates that PRRSV nsp2 blocks the step(s) upstream of p65 activation in the NF-κB signaling pathway.

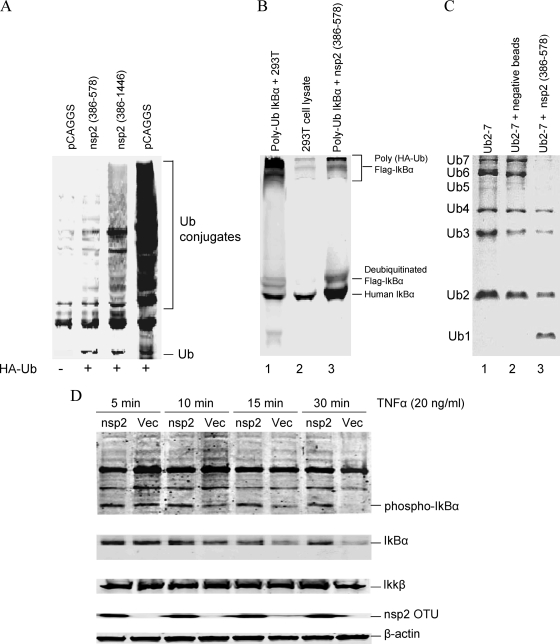

As Frias-Staheli et al. (15) indicated, OTU domains have ubiquitin-deconjugating (de-Ub) activity. The activation of NF-κB requires the ubiquitination of IκBα. Therefore, we hypothesized that the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain inhibits the NF-κB activation by interfering with the ubiquitination of IκBα and subsequently preventing IκBα degradation. To test our hypothesis, we transfected 293T cells with a plasmid expressing HA-tagged ubiquitin and the plasmid expressing full-length nsp2 or the OTU domain region. The empty pCAGGS plasmid was used as a control. As shown in Fig. 3A, expression of nsp2 resulted in decreased expression of ubiquitin-conjugated proteins. Again, the OTU domain region has the greatest effect on the ubiquitin conjugation. To determine the specific effect of this region on the IκBα ubiquitination process, we performed an in vitro assay to investigate the IκBα deubiquitination. Initially, we generated polyubiquitinated IκBα as the substrate. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing HA-ubiquitin, Flag-IκBα, IKKβ, and FWD1/betaTrCP. IKKβ was included to enhance the phosphorylation of IκBα, and FWD1/betaTrCP is a component of the IκBα ubiquitin ligase complex that catalyzes IκBα ubiquitination. To enrich the levels of polyubiquitinated IκBα, proteasome inhibitor MG-132 was added to cell culture and incubated for 1 h, and then cells were stimulated by TNF-α for 15 min. After TNF-α stimulation, the polyubiquitinated protein complex was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysate by use of anti-HA beads. The immunoprecipitated protein complex was used as a substrate in the in vitro assay to assess the deubiquitinating activity of the nsp2 OTU domain. The nsp2 OTU domain was prepared by transfecting the 293T cells with the plasmid expressing the nsp2 OTU domain. The deubiquitination reaction was performed by combining the HA immune complexes with cell lysates from OTU domain-transfected 293T cells, and the reaction product was analyzed by Western blotting using the anti-IκBα carboxyl-terminus antibody. As shown in Fig. 3B, poly-HA-ubiquitinated Flag-IκBα was present in the substrate (lane 1), and it was deubiquitinated by incubation with cell lysate from nsp2 OTU-transfected 293T cells (lane 3). IκBα is ubiquitinated by the K48-linked polyubiquitin chain. To further verify that the nsp2 OTU domain is targeting directly on the conjugation of the K48 polyubiquitin chain, we performed the in vitro ubiquitin deconjugation assay. The nsp2 OTU domain was immunoprecipitated from the OTU-transfected 293T cells and incubated with the K48-linked polyubiquitin chain. The result showed that the nsp2 OTU domain cleaved the K48-linked poly-Ub chains into monomers (Fig. 3C). We further determined the effect of the nsp2 OTU domain on IκBα degradation. HEK-293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing the nsp2 OTU domain and stimulated with TNF-α. The cell lysate was analyzed by Western blotting. As shown in Fig. 3D, no differences were observed for IKKβ expression levels between different treatments. However, at the early time point (5 min) of stimulation, TNF-α induced increased levels of phosphorylated IκBα and total IκBα in the nsp2 OTU domain- and pCAGGS empty plasmid (Vec)-transfected cells. We started observing degradation of the levels of phosphorylated IκBα and total IκBα in empty-plasmid-transfected cells at 10 min poststimulation, and at 30 min postinfection, the levels of phosphorylated IκBα and total IκBα were barely observed. In contrast, in the cells transfected with the nsp2 OTU domain, phosphorylated IκBα and total IκBα seem to maintain similar levels through the time course.

FIG. 3.

The PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain prevents IκBα degradation through interference with IκBα ubiquitination. (A) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing HA-tagged ubiquitin and a plasmid expressing nsp2 protein or the pCAGGS empty plasmid. Cells were lysed at 24 h posttransfection and analyzed by Western blotting using anti-HA MAb. (B) In vitro IκBα deubiquitination assay. (Lane 1) Polyubiquitinated IκBα (substrate) incubated with the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain. (Lane 2) Cell lysate from nontransfected HEK-293T cells. (Lane 3) Polyubiquitinated IκBα (substrate) incubated with the cell lysate from nontransfected HEK-293T cells. Reaction products were analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-IκBα carboxyl-terminus antibody. (C) In vitro ubiquitin deconjugation assay. (Lane 1) Uncleaved K48-linked polyubiquitin chain (Ub2-7). (Lane 2) Ub2-7 ubiquitin chain incubated with protein A Sepharose beads (immunoprecipitated from nontransfected 293T cells). (Lane 3) Ub2-7 ubiquitin chain incubated with the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain. Reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The expected sizes of the ubiquitin species are indicated at the left side of the panel. (D) HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with the plasmid expressing nsp2 OTU (nsp2) or the pCAGGS (Vec) empty plasmid. Transfected cells were treated with TNF-α (20 ng/ml) for the amounts of time indicated and subsequently immunoblotted. Western blots were analyzed for either total IκBα or phospho-IκBα. The anti-IKKβ rabbit polyclonal antibody was used to detect the IKKβ expression. The β-actin was detected as a loading control.

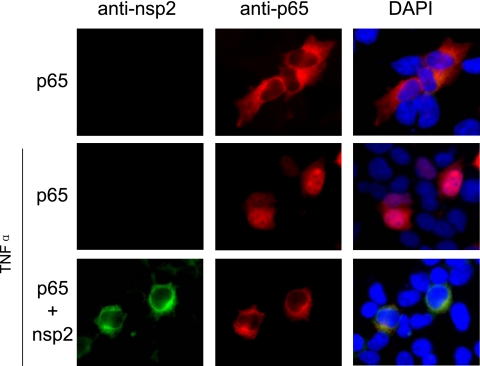

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain region has deubiquitination activity. It has the ability to interfere with the IκBα polyubiquitination process and subsequently prevents IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation. We further confirmed these results by examining the effect of nsp2 on NF-κB nuclear translocation upon TNF-α treatment. As shown in Fig. 4, p65 was retained in the cell cytoplasm when nsp2 protein was expressed in cells. Overall, these results demonstrate the ability of PRRSV nsp2 to antagonize the immune response by affecting the NF-κB signaling pathway that is regulated by ubiquitination.

FIG. 4.

Effect of PRRSV nsp2 protein on NF-κB translocation. HEK-293T cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h and then stimulated with TNF-α for 2 h. Cells were fixed and stained with anti-p65 monoclonal antibody and anti-nsp2 rabbit polyclonal antibody. DyLight 549-conjugated goat anti-mouse (red fluorescence) and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibodies were used as the secondary antibody. The cell nucleus was stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; blue fluorescence). The protein localization was analyzed by fluorescence phase-contrast microscopy using a 40× objective.

The recombinant viruses with a mutation in the OTU domain are attenuated for growth in cell culture.

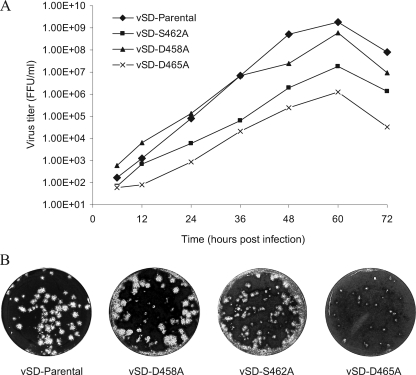

To determine whether the nsp2 antagonist function can be removed from the virus, we introduced point mutations targeting a protein region, 456-PEDDWASDYDL, which is predicted to be at the surface of the OTU domain region on the basis of hydrophilicity analysis (Fig. 5A) (21). Sequence analysis revealed that this region contains an identified B-cell epitope, ES2 (36), and is well conserved among different strains. In our previous study, deletion of this epitope generated nonviable virus (8). In this study, nine single point mutations were introduced in the ES2 epitope region using a full-length cDNA infectious clone, pSD01-08 (Fig. 5B, lower panel). As a control, mutations in cysteine protease catalytic sites C429A and H498A were also introduced. To recover the recombinant virus, the plasmids containing the full-length genome with nsp2 mutations were linearized and in vitro transcribed as described previously (14). The in vitro-transcribed capped RNA was transfected into BHK-21 cells. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were examined for the expression of nsp2 and N protein by fluorescent-antibody staining using the MAbs specific to the nsp2 ES2 epitope (MAb SD36-19) and N protein (MAb SDOW17) (34). The results showed that about 10% of transfected cells expressed nsp2 and N protein for the P456A, E457A, D458A, D459A, and L466A constructs. Interestingly, MAb SD36-19 that is specific to the ES2 epitope did not recognize the S462A, D463A, and D465A mutants, but a bright fluorescent signal was detected with the use of N protein-specific antibody SDOW17. There were no fluorescent signals for the C429A, W460A, and H498A mutations. Supernatants from the transfected BHK cells were passaged onto MARC-145 cells. After 72 h, MARC-145 cells were stained with nsp2- and N protein-specific monoclonal antibodies. Five single mutations, D458A, D459A, S462A, D463A, and D465A, stained positive for N protein. For the D459A and D463A mutants, only single fluorescent cells were observed, which suggested that the mutation of the amino acids D459 and D463 affects the cell-to-cell spreading of the virus to form clusters. We failed to detect any viral proteins on the second passage, suggesting that these mutations may affect virion assembly or release of infectious virions. The D458A, S462A, and D465A mutants were stained as bright clusters of cells by use of SDOW17, and viable viruses were recovered from the cell culture (designated vSD-D458A, vSD-S462A, and vSD-D465A recombinant viruses) (Fig. 5C). Again, the S462A and D465A mutations were not recognized by MAb SD36-19, suggesting that these mutations altered the conformation of the ES2 epitope and subsequently blocked the binding of MAb to the ES2 epitope. Interestingly, the three residues (S462, D463, and D465) that block MAb recognition with alanine substitution are next to each other, which suggests that 462-SDY(E)D is the key region for interaction with the MAb 36-19. We did not test the mutation on Y464, since this residue is not conserved between type I and type II PRRSVs. We also passed the cell culture supernatant from transfected BHK-21 cells onto porcine alveolar macrophages, and the IFA result was similar to that obtained with MARC-145 cells. To confirm the stability of the deletion region, we sequenced the corresponding region from passage 3 of each mutant in cell culture. The results showed that the corresponding mutation remains present in each mutant. Growth kinetic analysis showed that the vSD-S462A (peak viral titer = 1.8 × 107 FFU/ml) and vSD-D465A (peak viral titer = 1.25 × 106 FFU/ml) mutants grew slower and had lower average viral titers than the parental virus (peak viral titer = 1.83 × 109 FFU/ml) (Fig. 6A). The growth phenotypes of the deletion mutants were further determined by a plaque assay, and the result was consistent with that of growth kinetic analysis. In comparison to the parental virus, vSD-S462A and vSD-D465A mutants showed reduced plaque size (Fig. 6B). The vSD-D465A mutant showed smaller pinpoint plaques, which indicates that D465A mutation has the greatest effect on the virus growth.

FIG. 6.

In vitro characterization of nsp2 OTU domain-mutated recombinant viruses. (A) Growth kinetics of nsp2 OTU mutants. MARC-145 cells were infected in parallel at an MOI of 0.1 with recombinant and parental viruses at passage 3. At 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h postinfection, cells were harvested and the virus titers were determined by an immunofluorescence assay with MARC-145 cells. The results are mean values from three replications of the experiment, and viral titers are expressed as numbers of fluorescence focus units per milliliter (FFU/ml). (B) Plaque morphology of nsp2 OTU mutants and parental viruses. Confluent cell culture monolayers were infected with viruses at an MOI of 0.1. At 2 h postinfection, cell culture supernatant was removed and an agar overlay was applied. Plaques were detected after 5 days of incubation at 37°C and stained by 0.1% crystal violet.

The OTU domain mutants have a reduced ability to inhibit NF-κB activation.

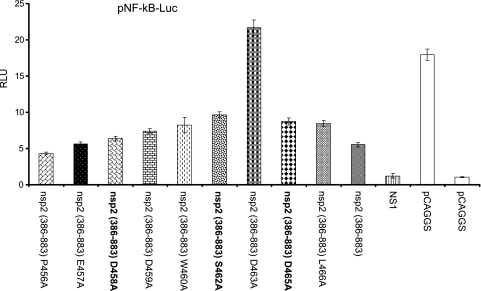

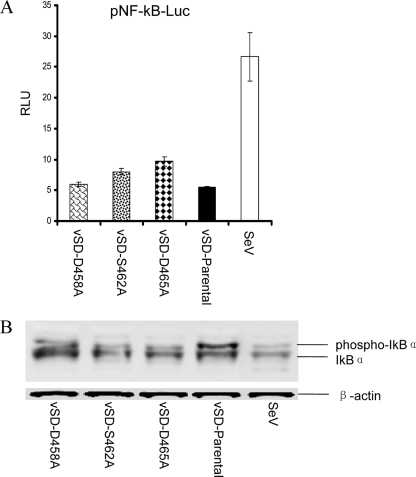

To determine whether the OTU domain mutations could alter the effect of the virus on the innate immune response, initially, we performed the in vitro NF-κB promoter-luciferase reporter assay using the nsp2 OTU domain mutants. Since the expression of the pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-578) construct with the S462A, D463A, and D465A mutations could not be recognized by MAb SD36-19, we expressed the pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-883) construct with a point mutation in its OTU domain region. nsp2 (386-883) contains epitopes downstream of the ES2 epitope (36), which can be recognized by the rabbit polyclonal antibody. The NF-κB promoter-luciferase assay result revealed that the C429A, D463A, and H498A mutations dramatically impaired the ability of nsp2 to inhibit NF-κB activation (Fig. 7). Unfortunately, these mutations did not recover the viable virus. For those three mutations (D458A, S462A, and D465A) that generated viable viruses in comparison to the level of reporter signals from wild-type pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-883)-transfected cells, we observed about a 2-fold increase of luciferase reporter signal in cells transfected with pCAGGS-nsp2-D465A and pCAGGS-nsp2-S462A. We did not observe much difference in luciferase reporter levels from cells transfected with pCAGGS-nsp2-D458A and wild-type pCAGGS-nsp2 (386-883) (Fig. 7). Since the D458A, S462A, and D465A mutations generated viable viruses, the three recombinant viruses vSD-D458A, vSD-S462A, and vSD-D465A were further tested to determine whether these mutations could reduce the ability of the virus to inhibit NF-κB activation. MARC-145 cells were infected with each individual recombinant virus. At 2 hours postinfection, cells were transfected with pRL-SV40 and the pNF-κB-Luc reporter plasmid. After 24 h posttransfection, transfected cells were assayed for NF-κB activation. As shown in Fig. 8A, in comparison to what was found for SeV-infected cells, infection with wild-type virus significantly inhibited NF-κB-dependent luciferase expression. Although the S462A and D465A mutations did not dramatically increase the luciferase expression levels, a certain level of improvement was observed. There was about a 2-fold increase of luciferase reporter level in cells infected with vSD-D465A, while a slightly higher level of reporter signal was observed in vSD-S462A-infected cells in comparison to the level for those cells infected with wild-type virus. Again, we did not observe much difference in luciferase reporter levels for cells infected with vSD-D458A and wild-type virus. This result was further supported by the immunoblotting data. As shown in Fig. 8B, the amounts of IκBα were reduced in vSD-S462A and vSD-D465A mutant-infected cells compared to those in wild-type virus and vSD-D458A-infected cells. Taken together, these results indicate that the S462A and D465A residues in the OTU domain region of the virus could be altered with no effect on virus viability and that such mutations could improve the ability of the virus for NF-κB activation.

FIG. 7.

Mutations in the ES2 epitope region altered the effect of the nsp2 OTU domain on NF-κB activation. HEK-293T cells were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing each individual nsp2 OTU mutant, pCAGGS empty vector, or a plasmid expressing influenza virus NS1, along with pRL-SV40 and the reporter plasmid pNF-kB-Luc. At 20 h posttransfection, cells were infected with Sendai virus for 16 h to stimulate luciferase production. Cells were harvested and measured for firefly and Renilla luciferase activities. Relative luciferase (RLU) activity is defined as the ratio of firefly luciferase reporter activity to Renilla luciferase activity. Each data point shown represents a mean value from three experiments. Error bars show standard deviations for the normalized data.

FIG. 8.

Recombinant viruses with mutation in the OTU domain have a reduced ability to inhibit NF-κB activation. MARC-145 cells were infected by each recombinant virus as indicated. Sendai virus was used to infect MARC-145 cells as a control. At 2 hours postinfection, plasmids pNF-κB-Luc and pSV40-RL were transfected into the infected cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were harvested for a luciferase reporter assay (A) and Western blot analysis (B). (A) Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured from the cell lysate and are reported as relative luciferase (RLU) activity. RLU is defined as the ratio of firefly luciferase reporter activity to Renilla luciferase activity. Each data point shown represents a mean value from three experiments. Error bars show standard deviations for the normalized data. (B) Cell lysate from infected MARC-145 cells was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with an anti-IκBα antibodies. The positions of IκBα and phosphorylated IκBα are indicated. The β-actin was detected as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

The type I interferon (IFN) innate immune system is the first line of defense against viral infection. There is an extensive body of literature describing the effects of cytokines on PRRSV replication and cytokine-mediated events, particularly IFN-mediated innate immune responses, which are effective against PRRSV infection (2, 6, 29, 32, 37, 43, 44). However, under natural conditions, PRRSV infection causes poor antiviral type I interferon and other cytokine responses. Many viruses express proteins to counteract the host innate immune response. In this study, we identified the PRRSV nsp2 protein as one of the interferon antagonists. Previous studies from our laboratory (9) and others (3) identified that two other PRRSV nonstructural proteins, nsp1α and nsp1β, also function as interferon antagonists. These findings indicate that several replicase proteins of PRRSV involve important functions in regulating the host innate immune response, in addition to their critical roles in viral replication, which suggests an important role for these nonstructural proteins in pathogenesis and disease outcomes. It is intriguing that PRRSV carries at least three interferon antagonist genes. The pathogenic basis for encoding such a repertoire of antagonists needs to be studied further. Many pathogenic viruses, such as the coronaviruses, poxviruses, and paramyxoviruses, carry multiple interferon antagonist genes as well. It seems that viruses encode multiple IFN antagonists to suppress the induction of innate immune responses during the early phases of infection to allow for efficient viral replication and spread. On the other hand, different antagonists may target different components of the host communication network by different mechanisms to ensure complete shutting down of the host innate immune response. This would explain why the induction of type I interferon and other innate cytokines was inhibited during the early stage of PRRSV infection.

The results from this study showed that PRRSV nsp2 specifically targets the NF-κB activation pathway for interferon induction. NF-κB is a critical regulator of host innate and adaptive immunity. It also plays a key role in the regulation of cell proliferation and cell survival (7, 25). Viruses have developed various strategies for either activation or inhibition of the NF-κB pathway in order to survive in host cells (46). Some viruses, such as African swine fever virus and influenza A virus, block NF-κB activation in order to evade the innate immune response (39, 58). On the other hand, viruses evolve mechanisms to directly activate the NF-κB pathway. Since NF-κB plays an important role in apoptosis of virus-infected cells, NF-κB activation could be either an antiapoptotic response for maximizing the viral progeny production by prolonging host cell survival or a proapoptotic response as a mechanism for releasing mature viral particles and increasing intracellular spreading of the virus (4, 30). Previous studies have demonstrated that viruses, including hepatitis C virus, reovirus, and herpes simplex virus, have evolved strategies to activate NF-κB in favor of viral progeny production and intracellular spreading (10, 17, 59). Although NF-κB plays an important role in the regulation of immune response and cell proliferation, little is known how PRRSV modulates the NF-κB signaling pathway. Previous work from Lee and Kleiboeker (24) showed that PRRSV activated the NF-κB pathway through IκB degradation at the later stage of infection in vitro (after 48 h postinfection). They performed examinations at 5, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h postinfection, and NF-κB was not activated during the early time period (5, 24, and 36 h). In our study, we demonstrated that PRRSV inhibited the NF-κB activation at 26 h postinfection (Fig. 8) and that nsp2 has a major role in this effect. We also observed the activation of the NF-κB response at the later stage of SD01-08 virus infection (after 72 h postinfection) (data not shown). The results from these two studies correlate very well, suggesting the dynamic regulatory role of nsp2 in NF-κB activation during the progression of PRRSV infection. We postulate that at the early stage of infection, PRRSV expresses a protein (nsp2) or proteins (including nsp2) to inhibit NF-κB activation as one of the mechanisms for escaping the host innate immune response. After the virus established its replication in host cells and maximized the viral progeny production, the virus would trigger the activation of NF-κB for inducing host cell apoptosis, which results in the releasing of mature viral particles. In cell culture, we normally observe the cytopathic effect after 2 to 3 days (48 to 72 h) of infection. This notion is further supported by the data from Lee and Kleiboeker (24), who showed that the activation of NF-κB requires virus replication progression but that NF-κB activation was significantly reduced by UV-inactivated virus. As Lee and Kleiboeker (24) indicated, it is possible that PRRSV replication and viral protein expression are prerequisites for activation of the NF-κB pathway. The nsp2 protein is a nonstructural protein, and it does not incorporate into the virion. Therefore, the UV-inactivated virus does not express nsp2. We speculate that the nsp2 protein may interact with a different viral (or host) protein(s) at different stages of infection to turn on/off its function on NF-κB activation.

A more interesting finding from this study is that the OTU domain (cysteine protease) region of nsp2 is determined to be responsible for interrupting the NF-κB signaling. This conclusion is supported by the earlier work by Frias-Staheli et al. (15), who indicated that the OTU domain of EAV, a virus in the same family as PRRSV, has the ability to suppress NF-κB activation. It is intriguing that our results revealed that the OTU domain of nsp2 has de-Ub function and that this function is linked to the IκBα polyubiquitination. Coronaviruses are another group of viruses in the same order as PRRSV (order Nidovirales), which has a genome organization similar to that of PRRSV. The coronavirus papain-like protease (PLP), a homolog of PRRSV nsp2 cysteine protease, is reported to possess de-Ub activity. Zheng et al. (65) reported that PLP2 of mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) is a potent deubiquitinase, which strongly inhibits host type I interferon production. They proposed that the de-Ub activity of MHV PLP2 blocks IRF3 function, leading to the suppression of IFN production. Frieman et al. (16) showed that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) PLP possesses de-Ub function and that PLP is able to block both NF-κB and IRF3 signaling pathways. Since the OTU domain has been proposed to have global deubiquitinating activity (15), it is possible that PRRSV nsp2 also prevents ubiquitination of other intermediate components in the NF-κB signaling pathway, such as RIP1/TRAF2 and IKKγ/NEMO, which are essential for activation of NF-κB. In addition, several key enzymes in the interferon signaling pathway, such as TBK1, IKKi, and IKKβ, contain ubiquitin-like domains that are critical for their enzymatic activity (22, 27). The PRRSV nsp2 OTU domain may also target their activities. Future study is needed to elucidate its interaction with other host proteins in the interferon-signaling network.

The data from this study demonstrate that the structural integrity of the nsp2 cysteine protease domain is important for IFN antagonism. We expressed four truncations of nsp2 for determining the region that is responsible for IFN antagonism. The shortest truncation of nsp2 is that of the N-terminal 192 amino acids, which was designed by maintaining cysteine protease function based on the previous study (19). Further truncation in this region causes the loss of the IFN antagonist function (data not shown). Mutagenesis of the key catalytic residue in the protease active site knocked out the nsp2 antagonism function on IFN-β and NF-κB activity, which suggests that the catalytic region may be directly involved in the nsp2 antagonism function. Alternatively, the mutations may alter the protein domain structure such that the cellular proteins interacting with the wild-type nsp2 protease can no longer bind to the mutant form. This notion is further strengthened by introducing mutations into the full-length cDNA infectious clone of PRRSV and recovering the recombinant virus by use of reverse genetics. As we expected, mutations introduced into the protease active sites did not recover viable viruses. Among the nine mutations that we introduced into the ES2 epitope region, six mutations did not recover the viable viruses, and these mutations affected the ability of nsp2 to inhibit the NF-κB to various degrees. The C429A, D463A, and H498A mutations completely abolished the NF-κB antagonism function of nsp2. This result suggests that the protease function of nsp2 is directly coupled with the interferon antagonist function. This finding is consistent with the result obtained by Han et al. (19). They tested the corresponding mutations using a type II PRRSV, VR2332. The C55, H124, W86, and D89 mutations in nsp2 (corresponding to C429, H498, W460, and D463, respectively, of pp1a in SD01-08) abolished the proteolytic cleavage activity of the cysteine protease, resulting in nonviable virus. Three mutations, D458A, S462A, and D465A, recovered viable viruses. The S462A and D465A mutations caused the loss of the binding of ES2-specific MAb, which suggests that these mutations caused a certain level of alteration of the protein domain conformation. This is further supported by the growth characteristics of the S462A and D465A mutants, which showed an attenuated phenotype in cell culture. In contrast, the D458A mutant can be recognized by ES2-specific MAb, and it has growth characteristics similar to those of wild-type virus. Although the S462A and D465A mutations did not dramatically alter the virus's ability to inhibit NF-κB activation, these mutants were unable to inhibit NF-κB activation as effectively as the wild-type virus. Future study will be directed to determine the effect of S462A and D465A mutations on the IFN response in vivo.

Genetic manipulations of viral IFN antagonists will be useful for development of new candidate vaccines. An attractive approach is to generate recombinant viruses with targeted deletions or mutations in genes known for encoding the IFN antagonists. Such mutants are excellent candidates for modified live virus vaccines. The respiratory syncytial and influenza viruses are pioneers in using this approach for vaccine development (53, 55). The respiratory syncytial virus NS2 protein modulates the type I IFN activity through the inhibition of STAT2 in the JAK-STAT pathway (40). Recombinant bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) lacking the NS2 protein induced protection against challenge with virulent BRSV, which was associated with higher BRSV-specific antibody titers and greater priming of BRSV-specific, IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells (55). The NS1 protein of influenza A virus is a potent IFN antagonist. A recombinant influenza A virus expressing an RNA-binding defective NS1 protein induces high levels of IFN response and is attenuated in vivo (12, 53). In our case, the coupling of the nsp2 IFN antagonism with the protease cleavage function makes it difficult to remove the nsp2 IFN antagonism from the virus and, at the same time, to maintain the viability of the virus. Although we have not obtained a recombinant virus with a dramatic improvement in NF-κB response, our study presents the initial effort in an attempt to knock out the IFN antagonist function from the PRRSV. A better approach for knocking out these IFN antagonists is under active investigation in our laboratory.

In conclusion, our results provide direct evidence that PRRSV nsp2 suppresses IFN-β production by blocking the activation of the key transcription factor NF-κB, and this effect was mapped to the N-terminal cysteine protease (OTU) domain region of the protein. The identification and elimination of viral protein functions responsible for immune evasion are fundamental for the development of a modified live PRRSV vaccine. Our mutagenesis and reverse genetics studies demonstrate that type I interferon response could be enhanced by modifying certain amino acids that are located on the cysteine protease (OTU) domain region of nsp2. These findings provide an important insight for future development of genetically modified live-virus vaccines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Adolfo García-Sastre (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY) for providing pCAGGS plasmid, Takashi Fujita (Kyoto University, Tokyo, Japan) for providing the p125Luc plasmid, Domenico Tortorella (Mount Sinai School of Medicine, NY) for providing pcDNA3.1(+)-HA-Ub plasmid, Peter Howley (Harvard Medical School, MA) for contributing the p4489 Flag-beta TrCP plasmid, Anjana Rao (Harvard Medical School, MA) for contributing the pCMV2-IKK2-WT plasmid, and Jurgen Richt (Kansas State University, KS) for providing influenza A/swine/Texas/4199-2/98 virus.

This project was supported by the National Research Initiative of the USDA Cooperative State Research, Education and Extension Service (grant number 2007-01745).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 26 May 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allende, R., T. L. Lewis, Z. Lu, D. L. Rock, G. F. Kutish, A. Ali, A. R. Doster, and F. A. Osorio. 1999. North American and European porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome viruses differ in non-structural protein coding regions. J. Gen. Virol. 80:307-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bautista, E. M., and T. W. Molitor. 1999. IFN gamma inhibits porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus replication in macrophages. Arch. Virol. 144:1191-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beura, L. K., S. N. Sarkar, B. Kwon, S. Subramaniam, C. Jones, A. K. Pattnaik, and F. A. Osorio. 2010. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nonstructural protein 1{beta} modulates host innate immune response by antagonizing IRF3 activation. J. Virol. 84:1574-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowie, A. G., J. Zhan, and W. L. Marshall. 2004. Viral appropriation of apoptotic and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 91:1099-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, E., S. Lawson, C. Welbon, M. P. Murtaugh, E. A. Nelson, J. J. Zimmerman, R. R. R. Rowland, and Y. Fang. 2009. Antibody response of nonstructural proteins: implication for diagnostic detection and differentiation of type I and type II porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 16:628-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buddaert, W., K. Van Reeth, and M. Pensaert. 1998. In vivo and in vitro interferon (IFN) studies with the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV). Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 440:461-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caamaño, J., and C. A. Hunter. 2002. NF-kappaB family of transcription factors: central regulators of innate and adaptive immune functions. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:414-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, Z., X. Zhou, J. K. Lunney, S. Lawson, Z. Sun, E. Brown, J. Christopher-Hennings, D. Knudsen, E. Nelson, and Y. Fang. 2010. Immunodominant epitopes in nsp2 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus are dispensable for replication but play an important role in modulation of host immune response. J. Gen. Virol. 91(4):1047-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, Z., S. Lawson, Z. Sun, X. Zhou, X. Guan, J. Christopher-Hennings, E. A. Nelson, and Y. Fang. 2010b. Identification of two auto-cleavage products of nonstructural protein 1 (nsp1) in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infected cells: nsp1 function as interferon antagonist. Virology 398(1):87-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connolly, J. L., S. E. Rodgers, P. Clarke, D. W. Ballard, L. D. Kerr, K. L. Tyler, and T. S. Dermody. 2000. Reovirus-induced apoptosis requires activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB. J. Virol. 74:2981-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.den Boon, J. A., K. S. Faaberg, J. J. M. Meulenberg, A. L. M. Wassenaar, P. G. W. Plagemann, A. E. Gorbelenya, and E. J. Snijder. 1995. Processing and evolution of the N-Terminal region of the arterivirus replicase ORF1a protein: identification of two papainlike cysteine proteases. J. Virol. 69:4500-4505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donelan, N. R., C. F. Basler, and A. García-Sastre. 2003. A recombinant influenza A virus expressing an RNA-binding-defective NS1 protein induces high levels of beta interferon and is attenuated in mice. J. Virol. 77:13257-13266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang, Y., J. Christopher-Hennings, E. Brown, H. Liu, Z. Chen, S. Lawson, R. Breen, T. Clement, X. Gao, J. Bao, D. Knudsen, R. Daly, and E. A. Nelson. 2008. Development of genetic markers in the nonstructural protein 2 region of a US type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: implications for future recombinant marker vaccine development. J. Gen. Virol. 89:3086-3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fang, Y., R. R. R. Rowland, M. Roof, J. K. Lunney, J. Christopher-Hennings, and E. A. Nelson. 2006. A full-length cDNA infectious clone of North American type 1 porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus: expression of green fluorescent protein in the nsp2 region. J. Virol. 80:11447-11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frias-Staheli, N., N. V. Glannakopoulos, M. Klkkert, S. L. Taylor, A. Bridgen, J. Paragas, J. A. Richt, R. R. R. Rowland, C. S. Schmaljohn, D. J. Lenschow, E. J. Snijder, A. Garcia-Sastre, and H. W. Virgin. 2007. Ovarian tumor domain-containing viral proteases evade ubiquitin- and ISG15-dependent innate immune responses. Cell Host Microbe 2:404-416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frieman, M., K. Ratia, R. E. Johnston, A. D. Mesecar, and R. S. Baric. 2009. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus papain-like protease ubiquitin-like domain and catalytic domain regulate antagonism of IRF3 and NF-kappaB signaling. J. Virol. 83:6689-6705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodkin, M. L., A. T. Ting, and J. A. Blaho. 2003. NF-kappaB is required for apoptosis prevention during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 77:7261-7280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haller, O., and F. Weber. 2007. Pathogenic viruses: smart manipulators of the interferon system. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 316:315-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han, J., M. S. Rutherford, and K. S. Faaberg. 2009. The porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus nsp2 cysteine protease domain possesses both trans- and cis-cleavage activities. J. Virol. 83:9449-9463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayashi, N., M. Welschof, M. Zewe, M. Braunagel, S. Dübel, F. Breitling, and M. Little. 1994. Simultaneous mutagenesis of antibody CDR regions by overlap extension and PCR. Biotechniques 17:310, 312, 314-315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopp, T. P., and K. R. Woods. 1981. Prediction of protein antigenic determinants from amino acid sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 78:3824-3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeda, F., C. M. Hecker, A. Rozenknop, R. D. Nordmeier, V. Rogov, K. Hofmann, S. Akira, V. Dotsch, and I. Dikic. 2007. Involvement of the ubiquitin-like domain of TBK1/IKK-i kinases in regulation of IFN-inducible genes. EMBO J. 26:3451-3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson, C. R., W. Yu, and M. P. Murtaugh. 2007. Cross-reactive antibody responses to nsp1 and nsp2 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 88:1184-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, S., and S. B. Kleiboeker. 2005. Porcine arterivirus activates the NF-kB pathway through IkB degradation. Virology 342:47-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li, Q., and I. M. Verma. 2002. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2:725-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May, M. J., and S. Ghosh. 1998. Signal transduction through NF-kappa B. Immunol. Today 19:80-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.May, M. J., S. E. Larsen, J. H. Shim, L. A. Madge, and S. Ghosh. 2004. A novel ubiquitin-like domain in IkappaB kinase beta is required for functional activity of the kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 279:45528-45539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meier, W. A., J. Galeota, F. A. Osorio, R. J. Husmann, W. M. Schnitzlein, and F. A. Zuckermann. 2003. Gradual development of the interferon-gamma response of swine to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection or vaccination. Virology 309:18-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meier, W. A., R. J. Husmann, W. M. Schnitzlein, F. A. Osorio, J. K. Lunney, and F. A. Zuckermann. 2004. The use of cytokines and synthetic double-stranded RNA to augment the T helper 1 immune response of swine to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 102:299-314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mi, J., Z. Y. Li, S. Ni, D. Steinwaerder, and A. Lieber. 2001. Induced apoptosis supports spread of adenovirus vectors in tumors. Hum. Gene Ther. 12:1343-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muñoz-Jordan, J. L., G. G. Sánchez-Burgos, M. Laurent-Rolle, and A. García-Sastre. 2003. Inhibition of interferon signaling by dengue virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:14333-14338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murtaugh, M. P., Z. Xiao, and F. Zuckermann. 2002. Immunological responses of swine to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection. Viral Immunol. 15:533-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelsen, C. J., M. P. Murtaugh, and K. S. Faaberg. 1999. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus comparison: divergent evolution on two continents. J. Virol. 73:270-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson, E. A., J. Christopher-Hennings, G. Wensvoort, J. E. Collins, and D. A. Benfield. 1993. Differentiation of United States and European isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus using monoclonal antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:3184-3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Neumann, E. 2005. Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome on swine production in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 227:385-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oleksiewicz, M. B., A. Botner, P. Toft, P. Normann, and T. Storgaard. 2001. Epitope mapping porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by phage display: the nsp2 fragment of the replicase polyprotein contains a cluster of B-cell epitopes. J. Virol. 75:3277-3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Overend, C., R. Mitchell, D. He, G. Rompato, M. J. Grubman, and A. E. Garmendia. 2007. Recombinant swine beta interferon protects swine alveolar macrophages and MARC-145 cells from infection with porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J. Gen. Virol. 88:925-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pedersen, K. W., Y. van der Meer, N. Roos, and E. J. Snijder. 1999. Open reading frame 1a-encoded subunits of the arterivirus replicase induce endoplasmic reticulum-derived double-membrane vesicles which carry the viral replication complex. J. Virol. 73:2016-2026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Powell, P. P., L. K. Dixon, and R. M. Parkhouse. 1996. An IkappaB homolog encoded by African swine fever virus provides a novel mechanism for downregulation of proinflammatory cytokine responses in host macrophages. J. Virol. 70:8527-8533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramaswamy, M., L. Shi, S. M. Varga, S. Barik, S. Behlke, and D. C. Look. 2006. Respiratory syncytial virus nonstructural protein 2 specifically inhibits type I interferon signal transduction. Virology 344:328-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Randall, R. E., and S. Goodbourn. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signaling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ropp, S. L., C. E. Mahlum Wees, Y. Fang, E. A. Nelson, K. D. Rossow, M. Bien, B. Arndt, S. Preszler, P. Steen, J. Christopher-Hennings, J. E. Collins, D. A. Benfield, and K. S. Faaberg. 2004. Characterization of emerging European-like PRRSV isolates in the United States. J. Virol. 78:3684-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rowland, R. R. R., T. S. Kim, B. Robinson, J. Stefanick, L. Guanghua, S. R. Lawson, and D. A. Benfield. 2001. Inhibition of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus by interferon-gamma and recovery of virus replication with 2 aminopurine. Arch. Virol. 146:539-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Royaee, A. R., R. Husmann, H. D. Dawson, G. Calzada-Nova, W. M. Schnitzlein, F. Zuckermann, and J. K. Lunney. 2004. Deciphering the involvement of innate immune factors in the development of the host responses to PRRSV vaccination. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 102:199-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Samuel, C. E. 2001. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:778-809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santoro, M. G., A. Rossi, and C. Amici. 2003. NF-kappB and virus infection: who controls whom. EMBO J. 22:2552-2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Snijder, E. J., and J. J. Meulenberg. 1998. The molecular biology of arteriviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 79:961-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Snijder, E. J., A. L. M. Wassenaar, W. J. Spaan, and A. E. Gorbalenya. 1995. The arterivirus Nsp2 protease. An unusual cysteine protease with primary structure similarities to both papain-like and chymotrypsin-like proteases. J. Biol. Chem. 270:16671-16676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Snijder, E. J., A. L. M. Wassenaar, and W. J. Spaan. 1994. Proteolytic processing of the replicase ORF1a protein of equine arteritis virus. J. Virol. 68:5755-5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solórzano, A., R. J. Webby, K. M. Lager, B. H. Janke, A. García-Sastre, and J. A. Richt. 2005. Mutations in the NS1 protein of swine influenza virus impair anti-interferon activity and confer attenuation in pigs. J. Virol. 79:7535-7543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strayhorn, W. D., and B. E. Wadzinski. 2002. A novel in vitro assay for deubiquitination of Ikappa B alpha. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 400(1):76-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun, Z., C. Zhen, X. Zhou, and Y. Fang. 2009. Analysis of mutations in ovarian tumor domain (OTU) of PRRSV nonstructural protein 2. Abstr. 90th Annu. Meet. Conf. Res. Work. Anim. Dis., abstr. 107, 6 to 8 December 2009, Chicago, IL.

- 53.Talon, J., M. Salvatore, R. E. O'Neill, Y. Nakaya, H. Zheng, T. Muster, A. Garcia-Sastre, and P. Palese. 2000. Influenza A and B viruses expressing altered NS1 proteins: a vaccine approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:4309-4314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Treier, M., L. M. Staszewski, and D. Bohmann. 1994. Ubiquitin-dependent c-Jun degradation in vivo is mediated by the delta domain. Cell 78:787-798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Valarcher, J. F., J. Furze, J. Wyld, J. Cook, K. K. Conzelmann, and J. Taylor. 2003. Role of alpha/beta interferons in the attenuation and immunogenicity of recombinant bovine respiratory syncytial viruses lacking NS proteins. J. Virol. 77:8426-8439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Aken, D., J. C. Zevenhoven-Dobbe, A. E. Gorbalenya, and E. J. Snijder. 2006. Proteolytic maturation of replicase polyprotein pp1a by the nsp4 main proteinase is essential for equine arteritis virus replication and includes internal cleavage of nsp7. J. Gen. Virol. 87:3473-3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Dinten, L. C., A. L. Wassenaar, A. E. Gorbalenya, W. J. Spaan, and E. J. Snijder. 1996. Processing of the equine arteritis virus replicase ORF1b protein: identification of cleavage products containing the putative viral polymerase and helicase domains. J. Virol. 70:6625-6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang, X., M. Li, H. Zheng, T. Muster, P. Palese, A. A. Beg, and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2000. Influenza A virus NS1 protein prevents activation of NF-kappaB and induction of alpha/beta interferon. J. Virol. 74:11566-11573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Waris, G., A. Livolsi, V. Imbert, J. F. Peyron, and A. Siddiqui. 2003. Hepatitis C virus NS5A and subgenomic replicon activate NF-kappaB via tyrosine phosphorylation of IkappaBalpha and its degradation by calpain protease. J. Biol. Chem. 278:40778-40787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wassenaar, A. L., W. J. Spaan, A. E. Gorbalenya, and E. J. Snijder. 1997. Alternative proteolytic processing of the arterivirus replicase ORF1a polyprotein: evidence that Nsp2 acts as a cofactor for the Nsp4 serine protease. J. Virol. 71:9313-9322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu, W. H., Y. Fang, R. Farwell, M. Steffen-Bien, R. R. Rowland, J. Christopher-Hennings, and E. A. Nelson. 2001. A 10-kDa structural protein of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus encoded by ORF 2b. Virology 287:183-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yonemitsu, Y., and Y. Kaneda. 1999. Hemagglutinating virus of Japanliposome mediated gene delivery to vascular cells, p. 295-306. In A. H. Baker (ed.). Molecular biology of vascular diseases. Methods in molecular medicine. Humana Press, Clifton, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Yoneyama, M., W. Suhara, Y. Fukuhara, M. Sato, K. Ozato, and T. Fujita. 1996. Autocrine amplification of type I interferon gene expression mediated by interferon stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3). J. Biochem. 120:160-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeman, D., R. Neiger, M. Yaeger, E. Nelson, D. Benfield, P. Leslie-Steen, J. Thomson, D. Miskimins, R. Daly, and M. Minehart. 1993. Laboratory investigation of PRRS virus infection in three swine herds. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 5:522-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng, D., G. Chen, B. Guo, G. Cheng, and H. Tang. 2008. PLP2, a potent deubiquitinase from murine hepatitis virus, strongly inhibits cellular type I interferon production. Cell Res. 18:1105-1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ziebuhr, J., E. J. Snijder, and A. E. Gorbalenya. 2000. Virus-encoded proteinases and proteolytic processing in the Nidovirales. J. Gen. Virol. 81:853-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]