Abstract

Dickeya dadantii is a pectinolytic phytopathogen enterobacterium that causes soft rot disease on a wide range of plant species. The virulence of D. dadantii involves several factors, including the osmoregulated periplasmic glucans (OPGs) that are general constituents of the envelope of proteobacteria. In addition to the loss of virulence, opg-negative mutants display a pleiotropic phenotype, including decreased motility and increased exopolysaccharide synthesis. A nitrosoguanidine-induced mutagenesis was performed on the opgG strain, and restoration of motility was used as a screen. The phenotype of the opg mutant echoes that of the Rcs system: high level activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay is needed to activate exopolysaccharide synthesis and to repress motility, while low level activation is required for virulence in enterobacteria. Here, we show that mutations in the RcsCDB phosphorelay system restored virulence and motility in a D. dadantii opg-negative strain, indicating a relationship between the Rcs phosphorelay and OPGs.

Osmoregulated periplasmic glucans (OPGs) are general periplasmic constituents of the envelope of most proteobacteria. Their common features are that glucose is the sole constituent sugar, and their abundance in the periplasm increases as the osmolarity of the medium decreases. In Enterobacteriaceae and related bacteria, the glucose backbone synthesis is catalyzed by both products of the opgGH operon (5). Studies of several bacterial pathogens, including Dickeya dadantii, showed the importance of OPGs for virulence (4, 5, 18, 25, 26).

Dickeya dadantii is a member of the pectinolytic erwiniae causing soft rot disease in a wide range of plant species (33). The virulence of D. dadantii is associated with the synthesis and the secretion of a set of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes (pectinases, cellulases, and proteases) causing maceration of the plant tissues (22). D. dadantii synthesize OPGs containing 5 to 12 glucose units joined by β,1-2 linkages and branched by β,1-6 linkages that are substituted with succinyl and acetyl residues (11). The opgG or opgH mutants unable to synthesize OPGs show a pleiotropic phenotype. They are nonvirulent on chicory leaves and potato tubers, and synthesis and secretion of pectate-lyases, cellulases, and proteases are reduced (32). Motility is severely reduced, while exopolysaccharide secretion is increased (mucoid phenotype) (32). Data suggest that the opg mutants are impaired in perception of the environment, which prevents D. dadantii from recognizing host cells, suggesting a possible dysfunction of phosphorelay signaling pathways, major systems required for environmental perception in bacteria (6). In these systems, upon stimuli, a kinase/phosphatase sensor autophosphorylates and transfers the phosphate group to a cytoplasmic regulator which modulates expression of target genes.

Here, we show that mutations in the rcsC and rcsB genes, encoding, respectively, the sensor and the cognate regulator of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay, suppress several phenotypes of an opgG mutant, including the nonvirulent phenotype on potato tubers. This suggests interactions between the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay and OPG molecules and constitutes a first hint at the molecular role of these ubiquitous glycans in virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and growth conditions.

D. dadantii and Escherichia coli strains are listed in Table 1 . Bacteria were grown at 30°C (D. dadantii) or 37°C (E. coli) in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) or in minimal medium M63 supplemented with a carbon source at a concentration of 2 g/liter (29). Solid media were obtained by adding agar at 15 g/liter. When low-osmolarity medium was required, LB without NaCl was used. Motility was tested on LB agar plates containing 4 g/liter agar. The solid media used to test the pectinases, cellulases, and proteases activities have been described previously (32).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Strain | Relevant description/genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| D. dadantii strains | ||

| EC3937 | Wild type | Laboratory collection |

| NFB3500 | EC3937 opgG::uidA Kanr | Laboratory collection |

| NFB3591 | NFB3500 rcsC2 | This study |

| NFB3602 | EC3937 opgG::Cmlrura | Laboratory collection |

| NFB3609 | NFB3602 rcsC2 | This study |

| NFB3611 | EC3937 rcsC2 | This study |

| NFB3682 | EC3937 rcsC::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB3683 | NFB3500 rcsC::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB3753 | EC3937 Δ(rcsCBD)::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB3754 | NFB3500 Δ(rcsCBD)::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB3800 | EC3937 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3805 | NFB3602 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3806 | NFB3609 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3807 | NFB3611 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3808 | NFB3753 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3809 | EC3937 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3810 | NFB3602 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3811 | NFB3609 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3812 | NFB3611 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3813 | NFB3753 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB3859 | NFB3811 (mini-Tn5Spe rcsCBD) | This study |

| NFB3946 | EC3937 opgG::FRT | Laboratory collection |

| NFB3948 | NFB3810 (mini-Tn5Spe rcsC2BD) | This study |

| NFB3983 | NFB3946 Δ(rcsCBD)::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB3991 | NFB3500 (mini-Tn5Spe rcsCBD) | This study |

| NFB7007 | NFB3983 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7107 | NFB3983 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7127 | NFB3682 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7128 | NFB3682 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7154 | NFB3946 rcsC::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7191 | NFB7154 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7192 | NFB7154 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7199 | EC3937 rcsB::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7200 | EC3937 rcsC2 rcsB::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7202 | NFB7199 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7203 | NFB7200 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7205 | NFB7199 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7206 | NFB7200 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7208 | NFB3946 rcsB:Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7209 | NFB3946 rcsC2 rcsB::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7210 | NFB3500 rcsB::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7211 | NFB3500 rcsC2 rcsB::Cmlr | This study |

| NFB7212 | NFB7208 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7213 | NFB7208 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7214 | NFB7209 (mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| NFB7215 | NFB7209 (mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| E. coli strains | ||

| JM83 | F′ ara Δ(lac-proAB) rpsL (φ80d1acZΔM15) | 40 |

| S17-1λpir | recA thi pro hsdR λpir RP4-2-Tet::Mu- Kan::Tn7 Tmpr Strr | 30 |

Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: ampicillin and kanamycin (Kan) at 50 μg/ml (E. coli) or 25 μg/ml (D. dadantii), chloramphenicol and tetracycline at 25 μg/ml (E. coli) or 12.5 μg/ml (D. dadantii), and spectinomycin at 100 μg/ml (E. coli) or 50 μg/ml (D. dadantii). X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) and X-GlcA (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucuronide) were used at a concentration of 40 μg/ml.

Recombinant DNA techniques.

Standard procedures were performed for genomic and plasmid DNA extractions (36). DNA purification was performed with Nucleospin Extract II (Macherey-Nagel). Restriction enzymes (Biolabs), T4 DNA ligase (Biolabs), Taq polymerase (Eppendorf), and the large fragment of DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment; Invitrogen) were used according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Construction of the mutations.

Plasmids and primers designed for PCR are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. The chloramphenicol cassette used for gene inactivation was released from pNFCml after digestion by EcoRV. The rcsCBD locus was cloned by shotgun. The D. dadantii 3937 chromosomal DNA was digested by SacI and XbaI, and fragments from 6 kb to 8 kb were isolated by agarose gel electrophoresis, purified, and cloned into pUC18Not digested by the same restriction enzymes (21). Plasmids extracted from mucoid colonies were analyzed by restriction. The NotI fragment from pNFW257, containing the rcsCBD locus, was subcloned into pUTmini-Tn5Spe (13) digested by NotI. The resulting plasmid (pNFW261) was introduced into D. dadantii cells by conjugation.

TABLE 2.

Plasmids

| Plasmids | Genotype and/or phenotypea | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| pUC18 | Ampr | 40 |

| pUC18Not | Ampr | 21 |

| pB21 | pSUP102::Tn5-B21 Tetr | 37 |

| pNFCml | Cmlr | Laboratory collection |

| pUIDK11 | CmlruidA-Kanr | 3 |

| pOK1 | sacB oriR6K Sper | 23 |

| pCP20 | Rep(Ts) flp+ Ampr Kanr | 9 |

| pUTmini-Tn5Kan | mini-Tn5Kan oriR6K Kanr Ampr | 13 |

| pUTmini-Tn5Spe | mini-Tn5Spe oriR6K Sper Ampr | 13 |

| pNFW190 | pKO1 opgG::Kanr | This study |

| pNFw198 | pKO1 opgG::FRT | This study |

| pNFW138 | pUC18 rcsC | This study |

| pNFW149 | pUC18 rcsC::Cmlr | This study |

| pNFW161 | pOK1 rcsC::Cmlr | This study |

| pNFW170 | pUC18 ′gyrA ΔrcsCBD menF′ | This study |

| pNFW171 | pUC18 ′gyrA ΔrcsCBD::CmlrmenF′ | This study |

| pNFW181 | pUC18Not flhD′ | This study |

| pNFW203 | pUC18Not flhD-uidA-Kanr | This study |

| pNFW204 | pUC18Not flhD-uidA | This study |

| pNFW215 | pUT(mini-Tn5Kan flhD-uidA) | This study |

| pNFW182 | pUC18Not ftsA′ | This study |

| pNFW193 | pUC18Not ftsA-uidA-Kanr | This study |

| pNFW201 | pUC18Not ftsA-uidA | This study |

| pNFW220 | pUT(mini-Tn5Kan ftsA-uidA) | This study |

| pNFW257 | pUC18Not rcsCBD | This study |

| pNFW261 | pUT(mini-Tn5Spe rcsCBD) | This study |

| pNFW336 | pUC18Not rcsC2BD | This study |

| pNFW339 | pUT(mini-Tn5Spe rcsC2BD) | This study |

| pNFW397 | pUC18Not rcsCB::CmlrrcsD | This study |

| pNFW398 | pUC18Not rcsC2B::CmlrrcsD | This study |

Cmlr, chloramphenicol resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Kanr, kanamycin resistance; Sper, spectinomycin resistance; Tetr, tetracycline resistance.

TABLE 3.

Primer sequences

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| rcs1 | AAGGTACCTTGCCGGAAGCGAGCCGCGGCGCTCGCGGT |

| rcs2 | AACCCGGGTCAAAGGCATACCGTAAAGGTTGTCAGCAA |

| rcs3 | AACCCGGGCGCAGGCATGAAATCAGGCTCCTGATGAAC |

| rcs4 | AAAAGCTTTACCCCGTAATAACCTGCTTACCCACCCGC |

| rcs5 | GCAATAGCCTCAGCCATTACCCGGA |

| rcs6 | CGTCTGACAAAGAGTAATGC |

| rcs7 | GCTGAACCGGTGGAAGACGATGAGCTCGACAGCGTG |

| rcs8 | CTGAAAGGTGTCTTTGCCATGCTGAATCTTCATCCC |

| flhD1 | CACTGCGGGGTAAGGATCCGTGAAATATTATG |

| flhD2 | GCATCGAGCTCGATGCGTCTGAGGTGCCGGCTCTTCA |

| ftsA1 | GATCGAGGATCCGCCCTGGATTAAACAGGCCAGCG |

| ftsA2 | CGGCATGAGCTCATTGCCGATGCGCTCAGCCGGC |

| Tn5-1 | CTAGGCGGCCAGATCTGATCAA |

| Tn5-2 | TCAAAAGGTCATCCACCGGATC |

| Tn5B21-1 | CATGGAAGTCAGATCCTGG |

| Tn5B21-2 | GTTCACTCCGTTCTCTTGC |

Restriction sites are underlined.

To clone the rcsC2BD locus, a fragment of the rcsC DNA encompassing the rcsC2 mutation was amplified by PCR (rcs5 and rcs6 primers) from the NFB3611 chromosomal DNA, digested by SspI and NheI, and cloned into pNFW257 digested by the same enzymes (pNFW336); the cloned sequence was sequenced. The SacI-AscI fragment of pNFW336 was cloned into pNFW261 digested by the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid (pNFW339) was introduced into D. dadantii cells by conjugation.

To inactivate rcsC, rcsC was amplified by PCR (rcs7 and rcs8 primers), digested by SacI and HindIII, and cloned into pUC18 cleaved by the same enzymes (pNFW138). The cloned DNA fragment was sequenced. A Cmlr cassette was inserted into pNFW138 digested by PshAI and SmaI (pNFW149). The SalI-HpaI fragment from pNFW149, containing the rcsC gene disrupted by the Cmlr cassette, was cloned into the pOK1 vector digested by SalI and SmaI. The resulting plasmid (pNFW161) was introduced into D. dadantii cells by conjugation.

The rcsB::Cmlr allele was obtained by the insertion of the Cmlr cassette into pNFW257 digested by HpaI. The resulting plasmid (pNFW397) was introduced in D. dadantii cells by electroporation.

The rcsC2 rcsB::Cmlr allele was obtained by the insertion of the Cmlr cassette into pNFW336 digested by HpaI. The resulting plasmid (pNFW398) was introduced in D. dadantii cells by electroporation.

To delete the rcsCBD locus, two DNA fragments (1 kb), located upstream and encompassing, for the first fragment, the beginning of the rcsC coding sequence (rcs1 and rcs2 primers) and encompassing, for the second fragment, the beginning of the rcsD coding sequence (rcs3 and rcs4 primers), were amplified by PCR. These fragments were digested by KpnI and SmaI and by SmaI and HindIII, respectively, and cloned into pUC18 cleaved by KpnI and HindIII (pNFW170). The cloned sequence was sequenced. The Cmlr cassette was inserted into pNFW170 digested by SmaI. The resulting plasmid, pNFW171, was introduced into D. dadantii cells by electroporation.

The opgG::FRT allele was obtained as described by Cherepanov and Wackernagel (9). An opgG::Kanr allele was inserted into the pOK1 plasmid (pNFW190). The Kanr cassette is flanked by two FLP recombination target (FRT) sites recognized by the Flp recombinase expressed by the pCP20 plasmid. This recombinase was used to obtain a Kans mutant opgG allele by removing the Kanr cassette. The resulting pOK1 plasmid harboring the opgG::FRT allele (pNFW198) was introduced into D. dadantii cells by conjugation.

Construction of the transcriptional fusions.

The uidA-Kanr cassette used for gene fusions was extracted from plasmid pUIDK11 (3). The flhD′ and ftsA′ DNA fragments were amplified by PCR (flhD1 and flhD2, and ftsA1 and ftsA2 primers, respectively). The flhD′ fragment was digested by BamHI and SacI and cloned into pUC18Not digested by the same enzymes (pNFW181). The SacI DNA fragment containing the uidA-Kanr cassette was inserted into pNFW181 digested by SacI (pNFW203). The ftsA′ DNA fragment was digested by BamHI and SacI and cloned into pUC18Not digested by the same enzymes (pNFW182). The SmaI DNA fragment containing the uidA-Kanr cassette was inserted into pNFW182 digested by NgoMIV and blunt ended with the Klenow enzyme (pNFW193).

The Kanr cassette was removed from pNFW203 (flhD′) and pNFW193 (ftsA′) by NcoI and HpaI digestion, blunt ended, and annealed (pNFW204 and pNFW201, respectively). The NotI fragments of these plasmids were subcloned into pUTmini-Tn5Kan (13) to give pNFW215 and pNFW220, respectively (Table 2), and introduced into D. dadantii by conjugation.

Transduction, conjugation, and transformation.

Transformation of E. coli cells was carried out by the rubidium chloride technique (29). Plasmids were introduced in D. dadantii by electroporation (36) or conjugation (30). The insertions were integrated into the D. dadantii chromosome by marker exchange recombination in the presence of the appropriate antibiotic after successive cultures in low-phosphate medium (35). Transduction with phage ΦEC2 was carried out according to the method of Resibois et al. (34).

Nitrosoguanidine and transposon mutagenesis.

N-methyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (nitrosoguanidine) mutagenesis was performed according to Adelberg et al. (1). Briefly, NFB3500 was grown in LB medium at 30°C to mid-log phase. One milliliter of culture was centrifuged, and the pellet was washed with TM buffer [50 mM Tris, 50 mM maleic acid, 8 mM MgSO4, 15 mM (NH4)2SO4, pH 6]. The washed bacterial pellet was resuspended in 1 ml TM buffer, nitrosoguanidine was added at a concentration of 100 μg/ml, and the suspension was incubated for 30 min at 30°C. The bacteria were then washed twice with TM buffer. The pellet was resuspended in 1 ml LB medium and divided into 10 independent aliquots of 0.1 ml. Each aliquot was diluted in 5 ml LB medium, grown overnight, and stored in 20% glycerol at −80°C. Nitrosoguanidine mutagenesis efficiency was estimated by the percentage of auxotroph mutant.

Transposon mutagenesis by Tn5-B21 or mini-Tn5 was performed by conjugation between the E. coli S17-1λpir harboring the suicide vector containing transposon and various D. dadantii EC3937 derivatives. Mutants were selected on minimal medium 63 plates containing sucrose as a unique carbon source (counterselection of the E. coli donor) and the appropriate antibiotic (13, 37).

Localization of transposon insertions and sequence data.

Transposon insertions were localized on the D. dadantii chromosome by inverse PCR using Tn5-1 and Tn5-2 primers (mini-Tn5 insertions) or Tn5B21-1 and Tn5B21-2 primers (Tn5-B21 insertions) after digestion of the chromosomal DNA with TaqI. The sequence and annotations of the D. dadantii chromosome (J. D. Glasner, C.-H. Yang, S. Reverchon, N. Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, G. Condemine, J.-P. Bohin, F. van Gijsegem, S. Yang, T. Franza, D. Expert, G. Plunkett, M. San Francisco, A. Charkowski, B. Py, L. Grandemange, K. Bell, L. Rauscher, P. Rodriguez-Palenzuela, A. Toussaint, M. Holeva, S.-Y. He, V. Douet, M. Boccara, C. Blanco, I. Toth, A. D. Anderson, B. Biehl, B. Mau, S. M. Flynn, F. Barras, M. Lindeberg, P. Birch, S. Tsuyumu, X. Shi, M. Hibbing, M.-N. Yap, U. Masahiro, J. F. Kim, P. Soni, G. F. Mayhew, D. Fouts, S. Gill, F. R. Blattner, N. T. Keen, and N. T. Perna, submitted for publication) are available at http://asap.ahabs.wisc.edu/asap/ASAP1.htm. Sequence accession numbers of the rcsC, rcsB, and rcsD genes are ABF-0017295, ABF-0017296, and ABF-0017297, respectively.

Determination of enzyme activities.

β-Glucuronidase assays were performed on crude extracts obtained from bacteria disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell at 1.4 107 Pa (20,000 lb/in2) as previously described (12). β-Glucuronidase activity was determined by monitoring spectrometrically at 410 nm the hydrolysis of PNPU (4-nitrophenyl-β-d-glucuronide).

The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard (7).

OPG analysis.

Measurement of OPG synthesis in D. dadantii was performed as previously described (32).

Pathogenicity test.

Chicory leaves were inoculated as previously described (12). Bacteria from an overnight culture in LB medium were recovered by centrifugation and diluted in M63 medium. Leaves were slightly wounded in their center with a sterile razor blade and infected using 107 bacteria per inoculation site. After incubation in a dew chamber for 48 h at 30°C, the length of rotted tissue was measured to estimate the disease severity. Potatoes tubers were inoculated as previously described (24). Sterile pipette tips containing a bacterial suspension of 107 or 108 bacteria in 5 μl were inserted into the tuber parenchyma. After 72 h at 30°C, tubers were sliced vertically through the inoculation point and the weight of decayed tissues was measured. Each measure was repeated in three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Screening and characterization of the rcsC2 mutation.

Nitrosoguanidine-induced mutations were isolated from the opgG strain NFB3500. Mutagenized bacteria were screened for motility by spotting 106 bacteria on soft agar plates. The swarm diameter obtained for the opgG mutagenized strain was higher than the swarm diameter observed for the opgG strain. Bacteria from the periphery circumference of the halo were purified and screened for motility. Motile clones were tested for mucoidy and virulence on chicory leaves and potato tubers. None of the tested clones were virulent on chicory leaves, but two of them were virulent on potato tubers (Fig. 1) and display a nonmucoid phenotype. One of the suppressive mutations (NFB3591) was further studied because these two clones were isolated from the same mutagenesis pool.

FIG. 1.

Pathogenicity of the wild-type (EC3937) strain and the opgG (NFB3500), opgG rcsC2 (NFB3591), and rcsC2 (NFB3611) mutant strains of D. dadantii on potato tubers and chicory leaves. (A) Bacteria (107) of the wild-type strain (EC3937) (spot 1), the opgG strain (NFB3500) (spot 2), the opgG rcsC2 strain (NFB3591) (spot 3), and the rcsC2 strain (NFB3611) (spot 4) were inoculated into holes on potato tubers. Disease symptoms were observed after 72 h of incubation at 30°C. (B) Bacteria (107) of the wild-type strain (EC3937) (spot 1), the opgG strain (NFB3500) (spot 2), the opgG rcsC2 strain (NFB3591) (spot 3), and the rcsC2 strain (NFB3611) (spot 4) were inoculated into scarified chicory leaves. Disease symptoms were observed after 48 h of incubation at 30°C.

Random transposon mutagenesis with Tn5-B21 (Tetr) was performed on wild-type strain EC3937 and used to map the suppressive mutation. Transposon insertions were then introduced into the suppressor strain (NFB3591) by generalized transduction using the ΦEC2 phage, and the resulting Tetr colonies were screened for mucoidy and motility. One insertion of Tn5-B21, located in the gene ABF-0020432, was 24% cotransducible with the mucoid and the nonmotile phenotypes. The distance between the Tn5 insertion and the suppressive mutation is about 20 kb according to the equation of Wu (39). The distance, the phenotypes observed, and the isolation of a null mutation in the rcsC gene abolishing the mucoid phenotype of an opgH null mutation in E. coli (15), suggest that the suppressor mutation lies within the rcsCBD locus. DNA sequencing revealed a unique C/T transition located in the rscC gene. This mutation, named rcsC2, led to an alanine-to-valine substitution at position 463. This A463V substitution is located in the cytoplasmic linker domain of the protein RcsC (in the vicinity of phosphorylatable H479) between the second transmembrane domain and the histidine kinase domain (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). RcsC is the transmembrane sensor component of the RcsCD-RcsB signaling pathways phosphorylating the RcsB regulator via the intermediate RcsD protein (27). These data suggest that a modification of RcsCD-RcsB signaling suppresses opg mutation phenotypes.

Decreased activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay signaling pathway restores motility and the nonmucoid aspect in the opgG strain.

To test this hypothesis, null rcsC, rcsB, and ΔrcsCBD mutations were introduced in the opgG mutant strain. Motility, mucoid aspect, plant cell-degrading enzyme activity, and virulence of the double mutants were evaluated. The nonmucoid aspect of colonies was restored in the opgG rcsC, opgG rcsB, and the opgG ΔrcsCDB double mutant strains (Table 4). Motility was determined on swarming plates. Restoration of motility occurred in all the opgG rcs mutant strains compared to the opgG strain (Table 4), while motility levels were similar for the wild-type and the various rcs strains (Table 4). These data suggest that loss of activation of RcsCD-RcsB signaling suppresses the opg mutation phenotype.

TABLE 4.

Phenotypes observed in various opg and rcs mutant strains compared to the wild-type straina

| Main strain or genotype (strain name) | Motility | Pectinase activity | Cellulase activity | Protease activity | Mucoidy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type (EC3937) | 2.6 | 2.5 | 1.6 | + | − |

| opgG (NFB3500) | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1 | − | + |

| rcsC2 (NFB3611) | 2.6 | 2.7 | 1.8 | + | − |

| opgG rcsC2 (NFB3591) | 2.4 | 2.4 | 1.8 | + | − |

| rcsC (NFB3682) | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.4 | + | − |

| opgG rcsC (NFB3683) | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.8 | + | − |

| ΔrcsCBD (NFB3753) | 2.8 | 2.5 | 1.7 | + | − |

| opgG ΔrcsCBD (NFB3754) | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.8 | + | − |

| rcsB (NFB7199) | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.7 | + | − |

| opgG rcsB (NFB7210) | 1.6 | 2.3 | 1.5 | + | − |

| rcsB rcsC2 (NFB7200) | 2.9 | 2.9 | 1.8 | + | − |

| opgG rcsB rcsC2 (NFB7211) | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.6 | + | − |

For motility, the swarm diameters are expressed in cm. Exoenzyme activities: for pectinase activity, the halo diameters of substrate degradation are expressed in cm; for cellulase activity, the halo diameters of substrate degradation are expressed in cm; for protease activity, + or − indicates presence or absence of halo of degradation. For mucoidy, − indicates a nonmucoid phenotype, while + indicates a mucoid phenotype.

Decreased activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay signaling pathway is required for restoration of virulence in the opgG strain.

Secretion of plant cell wall-degrading enzymes is required for full virulence of D. dadantii. Global pectinase, cellulase, and protease activities were estimated on plates. The halo diameters of degraded substrates indicated that the global exoenzyme activities were restored in the opgG rcsC2, opgG rcsC, opgG rcsB, and opgG ΔrcsCBD double mutant strains compared to the opgG single mutant strain, while activities observed for the corresponding single rcs mutant strains remained unaffected compared to the wild-type strain (Table 4). Thus, in D. dadantii, activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay represses exoenzyme synthesis, as observed with Pectobacterium carotovorum (2).

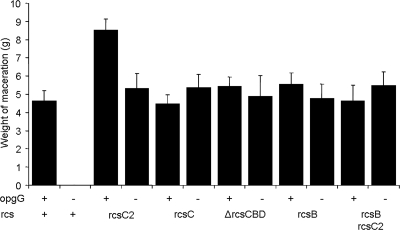

Virulence of the opgG rcsC2, opgG rcsC, opgG rcsB, and opgG ΔrcsCBD double mutant strains was assessed by measuring the severity of the disease on potato tubers and on chicory leaves. Virulence was restored in potato tubers for all the double mutant strains compared to the opgG single mutant strain. The weights of macerated tissues were similar for the wild-type and for all the double mutant strains (Fig. 2). On chicory leaves, no restoration of virulence was observed for any of the double mutant strains (data not shown). In contrast, for the rcsC, rcsB, and ΔrcsCBD single mutant strains, virulence levels were similar to those observed for the wild-type strain for both potato tubers (Fig. 2) and chicory leaves (data not shown). A slight but reproducible increase of the disease severity was observed for the rcsC2 strain (Fig. 1 and 2). This increase depends on the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay since the maceration observed with the rcsB rcsC2 double mutant was reduced to the level observed for the rcsB single mutant strain (Fig. 2). These data demonstrate that the restoration of virulence in the opgG strain is the result of decreased activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay.

FIG. 2.

Weight of maceration on potato tubers for various opgG and rcs mutant strains of D. dadantii measured. Bacteria (107) were inoculated into holes on potato tubers. Maceration (g) was weighed after 72 h of incubation at 30°C.

Absence of OPGs induces the Rcs regulon.

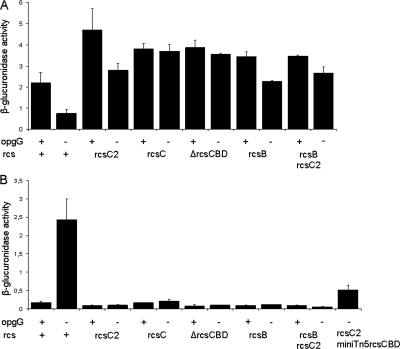

The RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay regulates motility by negatively regulating the flhDC master operon (19, 20). The flhD and flhC genes encode regulators activating expression of the flagellar apparatus genes. An flhD-uidA transcriptional fusion was constructed and introduced in the various opgG and rcs single and double mutant strains, and its expression was evaluated. In the four strains harboring the different rcs alleles (the rcsC2, rcsC, rcsB, and ΔrcsCDB mutants), expression of the flhD-uidA fusion that was 2-fold higher than that of the wild-type strain was observed (Fig. 3A), indicating that the expression of flhDC is repressed by activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay in D. dadantii. In the opgG rcsC2, opgG rcsC, opgG rcsB, and opgG ΔrcsCBD double mutant strains, expression of the flhD-uidA fusion that was 3- to 4-fold higher than that of the opgG strain was observed (Fig. 3A). Repression of the flhDC operon was severely diminished in the opgG strains harboring the rcs mutations. To analyze the regulation of other genes of the Rcs regulon in the absence of OPGs, an ftsA-uidA transcriptional fusion was constructed and introduced in the various opgG and rcs single and double mutant strains, and its expression was evaluated. The ftsAZ operon, needed for cell division, is activated by the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay (8). The ftsAZ operon is transcribed by several promoters, one of them, activated by the RcsB regulator, was cloned in the ftsA-uidA fusion. In the four strains harboring the different rcs alleles inactivating the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay, a low-level expression of the ftsA-uidA fusion in the different rcs strains was observed (Fig. 3B), indicating that the ftsAZ operon is positively regulated by activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay in D. dadantii. The ftsA-uidA expression of the opgG strain was 13- to 14-fold higher than in the opgG rcsC2, opgG rcsC, opgG rcsB, and opgG ΔrcsCBD double mutant strains (Fig. 3B). Thus, activation was diminished in the opgG strains harboring the different rcs mutations. These results indicate an increased activation level of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay in the opgG mutant strain. Thus, OPGs regulate genes under the control of the Rcs phosphorelay system.

FIG. 3.

Expression of the flhD-uidA (A) or the ftsA-uidA (B) gene fusions in various opg and rcs mutant strains of D. dadantii. Bacteria were grown in LB without NaCl at 30°C until mid-log phase and broken by passing through a French press cell, and β-glucuronidase activity was measured with PNPU as a substrate (see Materials and Methods). Results reported are the average of 3 independent experiments. Specific activity is expressed as the change in optical density at 410 nm (ΔOD410) per min and per mg of protein.

The rcsC2 allele is dominant over the wild-type allele of rcsC.

The simplest explanation for the observed phenotype of the rcsC2 allele is that this mutant gene encodes a mutant protein decreasing the kinase activity or increasing the phosphatase activity of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay. These two possibilities could be distinguished genetically by phenotypic analysis of a merodiploid strain harboring both the wild-type rcsC allele and the rcsC2 one. If the kinase activity is decreased, the rcsC2 mutation will be recessive, and if the phosphatase activity is increased, the rcsC2 mutation will be, at least in part, dominant. The rcsCBD locus, cloned into a minitransposon Tn5, was introduced in the opgG rcsC2 double mutant strain. Two merodiploid clones, isolated from independent transposon mutagenesis, were tested, and both present similar phenotypes. Motility of the merodiploid strain (NFB3859) was restored, but the halo diameter was 25% lower than that in the parental opgG rcsC2 strain (NFB3811). The expression of the ftsA-uidA fusion in the NFB3859 strain showed an intermediate level between the NFB3810 (opgG) and the NFB3811 (opgG rcsC2) strains (Fig. 3B). Maceration occurred in 15/30 and in 10/10 potato tubers inoculated with, respectively, 107 and 108 bacteria of the merodiploid strain. Similar results were observed when the rcsC2 mutation was located on the transposon. A merodiploid for the wild-type rcsCBD locus in an opgG strain displayed nonvirulent and mucoid phenotypes. Taken together, these results indicate that wild-type rcsC and rcsC2 alleles are codominant and suggest that the rcsC2 mutation increases the phosphatase activity of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay. However, the rcsC null mutation and the rcsC2 mutation display similar phenotypes because both of them lower RcsB phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we characterized a suppressor of the Opg phenotype in D. dadantii lying within the rcsC gene. The RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay was first identified in E. coli as a positive regulator of exopolysaccharide synthesis (27). Further studies demonstrated the role of this phosphorelay in regulation of motility, cell division, and virulence in various enterobacterial species, such as E. coli, Salmonella enterica, and P. carotovorum (2, 8, 19, 20, 28, 31). In D. dadantii, this phosphorelay also controls these cellular processes.

Restoration of virulence in the opgG rcs double mutant strains occurs only on potato tubers, despite the restoration of essential virulence factors, such as motility and exoenzyme secretion. Infection of chicory leaves by D. dadantii is a more demanding process than infection of potato tubers. Absence of restoration of virulence in chicory leaves may be explained in part by a more efficient defense host response in chicory leaves than in potato tubers. In addition, absence of restoration of virulence in chicory leaves may be explained by an inappropriate expression of additional bacterial virulence genes needed for infection in chicory leaves remaining in strains devoid of OPGs. This suggests that this wide-host-range phytopathogenic bacterium requires expression of different sets of genes to achieve virulence, depending on the colonized host.

The rcsC2 mutation is dominant and results in constitutive, low-level activation of the phosphorelay compatible with constitutive phosphatase activity of RcsC2. This is in agreement with the low level of RcsCD-RcsB activation needed for full virulence in S. enterica (14, 20, 31) and with the restoration of virulence in D. dadantii for opgG strains harboring the null mutation rcsC or rcsB. Three dominant mutations were isolated in the barA gene encoding the sensor protein of the BarA-UvrY phosphorelay system of E. coli. Like the rcsC2 mutation, these mutations lie within the linker domain of BarA located just upstream of the histidine kinase domain and harbor constitutive phosphatase activity (38). Constitutive kinase activity-dominant mutations were isolated in the same region of the rcsC gene of S. enterica (20). These mutations suggest that this domain is important for sensor proteins to finely tune the phosphorylated level of regulators.

Isolation of the suppressor of the Opg phenotype found in the envZ-ompR locus in E. coli (17) or in the pigX gene in Serratia sp., encoding a cyclic dimeric GMP phosphodiesterase (18), the alteration of the proteome in an opgG mutant strain (6), and the fact that the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay is specific to enterobacteria (16, 27) could not be explained only by inaccurate expression of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay-regulated genes. Expression of additional genes, whose expression is independent of this phosphorelay, may be affected in opg mutant strains. The requirement of several phosphorelay systems and the requirement of periplasmic glucans in virulence are now well established (5). The relationship between OPGs and the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay was shown for the regulation of colanic acid capsular polysaccharide synthesis in E. coli (15), but to our knowledge, this is the first study connecting these glucans and a phosphorelay system with virulence.

The constitutive activation of the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay could be the result of the alteration of envelope integrity in opg strains (6, 10, 32). This hypothesis cannot be excluded, but in this case, it is surprising that in the various rcs opgG double mutant strains virulence is restored and that no additional deleterious phenotypes are associated with this mutant strain. The relationship between OPGs and the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay may be direct or indirect and remains to be elucidated. One of the stimuli activating the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay is an upshift in osmolarity (15, 41). These are physiological conditions under which the OPG level is low, since OPG levels decrease as the medium osmolarity increases (5). Thus, one can imagine that variation of the OPG level in the periplasm modulates the RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay activation. This modulation could occur indirectly via the IgaA protein, an attenuator of RcsCD-RcsB phosphorelay activation (14), since an igaA mutant and an opgG mutant display similar phenotypes. This hypothesis will be further investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guy Lippens and Florent Sebbane for carefully reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale et de la Recherche.

We acknowledge members of the International Erwinia Consortium for the exchange of unpublished data concerning the D. dadantii 3937 genome sequence.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 23 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adelberg, E. A., M. Mandel, and G. Chein Ching Chen. 1965. Optimal conditions for mutagenesis by N-methyl-N′-nitroso-N-nitrosoguanidine in Escherichia coli K12. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 18:788-795. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andresen, L., V. Koiv, T. Alamae, and A. Mae. 2007. The Rcs phosphorelay modulates the expression of plant cell wall degrading enzymes and virulence in Pectobacterium carotovorum ssp. carotovorum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 273:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardonnet, N., and C. Blanco. 1992. ′uidA-antibiotic-resistance cassettes for insertion mutagenesis, gene fusions and genetic constructions. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 72:243-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhagwat, A. A., W. Jun, L. Liu, P. Kannan, M. Dharne, B. Pheh, B. D. Tall, M. H. Kothary, K. C. Gross, S. Angle, J. Meng, and A. Smith. 2009. Osmoregulated periplasmic glucans of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium are required for optimal virulence in mice. Microbiology 155:229-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohin, J.-P., and J.-M. Lacroix. 2007. Osmoregulation in the periplasm, p. 325-341. In M. Ehrmann (ed.), The periplasm. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 6.Bouchart, F., A. Delangle, J. Lemoine, J.-P. Bohin, and J.-M. Lacroix. 2007. Proteomic analysis of a non virulent mutant of the phytopathogenic bacterium Erwinia chrysanthemi deficient in osmoregulated periplasmic glucans: change in protein expression is not restricted to the envelope, but affects general metabolism. Microbiology 153:760-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carballès, F., C. Bertrand, J.-P. Bouché, and K. Cam. 1999. Regulation of Escherichia coli cell division genes ftsA and ftsZ by the two-component system rcsC-rcsB. Mol. Microbiol. 34:442-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherepanov, P. P., and W. Wackernagel. 1995. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 158:9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clavel, T., J.-C. Lazzaroni, A. Vianney, and R. Portalier. 1996. Expression of the tolQRA genes of Escherichia coli K12 is controlled by the RcsC sensor protein involved in capsule synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 19:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cogez, V., P. Talaga, J. Lemoine, and J.-P. Bohin. 2001. Osmoregulated periplasmic glucans of Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Bacteriol. 183:3127-3133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delangle, A., A.-F. Prouvost, V. Cogez, J.-P. Bohin, J.-M. Lacroix, and N. Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat. 2007. Characterization of the Erwinia chrysanthemi gan locus, involved in galactan catabolism. J. Bacteriol. 189:7053-7061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lorenzo, V., M. Herrero, U. Jakubzik, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6568-6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dominguez-Bernal, G., M. G. Pucciarelli, F. Ramos-Morales, M. Garcia-Quintallina, D. A. Cano, J. Casadesus, and F. Garcia del Portillo. 2004. Repression of the RcsC-YojN-RcsB phosphorelay by the IgaA protein is a requisite for Salmonella virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 53:1437-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ebel, W., G. J. Vaughn, H. K. Peters III, and J. E. Trempy. 1997. Inactivation of mdoH leads to increased expression of colanic acid capsular polysaccharide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6858-6861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson, K. D., and C. S. Detweiler. 2006. The Rcs phosphorelay system is specific to enteric pathogens/commensals and activates ydeI, a gene important for persistent Salmonella infection of mice. Mol. Microbiol. 62:883-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fiedler, W., and H. Roterings. 1988. Properties of Escherichia coli mutants lacking membrane-derived oligosaccharides. J. Biol. Chem. 263:14684-14689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fineran, P. C., N. R. Williamson, K. S. Lilley, and G. P. C. Salmond. 2007. Virulence and prodigiosin antibiotic biosynthesis in Serratia are regulated pleiotropically by the GGDEF/EAL domain protein, PigX. J. Bacteriol. 189:7653-7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Francez-Charlot, A., B. Laugel, A. Van Gemert, N. Dubarry, F. Wiorowski, M. P. Castanié-Cornet, C. Gutierrez, and K. Cam. 2003. RcsCDB His-Asp phosphorelay system negatively regulates the flhDC operon in Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 49:823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.García-Calderon, C. B., M. García-Quintanilla, J. Casadesus, and F. Ramos-Morales. 2005. Virulence attenuation in Salmonella enterica rcsC mutants with constitutive activation of the Rcs system. Microbiology 151:579-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero, M., V. De Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, N., G. Condemine, W. Nasser, and S. Reverchon. 1996. Regulation of pectinolysis in Erwinia chrysanthemi. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 50:213-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huguet, E., K. Hahn, K. Wengelnik, and U. Bonas. 1998. hpaA mutants of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria are affected in pathogenicity but retain the ability to induce host-specific hypersensitive reaction. Mol. Microbiol. 29:1379-1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lojkowska, E., C. Masclaux, M. Boccara, J. Robert-Baudouy, and N. Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat. 1995. Characterization of the pelL gene encoding a novel pectate lyase of Erwinia chrysanthemi 3937. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1183-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loubens, I., L. Debarbieux, A. Bohin, J.-M. Lacroix, and J.-P. Bohin. 1993. Homology between a genetic locus (mdoA) involved in the osmoregulated biosynthesis of periplasmic glucans in Escherichia coli and a genetic locus (hrpM) controlling pathogenicity of Pseudomonas syringae. Mol. Microbiol. 10:329-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahajan-Miklos, S., M.-W. Tan, L. G. Rahme, and F. M. Ausubel. 1999. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell 96:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Majdalani, N., and S. Gottesman. 2005. The Rcs phosphorelay: a complex signal transduction system. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59:379-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mariscotti, J. F., and F. García-del Portillo. 2009. Genome expression analyses revealing the modulation of the Salmonella Rcs regulon by the attenuator IgaA. J. Bacteriol. 191:1855-1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, J. H. 1992. A short course in bacterial genetics: a laboratory manual and handbook for Escherichia coli and related bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Miller, V. L., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1988. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 170:2575-2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mouslim, C., M. Delgado, and E. A. Groisman. 2004. Activation of the RcsC/YojN/RcsB phosphorelay system attenuates Salmonella virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 54:386-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page, F., S. Altabe, N. Hugouvieux-Cotte-Pattat, J.-M. Lacroix, J. Robert-Baudouy, and J.-P. Bohin. 2001. Osmoregulated periplasmic glucan synthesis is required for Erwinia chrysanthemi pathogenicity. J. Bacteriol. 183:3134-3141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perombelon, M., and A. Kelman. 1980. Ecology of the soft rot Erwinia. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 18:361-387. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Resibois, A., M. Colet, M. Faelen, T. Schoonejans, and A. Toussaint. 1984. Phi-EC2, a new generalized transducing phage of Erwinia chrysanthemi. Virology 137:102-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roeder, D. L., and A. Collmer. 1985. Marker-exchange mutagenesis of a pectate lyase isozyme gene in Erwinia chrysanthemi. J. Bacteriol. 164:51-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook, J. E., F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 37.Simon, R., J. Quandt, and W. Klipp. 1989. New derivatives of transposon Tn5 suitable for mobilization of replicons, generation of operons fusions and induction of genes in Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 80:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomenius, H., A.-K. Pernestig, C. F. Mendez-Catala, D. Georgellis, S. Normark, and O. Melefors. 2005. Genetic and functional characterization of the Escherichia coli BarA-UvrY two-component system: point mutations in the HAMP linker of the BarA sensor give a dominant-negative phenotype. J. Bacteriol. 187:7317-7324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, T. T. 1966. A model for a three point analysis of random general transduction. Genetics 54:405-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mpl8 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou, L., X. H. Lei, B. R. Bochner, and B. L. Wanner. 2003. Phenotype microarray analysis of Escherichia coli K-12 mutants with deletions of all two-component systems. J. Bacteriol. 185:4956-4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]