Abstract

Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 possesses two putative ABC-type inorganic phosphate (Pi) transporters with three associated Pi-binding proteins (PBPs), SphX (encoded by sll0679), PstS1 (encoded by sll0680), and PstS2 (encoded by slr1247), organized in two spatially discrete gene clusters, pst1 and pst2. We used a combination of mutagenesis, gene expression, and radiotracer uptake analyses to functionally characterize the role of these PBPs and associated gene clusters. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) demonstrated that pstS1 was expressed at a high level in Pi-replete conditions compared to sphX or pstS2. However, a Pi stress shift increased expression of pstS2 318-fold after 48 h, compared to 43-fold for pstS1 and 37-fold for sphX. A shift to high-light conditions caused a transient increase of all PBPs, whereas N stress primarily increased expression of sphX. Interposon mutagenesis of each PBP demonstrated that disruption of pstS1 alone caused constitutive expression of pho regulon genes, implicating PstS1 as a major component of the Pi sensing machinery. The pstS1 mutant was also transformation incompetent. 32Pi radiotracer uptake experiments using pst1 and pst2 deletion mutants showed that Pst1 acts as a low-affinity, high-velocity transporter (Ks, 3.7 ± 0.7 μM; Vmax, 31.18 ± 3.96 fmol cell−1 min−1) and Pst2 acts as a high-affinity, low-velocity system (Ks, 0.07 ± 0.01 μM; Vmax, 0.88 ± 0.11 fmol cell−1 min−1). These Pi ABC transporters thus exhibit differences in both kinetic and regulatory properties, the former trait potentially dramatically increasing the dynamic range of Pi transport into the cell, which has potential implications for our understanding of the ecological success of this key microbial group.

Phosphorus input into aquatic systems is largely in the form of poorly soluble, eroded mineral phosphate, which enters these systems via runoff from land, making Pi a key growth-limiting nutrient, particularly in freshwater environments (13, 23, 41). A recent survey of 34 inland lakes from three (physiographic) regions of Canada (25) revealed total Pi concentrations ranging between 0.058 and 7.64 μM. Thus, organisms occupying such environments invariably need to make key biochemical and regulatory adaptations to their Pi uptake system in order to sustain growth. One such group is the cyanobacteria, one of the largest, most diverse, and most widely distributed prokaryotic lineages (42). Their ability to acclimate to a varying-light environment as well as their ability to acquire nutrients present at low ambient concentrations has led to their present-day dominance in vast tracts of oligotrophic open ocean waters (40) and in freshwater systems (14).

Studies of bacterial Pi acquisition have largely focused on model organisms such as Escherichia coli (52) and Bacillus subtilis (26). In E. coli, uptake utilizes both a low-affinity permease, the Pit system (54) [with uptake of Pi being reliant on cotransport with divalent metal cations such as Mg(II) or Ca(II) through the formation of a soluble, neutral metal-phosphate complex, which is then the transported species (28, 49)] and a high-affinity Pst transport system (52). The Pst transporter comprises a periplasmic Pi-binding protein (PstS), two integral membrane proteins (PstA and PstC), and an ATP-binding protein (PstB) (10, 44). Regulation of this complex is dependent on a two-component system encoded by the phoBR operon (31). In addition, the Pst system itself seems to play a role in regulation, with mutations in genes of the pst operon leading to constitutive expression of the pho regulon (52). Thus, the periplasmic PstS, which binds Pi with high affinity, could potentially act as the primary sensor of external Pi. Once loaded with Pi, PstS interacts with membrane components of the Pst system, causing a conformational change which is sensed by the PhoU protein, not involved in Pi transport (51). However, increased activity of the Pit transporters PitA and PitB can alleviate constitutive expression of the pho regulon and restore Pi regulation of the regulon (24).

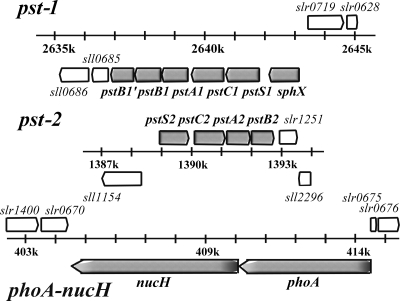

In the freshwater cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (herein, Synechocystis), while orthologs of the PhoB/R two-component system have been identified and the system has been shown to be exclusively responsible for the specific Pi limitation response (45), there are several features of the Pi acquisition system which are unusual and warrant further investigation. Firstly, Synechocystis, like several other freshwater strains (43) and most marine picocyanobacteria (40), contains no identifiable Pit transporter. In contrast, there are two gene clusters encoding potential ABC transporters for Pi (Fig. 1), which we designate here pst1 and pst2, with three associated Pi-binding proteins (PBPs) (2, 32). sll0540, which encodes a fourth PBP, has also been identified in the Synechocystis genome, but its PBP is not colocalized with either pst1 or pst2. Indeed, pho regulon predictions of several cyanobacterial genomes showed that 50% of freshwater strains contain “duplicate” pst transporters (43), while many freshwater and marine strains contain multiple associated PBPs (40, 43). However, despite clear evidence of multiple Pi transport elements in cyanobacteria, little is known of the functional significance of individual, and apparently redundant, components of the cyanobacterial pho regulon.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the two ABC Pi transporters and the phoA-nucH gene clusters.

Here, we assessed the role of multiple Pi transporter elements in Synechocystis by creating both mutants with complete deletions of the pst1 and pst2 gene clusters and single interposon mutants with mutations of the associated pstS and sphX genes. We generated gene expression profiles using quantitative PCR (qPCR) to analyze both wild-type (WT) and specific interposon mutants, under Pi-replete, Pi stress, and nitrate (N) stress conditions, as well as following a shift to high light. We show that disruption of pstS1 (sll0680) leads to constitutive pho regulon gene expression consistent with PstS1 as a primary component of the Pi sensor. Such a phenotype is not observed in the pstS2 (slr1247) and sphX (sll0679) mutants. Moreover, using radiotracer incorporation studies with pst gene cluster deletion mutants, we show that while both systems transport Pi, there are dramatic differences in their maximum uptake rates (Vmax) and half-saturation constants (Ks) for Pi. These data demonstrate a novel strategy for Pi acquisition in a freshwater cyanobacterium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture growth conditions.

Axenic cultures of Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 WT and mutant strains were grown in BG-11 medium (38) at 30°C with shaking under continuous white light illumination (30 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Synechocystis mutants were maintained in liquid BG-11 medium containing the appropriate antibiotic as follows: 50 μg ml−1 spectinomycin, 50 μg ml−1 apramycin, or 2.5 μg ml−1 gentamicin. For the Pi-free and N-free BG-11 media, K2HPO4·3H2O and nitrate, respectively, were replaced by an equimolar amount of KCl. For the RNA work, cyanobacterial cultures (3 liters) were grown in BG-11 medium supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium hydrogen carbonate, stirred continuously, and bubbled with air. In order for Pi stress conditions to be established in each time course, a 3-liter preculture was grown to an optical density at 750 nm (OD750) of 0.5. The culture was then pelleted via centrifugation at 4,754 × g for 10 min and resuspended in 200 ml of Pi-free BG-11 medium. This washing process was repeated three times in order to remove any excess phosphate from the medium. The culture was then transferred into 3 liters of Pi-free BG-11 medium to give an OD750 of 0.3, and this was recorded as time point 0. Synechocystis cell samples were taken for RNA extraction, alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity measurement, and cell counts by using flow cytometry at various time points up to 48 h. During the shift to high light, in which cells were exposed to 600 μmol photons m−2 s−1 for a 24-h period, an OD750 of 0.08 was used in order to prevent self-shading of the culture during the time course. For 32Pi radiotracer uptake, cells were grown in 100 ml BG-11 medium to an OD750 of 0.3, prior to the establishment of Pi stress conditions as described above. The culture was then left to shake for 48 h to allow recovery from centrifugation and to induce maximal gene expression in response to Pi stress. Cultures were then diluted to an OD750 of 0.08 in Pi-free BG-11 medium, and 32Pi radiotracer uptake was assessed.

Phylogenetic and bioinformatic analyses.

All sequences used for the analyses were extracted from GenBank (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov; accession numbers are shown in Table 1). The presence of a signal peptide cleavage site in the native protein chain was predicted by three algorithms: neural network, hidden Markov model (using the SignalP 3.0 server [http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/]), and SigCleave from the EMBOSS suite (http://emboss.sourceforge.net/). The molecular weights and isoelectric points of PBPs were determined for the mature sequence, i.e., after removal of the predicted signal peptide by using the Pepstats program from EMBOSS. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted from an alignment of the amino acid sequences of the mature PstS and SphX from marine and freshwater cyanobacteria by using ClustalX v1.83 (47). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm and rooted on the PstS sequence of Escherichia coli. Bootstrap values were obtained through 1,000 repetitions.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of PstS and SphX Pi-binding protein properties in freshwater and marine cyanobacteria

| Protein and gi no. | Organisma | Lengthb | SigPc | Mol wtd | pIe | Open reading frame |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Freshwater and marine cyanobacterial PstS | ||||||

| 16331543 | SynechocystisPCC 6803 (PstS1) | 383 | 28 (1) | 37,030 | 4.08 | sll0680 |

| 86604859 | Synechococcus OS-A | 349 | 23 (2) | 35,095 | 4.28 | |

| 86610205 | Synechococcus OS-B′ | 366 | 25 (3) | 36,610 | 4.32 | |

| 86606387 | Synechococcus OS-A | 353 | 25 (3) | 35,566 | 4.43 | |

| 86609371 | Synechococcus OS-B′ | 353 | 25 (3) | 35,767 | 4.61 | |

| 87123371 | Synechococcus RS9917 | 337 | 28 (2) | 32,142 | 4.88 | RS9917_05910 |

| 33867037 | Synechococcus WH8102 | 336 | 32 (2) | 31,880 | 4.9 | SYNW2507 |

| 17232067 | Anabaena PCC 7120 | 392 | 30 (3) | 38,083 | 5.02 | all4575 |

| 37521603 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 349 | 33 (2) | 33,594 | 6.06 | gll2034 |

| 87124682 | Synechococcus RS9917 | 340 | 24 (3) | 33,327 | 6.79 | RS9917_00632 |

| 26110901 | Escherichia coli | 346 | 25 (3) | 34,408 | 7.46 | |

| 86608555 | Synechococcus OS-B′ | 358 | 35 (2) | 34,955 | 8.67 | |

| 86606216 | Synechococcus OS-A | 359 | 28 (2) | 35,923 | 9.31 | |

| 37520014 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 347 | 31 (3) | 33,983 | 9.44 | glr0445 |

| 33866347 | Synechococcus WH8102 | 325 | 25 (3) | 31,479 | 9.65 | SYNW1815 |

| 33241024 | Prochlorococcus SS120 | 329 | 17 (1) | 32,785 | 10.12 | Pro1575 |

| 33240982 | Prochlorococcus SS120 | 330 | 17 (2) | 32,636 | 10.27 | Pro1533 |

| 33861267 | Prochlorococcus MED4 | 323 | 24 (3) | 31,530 | 10.37 | PMM0710 |

| 16330429 | SynechocystisPCC 6803 (PstS2) | 333 | 28 (3) | 32,527 | 10.46 | slr1247 |

| 33865552 | Synechococcus WH8102 | 324 | 24 (3) | 31,475 | 10.54 | SYNW1018 |

| 17228406 | Anabaena PCC 7120 | 347 | 33 (3) | 33,965 | 10.6 | all0911 |

| 87124221 | Synechococcus RS9917 | 326 | 24 (3) | 31,278 | 10.72 | RS9917_11445 |

| Freshwater and marine cyanobacterial SphX | ||||||

| 16331544 | SynechocystisPCC 6803 (SphX) | 328 | 27 (1) | 33,002 | 4.26 | sll0679 |

| 16331706 | SynechocystisPCC 6803 | 307 | 22 (2) | 30,385 | 4.54 | sll0540 |

| 87124691 | Synechococcus RS9917 | 347 | 29 (2) | 35,298 | 5.12 | RS9917_00677 |

| 37519584 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 338 | 23 (2) | 34,559 | 7.48 | glr0015 |

| 37519581 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 337 | 22 (2) | 34,576 | 7.6 | glr0012 |

| 37519583 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 335 | 22 (1) | 33,751 | 8.13 | glr0014 |

| 37519577 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 340 | 32 (3) | 33,563 | 8.84 | glr0008 |

| 17228589 | Anabaena PCC 7120 | 352 | 24 (1) | 35,978 | 9.02 | alr1094 |

| 17232077 | Anabaena PCC 7120 | 309 | None (3) | 33,403 | 9.09 | alr4585 |

| 86609984 | Synechococcus OS-B′ | 335 | 27 (1) | 32,849 | 9.51 | |

| 37519582 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 343 | 26 (3) | 34,701 | 9.6 | glr0013 |

| 86605896 | Synechococcus OS-A | 337 | 35 (1) | 33,033 | 9.69 | |

| 33865820 | Synechococcus WH8102 | 345 | 29 (2) | 35,349 | 9.89 | SYNW1286 |

| 37520552 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 384 | 79 (1) | 32,273 | 10.09 | glr0983 |

| 87124426 | Synechococcus RS9917 | 355 | 32 (3) | 36,068 | 10.38 | RS9917_12470 |

| 37519585 | Gloeobacter PCC 7421 | 387 | 84 (1) | 32,686 | 10.55 | glr0016 |

Synechocystis data are in bold.

Length of the native protein (number of amino acid residues).

Signal peptide cleavage site as predicted in silico. The number in parentheses is the number of algorithms, out of three used, predicting this site.

Molecular weight of the mature polypeptide.

Isoelectric point of the mature polypeptide.

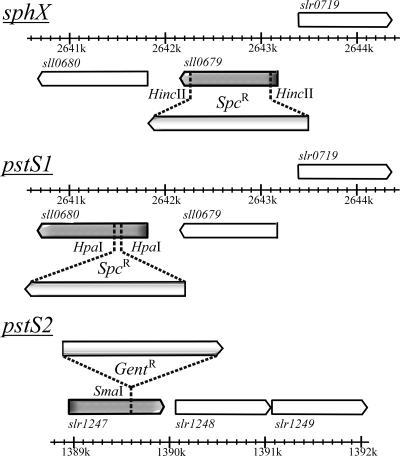

Single-gene disruption mutants.

Synechocystis sll0679 (sphX), sll0680 (pstS1), and slr1247 (pstS2) mutants were constructed by interposon mutagenesis by using specific antibiotic resistance cassettes. Primers designed to target the flanking regions of the genes were sphXexF (5′-GCGCCTTCAGCCTGGACTGT-3′), sphXexR (5′-CTGGCCACGGCCACGATCAA-3′), pstS1exF (5′-AAGCCGTCAGAGTTTGTTTG-3′), pstS1exR (5′-TTCCCGCACATTTTGAGGTA-3′), pstS2exF (5′-CGACCAATTACTTGCCGGCT-3′), and pstS2exR (5′-CGGGCATCGGTAAAAACCAC-3′). PCR was performed as follows: an initial denaturation at 98°C for 2 min was followed by 25 cycles of 95°C for 45 s, 45°C for 45 s, and 68°C for 3 min, followed by a final extension of 68°C for 5 min. Each 50-μl PCR mix contained 1 μM primers, 100 ng Synechocystis genomic DNA, 1× Promega PCR master mix reaction buffer. sphX and pstS1 PCR products were then ligated into pCR2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen, United States), resulting in constructs pLH0679 (sphX) and pLH0680 (pstS1), and the pstS2 product was ligated into LITMUS 38i vector (NEB), giving pLH1247lit38 (pstS2). pLH0679 and pLH0680 were digested with HincII and HpaI, respectively. This removed 824-bp and 108-bp internal fragments of the sphX and pstS1 genes, respectively. A spectinomycin resistance cassette derived from pHP45Ω, flanked by short inverted repeats containing transcription and translation termination signals (37) on a SmaI fragment was subsequently inserted into the remaining unique HincII (pLH0679) or HpaI site (pLH0680) (Fig. 2), producing plasmids pLH0679Ω and pLH0680Ω, respectively. A gentamicin resistance cassette derived from pDAH346 (courtesy of D. Hodgson; see also reference 35) was inserted into pLH1247 at the unique SmaI site (Fig. 2), producing plasmid pLH1247lit38GN. Constructs were sequenced to confirm the integrity of the flanking DNA cloned and the orientation of the antibiotic cassette. Transformation of WT Synechocystis with these plasmid constructs was performed as described by Williams (53); see Table 2 for a full list of strains generated.

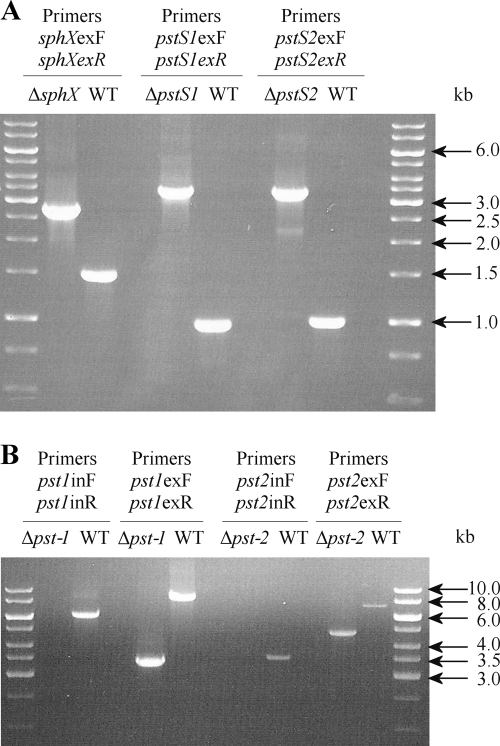

FIG. 2.

Insertional mutagenesis of Synechocystis sphX, pstS1, and pstS2. Spc, spectinomycin; Gent, gentamicin.

TABLE 2.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | Wild-type strain | 38 |

| Synechocystis 0679mut | Synechocystis mutant containing a spectinomycin resistance cassette inserted into sll0679 in the same orientation as the ORF | This work |

| Synechocystis 0680mut | Synechocystis mutant containing a spectinomycin resistance cassette inserted into sll0680 in the same orientation as the ORF | This work |

| Synechocystis 1247mut | Synechocystis mutant containing a gentamicin resistance cassette inserted into slr1247 in the same orientation as the ORF | This work |

| Synechocystis Δpst1 | Synechocystis mutant containing an apramycin resistance cassette replacing the pst1 gene cluster (sll0679, sll0680, sll0681, sll0682, sll0683, and sll0684) in the same orientation as the ORF | This work |

| Synechocystis Δpst2 | Synechocystis mutant containing an apramycin resistance cassette replacing the pst2 gene cluster (slr1247, slr1248, slr1249, and slr1250) in the same orientation as the ORF | This work |

ORF, open reading frame.

Whole-gene-cluster deletion mutants.

The Δpst1 and Δpst2 in-frame, whole-gene-cluster deletion mutants were constructed using λ Red-mediated recombination (22). The pst1 and pst2 gene clusters were amplified by PCR using primers pst1exF (5′-GCGGGTCCAAACCGACTAAC-3′), pst1exR (5′-CGGCAATAGGGCGAGGATAC-3′), pst2exF (5′-TTTCCTCTTCGCCTTCTTGG-3′), and pst2exR (5′-CTTGCAGGGCAATAAACTCC-3′) and the following PCR conditions: an initial denaturation step at 95°C for 2 min, followed by 25 cycles of 98°C for 20 s, 45°C for 15 s, and 68°C for 4 min, followed by a final extension of 68°C for 5 min. Each 50-μl PCR mix contained 0.3 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 0.3 μM primers, 100 ng Synechocystis genomic DNA, 1 U KAPAHiFi DNA polymerase, and 1× KAPAHiFi reaction buffer. PCR products were then ligated into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, United States), producing constructs pITTpst1 and pITTpst2. These plasmids were then electroporated into E. coli BW25113 containing the λ Red recombination plasmid plJ790 (15). For each gene cluster disruption, PCR primers were then designed to specifically amplify the apramycin resistance cassette from plasmid plJ773 (22). Each primer contains at the 5′ end 39 bp matching the Synechocystis chromosomal DNA sequence directly adjacent to the cluster to be inactivated. For the forward primer, the last 3 bp of the 39 bp corresponds to the start codon of the first gene of the cluster, and for the reverse primer, the stop codon for the last gene of the cluster. The remaining 19 bp of the primer corresponds to the 5′ or 3′ end of the apramycin disruption cassette. The PCR primers used for amplification of the apramycin resistance cassette to be inserted into pst1 were pst1redF (5′-AAAGCTACCGTCAACGGCTAATCACAATCGACCACCCTGGGGGCGGAGAAGTAAAAATGATTCCGGGGATCCGTC GACC-3′) and pst1redR (5′-RCTTTTGGATTTATTTAATTTCACCAACTTGATTTAATTAGTTAATTGACAGTTAATTATGTAGGCTGGAGCTG CTTC-3′). For amplification of the apramycin resistance cassette to be inserted into pst2, the primers were pst2redF (5′-TCAGCGAACAAGGGCTGACTGTTTCAACTGCACTACAATTTAGATTGCAAATTCCTATGATTCCG GGGATCCGTCGACC-3′) and pst2redR (5′-TAAGAGGTAATACAAGCAAACGTTATATGAAGGAGGGCACCATAAACAGGAGTATCTATGTAGGCTGGAGCTGCTTC-3′) (the start and stop codons are highlighted in bold, and the sequence corresponding to the antibiotic resistance cassette is underlined). Each 50-μl PCR mix contained 0.3 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM primers, 100 ng pIJ773, 5% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 2 U KAPAHiFi DNA polymerase, and 1× KAPAHiFi reaction buffer. PCR conditions were as follows: 94°C for 2 min, followed by 94°C for 45 s, 50°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 90 s repeated for 10 cycles, followed by 94°C for 45 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 90 s repeated for 15 cycles, followed by a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were transformed into E. coli BW25113 grown in LB containing 10 mM arabinose. Subsequent constructs were sequenced to confirm the correct in-frame insertion of the antibiotic resistance cassette before transformation into Synechocystis. Synechocystis transformants were selected in BG-11 solid medium supplemented with apramycin (50 μg ml−1). Apramycin-resistant transformants were then grown in liquid BG-11 medium supplemented with 50 μg ml−1 apramycin.

Genomic DNA extraction.

Extraction of Synechocystis genomic DNA from WT and mutant strains was carried out by using a method modified from Murray and Thompson (34) as described by Eguchi et al. (17) and by using 20 to 30 ml of early-logarithmic-phase culture.

Confirmation of mutant segregation.

To test whether Synechocystis mutant strains were completely segregated, i.e., homogeneous for the mutant chromosomes, PCR amplification with genomic DNA from the mutants as templates and the corresponding primers was carried out. For the whole-gene-cluster deletion mutants, the following PCR primers were designed to amplify an internal region of pst1 or pst2 in order to confirm complete loss of the WT region: pst1inF (5′-GCCTGTACACCATCCCAGAC-3′), pst1inR (5′-TCCCGAGTCGATTCCTTGAG-3′), pst2inF (5′-CTCCGTAGTCAGCGTTATCG-3′), and pst2inR (5′-AACTGACCGATACGGCTTTC-3′).

Flow cytometry.

Samples for flow cytometry were fixed in 0.2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde (grade II; Sigma) and stored at 4°C until analysis. Synechocystis cell abundance was determined in triplicate using a FACScan flow cytometer and CellQuest version 3.3 software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA).

AP assay.

Alkaline phosphatase (AP) activity was measured with the para-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) assay (5), modified for use in a microplate reader (33).

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis.

RNA was extracted from Synechocystis by using a “hot-phenol” method (3) as modified by Scanlan et al. (39). Contaminating DNA was removed by treating samples with 8 U Turbo DNase (Ambion), and samples were further purified by passage through an RNeasy Mini column (Qiagen). mRNA quality was assessed by visual inspection using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), and samples passed if they achieved an RNA integrity number (RIN) of >7.8. Quantification of mRNA used a NanoDrop ND-1000 UV-visible light spectrophotometer. cDNA synthesis was carried out using TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (ABI) following the manufacturer's guidelines. Each 100 μl of reaction mix contained 800 ng of total RNA, to which final concentrations of 2.5 μM random hexamers, 500 μM each dNTP, and 6.0 mM MgCl2 were added. MultiScribe reverse transcriptase (3 U), RNase inhibitor (0.4 U), and 10 μl of 10× MultiScribe reverse transcriptase buffer were also added. Amplification of cDNA was carried out for 10 min at 25°C, 60 min at 42°C, and 5 min at 95°C in a Biometra T-gradient PCR thermal cycler.

Quantitative PCR using SYBR green.

A single-well qPCR assay was used to quantify the expression of specific genes throughout each time course by using SYBR green as the reporting system. PCR primers were designed for cDNAs derived from transcripts of various putatively Pi-regulated genes as well as the housekeeping gene rnpB (Table 3). The qPCRs were performed using AmpliTaq Gold SYBR green universal PCR master mix (ABI) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. Each reaction was performed in a 25-μl volume in a MicroAmp Optical 96-well reaction plate with optical adhesive films for a cover. Each reaction volume contained 8 ng cDNA, 5 μM specific primer, and 1× AmpliTaq Gold SYBR green master mix. Reaction volumes were heated at 95°C for 10 min and then underwent 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 62°C for 1 min, carried out on a model 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Each reaction was performed in triplicate for each gene at every time point sampled, allowing the mean threshold cycle (CT) value to be calculated (11). CT values were converted to gene copy number per ng of template cDNA in a 4-stage process, which involved the modification of the standard 2−ΔΔCT equation (4) as described by Clokie et al. (11). For the 2−ΔΔCT equation to be valid, the efficiency of amplification for each target gene and calibrator must be approximately equal to the efficiency of the reference amplification. To ensure that this was the case, the ΔCT value was plotted for a range of cDNA template dilutions (from 10 to 0.3 ng) against log input cDNA concentration for each primer (data not shown). For each primer tested, the value of the regression (ΔCT versus cDNA concentration) was less than 0.1, indicating approximately equal amplification efficiencies.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative PCR oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Gene name (open reading frame) | Primer name | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| sphX (sll0679) | 0679 F | TCGAAGAGCTAAAGCGCATTT | 61 |

| 0679 R | TGGTTCCAGCGGGTCAAG | ||

| pstS1 (sll0680) | 0680 F | GCCATGGACGACGAAGAGA | 62 |

| 0680 R | GCGGTCATGGGAAGCATT | ||

| pstC1 (sll0681) | 0681 F | CCGGTGGGAAACCATTTTTC | 65 |

| 0681 R | ATAATCCCCCCGACAATGC | ||

| pstS2 (slr1247) | 1247 F | AGCGGCAACGGTTAAGCA | 67 |

| 1247 R | GTTACGGCGGGCAAAGGT | ||

| pstC2 (slr1248) | 1248 F | CTGGTGGCGGGATTGGT | 64 |

| 1248 R | ATGTCCCGGCTGATGGAA | ||

| phoA (sll0654) | 0654 F | GAATTTGATGTCCGAATCCAAAA | 65 |

| 0654 R | GGCCCAGTGGAATCAATAACA | ||

| nucH (sll0656) | 0656 F | GCTACTTCAGAAGGGATTTTCATCTT | 71 |

| 0656 R | ACCTTGTCGCCAACGTTAACA | ||

| rnpB (slr1469) | 1469 F | GCGCACCAGCAGTATCGA | 62 |

| 1469 R | CCTCCGACCTTGCTTCCAA |

Pi radiotracer uptake.

Pi uptake was initiated by the addition of 100 μl of a specific concentration of Pi containing tracer levels of K2H[32P]O4 to 20 ml Pi-stressed culture (see above) containing approximately 7.5 × 107 cells ml−1. Uptake was stopped by filtering 500 μl of cells through a 0.2-μm Minisart disposable filter (Sartorius). Samples were taken at 6 s, 12 s, 20 s, 30 s, 1 min, 5 min, and 10 min. Filtrate (200 μl) was then added to 4 ml of scintillant material (Ultima Gold; PerkinElmer) and mixed, and the outer surfaces of the vials were wiped with methanol impregnated tissue to remove any static charge prior to loading into the scintillation counter (Packard-Bell, United States). Total counts were recorded over 5 min (cpm) with a computerized correction factor applied. 32Pi incorporation was calculated from the decrease in 32Pi in the external medium at a range of Pi concentrations, 10 to 0.75 μM for the “high-range” uptake experiments and 250 to 15.6 nM for the “low-range” uptake experiments. To account for nonspecific adsorption, killed-cell controls (i.e., following the addition of 10 mM HgCl2) were analyzed at each time point and Pi concentration, and any counts measured were subtracted from experimental samples. Pi uptake rates were normalized to cell abundance as determined by flow cytometry (see above). Kinetic parameters (Vmax and Ks) were determined using the iterative rectangular hyperbolic curve-fitting procedure in Sigma Plot 8.0. The Ks and Vmax values presented in the text are the means of three independent experiments.

RESULTS

Synechocystis Pi-binding proteins.

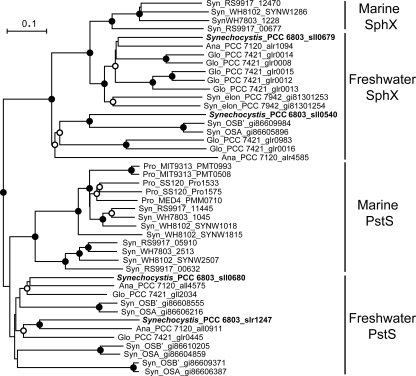

The complete genome sequence of Synechocystis contains three potential PBP genes adjacent to associated ABC transporter components, namely, sll0679 (encoding SphX), sll0680 (encoding PstS1), and slr1247 (encoding PstS2) (Fig. 1). In addition, sll0540 encodes a fourth potential PBP that can also be identified by BLAST analysis, but it is flanked on the genome by genes encoding hypothetical proteins and is unlinked to an ATP transporter. Each putative PBP contains all/some of the key residues known to be critical for Pi binding in E. coli (30; data not shown). The PBPs have similar predicted molecular masses of 30 to 33 kDa, except PstS1, which is somewhat larger (37 kDa). In addition, three of the four PBPs have similar predicted isoelectric points (pIs) of 4 to 4.5, except PstS2, which has a predicted pI of 10.46. These ranges in predicted molecular masses and pIs essentially encompass the entire ranges in sizes and pIs of PBPs encoded in completed cyanobacterial genomes (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis of PBPs demonstrated a clear separation of PBPs into either the archetypal PstS type or the SphX type (Fig. 3), the latter encompassing sll0679 and sll0540 proteins.

FIG. 3.

Neighbor-joining tree based on the amino acid sequences of the mature PstS and SphX from marine and freshwater cyanobacteria. Synechocystis sequences are marked in bold. Syn, Synechococcus; elon, elongatus; Ana, Anabaena; Gloeobacter; Pro, Prochlorococcus. The tree was constructed from an alignment by using ClustalX v1.83. The bootstrap values were obtained through 1,000 repetitions, • indicates a value of >95%, and ○ indicates a value of >50%. The tree is rooted on the PstS sequence of Escherichia coli. The scale bar represents 0.1 substitutions per amino acid.

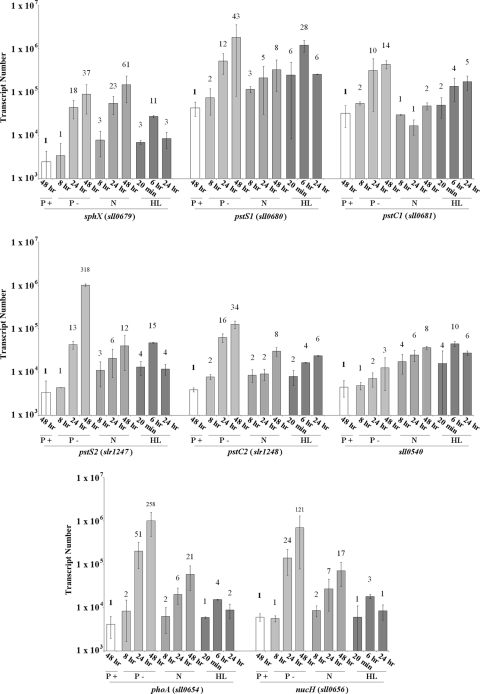

PBP gene expression during Pi stress.

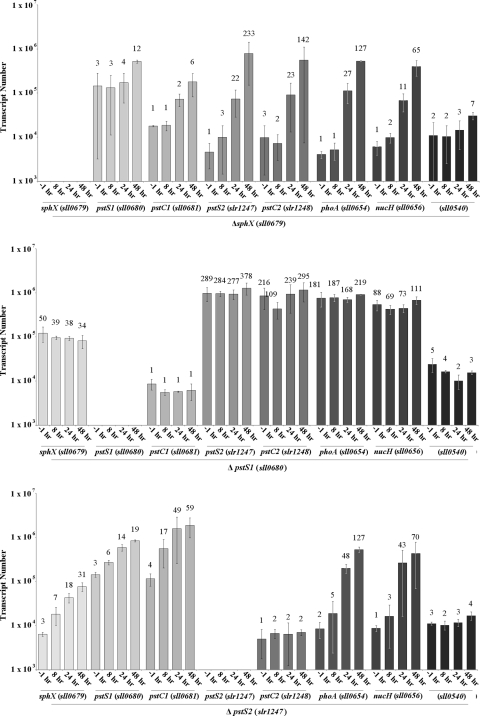

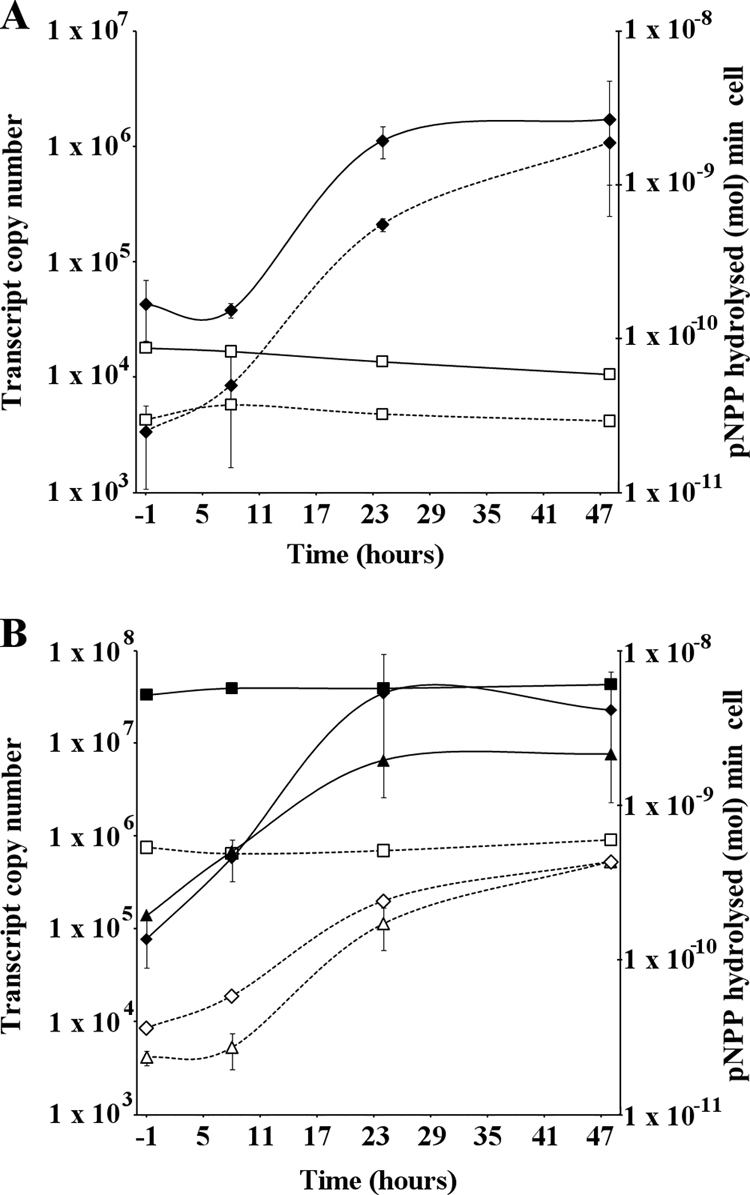

Expression levels of sphX, pstS1, pstS2, and sll0540 as well as the proposed pho regulon genes phoA (sll0654; alkaline phosphatase gene) and nucH (sll0656; extracellular nuclease gene) were monitored over a 48-h time course during conditions of sufficient Pi and conditions of Pi stress. Under Pi-replete conditions, transcript levels of all genes were relatively stable and did not fluctuate more than 2-fold (Fig. 4). Transcript levels at 48 h were used as a reference, and all subsequent fold changes in gene expression were compared to the value at this time point. While gene expression levels did not change significantly under Pi-replete conditions, it is important to note that expression levels of pstS1 (4.3 × 104 transcripts per ng of cDNA template) and pstC1 (3.2 × 104 transcripts per ng of cDNA template) were an order of magnitude higher than those of all of the other genes. Eight hours after transfer into Pi stress conditions, the expression levels of virtually all the genes analyzed increased significantly (Fig. 4), peaking approximately 48 h after transfer. The exception was sll0540, which showed only a minor (3-fold) increase in gene expression 48 h after transfer. No temporal difference in the induction of sphX, pstS1, or pstS2 gene expression was observed. However, strikingly, pstS2 underwent a >300-fold increase in its expression, with transcript numbers reaching 1.1 × 106 transcripts per ng of cDNA template, similar to those of pstS1. While phoA and nucH gene expression levels were unchanged during Pi-replete growth, following transfer to Pi stress conditions, expression increased over 250-fold and 120-fold, respectively. Concomitant measurement of AP activity (see Fig. 7A) showed induction kinetics similar to those measured by the phoA gene expression data.

FIG. 4.

Expression profiles of the Synechocystis pho regulon genes under Pi-replete (P+), Pi stress (P-), and N stress (N) conditions as well as following a shift to high light intensity (HL). Bar height indicates absolute transcript abundance per ng cDNA used in each qPCR. Numbers above each bar indicate fold change in gene expression compared to the gene transcript abundance at 48 h under Pi-replete conditions (indicated in bold).

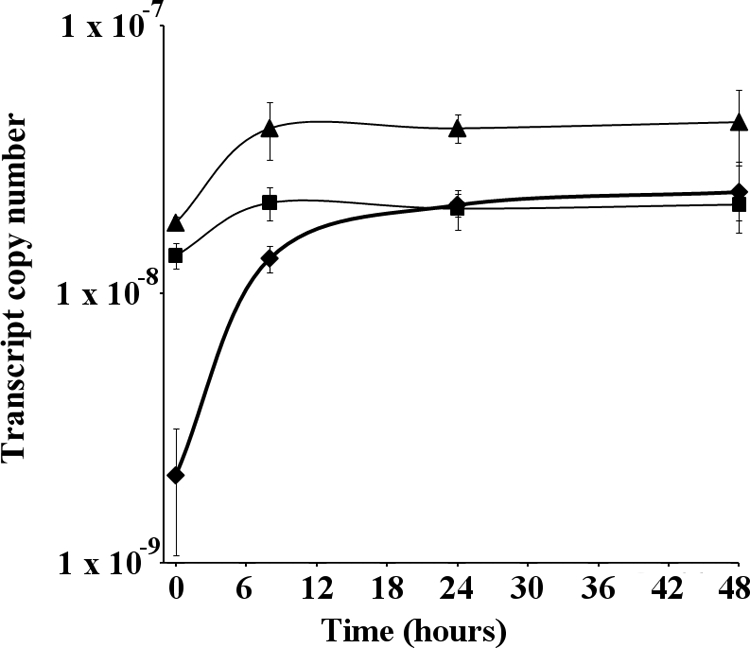

FIG. 7.

AP activity (solid lines) and sll0654 gene expression (dashed lines). (A) WT Synechocystis following transfer from Pi-replete to Pi stress conditions. □, Pi-replete conditions; ⧫, Pi stress conditions. (B) sphX, pstS1, and pstS2 disruption mutants following transfer from Pi-replete to Pi stress conditions. Squares, pstS1 mutant; diamonds, pstS2 mutant; triangles, sphX mutant. All AP assays were performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate maximum standard deviations observed.

PBP gene expression during nitrogen and high-light stress.

In order to assess whether the PBPs were differentially regulated by environmental factors other than Pi, we also followed gene expression following transfer to N stress conditions, or following a shift to high light intensity. While expression levels of sphX, pstS1, pstS2, phoA and nucH all increased following transfer to N stress conditions (Fig. 4), the maximum fold increases for nearly all genes analyzed were substantially lower (range, 5.6- to 25.8-fold lower). The exception was sphX, with transcript levels 1.7-fold greater than those observed during Pi stress conditions. Transfer to high-light conditions caused a rapid increase in expression of virtually all the pho regulon genes (Fig. 4), but this response was transient, with maximum transcript levels peaking at 6 h exposure and then generally returning to prestress levels by 24 h. The exceptions were pstC2 and pstC1, whose expression levels slightly increased and decreased, respectively.

Construction and gene expression analysis of PBP interposon mutants.

To determine the precise functional role of individual PBPs (except that encoded by sll0540, which showed no obvious induction of gene expression during Pi conditions and hence was not further analyzed), interposon mutants in each of the corresponding genes were constructed (Fig. 2). Confirmation of complete segregation of each mutant was verified by PCR (Fig. 5A). Both the sphX and pstS2 mutants retained their ability to respond to change in external Pi. Thus, transcript levels of pho regulon genes were similar to the WT levels under Pi-replete conditions (time point, −1 h; Fig. 6) but following transfer to Pi stress conditions increased as for the WT, though maximum fold increases were slightly lower. Exceptions to these trends were the elevated levels of pstC2 in the sphX mutant, while in the pstS2 mutant, levels of pstC2 remained low and levels of pstC1 increased to 4-fold higher than that in the WT (Fig. 6). However, in the pstS1 mutant, high and constitutive levels of sphX, pstS2, pstC2, phoA, and nucH gene expression were observed irrespective of growth conditions (Fig. 6), suggesting an inability to regulate pho regulon gene expression in response to the external Pi concentration. Levels of pstC1 transcript were also constitutively expressed in this mutant but at a considerably lower level than for the WT. AP activity measurements (Fig. 7B) mirrored phoA gene expression levels in each of the PBP mutants.

FIG. 5.

PCR determination of the disruption of the targeted genes compared to Synechocystis WT. Data for sphX, pstS1, and pstS2 (A) and pst (B) gene clusters are shown. This demonstrates that the disruption/deletion was obtained in all cases and that complete segregation occurred in each PBP and Δpst1 and Δpst2 mutants.

FIG. 6.

Expression profiles of the pho regulon genes from Synechocystis PBP gene disruption mutants following transfer to Pi stress conditions. Bar height indicates absolute transcript abundance per ng cDNA used in each qPCR. Numbers above each bar indicate fold change in gene expression compared to the gene transcript abundance at 48 h under Pi-replete conditions (see Fig. 4).

Transformation incompetence of the pstS1 mutant.

Attempts to complement the pstS1 mutant by using a plasmid created for the insertion of WT pstS1 into the psbAII gene or control transformations using a disruption construct for a non-pho-regulon-related gene were repeatedly unsuccessful, despite successful transformation of WT cells with an average efficiency of 1.8 × 103 transformants/μg DNA. This loss of natural transformation capacity was confirmed in five further independent pstS1 disruption mutants, despite increasing the amount of plasmid from 1 to 10 μg in the transformation mix. Indeed, incubating pstS1 cells with 2 μg of plasmid DNA showed no significant degradation of the added DNA even after 5 h of incubation (data not shown). Interestingly, this loss of transformation capacity correlates with the high, and constitutive, expressions of phoA and nucH potentially producing high-level phosphatase and nuclease activities in the periplasm of the pstS1 mutant.

Construction of pst1 and pst2 gene cluster deletion mutants.

Δpst1 and Δpst2 mutants were created using λ Red-mediated recombination to assess the kinetic properties of individual ABC transporters. During mutant construction, the apramycin resistance cassette was inserted in frame, from the start codon of the first gene to the stop codon of the last gene of each transporter (see Fig. 1 for gene order), to minimize any downstream effects. Complete segregation of each mutant was again ascertained by PCR (Fig. 5B).

32Pi radiotracer uptake kinetics in pst1 and pst2 deletion mutants.

32Pi uptake kinetics performed on Δpst1 and Δpst2 mutants as well as WT cells showed dramatic differences in half-saturation constant (Ks) values and maximum uptake velocities (Vmaxs) (Table 4). The Δpst1 mutant had a >50-fold higher affinity for Pi than the Δpst2 mutant did, whereas the Vmax for the Δpst2 mutant was 35-fold greater than that for the Δpst1 mutant. The Synechocystis WT strain demonstrated differential uptake kinetics dependent on the Pi concentration range used, but values were generally consistent with those obtained for “individual” transporters, as evidenced in the pst1 and pst2 mutants.

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters of Pi uptake in WT Synechocystis and pst1 and pst2 whole-gene-cluster deletion mutantsa

| Strain | High range (10-0.75 μM) |

Low range (250-15 nM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ks (μM) | Vmax (fmol cell−1 min−1) | Ks (μM) | Vmax (fmol cell−1 min−1) | |

| Wild type | 3.26 ± 0.5 | 34.15 ± 3.66 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 3.8 ± 0.75 |

| Δpst1 mutant | — | — | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.11 |

| Δpst2 mutant | 3.7 ± 0.7 | 31.18 ± 3.96 | — | — |

Maximum uptake rates (Vmax) and half-saturation constants (Ks) were obtained from five independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. The standard deviations are indicated. Dashes indicate that no measurable Pi uptake occurred during the time frame of the experiment.

AP activity in the pstS1 interposon mutant and the pst1 deletion mutant can be modulated.

qPCR and AP activity data (Fig. 7B) showed that the pstS1 mutant has high and constitutive AP levels. Such data were obtained following growth of the Synechocystis WT and the pstS1 mutant in normal BG-11 medium, containing 420 μM Pi, for 48 h prior to washing and transfer to Pi stress conditions. To assess whether these alkaline phosphatase levels could be modulated, we exposed WT and mutant cells to 7.5 mM Pi (i.e., Pi excess) 12 h prior to transfer. Under such conditions, in the pstS1 mutant, there was a >50% reduction in AP activity immediately following transfer compared to activity at 8 h (Fig. 8). Similarly, the pst1 whole-gene-cluster deletion mutant showed a >35% reduction in activity at 0 h compared to that at 8 h. However, the extent of this repression was still much lower than that for the WT, for which the activity was reduced >85%.

FIG. 8.

AP activity in WT, pstS1, and pst1 mutants following transfer from Pi-replete to Pi-stress conditions. ⧫, WT; ▴, pstS1 mutant; ▪, pst1 mutant. All AP assays were performed in triplicate. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of three replicates.

DISCUSSION

It is becoming increasingly apparent that cyanobacteria are not only able to thrive in environments with nanomolar concentrations of Pi but able to take advantage of periods of nutrient excess, forming extensive blooms in the ultimate stages of eutrophication (16). Such adaptability suggests that cyanobacteria possess a distinct competitive advantage when it comes to acquisition of Pi.

Genomic analyses demonstrate that a plethora of ABC transporters exists in cyanobacteria (40) and that, particularly in some freshwater strains, expansion and duplication of some of these systems have occurred (8). However, as yet, little work to elucidate the physiological role of such duplications or to identify any ecological advantages this may impart has been performed. Pi transport in Synechocystis is ideally placed as a model in this respect, since bioinformatic analyses have identified both duplicate ABC transporters and multiple associated binding proteins in this strain (43), while the organism is also readily genetically amenable (for an example, see reference 19), facilitating construction of specific transporter component mutants.

In this study, we attempted to answer two questions. First, is there a difference in function between the two putative Pi transporters, or is this simply functional “redundancy”? Second, within each Pi transporter, what is the role played by multiple and potentially redundant PBP components? In so doing, we also aimed to elucidate cellular control of specific Pi transporter components under a range of environmental variables.

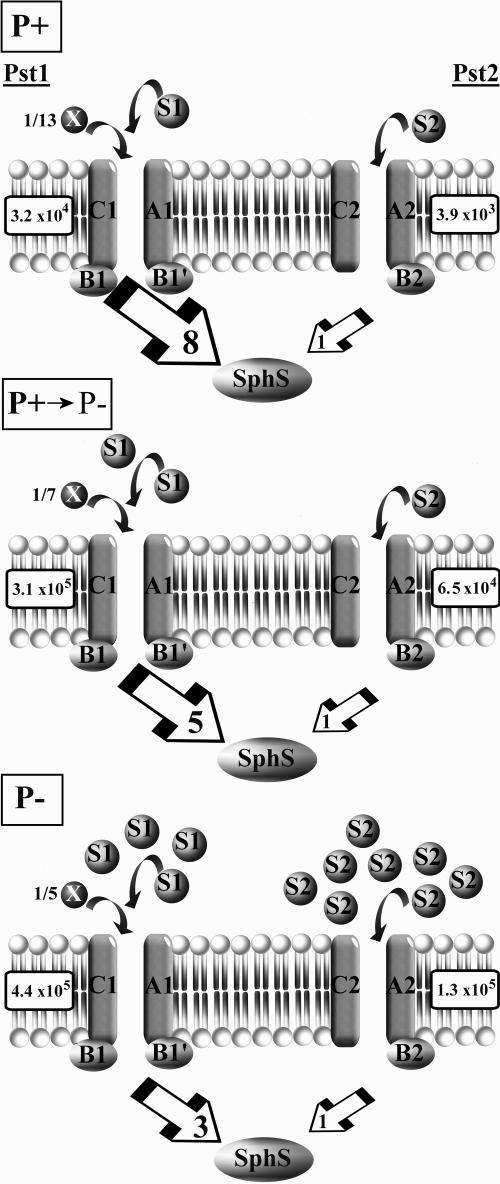

To begin to address the first question, we compared gene expression profiles of Pi transporter components in WT cells grown under Pi-replete or Pi stress conditions. Strikingly, under growth with sufficient Pi, pst1 transporter gene expression (represented by pstC1 and pstS1 transcript abundance) was on average 10-fold higher than that of pst2, i.e., as evidenced by pstC2 and pstS2 transcription (Fig. 4). However, shifting to Pi stress conditions caused dramatic (>300-fold) upregulations of pstS2 gene expression and, to a lesser extent, pstC2 (>40-fold), compared to the increases in pstS1 (>50-fold) and pstC1 (>20-fold), respectively. Thus, the individual Pi transporters appear to be differentially expressed as a function of the external Pi concentration. Subsequent construction of whole-gene-cluster deletion mutants and radiotracer uptake studies unequivocally demonstrated that each of the transporters has very different transport kinetic properties (Table 4), with a high-velocity, low-affinity Pst1 transporter contrasting with the low-velocity, high-affinity Pst2 transporter. Such biochemical information ties in nicely with the gene expression data, with high pst1 expression under conditions of sufficient Pi facilitating a high rate of Pi uptake and allowing cells to take full advantage of an abundance of Pi (either by maintenance of a high growth rate or via luxury uptake and storage of Pi as polyphosphate; for an example, see reference 18). Under Pi stress conditions, pstS2 and phoA-nucH gene expression levels increase substantially. Such induction of periplasmic or cell wall-associated enzymes capable of removing Pi groups from a wide variety of organic sources is typical for bacteria experiencing Pi stress (7, 27, 33, 48, 52) and is consistent with the elevated level of the PBP specific to this transporter facilitating maximal scavenging and delivery of Pi to pst2 under stress conditions. Thus, possession of two Pi transporters gives Synechocystis the ability to extend the dynamic range over which Pi is acquired, potentially imparting a distinct ecological advantage over bacterial competitors.

The kinetic values reported here for the Pst1 and Pst2 transporters are within the range reported for other cyanobacteria (20, 21) and natural phytoplankton populations (12). However, much of the culture data relates to strains for which genome information is lacking, and hence, for which it is not known whether there is more than one Pi ABC transporter. Like that of Synechocystis, the genomes of hot spring Synechococcus sp. isolates OS-B′ and OS-A, Anabaena variabilis, Anabaena sp. strain PCC 7120, and Gloeobacter violaceus PCC 7421 also contain two potential Pi ABC transporters (43). Interestingly, phylogenetic analysis of the Synechocystis, Anabaena, and Gloeobacter pstS genes, which collectively describe a freshwater PstS clade (Fig. 3), contain two well-supported subclades, each containing a single PstS member from each strain. Hence, this might delineate biochemically divergent proteins with different binding affinities consistent with kinetic parameters for the whole transporter. In contrast, none of the genomes of any marine picocyanobacteria (40) or Trichodesmium erythraeum IMS101 (36, 43) contains two pst transporter gene clusters, although several contain multiple PBP gene homologs. This might indicate that in marine environments with persistently low Pi concentrations, a single high-affinity Pst system has been selected for (see reference 1), in contrast to some freshwater environments where bioavailable Pi may fluctuate more frequently and over a greater concentration range, making it advantageous to have transporters with different kinetic and regulatory characteristics, as seen here with Synechocystis. However, it is also possible that the kinetic properties of even a single Pst system do differ subtly between strains, particularly if the multiple PBP components impart different Pi affinities. Indeed, in one freshwater Synechococcus organism, a single PBP possessed different Pi binding sites with dissociation constants in the micromolar and submicromolar ranges (50).

Extending comparison of the different kinetic properties of the Synechocystis Pst1 and Pst2 transporters more broadly, it is perhaps not surprising that most cyanobacterial genomes so far analyzed lack orthologs of the low-affinity Pit transporter found in E. coli, given that the half-saturation constant for the E. coli Pit transporter is 38 μM (55). Such a transporter would be ineffective in acquiring sufficient Pi to sustain cell growth at the levels generally found in freshwater systems.

After obtaining evidence for the differing kinetic properties of the two Pst transporters, we sought to examine the role of specific PBP components. qPCR data clearly demonstrated differential expressions of sphX and pstS1 within pst1, with fold increases in sphX expression about 40% less than that of pstS1. Such differential regulation is consistent with computational prediction (43) of a pho box located between sphX and pstS1 that corresponds to the experimentally determined PyTTAAPyPy(T/A) repeats found by Suzuki et al. (45) to bind the Pi response regulator SphR, which could explain the different expression patterns. Variation in the expression patterns of distinct PBP components was also observed following a shift to high light intensity or transfer of Synechocystis to N stress conditions. The high-light shift caused a transient increase in PBP gene expression peaking at 6 h and then declining to almost prestress levels by 24 h. However, while expression of pstS1 increased >25-fold, fold increases of sphX and pstS2 expression levels were much lower, well below the values observed during Pi stress. This upregulation of pstS1 (sll0680) has been previously reported (6) and is consistent with the suggestion that under high-light conditions, Pi acquisition cannot keep pace with the growth potential of the cell, leading the cell to perceive Pi stress. Such an idea is consistent with the pho regulon sensor kinase SphS containing a PAS domain, since such modules are known to monitor changing light levels or redox potential (45, 46).

Further demonstration of differential expression of PBP components occurred following transfer of Synechocystis to N stress conditions. While this caused only a small increase in pstS1 and pstS2 gene expression levels, sphX levels were >60% higher than even those achieved under Pi stress. Potential control of sphX gene expression by the N-regulatory network warrants further investigation, especially if this might provide evidence for coregulation of N and Pi acquisition.

Additional evidence for a distinct role of SphX compared to PstS1 (or PstS2) was provided by qPCR data for the PBP disruption mutants upon transfer to Pi stress conditions. Thus, while the sphX and pstS2 mutants showed upregulation of pho regulon genes similar to that of the WT, the pstS1 mutant displayed high-level expression of pho regulon genes and high AP activity under both Pi-replete and Pi stress conditions, suggesting that the mutant had lost regulatory capacity and, hence, the ability to detect changes in external Pi. This suggests that Synechocystis primarily senses change in external [Pi] via the flow of Pi through PstS1 and interaction with its cognate Pst1 transporter to transmit a signal perceived by the sensor kinase SphS. However, providing Pi in excess prior to a shift to Pi stress conditions in either the pstS1 mutant or the pst1 whole-gene-cluster deletion mutant showed that AP activity could be modulated (Fig. 8), suggesting some regulatory capacity even in the absence of any pst1 transporter component. Thus, it is possible that SphS is able to interact with both Pst1 and Pst2 to transmit a Pi stress signal but that this signal primarily derives from Pst1 and the level of Pi occupancy by PstS1 (Fig. 9). Such a model would be coherent with the observed expression levels of the Pst1 and Pst2 transporters during Pi-replete and Pi stress conditions. This model assumes that SphS interacts with a Pi ABC transporter component in a way similar to that of the E. coli Pi sensor PhoR, with PhoU acting as a negative regulator of the system (52). Indeed, recent evidence suggests that Synechocystis sphU (encoding a PhoU ortholog) plays a similar role (29) and that the extended N terminus of SphS is required for perception of Pi stress in Synechocystis (9).

FIG. 9.

Schematic model describing the abundance of each Pi transporter during a shift from Pi-replete (P+) to Pi stress (P-) conditions. The number of PBPs relative to each associated Pi transporter is calculated from the ratio of PBP to pstC transporter transcript abundance. Where this ratio is <1, a fraction adjacent to the PBP indicates its value. Large box arrows indicate the ratio of pstC1 transcript abundance to pstC2 transcript abundance. Transcript abundance values were taken at 48 h in Pi-replete conditions (P+) or 24 h (P+ → P-) or 48 h (P-) after transfer to P stress conditions (see Fig. 4). Boxed numbers adjacent to each Pi transporter represent actual pstC1 or pstC2 transcript abundance under each condition (see above).

Acknowledgments

F.D.P. was the recipient of a NERC-funded Ph.D. studentship.

We thank M. Clokie for helpful discussions and analysis of the real-time PCR experiments, S. Bryan for providing assistance during the construction of the Synechocystis disruption mutants, and M. Ostrowski for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 April 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, M. M., M. R. Gomez-Garcia, A. R. Grossman, and D. Bhaya. 2008. Phosphorus deprivation responses and phosphonate utilization in a thermophilic Synechococcus sp. from microbial mats. J. Bacteriol. 190:8171-8184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiba, H., and T. Mizuno. 1994. A novel gene whose expression is regulated by the response-regulator, SphR, in response to phosphate limitation in Synechococcus species PCC7942. Mol. Microbiol. 13:25-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alley, M. R. K. 1987. Molecular biological aspects of nitrogen starvation in cyanobacteria. Ph.D. thesis. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Warwick, Coventry, United Kingdom.

- 4.Applied Biosystems. 2001. User bulletin #2, ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system. Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA.

- 5.Bessey, O. A., O. H. Lowry, and M. J. Brock. 1946. A method for the rapid determination of alkaline phosphatase with five cubic millimeters of serum. J. Biol. Chem. 164:321-329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhaya, D., D. Vaulot, P. Amin, A. W. Takahashi, and A. R. Grossman. 2000. Isolation of regulated genes of the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 by differential display. J. Bacteriol. 182:5692-5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Block, M. A., and A. R. Grossman. 1988. Identification and purification of a derepressible alkaline-phosphatase from Anacystis nidulans R2. Plant Physiol. 86:1179-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bu, L., J. Xiao, L. Lu, G. Xu, J. Li, F. Zhao, X. Li, and J. Wu. 2009. The repertoire and evolution of ATP-binding cassette systems in Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus. J. Mol. Evol. 69:300-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burut-Archanai, S., A. Incharoensakdi, and J. J. Eaton-Rye. 2009. The extended N-terminal region of SphS is required for detection of external phosphate levels in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 378:383-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan, F. Y., and A. Torriani. 1996. PstB protein of the phosphate-specific transport system of Escherichia coli is an ATPase. J. Bacteriol. 178:3974-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clokie, M. R. J., J. Y. Shan, S. Bailey, Y. Jia, H. M. Krisch, S. West, and N. H. Mann. 2006. Transcription of a ‘photosynthetic’ T4-type phage during infection of a marine cyanobacterium. Environ. Microbiol. 8:827-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotner, J. B., and R. G. Wetzel. 1992. Uptake of dissolved inorganic and organic phosphorus compounds by phytoplankton and bacterioplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 37:232-243. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Currie, D. J. 1990. Large-scale variability and interactions among phytoplankton, bacterioplankton, and phosphorus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 35:1437-1455. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Currie, D. J., and J. Kalff. 1984. A comparison of the abilities of freshwater algae and bacteria to acquire and retain phosphorus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 29:298-310. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dokulil, M. T., and K. Teubner. 2000. Cyanobacterial dominance in lakes. Hydrobiologia 438:1-12. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eguchi, M., M. Ostrowski, F. Fegatella, J. Bowman, D. Nichols, T. Nishino, and R. Cavicchioli. 2001. Sphingomonas alaskensis strain AFO1, an abundant oligotrophic ultramicrobacterium from the North Pacific. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4945-4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falkner, R., and G. Falkner. 1989. Phosphate uptake by eukaryotic algae in cultures and by a mixed phytoplankton population in a lake—analysis by a force flow relationship. Bot. Acta 102:283-286. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores, E., A. M. Muro-Pastor, and J. C. Meeks. 2008. Gene transfer to cyanobacteria in the laboratory and in nature, p. 45-57. In A. Herrero and E. Flores (ed.), The cyanobacteria: molecular biology, genomics and evolution. Caister Academic Press, Norfolk, United Kingdom.

- 20.Fu, F. X., Y. H. Zhang, Y. Y. Feng, and D. A. Hutchins. 2006. Phosphate and ATP uptake and growth kinetics in axenic cultures of the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. CCMP 1334. Eur. J. Phycol. 41:15-28. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grillo, J. F., and J. Gibson. 1979. Regulation of phosphate accumulation in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus. J. Bacteriol. 140:508-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gust, B., G. Chandra, D. Jakimowicz, Y. Q. Tian, C. J. Bruton, and K. F. Chater. 2004. λ Red-mediated genetic manipulation of antibiotic-producing Streptomyces. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 54:107-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hecky, R. E., and P. Kilham. 1988. Nutrient limitation of phytoplankton in freshwater and marine environments—a review of recent evidence on the effects of enrichment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33:796-822. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffer, S. M., and J. Tommassen. 2001. The phosphate-binding protein of Escherichia coli is not essential for Pi-regulated expression of the pho regulon. J. Bacteriol. 183:5768-5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudson, J. J., and W. D. Taylor. 2005. Rapid estimation of phosphate at picomolar concentrations in freshwater lakes with potential application to P-limited marine systems. Aquat. Sci. 67:316-325. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hulett, F. M. 2002. Bacillus subtilis and its closest relatives: from genes to cells, p. 193-201. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 27.Hulett, F. M., C. Bookstein, and K. Jensen. 1990. Evidence for two structural genes for alkaline phosphatase in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 172:735-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson, R. J., M. R. B. Binet, L. J. Lee, R. Ma, A. I. Graham, C. W. McLeod, and R. K. Poole. 2008. Expression of the PitA phosphate/metal transporter of Escherichia coli is responsive to zinc and inorganic phosphate levels. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 289:219-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juntarajumnong, W., T. A. Hirani, J. M. Simpson, A. Incharoensakdi, and J. J. Eaton-Rye. 2007. Phosphate sensing in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803: SphU and the SphS-SphR two-component regulatory system. Arch. Microbiol. 188:389-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luecke, H., and F. A. Quiocho. 1990. High specificity of a phosphate-transport protein determined by hydrogen-bonds. Nature 347:402-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makino, K., M. Amemura, S.-K. Kim, A. Nakata, and H. Shinagawa. 1994. Mechanism of transcriptional activation of the phosphate regulon in Escherichia coli, p. 5-12. In A. Torriani-Gorini, E. Yagil, and S. Silver (ed.), Phosphate in microorganisms. ASM, Washington, DC.

- 32.Mann, N. H., and D. J. Scanlan. 1994. The SphX protein of Synechococcus sp. PCC7942 belongs to a family of phosphate-binding proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 14:595-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore, L. R., M. Ostrowski, D. J. Scanlan, K. Feren, and T. Sweetsir. 2005. Ecotypic variation in phosphorus acquisition mechanisms within marine picocyanobacteria. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 39:257-269. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray, M. G., and W. F. Thompson. 1980. Rapid isolation of high molecular-weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8:4321-4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nair, U., C. Thomas, and S. S. Golden. 2001. Functional elements of the strong psbAI promoter of Synechococcus elongatus sp. PCC 7942. J. Bacteriol. 183:1740-1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orchard, E. D., E. A. Webb, and S. T. Dyhrman. 2009. Molecular analysis of the phosphorus starvation response in Trichodesmium spp. Environ. Microbiol. 11:2400-2411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prentki, P., and H. M. Krisch. 1984. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene 29:303-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rippka, R., J. Deruelles, J. B. Waterbury, M. Herdman, and R. Y. Stanier. 1979. Generic assignments, strain histories and properties of pure cultures of cyanobacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 111:1-61. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scanlan, D. J., N. H. Mann, and N. G. Carr. 1993. The response of the picoplanktonic marine cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. WH7803 to phosphate starvation involves a protein homologous to the periplasmic phosphate-binding protein of Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 10:181-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scanlan, D. J., M. Ostrowski, S. Mazard, A. Dufresne, L. Garczarek, W. R. Hess, A. F. Post, M. Hagemann, I. Paulsen, and F. Partensky. 2009. Ecological genomics of marine picocyanobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:249-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schindler, D. W. 1977. Evolution of phosphorus limitation in lakes. Science 195:260-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanier, R. Y., and G. Cohen-Bazire. 1977. Phototropic prokaryotes: the cyanobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 31:225-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su, Z. C., V. Olman, and Y. Xu. 2007. Computational prediction of Pho regulons in cyanobacteria. BMC Genomics 8:156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Surin, B. P., H. Rosenberg, and G. B. Cox. 1985. Phosphate-specific transport system of Escherichia coli—nucleotide sequence and gene polypeptide relationships. J. Bacteriol. 161:189-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuki, S., A. Ferjani, I. Suzuki, and N. Murata. 2004. The SphS-SphR two component system is the exclusive sensor for the induction of gene expression in response to phosphate limitation in Synechocystis. J. Biol. Chem. 279:13234-13240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor, B. L., and I. B. Zhulin. 1999. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:479-506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torriani-Gorini, A. 1994. The pho regulon of Escherichia coli—introduction, p. 1-4. In A. Torriani-Gorini, E. Yagil, and S. Silver (ed.), Phosphate in microorganisms: cellular and molecular biology. ASM, Washington, DC.

- 49.van Veen, H. W., T. Abee, G. J. J. Kortstee, W. N. Konings, and A. J. B. Zehnder. 1994. Translocation of metal phosphate via the phosphate inorganic transport-system of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 33:1766-1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wagner, F., M. Gimona, H. Ahorn, G. A. Peschek, and G. Falkner. 1994. Isolation and functional reconstitution of a phosphate-binding protein of the cyanobacterium Anacystis nidulans induced during phosphate-limited growth. J. Biol. Chem. 269:5509-5511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wanner, B. L. 1993. Gene regulation by phosphate in enteric bacteria. J. Cell. Biochem. 51:47-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wanner, B. L. 1996. Phosphorus assimilation and control of the phosphate regulon, p. 1357-1377. .In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 53.Williams, J. G. K. 1988. Construction of specific mutations in photosystem II photosynthetic reaction center by genetic engineering methods in Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Methods Enzymol. 167:766-778. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willsky, G. R., R. L. Bennett, and M. H. Malamy. 1973. Inorganic phosphate transport in Escherichia coli: involvement of two genes which play a role in alkaline phosphatase regulation. J. Bacteriol. 113:529-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Willsky, G. R., and M. H. Malamy. 1980. Characterization of two genetically separable inorganic phosphate transport systems in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 144:356-365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]