Abstract

Routine cystic fibrosis (CF) medical care includes invasive procedures that may be difficult for young children and adolescents to tolerate because of anxiety, concern with health status, or unfamiliarity with the performed tasks. A growing body of pediatric psychology literature suggests that behavior therapy can effectively increase patient cooperation with stressful medical procedures such as tracheostomy care and needle sticks. Throat cultures are obtained at least quarterly in the outpatient setting or more frequently if a CF patient develops respiratory symptoms. Obtaining a throat culture from an anxious and uncooperative child poses a significant challenge for physicians, since the child may demonstrate emotional distress and avoidant behavior that disrupts efficient specimen collection during a routine clinic visit. The use of behavioral interventions, such as relaxation exercises, diaphragmatic breathing, differential reinforcement, gradual exposure, and systematic desensitization, is beneficial in addressing this commonly encountered problem in CF care.

This case series describes the implementation of a behavioral therapy protocol utilizing two interventions, gradual exposure and systematic desensitization, in two young CF patients for the treatment of behavioral distress with routine throat cultures. The behavioral interventions were simple and transferred easily from mock procedures to actual specimen collection. Moreover, these cases highlight the important roles of the pediatric psychology staff on a comprehensive multidisciplinary CF care team to improve patient cooperation with routine clinic procedures and the medical treatment regimen overall.

Keywords: Cystic fibrosis, Behavioral psychology, Throat culture, Systematic desensitization, Coping strategy, Adherence

1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF), an inherited disease characterized by chronic progressive pulmonary disease and malabsorption, requires lifelong comprehensive care to improve physical health, quality of life, and overall survival [1]. The complex medical treatment regimen involves a multidisciplinary care team comprised at this center of pediatric pulmonologists, nurses, physical therapists, dietitians, respiratory therapists, pharmacologists, social workers, and pediatric psychologists [2]. Routine medical care includes quarterly procedures, namely measurement of height, weight, and pulmonary function. In addition, throat or sputum cultures are obtained to screen for bacterial infections that typically characterize CF lung disease. Annual tests include measurement of serum chemistries and radiographic studies to track various parameters of nutritional status and lung disease progression. These procedures are difficult to tolerate for young children and adolescents because of anxiety, concern with health status and well-being, or especially in younger children, unfamiliarity with the performed tasks.

The psychology literature suggests that behavior therapy, specifically graded exposure and systematic desensitization, has effectively increased pediatric patients’ cooperation with stressful medical procedures. Targeted behavior therapy techniques in other pediatric medical conditions, such as neurodevelopmental disability, Down syndrome, and cancer have improved patient cooperation with tracheostomy suctioning and care [3], self-catheterization [4], neuroimaging [5,6], radiation therapy [7,8], and needle sticks [3,9,10]. To our knowledge, there are no data presenting the use of behavioral therapy in CF patients to specifically address cooperation with routine throat cultures.

Throat cultures in CF patients are obtained quarterly or more frequently if respiratory symptoms progress [11]. Obtaining a throat culture specimen from an anxious and uncooperative child can be challenging for physicians, since he/she may demonstrate emotional distress and avoidant behavior that disrupts efficient collection. The use of behavioral interventions in the form of relaxation exercises, diaphragmatic breathing, differential reinforcement, gradual exposure, and systematic desensitization is beneficial in addressing this commonly encountered problem. This report describes the use of gradual exposure and systematic desensitization to help two young CF patients undergo routine throat cultures during regular outpatient clinic visits.

2. Clinical report

2.1. Case series

Patients A (6 y) and B (4 y), followed at an accredited pediatric CF center, exhibited significant behavioral distress (crying, yelling “no”, escaping from the physician) when routine throat cultures were attempted during clinic visits. The physicians made several efforts to soothe both patients but were unsuccessful in obtaining a throat culture for Patient A, whereas Patient B required parental assistance in order to successfully perform the procedure.

2.2. Method

After pediatric psychology staff conducted an assessment of behavioral stressors and barriers (Table 1), both patients were referred to an affiliated outpatient pediatric psychology consultation clinic specializing in the treatment of children with chronic medical conditions. Behavior therapy sessions consisted of thorough clinical interviews with both the child and caregiver to assess the child’s developmental and medical histories and cognitive abilities, review knowledge about the procedure, evaluate barriers, and explain the treatment course and use of behavioral interventions.

Table 1.

Barriers in obtaining routine outpatient CF throat cultures.

| Parent/caregiver |

| Understanding of clinical disease and processes |

| Anxiety about child’s discomfort |

| Anger or frustration toward clinical care provider(s) |

| Difficulty with limit-setting |

| Length of outpatient visit |

| Child |

| Understanding and self-awareness of disease |

Anxiety and frustration

|

Delay and avoidant behavior

|

| Clinical care provider(s) |

| Response to cooperation of child and parent |

Changing clinical management approach

|

| Length and efficiency of outpatient visit |

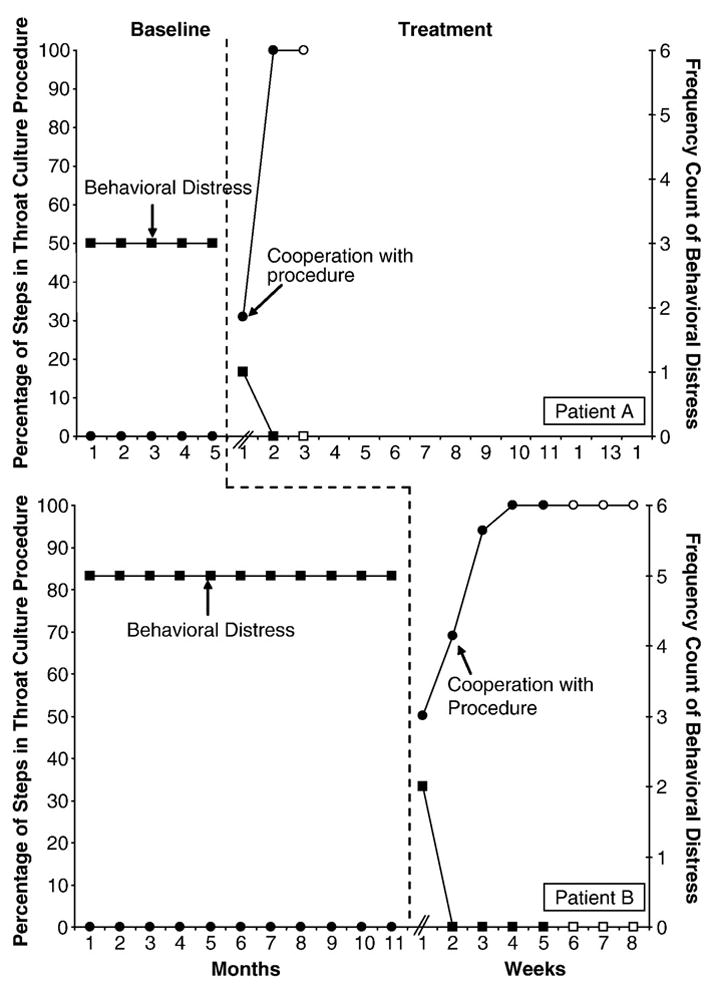

Treatment sessions for both patients implemented a behavioral therapy protocol that included gradual exposure and systematic desensitization during mock throat culture procedures using the following six steps: (a) conducting a task analysis of the procedure (Table 2); (b) providing distraction from uncomfortable feelings using preferred activities; (c) counterconditioning emotional arousal by providing preferred activities to induce a relaxed and positive experience; (d) maintaining the child’s positive experience while gradually exposing him/her to the steps in the task analysis and the associated feelings; (e) differential reinforcement of partial adherence by providing contingent praise and preferred events; and (f) preventing escape-avoidance behavior by blocking and redirecting these attempts [3]. Data on the percentage of task analysis steps with child distress behavior are displayed for both patients (Fig. 1) using a nonconcurrent multiple baseline design [12].

Table 2.

Task analysis by patient and session.

| Session | Patient A | Patient B |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | –Clinical interview | –Clinical interview |

| –Assessment of behavioral stressors and barriers | –Assessment of behavioral stressors and barriers | |

| –Model, practice, and rehearse coping strategies | –Model, practice, and rehearse coping strategies | |

| –Medical play and exposure to throat swab with preferred toys | –Medical play with medical instruments, preferred toys | |

| –Play with toys with throat swab on table | –Play with toys with throat swab on table | |

| –Begin playing with throat swab with preferred toys | –Hold throat swab while playing | |

| –Hold throat swab while playing | ||

| –Open mouth | ||

| –Clinician brings throat swab to open mouth | ||

| –Throat swab to touch lip | ||

| 2 | –Throat swab to touch lip | –Begin playing with throat swab with preferred toys |

| –Throat swab to touch inside of left cheek | –Open mouth | |

| –Throat swab touch inside of right cheek | –Clinician brings throat swab to open mouth | |

| –Throat swab to touch tip of tongue | ||

| –Throat swab to touch middle of tongue | ||

| –Throat swab to touch back of tongue | ||

| 3 | –Cooperative in CF clinic visit and successfully obtained throat swab by physician | –Begin playing with throat swab with preferred toys |

| –Throat swab to touch lip | ||

| –Throat swab to touch inside of left cheek | ||

| –Throat swab touch inside of right cheek | ||

| 4 | –Throat swab touch inside of right cheek | |

| –Throat swab to touch tip of tongue | ||

| –Throat swab to touch middle of tongue | ||

| –Throat swab to touch back of tongue | ||

| 5 | –Generalized session to medical clinic setting | |

| –Throat swab to touch tip of tongue | ||

| –Throat swab to touch middle of tongue | ||

| –Throat swab to touch back of tongue | ||

| 6 | –Cooperative in CF clinic visit and successfully obtained throat swab | |

| 7 | –Cooperative in CF clinic visit and successfully obtained throat swab | |

| 8 | –Cooperative in CF clinic visit and successfully obtained throat swab |

Fig. 1.

Treating behavioral distress with routine clinic procedures in children with CF. Prior to behavioral intervention therapy, Patients A and B exhibited significant behavioral distress and poor cooperation with obtaining routine throat cultures. After 2 weeks of therapy, neither patient exhibited behavioral distress with the procedure. Patient A demonstrated medical cooperation after 2 weeks of behavioral therapy, whereas Patient B showed full medical cooperation after 4 weeks. Closed symbols indicate mock behavioral therapy sessions, while open symbols reflect successful specimen collection during the CF clinic visit.

2.3. Results

After five months of unsuccessful attempts to obtain routine throat cultures, Patient A attended three outpatient behavior therapy sessions over one month. In the first two sessions, Patient A exhibited distress but eventually tolerated placement of the throat culture swab on the back of the tongue. The third and final session occurred at the scheduled CF clinic visit, when the physician successfully obtained a throat culture with minimal patient distress.

Patient B required six behavior therapy sessions over two months after medical professionals were unable to obtain adequate throat cultures for nearly eleven months. Five sessions were geared toward behavior modification and caregiver training. These sessions included methods for the caregiver to implement consistent structure with the medical procedure, use differential reinforcement, and provide Patient B with access to preferred activities contingent upon successful task completion. The fifth session took place in a typical examination room to facilitate generalization to the actual CF clinical outpatient setting. Sessions six through eight were completed during routine CF clinic visits. Psychology staff aided the physician in implementing the behavioral routine and prompted Patient B’s use of learned coping strategies (e.g., distraction and imagery). Patient B was successful in completing the procedure with minimal behavioral distress but continues to require brief reviews of coping strategies during routine clinic visits in order to prevent full relapse one year after therapy.

3. Discussion

These cases demonstrate the use of behavior therapy, namely gradual exposure and systematic desensitization, in treating behavioral distress and cooperation with routine throat cultures in patients with CF. Although the treatment duration and outcomes varied in this case series, the behavioral interventions were similar, simple, and easily transferred from mock procedures to actual specimen collection.

Behavioral distress during pediatric medical procedures is challenging, causes frustration for parents and physicians, and presents practical barriers to and potential ethical conflicts in providing effective patient care. In patients with CF, it is imperative to obtain routine throat cultures to screen for chronic bacterial infection, which in turn affects clinical management of lung disease. Assessing and treating behavioral distress in young children removes this barrier and prevents the development of conditioned responses that may generalize to other aspects of medical care.

Behavior that is maintained by intermittent negative reinforcement (sometimes resulting in escape or avoidance of aversive or non-preferred stimuli) is especially persistent and very unlikely to remit spontaneously [13]. Spontaneous remission of medical procedure-related distress and avoidance behavior is unlikely to occur in children because sooner or later a well-intentioned caregiver will respond to the child’s behavioral distress and associated avoidant behavior by allowing the child to, at least temporarily, avoid the negative stimulation produced by the procedure (by taking a break or rescheduling contingent on distress and avoidant behavior). As a result of this cycle of distress, avoidance, and negative reinforcement, the child’s and caregiver’s behavior patterns can become entrenched. Therefore, given the improbability of spontaneous remission, we recommend early referral for psychological support if patients begin to exhibit poor cooperation with throat cultures or other routine clinic procedures.

Literature specifically addressing behavioral difficulties in CF patients suggests that maladaptive mealtime behaviors are quite common in infants, toddlers, and school-aged children [14–16]. A 1987 Canadian survey reported that 23% of CF patients 6–11 y demonstrated behavioral maladjustment [17]. A 1991 study [18] examining the relationship between physicians’ and parents’ reports of behavior and adjustment related to the CF treatment regimen found that parents, particularly those of young children, reported behavior difficulties related to medical treatments, such as taking medications and adherence to nutrition and physiotherapy regimens. A 2006 study examined the relationship between treatment barriers and adherence in children with CF aged 6–11 y and found that a greater number of treatment barriers were related to poorer adherence [19]. A 2009 survey of CF caregivers [20] revealed that preschool children demonstrated problems with sleeping, eating and adherence to prescribed physiotherapy regimens.

Early diagnosis and improved survival in CF underscore the need for behavioral interventions to help patients with coping mechanisms, adhering to prescribed therapies, and improving the quality of life [21] and have been shown to be efficacious in chronic pediatric illnesses [22]. The role of pediatric psychology working with the CF care team is pivotal to formally treat adherence and quality of life in patients with CF and to research interventions geared toward these goals.

References

- 1.Grosse SD, Schechter MS, Kulkarni R, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Strickland B, Trevathan E. Models of comprehensive multidisciplinary care for individuals in the United States with genetic disorders. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(1):407–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerem E, Conway S, Elborn S, Heijerman H. Standards of care for patients with cystic fibrosis: a European consensus. J Cyst Fibros. 2005 Mar;4(1):7–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slifer KJ, Babbitt RL, Cataldo MD. Simulation and counterconditioning as adjuncts to pharmacotherapy for invasive pediatric procedures. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1995 Jun;16(3):133–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McComas JJ, Lalli JS, Benavides C. Increasing accuracy and decreasing latency during clean intermittent self-catheterization procedures with young children. J Appl Behav Anal. 1999 Summer;32(2):217–20. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slifer KJ, Cataldo MF, Cataldo MD, Llorente AM, Gerson AC. Behavior analysis of motion control for pediatric neuroimaging. J Appl Behav Anal. 1993 Winter;26(4):469–70. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slifer KJ, Koontz KL, Cataldo MF. Operant-contingency-based preparation of children for functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Appl Behav Anal. 2002 Summer;35(2):191–4. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2002.35-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slifer KJ. A video system to help children cooperate with motion control for radiation treatment without sedation. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1996 Apr;13(2):91–7. doi: 10.1177/104345429601300208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slifer KJ, Bucholtz JD, Cataldo MD. Behavioral training of motion control in young children undergoing radiation treatment without sedation. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1994 Apr;11(2):55–63. doi: 10.1177/104345429401100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slifer KJ, Eischen SE, Busby S. Using counterconditioning to treat behavioural distress during subcutaneous injections in a paediatric rehabilitation patient. Brain Inj. 2002 Oct;16(10):901–16. doi: 10.1080/02699050210131948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Slifer KJ, Eischen SE, Tucker CL, Dahlquist LM, Busby S, Sulc W, et al. Behavioral treatment for child distress during repeated needle sticks. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2002;30(01):57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saiman L, Siegel J. Infection control recommendations for patients with cystic fibrosis: Microbiology, important pathogens, and infection control practices to prevent patient-to-patient transmission. Am J Infect Control. 2003 May;31(3 Suppl):S1–S62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr JE. Recommendations for reporting multiple-baseline designs across participants. Behav Interv. 2005;20(3):219–24. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Catania AC. Learning. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duff AJ, Wolfe SP, Dickson C, Conway SP, Brownlee KG. Feeding behavior problems in children with cystic fibrosis in the UK: prevalence and comparison with healthy controls. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003 Apr;36(4):443–7. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powers SW, Patton SR, Byars KC, Mitchell MJ, Jelalian E, Mulvihill MM, et al. Caloric intake and eating behavior in infants and toddlers with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 2002 May;109(5):e75. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stark LJ, Jelalian E, Powers SW, Mulvihill MM, Opipari LC, Bowen A, et al. Parent and child mealtime behavior in families of children with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr. 2000 Feb;136(2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)70101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons RJ, Corey M, Cowen L, Keenan N, Robertson J, Levison H. Behavioral adjustment of latency age children with cystic fibrosis. Psychosom Med. 1987 May–Jun;49(3):291–301. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders MR, Gravestock FM, Wanstall K, Dunne M. The relationship between children’s treatment-related behaviour problems, age and clinical status in cystic fibrosis. J Paediatr Child Health. 1991 Oct;27(5):290–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1991.tb02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modi AC, Quittner AL. Barriers to treatment adherence for children with cystic fibrosis and asthma: what gets in the way? J Pediatr Psychol. 2006 Sep;31(8):846–58. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ward C, Massie J, Glazner J, Sheehan J, Canterford L, Armstrong D, et al. Problem behaviours and parenting in preschool children with cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 2009 May;94(5):341–7. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.150789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfeffer PE, Pfeffer JM, Hodson ME. The psychosocial and psychiatric side of cystic fibrosis in adolescents and adults. J Cyst Fibros. 2003 Jun;2(2):61–8. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(03)00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beale IL. Scholarly literature review: efficacy of psychological interventions for pediatric chronic illnesses. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006 Jun;31(5):437–51. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]