Abstract

The prospective relationship between initial rumination and subsequent bulimic symptoms, and vice versa, was examined, and possible mediators were tested in a community sample of 191 adolescent girls (M age = 14.5) at 3 different assessment time points. Path analyses indicated that Time 1 rumination predicted Time 3 bulimic symptoms, and vice versa. Physical appearance competence (but not social competence) mediated both relationships. The results suggest that specific cognitive mechanisms, such as rumination, may play an etiological role in the development of bulimic symptoms. This may be especially true for adolescent girls who exhibit low competence beliefs about their physical appearance.

Adolescent girls commonly endorse engaging in behaviors associated with bulimia nervosa (BN) such as binge eating, self-induced vomiting, and abuse of diet pills and/or laxatives (Centers for Disease Control, 2005; Pisetsky, Chao, Dierker, May, & Striegel-Moore, 2008; Smith, Simmons, Flory, Annus, & Hill, 2007). These behaviors are problematic because they are unhealthy, can cause functional impairment, and sometimes develop into clinically significant eating disorders by young adulthood (Fairburn, Cooper, Doll, Norman, & O'Connor, 2000; Lewinsohn, Striegel-Moore, & Seeley, 2000). To prevent BN from developing among adolescent girls, it is important to identify the factors that place certain girls at an elevated risk for the development of bulimic symptoms in the first place.

Certain preadolescent and adolescent risk factors for the development of bulimic pathology (e.g., perceived pressure to be thin, body dissatisfaction, and internalizing the thin ideal; Field, Camargo, Taylor, Berkey, & Colditz, 1999) are well-established; however, they account for a relatively small amount of variance in the prediction of BN (effect sizes .11, .14, and .13, respectively; Stice, 2002). As a result, there is still an urgent need to identify novel risk factors that confer an increased risk for developing BN. A recent prospective study suggested that rumination may play an etiological role in the development of BN (Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007). Rumination is the tendency to focus repetitively on feelings of distress and the possible causes and/or consequences of these feelings without employing active problem solving strategies (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2004). Nolen-Hoeksema et al.'s (2007) study demonstrated that adolescent girls who relied heavily upon a ruminative response style were at an increased risk of developing bulimic pathology over time, and girls who initially had elevated levels of bulimic pathology were at an increased risk of developing subsequent ruminative thought patterns. Although the effect size between Time 1 rumination and Time 2 symptoms of BN was small, the authors succeeded in identifying a novel variable that is relevant to the onset of BN.

Despite the importance of this initial study in demonstrating the longitudinal association between BN and rumination, the authors' did not explore the mechanisms by which bulimic symptoms and rumination may be related but suggested that future researchers do so. Because rumination has been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of developing a range of psychopathology (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008) and interventions are maximally powerful when they target specific mechanisms, a fruitful area of research is one that explores mechanisms that might explain the unique relationship rumination has with bulimic pathology (i.e., instead of the relationship that rumination has with depression).

Which specific mechanism(s) might predict the association between rumination and bulimic symptom development in girls? Perhaps one's perceived competence in domains relevant to eating pathology and associated impairment may explain the link between rumination and bulimic symptom development. Physical appearance competence (i.e., the beliefs one has about her appearance, feelings of satisfaction with one's body; Harter, 1999) is a construct that is closely related to body dissatisfaction, and body dissatisfaction is a well-documented risk factor for BN development (for a review, see Stice, 2002).

Keel, Mitchell, Davis, and Crow (2001) proposed a pathway that may potentially link negative self-concepts, body dissatisfaction, and bulimic symptoms. Specifically, they suggested that the extent to which general dysphoria gets funneled into dissatisfaction with weight or shape may serve as an etiological factor for the development of BN. Girls begin to experience dysphoria and depression at higher rates than boys around adolescence (Hankin, Abramson, Moffitt, Silva, McGee, & Angell, 1998), and also begin to engage more frequently in rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999). Therefore, if Keel et al.'s (2001) hypothesis is correct, it is possible that the link between rumination and BN observed by Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2007) could be explained by a low sense of competence in the physical appearance domain.

Given that the link between rumination and BN has only recently been identified and empirical information about potential mediators is currently lacking, it is important to examine specificity of potential mediators. Therefore, examining another domain of perceived competence that may also be related to bulimic pathology would provide a strong test of specificity for the hypothesized rumination → physical appearance competence → bulimic symptoms pathway. Because interpersonal difficulties may play a role in the emergence of disordered eating (Attie & Brooks-Gunn, 1995; McGrane & Carr, 2002), social perceived competence may be another variable that could explain the link between rumination and bulimic pathology. Social competence refers to how well one functions in relation to other people, particularly with respect to getting along with others and forming close relationships (Harter, 1985). Although social and physical appearance competences are moderately correlated (Marsh, 1989; Smari, Petursdottir, & Porsteinsdo, 2001), gender differences begin to occur in physical appearance competence around age 8, whereas marked stability is observed in social competence from late childhood to adolescence (Masten, Coatsworth, Neemann, Tellegen, & Garmezy, 1995). Therefore, we predicted that social competence would be less likely than physical appearance competence to explain the relationship between rumination and bulimic pathology among adolescent girls. If our hypothesis is supported, specificity for the mediator of physical competence would be obtained.

In the present study, we began by prospectively examining the relationship between bulimic symptoms and rumination from early adolescence to later adolescence in a community sample of girls. Based upon the results of the Nolen-Hoeksema et al. (2007) study, we hypothesized that early bulimic symptoms would predict future increases in subsequent ruminative tendencies, and ruminative tendencies would also predict future increases in bulimic symptoms. We examined girls only because our goal was to replicate and extend the work of Nolen-Hoeksema and colleagues (2007), and those authors investigated this association only in girls. Moreover, the prevalence of bulimic symptoms is markedly higher in girls than boys (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 1994) and early distress may lead to passive, ruminative coping tendencies more often in girls than in boys (Crick & Zahn-Waxler, 2003; Hankin & Abramson, 2001).

We also examined potential mediators of the hypothesized rumination and bulimia link. Based upon Keel et al.'s (2001) prediction that dissatisfaction with physical appearance is a primary factor that may explain the link between dysphoria and bulimic symptoms and the fact that girl's perceived physical competence decreases during late childhood, we hypothesized that physical appearance competence would more strongly mediate the rumination and bulimic symptom relationship among adolescent girls than would social competence. We also hypothesized that the opposite would be true (i.e., an adolescent girl with bulimic symptoms would develop an increasingly poor perception of her physical appearance, which would subsequently lead to increases in rumination).

Method

Participants

Participants were adolescents recruited from five Chicago area schools (N = 350; 57% female). A total of 467 students were available in the appropriate grades (6th–10th) and were invited to participate. Parents of 390 youth (83.5%) provided active consent; all 390 youth were willing to participate and therefore provided assent. Of this group, 356 youth (91% of the 390; 76% of the 467 available students) completed the baseline questionnaire, whereas the remaining 34 were absent from school. We examined data from 350 adolescents who provided complete data at baseline. The age range was 11–17 years (M = 14.5; SD = 1.4). Approximately 53% participants identified themselves as White, 21% as African-American, 13% as Latino, 7% as bi-racial or multi-racial, and 6% as Asian or Pacific Islander. Rates of participation varied slightly at each follow-up assessment: Time 2 (T2; N = 303; 86%) and Time 3 (T3; N = 308; 88%). Youth who participated at Time 1 (T1) but were not present at other time points did not differ significantly on any of the measures from those youth who remained at the other time points. For the present study, only girls were included in analyses: N = 191 at T1, N = 165 at T2, and N = 168 at T3.

Procedures

Permission to conduct this investigation was provided by the school districts and their institutional review boards, and the university institutional review boards at the University of Chicago and the University of Denver. Research team members visited classrooms and briefly described the study to students, and letters describing the study to parents were sent home. Specifically, students and parents were told that this study was about adolescent mood and experiences and would require completion of questionnaires at multiple time points. Written informed consent was required from parents and written assent was required from students.

Participants completed self-report measures at multiple time points (T1 through T3) over a 10-week period, with approximately five weeks between each time point. The spacing for the follow-up intervals was chosen based on past research showing that relatively short-time intervals result in more accurate, less biased recall of symptoms (Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006). Participants were compensated $10 for their participation at each wave in the study. Different measures were given at each of the three time points (T1, T2, and T3), as described below.

Measures

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale (EDDS; Stice, Telch, & Rizvi, 2000)

The EDDS contains items assessing the DSM–IV diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, BN, and binge eating disorder, and responses can be used to generate DSM–IV diagnoses for each of those eating disorders. Items (excluding the height and birth control pill use items) can also be summed to create an overall eating disorder symptom composite. For purposes of this study, items were summed (except for the height/weight, birth control, amenorrhea, and fear of fatness items) to compute a bulimic symptom composite. Internal reliability in this sample for the bulimic symptom composite was good (α = .85). The EDDS has been shown to have high criterion validity when it is compared to the gold standard of eating disorder clinical interviews (i.e., the Eating Disorders Examination; EDE; Fairburn & Cooper, 1993; kappa = .78; Stice, Fischer, & Martinez, 2004). It has also shown high internal consistency when used with adolescent girls (e.g., internal consistency = .89; Stice et al., 2004). The EDDS was administered at all 3 time points.

Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC; Harter, 1985)

Children's perceived competence in two theoretically important domains (i.e., physical appearance and social) was assessed by the multidimensional SPPC. Six items (Likert scale 1–4) were used to assess each of the core constructs: youths' perceived competence in physical appearance and social. Internal reliability in this sample for each domain of competence was: physical appearance α = .85 and social α = .82. Evidence for the validity for the SPPC and the specific domains of competence has been reported in numerous studies (e.g., Harter, 1999). The SPPC was administered at T1 and T2.

Children's Response Style Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002)

The CRSQ, a measure of the constructs featured in RST, is based upon the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). The CRSQ uses 25 items clustered into the three general response styles of rumination, distraction, and problem-solving. Children are asked to rate how frequently they respond to a sad mood with the particular response. The 13-item subscale of rumination was used in this study. Scores on the rumination scale range from 0–39. A higher score indicates a more frequent use of that response style. The scale has been shown to exhibit moderate test-retest stability and possess moderate internal consistency (Abela et al., 2002; Hankin, 2008). Internal reliability in this sample was α = .80 at T1. The CRSQ was given at T1 and T3.

Data Analysis

Based on criteria for testing and establishing mediation (e.g., Baron & Kenny, 1986; Holmbeck, 2002), we used SEM (AMOS 7.0; Arbuckle, 2006) to conduct path analyses. AMOS 7.0 incorporates full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation, which allows for full use of all data, including those with partially missing data. FIML assumes that the data are missing at random, as opposed to missing completely at random as assumed with listwise or pairwise deletion, and can yield robust estimates even when the missing at random assumption is violated (Little & Rubin, 1989; Muthen, Kaplan, & Hollis, 1987). As such, we used FIML to handle the relatively minor missing data resulting from attrition given recommendations by such statistical methodologists (Little & Rubin, 1989; Muthen et al., 1987) to use FIML.

Path analyses were used to examine the hypothesized mediating effects of the physical appearance competence as explaining the longitudinal association between baseline rumination predicting prospective elevations of bulimic symptoms, and vice versa. To test the rumination → physical appearance competence → bulimic symptoms model, we examined the following essential paths: 1) T1 rumination predicts T3 bulimic symptoms, 2) T1 rumination predicts T2 physical appearance competence, 3) T2 competence predicts T3 bulimic symptoms, and 4) the effect of T1 rumination on T3 bulimic symptoms is reduced after including physical appearance competence in the model. In addition, we included measures of the mediating constructs at earlier time points in order to provide a rigorous test of the mediational models and evaluate whether prospective changes in the mediators account for the association between baseline rumination and later elevations in symptoms (see Cole & Maxwell, 2003). In particular, T1 rumination, both social and physical appearance competence at T1, and bulimic symptoms were included to predict change to T2 competence domains, and earlier bulimic symptoms (at T1 and T2) were used to predict prospective changes in T3 bulimic symptoms. Both social and physical appearance domains were included in the same model to examine the hypothesized specificity of physical appearance competence as the mediating mechanism accounting for the longitudinal association between baseline rumination and prospective elevations of bulimic symptoms.

Finally, it is important to note that we used measures of the hypothesized competence domains as mediators and bulimic symptoms at different time points, based on methodological and statistical recommendations (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007) that longitudinal designs with assessments at different, non-overlapping time points provide a more stringent and accurate test of mediation than cross-sectional data. In particular, prior levels of bulimic symptoms (at T1 and T2) were included in the model to predict bulimic symptoms at T3. This was done to ensure that the hypothesized mediator of physical appearance competence at T2 mediated the association of T1 rumination and T3 bulimic symptoms. Thus, the strategy of controlling for prior assessments of the mediators and symptoms as well as including the mediators at non-overlapping time points enabled a more accurate longitudinal examination of the proposed mediational pathways. Most research examining meditational pathways has tended to use either cross-sectional or a 2-time point study design, yet both of those designs conflate variables examined in the mediation analysis of constructs at different hypothesized time points. As such, cross-sectional or 2-time point designs do not provide an appropriate, accurate, and unbiased test of the mediation model because the temporal ordering of the variables at different time points necessarily breaks down (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). As a result, the present design enabled a more rigorous a test of the hypothesized mediation model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations and correlations) of the main variables are presented in Table 1. All variables were significantly associated (small to large effects) with each other in the expected directions. Rumination and bulimic symptoms were positively correlated with each other and were each negatively correlated with the various competence domains.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations among Study Measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social T1 | |||||||||

| 2. Appearance T1 | .27*** | ||||||||

| 3. Rumination T1 | −.16* | −.22** | |||||||

| 4. Bulimia T1 | −.26*** | −.26*** | .17** | ||||||

| 5. Bulimia T2 | −.15** | −.23*** | .15* | .42*** | |||||

| 6. Social T2 | .49*** | .23*** | −.20** | −.25** | −.37*** | ||||

| 7. Appearance T2 | .31*** | .42*** | −.19** | −.41*** | −.53*** | .53*** | |||

| 8. Rumination T3 | −.22*** | −.11 | .21** | .35*** | .30*** | −.22*** | .30*** | ||

| 9. Bulimia T3 | −.32*** | −.24*** | .27*** | .40*** | .51*** | −.51*** | −.30*** | −.29*** | |

| Mean |

2.81 | 2.35 | 14.4 | 3.31 | 3.73 | 2.82 | 2.46 | 16.03 | 4.87 |

| SD | 0.57 | 0.47 | 6.05 | 9.02 | 9.63 | .41 | .57 | 5.55 | 10.29 |

Note. N=191 at Time 1, N=165 at Time 2, and N=168 at Time 3.

Appearance= Physical appearance competence; Social = Social competence; Bulimia = Bulimic symptoms from EDDS.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

At T1, 12.1% (n = 23) of the 191 participants reported engaging in binge eating twice or more each week on average, whereas 26.0% (n = 50) reported using inappropriate compensatory behaviors (i.e., self-induced vomiting, laxative or diuretic abuse, excessive fasting, excessive exercise) at least twice a week on average. According to the EDDS, 6.8% (n = 13) of the sample met full-threshold criteria for BN, and an additional 2.1% (n = 4) met sub-threshold criteria (i.e., they endorsed regular binge eating and regular use of inappropriate compensatory, but at rates that were slightly less than twice per week on average). As discussed in detail later, however, it is important to note that the point prevalence estimate of BN obtained in this sample is notably higher than lifetime rates found in other studies (Stice, Marti, Shaw, & Jaconis, 2009).

Path Analyses of Rumination Leading to Symptoms of Bulimia and Depression

When testing the hypothesis that baseline rumination would predict prospective changes in bulimic symptoms over time, we controlled for the influence of T1 and T2 symptoms to T3 symptoms to enable prospective examination of whether T1 rumination would predict later symptoms of bulimia at T3. After controlling for the influence of T1 (β=. 30, p < .001) and T2 (β=.42, p < .001) bulimic symptoms contributing to bulimic symptoms at T3, T1 rumination predicted T3 bulimic symptoms for adolescent girls (β=.18, p < .001).

Mediational Pathway Analyses to Account for the Association between Rumination and Subsequent Symptoms of Bulimia

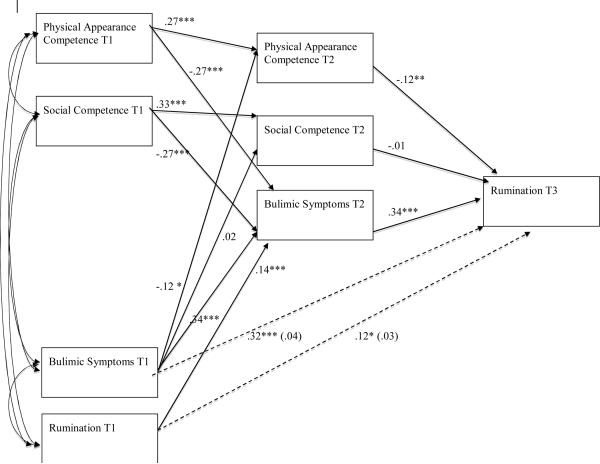

Figure 1 summarizes the results of the mediation model for T1 rumination predicting T3 bulimic symptoms. This model with mediators (χ2 (6) = 4.2, n.s.; CFI = 1.0) provided an excellent fit to the data. The prior analyses demonstrated that T1 rumination predicted prospective elevations of bulimic symptoms at T3, so support for mediation can be seen when the indirect mediational paths are significant and the direct paths from rumination to later symptoms are non-significant.

Figure 1.

Girls' mediation model demonstrating that physical appearance competence fully mediated the link between initial rumination and later elevations in bulimic symptoms.

Consistent with all requirements for mediation, Figure 1 shows that T1 rumination predicted changes in the physical appearance competence domain (β= −.11, p < .05), but not social competence (β = .05, ns), from T1 to T2 after controlling for baseline levels of these competence domains and concurrent levels of bulimic symptoms at T2. Physical appearance competence at T2 predicted prospective changes in bulimic symptoms at T3 (β= −.16, p < .05) after controlling for prior variables at T1 and T2. Importantly for testing specific mediating processes, social competence was not predicted by rumination nor did it predict changes in bulimic symptoms over time. Finally, the association between T1 rumination and T3 bulimic symptoms was no longer significant after including physical appearance competence domain as a mediating factor (β decreased from .18, p < .001 to .09, ns).

Given the fairly wide age range in this sample, multi-group SEM was used to examine whether these significant mediation processes applied equally to early (6th–8th grade) and middle (9th and 10th grade) adolescents or whether these meditational paths were relatively stronger in one age group. Results from the multi-group SEM showed no significant difference by age group, and the pattern and size of effects for the early adolescents was similar to that found with middle adolescents and as shown in Figure 1.

In addition to each of the mediating paths being significant and the association between T1 rumination and T3 bulimic symptoms being non-significant, we used the Sobel test to verify that physical appearance and academic competence significantly mediated the link between baseline rumination and later prospective symptoms of bulimia. The Sobel test was significant for physical appearance competence as mediator (z = 2.29, p < .05). Finally, the inclusion of physical appearance competence in the model reduced the association between baseline rumination and prospective elevations in bulimic symptoms by 50%. Thus, a mediational pathway was supported in which rumination contributed to lowered levels of competence in the physical appearance domain, and in turn less competence in one's physical appearance predicted prospective elevations in girls' bulimic symptoms.

Path Analyses of Bulimic Symptoms Predicting Increases in Rumination

The prior set of analyses examined one direction of influence: rumination predicting subsequent symptoms of bulimia. The following set of analyses investigated the other direction of influence to determine whether initial levels of bulimic symptoms predicted changes in rumination over time for adolescent girls. Similar SEMs were conducted to examine whether T1 bulimic symptoms predicted elevations of rumination at T3. After controlling for the influence of T1 rumination onto T3 rumination (β= .12, p <.05), initial bulimic symptoms predicted T3 rumination (β= .32, p < .001).

Figure 2 summarizes the results of the mediation model for competencies mediating the association of initial bulimic symptoms to later rumination among girls. This model with mediators (χ2 (6) = 4.7, n.s.; CFI = 1.0) fit the data well. The prior analyses demonstrated that T1 bulimic symptoms predicted prospective elevations of rumination at T3, so support for mediation can be seen when the indirect mediational paths are significant and the direct paths from symptoms to later rumination are non-significant. Consistent with all requirements for mediation, T1 bulimic symptoms predicted changes in physical appearance, but not social, competence. In turn, physical appearance competence at T2 predicted prospective changes in rumination at T3 (β= −.12, p <.05) after controlling for prior variables at T1 and T2. Finally, the association between T1 initial bulimic symptoms and T3 rumination was no longer significant after including the physical appearance competence domain as a mediating factor (β decreased from .32, p < .001 to .04, ns). Multi-group SEM with age (early vs. middle adolescents) revealed no significant differences, suggesting that these associations apply equally well to early and middle adolescents.

Figure 2.

Girls' mediation model demonstrating that physical appearance competence fully mediated the link between initial bulimic symptoms and later elevations in rumination

The Sobel test showed that physical appearance competence was a significant mediator (z = 3.58, p < .001) of the link between initial bulimic symptoms and later rumination. Finally, the inclusion of physical appearance competence in the model reduced the link between initial bulimic symptoms and later rumination by 80%. Thus, these analyses provide support for the mediational pathway by which initial bulimic symptoms contribute to lowered levels of competence in the physical appearance domain, and in turn less competence in one's physical appearance predicted prospective elevations in girls' rumination over time.

Discussion

This prospective study examined temporal relationships between rumination and bulimic symptoms, and potential mediators thereof, in an attempt to elucidate cognitive factors relevant to the emergence and maintenance of eating disorders. Our first set of hypotheses was supported, such that a) T1 rumination predicted increased levels of T3 bulimic symptoms among adolescent girls and b) T1 bulimic symptoms predicted increased levels of T3 rumination.

Our second set of hypotheses was also supported. Specifically, physical appearance competence was a partial mediator of the relationship between T1 rumination and T3 bulimic symptoms, and a full mediator of the relationship between T1 bulimic symptoms and T3 rumination, in adolescent girls. Moreover, when entered simultaneously into the models, social competence did not emerge as a mediator; therefore, physical appearance competence appears to be a unique mediator of the relationship between rumination and bulimic symptoms among adolescent girls. Post-hoc analyses indicated that the results held true across the wide age range of our sample, suggesting that physical appearance competence mediates the longitudinal association between rumination and later bulimic symptoms, and vice versa, equally well from early through middle adolescence.

The results of this study provide support for the predictions made by Keel et al. (2001). Specifically, they indicate that when girls experience dysphoria and the rumination that often accompanies it, they are at a relatively high risk of developing bulimic pathology if they also feel unhappy with their body. This is likely because when girls who feel dysphoric become dissatisfied with their physical appearance, they being to ruminate about the shortcomings they perceive their body to have. When the focus of rumination becomes body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms may begin to emerge. This pathway may explain the undue valuation of weight and shape on overall self-worth that is present in individuals with BN (APA, 1994).

Compared to data gathered from 12–19 year old girls in China (Chen & Jackson, 2008) and Hong Kong (Lee et al., 2007), which indicated that only 0.3% and 0.1% of the samples met EDDS criteria for full-threshold BN, respectively, data from our sample of American adolescent girls yielded much higher rates of full-threshold BN (i.e., 6.8%). The differences in rates of full-threshold BN observed in these three samples may represent cultural differences in the frequency of bulimic pathology. It is also noteworthy that the rates of full- and sub-threshold BN suggested by the EDDS in this community sample are slightly higher than rates of BN in similar age groups of American adolescent girls that have been obtained using structured clinical interviews (e.g., 1.6 and 6.1% met criteria for full- and sub-threshold BN by age 20; Stice, Marti, Shaw, & Jaconis, 2009). If our results are replicated, they may suggest that despite reports of diagnostic validity (Stice et al., 2000; 2004), the EDDS may lead to higher rates of BN categorization than a structured clinical interview would.

Strengths and Limitations

The results of this study should be evaluated in light of its strengths and limitations. One limitation of the study was that all data were self-reported. Second, diagnostic clinical levels of BN were not assessed in this study; therefore, it is unknown whether the results of this study (i.e., those that focus on dimensional conceptualizations of symptomatology) would generalize to disorders of clinical significance. Further, rates of BN in our sample, as estimated by the EDDS, were notably higher than lifetime rates that have been found in other studies (Stice et al., 2009). This raises the question of whether the EDDS can validly make diagnostic determinations, and future researchers should consider using better established measures such as the Eating Disorders Examination (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). Third, although the EDDS was given at each of the three time points, the rumination measure was only given at T1 and T3; therefore, T2 levels of rumination could not be controlled for in the path analyses. Finally, the spacing of the prospective intervals (i.e., every 5 weeks) was fairly close in time, so the study provided results over a relatively short time period. Future multi-wave studies can expand on these findings by investigating longer time spans between intervals. Despite this fact, previous studies demonstrated notable changes in bulimic symptoms over a 5 week time period (Vohs, Bardone, Joiner, Abramson, & Heatherton, 1999).

On the other hand, the current study possessed many strengths that are noteworthy. First, the design was a multi-wave, prospective assessment of the constructs of interest. This methodology enabled stronger inferences about the temporal precedence between rumination and bulimic symptoms. Moreover, data analytic methods best suited for multi-wave longitudinal repeated measures data were used. Finally, the community-based sample was relatively racially and ethnically diverse and represented a wide socioeconomic range, as opposed to the predominantly White, middle-class samples used that have been used in most past research on bulimic symptoms.

Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

Within the context of these strengths and limitations, the results of this study suggest that rumination may be a cognitive factor that plays an important role in the development of bulimic symptoms in adolescent girls. Specifically, the current findings suggest that girls who ruminate and then subsequently begin to have lowered competence beliefs about their physical appearance may be at an increased risk for the development of eating disorders when compared to their non-ruminative peers. Because these are new findings, it is important for future researchers to replicate them and expand upon them.

If the findings are replicated by independent research teams, they may be relevant to the prevention and/or early intervention of BN. First, dissonance-based preventions will probably prevent the increase of body dissatisfaction among girls who are already ruminating (Stice, Mazotti, Weibel, & Agras, 2000). Second, clinicians should carefully assess levels of body dissatisfaction when working with adolescent girls who exhibit ruminative response styles, as girls who are ruminators and feel displeased with their physical appearance are more likely to develop bulimic pathology than those who have not become discontent with their body. When rumination and/or body dissatisfaction are noted in adolescent girls, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques will likely be effective treatment strategies (Keel & Haedt, 2008).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by NIMH grants R03-MH 066845 and 5R01 MH077195 to Benjamin L. Hankin.

References

- Abela J, Brozina K, Haigh E. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third and seventh grade children: A short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J. Amos user's guide. Small Waters; Chicago: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Attie I, Brooks-Gunn J. The development of eating regulation across the lifespan. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen D, editors. Developmental Psychopathology. volume 2. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Baron R, Kenny D. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System; Youth Online Comprehensive Results. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Jackson T. Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of eating disorder endorsements among adolescents and young adults from China. European Eating Disorders Review. 2008;16:375–385. doi: 10.1002/erv.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole D, Maxwell S. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N, Zahn-Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Developmental Psychopathology. 2003;15:719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The eating disorder examination. In: Fairburn C, Wilson G, editors. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment. 12th ed. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, Cooper Z, Doll H, Norman P, O'Connor M. The natural course of bulimia nervosas and binge eating disorder in young women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:659–665. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field A, Camargo C, Taylor C, Berkey C, Colditz G. Relation of peer and media influences to the development of purging behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:1184–1189. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin B. Stability of cognitive vulnerabilities to depression: A short-term prospective multi-wave study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:324–333. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin B, Abramson L. Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin B, Abramson L, Moffitt T, Silva P, McGee R, Angell K. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children. University of Denver; 1985. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The Construction of the Self: A Developmental Perspective. The Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck G. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel P, Haedt A. Empirically supported psychosocial interventions for eating disorders and eating problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:39–61. doi: 10.1080/15374410701817832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel P, Mitchell J, Davis T, Crow S. Relationship between depression and body dissatisfaction in women diagnosed with bulimia nervosa. International Journal Eating Disorders. 2001;30:48–56. doi: 10.1002/eat.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Stewart S, Striegel-Moore R, Lee S, Ho S, Lee P, et al. Validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale for use with Hong Kong adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:569–574. doi: 10.1002/eat.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewisohn P, Striegel-Moore R, Seeley J. Epidemiology and natural course of eating disorders in young women from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. Age and sex effects in multiple dimensions of self-concept: Preadolescence to early adulthood. Journal Educational Psychology. 1989;81:417–430. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Coatsworth J, Neemann J, Gest S, Tellegen A, Garmezy N. The structure and coherence of competence from childhood through adolescence. Child Development. 1995;66:1635–1659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell S, Cole D. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrane D, Carr A. Young women at risk for eating disorders: Perceived family dysfunction and parental psychological problems. Family Therapy. 2002;24:385–395. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Kaplan D, Hollis M. On structural equation modeling with data that are not missing completely at random. Psychometrika. 1987;52:431–462. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The response styles theory. In: Papageorgiou C, Wells S, editors. Depressive Rumination: Nature, Theory, and Treatment of Negative Thinking in Depression. Wiley; New York: 2004. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression of depression study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster. Journal Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco B, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisetsky E, Chao Y, Dierker L, May A, Striegel-Moore R. Disordered eating and substance use in high school students: Results from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008;41:464–470. doi: 10.1002/eat.20520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smári J, Pétursdóttir G, Porsteinsdóttir V. Social anxiety and depression in adolescents in relation to perceived competence and situational appraisal. Journal of Adolescence. 2001;24:199–207. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G, Simmons J, Flory K, Annus A, Hill K. Thinness and eating expectancies predict subsequent binge-eating and purging behavior among adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:188–197. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E. Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Fisher M, Martinez E. Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: Additional evidence of reliability and validity. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:60–71. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti C, Shaw H, Jaconis M. An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:587–597. doi: 10.1037/a0016481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Mazotti L, Weibel D, Agras W. Dissonance prevention program decreases thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms: A preliminary experiment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:206–217. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<206::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Telch C, Rizvi S. Development and validation of the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale: A brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:123–131. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vohs KD, Bardone AM, Joiner TE, Abramson LY, Heatherton TF. Perfectionism, perceived weight status, and self-esteem interact to predict bulimic symptoms: A model of bulimic symptom development. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:695–700. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]