Abstract

Cerebral cortex is comprised of regions including six-layer neocortex and three-layer olfactory cortex generated by telencephalic progenitors of an Emx1 lineage. The mechanism specifying region-specific subpopulations within this lineage is unknown. We show in mouse that the LIM homeodomain transcription factor Lhx2, expressed in graded levels by progenitors, determines their regional identity and fate decisions to generate neocortex or olfactory cortex. Emx1-Cre deletion of Lhx2 at E10.5 refates progenitors to generate three-layer cortex phenocopying olfactory cortex rather than lateral neocortex. Progenitors do not generate ectopic olfactory cortex following Lhx2 deletion at E11.5. Thus, Lhx2 regulates a regional-fate decision by telencephalic progenitors during a critical period that closes as they differentiate from neuroepithelial cells to neuronogenic radial glia. “Exposure” of progenitors to Lhx2 may dictate their regional-fate decisions. These findings establish a genetic mechanism determining regional fate in the Emx1 lineage of telencephalic progenitors that generate cerebral cortex.

The mammalian cerebral cortex is comprised of several major regions, including six-layer neocortex and architecturally more simple and phylogenetically older cortices, including three-layer paleocortex, which is predominantly olfactory cortex, i.e. piriform cortex (PC), and archicortex, which is predominantly hippocampal formation1. The great majority of neurons that form each region, including all glutamatergic and projection neurons, arise from progenitors within the ventricular zone of dorsal telencephalon (dTel) of a lineage defined by expression of Emx1, a homeodomain transcription factor expressed by all progenitors within the dTel ventricular zone2. Little progress though has been made on defining mechanisms that determine distinct regional fates within this relatively uniform population of progenitors.

Although expression of Emx1 is a defining characteristic of dTel progenitors, neither expression of Emx1 itself, nor of any transcription factor, has been shown to determine regional fate of progenitors within the Emx1 lineage. Further, the Emx1 progenitor lineage has not been subdivided into distinct populations, or sub-lineages, that generate specific regions of cerebral cortex by their expression of a distinct transcription factor. Indeed, such a relationship between a lineage and a specific region of cerebral cortex might not exist. However, unique subpopulations of progenitors of the Emx1 lineage must generate distinct regions of cerebral cortex and must be specified by their unique expression of one or more transcription factors. The mechanism for specifying regional fate within the Emx1 lineage could have as a key feature the graded expression of a transcription factor that defines though differences in expression levels, unique subpopulations of progenitors. The LIM homeodomain transcription factor Lhx2, which is expressed in all dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage in a high to low caudomedial to rostrolateral graded pattern across the dTel ventricular zone3,4, is a strong candidate for this role.

Lhx2 is a critical regulator of cortical development and may function as a selector gene for cortical identity. For example, analysis of an Lhx2 constitutive knockout shows that cerebral cortex largely fails to form because ventricular zone progenitors become quiescent early in corticogenesis, although some markers associated with PC are detectable5. Further, a patterning center, cortical hem, expands and overpopulates the cortical wall with Cajal-Retzius neurons3,4,6. In addition, clusters of Lhx2 null neurons in dorsomedial neocortex of chimeric mice made from Lhx2 null and wild-type blastula do not express neocortical markers7.

Here we study Lhx2 in specification of regional fate within dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage by addressing the hypothesis that Lhx2 regulates the fate decision within this lineage to produce neocortex or paleocortical PC. Because of severe defects of Lhx2 constitutive knockout mice and their embryonic lethality3, addressing this hypothesis required that we generate a conditional knockout (cKO) of Lhx2. Therefore, we made mice with floxed alleles of Lhx2 and used three different lines of mice expressing Cre recombinase, Emx1-Cre8, Nestin-Cre9 and Nex-Cre10, to delete Lhx2 at different times to assess roles for Lhx2 in specification and fate of dTel progenitors and their progeny that form cerebral cortex. Lhx2 expression begins in forebrain at E8.5 before neurulation, two days before the earliest Cre mediated deletion of floxed alleles4,6 with Emx1-Cre, thus allowing transient expression of Lhx2 in dTel progenitors to promote development of cerebral cortex, which is crucial for our study.

We demonstrate that Lhx2 regulates a fate decision among dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage to generate phylogenetically distinct telencephalic regions, lateral neocortex or paleocortical PC, and is required for progenitors of lateral neocortex and their progeny to acquire a neocortical fate. Lhx2 regulates this fate decision within a critical period that closes with differentiation of neuronogenic radial glia and onset of cortical neurogenesis. These findings establish a genetic mechanism for determining regional fate of dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that generate cerebral cortex.

Results

Neocortical-paleocortical shifts following Lhx2 deletion

Mice with floxed alleles of Lhx2 were generated and initially crossed with an Emx1-Cre line8 to delete Lhx2 from progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that give rise to cerebral cortex (Fig.1). The Lhx2fl/-; Emx1-Cre and Lhx2fl/fl; Emx1-Cre offspring are postnatal viable, exhibit the same phenotype, and are grouped as cKO-E. Five genotypes obtained as littermates from these crosses (Lhx2fl/- without Emx1-Cre or Lhx2fl/+ or Lhx2+/-, with or without Emx1-Cre) have similar phenotypes and are grouped as wild-type.

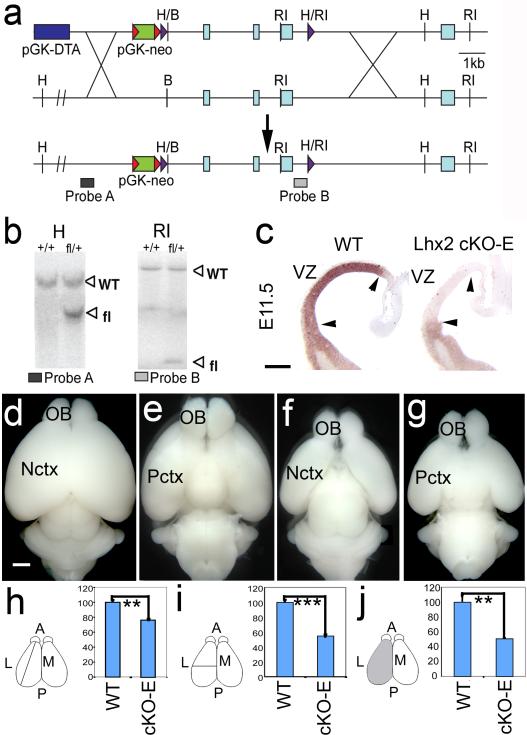

Fig.1. Generation of Lhx2 floxed allele and conditional deletion using Emx1-Cre.

(a) Targeting strategy. Red and purple triangles indicate FRT and LoxP sites. (b) Southern hybridization on wild type (wild-type, +/+) and heterozygous (fl/+) ES cell clones with probes A and B. Genomic DNA digested with HindIII (H3) and hybridized with probe A reveals 10kb wild-type band and 6kb floxed band (fl). Probe B and EcoRI (RI) digestion reveal 15kb wild-type band and 2kb fl band. (c) In situ hybridization for Lhx2 on E11.5 wild-type and cKO-E coronal sections shows selective deletion in dorsal telencephalon (arrowheads) in cKO-E ventricular zone (VZ). Scale bar: 0.2mm. (d,f) Dorsal and (e,g) ventral views of P7 wild-type (d,e) and cKO-E (f,g) brains shows reduced size of cKO-E neocortex (Nctx). (h) Relative neocortical A-P length in wild-type and cKO-E mice. wild-type length mean is set as 100. Compared with wild-type (100±3.14, n=4), length of cKO-E neocortex (76.54±1.20, n=4) is significantly decreased (P<0.01, unpaired Student’s t test). (i) Relative neocortical width (from midline to lateral side). Wild-type width mean is set as 100. Compared with wild-type (100±3.44, n=4), neocortical width of cKO-E (54.83±1.98, n=4) is significantly decreased (P<0.001). (j) Relative dorsal surface area of cerebral hemisphere. Wild-type surface area mean is set as 100. Compared with wild-type (100±9.88, n=4), cKO-E surface area (50.75 ±1.06, n=4) is significantly decreased (P<0.01). Scale bar: 0.5mm. A, anterior; L, lateral; M, medial; OB, olfactory bulb; P, posterior; Pctx, paleocortex; error bars=s.e.m.; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.0001.

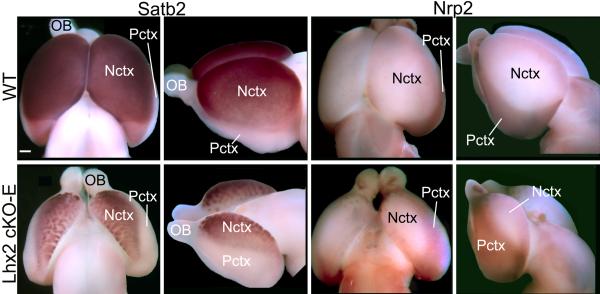

To examine regional patterning of telencephalon deficient for Lhx2, we performed at P0 whole mount in situ hybridization with a neocortical marker, Satb211, and a paleocortical marker, Nrp212. In wild-type, Satb2 marks the dorsal-dorsolateral surface of the cortical hemisphere, and Nrp2 marks in a complementary fashion the ventral-ventrolateral surface (Fig.2). In cKO-E, the telencephalon is smaller and exhibits aberrant patterning. The Satb2 domain is substantially reduced, with its ventrolateral border shifted dorsally, and is striped due to diminished staining of cell sparse domains that alternate with cell dense domains in superficial layers (Fig.2). The Nrp2 domain exhibits a parallel change to the Satb2 domain, shifting dorsally to retain its complementary expression pattern with Satb2 (Fig.2). Thus, deletion of Lhx2 from progenitors of the Emx1 lineage results in a significant change in telencephalic patterning, with an expansion of paleocortical markers and a restriction of neocortical markers.

Fig.2. Complementary changes in neocortical and paleocortical domains in cerebral cortex of cKO-E mice following Lhx2 deletion by Emx1-Cre.

Whole mount in situ hybridization on P0 wild-type (Lhx2fl/+:Emx1-Cre) and Lhx2 cKO-E (Lhx2fl/-:Emx1-Cre) brains using the neocortex (Nctx) marker Satb2 and the paleocortex (Pctx) marker Nrp2 shown in dorsal (rostral to the top) and side (rostral to the left) views. Compared to wild-type, in the Lhx2 cKO-E, the Satb2 expression domain is reduced in size and its ventral border shifts dorsally in the cortical hemisphere, complemented by an expansion and dorsal shift of the Nrp2 expression domain. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. OB, olfactory bulb.

We performed a marker analysis to assess the integrity and positioning of cortical hem, a caudomedial patterning center13, the pallium-subpallium boundary (PSB), and anti-hem, a putative ventrolateral patterning center coincident with PSB14, and find that each form in cKO-E similar to wild-type (Supplementary Fig.1). Further, expression of the transcription factors Dlx2, Dlx5, Gsx2 (Gsh2), Ascl1 (Mash1), and Arx implicated in specifying fates of neurons generated in the LGE15-18, a prominent germinal zone of ventral telencephalon contiguous to the dTel ventricular zone, remain limited to the LGE (Supplementary Fig.2). Thus, effects of Lhx2 on neocortical versus paleocortical fate are likely a direct influence of Lhx2 on dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage.

Ectopic PC forms following Lhx2 deletion from Emx1 lineage

To determine the outcome of expansion of the paleocortical marker Nrp2 observed at P0 on underlying telencephalic patterning, we focused analyses on P7, when laminar organization of cerebral cortex is mature. Nissl staining and in situ hybridization were performed on sections of P7 wild-type and cKO-E littermates using Nrp212 and neocortical markers Satb2 and EphB611,19 (Fig.3). Because Nrp2 marks the contiguous olfactory cortical structures, PC and olfactory tubercle, to distinguish PC we selected Slc6a720 and Ppfibp1 (Liprinβ1)21 from the Allen Brain Atlas (http://www.brain-map.org) and BGEM (http://www.stjudebgem.org) and confirmed that each marks PC and distinguishes it from olfactory tubercle and adjacent neocortex (Fig.3).

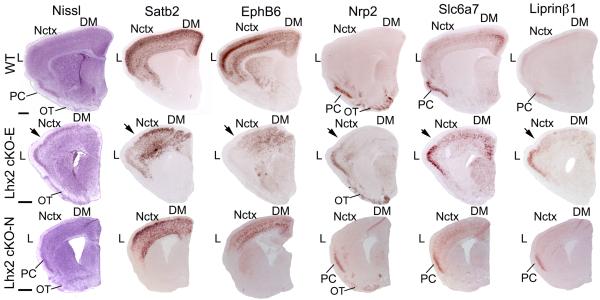

Fig.3. Altered patterns of regional telencephalic markers demonstrate a refating of lateral neocortex into piriform cortex following Lhx2 deletion with Emx1-Cre but not Nestin-Cre.

Nissl staining and in situ hybridization for neocortex (Nctx) markers, Satb2 and EphB6, the paleocortex marker Nrp2 and the piriform cortex (PC) markers Slc6a7 and Liprinβ1 on coronal sections of P7 wild-type (Lhx2fl/+), Lhx2 cKO-E (Lhx2fl/-;Emx1-Cre) and Lhx2 cKO-N (Lhx2fl/-N;Nestin-Cre) brains. In wild-type, Satb2 and EphB6 are expressed in both dorsomedial (DM) and lateral (L) neocortex while Nrp2 is expressed in PC and olfactory tubercle (OT), Slc6a7 and Liprinβ1 are expressed specifically in PC. In wild-type, PC is located ventrally in the cortical hemisphere. In Lhx2 cKO-E mice, high level of expression of Satb2 and EphB6 is only detected in dorsomedial neocortex but not in lateral neocortex; instead, lateral neocortex exhibits ectopic Nrp2, Slc6a7 and Liprinβ1 expression coincident with the ectopic three-layer PC seen in the Nissl staining. The transition between these two patterns in dorsomedial and lateral neocortex is marked with an arrow. In Lhx2 cKO-N mice, Nrp2, Slc6a7 and Liprinβ1 label wild-type PC that is located ventrally whereas lateral neocortex is strongly labeled by Satb2 and EphB6, as in wild-type. In Lhx2 cKO-E mice, Satb2 expression persists throughout the ePC in place of lateral neocortex, although at substantially diminished levels relative to lateral neocortex in wild-type and to dorsomedial neocortex in Lhx2 cKO-E mice. Satb2 expression is not detected in wild-type PC. Scale bar: 0.5 mm.

Compared to wild-type, neocortex of cKO-E is reduced in size, and has two distinct, aberrant lamination patterns. In dorsomedial neocortex of cKO-E, both neocortical markers, Satb2 and EphB6, exhibit a roughly wild-type-like expression pattern and Nrp2 is largely absent (Fig.3). In contrast, within lateral neocortex, expression of Satb2 and EphB6 is diminished and replaced by robust expression of Nrp2 and six-layer architecture characteristic of neocortex is replaced by a three-layer architecture resembling PC (Fig.3). In addition, this ectopic Nrp2 domain expresses PC markers Slc6a7 and Liprinβ1 that distinguish it from the Nrp2-positive olfactory tubercle (Fig.3), thereby identifying this aberrant structure positioned in lateral neocortex as an ectopic PC (ePC). In contrast, the Nrp2-positive three-layer cortical structure ventral to ePC is not marked by either Slc6a7 or Liprinβ1, identifying it as olfactory tubercle (Fig.3). Thus, following conditional deletion of Lhx2 using Emx1-Cre, lateral neocortex is replaced by a cortical structure that has the architecture and marker expression of PC, and a wild type PC (wtPC) is not identified at its normal ventral position. These findings strongly suggest that progenitors that normally generate lateral neocortex are refated to generate PC following deletion of Lhx2 using Emx1-Cre.

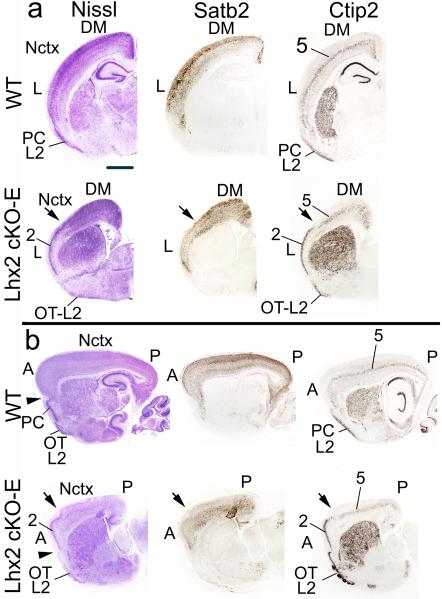

Additional marker analyses using immunostaining assessed expression of Bcl11b (Ctip2) relative to Satb2 at P7 (Fig.4). In wild-type, Ctip2 is preferentially expressed by layer 5 neurons within neocortex, whereas within PC and olfactory tubercle it strongly labels layer 222. In cKO-E, Ctip2 is expressed in layer 2 of ePC, coincident with expression of the paleocortical marker Nrp2 (Fig.4), while retaining a wild-type-like expression pattern in dorsomedial neocortex, coincident with expression of the neocortical marker Satb2 (Fig.4). Although Satb2 expression in ePC is significantly lower than in wild-type neocortex or in dorsomedial neocortex of cKO-E, its expression nonetheless persists throughout ePC whereas its expression is non-detectable in wtPC (Figs.3 and 4). EphB6 expression is though reduced to non-detectable levels in ePC. In conclusion, maintained, albeit significantly reduced, expression of the neocortical marker Satb2 in ePC is strong evidence that it is indeed generated by progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that would normally generate lateral neocortex but following deletion of Lhx2 are refated to generate PC.

Fig.4. Distinct expression patterns of Ctip2 and Satb2 in Lhx2 cKO-E telencephalon indicate that lateral neocortex is refated into piriform cortex.

Nissl and immunostaining of adjacent coronal (a) and sagittal (b) sections from P7 wild-type and Lhx2 cKO-E brains with Satb2, a neocortex (Nctx) marker, and Ctip2, a neocortical layer 5 and paleocortical layer 2 marker. (a) In wild-type, Ctip2 is expressed in neocortical layer 5 (5) and in layer 2 of piriform cortex (PC-L2), and Satb2 is robustly expressed in neocortex. Satb2 expression is strongly diminished in lateral neocortex (L) of Lhx2 cKO-E compared to wild-type, coincident with the change from six-layer neocortex to three-layer architecture of ectopic PC; Ctip2 is expressed in layer 5 of dorsomedial neocortex (DM), layer 2 of ectopic PC (2) and layer 2 of olfactory tubercle (OT-L2). The transition between these patterns in dorsomedial and lateral neocortex is marked with an arrow. (b) In sagittal sections of Lhx2 cKO-E mice, anterior (A) neocortex exhibits aberrant three-layer cytoarchitecture of ectopic PC, and posterior (P) neocortex resembles six-layer cytoarchitecture observed dorsomedially in coronal sections. In Lhx2 cKO-E mice, Satb2 and Ctip2 exhibit expression patterns appropriate for neocortex posteriorly and for PC anteriorly, coincident with cytoarchitecture change. The transition between these two patterns is marked with an arrow. Satb2 expression persists in ePC, albeit at reduced levels, but is not expressed in wild-type PC. The ectopic PC is positioned dorsal to rhinal fissure (arrowhead). Scale bars: a: 0.1 mm; b: 0.2 mm.

To further determine the degree of refating, we analyzed connectivity of ePC in P7 cKO-E, and find that it receives afferent input from olfactory bulb to layers 1 and 3 as in wtPC23. However, in contrast to wild-type, in cKO-E the olfactory bulb projection continues beyond ePC and aberrantly projects within layer 1 throughout much of neocortex (Fig.5), consistent with lateral neocortex being refated into ePC and the gradual transitioning of ePC into neocortex.

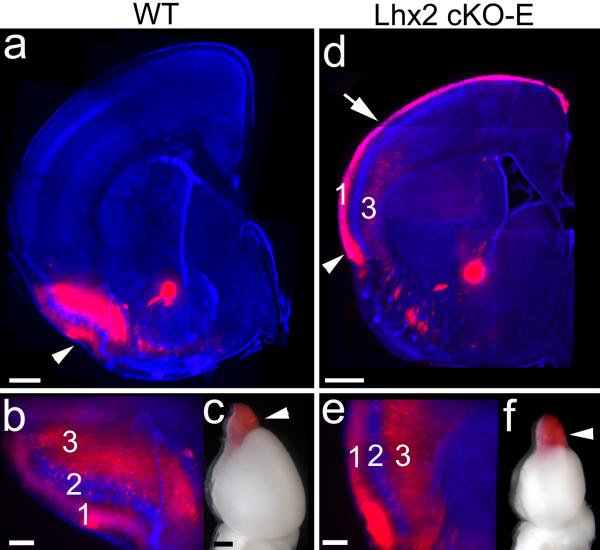

Fig.5. The ectopic piriform cortex in lateral neocortex of Lhx2 cKO-E mice receives input from olfactory bulb similar to piriform cortex in wild-type.

Coronal sections of P7 wild-type (a,b; Lhx2fl/-) and Lhx2 cKO-E (d,e; Lhx2fl/-;Emx1-Cre) brains in which the axon tracer DiI (red) was placed in the olfactory bulb (arrowhead in c, f) to label its axonal projection through the lateral olfactory tract to layers 1 and 3 of piriform cortex (PC). Sections are counterstained with DAPI (blue). (a) In wild-type, olfactory bulb axons form the lateral olfactory tract (arrowhead) and project to PC. (b) Higher magnification of the region near the arrowhead in panel a showing the terminations of olfactory bulb axons mainly in layers 1 and 3. (d) In Lhx2 cKO-E mice, the presumptive lateral olfactory tract (arrowhead) shifts dorsally and the axonal projection from olfactory bulb terminates in the ectopic PC in lateral neocortex (its dorsal border is marked by an arrow). The olfactory bulb projection aberrantly extends through layer 1 of the neocortex, but is restricted to the ectopic PC in layer 3. (e) Higher magnification of the region near the arrowhead in panel d showing the terminations of olfactory bulb axons mainly in layers 1 and 3 in the ectopic PC in Lhx2 cKO-E mice, as in wild-type. Scale bars: 0.5mm in a and d, 0.2 mm in b and e, and 0.5 mm in c and f.

Wild type PC is absent in Lhx2 cKO-E mice

Although we identify in P7 cKO-E, an Nrp2-positive, three-layer olfactory cortical structure ventral to ePC, it does not express PC-specific markers and is identified as olfactory tubercle. This lack of an identifiable PC at its normal ventral position could be due to either its failure to express PC-specific markers following deletion of Lhx2, or that wtPC is not present. To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed an Emx1 lineage analysis by crossing the Emx1-Cre line to the ROSA26 reporter line24 on wild-type and floxed Lhx2 mutant backgrounds, permanently labeling all cells of the Emx1 lineage with β-galactosidase (β-gal).

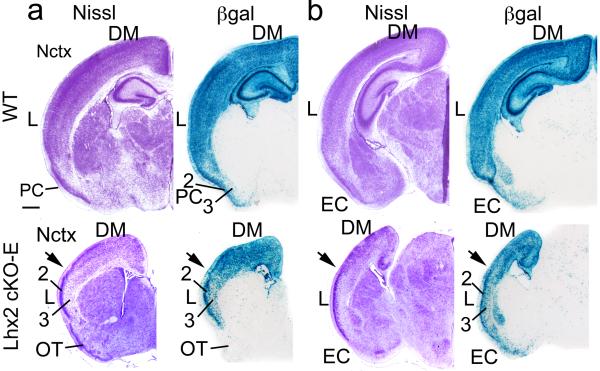

In P7 wild-type, neocortex and PC are well labeled by β-gal (Fig.6). The density of β-gal labeling parallels neuronal density revealed by Nissl staining, confirming that neocortex and PC are formed predominantly by neurons of the Emx1 lineage. In contrast, few β-gal labeled cells are found in olfactory tubercle (Fig.6), indicating that it is derived from lineages other than Emx1. In P7 cKO-E, dorsomedial neocortex is heavily labeled by β-gal as is ePC in the location normally occupied by lateral neocortex; in both, the density of labeled cells mirrors that observed in adjacent Nissl stained sections, as in wild-type (Fig.6a). At caudal positions, beyond the normal A-P extent of PC in wild-type, the β-gal labeled entorhinal cortex is ventral to lateral neocortex, whereas in cKO-E, the β-gal labeled entorhinal cortex is ventral to ePC positioned in lateral neocortex (Fig.6b). At more rostral levels, where PC is found in wild-type, we do not find a β-gal labeled structure ventral to β-gal labeled ePC positioned in lateral neocortex; instead, this ventral position is occupied by β-gal negative olfactory tubercle. These findings confirm that wtPC is not present at its normal ventral position in cKO-E at P7, and the only PC-like structure is ePC positioned in lateral neocortex.

Fig.6. The ectopic piriform cortex located in the lateral neocortex in Lhx2 cKO-E mice is generated by an Emx1 lineage, whereas wild-type piriform cortex is not evident.

(a,b) Nissl and β-gal staining on adjacent coronal sections of P7 wild-type (Lhx2fl/+:Emx1-Cre:R26R) and Lhx2 cKO-E (Lhx2fl/-:Emx1-Cre:R26R) brains at two different levels (a, anterior; b, posterior). Blue cells are β-gal labeled and are of the Emx1 lineage; the density of the β-gal labeling patterns parallel the neuronal density revealed by Nissl staining. In wild-type, the entire six-layer neocortex (Nctx) is labeled by β-gal. In three-layer piriform cortex (PC), layer 2 is intensely labeled and layer 3 has scattered labeled cells. In Lhx2 cKO-E mice, the neocortex is also well labeled by β-gal. In dorsomedial neocortex (DM), the six cortical layers are all labeled, and in the ectopic PC in lateral neocortex (L), layer 2 is intensely labeled and layer 3 shows sparse labeling, consistent with the density of neurons shown by Nissl staining and with β-gal labeling in wild-type PC. The transition between the six-layer and three-layer patterns in dorsomedial neocortex and lateral neocortex (i.e. ectopic PC), respectively, is marked with an arrow. Scale bar: 0.5 mm. EC, entorhinal cortex; OT, olfactory tubercle.

Ectopic PC in Lhx2 cKO-E mice is not wtPC shifted dorsally

The most straightforward interpretation of our findings in cKO-E is that progenitors that generate lateral neocortex are refated due to Lhx2 deletion to generate neurons of PC fate rather than neocortical fate. Alternatively, due to reduced size of cortex in cKO-E, wtPC shifts dorsally to an ectopic position normally occupied by lateral neocortex. Arguing against this alternative is positioning of ePC relative to the rhinal fissure, a sulcus that is constant across mammalian species and separates neocortex located dorsal to it from paleocortical PC located ventral to it25. In wild-type, PC is positioned ventral to the rhinal fissure, whereas in cKO-E, ePC is positioned dorsal to the rhinal fissure, where lateral neocortex is found in wild-type (Supplementary Fig.3; Fig.4). This finding is consistent with ePC being produced by progenitors that are part of the pool of neocortical progenitors, albeit refated due to Lhx2 deletion, that continues to generate neurons that form a continuous sheet of cells distinct from wtPC.

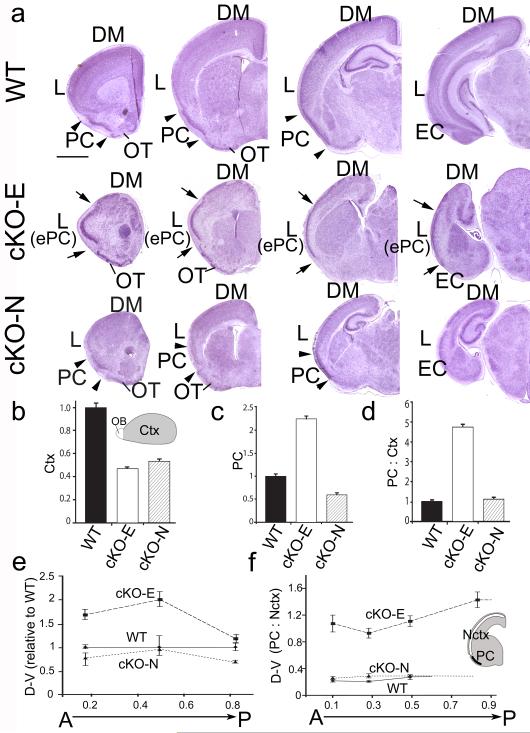

Although positioning of ePC relative to the rhinal fissure makes it virtually inconceivable that ePC is actually wtPC that has shifted dorsally, we nonetheless directly addressed whether ectopic positioning of PC dorsal to the rhinal fissure is the result of reduced cortical size. To test this hypothesis, we crossed floxed-Lhx2 mice with a Nestin-Cre line9 and analyzed telencephalic patterning in offspring, termed cKO-N (Fig.3). At P7, cortices of cKO-E and cKO-N are similar in size, both being approximately half the size of wild-type (Fig.7a, b). However, in contrast to cKO-E, in cKO-N, PC identified by expression of the paleocortical marker Nrp2 and PC-specific markers, Slc6a7 and Liprinβ1 (Fig.3), is positioned ventrally similar to wtPC; in addition, lateral neocortex is also normally positioned and has a six-layer architecture (Figs.3 and 7). These findings refute the possibility that the exaggerated dorsal position of ePC above the rhinal fissure in cKO-E is a secondary result of reduced cortical size.

Fig.7. Size and extent of ectopic PC in cKO-E mice and PC in wild-type and cKO-N mice.

(a) Nissl staining of anterior (left) to posterior (right) coronal sections of P7 wild-type (WT) and brains with Lhx2 deleted by Emx1-Cre (cKO-E) or Nestin-Cre (cKO-N). PC in wild-type and cKO-N (arrowheads) and ectopic PC (ePC) in cKO-E (arrows) are marked. DM, L: dorsomedial, lateral neocortex. (b-f) Plots of features indicated: cKO data normalized to mean of measured feature in wild-type set as 1. (b) Surface area of cerebral cortex (Ctx). cKO-E (n=4, P<0.001, unpaired Student’s t-test) and cKO-N areas (n=2, P<0.001) are smaller than wild-type (n=8). (c) PC size. cKO-E ePC (n=4) is larger (P<0.001) and cKO-N PC (n=3) is smaller (P<0.001) than wtPC (n=6). (d) Ratio of PC size to cortical size (PC:Ctx). ePC:Ctx in cKO-E (n=4) is larger (P<0.001) than PC:Ctx in wild-type (n=6) and cKO-N (n=3). (e) D-V length of PC at positions along A-P extent of PC. cKO-N PC (n=3) is smaller than wtPC (n=6); cKO-E ePC (n=4) larger than both (P<0.001). (f) D-V length of PC relative to neocortex (PC:Nctx) at positions along cortical A-P axis. In wild-type and cKO-N, PC is limited to rostral 60% and 79% of cortical A-P axis; cKO-E ePC is found along entire extent. ePC:Nctx in cKO-E (n=4) is greater than PC:Nctx in wild-type (n=6) or cKO-N (n=3)(P<0.001), which are similar. Scale bar: 0.5 mm; error bars=s.e.m.; EC, entorhinal cortex; OB, olfactory bulb; OT, olfactory tubercle.

Ectopic PC is significantly larger than wild-type PC

An additional argument that ePC is generated, in large part if not entirely, by refated neocortical progenitors is based upon its position relative to wtPC and lateral neocortex, and that it is significantly larger than PC in wild-type (Fig.7). First, ePC in cKO-E is not only positioned dorsal to the rhinal fissure, at the location of lateral neocortex in wild-type, but further, ePC is found at the location of lateral neocortex along the entire A-P extent of neocortex, including well posterior to the normal extent of PC in wild-type, covering essentially 100% of the A-P cortical axis. In contrast, wtPC is limited to the rostral 60% of the A-P cortical axis in wild-type and 79% in cKO-N (Fig.7a, f). Further, ePC is significantly longer along the D-V telencephalic axis than wtPC in either wild-type or cKO-N (Fig.7a, e, f). At each A-P position, ePC is proportionally larger than wtPC and accounts for between 50% and 60% of the D-V cortical axis in cKO-E whereas PC in both wild-type and cKO-N accounts for 25% or less (Fig.7f). The absolute D-V extent of ePC in cKO-E is also greater than wtPC, with ePC being up to 200% of the absolute D-V extent of wtPC (Fig.7a, e). Further, ePC size relative to neocortex is more than 400% greater in cKO-E than PC size relative to neocortex in wild-type (Fig.7d); even in absolute total area, ePC is over twice the size of wtPC (Fig.7c).

These findings can only be explained by one of two mechanisms. The best fit is that ePC is generated by refated progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that would normally generate lateral neocortex. The only alternative requires that progenitors that normally generate PC, which are localized to dTel PSB26, undergo a substantial increase in proliferation in cKO-E to generate the larger ePC, coupled with an aberrantly quiescent population of progenitors that would normally generate lateral neocortex. However, this mechanism is infeasible as we find no evidence for substantial changes in distribution and relative densities of active progenitors using BrdU-pulse labeling during neurogenesis at E11.5, E13.5 and E15.5 (Supplementary Fig.4).

Wild-type PC is formed then eliminated in Lhx2 cKO-E mice

To provide definitive evidence that progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that normally generate lateral neocortex are refated to generate an ePC in cKO-E, we addressed the fate of wtPC neurons in cKO-E by extending to embryonic and perinatal ages the Emx1 lineage analysis described above for P7. For this, the Emx1-Cre and ROSA26 reporter lines were crossed and offspring analyzed on wild-type and cKO-E backgrounds.

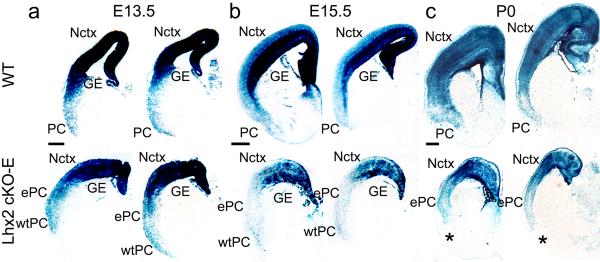

In E13.5 and E15.5 wild-type embryos, both neocortex and PC positioned ventral to it, are formed by a high density of neurons labeled with β-gal indicative of progeny of progenitors of the Emx1 lineage (Fig.8). In E13.5 cKO-E, the distribution, number and density of β-gal labeled neurons closely resemble those in E13.5 wild-type littermates, with both neocortex and PC readily identified at their normal positions (Fig.8a). The wtPC remains evident at E15.5 in cKO-E at its normal ventral position, but the density of β-gal labeled neurons is reduced compared to E15.5 wild-type littermates as well as two days earlier in E13.5 cKO-E (Fig.8b). Consistent with identifying this ventrally located PC in cKO-E being wtPC, it is positioned at the ventral-most location of the migrational scaffold between the dTel ventricular zone and the cortical wall formed by the Fabp7 (BLBP) positive processes of radial glia—the progenitors of the Emx1 lineage. At this ventral-most position, a particularly dense bundle of the radial glial processes form a palisade that connects the ventricular zone of the PSB to the telencephalic wall27 in cKO-E as in wild-type and forms a migrational guide for wtPC neurons (Supplementary Fig.5).

Fig.8. Wild type piriform cortex is generated and forms at appropriate ventral position in Lhx2 cKO-E mice but is subsequently eliminated.

β-gal staining on coronal sections of E13.5 (a), E15.5 (b) and P0 (c) wild-type (Lhx2fl/+:Emx1-Cre:R26R) and Lhx2 cKO-E (Lhx2fl/-:Emx1-Cre:R26R) brains at two different levels (left, anterior; right, posterior). Blue cells are labeled by β-gal defining the as cells of the Emx1 lineage that form the cerebral cortex, including neocortex (Nctx) and piriform cortex (PC). (a) At E13.5, in both wild-type and Lhx2 cKO-E mice, the neocortex and PC, as well as other regions of cerebral cortex, have a high density of β-gal labeled neurons. In Lhx2 cKO-E mice, both the ectopic PC (ePC) and the wild-type PC (wtPC) are evident. (b) At E15.5, in wild-type, the distribution and density of β-gal labeled neurons is similar to E13.5. However, in Lhx2 cKO-E, a reduction in the number and density of β-gal labeled neurons is evident in the wtPC, whereas the neocortex, especially the ventricular zone, remains strongly labeled by β-gal. (c) At P0, the wtPC is no longer evident in the Lhx2 cKO-E mice, but remains well labeled in wild-type. The position where the wtPC should be positioned if present in the Lhx2 cKO-E mice is marked by an *; dorsal to this position, the ePC can be identified by the patterned distribution of β-gal labeled cells. Scale bar: 0.2 mm in a; 0.5mm in b and c. GE, ganglionic eminence.

Elimination of β-gal labeled wtPC neurons continues over the next few days such that by P0 (Fig.8c), as at P7 (Fig.6), wtPC is no longer identifiable in cKO-E. Because this method of lineage tracing permanently marks PC neurons observed at E13.5 in both wild-type and cKO-E, the only possible explanation for the early presence of a PC at its normal ventral position and later absence in cKO-E is that wtPC is generated and formed but is subsequently eliminated. Crossing floxed-Lhx2 mice with a Nex-Cre line of mice that deletes floxed alleles from post-mitotic neurons immediately after generation10, shows that elimination of wtPC in cKO-E is due to a defect resulting from deletion of Lhx2 from dTel progenitors that is inherited by PC neurons (Supplementary Fig.6). These results then, interpreted in context of other findings, provide conclusive evidence that ePC observed at P7 in cKO-E at the position of lateral neocortex is not wtPC that has aberrantly shifted dorsal to the rhinal fissure and instead must be generated by progenitors of the Emx1 lineage normally fated to generate lateral neocortex, but following deletion of Lhx2 by Emx1-Cre, are refated to generate PC.

Critical period for Lhx2 regulation of regional fate

Unlike cKO-E, cKO-N do not form an ePC in place of lateral neocortex, and instead have a PC that resembles wtPC in size and position. Since Emx1 and Nestin drivers both produce Cre expression in all progenitors of the Emx1 lineage within the dTel ventricular zone, this difference in phenotype must be due to differences in timing of Cre expression and recombination. Indeed, recombination produced by Emx1-Cre mice is not detectable at E9.5 but is robust at E10.5, whereas recombination produced by Nestin-Cre mice is not detectable at E10.5 but is robust at E11.5 (Supplementary Fig.7). Thus, the Nestin-Cre line used here produces recombination one day later than the Emx1-Cre line. These findings define a critical period for Lhx2 regulation of the fate decision to generate lateral neocortical neurons or PC neurons exhibited by dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage, characterized by restriction in this fate decision occurring between E10.5 and E11.5.

Defining this critical period leads to predictions based upon the rostrolateral to caudomedial temporal gradient of corticogenesis across the neocortical axes28. We predict a transition zone between neocortex and ePC, characterized by mixing of neurons with neocortical and PC properties in a radial traverse at the medial edge of ePC at a location along the temporal neurogenic gradient where timing of Cre mediated deletion of Lhx2 from progenitors straddles the critical period. To address this issue, we analyzed expression of the neocortical marker Satb2 relative to Ctip2, which marks layer 5 of neocortex but layer 2 of PC (Fig.4). The predicted transition zone is indeed observed (Supplementary Fig.8) providing further evidence of a critical period for Lhx2 regulation of regional fate by progenitors of the Emx1 lineage.

Genetic changes in dTel progenitors in Lhx2 cKO mice

To begin assessing the genetic hierarchy that accounts for refating of cortical progenitors following early Lhx2 deletion, we analyzed in dTel ventricular zone expression of Emx1, Pax6 and Neurog2 (Ngn2), transcription factors involved in cell specification and patterning in forebrain29,30. Because progenitors of the Emx1 lineage exhibit a fate change in cKO-E but not in cKO-N, transcription factors that exhibit unique changes in cKO-E are candidates for prominent involvement in the fate decision. However, each transcription factor analyzed exhibits similar down-regulation in both cKO-E and cKO-N mice (Supplementary Fig.9), indicating that they are unlikely to have an instructive role in mediating the neocortical versus PC fate decision.

Discussion

We show that Lhx2 regulates a genetic mechanism intrinsic to dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that determines their regional fate in generating cerebral cortex. Following Lhx2 deletion at E10.5 by Emx1-Cre, the cortical hemisphere is reduced to half of wild-type size in cKO-E offspring, and neocortex exhibits two position-dependent and continuous architectures: dorsomedially neocortex has six-layer architecture that resembles wild-type neocortex albeit with localized laminar defects, which transitions laterally into a three-layer structure that phenocopies the architecture, marker expression and connectivity of PC. This ePC is considerably larger than wtPC and develops at the location of lateral neocortex along the entire A-P extent of the cortical hemisphere, extending well beyond the A-P extent of wtPC. Lineage tracing shows that wtPC itself is also generated and forms at its normal position ventral to neocortex, but is subsequently eliminated. Multiple experiments summarized in Supplementary Fig.10 provide conclusive evidence that ePC is generated by dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage normally fated to generate lateral neocortex, but are refated following early deletion of Lhx2 to generate PC.

Use of Nestin-Cre results in deletion of Lhx2 at E11.5, one day after Emx1-Cre, and cKO-N offspring have a reduced cortical size similar to that produced by Emx1-Cre. However, cKO-N do not develop an ePC and instead have a uniform neocortex with six-layer architecture that resembles wild-type neocortex, and a PC of normal size and viability at the appropriate wild-type location ventral to lateral neocortex. These distinct phenotypes exhibited by Lhx2 cKOs produced by Emx1-Cre and Nestin-Cre reveal a critical period for Lhx2 regulation of the fate decision made by progenitors of the Emx1 lineage to generate neocortex or paleocortical PC, and that closing of the critical period, characterized by a restriction in regional fate of these progenitors, occurs between E10.5 and E11.5.

Mechanisms for determining regional fates in Emx1 lineage

Cerebral cortex is a hierarchically patterned structure divided anatomically and functionally into specialized regions, which in turn are divided into anatomically and functionally distinct areas that serve unique modalities1. Neocortical areas are specified through the action of transcription factors expressed in graded patterns along the A-P and D-V cortical axes29. For example, area patterning of neocortex is regulated in part by the homeodomain transcription factor Emx2, with the expression level of Emx2 in particular being a critical determinant of area identity of a progenitor in the neocortical ventricular zone31.

The mechanism for determining regional fate of cerebral cortex by Lhx2 may be similar to determining areal fate of neocortex by Emx2, as both are expressed in a high caudomedial to low rostrolateral gradient and act on dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage. Although we have not demonstrated that the graded feature of Lhx2 expression is an important determinant for regulating regional fate amongst dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage, it is likely because in wild-type, the position-dependent level of Lhx2 expression is the feature that distinguishes progenitors of lateral neocortex from those that generate PC. Lhx2 could act by either repressing PC fate or inducing PC fate over a specific range of expression. Our findings suggest that either PC is the default regional fate for lateral neocortical progenitors following deletion of Lhx2 on E10.5, or that a progenitor’s regional fate is determined by its “exposure” (E) to Lhx2, which is the product of exposure time (eT) and expression level (eL), with the exposure experienced by lateral neocortical progenitors following Lhx2 deletion on E10.5 (Emx1-Cre) to be PC fate, and with an extra day of exposure (Nestin-Cre) to be neocortical fate.

Implications for critical period and cortical evolution

The difference in timing of Lhx2 deletion between cKO-E and cKO-N, and their different phenotypes, reveal a critical period for Lhx2 regulation of the fate decision to generate neocortical or PC neurons exhibited by dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage and that closing of the critical period occurs between E10.5 and E11.5. Timing of this regional fate restriction is coincident with onset of cortical neurogenesis32, which itself is determined by significant differentiation of cortical progenitors, specifically transition of neuroepithelial cells into neuronogenic radial glia33. Timing of the critical period for Lhx2 function in regulating regional fate indicates that determination of regional fate is made by neuroepithelial cells and is plastic during their stage of symmetric divisions, but becomes restricted with their transition into radial glia and the asymmetric division stage. A recent study of regulation of this transition period of progenitor differentiation shows that area fates exhibited by dTel progenitors that generate neocortex are determined in neuroepithelial cells and become fixed prior to their differentiation into radial glia34. Our findings here suggest that the critical period for regional fate of cerebral cortex also correlates with timing of neuroepithelial cell to radial glia transition, suggesting that the critical periods for regional fate and areal fate are similar.

Progenitors that give rise to dorsomedial and lateral neocortex exhibit a substantial difference in their retention of neocortical properties versus refating into olfactory cortical progenitors following early deletion of Lhx2 by Emx1-Cre. This difference may be due to the two neocortical domains having different critical periods, with dorsomedial neocortex being earlier than lateral neocortex, or alternatively may be due to a significant genetic distinction between progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that give rise to dorsomedial versus lateral neocortex. Determining whether progenitors of dorsomedial neocortex exhibit an earlier critical period will distinguish between these two alternatives. However, presently we do not have a Cre line that would delete Lhx2 at an age earlier than Emx1-Cre and still result in a viable mouse with an intact cerebral cortex.

Our findings support classic models of cortical evolution that have fallen out of favor. For example, a dual origin model postulates that paleocortex contributes to lateral neocortex and archicortex to dorsomedial neocortex, which is supported by our findings in cKO-E mice that lateral neocortex refates into paleocortical PC, whereas dorsomedial neocortex retains a neocortical-like fate. Our findings also support a model that both PC and neocortex have evolved from ventrolateral telencephalon1,35-37, specifically, our findings that dTel progenitors of the Emx1 lineage that generate PC and neocortex are genetically almost identical, at least as neuroepithelial cells prior to their fate restriction, with only the expression level of Lhx2 functionally distinguishing them. Thus, Lhx2 specification of regional fate of cerebral cortex serves a critical role not only during development, but likely also during evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Berta Higgins and Haydee Gutierrez for technical assistance, Yasushi Nakagawa for help with screening for Lhx2 genomic DNA, Kevin Jones for Emx1-Cre mice, Klaus-Armin Nave for Nex-Cre mice and Philippe M. Soriano for ROSA26-LacZ reporter mice. Supported by grants from NIH to D.O’L.

Appendix

METHODS

Gene targeting, generation and use of mice

The Lhx2 gene targeting was done using homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells (ES cells). A replacement targeting vector was designed to delete the first three exons of the Lhx2 gene including the transcription start site, and replace them with a neomycin-resistance gene (PGK-neo) flanked by two FRT sites. We used DTA (Diphtheria Toxin) under control of the phosphoglycerate kinase promoter (PGK) to select against random insertion events. Targeted ES cell clones were screened by Southern with probes A and B (Supplementary Fig.1), and by PCR, (for the neo cassette: P3: 5′-ATGCCTGCTTGCCGAATATC-3′, P5: 5′-CCCATAAAGAGATGTACACC-3′; for the second LoxP site: P7: 5′-CTTTAACCATGCCGACGTGG-3′, P8: 5′-GAGAGGCAAACCAAAGGCAAC-3′) and identified as Lhx2flox-neo/+clones. These clones were subsequently injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts and the resulting chimeras were then mated to C57Bl/6J females to obtain germ line transmission. Heterozygous mice (Lhx2flox-neo/+) were mated with FLPe mice38 to remove the neo cassette. Homozygous floxed mice (Lhx2fl/fl) were generated by crossing heterozygous animals and genotyping was performed by PCR using the P7 and P8 primers. Lhx2fl/fl mice were mated to Emx1-IRES-Cre mice8 generously provided by Kevin Jones, Nestin-Cre transgenic mice9 (obtained from the Jackson Laboratory) and Nex-Cre mice10 generously provided by Klaus-Armin Nave. Double heterozygous Lhx2fl/+;Emx1-Cre,Lhx2fl/+;Nestin-Cre and Lhx2fl/+;Nex-Cre mice were viable and fertile. For the staging of embryos, midday of the day of the vaginal plug was considered as embryonic day (E) 0.5, and the day of birth is termed postnatal day (P) 0.

All experiments, generation and use of mice for these studies were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines and have been approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the Salk Institute.

In Situ Hybridization

Antisense RNA probes for Arx, Bmp7, Dlx2, Dlx5, Emx1, EphB6, Er81, Gsh2, Liprinβ1, Lhx2, Mash1, Ngn2, Nrp2, Pax6, Satb2, Sfrp2, Slc6a7 and Wnt3a, were labeled using a DIG-RNA labeling kit (Roche). In situ hybridization on 16-20μm cryostat sections and whole-mount in situ hybridization were performed as previously described39.

Immunostaining and Axonal tracing

Mice were perfused with cold 4% buffered paraformaldehyde (PFA) or Bouin fixative. For Nissl staining, 10-20 μm-thick sections were stained with 0.5% cresyl violet, and then dehydrated through graded alcohols. The antibodies used in this study are: rabbit anti-Satb2 (kindly provided by Victor Tarabykin), mouse anti-Satb2 (Abcam), rabbit anti-BLBP (Abcam), rabbit anti-Bc11b (Ctip2, Novus Biologicals) and rat anti-BrdU (Accurate Chemical & Scientific). For immunostaining, 10-20 μm-thick sections (cryostat and paraffin) were developed following the standard DAB (di-amino-benzidine) colorimetric reaction (Vectastain, Vector). For immunofluorescence, a FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody and a Cy3-conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson) were used. DiI (1,1′-dioctadecyl 3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate; Molecular Probes) tracing of olfactory bulb projections was done as previously described39. Crystals of the fluorescent carbocyanide dyes were inserted in the olfactory bulbs, and brains were incubated for 3 to 12 weeks in 4% PFA. The brains were embedded in 5% low melting agarose, cut into 100μm-thick coronal sections on a vibratome, counterstained with DAPI (4′-6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole), mounted in 0.1M phosphate buffer and photographed under fluorescent light. Each tracing experiment was repeated at least three times and shows reproducible results.

Footnotes

The authors declare no financial gain or conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sanides F. Comparative architectonics of the neocortex of mammals and their evolutionary interpretation. Ann N.Y. Acad Sci. 1969:405–423. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop KM, Rubenstein JLR, O’Leary DDM. Distinct actions of Emx1, Emx2, and Pax6 in regulating the specification of areas in the developing neocortex. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7627–38. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07627.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter FD, et al. Lhx2, a LIM homeobox gene, is required for eye, forebrain, and definitive erythrocyte development. Development. 1997;124:2935–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulchand S, Grove EA, Porter FD, Tole S. LIM-homeodomain gene Lhx2 regulates the formation of the cortical hem. Mech Dev. 2001;100:165–75. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(00)00515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vyas A, Saha B, Lai E, Tole S. Paleocortex is specified in mice in which dorsal telencephalic patterning is severely disrupted. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:545–53. doi: 10.1002/cne.10900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monuki ES, Porter FD, Walsh CA. Patterning of the dorsal telencephalon and cerebral cortex by a roof plate-Lhx2 pathway. Neuron. 2001;32:591–604. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00504-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangale VS, et al. Lhx2 selector activity specifies cortical identity and suppresses hippocampal organizer fate. Science. 2008;319:304–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1151695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorski JA, et al. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6309–14. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06309.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graus-Porta D, et al. Beta1-class integrins regulate the development of laminae and folia in the cerebral and cerebellar cortex. Neuron. 2001;31:367–79. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goebbels S, et al. Genetic targeting of principal neurons in neocortex and hippocampus of NEX-Cre mice. Genesis. 2006;44:611–21. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britanova O, et al. Satb2 is a postmitotic determinant for upper-layer neuron specification in the neocortex. Neuron. 2008;57:378–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen H, Chedotal A, He Z, Goodman CS, Tessier-Lavigne M. Neuropilin-2, a novel member of the neuropilin family, is a high affinity receptor for the semaphorins Sema E and Sema IV but not Sema III. Neuron. 1997;19:547–59. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80371-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grove EA, Tole S, Limon J, Yip L, Ragsdale CW. The hem of the embryonic cerebral cortex is defined by the expression of multiple Wnt genes and is compromised in Gli3-deficient mice. Development. 1998;125:2315–25. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Assimacopoulos S, Grove EA, Ragsdale CW. Identification of a Pax6-dependent epidermal growth factor family signaling source at the lateral edge of the embryonic cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6399–403. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06399.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson S, Mione M, Yun K, Rubenstein JLR. Differential origins of neocortical projection and local circuit neurons: role of Dlx genes in neocortical interneuronogenesis. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:646–54. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casarosa S, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 regulates neurogenesis in the ventral telencephalon. Development. 1999;126:525–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colombo E, Galli R, Cossu G, Gecz J, Broccoli V. Mouse orthologue of ARX, a gene mutated in several X-linked forms of mental retardation and epilepsy, is a marker of adult neural stem cells and forebrain GABAergic neurons. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:631–9. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yun K, Garel S, Fischman S, Rubenstein JLR. Patterning of the lateral ganglionic eminence by the Gsh1 and Gsh2 homeobox genes regulates striatal and olfactory bulb histogenesis and the growth of axons through the basal ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 2003;461:151–65. doi: 10.1002/cne.10685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuoka H, Obama H, Kelly ML, Matsui T, Nakamoto M. Biphasic functions of the kinase-defective Ephb6 receptor in cell adhesion and migration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29355–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500010200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoglund PJ, Adzic D, Scicluna SJ, Lindblom J, Fredriksson R. The repertoire of solute carriers of family 6: identification of new human and rodent genes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:175–89. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kriajevska M, et al. Liprin beta 1, a member of the family of LAR transmembrane tyrosine phosphatase-interacting proteins, is a new target for the metastasis-associated protein S100A4 (Mts1) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5229–35. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110976200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leid M, et al. CTIP1 and CTIP2 are differentially expressed during mouse embryogenesis. Gene Expr Patterns. 2004;4:733–9. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shipley MT, Adamek GD. The connections of the mouse olfactory bulb: a study using orthograde and retrograde transport of wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res Bull. 1984;12:669–88. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–1. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ariens-Kappers CU, Huber GC, Crosby EC. The comparative anatomy of the nervous system of vertebrates including man. Macmillan Co.; New York: 1936. ed. Co, M. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carney RS, Cocas LA, Hirata T, Mansfield K, Corbin JG. Differential regulation of telencephalic pallial-subpallial boundary patterning by pax6 and gsh2. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:745–59. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirata T, et al. Mosaic development of the olfactory cortex with Pax6-dependent and - independent components. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;136:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00304-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayer SA, Altman J. Neocortical Development. Raven Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Leary DDM, Chou SJ, Sahara S. Area patterning of the mammalian cortex. Neuron. 2007;56:252–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuurmans C, et al. Sequential phases of cortical specification involve Neurogenin-dependent and -independent pathways. Embo J. 2004;23:2892–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamasaki T, Leingartner A, Ringstedt T, O’Leary DDM. EMX2 regulates sizes and positioning of the primary sensory and motor areas in neocortex by direct specification of cortical progenitors. Neuron. 2004;43:359–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caviness VS., Jr. Neocortical histogenesis in normal and reeler mice: a developmental study based upon [3H]thymidine autoradiography. Brain Res. 1982;256:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(82)90141-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotz M, Huttner WB. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:777–88. doi: 10.1038/nrm1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sahara S, O’Leary DDM. Fgf10 regulates transition period of cortical stem cell differentiation to radial glia controlling generation of neurons and basal progenitors. Neuron. 2009;63:48–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abbie AA. Cortical lamination in a poloprodont marsupial, Perameles natusa. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1942;76:509–536. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ulinkski PS. Dorsal Ventricular Ridge: a treatise on forebrain organization in reptiles and birds. Wiley; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aboitiz F, Montiel J, Morales D, Concha M. Evolutionary divergence of the reptilian and the mammalian brains: considerations on connectivity and development. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:141–53. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez CI, et al. High-efficiency deleter mice show that FLPe is an alternative to Cre-loxP. Nat Genet. 2000;25:139–40. doi: 10.1038/75973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armentano M, et al. COUP-TFI regulates the balance of cortical patterning between frontal/motor and sensory areas. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1277–86. doi: 10.1038/nn1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.