Abstract

Objectives

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are risk factors for health problems later in life. This study aims to 1) assess the influence of ACEs on risky health behaviors among mothers-to-be, and 2) determine whether a dose response occurs between ACEs and risky behaviors.

Methods

Prospective survey of women attending health centers conducted at the first prenatal care visit, and 3 and 11 months postpartum. Surveys obtained information on maternal sociodemographic and health characteristics, and 7 ACEs prior to age 16. Risky behaviors included smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use and other illicit drug use during pregnancy.

Results

Our sample (n=1,476) consisted of low-income (mean annual personal income: $8272), young (mean age: 24 yrs), African American (71%), single (75%) women.

Twenty-three percent of women reported smoking even after finding out they were pregnant, 7% reported alcohol use, and 7% reported illicit drug use during pregnancy. Nearly three-fourths (71%) had one or more ACE(s). There was a higher prevalence of each risky behavior among those exposed to each ACE than among those unexposed. The exception was alcohol use during pregnancy where there was not an increased risk among those exposed when compared to those unexposed to witnessing a shooting or having a guardian in trouble with the law or in jail. The adjusted odds ratio for each risky behavior was greater than 2.5 for those with ≥ 3 ACEs when compared to those without.

Conclusions

ACEs were associated with risky health behaviors reported by mothers-to-be. Greater efforts should target the prevention of ACEs to lower the risk for adverse health behaviors that have serious consequences for adults and their children.

Keywords: risky health behaviors, smoking in pregnancy, adverse childhood experiences, childhood adversity

Introduction

Tobacco, alcohol, and drug use are risky health behaviors that often begin in adolescence and early adulthood. These behaviors share many of the same risk factors including the following adverse childhood experiences: physical abuse, sexual abuse, domestic violence, parental substance abuse, lack of parental involvement, single-parent household, young maternal age, homelessness, and poverty.1-8 Risky health behaviors often cluster, with individuals reporting one behavior also being more likely to report other behaviors.6, 7, 9

The well-described, direct consequences of tobacco smoking include an increased risk for chronic lung disease, lung cancer, thrombotic events, and coronary artery disease.10-12 Alcohol and illicit drug use have adverse health consequences for affected individuals including an increased risk of homicide, suicide, motor vehicle accidents, and impaired family and peer relationships.13-15

The negative effects of risky health behaviors extend beyond health risks to the individual. Tobacco smoking during pregnancy increases the risk of fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, stillbirth, perinatal mortality, and behavioral problems.16-19 For women of childbearing age, alcohol and illicit drug use may impact the women directly, but also have significant impact on their children directly during fetal life and after birth. In utero exposure to alcohol or illicit drugs is associated with congenital defects, intrauterine growth retardation, low birthweight, preterm birth, cognitive deficits, and behavioral problems.20, 21 Increasingly, policy makers and investigators, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, are stressing the importance of addressing alcohol and drug use not only during pregnancy but also during the preconception period,22-27 because it is often too late to counsel against these risk factors and their teratogenic effects by the time women seek prenatal care.26 A recent Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) found high rates of alcohol use preconception, with 50% of women reporting use.27 As much as 40% of women do not realize they are pregnant until at least 4 weeks gestation, and approximately half of all births are unplanned, making the preconception period are particularly important time for counseling.28, 29

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention was one of the first studies to assess ACEs and their cumulative impact on a number of health outcomes and risky health behaviors, including smoking, early alcohol use, and drug abuse.9, 30-32 Subsequent to the ACE Study, there has been a growing literature on early life experiences and their relationship with health conditions and behaviors.33, 34 The ACE Study has major strengths including its large sample size, its findings, and its influence on research and health policy. The ACE Study is limited, however, by use of a retrospective, self-administered survey and the population studied: 46% of participants were ≥ 60 years at the time of the survey, 75% were Caucasian, >75% of participants had completed some or more college education, and all were insured by Kaiser Permanente.9

This study was conducted with the following objectives: 1) to assess the influence of ACEs on risky health behaviors among low-income, expectant mothers, and 2) to determine if there is a dose response associated with cumulative ACEs and the risk of adverse health behaviors. We hypothesized that ACEs are associated with risky health behaviors – smoking, alcohol use, marijuana use, and other illicit drug use during pregnancy. The study below contributes to the existing literature on early life experiences and risky health behaviors by focusing on low-income, urban mothers-to-be.

Methods

The study is part of a larger prospective cohort study on maternal stress, birth outcomes and infant health. The original cohort consisted of women who received prenatal care at health centers in Philadelphia, PA, and who were recruited consecutively from February 2000 to November 2002. These health centers consisted of Federally Qualified Health Center Look Alikes (FQHC-LAs) and FQHCs and have been described previously.35 The ability to speak English or Spanish and having an intrauterine pregnancy were the two major enrollment criteria. This research was approved by the Thomas Jefferson University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Drexel University institutional review boards.

For this study, we use data from three surveys. The first survey was administered to women at their first prenatal care visit (mean gestational age ± standard deviation = 13.8 ± 6.3 weeks), and the second and the third were respectively conducted at 3 ± 1 months and 11 ± 1 months postpartum in their homes. Among the 2,374 eligible women, 42 declined participation, 190 had an unknown birth outcome, and 158 had a miscarriage, abortion, ectopic pregnancy or stillbirth. The remaining 1,984 women were known to have a live birth and completed the prenatal interview, and both postpartum surveys were completed by 1,482 (75%) women. Of the outstanding 502 participants, 126 moved, 129 refused to participate, 28 were excluded because they were unable to participate or no longer lived with their child, 10 had children who died, and 209 did not complete the postpartum interviews. Six additional women who completed the postpartum surveys were dropped from the study due to missing information for a final sample of 1,476 women. When compared to the final sample of 1,476, the 508 women, who lacked or had incomplete postpartum information, did not differ with respect to education, marital status, and parity; however, they were slightly older, more likely to be Latina and less likely to be white, and more likely to have lower annual personal income (data not shown). Trained female interviewers surveyed the women using standardized questionnaires in either English or Spanish. Maternal sociodemographic characteristics were assessed in the initial prenatal interview. Risky health behaviors were assessed in the first two surveys. Childhood experiences, prior to the age of 16, were assessed by 32 items in the third survey at 11 ± 1 months postpartum.

Study Variables

The dependent variables consisted of four risky health behaviors. Smoking in pregnancy, assessed in the prenatal survey, was defined as an affirmative response to the question, “After you found out that you were pregnant this time, have you smoked at all?” Alcohol, marijuana and other illicit drug use were assessed during the second survey. Alcohol use during pregnancy was defined any “beer, wine, 40's, coolers, liquor, or other alcoholic beverages when you were pregnant with [CHILD]?” Marijuana use during pregnancy was defined as any “marijuana, pot, joints or blunts when you were pregnant with [CHILD]?” Other illicit drug use during pregnancy was defined as any “other drugs, such as cocaine, heroine, crack, crank, LSD, uppers, downers, or similar drugs you can get on the street when you were pregnant with [CHILD]?”

Independent variables consisted of sociodemographic variables and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). The following sociodemographic characteristics were obtained prenatally: maternal age, education, race/ethnicity, marital status, and annual personal income.

ACEs, based on events occurring before age 16, consisted of 7 variables: physical abuse, sexual abuse, verbal hostility, domestic violence, having witnessed a shooting, having a guardian in trouble with the law or in jail, and having a guardian with substance use. All questions were preceded by the clause, “Before you were 16 years old…”

Measures that overlapped with the ACE Study included assessments of verbal hostility, physical and sexual abuse, household violence, household substance abuse, and a household member being incarcerated. Measures differed from the ACE Study in that the 7 ACEs were assessed before age 16, whereas the 10 ACEs in the ACE Study were assessed before age 18. The ACE Study, however, assessed living with household members that were substance abusers or incarcerated rather than specifying substance abuse in or incarceration of a parent or guardian. ACE Study variables not assessed were emotional and physical neglect (measured in less than 50% of the ACE Study sample), household mental illness, and parental separation or divorce. One measured variable not found in the ACE Study was witnessing a shooting.

The seven ACE variables used in our study were defined as follows: (1) Physical abuse was defined by “rarely, sometimes, or often” as opposed to “never” to a combination of survey items, separated below by semicolons, and summarized by, “How often did you experience slapping you in the face; punching, pushing, kicking, or beating you with fists; hitting you with an object such as a belt, spoon; or burning you with an object such as a cigarette or iron by the person or people who raised you when you did something wrong?” Spanking was a separate question not included in our analysis. (2) Sexual abuse was based on a confirmatory answer to the question, “Were you ever sexually abused? (3) Verbal hostility was defined by “often” as opposed to “sometimes, rarely or never” to the question, “How often did you experience yelling by the person or people who raised you when you did something wrong?” We believe that considering “sometimes or rarely” yelling as “verbally hostile” would overestimate verbal hostility.

(4) Domestic violence was based on an affirmative answer to, “Was anyone in your house being hit or beaten up?” In the ACE Study, “mother treated violently” was measured rather than any “domestic violence.” (5) Witnessing a shooting was based on an affirmative response to, “Did you ever see someone get shot?” (6) Having a guardian in trouble with the law or in jail was based on an affirmative answer to two items summarized by, “Did your main parent/guardian ever have trouble with the law or ever spend any time in jail?” (7) Having a guardian with substance use was based on an affirmative answer to the question, “Did your main parent/guardian ever have a drug or alcohol problem?

Statistical Analyses

Frequencies were calculated for categorical variables while means, medians and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables. For each participant, we totaled the number of ACEs to create a summary score, which ranged from 0 to 7. Due to the low prevalence of reported illicit drug use other than marijuana during pregnancy (2%), marijuana use was combined with other drug use to record any illicit drug use in pregnancy. Bivariate analyses were performed comparing the prevalence of each of the risky health behaviors among those with and without each of the ACEs, using the Chi-square test for categorical variables and the Student's t test for continuous variables to test for statistical significance.

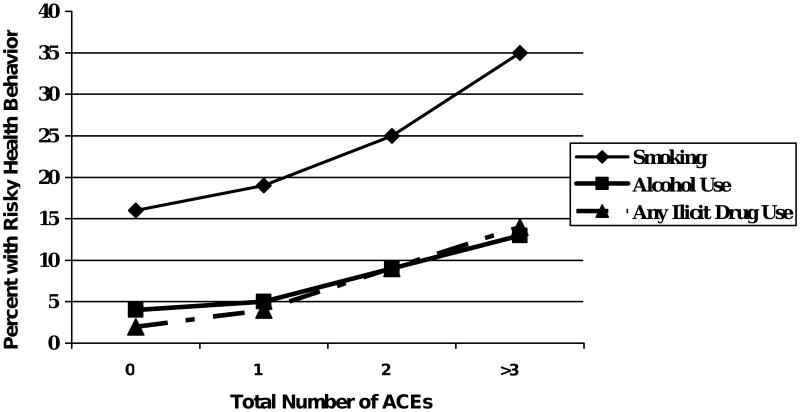

In addition, bivariate analyses were performed to determine if there was a dose response for each risky health behavior based on the total number of ACEs. For increasing ACEs, there was a plateau effect for the risky behaviors after ACEs reached 3 or more; therefore, we combined those with 3 or more ACES into a category of “3 or more.” Collapsing the higher categories also increased the number of subjects in cells of 2 × 2 comparison tables and increased the strength of comparisons between groups.

For each dependent variable – smoking, alcohol and any illicit drug use during pregnancy -- further analyses were performed to adjust for confounding variables. For each of the dependent variables, we conducted a logistic regression analysis to adjust for potential confounding variables and to derive maximum likelihood estimates of combined relative odds with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Risk factors and confounders for inclusion in our final models were identified a priori based on our review of the literature, which is summarized above. Each of the models contained the following independent variables: age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, annual personal income, and total ACEs. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of fit χ2 statistic was calculated for each final model to assess model fit.36

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics and the overall prevalence of risky health behaviors are shown in Table 1. The sample largely consisted of young, African American, low-income, single women of low education. Twenty-three percent of women reported smoking even after finding out they were pregnant, 7% reported alcohol use, and 7% reported illicit drug use during pregnancy. Of those reporting any illicit drug use, 5% reported any marijuana use, 2% other illicit drugs, and 1% reported marijuana and other illicit drug use.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Prevalence of Risky Health Behaviors for Overall Study Population (N = 1,476).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | |

| Maternal age, y, mean ± SD | 24 +/- 6 |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Less than high school | 590 (40) |

| High School/ GED* | 620 (42) |

| College or more | 266 (18) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| African American | 1048 (71) |

| Latina | 251 (17) |

| White | 133 (9) |

| Other | 44 (3) |

| Marital Status, Single, n (%) | 1107 (75) |

| Annual Personal Income, n (%) | |

| <$6450 | 738 (50) |

| $6450 - $11 758 | 369 (25) |

| >$11 758 | 369 (25) |

| Risky Health Behaviors, n (%) | |

| Smoking in Pregnancy | 334 (23) |

| Alcohol Use in Pregnancy | 99 (7) |

| Any Illicit Drug Use in Pregnancy | 97 (7) |

| Marijuana Use | 80 (5) |

| Other Illicit Drug Use | 27 (2) |

| Marijuana and Drug Use | 10 (1) |

GED indicates General Educational Development certificate.

Table 2 shows the overall prevalence for the individual and total ACEs. More than half of our sample reported a history of childhood physical abuse. For each of the other 6 ACEs, more than 10% of the sample was represented. The majority (72%) of participants had at least one ACE, and 21% reported three or more ACEs.

Table 2. Prevalence of Individual and Cumulative Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) for the Study Population (N = 1,476).

| Adverse Childhood Experiences | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Individual Adverse Childhood Experience | |

| Physical Abuse | 763 (52) |

| Sexual Abuse | 188 (13) |

| Verbal Hostility | 398 (27) |

| Domestic Violence | 198 (13) |

| Witnessed a Shooting | 272 (18) |

| Guardian in Trouble with the Law or in Jail | 157 (11) |

| Guardian with Substance Use | 249 (17) |

| Total Adverse Childhood Experiences | |

| 0 | 421 (28) |

| 1 | 440 (30) |

| 2 | 303 (21) |

| ≥3 | 308 (21) |

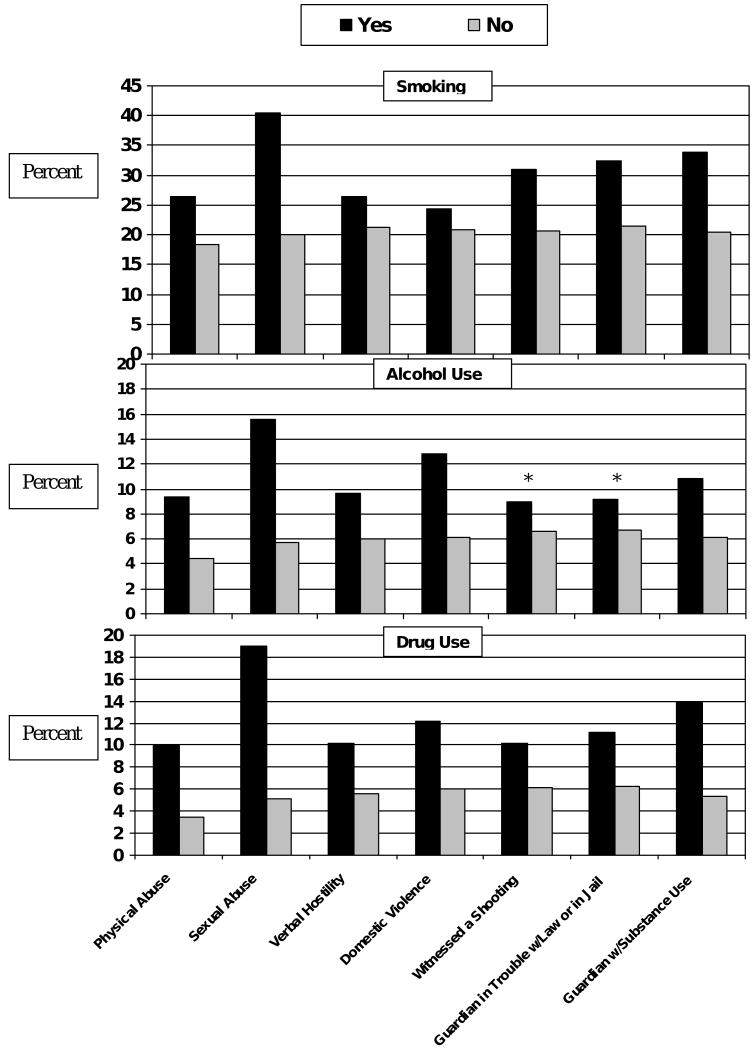

Figure 1 shows that those exposed to each ACE when compared to those unexposed had higher prevalence rates of each risky health behavior. The prevalence of each of the risky health behaviors was highest among those who experienced childhood sexual abuse suggesting that this is a particularly strong predictor of risky health behaviors. Using the Chi-square test for all comparisons, the p-value was <0.05 except for alcohol use among those witnessing a shooting or among those with a guardian in trouble with the law or in jail when compared to those without these experiences. The higher the number of total ACEs, the higher the prevalence of each risky health behavior, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Comparison between the Prevalence of Risky Behaviors among Those Exposed and Those Not Exposed to Adverse Childhood Experiences (N =1,476)

* All difference were significant at or below the 0.05 level except there were no significant differences in alcohol use among those witnessing a shooting or among those with a guardian in trouble with the law when compared to those without these experiences.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Risky Health Behaviors during Pregnancy and Total Number of ACEs.

In Table 3, adjusted odds ratios are shown for each independent variable. Older women were at a slightly higher risk for smoking, alcohol use, and any illicit drug use during pregnancy. In this low-income, urban sample, non-white race/ethnicity was associated with lower risks of the risky health behaviors when compared to white race/ethnicity. Single mothers were more likely to report smoking during pregnancy than married women. Women with less than a high school education had four times the risk of smoking during pregnancy and over twice the risk of illicit drug use during pregnancy than those with more than high school education. Consistent with bivariate analyses, a dose response was noted for each risky behavior. Those with three or more ACEs had over 2.5 times the risk of smoking, alcohol use, and any illicit drug use during pregnancy when compared to women who reported no ACEs. The multivariate logistic regression models for smoking, alcohol use, and any illicit drug use during pregnancy, were respectively associated with Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 statistics of 6.49 (P = 0.59), 7.59 (P = 0.47), and 5.25 (P = 0.73), suggesting a good fit for each of the models.

Table 3. Adjusted Odds Ratios (aORs) from Models Predicting Smoking, Alcohol Use, and Any Illicit Drug Use during Pregnancy (N= 1,418).

| Variable | Smoking aOR (95% CI) | Alcohol Use aOR (95% CI) | Any Illicit Drug Use aOR (95% CI) | p-value for comparison of aORs across models |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age (continuous variable) | 1.11 (1.08, 1.13) | 1.10 (1.07, 1.14) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 0.361 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 0.19 (0.13, 0.29) | 0.37 (0.21, 0.65) | 0.52 (0.29, 0.93) | 0.008 |

| Latina | 0.10 (0.06, 0.17) | 0.35 (0.16, 0.77) | 0.24 (0.10, 0.61) | 0.017 |

| Caucasian | Reference | Reference | Reference | --- |

| Other | 0.13 (0.05, 0.38) | 0.35 (0.07, 1.64) | 0.24 (0.03, 1.93) | 0.595 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.44 (1.01, 2.07) | 1.43 (0.81, 2.52) | 1.62 (0.85, 3.09) | 0.929 |

| Married | Reference | Reference | Reference | --- |

| Education | ||||

| College or more | Reference | Reference | Reference | --- |

| High school/GED | 2.26 (1.45, 3.53) | 0.97 (0.53, 1.77) | 2.14 (0.97, 4.75) | 0.059 |

| Less than high school | 4.04 (2.55, 6.41) | 1.12 (0.60, 2.09) | 2.54 (1.14, 5.68) | 0.003 |

| Annual personal income | ||||

| <$6450 | Reference | Reference | Reference | --- |

| $6450-11,700 | 1.03 (0.71, 1.51) | 1.21 (0.65, 2.24) | 1.95 (0.98, 3.88) | 0.233 |

| >$11,700 | 0.96 (0.68, 1.36) | 1.63 (0.93, 2.86) | 2.57 (1.35, 4.89) | 0.023 |

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) | ||||

| None | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| One | 1.37 (0.93, 2.01) | 1.32 (0.67, 2.64) | 1.88 (0.85, 4.14) | 0.702 |

| Two | 1.77 (1.18, 2.65) | 2.55 (1.31, 4.97) | 3.57 (1.67, 7.65) | 0.208 |

| Three or More | 2.60 (1.77, 3.83) | 3.67 (1.95, 6.91) | 6.08 (2.95, 12.53) | 0.088 |

CI, confidence interval.

Significant results are shown in bold font.

All variables included in the models are shown above.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between childhood experiences and subsequent risky health behaviors among low-income, urban, mothers-to-be. Individual and total ACEs were associated with smoking, alcohol use, and any illicit drug use during pregnancy.

In this sample of urban, low-income women, the prevalence of ACEs was high. Reports of physical abuse (52%) were high, despite a strict definition that excluded spanking. This rate is higher than previous estimates of physical abuse.37, 38 The prevalence of child sexual abuse was lower than in the ACE Study (13% vs. 24%)37 and lower than previous estimates of 20% to 40%.39 The prevalence of domestic violence was nearly identical to that found in the ACE Study, 13% vs. 13.9%.37 The majority (71%) had at least one ACE and one in five (21%) reported major childhood adversity, with 3 or more ACEs.

The findings that individual and total ACEs, in a dose-response manner, were associated with the risky health behaviors are consistent with previous literature showing an association between childhood adversity and risky health behaviors in adulthood. Prior studies have shown a significant relationship between childhood adversity and an increased risk for low self-esteem, behavior problems and depression,40, 41 outcomes that are associated with substance use. Affected individuals may partake in high-risk behaviors as a means of coping with or self-regulating stress, low self-esteem and pain. In addition, evidence suggests that childhood trauma and stress are associated with neurodevelopmental deficits, such as inhibition of neurogenesis and lower volumes of certain regions of the brain, and alterations of biological stress systems, which may play a role in subsequent health behaviors.42, 43

Furthermore, the intergenerational impact of risky health behaviors is highlighted by the finding that children with parents/guardians with a history of substance use were more likely to use substances, a finding supported by previous research on alcohol and drug use.41, 44 This intergenerational transmission is thought to be related to many causes, including genetic and environmental factors.

This study has a number of limitations. Not all mothers completing the prenatal survey completed the postpartum surveys. The fact that these mothers had lower annual personal incomes suggests that they may have had more financial hardship. It is possible that they had more childhood adversity; therefore, our results may underestimate some exposures and outcomes. Reports of childhood experiences were retrospective, with women being asked to report childhood experiences before age 16 when they were on average 24. Reports are subject to recall bias, although evidence suggests that this bias has been overestimated.45 Our study, building on the ACE Study, may be subject to less recall bias since our sample is younger (average age of 24 vs. 56).31 Survey questions may not capture the complexity and diversity of childhood experiences. For instance, this study did not measure the severity or frequency of experiences. Our assessment of sexual abuse used the term “sexual abuse,” which may have underestimated exposure. A recent study showed that use of the word “abuse” in questions, when compared to questions describing abusive experiences, resulted in lower reported abuse in community samples.46 In addition, patient reports have been shown to underestimate actual substance use; therefore, we may have underestimated the prevalence of risky health behaviors. Alcohol use during pregnancy may have been overestimated in that we assessed any alcohol use, which could have included occasional “social” drinks. This study also did not quantitatively assess cigarette, alcohol, or illicit drug.

This study adds to the growing literature on adverse childhood experiences and their association with adverse health conditions and risky health behaviors among affected individuals, including mothers in the perinatal period.9, 30, 35, 41 Health professionals should use the perinatal period as a “window of opportunity” to discuss parental experiences and attitudes and to educate parents about the harmful effects of physical and sexual abuse, and verbal hostility. Medical histories should include questions that elicit information about domestic violence, exposure to gun violence, and household substance use. Health care professionals should partner with local community organizations to provide available resources to families and to improve social and health policies in an effort to reduce childhood adversity.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, #TS-286-14/14 (Co-PI: Dr. Jennifer Culhane), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, #1-RO1-HD36462-01A1 (Co-PIs: Drs. Jennifer Culhane and Irma Elo). We would especially like to thank all of the women who participated in this study, and all of the interviewers who collected the data.

This research was presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting in Toronto, Canada, May 8, 2007, and funded in part by grants from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, #TS-286-14/14 (Co-PI: Dr. Jennifer Culhane), and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, #1-RO1-HD36462-01A1 (Co-PIs: Drs. Jennifer Culhane and Irma Elo).

Footnotes

There are no potential conflicts of interests or corporate sponsorships.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Esther K. Chung, Department of Pediatrics, Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, DE, Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Laila Nurmohamed, Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, PA.

Mr. Leny Mathew, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Irma T. Elo, Department of Sociology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. James C. Coyne, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (Coyne).

Dr. Jennifer F. Culhane, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

References

- 1.Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Health Risk Behaviors and Mental Health Problems as Mediators of the Relationship between Childhood Abuse and Adult Health. Am J Public Health. 2008 Aug 13; doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Mamun A, Alati R, O'Callaghan M, et al. Does childhood sexual abuse have an effect on young adults' nicotine disorder (dependence or withdrawal)? Evidence from a birth cohort study. Addiction. 2007 Apr;102(4):647–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelson EC, Heath AC, Lynskey MT, et al. Childhood sexual abuse and risks for licit and illicit drug-related outcomes: a twin study. Psychol Med. 2006 Oct;36(10):1473–1483. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kellogg ND, Hoffman TJ, Taylor ER. Early sexual experiences among pregnant and parenting adolescents. Adolescence. 1999 Summer;34(134):293–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohannessian CM, Hesselbrock VM. Paternal alcoholism and youth substance abuse: the indirect effects of negative affect, conduct problems, and risk taking. J Adolesc Health. 2008 Feb;42(2):198–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coker AL, Richter DL, Valois RF, McKeown RE, Garrison CZ, Vincent ML. Correlates and consequences of early initiation of sexual intercourse. J Sch Health. 1994 Nov;64(9):372–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santelli JS, Kaiser J, Hirsch L, Radosh A, Simkin L, Middlestadt S. Initiation of sexual intercourse among middle school adolescents: the influence of psychosocial factors. J Adolesc Health. 2004 Mar;34(3):200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonell C, Allen E, Strange V, et al. Influence of family type and parenting behaviours on teenage sexual behaviour and conceptions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006 Jun;60(6):502–506. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.042838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA. 1999 Nov 3;282(17):1652–1658. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.17.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman ND, Leitzmann MF, Hollenbeck AR, Schatzkin A, Abnet CC. Cigarette smoking and subsequent risk of lung cancer in men and women: analysis of a prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008 Jul;9(7):649–656. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis RM, Novotny TE. The epidemiology of cigarette smoking and its impact on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989 Sep;140(3 Pt 2):S82–84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.3_Pt_2.S82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhat VM, Cole JW, Sorkin JD, et al. Dose-response relationship between cigarette smoking and risk of ischemic stroke in young women. Stroke. 2008 Sep;39(9):2439–2443. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alcohol-related traffic fatalities involving children--United States, 1985-1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997 Dec 5;46(48):1130–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maggs JL, Patrick ME, Feinstein L. Childhood and adolescent predictors of alcohol use and problems in adolescence and adulthood in the National Child Development Study. Addiction. 2008 May;103 1:7–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace JM., Jr The social ecology of addiction: race, risk, and resilience. Pediatrics. 1999 May;103(5 Pt 2):1122–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Maternal smoking before and after pregnancy: effects on behavioral outcomes in middle childhood. Pediatrics. 1993 Dec;92(6):815–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernstein IM, Plociennik K, Stahle S, Badger GJ, Secker-Walker R. Impact of maternal cigarette smoking on fetal growth and body composition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Oct;183(4):883–886. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.109103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollack H, Lantz PM, Frohna JG. Maternal smoking and adverse birth outcomes among singletons and twins. Am J Public Health. 2000 Mar;90(3):395–400. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salihu HM, Wilson RE. Epidemiology of prenatal smoking and perinatal outcomes. Early Hum Dev. 2007 Nov;83(11):713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Church MW, Crossland WJ, Holmes PA, Overbeck GW, Tilak JP. Effects of prenatal cocaine on hearing, vision, growth, and behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998 Jun 21;846:12–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abel EL. Prenatal effects of alcohol. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1984 Sep;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(84)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 6th. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson K, Posner SF, Biermann J, et al. Recommendations to improve preconception health and health care--United States. A report of the CDC/ATSDR Preconception Care Work Group and the Select Panel on Preconception Care. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006 Apr 21;55(RR-6):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alcohol use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age - United States, 1991-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 May 22;58(19):529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.ACOG Committee Opinion number 313, September 2005. The importance of preconception care in the continuum of women's health care. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Sep;106(3):665–666. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200509000-00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atrash H, Jack BW, Johnson K. Preconception care: a 2008 update. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Dec;20(6):581–589. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328317a27c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.D'Angelo D, Williams L, Morrow B, et al. Preconception and interconception health status of women who recently gave birth to a live-born infant--Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 26 reporting areas, 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007 Dec 14;56(10):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forrest JD. Epidemiology of unintended pregnancy and contraceptive use. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994 May;170(5 Pt 2):1485–1489. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)05008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Floyd RL, Decoufle P, Hungerford DW. Alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition. Am J Prev Med. 1999 Aug;17(2):101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dube SR, Miller JW, Brown DW, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the association with ever using alcohol and initiating alcohol use during adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2006 Apr;38(4):444 e441–410. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felitti VJ. Adverse childhood experiences and adult health. Acad Pediatr. 2009 May-Jun;9(3):131–132. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schilling EA, Aseltine RH, Jr, Gore S. Adverse childhood experiences and mental health in young adults: a longitudinal survey. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott KM, Von Korff M, Alonso J, et al. Childhood adversity, early-onset depressive/anxiety disorders, and adult-onset asthma. Psychosom Med. 2008 Nov;70(9):1035–1043. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318187a2fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chung EK, Mathew L, Elo IT, Coyne JC, Culhane JF. Depressive symptoms in disadvantaged women receiving prenatal care: the influence of adverse and positive childhood experiences. Ambul Pediatr. 2008 Mar-Apr;8(2):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW., Jr A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 Jan;115(1):92–106. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. Jama. 2001 Dec 26;286(24):3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briere J, Elliott DM. Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl. 2003 Oct;27(10):1205–1222. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roosa MW, Reinholtz C, Angelini PJ. The relation of child sexual abuse and depression in young women: comparisons across four ethnic groups. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1999 Feb;27(1):65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fleming J, Mullen PE, Sibthorpe B, Bammer G. The long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse in Australian women. Child Abuse Negl. 1999 Feb;23(2):145–159. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anda RF, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatr Serv. 2002 Aug;53(8):1001–1009. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.8.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Teicher MH, Andersen SL, Polcari A, Anderson CM, Navalta CP. Developmental neurobiology of childhood stress and trauma. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002 Jun;25(2):397–426. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(01)00003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bremner JD. The relationship between cognitive and brain changes in posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006 Jul;1071:80–86. doi: 10.1196/annals.1364.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson JL, Leff M. Children of substance abusers: overview of research findings. Pediatrics. 1999 May;103(5 Pt 2):1085–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Surtees PG, Wainwright NW. The shackles of misfortune: social adversity assessment and representation in a chronic-disease epidemiological setting. Soc Sci Med. 2007 Jan;64(1):95–111. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thombs BD, Bernstein DP, Ziegelstein RC, et al. An evaluation of screening questions for childhood abuse in 2 community samples: implications for clinical practice. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 9;166(18):2020–2026. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.18.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]