Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationships between the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and underlying structural factors of poverty and wealth in several African countries.

Methods

A retrospective ecological comparison and trend analysis was conducted by reviewing data from demographic and health surveys, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) indicator surveys and national sero-behavioural surveys in 12 sub-Saharan African countries with different estimated national incomes. Published survey reports were included in the analysis if they contained HIV testing data and wealth quintile rankings. Trends in the relation between gender-specific HIV prevalence and household wealth quintile were determined with the χ2 test and compared across the 12 countries, and also within one country (the United Republic of Tanzania) at two points in time.

Findings

The relationship between the prevalence of HIV infection and household wealth quintile did not show consistent trends in all countries. In particular, rates of HIV infection in higher-income countries did not increase with wealth. Tanzanian data further illustrate that the relationship between wealth and HIV infection can change over time in a given setting, with declining prevalence in wealthy groups occurring simultaneously with increasing prevalence in poorer women.

Conclusion

Both wealth and poverty can lead to potentially risky or protective behaviours. To develop better-targeted HIV prevention interventions, the HIV community must recognize the multiple ways in which underlying structural factors can manifest themselves as risk in different settings and at different times. Context-specific risks should be the targets of HIV prevention initiatives tailored to local factors.

ملخص

الغرض

تقصي العلاقة بين انتشار العدوى بفيروس العوز المناعي البشري والعوامل الهيكلية الأساسية للفقر والثروة في عدد من البلدان الأفريقية.

الطريقة

أجريت مقارنة بيئية استعادية وتحليل للاتجاهات من خلال مراجعة المعطيات المستقاة من المسوحات الديموغرافية والصحية، ومسوحات مؤشر متلازمة العوز المناعي المكتسب (الإيدز)، والمسوحات الوطنية المصلية والسلوكية في 12 بلداً في جنوب الصحراء الأفريقية تتفاوت فيما بينها في تقديرات دخلها الوطني. وأُدرِجت التقارير المنشورة للمسوحات في التحليل كلما وجد فيها معطيات عن اختبار فيروس العوز المناعي البشري وترتيب الثروة حسب الشرائح الخمسية. وقيست اتجاهات العلاقة بين الانتشار النوعي لفيروس العوز المناعي البشري حسب الجنس والشريحة الخمسية لثروة المنزل باستخدام اختبار خي مربعχ2، وأجريت المقارنات بين الـ 12 بلداً، كما أجريت مقارنة داخل بلد واحد (وهو جمهورية تنزانيا الاتحادية) في نقطتين زمنيتين.

الموجودات

لم تُظهِر العلاقة بين انتشار العدوى بالفيروس والشريحة الخمسية لثروة السكان اتجاهات ثابتة في جميع البلدان. وبخاصة لم تزد معدلات العدوى بالفيروس في البلدان ذات الدخل المرتفع مع زيادة الثروة. إضافة إلى ذلك، أظهرت المعطيات في تنزانيا أن العلاقة بين الثروة والعدوى بفيروس العوز المناعي البشري يمكن أن تتغير مع مرور الوقت في موقع محدد، حيث تراجع انتشار العدوى في المجموعات الغنية في نفس وقت زيادة انتشار العدوى بين النساء الفقيرات.

الاستنتاج

يمكن أن يؤدي كل من الثروة والفقر إلى احتمال القيام بسلوكيات خطرة أو سلوكيات وقائية. ولإعداد التدخلات الوقائية من فيروس العوز المناعي البشري الأدق هدفاً، على المجتمع الذي يتعاطى مع الفيروس أن يدرك الطرق المتعددة التي يمكن للعوامل الهيكلية الرئيسية أن تظهر فيها كعوامل خطورة في مواقع وأزمنة مختلفة. ويجب أن تكون المخاطر الخاصة بكل سياق محلي على حده هي الهدف الذي تستهدفه المبادرات الوقائية من فيروس العوز المناعي البشري المعدّلة وفقاً للعوامل المحلية.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier la relation entre la prévalence de l'infection par le virus de l'immunodéficience humaine (VIH) et les facteurs structuraux sous-jacents de la pauvreté et de la richesse dans plusieurs pays africains.

Méthodes

Une comparaison écologique rétrospective et une analyse des tendances ont été réalisées à partir de l'examen des données d'enquêtes démographiques et sanitaires, d'enquêtes sur les indicateurs du syndrome d'immunodéficience acquise (sida) et d'enquêtes séro-comportementales nationales, menées dans 12 pays d'Afrique sub-saharienne ayant un revenu national estimé variable. Les rapports d'enquêtes publiés étaient pris en compte dans l'analyse s'ils contenaient des données de dépistage du VIH et un classement par quintiles de richesse. Les tendances de la relation entre la prévalence par sex du VIH et le quintile de richesse des ménages ont été déterminées par le test du χ² et comparées entre les 12 pays et au sein d'un même pays (la République Unie de Tanzanie), à deux moments différents.

Résultats

La relation entre la prévalence de l'infection à VIH et le quintile de richesse des ménages ne suivait une tendance similaire dans tous les pays. En particulier, les taux d'infection par le VIH dans les pays à haut revenu n'augmentaient pas avec le niveau de richesse. Les données tanzaniennes montraient en outre que cette relation entre richesse et infection par le VIH pouvait évoluer au cours du temps dans un contexte donné, avec une baisse de la prévalence dans les groupes les plus aisés se produisant en même temps que l'augmentation de cette prévalence parmi les femmes pauvres.

Conclusion

La richesse, comme la pauvreté, peuvent conduire à des comportements potentiellement dangereux ou protecteurs. Pour mettre au point des interventions mieux ciblées contre le VIH, la communauté concernée par le VIH/sida doit reconnaître les multiples façons dont les facteurs structuraux sous-jacents peuvent se manifester en tant que risques dans divers contextes et à différents moments. Les risques spécifiques au contexte doivent être visés par des interventions de prévention du VIH adaptées aux facteurs locaux.

Resumen

Objetivo

Investigar la relación entre la prevalencia del virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) y la pobreza y la riqueza como factores estructurales en varios países africanos.

Métodos

Se llevó a cabo una comparación ecológica y un análisis de tendencias retrospectivos a partir de datos de encuestas de demografía y salud, encuestas de indicadores del síndrome de inmunodeficiencia adquirida (sida) y encuestas nacionales de serología y comportamiento en 12 países del África subsahariana con diferentes ingresos nacionales estimados. Se incluyeron en el análisis los trabajos sobre encuestas que contenían datos sobre las pruebas del VIH y sobre los quintiles de riqueza. Las tendencias de la relación entre la prevalencia del VIH por sexo y el quintil de riqueza doméstica se determinaron mediante la prueba de ji cuadrado (χ2), haciéndose una comparación entre los 12 países, así como en un mismo país (República Unida de Tanzanía) en dos puntos en el tiempo.

Resultados

La relación entre la prevalencia de la infección por VIH y el quintil de riqueza doméstica no reveló tendencias coherentes en todos los países. En particular, las tasas de infección por VIH en los países de mayores ingresos no aumentaban con la riqueza. Los datos de Tanzanía muestran además que la relación entre riqueza e infección por VIH puede variar con el tiempo en un determinado entorno, con una disminución de la prevalencia en los grupos ricos y, simultáneamente, un aumento de la misma entre las mujeres más pobres.

Conclusión

Tanto la riqueza como la pobreza pueden propiciar comportamientos de riesgo o de protección. Para diseñar intervenciones de prevención de la infección por VIH más focalizadas, la comunidad interesada debe ser consciente de las múltiples maneras en que los factores estructurales pueden manifestarse en forma de riesgo en los diferentes entornos y en diferentes instantes. Como parte de su adaptación a los factores locales, las iniciativas de prevención de la infección por VIH deben centrarse en los riesgos específicos de cada contexto.

Introduction

A long-held belief in the field of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection prevention is that poverty drives HIV epidemics. The World Bank’s 1997 report Confronting AIDS explained that “widespread poverty and unequal distribution of income that typify underdevelopment appear to stimulate the spread of HIV”.1 Similarly, the United Nations Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) stated in 2001 that “[p]overty, underdevelopment, the lack of choices and the inability to determine one’s own destiny fuel the [HIV] epidemic”.2 As recently as 2004, in the Lancet, Fenton reviewed evidence on how poverty leads people to high-risk behaviours and concluded that reducing poverty may be the only viable long-term response to the epidemic.3

However, the argument that poverty “fuels” the spread of HIV has been challenged by recent studies based on statistical correlations of epidemiological and socioeconomic data. These studies show that in many African countries, the prevalence of HIV infection correlates directly with wealth. For example, Shelton et al. illustrated a strong positive relationship between household wealth and HIV infection prevalence in the United Republic of Tanzania.4 Chin, who analysed data from Kenya, also showed that national HIV prevalence rates appeared to correlate directly with national income across sub-Saharan Africa5 – a trend noticed as early as 2000.6 More recently, Mishra et al. analysed HIV infection prevalence by wealth group with national survey data for eight African countries (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, the United Republic of Tanzania and Uganda) and concluded that there was a positive association between household economic status and prevalence.7 However, they did not look at how trends differed according to national income or changed with time.

This has left many wondering whether it is poverty or wealth that correlates with HIV infection prevalence. Peter Piot (former executive director of UNAIDS) et al. attempted to answer this question by showing that in African countries HIV infection rates correlate not only with wealth, but also with income inequality.8 Arguments about this issue, however, often suffer from a key conceptual weakness that may hinder progress in the prevention of HIV infection: the assumption that prevalence correlates with wealth (or relative wealth) in only one way. But attempts to correlate relative wealth directly with prevalence do not accurately reflect the dynamics that characterize the way in which underlying social drivers and structural factors manifest themselves as risk of HIV infection, or how these factors change with time. The relationship between wealth and HIV infection is not direct, nor does it always act in the same direction in every setting. Instead, the ways structural factors lead to situations of risk or non-risk in a given setting must be conceptualized through a more nuanced approach that does not assume that either wealth or poverty leads to risky behaviours. A better approach is one that understands that both wealth and poverty may have associated risks and protective effects in different contexts.

No previous analyses have compared the association between trends in HIV infection and wealth within countries according to national income levels or longitudinal factors. Since publication of the study by Mishra et al., several additional country surveys have been conducted with relevant data. I used this expanded set of surveys to investigate the relationships between HIV infection prevalence and underlying structural factors of poverty and wealth in several African countries.

Methods

I conducted an ecological comparison and trend analysis with data from nationally representative HIV sero-surveys that related prevalence with linked indicators of socioeconomic status in sub-Saharan African countries. In addition, I performed a longitudinal study with data from two surveys done at different times in one of the countries.

Most estimates of the prevalence of HIV infection, such as those provided in the biannual UNAIDS Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic,9 are based on anonymous testing of pregnant women at antenatal surveillance sites. However, these surveillance methods do not routinely collect data on socioeconomic status. To investigate the correlations between indicators of poverty and wealth and HIV infection I used data that related infection status to a measure of relative poverty or wealth, and that could therefore be compared across countries. However, poverty or wealth are often subjective concepts, and The World Bank has explained that poverty tends to be linked to income and consumption levels.10 Absolute income for individuals is hard to measure in low-income countries because much work is not wage-paying, annual accounting is rare and employment and production of consumption goods are often home-based. These factors make valuation difficult.11 Most health surveys do not ask about individual income levels, or do so in non-standardized ways that make cross-country comparisons difficult.

The most standardized approach to assess relative wealth across populations is found in Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), AIDS Indicator Surveys (AIS) and Sero-Behavioural Surveys (SBS) (available at: http://www.measuredhs.com). These surveys use a wealth index based on household ownership of different items correlated with economic status in each country, and respondents are accordingly classified into wealth quintiles, from the poorest 20% to the wealthiest 20%. This wealth scoring system was specifically designed to provide a measure of socioeconomic status that can be related to health data, and to overcome problems with direct measurement of income.11

The Measure DHS web site12 was consulted to obtain all currently available surveys for sub-Saharan African countries that included both HIV testing data and wealth quintile rankings. I identified 19 surveys that matched these criteria, including two surveys from the United Republic of Tanzania. I also searched other web sites to locate alternative national surveys conducted with similar methods to assess relative wealth. Additional web and literature searches were combined with checks of the HIV Surveillance Database of the United States Agency for International Development13 and the HIV InSight database of the University of California at San Francisco.14 This identified six additional household HIV surveys published since 2001 from sub-Saharan African countries. However, these surveys were excluded because they either provided no measure of income or used non-standardized measures of income that made comparison across countries problematic.

An initial analysis included all 19 DHS, AIS, and SBS surveys from 18 countries that related HIV prevalence to a wealth asset score. Data were obtained from 16 DHSs (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Rwanda, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe),15–30 three AIS (Côte d’Ivoire, the United Republic of Tanzania 2003–04 and the United Republic of Tanzania 2007–08)31–33 and one national SBS (Uganda).34 The individual surveys along with sampling and estimation methods are explained in detail elsewhere.7,35 All DHS, AIS and SBS data used in the present study are publicly available from the Measure DHS project12 on request.

The UNAIDS programme classifies a national prevalence rate higher than 1% as a generalized epidemic.36 Of the 18 countries for which data were available, three had a national HIV infection prevalence rate lower than 1% and were excluded from further analysis. Four countries had a national prevalence rate between 1% and 2%. Because I compared prevalence between population subgroups by wealth quintile, I wished to ensure that no subgroup had a prevalence rate below 1%. Subgroup analysis also meant lower sample sizes and hence larger confidence intervals (CIs). This would have made analysis of trends in countries with a low prevalence of HIV infection particularly difficult. To draw more robust conclusions, I included in the final sample only countries with a national prevalence of HIV infection of 2% or higher, namely Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Rwanda, Swaziland, the United Republic of Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This criterion ensured prevalence rates above 1% for all wealth quintile subgroups and was also consistent with the definition of a generalized epidemic.

I compared the trends in gender-specific rates of HIV infection prevalence by wealth quintile in all 12 countries. For each gender-specific subgroup prevalence, 95% CIs were calculated and χ2 tests were done to determine trends. Longitudinal trends were determined in the United Republic of Tanzania, where two surveys had been completed at different times.

Results

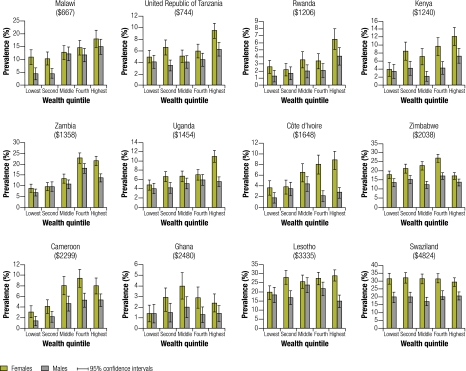

The prevalence of HIV infection among adults (age 15–49 years) in the 12 countries analysed ranged from 2.2% in Ghana to 25.9% in Swaziland. Table 1 summarizes the data for each country, including national prevalence estimates and national income measured as per capita gross domestic product (GDP) adjusted for purchasing power parity, based on the United Nations Development Programme estimates for 2005.37 Table 2 presents the numerical data for HIV infection prevalence in each country by sex and wealth quintile, along with 95% CIs for each measurement and results of χ2 tests for trends and the resulting P-values. Trends by country stratified by sex are presented graphically in Fig. 1.

Table 1. Income, prevalence of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in adults aged 15–49 years and survey coverage information for 12 sub-Saharan African countries, 2003–08.

| Country, survey year and survey type | Per capita GDP (PPP in US$)36 | National HIV prevalence (%) | No. tested |

Overall HIV response rate (%)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |||||

| Malawi, 2005, DHS25 | 667 | 11.8 | 2 864 | 2404 | 70 | 63 | ||

| United Republic of Tanzania, 2007–08, AIS33 | 744 | 5.7 | 8 713 | 6332 | 90 | 80 | ||

| Rwanda, 2005, DHS28 | 1206 | 3.0 | 5 679 | 4741 | 97 | 96 | ||

| Kenya, 2003, DHS22 | 1240 | 6.7 | 3 285 | 2941 | 76 | 70 | ||

| Zambia, 2008, DHS15 | 1358 | 14.3 | 5 711 | 5159 | 77 | 72 | ||

| Uganda, 2004–05, SBS34 | 1454 | 6.4 | 10 227 | 8298 | 89 | 84 | ||

| Côte d’Ivoire, 2005, AIS31 | 1648 | 4.7 | 4 566 | 3928 | 79 | 76 | ||

| Zimbabwe, 2005–06, DHS30 | 2038 | 18.1 | 7 491 | 5554 | 76 | 63 | ||

| Cameroon, 2004, DHS18 | 2299 | 5.5 | 5 287 | 5098 | 92 | 90 | ||

| Ghana, 2003, DHS20 | 2408 | 2.2 | 5 311 | 4274 | 89 | 80 | ||

| Lesotho, 2004, DHS23 | 3335 | 23.5 | 3 032 | 2246 | 81 | 68 | ||

| Swaziland, 2006–07, DHS29 | 4824 | 25.9 | 7 061 | 5782 | 88 | 81 | ||

AIS, AIDS indicator survey; DHS, demographic and health survey; GDP, gross domestic product; PPP, purchasing power parity; SBS, sero-behavioural survey; US$, United States dollars.

a Overall response rate is the number of people tested divided by the number of surveyed individuals eligible for testing.

Table 2. Trend for the association between prevalence of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and wealth quintile in men and women in 12 sub-Saharan African countries, 2003–08.

| Country and year of survey | Wealth quintile | Women |

Men |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | χ2 test for trend | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | χ2 test for trend | |||

| Malawi, 200525 | Lowest | 10.9 | 8.0–13.8 | 14.80 (P < 0.001) | 4.4 | 2.1–6.7 | 37.85 (P < 0.001) | |

| Second | 10.3 | 7.8–12.8 | 4.6 | 2.7–6.5 | ||||

| Third | 12.7 | 10.0–15.4 | 12.1 | 9.4–14.8 | ||||

| Fourth | 14.6 | 11.8–17.4 | 11.7 | 9.0–14.4 | ||||

| Fifth | 18.0 | 14.7–21.3 | 14.9 | 11.9–17.9 | ||||

| United Republic of Tanzania, 2003–0432 | Lowest | 2.8 | 1.8–3.8 | 90.81 (P < 0.001) | 4.1 | 2.7–5.5 | 37.11 (P < 0.001) | |

| Second | 4.6 | 3.3–5.9 | 4.3 | 3.0–5.6 | ||||

| Third | 6.8 | 5.3–8.3 | 4.3 | 3.0–5.6 | ||||

| Fourth | 10.9 | 9.1–12.7 | 7.7 | 6.1–9.3 | ||||

| Fifth | 11.4 | 9.8–13.0 | 9.4 | 7.8–11.0 | ||||

| United Republic of Tanzania, 2007–0833 | Lowest | 5.0 | 3.9–6.1 | 22.67 (P < 0.001) | 4.1 | 3.0–5.2 | 10.86 (P = 0.001) | |

| Second | 6.6 | 5.3–7.9 | 3.5 | 2.5–4.5 | ||||

| Third | 5.1 | 4.0–6.2 | 4.1 | 3.0–5.2 | ||||

| Fourth | 6.0 | 4.9–7.1 | 4.5 | 3.4–5.6 | ||||

| Fifth | 9.5 | 8.2–10.8 | 6.3 | 5.1–7.5 | ||||

| Rwanda, 200528 | Lowest | 2.6 | 1.7–3.5 | 26.82 (P < 0.001) | 1.3 | 0.5–2.1 | 15.42 (P < 0.001) | |

| Second | 2.2 | 1.4–3.0 | 1.7 | 0.8–2.6 | ||||

| Third | 3.6 | 2.5–4.7 | 2.0 | 1.1–2.9 | ||||

| Fourth | 3.4 | 2.3–4.5 | 2.1 | 1.2–3.0 | ||||

| Fifth | 6.5 | 5.0–8.0 | 4.1 | 2.9–5.3 | ||||

| Kenya, 200322 | Lowest | 3.9 | 2.2–5.6 | 42.86 (P < 0.001) | 3.4 | 1.7–5.1 | 10.68 (P = 0.001) | |

| Second | 8.5 | 6.2–10.8 | 4.2 | 2.4–6.0 | ||||

| Third | 7.1 | 5.0–9.2 | 2.2 | 0.9–3.5 | ||||

| Fourth | 9.7 | 7.4–12.0 | 4.3 | 2.7–5.9 | ||||

| Fifth | 12.2 | 9.9–14.5 | 7.3 | 5.5–9.1 | ||||

| Zambia, 200815 | Lowest | 8.8 | 7.0–10.6 | 126.51 (P < 0.001) | 6.8 | 5.2–8.4 | 42.68 (P < 0.001) | |

| Second | 9.6 | 7.8–11.4 | 9.6 | 7.4–11.8 | ||||

| Third | 13.3 | 11.2–15.4 | 10.7 | 8.7–12.7 | ||||

| Fourth | 22.9 | 20.5–25.3 | 18.1 | 15.9–20.3 | ||||

| Fifth | 21.6 | 19.5–23.7 | 13.6 | 11.7–15.5 | ||||

| Uganda, 2004–0534 | Lowest | 4.8 | 3.7–5.9 | 47.88 (P < 0.001) | 4.0 | 2.9–5.1 | 6.39 (P = 0.012) | |

| Second | 6.6 | 5.5–7.7 | 4.2 | 3.2–5.2 | ||||

| Third | 6.7 | 5.5–7.9 | 5.1 | 4.0–6.2 | ||||

| Fourth | 7.0 | 5.9–8.1 | 5.9 | 4.7–7.1 | ||||

| Fifth | 11.0 | 9.7–12.3 | 5.5 | 4.5–6.5 | ||||

| Côte d’Ivoire, 200531 | Lowest | 3.6 | 2.3–4.9 | 32.06 (P < 0.001) | 1.7 | 0.7–2.7 | 0.07 (P = 0.798) | |

| Second | 3.8 | 2.5–5.1 | 3.4 | 2.1–4.7 | ||||

| Third | 6.5 | 4.8–8.2 | 4.3 | 2.9–5.7 | ||||

| Fourth | 8.0 | 6.2–9.8 | 2.1 | 1.1–3.1 | ||||

| Fifth | 8.8 | 7.1–10.5 | 2.7 | 1.7–3.7 | ||||

| Zimbabwe, 2005–0630 | Lowest | 17.7 | 15.6–19.8 | 0.52 (P = 0.470) | 13.4 | 11.2–15.6 | 0.66 (P = 0.416) | |

| Second | 21.1 | 18.8–23.4 | 15.1 | 12.9–17.3 | ||||

| Third | 22.7 | 20.4–25.0 | 12.2 | 10.2–14.2 | ||||

| Fourth | 26.8 | 24.6–29.0 | 17.1 | 15.3–18.9 | ||||

| Fifth | 17.1 | 15.3–18.9 | 13.5 | 11.6–15.4 | ||||

| Cameroon, 200418 | Lowest | 3.1 | 2.0–4.2 | 35.79 (P < 0.001) | 1.4 | 0.5–2.3 | 24.14 (P < 0.001) | |

| Second | 4.1 | 2.8–5.4 | 2.2 | 1.2–3.2 | ||||

| Third | 8.1 | 6.4–9.8 | 4.7 | 3.3–6.1 | ||||

| Fourth | 9.4 | 7.7–11.1 | 5.3 | 4.0–6.6 | ||||

| Fifth | 8.0 | 6.5–9.5 | 5.3 | 4.1–6.5 | ||||

| Ghana, 200320 | Lowest | 1.4 | 0.6–2.2 | 1.12 (P = 0.286) | 1.4 | 0.5–2.3 | 0.12 (P = 0.730) | |

| Second | 2.7 | 1.6–3.8 | 1.5 | 0.6–2.4 | ||||

| Third | 4.0 | 2.8–5.2 | 2.0 | 1.0–3.0 | ||||

| Fourth | 2.9 | 1.9–3.9 | 1.3 | 0.6–2.0 | ||||

| Fifth | 2.4 | 1.6–3.2 | 1.4 | 0.7–2.1 | ||||

| Lesotho, 200423 | Lowest | 19.6 | 15.8–23.4 | 8.03 (P = 0.005) | 18.3 | 14.2–22.4 | 0.19 (P = 0.665) | |

| Second | 27.9 | 24.2–31.6 | 16.8 | 13.0–20.6 | ||||

| Third | 25.5 | 21.8–29.2 | 23.7 | 19.7–27.7 | ||||

| Fourth | 27.3 | 23.9–30.7 | 21.6 | 17.8–25.4 | ||||

| Fifth | 28.9 | 25.8–32.0 | 14.8 | 11.4–18.2 | ||||

| Swaziland, 2006–0729 | Lowest | 31.6 | 28.2–35.0 | 1.15 (P = 0.283) | 19.8 | 16.5–23.1 | 0.56 (P = 0.455) | |

| Second | 32.1 | 28.8–35.4 | 19.8 | 16.6–23.0 | ||||

| Third | 31.5 | 28.4–34.6 | 17.0 | 14.4–19.6 | ||||

| Fourth | 31.8 | 28.9–34.7 | 21.1 | 18.4–23.8 | ||||

| Fifth | 29.4 | 26.7–32.1 | 20.4 | 17.8–23.0 | ||||

CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 1.

Prevalencea of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by wealth quintile in 12 sub-Saharan African countries presented in order of increasing national incomeb

GDP, gross domestic product; PPP, purchasing power parity; US$, United States dollars.

a Please note that the y-axis scale is not uniform between graphs.

b Figures in parentheses are national GDP per capita (US$, PPP adjusted).

A consistent increase in prevalence by wealth quintile was seen in women in Côte d’Ivoire and Uganda, and in men in Rwanda. Among women in Côte d’Ivoire, for instance, the highest prevalence was seen in the fourth and fifth quintiles, whereas among men prevalence peaked in the second and third quintiles. In Lesotho the highest prevalence among women was in the second and fifth wealth quintiles, whereas among men prevalence was highest in the third and fourth quintiles.

Comparisons of country data showed that the trend for prevalence to increase together with wealth was more pronounced in lower-income countries. For almost all countries with a per capita GDP lower than 2000 United States dollars (US$), tests for linear trend in the relationship between gender-specific prevalence and wealth quintile showed significance: χ2 test P-values were lower than 0.05 (and most were lower than 0.01) in all cases except for men in Côte d’Ivoire. For countries with a per capita GDP higher than US$ 2000, a significant linear trend (P ≤ 0.05) was seen only for men and women in Cameroon and for women in Lesotho.

In countries with a per capita GDP higher than US$ 2000 there was no consistent increase in prevalence with wealth quintile. Men in Cameroon came the closest to reflecting this increase, with an equal prevalence in the two wealthiest groups. In Zimbabwe and Swaziland, prevalence was in fact lowest in the highest wealth quintile for women. This contrasted with the findings for lower-income countries. In most countries with a per capita GDP lower than US$ 2000, the prevalence in women was highest in the highest wealth quintile. The exception to this trend was Zambia, where prevalence was highest in the fourth quintile and second highest for the wealthiest subgroup. Among countries with a per capita GDP higher than US$ 2000, only Lesotho had a prevalence among men that was lowest in the highest wealth quintile. The only countries in which the highest prevalence among men was in the highest wealth quintile were the four lowest-income countries: Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda and the United Republic of Tanzania.

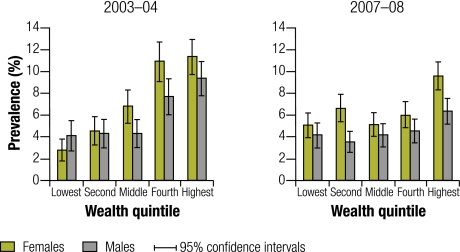

In the United Republic of Tanzania two AISs have been carried out, one in 2003–04 and another in 2007–08. Between the two surveys the national HIV prevalence in adults decreased from 7.0% to 5.4%. Table 2 shows, however, that this decrease was not evenly distributed across wealth quintiles. Among women the prevalence of HIV infection decreased in the highest three wealth quintiles between 2003–04 and 2007–08 but increased in the two poorest wealth groups. Among men the prevalence remained the same in the poorest subgroup but decreased for all other wealth quintiles, with the largest decreases in the highest-income subgroups. Trends in the prevalence across time, stratified by sex, are presented graphically in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Change between 2003–04 and 2007–08 in prevalence of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) by wealth quintile the United Republic of Tanzania

Discussion

Increases in the prevalence of HIV infection by wealth quintile as identified in Kenya by Chin5 and in the United Republic of Tanzania by Shelton et al.4 are common, but not universal. An analysis of data from the 2003–04 United Republic of Tanzania AIS32 showed a consistent increase in prevalence by wealth quintile in women, although in the more recent 2007–08 AIS this association was not seen. I found that among women the prevalence of HIV infection was higher and more strongly associated with wealth quintile than among men. Women are biologically more susceptible to HIV infection,38 which would explain higher overall prevalences among women, although it would not explain why trends for men and women sometimes differed within individual countries. As per capita GDP increased, the trend for the prevalence of HIV infection to follow wealth quintile became less clear. Moreover, data from the United Republic of Tanzania showed that the relationship between relative wealth and disease prevalence can change with time. Because HIV infection can lead to a loss of household income or assets, some HIV-positive individuals may have moved into lower wealth groups, but evidence for this is lacking in the data for men. Variability between genders within countries underlines the importance of recognizing that different lifestyles with different associated risk behaviours can arise from combinations of underlying factors, which can include gender as well as wealth.

The findings of my analysis illustrate the need to reexamine the assumption that, “wealth/poverty is correlated with HIV prevalence”. Underlying structural factors can affect HIV risk in several ways in different contexts. It is also important to recognize possible ecological fallacies in assuming that the correlation with wealth must appear within countries simply because it may be seen across them. Although it has been observed that national HIV prevalence appears to increase with national income in Africa,5 the association between household wealth and individual prevalence appeared weakest in the higher-income, higher-prevalence countries, with Swaziland providing the best example of this.

Poor people in some settings undertake particular risky practices – e.g. earlier sexual debut39,40 or reliance on transactional sex3 – whereas wealthy individuals may engage in other risky practices, such as participation in broader social and sexual networks or sex with higher numbers of (voluntary) regular partners.4 The risks associated with any of these patterns of behaviour is highly context-specific and the patterns themselves are likely to change. The Tanzanian data indicate that relative wealth may be associated with higher risk initially but may become a protective factor as the epidemic matures, a possibility highlighted in two previous literature reviews on wealth and socioeconomic status and HIV.41,42 Changes in trends have similarly been identified previously in connection with educational level (which is highly correlated with wealth). In one systematic review, the correlation between HIV infection prevalence and educational level reversed as the HIV epidemic matured, and education became more protective with time.43 The current United Nations mantra, “know your epidemic”,36 implies that effective prevention of HIV infection requires meaningful action that affects the drivers of infection in specific settings and groups. Effective action requires unpacking the black box of behaviour by recognizing that HIV infection in poorer groups may arise from certain lifestyles and risky behaviours related to poverty, whereas HIV infection in wealthy groups may be due to different lifestyles and risky behaviours related to their wealth. It is also important to understand that any of these lifestyle factors and behaviours can vary with time and place. This may explain the results seen in Africa, where higher national income or evolution of the epidemic over time may change the dynamics between relative household wealth and risk of HIV infection. Insights into the dynamic relationship between wealth and HIV infection can help guide prevention efforts in two ways. First, they can help us move beyond assumptions that either poverty or wealth is exclusively correlated with HIV infection, since these assumptions can lead to oversimplified and ineffective prevention strategies. Second, they provide guidance on how interventions can affect structural drivers of risk. As Gupta et al. have shown, several calls have been made to address structural factors leading to HIV infection, but the development of ideas on how to operationalize structural approaches to prevention has been limited.44 Operationalization will require moving beyond broad statements on the importance of underlying structures, including poverty or wealth, and working to document and change how they influence transmission.

To address underlying structures we need first to identify the causal mechanisms that lead specific factors to translate into the risk of HIV infection in different social contexts, and then develop interventions that target specific mechanisms. These efforts require a more “bottom-up” approach to prevention than is often seen. Many actors will not be accustomed to designing and implementing interventions in this way. However, some efforts are already using a bottom-up approach to plan interventions based on specific lifestyles and risk environments of the target community.

The Sonagachi project in Kolkata, India, is one such programme. This project has been widely praised for creating an environment that allowed sex workers to manage the underlying determinants of their own risk environment and empowered them to insist on safer sex work practices.45,46 A similar approach is being used in the Avahan project (supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation), which targets local structural determinants of HIV risk such as stigma, violence and mobility.47 Another example of the bottom-up approach is a randomized trial in Kenya48 that was designed for a context where older men often give cash to girls in sexual relationships. In this study, reducing the costs of school-related items for girls had a greater impact on teenage pregnancy and school dropout rates than either teacher training on the prevention of HIV/AIDS infection or encouraging students to discuss and debate condom use. This effect was presumably a result of reducing girls’ reliance on transactional relationships to be able to afford items required to attend school, such as uniforms.48 These examples illustrate the success of interventions designed to consider the social circumstances related to risk behaviours in given settings. They are not meant to be a list of effective or best practices, but instead provide proof of concept of alternative ways to approach structural interventions for the prevention of HIV infection.

Neither poverty nor wealth per se drives the HIV epidemic. Being poor or being wealthy may be associated with sets of behaviours that are either protective or risky for HIV infection. The data reported here from 12 sub-Saharan African countries helps illustrate the complexities and non-deterministic nature of the relationship between structural factors such as poverty or wealth and the risk of HIV infection. My analysis further shows that any trend in the association between relative wealth and risk of infection can vary among different countries and may change with time. A bottom-up focus is necessary to identify factors that drive the risk of HIV infection in both wealthy and poorer groups in a given setting. Once these factors have been identified, appropriate behavioural change interventions can be selected and implemented. Although it may sound difficult, addressing these challenging issues will be necessary to make progress in efforts to prevent HIV infection.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.The World Bank. Confronting AIDS: public priorities in a global epidemic New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. The global strategy framework on HIV/AIDS Geneva: UNAIDS; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fenton L. Preventing HIV/AIDS through poverty reduction: the only sustainable solution? Lancet. 2004;364:1186–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shelton JD, Cassell MM, Adetunji J. Is poverty or wealth at the root of HIV? Lancet. 2005;366:1057–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin J. The AIDS pandemic: the collision of epidemiology with political correctness Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halperin DT, Allen A.Is poverty the root cause of African AIDS? AIDS Anal Afr 2000111512349722 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishra V, Assche SB, Greener R, Vaessen M, Hong R, Ghys PD, et al. HIV infection does not disproportionately affect the poorer in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S17–28. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300532.51860.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piot P, Greener R, Russell S. Squaring the circle: AIDS, poverty, and human development. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Report on the global HIV/AIDS epidemic Geneva: UNAIDS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The World Bank. Overview: understanding, measuring and overcoming poverty. Washington: The World Bank Group; 2009. Available from: http://go.worldbank.org/RQBDCTUXW0 [accessed 27 October 2009].

- 11.Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index Calverton: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demographic and Health Surveys. Calverton: Measure DHS, ICF Macro; 2009. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com [accessed 26 May 2010].

- 13.HIV/AIDS Surveillance Database. Washington: United States Agency for International Development; 2009. Available from: http://hivaidssurveillancedb.org [accessed 26 May 2010].

- 14.HIV InSite. San Francisco: UCSF Center for HIV Information; 2009. Available from: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite

- 15.Zambia Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Calverton: Central Statistical Office and Macro International Inc.; 2009.

- 16.Enquête démographique et de santé du Bénin 2006 [In French]. Calverton: Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Économique and ORC Macro; 2007. French.

- 17.Enquête démographique et de santé du Burkina Faso 2003 [In French]. Calverton: Institut National de la Statistique et de la Démographie and ORC Macro; 2004.

- 18.Enquête démographique et de santé du Cameroun 2004 [In French]. Calverton: Institut National de la Statistique and ORC Macro; 2004.

- 19.Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa and Calverton: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro; 2006.

- 20.Ghana Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton: Ghana Statistical Service, NMIMR, and ORC Macro; 2004.

- 21.Enquête démographique et de santé de Guinée 2005 [In French]. Calverton: Institut National de la Statistique and ORC Macro; 2006.

- 22.Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2003. Calverton: Central Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health and ORC Macro; 2004.

- 23.Lesotho Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Calverton: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (Lesotho), Bureau of Statistics and ORC Macro; 2005.

- 24.Liberia Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Monrovia: Liberia Institute of Statistics and Geo-Information Services and ORC Macro; 2008.

- 25.Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2004. Calverton: National Statistical Office and ORC Macro; 2005.

- 26.Enquête démographique et de santé du Mali 2006 [In French]. Calverton: Cellule de Planification et de Statistique du Ministère de la Santé and ORC Macro; 2007.

- 27.Enquête de base du programme services de base intégrés, Niger 2006 [In French]. Calverton, Maryland: Institut National de la Statistique, United Nations Children’s Fund and ORC Macro; 2007.

- 28.Rwanda Demographic and Health Survey. Calverton: Institut National de la Statistique and ORC Macro; 2006.

- 29.Swaziland Demographic and Health Survey 2006-07. Mbane: Central Statistical Office and ORC Macro; 2008.

- 30.Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2005-06. Calverton: Central Statistical Office and ORC Macro; 2007.

- 31.Enquête sur les indicateurs du sida, Côte d’Ivoire 2005 [in French]. Calverton: Institut National de la Statistique and ORC Macro; 2006.

- 32.Tanzania HIV/AIDS indicator survey 2003-04. Calverton: Tanzania Commission for AIDS, National Bureau of Statisics (Tanzania) and ORC Macro; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanzania HIV/AIDS and malaria indicator survey 2007-08. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Commission for AIDS, ZAC, National Bureau of Statistics, Office of the Chief Government Statistician and ORC Macro; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uganda HIV/AIDS sero-behavioural survey 2004-2005. Kampala and Calverton: Uganda Ministry of Health and ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Macro International, Inc. HIV prevalence estimates from the demographic and health surveys Calverton: Macro; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Practical guidelines for intensifying HIV prevention: towards universal access. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Indicators: human development report 2009 New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2009. Available from: http://hdrstats.undp.org/indicators [accessed 17 February 2010].

- 38.Quinn TC, Overbaugh J. HIV/AIDS in women: an expanding epidemic. Science. 2005;308:1582–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1112489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hargreaves JR, Morison LA, Chege J, Rutenburg N, Kahindo M, Weiss HA, et al. Socioeconomic status and risk of HIV infection in an urban population in Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7:793–802. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hallman K. Gendered socioeconomic conditions and HIV risk behaviours among young people in South Africa. AJAR. 2005;4:37–50. doi: 10.2989/16085900509490340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wojcicki JM. Socioeconomic status as a risk factor for HIV infection in women in East, Central and Southern Africa: a systematic review. J Biosoc Sci. 2005;37:1–36. doi: 10.1017/S0021932004006534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillespie S, Kadiyala S, Greener R. Is poverty or wealth driving HIV transmission? AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 7):S5–16. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000300531.74730.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hargreaves JR, Bonell CP, Boler T, Boccia D, Birdthistle I, Fletcher A, et al. Systematic review exploring time trends in the association between educational attainment and risk of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2008;22:403–14. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f2aac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372:764–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen J. HIV/AIDS in India. Sonagachi sex workers stymie HIV. Science. 2004;304:506. doi: 10.1126/science.304.5670.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cornish F, Ghosh R. The necessary contradictions of ‘community-led’ health promotion: a case study of HIV prevention in an Indian red light district. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Avahan: the India AIDS Initiative: the business of HIV prevention at scale. New Delhi: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; 2008.

- 48.Duflo E, Dupas P, Kremer M, Sinei S. Education and HIV/AIDS prevention: evidence from a randomized evaluation in Western Kenya. Cambridge: MIT Poverty Action Lab; 2006. [Google Scholar]